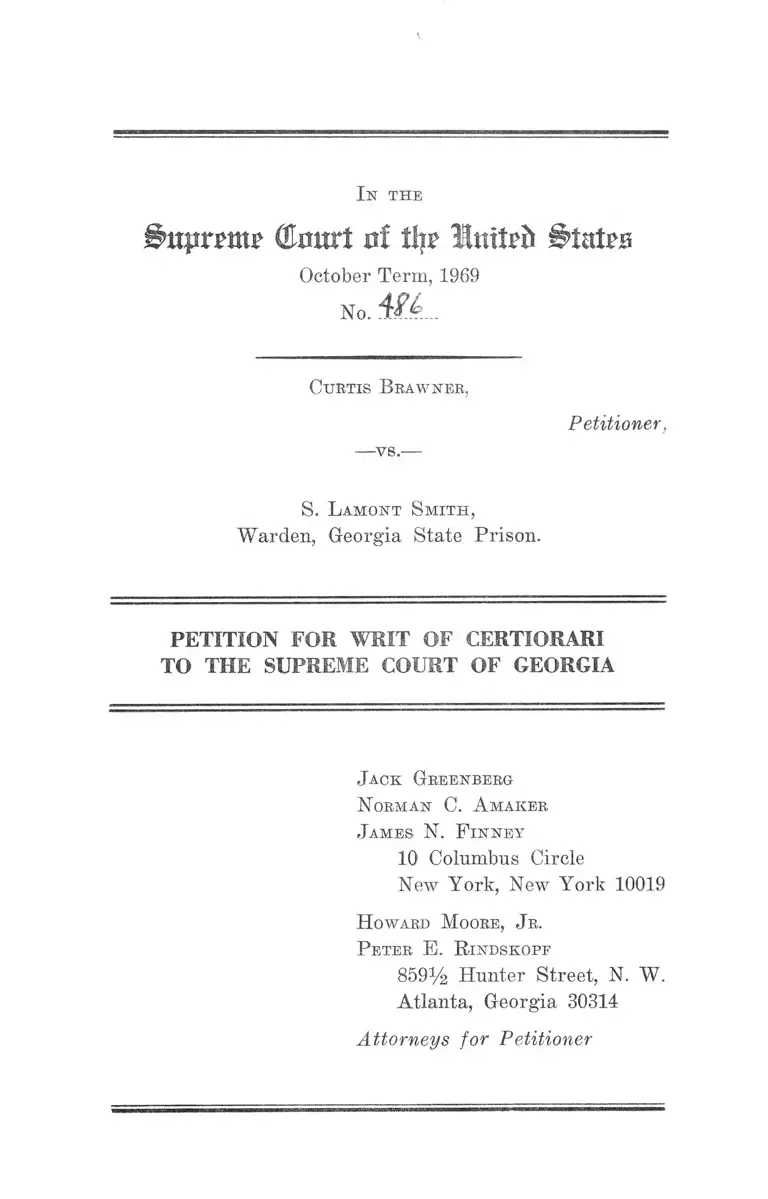

Brawner v. Smith Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brawner v. Smith Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia, 1969. d3fc1345-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/43c53487-f8f7-459b-b9ea-f73c40a081d7/brawner-v-smith-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-georgia. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

tour! ai % Imfrfc i>tatpn

October Term, 1969

No. ML.

Curtis Brawner,

—vs.—

S. Lamont Smith,

Warden, Georgia State Prison.

Petitioner,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Jack Greenberg

Norman C. A maker

James N. F inney

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H oward Moore, J r.

Peter E. R indskopf

8591/2 Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Opinion Below .................. 1

Jurisdiction ...... ................................................ -................ - 1

Questions Presented .........................-................................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 2

Statement ............................................................................. 3

The Presentation of the Federal Questions.................. 6

R easons F ob G-ranting R elief

I. Certiorari Should be Granted to Determine

Whether Petitioner Established an Unrebut-

ted Prima Facie Case of Racial Exclusion of

Negroes From Jury Service in Violation of

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment ............................................................. 7

II. There Was No Valid Waiver by Petitioner of

His Constitutional Right to Challenge the

Elbert County Prospective Juror Selection

Procedures ........................... -............... ............... 15

Conclusion ........................................... 21

A ppendix

Opinion and Judgment of the Supreme Court of

Georgia ................................... .......... -.......................... l a

Denial of Rehearing By the Supreme Court of

Georgia ................................... - .............. -....... —-........ 7a

Letter From Prof. John S. DeCani....................... 8a

PAGE

u

Table of Cases

Anderson v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 206 (1968) ...............8,13,15

Avery v. State of Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) ........... 9,10,

11,12,13

Bostick v. South Carolina, 386 U.S. 479 (1966), re

versing 247 S.C. 22, 145 S.E.2d 439 .......................... 8

Brawner v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 936 (1966) ...................... 4

Brawner v. State, 221 Ga. 680, 146 S.E.2d 737 (1965) .... 4

Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, Ala

bama, No. 908 (Oct. Term 1968) ................................... 9

Cobb v. Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95 (5th Cir., 1964) ............... 15

Cobb v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 12 (1967) .......................... 8,13,15

Doughty v. Maxwell, 376 U.S. 202 (1964) ....................... 13

Eskridge v. Washington State Prison Board, 357 U.S.

214 (1958) ......................................................................... 13

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) ..................................17,18

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) ................... 13

Green v. Myers, 401 F.2d 890 (5th Cir., 1968) ............. 16

Griffin v. People of State of Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) 13

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964) .......................... 13

Johnson v. State of New Jersey, 384 U.S. 719 (1966) ..12,13

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938) ...................... 17,18

Jones v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 24 (1967) ........................ 8,13,15

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir., 1966) ........... 20

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965) ....................... 12

PAGE

Ill

Maxwell v. Bishop, 257 F. Supp. 710 (E.D. Ark. 1966),

denial of application for certificate of probable cause

rev’d, 385 U.S. 650 (1967) .................. .......... ........... . 7

Maxwell v. Stevens, 348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965) ......... 7

McGarrah v. Dutton, 381 F.2d 161 (5th Cir., 1967) ....... 15

Mobley v. Dutton, 380 F.2d 14 (5th Cir., 1967) ............... 15

Peters v. Rutledge, 397 F.2d 731 (1968) ...................... 15,16

Pearce v. North Carolina, 372 U.S. 937 (1963) .............. 20

Pierre v. State of Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 (1939) ....... 15

