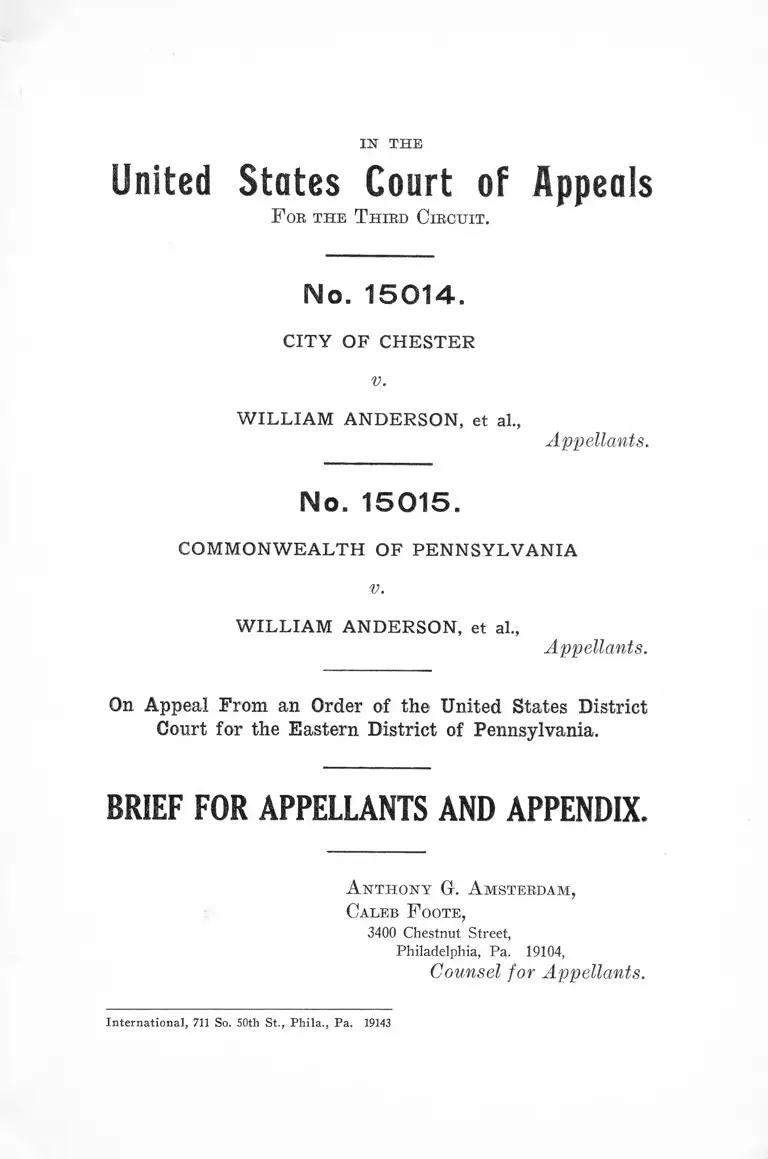

City of Chester v. Anderson Brief for Appellants and Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Chester v. Anderson Brief for Appellants and Appendix, 1964. f8486061-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/44aed0a9-d7f5-446d-919f-a239dc5fa5af/city-of-chester-v-anderson-brief-for-appellants-and-appendix. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

United S ta te s Court o f Appeals

F o r t h e T h i r d C i r c u i t .

No. 15014.

CITY OF CHESTER

V.

W ILLIA M ANDERSON, et al.,

Appellants.

No. 15015.

COM M ONW EALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

v.

W ILLIA M ANDERSON, et al.,

Appellants.

On Appeal From an Order of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS AND APPENDIX.

A n t h o n y G . A m s t e r d a m ,

C a l e b F o o t e ,

3400 Chestnut Street,

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104,

Counsel for Appellants.

International, 711 So. 50th St., Phila., Pa. 19143

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF APPELLANTS’ BRIEF.

Page

Q U E ST IO N IN V O L V E D .................................................................................... 1

S T A T E M E N T O F T H E C A S E .......................................................................... 2

(A ) The Removal Proceedings Generally ................................................ 2

(B ) Appeal Nos. 1S014 and 15015 ............................................................... 5

A R G U M E N T ............................................................................. 11

(A ) Introduction ................................................................................................ 11

(1 ) Summary ...................................................................................... 11

(2 ) The removal statute and its history ..................................... 12

(B ) Defendants’ Removal Petitions Sufficiently State a Removable

Case under 28 U. S. C. § 1443(2) .................................................. 20

(1 ) “ Color of authority” .................................................................. 22

(2 ) “Law providing for equal rights” ......................................... 29

(3 ) The acts for which defendants are prosecuted .................. 32

(C ) Defendants’ Removal Petitions Also State a Removable Case

under 28 U. S. C. § 1443(1) by Reason of Unconstitutionality

of the Underlying Criminal Charges ........................................... 33

(D ) Defendants’ Removal Petitions Further State a Removable Case

under 28 U. S. C. § 1443(1) Because the Very Pendency of

These Prosecutions in the State Courts is Calculated to Sup

press Their First Amendment Rights ....................................... 39

(E ) This Court Has Jurisdiction to Review the Remand Order . . . . 42

CO N CLU SIO N ........................................................................................................... 46

TABLE OF CITATIONS.

Cases.

Page

Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Supp. 626 (E . D. Ark. 1963) ........................... 21

Babbitt v. Clark, 103 U. S. 606 (1880) .............................................................. 45

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964) .............................................................. 40

Baines v. Danville, 4th Cir., Nos. 9080-9084, 9149, 9150, 9212 ( 8 /10/64) . . . 39

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963) ..................................... 40

Birmingham v. Croskey, 217 F. Supp. 947 (N . D. Ala. 1963) ....................... 39

Blyew v. United States, 13 Wall. 581 (1871) ................................................... 18

Bowles v. Strickland, 151 F. 2d 419 (5th Cir. 1945) ....................................... 43

Braun v. Sauerwein, 10 Wall. 218 (1869) ........................................................... 21

Brown (Addie Sue) v. City of Meridian, 5th Cir., No. 21730 ( 7/23/64) ..38,39

Bruner v. United States, 343 U. S. 112 (1952) ................................................. 43

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110 (1882) ............................................................ 34

Commonwealth v. Albert, 169 Pa. Super. 318, 82 A. 2d 695 (1951) ............ 3

Commonwealth v. Mack, 111 Pa. Super. 494, 170 Atl. 429 (1934) ............... 3,6

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S. 278 (1961) ......................... 40

Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943) ....................................................... 31

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) ......................................... 33

Egan v. Aurora, 365 U. S. 514 (1961) .............................................................. 31

Employers Reinsurance Corp. v. Bryant, 299 U. S. 374 (1937) .................. 45

England v. Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners, 375 U. S. 411

(1964) .................................................................................................... .. 17

E x parte Collett, 337 U. S. 55 (1949) ................................................................. 43

E x parte United States, 287 U. S. 241 (1932) .................................... 45

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 (1963) ........................................................................14,17

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951) ....................................................... 41

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963) ..................................................... 33

Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U. S. 67 (1953) ..................................................... 30

Gay v. Ruff, 292 U. S. 25 (1934) .......................................................................... 45

Georgia v. Tuttle, 84 S. Ct. 1940 (1964) ..................................................... 39,43,44

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 (1896) .......................................... 34,38

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 (1939) ................................. 30,31

Harris v. Gibson, 322 F. 2d 780 ( 5th Cir. 1963) .................... 45

Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964) ...................................... 33

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 (1937) ........................................................... 36

Cases (Continued).

Page

Hill v. Pennsylvania, 183 F. Supp. 126 (W . D. Pa. 1960) ............................. 30

Hoadley v. San Francisco, 94 U. S. 4 (1876) ...................... ..........................43,45

Hodgson v. Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. 285, No. 6,568 (Grier, C. J., E. D. Pa.

