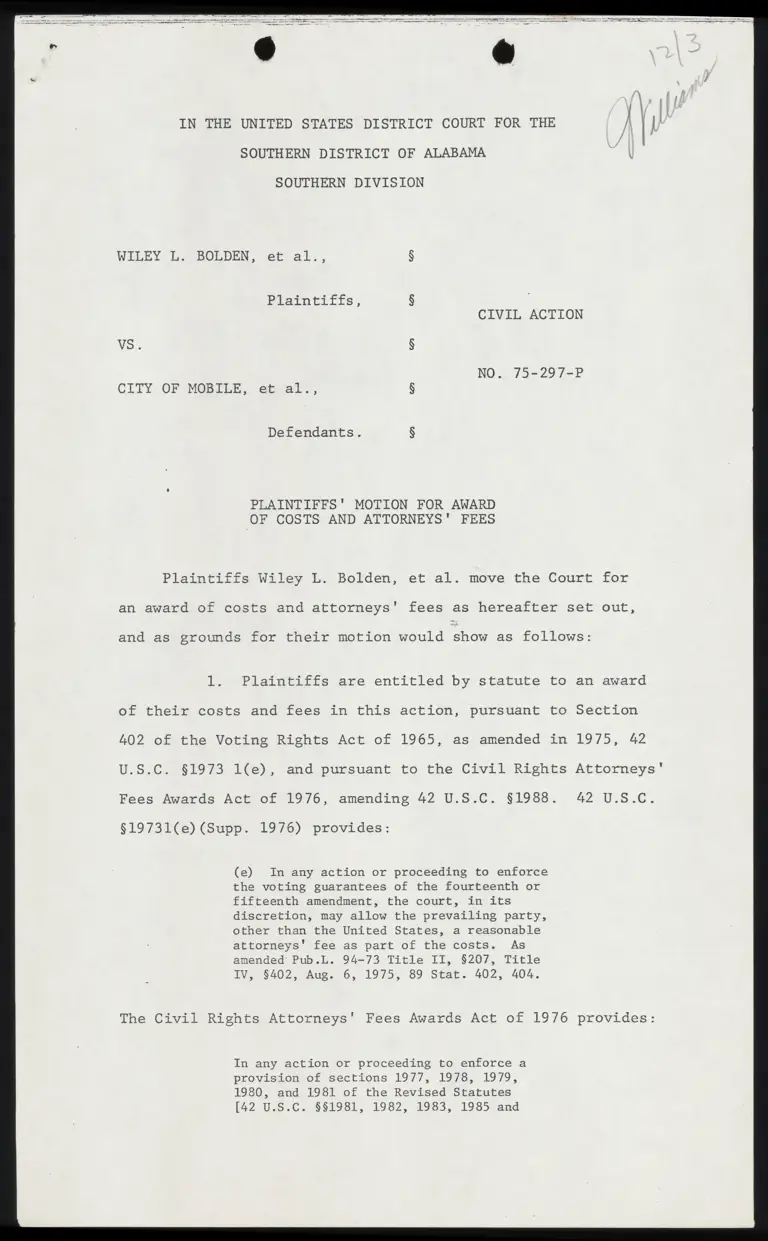

Plaintiffs' Motion for Award of Costs and Attorneys' Fees

Public Court Documents

December 3, 1976

85 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Plaintiffs' Motion for Award of Costs and Attorneys' Fees, 1976. 9fb86f54-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4428406f-c525-40e1-86e7-9a848209e5f3/plaintiffs-motion-for-award-of-costs-and-attorneys-fees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE / ¥

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et zl., §

Plainriffs, §

CIVIL ACTION

NS, §

NO. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, et al,., §

Defendants. §

PLAINTIFFS' MOTION FOR AWARD

OF COSTS AND ATTORNEYS' FEES

Plaintiffs Wiley L. Bolden, et al. move the Court for

an award of costs and attorneys' fees as hereafter set out,

and as grounds for their motion would show as follows:

1. Plaintiffs are entitled by statute to an award

of their costs and fees in this action, pursuant to Section

402 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended in 1975, 42

U.S.C. §1973 1(e), and pursuant to the Civil Rights Attorneys’

Fees Awards Act of 1976, amending 42 U.S.C. §1988. 42 U.S.C.

§19731(e) (Supp. 1976) provides:

(e) In any action or proceeding to enforce

the voting guarantees of the fourteenth or

fifteenth amendment, the court, in its

discretion, may allow the prevailing party,

other than the United States, a reasonable

attorneys' fee as part of the costs. As

amended Pub.L. 94-73 Title II, §207, Title

IV, 8402, Aug. 6, 1975, 89 Scat. 402, 404,

The Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Awards Act of 1976 provides:

In any action or proceeding to enforce a

provision of sections 1977, 1978, 1979,

1980, and 1981 of the Revised Statutes

[42 0D.8.C. §51981, 1982, 1933, 1985 and

ep meses Vow me i SABA IER 50 BA rs AT dr TNR TT SNA ps rr mn Ts Kr AAI EC te am he TT pam ht a do cm en a TL ei m3 we a a A eS Tn mn i

1986], title IX of Public Law 92-318, or in

any civil action or proceeding, by or on

behalf of the United States of America, to

enforce, or charging a violation of, a

provision of the United States Internal

Revenue Code, or title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, the court, in its

discretion, may allow the prevailing party,

other than the United States, a reasonable

attorney's fee as part of the costs.

2. The legislative history of Section 402 of the

Voting Rights Act specifies that the amount of fees to be

awarded under that Act "be governed by the same standards

which prevail in other types of equally complex Federal

litigation, and not be reduced because the rights involved

may be non-pecuniary in nature." S.Rep.No. 94-295, pp. 41-42,

94th Cong., lst Sess. (1975). Even more detailed guidance

is provided the courts by the House and Senate Reports for

the Civil Rights Attorneys' Fee Awards Act of 1976, S.Rep.No.

94-1011, 94th Cong., 2nd Sess. (June 18, 1976), and H.Rep. No.

94-1558, 94th Cong., 2nd Sess. (September 15, 1976), copies

of which are attached to this motion. > The legislative

histories of both attorney fee statutes cite with approval

the guidelines set out in Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

Inc., 438 F.24 714 (5th Cir. 1974), and single out as

decisions wherein these guidelines are properly applied

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 P.R.D. 680 (M.D. Calif. 1974);

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 99444 (C.D. Calif.

1974); and Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklinburg Board of Education,

66 ¥.R.D. 483 (W.D. N.C. 1975).

3. The time and labor required, as of the date this

motion is filed, are shown by the attached affidavits of

Edward Still, J. U. Blacksher, Larry Menefee and Gregory B.

Stein.

4. The novelty and difficulty of the questions

presented in this action were exceptional. The decision of

the case required an application of accepted constitutional

principles to a hitherto unlitigated set of facts. However,

—— tt ean tl A ti

”~

federal courts have acknowledged that these established

constitutional principles in the area of voter dilution present

inherently novel and difficult questions; each case must be

considered as 'a blend of history and an intensly local

appraisal of the design and impact of the multi-member district

(under scrutiny) in light of the past and present reality,

political and otherwise." White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755,

769-770 (1973). Additionally, there were two controlling legal

issues in this case for which no established legal precedents

were provided by established caselaw: the effect of Washington

v. Davis, _ U.S. , 96 S.Ct. 2040, 48 L.Ed.2d 597 (1976), on

voting rights litigation and the proper application of

unconstitutional vote dilution principles to a city commission

form 6f government. The Court should not overlook in this

regard the fact that this case has been of great national

importance and has, as the court put it in Swann, supra, 66

F.R.D. at 485, "become a political football of nationwide

attention.”

>

o~

5. The skill requisite to perform the legal service

properly must be judged by the Court.

6. The preclusion of other employment due to

acceptance of this case has not been a significant factor with

respect to Edward Still and J. U. Blacksher. However, by

virtue of the fact that at least during the period from

January thru July 1976 in excess of one half of his time was

devoted to the preparation of this case, Larry Menefee was

effectively precluded from other employment available to him.

7. The customary fee. The novelty of the legal

issues in this litigation makes it impossible to rely entirely

on the history of customary fees in other cases. Stanford

Daily, supra, 64 F.R.D. at 682. Generally speaking, hourly

rates in federal courts run from $30.00 or $35.00 an hour up

to 2 or 4 times that figure. Swann, supra, 66 F.R.D. ‘at 486.

Attached to this motion are affidavits of other lawyers

testifying to the rates that prevail generally with respect

a Ee oa sere out itt ee ea a a Ca Eo Ar ee

to litigation in federal court. Immediately relevant to the

determination of a customary fee with respect to the instant

litigation are the fees paid to opposing counsel. Swann,

supra, 66 F.R.D. at 485. Opposing counsel filed answers to

interrogatories on or about October 13, 1976, stating that

the City of Mobile had as of that date been billed in excess

of $85,000.00, representing payment for opposing counsel's

services on a noncontigent basis at the rate of $50.00 per

hour. Opposing counsel has further represented that in light

of the fact they were billing a public client $50.00 an hour

is below their usual rate for this type of federal litigation.

