Draft Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Working File

January 1, 1971

51 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Draft Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 1971. 9d319fa4-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/44e6b3db-c52b-48d9-a456-9330e48092fc/draft-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

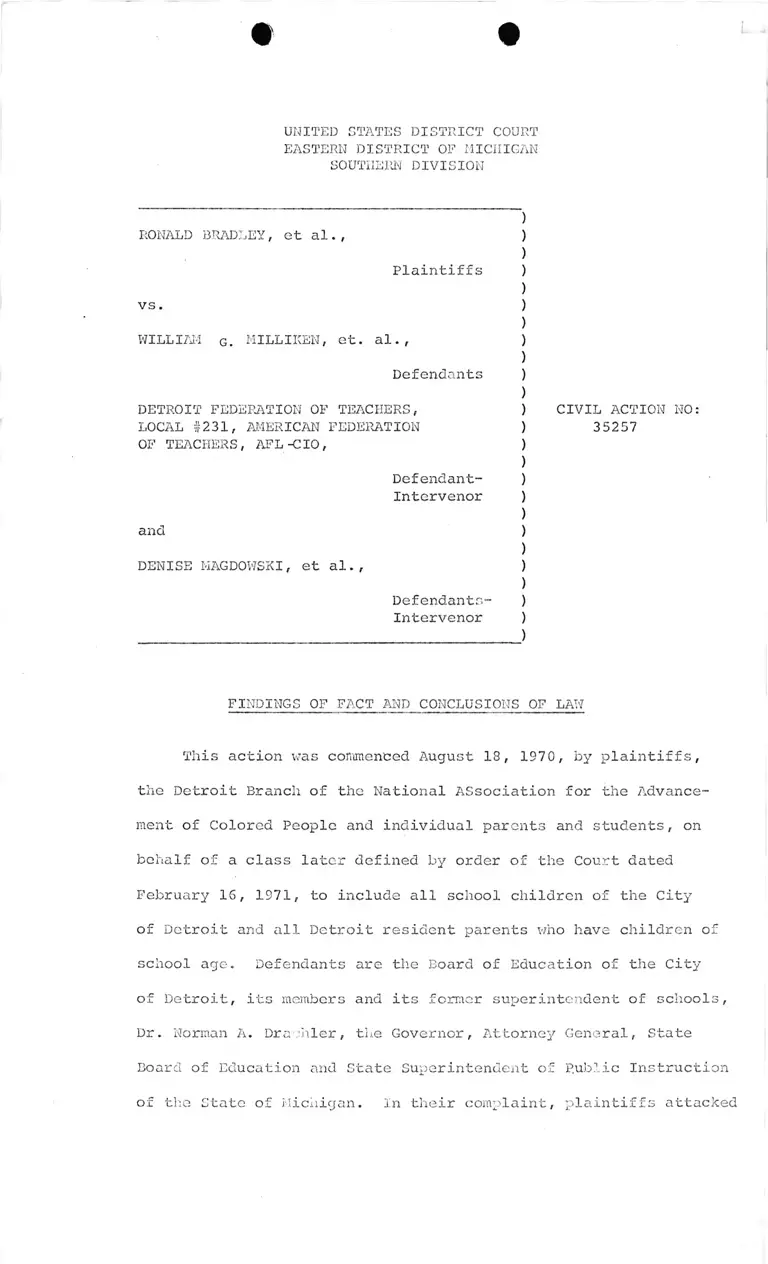

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

)

RONALD BRADLEY, et al., )

)

Plaintiffs )

)

vs. )

)

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et. al., )

)

Defendants )

)

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, ) CIVIL ACTION NO:

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION ) 35257

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, )

)

Defendant- )

Intervenor )

)

and )

)

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al., )

)

Defendants- )

Intervenor )

______ )

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

This action was commenced A.ugust 18 , 197 0, by plaintiffs,

the Detroit Branch of the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People and individual parents and students, on

behalf of a class later defined by order of the Court dated

February 15, 1971, to include all school children of the City

of Detroit and all Detroit resident parents who have children of

school age. Defendants are the Board of Education of the City

of Detroit, its members and its former superintendent of schools,

Dr. Norman A. Drachler, the Governor, Attorney General, State

Board of Education and State Superintendent of public Instruction

of the State of Michigan. In their complaint, plaintiffs attacked

a statute of the State of Michigan known as Act 48 of the 1970

Legislature on the ground that it put the State of Michigan in

the position of unconstitutionally interfering with the execution

and operation of a voluntary plan of partial high school desegre

gation (known as the April 7, 1270 Plan) which had been adopted

by the Detroit Board of Education to be effective beginning with

the fall 1970 semester. Plaintiffs also alleged that the Detroit

Public Scnool System was and is segregated on the basis of race

as a result of the official policies and actions of the defendants

and their predecessors in office.

Additional parties have intervened in the litigation since

it was commenced. The Detroit Federation of Teachers (DFT) which

represents a majority of Detroit public school teachers in

collective bargaining negotiations with the defendant Board of

Education, has intervened as a defendant, and a group of parents

has intervened as defendants.

Initially the matter was tried on plaintiffs' motion for

preliminary injunction to restrain the enforcement of Act 48

so as to permit the April 7 Plan to be implemented. On that issue,

this Court initially ruled that plaintiffs were not entitled to

a preliminary injunction since there had been no proof that

Detroit was a segregated school system. The Court of Appeals held,

however, that any such interference by the state with a determina

tion of a local school board to pursue the goals of racial

equality was forbidden and that, at a minimum, the state must

pursue a course of scrupulous neutrality and avoid steps whose

effect can only be to heighten or maintain racial segregation.

433 F.2d 897(6th Cir. 1970).

2

The plaintiffs then sought to have this Court direct the

defendant Detroit Board to implement the April 7 Plan by the

start of the second semester in order to remedy the deprivation

of constitutional rights wrought by the unconstitutional statute.

In response to an order of the Court, defendants suggested two

other plans in addition to the April 7 Plan which they contended

would result in integration promised by the April 7 Plan. The

Court, although concluding that in this context "nonaction is

(or amounts to) prohibited action," rejected the Plaintiffs'

arguments against the "magnet" plan at that time and approved

it rather than ordering April 7 implemented. Again, plaintiffs

appealed but the appellate court refused to pass on the merits

of the plan . Instead, the case was remanded with instructions

to proceed immediately to a trial on the merits of plaintiffs'

substantive allegations about the Detroit School System. 438

F.2d 945 (5th Cir. 1971).

That trial began April-6, 1971 and concluded on July 22, 1971

consuming forty-one trial days along with several brief recesses

necessitated by demands upon the time of Court and counsel.

Plaintiffs introduced substantial evidence in support of their

contentions, including expert and factual testimony, demonstrative

exhibits and School Board documents. At the close of plaintiffs'

case in chief, the Court ruled that they had presented a prima

facie case of state imposed segregation in the Detroit Public

School:.; accordingly, the Court enjoined (with certain exceptions)

all further school construction in Detroit pending the outcome of

the litigation.

3

The Court has also denied the motion to dismiss filed by

the state defendants at the conclusion of plaintiffs' case in

chief. The proof adduced by the plaintiffs was not solely

limited to the role played by the Detroit Board, its predecessors

and employees, in bringing about the present highly segregated

condition of the public schools. It also demonstrated inescapably

that the State of Michigan and its agencies have by acts and

omissions seemingly violative of its obligation under the

Michigan Constitution, contributed toward bringing about this

result. Furthermore, one of the intervening defendants has

filed a motion to require 85 suburban school districts to partici

pate in any school desegregation the Court might order.

On the basis of the proofs presented at trial and at the

previous hearings in this cause, the Court makes the following

kfindings of fact and conclusions of lav/.

"P.X." and "D.X." references are to plaintiffs' exhibits

and defendants' exhibits, respectively. Citations to the trial

transcript are in the form " ____ T r . ____" indicating the

volume and page numbers (e.g., 20 Tr. 2000). Citations to

transcripts of previous hearings are preceded by the hearing

date (e.g., 11/4/70 Tr. 100). Citations to depositions which

have been admitted into evidence are in similar form.

4

FINDINGS OF FACT

1. During the 1970-71 school year defendant Detroit Board

of Education operated 2S2 regular attendance-area schools, enrol-

1/ling 277,573 students of whom 177,079, or 63.8%, were Negro.—

[P.X. 128B, 152A].

2. These figures compare with 251 attendance-area [herein

after, "regular"] schools in operation in 1960-61 with an enroll

ment of 275,021 of whom 126,273, or 45.9%, were black. [P.X. 128A,

152A].

3. Of the 251 regular schools in operation in 1960-61, 171

or 68% were 90% or more one race (71 black, 100 white). [P.X. 150,

128A]. Of the 282 regular schools in current opc ation, 202 or

71.6% serve student enrollments which are 90% or more one race

(133 are black, 69 are white). [P.X. 150, 128B].

