Earle v. Greenville County Memorandum on Behalf of Respondent, Tessie Earle

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Earle v. Greenville County Memorandum on Behalf of Respondent, Tessie Earle, 1949. 3feea667-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/44e7d7fc-d2c6-4456-b638-ffbd1c24ebec/earle-v-greenville-county-memorandum-on-behalf-of-respondent-tessie-earle. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

fL-c

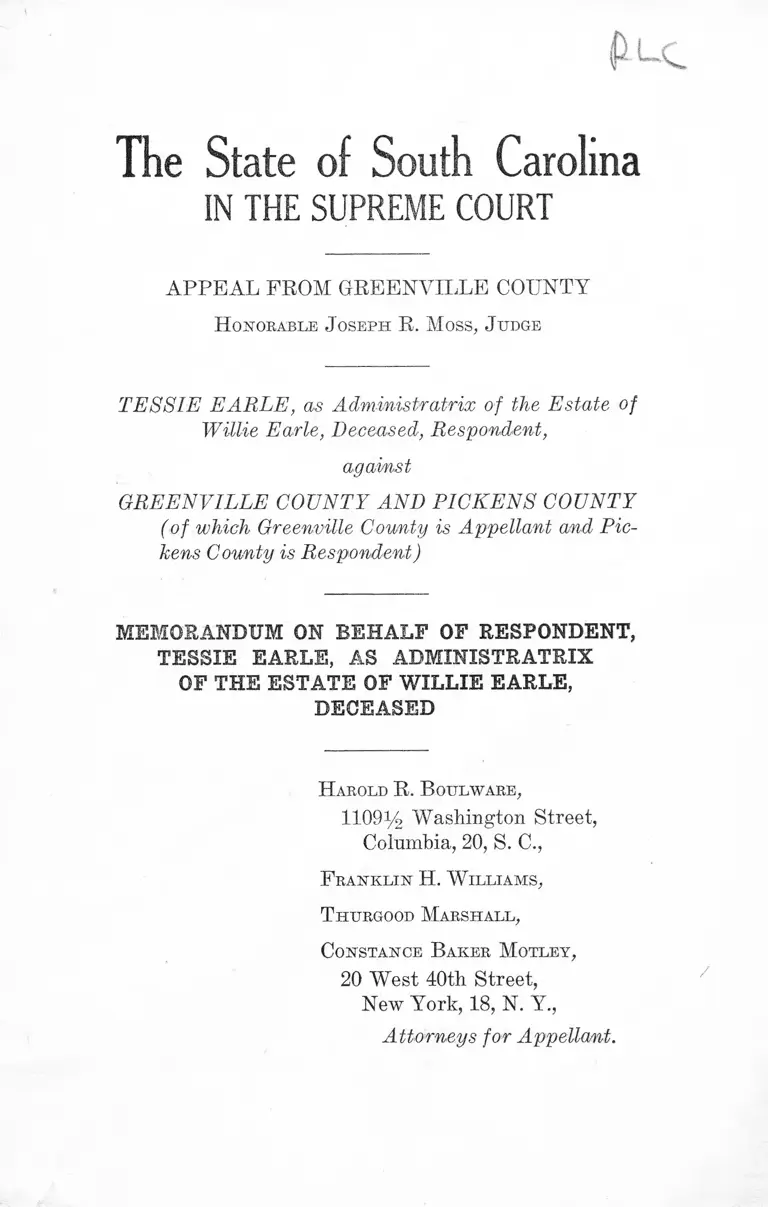

The State of South Carolina

IN THE SUPREME COURT

APPEAL FROM GREENVILLE COUNTY

H onorable J oseph R. Moss, J udge

TESSIE EARLE, as Administratrix of the Estate of

Willie Earle, Deceased, Respondent,

against

GREENVILLE COUNTY AND PICKENS COUNTY

(of which Greenville County is Appellant and Pic-

hens County is Respondent)

MEMORANDUM ON BEHALF OF RESPONDENT,

TESSIE EARLE, AS ADMINISTRATRIX

OF THE ESTATE OF WILLIE EARLE,

DECEASED

H arold R. B oulware,

1109% Washington Street,

Columbia, 20, S. C.,

F ranklin H. W illiams,

T hurgood Marshall,

Constance B aker M otley,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, 18, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Appellant.

INDEX

P age

Question Involved ........................................................ 1

Statement................................................... ................. . 2

Argument . . . . . . . . ...................................... . 3

1

QUESTION INVOLVED

This appeal raises only one question for determina

tion by this Court. That question is: Whether there

are sufficient facts alleged in the complaint filed in this

action to sustain a recovery, if proved, against Green

ville County for the “ lynching death” of Willie Earle

by his duly appointed administratrix, the respondent

herein.

