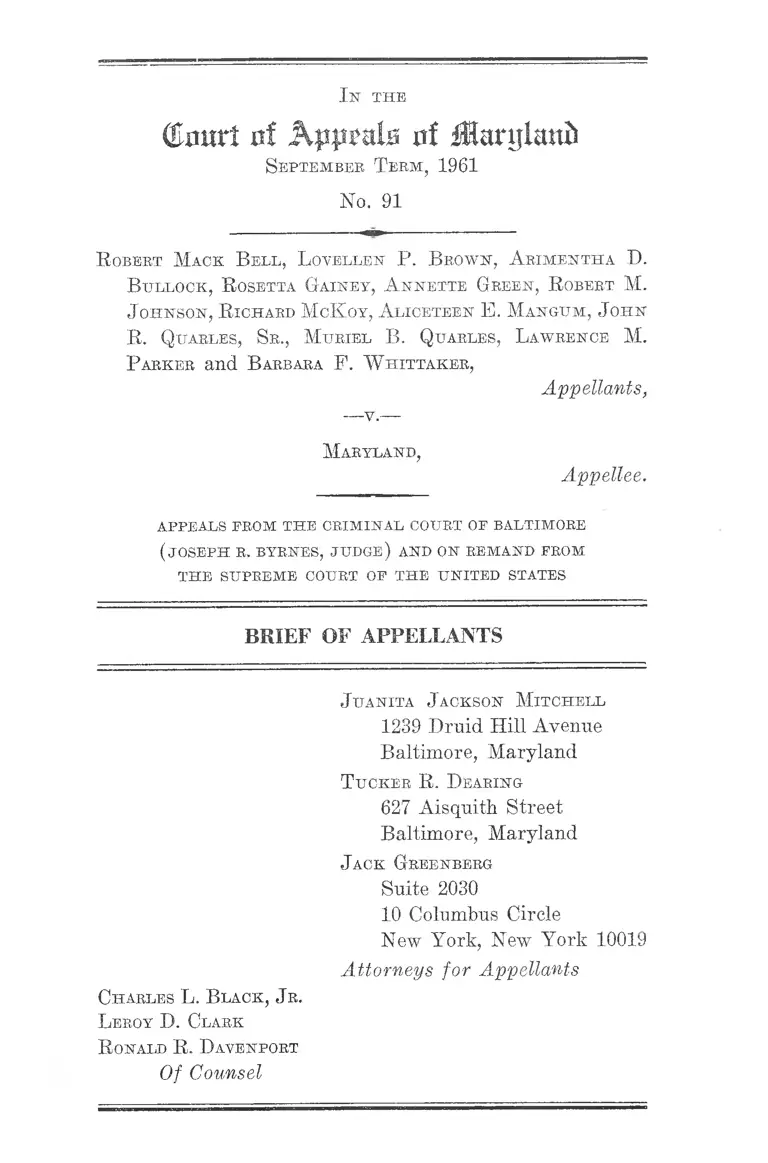

Bell v. Maryland Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bell v. Maryland Brief of Appellants, 1964. 3c517ba3-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/439ee456-782c-4a93-8cdc-c8e96e07fddf/bell-v-maryland-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

I s r t h e

( ta rt nt Apprals of ila rg lta

S e pt e m b e r T e r m , 1961

No. 91

R obert M ack B e l l , L ovellen P . B r o w n , A r im e n t h a D .

B u llo c k , R osetta G a in e y , A n n e t t e G r e e n , R obert M .

J o h n so n , R ichard M cK oy, A l ic e t e e n E. M a n g u m , J o h n

R. Q u arles , S r., M u r ie l B. Q u arles , L a w ren ce M.

P arker and B arbara F. W h it t a k e r ,

Appellants,

---- V .----

M aryland ,

Appellee.

A PPEA LS PRO M T H E C R IM IN A L CO U RT OP B A LTIM O RE

( J O S E P H R . B Y R N ES, JU D G E ) AND ON R EM A N D PRO M

T H E S U P R E M E COU RT O P T H E U N IT E D STA TES

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

J u a n ita J ackson M it c h e l l

1239 Druid Hill Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

T u c k e r R . B earing

627 Aisquith Street

Baltimore, Maryland

J ack G reenberg

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

C harles L. B la ck , Jr.