4. In 1960-61, 65.8% o:£ the total number of black students

in regular schools were in schools 90% or more black. In 1970-71

the percentage of black students in schools 90% or more black had

increased to 74.9%. [P.X. 129; 32 Tr. 3382-83].

5. Every school which was 90% or more black in 1960, and

which is still in use today, remains 90% or more black. [P.X. 150;

32 Tr. 3381-32].

—' In addition the Board operated 23 various non-attendance area

schools enrolling 8,130 students of whom 5,386 were black (P.X. 100J

at p. 127). The Board also had 4,146 students, of whom 1,798 were

blaclc, enrolled in special adulh programs. (P.X. 100J at p. 6).

5

6. In 1960-61 there were 9,884 teachers, of whom 2,366 or

23.9% were black, assigned to regular schools. In 1970-71,

11,616 teachers, of whom 4,853 or 41.8% were blade, were assigned

to regular schools. [P.X. 152B; cf. P.X. 100J at p. 2 showing

all faculties 1960-61 to 1970-71.]

7. In 1963 there were 99 schools with instructional staffs

less than 10% black (of which 41 had no black staff members) and

72 schools with instructional staffs 50% or more black. By

1970-71 the Board had reduced to 12 the number of schools with

less than 10% black faculties, but the number of schools with 50%

or more black faculties had increased to 124. [P.X. 100J at p. 3].

8. The public schools operated by defendant Board are thus

segregated on a racial basis. This racial segregation is t^e

result of the discriminatory acts and omissions of defendant

Board, which include the following:

A. Faculty

9. Prior to 1962 the Board operated an admittedly discrimina

tory policy and practice of faculty assignment. [38 Tr. 4340].

Until 1955 the Board assigned black teachers to schools which were

predominantly black, but never assigned black teachers to scnools

which were 50% or more white. [20 Tr. 2185]. Until 1964 no

black person was ever made Principal of a high school. [20 Tr.

2185-36].

6

u

10. In 1962 the Board-appointed Citizens Advisory Coramittee

on Equal Educational Opportunities found:

As to placement of teachers, the subcommittee finds

that, with only a few exceptions, Negro teachers

are placed only where there are Negro children in

attendance at school.

[P.X. 3 at p. 75; see also 20 Tr. 2132]. The EEO Committee further

found, and the evidence demonstrates, "that there is a tendency

for the proportion of Negro teachers in a school to increase as

the proportion of Negro pupils increases." [P.X. 3 at 75]. For

example, in 1955 Central High School was 70% white but incurred

faculty integration for the first time with the assignment of a

black counselor and a black teacher. But by 1970 Central was

100% black and its faculty was 55.9% black [20 Tr. 2180; P.X. 130],

whereas the system-wide faculty was only 41.3% black. [P.X. 1d2B]

See generally P.X. 3 at 76.

11. The 1962 EEO finding (P.X. 3 at 73)

that the Board of Education has followed a practice of ^

(1) assigning Negro teachers predominantly within certain

districts where there are large numbers of Negro pupils,

and (2) assigning Negro teachers chiefly to racially

mixed schools, in many cases on a proportional basis.

If there are no Negro children in a school, no Negro

teachers are assigned there; this rule has few exceptions

to date,

is clearly demonstrated by the testimony and exhibits. [P.^. 3

at 72-79(esp. map facing p. 78), 92-134(appendices-esp. graphs on

pp. 93-106); P.X. 154A].

12. The EEO Committee further found "that placement of

teachers by the Detroit Board of Education follows in general,

and with some departures, a definite racial pattern. . . . [and

that] Data also show that Negro administrators are placed only

7

«

where Negro children and Negro teachers are in the majority."

[P.X. 3 at 79]. The Court finds that the discriminatory assignment

of administrators persists, as is shown by the following table

taken from the October 1970 racial census, P.X. 100J, p. 10-20

(see also 22Tr. 2511-13):

Predominately

white

Constellations Administrators

Cody

Ford

Redford

Osborn

Denby

Finney

3 Negro

3 Negro

1 Negro

2 Negro

1 Negro

8 Negro

55 white

41 white

46 white

42 white

30 white

44 white

Predominately

blackConstellations Adm i n i s tr ators

King

Central

No r t hwestern

Northern

Northeastern

35 Negro

23 Negro

25 Negro

24 Negro

30 Negro

22 white

23 white

23 white

24 white

29 white

13. The EEO committee further found, and the evidence

demonstrates, discriminatory practices regarding the placement

of ESRPs and probationary teachers. "[W]henever Emergency Sub

stitutes or Probationary I's and II's are Negroes, they are

assigned to only 5 of the 9 districts. 3 at 74] . Tue

Committee further found "that a large nun’ r o [ESRPs and

probationary teachers] are currently assigned to 3 [black] dis

tricts - the Center, So t' east and East Districts • • • •" 3

at 83, 96-57].

8

14. In 1963 the Committee on Schools of the Detroit Com

mission on Human Relations reported to the Board its appraisal

of "the regular opportunities of the administrative staff to

place personnel on the basis of qualifications and preparation."

The Commission "found that in 1960-61, 51% of the school personnel

were involved in personnel transactions, and in the following

year, 54% or 10,429 contract personnel were involved. Many of

these changes represented significant opportunities to demon

strate a pattern c r teacher assignment without regard to race."

[P.X. 177 at 2]. The Commission found that despite these oppor

tunities the conditions reported by the 1962 EEO Committee

"remains virtually unchanged." Again, in 1964, the same group,

at the request of the Board, examined the 1963 racial count data.

Their findings reported to the Board and which are uncontradicted

in this record were (P.X. 178 at 2-3):

In October, 1963, Negro teachers were not assigned on the

staff of 56 of the city's 281 schools. Not one of the

city's 2,592 Negro teachers were assigned to 52 (or 25%)

of the elementary schools and 4 of the junior high schools.

In October, 1963, those schools which had from 0 to 4 Negro

teachers on their staff numbered 135, or approximately one

half of the city's schools. In these 135 schools, a total

of 182 (or 7%) of the Negro teachers were found. 3,428

white teachers were on the faculties of these 135 schools.

In October, 1963, those schools which had

teachers on their staffs numbered 146, or

remaining one half of the city's schools,

schools, a total of 2,410 (or 93%) of the

were found. 3,759 white teachers were on

5 or more Negro

approximately the

In these 146

Negro teachers

these school faculties.

In March, 1969, it was found that as the number of Negro

pupils in any particular school increased, the number of

Negro teachers in that school also increased. . .

9

F

In the 135 schools with 0 to 4 Negro teachers on their

staffs, 6% or 9,032 Negro pupils were found and 7%, or 132

Negro teachers were found.

In the remaining 146 schools with 5 or more Negro teachers

on their staffs, 94%, or 141,844 Negro pupils were found and

93%, or 2,410 Negro teachers were found.

In October, 1263, 102 elementary schools were found in the

category of from 0 to 4 Negro teachers on their staff.

Between March 30, 1963 and October 1, 1963, 385 placements

were made in these 102 elementary schools. The result of

these 385 placements was the net addition of only 35 Negro

teachers to these faculties.

In October, 1963, 52 elementary schools had no Negro teachers

on their staffs. 10 of these 52 schools which acquired no

Negro teachers before October, 1963, expanded their faculties

by a total of 33 additional teachers between March and Oct

ober, 1963.

In the 4 new schools with predominantely Negro student

bodies, a total of 144 teachers were placed. 79, or about

50% of these 144 teachers were Negro teachers.

In the 3 new schools with almost completely white student

bodies, 104 teachers were assigned. Only 5 of the 104

teachers were Negro teachers. . .

15. On SEpteraber 18, 1964 , Judge Kaess entered "Interim

Findings" in Sherrill School Parents Committee, et al., v . The

Board of Education of the School District of the City of Detroit,

Civ. No. 22092 (E.D.Mich.), recommending, inter alia, that

The Board should commit itself to the immediate and

substantial reduction of the number of schools in

which there are no Negro teachers and other professional

personnel. Substantial integration of faculty and pro

fessional personnel should be chievocl in al schools by

the beginning of February, 196 term. [P.X. 6].

10

16. In 1968 the Board-appointed High school Study Commission

examined, among other things, the racial composition oi uhe

faculty at two black (Central and Northv/estern) and two white

(Cody and Bedford) high schools. In The Report of the Hign Scnool

Study Commission (P.X. 107), the Subcommittee on Personnel,

chaired by Deputy Superintendent Authur Johnson, found, witn

regard to these four high schools, that

The percentage of Negro teachers, while

being very low in the "fringe" schools,

approaches 50 per cent in the two "inner"

schools. The percentage of Negro teachers

corresponds to the Negro population of the

student body.