1863) ....................................................................................................................... 21

Hodgson v. Millward, 3 Grant (P a .) 412 (Strong, J., at nisi prius, 1863) 21

In re Pennsylvania Co., 137 U. S. 451 (1890) ................................................. 45

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906) ........ ...................................... 34, 37, 38, 39

La Buy v. Howes Leather Co., 352 U. S. 249 (1957) ....................................... 45

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 (1939) .............................................. 36

Local No. 438 v. Curry, 371 U. S. 542 (1963) .............................................. 44

Logemann v. Stock, 81 F. Supp. 337 (D . Neb. 1949) ..................................... 21

McClellan v. Carland, 217 U. S. 268 (1910) ..................................................... 45

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 (1963) ................................. 17

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946) ......................................................... 39

Missouri Pacific Ry. Co. v. Fitzgerald, 160 U. S. 556 (1896) ...................... 45

Mercantile National Bank v. Langdeau, 371 U. S. 555 (1963) ......................... 44

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961) ........................................................ 17,19,30

Murray v. Louisiana, 163 U. S. 101 (1896) .................................... 34

Musser v. Utah, 333 U. S. 95 (1948) .................................................................... 36

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama ex rel Flowers, 377 U. S. 288 (1964) ............ 30

N. A. A . C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) .....................................30, 36,40, 42

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1880) ............................................................. 38

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254 (1964) ................................. 39

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 (1951) ................................................... 30

North Carolina v. Jackson, 135 F. Supp. 682 (M . D. N. C. 1955) ............ 36

Orr v. United States, 174 F. 2d 577 (2d Cir. 1949) ......................................... 43

Platt v. Minnesota Mining & Mfg. Co., 376 U. S. 240 (1964) ...................... 45

Potts v. Elliott, 61 F. Supp. 378 (E . D. Ky. 1945) .......... 21

Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944) .............................................. 39

Railroad Co. v. Wiswall, 23 Wall. 507 (1874) .............................................. 44,45

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 (1948) ........................................................... 39

Schoen v. Mountain Producers Corp,, 170 F. 2d 707 (3d Cir. 1948) .......... 43

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 (1959) ............................................... ............ 40

Smith v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 592 (1896) ..................................................... 34

Snypp v. Ohio, 70 F. 2d 535 (6th Cir. 1934) ..................................................... 36

State v. Musser, 118 Ut. 537, 223 P. 2d 193 (1950) ......................................... 36

Steele v. Superior Court, 164 F. 2d 781 (9th Cir. 1948) ............................. 30

Strauder v. W est Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1878) ...................................34,36,38

TABLE OF CITATIONS (Continued).

T A B L E O F C IT A T IO N S (Continued).

Cases (Continued).

Page

Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257 (1879) ......................................................... 33

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 (1949) ....................................................... 36

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940) ....................................................... 36

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963) ............................................................ 17

Turner v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 106 U. S. 552 (1882) ...................... 45

United States v. Igoe, 331 F. 2d 766 ( 7th Cir. 1964) ................................... 45

United States v. Rice, 327 U. S. 742 (1946) ....................................................... 45

United States v. Smith, 331 U. S. 469 (1947) ...................................... 45

United States v. W ood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961) ............................ 44

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 (1879) ............................................... 34,37,38,40

Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U. S. 213 (1898) ................................................. 34

Wilson v. Commonwealth, 96 Pa. 56 (1880) ....................................................... 6

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions and Rules.

Page

U. S. Const., Amend. I ............ .................1, 7, 21, 31, 33, 38, 39, 41, 42

u. S. Const., Amend. X III . . . . 16

u. S. Const., Amend. X IV . . . . . . .1 , 7, 16, 31, 34, 38, 39

u. S. Const., Amend. X V ........ . 16

28 U. S. C. § 1257 .................... . 44

28 U. S. C. § 1291 .................... . 44

28 U. S. C. §1331 .................... . 17

28 U. S. C. § 1441 .................... 17

28 u. S. C. §§ 1441-1444 ........ . 13

28 u. S. C. § 1442(a )(1 ) . . . . .22,28

28 u. S. C. § 1443 ...................... 11, 12, 17, 21, 26, 30, 42

28 u. S. C. § 1443(1) .............. . . . .1 , 2, 7, 10, 11, 29, 30, 31, 33, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42

28 u. S. C. § 1443(2) .............. . . . . 1, 2, 7, 10, 11, 20, 21, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 39

28 u. S. C. § 1447(d) .............. .43, 45

28 u. S. C. § 1651 ...................... . 45

28 u. S. C. §2241 ( c ) ( 3 ) ........ . 17

42 u. S. C. § 1983 .................... ...7 ,21,, 30, 31

Rev. Stat. § 641 ................ ......... ..25,26., 29, 31

Rev. Stat. § 1979 .............. ......... .21,30

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions and Rules (Continued).

Page

28 U. S. C. §74 (1940 ed.) ..................................................................................... 26

A ct of September 24, 1789, 1 Stat. 73 .................................................................. 14

Act of February 13, 1801, 2 Stat. 8 9 ...................................................................... 14

A ct of March 8, 1802, 2 Stat. 1 3 2 .......................................................................... 14

A ct of February 4, 1815, 3 Stat. 195 ....................................... .............................. 14, 22

A ct of March 3, 1815, 3 Stat. 231 ...........................................................................14,22

A ct of March 2, 1833, 4 Stat. 632 .................... .....................................................14,22

A ct of March 3, 1863, 12 Stat. 755 ........................................................................ 20,23

A ct of March 7, 1864, 13 Stat. 14 ...........................................................................15,23

A ct of June 30, 1864, 13 Stat. 223 .............................. 15,23

A ct of March 3, 1865, 13 Stat. 507 .........................................................................15,27

A ct of April 9, 1866, 14 Stat. 2 7 ...............................................................................16,24

A ct of May 11, 1866, 14 Stat. 4 6 .............................................................................. 20

A ct of July 13, 1866, 14 Stat. 9 8 .............................................................................15,23

A ct of July 16, 1866, 14 Stat. 173 .......................................................................... 27

A ct of February 5, 1867, 14 Stat. 385 .................................................................... 17

A ct of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140 .....................................................................16,25,29

A ct of April 20, 1871, 17 Stat. 13 .....................................................................16,25,31

A ct of March 1, 1875, 18 Stat. 335 ........................................................................ 16

A ct of March 3, 1875, 18 Stat. 470 ........................................................................ 17

Judicial Code of 1911, 36 Stat. 1087 ...................................................................... 26,44

Civil Rights A ct of 1964, 78 Stat. 241 ................................................................. 43

Fed. Rule Civ. Pro. 81(b ) ...................................................................................... 45

United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, Rule 24(7) ............ 44

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18, §4302 ................................................... 3,6,36

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963 Supp,, tit. 18, § 4314 ............................ 3

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963 Supp., tit. 18, § 4314.1 ........................ 3

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18, § 4401 ........................................ 3

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18, §4404 ................................................... 3 ,5 ,6

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18, § 4 4 1 2 ...................................... 3

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18, § 4612 ........................................ 3

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18, § 4708 ........................................ 3

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18, §4901.1 ................................................. 3,6

Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18, § 4916 ..................................................... 3

Acts of Virginia, 1865-1866, 91 (1866) ............................................................... 19

Ordinance No. 61 of 1962 of the City of Chester, Pennsylvania................... 36

Code of Ordinances of the City of Chester, Pennsylvania (1956), §16-13 2

TABLE OF CITATIONS (Continued).

T A B L E O F C IT A T IO N S (Continued).

Other Sources.

Page

Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 3d Sess............................................................................15-16

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess............................................................................19-21

Revisor’s Note to 28 U. S. C. § 1443 .................................................................... 26

2 Commager, Documents of American History (6th ed. 1958) ..................... 19

III Elliot’s Debates (1836) .................................................................................... 14

I Farrand, Records of the Federal Convention (1911) ................................... 13

The Federalist, No. 80 (Hamilton) ........................................................................13, 14

The Federalist, No. 81 (Hamilton) ........................................................................ 13

1 Fleming, Documentary History of Reconstruction (Photo reprint 1960) 19

Frankfurter & Landis, The Business of the Supreme Court (1928) .......... 16

Hart & Wechsler, The Federal Courts and the Federal System (1953) ..13, 14

McPherson, Political History of the United States During the Period of

Reconstruction (1871) ...................................................................................... 20

1 Morison & Commager, Growth of the American Republic (4th ed. 1950) 14

Note, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) ........................................................................ 42

Brief for Respondents Rachel et al., O. T. 1963, No. 1361 Misc., Georgia

v. Tuttle, 84 S. Ct. 1940 (1964) .................................................................... 43

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF APPELLANTS’ APPENDIX.