L eroy D. Clark

R onald R . D avenport

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case .............. -........... -....-....--------- 1

Questions in Controversy ....... ....—- .......... .............. — 2

Statement of F acts.............. -------- ----------------------- 3

A r g u m en t ...... — ..... ................................---------- --------------------- ^

I. The Conviction of Appellants for Trespass

Cannot Be Sustained Because Their Conduct

No Longer Constitutes a Crime Under Present

State and Local Law ................. .....—........— 4

II. By the Passage of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, Congress Has Removed the Taint of

Criminality From Petitioners’ Conduct, and

Federal Law Requires the Dismissal of 1 ur-

ther Proceedings ----------------------------------- 12

C on clu sio n ...... ........-................. -.........- ............... -......... ............. - 26

T able of C ases

Awolin v. Atlas Exchange Bank, 295 U. S. 209 ...... . 14

Beard v. State, 74 Md. 130, 24 Atl. 700 (1891) ------- 7, 8, 11

Bell v. Maryland, 378 IT. S. 226,12 L. Ed. 2d 822 ....5, 8, 9,10,

11,13,15,16, 20

Board of Comm’s v. LTnited States, 308 U. S. 343 .........- 14

Deitrick v. Greaney, 309 U. S. 190 ........ —----- ------ --- H

11

PAGE

Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64 ........ ...............- 14

Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U. S. (9 Wheaton) 1 --------- --- 13

Green v. State, 170 Md. 134, 183 Atl. 526 (1936) ___ 9

Hauenstein v. Lynham, 100 U. S. 483 ............................ 13

Keller v. State, 12 Md. 322 (1858) ...........................-6,7,8

Louisville & Nashville R.R. v. Mottley, 211 U. S. 149 ....18,19

Maryland v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co., 44 U. S. (3 How.)

534 ....... .............................. .........-................... .......... 15

Massey v. United States, 291 U. S. 608 ......................— 16

NLRB v. Carlisle Lumber, 94 F. 2d 138 (9th Cir. 1937),

cert. den. 304 U. S. 575 (1938), cert. den. 306 U. S.

646 (1939) ......................... ........................ -.............. 19

O’Brien v. Western Union Telegraph Co., 113 F. 2d

539 (1st Cir. 1940) ..................................................... 14

Phelps Dodge v. NLRB, 113 F. 2d 202 (2d Cir. 1940),

modified and remanded on other grounds, 313 U. S.

177 (1941) ......................... ........ ......... .......... .......... 19

Prudence Corp. v. Geist, 316 U. S. 89............................ 14

Royal Indemnity Co. v. United States, 313 U. S. 289 .... 14

Smith v. Maryland, 45 Md. 49 (1876) .... .............. ..... 8

Sola Elec. Co. v. Jefferson Elec. Co., 317 U. S. 173 ....13,14

Sperry v. Florida, 373 U. S. 379 .......... .................. ...13,14

State v. American Bonding Co., 128 Md. 268, 97 Atl.

529 (1916) 9

Ill

PAGE

State y. Clifton, 177 Md. 572, 10 A. 2d 703 (1940) ....6, 9,10

State v. Gambrill, 115 Md. 506, 81 Atl. 10 (1911) ..... 8

State v. Kennerly, 204 Md. 412,104 A. 2d 632 (1955) ....9,10

United States v. Chambers, 291II. S. 217..... 16

United States v. Reisinger, 128 U. S. 398 ................. 15

United States v. Schooner Peggy, U. S. (1 Cranch) 103 15

United States v. Tynen, 78 U. S. (11 Wall.) 8 8 .......... 15

Yeaton v. United States, 9 U. S. (5 Cranch) 281 .... 15

F ederal S tatutes

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241 .......... 12,13,14,16,

17,18,19, 20

National Labor Relations Act (Wagner-Connery Act)

§8(a) (1) and (a)(3), 49 Stat. 452 (1935), 29 U. S. C.

§158(a)(l) and (a)(3) ......... ........................ ........... 19

1 U. S. C. §109 ................................ ........... ...............16,17

S tate C o n stitu tio n a l and S tatutory P rovisions

Md. Const. Art. XVI .............. .................... ................ 5

1 Md. Code §3 (1957) ..................................................... 9,16

27 Md. Code §577 (1957) ........................... ......... ...... 4

49B Md. Code §11 (1963) ............... ......................... . 5

Baltimore City Code, No. 1249, Article 14A, §10A

(1950) .................. ......................- ........... ......... .....- 5

IV

PAGE

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Baltimore Sun, May 31, 1964, p. 22, col. 1 ..................... 5

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. 2464 (1870) ....... ...... 17

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 3rd Sess. 775 (1871) ------- 17

110 Cong. Bee. 9162-3 (daily ed. May 1, 1964) ............. 13

110 Cong. Bee. 12999 (daily ed. June 11, 1964) .......... 17

House Judiciary Committee Beport on the Civil Bights

Act, H. B. Beport No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1963) ............... ......... .............................. ................. 17

Million, Expiration or Bepeal of a Federal or Oregon

Statute as a Bar to Prosecution for Violations There

under, 24 Ore. L. Bev. 25 (1944) ............................ 17

I n t h e

(Emtrt of Appeals of Maryland

S e pt e m b e r T e r m , 1961

No. 91

R obert M ack B e l l , L ovellen P. B r o w n , A r im e n t h a D.

B u llo c k , R osetta Ga in e y , A n n e t t e G r e e n , R obert M.

J o h n so n , R ichard M cK oy, A l ic e t e e n E . M a n g u m , J o h n

R . Q u arles , S r., M u r ie l B . Q u arles , L a w ren ce M .