[P.X. 107 at 294]. The Commission also found that "more experienced

and older teachers are found in the fringe schools then in the

inner schools" and that "[t]he« inner schools tend to have a

larger percentage of relatively inexperienced, young teachers."

[P.X. 107 at 298].

17. Yet, this discriminatory pattern of faculty assignment

persists at the present time. During the 1970-71 school year

disproportionate numbers of black teachers were assigned to

predominantly black schools and disproportionate numbers of white

teachers were assigned to predominantly white schools; the pre

vailing pattern of assignment is that the percentage black of

school faculties substantially correlates with the percentage

black of student bodies. [P.X. 154C; Joint X. FFFF-y 15 Tr. 1611-21,

2/

by defendai

Joint Exhibit FFFF was prepared and marked for identification

Board, but made a joint exhibit when plaintiffs noted

it and offered it. [40 Tr. 4613]. The exhibit shows a high corre

lation between percentage black of faculties and percentage black

of pupils in each school.

#

22 Tr. 2506-18 (Foster); 33 Tr. 4340(Johnson); see Finding 7 ,

supra; P.X. 161A-C, 162/i-C, 165/v-C, 166 (hourglass) ; 16 Tr.

1805 " 1 0 1• As Deputy Superintendent Johnson testified, this

persisting racial pattern of faculty assignments "is the result

of discrimination." [38 Tr. 4340].

18. Additionally, ESRPs continue to be assigned more heavily

to black schools than to white schools and teachers in the lower

salary classes are disproportionately placed in black schools,

whilte white schools are assigned a disproportionate number of

teachers in the higher salary classes. [P.X. 161A-C, 162A-C;

16 Tr. 1779 - 91 ] .

19. Thus, the range of faculty distribution factors, including

race, qualifications and experience, continues to reflect a

discriminatory pattern.

B. Pupils

20. In 1962 the EEO Committee found (P.X. 3 at 61):

Numerous public schools in Detroit are

presently segregated by race. The allegation

that purposeful administrative devices have

at times been used to perpetuate segregation

in some schools is clearly substantiated.

It is necessary that the Board and its

administration intensify their recent efforts

to desegregate the public schools.

This finding is substantially corroborated by the evidence and

defendants have failed to present any compelling justification

for the policies and practices set forth below which had natural,

probable and actual segregafory effects.

12

21. An assistant superintendent, Charles WElls, testified

from the minutes of the EEO committee (P.X. 105 at p. 478) with

respect to a letter presented to the Committee by the Citizens'

Association for Better Schools (of which Mr. Wells was a member)

at an EEO meeting in 1960 attended by Mr. Wells, lifter outlining

the hopes and dre£ims of equal educational opportunities of Detroit'

black citizens, particularly the hopes inspired by the favorable

millage vote in 1959, the Association stated:

Their [black people] first disillusionment occurred only

a few months, but yet a few weeks after the passage of the

millage •— they were rewarded with the creation of the

present Center District. In effect this District, with a

few minor exceptions, created a segregated school system.

It accomplished with a few marks of the crayon on the map,

the return of the Negro child from the few instances of

an integrated school exposure, to the traditional predomi

nantly uniracial school system to which he had formerly

been accustomed in the City of Detroit . . . . [Protestations]

resulted in only rationalizations concerning segregated

housing patterns, and denials of any attempts to segregate.

Wnen it was pointed out that regardless of motivation,

that segregation was the result of their boundary changes,

little compromise was effected, except in one or two

instances, where opposition leadership was most vocal and

aggressive.

[20 Tr. 2245-46]. These charges, joined in by Mr. Wells, were

supported with statistical data showing the disproportionate

size, inferior facilities and unequal resources relegated to the

Center District. [See generally 20 Tr. 2243-52]. The Center

District exemplified "a policy of containment of minority groups

within specified boundaries." [20 Tr. 2247-48]. Its boundary line

was described as "look[ing] like the coastline of the Eastern

United States wher the Negro population is on one side and the

white populatio on the other." [20 Tr. 2255] . 'This testimony is

supported by the evidence in the record and was in no way questioned

by the defendants.

22. Deputy Superintendant Johnson acknowledged that there

had been discriminatory practices and that "we still live with

the results of discriminatory practices." [38 Tr. 4347].

23. During the decade beginning in 1950 the Board created

and maintained optional attendance zones in neighborhoods under

going racial transition and between high school attendance areas

of opposite predominant racial compositions. [32 Tr. 3420-21,

3423-28(Henrickson); 13 Tr. 1396-98, 1406-78(Foster); 1 Tr. 28-32

(Former Board President Stephens]. In 1959 there were 8 basic

optional attendance areas [P.X. 109A (1959-60 overlay)] affecting

21 schools.-/ [P.X. 155A at p. 44; 15 Tr. 1667, 1677(Foster)].

The natural, probable and actual effect of the e optional zones

was to allow white youngsters to escape identifiably "black"

schools. [13 Tr. 1478-34, 15 Tr. 1677(Foster); 32 Tr. 3421,

3423-28(Henrickson); P.X. 132; P.X. 109A-L, 78A-L, 136B and 136C].

-J Optional attendance areas provided pupils living within

certain elementary areas a choice of attendance at one of two high

schools. [32 Tr. 3420]. In addition there was at least one optional

area either created or existing in 1960 between two junior hign

schools of opposite predominant racial components. [13 Tr.

1474-78; 11 Tr. 1234]. All of the high school optional areas,

except 2, were in neighborhoods undergoing racial transition

(from white to black) during the 1950s. The two exceptions were;

(1) the option between Southwestern (61.6% clack in 1960) and

Western (15.3% black); (2) the option between Denby (0% black) and

Southeastern (3 .9% black). [P.X. 1287,]. With the exception of

the Denby-Southeastern option (just noted) all of the options

were between high schools of opposite predominant racial compo

sitions. The Southwestern-Western and Denby-Southeastern optional

areas are all white on the 1950, 1960 and 1970 census maps. [P.X.

136A-C, 109/;]. Both Southwestern and Southeastern, however, had

substantial white pupil populations, and the option allowed

whites to escape integration. [13 Tr. 1454-63, 1463-74].

14

[There had also been an optional zone (eliminated between 1S56

and 1959, 32 Tr. 3385) created in "an attempt acted out . . . to

separate Jews and Gentiles within the system" (26 Tr. 2322), the

effect of which was that Jewish youngsters went to liumford High

School and Gentile youngsters went to Cooley (32 Tr. 3384) . See

also Drachler Deposition de bene esse (6/28/7lXat pp. 36-37].

Although many of these optional areas hao. served their purpose

by I960—^ due to the fact that most of the areas had become

predominantly black [P.X. 136B(1960 census map)], one optional

area (Southwestern—Western affecting Wilson Junior High graduates)

continued until the present school year (and will continue t,o

effect 11th and 12th grade white youngsters who elected to escape

from predominantly black Southwestern to predominantly white

Western high s c h o o l ) [32 Tr. 3425-27; P.X. 132, 138]. i<r.

Henrickson, the Board's general fact witness who was employed in

— Mr. Henrickson admitted, however, tnat even in 1959 some of

the -optional areas "can be said to have frustrated integration cmd

continued over the decade." [32 Tr. 3421].

§/ The Board had eliminated the other optional areas by 196d

___ .... . , i _ t___ ___ r. I'Ji nf

(p .: 109G). With regard to two such areas (Sherrill and nter-

halter-McKerrow) the effect by 1960 was that blacn students were

electing to attend white high schools. In botn instances the

Board initially proposed to eliminate the optional area by

including it in the black high school zone. Botn proposals

resulted""in community opposition and one resulted in the

Sherrill School lawsuit. [20 Tr. 2256-57(Wells)].

15

E

1959 to, inter alia., eliminate optional areas, noted in 1967

that: "In operation Western appears to be still the school to

which white students escape from predominantly Negro surrounding

schools." (32 Tr. 3390; P.X. 133 at p. 12). The effect of

eliminating this optional area (which affected only 10th graders

for the 1970-71 school year) was to decrease Southwestern from

C / 1 /86.7% blade in 1969 to 74.3% black in 1970.— (P.X. 128B].—

24. The Board, in operation of its transportation to

relieve overcrowding policy, has admittedly bused black pupils,

past or away from closer white schools with available space to

black schools. [32 Tr. 3405-06, 3413-15, 3856-63, 3872-78;

14 Tr. 1489-1507; 15 Tr. 1621-42; 20 Tr. 2253] This practice

_/ The effect, in numbers, was that some 300 white pupils who

had been escaping Southwestern throughout the decade were now

required to attend a predominantly black high school. The

elimination of this optional area was part of the Board's

April plan: "The changes [under the April 7 plan] affect 18

junior high school feeder patterns out of 55 and wi11 influence

12 senior high schools.' The changes on the sheet, indicate all

graduates from Wilson will be going to Southwestern. . . ."