Rabinowitz v. United States, 366 F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1966) 9

Rearden v. Smith, 403 F.2d 773 (5th Cir., 1968) ........... 16

Salary v. Wilson, C /A No. 25978 (5th Cir. July 31,

1969) ............................. ............................................. ..... 10

Smart v. Balkcom, 352 F.2d 502 (5th Cir., 1965) ........... 15

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ....12,14,15

Strauss v. Grimes, 223 Ga. 834 (158 S.E.2d 404) ........... 11

Sullivan v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 410 (1968) ...... ....... .....8, 13,15

Turner v. Fouche, No. 842 (Oct. Term 1968) ................... 9

United States ex rel Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71

(5th Cir. 1959), cert, denied,, 361 U.S. 838 (1959) ....19, 20

United States ex rel Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53 (5th

Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 372 U.S. 915 (1963) ...........18, 20

United States v. Atkins, 323 F.2d 733 (5th Cir., 1963) .... 9

United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353, aff’d,

380 U.S. 145 ......................................... ........................... 9

Whippier v. Balkcom, 342 F.2d 388 (5th Cir., 1965) .... 15

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir., 1964) .... .12,14,

18,19, 20

PAGE

IV

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) ...........2, 7,8,9,10,

11,12,13,14,17,18, 20

Williams v. State of Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 (1955) ....9,11,

12,13,17

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968)...................6,13

Statutes

28 U.S.C. §1257(3) ............................................................. 1

Code of Ala., Tit. 30 §21 .................................................. 9

Ark. Stat. Ann. §§3-118, 3-227, 39-208 .............................. 7

Ga. Code Ann. §92-6307 (1933) .................................. 3,4,7

Ga. Code Ann. §50-127(1) (1968 Supp.) ........................ . 16

Ga. Code Ann. §50-127(3) ................. .................... ............ 4

Ga. Code Ann. §59-106 (1965 Rev. vol.) .......................2, 8, 9

Ga. Code Ann. §59-124 ..................................................... 5

Ga. Code Ann. §92-6307 (1966 Supp.) .......................... 3

Ga. Code Ann. §50-101 (Acts 1967, p. 835) ..................... 16

Other A uthorities

Finkelstein, The Application of Statistical Decision

Theory to the Jury Discrimination Case, 80 Harv.

L.Rev. 338 (1966) .............. ....................................... . 10

PAGE

I n the

intprem? (Eitttrt of % States

October Term, 1969

No. .......

Ctjbtis Brawn EE,

-vs.

Petitioner,

S. L amont Smith,

Warden, Georgia State Prison.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia, entered

in the above-entitled cause on May 8, 1969. Motion for a

rehearing was denied on May 22, 1969.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia, set forth

in the appendix, infra, pp. la-6a, is reported at ...............

Ga............. , 167 S.E.2d 753.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia was en

tered on May 8, 1969 and motion for rehearing was denied

on May 22,1969.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. §1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and

asserting here deprivation of the rights secured by the

Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether petitioner established an unrebutted prima

facie case of racial exclusion from Elbert County, Georgia

juries in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment where

the process of jury selection was from a racially designated

source identical to that condemned in Whitus v. Georgia,

385 U.S. 545, and the resulting exclusion of Negroes was

comparable in the two cases.

2. Whether petitioner may be held to have waived his

right to challenge prospective juror selection procedures

as racially discriminatory where petitioner was not con

sulted on the decision by his white, court-appointed trial

counsel and trial counsel’s decision not to challenge racial

jury selection practices was based on fear that raising the

issue would create additional racial hostility towards peti

tioner.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the following Georgia statutes:

Ga. Code Ann. §59-106 (1965 Rev. v o l.) :

59-106. (816, 819 P. C.) Revision of jury lists. Selec

tion of grand and traverse jurors.—Biennially, or, if

the judge of the superior court shall direct, triennially

on the first Monday in August, or within 60 days there

after, the board of jury commissioners shall revise the

jury lists.

3

The jury commissioners shall select from the hooks

of the tax receiver upright and intelligent citizens to

serve as jurors, and shall write the names of the per

sons so selected on tickets. They shall select from these

a sufficient number, not exceeding two-fifths of the

whole number, of the most experienced, intelligent, and

upright citizens to serve as grand jurors, whose names

they shall write upon other tickets. The entire number

first selected, including those afterwards selected as

grand jurors, shall constitute the body of traverse

jurors for the county, to be drawn for service as pro

vided by law, except that when in drawing juries a

name which has already been drawn for the same term

as a grand juror shall be drawn as a traverse juror,

such name shall be returned to the box and another

drawn in its stead. (Acts 1878-9, pp. 27, 34; 1887, p. 21;

1892, p. 61; 1899, p. 44; 1953, Nov. Sess., pp. 284, 285;

1955, p. 247.)

Ga. Code Ann. §92-6307 (1933):

92-6307. (1086) Entry on digest of names of colored

persons.— The tax receivers shall place the names of

the colored taxpayers, in each militia district of the

county, upon the tax digest in alphabetical order.

Names of colored and white taxpayers shall be made

out separately on the tax digest. (Acts 1894, p. 31.) l

Statement

On February 6, 1965, petitioner, Curtis Brawner, a

twenty-seven year old Negro, was involved in an incident

at a coal yard in Elberton, Georgia, in which a leading

1 This section, applicable when petitioner was tried, was repealed

in 1966, Ga. Code Ann. §92-6307 (1966 Supp.).

4

white citizen was killed. Brawner was indicted, tried, and

convicted of murder and sentenced to death, at the March

1965 Term of the Elbert Superior Court. The Supreme

Court of Georgia affirmed Brawner’s conviction and death

sentence. Brawner v. State, 221 Ga. 680, 146 S.E.2d 731

(1965). This Court denied certiorari. Brawner v. Georgia,

385 U.S. 936 (1966). Petitioner then sought habeas corpus

from the City Court of Beidsville, Georgia. The petition

was denied and no appeal was taken.

Petition for writ of habeas corpus was then presented

to the United States District Court for the Southern Dis

trict of Georgia. An evidentiary hearing was held after

which the cause was transferred to the United States Dis

trict Court of the Middle District of Georgia. That Court

dismissed the federal application without prejudice, so that

appellant might first exhaust his state remedies.