8

(1)

2 SUPREME COURT

Earle v. Greenville County et al.

STATEMENT

Respondent, Tessie Earle, administratrix of the

estate of Willie Earle, deceased, brought this action in

the Court of Common Pleas for Greenville County on

January 28, 1949 alleging in her complaint that Green

ville County and Pickens County were liable to the

estate of Willie Earle for a statutory penalty and

prayed recovery of $5,000.00 against each County

under the provisions of Article 6, Section 6, of the Con

stitution of South Carolina of 1895 and Section 3041

of the Code of Laws of South Carolina for 1942 for the

death of Willie Earle, a result of his. being lynched in

said Counties.

The complaint alleged that Willie Earle, prior to his

death, was a resident and citizen of the County of Pic

kens, South Carolina; that the said Willie Earle, while

under arrest and in the custody of officers of Pickens

County in connection with the alleged stabbing of an

other citizen, was taken by a large number of citizens

who, acting in the belief that the said Willie Earle was

guilty of the crime with which he was charged, carried

him into Greenville County and there lynched him, and

there put him to death by beating, shooting, and stab

bing him.

The respondent, Tessie Earle, administratrix of the

estate of Willie Earle, deceased, has no interest in this

appeal from the decision of the Honorable Joseph R.

Moss sustaining the demurrer of Pickens County and

overruling the demurrer of Greenville County herein

except to see that one or the other of the Counties

against which her original complaint is directed is held

liable under Article 6, Section 6, of the South Carolina

Constitution of 1895 and Section 3041 of the Code of

Laws of South Carolina for 1942.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Greenville County

3

In the Greenville County Court of Common Pleas re

spondent argued that both Counties herein were liable

to the estate of Willie Earle by virtue of the provisions

of the State Constitution and the Laws of 1942, supra.

The Court of Common Pleas for Greenville County

held, however, in overruling the demurrer of Green

ville County and sustaining the demurrer of Pickens

County that the constitutional and statutory provi

sions applicable hereto were intended to provide for

the recovery of only one penalty; that the penalty was

to be recovered against the County where the “ lynch

ing death ’ ’ occurred; and that since the lynching death

occurred in Greenville County, said County is liable in

this action. Since the only interest respondent can have

in this appeal is in seeing that one or the other County

is held liable, respondent respectfully submits that the

Judge of the Court of Common Pleas for Greenville

County was correct in holding Greenville County liable

in this action, and, therefore, this memorandum on be

half of respondent is in support of the decision of the

Judge of the lower court.

ARGUMENT

Appellant County concludes in its brief (page 6)

that “ there can be no doubt that our Constitution and

statutes give a cause of action for any lynching where

death ensues.” Appellant then defines lynching as a

term which includes the following:

“ (1) That the person lynched be charged with or

suspected of a crime.

(2) That a mob or combination of persons as

semble.

4 SUPREME COURT

Earle v. Greenville County et al.

(3) That the person be seized by the mob or com

bination of persons either from the custody

of the law or otherwise.

(4) That summary and illegal punishment be in

flicted upon the person by the mob because of

the crime with which he is charged or of

which he is suspected.”

Yet in the same paragraph in which appellant states

its conclusion set out above, appellant concludes that:

u * # # the cause of action is not given

against the County where the ‘ death ensues’ to use

the words of the statute, but against the County

where the ‘ lynching takes place.’ ”

Appellant agrees that the death of Willie Earle did

not occur in Pickens County; that it occurred in Green

ville County at the hands of a lawless mob who had un

lawfully seized Willie Earle from lawful custody. Yet

appellant argues that Greenville County cannot be li

able because the statute only gives a cause of action

against a County where the “ lynching takes place,”

and points to Pickens County. If respondent had

brought her action against Pickens County under the

reasoning of appellant, respondent would have no

cause of action under the statutes and Constitution be

cause no death “ ensued” in that County as a result of

a lynching even though Willie Earle was “ lynched”

in Pickens County. But at the same time, appellant

argues that respondent has no cause of action against

it under the statute since no “ lynching” occurred in

Greenville County, only a death. In other words, ap

pellant’s argument is that respondent is not in a posi

tion to recover against either County. But even this

argument is refuted by appellant in its own brief when

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Greenville County

5

it points out that the purpose of the statute, which is

to prevent lynchings, is contra to this conclusion and

that where a lynching occurs and death results the

legislature clearly intended to give a cause of action

against the County responsible.