P arker a n d B arbara P . W h it t a k e r ,

Appellants,

— v.—

M aryland ,

Appellee.

A PPEA LS PR O M T H E C R IM IN A L COURT OP BA LTIM O RE

( J O S E P H R. B Y R N E S, JU D G E ) AND ON R EM A N D PRO M

T PIE S U P R E M E COURT O F T H E U N IT E D STATES

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

On July 12, 1960, appellants, students attending local

schools were indicted by the Baltimore City Grand Jury

for trespassing on the premises of Hooper’s Restaurant at

the southwest corner of Payette and Charles Streets in

Baltimore City. They were tried before Judge Byrnes on

November 10, 1960, and on March 24, 1961, were found

guilty of violating Article 27, section 577 of the Maryland

Code, 1957 Edition. Each appellant was given a suspended

fine of $10.00 and order to pay costs of Court. On appeal,

2

this Court affirmed those judgments. On writ of certiorari

the Supreme Court of the United States vacated the judg

ments and remanded the cases for consideration by this

Court.

Questions in Controversy

1. Whether the passage of public accommodations laws

by the City of Baltimore and the State of Maryland, while

the case at bar was on appeal, requires the reversal of

appellants’ convictions.

2. Whether the passage of the Federal Civil Rights

Act of 1964 prior to the final termination of the proceed

ings of the instant case requires the reversal of appellants’

convictions.

Statement o f Facts

Hooper’s Restaurant is a privately-owned conventional

restaurant located at the southwest corner of Fayette and

Charles Streets in the City of Baltimore. It is one of sev

eral restaurants owned and operated by Gr. Carroll Hooper.

It, along with the other restaurants operated by Mr.

Hooper, holds itself open to the public. It is not a private

club and there are no signs restricting patronage to mem

bers of any particular group or class. Each appellant is a

member of the Negro race and a student in Baltimore

schools.

On or about June 17, 1960, appellants entered the res

taurant while it was open for business and, in the customary

fashion of white persons, requested the hostess, Ella Mae

Dunlap, to assign them seats at tables for the purpose of

being served. Miss Dunlap informed appellants that it was

not the policy of the restaurant to serve Negroes, that she

could not seat or serve any of the appellants, and asked

3

appellants to leave. She explained to them that she was

following instructions of the owner. Appellants, despite the

refusal to serve, persisted in their demands. They moved

past Miss Dunlap and took seats at various tables on the

main floor and in the basement. Appellants were not served

and continued to sit at the tables.

The manager, Albert R. Warfel, and the owner, G. Carrol

Hooper, were both called to the scene. They declared that

the policy of the restaurant was not to serve any Negroes

and requested that appellants leave. Appellants again

refused to leave, protesting the discrimination policy of the

restaurant, and persisted in their demand for food service.

Police officers were called and appeared on the scene. The

trespass statute, Article 27, Section 577, of the Maryland

Code (1957 Edition) was read to appellants. They were

told that they were trespassers, and were asked to leave.

Appellants again refused to leave. Mr. Warfel was advised

by the police that in order to have appellants ejected by the

Baltimore City Police Department it would be necessary for

him to obtain warrants for their arrest for trespassing.

The police thereupon secured the appellants’ names and

addresses. Warrants for their arrests were obtained by

Mr. Hooper.

The Magistrate at the Central Police Station issued war

rants for their arrest and called Robert B. Watts, attorney

for appellants in the court below, and advised him that

warrants had been issued for their arrest. An agreement

was made to produce the appellants in Court several days

later. Appellants appeared in Magistrate’s Court at the

appointed time. Preliminary hearings were waived. Ap

pellants in due course were indicted by the Grand Jury of

Baltimore City. Each appellant posted bail bond of $100.00

and by the customary and regular procedure each appel

lant was brought to trial before Judge Byrnes in the Crim

inal Court of Baltimore.

4

Appellants, by Motions for a Directed Verdict, oral

arguments and written briefs, raised defenses under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The motions were overruled. All defenses were denied.

Judge Byrnes found that the defendants were “not law

breaking people and their action was one of principle rather

than any intentional attempt to violate the law.” Never

theless, he found each of the appellants guilty of violating

Section 577 of Article 27 of the Maryland Code (1957 Edi

tion).

Appellants’ convictions were affirmed by this Court. On

June 8, 1962, a petition for writ of certiorari was filed with

the Supreme Court of the United States. Also on June 8,

1962, the City of Baltimore enacted Ordinance No. 1249,

adding §10 A to Art. 14A of the Baltimore City Code (1950

Ed.). On March 29, 1963 the state adopted 49B Md. Code

§11 (1963 Supp.), which went into effect on June 1, 1963.

Each of the Statutes prohibits a restaurateur from denying

service because of race. The Supreme Court granted cer

tiorari and the case was argued. On June 22, 1964, the

Supreme Court reversed and remanded the case to this

Court. On July 2, 1964, the President signed the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, which similarly prohibits the type of

discrimination practiced in these cases.