Petitioner filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in

the Superior Court of Tattnall County.2 In both his federal

and state court petitions, Brawner for the first time chal

lenged the Elbert County prospective juror selection sys

tem on the grounds of racial exclusion of Negroes.

Petitioner’s evidence showed that the names of prospec

tive jurors were drawn from tax receiver’s books, and that

the names in these books were segregated by race pursuant

to state statutory law (Ga. Code Ann. §92-6307, supra).

Petitioner further presented evidence, based on United

States census data for 1960, as to the population 21 years

and older in Elbert County, Georgia : 3,474 white males,

3,843 white females, 1,272 non-white males and 1,545 non

2 Ga. Code Ann. §50-127(3) requires that a petition for writ of

habeas corpus must be filed in the Superior Court of the County

in which the petitioner is incarcerated.

5

white females (R. 723).3 In percentage terms, non-whites

constitute approximately 27% of the total population aged

21 years or older. Non-white males account for approx

imately the same percentage of the total number of males

21 years or older in the County.4 Petitioner introduced

evidence from the 1963 tax digest for Elbert County which

indicated that it contained the names of 3,416 resident

white males, 1,344 resident white females, 669 resident

Negro males, and 302 resident Negro females. Negroes

comprise approximately 16% of the total number of tax

payers contained in the 1963 tax digest, and Negro males

in the digest comprise the same percentage of the total

number of males (R. 194-195).

Petitioner further showed the Court below that of a total

of 2,047 names on grand and petit jury lists, only 26, or a

little better than .01% were Negroes (R. 180, 183, 187).

Of 48 names on the trial jury panel, two were Negro, and

these were preemptorially challenged by the State (R. 120).

The foregoing evidence was undisputed. Moreover, the

State failed to introduce any evidence to explain the

blatant disparities reflected by the statistical evidence.

Petitioner also introduced evidence by way of a deposi

tion from his white court-appointed trial counsel. Counsel

stated that he never discussed the question of challenging

the array of jurors on grounds of racial exclusion with

petitioner (R. 113, 119). He had never made such a chal

lenge himself, nor were there any white lawyers in his cir

cuit who had, and there are no Negro lawyers in the area

3 The certified record in the case consists of consecutively num

bered pages 1 through 825, arranged in five parts. “R .” refers to

the numbers stamped in blue ink at the lower left hand corner of

each page of the record, “ a” following a number refers to a page

of the Appendix, infra.

4 Women, though qualified, are not compelled to serve on juries

and may be excused upon request. 6a. Code Ann. §59-124.

6

(R. 136). Petitioner, counsel testified, was charged with

the murder of a white man who was well liked by the white

community (R. 118). Trial counsel stated that “ feeling was

pretty high in Elbert” against Brawner, and a challenge to

the array could only have led to “ increased feeling or

sentiment against the man” (R. 119).

The Superior Court denied the petition, inter alia, on

the ground that petitioner should have challenged the array

prior to his trial and his omission constituted a waiver of

his right to do so. Sua sponte, the Court found that peti

tioner’s sentence was illegal under the scrupled juror rule

of Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) and re

manded the case to the Superior Court of Elbert County

for resentencing (R. 75-76). The Court’s order and judg

ment was entered on January 21, 1969 and petitioner duly

filed an appeal of that order and judgment in the Supreme

Court of Georgia. Petitioner contended that his failure to

challenge the jury selection processes at the time of his

trial did not constitute a valid waiver of his right to do so,

and further urged that a prima facie case of racial discrim

ination in jury selection had been established below. On

May 8, 1969, the Supreme Court of Georgia entered an

order affirming the judgment and order of the Superior

Court of Tattnall County, Chief Justice Duckworth dis

senting. On May 15, 1969, petitioner filed a motion for re

hearing. The motion was denied on May 22, 1969, Chief

Justice Duckworth dissenting (7a).

The Presentation of the Federal Questions

The federal questions were raised in the petition for

writ of habeas corpus at the inception of this action and

throughout the proceedings; in the brief on appeal to the

Supreme Court of the State of Georgia, and in the petition

7

for rehearing addressed to that Court. It was alleged that

petitioner’s rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States had been violated because

the jury which tried him was the product of racially dis

criminatory selection procedures. It was further alleged

that petitioner had not constitutionally waived his right to

vindicate his federal claim. The lower state court ruled

that petitioner had waived his right to raise the federal

question (E. 72). The Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed

the lower court’s finding of waiver (5a) ; and further stated

that the rule of Whitus on which petitioner based his unre

butted prima facie claim of racial discrimination is non

retroactive (5a).

REASONS FOR GRANTING RELIEF

I.

Certiorari Should be Granted to Determine Whether

Petitioner Established an Unrebutted Prima Facie Case

of Racial Exclusion of Negroes From Jury Service in

Violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment.

Georgia Code §92-6307, effective at the time of peti

tioner Brawner’s trial6 provided that “names of colored

and white taxpayers shall be made out separately on the

tax digest.” Under local practice of Elbert County, where

6 Although the statute requiring racial designations on the tax

records has since been repealed in Georgia, the persistence of simi

lar requirements in other states makes the issue as worthy of con

sideration now as it was at the time of Whitus. See, e.g., Ark.

Stat. Ann. §§3-118, 3-227, 39-208, sustained in Maxwell v. Stevens,

348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965), and again sustained following

Whitus in Maxwell v. Bishop, 257 F.Supp. 710 (E.D. Ark. 1966),

denial of application for certificate of probable cause rev’d, 385

U.S. 650 (1967).

8

Brawner was tried and convicted, separate sections of the

tax digest were maintained for white and Negro names

(E. 185).

Georgia law requires that the jury commissioners—who

are appointed by the Superior Court—“ select from the

books of the tax receiver upright and intelligent citizens

to serve as jurors, and shall write the names of the per

sons so selected on tickets.” Ga. Code Ann. §59-106.

Petitioner Brawner’s claim of systematic racial discrim

ination in prospective grand and petit juror selection in

Elbert County, Georgia, and the factual record on which it

is based are identical to those presented to this Court in

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967).6 See also Bostick

v. South Carolina, 386 U.S. 479 (1966), reversing 247 S.C.

