McLaughlin v. Florida Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McLaughlin v. Florida Reply Brief for Appellants, 1964. a18b5463-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/44a37342-b9b1-466e-b06f-732dbdb93c8b/mclaughlin-v-florida-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

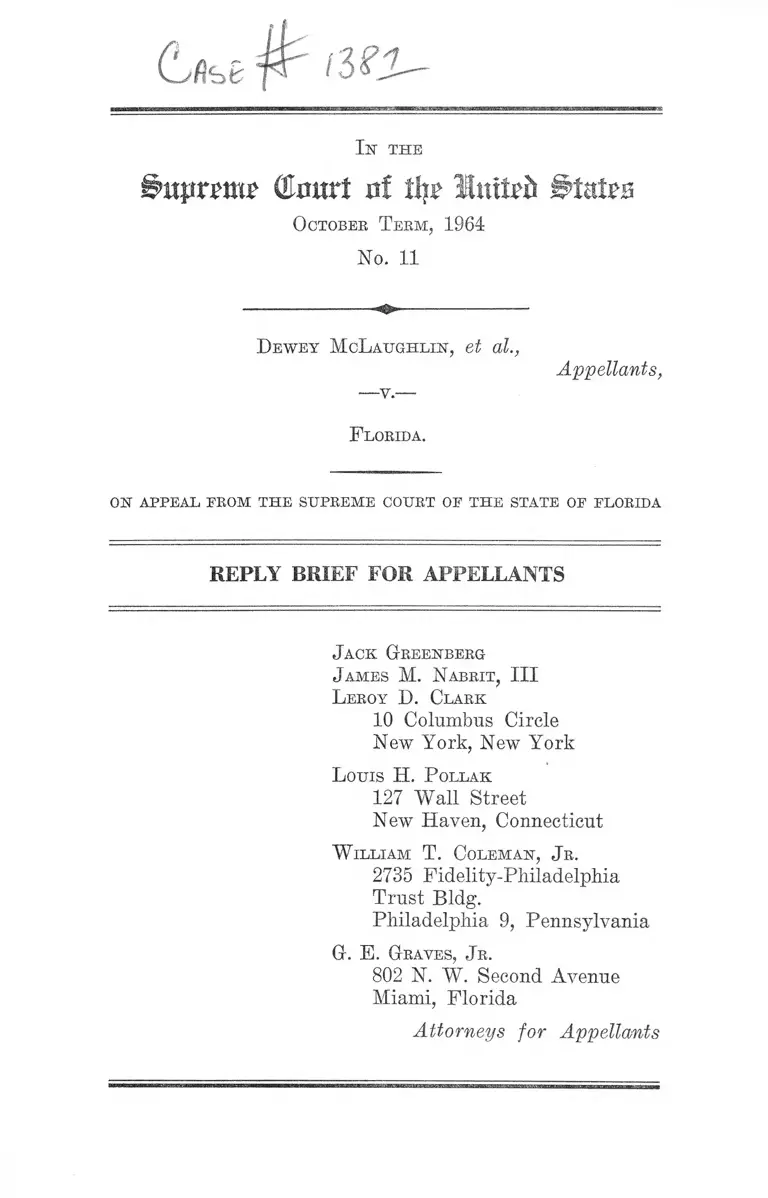

In t h e

i>uprpmr Court of % luttrd Utotrs

October T erm, 1964

No. 11

Dewey McLaughlin, et al.,

Appellants,

F lorida.

ON APPEAL PROM THE SUPREME COURT OP THE STATE OP FLORIDA

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Leroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

L ouis H. P ollak

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

W illiam T. Coleman, Jr.

2735 Fidelity-Philadelphia

Trust Bldg.