Perhaps more indicative of the customary fee isthat which the

City of Mobile recently announced it has agreed to pay Mr.

Charles Rhyne, namely, $10,000 retainer plus $100.00 per hour.

Furthevaore, unlike opposing counsel, plaintiffs’ counsel

have had considerzble experience with civil rights litigation

which has allowed them to utilize their time more economically.

Stanford Daily, supra, 64 F.R.D. at 684-85.

8. Whether the fee is fixed or contigent. Plaintiffs

have not entered into any contract with their attorneys for

payment of fees. Plaintiffs' counsel have prosecuted this

action on a completely contigent basis, dependent upon the

successful outcome of the lawsuit. Where the chances of

recovering attorneys' fees at the beginning of litigation

appear slight, the normal amount of attorneys' fees should be

increased. Stanford Daily, supra, 64 F.R.D. at 682. At the

time this action was filed, the chances of plaintiffs’

recovering attorneys' fees were made even less likely by the

absence of the subsequently enacted 1975 amendments to the

Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Fees Awards Act of

1976. Plaintiffs' counsel have been reimbursed costs only

in the amount of $1,500.00 by the Non Partisan Voters League

of Mobile County and in the amount of $3,183.68 by the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., a non-profit legal

oly

aid organization which has as its primary purpose the advocacy

of the rights of black people in the courts. The Legal

Defense Fund has also, compensated local counsel on a nominal

basis in the amount of $2,850.00. However, local counsel are

obligated to reimburse the Legal Defense Fund the amounts

advanced them in the event they recover costs and attorneys’

fees, and these advancements should in no way diminish the

fees and costs to be awarded by this Court. Swann, supra,

66 F.R.D. at 486.

9. The amount involved and the results obtained.

As in Swann, supra, 66 F.R.D. at 484, "[t]he results obtained

were excellent and constituted the total accomplishment of

the aims of the suit." Although no damages were sought or

recovered in this action, Congress intended that the amount of

fees awarded not be reduced because the rights involved may

be nonpecuniary in nature. S.Rep.No.94-1011, supra, p.6.

The results obtained were of great public importance and

obtained protection of the voting rights of black citizens

of Mobile. The Supreme Court has uniformly characterized the

right of suffrage as one of the most fundamental rights in

a free and democratic society, preservative of other basic

civil and political rights. Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533,

12 L.Ed.2d 506 (1964).

10. The experience, reputation, and ability of the

attorneys. The experience of counsel for plaintiffs are

set out in the affidavits attached to this motion. Mr. Still

and Mr. Blacksher are two of the most experienced civil rights

attorneys in the State of Alabama, and Mr. Still has handled

more reapportionment and voting rights cases than perhaps

any other attorney in Alabama.

11. The "undersirability" of the case. That civil

rights cases such as the instant one are "undersirable'" to

most attorneys is best evidenced by the relatively few members

of the Mobile Bar who have brought such cases in this Court.

a nn i a er a. lt At a ER ee SRL rt mt i 0 an, Hm sm EF iene st BR a ee ian

12. None of plaintiffs' counsel has had a professional

relationship with these plaintiffs prior to this action.

13. Awards in similar cases. Plaintiffs refer the

Court to the cases cited in the congressional history of the

two attorneys' fees statutes. They assess attorneys' fees

computed on the basis of the prevailing rate in the area for

comparable litigation and then increased the amount by a

"bonus" to take account of such factors as the contigency of

the litigation, the skill and experience of counsel, the

novelty and importance of the issues involved, and the

excellence of the results achieved. Thus in Stanford Daily,

supra, 64 F.R.D. at 688, the Court multiplied counsel's total

hours, by an average rate of $50.00 per hour, then added a

bonus of 26.6% of the computed amount. In Davis v. County of

Los Angeles, supra, (a copy is attached to this motion) the

court computed fees at the average rate of $60.00, $55.00,

and $35.00 per hour for three different attorneys with varying

experience, then increased their total award by a bonus factor

of 17.6%. On the other hand, in Swann, supra, 66 F.R.D. at

485-86, the Court did not apply a bonus factor, but awarded

counsel a total of $175,000.00 at an average rate of

approximately $65.00 per hour.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray that the Court will award them

attorneys' fees computed as follows: One half of the hours

attributable jointly to Bolden and Brown plus all of the hours

attributable only to Bolden times the hourly rate for each

attorney plus a bonus equal to 25% of the total

Attorney «3x Joint Bolden Hourly Rate Total

Edward Still 46.75 + 184.4 x. $75.00 = $17,336.25

J.U. Blacksher 34.15 + 327.5 = 75.00 = 27,123.75

Larry T.Menefee 210.0 + 263.7 = 60.00 = 28,422.00

Gregory Stein -- 34.0 x 60.00 - 2,040.00

Sub Total : :

Bonus 18,730.50

Fees for Services Rendered

up to the date of this Motion $93,652. 50

y - - -_ - _- SE - _. i,

a EE —_— I i bis A at Te se a Xo an NR NS Ev mali oe RR iis me mc sah i. oc. i Ue a te et en mh Ei Tr re Al IAA: Sg ml 5 ep i tn A el er mp a i tt

Plaintiffs further pray that the Court award them their

actual expenses incurred to date in the prosecution of this

action computed as follows: All of the expenses attributed

only to Bolden case and one-half of those expenses attributable

jointly to Bolden and Brown.

Expenses Bolden 3% Joint Total

J. U. Blacksher $911.47 $5,045.52 $5,956.99

Edward Still 224.80 387.83 612.63

Respectfully submitted this the 8th day of December, 1976.

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

' MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

Y TE J

By: \ JL J ita beltts,

J« U. BLACKSHER

L.ARRY MENEFEE

GREGORY B. STEIN

EDWARD STILL, ESQUIRE

SUITE 601 - TITLE BUILDING

2030 THIRD AVENUE, NORTH

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 35203

JACK GREENBERG, ESQUIRE

CHARLES WILLIAMS, III., ESQUIRE

SUITE 2030

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE

NEW YORK, N., Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this the 8th day of December,

1976, I served a copy of the foregoing PLAINTIFFS' MOTION FOR

AWARD OF COSTS AND ATTORNEYS' FEES upon counsel of record,

Charles A. Arendall, Esquire, David Bagwell, Esquire, Post

Office Box 123, Mobile, AL 36601 and S. R. Sheppard, Esquire,

City of Mobile, Legal Department, Mobile, AL 36602, by depositing

same in United States Mail, postage prepaid.

™N/" // J 7

AN Jolt sleatr i

[rraraey for Plaintiffs

/

Tw

61 7-3-74 3

Center, that the Act prohibits involuntary retirement.

pursuant to a pension plan before age 65. As noted in text,

plaintiff did not take this position in the district court. X

s In his only afTidavit in opposition to defendants’ motion

for summary judgment on the original complaint, plaintiff

simply stated a belief that the 1970 resolution was designed

to discriminate against older workers without indicating

the source of this belief. :

» As noted earlier, Judge Tyler dismissed this claim for

want of subject matter jurisdiction, holding that

§§302(c)3) and (e) of the Tait-Hartley Act, 29 USC.

§ §186(c)(5) and (e), did not confer jurisdiction upoa the

federal courts to entertain a suit alleging mal-adminis-

tration—as distinguished from structural defects—in

covered pension plans. Whether this was a proper char-

Cases Cited "8 EPD 1...” :

‘Davis v. County of Los Angeles -

5047

acterization of the law and what constitutes a structural

defect raise difficult and complicated issues. Com

Snider v. All State Administrators, Inc, 481 F.2d 387 (5th

Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 94 S.Ct. 771 (1374), and Bowers v.

Ulpiano Casal, Inc, 393 F.2d 421 (1st Cir. 1968), with

Lewis v. Mill Ridge Coals, Inc., 298 F.2d 552, 558 (6th Cir.

1962) (dictum), Lugo v. Employees Retirement Fund, 366

F. Supp. 99 (E.D.N.Y. 1973), and Porter v. Teamsters

Health Funds, 321 F. Supp. 101 (E.D. Pa. 1970). In view of

the insubstantiality of plaintiil’s case on the merits, we

express no opinion on these issues.

10 The principal additional piece of evidence proffered was

a letter from the president of the union to another retiree

seeking to return to work. This letter says essentially that

reinstatement of retirees is not practical given the financial

structure of the pension plan. :

Ed

[19444] Van Davis

Defendants. . —

1974. » is

N ie

Attorney’s Fees—Amount of

2000e-5(f).

Back reference.—§ 2580.

Title VII suit were employed

different procedure for affixing attorney's

i

n

e

Counsel, for Defendants. =. a

g

e

judgment, both entered July 20, 1973 and

reported at 7 E.P.D. 19088 that defendants

had engaged in discriminatory employment

practices based on race and national origin,

violative of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, as amended 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq.