I.

The Conviction of the Appellants for Trespass Cannot

Be Sustained Because Their Conduct No Longer Consti

tutes a Crime Under Present State and Local Law.

Appellants were arrested and convicted of violating

Maryland’s criminal trespass law, §577 of Article 27 of the

Maryland Code, 1957 Edition, which makes it a misde

meanor to “enter upon or cross over the land, premises or

private property of any person or persons in this State

after having been duly notified by the owner or his agent

5

not to do so.” Although this statute remains in effect in

Maryland, it is no longer applicable to the conduct for

which the appellants were convicted. Therefore in keeping

with previous decisions of this Court the convictions of

appellants must he reversed.

It is undisputed the the sole reason for the arrest of the

appellants is that they were Negroes attempting to eat at

a “white” restaurant. The hostess at Hooper’s, Edna Mae

Dunlap, admitted that appellants were properly dressed,

that they wmre not disorderly, and that had they been white

she would have allowed them to enter. Albert R. Warfel,

the manager of Hooper’s stated that they were refused

service solely on the basis of their color. G. Carroll Hooper

the president of Hooper Food, Inc., stated that it was the

preference of his customers that determined his policy not

to serve Negroes. He admitted that appellants were peace

ful and that they had a right to peaceful protest.

Since the arrest of the appellants the City of Baltimore

has enacted ordinance No. 1249, adding section 10A to

Article 14A of the Baltimore City Code (1950 edition).

This ordinance prohibits owners and operators of Balti

more places of public accommodation, including restau

rants, from denying their service or facilities to any per

son because of race. A similar public accommodations law

was enacted by the State on March 29, 1963.1 The State

law, although not applicable to all counties, is applicable

1 “Another public accommodations law was enacted by the Mary

land Legislature on March 14, 1964, and signed by the Governor

on April 7, 1964. This statute re-enacts the quoted provision from

the 1963 enactment and gives it statewide application, eliminating

the county exclusions. The new statute was scheduled to go into

effect on June 1, 1964, but its operation has apparently been sus

pended by the filing of petitions seeking a referendum. See Md.

Const., Art. X V I; Baltimore Sun, May 31, 1964, p. 22, col. 1. How

ever, the Baltimore City ordinance and the 1963 state law, both of

which are applicable to Baltimore City, where Hooper’s restaurant

is located, remain in effect.” Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226,----- ,

12 L. Ed. 822, 825, n. 1.

6

to Baltimore City and Baltimore County. This statute pro

vides :

It is unlawful for an owner or operator of a place of

public accommodation or agent or employee of said

owner or operator because of the race, creed, color, or

national origin of any person, to refuse, withhold from,

or deny to such person any of the accommodations,

advantages, facilities and privileges of such place of

public accommodations. For the purpose of this sub

title, a place of public accommodation means any hotel,

restaurant, inn, motel, or an establishment commonly

known or recognized as regularly engaged in the busi

ness of providing sleeping accommodations, or serving

food, or both, for a consideration and which is open to

the general public . . . ” (49B Md. Code Sec. 11 (1963

Suppl.)).2

It is clear that the above ordinance and statute remove

the criminal taint from appellants’ activities. Thus if the

appellants were now to go to Hooper’s and were to be de

nied service solely on the basis of race, not only wmuld they

not be subject to criminal sanctions, but the restaurant

itself would be in clear violation of both local and State

law. Therefore, the question is whether appellants’ con

victions may stand when, during the process of appeal, the

conduct previously labeled criminal is unequivocally made

lawful.

The decisions of this Court have historically followed the

common law rule “that after a statute creating a crime has

been repealed, no punishment can be imposed for any vio

lation of it committed while it was in force.” State v. Clif

ton, 177 Md. 572, 574, 10 A. 2d 703, 704 (1940). In Keller v.

2 This statute went into effect on June 1, 1963, as provided by

Sec. 4 of the Act, Acts 1963 c. 227.

7

State, 12 Md. 322 (1858) the defendant was indicted and

convicted and tiled an appeal. After the case was argued

before the Court of Appeals the legislature passed an act

repealing the act under which the indictment was framed.

Although, the former law was not brought to notice of the

court until after the defendant’s conviction was affirmed,

this Court held:

It is well settled, that a party can not be convicted,

after the law under which he may be prosecuted has

been repealed, although the offence may have been

committed before the repeal. The same principle ap

plies where the law is repealed, or expires pending an

appeal on a writ of error from the judgment of an

inferior court.

In Beard v. State, 74 Md. 130, 24 Atl. 700 (1891), the

defendant was convicted of keeping a disorderly house. The

defendant filed an appeal and the conviction was affirmed.