Philadelphia 9, Pennsylvania

G. E. Graves, Jr.

802 N. W. Second Avenue

Miami, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ........... 3

Burnette v. State, 157 So. 2d 65 ................................... 15

Forceier v. State, 133 So. 2d 336 ................................... 15

dominion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339 ........................... 3

Hamilton v. State, 152 So. 2d 793 ............................... 15

Henderson v. State, 20 So. 2d 649 ...... 17

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 IT. S. 337 ....... 3

Nixon v. Condon, 286 H. S. 73 ....................................... 3

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ....................................... 3

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ................... 3

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 ............................... 18

Statutes

Civil Bights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 2 7 ...................2, 3, 4,12,19

Fla. Stat. Ann. §924.32 (1) .......................................14,15,16

Fla. Stat. Ann. §918.10 ...................................................... 13

Other A uthorities

Bickel, “ The Least Dangerous Branch” ...........................

Bickel, “ The Original Understanding and the Seg

regation Decision, 69 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1955) ...........

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong. 1st Sess............-........................

2 Florida Jurisprudence (1963) ........ ........ -................ T

In the

§>itpr?m£ GImtrt nf tty United States

October T erm, 1964

No. 11

Dewey McLaughlin, et al.,

—v.-

Appellants,

F lorida.

ON APPEAL PROM THE SUPREME COURT OE THE STATE OE FLORIDA

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

The purpose of this reply brief is to respond to two

questions posed by appellee in its brief: the first of these

is “Whether the Fourteenth Amendment affects the state

anti-miscegenation statutes” ; the second of these is

“ Whether the question of the constitutional validity of state

anti-miscegenation laws is present in the instant case.”

I. “ Whether the Fourteenth Amendment affects the state

anti-miscegenation s t a t u t e s In pages 10-37 of appellee’s

brief the argument is thought to be made that the legislative

history of the Fourteenth Amendment precludes the ap

plication of the Amendment to state anti-miscegenation

laws. Specifically, appellee claims to have demonstrated

(Brief of Appellee, pp. 35-36):

that the purpose of the Amendment was to validate

— the provisions of the Civil Rights Act [of 1866] and

place them beyond the power of the Judiciary to nul

lify, and the power of the Congress to repeal.

It was the opinion of those who spoke in behalf of

the Civil Rights Act that it had no application to mar

riage contracts, anti-miscegenation statutes or the right

of suffrage.

2

In short, appellee’s argument advances in two steps:

(1) that, the Civil Eights Act of 1866 (which appears as

Appendix A, infra) was understood to have no impact on

anti-miscegenation statutes, and (2) that Section 1 of

the Fourteenth Amendment, was understood to be cotermi

nous with the Civil Eights Act of 1866.

Appellants acknowledge the force of the first proposition.

But appellants take strong issue with the second proposi

tion.

The simplest way to test the second proposition—under

which appellee would precisely equate the guarantees of the

Civil Eights Act of 1866 and those of Section 1 of the Four

teenth Amendment—is to inquire whether or not there are

other forms of state-ordained racial discrimination which,

like anti-miscegenation statutes, are plainly outside the

ambit of the Civil Eights Act but which have been declared

by this Court to be proscribed by the Amendment.

To make this test it would be appropriate to refer to

the speech made by Congressman James F. Wilson of Iowa,

manager of the Civil Eights bill in the House, when he

brought the bill up for discussion on March 1, 1866. Con

gressman Wilson had this to say of Section 1 of the bill as

it was originally proposed (Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st

Sess. 1117):

This part of the bill . . . provides for the equality of

citizens of the United States in the enjoyment of “ civil

rights and immunities.” What do these terms mean!

Do they mean that in all things civil, social, political,

all citizens without distinction of race or color, shall

be equal? By no means can they be so construed. Do

they mean that all citizens shall vote in the several

states? No. . . . Nor do they mean that all citizens

shall sit on the juries, or that their children shall

attend the same schools.

3

As the March debates wore on the wording of the bill was

somewhat altered; but its substantial meaning, in the re

spects already noted by Congressman Wilson, did not

change. On the last day of the House debate Congressman

Wilson, speaking of the bill as it was finally enacted into

law, again reiterated its limited impact (id. at 1294-95):

My friend . . . knows, as every man knows, that this

bill refers to those rights which belong to men as

citizens of the United States and none other; and when

he talks of setting aside the school laws and jury laws

and franchise laws of the States by the bill . . . he

steps beyond what he must know to be the rule of con

struction which must apply here, and as a result of

which this bill can only relate to matters within the

control of Congress.

