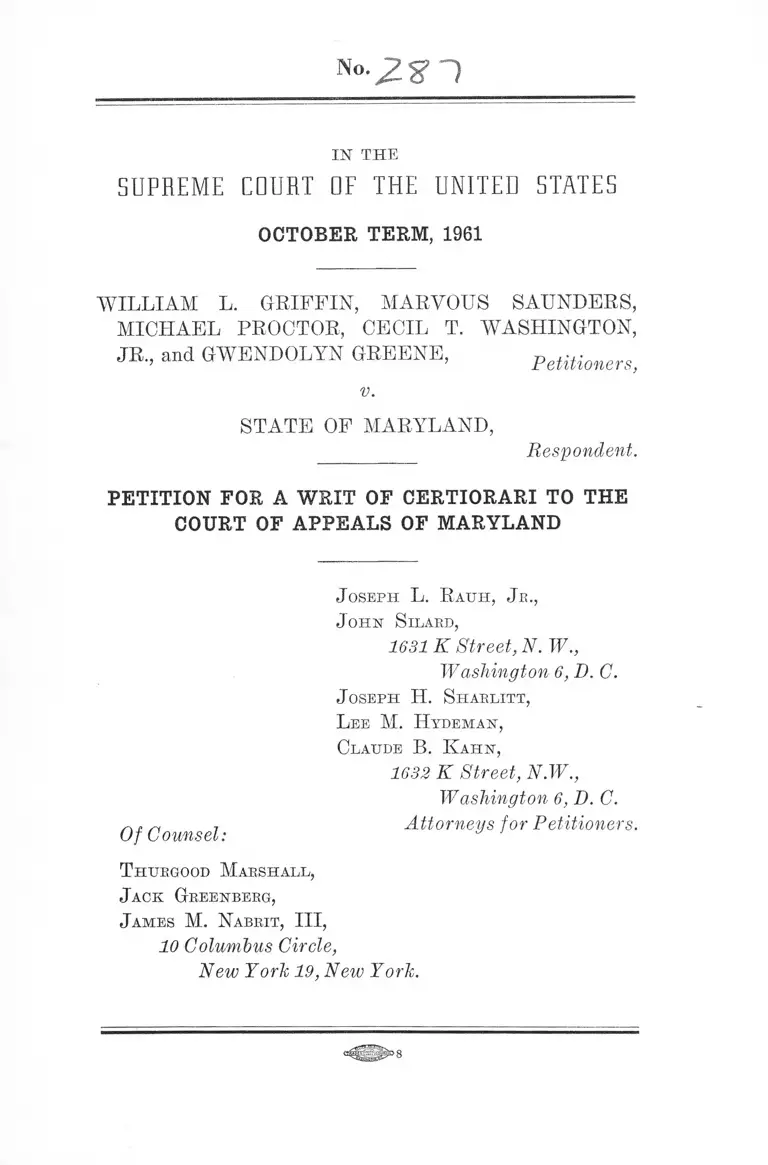

Griffin v. Maryland Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Maryland

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Griffin v. Maryland Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Maryland, 1961. 139a1bbf-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/443daacc-9be1-42de-bb08-c6134704dc43/griffin-v-maryland-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-court-of-appeals-of-maryland. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

S U P R E M E COURT OF T H E U N I T E D S TATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1961

WILLIAM L. GRIFFIN, MAEVOUS SAUNDERS,

MICHAEL PROCTOR, CECIL T. WASHINGTON,

JR., and GWENDOLYN GREENE, Petitioners,

v.

STATE OF MARYLAND,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND

Of Counsel:

J o se ph L . R atjh , J r .,

J o h n S ilard ,

1631 K Street, N. W.,

Washington 6, D. C.

J o se ph H . S h a r l it t ,

L e e M . H y d em a n ,

Claude B. K a h n ,

1632 K Street, A.IF.,

Washington 6, D. C.

Attorneys for Petitioners.

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

J ack G r een berg ,

J am es M . N a brit , III,

10 Columbus Circle,

New York 19, New York.

INDEX

Page

Opinions Below .......................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................ 2

Question Presented ................................................... 2

Statutes Involved ...................................................... 2

Statement ............................................... 2

Reasons for Granting the W rit.................................. 7

1. What degree of state participation in private

discrimination constitutes “ state action” for

bidden by the Fourteenth Amendment?............. 11

2. Is the Fourteenth Amendment transgressed in

the absence of a showing that it has been the

state’s purpose to enforce racial discrimination,

when the state’s authority has served to ad

minister and enforce such discrimination?......... 12

3. To what extent is the resolution of the consti

tutional issue affected by the consideration that

the “ property rights” being enforced are those

of business establishments catering to the gen

eral public rather than homeowners or others

seeking personal privacy?.................................. 13

4. What would be the impact of a ruling by this

Court that state power may not be invoked to

assist business establishments in their discrimi

nation against Negro customers?....................... 14

Conclusion ................................................................. 18

Appendix A : Oral Opinion of Trial Court................ 19

Opinion of Court of Appeals of Mary

land .................................................. 22

T able oe C ases

Avent v. North Carolina, No. 85, October Term,

1961 ........................................................................ 7,16

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249............................... 8

Boynton v. Virginia, No. 7, October Term, 1960, 364

U.S. 454 ............ ...................................................... 9,14

Briscoe v. Louisiana, No. 27, October Term, 1961.... 7

-7925-1

INDEXii

Page

Brown v. Board of Education, 344 U.S. 1................... 18

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715 ........................................................ ' ............. 9,11,13

Drews v. Maryland, No. 71, October Term, 1961....... 7

Fitzgerald v. Pan American World Airways, 229 F.2d

499 .......................................................................... 17

Garner v. Louisiana, No. 26, October Term, 1961.... 7

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339........................... 13

Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816................ 17

Hoston v. Louisiana, No. 28, October Term, 1961. ... 7

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501..............................8,13,14

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 81....................... 17

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373............................... 17

Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F.Supp. 545......... 17

Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 353 U.S. 230......... 9,15

Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 357 U.S. 570......... 15

Randolph v. Virginia, No. 248, October Term, 1961 . . 7

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 .................................. 7

Valle v. Stengel, 176 F.2d 697......... 11

M iscella n eo u s

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States, Section 1.........................................

Maryland Code (1957), Article 27, § 577...................

Montgomery County Code (1955), Sec. 2-91..............

N. Y. Times, Aug. 11, 1960, p. 14, col. 5 ....................

N. Y. Times, Oct. 18, 1960, p. 47, col. 5 .......................

Pollitt, Dime Store Demonstrations, 1960 Duke L.J.

315 ..........................................................................

Pollitt, The President’s Powers in Areas of Race

Relations, 39 N.C.L.Rev. 238..................................