He fled to avoid sentencing. During the period between his

fleeing and his capture the legislature passed an act in

creasing the common lawT penalty for keeping a disorderly

house. Defendant argued that this amendment of the act

created a “new” crime thereby barring continuance of his

conviction had under the Act prior to this revision. The

court rejected the contention holding:

It will be observed that the act of 1890 does not create,

define, enlarge, or diminish, or in any way alter or

change, the common law offense. It leaves the offense

precisely as it found it and deals only with the punish

ment, it is confined exclusively to the future, and ex

pressly declared that any person who shall keep—that

is to say, who shall after the passage of that act keep—

a disorderly house shall be liable to the penalties pro-

8

vided by the act. The obvious intention of the legisla

ture in passing it was not to interfere with past of

fenses, but merely to fix a penalty for future ones.

The language employed plainly indicates that the gen

eral assembly had references to prospective, and not to

consummated offenses ; and it is not to be assumed that

the legislature purposely enacted the law with a view

to release from all punishment a convicted offender,

who was at that very time a fugitive from justice. (Id.

at 133, 701.)

If merely, the penalty had been altered (or increased) as in

Beard, appellants might have been deprived of a claim that

the “crime” no longer existed, but here the substantive

crime has been abolished. Thus, the common law rule fol

lows that “the judgment will be reversed, because the deci

sion must be in accordance with the law at the time of final

judgment.” Keller v. State, 12 Md. 322, 326, Smith v. Mary

land, 45 Md. 49 (1876).

Maryland has a savings clause “which in certain circum

stances ‘saves’ state convictions from the common law effect

of supervening enactments.” Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S.

226, 12 L. ed. 2d 822, 827. This statute provides:

The repeal, or the repeal and re-enactment, or the

revision, amendment or consolidation of any statute,

or of any section or part of a section of any statute,

civil or criminal, shall not have the effect to release,

extinguish, alter, modify or change, in whole or in part,

any penalty, forfeiture or liability, either civil or crim

inal, which shall have been incurred under such stat-

9

ute, section or part thereof, unless the repealing,

repealing and re-enacting, revising, amending or con

solidating act shall expressly so provide; and such

statute, section or part thereof, so repealed, repealed

and re-enacted, revised, amended or consolidated, shall

be treated and held as still remaining in force for the

purpose of sustaining any and all proper actions, suits,

proceedings or prosecutions, civil or criminal, for the

enforcement of such penalty, forfeiture or liability, as

well as for the purpose of sustaining any judgment,

decree or order which can or may be rendered, entered

or made in such actions, suits, proceedings, or prosecu

tions imposing, inflicting or declaring such penalty,

forfeiture or liability (1 Md. Code Sec. 3 (1957)).

The Supreme Court of the United States, in remanding to

this Court stated that the above statute is not necessarily

applicable to appellants’ convictions:

The Maryland case law under the saving clause is

meager and sheds little if any light on the present ques

tion. The clause has been construed only twice since

its enactment in 1912, and neither case seems directly

relevant here. State v. Clifton, 177 Md. 572, 10 A. 2d

703 (1940); State v. Kennedy, 204 Md. 412, 104 A. 2d

632 (1955). In two other cases, the clause was ignored.

State v. American Bonding Co., 128 Md. 268, 97 A. 529

(1916); Green v. State, 170 Md. 134, 183 A. 526 (1936).

The failure to apply the clause in these cases was ex

plained by the Court of Appeals in the Clifton case,

■supra, 177 Md., at 576-577, 10 A. 2d at 705, on the basis

that “in neither of those proceedings did it appear that

any penalty, forfeiting or liability had actually been in

curred.” This may indicate a narrow construction of

10

the clause, since the language of the clause would seem

to have applied to both cases. Also indicative of a

narrow construction is the statement of the Court of

Appeals in the Kennerly case, supra, that the saving-

clause is “merely an aid to interpretation, stating the

general rule against repeals by implication in more

specific form.” 204 Md., at 417,104 A. 2d, at 634. Thus,

if the case law has any pertinence, it supports a narrow

construction of the saving clause and hence a conclusion

that the clause is inapplicable here. Bell v. Maryland,

supra, 378 U. S. 226, 12 L. ed. 822, 828.

The savings clause does not apply to appellants’ convic

tions because it is concerned with “the repeal, or the repeal

and re-enactment, or the revision, amendment or consolida

tion of any statute or any section or part of a section of any

statute.” This language does not cover the case at bar for

the following reasons. First, in remanding, Justice Brennan

noted that as the enactment of the statute was a “unique

phenomenon” in legislation, “it would consequently seem

unlikely that the legislature intended the saving clause to

apply in this situation, where the results of its application

would be the conviction and punishment of persons -whose

‘crime’ has been not only erased from the statute books but

officially vindicated by the new enactments.” Bell v. Mary

land, supra, 12 L. ed. at 829.

Secondly, barring the owner of a place of public accom

modation from discriminating racially obviously does not

constitute a “repeal” of the trespass statute, nor does it

constitute an amendment, as that term is normally used.