(“Title VII”). :

e

a

AE

S

L

Se

R

A

T

Sh

PT

Ten

A

R

I

N

0

i

w

plaintiffs thereafter filed a motion re-

i questing an award of reasonable attorneys’

z] fees as provided for at 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(f).

= 3 Affidavits and briefs relevant to that motion

were received from both plaintiffs and

Nt

Employment Practices

et al, Plaintiffs v. County of Los Angeles

* United States District Court, Central District of California. No. 73-63-WPG. June 5;

: _ .° -. Title VII—Civil Rights Act of 1964 = ~~ = = = =

Award—Factors to Consider.—An amount in

addition to the attorney's fees awarded for the number of hours spent on a case which proved

race and national origin bias in a local fire department was to be awarded based on the-

difficulty of the issues in the case. the conduct of the case and the results achieved. Hourly

compensation was to include compersation for time reasonably spent on issues which did not

ultimately appear in the case or on which the suing party did not prevail. 42 U.S.C. See.

A. Thomas Hunt, Mary D. Nichols, Center

California and Stuart P. Herman, Los Angeles, California, for Pla intiffs.

Gray. DJ: This court found in a finding

of fact and conclusion of law and in a

Pursuant to the terms of that judgment,

et al."

AER - -

ae Abad SY org ~~ s LA

—t NE

~ oN

Attorney’s Fees—Parties Entitled Thereto.—The fact that attorneys bringing a

by a non-profit public interest law firm did not indicate a

: fees. The public interest reasons for awarding

te attorney’s fees in Title VII cases required their award regardless of the status of the

EE § prevailing attorneys. 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2000e-5(f). :

id Back reference.—% 2580. hay

Awarding attorneys’ fees in (DC Cal. 1973) 7 EPD 19088.

For Law In The Public Interest, Los Angeles,

John H. Larson, Acting County Counsel, and William F. Stewart, Deputy County

defendants. A brief amicus curiae in support

of plaintiffs was submitted by the Los

Angeles County Bar Association. A hearing.

was held on March 25, 1974, at which expert

testimony was received. This Court has

reviewed and considered all affidavits, briefs,

and evidence received, and makes the follow-

ing Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law:

Findings of Fact

1. Plaintiffs were the prevailing parties in-

this action. The class represented by plain-

tiffs has received and is receiving substantial

and significant benefits as a result of the

5048 Employment Practices Decisions 61 73-74:

Davis v. County of Los Angeles

commencement of this action and the final

judgment herein, which provides that forty

percent (40%) of all new firemen hired at

the County of Los Angeles Fire Department

shall be black and Mexican-American until

such time as the percentage of blacks and

Mexican-Americans in the fire department

workforce is equal to the percentage of

blacks and Mexican-Americans in the

County of Los Angeles.

2. Plaintiffs’ attorneys have submitted a

bill for attorneys’ fees and disbursements

herein, requesting compensation for the

following number of hours:

A. Thomas Hunt

Stuart P. Herman . 99.60

Mary Nichols 100.50

The Court accepts as valid the number of

hours billed by Messrs. Hunt and Herman.

Because of deficiencies in the timekeeping

practices of Ms. Nichols, the Court reduces.

her time to 75 hours. :

3. A. Thomas Hunt, plaintiffs’ lead attor-

546.25

ney, is an able and experienced litigator in

the alfidavits received and the expert testi-

mony heard, plaintiffs’ counsel will be

compensated at the following rates per hour:

i A. Thomas Hunt $69.00

Stuart P. Herman $55.00

Mary Nichols $35.00

4. More than one of plaintiffs’ counsel

attended the trial and several of the

depositions. The Court finds that. =. certain

amount of this constituted unnecessary

duplication of effort by plaintiffs’ counsel.

Therefore the award to plaintiffs’ counsel is

reduced by $1,000.00.

5. Plaintiffs’ counsel also have submitted

a bill for $1,757.68 for disbursements,

including transcripts, and a bill for

$1,511.00 for expert witness fees. These

charges were not challenged by defendants

and are valid.

6. Plaintiffs’ counsel also have submitted

a bill for 967 hours of statistical analysis,

legal research, transcript summarization,

interviewing, and general assistance carried

out by a law clerk and a paralegal assistant.

Plaintiffs’ counsel request $10.00 per hour

for these services. This Tequest 1s valid and

appropriate and the plaintiffs’ counsel shall

receive $9,670.00 for services performed by

their paralegal and law clerk assistants.

[Bonus Award]

7. Plaintiffs’ counsel in this leved

excellent results for the plaintiffs and the

represented class. The nature of the case

made it difficult to litigate. With these

considerations in mind, as well as the

Court’s observations of the conduct of plain-

tiffs’ attorneys throughout the case, an

award of fees above the normal hourly rates

is appropriate; the appropriate amount to be

awarded above the normal hourly rates is-

$7,193.32. -

8. The total amount to be awarded plain-

tiffs as attorneys’ fees therefore totals

$60,000.00, as follows: -

(a) Attorneys’ Time 340,868.00

Less duplication =

=. $39,868.00

1,757.68

L511.00

. 9,670.00

(b) Disbursements

(c) Expert Witness Fees :

(d) Paralegal and Law Clerk

(e) Result Charge 7.0 br

TOTAL \ $60,000.00

Conclusions of Law ~

1. The award of attorneys’ fees to the

‘prevailing party in Title VII cases is

appropriate. Attorneys’ fees are to be

awarded in order that attorneys will be

encouraged to act as “private attorneys-gen-

eral” vindicating the strongly expressed

Congressional policy against discrimination

based on race and national origin. Newman

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, [2 EPD 19834}

390 U.S. 400, at 402 (1968); Schaeffer v.

San Diego Yellow Cab, [4 EPD % 7882] 462

F 2d 1002, at 1008 (9th Cir. 1972);

Robinson v. Lorillard Corporation, [3 EPD

18267] 444 F 2d 791, at 804 (4th Cir.,

1971); NAACP v. Allen, [4 EPD £7669]

340 F Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala. 1972).

2. The factors to be considered in

computation of the appropriate amount of

the award include the time spent by the

attorneys, the difficulty of the case, the skill

requisite to perform the legal service

properly, the fee customarily charged in the

locality for similar legal services, the results

achieved, the experience, reputation, and

ability of the attorneys performing the

services. Code of Professional

Responsibility, Disciplinary Rule 2-106;

Clark v. American Marine Corp., [3 EPD

18113] 437 F 2d 959 (5th Cir, 1971),

adopting [2 EPD 710,228] 320 F Supp. 709

(E.D. LA. 1970); Johnson v. Georgia High-

way Express, Inc, (7 EPD 19079] 488 F 2d

714, (5th Cir., 1974). “The amount of the

award should not be such that it would dis-

courage others from seeking to attack

discriminatory practices.” Schaeffer v. San

Diego Yellow Cab, (4 EPD ¢ 7882] 462 F 24

1002, at 1008 (9th Cir, 1972). ply

[Public Interest Firm} ~~

3. In determining the amount of the fees

to be awarded, it is not legally relevant that

©1974, Commerce Clearing House, Inc.

1,000.00-

7,193.32

P=

a

61 7-3-74 Cases Cited "8 EPD 1...” 5049

U.S. v. Masonry Contractors Assn. of Memphis, Inc.

plaintiffs’ counsel other than Mr. Herman.

are employed by the Center for Law In The

Public Interest, a privately funded non-

profit public interest law firm. It is in the

interest of the public that such law firms be

awarded reasonable attorneys’ fees to be

computed in the traditional manner when

its counsel perform legal services otherwise

entitling them to the award of attorneys’

fees. Clark v. American Marine Corporation,

[3 EPD 18113] 437 F 2d 959 (5th Cir,

1971), adopting {2 EPD 110,228] 320 F

Supp. 709, at 711 (E. D. La. 1870); Miller v.

Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F 2d 534

at 538-9 (5th Cir., 1970); La Faza Unida v.

Volpe, 57 FR.D. 94 at 93, Ft. 6 (ND. Cal,

1972). ’

4. It also is not legally relevant that plain-

tiifs’ counsel expended a certain limited

amount of time pursuing certain issues of

fact and law that ultimateiv did not become

litigated issues in the case or upon which

plaintiffs ultimately did not prevail. Since

plaintiffs prevailed on the merits and

achieved excellent resuits for the

represented class, plaintiffs’ counsel are

entitled to an award of fees for ail time

reasonably expended in pursuit of the uit-

mate result achieved in the same manner

that an attorney traditionally is

compensated by a fee-paying client for ait

time reasonably expended on a matter.

5. The determination of the amount of

attorneys’ fees to be awarded necessarily in-

volves a balancing of many factors. Johnson

v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc, [7 EPD

%9079] 488 F 2d 714, (5th Cir. 1974). The

Court’s first hand observations of the

conduct of the case also is an important

consideration. United States v. Operating

Engineers, Local Union 3, 6 EPD 18964, at

p. 6034 (N.D. Calif., 1973). In this highly

subjective area, “[t]here is no micrometer of

reasonableness.” Clark v. American Marine

Corporation, [2 EPD 110,228} 320 F Supp.