Page

Docket Entries ......................................................................................... la

Petition for Removal ................................................................................................ 2a

Motion to Remand ..................................................................... 21a

Answer to Petition for Removal and Motion to Dismiss Said Petition . . . 22a

Excerpt of Hearing, June 30, 1964, on Motion to Remand: Colloquy

between Hon. Thomas J. Clary, C. J., presiding, and counsel for

defendants ............................................................................................................... 29a

Order of Remand ......................................................................................................... 31a

Amended Order ........................................................................................................... 33a

Notice of Appeal ..................................................... 34a

QUESTION INVOLVED.

Did the District Court err in holding that appellants’

petitions for removal of criminal cases pending in Pennsyl

vania state trial courts failed to sustain federal removal

jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. §1443(1), (2) (1958), the

civil rights removal statute, where the petitions alleged

that appellants were being prosecuted for acts in the exer

cise of their constitutionally protected freedom of speech

to protest racial discrimination, that the state statutes

underlying the prosecution were unconstitutional on their

faces or as applied under the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments, and that the purpose and effect of the prosecutions

were to repress constitutionally protected free speech and

protest of racial discrimination?

2 Statement of the Case

S T A T E M E N T O F T H E C A S E .

Defendants (appellants in this Court) are ten of more

than 240 persons arrested in connection with civil rights

demonstrations in Chester, Pennsylvania, in February,

March and April 1964, and thereafter prosecuted by state

and local authorities for demonstration activities. The

demonstrators 1 attempted to remove these prosecutions to

the appropriate federal district court for trial pursuant to

28 U. S. C. § 1443(1), (2) (1958), the civil rights removal

section of the Judicial Code. On motion of the prosecution

the cases were ordered remanded to the state courts for

want of federal removal jurisdiction. These appeals chal

lenge the propriety of the remand order.

(A) The Removal Proceedings Generally.

June 26, 1964, twenty-four petitions were filed in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Pennsylvania, seeking to remove criminal prosecutions

arising out of twelve separate civil rights demonstration

episodes. Demonstrators arrested in each episode were

prosecuted in two sorts of proceedings. Each was sum

marily tried and convicted before a magistrate of the City

of Chester for violation of two Chester ordinances, Ordi

nance No. 61 of 1962 of the City of Chester (disorderly con

duct), set out at App. 13a, and Code of Ordinances of the

City of Chester, Pennsylvania (1956), §16-13 (non-compli

ance with a police order), set out in the note.2 Demon

strators were sentenced to the maximum penalties under

1. As used in this brief, “demonstrator” means a defendant prosecuted for

demonstration activity. When these cases go to trial, numerous of the defend

ants will take the position that they were not demonstrators, but bystanders.

I heir description as demonstrators here portrays the role in which the prose-

cution. seeks to cast them and which is controlling for purposes of removability

of their prosecutions.

2. “ Sec. 16-13. Noncompliance with police order, etc.

“ No person shall refuse or fail to comply with any lawful order signal

or direction of a police officer. (4-23-29, § 2 ; Code 1943, ch. 17, § 2 . ) ”

Statement of the Case 3

each ordinance: $300 fine and $9 costs for disorderly con

duct; $50 fine and $9 costs for non-compliance—a total of

$350 fine plus $18 costs or imprisonment in default. Ap

peals for trial de novo of these summary convictions were

allowed by the Court of Common Pleas of Delaware County

and the cases were pending for trial in the Court of Com

mon Pleas at the time the removal petitions were filed.

(These procedings are sometimes hereafter referred to as

summary appeals.) (App. 2a-3a, 4a-5a.)

Each demonstrator was also indicted on several bills

of indictment returned to the Court of Quarter Sessions

of Delaware County. The offenses charged in the indict

ments differed for the different demonstration episodes.3

These prosecutions were pending in the Court of Quarter

Sessions for trial at the time the removal petitions were

filed. (They are sometimes hereafter referred to as indict

able charges.) (App. 2a, 6a, 9a-10a.)

Most of the 240-odd defendants were charged with of

fenses arising out of only one demonstration episode, some

with offenses arising out of more than one. Two removal

petitions were filed for each of the twelve demonstration

episodes. One sought to remove the summary appeals of

all defendants charged in connection with that episode; the

3. Only the offenses charged against the ten defendants involved in these

appeals (all indicted on charges arising out of a single demonstration epi

sode) appear in the record of the appeals. See pp. 5-6 infra. For the infor

mation of the Court, the records of the District Court in the companion cases

disclose that each of the approximately 240 demonstrators is charged with

between two and seven of the following offenses: Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann.,

1963, tit. 18, §§4302 (conspiracy to do unlawful act), 4401 (riots, routs, assem

blies, and affrays), 4404 (forcible detainer), 4412 (libel), 4612 (public

nuisances), 4901.1 (unlawful entry), 4916 (malicious injury to property), and

common-law conspiracy, citing 111 Super. 494 [Commonwealth v. Mack, 111

Pa. Super. 494, 170 Atl. 429 (1934)], common-law inciting to riot, citing 169

Super. 318 [Commonwealth v. Albert, 169' Pa. Super. 318, 82 A. 2d 695 (1951)],

and common-law nuisance, citing l2 Pa. 412 [? ]. The pattern is to charge

defendants involved in street demonstrations with riot, statutory and common-

law nuisance, and statutory and common-law conspiracy; and to charge defend

ants involved in “sit-ins” in public buildings with forcible detainer, unlawful

entry, statutory and common-law conspiracy, and sometimes riot. There are

also a few indictments for violations of Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18,

§4708 (assault and battery), and Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963 Supp., tit. 18,

§§4314 (obstructing an officer), and 4314.1 (aggravated assault and battery

upon a police officer).

4 Statement of the Case

other, the indictable charges against the same defendants

(App. 2a). The twenty-four removal petitions were

docketed in the District Court as Crim. Nos. 21764 through

21787.

The two petitions constituting each pair relating to a

single demonstration episode were identical save for cap

tion. Thus the removal petition in Crim. No. 21764, City of

Chester v. Anderson et al., was identical with the removal

petition in Crim. No. 21765, Commonwealth of Pennsylva

nia v. Anderson et al., except for the name of the prosecut

ing authority. Each pair of removal petitions differed from

every other pair in describing the demonstration episode

involved, naming the defendants charged, and designating

the indictable charges returned against them. Otherwise

the twenty-four removal petitions were identical (App.

3a).

June 29, 1964 a Motion for Remand was filed by the

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, asking that all the re

moved cases (summary appeals as well as indictable of

fenses) be remanded to the Pennsylvania courts for want

of federal jurisdiction (App. 21a). June 30, 1964 an iden

tical Answer to Petition for Removal and Motion to Dis

miss Said Petition was submitted in each of the twenty-

four removed cases (Filed July 6, 1964, App. 22a). In the

morning of June 30, 1964 these motions by the prosecution

were called for hearing before Chief Judge Clary of the

District Court and argument was had. July 6, 1964 Chief

Judge Clary entered his order reciting that the cases were

improperly removed and granting the motion to remand

all cases (App. 31a). July 7, 1964 Chief Judge Clary

entered an amended order staying the remand “ pending ap

peal to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit, of actions #21764 and #21765, in which cases no

tices of appeal are being filed concurrently with this Order.

Since cases #21766-21787 inclusive involve identical ques

tions of law and fact as cases #21764 and #21765, these

cases shall remain in this Court without remand, pending

Statement of the Case 5

final determination of the appeals in #21764 and #21765,

and until further order of this Court” (App. 33a).

July 7, 1964, notices of appeal were filed in Crim. Nos.

21764 and 21765 (App. 34a). Crim. No. 21764 was there

after docketed in this Court as Appeal No. 15014, and Crim.

No. 21765 as Appeal No. 15015. A consent motion has been

made to consolidate the appeals for purposes of appellants’

brief and appendix.

(B) Appeal Nos. 15014 and 15015.

