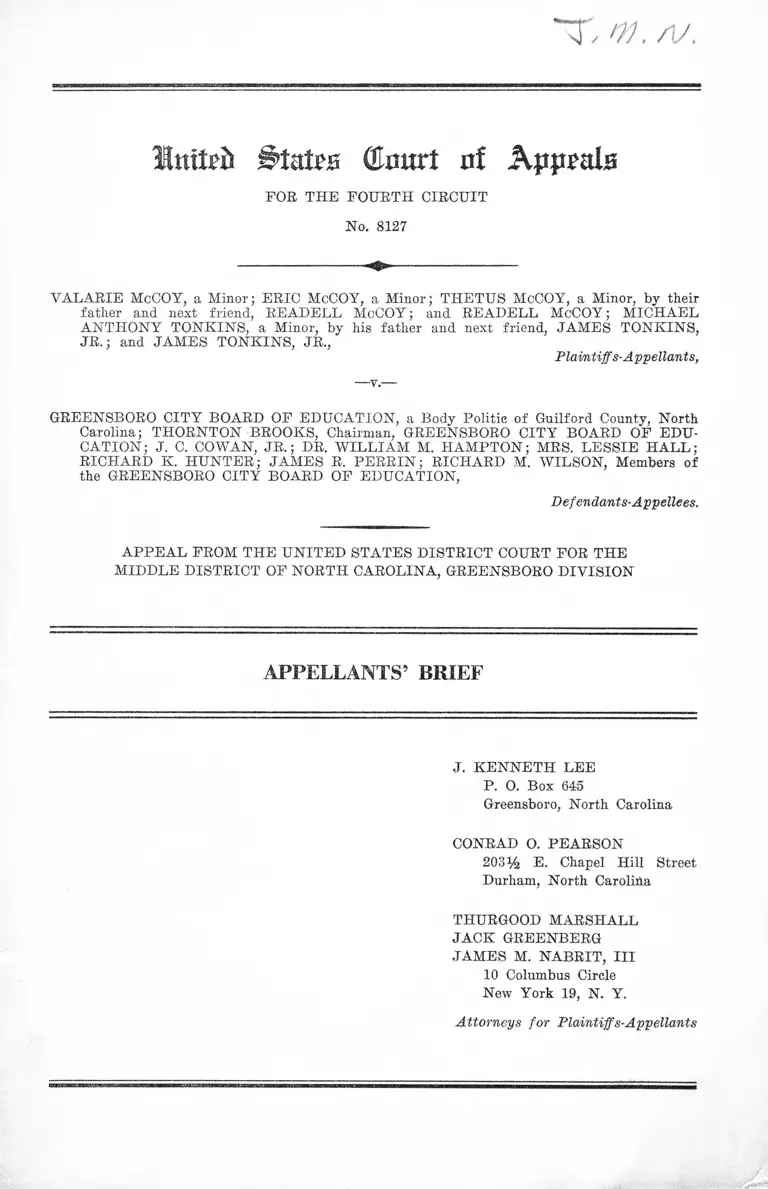

McCoy v. The Greensboro City Board of Education Appellants Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCoy v. The Greensboro City Board of Education Appellants Brief, 1960. d2c25f7e-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/44eb5604-7e48-4400-bce2-3f00cbf9aa4c/mccoy-v-the-greensboro-city-board-of-education-appellants-brief. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

T, m, /v.

Initrii States Court of Apprals

FOE THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 8127

VALARIE McCOY, a Minor; ERIC McCOY, a Minor; THETUS McCOY, a Minor, by their

father and next friend, READELL McCOY; and READELL McCOY; MICHAEL

ANTHONY TONKINS, a Minor, by his father and next friend, JAMES TONKINS,

JR .; and JAMES TONKINS, JR.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

GREENSBORO CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION, a Body Politic of Guilford County, North

Carolina; THORNTON BROOKS, Chairman, GREENSBORO CITY BOARD OF EDU

CATION; J. C. COWAN, JR.; DR. WILLIAM M. HAMPTON; MRS. LESSIE HALL;

RICHARD K. HUNTER; JAMES R. PERRIN; RICHARD M. WILSON, Members of

the GREENSBORO CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA, GREENSBORO DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J. KENNETH LEE

P. O. Box 645

Greensboro, North Carolina

CONRAD O. PEARSON

203% E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

THURGOOD MARSHALL

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, I II

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

INDEX TO BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................... 1

Question Presented ..................................................... 6

How the Question Arises ................................................ 6

Statement of the Pacts .................................................... 7

A r g u m e n t

The power of federal courts to enjoin school seg

regation policies in class actions includes power

to restrain all actions and policies of school au

thorities which affect the assignment and educa

tion of pupils on the basis of race and to require

the systematic elimination of racial discrimination

in a segregated school system................... - ............ 13

A. Plaintiffs Can Secure Relief Only by Elim

ination of the Segregation Policy Which Is

Directed at Negroes as a Class...................... 13

B. The So-Called Administrative Remedy of the

Pupil Assignment Law Does Not Preclude

Granting the Relief Requested ...................... 21

C. Continued Segregation by Defendants Vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment.................. 24

C onclusion

H

A u thorities C it e d :

Gases:

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, Va., 266 F. 2d 507 (4th Cir. 1959) — ..... 17

Avery v. Wichita Falls, 241 F. 2d 230 (5th Cir.

