Estelle v. Granviel Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Estelle v. Granviel Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1981. 194fbf11-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4493498a-e6fc-41f7-9c35-cda68c303fb5/estelle-v-granviel-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1

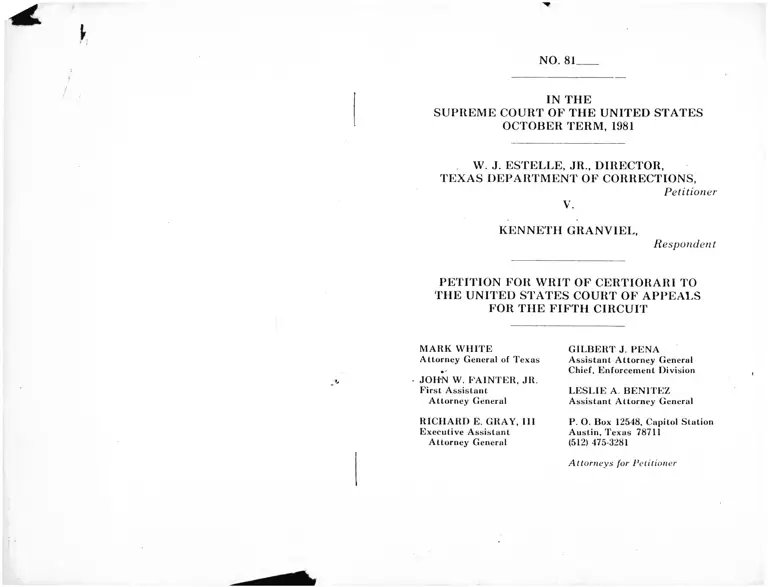

NO. 81

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM , 1981

W. J. ESTELLE, JR., DIRECTOR,

T E X A S D EPAR TM EN T OF CORRECTIONS,

Petitioner

V.

KENNETH G RANVIEL,

Respondent

PETITION FOR W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO

TH E UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE

MARK WHITE

Attorney General of Texas

- JOHN W. FAINTER, JR.

First Assistant

Attorney General

RICHARD E. GRAY, III

Executive Assistant

Attorney General

FIFTH CIRCUIT

GILBERT J. PENA

Assistant Attorney General

Chief, Enforcement Division

LESLIE A BENITEZ

Assistant Attorney General

P. O. Box 12548, Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711

(512) 475-3281

Attorneys for Petitioner

i

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

DOES THE EXCLUSION FOR CAUSE OF A

V EN IR EM AN W HO OTHERW ISE U NEQ UIVOCAL

LY AFFIRM S TH A T HE COULD NOT VOTE TO IM

POSE THE D EATH PENALTY VIOLATE THE DOC-

T R IN E OF W I T H E R S P O O N V. I L L I N O I S

BECAUSE HE USES THE W ORDS “T H IN K ” AND

“ FEEL” IN DOING SO?

SHOULD THE FEDERAL COURTS R EVIEW A

V E N IR E M A N ’S RESPONSES IN THE CONTEXT

IN W HICH TH E Y W ERE M ADE IN D ETER M IN

ING W H ETH ER HE W A S EXCUSED IN V IO L A

TION OF WITHERSPOON V. ILLINOIS?

-i-

-ii-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED *

TABLE OF AU TH ORITIES...........................................................

OPINIONS BELOW ....................................................................... 1

JURISDICTION ..................................................................................2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ...........................................................2

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT 4

ARGUMENT ........................................................................................ 4

I. THERE ARE SPECIAL AND

IMPORTANT REASONS FOR

GRANTING THE WRIT ...................................................4

II. THE EXCLUSION FOR CAUSE OF

A VENIREMAN WHO OTHERWISE

UNEQUIVOCALLY AFFIRMS THAT

IIE COULD NOT VOTE TO IMPOSE

THE DEATH PENALTY DOES NOT

VIOLATE THE DOCTRINE OF

WITHERSPOON V. ILLINOIS BECAUSE

HE USES THE WORDS -THINK"

AND "FEEL" IN DOING SO ......................................4

III. THE FEDERAL COURTS SHOULD RE

VIEW A VENIREMAN'S RESPONSES

IN THE CONTEXT IN WHICH THEY

WERE MADE IN DETERMINING

WHETHER HE WAS EXCUSED IN

VIOLATION OF WITHERSPOON V.

ILLINOIS ..........................................................................6

CONCLUSION 10

-111-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Case Fage

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586 (1978)

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510(1968)................................. ̂^

NO. 81

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1981

W . J. ESTELLE, JR., DIRECTOR,

T E X A S D EPARTM ENT OF CORRECTIONS,

Petitioner

V.

KENNETH GRANVIEL,

Respondent

PETITION FOR W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO

TH E UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

TO TH E H O N O R A B LE JU STIC E S OF TH E

SUPREME COURT:

The Petitioner respectfully prays that a writ of cer

tiorari issue to reveiw the judgment of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered in this

case on September 11, 1981.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at 1555

F 2d 673 (5th Cir. 1981) and appears as Appendix A.

The report and recommendation of the United States

Magistrate, adopted by the district court, appears as

Appendix B.

-2-

JURISD1CTI0N

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit in Granviel v Estelle was entered

on September 11, 1981. A timely filed petition for

rehearing was denied on October 13. 1981 This petition

for certiorari was filed within sixty days after final judg

ment in this case. This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

United States Constitution, art. VI, in pertinent part:

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall

enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by

an impartial jury of the State and district

wherein the crime shall have been committed...

United States Constitution, art. XIV , §, in pertinent

part:

No State shall make or enforce any law which

shall abridge the privileges or immunities of

citizens of the United States; nor shall any

State deprive any person of life, liberty, or pro- >

perty, without due process of law; nor deny to

any person within its jurisdiction the etjual pio

tection of the laws.

STATEM ENT OF TH E CASE

Respondent Kenneth Granviel was indicted for the

October 7, 1974, capital murder of Natasha McClendon

while in the cause of committing rape. On October 6,

1975, jury selection began in this capital trial. Juiy

selection was concluded on October 17, 1975, an

testimony began. On October 24, 1975, Respondent

was convicted of the capital offense. Thereafter, the

jury found as true the special issues submitted pursuan-

to Article 37.071, V.A.C.C.P., and accordingly, punish

ment was assessed at death.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the

conviction on November 10, 1976, in Granviel v State,

522 S W 2d 107 (Tex.Crim.App. 1977). Petition for cer

tiorari was denied on May 23, 1977. Granviel v. Texas,

431 U.S. 933 (1977).

A state application for habeas corpus relief was denied

after a hearing in the district court and consideration by

the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. Ex parte Gran

viel, 561 S.W.2d 503 (Tex.Crim.App. 1978).

Thereafter, Respondent filed his petition for federal

habeas corpus pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2264 u. the

United States District Court tor the Southern District

of Texas. On March 27, 1978, after a hearing, the case

was transferred to the Northern District Fort \\oith

Division. The recommendation of the Umted States

Magistrate was filed on November 27, 1978. dhe fin

dings of the Magistrate were adopted and judgment de

nying habeas corpus relief was entered on January 2b,

.1978. On January 31, 1978, Respondent’s notice of ap-

•peal was filed, and certificate of probable cause was

granted on February 1, 1978.

On September 11, 1981, a panel of the Fifth Circuit

rendered an opinion affirming the judgment m part an

reversing and remanding in part. A timely filed petitio

for rehearing was denied. This petition tor writ of cer

tiorari followed.

-4-

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W R IT

I.

T H E R E A R E S P E C IA L A N D IM P O R T A N T

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT.

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has decided

an important question of federal law which has not been,

but should be, settled by this Court. The decision of the

Court of Appeals, which applies a hypertechnical stan

dard of review to a claimed violation of Witherspoon u.

Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968), may affect most, if not all,

death penalty cases within the jurisdiction of that

Court, and may affect many other death penalty cases in

other circuits if adopted by those Courts of Appeals.

The import of the holding by the Fifth Circuit is to

establish a rigid and unwieldy test for review, so that

certain words or Lhe lack thereof have acquired a

talismanic quality, to the exclusion of a fair considera

tion of Lhe words in the context in which they were

made. Since this decision may affect so many other

cases of importance to the States, this Court should

grant the writ to review the lower court s decision.