709, at 712 (E.D. La., 1970), adopted at [3

EPD 18113] 437 F 2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971).

In arriving at the $60,000.00 award made in

this case, the Court has attempted to balance

the many relevant factors in as fair a way as

possible.

Judgment

The Court in{fs"Judgment herein entered

July 29, 1973, ruled that plaintiffs are

entitled to an award of reasonable attorneys’

fees. In accordance with the Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law Re Attoneys’ Fees

made and entered simultaneously herewith,

It is Hereby Ordered, Adjudged and

Decreed that:

1. Plaintiffs’ counsel herein are entitled to

and shall recover from Dfendant County of

Los Angeles the sum of $60,000.00 as

attorneys’ fees, costs, and disbursements in

this action.

" 2. The payment to plaintiffs’ counsel shall

be made within thirty days of the date of

entry of this judgment. Interest shall not

begin to accrue if Defendant County of Los

Angeles makes the said payment within

thirty days after entry of this Judgment He

Attorneys’ Fees.

[79445] United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellee v. Masonry Contractors

Association of Memphis, Inc. et al., Defendants-Appellants. No. 73-1567.

Same v. John H. Moore and Sons, Inc., Defendant-Appellant. No. 73-1568.

United States Court of Appeals, Sixth Circuit. June 11, 1974.

Division.

On Appeal from United States District Court, Western District of Tennessee, Western

Title VII—Civil Rights Act of 1964

Court Action—Racial Discrimination—Construction Industry—Joinder of

Parties.—In an Attorney General suit for race bias in the construction industry it was not

necessary to join all the contractors employing bricklayers and tilesetters in the geographical

area. It was sufficient to sue only the major contractors named in the suit and the federal

civil procedure rules did not require joinder of any other contractors. 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2000e.

Back reference.—% 2510.

Attorney General Suit—Prerequisites.—The only prerequisite for a bias suit by the

Employment Practices

® » Se bo ap a

- 1 % RY i > MoE E rd y Calendar He. 955 PE he

04TH CONGRESS t SENATE Rivore os ills

2d Session | No. 94-1011 EX AE san

CIVIL RIGHTS ATTORNEYS FEES AWARDS ACT [+ ” TP

R

d

:

~

~

"

n

g

s

J

£1

50

ge

JUNE 29 (legislative day. June 18), 1U76.—Ordered to be printed

J

Mr. Tu~NnNEY, from the Committee on the Judiciary,

submitted the following

r PT, te rp 3 Ta

at o'tes Sen: NG 5 Fae

mie REPORT 2

P* Zafsie v TAREE Sach

5 a EE 3 [To accompany S. 2278] 1 . Bel, :

. ¥.. eT

I a... The Committee on the Judiciary, to which was referred the bill kf ved. yl

(S. 2273) to amend Revised Statutes section 722 (42 U.S.C. § 1988) Pr

to ailow a i in its discretion, to award attorneys’ fees to a pre-

veiling party In suits brought to enforce certain civil rights acts, having

: considered the same , reports favorably thereon and recommends that

the bill do pass.

rm »

The text of S. 2278 1s as follows:

S. 2278

Revised Statutes section 722 (42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983) is

+ amended by adding the following: “In any action or pro-

ceeding to enforce a provision of sections 1977 , 1978, 1979,

& 1980 and 1981 of the Revised Statutes, or Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, the court, in its discr etion, may allow the

prevailing party, other than the United States, a reasonable

attorney’s fee as part of the costs.”.

FERRE Purpose

fu Ee This amendment to the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Revised Statutes

1S . - Pa . . . . ’ 2’

AE Cea ia Section 722, gives the Federal courts discretion to award attorneys : 2

bof Swe tote ve id fees to revailing arties in suits brought to enforce the civil rights Phas Xn

ania oF APR Pp [=] ant 2

D8 Rm oF | acts which Congress has passed since 1866. The purpose of this amend- SRA

ab AE o : ment is to remedy anomalous gaps in our civil Tights laws created by

gata 2 the United States Supreme Court's recent decision in Alyeska Pipeline pa

Hi ESO a Service Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S. 240 (19253, and to achieve Eo

Pg CREEL ery ] consistency in our civil rights laws. . Fe 2

Rc Bo EX Be rg rh high i est SPA PRET .

3 , > BI

ah I 25 57-010 ER] Any re

Fri * Ea Ris

* “24 ¥ FOYT

Ll Fy

1 a

er STRATE Yo Nga x

a =

ns Tes ern an AD Kann

Nea EAESED EAR

CoC i a oR Sod Bon

5 fo) : eA re Roof IF

2 3, CA, .

i hen RCE ET Ea Ne a . x x y BE Sa ASN

Log AP ey Ae Sa

EIT Ft Torti SRSA Sn

d

e

a

,

.

.

.

»

B

B

RP

P

A

.

Se

i

Foie PAE Ad

® 3 »

History oF THE LEGISLATION

The bill grows out of six days of hearings on legal fees held before

the Subcommittee on the Representation of Citizen Interests of this

Committee in 1973. There were more than thirty witnesses, including

Federal and State public officials, scholars, practicing attorneys from

many areas of expertise, and private citizens. Those who did not

appear were given the opportunity to submit material for the record,

and many did so, including the representatives of the American Bar

Association and the Bar Associations of 22 States and the District

of Columbia. The hearings, when published, included not only the

testimony and exhibits, but numerous statutory provisions, proposed

legislation, case reports and scholarly articles.

In 1975, the provisions of S. 2278 were incorporated in a proposed

amendment to 5 1279, extending the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights specifically approved

the amendment on June 11, 1975, by a vote of 8-2, and the full

Committee favorably reported it on July 18, 1975, as part of S. 1279.

Because of time pressure to pass the Voting Rights Amendments, the

Senate took action on the House-passed version of the legislation.

S. 1279 was not taken up on the Senate floor; hence, the attorneys’

fees amendment was never considered.

On July 31, 1975, Senator Tunney introduced S. 2278, which is

identical to the amendment to S. 1279 which was reported favorably

by this Committce last summer.

Shortly thereafter, similar legislation was introduced in the House

of Representatives, including H.R. 9552, which is identical to S. 2278

except for one minor technical difference. The Subcommittee on

Courts, Civil Liberties and the Administration of Justice of the

House Judiciary Committee has conducted three days of hearings at

which the witnesses have generally confirmed the record presented to

this Committee in 1973. H.R. 9552, the counterpart of S. 2278, has

received widespread support by the witnesses appearing before the

House Subcommittee.

Ee

a

a

t

STATEMENT

The purpose and effect of S. 2278 are simple—it is designed to allow

courts to provide the familiar remedy of reasonable counsel fees to

revailing parties in suits to enforce the civil rights acts which Congress

as passed since 1866. S. 2278 follows the language of Titles II and VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 20002-3(b) and 2000e—

5(k), and section 402 of the Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1975,

42 U.S.C. §19731(e). All of these civil rights laws depend heavily upon

private enforcement, and fee awards have proved an essential remedy

if private citizens are to have a meaningful opportunity to vindicate

the important Congressional policies which these laws contain.

In many cases arising under our civil rights laws, the citizen who

must sue to enforce the Ro has little or no money with which to hire a

lawyer. If private citizens are to be able to assert their civil rights, and

if those who violate the Nation’s fundamental laws are not to proceed

with impunity, then citizens must have the opportunity to recover

what it costs them to vindicate these rights in court.

S.R. 1011

HN,

= = es Cant pod

- DETFDN RES

ar HE eh a Ns Wi

ol 3 SpE

Les mae

CEA ree

se ; fo SIR,

SEW Mn TN ar A hn, Fr NR oy I Ran Wel (55 LS Tu ert

- oo Lad

Ena EA A TI

SE ERS AE TI RF Sr AA Tra =

> A Ta

— ay ag HAR

d

a

g

bi

tL Le

I

f

Fr

Pn PENS,

Ee Py ET

aA

AAT

LAL ey Sim 3 SEER

. -.

3

- Congress 9... this need when it made gots in for

such fee shifting in Titles IT and VII of the Civil Rights ACt of 1964:

When a plaintiff brings an action under [Title II] he cannot

recover damages. If he obtains an injunction, he does so not

for himself alone but also as a ‘‘private attorney general,”

vindicating a policy that Congress considered of the highest

priority. If successful plaintiffs were routinely forced to bear

their own attorneys’ fees, few aggrieved parties would be in &

osition to advance the public interest by invoking the

Injunctive powers of the Federal courts. Congress therefore

enacted the provision for counsel fees—* * * to encourage

individuals injured by racial discrimination to seek judicial

relief under Title II.” Newman Vv. Piggie Park Lnterprises,

Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968).