Washington Post, March 15, 1961, p. 1, col. 2 .........

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3). ...................................................

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982.........................................

4

16

16

3

17

17

2

10

IN THE

S U P R E M E E DU R T DF T H E U N I T E D S TATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1961

No.

WILLIAM L. GRIFFIN, MARVOUS SAUNDERS,

MICHAEL PROCTOR, CECIL T, WASHINGTON,

JR., and GWENDOLYN GREENE, Petitioners,

v.

STATE OF MARYLAND,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND

To the Honorable Chief Justice of the United States and

the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Court of Appeals of Maryland entered

in this case on June 8, 1961.

Opinions Below

The opinions of the Circuit Court for Montgomery

County and of the Court of Appeals of Maryland have not

yet been reported. They are printed in Appendix A, infra,

pp. 19 to 29.

(1)

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals of Maryland was

entered on June 8, 1961. The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1257(3), petitioners having as

serted below and urging here denial of rights secured by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Question Presented

Whether, consistent with the Fourteenth Amendment,

the State of Maryland may utilize powers of police en

forcement, arrest, accusation, prosecution and conviction

to administer and enforce the racial discrimination of a

business advertising and catering to the general public.

Statutes Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, and Article

27, § 577 of the Maryland Code (1957) which provides:

“ Any person . . . who shall enter upon or cross over

the land, premises or private property of any person

. . . after having been duly notified by the owner or

his agent not to do so shall be deemed guilty of a mis

demeanor . . . provided [however] that nothing in this

section shall be construed to include within its provi

sions the entry or crossing over any land when such

entry or crossing is done under a bona fide claim of

right or ownership of said land, it being the intention

of this section only to prohibit any wanton trespass

upon the private land of others.”

Statement

The instant case presents unique and important aspects

of the legal issues which have arisen from the attempt of

Negro citizens to obtain equal treatment with that afforded

3

to whites in such public accommodations as food, transpor

tation, entertainment and recreation. The sequence of

events which gave rise to petitioners’ actions culminating

in their conviction by the State of Maryland, has its origin

in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960. On

that day four Negro students at the North Carolina A. & T.

College, who had grown increasingly impatient with pre

vailing practices under which Negro students could not

obtain food and refreshment served at local stores, de

termined to seek service at a local lunch counter in Greens

boro. This modest incident marked the beginning of wide

spread efforts, including those of present petitioners, to

open service to Negroes in places of public accommodation.

SeePollitt, Dime Store Demonstrations, 1960 Duke L. J. 315.

Glen Echo Amusement Park, the major amusement facil

ity serving the District of Columbia and its suburbs, is

located in Montgomery County, Maryland and has tradi

tionally been patronized by white customers (Tr. 93-95).1

On June 30, 1960, a number of persons gathered outside the

main entrance of the Park to urge that Negro patrons be

permitted to use the Park’s facilities and to seek service

for Negro patrons by patient, persistent and peaceable

efforts to obtain such service (Tr. 110-128). No tickets of

admission were required for entry into the Park (R.20)

and petitioners, young Negro students participating in the

Glen Echo protest, entered the Park through the open main

gates at about 8:15 p.m. (R. 15). Having been admitted

to the Park without difficulty, petitioners sought to enjoy

a merry-go-round ride and took seats on the carousel (R.

16) for which they had in their possession valid tickets of

admission (R. 20, Tr. 111).

1 “Tr.” references in this Brief indicate the pagination of the official

transcript of trial filed as a part of the record in this Court. “R.” refer

ences indicate pages of the printed record below, nine copies of which

have been filed with the Clerk of this Court.

4

Petitioners were hopeful that the Park would not refuse

them the service which it advertised and rendered to the

general public (see Tr. 114-116, 125-126). Their attempts

at service were not unreasonable, considering that no tickets

were required for admission to the Park itself (R. 20),

that none of the signs around the Park indicated any dis

crimination against Negro patrons (Tr. I l l) , and that in all

its press, radio, and television advertising in the District

of Columbia area the management invited “ the public gen

erally” without distinction of race or color (R. 25-26).

It soon developed, however, that petitioners were not go

ing to be able to ride the carousel on which they had taken

their places. Francis J. Collins, employed by the Glen

Echo management as a “ special policeman” under arrange

ment with the National Detective Agency (R. 14, 18) and

deputized as a Special Deputy Sheriff of Montgomery

County on the request of the Park management (R. 18),

promptly approached petitioners (R. 16).2 He was dressed

in the uniform of the National Detective Agency and was

wearing the Special Deputy Sheriff’s badge representing

his state authority (R. 17-18). On the orders of and on

behalf of the management (Tr. 104), Deputy Sheriff Collins

directed petitioners to leave the Park within five minutes

because it was “ the policy of the park not to have colored

people on the rides, or in the park” (R. 16). Petitioners

declined to obey Collins’ direction, remaining on the carrou

sel for which they tendered tickets of admission (R. 17,

20).3 Having unsuccessfully directed petitioners to leave

2 Collins was head of the private police force at the Park among whom

at least two of the employees were deputized as Special Deputy Sheriffs

(Tr. 105), pursuant to Montgomery County Code (1955) Sec. 2-91.

3 Friends of the petitioners had purchased these tickets and had given

them to petitioners (Tr. I l l , 118-119). There is no suggestion that the

management placed any restriction upon the transfer of tickets to friends

and relatives; indeed, it was conceded by an agent of the Park that trans

fers frequently occurred in his presence (R. 21). No offer to refund the

purchase price was made to petitioners (R. 20).

5

the premises, under color of his authority as a Special

Deputy Sheriff of Montgomery County Collins now ar

rested petitioners (It. 17, 18) for wantonly trespassing- in

violation of a Maryland statute (Code, Art. 27, Sec. 577)

making it illegal to “ enter or cross over” the property

of another “ after having been duly notified by the owner

or his agent not to do so. ’ ’ There was no suggestion that

petitioners “ were disorderly in any manner” (see p. 23,

infra). At the subsequent trial, Deputy Sheriff Collins

affirmed that he arrested petitioners “because they were

negroes,” and explained that “ I arrested them on orders

of Mr. Woronoff [Park Manager], due to the fact that

the policy of the park was that they catered just to white

people . . . ” (R, 19).

At the Montgomery County Police precinct house, where

petitioners were taken after their arrest (R. 17), Collins

preferred sworn charges for trespass ag'ainst the peti

tioners (R. 11, Tr. 41), leading to their trial under the

Maryland wanton trespass statute in the Circuit Court

for Montgomery County on Sept, 12, 1960. At the trial,

Park co-owner Abram Baker candidly described his use

of Deputy Sheriff Collins to enforce racial discrimination:

‘ ‘ Q. Would you tell the Court what you told Lieutenant

Collins relating to the racial policies of the Glen

Echo Park? A. We didn’t allow negroes and in

his discretion, if anything happened, in any way,

he was supposed to arrest them, if they went on

our property.