1957) ........................................................18,19,20,22,27

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ................................. 14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, reaff’d

349 IT. S. 294 ................................................ 14,15, 22, 23

Carson v. Board of Education, 227 F. 2d 789 (1955)

21, 23

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (1956) .............. 21, 26

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ............................. 14,16, 23

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (1959) .......... 21

Farley v. Turner, No. 8054, 4th Cir., June 28,

1960 .....................................................................21,22,23

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade

County, 246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957) ............... -..... 18

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, etc., 272 F. 2d

763 (5th Cir. 1959) .................................................... 18

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, etc., 258 F.

2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958) ......... , ................ -..............-18, 27

Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265 F. 2d

95 (4th Cir. 1959) ....................................................21, 22

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, Vir

ginia, 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) .................. 22, 24, 25

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, etc., 277

F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960) ............................. 18,19, 22, 23

PAGE

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156 .. 22

Railroad & Warehouse Comm’n of Minn. v. Duluth

St. Ry., 273 IT. S. 625 ............................................ 24

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen,

240 F. 2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956) ................................. 17

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S. 629 .... 27

Codes:

28 U. S. C. §§1331, 1343 ......................................... 2

42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1983 ......................................... 2

Rules:

Rule:

Rule 23(a)(3), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ..2, 22

United States Constitution:

Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1 ............_............ 2

Other Authorities:

Pomeroy’s Equity Jurisprudence (5th Ed. Sy

mons), Vol. 2, p. 185 ............................... ......... . 24

3 Pomeroy, §397, et seq........................................... 24

4 Race Rel. Law R. 31

Ill

PAGE

24

Hutted States Olniirt of Appeals

F oe th e F ourth C ircuit

No. 8127

V alarie M cCoy, a Minor; E ric M cCoy, a Minor; T hetu s

M cCoy, a Minor, by their father and next friend, R ea

dell M cCo y ; and R eadell M cCo y ;

M ich ael A n t h o n y T o n k in s , a M in or, b y his fa th er and

next fr ien d , J ames T o n k in s , J r.; and J am es T o n k in s ,

Jr.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

— v.—

G reensboro C it y B oard of E ducation , a Body Politic of

Guilford County, North Carolina; T hornton B rooks,

Chairman, G reensboro C it y B oard of E ducation ; J. C.

C ow an , Jr.; Dr. W illiam M. H a m p t o n ; M rs. L essie

H a l l ; R ichard K. H u n t e r ; J ames R. P e r r in ; R ichard

M . W ilso n , Members o f the G reensboro C it y B oard of

E ducation ,

Defendants-Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t f o r t h e

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA, GREENSBORO DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This civil action by four Negro school children (Valarie,

Eric, and Thetus McCoy and Michael Tonkins) and their

respective fathers (Readell McCoy and James Tonkins)

2

seeks to prohibit racial segregation in the Greensboro,

North Carolina public schools.1

The action was commenced February 10, 1959, in the

United States District Court for the Middle District of

North Carolina, Greensboro Division. Jurisdiction was

invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §§1331, 1343 and 42 U. S. C.

§1983 alleging deprivation of rights protected by Section

1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States and by 42 U. S. C. §1981.

The action was brought as a class suit pursuant to Rule

23(a)(3), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, alleging that

“ there are common questions of law and fact affecting the

rights of all other Negro children attending the public

schools of Greensboro, North Carolina, and their respec

tive parents,” and that a common relief was sought.

The gravamen of the complaint was that the defendant

Greensboro Board maintained a racially segregated school

system pursuant to a racial policy of assigning students

that violated the rights of Negro school children under

the Fourteenth Amendment. The complaint stated in de

tail the circumstances under which the McCoy and Ton

kins children attended school under the segregated system,

and recounted their parents’ unavailing efforts, prior to

and at the beginning of the 1958-59 school year, to obtain

from the Greensboro Board assignments for their children

on the same basis as that used for white pupils similarly

1 The North Carolina Advisory Committee on Education and

the North Carolina State Board of Education, and individual

members of those boards were also named as defendants. A mo

tion to dismiss the action against those boards was unopposed by

plaintiffs and they are not parties to this appeal. Pleadings and

orders relating to those parties are not printed in Appellants’

Appendix or described in this statement. The opinion below suf

ficiently states the course of proceedings in relation to those

parties (App. 98a, 101a).

3

situated. Briefly it was alleged that these four Negro

children had been excluded, because of race and as a part

of a general board policy of segregation, from a building

known as David Caldwell Elementary School, maintained

for white students exclusively; and that they had been

assigned to an inferior building located on the campus of

the Caldwell School, which at one time had been a part

of that school, and which, during the 1958-59 term was

maintained for Negro pupils exclusively and was known

as the Pearson Street Branch of the Washington School.

Washington School proper, also was an all Negro school,

located some dozen blocks away from the branch.

The School Board answered, making numerous admis

sions, denials, and defenses.

Thereafter, before hearing, plaintiffs on September 23,

1959 moved for leave to file a supplemental complaint to

set forth events which had occurred since the original

complaint. These were, briefly, that following the 1958-59

school term the board assigned the McCoy and Tonkins

children (with the exception of Thetus McCoy who had

advanced to Junior High School) to the Caldwell School

proper; that the board had then consolidated the two

buildings on the Caldwell campus into one school and con

verted Caldwell School into an all-Negro school by as

signing Negroes in a designated neighborhood to Caldwell,

and by reassigning all white students attending Caldwell

school and living in that neighborhood to other schools.