The idea of the ‘‘private attorney general” is not a new one, nor

are attorneys’ fees a new remedy. Congress has commonly authorized

attorneys’ fees in laws under which “private attorneys general” play 2

significant role in enforcing our policies. We have, since 1870, author-

izad fee shifting under more than 50 laws, including, among others, the

Securities Exchange Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. §§ 78i(c) and 78r(a), the

Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1958, 38 U.S.C. § 1822(b), the

Comrounications Act of 1934, 42 U.S.C. § 206, and the Organized

Crime Control Act of 1970, 18 U.S.C. § 1964(c). In cases under these

laws, fees are an integral part of the remedy necessary to achieve

compliance with our statutory policies. As former Justice Tom Clark

found, in a union democracy suit under the Labor-Management

Reporting and Disclosure Act (Lendrum-Griffin),

Not to award counsel fees in cases such as this would be

tantamount to repealing the Act itself by frustrating its basic

= * * * Without counsel fees the grant of Federal

tion is but an are * * *. Hall v. Cole, 412

an empty gestur

1973), quoting 462 F. 2d 777, 780-81 (2d Cir. 1972).

emedy of attorneys’ fees has always been recognized as par-

.

ticularly appropriate in the civil rights area, and civil rights and

2

attorneys’ fees have always been closely interwoven. In the civil rights

area, Congress has instructed the courts to use the broadest and most

3 A effective remedies available to achieve the goals of our civil rights

Eg EE fdws.! The very first attorneys’ fee statute was a civil rights law, the

AS FIRS XT Soy Enforcement Act of 1870, 16 Stat. 140, which provided for ¢torneys’

a fees in three separate provisions protecting voting richts.?

Modern civil rights legislation reflects a heavy reliance on attorneys’

fees as well. In 1064, seeking to assure full compliance with the Civil

Rights Act of that year, we authorized fee shifting for private suits

establishing violations of the public accommodations and equal

employment provisions. 42 U.S.C. §§ 20002-3(b) and 2000e=5(k).

Since 1064, every major civil rights law passed by the Congress has

included, or has been amended to include, one or more fee provisions.

—

1 For example, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 directed Federal courtsfto ‘use that combination of Federal law,

common law and State law as will be best adapted to the object of the civil rights laws.” Brown v. City of

Aferidian, Mississippi, 356 F. a 602, 505 (5th Cis. 1966). Seo 42 U.S.C. § 1988; Lefton v. City of Hattiesburg,

Mississippi, 333 F. 2d 280 (5th Cir. 1084).

;

3 The causes of action established by these provisions wero eliminated in 1894. 28 Stat. 33.

p

r

0

o

r

PO

T

S

A

Y

-

4

a yu

:

>

S.R. 1011

: > PINE Roa EL =

= SEES.

SEs nd NT Ae Sop oS See ETA

TOR og Se

mt CA en > 2 3 As Tao PIT & DN A fs TA Rey SA Sr S30

pro

[SAVER EN mag

Sa

Ip one rate T ; vd ns A AT : eS Eras

a

For iE

ANS An STN

7 Pardons HAN T Re SNE TR

ATR A

Ow WOR, ~~ ry rile . ES 3 ” TAN

a SEE RR EYE ed ARN 2 2X 2) x SAR Nr 2 ¥

Te

p Sas Sr 14

r

»

rd; = On,

aA

ARTE Gare FOR

. i

al J gL EY

i. vi WB og pi" fn

XT Ne 4 a a :

ws, - RTE St 3 Ei SI

Fommey ier 4)

eR oir Solis Ow

| - », . . ~ >

Yep * " -

bs * 3. Hit .

ER TC la te}

$e" a :

[= Cea ar NL LE

: ’ 1 id

’ 4 :

a————e

.X Re oe yn ”

y: J

i -

A

R

P

:

L

r

.

GH

H

A

E

r

g

Ar:

or, YX. -

a

® ;

E.g., Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1868,

the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972, 20 U.S.

Employment Amendments of 1972, 42 U.S.C. §

Voting Rights Act Extension of 1975, 42 U.S.C. § 19731(e).

These fee shifting provisions have

vigorous enforcement of modern civil rights legislation, while at the

were Important enough to merit fee shifting under the “private

attorney general” theory. The Court expressed the view, in dictum,

that the Reconstruction Acts did not contain the necessary congres-

sional authorization. This decision and dictum created anomalous gaps

in our civil rights laws whereby awards of fees are, according to Alyeska,

suit brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1931, which proteéts similar rights but

involves fewer technical prerequisites to the Sling of an action. Iees are

allowed in a housing discrimination suit brought under Title VIII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1968, but not in the same suit brought under 42

U.S.C. §1982, 2 Reconstruction Act protecting the same rights. Like-

wise, fees are allowed in a suit under Title IT of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act challenging discrimination in a private restaurant, but not in suits

under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 redressing violations of the Federal Constitu-

tion or laws by officials sworn to uphold the laws.

This bill, 5. 2278, is an appropriate response to the AZyeske decision.

t 1s limited to cases arising under our civil rights laws, a category

of cases in which attorneys fees have heen traditionally regarded as

appropriate. It remedies gaps in the language of these civil rights

laws by providing the specific authorization required by the Court in

Alyeska. and makes our civil rights laws consistent.

It is intended that the standards for awarding fees be generally the

same as under the fee provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. A party

seeking to enforce the rights protected by the statutes covered by

S. 2278, if successful, “should ordinarily recover an attorney's fee

unless special circumstances would render such an award uninst.”

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968).

3 These civil rights cases aro too numerous to cite here. Sce, c.g.. Sims v. Amos 340 F. Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala. 1972), af’d, 469 U.S. 942 (1972); Slenford Daily v. Zurcher, 366 F. Supp. 18 (N.D. Cal. 1973); and cases cited in Alreske Pipeline, supre, at 1. 46. Many of the relevant cases are collected in “‘ITearings on the Effect of Legal Fess on the Adequacy of Xepreseutation Before the Subcoin. on Representation of Citizen Interests of the Senate Cornm. on the Judiciary,” 93d Cong., 1st sess., pt. ITT, at pp. 888-1024, and 1060-62. 4 In the large minjorily of cases the party or parties seeking to enforce such rights wiil be the plaintitls and/or plainlifkintervenors. However, in the procedural posturo of sone cases, tho partivs seeking to enforce ple may be the defendants and/or defendant-intervenors. See, ¢.8., Shetley v. Araemer, 234 U.S.

Ss. Jot

42 U.S.C. § 3612(c);

C. § 1617; the Equal

2000e~16(b); and the

w—

-

.

T

E

E

Y

r

se

y

r

g

ey

re

.

at

£ £ Aw NS

. I

a’ sv,

: RE ETE Re N A 1 vw

S35 -, 2a 3

-~ 4 . Fi

. Su + -

3 ti .

37

>

3 ’ oY,

he

h

dr

2

ta

t

kf

i

S

A

L

A

w

#

n

o

b

,

a

«4

g

2%

~~

~ a ™

Ap

PA pe ie

PR AR eg

1. Psy

» Ba

- ; Ca pt

* ts ci da nd Set 3

Ra 72 — i iy ITER aa AEE 4 a. ERR Wo i ls 3 med 3

ot ing tae tt Bid ltd § Dot St KF Reno Be ST a » LV,

~~ - tg Ye hgh 1 cl Fas) E 3

5 --e 2d A]

’ . . : 014, ~ ~ =. is :

4 - pole TR =. BY FF yr. - te pi 2rd Ue wt Ad ; Py or rg v

«rb at - Ig [1 ete Ld n A o-

no ii rol Ya ee

F Ad - < i ard aii Ve, A » ar - %;

hE) Ta - Far

LJ 3 - Ot

2 : I : - i a

ad

J is *: sami 2 RIC eo Sa rs) Noid, pF ra . A = ey en AT ARC AS rn vA ey "als ‘ AGT iif 2 2. re 32a Se TE Fei ol SERPENT) we 2 K To ne ag By de “4 Ip? - BAe, et oD

ha? hy) P A 4 3 Ta y - - av ORS RA RS Se Ter SSE ey A AN ET

ns

No

rn

|

.

J

ed

e

s

w

i

c

e

p

aie

uy

A

g

e

,

p

n

d

i

BL

SR

5

ON iz va re

SY ew TY

~

~

NW

ov

rd

At

pe

pv

e

W

n

o

m

e

L

X

F.

¥

Fp

ee

——

—,

0

Such “private attorneys general’ should not be deterred from bringing

good faith actions to vindicate the fundamental rights here involved

7 the pros of having to pay their opponent’s sel fees should

they lose. Richardson v. Hotel Corporction a 332 F. Supp.