Q. Did you specify to him what he was supposed

to arrest them for? A. For trespassing.

Q. You used that word to him? A. Yes; that is

right.

Q. And you used the word ‘discretion’—what did

you mean by that? A. To give them a chance

to walk off; if they w-anted to.

6

Q. Did you instruct Lieutenant Collins to arrest all

negroes who came on the property, if they did

not leave? A. Yes.

Q. That was your instructions? A. Yes.

Q. And did you instruct him to arrest them because

they were negroes? A. Yes” (.R. 24-25).

Petitioners’ constitutional objections to the State’s par

ticipation in and support of racial discrimination, were

repeatedly rejected by the trial court (R. 13-14, 17, 27-30,

32, 33-36). Petitioners were convicted and fined for wanton

trespass under the Maryland statute (R. 1-5, p. 19, infra).

The Maryland Court of Appeals affirmed the convictions,

holding the petitioners ’ refusal to leave the premises upon

instructions of management agent Collins, to constitute

unlawfully “ entering or crossing over” the owners’ prop

erty, within the meaning of Art. 27, Sec. 577. The Court

dismissed the objections under the Fourteenth Amendment

and under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982 to State support of

racial discrimination by a public commercial enterprise,

finding the case to be “ one step removed from State en

forcement of a policy of segregation” (infra, pp. 27-28).

The question thus presented is whether the ruling below

can stand, consistent with the equal protection and due

process guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment, in cir

cumstances where the State’s direction to leave, the arrest,

the accusation, the prosecution and the criminal conviction

supported and enforced discrimination against peaceable

Negro patrons by a commercial enterprise advertising and

catering to the general public.

7

Reasons for Granting the Writ

This Case Presents for Review a Compelling Record of

State Participation In and Support to “Private” Racial

Discrimination and Provides Important Illumination on a

Constitutional Issue Presently Pending before the Court

At its present term, this Court will review the use of a

Louisiana breach of the peace statute in a manner which

provided the support of the State to the racially discrimi

natory practices of businesses catering to the public. See

Nos. 26, 27 and 28, Garner, Briscoe and Boston v. Louisiana.

There are also pending applications for review from Vir

ginia, North Carolina and Maryland involving convictions

for “ trespass” and “ disorderly conduct” of Negroes

seeking food, recreation and similar public services at

business establishments discriminating against Negro cus

tomers. See No. 248, Randolph v. Virginia; No. 71, Drews

v. Maryland; No. 85, Avent v. North Carolina, This Court’s

review is especially warranted in the instant case, for it

presents a unique degree of State involvement in and sup

port to racial discrimination against orderly Negro patrons

by the largest amusement facility catering to the public

in the District of Columbia area. In addition, concurrent

review of this proceeding will provide important illumina

tion upon fundamental issues presented in the Louisiana

cases and the pending applications for review from Vir

ginia, North Carolina and Maryland.

The premise of the challenge against the criminal pro

ceedings involved in the pending cases is that such mani

festations of state power in support of the racially dis

criminatory practices of enterprises serving the public,

constitute “ state action” forbidden by the Fourteenth

Amendment. What the states have done in all these

cases falls well within the area of impermissible state

action set forth in this Court’s rulings in Shelley v.

8

Kraemer, 334 U.8. 1, Barroivs v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249,

and Mar,sh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501. Indeed, in the instant

case there is an even closer interplay between private

discrimination and its enforcement by various powers of

the State than existed in Shelley, Barrows and Marsh,

For here, not only the prosecutory and judicial power of

the State have been employed to enforce discrimination,

but the State’s police authority was handed to the Glen

Echo management on a formalized basis for the con

tinuing administration and enforcement of its discrimi

natory policy. Deputy Sheriff Collins, not upon the re

quest but upon the orders of the private management

which employed him, and wearing the badge of his public

office, informed and instructed petitioners that because

they were Negroes they would have to leave the premises.

It was Collins and his associates who were thus adminis

tering the Park’s policy of racial discrimination on a day

to day basis and Collins’ direction to the petitioners to

leave the premises consummated the unconstitutional in

volvement of the State in the “ private” practice of dis

crimination.4 Then, to add injury to insult, still following

the orders of his employers and in his capacity as an

officer of the State, Collins arrested petitioners and filed

a warrant under oath against them, bringing into play the

prosecutorial machinery of the State. The significance

of the case at bar is thus found in the fact, directly con

trary to the ruling below that State action here was

“ one step removed from State enforcement of a policy

of segregation,” that there was absolutely no severance

at any time between public and private authority at Glen

Echo Park. What this case adds to those -presently before

4 Indeed, Deputy Sheriff Collins “made the crime” of which petitioners

were convicted. Collins’ direction to leave was a necessary prerequisite

of the trespass charge, for petitioners could not have been so charged

(and were admittedly lawfully on the premises) until Collins, a state

officer, directed them to leave.

9

the Court is that the P art’s policy of racial discrimination

was at all times being administered and enforced by the

State through Deputy Sheriff Collins and his colleagues.

Here the State of Maryland was not merely enforcing

the Company’s racial discrimination through prosecution

in the courts, but was itself administering that discrimina

tion on the premises of the largest public amusement fa

cility in the District of Columbia area.. Cf. Pennsylvania

v. Board of Trusts, 353 U.S. 230.

As this Court recently phrased the presently applicable

principle in Burton v. Wilmington Parting Authority,

365 U.S. 715, 722, the equal protection clause is invoked

when “to some significant, extent the state,in any of its mani

festations has been found to become involved” in private

conduct abridging individual rights. The applicability of

this rule when the state lends its support to discrimination,

through its police powers of direction to leave premises,

arrest, accusation, prosecution and conviction, certainly

presents an important question for review; this Court

characterized the analogous issue presented in Shelley v.

Kraemer as involving “ basic constitutional issues of ob

vious importance” (334 U. S. at p. 4).

Significantly, the United States as amicus curiae in

Boynton v. Virginia (No. 7, October Term, 1960) recently

urged reversal of a Virginia trespass conviction upon the

ground being urged in the pending case, that the Four

teenth Amendment precludes a state’s prosecutorial en

forcement of racial discrimination by a business catering

to the public,5 In the Government’s Brief before this

5 This Court decided the Boynton case (364 U.S. 454) on the independ

ent interstate commerce point also urged by the Government. But, for

present purposes, it should be emphasized that in the Government’s view,

invocation of Virginia’s criminal trespass authority to support the racially

discriminatory policy of the private restaurant there involved, constituted

a complete and independent ground for reversal under the Fourteenth

Amendment.