The all-white Caldwell faculty was transferred to other

schools and an all-Negro faculty was substituted. The

proposed supplemental complaint alleged that these trans

fers, assignments, and reassignments were made on the

basis of race as part of a general pattern of actions through

out the system of assigning, reassigning, and transferring

pupils and teachers on a racial basis to maintain and per-

4

petuate racial segregation in the city school system, except

for admission of a small or “ token” number of Negro pupils

to “white” schools (App.34a-37a).

The proposed supplemental complaint prayed for an in

junction restraining the Board “ from engaging in any ac

tion that regulates or affects on the basis of race or color,

the admission, enrollment or education of the infant plain

tiffs, or any other Negro children similarly situated, in the

[Greensboro] public schools” . It further asked that the

Court require the school board “ to present to the court

for its approval, on or before a specified date, a com

plete plan for bringing about compliance with the order

of Court and providing a systematic and effective method

for eliminating racial discrimination within the city school

system with the least practicable delay.”

October 16, 1959, the-board filed motion for summary

judgment (App. 38a), supported by two affidavits (App.

40a, 42a), contending that the action should be dismissed

as moot on the ground that subsequent to complaint and

answer the McCoy and Tonkins children had obtained the

only relief to which they were entitled, i.e., assignment to

Caldwell School.

Opposing affidavits were filed by Messrs. Tonkins and

McCoy (App. 43a, 45a). A second affidavit of Mr. P. J.

Weaver, Greensboro School Superintendent, was filed on

October 27,1959 (App. 47a). On that date, the Court heard

argument of counsel on the pending motions, and then

requested further affidavits. Thereafter a third affidavit

by Superintendent Weaver (App. 58a) and opposing af

fidavits by Mr. Tonkins and Mr. McCoy were submitted

(App. 76a, 81a). At this time also plaintiffs submitted a

written motion for continuance pending the taking of dep

ositions (App. 86a), requesting an opportunity to take

the deposition of Superintendent Weaver, members of the

5

School Board, and other school personnel. Thereafter a

fourth “Reply” affidavit by Mr. Weaver was submitted

(App. 90a).

January 14, 1960, the Court issued an opinion, 170 F.

Supp. 745 (App. 94a), holding that there was no substantial

dispute over essential facts, and stated in detail various

transactions which had occurred involving the McCoy and

Tonkins children from their initial 1958 application until

the fall of 1959, when the cause was argued. The opinion

held that the proposed supplemental complaint afforded

no basis for relief, and the motion to file it was denied.

The Court decided that no relief could be granted under

either the original or supplemental complaints and that

the board’s motion for summary judgment should be

granted because the only legal question which the court

could adjudicate—i.e., whether the children had a right to

attend Caldwell School—was now moot:

“ For the reasons previously pointed out, the only re

lief which the court could possibly grant would be an

injunction requiring the Board to admit the eligible

minor plaintiffs to the Caldwell School upon a finding

that they had exhausted their administrative remedies

under the North Carolina Enrollment and Assignment

of Pupils Act, and that they were denied admission

on account of their race or color.”

The court then said that it was not clear, but in any

event was unnecessary to determine whether the plaintiffs

adequately exhausted their administrative remedies.

The opinion held that the Negro children could not main

tain a class action challenging the segregation policy of

the system, but only could seek admission to particular

schools, and if refused on racial grounds obtain a court

6

order requiring admission to the particular school in

volved. Plaintiffs’ request for time to take depositions

was denied on the ground that proof of the allegations of

the supplemental complaint would still not enable the court

to grant the relief sought.

March 23, 1960, judgment in accordance with the opinion

dismissed the action; costs were taxed against plaintiffs;

this appeal followed.

Question Presented

Whether, in a class action to enjoin under the Four

teenth Amendment the segregation policies of the Greens

boro Board of Education, the cause became moot and the

United States courts were powerless to require systematic

elimination of racial discrimination in the administration

of the school system, because defendants, after this suit

commenced, assigned plaintiffs to Caldwell School, where

they originally applied, and then converted it from a

“white” to a “ Negro” school, pursuant to a policy of main

taining an essentially segregated system and manipulating

assignment policies and school populations to that end.

How the Question Arises

This question arises in the record from the trial court’s

disposition of plaintiffs’ motions for leave to file proposed

supplemental complaint and for continuance pending dis

covery, and from disposition of the school board’s motion

for summary judgment and dismissal on the ground that

the only question which the Court was empowered to decide

was moot. The question was discussed and decided by

the Court below in its opinion dated January 14, 1960.

7

Statement of the Facts

No oral testimony was taken below; the only facts appear

from the admissions in the answer to the Complaint, the

affidavits and attached exhibits in support of and in oppo

sition to the Motion for Summary Judgment and, for

purposes of this suit, the averments of the proposed

Supplemental Complaint, which the Court below treated

as true, and concerning which depositions were not allowed

to be taken, on the ground that even if these depositions

established the correctness of the Supplemental Com

plaint’s averments, plaintiffs could not prevail.