Thus, as authoritatively expounded, the Civil Eights Act

of 1866 was not to “mean that all citizens shall vote in the

several States,” nor “ that all citizens shall sit on the juries,

or that their children shall attend the same schools.” For

the Act would not have the effect “ of setting aside the

school laws and jury laws and franchise laws of the States.

. . . ” However, and this is the decisive point, Section 1 of

the Fourteenth Amendment, which appellee seeks to equate

exactly with the Civil Rights Act of 1866, has operated to

set aside “ the school laws” (Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Can

ada, 305 IT. S. 337; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483) and “ jury laws” (Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S.

303), and “ franchise laws” (Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S.

536; Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73; cf. Gomillion v. Light-

foot, 364 U. S. 339, 349 [concurring opinion of Whittaker,

J .] ) “ of the States-----”

In short, this Court has for decades applied the Four

teenth Amendment to problems of discrimination which

4

were manifestly outside the ambit of the Civil Eights Act

of 1866. And so appellee’s attempt to equate the limited

and particularistic guarantees of the Civil Eights Act with

the spacious rights enshrined in the Fourteenth Amendment

must fail—unless, of course, the legislative history of

the Amendment, properly understood, leads to the con

clusion that this Court fell into fundamental error in each

of these historic interpretations of the Amendment,

But the legislative history of the Amendment, properly

understood, yields no such conclusion. The definitive study

of that history is, of course, the article published by Pro

fessor Alexander M. Bickel in November, 1955, entitled

“ The Original Understanding and the Segregation Deci

sion,” 69 Harv. L. Rev. 1. In his “ Summary and Conclu

sion,” Professor Bickel traces the limited goals of the

abortive Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and the ultimately enacted

Civil Eights Act. Then he states the case for the oft-as

serted equation—repeated in the Brief of Appellee— of the

Civil Eights Act with the Fourteenth Amendment. And

then he shows why the attempt to tie the generalized provi

sions of the Amendment to the particularized provisions

of the statute will not hold water. So cogent is Professor

Bickel’s analysis of this massive problem of constitutional

interpretation that appellants take the liberty of quoting

here some extended excerpts from the closing pages of

Professor Bickel’s article (69 Harv. L. Rev. at 56-65 [foot

notes not included]) :

As we have seen, the first approach made by the 39th

Congress toward dealing with racial discrimination

turned on the “civil rights” formula. The Senate

Moderates, led by Trumbull and Fessenden, who spon

sored this formula, assigned a limited and well-defined

meaning to it. In their view it covered the right to con

tract, sue, give evidence in court, and inherit, hold,

and dispose of real and personal property; also a right

to equal protection in the literal sense of benefiting

equally from laws for the security of person and prop

erty, including presumably laws permitting ownership

of firearms, and to equality in the penalties and burdens

provided by law. Certainly able men such as Trumbull

and Fessenden realized that each of the seemingly

well-bounded rights they enumerated carried about it,

like an upper atmosphere, an area in which its force

was uncertain. Thus it is clear that the Moderates

wished also to protect rights of free movement, and a

right to engage in occupations of one’s choice. They

doubtless considered that their enumeration somehow

accomplished this purpose. Similarly, the Moderates

often argued that one of the imperative needs of the

time was to educate, to “ elevate,” to “ Christianize”

the Negro; indeed, this was almost universally-held

doctrine, from which even Conservatives like Cowan

and Democrats like Rogers did not dissent. Hence one

may surmise that the Moderates believed they were

guaranteeing a right to equal benefits from state edu

cational systems supported by general tax funds. But

there is no evidence whatever showing that for its

sponsors the civil rights formula had anything to do

with unsegregated public schools; Wilson, its sponsor

in the House, specifically disclaimed any such notion.