10

Court (at p. 17), the Solicitor General emphasized that

‘ ‘ The application of a general, nondiscriminatory, and oth

erwise valid law to effectuate a racially discriminatory

policy of a private agency, and the enforcement of such

a discriminatory policy by state governmental organs, has

been held repeatedly to be a denial by state action of

rights secured by the Fourteenth Amendment.” Pertinent

judicial rulings, the Brief for the United States suggested,

demonstrate that “ where the state enforces or supports

racial discrimination in a place open for the use of the

general public . . . it infringes Fourteenth Amendment

rights notwithstanding the private origin of the discrim

inatory conduct” (at p. 20). The Solicitor General con

cluded that the conviction for “ trespass” of a Negro seek

ing service at a Richmond, Virginia, restaurant consti

tuted unlawful state support to private discrimination,

and that

“ When a state abets or sanctions discrimination

against a colored citizen who seeks to patronize a

business establishment open to the general public, the

colored citizen is thereby denied the right ‘to make

and enforce contracts’ and ‘to purchase personal prop

erty’ guaranteed by 42 U.S.C. 1981 and 1982 against

deprivation on racial grounds” (at p. 28).

Clearly, the pending state prosecutions for “ trespass” ,

“ breach of peace” and “ disorderly conduct”, enforcing

the racial practices of businesses catering to the general

public, offend the mandate of the Fourteenth Amendment

under the authoritative rulings of this Court and present

an important issue for review.6 Yet, the manifest appli

cability of this Court’s rulings against state support to

6 The State action involved in the instant case not only offends the

Constitution but equally transgresses 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982. These

statutory prohibitions also provide significant and contemporary illumina

tion on the intended scope of the Fourteenth Amendment itself.

11

private discrimination does not obscure the fact that a

number of unresolved questions inhere in the adjudica

tion of the pending constitutional issue. We recognize

that the Court will desire carefully to examine certain re

curring questions involved in state support to private

practices of racial discrimination, and we respectfully sug

gest that the instant case particularly lends itself to the

examination of four of these questions, to which we now

turn : 7

1. What degree of state participation in private dis

crimination constitutes “state action” forbidden by the

Fourteenth Amendment?

In its recent Wilmington Parking Authority decision,

365 U. 'S. 715, 722, this Court stated that the Fourteenth

Amendment is violated when state support to private dis

crimination has been given “to some significant extent.”

This Court will certainly be called upon in the pending

cases to determine whether a “ significant extent” of state

support to discrimination inheres in the arrest, accusa

tion, prosecution and conviction (taken separately or to

gether), of Negro customers peaceably seeking to obtain

services provided by business establishments catering to

the general public.

We submit that state prosecution and conviction which

enforces the racial discrimination of a business proprietor

constitutes significant state aid to discrimination in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment.8 But in the instant

7 A fifth question for this Court’s consideration may be whether in this

case the highest court of Maryland has construed the Maryland enact

ment “as authorizing discriminatory classifications based exclusively on

color.” See concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Stewart in Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715. While the Maryland stat

ute is neutral on its face, as construed below it requires the conviction

of one who, “after having been duly notified by the owner or agent not

to do so” because he is a Negro, enters or crosses over his property.

8 This, indeed, is the holding of the Third Circuit, one directly con

trary to the ruling below, under similar factual circumstances. See

Valle v. Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697.

12

case we have far more state action than prosecution and

conviction. Here the Deputy Sheriffs were the omnipres

ent administrators and enforcers of the owners’ racial

discrimination; here on orders of the private management

the officer of the State, wearing* his badge as a Deputy

Sheriff, demanded that petitioners leave the premises be

cause they were Negroes, thereafter arrested them “ be

cause they were Negroes” , and filed sworn complaints

which initiated the State prosecutions. The entire sequence

of events demonstrates Maryland’s inextricable and con

tinuous involvement in the administration and enforcement

of the racially discriminatory policy of Glen Echo Park.

2. Is the Fourteenth Amendment transgressed in the ab

sence of a showing that it has been the state’s purpose to

enforce racial discrimination, ivhen the state’s authority

has served to administer and enforce such discrimination?

The court below ruled that the arrest and conviction of

petitioners “ as a result of the enforcement by the operator

of the park of its lawful policy of segregation”, could not

“ fairly be said to be” the action of the State. In so do

ing, the court below apparently accepted a major conten

tion of the State, that prosecution and conviction is es

sentially a neutral manifestation of Maryland’s general

interest in enforcing “ property rights,” devoid of any

racial connotation. This contention does not question that

the manifestation of the State’s power has the effect of

supporting the practice of racial discrimination; rather,

it suggests that, unless the State’s purpose is to give sup

port. to discrimination, the Fourteenth Amendment is not

violated.

But discriminatory “ motivation” by the state can hardly

be the sine qua non of the Fourteenth Amendment’s ap

plicability when as a matter of fact the exercise of the

13

state’s power supports and abets the practice of racial

discrimination. Nowhere in the restrictive covenant de

cisions or in the recent formulation in Wilmington Park

ing Authority is a motive requirement suggested; recently,

in Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, this Court re

jected a similarly confining motivational interpretation

of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equality guarantee. In

deed, the very contention that the State is “ neutrally”

enforcing property rights rather than intending to assist

discrimination, was rejected in Shelley v. Kraemer, this

Court emphasizing that “ the power of the State to create

and enforce property interests must be exercised within

the boundaries defined by the Fourteenth Amendment”

(p. 22).

In any event, in the instant case it is clear that not only

the effect but the purpose of the State’s action has been

to give support to d en Echo’s racial policy. The State

surrendered its police authority to the use and control

of a private corporation for its enforcement of racial dis

crimination. Armed with police authority, Deputy Sheriff

Collins obeyed the orders of his employers in seeking to

expel and thereafter in arresting and charging petitioners

for trespass. Collins, acting under color of law, had as

his sole purpose the administration of discrimination

against Negroes. Having put its authority under the

orders and control of the Park for its enforcement of racial

discrimination, the State cannot now be heard to say that

the owners ’ purpose was not its purpose as well.