The two identical removal petitions filed by the ten

criminal defendants in each of these cases alleged the fol

lowing : On February 20, 1964, at about 1 :30 P. M., defend

ants were arrested by Chester policemen at the Chester

School Administration Building. A group of spokesmen

for equal civil rights had arrived at the Administration

Building in order to discuss with authorities the problem

of racial segregation and inequality that exists in the Ches

ter school system. The group was invited to enter and

remain in a room by an employee. The group remained

there for a time and was told to leave. Not having accom

plished their purpose, they refused to go. Police were

called and the defendants were arrested (App. 4a).

The pattern of prosecutions arising out of this episode

was described in the petitions as common to the approxi

mately 240 demonstrators arrested in the twelve demon

stration episodes underlying the twenty-four companion

removal cases (App. 4a-5a). The summary conviction of the

demonstrators for violation of the two Chester ordinances

(disorderly conduct; non-compliance with a police order)

described at p. 2, supra, and the pendency of their sum

mary appeals in the Court of Common Pleas was recited

(App. 4a-5a). It was alleged that additionally the 240-odd

demonstrators were indicted on several state statutory and

common-law charges (App. 6a, 9a-10a); specifically, the ten

defendants herein were charged in four bills with violations

of (1) Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18, § 4404 (forcible

6 Statement of the Case

detainer),4 (2) Pardon’s Pa. Stat. Ann., 1963, tit. 18,

§4901.1 (unlawful entry),5 6 (3) Purdon’s Pa. Stat. Ann.,

1963, tit. 18, § 4302 (conspiracy),8 and (4) common-law con

spiracy.7 It was alleged that the “ acts for which [de

fendants] . . . are being held to answer for offenses

. . . are, insofar as the offenses charged have any basis

4. Ҥ. 4404. Forcible detainer

“ Whoever, by force and with a strong hand, or by menaces or threats,

unlawfully holds and keeps possession of any lands or tenements, whether

the possession was obtained peaceably, or otherwise, is guilty of forcible

detainer, a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof, shall be sentenced

to pay a fine not exceeding five hundred dollars ($500), or to undergo

imprisonment not exceeding one (1 ) year, or both, and to make restitution

of the lands and tenements unlawfully detained.

“ No person shall be adjudged guilty of forcible detainer, if such person,

by himself, or by those under whom he claims, have been in peaceable

possession for three (3 ) years next preceding such alleged forcible detention.

1939, June 24, P. L. 872, § 404.”

5. Ҥ 4901.1. Unlawful entry

“Whoever under circumstances or in a manner not amounting to bur

glary enters a building, or any part thereof, with intent to commit a crime

therein, is guilty of unlawful entry, a misdemeanor, and upon conviction

thereof, shall be sentenced to pay a fine not exceeding five hundred dollars

($500) or to undergo imprisonment not exceeding one year, or both. 1939,

June 24, P. L. 872, § 901.1, added 1959, Nov. 19, P. L. 1518, No. 532, § 1.”

6. Ҥ 4302. Conspiracy to do unlawful act

“Any two or more persons who falsely and maliciously conspire and

agree to cheat and defraud any person of his moneys, goods, chattels, or

other property, or do any other dishonest, malicious, or unlawful act to the

prejudice of another, are guilty of conspiracy, a misdemeanor, and on con

viction, shall be sentenced to pay a fine not exceeding five hundred dollars

($500), or to undergo imprisonment, by separate or solitary confinement

at labor or by simple imprisonment, not exceeding two (2 ) years, or both.

1939, June 24, P. L. 872, § 302.”

7. The indictment cites 111 Super. 494. The citation refers to Common

wealth v. Mack, 111 Pa. Super. 494, 170 Atl. 429 (1934), sustaining common-

law conspiracy convictions of defendants shown to have made wilfully false

criminal charges against other persons. The court quotes Wilson v. Common

wealth, 96 Pa. 56, 59 (1880) : “ ‘A conspiracy at common law is a much broader

offense [than statutory conspiracy, see note 6 supra], and embraces cases where

two or more persons combine, confederate and agree together to do an unlawful

act, or to do a lawful act by the use of unlawful means.’ ” I l l Pa. Super, at

497, 170 Atl. at 430. “Unlawful” in this context does not mean criminal, i.e.,

denounced by a specific criminal statute, 111 Pa. Super, at 498, 170 Atl. at

430-431. The court says: “ In the case of Com. v. Carlisle, Brightly’s Rep. 36,

39, Mr. Justice Gibson pointed out the difficulties in defining the exact limits

of the possible objects of a conspiracy, but after some discussion of the subject

made this general statement: W here the act is lawful for an individual, it can

be the subject of a conspiracy, when done in concert, only where there is a

direct intention that injury shall result from it, or where the object is to benefit

the conspirators to the prejudice of the public or the oppression of individuals,

and where such prejudice or oppression is the natural and necessary conse

quence.’ ” I l l Pa. Super, at 498-499, 170 Atl. at 431.

Statement of the Case 7

in fact, acts in the exercise of [defendants’ ] . . . rights

of freedom of speech, assembly and petition, guaranteed

by U. S. Const., Amends. I, XIV, and 42 U. S. C. § 1983

(1958), to protest [inter alia] . . . unlawful racial dis

crimination against Negroes in the schools of the City of

Chester, violating the rights of petitioners and others simi

larly situated” under the federal Constitution and laws

(App. 6a), and hence that defendants “ are being prose

cuted for acts done under color of authority derived from

the federal Constitution and laws providing for equal

rights” (App. 6a), within the meaning of the applicable

removal statute, 28 U. S. C. § 1443(2) (1958). It was fur

ther asserted that some of the statutes and common-law

doctrines under which the defendants were prosecuted were

unconstitutional on their face for vagueness (App. 7a),

and that the arrests and prosecutions of defendants were

carried on with the sole purpose and effect of harassing

the defendants, punishing them for, and deterring them

from, exercising their constitutionally protected rights of

free expression to protest unconstitutional discrimination

(App. 6a-7a). This harassment was alleged to be pursuant

to a policy of racial discrimination and repression of

Negroes’ free speech by state and local officials, evidenced

by the multiplication of criminal charges, some federally

unconstitutional on their face, against the defendants (App.

7a).

Additionally, it was alleged that the defendants “ have

been denied, are being denied, and cannot enforce in the

courts of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania rights under

the cited federal constitutional and statutory sections pro

viding for the equal rights of citizens . . . and of all

persons” (App. 7a), within the meaning of 28 U. S. C.

§1443(1) (1958), because First Amendment freedoms to

protest racial discrimination were involved and the state

courts were hostile (App. 7a). Particularizing the charge

of hostility, detailed factual allegations were made tending

to support the conclusions that excessive and increasing

8 Statement of the Case

bond was demanded of arrested demonstrators (App. 7 a-

8a), that the 240 demonstrators were being pressed to trial

on the indictable charges with such speed that they would

not have time adequately to prepare their federal constitu

tional and other defenses (App. 9a-12a), and that news

paper and radio publicity in Delaware County, for which

police brutality in suppressing the civil rights demonstra

tions and a public statement by the Lieutenant Governor of

Pennsylvania endorsing police use of force as necessary to

maintain law and order were responsible, had created in

the county an atmosphere of prejudice against the defend

ants which made a fair trial impossible (App. 8a-9a), par

ticularly because of the restrictive Pennsylvania practice in

respect of change of venue and voir dire examination of

jurors (App. 9a), and because the state trial judges are

elected judges politically responsible to the racially hostile

and fearful county electorate (App. 9a).

The Answer to Petition for Eemoval and Motion to

Dismiss Said Petition in effect denied all of the material

allegations of fact of the removal petitions (App. 22a-28a),

and affirmatively alleged ‘ ‘ that there is no problem of civil

rights involved in the present State prosecution” (App.

23a), that “ the prosecution in all of these cases has been

conducted in the usual manner in which all State prosecu

tions are conducted” (App. 23a), and that “ the criminal

acts for which defendants are being prosecuted are crimes

which have been part of the law of Pennsylvania for many

years, and which crimes have been interpreted and re

interpreted by the various Courts in Pennsylvania, as well

as Federal Courts” (App. 24a). Additionally, allegations

of fact were made tending to support the conclusion that

defendants were not being rushed to trial with such speed

that they could not adequately prepare their defenses (App.

25a-27a).