22, 145 S.E.2d 439; Sullivan v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 410 (1968),

reversing 223 Ga. 157, 154 S.E.2d 247; Jones v. Georgia,

389 U.S. 24 (1967), reversing 223 Ga. 157, 154 S.E.2d 228;

Cobb v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 12 (1967), reversing 222 Ga. 733,

152 S.E.2d 403; Anderson v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 206 (1968),

reversing 223 Ga. 174, 154 S.E.2d 246.

In both cases all-white jury commissioners relied upon

their personal knowledge of persons listed in the tax digest

in applying vague statutory qualifications for jury service.

At the time they select persons from the tax digest, white

jury commissioners are palpably confronted with the racial

identity of each taxpayer. This racial reminder is the more

efficacious because the provision governing jury selection,

Ga. Code Ann. §59-106, gives no specific guidance to the

6 The same statutorily required segregated tax digest was used

in that ease, and Whitus presented evidence in the lower court

that Negroes comprised 42.6% of the population 21 years or older,

27.1% of the names on the segregated tax digest, and only 8% of

the names on the grand and petit jury rolls. As was true in

Brawner’s case, no Negro served on the jury which tried Whitus.

9

commissioners in their choice of jurors. Bather, the statute

requires the commissioners to employ vague, subjective

criteria—uprightness and intelligence—which themselves

permit a broad discretion that may be exercised in a dis

criminatory manner. Cf. United States v. Louisiana, 225

F.Supp. 353, 396-97, aff’d, 380 U.S. 145; United States v.

Atkins, 323 F.2d 733 (5th Cir. 1963), and cases there cited;

Rabinowitz v. United States, 366 F.2d 34, 58 (5th Cir.

1966).7

Georgia’s statutory requirement of racial segregation of

tax records and the exclusive resort to such records in the

compilation of grand and traverse jury rolls had on at

least two occasions been condemned by this Court prior to

its holding in Whitus. See Avery v. State of Georgia, 345

U.S. 559 (1953); Williams v. State of Georgia, 349 U.S.

375 (1955). In Avery, supra, at p. 562, this Court held:

“ Even if the white and yellow tickets were drawn from

the jury box without discrimination, opportunity was

available to resort to it at other stages in the selection

process. And, in view of the case before us . . . we

think that petitioner has certainly established a prima

facie case of discrimination.”

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, concurring in Avery, pointed

out that the unconstitutionality of the procedure sprang

from “opportunities to discriminate, [which] experience

tells us there will inevitably be when such differentiating

slips are used.” Avery, swpra, at p. 564. Avery, as did

7 An appeal currently pending before the Court challenges the

juror qualifications of Ga. Code Ann. §59-106, as unconstitutionally

vague and directly contributory to the persistence of racial dis

crimination in jury selection in that state. Turner v. Touche, No.

842 (Oct. Term 1968). A similar challenge is also pending with

respect to Alabama’s statutory qualifications (Code of Ala., Tit.

30 §21). Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, Alabama,

No. 908 (Oct. Term 1968).

10

Whitus and Brawner, presented unrebutted statistical evi

dence that the opportunity to discriminate had been re

sorted to. In Avery, it was found that Negroes comprised

25% of the population of Fulton County—where the trial

had taken place—14% of the names in the racially segre

gated tax digest, and 5% of the current jury list. No

Negro was on the panel of 60 names from which Avery’s

jury was selected. In the words of Mr. Justice Frankfurter:

“ The mind of justice, not merely its eyes, would have to

be blind to attribute such an occurrence to mere fortuity.”

Avery, supra, at p. 564,

Increasingly, courts have come to recognize the validity

and usefulness of scientific method in evaluating the re;

suits of jury selection procedures. Determination of prob

abilities based on actual statistics by generally accepted

scientific methods, though consistent with intuitive judg

ment, such as is reflected in the statement of Mr. Justice

Frankfurter above, reinforces that judgment and makes

it more reliable.8 The probabilities of the selection results

found in this case have been determined:

“Assuming the combined jury list was selected at ran

dom from the 1960 population aged 21 and over,

the probability of 26 or fewer non-white names out

of a total of 2,047 names is 2.35 x 10~279, which can

8 See Whitus v. Georgia, supra, at p. 552, n. 2 citing Finkelstein,

The Application of Statistical Decision Theory to the Jury Dis

crimination Cases, 80 Harv. L. Eev. 338 (1966) :

“ While unnecessary to our disposition o f the instant case, it is

interesting to note the probability involved in the situation

before the court. . . . Assuming that 27% of the list was made

up of the names of qualified Negroes, the mathematic prob

ability of having 7 Negroes on a venire of 90 is .000006.”

And see Salary v. Wilson, C /A No. 25978 (5th Cir., Julv 31

1969), at p. 12, n. 11.

11

be written as a decimal followed by 278 zeroes and

the number 235.

“Assuming the combined jury list was selected at

random from the 1963 tax digest instead of from

the population aged 21 and over, [the] probability

of 26 or fewer non-white names out of a total of

2,047 names is 1.04 x 10-162, which can be written as

a decimal followed by 161 zeroes and the number 104.” 9

The Supreme Court of Georgia denied petitioner Brawn-

er’s claims on the ground that Whitus’ holding is nonretro

active :

“In Strauss v. Grimes, 223 Ga. 834, 835 (158 SE2d

404), this Court held: ‘We do not believe that retro

active application of the Whitus ease . . . is required

in the present case, where the grand jury indictment

was returned December 22, 1964, and no challenge was

made to the composition of the grand jury at the time

of the trial, but was first made in a post conviction

habeas corpus proceeding.’ ” (5a)

This ruling casts serious doubt and confusion on the sig

nificance of the Whitus holding and the holdings of Avery

and Williams as well because it threatens to limit the hold

ings of each case to their respective narrow factual show

ings. The struggle to vindicate Fourteenth Amendment

rights in jury selection procedures has been long and dif

ficult. The ruling of the Georgia Supreme Court, if unad

dressed by this Court, can only confuse and thus disserve

principles and rules which are settled.