Similarly, it is plain that the Moderates did not intend

to confer any right of intermarriage, the right to sit

on juries, or the right to vote.

The Civil Rights Bill itself, as brought from the

Senate to the House, split the alliance of various shades

of Moderates and Radicals which constituted the Re

publican majority. The bill was presented to the House

as a measure of limited objectives, following Trum-

6

bull’s views. But a substantial number of Republicans

were troubled by the issue of constitutionality. Others

were uneasy on policy grounds about the reach of sec

tion I, but inclined to believe that the bill could be

rendered constitutional by amendment, and, in any

event, out of mixed motives at which one can only guess,

conquered their apprehensions and voted for it in the

end. Bingham, whose position was in this instance en

tirely self-consistent, thought the bill incurably un

constitutional, its enforcement provisions monstrous,

and the civil rights guaranty of very broad application

and unwise. The concession these Republicans wrung

from the leadership was the elimination of the civil

rights formula and thus the avoidance of possible

“ latitudinarian” construction. The Moderate position

that the bill dealt only with a distinct and limited set of

rights was conclusively validated.

Against this backdrop, the Joint Committee on Re

construction began framing the fourteenth amendment.

In drafting section I, it vacillated between the civil

rights formula and language proposed by Bingham,

finally adopting the latter. Stevens’ speech opening

debate on the amendment in the House presented sec

tion I in terms quite similar to the Moderate position

on the Civil Rights Bill, though there was a rather

notable absence of the disclaimers of wider coverage

which usually accompanied the Moderates’ statements

of objectives. A few remarks made in the Senate

sounded in the same vein. For the rest, however, sec

tion I was not really debated. Rogers, whose remarks

are always subject to heavy discount, considering his

shaky position in the affections of his own party col

leagues, raised “ latitudinarian” alarms. One or two

other Democrats in the House did so also. But more

and more, debate turned on section 3 and not much

else. The focus of attention is well indicated by Stevens’

7

brief address immediately before the first vote in the

House. In this atmosphere, section 1 became the sub

ject of a stock generalization: it was dismissed as em

bodying and, in one sense for the Republicans, in an

other for the Democrats and Conservatives, “ constitu

tionalizing” the Civil Rights Act.

The obvious conclusion to which the evidence, thus

summarized, easily leads is that section 1 of the

fourteenth amendment, like section 1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866, carried out the relatively nar

row objectives of the Moderates, and hence, as origi

nally understood, was meant to apply neither to jury

service, nor suffrage, nor antimiscegenation statutes,

nor segregation. . . .

I f the fourteenth amendment were a statute, a court

might very well hold, on the basis of what has been said

so far, that it was foreclosed from applying it to segre

gation in public schools. The evidence of congressional

purpose is as clear as such evidence is likely to be, and

no language barrier stands in the way of construing the

section in conformity with it. Rut we are dealing with a

constitutional amendment, not a statute. The tradition

of a broadly worded organic law not frequently or

lightly amended was well-established by 1866, and, de

spite the somewhat revolutionary fervor with which the

Radicals were pressing their changes, it cannot be as

sumed that they or anyone else expected or wished the

future role of the Constitution in the scheme of Ameri

can government to differ from the past. Should not the

search for congressional purpose, therefore, properly

be twofold? One inquiry should be directed at the con

gressional understanding of the immediate effect of the

enactment on conditions then present. Another should

aim to discover what if any thought was given to the

long-range effect, under future circumstances, of pro

visions necessarily intended for permanence.

8

That the Court saw the need for two such inquiries with

respect to the original understanding on segregation is

clearly indicated by the questions it propounded at the 1952

Term. The Court asked first whether Congress and the

state legislatures contemplated that the fourteenth amend

ment would abolish segregation in public schools. It next

asked whether, assuming that the immediate abolition of

segregation was not contemplated, the framers neverthe

less understood that Congress acting under section 5, or

the Court in the exercise of the judicial function would, in

light of future conditions, have power to abolish segre

gation.