On the same morning when the Answer was served the

prosecution’s motion to remand, based on the Answer, was

Statement of the Case 9

argued before Chief Judge Clary. After counsel were

heard on the issue of construction of the removal statute

invoked, the court asked counsel for the defendants: “ Do

you want to go any further? Do you want to try to estab

lish, although I don’t know how you could, your allegations

of basic hostility of the courts and people of Delaware

County?” (App. 29a). Counsel replied that his chief

grounds for removal did not depend on evidentiary ques

tions, but that insofar as the prosecution’s Answer had

denied the allegations of the removal petition counsel was

not inclined to leave the allegations unproved and would

like a hearing (App. 29a). The court said that it was

“ ready to proceed right now” (App. 29a). Counsel for de

fendants said that he had no witnesses ready that same

morning on issues of such complexity and would want ade

quate time to prepare for a hearing (App. 29a-30a). The

court asked what such a hearing would involve. Counsel

replied that persons familiar with the community would be

called to testify as to the atmosphere and attitude in Dela

ware County, and that public officials would be called to

testify concerning their attitude and reasons for the prose

cution (App. 30a).8 The court thereupon refused a hearing

and took the matter under advisement (App. 30a). Subse

quently, “ upon consideration of plaintiffs’ Motion for Re

mand, hearing held and argument had thereon, and after a

thorough examination and careful consideration of the well-

pleaded factual (as opposed to psychological and conclu-

sory) averments set forth in defendants’ petitions for

removal, and the points raised and authorities cited therein,

as well as the records of the Court of Quarter Sessions of

the Peace and General Jail Delivery of Delaware County,

and the Court of Common Pleas of Delaware County, sub

mitted therewith,” the court held the cases improperly re

moved and remanded them to the respective state courts

(App. 31a-32a).

8. Defense counsel further offered to proceed by deposition, in lieu of

hearing in open court (App. 30a).

10 Statement of the Case

On this record it is clear that Chief Judge Clary prop

erly treated the motion to remand as addressed to the face

of the removal petitions and supporting state-court docu

ments, and that he held the petitions’ well pleaded allega

tions insufficient to sustain federal jurisdiction under 28

U. S. C. § 1443(1), (2) (1958), Thus the issue on this ap

peal is whether the removal papers pleaded a sufficient case

for removal under the statute.

A R G U M E N T .

Argument 11

(A) Introduction.

( 1 ) S u m m a r y .

In the District Court, defendants took the position that

their petitions for removal adequately invoked federal re

moval jurisdiction on four principal theories: (1) that the

acts for which they were prosecuted were acts ‘ ‘ under color

of authority derived from any law providing for equal

rights,” within 28 U. S. C. § 1443(2) (1958); and that they

were denied and could not enforce their federally protected

equal civil rights in the state courts, within 28 U. S. C.

§ 1443(1) (1958), because (2) the statutes under which they

were prosecuted were unconstitutional under the First and

Fourteenth Amendments; (3) the conduct for which defend

ants were prosecuted was conduct protected by the First

and Fourteenth Amendments and federal civil rights legis

lation, and the maintenance of state court prosecutions for

such conduct in itself punished and deterred the exercise

of federal civil rights; and (4) by reason of public hostility,

precipitous trial and other circumstances attending the

state prosecutions, defendants could not obtain a fair trial

in the state courts. On this appeal, defendants rely on the

first three of these theories, argued as points (B), (C) and

(D) infra® In anticipation of an attack upon the jurisdic- 9

9. For the information of the Court, defendants wish to indicate that their

abandonment here of the fourth theory—which may be briefly characterized as

a theory of actual hostility on the part of the state courts— is motivated by

three principal considerations. (1 ) As Congress recognized in enacting §901

of the Civil Rights A ct of 1964, infra, p. 43, the obtaining of an adequate

judicial construction of the federal civil rights removal provisions, 28 U. S. C.

§ 1443 (1958), is o f prime importance to the civil rights movement in this

country. Cases are now pending in the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Circuits in

which civil rights demonstrators seeking removal rely upon the same theories

put forward by defendants in the present case, including the “hostility” theory.

In some of these cases—particularly cases arising in Mississippi and Alabama—

the record on the issue of hostility is more favorable to removal than the

record made by facts which defendants could conscientiously allege or practicably

prove in the present case. Accordingly, defendants think it best to let the

hostility issue come to the federal Courts of Appeals, and the Supreme Court

if need be, first in the Southern cases. (2 ) In the present case, defendants

could prevail on the hostility theory only after an evidentiary hearing in the

District Court, on remand by this Court, in which factual allegations made in

12 Argument

tion of this Court to review the remand order of the Dis

trict Court, defendants in point (E) infra support the

Court’s appellate jurisdiction.

(2 ) T h e R emoval S tatute and I ts H istoby.

Defendants’ arguments for removal rely upon 28

U. S. C. § 1443 (1958), which provides:

“ § 1443. Civil rights cases.

“ Any of the following civil actions or criminal

prosecutions, commenced in a State court may be re

moved by the defendant to the district court of the

United States for the district and division embracing

the place wherein it is pending:

“ (1) Against any person who is denied or

cannot enforce in the courts of such State a right

under any law providing for the equal civil rights

of citizens of the United States, or of all persons

within the jurisdiction thereof;

“ (2) For any act under color of authority de

rived from any law providing for equal rights, or

for refusing to do any act on the ground that it

would be inconsistent with such law. (June 25,

1948, ch. 646, 62 Stat. 938.) ”

It is important at the outset to see this statute in the

grain of history. Progressively since the inception of the

Government, federal removal jurisdiction has been ex

the removal petitions and denied in the prosecution’s Answer would be explored.

Even following such a hearing, further federal appellate proceedings might be

required. Defendants and their counsel lack the resources for such extended

proceedings. (3 ) The passage of time since the filing of the removal petitions

m this case has affected several of the evidentiary issues raised by the hos

tility theory, particularly the issues of community hostility and fear and of

precipitated state court trial making impossible adequate preparation of federal

defenses.

Defendants should make clear that in abandoning a theory of actual hos

tility of the state courts, they do not abandon the theory that inherently all

state courts (and particularly those whose judges are elected) are less sym

pathetic to federal constitutional rights than are the federal courts. This theory,

on which is based congressional creation of federal trial courts and particularly

the federal civil rights removal jurisdiction, is essential to defendants’ points

(B ) , (C ) and (D ) infra. P

Argument 13

panded by Congress 10 to protect national interests in cases

" in which, the state tribunals cannot be supposed to be im

partial and unbiased,” 11 for, as Hamilton wrote in The

Federalist, "The most discerning cannot foresee how far

the prevalency of a local spirit may be found to disqualify

the local tribunals for the jurisdiction of national causes

. . . ” 12 In the federal convention Madison pointed out

the need for such protection, just before he successfully

moved the Committee of the Whole to authorize the na

tional legislature to create inferior federal courts: 13

"M r. [Madison] observed that unless inferior

tribunals were dispersed throughout the Bepublic with

final jurisdiction in many cases, appeals would be multi

plied to a most oppressive degree; that besides, an

appeal would not in many cases be a remedy. What

was to be done after improper Verdicts in State trib

unals obtained under the biassed directions of a de

pendent Judge, or the local prejudices of an undirected

jury? To remand the cause for a new trial would

answer no purpose. To order a new trial at the su

preme bar would oblige the parties to bring up their

witnesses, tho’ ever so distant from the seat of the

Court. An effective Judiciary establishment commen

surate to the legislative authority, was essential. A

10. See H art & W echsler, T he Federal Courts and T he F ederal Sys

tem 1147-1150 (1953). Before 1887, the requisites for removal jurisdiction

were stated independently of those for original federal jurisdiction; since 1887,

the statutory scheme has been to authorize removal generally of cases over

which the lower federal courts have original jurisdiction and, additionally, to

allow removal in special classes of cases particularly affecting the national

interest: suits or prosecutions against federal officers, military personnel, per

sons unable to enforce their equal civil rights in the state courts, persons acting

under color of authority derived from federal law providing for equal rights

or refusing to act inconsistently with such law, the United States (in fore

closure actions), etc. 28 U. S. C. §§ 1441-1444 (1958) ; see H art & W echsler,

supra, at 1019-1020.