II.

THE EXCLUSION FOR CAUSE OF A VENIREM EN

W HO OTH ERW ISE UNEQUIVOCALLY AFFIRM S

TH A T HE COULD NOT VOTE TO IMPOSE THE

D EATH PENALTY DOES NOT VIOLATE THE

DOCTRINE OF WITHERSPOON V. ILLINOIS

BECAUSE IIE USES THE W ORDS “ T H IN K ” AND

“ FE E L” IN DOING SO.

Venireman Donald L. Harrison was excluded for cause

from Respondent’s capital trial after he three times af

firmed that he could not vote to impose the death penal

ty (S.F. 708-711). The prosecutor asked

-5-

Let me ask if you, personally sitting as a juror,

could ever vote so as to inflict the death penal

ty? (S.F. 711).

When Harrison replied that he could not, the prosecutor

further inquired,

That is a definite prejudice or feeling that you

could not change? You just don’t feel like you

would be entitled to take another person’s life

in that fashion? (S.F.711).

Again, Harrison affirmed that he could not so vote, and

would not change his position. The prosecutor inquired

a third time, “ Okay. You could not? (S.F.711).

Harrison, for the third and final time, stated "No, I

could not” (S.F. 711). (Emphasis added).

The court below found that Harrison was excluded in

violation of Witherspoon, because his responses were

equivocal, due to the use of the words “ think” and

“ feel.” The court, in so holding, has applied a

hypertechnical construction to the voir dire examina

tion, and in doing so, has established a new standard of

review by federal courts.

• ■■

The record reflects that, once the import of the ques

tions was conveyed to the venireman, he never

equivocated in his position that he could never vote to

impose the penalty of death. That Harrision stated

“ no” and then added that he did not “ think” that he

could ever vote for the death penalty was no more than a

manner of speech. His added words, especially in light

of his two subsequent positive affirmations that he

could not consider or vote for the death penalty, did not

render ambiguous his clear and unequivocal position.

The questioning of Harrison focused solely upon

whether he could ever vote to impose the death penalty,

not what he “ thought” or “ felt” about the imposition of

6-

capital punishment. Harrison made unmistakably clear

that he would be unable to vote to impose the death

penalty. As stated in the dissenting opinion below,

Witherspoon mandates no precise questions

and answers. The test is ‘not to be applied with

the hypertechnical and archaic approach of a

19th century pleading book, but with realism

and rationality.'

655 F.2d at 690.

To require the State or trial court in a death penalty

case to continue to press a veniremen, where he has af

firmed three times that he could not vote for the death

penalty or follow the law, is to require the repetition of a

matter on which the juror has been clear and which is

wholly clear to the parties and the court. Further, to re

quire that a venireman affirm his position with some

specific words, but not others, is to establish a rigid and

unwieldy test so that certain words or the lack thereof

acquire a talismanic quality, to the exclusion ot a fair

consideration of the import of the words in the context

in which they were made. Such a rigid application of the

principles of Witherspoon simply is unwarranted and

places a new and quite substantial burden upon tbe

States seeking to enforce their constitutional death

penalty statutes. Because the holding of the court

below establishes a new and unwarranted standard of

federal review, this Court should grant certiorari to con

sider this issue.

III.

THE FEDERAL COURTS SHOULD R E V IE W A

V E N IR E M A N ’S RESPONSES IN THE CONTEXT

IN W H ICH T H E Y W ERE M AD E IN D ETER M IN

ING W H E TH E R HE W A S EXCUSED IN V IO L A

TION OF WITHERSPOON V. ILLINOIS.

-7-

In reviewing a claim that a venireman was excluded in

violation of Witherspoon, the federal courts should con

sider the context in which the responses were made. To

ignore the fact that the trial court previously instructed

the veniremen on the applicable law in this regard, and

that the Witherspoon standard was applied consistently

and correctly throughout the entire voir dire, and that

neither the trial court, the prosecutor or defense counsel

found the venireman’s answers equivocal, is to set up a

rigid and totally unrealistic method of review.

The record reflects that the trial court had just

previously instructed Harrison that this was a capital

case wherein there was a possibility that the death

penalty could be imposed; that the law required that

each possible penalty be considered; that each

venireman must follow the law to consider each punish

ment whether he or she agreed or disagreed with the

law; and that during individual voir dire examination

each venireman would be asked whether he or she could

follow the law (S.F. 161-162, 166-167). The subsequent

examination of Harrison should have been considered in

light of the trial’s court’s instructions.

• Further, that Harrison, the trial court, and the at

torneys saw no equivocation in the questions propound

ed or answers given is reflected by this record. Where

the venireman gives a clear answer to a question, and

then adds supporting words, whether the words render

equivocal the prior affirmation must be considered in

the appropriate context. The trial court had just in

structed Harrison that the law specified that the death

penalty was one possible punishment to be considered,

and that he must be willing to follow the law whether he

agreed or disagreed with it, and that he would be asked

whether he could follow the law in this regard. After

Harrison three times affirmed that he could never vote

to impose the death penalty, defense counsel specifically

stated that he had no questions for the venireman, and

-8-

specifically relinquished the opportunity to pursue the

matter with this venireman.' Further, that the

venireman’s responses were unequivocal is supported by

the prosecutor’s making a challenge and the trial court s

sustaining the challenge on this particular record. 1 he

entire record of the voir dire examination in this case

reveals that the prosecutor, the defense counsel and the

trial court fully understood and consistently correctly

applied the doctrine of Witherspoon. There is no ques

tion that the trial court and the prosecutor went to great

lengths to ensure compliance with Witherspoon. 1ms

fact is extremely relevant to show that the court and t le

parties heard no equivocation in the words of the

venireman and supports a finding that the venireman s

responses were anything but equivocal in the context in

which they were given. Harrison’s subsequent asser

tions, in the face of his knowledge of what was required

of him, were tantamount to assertions that he simp y

could not follow the law in the instant case. As such, his

exclusion did not violate Witherspoon. See, Lockett v.

Ohio, 438 U.S. at 596, 597.

The dissenting opinion below correctly stated that the

context in which a venireman’s responses are made is ex

tremely relevant to a review of the voir dire.

>>

While the mere demeanor of a venireman can

not contradict his express words so as to give

them a meaning in opposition to that which

they state, nevertheless, in those instances

where the meaning is apparent, elements such

as attitude and tone of voice each are relevant

factors in conveying the precise message m-

1 Although the majority opinion found that one reason defense

L n S failed u> objeh to the exclusion of Harrison was because he

did not believe an objection was necessary under state law, inis

failure to object and the explicit waiver of further examination

should be considered as further support that no one perceived ar-

rison’s responses as equivocal.

-9-

tended. The trial judge and counsel were pre

sent with the opportunity to observe and ques

tion’ Harrison. Here, we think the express

words brought forth this message loud and

clear: H arrison’s attitude toward capital

punishment would have prevented him from

making an impartial decision on both the guilt

and penalty facets of the trial. Moreover, the

action of the trial judge (who had seen and

heard) in excusing the juror, and appellant s

counsel’s failure to object, emphasize the ap

preciation of those who were present that Har

rison’s views concerning capital punishment

would substantially impair the performance of

his duties as a juror, (footnotes omitted)

655 F.2d at 690.

For the federal courts to review a claimed Wither

spoon violation without any consideration ot the con.ex

in which the questions and answers were given is to

blink reality and establish an unrealistic standard of

review. This Court should grant certiorari to consider

whether the holding in Witherspoon and its progeny re

quire such a rigid and unwieldy standard of review.

-10-

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, Petitioner prays that the petition

for writ of certiorari to the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fifth Circuit issue.

Respectfully submitted,

MARK WHITE

Attorney General of Texas

JOHN VV. FAINTER, JR.

First Assistant

Attorney General

RICHARD E. GRAY, 111

Executive Assistant

Attorney General

GILBERT J. PENA

Assistant Attorney General

Chief, Enforcement Division

LESLIE A. BENITEZ

Assistant Attorney General

P. O. Box 12548, Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711

(512) 475-3281

Attorneys for Petitioner

appendix a

1

i

.