9 See statement of Professor John S. deCani, infra, at 8a.

12

This Court has said that in deciding whether to limit

a rule to prospective application, the purpose of the “new

standard’ would be considered, as well as the reliance

placed upon prior decisions, and the effect of the new rule

on the administration of justice (emphasis supplied). Link-

letter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 622 (1965); Johnson v. State of

New Jersey, 384 U.S. 719 (1966). Thus, even before the

principles governing retroactivity come into play, there

must he a departure from settled doctrine. However,

Whitus announced no new or different principles; it re

stated the unconstitutionality—on equal protection grounds

—of trying a Negro defendant under a system which ex

cludes members of his race from jury service. That prin

ciple has been consistently adhered to for nearly ninety

years. See Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880).

Nor did this Court’s holding that petitioner Whitus’ evi

dence constituted a prima facie ease represent a new or

radical departure from previous constitutional interpreta

tion. Nothing said by the Court in Whitus suggests that

the evidentiary question there presented was one of first

impression or gave rise to considerations of retroactivity.

To the contrary, this Court pointed out that the circum

stances there presented were:

“ akin to those condemned in Avery v. State of Georgia,

345 U.S. 559, 73 S.Ct. 891, 97 L.Ed. 1244 (1953). There

the names of prospective Negro jurors were placed in

the jury box on yellow tickets. Here the Commissioners

used the . . . tax digest which was required by law to

be, and was maintained on a racially segregated basis.

. . . It is this old ‘system of selection’ condemned by

the Court of Appeals [Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d

496 (5th Cir,, 1964] ‘and the resulting danger of abuse

which was struck down in Avery * # Williams v.

State of Georgia, 349 U.S. 375, 382, 75 S.Ct. 814, 819,

13

99 L.Ed. 1161 (1955).” Whitus, supra, at p. 551 (em

phasis supplied).10

Moreover, this Court has relied on Whitus to reverse

judgments of the Supreme Court of Georgia in analogous

cases without inquiry into the retroactivity question. Jones

v. Georgia, supra; Cobh v. Georgia, supra; Anderson v.

Georgia, supra; Sullivan v. Georgia, supra. The ruling of

the Georgia Supreme Court ignores, and is, indeed, at war

with the impressive contrary implication of these cases.

We have urged supra that the question of retroactivity

simply does not arise where this Court applies settled doc

trine. But the Georgia Supreme Court, in refusing to fol

low the holding of Whitus, voiced the fear that the retro

active application of that case “ could bring about disastrous

results, making it possible that . . . dangerous criminals

would be turned loose upon society” (5a). Such a pos

sibility standing alone has not deterred this Court from

giving more far reaching constitutional rules retroactive

application.11 Moreover, that policy consideration is out

weighed by the fundamental principle with which it comes

in conflict. In Johnson v. New Jersey; supra, this Court

10 Even if the Court concluded that Whitus is nonretroactive,

that ruling would not— in view of Avery and Williams— be dis

positive of Brawner’s constitutional claims. Since the circum

stances in all four cases are strikingly similar and since as be

tween Brawner and Whitus they are identical, Brawner’s claims—

as were Whitus’— should have been vindicated on the basis of

Avery and Williams.

11 Eskridge v. Washington State Prison Board, 357 U.S. 214

(1958), applying the rule of Griffin v. People of State of Illinois,

351 U.S. 12, requiring the State to furnish transcripts of the trial

to indigents on appeal, to a 1935 conviction. See also Gideon v.

Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) and Doughty v. Maxwell, 376

U.S. 202 (1964) : Eight of indigent accused felon to have counsel

at the expense of the state; and see Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S.

368 (1964), whose rule concerning coerced confessions was retro

actively applied on a collateral attack; and Witherspoon v. Illi

nois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968).

14

stated that retroactive application is justified with respect

to constitutional rules which affect “the very integrity

of the fact-finding process. . . at p, 727. The ultimate

constitutional principle vindicated by Whitus and earlier

cases—the rights of a Negro criminal defendant to fair

and impartial jury selection procedures—is such a rule.

Some of the very practical dangers which the rule guards

against were alluded to by this Court more than eighty

years ago:

“The very fact that colored people are singled out and

. . . denied . . . all right to participate in the adminis

tration of the law, as jurors, because of their color . . .

is practically a brand upon them . . . an assertion of

their inferiority, and a stimulant to that race prejudice

which is an impediment to securing to individuals of

the race that equal justice which the law aims to secure

to all others.

# « #'

“ It is well known that prejudices often exist against

particular classes in the community, which sway the

judgment of jurors, and which, therefore, operate in

some cases to deny to persons of those classes the full

enjoyment of that protection which others enjoy.”

Strauder, supra, at pp. 308, 309.

The integrity of juries and jury selection procedures go

to the heart of the fact finding process. The fact of Negro

exclusion from juries is evidence of the very prejudice

which a Negro defendant on trial for his life must be pro

tected against. Whitus v. Balkcom, supra. The chronic

absence of Negroes on juries—although they comprise a

substantial percentage of the population—is evidence to

an all-white jury of official complicity in perpetuating racial

bigotry. The fairness of the trial of a Negro criminal

15

defendant—particularly where, as in this case, the charge

is murder of a white person—in such circumstances is

severely jeopardized by an atmosphere of officially sanc

tioned pre-judgment.

Petitioner was tried and convicted by a grand and petit

jury from which Negroes were racially excluded in viola

tion of his rights under the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Accordingly, his conviction should

be reversed. Strauder v. West Virginia, supra; Pierre v.

State of Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 (1939); Jones v. Georgia,

supra; Cobb v. Georgia; Anderson v. Georgia, supra; Sul

livan v. Georgia, supra.

II.

There Was No Valid Waiver by Petitioner of His

Constitutional Might to Challenge the Elbert County

Prospective Juror Selection Procedures.

Petitioner challenged the selection procedures of the

juries which indicted and tried him for the first time

on petition for writ of habeas corpus. The United States

District Court of the Middle District of Georgia dis

missed the application without prejudice, on the ground

that petitioner had failed to exhaust his state remedies.

Until recently, the State of Georgia, through its courts,

"imposed rigid, sometimes technical restrictions” on such

applications for writ of habeas corpus. Peters v. Rutledge,

397 F.2d 731, 737 (5th Cir., 1968).12 * 14 In 1967 the Georgia

legislature enacted a habeas corpus act which created a

12 For other eases in which the Fifth Circuit has alluded to the

difficulties concerning such applications, see McGarrah v. Dutton,

381 F.2d 161, 165 (5th Cir., 1967) ; Mobley v. Dutton, 380 F.2d

14 (5th Cir., 1967); Whippier v. Balkcom, 342 F.2d 388 (5th Cir.,

1965) ; Smart v. Balkcom, 352 F.2d. 502 (5th Cir., 1965) ; C oll v.

Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1964).

16

right of collateral attack based upon claims not previously

raised.13 The explicit purpose of Georgia’s Habeas Cor

pus Act of 1967, and the standards of valid waiver which

it sets forth have led the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit to presume that “ the new Act seems to have

expressly adopted the federal standard of waiver.” Peters

v. Rutledge, supra, at p. 737.14 13 14 *

13 “ Be it Enacted by the General A ssembly of Georgia :

“ Section 1. Statement of Legislative Intent and Purpose. The

General Assembly finds that expansion of the scope of habeas corpus

in federal court by desisions [sic] of the United States Supreme

Court, together with other decisions of said court (a) substantially

curtailing the doctrine of waiver of constitutional rights by an

accused and (b) limiting the requirement of exhaustion of state

remedies to those currently available, have resulted in an in

creasingly larger number of state court convictions being col

laterally attacked by federal habeas corpus based upon issues and

contentions not previously presented or passed upon by courts

of this State; that such increased reliance upon federal courts

tends to weaken state courts as instruments for the vindication

of constitutional rights, with a resultant deterioration of the fed

eral system and federal-state relations; that to alleviate said

problems, it is necessary that the scope of state habeas corpus be

expanded and the state doctrine of waiver of rights be modi

fied . . Laws, 1967, p. 835.

“ Section 50-127 . . .

“ (1) Grounds for Writ. Any person imprisoned by virtue of

a sentence imposed by a state court of record who asserts that

in the proceedings which resulted in his conviction there was a

substantial denial of his rights under the Constitution of the

United States or of the State of Georgia of the laws of the State

of Georgia may institute a proceeding under this Section. Rights

conferred or secured by the Constitution of the United States shall

not he deemed to have been waived unless it is shown that there

was an intentional relinquishment or abandonment of a known

right or privilege which relinquishment was participated in by

the party and was done voluntarily, knowingly and intelligently.”

Laws, 1967, p. 836 (Emphasis added).

14 After the Act went into effect the federal courts modified

their earlier practice with respect to collateral attack of Georgia

judgments and adopted a stringent rule of exhaustion of state

remedies. Peters v. Rutledge, supra; Green v. Myers, 401 F.2d

890 (5th Cir., 1969); Rearden v. Smith, 403 F.2d'773 (5th Cir.

17

The Superior Court ruled that petitioner’s habeas peti

tion was “without merit” because the challenge to the

array had not been raised by trial counsel (E. 72). The

Court took no account of trial counsel’s testimony as to

the circumstances which compelled his silence beyond

noting that: “ Counsel for the accused stated that he did

not challenge the array because he thought it was best

not to raise that point” (R. 72).

The Supreme Court of Georgia noted the holding of

the Superior Court:

“ The court held that [the claim] was without merit

since there was no challenge to the array when the

appellant was tried” (4a).

However, the Georgia Supreme Court does not appear

to have rested its decision on that ground because it pro

ceeded to discuss the applicability of Whitus to the merits

of petitioner’s claim. I f the Supreme Court of Georgia’s

decision does rest on an affirmance of the Superior Court’s

finding that Brawner waived his right, it is clearly con

trary to the factual record and should be reversed.16

Whether a federal right has been waived is a federal

question. Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963). It is an

established constitutional principle that a valid waiver is

an “intentional relinquishment or abandonment of a known

right or privilege.” Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458, 464

(1938).

16 A state court determination, as a matter of discretion, of a

federal constitutional question raised at a late stage of a case does

not preclude this court from assuming jurisdiction and deciding

whether state court action in the particular circumstances was,

in effect, an avoidance of a federal right. Williams v. State of

Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 (1955).

18

“ [Cjourts indulge every reasonable presumption

against waiver of fundamental constitutional rights,”

and “ do not presume acquiescence in the loss of fun

damental rights.” Johnson v. Zerbst, at p. 464.

A choice made by counsel not participated in by the

petitioner does not automatically bar relief. Fay v. Noia,

supra; and see United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304

F.2d 53 (5th Cir. 1962), cert, denied 372 U.S. 924 (1963).

In this case petitioner’s trial counsel did not consult with

him on the question of whether or not a challenge to jury

selection procedures should be made (R, 113, 119). Fur

thermore, it cannot be said, on the basis of the record,

that trial counsel’s forebearance was based on “ strategic,

tactical, or any other reasons that can fairly be described

as the deliberate by-passing of state procedures.” Fay

v. Noia, supra, at p. 439.

The factual circumstances surrounding the question of

waiver in this case are materially identical to those which

obtained in the case of Whitus v. Balhcom, 333 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1964).16 The Court of Appeals found the fol

lowing facts concerning the alleged waiver by Whitus:

The two Negro petitioners were tried in the Superior

Court of Mitchell County, Georgia, for the murder

of a white farmer. They were convicted and sen

tenced to die. Mitchell County is a small county in

rural Georgia. No Negro has ever served on a grand

jury or on a petit jury in Mitchell County. The at

torneys for the petitioners were fully aware of this

fact. They were also fully aware of the hostility that

an attack on the all-white jury system would generate

in a community already stirred up over the killing.

16 Affirmed sub nom. Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967).

19

Without consulting the defendants, the attorneys de

cided not to object, in the trial or on appeal, to the

systematic exclusion of Negroes from either jury.

At p. 498.

Brawner’s trial counsel was fearful of the harmful

effects to his client were he to raise the jury discrimina

tion issue (R. 119) and his decision to remain silent was

dictated by that fear.

In such circumstances there is a strong inference that,

counsel was no less fearful of likely harmful effects to his

own social and professional life. United States ex rel.

Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71 (5th Cir., 1959) cert,

denied 361 II.S. 838 (1959). The Fifth Circuit has taken

judicial notice of the fact “ that lawyers residing in many

southern jurisdictions rarely, almost to the point of never,

raise the issue of systematic exclusion of Negroes from

juries.” Goldsby, at p. 82.

The reality of Brawner’s trial counsel’s decision to re

main silent is identical to that which was found and suc

cinctly summarized by the Fifth Circuit in Whitus v.