[D.X. F, Board Minutes of April 7, 1970 at p. 504 (Drachler's

presentation of the April 7 plan)].

— The Board failed to present any valid, not to mention com

pelling, justification for its optional attendance policy and

practice. Dr. Foster found no valid administrative reasons for

creation or maintenance of any of the optional areas. [13 Tr.

1406-85]. The Board spent much time talking about the relative

capacities of the various high schools involved in options.

Even if there were capacity problems, this is an insufficient

administrative justification, for it is clear that capacity

problems are more easily and predictably eliminated by estab

lishment of firm attendance boundaries, rather than the use of

the more unpredictable technique of creating options.

16

M

has continued in several instances in recent years despite the

Board's avowed policy, adopted in 1367, to utilize transportation

to increase integration. [10 Tr. 1133-48, 1150-61; 11 Tr. 1187-90,

1198-1202; 32 Tr. 3402; 15 Tr. 1629, 1633-41; Drachler deposition

de bene esse at 50-51]. Even when the Board, prior to 1962,

bused black pupils to white schools, it did so under its 'intact

busing" (busing by grade, class and teacher) practice which kept,

black youngsters segregated in the receiving schools. [8/28/70

Tr. 140-41; P.X. 3 at 62; 15 Tr. 1622-24]. These practices had

natural, probable and actual segregatory effects and denied

black children equal educational opportunities. [38 Tr. 4347

(Johnson)].

25. With one exception, (necessitated by the burning of a

white school), defendant Board has never bused white children to

predominantly black schools.—^ [32 Tr. 3403(Kenrickson); 20 Tr.

8a/1401(Kennedy)].

—/ One of the most flagrant discriminatory uses of busing occurred

in the transportation, from 1955-1962, of black junior high pupils

from the black Jeffries public housing project to black Hutchins

Junior High in another high school constellation, rather tnan

allow them to walk across the street to the majority white

Jefferson Junior High. Although Jefferson Junior High was at

capacity, the Board could have assigned white students from the

Tildcn Elementary area in the northern-most part of the Jefferson

zone (and much closer to Hutchins than Jefferies project) to

Hutchins, thereby making available space for the Jeffries project

youngsters at Jefferson. [P.X. 10911 (small overlay); 14 Tr.

1489-1507(Foster); 32 Tr. 3407, 3872-73(Hcnrickson)].

8a/ The Board has persisted in refusing to bus white pupils to black schools

despite the enormous amount of space available in inner-city schools. [35

Tr. 3901-07; P.X. 181 (small under capacity overlay)]. There are 22,961

vacant seats in schools 90% or more black. [P.X. 131].

17

26. Prior to 1966 defendant Board operated under an open

enrollment policy, which permitted any pupil to transfer to any

school in the system with available space. [8/27/70 Tr. 50-52

(Drachler); 15 Tr. 1644-54 , 22 Tr. 2519-20 (Foster); 35 Tr.

3910-11(Henrickson)]. On September 18, 1964, Judge Kaess entered

,!Interim Findings" in Sherrill School Parents Committee, et aL,.

v._ The Board of Educ. of the School District of th^_City_of

Detroit, Civ. No. 22092 (E.D.Mich.), concluding, inter alia,

that:

The present "Open School" program does^not

appear to be achieving substantial stuaent

integration in the Detroit Scnool System

presently or within the foreseeable futur>~.

Accordingly, the Board should commit itself

to devise and propose other methods of

speeding up the racial integration oj.

students. The goal should be the achieve

ment of substantial student integration in

all High Schools and Junior High Schools

by the beginning of the February, 1965

term. [P.X. 6]

The Board, with one member dissenting, expressed complete agree

ment with these findings on April 20, 1965. [P.X. 6A]. Yet xt

was not until September, 1966, that the open enrollment policy

was modified to require that any transfer thereunder have a

favorable effect upon integration at the receiving school. [3d

Tr. 3910; P.X. 133 at 9 and 11]. Although some black pupils had

elected to go to predominantly white schools, "the greater effect,

of the policy to that date [September, 1966] had been to draw

white students away from inner city schools." [P.X. 138 at 11;

35 Tr. 3910-11]. Even under the post-1966 policy the favorable

effect on integration has been negligible, with some black students

IB

continuing to elect predominantly white schools, but almost no

white students opting for predominantly black schools. [32 Tr.

3411; 35 Tr. 3913-14; 13 Tr. 1401]. The policy continues to focus

on the receiving school and permits white students to transfer

from black schools to schools which are less black. [20 Tr.

2190-92; 13 Tr. 1401]. Furthermore, pupil transfers for obviously

racial reasons have been and continue to be regularly allowed.

[17 Tr. 1870-72, 1881-1900(Edmundson); P.X. 168; 32 Tr. 3388-91

(Henrickson); P.X. 138 at pp. 2 and 12].

27. The Board has created and altered attendance zones,

maintained and altered grade structures and created and altered

feeder school patterns in a manner which has had the natural,

probable and actual effect of containing black and white pupils

in racially segregated schools. [14 Tr. 1489 to 15 Tr. 1610,

1680-81(Foster)]. The Board admits at least one instance

(Higginbotham) where it purposefully and intentionally built and

maintained a school and its attendance zone to contain black

students. [35 Tr. 3926(Henrickson); 20 Tr. 2253-50(Wells);

14 Tr. 1523-26(Foster)]. Numerous similar examples have been

presented, and the Board has failed to carry its explanatory

burden.--^ And even next year the Board plans on removing the

As long ago as 1967 IJr. Henrickson pointed out various obvious

examples (e.g. , Burton-Franklin area; Wilson-Mcllillan Junior High

area) where boundary lines separated white and black school zones

which could easily be integrated by simple boundary line revisions.

[32 Tr. 3435-40; accord 14 Tr. 1507-11, 15 Tr. 1699-1707(Foster)].

The Board has changed the Vandenburg-Vernor (14 Tr. 1513-1518),

Jackson Junior High (14 Tr. 1534-36), Davison-White (15 Tr. 1590-95)

Parkrnun (15 Tr. 1596-1601), Sampson (15 Tr. 1600-10) and other

zone lines and feeder patterns in a manner which has created and

/

10

last predominantly white elementary school (Ford) from the blacx

Mackenzie high school feeder pattern, the only justification being

that the regional board so willed. [32 Tr. 3417(Henrickson)].

Even in two of the 8 changes (including elimination of 3 optional

areas) during the decade which the Board points to as improving

integration, subsequent changes negated or modified the meager

r e s u l t s . [35 Tr. 3863-71 (Henrickson) ] . Throughout the last

9/ continued. . .

perpetuated racial segregation in the schools. [15 ir. 1680].

The Board has created and maintained the Higginbotham (14 Tr.

1513-18), Hally (14 Tr. 1528-29), and Northwestern-Chadsey

(15 Tr. 1603-08) attendance areas in a segregatory manner.

Defendants respond to these and similar examples generally ay

pointing out capacity problems and the desire to maintain

articulated feeder patterns. These proffered justifications are

unconvincing, if for no other reason because of the inconsistency

of their application. For example, the Board attempts to justify

the removal of the white Parkman elementary from the black

Mackenzie High feeder pattern by pointing out that the receiving

white high school (Cody) was much less overcrc ned than

Mackenzie. Yet, at the same time Cooley (predom'.nantely black)

was similarly less overcrowded than white Bedford, but the board

made no change in the feeder patterns. [32 Tr. 3415-19]. Tne

articulated feeder pattern'principle has not been, nor is it now,

a valid justification for maintaining or failing to alleviate

segregation. This principle was violated in feeder patterns such

as the Custer in 1959-61 (35 Tr. 3865-67) and the Davison in

1969-present (35 Tr. 3368-71), which had the effect of creating

and perpetuating segregation. And the concept was wholly

disregarded in the feeder patterns proposed in tne April 7 plan.

[35 Tr. 3853-56(Henrickson)].

10/

to

The two negative changes were the return of

the black Central High feeder pattern (35 Tr.

black Custer

3865-63, 3871-72)

and the return of black Davison from the white Osborn feeder

pattern to the predominantly black Pershing feeder pattern.

[35 Tr. 3868-71].

f

20

decade (and presently) school attendance zones of opposite racial

compositions have been separated by north-south boundary lines,

despite the Board's awareness (since at least 1962) that drawing

boundary lines in an east-west direction would result in signifi

cant integration. [P.X. 105 at p. 450(Minutes of EEO Committee);

Drachler deposition de bene case at 156-77; 11/4/70 Tr. 38(Drachler);

35 Tr. 3853-56(Henrickson); P.X. at 7; 15 Tr. 1699-1707(Foster)].

And although the Board was specifically aware, since at least

1967, of contiguous attendance zones which could be paired or

altered to accomplish integration, it has failed to act. [32

Tr. 3435-40; P.X. 138]. The natural and actual effect of these

acts and failures to act has been the creation and perpetuation

of school segregation.