3. To ivhat extent is the resolution of the constitutional

issue affected by the consideration that the “property

rights” being enforced are those of business establishments

catering to the general public rather than homeowners or

others seeking personal privacy f

In Marsh v. Alabama, 326 TT.S. 501, this Court ruled

that the exertion of state criminal authority on behalf of

14

a proprietor’s restriction on the liberties of a member of

the general public on his premises was precluded by the

Fourteenth Amendment. The Court pointed out (at 505-

506) : “ The State urges in effect that the corporation’s right

to control the inhabitants of 'Chickasaw is coextensive with

the right of a homeowner to regulate the conduct of his

guests. We cannot accept that contention. Ownership does

not always mean absolute dominion. The more an owner,

for Ms advantage, opens up Ms property for use by the

public in general, the more do Ms rights become circum

scribed by the statutory and constitutional rights of those

who use it.” (Emphasis supplied). The Marsh case thus

highlights the significance attaching to the fact that in the

pending case racial discrimination is being enforced by the

State on behalf of a public establishment rather than on be

half of individuals, homeowners or associations seeking pro

tection of rights of personal property or privacy. As the

Government’s brief affirmed with respect to a similar tres

pass prosecution in last term’s Boynton case (at p. 20, 22),

the Fourteenth Amendment is infringed where the state

“enforces or supports racial discrimination in a place open

for the use of the general public,” for the issue

“ is not whether the right, for example, of a home-

owner to choose his guests should prevail over peti

tioner’s constitutional right to be free from the state

enforcement of a policy of racial discrimination, but

rather whether the interest of a proprietor who has

opened up his business property for use by the gen

eral public—in particular, by passengers travelling-

in interstate commerce on a federally-regulated car

rier—should so prevail.”

Glen Echo Amusement Park is a licensed business enter

prise owned and operated by corporations chartered by

the State of Maryland. It caters to the general public as

15

the major amusement park in the District of Columbia area

and none of its numerous advertisements through various

means of public communication reflected any discrimina

tion against Negro members of the public. No tickets of

admission were required for entrance to the Park through

its open gates, and no signs around the Park proclaimed

any restriction upon the custom of Negro patrons. These

factors underline the critical consideration in the pending

case that the State’s power is being invoked to enforce

not personal privacy, but rather to assist a business cater

ing to the general public in its refusal of service to Negro

members of the public. We suggest that in the disposi

tion of the pending issue, a vital constitutional difference

inheres in the distinction between state enforcement of

racial discrimination at places of public accommodation,

and state protection (where there has been no dedication

of the property to the general public) of individual, resi

dential or associational privacy.9

4. What would be the impact of a ruling by this Court

that state power may not be invoked to assist business

establishments in their discrimination against Negro cus

tomers?

In its public school desegregation decisions this Court

evidenced its concern with the impact of a constitutional

ruling requiring widespread changes in local customs and

9 It cannot be too strongly emphasized that there is involved here, not

the right of an individual to determine the people he will receive and

entertain in his home or private estate, or to select the beneficiaries of

his private benevolence. Compare Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 357

U.S. 570, with Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 353 U.S. 2'30. The right

of the individual to the aid of the state in enforcing his own discrimina

tory ideas outside his strictly private or personal domain is another mat

ter. And it is here that the Fourteenth Amendment forbids the state to

intervene to support racially discriminatory practices. Private corpora

tions cannot invite the general public to patronize their businesses and then

call upon the state to exclude members of the public solely because of

their race.

16

practices. In the pending cases this Court will doubtless

consider the suggestion that, if denied state enforcement

of racial practices, proprietors will widely resort to forc

ible self-help.10 On this score, we submit that the public

record demonstrates the unlikelihood of any substantial

discord or danger attendant upon the removal of state

support to the discriminatory practices of enterprises

serving the public. It is not the habit of establishments

seeking the trade of the public to engage in the unpleasant

work of self-help ousters of racial minorities; rather they

seek the police to make the ousters for them. The recent

abandonment of racial practices by business communities

in many Southern localities demonstrates that these prac

tices are not the product of public attitudes or business

necessity but only the vestigial remains of former condi

tions, succored by the willingness of public authorities to

enforce the written and unwritten law of segregation.

Prior to February, 1960, lunch counters throughout the

South denied normal service to Negroes. Six months later,

lunch counters in 69 cities had ended their discriminatory

practices (N. Y. Times, Aug. 11, 1960, p. 14, col. 5); by

October the number of desegregated municipalities had

mounted to more than one hundred (N. Y. Times, Oct.

18, 1960, p. 47, col. 5) and has since continued to increase

without apparent incident.

There is more evidence that removal of legal sanctions

supporting segregation in public places effectively obviates

10 As the Supreme Court of .North Carolina put the suggestion in Avent

v. North Carolina (petition pending, No. 85 this Term), if an owner

cannot bar Negroes “by judicial process as here, because it is State action,

then he has no other alternative but to eject them with a gentle hand if

he can, with a strong hand if he must.” This contention is not, of course,

legally relevant to the constitutional validity of State action in support

of discrimination. What we suggest in the text here is that the conten

tion is not only legally irrelevant but factually tenuous. Indeed, in Dur

ham, North Carolina, where Avent arose, the dime stores have since quietly

abandoned discrimination.

17

further conflict or difficulty. When state segregation laws

were struck down, public libraries in Danville, Virginia

and Greenville, South Carolina were closed to avoid de

segregation; they reopened a short time later, first on a

“ stand up only” basis and then on a normal basis, all

without incident. Then, too, when public swimming pools

were judicially ordered to desegregate, San Antonio,

Corpus Christ!, Austin, and others integrated without

disorder or difficulty. See Poliitt, The President’s Powers

in Areas of Race Relations, 39 N.C.L. Rev. 238, 275. Sim

ilarly, Miami Beach, Houston, Dallas and others inte

grated their public golf courses without incident. Ibid.

Again, while the in terrorem argument against desegre

gation was suggested in cases involving pullman cars

(Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 81), dining cars (Hen

derson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816), buses (Morgan v.

Virginia, 328 U.S. 373), and air travel and terminal service

(Fitzgerald v. Pan American World Airways, 229 P. 2d

499; Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545),

experience has disproved the predictions of violence.

In the instant ease no possible difficulty could arise from

this Court’s invalidation of State support for segregation

at Glen Echo Amusement Park, the Park having aban

doned its prior racial practices in March of this year (see

Washington Post, March 15, 1961, p. 1, col. 2). Unques

tionably, an element in the management’s abandonment of

discrimination was petitioners’ challenge to the State’s

enforcement of that discrimination. The national evidence

equally demonstrates that state enforcement of segregation

constitutes the last remaining cornerstone for racial prac

tices at places of public service and accommodation.

18

Conclusion

The instant case, involving prosecutions for trespass,

presents in sharp focus constitutional questions related to

those the Court has agreed to review in the Louisiana

cases, arising from prosecutions for breach of the peace.

In a like setting, this Court has indicated the desirability

of its concurrent review over cases presenting related

aspects of a constitutional question of national importance.

Brotvn v. Board of Education, 344 U.S. 1, 3. It is sub

mitted that the grant of certiorari in this case is justified

both by the compelling record of Maryland’s administra

tion of and support to the “ private” practice of racial

discrimination, and by the illumination this record fur

nishes upon material aspects of a pending constitutional

issue of nationwide importance.