I

A-l

NO. 79-1332

* * *

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT O FAPPEALS FOR

TH E FIFTH CIRCUIT*

KENNETH G llAN VIEL,

Petitioner- Appellan t,

V.

W. J. ESTELLE, JR., Director,

Texas Department of Corrections, ET AL,

Respondents-Appellees

* * *

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas

* * *

ON PETITION FOR REHEARING

.* (October 13, 1981)

Before AINSW ORTH and HENDERSON,

Circuit Judges,

and HUNTER*, District Judge.

PER CURIAM:

IT IS ORDERED that the petition for rehearing tiled in the

above entitled and numbered cause be and the same is hereby

denied.

*District~Judge of the Western District of Louisiana, sitting by

designation.

ENTERED FOR THE COURT:

Albert. J. Henderson

United States Circuit Judge

District Judge Hunter Dissents.

Kenneth GRANVIEL,

Petitioner-Appellant,

A-2

v.

W. J. ESTELLE, Jr., Director,

Texas Department of Corrections, et al.,

Respondents-Appellees.

No. 79-1332.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

Sept. 11, 1981.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas.

Before AINSW ORTH and HENDERSON, Circuit

Judges, and HUNTER*, District Judge. >

HENDERSON, Circuit Judge:

The appellant, Kenneth Granviel, was convicted in

the 213th Judicial District Court of Tarrant County,

Texas, of capital murder of two-year old Natasha Mc

Clendon and received the death sentence. The Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction,

* District Judge of the Western District of Louisiana, sitting by

designation.

A-3

Granviel v. State, 552 S.W.2d 107 (Tex.Civ.App. 1976),

cert, denied, 431 U.S. 933, 97 S.Ct. 2642, 53 L.Ed.2d

250 (1977), as well as the subsequent denial of state

habeas corpus relief, Ex Parte Granviel, 561 S.W.2d

503 (Tex.Cr.App. 1978). Granviel then filed a petition

for a writ of habeas corpus in the United States Dis

trict Court for the Southern District of Texas. The case

was transferred to the Northern District of Texas, Fort

Worth Division, where the petition was denied. This

appeal followed.

The gruesome details of the multiple rapes and mur

ders which resulted in Granviel’s conviction are fully

explicated in the first opinion of the Texas Court ol

Criminal Appeals, 552 S.W.2d at 110-12. Hence, we

gladly refrain from repeating them here. Suffice it to

say that altogether, and in the course of two separate

killing sprees, Granviel raped four women and stabbed

to death five women and two children. He fully con

fessed to these crimes and relied solely on the defense

of insanity at trial.

On this appeal, Granviel seeks habeas relief on four

distinct grounds. We consider the problems he raises

seriatim.

Granviel first maintains that the Texas capital sen

tencing statute, as applied in this case, violated his

rights under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.

The bifurcated procedure employed by Texas courts in

the trial of capital offenses is set out in Tex.Code Crim.

Pro.Ann. art. 37.071.Under this system, the jury first

decides the question of guilt or innocence. In the event

of a guilty verdict, a separate sentencing proceeding is

held in which additional aggravating and mitigating

evidence may be introduced. The jury then answers the

following questions on the basis of the evidence ad

duced at both phases of the trial:

(1) whether the conduct of the defendant that

caused the death of the deceased was committed

deliberately and with the reasonable expectation

that the death of the deceased or another would

result;

(2) whether there is a probability that the defend

ant would commit criminal acts of violence that

would constitute a continuing threat to society; and

(3) if raised by the evidence, whether the conduct

of the defendant in killing the deceased was unrea

sonable in response to the provocation, if any, by

the deceased. (Not applicable in this case.)

Art. 37.07.(b). The state must prove each issue sub

mitted beyond a reasonable doubt: Art. 37.071(c). If

the jury answers each of these questions affirmative

ly, the death penalty is mandatory under the terms of

the statute. A life sentence is required if the jury

responds “ no” to any one question. Art. 37.07(e). In

Granviel’s case, the jury answered “ yes” to the first

and second questions and, accordingly, the trial court

imposed the death sentence.

Granviel specifically contends that this sentenc- *

ing procedure, as applied in his particular case, did not

allow the jury to consider as a mitigating factor the

evidence of his mental instability. Rather, his mental

abnormality renders him a dangerous person who

would admittedly “ constitute a continuing threat to

society” for purposes of answering the question con

tained in art. 37.071(b)(2). Therefore, according to

Granviel, having failed to persuade the jury on the

insanity defense, the evidence of his mental condition 1 *

1. An affirmative answer requires unanimity, whereas ten of

the twelve jurors may return a negative answer. Art. 37.071(d).

A-5

could only possibly have served as an aggravating

factor at the penalty phase of the trial.-

The Supreme Court has made quite clear that the

sentencing authority in a capital case may not be

precluded from considering as a mitigating factor, any

aspect of a defendant’s character or record and any of

the circumstances of the offense that the defendant

proffers as a basis for a sentence less than death.’

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586, 604, 98 S.Ct. 2954,

2964-65, 57 L.Ed.2d 973, 990 (1978) (emphasis in the

original)! Dell v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 637, 98 S.Ct. 2977, 57

L.Ed.2d 1010 (1978); Woodson u. North Carolina, 428

U.S. 280, 96 S.Ct. 2978, .49 L.Ed.2d 944 (1976). With

this standard in mind, the Court held, in response to a

similar challenge to art. 37.0 1 1(b), that the second stat

utory question, as construed by the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals, “ allow[ed] the defendant to bring to

Neither the prosecution nor the defense presented additional

evidence at the sentencing stage. Instead, both sides chose to

rely on the record made during the-trial on guilt or innocence.

The evidence of Granviel's mental disturbance was by no

means insubstantial. As a child, he attempted several times to

burn-down his mother's house. His younger brother often ob

served him tying pillows with strips of rags to simulate the

body of a woman and then “ having sex with them.” At times, he

tried to force his brother into performing homosexual acts with

him. When he was sixteen, Granviel beat and attempted to rape

his mother, threatening to kill her, his younger brother and

himself. Thereafter, he was sent to Gatesville State School for

Boys, where he described to a psychiatrist his pleasure at stick

ing knives into meat and “ watching the blood squirt” while

working in the school kitchen. A few years after his release from

Gatesville, Granviel jumped out of a tree onto his girlfriend and

later hung her by her heels over a banister while threatening to

drop her. Approximately two weeks before the first set of mur

ders, he stood on the same girl’s stomach, beat and raped her at

gunpoint. One psychologist who testified for the defense diag

nosed Granviel as a paranoid schizophrenic.

the jury’s attention whatever mitigating circum

stances he may be able to show.” Jurek v. Texas, 428

U.S. 262, 272, 96 S.Ct. 2950, 2956, 49 L.Ed.2d 929, 939

(1976). One such mitigating factor enumerated by the

Texas court in its opinion in the Jurek case was

“ whether the defendant was under an extreme form of

mental or emotional pressure, something less, perhaps,

than insanity, but more than the emotions of the aver

age man, however inflamed, could withstand.” Jurek v.

State, 522 S.W.2d 934, 939-40 (Tex.Cr.App. 1975).

In the instant case, the Texas Court of Criminal Ap

peals met squarely Granviel’s particular challenge to

the statute, concluding:

Moreover, the jury in answering the special issues

may properly consider all the evidence adduced dur

ing both the guilt and punishment phases of the

trial. This could include evidence of a defendant’s

mental condition —whether such evidence be char

acterized as an ‘aggravating’ or ‘mitigating’ factor.

Thus, Article 37.071(b), supra, does not prevent the

jury from considering a defendant’s mental condi

tion as a mitigating factor.

561 S.W.2d at 516.

While we agree that the evidence of Granviel’s men

tal condition, when channeled through the second stat

utory inquiry, most likely had an aggravating result in

his individual case, we do not believe that the jury was

absolutely precluded from considering this evidence in

mitigation. Indeed, taking a quite different tack from

that used here, defense counsel stressed the following-

point during closing argument at the penalty phase of

the trial:

Mr. Strickland has told you the Defendant’s san

ity is no longer an issue and I agree. You have made

up your mind on that point, but it is not true that

A 6

A-7

the state of his mind, his mental condition is still an

issue not so far as a defense of insanity, but there is

not any witness who testified in this case who led

you to believe that there was nothing wrong with

this man. If he is a sociopath, you heard Dr.