28. There has never been a feeder pattern or zoning change

which placed a predominantly white residential area into a pre

dominantly black school zone or feeder pattern. [32 Tr. 3404] .

29. Every school which was 90% or more black in 1960,

and which is still in use today, remains 90% or more black

[P.X. 150; 32 Tr. 3381-82].

30. Whereas 65.8% of Detroit's black students attended 90%

or more black schools in 1960, 74.9% of the black students attended

90% or more black schools during the 1970-71 school year. [P.X.

129; 32 Tr. 3332].

C. School Cons I- ion

31. Between 1940 and 1953 the Board constructed 36 new

elementary schools and 4 new high schools, and additions to 55

elementary schools, 1 junior high school and 3 high schools, for

a total additional capacity sufficient to house 69,000 students.

[33 Tr. 3507-03; P.X. 101 at p. 233]. The new school construction

during this period was located largely in accordance with general

site designations set forth in the Detroit Master Plan of 1946,

which was developed by the City Plan Commission in conjunction

with school authorities. [33 Tr. 3509-10, 3513-14].

32. in 1953 Board-appointed Citizens Advisory Committee on

School Needs pointed up inadequacies in school plant facilities.

[P.X. 101]. in 1959 the Board designated a $90 million dollar

nuilding program; $30 million came out of the millage package

and the remaining $60 million from the first bond issue the Board

had ever placed before the public. [Drachler deposition de bene

essee (June 23, 1971) at p. 25]. The 1959 building program was

specified in a "priority list" of projects; this list was trans

mitted by the school authorities to the City Plan Commission which

resulted m joint conferences between these tv/o agencies and other

ci-cy agencies, such as the Department of Parks and Recreation, for

the purpose of determining site locations. [33 Tr. 3515(Henrickson)]

Many of the proposed attendance areas were designated in 1959 and

specific site locations were thus determined within the confines

of tne established attendance areas; by 1962 all attendance areas

and site expansions were designated for the school construction

proposals on the 1959 priority list and published in The Price of

^ellcnce (P.X. 72A) . [35 Tr. 3891-92 (Henrickson) ] Many of these

attendance areas were drawn in such a manner that tne Board knew

or snould have known that the schools, when constructed, would

open as segregated schools. [15 Tr. 1682-98]. For example:

22

(a) The 1959 building program included a replacement for

Eastern High School, which was constructed prior to the

turn of the century. The Price of Excellence (P.X. 72A-

map folowing p. 105) reveals that the attendance area

would remain the same(except that portion north of Mack

to be included in Kettering) for the new high school

which was designated to be built some 1-2 miles southwest

of the old school. [See also D.X. Y]. The 1960 census

map (P.X. 136B) reflects that the proposed attendance

area encompassed a residential section of the City which

was overwhelmingly black, although there were substantial

areas of white population immediately to the east and

west of the proposed attendance areas. The 1960-61

racial count (P.X. 100A) reflects that old Eastern High

enrolled 2290 black and only 151 white students that

school year. The new Eastern was constructed around the

middle of the decade and it was renamed King High School

in 1963. Since the 1960-61 school year the school (old

and new) has never enrolled over 50 white students (P.X.

100A-J), and this past 1970-71 school year the school

enrolled only 3 white pupils out of a total enrollment

of 1,878. [P.X. 1C0J]. The inescapable conclusion is

that the Board knew, or failed to know only through

wilful ignorance, that they were building a segregated

23

11/black high school. [See generally 35 Tr. 3391--95] .

(b) Kettering was another high school proposed in the 1959

building program. The Price of Excellence (P.X. 72A-map

following p. 134) and Defendants' Exhibit Y show that

the designated attendance area included the northern half

of the Northeastern High zone and the northern portion

of the Eastern High zone. The 1960 census map (P.X.

136B) reveals that the portion of Northeastern to be

included in the Kettering zone was about evenly devided

between black and white residences, and that the portion

of Eastern to be included in the Kettering zone was

overwhelmingly black in population. The proposed zone

did not encompass, as it easily could have, the

Southern portion of the white Osborn High school area.

[See P.X. 136B(census map) and 109A(overlay)]. The

1960--61 racial count (P.X. 100A) reflects that North

eastern enrolled 437 white and 1648 black students

that school year, while Eastern had only a handfull of

white students, as previously noted. Even if all of

the Northeastern white students lived in that portion

of the zone to be included in the Kettering zone, it is

— The Board's only response to this compelling set of

circumstances is that there were charges from the black

community in 1960 that the Board was building a new high

school for the whites in Lafayette Park and Elmwood (the

only white residential areas in the Eastern zone). These

charges, howevm , stemmed from the previous experience of

the l tek com lity with the segregation of Hiller High

School (35 Tr. 3882-87 , 3893), an;, do . ot negate the obvious

and predictable results of the Board's actions.

t

clear that there was little likelihood that Kettering

would have a substantial number of white students when

it opened. Although the 1960 and 1970 census maps

(P.X. 136B and 136C) show that about 1/3 of the pro

posed Kettering area encompasses white population

areas, the Board knew that a large portion of the pupil

population areas, the Board knew that a large portion of

the pupil population in this area attended then and now

parochial schools. [35 Tr. 3900-01]. Furthermore, the

Kettering site, designated in 1960 (35 Tr. 3395) was

located in the black population portion of the zone to

the south of the white residential areas, rather than

the center of the zone. [P.X. 72A(map following p. 134)

and P.X. 136B (1960 census map)]. Not surprisingly,

Kettering opened in 1965 with an enrollment of 803

black and only 295 white students. [P.X. 100E]. In

1970-71 Kettering'enrolled 3,372 black and only 38 white

students. [P.X. 100J]. The Board knew or should have

known that the natural, probable and actual effect of its

actions would be the creation of a segregated black high

school. [See generally 35 Tr. 3895-3901]

(c) Finney High School was also constructed pursuant to

the 1959 building program. Its boundary was designated

to encompass an all white population area which was

the northern half of the Southeastern area [D.X. Y(overlay)

P.X. 109A (overlay)]. The attendance zone, as designated,

excluded the black residential areas of the Southeastern

zone. [P.X. 13613] . Finney High opened in 1962 with

an enrollment of 1048 white and only 4 blade pupils,

while Southeastern had an enrollment that school year

of 1436 black and 1220 white students. [P.X. 100B].

Although the original site selection was the Clark

Elementary site, the location was subsequently changed

to place the high school at the existing Finney Junior

High site, even farther from the black population

areas in the Southeastern zone. [35 Tr. 3881-82;

P.X. 72A(map following p. 112); P.X. 136B(census map);

P.X. 109A and D.X. Y]. Although a boundary change in

1967 added black students to Finney High, the school

remains disproportionately white with an enrollment of

1,669 white students and only 973 black students in a

system which i 63.8% black. [P.X. 100J, 152A].

(d) Comparison of the census maps and Defendants' Exhibit AA

(junior high school construction and attendance area

overlay) reveals a similar systematic segregatory

pattern of cons ruction at the junior high level unaer

the 1959 building program. 17 junior highs were con

structed under the 1959 program; the following ta.ole,

taken from Defendants' Exhibit NN, demonstrates the

Board's knowledge of the natural, probable and actual

segregatory effects of this construction:

26

f

Junior High PERCENT BLACK

School (1959 Date When 12 , When

Bldg, program) Opened Authorized— Opened 1970-71

1. Brooks 1962 0.0 0.0 1.5

2. Butzel 1964 88.0 91.3 93.1

3. Condon 1963 90.0 92.7 91.8

4. Earhart 1965 10.0 13.6 8.6

5. Farwe11 1964 30.0 21.8 b / . 8

6. Joy 1964 75.0 92.1 98.8

7. Knudsen 1963 98.0 98.7 98.9

8. Lessenger 1963 0.0 0.0 8.3

9. McMillan 1962 50.0 53.2 48.1

10. Ilurphey 1963 , 0.0 0.7 9.8

11. Pelham 1963 50.0 69.1 99.5

12. Ruddirnan 1962 .5 2.1 19.4

13. Spain 1962 100.0 100.0 100.0

14. Taft 1962 0.0 0.0 0.7

15. Webber 1963 99.0 99.4 99.7

16. Wilson 1963 2.0 1.7 2 • 1

17. Winship 1963 0.0 0.0 / 0.3

Of these 17 junior high s;chools, only 3 (Farwell,

McMillan and Pelham) had designated attendance areas

(see D.X. AA) which were estimated by the Board to be

substantially integrated when authorized in 1959, and

2 of these (Farwe 11 and V.LcMillan) have remained integrated.