The complaint alleges (ifVII, App. 5a) and the answer

admits (flVII, App. 16a) that on June 12, 1958, Michael

Anthony Tonkins, who had just become eligible for first

grade, and his father applied for admission to Caldwell

School. He first submitted an application to defendant

Board, on reassignment forms, no other forms being avail

able. The Board took no action. Then, by letter, the father

requested of the Superintendent information concerning

the Board’s policy for assigning first graders. No reply

was made, because, the answer avers, this was not “ the

proper procedure.” The answer admits also (ffVIII, App.

16a) that on September 2, 1958, the date set by the Greens

boro Board for first grade registration, Tonkins and his

child went to Caldwell, about three and a half blocks from

his home. The principal refused to enroll young Michael

Anthony, and referred them to the Washington Street

School, an all Negro school, about thirteen blocks from

plaintiff’s home. White neighbors of Tonkins (Answer

fflX, App. 17a) who lived approximately the same distance

from Caldwell as plaintiff were regularly enrolled in its

first and all other grades. Upon going to the Washington

Street School (Answer J[X, App. 17a) the child was en-

8

rolled by its principal to attend classes at its all Negro

Pearson Street Branch (App. 96a). This branch was an

integral part of the Caldwell campus and consisted of a

smaller building which contained no auditorium, cafeteria,

or gymnasium, and to which meals were transported from

the Washington Street School (Answer flXI, App. 18a).

The complaint alleges (UffXII-XIII, App. 8a) and the

answer admits (flflXII, XIII, App. 19a) that after Tonkins

was enrolled in the Pearson Street Branch of the Wash

ington Street School, application was made on or about

September 4, 1958, and in apt time for reassignment to the

David Caldwell School; and that on September 17, 1958,

Tonkins’ application for reassignment was considered and

denied. In apt time plaintiff appealed this decision, which

was considered and denied on October 21, 1958, without

any reason given.

Plaintiff Readell McCoy, father of Valarie (9), Eric (8)

and Thetus (11), was notified on June 7, 1958 that his

children were assigned for the 1958-59 school year to the

Pearson Street Branch of the Washington School. There

after, on June 11, 1958, and in apt time, McCoy applied

to the Board for reassignment of his children to the Cald

well School. On August 11, 1958, the Board denied these

applications. On August 18, 1958, McCoy appealed and on

September 16, the Board reaffirmed (Answer IfXIV, App.

19a-20a).

McCoy lives within three and a half blocks of the Cald

well School, as close as or closer than many of his white

neighbors.

In the complaint it was alleged and denied that the plain

tiffs were refused admission at Caldwell School because of

their race or color (Complaint: flVIII; Answer: 3rd de

fense IfVIII); alleged and denied that Caldwell School was

maintained for white students only (Complaint: flIX;

9

Answer: 3rd defense ffIX ); alleged and denied that the

Pearson Street Branch of the Washington School was

maintained as an inferior segregated part of the Caldwell

School campus (Complaint: IfX; Answer: 3rd defense

IfX); and alleged and denied that Negro children attend

ing the inferior building adjacent to the Caldwell School

were denied use of the superior facilities at Caldwell and

separated from the white pupils at Caldwell.

The Complaint contained the following allegation:

“While defendant Greensboro Board purports to

maintain a system of permitting transfers among

schools without regard to race, the system which it

maintains in fact implements a policy of racial dis

crimination. This system of segregation is maintained

by requiring as a matter of practice and policy that

Negro children entering school for the first time reg

ister in schools nearest their residences for Negroes

only. Negroes who attend schools for Negroes only

must continue attending such schools. White children

who enter school for the first time are as a matter

of practice registered in schools nearest their homes

for whites only. When a Negro child who lives

at or near a ‘white’ school applies for admittance

or initial assignment to the ‘wfhite’ school, he is sum

marily denied such admission and referred by the

principal of the said school to a ‘Negro’ school no

matter what the distance or circumstance. Thereafter,

if a Negro child desires to be transferred to the ‘white’

school located in the district of his residence he must

proceed under the requirements of the North Carolina

Pupil Assignment Act. This procedure is not required

of any white child under the jurisdiction of the defen

dant Greensboro Board who desires to enroll in or

transfer to a white school” (Complaint jfXVI, App. 9a).

10

The Answer responded to the above allegation stating:

“ The allegations as set out in Paragraph XVI of

the complaint are denied. In connection with the alle

gations contained in Paragraph XVI, these answering

defendants aver that if any child enrolled in the public

schools of Greensboro, whether Negro or white, wishes

to he transferred to another school in the Greensboro

School System, in order to obtain such transfer, appli

cation for reassignment must be made in accordance

with the requirements of the North Carolina Pupil

Enrollment Act and the rules and regulations issued

thereunder by the defendant Greensboro Board” (An

swer: 3rd defense flXVT, App. 21a).

The Greensboro Board affirmatively asserted by Answer

that they were not maintaining a segregated school system

in that several Negro pupils had been admitted as pupils

in “ white” schools in accordance with the North Carolina

Pupil Enrollment Act and under the local board’s own

rules and regulations for pupil reassignment. The Board

also asserted that it had defended its past reassignments

of certain Negro pupils to “white” schools when that action

was challenged in North Carolina courts, and in the face

of public hostility, and that the Board had taken its action

“ notwithstanding the fact that no Negro pupils have been

admitted to any other white schools anywhere in North

Carolina, with the exception of Charlotte and Winston-

Salem, and that in a number of States of the South not

a single Negro pupil has been admitted to any white public

school below college level” (Answer: Fourth Defense,

ftXIX, App. 22a).