Methner—they burn out. Sociopaths burn out. It s

a deep disease of youth. It is a personality disorder

of youth.

Dr. Methner also said this man could benefit from

psychiatric help.

R 3275-76. Moreover, Granviel proffered a similar

argument on his direct appeal to the Texas Court ot

Criminal Appeals. There, he maintained that because

of his “ antisocial personality disorder, the evidence

should be considered insufficient to support the jury s

affirmative answer to the second statutory question.

We also disagree with Granviel’s suggestion that art.

37 071(b)(2) is the only statutory question relevant to

our investigation.3 Art. 37.071(b)(2) requires the jury

3 The Supreme Court based its decision in Jurek v. Texas on

art. 37.071(b)(2), but stated with respect to the other statutory

*' Pr° VlSThe Texas Court of Criminal Appeals has not yet con

strued the first and third questions . . thus it is as yet

undetermined whether or not the jury s consideration of

those questions would properly include consideration of mi i

gating circumstances. In at least some situations the ques

tions could, however, comprehend such an inquiry, lo r exam

ple the third question asks whether the conduct of th

defendant was unreasonable in response to any provocation

by the deceased. This might be construed to allow the jury to

consider circumstances which, though not sufficient as a

defense to the crime itself, might nevertheless have enough

mitigating force to avoid the death penalty-a claim, for

example, that a woman who hired an assassin to kill her

husband was driven to it by his continued cruelty to her. We

cannot, however, construe the statute; that power is reserved

to the Texas courts. „

428 U.S. at 272 n. 7, 96 S.Ct. at 2956 n. 7, 49 L.Ed.2d at 938 n. 7.

A-8

to decide whether the defendant acted deliberately and

with the reasonable expectation that death would

result. This inquiry seems to be the better vehicle for

the concept of mitigation which is of primary impor

tance to Granviel, i.e., that mental disorder lessens

moral culpability.

It is true, as the NAACP maintains in its amicus

curiae brief, that a “ yes” answer to the first statutory

question logically follows from a conviction of capital

murder. See Tex.Penal Code Ann. § 19.03. However,

such is not necessarily the case. The Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals explains the inconsistency as fol

lows:

[A] jury having found that a defendant intention

ally committed a capital murder to be consistent

would have to find that the act was deliberately

done. However, the inconsistent answer to the ques

tion Art. 37.071(b)(1) reflects only that the jury did

not want the death penalty assessed.

Blansett v. State, 556 S.W.2d 322, 327 n.6 (Tex.Civ.

App. 1977). Similarly, in Brown v. State, 554 S.W.2d

677 (Tex.Cr.App. 1977), the Texas court rejected the

contention that art. 37.071(b)(1) requires the same find- t

ing as a determination of guilt under § 19.03.

It is not inconceivable that a jury, having found the

requisite intent for a conviction of capital murder and

having rejected the insanity defense, may yet conclude

that, because of evidence of mental disturbance, a de

fendant’s acts should not be deemed sufficiently delib

erate to warrant the death penalty. Here again, we note

than Granviel propounded a similar argument on his

first appeal, where he maintained that the murder of

Natasha McClendon “ occurred in a frenzy” and that

there was insufficient evidence that it was done delib

erately. 522 S.W.2d at 123. True, the Texas Court of

A-y

and the appellate court's

dence was^ufhc.ent t o ^ W ,uded from consider-

PeT h e evidence of Granviel's mental instability as a

lug the evidence o d oniy to this consider-

mitigaUng factor. He is^ntitle^t ̂ [n Ju re k ,

ation. Given th P 07 1(b)(2) and our own

T , T with respect t» art of art.

understanding of th capital-sen-

37.071(h) as a whole, we conclude thatj »e cap

tencing statute is not unconstitutional as app

Granviel.

As a second attack on the validity of his death

sentence. Granviel ̂assert! ̂that ̂ . ^ ^ ^ W i t h e r -

improperly excluded t e c - gg ^ 20 L.Ed.

2d° 776 (1968) The Witherspoon rule has been the

s u l T J * discussion since its Ptonoencement.

f ^ t d % U33“ 'M o L e /f u. B i*op . 3981138, 22 L.Ed.2d 433 (19bJ , i $

US. 262. 90 - . ~ - ; 2 d 2 2U ^ ^

u. Georgia, ~ 7o t F2d 29 (5th Cir. 1970), cei t.(1976); M ario n n. B e ta , 43 F M 29 l ̂ ^ L Ed 2d 646

'. 'denied,402 U.S. 90 , • (6th cir. 1980) (en

S 7 ;e ^ o S™ fd “ to3 its intricacies here.

S r t a t e d . ^ = ^ - » r o S

may nitted'before the trial has begun, to vote against

thtTpeiudty of death regardless of the facts and crcunv

o Pnnrt recently upheld the applicability of4. The Supreme Court Recent y P' & Adams u. Texas,

Witherspoon to ^ as ‘ u . „ , 2d 5gl (1980). We note that

448 U S 38 100 S.CL “ f > - w a s held in

Tex.Penal Code Ann. § • • j as an independent basis

Adams to have been improperly used as an P here.

for the exclusion of prospective jurors, is not

A-10

stances that might emerge in the course of the proceed

ings.” 391 U.S. at 522 n.21, 88 S.Ct. at 1777 n.21, 20

L.Ed.2d at 785 n.21. The state retains the right to

exclude only those veniremen who

ma[k]e unmistakably clear (1) that they would auto

matically vote against the imposition of capital

punishment without regard to any evidence that

might be developed at the trial of the case before

them, or (2) that their attitude toward the death

penalty would prevent them from making an impar

tial decision as to the defendant s guilt.

Id. (emphasis in original.)

Of the five veniremen whose exclusion Granviel chal

lenges,5 6 the district court held, in accordance with the

magistrate’s recommendation, that one venireman,

Donald L. Harrison, was improperly excused for cause

for merely voicing conscientious scruples against the

death penalty. We, too, believe that Harrison’s exclu

sion for cause constituted a Witherspoon violation." He

was first asked whether he had conscientious scruples

against the infliction of the death penalty, whereupon

he stated, ‘ ‘ I don’t know what that means.” When

asked if he could ever vote to inflict the death penalty,

he replied, ‘ ‘No, I don’t think 1 could.” Then, in re-^

sponse to the question, “ You just don’t feel like you

would be entitled to take another person’s life in that

fashion?” he nodded and then said, No, I could not.

These questions and answers fall far short of an affir

mation by Harrison that he would automatically vote

5. The relevant voir dire examination of each of these venire

men-Donald L. Harrison. Homer N Lipscomb, Inez Wallace,

Mrs. Hoy I. Cox and Mattie D. Vernon—is reproduced in the

Appendix.

6. We express no opinion as to the propriety of striking prospec

tive jurors Lipscomb, Wallace, Cox, and Vernon.

against the death penalty regardless of the evidence

nr ^hat his objections to capital punishment won d

prevent him from making an impartial decision as to

guilt.

This court recently reaffirmed its commitment Lo

ensuring strict adherence to the mtindates <itWiiiher-

ZTonin Burns u.Estelle. 626 F.2d 396 (5th Cir. 19801

(en banc). There, we explained the improper exclusion

of a prospective juror as follows:

ITlhree times in succession Mrs. Doss stated that

she did not believe in the death penalty, M ow ing

with an affirmation that it would affect her del,be,

ations on any issue af tact in the e ^ e . Thesse are

strong expressions indeed, but they fall short of

unequivocal avowals disqualifying her under eit e

aspect of Witherspoon’s two-pronged test------

626 F2d at 397-98. Mr. Harrison's equivocation differs

slightly in kind from that of Mrs. Doss, but is certainly

of no lesser degree. While Mrs. Doss stated that the

nossibility of the death penalty would affect her

deliberations on any issue of fact, Mr. Harrison made

no such representations and, indeed, was never quo

Honed as to whether his attitude toward the death

penalty would prevent him from making an impartia

determination as to guilt. Further, Mrs. Doss s re

peated disclosures that she did not believe in the deat

penalty were no less indicative of an automatic vo

against the imposition of caP{ a ^pU.nl,sh^ e^ e\ he

Mr Harrison's statement that he did not feel that he

would be entitled to take another person s life.