Of the remaining 14 junior high schools authorized in

1959, 3 had designated attendance areas estimated by the

Board to be white when authorized and 6 had designated

attendance .areas estimateid by the Board to be black. Each

of these 14 schools, as anticipated, opened as black or

white junior highs, and each has retained its racial

identity to this date. The Board's defense that they

— / The column showing % black when authorized was estimated by

Mr. Henrickson from existing schools in the area at the time

authorized. [30 Tr. 3212].

were surprised and overtaken by population shifts in the

interim period between authorization date and completion

date is not borne out by the facts, nor is it supported

by the Board*s own exhibits, which not only demonstrate

a segregatory construction program but also demonstrate

scienter on the part of the Board. The evidence reflects

long delays between the initial designation of projects

and actual steps toward construction. In such instances

the board was free to change its plans for many reasons

including the demonstrable reason that if built in

particular locations it would be a segregated school.

(e) Defendants' Exhibit Z and the exhibits used in the

foregoing examples, together with the same methods of

comparison therein utilized, reveal the same results

with regard to elementary school construction under the

1959 Building program: The Board, with knowledge of

the natural, probable and actual effects of its actions,

constructed and maintained segregated black and white

elementary schools.

33. In addition to the 84 projects undertaken pursuant to

the 1959 Construction Program (see P.X. 75), the Board has,

during the last decade, undertaken additional construction with

its normal millage authority (recently increased to 5% to equalize

Detroit's capital outlay authority with that of the rest of the

state). [See P.X. 77]. Defendants' Exhibit NN reflects that the

Board has completed construe'ion of and additions to 91 schools

since 1959. According to defendants' own exhj.oit (NM t 48 of

28

these schools were to serve areas which were over 80% black in

pupil population when the construction was authorized, all of

which opened over 80% black and remain so; 14 schools were m

areas over 80% white (by the Board's own estimates) when

authorized, opened over 80% white and have remained so. Plaintiffs

Exhibit 79 shows the construction of 63 new schools since 1960.

44 of these schools opened over 80% black in student enrollment,

and 9 opened less than 20% black. This new school construction

is depicted on overlays (P.X. 153, 153A and 153B); when the

overlays are compared to the 1960 -and 1970 census maps (P.̂ .

136B and 136C) and the percentage black when each school opened

(P.X. 79), it appears beyond peradventure that the Board, with

few exceptions, has knowingly embarked upon and continued a

course of new school construction which had the natural, probable

and actual effect of creating, perpetuating and maintaining

racially segregated schools in Detroit. [15 Tr. 1682-98(Foster);

33 Tr. 3519-21].

34. In 1966 the defendant State Board of Education and the

Michigan Civil Rights Commission issued a Joint Policy statement

on Equality of Educational Opportunity (P.X. 174), requiring tnat

Local school boards must consider the factor of

racial balance along with other educational con

siderations in making decisions about selecuion^

of new school sites, expansion of present facili

ties . . . . Each of these situations presents

an opportunity for integration.

Defendant State Board's ''School Plant Planning Handbook" (P.X. 70

at p. 15) requires that

29

*

Care in site location must be taken if a

serious transportation problem exists or

if housing patterns in an area would resul

in a school largely segregated on racial,

ethnic, or socio-economic lines.

Yet, defendant Board has paid little, if any, hoGd to the

truth of these statements and guidelines, as the foregoing

findings regarding school construction and site location clearly

demonstrate. The State defendants have similarly failed to tc.se

any action to effectuate these policies. [33 Tr. 35221.

Defendants' exhibit NH reflects construction (new or additional)

at 14 schools which opened for use in 1970-71; of these 14

schools, 11 opened over 90% black and 1 opened less than 10% blac!

School construction costing $9,222,000 is opening at Northwestern

High school which is 99.9% black, and new construction opens at

Brooks Junior High, which is 1.5% black, at a cost of

13 /$2,500,000.— [P.X. 151].

35. Since 1S59 the Board, with the obvious knowledge that

small schools ''defeat' the' intended objective of large service

areas with heterogeneous social and racial composition [P..,.

138 at p. 5; 35 Tr. 3909-10], has constructed at least 13 small

primary schools with capacities of from 300 to 400 pupils.

[35 Tr. 3907-08]. This practice negates opportunities to inte

grate "contains" the black population and perpetuates and com

pounds school segregation.

— 7 The construction at Brooks Junior High plays a dual segrega

tor- role- not only is the construction segregated, it will

result°in a feeder pattern change which will remove the last

majority white school from the already almost a

kensio high School attendance area. {3Z ir. ---

number 27, supra].

30

#

36. Furthermore, the Board, through school construction,

has advantaged itself and built upon the racial segregation in

public housing projects (v/hich segregation resulted from the

discriminatory policies and practices of federal and state

housing agencies, see Findings 43 ~ 44__ t infra), by con

structing new schools and additions within or near such segre

gated projects. [P.X. 147, 148, 149; 23 Tr. 2571-76] The

Board knew or must have known that such construction created or

perpetuated school segregation. (See, e.g., school official s

reference to using "colored church" to relieve school over

crowding caused by black housing projects, P.X. 147 at p. 17,

23 Tr. 2574). [See Finding 46; infra]

D. Magnet Plan

37. The integration results predicted for the magnet high school plan

have failed to materialize; the plan has resulted in but a few black

students electing to attend predominantly white high schools and almost no

white students choosing predominantly black high schools. [31 Tr. 3323-46

(Della Dora); 35 Tr. 3912-14 (Henrickson)]. The magnet plan retains too

many of the defects inherent in "open enrollment" and "free choice"

techniques (already proven ineffective in Detroit, see Finding 26, supra)

to have any realistic prospects of achieving substantial desegregation of

Detroit's high schools. [35 Tr. 3910-14 (Henrickson); 15 Tr. 1644-54

(Foster)].

31

E. Alternatives Available

38. The District long has been aware of the racial segregation of pupils

and faculty in the Detroit Public School System. Numerous complaints have

been made to the Detroit Board of Education and its staff to remedy the

situation. Among the examples are the reports of Citizens Association for

Better Schools in 1960 [20 Tr. 2245-2246; P.X. 105 p. 478], the 1962 report

of the Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity [P.X. 3], the Sherrill

School Case [P.X. 6 and 6A], the studies by the Commission on Community Rela

tions in 1963 on continuing discriminatory patterns and practices of the

District [P.X. 177-178]; the joint statement of the State Board of Education

and Michigan Civil Rights Commission in 1966 [P.X. 174], and the report of the

High School Study Commission in 1968 [P.X. 107]. Board minutes are replete with

repeated requests by many individuals and groups, including Plaintiff Detroit

Branch of the N.A.A.C.P., for effective action to eliminate existing segrega

tion. [D.X. RR].

39. Several such complaints suggested reasonable and feasible means of pupil

and faculty assignment which would reduce the substantial racial imbalance;

other proposals to remedy the school segregation were also made. Among the

other examples are Defendant Drachler's acknowledgement in 1961 to the EEO

committee that drawing attendance zones East-West instead of North-South

would effect substantial integration [Drachler Statements, Deposition 6/28/71

pp. 156-157; P.X. 105, p. 405]; the various suggestions by District planner

Henrickson, in 1967 [P.X. 138] , and the various desegregation proposals of a

number of District staff groups in 1970 [P.X. 11-13]. Defendants, including

the State Board of Education, admitted the educational benefit of integration

for both black and white pupils and the denial of equal educational oppor

tunity inherent in existing school segregation [P.X. 174(State Boare); 19

Tr. 2049-2051 (State Beard); P.X. 1 (Drachler Statement)]. As admitted by

defendant Board member Stewart, the District has "a mor-.1 as well as a legal

responsibility to undo the segregation it helped to create and maintain."

32

2350-2353

21 Tr. ____ / [See also admissions of Deputy Superintendent Johnson, 41 Tr. 4334-

4348].

4 0 . The District had the power to and regularly did alter attendance zones,

build new schools and additions, and alter student and faculty assignments.

Yet, with some exceptions, most notably the April 7 plan of partial high

school desegregation, the District has failed to act effectively to end the

prevailing pattern of school segregation because of "imagined or real community

pressures based on race alone." P.X. 3 p. 74 (1962 EEO Report) [See also

P.X. 173 p. 11(Former Board President Grace Deposition, 7/24/64)]. Those

fears of the white community's active hostility to effective action to end the

prevailing pattern of school segregation were born out by the quick response

and recission of the April 7 plan by the State and recall of Board members who

favored that modest start. [41 Tr. 4675 (Drachler)].

33

!

F. School and Residential Segregation

41. The City of Detroit is a community generally divided by racial

lines. Bradley v. Milliken, C.A. No. 35257 (E.D.Mich. Dec. 3, 1970) (Slip. Op. at 3).