The acts in no way refer to the trespass statute “as is char

acteristically done when a prior statute is being repealed or

11

amended.” Bell v. Maryland, supra, 12 L. ed. 827, 828. The

trespass statute is still in effect, although it cannot be ap

plied to enforce racial discrimination in places of public

accommodation. In any event, the terms of the statute never

required racial segregation, and therefore the public ac

commodations law does not “repeal” or “amend” those

terms.

Even assuming the applicability of the saving statute,

that statute makes it possible for a legislature to “provide”

that pending prosecution shall be voided. Justice Brennan

noted that the wording of the Maryland public accommo

dations law was in the present tense (as opposed to most

criminal statutes which use the future tense). In light of

Maryland law, this indicates an intent to have the statute

apply to present as well as future conduct. Bell v. Mary

land, supra, Beard v. State, 74 Md. 130, 21 A. 700.

Further evidence that the public accommodations laws

were intended to apply to past as well as future conduct is

the social context in which these laws were enacted. The

legislatures were attempting to deal justiciably with wide

spread protest in many Negro communities in the state.

Moreover appellants’ conduct was not made non-criminal

because of a judgment that it could not or should not be

controlled by criminal sanctions (e . g removing criminal

penalties from a failure to pay debt), rather, the legisla

tures were attempting to correct a social evil and bring back

harmony in race relations. Surely the healing of racial con

flict would best be served by a negation of all prior con

victions.

For the many reasons above, the Maryland common law

rule of abatement voids these convictions, and the “savings

clause” is inapplicable in this case.

12

II

By the Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Con

gress Has Removed the Taint of Criminality from Peti

tioners’ Conduct, and Federal Law Now Requires the

Abatement of These Prosecutions.

Oil July 2, 1964, subsequent to petitioners’ convictions

and to the remand by the United States Supreme Court of

these convictions to this Court, the President signed the

Civil Rights Act of 1964. That Act, paramount in authority,

has removed the taint of criminality from actions formerly

offenses. Title II of the Civil Rights Act provides:

Sec. 201. (a) All persons shall be entitled to the full

and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities,

privileges, advantages, and accommodations of any

place of public accommodation, as defined in this sec

tion, without discrimination or segregation on the

ground of race, color, religion, or national origin.

(b) Each of the following establishments which

serves the public is a place of public accommodation

within the meaning of this title if its operations affect

commerce, or if discrimination or segregation by it is

supported by State action: . . .

# * # # *

(2) any restaurant . . .

# # * # #

(c) The operations of an establishment affect com

merce within the meaning of this title if . . . (2) in the

case of an establishment described in paragraph (2) of

subsection (b), it serves or offers to serve interstate

travelers or a substantial portion of the food which it

serves, or gasoline or other products which it sells, has

moved in commerce; . . .

13

(d) Discrimination or segregation by an establish

ment is supported by State action within the meaning

of this title if such discrimination or segregation (1) is

carried on under color of any law, statute, ordinance, or

regulation; or (2) is carried on under color of any cus

tom or usage required or enforced by officials of the

State or political subdivision thereof; or (3) is required

by action of the State or political subdivision thereof.

78 Stat. 243.

The terms of the Act and its legislative history clearly

establish that a defendant can assert the Act as a defense

in a criminal trespass action of the type herein prosecuted.

Section 203, 78 Stat. 244 specifically provides that:

No person shall . . . (c) punish or attempt to punish

any person for exercising or attempting to exercise any

right or privilege secured by section 201 or 202.

Senator Humphrey, floor manager for the Senate, read into

the record a Justice Department statement explaining

§203(e).

“This [§203(c)] plainly means that defendant in a crim

inal trespass, breach of the peace, or other similar case

can assert the rights created by 201 and 202 and that

state courts must entertain defenses grounded upon

these provisions.” Cong. Record, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

9162-3 (May 1, 1964).

Appellants submit that the Civil Rights Act of 1964, par

ticularly §203(c), as set in the tradition of federal common

law expounded in Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226, 12 L. ed.

2d 822, abates these prosecutions. The text of the Act and

all its implications are part of federal law, overriding con

tradictory state law. Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U. S. (9

Wheaton) 1; Hauenstein v. Lynham, 100 IT. S. 483; Sola

Elec. Co. v. Jefferson Elec. Co., 317 U. S. 173; Sperry v.

14

Florida, 373 U. S. 379. The encompassing nature of the

Civil Eights Act of 1964 requires that the problems of these

cases be decided under the framework of the federal com

mon-law. It would be inconsistent with the pervasive na

tional policies of this Act to allow the continuation of these

types of prosecutions depend upon differing policies of

separate states. In the Sola case, the Supreme Court said,

at p. 176:

It is familiar doctrine that the prohibition of a fed

eral statute may not be set at naught, or its benefits

denied, by state statutes or state common law rules.

In such a case our decision is not controlled by Erie

R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64. There we followed

state law because it was the law to be applied in the

federal courts. But the doctrine of that case is in

applicable to those areas of judicial decision within

which the policy of the law is so dominated by the sweep

of federal statutes that legal relations which they af

fect must be deemed governed by federal law having

its source in those statutes, rather than by local law.