13! Normally, our determination that veniremen

Ha risen waslmproper.y excused would conclude ou

inuuirv for if just one prospective juror is struck for

reasons insufficient under the death pe

S ty must be set aside. Davis u. Georgia, supra. Ma-

A-12

non v. Beto, supra. However, in the instant ease, the

district court, again following the magistrate’s recom

mendation, held that defense counsel’s failure to con

temporaneously object to the improper exclusion

amounted to a waiver of the Witherspoon error.

The Supreme Court established in Wainwright v.

Sykes, 433 U.3. 72. 97 S.Ct. 2497, 53 L.Ed.2d 594

(1977), that a state procedural waiver of a constitu

tional claim bars federal habeas corpus review absent a

showing of “ cause" and “ prejudice.’ ’ The prejudice

resulting from the exclusion of a juror in violation of

Witherspoon can hardly be questioned in light of deci

sions such as Davis v. Georgia and Marion v. Beto.

Granviel maintains that the cause for the failure to

object was the reliance by defense counsel on Texas

case law which, at the time of his trial, indicated that a

contemporaneous objection was not a prerequisite to

the subsequent assertion of a Witherspoon error. It

would seem, however, that the absence of a state con

temporaneous objection rule would render the Sykes

issues irrelevant. Thus, we turn to Granviel’s conten

tion that there was no such rule in Texas in October of

1975.

In Tezeno v. State. 484 S.W.2d 374 (Tex.Cr.App.>

1972), the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals enter

tained Witherspoon challenges to the exclusion of sev

eral jurors, including one whose voir dire examination

was much the same as that of venireman Harrison.7

7. Do you have any conscientious scruples against the assess

ment of death as a punishment for the crime of murder, in a

proper case, sir?

A Yes, sir, I do.

Q I take it, by your answer, then, that there are no facts or

circumstances whatever, that would justify you, personally,

in rendering a death verdict in a murder case?

(footnote continued on following page)

A-13

The court concluded (incorrectly, we believe) that no

violation occurred, but nevertheless reached the merits

of the Witherspoon claim even though defense counsel

had expressly stated that he had no objection to the

challenge for cause. The court reasoned as follows:

Waiver of objection apparently will not, in itself,

vitiate an improper challenge. It is, however, a fac

tor to be considered in cases such as the one at bar,

where the exact meaning of a venireman’s answer

cannot be ascertained with total accuracy trom the

words of his answer alone.

484 S.W.2d at 383 n.2. .

On April 30, 1975, the Texas Court of Criminal Ap

peals decided Hovila v. State, 532 S.W.2,d 293 (Tex.Ci.

App. 1975), holding that several jurors were struck for

reasons insufficient under Witherspoon. Defense coun

sel had voiced no contemporaneous objections to the

improper exclusions, and yet the court did not even

mention the possibility of waiver.

It was not until its decision in Boulware v. State, 542

S.W.2d 677 (Tex.Cr.App. 1976), where it expressly

’ overruled Hovila and Tezeno, that the Texas court held

that the failure to object constituted a waiver of a.

(footnote continued from previous page)

A I don’t believe I could.

Q All right. You're just absolutely opposed to that penalty,

on conscientious grounds?

A Yes, sir.

Q Thank you, sir.

Mil. BENNETT: We’ll challenge for cause.

MR. CALDWELL: No objections, Your Honor.

THE COURT: All right. You’re excused, Mr. Juror.

484 S.W.2d at 382-83.

A-14

Witherspoon claim. We cannot enforce against Gran-

viel a contemporaneous objection rule that apparently

did not even exist at the time of his trial.

We must admit that we reach this result reluctantly

and without great satisfaction. We obviously do not

have here the situation perceived by Judge Goldberg

in his opinion in Jurek v. Estelle, 593 F.2d 672 (5th Cir.

1979), now vacated by the decision of the court on

banc,’ 623 F.2d 929 (19S0) (see 5th Cir. Rule 17). He

concluded that Jurek's trial counsel was either igno

rant of the Witherspoon holding or that he misunder

stood it, thus explaining his failure to object to im

proper exclusions. Granviel's counsel was well-aware

of the Witherspoon rule, as his objections to certain

lines of questioning demonstrate.9 He did, in fact, ob

ject to the exclusion of Mattie D. Vernon on Wither

8. The treatment given Granviel’s Witherspoon claims on his

direct appeal is somewhat confusing. The Texas court discussed

the responses of each of the five veniremen, implying that exclu

sion was proper. Then, as to each one (except Mattie D. Vernon,

whose exclusion did elicit an objection), it cited Boulware in

concluding no error was shown. 552 S.VV.id 112-14.

9. I ’m going to object. That is an improper question, whether it

would be in conflict with religious feelings.

R.1058.

I object. The most the State can demand is a person be

willing to consider all the penalties.

R. 1059-60. I

I will object to that as being an improper question. The

question is whether cr not she would unequivocally and

automatically vote against it in every case.

R.1725.

By the same token, the prosecutor and the trial judge were

also cognizant of the need to comply with Witherspoon. Indeed,

the observation made by Judge Gee in Burns v. Estelle, 592 F2d

(footnote continued on foilouinp puge)

A-15

spoon grounds.10 As to the other challenged exclusions,

defense counsel testified at the state habeas nearing

that he deliberately chose not to object because he felt

he was not required to do so under Texas law e

cannot condone such tactics. Indeed, we agree with the

state’s assessment that “ [t]o fail to object when coun

sel perceives error is to undermine the mtegnty of the

judicial process.” However, faced with the apparent

absence of a Texas contemporaneous objection rule at

the time of Granviel's trial, and ever-mindful of the

gravity of a Witherspoon transgression and tne conse

quences of precluding its assertion, we decide that the

error in excluding venireman Harrison was not waived.

Accordingly, Granviel’s death sentence cannot stand.

As his third ground of error, Granviel asserts that

the allowance of certain psychiatric testimony at t e

guilt phase of the trial violated the attorney-client

privilege and resulted in the deprivation ot his Sixth

(footnote continued from previous page)

*' 1297- 1302 (5th Cir. 1979), reheard en banc, 626 F.2d 396 (1980),

is equally applicable here: “ [M]uch of the voir dire concerned the

Wi therspoon problem; the trial judge's comments and questions

clearly indicate that his attention was focused upon it during

the entire process of cutting the panel.” In Burns, these factors

militated against the finding of a waiver. The en banc opinion

reaffirmed the panel’s holding on the merits, thus implicitly

approving the discussion of the waiver issue.

10 For the purpose of the record, I am going to object to the

exclusion of Mrs. Mattie D. Vernon on the grounds her ques

tions (sic) were less than unequivocal and never did she say

she would automatically vote against the death penalty in

every case. . ..

11.1728.

A ' i O

Amendment right to effective assistance of counsel.1'

Since our resolution of this issue is largely dependent

on certain aspects of Texas law, we find the Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals’ analysis of the problem on

Granviel’s direct appeal most helpful, both as to the

facts and the relevant state law:

Appellant contends that the attorney-client privi

lege was violated by the State’s subpoenaing and

calling to the witness stand psychiatrist John T.

Holbrook, who was appointed to examine appellant

at the request of appellant’s court appointed coun

sel. Appellant contends that Dr. Holbrook was an

agent of appellant’s trial counsel because he was

employed to assist them in the preparation of the

defense in the trial. The appellant s only detense is

that he was insane at the time of the commission of

the offense.