Respectfully submitted,

J o se ph L . R a u h , J r .,

J o h n S ilard ,

1631 K Street, N. W.,

Washington 6, D. C.

J o se ph H . S h a r l it t ,

L ee M. H y d em a n ,

Claude B . K a h n ,

1632 K Street, N.W.,

Washington 6, D. C.

„ , _ 7 Attorneys for Petitioners.Of Counsel:

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

J ack G reen b er g ,

J am es M. N abrit , I I I ,

10 Columbus Circle,

New York 19, New York.

19

APPENDIX A

Oral Opinion of Trial Court

It is very unfortunate that a case of this nature comes

before the criminal court of our State and County. The

nature of the case, basically, is very simple. The charge

is simple trespass. Simple trespass is defined under Sec

tion 577 of Article 27 of the Annotated Laws of Maryland,

which states that “ any person or persons who shall enter

upon or cross over the land, premises, or private property

of any person or persons in this State, after having been

duly notified by the owner or his agent not to do so shall

be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor.” Trespass has been

defined as an unlawful act, committed without violence,

actual or implied, causing injury to the person, property

or relative rights of another. This statute also has a

provision in it which says that it is the intention of the

Legislature as follows: “ It is the intention of this sec

tion only to prohibit any wanton trespass upon the pri

vate land of others.” Wanton has been defined in our

legal dictionaries as reckless, heedless, malicious; char

acterized by extreme recklessness, foolhardiness and reck

less disregard for the rights or safety of others, or of

other consequences.

There have been many trespass cases in Maryland. As a

matter of fact, there is one case now pending before the

Court of Appeals of Maryland where the racial question has

been injected into a disorderly conduct case, and that is

the case of “ State of Maryland versus Dale H. Drews” ,

decided some few months ago. In that case, Judge

Menchine filed a lengthy written opinion, in which he

touched upon the rights of a negro to go on private

property, whether it is a semi-public or actually a public

business, and is that case Judge Menchine said as follows:

“ The rights of an owner of property arbitrarily to re

strict its use to invitees of his selection is the established

law of Maryland.” This Court agrees with that opinion,

and unless that case is reversed by the Court of Appeals

of Maryland, at its session this Fall, that will continue to

be the law of Maryland.

20

That statement by Judge Menchine is based upon author

ities of this State, and not too far back, in the case of

Greenfeld versus the Maryland Jockey Club, 190 Md. 96,

in which the Court of Appeals of this State said: “ The

rule that, except in cases of common carriers, inn-keepers

and similar public callings, one may choose his customers,

is not archaic. ’ ’

If the Court of Appeals changes its opinion in the 190

Maryland case, then we will have new law in this State

on the question of the right of a negro to go on private

property after he is told not to do so, or after being on it,

he is told to get off.

In this Country, as well as many, many counties in the

United States, we have accepted the decision of integration

that has been promulgated by the Supreme Court in the

school cases, and without and provocation or disputes of any

consequence. There is no reason for this Court to change

that method of accepting integration, but when you are

confronted with a question of whether or not that policy

can be extended to private property, we are reaching

into the fundamental principles of the foundation of this

country.

The Constitution of the United States has many provi

sions, and one of its most important provisions is that of

due process of law. Due process of law applies to the right

of ownership of property—that you cannot take that prop

erty, or you cannot do anything to interfere with that man’s

use of his property, without due process of law.

Now, clearly, in this case, which is really a simple case;

it is a simple case of a group of negroes, forty in all,

getting together in the City of Washington, and coming

into Maryland, with the express intent, by the testimony of

one of the defense witnesses, that they were going to make

a private corporation change its policy of segregation. In

other words, they were going to take the law in their own

hands. Why they didn’t file a civil suit and test out the

right of the Glen Echo Park Amusement Company to fol

low that policy is very difficult for this Court to under

stand, yet they chose to expose themselves to possible harm;

to possible riots and to a breach of the peace. To be ex

21

posed to the possibility of a riot in a place of business,

merely because these defendants want to impress upon that

business their right to use it, regardless of the policy of

the corporation, should not he tolerated by the Courts.

Unless the law of this State is changed, by the Court of

Appeals of Maryland, this Court wili follow the law that

has already been adopted by it, that a man’s property is

his castle, whether it be offered to the public generally, or

only to those he desires to serve.

There have been times in the past, not too many years

back, when an incident of this kind would have caused a

great deal of trouble. It could have caused race riots, and

could have caused bloodshed, but now the Supreme Court,

in the school case in 1954, has decided that public schools

must be integrated, and the people of this County have ac

cepted that decision. They have not quibbled about i t ; They

have gone along with it without incident. We are one of

the leading counties in the United States in accepting that

decision. If the Court of Appeals of Maryland decides

that a negro has the same right to use private property as

was decided in the school cases, as to State or Government

property, or if the Supreme Court of the United States so

decides, you will find that the places of business in this

County will accept that decision, in the same manner, and

in the same way that public authorities and the people

of the County did in the School Board decision, but there

is nothing before this Court at this time except a simple

case of criminal trespass. The evidence shows the defend

ants have trespassed upon this Corporation’s property,

not by being told not to come on it, but after being on the

property they were told to get off.

Now it would be a ridiculous thing for this Court to

say that when an individual comes on private property, and

after being on it, either sitting on it or standing on it, and

the owner comes up and says, “ Get off my property”, and

then the party says “ You didn’t tell me to get off the prop

erty before I came on it, and, therefore, you cannot tell

me to get off now” he is not guilty of trespass because he

was not told to stay off of the property. It is a wanton

trespass when he refuses to get off the property, after be

ing told to get off.

22

One of the definitions of wanton is “ foolhardy” and this

surely was a foolhardy expedition; there is no question

about that. When forty people get together and come

out there, as they did, serious trouble could start. It is a

simple case of trespass. It is not a breach of the peace,

or a case of rioting, but it could very easily have been,

and we can thank the Lord that nothing did take place

of such a serious nature.

It is not up to the Court to tell the Glen Echo Amuse

ment Company what policies they should follow. If they

violate the law, and are found guilty, this Court will sen

tence them.

It is most unfortunate that this matter comes before the

Court in a criminal proceeding. It should have been

brought in an orderly fashion, like the School Board case

was brought, to find out whether or not, civilly, the Glen

Echo Park Amusement Company would follow a policy of

segregation, and then you will get a decision based on the

rights of the property owner, as well as the rights of these

defendants. So, the Court is very sorry that this case has

been brought here in our courts.

It is my opinion that the law of trespass has been vio

lated, and the Court finds all five defendants guilty as

charged.