11. T he F ederalist, No. 80 (Hamilton) (Warner, Philadelphia ed. 1818),

at 429.

12. Id., No. 81, at 439.

13. I F arrand, R ecords of the F ederal Convention 125 (1911). Mr.

Wilson and Mr. Madison moved the matter in pursuance of a suggestion of

Mr. Dickinson.

14 Argument

Government without a proper Executive & Judiciary

would be the mere trunk of a body without arms or legs

to act or move.” 14

The Judiciary Act of 1789 allowed removal in specified

classes of cases where it was particularly thought that local

prejudice would impair national concerns.15 But it was not

then supposed that the necessary and proper place for the

trial litigation of all issues of federal law was in the fed

eral courts, and no general “ federal question” jurisdiction

was given to those courts either in original actions or on

removal.16 Bather, during three quarters of a century fed

eral trial jurisdiction was created ad hoc in special situa

tions where there was more than ordinary cause to distrust

the state judicial institutions. Extensions of the removal

jurisdiction particularly were employed in 1815 and 1833 to

shield federal customs officials, respectively, against New

England’s resistance to the War of 1812 and South Caro-

lina’s resistance to the tariff.17 Thirty years later, to meet

14. I id. 124.

r *S- ,T he A ct Of September 24, 1789, ch. 20, § 12, 1 Stat. 73, 79-80, authorized

removal m three classes of cases where more than $500 was in dispute: suits

Dy a citizen of the forum state against an outstater; suits between citizens of the

same state in which the title to land was disputed and the removing party set

up an outstate land grant from the forum state; suits against an alien. The

11 If.1 J b ,0 classes were specifically described by Hamilton as situations “ in

which the state tribunals cannot be supposed to be impartial,” T he Federalist,

No. 80 (Hamilton) (Warner, Philadelphia ed. 1818), at 432; and Madison

speaking of state courts in the Virginia convention, amply covered the third •

We well know sir, that foreigners cannot get justice done them in these

courts . . . I l l E lliot’s Debates 583 (1836).

16. See H art & W echsler, T he Federal Courts and T he Federal

Svstem 727-733 (1953). General federal question jurisdiction was conferred

by the brief-lived federalist A ct of February 13, 1801, ch 4 8 11 2 Stat 89

92 repealed by the A ct of March 8, 1802, ch. 8, 2 Stat. 132. ' i t w as'not

restored until 1875. See text infra.

at * Fl > „ 1815’ cb; , 31’ §8 > 3 Stat 19S. 198 i also A ct ofMarch 3, 1815, ch. 43, § 6, 3 Stat. 231, 233. Concerning Northern resistance

to the W ar culminating in the Hartford Convention of 1814-1815, see 1

MORISON & Commager, Growth of the A merican R epublic 426-429 (4th ed.

~ ( J 1, ̂ March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §3, 4 Stat. 632, 633. Concerning South

Carolina s resistance to the successive tariffs, culminating in the nullification

ordinance, see 1 M orison & Commager, supra, 475-485. The Force A ct of

March 2, 1833, responded to the Southern threat not merely by extending the

removal jurisdiction of the federal courts, but by establishing a new head of

habeas corpus jurisdiction. Section 7, 4 Stat. 632, 634. See Fay v. Noia 372

U. S. 391, 401 n. 9 (1963).

Argument 15

the new stresses of the Civil War, Congress extended the

1883 act to cover cases involving internal revenue collec

tion as well as collection of customs duties. Act of March

7, 1864, ch. 20, § 9, 13 Stat. 14, 17; Act of June 30, 1864, ch.

173, § 50, 13 Stat. 223, 241; Act of July 13, 1866, ch. 184,

§§ 67-68,14 Stat. 98, 171,172, p. 23, infra. And when by the

Act of March 3, 1863, ch. 81, 12 Stat. 755, Congress author

ized the President to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, and

barred civil and criminal actions against persons making

searches, seizures, arrests and imprisonments under Presi

dential orders during the existence of the rebellion, it pro

vided by § 5, 12 Stat. 756, for removal of any suit or prose

cution against officers or persons for arrests or imprison

ments made, or other trespasses or -wrongs done or com

mitted, or any act omitted to be done, during the rebellion,

by virtue or under color of any authority derived from or

exercised under the President or act of Congress. See

pp. 23-24, infra. The debates on passage of this 1863 act re

flect congressional concern that federal officers could not

receive a fair trial in hostile state courts, and also echo

Madison’s fear that the appellate supervision of the Su

preme Court of the United States would be inadequate to

rectify the decisions of lower state tribunals having the

power to find the facts.18

18. A provision confirming the application of the act to criminal as well

as civil proceedings was added by amendment on the Senate floor after the

favorable reporting of the House Bill, as amended (so substantially as to

amount to a substitute bill) by the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. (The

House Bill is set out at Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 3d Sess. 21 (12 /8 /62 ), as

introduced, id. at 20 (12 /8 /62 ), and as passed, id. at 22 (1 2 /8 /6 2 )) . The bill

as reported_ by the Senate Committee on the Judiciary id. at 321 (1 /14 /63 ),

is set out, id. at 529 (1 /27 /63 ). Mr. Harris moved to amend it by adding to

the removal provision, qualifying the description of removable actions, the

words: “ civil or criminal.” Id. at 534 (1 /27 /63 ). The chairman of the Ju

diciary Committee, Mr. Trumbull, did not support the amendment. Ibid. Mr.

Clark, who did, supposed the case of state officers killed by the federal marshal

in an attempt to execute state-court habeas corpus process in respect of a

prisoner held by the marshal under authority of the Secretary of W a r ; “ . . .

what sort r f fair trial could the marshal have had in the State court, where

the authorities of the State were arrayed on one side and the United States

on the other?” Id. at 535 (1 /27 /63 ). Mr. Cowan also supported the amend

ment in the brief debate which immediately preceded its adoption; he hypothe

sized the case of a federal officer who killed a man he was attempting to arrest

under presidential warrant and he took the view that the officer ought to have

16 Argument

The Civil War radically changed the view which the

national legislature had previously taken, that generally

the state legislatures, courts and executive officials were the

sufficient protectors of the rights of the American people.

The Thirteenth, Fourtenth and Fifteenth Amendments

wrote into the Constitution broad new guarantees of lib

erty and equality in which the federal government commit

ted itself to protect the individual against the States. The

four major civil rights acts undertook to elaborate and

effectively establish the new liberties and, significantly, each

of the acts contained jurisdictional provisions making the

federal courts the front line of federal protection.19 No

longer was it assumed that the state courts were the normal

place for the enforcement of federal law save in the rare

and narrow cases where they showed themselves unfit or

unfair. Now the federal courts were seen as the needed

organs, the ordinary and natural agencies, for the admin

istration of federal rights. Frankfurter & Landis, T he

B usiness op th e S upbeme C ourt 64-65 (1928). This is ap

parent not only in the purpose of the civil rights acts them

selves to create a supervening federal trial jurisdiction. * •

the right to remove a state indictment against him. Id. at 537-538 (1 /27 /63 ).

• rL c 1 e m(5ulll :d why a trial in the state court, subject to a right of review

S w rei? ec S ° ’)rit/o °v /5 f United States, would not suffice to protect the

officer. Id. at 538 (1 /27 /63 ). Mr. Cowan replied: “ Mr. President, only the

indictment goes into the court upon a special allocatur. The testimony could

nothmg the indictment and the simple plea would g o ; and upon

that the court could not determine the character of his defense. Besides, the

character of this defense is one of fact to a great extent, and might depend on

probable cause, and that has to be passed upon by a jury under the direction

of the court; because if the court could pass upon the question of fact, there is

an end of it; no appeal lies from a tribunal which is intrusted with the deter

mination of questions of fact. In the first place, the question on which the

defense rests must exist m criminal cases, as a general rule, in parol— this order

of the President may have been by parol—and it must be submitted to the

jury, and determined by the jury under the direction of the court, with authority

to try it. I do not undertake to say that the criminal might not submit himself

to that jurisdiction, because the jurisdiction of the United States is not exclusive.