BaVkcom, supra, at pp. 498-499:

“ The petitioners and their attorneys had no desire

to give up their right to be tried by a jury chosen

without regard to the race of the jurors. It was not

to their interest to do so—except as a choice of evils.

A choice of evils was indeed the only state remedy

open to them. The petitioners could choose to be

prejudiced by the hostility an attack on the all-white

jury system would stir up. Or they could choose to

be prejudiced by being deprived of a trial by a jury

of their peers selected impartially from a cross-sec

tion of the community. This is the ‘grisly’, hard,

20

Hobson’s choice the State puts to Negro defendants

when it systematically excludes Negroes from juries;

white defendants are not subjected to this burden.

“ The constitutional vice is not just the exclusion of

Negroes from juries. It is also the State’s requiring

Negro defendants to choose between an unfairly con

stituted jury and a prejudiced jury. We hold that

this discrimination violates both the equal protection

and the due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.”

The ruling of Georgia’s Supreme Court is diametrically

opposed to the ruling of the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit in Whitus v. Balhcom, supra, and to the

ruling and disposition of that case by this Court. In

Whitus, the Fifth Circuit undertook a painstaking ex

amination and discussion of the development and applica

tion of the federal rule of waiver, and carefully analyzed

the facts of that case in the context of its discussion of

the rule. In its opinion, the Supreme Court of Georgia

does neither, and completely ignores the factual identity

of the two cases. The Court also completely ignores the

consistency of the Whitus ruling with earlier Fifth Circuit

opinions in strikingly analogous cases. See United States

ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, supra; United States ex rel.

Goldsby v. Harpole, supra; Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698

(5th Cir., 1966). Conflict has thus been engendered be

tween two judicial systems in a matter of fundamental

constitutional importance and that conflict can only have

deleterious effects on the development of the federal

waiver rule and on the relationship between state and

federal courts unless it is promptly resolved by this Court.

Pearce v. North Carolina, 372 U.S. 937 (1963).

21

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons a writ of certiorari should

be granted and the judgment below reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Norm an C. A makeb

James N. F inney

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H oward Moore, J r.

Peter E. R indskopf

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioner

APPENDIX

302

Supreme Court of Georgia

Decided May 8, 1969

25131. Brawker v. Smith, Warden.

1. The order of the court was a final judgment from which

an appeal could be taken.

2. The case of Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (87 SC

643, 17 LE2d 599), will not be given retroactive appli

cation in a case in which no challenge to the array of

jurors, on the ground of racial discrimination, was made

at the time of the appellant’s trial.

3. The court did not abuse its discretion in determining

that incriminatory statements of the appellant, intro

duced in evidence on his trial, were voluntarily made

after he had been fully advised of his constitutional

rights.

Opinion and Judgment of the

Supreme Court of Georgia

2a

Mobley, Justice. This appeal is from a judgment in a

habeas corpus case. The appellant was convicted of murder

and given a death sentence on March 9, 1965. The judge

hearing the habeas corpus proceeding made findings of

fact and law, and determined that the appellant’s convic

tion was not invalid on any ground made in the habeas

corpus petition, but found that his sentence was illegal

under the rulings made in Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391

U.S. 510 (88 SC 1770, 20 LE2d 776), because jurors had

been excused for cause by reason of their conscientious

opposition to capital punishment. The order noted that the

Witherspoon case had been followed by this court in Miller

v. State, 224 Ga. 627 (8) (163 SE2d 730); and Arkwright

v. Smith, 224 Ga. 764 (1) (164 SE2d 796).

It was stated in the order as follows: “In fashioning a

remedy this court is aware that the full entitlement set

forth in the decision of the Supreme Court of Georgia will

require independent judicial action by the original sen

tencing court, i.e., the Superior Court of Elbert County,

Georgia. The court has been advised that the competent

authorities in Elbert County are prepared to initiate such

action. Rather than enter an order declaring invalid the

custody under which petitioner is currently being held,

it is the court’s opinion that the smooth administration of

justice will be best furthered by a stay of these habeas

corpus proceedings pending compliance by the Superior

Court of Elbert County with the directions contained in

the Witherspoon, Miller and Arkwright cases cited above

herein.”

It was then ordered: that the “proceedings in this matter

be stayed for a period not to exceed 90 days. . that

the respondents be restrained and enjoined from carrying

Opinion and Judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia

3a

out the sentence of death by execution, and from quarter

ing the appellant in that portion of the Georgia State

Prison set aside for those awaiting execution; and that

the appellant “be remanded to the custody of the respon

dent who is directed to arrange for the return of petitioner

to the lawful authorities of Elbert County, Georgia for

retrial, the only question to be decided by the court upon

retrial will be the sentence imposed upon the verdict as

stated in the Witherspoon case and in the Miller case.”

1. The respondent has filed a motion to dismiss the ap

peal on the ground that the order appealed from is not a

final judgment. There is language in the order which in

dicates that this is true. However, the order decides all

questions made in the case, and no provision is made for

any further determination in the matter on a future hearing.

If the judge trying a habeas corpus case involving a per

son whose liberty is being restrained by virtue of a sen

tence imposed by a State court of record finds in favor of

the petitioner, he is authorized to “ enter an appropriate

order with respect to the judgments or sentence in the

former proceedings and such supplementary orders as to

rearraignment, retrial, custody, bail or discharge as may

be necessary and proper.” Ga. L. 1967, pp. 835, 836 (Code

Ann. §50-127 (7)). The judge in the present case exer

cised this authority by ordering the remand of the appel

lant to the custody of the warden, who was directed to

arrange for his return to the lawful authorities of Elbert

County for retrial on the question of his sentence only.

The only question before the court was the validity of

the present confinement and the sentence under which he

was restrained, and the judge had no authority to deal

with a future imprisonment under another sentence. Balk-

Opinion and Judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia

4a

com v. Craton, 220 Ga. 216, 218 (138 SE2d 163); Balkcom

v. Hurst, 220 Ga. 405 (139 SE2d 306); Dutton v. Knight,

223 Ga. 140 (153 SE2d 714). He had no authority to exer

cise any supervisory control over the appellant. His duty

had been discharged when he made his findings of law and

fact, and remanded the appellant to the custody of the

warden, with directions that he be returned for retrial

on the question of his sentence in the Superior Court of

Elbert County. It was thus a final judgment, and one

from which an appeal could be taken.