On the written request of appellant the couit ap

pointed Charles Dickens and Frank Sullivan, Es

quires, practicing attorneys to defend him on Feb- 11

11 We assume that Granviel employs this argument as an at-

' tack upon the conviction itself, and that it is not another chal

lenge aimed solely at the validity of his death sentence. We note,

however, that he does not specifically complain that the psychia

trist’s testimony weakened his insanity defense, but rather that

it damaged him in relation to the jury’s determination under

Art 37 071(b)(2). And yet, our examination of the record reveals

no testimony by Dr. Holbrook which touched directly on the

issue of Granviel’s future dangerousness. Rather, the import of

his testimony was that Granviel suffered from no psychosis and

that he was sane, within the legal definition, at the time of the

commission of the offenses. As we mentioned previously, neither

the prosecution nor the defense offered additional testimony at

the separate sentencing phase of the trial. Also, the prosecutor s

only reference to Dr. Holbrook’s testimony during arguments at

the penalty phase was that “ Dr. Holbrook said he [Granviell

should be held accountable for what he did.” It.3291.

ruary 13, 1975. Appellant’s counsel then contacted

Dr. Holbrook, a psychiatrist, some time before

April 26, 1975, and requested him to examine appel

lant in the Tarrant County Jail. These examinations

were made on April 26 and May 16, 1975. Present

at both examinations were the psychiatrist, appel

lant and counsel. Dr. Holbrook stated that appel

lant satisfactorily communicated with him and re

sponded to his questions during the examination.

On May 22, 1975, upon counsel’s written motion,

the trial court appointed Dr. John 1. Holbrook to

examine the defendant in the Tarrant County Jail

at any and all times that are convenient both to I h .

John Holbrook and the Sheriff. On the same date

the court upon appellant’s counsel s written notice

appointed Dr. M. Jerold May to administer psycho

logical tests to appellant at his office in Fort Worth,

which tests were made at a later date. On August 9,

1975, upon the State’s request the court appointed

Dr. Hugh Brown, a psychiatrist, to examine appel

lant at the Tarrant County Jail. Dr. Brown wioi.e

the court of his inability to examine appellant be

cause appellant refused to talk to him without Ida

counsel being present. Dr. John Methner, a court

appointed psychiatrist requested by the State;, tes

tified that on April 13, 1975. when he tried to exam

ine the appellant in the presence of his counsel, he

was unable to do so because appellant refused to

talk to him or cooperate for the examination. Coun

sel stated that he advised the appellant that he did

not have to talk to the psychiatrist (Dr. Methner);

however, the psychiatrist did get to observe appel

lant for a while.

Art. 46.02, Sec. 2(f), V.A.C.C.P., as amended Au

gust 30, 1971, and effective at the date of the ap

pointment of Dr. Holbrook on May 22, 1975, pro

vides;

/wt>

‘ (1) The court may, at its discretion appoint dis

interested qualified experts to examine the de

fendant with regard to his present competency

to stand trial and as to his sanity, and to testify

thereto at any trial or hearing in connection to

the accusation against the accused . . .

* * * * * *

(4) No statement made by the defendant during

examination into his competency shall be admit

ted in evidence against the accused on the issue

of guilt in any criminal proceeding no matter

under what circumstances such examination

takes place.

(5) Any party may introduce other competent

testimony regarding the defendant’s compe

tency.’

Under this statute, the trial court’s allowing Dr.

Holbrook to testify was proper. ‘[AJppoint disinter

ested qualified experts to examine the defendant

. . .’ clearly means that such expert is not appointed

by the court as the expert of the State or the de

fense, but is the court’s disinterested expert. He

may appoint such expert at his discretion and with

out a motion therefore (sic), and either party may

subpoena such witness. Therefore, no attorney-cli

ent privilege exists as to Dr. Holbrook.

In Stultz v. State, [Tex.Cr.App.], 500 S.W.2d 853,

this Court said:

‘A psychiatric examination is not an adversary

proceeding. Its purpose is not to aid in establish

ment of facts showing that an accused commit

ted certain acts constituting a crime; rather, its

sole purpose is to enable an expert to form an

opinion as to an accused’s mental capacity to

form a criminal intent.

Because of the intimate, personal and highly

subjective nature of a psychiatric examination,

the presence of a third party in a legal and non

medical capacity would severely limit the effi

cacy of the examination . . (Emphasis added.)

Compare Walker v. State, Tex.Cr.lt. 176 (1885).

See also Gholson v. State, Tex.Cr.App., 542 S.W.2d

395 (1976).

Art. 46.03, Sec. 3, V.A.C.C.P. effective June 19,

1975, provides as follows:

‘(a) If notice of intention to raise the insanity

defense is filed under Section 2 of this article,

the court may, on its own motion or motion by

the defendant, his counsel, or the prosecuting

attorney, appoint disinterested experts experi

enced and qualified in mental health or mental

retardation to examine the defendant with re

gard to the insanity defenses and to testify

thereto at any trial or hearing on this issue, but

the court may not order the defendant to a state

mental hospital for examination without the

consent of the head of the state menLal hospital.

* * * * * *

(d) A written report of the examination shall be

submitted to the court within 21 days of the

order of examination and the court shall furnish

copies of the report to the defense counsel and

the prosecuting attorney. The report shall in

clude a description of the procedures used in the

examination and the examiner’s observations

and findings pertaining to Lhe insanity delense.

A-20

* * * * * *

(g) The experts appointed under this section to

examine the defendant with regard to the insan

ity defense also may be appointed by the court

to examine the defendant with regard to his

competency to stand trial pursuant to Section 3

of Article 46.02 of this code, provided that sepa

rate written reports concerning the defendant’s

competency to stand trial and the insanity de

fense shall be filed with the court.’

Cf. Article 46.02, Sec. 3, V.A.C.C.P. (Incompetency

to stand trial).

A procedural statute controls litigation from its

effective date. Wilson v. State, Tex.Cr.App., 473

S.W.2d 532. The trial o'f the instant case was in

October 1975, and Article 46.03, Sec. 3, supra, was

then effective and controlling. Wilson, supra. Cf.

McCarter v. State, [Tex.Cr.App.], 527 S.W.2d 296.

Articles 46.03 and 46.02, supra, negate the con

tention of appellant that the attorney-client privi

lege was violated. Both the State and appellant had

the right to subpoena the psychiatrist and adduce

his testimony at the trial. There is no difference in

the result when the examinations were completed

before the appointment was made, as in the instant

case, and when a psychiatrist is appointed by the

court and then makes his examination.

Communications between a physician and his pa

tient are not privileged under Texas Law. Texas has

no statute establishing the privilege and the courts

invariably deny its recognition. See Bonewald u.

State, 157 Tex.Cr.R. 521, 251 S.W.2d 255.

* * * * * *

A-21

There is no affirmative evidence in the instant

case showing that Dr. Holbrook revealed any fact or

communication between him and appellant showing

that appellant committed a crime of any nature. The

testimony shows to the contrary that Dr. Holbrook

never communicated to anyone in the disLrict attor

ney’s office any such statements or facts, if any,

resulting from the examinations he made of appel

lant as to his sanity or his competency. Therefore,

Article 46.02, Sec. 2(f)(4), supra, and Article 46.03,

Sec. 3, supra, have not been violated.

Appellant claims that Dr. Holbrook’s examina

tion was necessary to. his defense of insanity and

failure to request the examination would have been

ineffective assistance of counsel. Appellant contends

that by employing Dr. Holbrook he created an invol

untary State’s witness who gave testimony adverse

to appellant relating to Special Issue No. 2 under

Article 36.071(b)(2), V.A.C.C.P. In view of our pre

vious discussion of the status of Dr. Holbrook as a

disinterested expert witness under Articles 46.02,

Sec. 2(f) and 46.03, Sec. 3, this contention is without

merit.

562 S.YV.2d at 114-17. (Emphasis in original.)

Granviel admits that, in order to prevail on this

issue, he must establish that his conversations with Dr.

Holbrook were protected within the attorney-client priv

ilege as iL exists in Texas. However, it is clear that under

Texas law, as interpreted by the Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals, the attorney-client privilege does not attach in

this situation. Rather, psychiatrists or psychologists

who examine a defendant with respect to competency or

insanity are designated as “ disinterested qualified ex

perts.” As such, they may be subpoenaed by either

party and they are not, as Granviel suggests, agents of

either defense counsel or the prosecutor.

A 22

We realize thaL several state courts have, indeed

adopted the ru.e advocated b , Orjnvid.

Franciscan Superior Court, 37 CaL2d 227 231 K2d2b

(1951)' State v. Kociolek, 23 N.J. 400, - . .