Following filing of this suit, the proposed Supplemental

Complaint alleges Caldwell School was converted from a

“ white” school to a “Negro” school by the Greensboro

11

Board as a part of a general pattern of actions “in assign

ing, reassigning, and transferring pupils and teachers on

the basis of race in order to maintain and perpetuate

racial segregation” (App. 36a). As part of this program

plaintiffs were admitted to the Caldwell School proper,

numerous other Negro children were assigned there, a

Negro principal and Negro teachers were assigned there,

and white students, white principal and white teachers were

transferred out (App. 34a). In connection with the con

version of Caldwell to a “Negro” school the attention of

the Court is directed to a provision of the Rules and Regu

lations of the Greensboro Board which provides:

“ Eighth, (a) In the event that any child is assigned

to a school previously attended solely by children of

another race, this Board will on its own initiative, and

within the limits of available school facilities, permit

children previously assigned to such school to be as

signed to another school if their parents so desire”

(Exhibit A to Answer, App. 32a).

The plaintiffs’ Motion for Continuance pending discovery

(App. 86a) indicated various matters concerning the con

version of Caldwell School about which they sought to

take depositions and to inspect documents. In particular,

plaintiffs sought to examine the Superintendent, the

principal and former principals of the Caldwell School

concerning, inter alia, whether attendance areas were gerry

mandered, the procedure by which all white students were

transferred from Caldwell and whereby it became an “all-

Negro” school, the role that school personnel played in

effecting white students’ transfers, and so forth. Said

motion also sought to enable discovery of additional facts

related to a mimeographed school assignment notice (App.

80a) whereby apparently only Negroes were assigned to

Caldwell (App. 78a).

12

One further factual situation which emerges from an

exchange of affidavits should be mentioned as it relates to

plaintiffs’ theory of the relief to which they are entitled.

The affidavit of Readell McCoy, November 10, 1959, avers

that Ms son, Thetus, was assigned in June 1959 to the

all-Negro Lincoln Junior High School together with all

other Negro pupils completing the sixth grade at the

“ Negro” school building adjacent to Caldwell School

(called the Pearson Street Branch of the Washington

School), while at the same time all white students com

pleting the sixth grade at Caldwell were assigned to other

Junior High Schools, and that no white students were ever

assigned to the Lincoln School or any other school main

tained exclusively for Negroes (App. 78a-79a). The reply

affidavit of Superintendent P. J. Weaver asserts that the

assignments were made in accordance with a policy “which

had previously been fixed by the Board, and were made

the same as was done in the previous year.” “ Therefore” ,

the affidavit continued, “ the assignment of Thetus McCoy

to the Lincoln Junior High School was in accordance with

assignment to the customary school for pupils promoted

from the sixth grade of the Washington Street School”

(App. 92a-93a) (emphasis added). Concerning this the

Court simply found that Thetus was assigned to and was

attending Lincoln School and that no reassignment appli

cation had been filed on his behalf (App. 99a), which

concluded the matter, consistent with the view below that

the court could “ only grant an injunction requiring the

Board to admit the eligible minor plaintiffs to the Caldwell

School” , given appropriate proof.

13

ARGUMENT

The power of federal courts to enjoin school segrega

tion policies in class actions includes power to restrain

all actions anti policies of school authorities which affect

the assignment and education of pupils on the basis of

race and to require the systematic elimination of racial

discrimination in a segregated school system.

A.

Plaintiffs Can Secure Relief Only by Elimination

of the Segregation Policy Which Is Directed at

Negroes as a Class

The Court below held that the only constitutional right

of Negro pupils in a school segregation ease was the right

not to be excluded from a. given school because of race;

and that Negro pupils in a system where the board manipu

lated assignment of pupils and teachers on the basis of

race to perpetuate segregation (except for admitting a

small number of Negroes to “white” schools as token of

“compliance” with the Fourteenth Amendment) could ob

tain no relief in a federal court to remedy this situation.

This ruling was based upon a state statute and local regula

tions providing procedure for individuals to request change

of school assignment after having been initially assigned

to a segregated school. The Court further held that as

Negro pupils could only assert personal constitutional

rights they had no right to challenge a general policy of

racial pupil assignment where they had been first racially

excluded from, and later admitted to, the school of their

choice, even though the subsequent assignment was accom

panied by further racially inspired pupil assignments de

signed to perpetuate segregation. Plaintiffs wrongfully at

tempted, it was held, to assert rights of a class rather than

14

personal rights; the case was held mooted by plaintiffs’ ad

mission to the school where they applied, notwithstanding

the Board’s continued racial assignment policy.

These conclusions, it is submitted, are erroneous. The

right asserted by these Negro children and parents under

the due process and equal protection clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment is the right to freedom from imposition

of arbitrary restraints on their liberty because of race and

the right to receive public education in institutions main

tained by the state without racial discrimination. The Su

preme Court held in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483 (and reaffirmed in the second Brown opinion, 349 U. S.