519 (E.D. La. 1971), aff'd, 468 F. 2d 951 (5th Cir. 1972). (A fee award

to a defendant's employer, was held unjustified where a claim of racial

ciseriniination, though meritless, was made in zood faith.) Such a

fg . . N . SC ————— party. if nnsuccesstul. could be assessed his opponent's Tee only where

it is shown that his suit was cicarly frivolous, vexatious. or brought for

hargss ses. United States Steel Corp. v. United States, 385

F. Supp. 346 (W.D. Pa. 1974), afi’d, 9 E.P.D. 9 10,225 (3d Cir. 1975).

This bill thus deters frivolous suits bv authorizing an award of

attorneys’ fees against a party shown to have litigated in “bad faith”

under the guise of attempting to enforce the Federal rights created

by the statutes listed in S. 2278. Similar standards have been followed

not only in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but in other statutes providing

for attorneys’ fees. E.g., the Water Pollution Control Act, 1972 IIS,

Code Cong. & Adm. News 3747; the Marine Protection Act, Id. at

4249-50; and the Clean Air Act, Senate Report No. 91-1196, 91st

Cong., 2d Sess., p. 483 (1970). See also Hutchinson v. William Barry,

Irc., 50 F. Supp. 292, 298 (D. Mass. 1943) (Fair Labor Standards

Act).

In appropriate circumstances, counsel fees under S. 2278 may be

awarded pendente lite. Sec Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Ruchmona, £16 U.S. 656 (1974). Such awards are especially appropriate

where a party has prevailed on an important matter in the course of

» even when he ultimatelv does not prevail on all issues. litigation.

See Bradley, supra; Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375

0). Moreover, for purposes of the award of counsel fees, parties

7 be considered to have prevailed when they vindicate rights

2 consent judgment or without formally cbtaining relief.

Kopet v. Esquire Realty Co., 523 F. 2d 1005 (2d Cir. 1975), and cases

cited thersin; Parham v. Southwestern Bell T. elephone Co., 433 IF. 2d

(8th Cir. 1970); Richards v. Griffith Rubber Mills, 300 F. Supp.

338 (D. Ore. 1969); Thomas v. Honeybrook Mines, Inc, 428 F. 2d

981 (3d Cir. 1970); Aspira of New York, Inc."v. Board of Education

Oo e

)

smn or not the agency or government is a named party).

3 See, e.z., “Hearings on the Eflcct of Legal Tees,” supra.

$ Fairmont Creamery Co. v. Minnesota, 275 U.S. 163 (1927).

? Proof that an official had acted in bad faith could also rencler him liable for fees in hisitdividual capacity,

under the traditional bad ith standard recoznizad by the Supreme Court in Aly-2ka. Sco Class v. Norton,

S05 F. 2d 123 (2d Cir. 1974); Doe v. Poclker, 515 F. 2d 541 (8th Cir. 1975).

S.R. 1911

- :

' xi n- -e” 4 3 ur > z Ra

¥en: d

H - °F [J

i. vr 2 RE

Ponte 500%

t J : wipirtle, Foil y

: AT >

: alle -

i LL = 4

ar

t

y

e

f

Ww

e

y

i

0

B

E

d

a

i

d

E

e

d

d

d

SL

a

LE

R

H

R

D

a

h

ENA Raat 8) ¢ TNT IR A a

TE Vo SY Fim Yon A Ar vn py i, TN

NH — Cy aia Rd

me re me or an NT nt a A | — A rs Ta nk a go vr a me mean s mw PA so gpg on pt te ta

governed by the same standards which prevail in other types of equall

: fom lex Fe 2 otigation, such as £00trust cases and not be reduced

ecause the rights involvaq may be no lary in nature. The

appropriate standards, see Johnson Y. Georgia Highway Express,

488 F. 2d 714 (5th Gir. 1974), Ir 4 ed in such cases as

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 T'.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal T9742 ; Dams v.

County of Los Angeles, SE.PD. « 9444 (C.D. Cal. 1974); and Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C.

us

1975). These cases have resulted in fees whic] are adequate to attract.

ompetent coun but whic not pr ¢ windfalls to attorneys.

In computing the fee. counsel for prevailing parties should be paid, as

is traditional wit attorneys compensated by a fee-paying client, “for

all time reasonably expended on 2 matter.” Dayis, supra; Stanford

Daily, Supra, at 634.

: his bill ‘creates no startling new remedy—it only meets the

Federal courts are to continue the practice of awarding attorneys’

fees which had been going on for years prior to the Court's May

ecision. It does not change the statutory provisions regarding the

Protection of civil rights except as it provides the fee awards which P" :

Bre necessary if citizens are to be able to effectively secure compli- fore

&nce with these existing statutes. There are very few provisions in our ;

OL governmental action and, in some cases, on private action through

al

:

. ‘le courts. If the cost of private enforcement actions becomes too

: , . , Rh

Citizen cannot enforce, we must maintain the traditionally effective

remedy of fee shifting in these cases.

a i : CaaNeEs Iv Exrsrrvg Law Mabe BY tem Bing ARE ITALICIZED

3 i x :

.

frites i

REVISED STATUTES § 722, 42 u:s.c, § 1983 |

i

1

:

{ : i

ili

'

; : ‘The jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters conferred on the :

t

B

h

3

protection of all persons in the United States in their civil rights, and

yfor their vindication, shall be exercised and enforced in conformity

with the laws of the United States, so far as such laws are suitable

to carry the same into effect; but in al cases where they are not

adapted to the object, or are deficient in the provisions necessary to

furnish suitable remedies and punish offenses against law, the common

law, as modified and changed by the constitution and statutes of the

tate wherein the court having jurisdiction of such civil or criminal

cause is held, so far as the same’ is not inconsistent with the Consti-

tution and laws of the United States, shall be extended to and govern

the said courts in the trial and disposition of the cause, and, if it is

ANE

1 Py \ ay. red

: Br £

Sew = ee wn —

vu Rights Act of 1964, the court, in its discretion, may allow the pre-

vailing party, other than the United States, a reasonable attorney's fee

S.R. 1011

. 3 4

i A TR

.

{

.

EE

yg

>

¢ ow Tt Re oa =

3

RS nO RT

.

oe on " hyo a

SNE

Raa

ig

:

I

; = - »

Lada Te NS

me A

i

—— A NT ra < EPCRA

TOA TL ta =

Ee

emer: Se

a A ae = as Rs Loy PRESET

AR

= on ~ Re” Pa? TY a Tet

fo . - rar 2 Ben Sl pg pate SRA TTA SA [Prine iE hy A gh 3 " uaa ore NR i

3 Er TT Re Ro A a SI Ren 2 a

REE pO rm ad eS

ET

or

3 I aE

Te ea, As A Se Cra wom CAPE whe TEEN Sw Aa a.

. i

3 Sa SA EA de a

Hp

>

wg

—

Ae

a N

on wh Pd ny

kd FW SERESATE Lip Soy

, @

Cost oF LEGISLATION

T]

E

n

n

a

i

PP

OT

U

P

O

R

-

The Congressional Budget Office, in n letter dated March 1, 1978, has advised the Judiciary Committee that: “Pursuant to Section 403 of the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, the Congressional Budget Office has reviewed S. 2278, 2 bill to award attorneys’ fees to prevailing parties in civil rights suits.

“Based on this review, it appears that no additional costs to the i would be incurred as a result of the enactment of this bi hid

EER

. id ee »

Oo

LE a Sli, 3

} | eZ 5 E

Ji a

:

3 5 -

»

T

E

P

“0

0

.

$4

Aoi, En

Lal la

:

tS

2

t

*

:

$

3

be

S

g

EP

“4

4

S.R. 1011 7s oT fr

— Hog) TA = Crm Fa = Pe A a pa BE a — vas es ran RE Net EES Ee nn ME oh ee SER a XA TEAS TEV TTT

or . So > Tie ? 3 2 iit a il : EYL

¢

it . ~~. . A ty ; : es A AT Ad

his oo : . CALS Te (ae LR a WA : 4 RO “5 . ; % . . a \ H

' re

. ’

. .

% ‘ 2 wo tev:

ely ;

«2 Say ne i . , ; - ant 75 ize 3 . - SE ~ : ta =

+ . - -~ - . -

. a

hed

5 py ERRATA

Er An A ND Lar a ny 3

Sr mo 2

AA WE eta

g Cay

ES { Eo Fe Tm IN,

Pp Se Rd SA >on NE Cm vO NA x)

TAL AST] WC ER

0) nt

Po ERY

Ere A,

— a 5. - - ~

4tx CONGRESS H : i “25 H, R. 15460 + IN.

IN Tid HOUSE OI REPRESIHNTATIVES

Skrreder 8, 1976

Mr. DranaN (for himself, Mr. Kasrenareier, Mr. Daxterson, Mr. Babirro,

Mr. Parrison of New York, Mr. Ramssack, and Mr. Wiceins) introduced

the following bill; which was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary

| ES Hid

> Pog fre way

A BILL

. To allow the awarding of attorney’s fees in certain civil

rights cases.

3. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Llepresenta-

2 tes of the United States of dmerica in Congress assembled,

3 “That this Act may be cited as “The Civil Rights Attorney’s

4 Tees Awards Act of 1976”.

Sec. 2. That the Revised Statutes section 722 (42 dd od U.S.C. 1988) is amended by adding the following: “In

v

o

b

AV

E

A

C

E

R

S

Ar

A

Te)

oy

we

AT

E

&

A

Y

xe

Ld

+

BK

C

ag

p

RI

nil

ha

s

de

ad

)

1977,:1978, 1979, 1980, and 1981 of the Revised Statutes,

H

h

¥ &

-

9)

6

7 any action or proceeding to enforce a provision of sections

8

1 title IX of Public Law 92-318, or title VI of the Civil Rights

10 Act of 1964, the cowrt, in its discretion, may allow the

11 prevailing party, other than the United States, a reasonable

12 attorney’s fee as part of the costs.”.

3

HA

LO

W

{e

ne

re

+

e

g

w

in

p

a

g

i.

a.

-

an

S

h

a

r

0

1d

[

y

a

.

B

I

S

T

i y

y

5

o

r

s

m

R

r

y

TY

a

w

te:

3

A

5

.

1]

A O

A

Bs

I

v

e

ia

d

.

»

»

~

~

0

g

,

-

n

s

0

a

t

le

a

i

h

LR

S

E

T

I

At

CF

0 A

t

hat

in

: 941 Coxcress | HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ! _ Report

2d Session No. 94-1538

THE CIVIL RIGHTS ATT ORNEY'S FEES AWARDS ACT

"OF 1976

PU

RE

VI

L

AP

PR

C

u

p

P

R

E

B

L

E

S

Y

SeEpTEMBER 15, 1976.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the

State of the Union and ordered to be printed

Mr. DRINAN, from the Committee on the Judiciary,

. i submitted the following

: | REPORT

[Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office]

F

P

P

R

T

I

E

T

SO

R

[To accompany LR. 13460]

The Committee on the Judiciary, to whom was referred the bill

(H.R. 15460) to allow the awarding of attorney’s fees in certain civil

rights cases, having considered the same. report favorably thereon

without amendment and recommend that the bill do pass.

Purpose oF THE Bin

H.R. 15460, the Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Avionds Act of 1976,

authorizes the courts to award reasonable attorney fees to the prevail-

ing party in suits instituted under certain civil rights acts, Under

existing law, some civil rights statutes contain counsel fee provisions,

while others do not. In order to achieve uniformity in the remedies

provided by Federal laws guaranteeing civil and constitutional rights,

1t 1s necessary to add an attorney fee authorization to those civil rights

acts which do not presently contain such a provision.

4 The effective enforcement of Federal civil rights statutes depends

? largely on the efforts of private citizens. Although some agencies of

the United States have civil rights responsibilities, their authority and

resources are limited. In many 7 instances where these laws are violated,

it is necessary for the citizen to initiate court action to correct the

illegality. Unless the judicial remedy is full and complete, it will

remain a meaningless right. Because a vast majority of the victims

of civil rights violations cannot afford legal counsel, they are unable

to present ‘their cases to the courts. In authorizing an award of reason-

able- attorney’s fees, H.R. 15460 is designed to give such persons

effective access to the: judicial process where their griev ances can be

resolved according to law.

57-006

o

w

.

r

e

»

I

g

o

a

ra

'

i

t

o

af

r

a

l

ad

mt,

ol

FIPRL

T

TO

RT

PE

RR

Y

(YP

o

P

Pe

h

b

00

tt

m

a

v

e

n

Et

he

NE

i

Sl

C

n

a

b

n

a

n

»

sab

!

ie

NEN

S

O

Y

.

PR

R

W

R

N

| Wd

PUT

RI

A

B

P

R

S

I

SA

PP

T

I

E

R

B

R

TR A I fn 3. al A TI IE WN WI Sat HT

2

STATEMENT

A. NEED FOR THE LEGISLATION

In Alyeska Pipeline Service Corp v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S. 240

(1975), the Supreme Court held that federal courts do not have the

power to award attorney’s fees to a prevailing party unless an Act of

Congress expressly authorizes it. In the Alyeska case, the plaintifls

sought to prevent the construction of the Alaskan pipeline because of

the damage it would cause to the environment. Although the plaintiffs

succeeded in the early stages of the litigation, Congress later over-

turned that result by legislation permitting the construction of the

pipeline. Nonetheless the lower federal courts awarded the plaintiffs

their attorney's fees because of the service they had performed in the

public interest. The Supreme Court reversed that award on the basis

of the “American Rule”: that each litigant, victorious or otherwise,

must pay for its own attorney.

Although the Alyeska case involyed only environmental concerns,

the decision barred attorney fee awards m a wide range of cases,

including civil rights. In fact the Supreme Court, in footnote 46 of

the Alyeska opinion, expressly disapproved a number of lower court

decisions involving civil rights which had awarded fees without

statutory authorization. Prior to A lyeska, such courts had allowed feces

on the theory that civil rights plaintifls act as © rivate attorneys

general” in eliminating discriminatory practices AL den affecting

all citizens, white and non-white. In 1968, the Supreme Court had

approved the “private attorney general” theory when it gave a gener-

ous construction to the attorney fee provision in Title II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. Newman v. I’iggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390

U.S. 400 (1968).2 The Court stated:

If (the plaintiff) obtains an injunction, he does so not

for himself alone but also as a “private attorney general,”

vindicating a policy that Congress considered of the highest

importance. / J at 402.

ITowever, the Court in Alyeska rejected the a plication of that

theory to the award of connsel fees in the absence of statutory author.

ization. It expressly reaflimed, however, its holding in Newnan that,

in civil rights cases where counsel fees are allowed hy Congress, “the

award should be made to the successful plaintiff absent exeeplionnl

circumstances.” Alyeska case, supra al, 262.

In the hearings conducted by the Subcommittee on Courts, Civil

Liberties, and the Administration of Justice, the testimony indicated

that civil rights litigants were suffering very severe hardships because

of the Alyeska decision. Thousands of dollars in fees were auto-

matically lost in the immediate wake of the decision. Representatives

of the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, the Council

1 The Court In Alycia recognized three very narrow exceptions to the rule (1) where n

“eammon fund” is involved: (2) where the iitigapt’s conduct Is vexatious, hargssing, or

tn bad faith: and (3) where a court order Is willfully dirobeyed.

21n Traficante v. Metropalitan Life Insurance Co., 400 U.8. 205 (1972), the Bupreme

Conrt applied the “private attorney general” theory In according broad standing’ tg pec-

fons injured by discriminatory housing practices under tlie Federal Fhir Housing Act, 42

U.S.C. 30601-3619.

3

for Public Interest Law, the American Bar Association Special Com-

mittee on Public Interest Practice, and witnesses practicing in the field

testified to the devastating impact of the case on litigation in the

civil rights area. Surveys disclosed that such plaintifls were the

hardest Lit by the decision.? The Committee also received evidence

that private lawyers were refusing to take certain types of civil rights

cases because the civi] rights bar, already short of resources, could not

afford to do so. Because of the compelling need demonstrated by the

testimony, the Committee decided to report a bill allowing fees to pre-

vailing parties in certain civil rights cases.

1t hid be noted that the United States Code presently contains

oyer fifty provisions for attorney fees in a wide variety of statutes.

See Appendix A. In the past few years, the Congress has approved

such allowances in the areas of antitrust, equal credit, freedom of in-

formation, voting rights, and consumer product safety. Although tho

recently enacted civil rights statutes contain provisions permitting

the award of counsel fees, a number of the older statutes do not. It is to

these provisions that much of the testimony was directed.

B. HISTORY OI H.R. 15460

At the time of the Subcomittee hearings on October 6 and 8, and

Dee. 3, 1975, three bills were pending which dealt expressly with coun-

sel fees in civil rights cases: IL.R. 7828 (same as ILI. 8220); H.R.

7969 (same as IL.R. 8742) ; and IR. 9552. ILR. 7828 and IL.R. 9552

would allow attorney fees to be awarded in cases brought under spe-

cific provisions of the United States Code, while H.R. 7969 would

permit such awards in any case involving civil or constitutional

rights, no matter what the source of the claim. ILR. 7828 was stated

in mandatory terms; H.R. 9552 and H.R. 7969 allowed discretionary

awards. The Justice Department, through its representative, Assistant

Attorney (leneral Rex Lee of the Civil Division, expressed its support

of ILI. 95562. Hearings held in 1973 by the Senate Judiciary Sub-

committee on the Representation of Citizen Interests also highlighted

the need of the public for legal assistance in this and other areas.

In August, 1976, the Judiciary Subcommittes on (fourts, Civil

Liberties, and the Administration of Justice concluded that a bill

to allow counsel fees in certain civil rights cases should he reported

favorably in view of the pressing need. On August 20, 1976, the Sub-

committee approved ILR. 9552 with an amendment in the nature of

a substitute because it was similar to S. 2278, which had cleared tho

Senate Judjciary Committee and was awaiting action by the full

Senate. The amendment in the nature of a substitute sought to conform

H.R. 9552 technically to S. 2278; no substantive changes were made.

It was then reported unanimously by the Subcommittee.