With this double aspect of the inquiry in mind, certain

other features of the legislative history—not inconsistent

with the conclusion earlier stated, but complementary to it—•

became significant. Thus, section 1 of the fourteenth amend

ment, on its face, deals not only with racial discrimination,

but also with discrimination whether or not based on color.

This cannot have been accidental, since the alternative con

sidered by the Joint Committee, the civil rights formula,

did apply only to racial discrimination. Everyone’s imme

diate preoccupation in the 39th Congress—insofar as it did

not go to partisan questions—was, of course, with hardships

being visited on the colored race. Yet the fact that the

proposed constitutional amendment was couched in more

general terms could not have escaped those who voted for

it. And this feature of it could not have been deemed to be

included in the standard identification of section 1 with

the Civil Rights Act. Again, when it rejected the civil

rights formula in reporting out the abortive Bingham

amendment, the Joint Committee elected to submit an equal

protection clause limited to the rights of life, liberty, and

9

property, supplemented by a necessary and proper clause.

Now the choice was in favor of a due process clause lim

ited the way the equal protection clause had been in the

earlier draft, but of an equal protection clause not so lim

ited: equal protection “ of the laws.” Presumably the lesson

taught by the defeat of the Bingham amendment had been

learned. Congress was not to have unlimited discretion, and

it was not to have the leeway represented by “ necessary and

proper” power. One would have to assume a lack of fa

miliarity with the English language to conclude that a fur

ther difference between the Bingham amendment and the

new proposal was not also perceived, namely, the difference

between equal protection in the rights of life, liberty, and

property, a phrase which so aptly evoked the evils upper

most in men’s minds at the time, and equal protection of

the laws, a clause which is plainly capable of being applied

to all subjects of state legislation... .

These bits and pieces of additional evidence do not contra

dict and could not in any event override the direct proof

showing the specific evils at which the great body of con

gressional opinion thought it was striking. But perhaps

they provide sufficient basis for the formulation of an addi

tional hypothesis. It remains true that an explicit provi

sion going further than the Civil Bights Act could not

have been carried in the 39th Congress; also that a plenary

grant of legislative power such as the Bingham amendment

would not have mustered the necessary majority. But may

it not be that the Moderates and the Radicals reached a

compromise permitting them to go to the country with

language which they could, where necessary, defend against

damaging alarms raised by the opposition, but which at the

same time was sufficiently elastic to permit reasonable

future advances ? This is thoroughly consistent with rejec

tion of the civil rights formula and its implications. That

formula could not serve the purpose of such a compromise.

10

It had been under heavy attack at this session, and among

those who had expressed fears concerning its reach were

Republicans who would have to go forth and stand on the

platform of the fourteenth amendment. Bingham, of course,

was one of these men, and he could not be required to go

on the hustings and risk being made to eat his own words.

If the party was to unite behind a compromise which con

sisted neither of an exclusive listing of a limited series

of rights, nor of a formulation dangerously vulnerable to

attacks pandering to the prejudices of the people, new lan

guage had to be found. Bingham himself supplied it. It

had both sweep and the appearance of a careful enumera

tion of rights, and it had a ring to echo in the national

memory of libertarian beginnings. To put it another way,

the Moderates, with a bit of timely assistance from Fessen

den’s varioloid, consolidated the victory they had achieved

in the Civil Rights Act debate. They could go forth and

honestly defend themselves against charges that on the

day after ratification Negroes were going to become white

men’s “ social equals,” marry their daughters, vote in their

elections, sit on their juries, and attend schools with their

children. The Radicals (though they had to compromise

once more on section 3) obtained what early in the session

had seemed a very uncertain prize indeed: a firm alliance,

under Radical leadership, with the Moderates in the strug

gle against the President, and thus a good, clear chance

at increasing and prolonging their political power. In the

future, the Radicals could, in one way or another, put

through such further civil rights provisions as they thought

the country would take, without being subject to the sort

of effective constitutional objections which haunted them

when they were forced to operate under the thirteenth

amendment.. . .