Residential segregation within the City of Detroit and throughout the metropolitan

area is substant.i ■ 1 , pervasive and long-standing. The credible evidence in this

cause — exhibits and testimony of expert and fact witnesses — shows that

black citizens have been contained in separate and distinct areas within the

City and largely excluded from other areas within the City and throughout the

suburbs; that pattern and practice persist. [P.X. 184, 2, 16A-D, 136A-C (census

maps);48 (map of racial covenants); 1 Tr. 144 et seq. (Marks); 3 Tr. 342 et seq.

(Taeuber); 2 Tr. 200, et seq., 3 Tr. 398, et seq., 5 Tr. 522 et seq. (Bush) ;

6 Tr. 686 et seq. (Price); 7 Tr. 720 et seq. (Bauder); 7 Tr. 766 et seq. (Tucker);

5 Tr. 591 et seq., 5 Tr. 608 et seq., 5 Tr. 617 et seq., 6 Tr. 630 et seq.,

6 Tr. 636 et seq., 6 Tr. 665 et seq. (Black Real Estate Brokers)] That

evidence stands uncontradicted by the State or any other defendant.

42. Chance, the racially unrestricted choices of black persons, and

economic factors are not now and have never been the major factors in this

pattern of residential segregation; nor is it primarily an ethnic phenomenon.

[1 Tr. 146-148, 150-153, 176-177 (Marks); 3 Tr. 349-350, 357-363, 371-377,

386-389, (Taeuber); 7 Tr. 775-779, 787 (Tucker); P.X. 183B, pp. 1-2]. Rather,

the pervasive residential segregation throughout the metropolitan area is

primarily the result of past and present patterns, practice, custom and usage

of racial disc, imination, both public and private, which now restricts and al

ways has restricted the housing opportunities of black people. [1 Tr. 151-154,

1 6 7 - 1 6 8 (Marks); 3 Tr. 358, 363-364, 373, 386-387 (Taeuber); 7 Tr. 766-767 (Tucker);

7 Tr. 727-28 (Bauder), P.X. 122], As evidenced by the uncontroverted (1) testimony

of officials or former officials from the Detroit Commission on community

Relations (Marks and Bush), Detroit Housing Commission (Price), the Michigan

Civil Rights Commission (Bauder), United States Commissi i on Civil Rights

(Sloane), and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (Tucker)(all of

which are responsible for monitoring and in some instances combatting housing

34

discrimination) (2) probative findings of these agencies and the former

commissioner of the Michigan Corporation and Securities Commission, (3) the

testimony of local black brokers and (4) a variety of documentary evidence,

the collective experience of black home seekers throughout the metropolitan

area always has been and is still largely that of racial discrimination,

restriction, exclusion, and sometimes insult or worse.1— ^ The testimony of

these witnesses is credible, informed and stands unrebutted and uncontradicted

by the State or any other defendant. This proof was properly conceded

by Counsel for the District to be a "tale of horror . . . degradation and de

humanization." 5 Tr. 607 [See also 6 Tr. 672, 680-681 (District); 4 Tr. 505

(Intervening Defendant Detroit Federation of Teachers)].

43. Governmental action and inaction at all levels— federal, state and'

local— is ful1y implicated in the subsidization, development and maintenance of

racial restrictions on housing opportunities and is substantially responsible

for the present residential restrictions and pattern of residential segregation

throughout the metropolitan area. [Tr. 153-156, 177-178 (Marks); 2 Tr. 200,

et. seq. (Bush); 6 Tr. 694-693 (Price); 7 Tr. 766-796 (Tucker); 7 Tr. 722-750

(Bauder); 4 Tr. 445-473, 496-490 (Sloane) ; and P.X. 25 (Report of the Commission

on Community Relation); P.X. 122 (Statement of the Michigan Civil Rights Commis

sion) j p .x . 37 (Report U.S. Commission on Civil Rights); P.X. 38 (Statement

of the Secretary of HUD)]. As. testified by Martin Sloane, Assistant Staff

Director of the United States Commission on Civil Rights, one of the most

formidable factors has been the history of the Federal government's aggres

sive promotion of discrimination and subsidization of new housing, especially

— - In the words of one witness, this pattern of containment "is just as

effective a barrier as if a wall were built in the community." [1 Tr. 163

(Marks)]. This witness then noted that on the edge of an historic black

pocket in the 8 Mile-Wyoming area, a builder, who had title to property adjacent

where these Negroes were living, "actually put up a cement wall, brick, mortar

and brick wall, which for years was a symbol in [Detroit] of the way in

which the Negro was an undesired neighbor." (1 Tr. 163 (Marks); Tr.

(Hendricson)]

in the suburbs, on a racially exclusiv basis. The effects of these

discriminatory policies, and the scope of the activity of F.H.A. and later

V .A . [4 Tr. 445-456, 490-494, 496-498(Sloane)], on the present location

and racial occupancy of housing throughout the metropolitan area, particularly

in subdivision development, affixed a pattern of racial separation which was

closely conjoined with new school construction within the City and the

white bedroom communities of the suburbs Present governmental inaction

has failed to reverse this pattern of housing discrimination and segregation

which it did so much to create and now perpetuates by failing to exercise

its power. [P.X. 184 (census map); P.X. 37, 57(Statements of U .S.Commission on

Civil Rights); P.X. 38(Statement of Secretary of HUD); P.X. 183A pp. 5-6

(Plaintiffs' Answers to Requests for Admissions); 4 Tr. 453-455, 496-498

(Sloane)].

15/— In building racially exclusive communities for the outmigration

of whites, "white" schools were a necessary precondition to "stable"

and "desireable", i.e. white, neighborhoods in the formerly stated view

of the F .H.A.:

"Of prime consideration to the Valuator is the presence or lack

of homogenity regarding types of dwellings and classes of people living

in the neighborhood....Distances to the schools should be related to

the public or private means of transportation available from the location

to the school. The social class of the parents of children at the

school will in many instances have a vital bearing.... Thus...if the

children of people living in' such an area are compelled to attend

school where the majority or a good number of the pupils represent a

far lower level of society or an incompatible racial element, the

neighborhood under consideration will prove far less stable and desire-

able than if the condition did not exist. In such an instance it might well

be that for payment of a fee, children of this area could attend another

school with pupils of the same social class." [P.X. 56B, 1936 F.H.A. Manual

§§ 252, 265, 266]

"PROTECTION FROM ADVERSE INFLUENCES... Important among adverse influences

[is] infiltration of inharmonious racial or nationality groups. [P.X. 56,

1935 F.H.A. Manual S§ 310]

"Protection from Adverse Influences . . . . Recorded restrictive covenants

should strengthen and supplement zoning ordinances and to be really effective

should include... [p]rohibition of the occupancy of properties except by the

race for which they are intended." [P.X. 56 A, ?,938 F.H.A. Manual, § 980 (3) (g)

36

44. The City of Detroit, with the assistance of federal agencies, built

and maintains public housing on a racially segregated basis [1 Tr. 156 (Marks)

7 Tr. 781 (Tucker); 4 Tr. 457-459, 463-464 (Sloane); P.X. 18A (Public Housing

Occupancy Statistics by Race, 1951-1971; 6 Tr. 697 (Price)] . Until declared

unconstitutional by this federal district court in 1954, Detroit maintained

segregation as an official policy: tennants were assigned on a racial basis

and projects located so that existing racial characteristics of any area would

be maintained. [1 Tr. 156 (Marks); 2 Tr. 221, 226, 247, 254-256, 263-265(Bush);

(Detroit Housing Commission Exhibits: P.X. 17; 18B p. 1; 19 Annual Report 1935,

p. 10; Annual Report 1943 p. 9; Annual Report 1945, p. 29) 6 Tr. 697 (including

urban renewal) (Price)]. Racially discriminatory tennant assignment practices

continued through 1968 [6 Tr. 697-698 (Price); 7 Tr. 781-786 (Tucker); 2 Tr.

284, 291-292, 5 Tr. 589 (Bush);P.X. 18A p.32; P.X. 21 — . 25-35 (1959 Study

of Tennant assignment)]. The policy of modified free choice then adopted has

not been effective in desegregating projects originally designated for black

occupancy. [P.X. 18B, pp. 15-18 (Tennant Assignment Policy 1/2/69);7 Tr.

781-786 (Tucker)]. They r>' aain virtually all black [P.X. 18A p. 3; 2 Tr. 297].

The discriminatory practice of locating projects persists. There has been a

continuing pattern of rejection’of proposed public housing projects which are

feared to be open to tennants of all races and located in white areas of the city.

[1 Tr. 177-178 (Marks); 1 Tr. 266-274, 2 Tr. 293-307,(Bush); 6 Tr. 706-708 (Price)].

As a result since 1954, there has been very little construction of additional

public housing [P.X. 18A; 6 Tr. 706 (Price^ all of which has been located

in black or changing areas. [1 Tr. 178 (Marks); P.X. 23 (Map of public housing

constructed and rejected); 7 Tr. 731-732 (Bauder); P.X. 123 (Statement of the

Michigan Civil Rights Commission to the Detroit Common Council, 3/30/70)].