Royal Indemnity Co. v. United States, 313 U. S. 289,

296; Prudence Corp. v. Geist, 316 IT. S. 89, 95 ; Board of

Comm’s v. United States, 308 U. S. 343, 349-50; cf.

O’Brien v. Western Union Telegraph Co., 113 F. 2d

539, 541. When a federal statute condemns an act as

unlawful, the extent and nature of the legal conse

quences of the condemnation, though left by the statute

to judicial determination, are nevertheless federal ques

tions, the answers to which are to be derived from the

statute and the federal policy which it has adopted.

To the federal statute and policy, conflicting state law

and policy must yield. Constitution, Art. VI, cl. 2;

Awolin v. Atlas Exchange Bank, 295 U. S. 209; Deitrick

v. Greaney, 309 U. S. 190, 200-01.

15

In Bell v. Maryland, supra, the Supreme Court stated that

the universal common-law rule is

. . . that when the legislature repeals a criminal stat

ute or otherwise removes the State’s condemnation

from conduct that was formerly deemed criminal, this

action requires the dismissal of a pending criminal

proceeding charging such conduct at 12 L. ed. 2d 826.

Justice Brennan clearly noted the consistent application of

this rule to federal enactments.

The rule has also been consistently recognized and

applied by this Court. Thus in United States v.

Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch 103, 110, 2 L. ed. 49, 51,

Chief Justice Marshall held:

“It is [in] the general true that the province of

an appellate court is only to enquire whether a judg

ment when rendered was erroneous or not. But if

subsequent to the judgment and before the decision

of the appellate court, a law intervenes and posi

tively changes the rule which governs, the law must

be obeyed, or its obligation denied. If the law be

constitutional, . . . I know of no court which can con

test its obligation. . . . In such a case the court must

decide according to existing laws, and if it be neces

sary to set aside a judgment, rightful when rendered,

but which cannot be affirmed but in violation of law,

the judgment must be set aside.”

See also Yeaton v. United Stales, 5 Cranch 281, 283,

3 L. ed. 101, 102; Maryland v. Baltimore <& 0. R. Co.,

3 How. 534, 442, 11 L. ed. 714, 722; United States v.

Tynen, 11 Wall. 88, 95, 20 L. ed. 153,155; United States

v. Reisinger, 128 U. S. 398, 401, 32 L. ed. 480, 481, 9

16

S. Ct. 99; United States v. Chambers, 291 II. S. 217,

222-223; 78 L. ed. 763, 765, 54 S. Ct. 434, 89 ALE 1510;

Massey v. United States, 291 U. S. 608, 78 L. ed. 1019,

54 S. Ct. 532. (Bell v. Maryland, supra, 12 L. ed. 2d

at 826-27, n. 2.)

A case involving the exact question of the abating effect

of a federal statute upon a state proceeding has apparently

never arisen, but since national authority is paramount,

the rule cannot be different from that in a federal prose

cution. The Civil Eights Act, specifically aimed at state

proceedings, renders lawful in the name of the national au

thority that which was at one time unlawful under the state

authority and renders unlawful the actions and claims of the

proprietors, whose interests were protected by the state’s

prosecution, cf. Bell v. Maryland, supra, at 12 L. ed. 2d at

825. The effect of the Civil Eights Act of 1964, therefore,

absent any saving clause, must be to abate these prosecu

tions.

The only relevant statutory provision is the first senence

of the Act of February 25, 1871, E. S. 13, now codified in

1 U. S. C. §109, in the following terms:

§109. Repeal of statutes as affecting existing liabilities.

The repeal of any statute shall not have the effect to

release or extinguish any penalty, forfeiture, or liability

incurred under such statute, unless the repealing Act

shall so expressly provide, and such statute shall be

treated as still remaining in force for the purpose of

sustaining any proper action or prosecution for the en

forcement of such penalty, forfeiture, or liability.

This statute is inapplicable to the present case. More nar

rowly drawn than the Maryland saving clause, it is to be

distinguished for the same reasons, see supra, pp. 10, 11;

Bell v. Maryland, supra, 12 L. ed. 2d 828-829.

17

Secondly, 1 U. S. C. §109 is inapplicable in the present

context because that enactment has never referred to the

saving of a state proceeding. The context of the 1871 en

actment was one dealing with the repeal of federal statutes

only. See Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. 2464 (1870);

id., 3rd Sess. 775 (1871); Million, Expiration Or Repeal of a

Federal or Oregon Statute as a Bar to Prosecution for

Violations Thereunder, 24 Ore. L. Rev. 25, 31, 32 (1944).

Properly construed, therefore, the word “statute” as it ap

pears in 1 U. S. C. §109 does not refer to a state enactment.

Finally, the saving clause is inapplicable because the

Civil Rights Act contains an express mandate against con

tinued prosecution §203(c), discussed supra, p. 13, pro

hibits punishing or attempting to punish any person “for

exercising or attempting to exercise any right or privilege

secured by section 201 or 202.” [Emphasis added.] The

word “secure,” in light of its ordinary dictionary meaning

and the legislative context of the Act, is an apt synonym

for “making safe that which already independently exists.”