It is such a reading as this of the original understanding,

in response to the second of the questions propounded by

11

the Court, that the Chief Justice must have had in mind

when he termed the materials “ inconclusive.” For up to this

point they tell a clear story and are anything but incon

clusive. From this point on the word is apt, since the

interpretation of the evidence just set out comes only to

this, that the question of giving greater protection than was

extended by the Civil Rights Act was deferred, was left

open, to be decided another day under a constitutional

provision with more scope than the unserviceable thirteenth

amendment. Some no doubt felt more certain than others

that the new amendment would make possible further

strides toward the ideal of equality. That remained to be

decided, and there is no indication of the way in which

anyone thought the decision would go on any specific issue.

It depended a good deal on the trend in public opinion.

Actually, one of the things the Radicals had contended for

throughout the session, and doubtless considered that they

gained by the final compromise, was time and the chance

to educate the public. Such expectations as the Radicals

had were centered quite clearly on legislative action. At

least this holds true for Stevens. These men were aware

of the power the Court could exercise. They were for the

most part bitterly aware of it, having long fought such

decisions as the Dred Scott case. Most probably they had

little hope that the Court would play a role in furthering

their long-range objectives. But the relevant point is that

the Radical leadership succeeded in obtaining a provision

whose future effect Avas left to future determination. The

fact that they themselves expected such a future deter

mination to be made in Congress is not controlling. It

merely reflects their estimate that men of their view were

more likely to prevail in the legislature than in other

branches of the government. It indicates no judgment

about the powers and functions properly to be exercised by

the other branches.

12

Had the Court in the Segregation Cases stopped

short of the inconclusive answer to the second of its

questions handed down at the previous term, it would

have been faced with one of two unfortunate choices.

It could have deemed itself bound by the legislative

history showing the immediate objectives to which sec

tion I of the fourteenth amendment was addressed, and

rather clearly demonstrating that it was not expected

in 1866 to apply to segregation. The Court would in

that event also have repudiated much of the provision’s

“ line of growth.” For it is as clear that section I was

not deemed in 1866 to deal with jury service and other

matters “ implicit in . . . ordered liberty” to which the

Court has since applied it. Secondly, the Court could

have faced the embarrassment of going counter to what

it took to be the original understanding, and of formu

lating, as it has not often needed to do in the past, an

explicit theory rationalizing such a course. The Court,

of course, made neither choice. It was able to avoid the

dilemma because the record of history, properly under

stood, left the way open to, in fact invited, a decision

based on the moral and material state of the nation in

1954, not 1866.

The present relevance of Professor Bickel’s masterly

study is abundantly clear: The Civil Rights Act of 1886

was not intended to apply to laws excluding Negroes from

juries or from the franchise, denying them admission to

public schools or relegating them to segregated schools,

or forbidding them to marry their white fellow-citizens.

But this Court has found— and properly so—that racial

discriminations in jury service, the franchise, and public

schools are all proscribed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The instant case calls for the application of the Amend

ment to antimiscegenation statutes. And, as Professor

Bickel pointed out only two years ago, “ the constitutionality

of antimiscegenation statutes . . . would surely seem to be

13

governed by the principle of the Segregation Cases. . . . ”

Bickel, The Least Dangerous Branch, p. 71.

II. “ Whether the Question of the Constitutional Validity

of State Anti-Miscegenation Laivs Is Present in the Instant

Case.” Appellants do not propose, in this reply brief, to

devote further attention to the question whether there was

testimony on the basis of which the jury could have con

cluded—had the trial judge’s instruction not taken the issue

out of the case—that appellants had contracted a common

law marriage. Although opinions may differ as to how com

pelling the relevant testimony was, appellee’s own brief

makes it plain that a juror hearing the testimony of Mrs.

Goodniek and Mrs. Kaabe might reasonably have concluded

that appellants were married— or that, at the very least,

the prosecution had not proved the non-existence of a matri

monial relationship beyond a reasonable doubt.

What appellants wish briefly to address themselves to

is appellee’s ambiguous intimation that the constitutional

correctness of the trial judge’s instruction ruling out the

issue of common law marriage is not properly before this

Court.