Opinion of Court of Appeals of Maryland

This is a consolidated appeal from ten judgments and

sentences to pay fines of one hundred dollars each, entered

by the Circuit Court for Montgomery County after sepa

rate trials, each involving five defendants, on warrants

issued for wanton trespass upon private property in viola

tion of Code (1957), Art. 27, § 577.

The first group of defendants, William L. Griffin, Mar-

vous Saunders, Michael Proctor, Cecil T. Washington, Jr.,

and Gwendolyn Greene (hereinafter called “ the Griffin

appellants” or “ the Griffins” ), all of whom are Negroes,

were arrested and charged with criminal trespass on

June 30, 1960, on property owned by Eekab, Inc., and

operated by Kebar, Inc., as the Glen Echo Amusement

Park (Glen Echo or park). The second group of defend

ants, Cornelia A. Greene, Helene D. Wilson, Martin A.

Schain, Ronyl J. Stewart and Janet A. Lewis (hereinafter

called “ the Greene appellants” or “ the Greenes” ), two

of whom are Caucasians, were arrested on July 2, 1960,

also in Glen Echo, and were also charged with criminal

trespass.

The Griffins were a part of a group of thirty-five to

forty young colored students who gathered at the entrance

to Glen Echo to protest “ the segregation policy that we

thought might exist out there.” The students were

equipped with signs indicating their disapproval of the

admission policy of the park operator, and a picket line

was formed to further implement the protest. After about

an hour of picketing, the five Griffins left the larger group,

entered the park and crossed over it to the carrousel.

These appellants had tickets previously purchased for

them by a white person) which the park attendant refused

to honor. At the time of this incident, Rekab and Kebar

had a “ protection” contract with the National Detective

Agency (agency), one of whose employees, Lt. Francis J.

Collins (park officer), who is also a special deputy sheriff

for Montgomery County, told the Griffins that they were

not welcome in the park and asked them to leave. They

refused, and after an interval during which the park

officer conferred with Leonard Woronoff (park manager),

the appellants were advised by the park officer that they

Were under arrest. They were taken to an office on the

park grounds and then to Bethesda, where the trespass

warrants were sworn out. At the time the arrests were

made, the park officer had on the uniform of the agency,

and he testified that he arrested the appellants under the

established policy of Kebar of not allowing Negroes in

the park. There was no testimony to indicate that any

of the Griffins were disorderly in any manner, and it seems

to be conceded that the park officer gave them ample time

to heed the warning to leave the park had they wanted

to do so.

The Greene appellants entered the park three days after

the first incident and crossed over it and into a restaurant

operated by the B & B Industrial Catering Service, Inc.,

under an agreement between Kebar and B & B, These

24

appellants asked for service at the counter, were refused,

and were advised by the park officer that they were not

welcome and were ordered to leave. They refused to

comply by turning their backs on him and he placed them

under arrest for trespassing. Abram Baker (president

of both Rekab and Kebar) testified that it was the policy

of the park owner and operator to exclude Negroes and

that the park officer had been instructed to ask Negro

customers to leave, and that if they did not, the officer

had orders to arrest them. There was no evidence to

show that the operator of the restaurant had told the

Greenes they were not welcome or to leave; nor was there

any evidence that the park officer was an agent of the

restaurant operator. And while a prior formal agreement

covering the 1957 and 1958 seasons had provided that the

restaurant operator was subject to and should comply

with the rules and regulations concerning the persons to

be admitted to the park and that Kebar had reserved the

right to enforce them, the letter confirming the agreement

for the 1959 and 1960 seasons fixed the rentals for that

period and alluded to other matters, but made no reference

Whatsoever, either directly or indirectly, to the prior formal

agreement—though there was testimony, admitted over

objection, to the effect that the letter was intended as a

renewal of the prior lease—and was silent as to a reser

vation by Kebar of the rigid to police the restaurant

premises during the 1959 and 1960 seasons.

On this set of facts, both groups of appellants make

the same contentions on this appeal: (i) that the require

ments for conviction under Art. 27, § 577, were not met;

and (ii) that the arrest and conviction of the appellants

constituted an exercise of the power of the State of Mary

land in enforcing a policy of racial segregation in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

1 The document was called an “agreement” ; the operator of the restau

rant was referred to therein as a “concessionaire” and was described in the

agreement as a “licensee” and not a “lessee” ; yet the agreement called for

the payment of rent (payable bi-annually) as well as for a portion of the

gross receipts and a part of the county licensing fees and certain other

items of expense.

25

Trespass to private property is not a crime at common

law unless it is accompanied by, or tends to create, a

breach of the peace. See Krauss v. State, 216 Md. 369,

140 A. 2d 653 (1958), and the authorities therein cited.

And it was not until the enactment of § 21A of Art. 27

(as a part of the Code of 1888) by Chapter 66 of the

Acts of 1900 that a “ wilful trespass” (see House Journal

for 1900, p. 322) upon private property was made a mis

demeanor. That statute, which has remained unchanged

in phraseology since it was originally enacted, is now

§ 577 of Art. 27 (in the Code of 1957), entitled “ wanton

trespass upon private land,” and reads in pertinent part:

“ Any person * * # who shall enter upon or cross

over the land, premises or private property of any

person * * * after having been duly notified by the

owner or his agent not to do so shall be deemed guilty

of a misdemeanor * * *; provided [however] that

nothing in this section shall be construed to include

* * * the entry or crossing* over any land when such

entry or crossing* is done under a bona fide claim of

right or ownership * * *, it being the intention of this

section only to prohibit any wanton trespass upon the

private land of others.”

The Case Against the Griffin Appellants

(i)

The claim that the requirements for conviction were not

met is threefold: (a) that due notice not to enter upon

or cross over the land in question was not given to the

appellants by the owner or its agent; (b) that the action

of the appellants in doing what they did was not wanton

within the meaning of the statute; and (c) that what the

appellants did was done under a bona fide claim of right.

There was due notice so far as the Griffins were con

cerned. Since there was evidence that these appellants had

gathered at the entrance of Glen Echo to protest the segre

gation policy they thought existed there, it would not be un

reasonable to infer that they had received actual notice not

to trespass on the park premises even though it had not

been given by the operator of the park or its agent. But,

26

even if we assume that the Griffins had not previously had

the notice contemplated by the statute which was required

to make their entry and crossing unlawful, the record is

clear that after they had seated themselves on the car

rousel, these appellants were not only told they were un

welcome, but were then and there clearly notified by the

agnt of the operator of the park to leave and deliberately

chose to stay. That notice was due notice to these ap

pellants to depart from the park premises forthwith, and

their refusal to do so when requested constituted an un

lawful trespass under the statute. Having been duly noti

fied to leave, these appellants had no right to remain on

the premises and their refusal to withdraw was a clear

violation of the statute under the circumstances even though

the original entry and crossing over the premises had not

been unlawful. State v. Fox, 118 S.E.2d 58 (N.C. 1961).