See, House Judiciary Committee Report on the Civil

Rights Act, H. R. Report No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 18,

20 (1963) ; 110 Cong. Rec. 12999 (daily ed. June 11, 1964).

The “existence” of these rights prior to July 2, 1964, as

understood by the framers of the Act, results in the literal

applicability of §203 (c) to these prosecutions.

That §203(c) is properly construed to apply to these

cases is also shown by the constitutional underpinnings of

the Civil Rights Act. First, in §201 (a) and (b), the Act

proscribes racial discrimination directly required by ‘ state

action,” which has long been construed as prohibited by the

Fourteenth Amendment. A “right” against such state

action was clearly present before July 2, 1964. The Act does

not distinguish between this traditional concept of racially

discriminatory “state action” {e.g. segregation statute)

18

and those situations in which a private person has invoked

a state trespass law. Congress certainly did not wish to

present every court disposing of a residual prosecution

with the task of disentangling those “rights” which ante

dated the Act in some strict sense from all the rights

secured by §203(c).

Similarly, in the Civil Eights Act of 1964, Congress has

made judgments concerning “interstate commerce.” Section

201(c) (2) defines certain establishments covered by the Act

as those which “affect commerce.” The average public res

taurant which “offers to serve interstate travelers” has an

undesirable effect on commerce when refusing to serve Ne

groes. This judgment by Congress that the refusal of ser

vice to Negroes is an undesirable burden on interstate

travel must have been found to be the case before as after

the passage of the bill. These constitutional considerations

support the conclusion that Congress “secured” rights

which antedated July 2, 1964.

These tightly drawn considerations are necessary when

considering criminal liabilities. The arguments are quite

sound and their rejection would result in the affirmance of

convictions in these cases and numerous others of persons

for peacefully claiming rights which Congress has now,

overwhelmingly, in one of the great legislative enactments

of our history, declared it to be in the national interest to

“secure” against invasion.

Although the identical case in federal-state relationships,

has not been found, there are several rulings in federal

courts in analogous situations. In Louisville and Nash

ville R.R. Co. v. Mottley, 211 U. S. 149, contract rights,

perfect under state law and arising out of transactions

long antedating the federal enactment, were held not en-

19

forcible where the enforcement contravened the new fed

eral statute.

In a series of cases under the Wagner-Connery Act,

employers have been held guilty of unfair labor practices

for refusing to reinstate workers who had been discharged

prior to the effective date of the Act. Phelps Dodge v.

NLRB, 113 F. 2d 202 (2d Cir. 1940), modified and remanded

on other grounds, 313 IT. S. 177 (1941); NLRB v. Carlisle

Lumber, 94 F. 2d 138 (9th Cir. 1937), cert. den. 304 U. S.

575 (1938), cert. den. 306 U. S. 646 (1939). In effect, these

cases held that the Wagner-Connery Act required the re

sumption of the relationship terminated because of activi

ties occurring prior to the passage of the Act but favored

and fostered subsequently by the Act. The Act achieved

this result by language less decisive than that contained

in the Civil Eights Act, particularly in §203 (c). In the

Wagner Act, employers were forbidden to “interfere with,

restrain, or coerce employees in the exercise of rights guar

anteed in Section 7 . . . ” and “ . . . by discrimination in

regard to hire and tenure . . . to encourage or discourage

membership in any labor organization.” National Labor

Relations Act (Wagner-Connery Act) §8(a)(l) and (a)(3),

49 Stat. 452 (1935), 29 U. S. C. §158(a)(l) and (a)(3).

(Emphasis added.) The language of §203(c) of the Federal

Civil Eights Act makes these cases striking parallels to

the case at bar.

Finally, all state and private interests in the continued

processing of these convictions are absent. The deterrence

of petitioners, and others, from insisting on service, and

the protection of the wishes of restaurateurs to practice

racial discrimination are now illegitimate, directly con

travening law and policy at federal, state, and city levels.

On the other side of the balance, petitioners now have the

affirmative right to that conduct upon which these convic-

20

tions were grounded. In light of this unique reversal of

rights and duties, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as con

strued in the federal common law tradition, requires the

dismissal of these proceedings. See Bell v. Maryland, supra,

at 12 L. Ed. 2d 828, 829.

CONCLUSION

W h e r e fo r e , for the foregoing reasons, the appellants

pray that their convictions be reversed. With the deepest

respect, appellants also pray reconsideration of their argu

ments presented on direct appeal before this Court,

J u a n ita J ackson M it c h e l l

1239 Druid Hill Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

T u c k er R . D earing

627 Aisquith Street

Baltimore, Maryland

J ack G reenberg

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

C h a rles L. B la ck , J r.

L eroy D . Clark

R onald R . D avenport

Of Counsel

38