In refuting its own argument that respondent cannot

recover from either County, appellant appropriately

points out in its brief that in Kirkland v. Allendale

County, 128 S. C. 540, 123 S. E. 648, this Court said:

“ Another familiar general principle of inter

pretation of Constitutions is that a provision

should be construed in the light of the history of

the times in which it wTas framed and with due re

gard to the evil it was intended to remedy, so as to

give it effective operation and suppress the mis

chief at which it was aimed.” (Italics ours.)

Thus the argument of appellant, respondent respect

fully submits, is entirely fallacious for the reason that

it would result in the defeat of the purpose of the stat

ute and the intent of the legislature. Respondent re

spectfully suggests to this Court that the only question

on this appeal is whether sufficient facts are alleged,

to sustain a recovery if proved, to show that a lynch

ing death within the meaning of the Constitution and

statutory provision applicable to this ease occurred in

Greenville County.

I. Purpose of Statutory and Constitutional Pro

visions.

As pointed out above, appellant’s argument would

thwart the purpose of the statute and constitutional

provision by releasing both defendants in this action

and leave the respondent without remedy contrary to

the intention of the legislature and the framers of the

Earle v. Greenville County et al.

Constitution. As very suitably pointed out by appellant

in its brief, the framers of South Carolina’s Constitu

tion of 1895 realized that the prevention of lynchings

was a matter with which the State must concern itself

and, therefore, wrote the following provision:

“ Section 6. Prisoner lynched through negli

gence of officer—penalty on officer—county liable

for damages.—In the case of any prisoner lawfully

in the charge, custody or control of any officer,

State, County or municipal, being seized and taken

from said officer through his negligence, permis

sion or connivance, by a mob or other unlawful as

semblage of persons, and at their hands suffering

bodily violence or death, the said officer shall be

deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon true

bill found, shall be deposed from his office pend

ing his trial, and upon conviction shall forfeit his

office, and shall unless pardoned by the Governor,

be ineligible to hold any office of trust or profit

within this State. It shall be the duty of the prose

cuting Attorney within whose Circuit or County

the offence may be committed to forthwith insti

tute a prosecution against said officer, who shall be

tried in such county, in the same circuit, other than

the one in which the offence was committed, as

the Attorney General may elect. The fees and mile

age of all material witnesses, both for the State

and for the defence, shall be paid by the State

Treasurer, in such manner as may be provided by

law: Provided, m all cases of lynching when death

ensues, the County where such lynching takes

place shall, without regard to the conduct of the

officers, he liable in exemplary damages of not less

than two thousand dollars to the legal representa-

6_______________SUPREME COURT

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Greenville County

7

fives of the person lynched: Provided, further,

That any County against which a judgment has

been obtained for damages in any case of lynch

ing shall have the right to recover the amount of

said judgment from the parties engaged in

said lynching in any Court of competent jurisdic

tion.” (Emphasis appellant’s.)

The legislature, pursuant to this provision, enacted

Section 3041 of the Code of Laws for South Carolina,

1942, which provides that:

“ In all cases of lynching when death ensues the

county where such lynching takes place shall with- 86

out regard to the conduct of the officers, be liable

in exemplary damages of not less than two thou

sand dollars, to be recovered by action instituted

in any court of competent jurisdiction by the legal

representatives of the person lynched, and they are

hereby authorized to institute such action for the

recovery of such exemplary damages # * *”

It is clear from both of these provisions that the

framers of the Constitution and the legislature had in

mind the purpose of deterring those who would take ”

the law into their own hands and had the intention of

giving to the legal representative of any victim of a

“ lynching death” a clear cause of action against the

County which should have prevented such death. These

provisions were made effective in order to curtail the

very type of tragedy for which the plaintiff in the in

stant case seeks recovery.

“ That the salutary object of this constitutional

provision was to promote, through the means pre- gg

scribed, the observance of certain other provisions

of the constitutional charter, guaranteeing the citi-

8 SUPREME COURT

Earle v. Greenville County et al.

zen against deprivation of life, liberty or property

without due process of law, etc., is not open to

question. # * * In the historical aspect, the

nature of the evil against which this constitutional

provision was levelled requires no comment.”

Kirkland v. Allendale Co., 128 S. C. 541.

These provisions, in view of the above tragedy, which

they were designed to curtail, must be liberally con

strued, this Court said, so as to give relief in any case

coming substantially within the spirit of the law.

“ * * # This p r o v i s i o n , as apprehended,

should receive a liberal interpretation to the end

that the remedy prescribed to check the evil aimed

at should not be denied in any case which comes

substantially within the spirit of the law.” Kirk

land case, supra. See Brown v. Orangeburg County,

55 S. C. 45.

II. The “ Lynching Death” occurred m Greenville

County.