Appellee’s intimation to this effect appears at pages 52

to 53 of its brief. Appellee there relies on Section 918.10

of the Florida Statutes for the suggestion that the validity

of the instruction was not before the Florida Supreme

Court (and hence is not before this Court) because it had

not been expressly challenged “before the jury retire [d]

to consider its verdict.”

The ambiguity of appellee’s intimation arises from appel

lee’s apparent contrary concession on page 6 of its brief:

14

Appropriate appeal was taken to the Florida Su

preme Court (R. 1). Suck appeal initially raised all

errors presently submitted to this Court (R. 12); how

ever, in briefing the questions and in petitioning for

rehearing, the appellants abandoned their position that

the statute under which they were prosecuted was vague

and indefinite (R. 103). (See also appendix “ A ” to

appellee’s brief wherein there is contained a photo

static copy of the only brief presented to the Florida

Supreme Court by the appellants.)

In short, appellee there acknowledges that all the ques

tions now urged by appellants were properly raised by an

“ appropriate appeal” . And the only one of those questions

said to have fallen by the wayside at a later stage was the

vagueness problem, and that only by non-inclusion in the

brief and the petition for rehearing. Moreover, the brief

filed by appellants in the Florida Supreme Court—which

appellee has added as an appendix to its brief in this Court

— argued the invalidity of the instruction at length (Brief

of Appellee, Appendix A pages 13-17). Finally, it may be

noted that in opposing appellant’s petition for rehearing in

the Florida Supreme Court, appellee expressly urged that

Court to rule that the validity of the challenged instruction

was not properly before it— and the Florida Supreme Court

denied rehearing without opinion.

If, nevertheless, appellee is to be understood as still urg

ing that Section 918.10 of the Florida Statutes does bar

consideration of the challenged instruction—and hence of

the anti-miscegenation statutory and constitutional provi

sions on which it rests—it then seems appropriate to point

out that Section 918.10 does not stand alone:

Section 924.32 (1) of the Florida Statutes provides as

follows:

15

Upon an appeal by either the State or the defendant

the appellate court shall review all rulings and orders

appearing in the appeal papers insofar as it is neces

sary to do so in order to pass upon the grounds of

appeal. The court shall also review all instructions to

which an objection was made and which are alleged as a

ground of appeal, and the sentence where there is an

appeal therefrom. The court may also in its discretion,

if it deems the interests of justice to require, review

any other thing said or done in the cause which appears

in the appeal papers including instructions to the jury.

The reception of evidence to which no objection was

made shall not be construed to constitute a ruling by

the court.

The discretionary authority conferred on an appellate

court by the last-quoted statutory provision has recently

been commented on by the Florida Supreme Court in Bur

nette v. State, 157 So. 2d 65, 67, and by the Florida District

Court of Appeal in Hamilton v. State, 152 So. 2d 793, 795

and in Forceier v. State, 133 So. 2d 336, 337. The way in

which this discretion is utilized by the Florida courts is

indicated by the following commentary appearing in the

section on “ Appeals” in volume 2 of Florida Jurisprudence

(1963) pp. 422-23 (footnotes omitted):

The giving of instructions is subject to the rule that

while timely objection should be made, errors of the

trial court in this regard may be reviewed on appeal in

the absence of an objection if the error is so funda

mental as to justify such action, or when the appellate

court, in its discretion, deems the interests of justice

to so require. Whether the omission of the court to

instruct on a particular point will be regarded as funda

mental depends on the evidence in the case and the seri

16

ousness of the charge involved. Thus, the failure to

instruct the jury on the weight to be given a confes

sion in a capital case, where the conviction rests pri

marily on that confession, may justify reversal though

no objection was interposed thereto. On the other hand,

the failure to give such an instruction in an armed

robbery case, where there is evidence other than the

confession in support of the conviction, will not compel

a reversal if no objection thereto was raised at the

trial. But where the instructions given by the court

erroneously take from the jury an essential element of

the crime charged by the prosecution, the error is so

fundamental that the conviction should be reversed even

though no objection was made at the time they were

given.