On September 2, 1976, the full Committee approved IL.R. 9552, as

amended, with an amendment offered by Congresswoman Ioltzman

and accepted by the Committee. That amendment added title IX of

Public Law 92-318 to the substantive provisions under which success-:

ful litigants could be awarded counsel fees. The Committee then

Balancing the Scales of Justice: Financing Pustie Interest Law in America (Coun- «il for Public Interest Law, 1970), pp. 238, 304, 1

4

ordered that a elean bill be reported to the TTouse. JLR. 15460, the

clean bill, was introduced on September 8 and approved pro forma

by the Committee on September 9, 1976.4

C. SCOPE OF TIIE BILL

11.R. 15460, the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976,

would amend Section 722 (42 U.S.C. 1988) of the Revised Statutes to

allow the award of fecs in certain civil rights cases.® It would apply to

actions brought under seven specific sections of the United States

.Code.® Those provisions are: Section 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985, 1986, and

2000d ot seq. of Title 42; and Section 1681 et seq. of Title 20. See

Appendix B for full texts. The affected sections of Title 42 generally

yrohibit denial of civil and constitutional rights in a variety of areas,

iil the referenced sections of Title 20 deal with discrimination on

Fcount of sex, blindness, or visual impairment in certain education

programs and activities.’ :

More specifically, Section 1981 is frequently used to challenge em-

ployment, discrimination based on race or color. Johnson v. Railway

Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454 (1975).8 Under that section the

Supremo Court recently held that whites as well as blacks could bring

suit alleging racially discriminatory employment practices. McDonald

v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., ——— U.S. ——, 96 S. Ct.

2574 (1976). Section 1981 has also been cited to attack exclusionary

admissions policies at recreational facilities. Z'illman v. Wheaton-

Haven Recreation Ass'n, Ine., 410 U.S. 431 (1973). Section 1982 is

regularly used to attack discrimination in property transactions, such

4 the purchase of a home. Jones v. Alfred IH. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409

(1968).9

Section 1983 is utilized to challenge official discrimination, such as

racial segregation imposed by law. Brown v. Board of I'ducation, 347

U.S. 483 (1954). It is ironic that, in the landmark Brown case chal-

lenging school segregation, the plaintiffs could not recover their attor-

0 fees, despite the significance of the ruling to eliminate oflicially

a

8 Apart from the addition of Title IX of Public Law 02-318, the only difference holwern

H.R. 9552 and the clean bill (IL.R. 15460) are technical, not affecting tho substance, mada

on ndvice of the House Parlinmentarian and staff and legislative counsel,

5 The bill amends the Revised Statutes rather than the United Htates Code boeanne THe

42 12 not codified, and thus Is not “the law of the United Staten,”

8 In accordance with applicable decisions of the Supreme Court, the bill In Intended to

anply to all eases pending on the date of enactment as well au all future eases, Headley v.

Richmond School Board, 416 U.S. 096 (1974).

“770 the extent a plaintiff joins a clalm under one of the atntules enumerated In TLR,

15460 with 1 elnlin {hat does not allow attorney fees, that plalntifr, if It prevails on the

hon-fee claim. 1s entitled to a determination on the other elntm for the purpose of awarding

connsel fees. Morales v. Haines, 486 I. 24 880 (7th Cir. 1073). In some instnnces, however,

the claim with fees may involve n constitutional question which the courts are reluctant to

resolve if the non-constittuional claim lis dispositive. Hagans v. Lavine, 415 1.8. 528

(1074). In such cases, If the elatm for which fees may be awarded meets the ‘“‘substan-

tinlity” test, see Hagansg v. Lavine, supra; I'nfted Mine Warkers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S, 715

(1966), attorney's fees may be allowed even though the court declines to enter Judgment for

The plaintiff on that claim, go long as the plaintiff prevalls on the non-fee clalm arising out

of a “common nucleus of operative fact” United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, supra at 725.

SACIth respect to the velntlonship hetween Sectlon 1081 and Title VIT of the Clvil

Riehts Act of 1064, the Tonse Committee on Wdventlon and Labor has noted that “the

remedies avallable to the individual under Title VII are co-extensive with the Indlvidunt’s

rieht to gue under the provisions of {the Civil Rights Act of 1RG6, 42 1.8. § 1081, and

that the two procedures augment each other and are not mutually exclusive!’ TLR. Rept.

No. 92-238. p. 19 (92nd Cong. Ist Sess. 1071). That view was adopled by the Supreme

Court In Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, rupra.

, "As with Section 1981 aud Title VII, Section 1982 and Title VIIT of the Clvil Rights

Act of 1968 are complemeniary remediés, swith similarities aud differences in coverage

and enforcement mechanism. See Jones v. Mayer Co., supra.

LY

5

imposed segregation. Section 1983 has also been employed to challenge

unlawful oflicial action in non-racial matters. For example, in 77 arper

v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966), indigent.

plaintiffs successfully challenged as unconstitutional the imposition:

of a poll tax in state and local elections. In Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S.

167 (1961), a private citizen sought damages against local officials for.

an unconstitutional scarch of a private residence. See also Zlrod v. Burns, U.S. , 96 S. Ct. 2673 (June 28, 1976) (discrimination

on account of political affiliation in public employment); 0’Connor

v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563 (1975) (terms and conditions of institu-

tional confinement).

Section 1985 and 1986 are used to challenge conspiracies, either

public or private, to deprive individuals of the equal protection of the

laws. Sco Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1971). The bill also

covers suits brought under Title IX of Public Law 92-318, the Lduca-

tion Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. 1681-1686. Title IX forbids spe-

cific kinds of discrimination on account of sex, blindness, or visual

impairment in certain federally assisted programs and activities re-

lating to education. IT? inally FLR. 15460 would also apply to actions

arising under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

2000d-2000d~6.10 ; : :

_ Title VI prohibits the discriminatory use of I'ederal funds, requir-

Ing recipients to administer such assistance without regard to race,

color, or national origin. Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) ; Hills

Vv. Gautrean, U.S. y 96 S. Ct. 1538 (April 20, 1976) ; Adams

v. llichardson, 480 I. 2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ; Bossier Parish School

Zoard v. Lemon, 370 TF. 24 847 (5th Cir. y cert. denied, 388 U.S. 911

(1967) ; Laufman v. Oakley Building and Loan Co., 408 TF. Supp. 489

(S.D. Ohio 1976).

D. DESCRIPTION OI II.R. 154060

As noted earlier, the United States Code presently contains over fifty

provisions for the awarding of attorney fees in particular cases. They may be placed generally into four categories: (1) mandatory awards only for a prevailing plaintiff; (2) mandatory awards for any provail- Ing party; (3) discretionary awards for a prevailing plaintifl's and (4) discretionary awards for any prevailing party. Ioxisting statutes allowing fees in certain civil rights cases generally fall into the fourth

category. Keeping with that pattern, H.R. 15460 tracks the languago

of the connsel feo provisions of Titles IT and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964," and Section 402 of the Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1975.12 The substantive section of ILR. 15460 reads as follows:

. In.any action or proceeding to enforce a provision of sec- -

tions 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, and 1981 of the Revised Statutes,

title IX of Public Law 92-318, or title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, the court, in its discretion, may allow tho pre-

vailing party, other than the United States, a reasonable

attorney’s fee as part of the costs.

10 7Pitle VI of the Clvil Rights Act of 1064 Is the only substantive title of that Act which does not contain a provision for aflorney fees. AZ TLS.CL 20000-3(h) (Tile 11) : 42 U.S.C 2000e-5 (k) (Title VII). 1242 U.8.C. 1073(e) (Sectlon 402).

6G

"Tha three key features of this attoriiey’s fee pitovision are: (1) that

awards may be'made to any “previiling party”; (2) that fees are to be

allowed in the discicetion of tlie courts hd (3) thdt awatds are to be

Uipeasaitable”. Ddeause other statutes follow this dpproach; the courts

ate familiar witlt these terms and in fact have reviewdd; examined;

and ihterpreted them at some length.

1. Prevailing party

Under ILE. 15460, cither a prevailing plaintiff or a prevailing

defendant is eligible to receive an award of fees. Congress has not

always been that generous. In about two-thirds of the existing statutes,

such as the Clayton Act and the Packers and Stockyards Act, only

yrevailing plaintiffs may recover their counsel fees.!* This bill folloivs

» more modest approach of other civil rights acts.

1t should be noted that when the Justice Department testified in

support of IL.IL. 9552, the piccedessor to TT.R. 15460, it suggested an

amendment to allow recovery only to prevailing plaintiffs. Assistant

Attorney General Tee thought, the phrase “prevailing party” inight /

have a “chilling effect” on civil Ls plaintiffs, discouraging them

from initiating law suits. The Cominittee was very concerned with

the potential impact such a phrase might have on persons seeking to

vindicato these important rights under Federal law. In light of existing

case law under similar provisions, however, the Committee concludec

that tho application of current standards to this bill will significantly

reditee the potentially adverse affect on the victims of unlawful conduct

who seek to assert their federal claims.

On two occasions, the Supreme Court has addressed the question of

the proper standard for allowing fees in civil rights cases. In Newman