Gf. Commonwealth v. Richardson, 48 N.E.2d 678 (Mass.

1943). Words such as “ enter upon” or “ cross over” as

used in § 577, supra, have been held to be synonymous with

the word “ trespass.” See State v. Avent, 118 S.E.2d 47

(N.C. 1961).

The trespass was wanton within the meaning of the stat

ute. Since the evidence supports a reasonable inference

that the Griffins entered the park premises and crossed

over it well knowing that they were violating the property

rights of another, their conduct in so doing was clearly

wanton. Although there are almost as many legal defini

tions of the word “ wanton” as there are appellate courts,

we think the Maryland definition, which is in line with the

general definition of the wTord in other jurisdictions, is as

good as any. In Dennis v. Baltimore Transit Co., 189 Md.

610, 56 A.2d 813 (1948), as well as in Baltimore Transit

Co. v. Faulkner, 179 Md. 598, 20 A.2d 485 (1941), it was

said that the word “ wanton” means “ characterized by

extreme recklessness and utter disregard for the rights of

others.” We see no reason why the refusal of these ap

pellants to leave the premises after having been requested

to do so was not wanton in that their conduct was in “ utter

disregard of the rights of others.” Even though their

remaining may have been no more than an aggravating

27

incident, it was nevertheless wanton within the meaning of

this criminal trespass statute. See Ex Parte Birmingham

Realty Co., 63 So. 67 (Ala. 1913).

Since it was admitted that the carrousel tickets were

obtained surreptitiously in an attempt to “ integrate” the

amusement park, we think the claim that these appellants

had taken seats on the carrousel under a bona fide claim

of right is without merit. While the statute specifically

excludes the “ entry upon or crossing over” privately owned

property by a person having a license or permission to do

so, these appellants do not come within the statutory ex

ception. In a case such as this where the operator of the

amusement park—who had a right to contract only with

those persons it chose to deal with—had not, knowingly

sold carrousel tickets to these appellants, it is apparent

that they had no bona fide claim of right to a ride thereon,

and, absent a valid right, the refusal to accept the tickets

was not a violation of any legal right of these appellants.

(ii)

We come now to the consideration of the second conten

tion of the Griffin appellants that their arrest, and convic

tion constituted an unconstitutional exercise of state power

to enforce racial segregation. We do not agree. It is true,

of course, that the park officer—in addition to being an

employee of the detective agency then under contract to

protect and enforce, among other things, the lawful racial

segregation policy of the operator of the amusement park—

was also a special deputy sheriff, but that dual capacity

did not alter his status as an agent or employee of the

operator of the park. As a special deputy sheriff, though

he was appointed by the county sheriff on the application

of the operator of the park “ for duty in connection with

the property” of such operator, he was paid wholly by the

person on whose account the appointment was made and

his power and authority as a special deputy was limited

to the area of the amusement park. See Montgomery

County Code (1955), § 2-91. As we see it, our decision in

Brews v. State, 224 Md. 186, 167 A.2d 341 (1961), is con

trolling here. The appellants in that case—in the course

of participating in a protest against the racial segrega

tion policy of the owner of an amusement park—were ar

rested for disorderly conducted committed in the presence

of regular Baltimore County police who had been called

to eject them from the park. Under similar circumstances,

the appellants in this ease—in the progress of an invasion

of another amusement park as a protest against the law

ful segregation policy of the operator of the park—were

arrested for criminal trespass committed in the presence

of a special deputy sheriff of Montgomery County (who

was also the agent of the park operator) after they had

been duly notified to leave but refused to do so. It follows—

since the offense for which these appellants were arrested

was a misdemeanor committed in the presence of the park

officer who had a right to arrest them, either in his private

capacity as an agent or employee of the operator of the

park or in his limited capacity as a special deputy sheriff

in the amusement park (see Kauffman, The Law of Arrest

in Maryland, 5 Md.L.Rev. 125, 149)—the arrest of these

appellants for a criminal trespass in this manner was no

more than if a regular police officer had been called upon

to make the arrest for a crime committed in his presence,

as was done in the Drews case. As we see it, the arrest and

conviction of these appellants for a criminal trespass as a

result of the enforcement by the operator of the park of

its lawful policy of segregation, did not constitute such

action as may fairly be said to be that of the State. The

action in this case, as in Drews, was also ‘ ‘ one step removed

from State enforcement of a policy of segregation and

violated no constitutional right of appellants.”

The judgments as to the Griffin appellants will be af

firmed.

The Case Against the Greene Appellants

There is not enough in the record to show that the

Greenes were duly notified to leave the restaurant by the

only persons who were authorized by the statute to give

notice. The record discloses that these appellants- entered

the park and crossed over it into the restaurant on the

premises, but there was no evidence that the operator or

29

lessee of the restaurant or an agent of his either advised

these appellants that they were unwelcome or warned them

to leave. There was evidence that the park officer had

ordered these appellants to leave, but it is not shown that

he was authorized to do so by the lessee, and a new written

agreement for the 1959 and 1960 seasons having been sub

stituted for the former agreement covering the 1957 and

1958 seasons, the state of the record is such that it is not

clear that the lessor had reserved the right to continue

policing the leased premises as had been the case during

the 1957-1958 period. Under these circumstances, it ap

pears that the notice given by the park officer was ineffec

tive. There is little doubt that these appellants must have

known of the racial segregation policy of the operator of

the park and that they were not welcome anywhere therein,

but where notice for a definite purpose is required, as

was the case here, knowledge is not an acceptable notice

where the required notification is incident to the infliction

of a criminal penalty. 1 Merrill, Notice, § 509. See also

Woodruff v. State, 54 So. 240 (Ala. 1911), where it was

held (at p. 240) that “ [i]n order to constitute the offense

of trespass after warning, it is necessary to show that

the warning was given by the person in possession or his

duly authorized agent.” And see Payne v. State, 12 S.W.2d

528 (Tenn. 1928), .[a court cannot convict a person of a

crime upon notice different from that expressly provided

in the statute]. Since the notice to the Greene appellants

was inadequate they should not have been convicted of

trespassing on private property, and the judgments as to

them must be reversed.

T h e J u d g m en ts A gainst t h e G r if f in A p p e l l a n t s A re

A f f ir m e d ; T h e J u d g m en ts A gainst t h e G r e e n e A p p e l

la n ts A re R e v e r se d ; T h e G r if f in A ppe l l a n t s S h a l l P ay

O n e -H alf of t h e C osts ; and M ontgom ery C o u n ty S h a l l

P ay t h e O t h e r O n e -H a l f .

(7925-1)