(1957) Also, the Third Circuit, faced with a remarkably

similar set of facts, concluded that the attorneJ '^ ieiJ

privilege should be recognized when a psychiatnst

secured by defense counsel for assistance-.in trial.prepa

ration. United States v. Alvarez, 519 F.2d 1036 (3d Cir

1975) 12 However, it did so in the context o a ire

appeal from a federal conviction. We are not here decid

ing the scope and appropriate application ot the attor

ney-client privilege for federal criminal proceedings,

hence, we are not at liberty to flatly agree or disagree

with the Third Circuit rule. Rather, we must determine

whether such a rule of privilege, though perhaps prefer

red, is constitutionally required.

12 The court analogized the case to United States v. Kovel, 2JG

F.2d 918 (2d Cir. 19(31), where the Second Circuit held the pr -

lege applicable to communications made to an accountant tor

the purposes of aiding counsel in preparing a defense_ Fro

there, it reasoned that the appellant had been denied effective

assistance of counsel, as follows: .

' The issue here is whether a defense counsel in a czsemvoW-

ing a potential defense of insanity must run the risk that ^

psychiatric expert whom he hires to advise him with respect

to the defendant's mental condition may be forced to be an

involuntary government witness. The effect of such a ru

would we think, have the inevitable effect ot depriving d

fendants of the effective assistance of counsel in such cases.

A psychiatrist will of necessity make inquiry about the facts

surrounding the alleged crime, just as the attorney ̂ wil

Disclosures made to the attorney cannot be used to furnish

proof in the government’s case. Disclosures made to th

attorney’s expert should be equally unavailable, at least un

til he is placed on the witness stand. The attorney must be

free to make an informed judgment with respect to the best

course for the defense without the inhibition of creating a

potential government witness.

519 F2d at 1046-47.

[5! In concluding that there is no such constitutional

mandate, we substantially agree with the rationale of

Judge Weinstein in his excellent and thorough opinion in

Edney v. Smith, 425 F.Supp. 1038 (E.D.N.Y. 1976), aff'd,

556 F.2d 556 (2d Cir. 1977), a habeas corpus case which,

for our present purposes, involved essentially the same

facts 1:1 Recognizing that the defendant might suffer

prejudice as a result of the New York rule allowing the

psychiatrist to testify, Judge Weinstein inquired as to

whether “ ihe balance drawn by New York is so detri

mental to Lhe attorney's effective representation of his

client as to be prohibited by the Sixth Amendment.” 42o

F.Supp. at 1053." He then answered this question nega

tively:

We can only speculate that the New York rule

results in substantial prejudice to criminal defend

ants.

The statements by the defendant to his psychia

trist were not admitted to establish the fact of his

having committed the murder, but only to establish a

basis for the psychiatrist's evaluation of petitioner's

sanity at the time of the offense."51 Given this limited

use, any possible prejudice may be balanced, within 13 14 *

13 in Edney, the New York state court had not held, as the

Texas court did here, that the attorney-client privilege was inap

plicable, but rather that it had been waived by Lhe mere asser

tion of the insanity defense. People v. Edney, 39 N.Y.2d 620, 38o

N.Y.S.2d 23, 350 N.E.2d 400 (1976). As a practical matter, there

would seem to be little difference in the effects of these two

approaches.

14 Judge Weinstein noted that the Alvarez court, although us

ing language “ constitutional in tone,” did not have a constitu

tional question before it.

15. In the instant case, Dr. Holbrook did not relate to anyone the

statements made to him by Granviel, but only his expert opin

ion derived from the psychiatric examination,

A-21

limits not exceeded in this case, by the strong

counter-balancing interest of the State in accurate

fact-finding by its courts.

In sum, it seems undesirable at this time to can

onize the majority rule on the attorney-psychiatrist-

client privilege and freeze it into a constitutional

form not amenable to change by rule, statute, or

further case-law development.

425 F.Supp. at 1054.

We are especially driven to this outcome in this case

where Granviel, at his counsel’s urging, refused to coop

erate with the experts who were appointed at the prose

cution’s request.'* As other circuit courts have noted:

It would be a strange situation, indeed, if first,

the government is to be compelled to afford the.de

fense ample psychiatric service and evidence at gov

ernment expense, and, second, if the government is

to have the burden of proof—and yet it is to be denied

the opportunity to have its own corresponding and

verifying examination, a step which perhaps is the

most trustworthy means of attempting to meet that

burden.

United States u. Albright, 388 F.2d 719, 724 (4th Cir.

1968), Quoting Pope v. United States, 372 F.2d 710, 720

(8th Cir. 1967), vacated and remanded on other grounds,

392 U.S. 651, 88 S.Ct. 2145, 20 L.Ed.2d 1317 (1968).

This court made a similar observation in the context of a

federal prosecution:

16. In federal courts, such refusal could result in the exclusion of

any expert testimony offered by the defendant on the issue of

his mental state. See Fed.R.Crim.P. 12.2(d).

A - Z . )

[T]he government will seldom have a satisfactory

method of meeting defendant’s proof on the issue of

sanity except by the testimony of a psychiatrist it

selects—including, perhaps, the testimony of psychi

atric experts offered by him—who has had the oppor

tunity to form a reliable opinion by examining the

accused.

United States v. Cohen, 530 F.2d 43, 48 (5th Cir. 1976)

(footnote omitted). Hence, we hold that Granviel is not

entitled to habeas relief on the attorney-client and Sixth

Amendment grounds.16 17

[61 Granviel finally urges that he was deprived of his

Sixth Amendment right of confrontation by the intro

duction of hospital records containing diagnostic opin

ions. These records were presented by the State to rebut

defense evidence that Granviel had been hospitalized for

insanity.

Texas recognizes the business records exception to

the hearsay rule, Tex.Rev.Civ.Stat.Ann art 3737e, and

applies it in criminal as well as civil cases, Coulter v.

State, 494 S.W.2d 876 (Tex.Cr.App. 1973). Granviel com

plains that the state did not strictly adhere to the proce

dural requirements of art. 3737e, and, further, that the

"diagnostic opinion in question lacked the requisite trust

worthiness. However, at the trial, defense counsel

17. We note that the issues of the Fifth Amendment privilege

against compelled self-incrimination and the Sixth Amendment

right to counsel which underlie the Supreme Court’s recent

decision in Estelle v. Smith,___ U.S. ____ , 101 S.Ct. 1866, 68

L.Ed.2d 359 (1981), are not involved here. Granviel and his

attorneys were certainly aware that the prosecution intended to

call Dr. Ilolbrook as a witness and they knew of the conclusions

and the expert opinion to which he would testify. Further, Gran

viel was in no way compelled to submit to the examination by

Holbrook.

A -26

merely objected to the admission of the evidence on the

ground that it was “ hearsay." The Texas oourt of crimi

nal Appeals held this objection insufficient, 552 S.W.2d

at 121-22 citing its previous opinions in Forbes v.

State, 513 S.W.2d 72 (Tex.Cr.App. 1974); Williams v.

State, 531 S.W.2d 606 (Tex.Cr.App. 1976) (objection

must be contemporaneous); and Bouchillon v. State, a40

S.W.2d 319 (Tex.Cr.App. 1976) (objection too general

properly overruled). Granviel having failed to demon

strate “ cause" and “ prejudice” in connection with the

inadequate objection, see Waiiiwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S.

72, 97 S.Ct. 2497, 53 L.Ed.2d 594 (1977), habeas corpus

relief was properly denied on this ground.

Accordingly, petitioner s death sentence must be set

aside, and the judgment of the district court is reversed

insofar as it leaves the death sentence in effect. In all

other respects the judgment is affirmed. Ih e case is

remanded to the district court with directions that the

State of Texas determine within a reasonable time

whether (1) to conduct a new sentencing proceeding in

the manner provided by state statute, or (2) to vacate

petitioner’s sentence and impose a sentence less than

death in accordance with state law.'"

A FFIR M ED IN PART; REVERSED IN PART,

AND R EM AN D ED FOR FURTHER PROCEEDINGS-

IN ACCORDANCE W ITH TH IS OPINION.

18. Marion v. Beto, 434 F.2d 29 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402

U.S. 906, 91 S.Ct. 1372, 28 L.Ed.2d 646 (1971).

APPEN D IX

DONALD L. HARRISON

Q; (By Prosecutor) The defendant in this case is

charged with capital murder. There are only two punish

ments for the offense of capital murder and that is either

death or life in the penitentiary.