Appellants submit that the instant case exactly fits within

the last sentence of the quoted paragraph from Florida

Jurisprudence. For the trial court’s instruction removing

the common law marriage issue from the jury’s considera

tion followed immediately after the trial court had in

structed the jury that it was incumbent on the State to

prove, inter alia, “ that defendants were not married to

each other at the time of the alleged offense” (R. 93).

Thus, if, as appellants contend, the instruction excluding

the common law marriage issue rested upon the unconstitu

tional premise that Florida’s anti-miscegenation laws were

valid, the present case is exactly one in which “ the Court

erroneously [took] from the jury an essential element of

the crime charged by the prosecution . . . ” In such a situa

tion Section 924.32 (1) makes it at least proper for a Florida

appellate court to review the challenged instruction without

regard for whether it was specifically objected to before

17

the jury retired to consider its verdict. Indeed it may well

be incumbent upon a Florida appellate court to exercise

this revisory authority where the trial judge’s intrusion

upon the jury’s domain is as flagrant as it was in the in

stant case. This may be the teaching of the Florida Su

preme Court in the case of Henderson v. State, 20 So. 2d

649, 651:

This instruction invaded the province of the jury to

the extent of taking from it the determination of every

element of the offense charged except that of the in

tent of the accused. It is elementary that every element

of a criminal offense must be proved sufficiently to

satisfy the jury (not the court) of its existence.

It is contended by the State that while the charge

supra is clearly erroneous, the error is waived by rea

son of the provisions of . . . subparagraph 4, Sec.

918.10, Florida Statutes 1941, same F. S. A.

We cannot agree with this view. We must bear in

mind the due process clause of both our State and Fed

eral Constitutions. We are convinced that due process

of law contemplates trial in a criminal ease by a fair

jury, with full evidence and correct charges or instruc

tions to the jury as to the law. Of these elements of

fundamental safeguard, an accused may not be deprived

either by statute or rule of court. See Lawson v. State,

125 Fla. 335, 169 So. 739, and cases there cited.

When the provisions of statutes collide with provi

sions of the Constitution the statute must give way.

At all events, whether or not it would have been incum

bent on a Florida appellate court to review so crucial an

instruction, even though not objected to, it is manifest from

18

the foregoing discussion that a Florida appellate court

has ample discretionary authority to review the instruction

in such an instance. Cf. Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

L eroy I). Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Louis H. P ollak

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

W illiam T. Coleman, J r.

2735 Fidelity-Philadelphia

Trust Bldg.

Philadelphia 9, Pennsylvania

G. E. Graves, J r .

802 N. W. Second Avenue

Miami, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX A

Civil E ights A ct of 1868

14 Stat. 27

Chap. X X X I.—An Act to protect all Persons in the United

States in their Civil Eights, and furnish the

Means of their Vindication.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Eepresenta-

tives of the United States of America in Congress as

sembled, That all persons born in the United States and

not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not

taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United

States; and such citizens, of every race and color, without

regard to any previous condition of slavery or involuntary

servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the

party shall have been duly convicted, shall have the same

right, in every State and Territory in the United States,

to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give

evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey

real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of

all laws and proceedings for the security of person and

property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be sub

ject to like punishment, pains, and penalties, and to none

other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom,

to the contrary notwithstanding.

Sec. 2. And be it further enacted, That any person who,

under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or

custom, shall subject, or cause to be subjected, an}̂ inhabi

tant of any State or Territory to the deprivation of any

right secured or protected by this act, or to different pun

ishment, pains, or penalties on account of such person

having at any time been held in a condition of slavery or

2a

involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime

whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, or by

reason of his color or race, than is prescribed for the pun

ishment of white persons, shall be deemed guilty of a mis

demeanor, and, on conviction, shall be punished by fine not

exceeding one thousand dollars, or imprisonment not ex

ceeding one year, or both, in the discretion of the court. . . .

rs

38