He tnight submit to it, but if he was desirous to have the question determined

m the courts of the United States, he has unquestionably a clear right to have

it so determined. Ibid. (M r. Cowman is reported, ibid., as voting against the

amendment, although he voted for passage of the bill as amended, id. at 554.)

19. A ct of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §3, 14 Stat. 27; A ct of May 31 1870 ch

114, §§ 8, 18, 16 Stat. 140, 142, 144; A ct of April 20, 1871, ch. 22 S 1 17 Stat’

13; A ct of March 1, 1875, ch. 114, § 3, 18 Stat. 335, 336.

Argument 17

See Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961); McNeese v.

Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 (1963). It is apparent

also in the enactment of the Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 28,

14 Stat. 385, the federal habeas corpus statute now found in

28 U. S. C. § 2241(c) (3) (1958), which assured that every

state criminal defendant having a federal defensive claim

would have a federal trial forum for the litigation of the

facts underlying that claim. See Fay v. Noia, 372 IT. S. 391

(1963); Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963). And it is

particularly apparent in the Judiciary Act of March 3,

1875, ch. 137, 18 Stat. 470, which created general “ federal

question” jurisdiction in original and removed civil actions

and thus wrote permanently into national law the provision

of a federal trial court for every civil litigant engaged in a

significant controversy based on a claim arising under the

federal Constitution and laws. See 28 U. S. C. §§ 1331,

1441 (1958). driven the post-Civil War view of the state

courts, the justification for such a federal trial jurisdiction

is obvious enough. England v. Louisiana State Board of

Medical Examiners, 375 U. S. 411, 416-417 (1964):

“ Limiting the litigant to review here [the Su

preme Court] would deny him the benefit of a federal

trial court’s role in constructing a record and making

fact findings. How the facts are found will often dic

tate the decision of federal claims. ‘ It is the typical,

not the rare, case in which constitutional claims turn

upon the resolution of contested factual issues. ’ Town

send v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293, 312. ‘ There is always in

litigation a margin of error, representing error in fact

finding. . . . ’ Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513, 525.

. . . The possibility of appellate review by this

Court of a state court determination may not be sub

stituted, against a party’s wishes, for his right to liti

gate his federal claims fully in the federal courts.”

The removal provisions upon which defendants herein

rely, present 28 IT. S. C. § 1443 (1958), originate in the

18 Argument

earliest of these post-Civil War enactments: the civil rights

act of 1866, passed by the 39th Congress. See pp. 24-25,

infra. The attitude of that Congress toward the state courts

is evident; 20 it is perfectly expressed by Senator Lane of

Indiana in debate on the 1866 act:

“ What are the objects sought to be accomplished

by this bill? That these freedmen shall be secured in

all the rights, privileges, and immunities of freedmen;

in other words, that we shall give effect to the procla

mation of emancipation and to the constitutional

amendment. How else, I ask you, can we give them

effect than by doing away with the slave codes of the

respective States where slavery was lately tolerated?

One of the distinguished Senators from Kentucky [Mr.

G u t h r i e ] says that all these slave laws have fallen

with the emancipation of the slave. That, I doubt not,

is true, and by a court honestly constituted of able and

upright lawyers, that exposition of the constitutional

amendment would obtain.

“ But why do we legislate upon this subject now?

Simply because we fear and have reason to fear that

the emancipated slaves would not have their rights in

the courts of the slave States. The State courts al

ready have jurisdiction of every single question that

we propose to give to the courts of the United States,

why then the necessity of passing the law? Simply

because we fear the execution of these laws if left to * •

, 2 ° , S - Blyew v. United States, 13 Wall. 581, 593 (1871)

of the 1866 act was v ' The purpose

• ' to guf.rd all the declared rights of colored persons, in all

civil actions to which they may be parties in interest, byP giving to the

District and Circuit Courts of the United States jurisdiction of such actions

t t r eArJ he S-ta-e r rtS any- right enjoyed br white c’ tizens is denied them. And m criminal prosecutions against them, it extends a like pro-

whj’ h11' ^ Y aiT 0t exPected to be ignorant of the condition of thmgs

which existed when the statute was enacted, or of the evils which it wfs

exUte8d 1S f el1 ,known that in many of the States, laws

existed which subjected colored men convicted of criminal offenses to

Argument 19

the State courts. That is the necessity for this pro

vision.* 21

The 1866 removal provisions were reenacted in 1870, see

p. 25, infra, and expanded by the Ku Klux Act of 1871, see

pp. 31-32, infra, a statute whose legislative history, equally

with that of the original 1866 act, demonstrates extreme

congressional distrust of the state courts. See Monroe v.

Pape, supra. There can be no doubt that the Congress

which enacted these statutes meant broadly to remove civil

rights litigation from the state to the federal courts, for

fear that the state courts generally would fail adequately

to protect the new-created nationally guaranteed liberties

of the individual. It remains to be seen whether the lan

guage used was ample to effect that purpose in the present

case.

punishments different from and often severer than those which were in

flicted upon white persons convicted of similar offenses. The modes of

trial were also different, and the right of trial by jury was sometimes denied

them. I t is also well known that in many quarters prejudices existed

against the colored race, which naturally affected the administration of

justice in the State courts, and operated harshly when one of that race

was a party accused. These were evils doubtless which the act of Congress

had in view, and which it intended to remove. And so far as it reaches,

it extends to both races the same rights, and the same means of vindicating

them.” (Emphasis added.)

21. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 602 (2 /2 /6 6 ). See also Mr. Broom-

all in the House debates, id., at 1265 (3 /8 /6 6 ). It is clear that a principal

purpose of the 1866 act was to counteract the Black Codes, legislation enacted

by the southern legislatures after emancipation to oppress the freedmen. The

Codes are often referred to in debate, usually for the purpose of demonstrating

that, unless restrained by federal authority, the southern States would dis

criminate against the Negro and deprive him of his liberty. In the Senate:

Id. at 474 (Trumbull, 1 /29/66), 602 (Lane, 2 /2 /66 ), 603 (W ilson, 2 /2 /66 ),

605 (Trumbull, 2 /2 /6 6 ) ; in the House: id. at 1118 (W ilson, 3 /1 /66 ), 1123-

1125 (Cook, 3 /1 /66 ), 1151 (Thayer, 3 /2 /66 ), 1160 (Windom, 3 /2 /66 ), 1267

(Raymond, 3 /8 /66 ). While most of the Codes were discriminatory on their

face, applying only to the freedmen, see, e.g., 2 Commager, D ocuments of

A merican H istory 2-7 (6th ed. 1958); 1 Fleming, D ocumentary H istory

of R econstruction 273-312 (Photo reprint 1960), not all were of this sort.

Much mention was made in the debates of the southern vagrancy laws, e.g.,

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1123-1124 (Cook in the House, 3 /1 /66) ;

1151 (Thayer in the House, 3 /2 /66 ), and particularly of the vagrancy law of

Virginia, id. at 1160 (W indom in the House, 3 /2 /66) ; 1759 (Trumbull in the

Senate, 4 /4 /66 ). This was a color-blind statute, Acts of Virginia, 1865-1866,

91 (A ct of January 15, 1866) (1866), whose evil lay in its systematically dis

criminatory administration by the Virginia courts. See Cong. Globe, 39th

Cong., 1st Sess. 603 (W ilson in the Senate, 2 /2 /66 ). As Congress knew, the

Union military commanders in the southern districts had already taken steps

to protect the freedmen from such judicial maladministration by providing

20 Argument

(B) Defendants’ Removal Petitions Sufficiently State a

Removable Case Under 28 U. S, C. § 1443(2).

Subsection (2) of 28 U. S. C. § 1443 allows removal by

a defendant of any prosecution “ For any act under color

of authority derived from any law providing for equal

rights.” The provision has been little litigated and never * 46

military courts to supersede the civil courts in cases involving the freedmen,

e.g., id. at 1834 (4 /7 /6 6 ); M cP herson, P olitical H istory of the U nited

States D uring the P eriod of R econstruction 41-42 (1871), and the removal

provisions of the 1866 act undoubtedly intended to give the freedmen the same

protection.

Further^ overwhelming evidence that Congress recognized the need for

removal jurisdiction to protect federal interests from exposure to litigation in

biased and hostile state trial courts is found in the debates on the bill, H. R.