This continuing pattern of government action and refusal to act contributes

substantially to the pervasive residential segregation. [1 Tr. 155-156, 177-178

(Marks); 4 Tr. ' 7 (Sloane); 7 Tr. 743-744 (Bauder); 7 Tr. 779 780 (Tucker)].

37

For a long period the affirmative policy of the major associations

of white real estate agents to exclude blacks from white neighborhoods [P.X. 60

p. 5, 6 Tr. 643 (Real Estate Codes of Ethics)] was explicitly sanctioned by the

16/State agency responsible for licensing and regulating real estate agents

[P.X. 59 pp. 22, 25; 5 Tr. 525] and openly promoted and subsidized by the

F.H.A. and other federal agencies [P.X. 56, 56A, 56B (F.H.A. manuals); 4 Tr.

445-452 (Sloane); 6 Tr. 705 (Price); 7 Tr. 767, 770 (Tucker)]. By policy and

practice various banks and lending agencies, chartered and regulated by state or

federal agencies, financed residential choices to preserve and build racially

homogeneous neighborhoods [6 Tr. 702-705 (Price); 4 Tr. 464-467 (Sloane)].

Racially restrictive covenants, long enforceable in State court, effectively

excluded blacks from all but a few areas in the City and suburbs identified

for open and black occupancy; these covenants helped establish a pattern and

17/practice of racial containment and exclusion which persist. [P.X. 48, Tr.

235-238 (map of restrictive covenants); P.X. 48A and Tr. 186-196 (Affidavit and

testimony of Chief Title Officer of Burton Abstract and Title Company, Parmalee v

Morris, 218 Mich. 625 (1925), Northwest Civic Association v. Sheldon, 317 Mich.

416 (1947, Sipes v. McGee, 316 Mich. 614 (1947, rev'd 334 U.S. 1 (1948); 1 Tr.

153-154 (Marks); P.X. 2, 16A-D, 184 (census maps); 7 Tr. 778-779, 796

(Tucker)]. The pattern of racially discriminatory marketing practices in

the organized real estate industry, although possibly less rigid and

openly stated then in the past, persist and are still effective. [1 Tr.

154 (Marks); 3 Tr. 363 (Taeuber); 5-6 Tr. passim (Real Estate

— After hearings and investigations in 1961 Commissioner Gubow attempted

to halt the pervasive discriminatory practices of its licensed real estate

brokers which Commission policy had previously helped develop and maintain.

Thai. effort was frustrated by act of a superior state agency. (P.X. 183A-G)

17/— Restrxctive covenants continued to be included in the abstracts and title in

surance policies of the largest title company in the Detroit metropolitan area be

cause of its opinion that they had some continuing effect until Jones v. Mayer,

392 U.S. 409 (1968); upon a request by the Justice Department on November 26, 1969

made pursuant to Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the title company

began eliminating such restrictions from all policies and commitments. (P.X. 48A;

2 Tr. 196].

38

Brokers)], By credible and uncontroverted evidence in this record, both

past and present mechanisms of housing discrimination have been described and

18/documented. [1 Tr. 152-153 (Marks); 3 Tr. 363, 386, 391 (Taeuber); 7 Tr.

768-770 (Tucker); 5 Tr. 531-534, 536-568 (Bush); P.X. 24 (harassment); P.X. 27-29

(advertising); P.X. 25; 5-6 Tr. passim]. The understatement of one young black

broker, who works on behalf of black clients who seek better housing which happens

to be located in white residential areas, describes the current situation: "I

do it only on bright days when I have good shoes because there is a great deal

19/of hostility in the white areas." Tr. 671.

46. The defendants had full knowledge of this situation. From 1943

until his employment by the District in 1959, the chief school planner, Mr.

Hendrickson, was employed by the Detroit City Plan Commission and worked on the

master plan which, with modifications, is still in effect and included generally

existing and proposed school locations. [33 Tr. 3507-3513 (Hendrickson)]. The

District acts jointly with city planning officials, public housing authorities,

and federal agencies in the acquisition and sale of land and location and con

struction of schools, [P.X. 147-148; 167; 19, Detroit Housing Commission Annual

Report 1942, p. 37; 33 Tr. 3514-3518 (Hendrickson)]. The State Board of Education

and Michigan Civil Rights Commission directed that school authorities in their

school construction and student assignment practices avoid imposing segregation

in the schools. [P.X. 174]. Yet, the District, with the sanction of the defendant

State Board of Education and support of State bonding authority, built upon

and advantaged itself of the pattern of residential segregation to create,

18/— The discriminatory mechanisms of the organized real estate market operate to

restrict the choices of whites as well as blacks. Whites and blacks are sorted

and separated, guided by the real estate industry on a racial basis to different

residential areas in the metropolitan area. [1 Tr. 146-148, 151, 170 (Marks);

5 Tr. 548, 557-558, 582 (Bush)].

19 /— Another older black broker testified movingly about the long history of dis

crimination he and his clientele experienced, his own recent difficulties in pur

chasing a home for his family in the suburbs, and his decision to stop attempting

to seek homes for black persons in white areas: "I've been licked, and I just don't

like wasting my time and my effort. And, I don’t like taking people, like a Doctor

I took out in Livonia...able to buy and pay cash for a piece of property. And

walk to the door and the man is there. And when you start to go in, he comes out,

closes the door and said "we're closed!... I told you we're closed!"

"And this kind of thing was not bad for me because I'm immune to it, but

it was so embarrassing to [the Doc Lor]." 5 Tr. 604-605

39

maintain, magnify, and perpetuate pupil and faculty segregation in the public

schools as set forth more fully in findings 1 to 36 supra. For

examples, as the major area of black containment expanded West (after a

decision by white realtors to open the area) in a pattern of neighborhood

succession from Woodward to Livernois to Greenfield [P.X. 2, 184, 16B-D, 136A-C

(census maps); 1 Tr. 147-148, 170 (Marks); 3 Tr. 364-370 (Taeuber); 5 Tr. 569

(Bush); Tr. (Hendrickson)], school boundaries were either altered, [see

21,27

finding §/, supra], made optional zones [see finding 23 supra] , or maintained in

a generally North-South direction [see finding, 27 supra]. Such actions had the

natural, probable and actual affect of maximizing school segregation and identifying

20-30schools as "black" or "white". [See Findings /supra]. For example, defendant^

built and maintained Higginbotham as an admittedly "black" school for residents

20/of an historic black pocket in the 8 Mile-Wyoming area: [See Finding 27 supra].

The Higginbotham school boundaries were built upon the actual physical barriers

erected by neighboring whites intent on keeping blacks out. [See Findings 27,42

supra]. By various assignment, transfer and transportation practices, Higgin-

24 27botham has been kept a "black"school. [See Findings* /supra]. As examples,

many schools were built for public housing projects designated "black" or

"white"; sometimes these schools were located on the site of the public housing

project. [P.X. 147-148; 19, Detroit Housing Commission Annual Report 1942,

pp. 32, 37; and see finding 36 supra]. By various student and teacher

assignment, transportation and transfer practices, many of these schools were

opened and thereafter maintained as "black" or "white" schools. The original

"black" housing projects, and their schools, remain virtually all black, the

result of past and present discriminatory practices. [P.X. 149].

20/ That pocket had been built up by temporary war housing [P.X. 19, Detroit

Housing Commission Annual Report 1943, p. 71], designated for black occupancy,

and extended beyond the City limits into Oakland county and the old, almost

all-black Carver School District. [P.X. 184 (census map); Drachler depositions,

3/31/71 p. 13, 6/28/71 p.48]. The small Carver school dis rict lacked high school

facilities. The District accomodated these students by busing them past "white"

schools to "black" schools in the inner city. [8 Tr. 885 (Green); 11 Tr. 1259-60

(1959 Boundary Guide Book); Drachler depositions, 3/31/71 p. 13, 6/28/71 p. 48].

The Carver school district finally was split and merged into the Ferndale School

District and Oak Park School District. [Drachler Deposition 3/31/71 p. 13; P.X.

184 (census map); P.X. 185 (Summary of Suburban Schools)]. In these districts

at the elementary level in the 1968-69 school year, the students from this still

black residential pocket [P.X. .184 (census map)] were assigned to two virtually

all black schools. [P.X. 185 (Summary of Suburban Schools)].

Indeed, identifiably "white" schools often were constructed and main

tained on lands with covenant restrictions against Negro use or occupancy; and

in one instance at least in 1954, such racial covenant was continued pursuant

to a special agreement between the seller of the land and purchaser Detroit

Board of Education. [See generally, 20 Tr. 2164-2176; P.X. 172, 172W, 172A-Z].

This record shows many other examples of defendants' pattern and practice of