294 and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1) that the separation

of students in public schools by race constituted an invidi

ous discrimination which denied equal protection of the

laws. The “ separate but equal” doctrine was repudiated;

racially segregated schools were stamped “ inherently un

equal” . Indeed, racial segregation in public education was

held to be such an unjustifiable discrimination, infringing

the liberties of citizens on the basis of race without ref

erence to any proper governmental objectives, that it vio

lated due process of law. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497;

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1,19.

The Supreme Court held in Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U. S. 294 that the courts must exercise the traditional

attributes of equity in fashioning appropriate remedies to

effect complete relief in school segregation cases. The cases

which culminated in the Brown decisions were brought as

class actions, discrimination against a class was alleged,

and the Supreme Court expressly treated the cases as class

actions calling for remedial action involving the whole class

of persons discriminated against. After holding in Brown

I that state enforced racial segregation in public schools is

unconstitutional, the Court ordered reargument as to type

15

of relief, in view of the fact that these were class actions.

The Court said:

Because these are class actions, because of the wide

applicability of this decision, and because of the great

variety of local conditions, the formulation of decrees

in these cases presents problems of considerable com

plexity (347 U. S. at 495).

Clearly then the Supreme Court considered the cases as

necessarily involving relief to Negroes as a class in the

districts involved rather than merely the admission of in

dividual plaintiffs to particular schools. Pursuant to the

latter approach the Court simply could have ordered the

named plaintiffs admitted to the particular “white” schools

for which they were eligible without further considering

relief.

In Brown II, the type of relief given and the type of

factors considered involved remedy for the class as a whole

—relief affecting the entire system, not simply schools

plaintiffs might be eligible to attend. The Court wrote:

At stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs in

admission to public schools as soon as practicable on

a nondiscriminatory basis. To effectuate this interest

may call for elimination of a variety of obstacles in

making the transition to school systems operated in

accordance with the constitutional principles set forth

in our May 17, 1954, decision” (at 300). (Emphasis

added.)

=£ # * * *

To that end, the courts may consider problems re

lated to administration, arising from the physical con

dition of the school plant, the school transportation

system, personal, revision of school districts and at

tendance areas into compact units to achieve a system

16

of determining admission to1 the public schools on a

nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and regula

tions which may be necessary in solving the foregoing

problems. They will also consider the adequacy of any

plans the defendants may propose to meet these prob

lems and to effectuate a transition to a racially non-

discriminatory school system. During this period of

transition, the courts will retain jurisdiction of these

cases (300-301). (Emphasis added.)

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7, restated and reaffirmed

Brown:

It was made plain that delay in any guise in order

to deny the constitutional rights of Negro children

could not be countenanced, and that only a prompt

start, diligently and earnestly pursued, to eliminate

racial segregation from the public schools could consti

tute good faith compliance. State authorities were thus

duty bound to devote every effort toward initiating

desegregation and bringing about the elimination of

racial discrimination in the public school system. (Em

phasis added.)

Certainly, Negro plaintiffs in school segregation cases

assert, and indeed possess, personal constitutional rights

only as individuals and not as a group or class. But, under

Brown, and the Federal Buies, individual children and

parents may maintain a class action to challenge a segre

gation policy or statute as unlawfully depriving them, and

others similarly situated, of constitutional rights, and they

may secure injunctive relief prohibiting a pattern of ra

cially discriminatory practices used to maintain a segre

gated school system. The right asserted is the individual’s

right to freedom from discriminatory treatment by state

governments. But, as the discriminatory policy is based

17

on race, it is directed at individuals comprising a group or

class defined by reference to race and because of their mem

bership in that class. The individual’s right, as well as

his plight, under racial segregation is, by virtue of the

nature of the discrimination, intimately associated with the

discrimination imposed upon the class of which he is a

member. Racial segregation unconstitutionally brands all

Negro pupils as inferiors to be set apart from white pupils

in the enjoyment of public education.

As the history of this case shows, in point of fact, these

plaintiffs cannot escape segregation unless defendant Board

stops applying racial standards to all children in Greens

boro. Pupil placement secured for plaintiffs admission

to the school to which they first sought admission. The

Board’s segregation policy converted the reassignment into

further racial segregation.

In several cases this Court has affirmed injunctive orders

requiring the end of a school board policy of assigning

students by race. In School Board of City of Charlottes

ville, Fa. v. Allen, 240 F. 2d 59, 61 (4th Cir. 1956), the

Court affirmed such an order.2 This Court in Allen v.

County School Board of Prince Edward County, Fa., 266

F. 2d 507, 511 (4th Cir. 1959), directed the district court

to enter an order enjoining the defendants in virtually the

same language used in the Charlottesville order. This lan

guage was the pattern for that used in the prayer of the

supplemental complaint in this case.

Several Cases decided by the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit also support plaintiffs’ position in this ease,

2 The order restrained the defendants:

“From any and all action that regulates or affects on the basis

of race or color, the admission, enrollment or education of

the infant plaintiffs, or any other Negro child similarly situ

ated, to and in any public school operated by the defendants.”

18

including Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, etc., 258

F. 2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958); Gibson v. Board of Public In

struction of Dade County, 246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957);

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, etc., 272 F. 2d 763

(5th Cir. 1959); Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction,

etc., 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960); and Avery v. Wichita

Falls, 241 F. 2d 230 (5th Cir. 1957).