238, 39th Cong., which was enacted as the A ct of May 11, 1866, ch. 80, 14 Stat.

46. This bill was debated contemporaneously with the Civil Rights A ct of

1866; it strengthened the removal provisions of the A ct of March 3. 1863,

ch. 81, 12 Stat. 755— the provisions for removal which were adopted by refer

ence, together with all amendments, in the Civil Rights A ct of 1866, see pp.

24-2$ infra— by (1 ) extending the time for removal up to the point of em

paneling of the jury in the state court, (2 ) eliminating the 1863 requirement

of a removal bond, (3 ) directing that upon the filing of a proper removal

petition all state proceedings should cease, and that any state court proceedings

after removal should be void and all parties, judges, officers or other persons

prosecuting such proceedings should be liable for damages and double costs to

the removing party, and (4 ) directing the clerk of the state court to furnish

copies of the state record to a party seeking to remove, and permitting that

party to docket the removed case in the federal court without attaching the

state record in case of refusal or neglect by the state court clerk. These

debates demonstrate thorough congressional awareness of the extreme hostility

of the Southern state trial courts, their arbitrary discrimination against federal

interests, and their wilful refusal to protect federal rights. Cong. Globe, 39th

Cong., 1st Sess. 1S26 (M cKee, in the House, 3 /20/66), 1327 (Garfield, in the

House, 3 /20/66), 1327-1528 (Smith, in the House, 3 /20/66), 1329-1330 (Cook,

who reported the bill from the House Committee on the Judiciary, id. 1368

(3 /13 /66 ), and was its floor manager, id. 1387 (2 /14 /66 ), in the House,

3 /20/66), 2021 (Clark, in the Senate, 4 /18/66), 2054 (W ilson and Clark, in

the Senate, 4 /20/66), 2055 (Trumbull, Chairman of the Senate Committee on

the Judiciary, in the Senate, 4 /20/66). A particularly pertinent exchange is

that between Senator Doolittle, who opposed the provision making state judges

liable for damages for proceeding in defiance of a removal petition, and Senator

Clark, who reported the bill from the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, id.

1753 (4 /4 /66 ) and was its floor manager, id. 1880 (4/11/66) :

“ Mr. Doolittle: I think we ought to presume that the judge of a State,

in his judicial office, who by the Constitution of the United States is bound

to take an oath that he will support the Constitution of the United States,

and all laws made in pursuance thereof, anything contained in any State

constitution or law to the contrary notwithstanding, will not violate his

oath of office. . . . [I ]t is not necessary to presume in the law of Congress

that the judge will commit a crime. W hy is it necessary to put it in

your statute?

“ Mr. Clark: I desire to make but one suggestion in answer to the

Senator from Wisconsin, and that is one of fact. He says if it were

necessary that these judges should be proceeded against he would not

Argument 21

construed in its application to circumstances like those

of the present case.* 22 It is defendants’ position (1) that

an act is “ under color of authority” of law if it is done

in the exercise of freedoms protected by that law; (2) that

Rev. Stat. § 1979, 42 U. S. C. § 1983 (1958), is a “ law pro

viding for equal rights” and protects, inter alia, acts in the

exercise of First Amendment freedom of speech to protest

racial discrimination; and (3) that defendants are being

prosecuted for such protected acts.

object. I hold in my hand a communication from a member of the other

House from Kentucky, in which he says that all the judicial districts of

Kentucky, with the exception of one, are in the hands of sympathizing

judges. They entirely disregard the act to which this is an amendment.

They refuse to allow the transfer, and proceed against these men as if

nothing had taken place. Here is not the assumption that these judges

will not do this; here is the fact that they do not do it, and it is necessary

that these men should be protected.” Id. at 2063 (4 /20 /66 ).

22. In Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Supp. 626 (E . D. Ark. 1963) removal

was sought of prosecutions for assault with intent to kill and for carrying a

knife, charges arising out a fight between defendant and a white student after

rocks were thrown at the station wagon in which defendant was escorting home

from school two Negro students (one, defendant’s niece) who had that day

been enrolled in a previously segregated school under federal court order. De

fendant invoked § 1443(2) on the theory that in escorting the children and

protecting himself and them from persons who sought to frustrate enrollment,

he was acting under color of authority derived from the Civil Rights A ct of

1960, under which the enrollment order was made. The court assumed ar

guendo that in some circumstances removal under §1443(2) was available to

a private individual charged with an offense arising out of his escorting pupils

to a school in process of desegregation under federal court order, but held

that this defendant, in his knife fight with the white student, was nop imple

menting the court’s integration order since that order made no provision for

transporting or escorting the children to school, in light of the previously peace

ful history of the school controversy, by virtue of which, prior to the day of

enrollment, there was no reason to anticipate violence; hence there was no

“proximate connection,” 218 F. Supp. at 634, between the court’s order and

defendant’s fight.

In Hodgson v. Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. 28S, No. 6,568 (Grier, C.J., E. D.

Pa. 1863), approved in Braun v. Sauerwein, 10 Wall. 218, 224 (1869), Justice

Clifford held that a sufficient showing of “color of authority” was made to

justify removal under the 1863 predecessor of 28 U. S. C, §1443(2) (1958)

where it appeared that the defendants in a civil trespass action, the United

States marshal and his deputies, seized the plaintiff’s property under a warrant

issued by the federal district attorney, purportedly under authority of a Presi

dential order, notwithstanding the order might have been invalid. For the

facts of the case, see Hodgson v. Millward, 3 Grant (P a .) 412 (Strong, J.

at nisi prius. 1863). This establishes that “ color of authority” may be found

where a federal officer acts under an order which is illegal. See Potts v.

Elliott, 61 F. Supp. 378, 379 (E . D. Ky. 1945) (court officer civil removal case) ;

Logemann v. Stock, 81 F. Supp. 337, 339 (D . Neb. 1949) (federal officer civil

removal case). But it does not advance inquiry as to whether “color of author

ity” exists in any other than the evident case of a regular federal officer acting

under express warrant of his office.

22 Argument

( 1 ) “ C O LO B OB A xT TH O B ITY ” .

On its face, the authorization of removal by a de

fendant prosecuted for any act “ under color of authority

derived from ” any law providing’ for equal civil rights

might mean to reach (a) only federal officers enforcing the

civil rights acts, (b) federal officers enforcing the civil

rights acts and also private persons authorized by the

officers to assist them in enforcing the acts, or (c) federal

officers and persons enforcing or exercising rights under

the civil rights acts. The legislative history and context

support the third construction.

Prior to the enactment in 1948 of 28 U. S. C. § 1442-

(a)(1) (1958),23 there was no statutory provision gen

erally authorizing removal of cases against federal officers.

As indicated at pp. 14-15, supra, Congress during the

nineteenth century enacted specific, narrow statutes allow

ing removal by designated kinds of officers only. In 1815,

it provided in a customs act for removal of suits or

prosecutions “ against any collector, naval officer, sur

veyor, inspector, or any other officer, civil or military, or

any other person aiding or assisting, agreeable to the pro

visions of this act, or under colour thereof, for anything

done, or omitted to be done, as an officer of the customs, or

for any thing done by virtue of this act or under colour

thereof . . . ” Act of February 4, 1815, ch. 31, § 8, 3 Stat.

195, 198; also Act of March 3, 1815, ch. 93, § 6, 3 Stat. 231,

233. In 1833, it enacted the Force Act of March 2, 1833,

ch. 57, 4 Stat. 632, whose second section envisioned that

23. § 1442. Federal officers sued or prosecuted.

“ (a ) A civil action or criminal prosecution commenced in a State

court against any of the following persons may be removed by them to

the district court of the United States for the district and division em

bracing the place wherein it is pending:

“ (1) Any officer of the United States or any agency thereof, or

person acting under him, for any act under color of such office or on

account of any right, title or authority claimed under any A ct of

Congress for the apprehension or punishment of criminals or the

collection of the revenue.

Argument 23

private individuals, as well as federal officers, might take

or hold property pursuant to the revenue laws; and whose

§3, 4 Stat. 633 allowed removal of any “ suit or prosecu

tion . . . against any officer of the United States, or other

person, for or on account of any act done under the rev

enue laws of the United States, or under colour thereof,

or for or on account of any right, authority, or title, set