2. The first and second enumerations of error contend

that the court erred in denying the appellant’s petition for

writ of habeas corpus on the ground that his conviction

and sentence are unconstitutional under the due process

and equal protection clauses of the United States Consti

tution because the appellant, a Negro, was indicted by a

grand jury, and tried by a traverse jury, illegally com

posed due to racial discrimination. The court held that

this ground was without merit since there was no challenge

to the array when the appellant was tried.

The appellant introduced in evidence figures from the

Census of 1960, showing the number of white and non

white persons living in Elbert County; the composition

of the jury lists at the time of the appellant’s trial, which

were selected from segregated tax digests, and the dis

parity between the percentages of Negroes in the county,

and on the tax digests, and the Negroes on the jury lists

at the time of the appellant’s trial. It is contended that

under the ruling of the Supreme Court of the United States

in Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (87 SC 643, 17 LE2d

599), this constituted prima facie evidence of purposeful

discrimination.

Opinion and Judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia

5a

The Whitus ease was decided January 23, 1967, nearly

two years after the appellant’s trial. In Strauss v. Grimes,

223 Ga. 834, 835 (158 SE2d 404), this court held: “We do

not believe that retroactive application of the Whitus case,

385 U.S. 545, supra, is required in the present case, where

the grand jury indictment was returned December 22,

1964, and no challenge was made to the composition of the

grand jury at the time of the trial, but was first made in

a post conviction habeas corpus proceeding.” It was

pointed out that retroactive application of the Whitus case

could bring about disastrous results, making it possible

that persons convicted many years ago of serious crimes

might establish racial discrimination in the selection of the

juries trying them, to which no challenge was made, and

because of the inaccessibility of witnesses to again indict

and convict them, these dangerous criminals would be

turned loose upon society. Certiorari was denied in Strauss

v. Grimes, supra, 391 U.S. 903 (88 SC 1651, 20 LE2d 417).

See also Massey v. Smith, 224 Ga. 721 (1).

The court did not err in denying this ground of the

petition for habeas corpus.

3. The third enumeration of error contends that the

appellant’s conviction and sentence are unconstitutional

under the due process and equal protection clauses of the

United States Constitution because “a confession was in

troduced in evidence against him which was involuntarily

given in the absence of counsel.”

At the hearing the appellant testified: He was 23 years

of age at the time he was indicted. He finished high school

at the age of 20. He did not know the meaning of the

words “ freely and voluntarily,” “ remote,” “benefit,” and

“coercion.” At the time he made statements to the law

Opinion and Judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia

6a

enforcement officers he had not been advised that any

thing he said would be used against Mm, or that he would

be furnished free counsel. He had been struck on the head

during the incident in which the homicide occurred, and

had lost blood from this wound. When the officers were

talking to him his head was hurting “ real bad,” and he was

tired, cold, and hungry.

The depositions of L. Adger Moore, Sheriff of Elbert

County, and George Ward, Chief of Police of Elberton,

were introduced in evidence. Both testified that: Prior to

the time they questioned the appellant, they told him that

he did not have to make any statement to them, that he

could remain completely silent, that if he did make a state

ment, it could and probably would be used against him,

and that he was entitled to an attorney, and that if he

did not have the money to hire an attorney, the judge

would appoint him an attorney at no cost to him. The

appellant replied that he was ready to talk to them and

that he did not need a lawyer. His statements were made

without the offer of any reward or relief to induce him to

make the statements, and without any threats to him 0r to

any members of his family.

Under this conflicting evidence, the judge was authorized

to find that the appellant had been advised of his consti

tutional rights prior to making the oral statements which

were introduced in evidence on his trial for murder. The

evidence does not show such coercive circumstances as to

render the incriminatory statements inadmissible in evi

dence, and it was not error to deny this ground of the

appellant’s petition for habeas corpus. Compare Frazier v.

Warden, U.S. (No. 643, October Term, 1968, decided April

22, 1969).

Judgment affirmed. All the Justices concur.

Opinion and Judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia

7a

Denial of Rehearing by the Supreme Court of Georgia

Clerk ’s O ffice , S upreme C ourt op G eorgia

Atlanta May 22,1969

Dear Sir:

Case No. 25131, Curtis Brawner v. The State

The motion for a rehearing was denied today.

D u ck w o rth , C.J., dissents and dissents from judgment

rendered May 8, 1969.

Yours very truly,

H enry H . C obb, Clerk

Order also entered this date staying the remittitur pend

ing petition to the Supreme Court of the United States.

PER

8a

Letter From Prof. John S. deCani

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

P hiladelph ia 19104

Wharton School of

Finance and Commerce

D epartm ent of S tatistics

and Operations R esearch

August 15, 1969

James N. Finney, Esq.

c /o NAACP Legal Defense Fund

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Dear Mr. Finney:

In answering your questions, I take the following as

given:

1. The United States Census for 1960 shows the popula

tion of Elbert County, Georgia, aged 21 and over to be

composed of 7317 white persons and 2817 non-white per

sons.

2. The Elbert County, Georgia, Tax Digest for 1963

contains the names of 4760 white persons and 971 non

white persons.

3. The Elbert County Jury Revision of August, 1963,

contains the names of 2021 white persons and 26 non

white persons on the combined Traverse and Grand Jury

Lists.

9a

Letter From Prof. John S. deCani

Assuming the combined jury list was selected at random

from the 1960 population aged 21 and over, the probability

of 26 or fewer non-white names out of a total of 2047

names is 2.35 x 10-279, which can be written as a decimal

followed by 278 zeroes and the number 235.

Assuming the combined jury list was selected at ran

dom from the 1963 Tax Digest instead of from the popula

tion aged 21 and over, probability of 26 or fewer non

white names out of a total of 2047 names is 1.04 x 10“162,

which can be written as a decimal followed by 161 zeroes

and the number 104.

I believe that any competent statistician, faced with the

same data, would conclude that the combined jury list

was not selected at random from either the population

aged 21 and over or the Elbert County Tax Digest for

1963.

Sincerely yours,

/ s / J o h s S. deCani

John S. deCani

Associate Professor

JSdeC :rms

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219