Now, do you have conscientious scruples against

the infliction of the death penalty as a punishment

for crime?

A: I don’t know what that means.

Q: Let me ask you if you, personally sitting as a

Juror, could ever vote so as to inflict the death penalty?

A: No, 1 don’t think I could.

Q: That is a definite prejudice or feeling that you

have that you would not change? You just don’t feel like

you would be entitled to take another person s life in

that fashion.

A: (Venireman nods.)

• r

Q: Okay, you could not?

A; No. I could not.

MR. W ILSON; We challenge. Your Honor.

THE COURT: The defense have any objections?

MR. DICKENS: We don’t have any questions.

THE COTJRT: All right.

A - Z t l

The Court feels that the State’s challenge for

cause is qualified in this cause and supported by

the evidence.

You will be excused, then, Mr. Harrison. Thank

you very much. (R. 711-12).

HOM ER N. LIPSCOMB

Q: (By Prosecutor) . . . There are only two possible

punishments for capital murder, and that is lile or death.

Now, bearing in mind the fact that this is a capital

murder situation, I will ask you whether or not you

have any conscientious or religious scruples against

the imposition of the death penalty in a proper case?

A: I ’m not very religious but T do have. I am kind of

against the death penalty.

Q: Kind of against the death penalty. I appreciate

your candor, and of course that is why we need to ask

you these questions.

When you say you are kind of against the death

penalty, what do you mean by that?

A: I mean it would have to be, you know, 1 really

don’t know what I am, but I just wouldn t want to be a

part of it.

Q: I understand that.

Of course, nobody thinks it s a very pleasant occa

sion, nobody thinks that it’s something they would

particularly want to do, but the question is, of

course, whether or not you yourself could peisonally

take part in making decisions which you knew would

result in the death of a human being.

A: I don’t think I would.

Q: You don’t think you could?

Well, you understand I have no argument with

that position, but it’s necessary that we find out

exactly how you feel about it.

Is what you are saying that you have personal

and deep-seated feelings which would prevent you

from rendering a decision which would result in the

death of a person in any case whatsoevei ?

A: I don’t feel like I am that kind of a judge.

O: You don’t think you could imagine any sort of

case in which you feel the death penalty would be justi

fied, then?

A: No.

O' By that you mean you would automatically vote

against the infliction of the death penalty, no matter

what the facts were in a particular case!

A: I might consider it, but I automatically would

Tight now.

Q: You would automatically vote against the impo

sition no matter what the trial would reveal?

A: Yes.

Q: And no matter what these facts reveal no mat

ter how terrible the crime might be, that would not be

enough to cause you to set aside your personal deep

convictions regarding this matter?

A: I wouldn’t want that on my mind.

A-30

Q: And this is a firm conviction, I take it, from

what you have said?

A: Yes.

Q: And it’s the sort of conviction which you are not

going to let anybody talk you out of, presumably some

thing within yourself and of course you have to live with

yourself and your convictions and it’s something you

believe in and you are not going to let anybody talk you

out of that?

A: Yes.

Q: I appreciate you telling that, Mr. Lipscomb, and

we do appreciate your candor.

MR. STRICKLAND: Your Honor, it’s the posi

tion of the State these are sincere and deep seated

convictions and as such we would challenge Mr. Lips

comb for cause.

THE COURT: The challenge is granted under

the authority of Witherspoon in (sic) Illinois. (R.

809-11).

INEZ WALLACE

Q: (By Prosecutor) . . . I ’d like to ask you now

whether you personally have any conscientious or reli

gious scruples against the imposition of the death pen

alty in a proper case?

A: Well, the truth. I don’t know exactly how I feel

in that way.

Q: Of course, I can understand that. It ’s a serious

point, but it’s something we need to talk about because

obviously if we are only faced with two possible alterna

tives, we need to make sure we have jurors that are able

to consider both of those alternatives.

Have you been able to give it some thought?

Have you thought about this question, say, before

you came over here on jury service?

A: Well, I do believe in the Bible and I don’t think

no one should kill anyone.

Q: Okay. Let’s talk about that, if I may, for a while.

You say, ‘ I believe in the Bible,’ and you believe in the

things that it teaches you and no one should kill. By that

are you saying you don’t feel that you could give consid

eration to the death penalty regardless of what the facts

might show in a case?

A: Well, I believe I could do that.

Q: You believe you could consider the death penalty

and you don’t feel that would in any way conflict with

your religious feelings; is that right?

MR. DICKENS: I ’m going to object. That is an

improper question, whether it would be in conflict

with religious feelings. Certainly perhaps the death

penalty might be.

THE COURT: Sustained.

MR. STRICKLAND: If I may make a state

ment to that. I think Witherspoon allows us to in

quire as to whether they have religious scruples and

that is the point of my inquiry.

THE COURT: I agree it is.

BY MR. STRICKLAND:

Q: Now, understanding that, I assume that no one

would like to be involved in a death penalty situation,

that is, it’s not a pleasant task for anybody, you under

stand that, but what I need to know is whether you

yourself could personally take part in a trial and pei son-

ally make decisions which might result in the death of

another human being?

A: I don’t think I could.

Q: You don’t think you could. Well, you understand

1 don’t have any quarrel with that position. All we need

to do is we need, if that is your conviction and those are

your deep and sincere feelings, well, of course, you aie

certainly entitled to those.

Are you saying, then, you have a deep-seated feel

ing that would prevent you from being able to take

part in rendering a death penalty?

A: Yes, sir, I just don’t believe in it.

Q: You just don’t believe in the death penalty? Re

gardless of what the facts are, you just don’t believe

people ought to take another person’s life?

A: I don’t know what else to say. I just don t . . .

Q: I understand, number one, it may be sincere feel

ings and number two, I realize it may be something you

haven’t really had to experience before. You have

thought about it but you haven’t had to say anything.

Well, you have just told me you don’t think you believe

in the death penalty and question 1 would have is are

your feelings of such a nature or are your feelings so

deep that no matter what the facts were, you just would

not be able to give another person the death penalty or

consider it?

MR. DICKENS: I object. The most the State

can demand is a person be willing to consider all the

penalties, Your Honor, and I object for that reason,

and the way he phrases that question.

THE COURT: Overruled.

BY MR. STRICKLAND:

Q: Should I ask the question again, or did you un

derstand?

A: What was the question?

Q: Well, let me ask it this way: Are you saying that

the feelings you have and what you have already told us

about these leelings you have that people should not

take another person’s life, are those feelings such no

matter what you heard in a trial like this, no matter

what you heard, you could be able to even consider

giving a person the death penalty? You would just say,

‘No, I ’m sorry. I am just not going to take part in that’?

A: I don t know. That is kind of hard.

Q: I understand.

•r

Well, of course, you understand that both sides

and of course the Defendant, also, need to know if

you would just automatically say you would not con

sider one of these, that is what we need to know and

what is the purpose of us talking here this afternoon.

MR. SULLIVAN: Your Honor, I would object to

this continual line of repetitive questioning. This

Venirewoman has testilied she could consider the

death penalty if the facts warranted it; therefore the

question ol the Prosecutor is improper and repeti

tious.

A-U4

THE COURT: Overrule the objection.

MR. SULLIVAN: Please note my exception.

BY MR. STRICKLAND:

Q: Now, you understand if that is the way you

feel—as I indicated. I don’t have any quarrel with the

way you feel, hut all we need to know is precisely how

you do feel and if I misunderstood you, set me straight.

I thought you said you did not feel that you could

participate in a trial in which the death penalty might be

inflicted upon somebody? Did I understand you right?

A: Well, I say that is just how I feel. 1 wouldn’t like

to participate in it.

Q: Let me ask you this: Nobody would like to, I

figure nobody really would like to be involved in some

thing like that, but could you be involved? Would you

set aside your feelings and just say, ‘Well, I ’m going to

go ahead anyway and do it,’ or are those feelings so

strong you’d say, ‘Well, I am not going to be involved’?

A: I just don’t think I could.

Q: And this is a pretty deep and firm conviction you

have; is that correct?

A: (Venirewoman nods.)

Q: And you are not going to let anybody talk you

out of that conviction, I presume? Is that pretty right?

Something you believe in and you are just not going to