The statutory and constitutional provisions being

thus clearly intended to give a cause of action in a case

such as the instant one against the County responsible

for the death as a result of a lynching, it only remains

to be decided whether sufficient facts are alleged to

show in which County such “ lynching death” oc

curred. The lower court held, and the respondent

agrees, that the “ lynching death” in this case, accord

ing to the allegations of the complaint, occurred in

Greenville County. Greenville County argues that only

a death occurred within its borders and attempts

through very spurious reasoning to dissociate the death

from the “ lynching” and present respondent with an

imaginary, nefarious dichotomy resulting in the di

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Greenville County

9

lemma of no cause of action against either County for

the very poignant fact of death resulting from a

lynching.

While in Greenville County, even under the definition

of lynching set out in appellant’s brief, Willie Earle

was in fact “ lynched.” He was still “ seized” by the

same mob which had taken him from the lawful custody

of law enforcement officers of Pickens County. This

mob, while in Greenville County, still suspecting him or

believing him to be guilty of the crime with which he

was charged, administered, in Greenville County, sum

mary and illegal punishment by beating and shooting

him. At this point Willie Earle was “ lynched” in

Greenville County. In addition, his death “ ensued” in

Greenville County.

Therefore, even under the definition of appellant, a

“ lynching” occurred in Greenville County and such a

lynching as the statutory and constitutional provision

provides a recovery for; i. e., lynching resulting in

death.

III. Greenville County had the last clear chance to

prevent the evil which the statutory and constitutional

provisions are designed to curb.

As appellant so rightly points out in its brief, the

purpose of the constitutional provision and statute was

to “ impose a penalty for crime to the end that the com

mission of the crime might- be deterred.” Kirkland v.

Allendale Co., supra (pp. 11-12). Appellant in addition

cited an appropriate portion of this court’s decision in

Brown v. Orangeburg Co., supra, to the effect that the

purpose of the Constitution was to prevent the crime

of lynching in two ways: “ (1) By visiting upon the of

ficers of the law the penalties therein mentioned, when

10 SUPREME COURT

Earle v. Greenville County et al.

a prisoner lawfully in their custody was lynched by a

mob through their negligence, permission or conni

vance; and (2) to induce the cooperation of the tax

payers in preventing the lynching, in order that their

counties might not become liable to the penalty by way

of exemplary damages of not less than $2,000.00 to the

legal representative of the person lynched * # * ”

Appellant then states that it is hard to see why

punishing the County where the death happened to oc

cur by assessing exemplary damages against it would,

as was said in Brown v. Orangeburg Co., supra, “ ren

der protection to human life, and make communities

law abiding,” or how such punishment could “ induce

the cooperation of the taxpayers in preventing the

lynching.” (Appellant’s brief, p. 12.)

Respondent respectfully submits that it is not at all

difficult to see how punishing Greenville County in the

instant case would serve the purpose of the statute.

Greenville County, even assuming Pickens County is

liable for the “ lynching” because its officers were neg

ligent or connived with the mob, had the last clear

chance to prevent the crime which the statute was de

signed to curb. But for the negligence of the law en

forcement officers of Greenville County, and but for

the lack of vigilance and determination on the part of

the taxpayers of Greenville County, Willie Earle’s life

would have been spared even though he had been

lynched. It is a well-established principle of the com

mon law that liability for injury will lie, despite the

negligence of the plaintiff or a third party, where the

defendant in the case had the last clear chance to pre

vent the injury complained of and where, because of

the defendant’s own negligence, advantage was not

taken of this chance. See 38 Am. Jur. 900, Section 215,

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Greenville County

11

Thus, respondent respectfully submits in conclusion

that even though Pickens County may be liable equally

with Greenville County, Greenville County neverthe

less had the last clear chance to prevent the evil which

the statute and constitutional provision of this State

are designed to curb. The only County which, without

question, could have and failed to prevent the lynching

death of Willie Earle was Greenville County for the

reason that when Willie Earle met his death as a result

of a lynching, he was within the jurisdiction of Green

ville County and not within the jurisdiction of Pickens

County.

CONCLUSION

Respondent respectfully prays that this Court affirm

the decision of the Court of Common Pleas for Green

ville County.

Respectfully submitted,

H arold R. B oulware,

1109% Washington Street,

Columbia, 20, S. C.,

F ranklin H. W illiams,

T htjrgood Marshall,

Constance Baker Motley,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, 18, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Appellant.