In Holland, supra, the Court found a Negro child in

eligible to attend a white school on the basis of his resi

dence, but held that because a segregated system was main

tained, the trial court should retain jurisdiction to enter

appropriate orders bringing the discriminatory system to

an end. In the first Gibson opinion, supra, the plaintiffs

were held entitled to relief against maintenance of a segre

gated system even though they had not sought admission

to particular schools. In the second Gibson opinion, supra,

it was held that a pupil assignment statute was not in

itself a “plan for desegregation” within the meaning of

Brown, and the district court was directed to require the

board to bring forth and implement a plan to eliminate

discrimination.

In the Mannings decision, where a complaint had been

dismissed because Negro pupils made no application to

particular schools under a pupil assignment statute, the

Court wrote:

“ Proof might have been introduced under the allega

tions of the complaint showing that the pattern of

segregation was still maintained by the Board’s auto

matically assigning all pupils to the same racially

segregated schools which they had been attending,

without applying any standards or tests to any but

the relatively few Negro students who sought trans

fers to what had theretofore been white schools. Such

a course of conduct the Court might hold failed to

19

measure up to the requirements of the Florida state

law itself which asserted that ‘uniform tests’ were a

step ‘to the end that there will be established in each

school within the county an environment of equality

among pupils of like qualifications and academic at

tainments.’ It seems too plain to require comment

that no such aim would be achieved, or even approached,

unless whatever tests were ultimately adopted by the

Board were applied to all students and not only to

those wishing transfers” (277 F. 2d at 374).

The Court held in Mannings that if a system of segre

gation was shown to exist the plaintiffs were entitled to

have any individual applications for pupil assignment con

sidered “against the background of a decree of the trial

court prohibiting the consideration of the race of the pupil

as a relevant factor”. The opinion concluded, at page 375:

We conclude that, without being required to make

application for assignment to a particular school, the

individual appellants, both for themselves and for the

class which they represent, are entitled to have the

trial court hear their evidence and pass on their con

tention that the pupil assignment plan has not brought

an end to the previously existing policy of racial segre

gation. In the event proof of this fact is made then

appellants would be entitled to their injunction as

prayed.

Avery v. Wichita Falls, supra, involved facts in part sim

ilar to those here, in that Negro pupils were admitted to

a previously all-white school and then all of the white

students were transferred to other schools.3

3 As stated by the Court at 241 F. 2d 230, 232:

“ The plaintiffs lived in the area served by the Barwise

School. At the opening of the school term in September, 1955,

20

The Court held in Avery at 241 F. 2d 230, 232-34:

Clearly plaintiffs seeking judicial relief from racial

discrimination applied against the members of a nu

merous class may maintain a class action.

At the time the district court dismissed the com

plaint, a part of the plaintiffs’ X->rayer had been met,

that is they were attending the public school nearest

their homes, but it is by no means certain that they

had the same free privilege of transfer to or attendance

on any school of their choice as was accorded the white

children. Admittedly desegregation of the schools of

the district had not then been completed, though the

defendants professed such a purpose, and the court

thought it would be accomplished ‘within a matter of

months’.

* =£ * # *

We are of the clear opinion that, at the time of the

rendition of judgment by the district court the case

had not become moot and that it was error to dismiss

the action.

The Court reversed and remanded; the trial court was

directed to retain jurisdiction to require “good faith com

pliance.”

they applied for admission to that school and it is admitted

that they were refused on racial grounds. The Barwise School

was then being attended by white children only, but a new

school was under construction in Sunnyside Heights, a white

section of the town, to which it was planned to transfer the

white pupils. The new school had been scheduled for com

pletion by September, 1955 but was not actually completed

until January, 1956, after the present suit had been filed. The

white pupils were then transferred from Barwise to the new

school; Barwise was renamed the A. B. Holland School after

a former negro principal of the Booker T. Washington School,

and was opened on a nominally desegrated basis though only

negro pupils, including the minor plaintiffs, registered.”

21

A recent opinion by this Court indicates agreement with

Mannings, see Farley v. Turner (No. 8054, 4th Cir., June

28, 1960).

B.

The So-Called Administrative Remedy of the

Pupil Assignment Law Does Not Preclude

Granting the Relief Requested

The Greensboro Board and the Court below have cited

in support of their position several decisions by this Court,4

which apply the rule insisting upon exhaustion of admin

istrative remedies. But this ease does not directly in

volve the rule requiring the exhaustion of adequate and

expeditious remedies. While the Court below held that

it was unnecessary to determine whether the children had

properly pursued prescribed administrative procedures,

plaintiffs submit that the uncontroverted facts plainly show

that they used all available remedies prior to filing suit.

The answer does not assert as a defense that the plaintiffs

failed to exhaust administrative remedies—which, as al

leged, certainly followed the form of the statute and were

admittedly timely filed (Answer Paragraphs XII, XIII,

XIV, App. 19a)—it merely denies that they were refused

admission on racial grounds, without explaining why all

white students were assigned to Caldwell and all Negroes

were assigned to the adjacent building during the 1958-59

school term. The answer also fails to explain why the mod

ern, well-equipped Caldwell building served only white

students and the adjacent,; connected, ill-equipped annex

building served only Negro students in a neighborhood

where both races lived. In view of the fact that no issue

4 Carson v. Board of Education, 227 F. 2d 789 (1955); Carson

v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (1956); Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d

780 (1959); Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265 F 2d

95 (1959).

22

was, or could have been made, over exhaustion, the Court

below should have “ reached the merits of the case,” Holt

v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265 F. 2d 95, 98 (4th

Cir. 1959), cert, denied, 361 U. S. 818, which turn on the

fundamental segregation policy of the Board.

But basically there is no prescribed administrative

remedy, “ reasonably expeditious and adequate”, Farley

v. Turner, supra, or otherwise, by which plaintiffs may

challenge the general use of racial assignment standards

in the system. Under the board’s procedures they are only

permitted to request a change of assignment for a par

ticular child; the grant of such relief is the only possible

remedy. There is no administrative remedy at all by which

plaintiffs may object to the general policy of making all

initial assignments on a racial basis. There is no admin

istrative remedy whereby plaintiffs can stop the board

from assigning out all white children and teachers and

from assigning in only Negro children and teachers at the

Caldwell School.

No case cited by the Board supports the decision below,

for those cases, particularly when read in the light of the

Jones, Mannings, and Farley decisions, supra, do not re

flect a theory that federal courts are powerless to deal with

discriminatory school systems except on a child-by-child

basis or that the courts are impotent to enjoin the general

use of discriminatory practices. Nor do those cases di

minish the right, created by Federal Rule 23(a)(3), to

maintain representative actions in appropriate cases when

a group is suffering a common wrong at the hands of a

state agency.5

5 Cases upholding the right of Negro students to maintain class

actions in school segregation cases are: Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, supra.; Avery v. Wichita Falls, 241 F. 2d 230, 232, n. 2,

and cases cited therein; Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242

F. 2d 156, 165 and eases cited therein; and see discussion of the

substantive considerations, supra, pp. 13-21.

23

In Carson v. Board of Education, 227 F. 2d 789, 791,

the Court clearly indicated that the basis of the exhaustion

rule was the reluctance of federal courts to interfere

“where the asserted federal right may be preserved with

out it.” Farley v. Turner, supra, demonstrates continued

recognition of the reason for the rule. But here it is

plain that the McCoy and Tonkins children and other

Negro children in the school district require a general

order prohibiting the use of racial assignment standards,

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, supra, and that

their “asserted federal rights” cannot “be preserved with

out it.”

Here, plaintiffs submitted themselves to the administra

tive machinery of the Greensboro Board and applied to

particular schools. By virtue of this submission to the

administrative process, it is now contended that they are

to be deprived of the right 'to challenge the maintenance

of a discriminatory assignment system based on race, de

signed and operating to perpetuate segregation throughout

the school system.6 Plaintiffs should not be deprived of the

right to secure relief from such a system—a discriminatory

system which affects them personally and directly just as

much as it affects other Negro children in the district—

merely because as a part of the racial scheme the Greens

boro Board, after first rejecting plaintiffs on racial

grounds converted the school plaintiffs applied to attend

from a “ white” to a “ Negro” school and admitted plaintiffs

to the building while the lawsuit was pending. It is re

spectfully submitted that such a resolution of plaintiffs’

6 No subjective “ good faith” , public pronouncements of obedi

ence to the Fourteenth Amendment, or token admission of selected

Negro students to “white” schools is a suitable substitute for a

“diligently and earnestly pursued” policy of eliminating segre

gation. Brown v. Board of Education, supra; Cooper v. Aaron,

supra.

24

quest for relief would be plainly anomalous and would fly

in the face of the basic maxim that “ Equity will not suffer

a wrong without a remedy”, Pomeroy’s Equity Jurispru

dence (5th Ed. Symons), Yol. 2, p. 185. Certainly it would

be anomalous if the application of the equity rule pertain

ing to exhaustion of remedies were allowed to create such

an inequitable result. Indeed, since abstention which defers

federal jurisdiction in the face of state administrative

remedies is an equitable doctrine, cf. Railroad & Ware

house Comm’n. of Minn. v. Duluth St. Ry., 273 U. S. 625,

628, it would seem that defendants’ continued activity in

behalf of segregation invokes the fundamental equity doc

trine of “clean hands” , see 3 Pomeroy, §397, et seq., and

precludes them from seeking the aid of equity to support

their continued imposition of inequity.

C.

Continued Segregation by Defendants Violates

the Fourteenth Amendment

The assignment policies of the Greensboro Board plainly

violate the equal protection and due process clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment. In a recent case in this Court

which involved applications of individual pupils to par

ticular schools, Jones v. School Board of City of Alex

andria, Virginia, 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) (a general

order enjoining discrimination had been previously entered

by the trial court and was not appealed, 4 Race Rel.

Law R. 31) this Court made clear its views as to certain

general assignment practices which would necessarily affect

the rights of individual students. The Court wrote:

“ Obviously the maintenance of a dual system of

attendance areas based on race offends the consti

tutional rights of the plaintiffs and others similarly

situated and cannot be tolerated. . . . In order that

25

there may be no doubt about the matter, the enforced

maintenance of such a dual system is here specifically

condemned” (278 F. 2d at 76).

The Court also wrote at 278 F. 2d, page 77 that:

“ If the criteria should be applied only to Negroes

seeking transfer or enrollment in particular schools

and not to white children, then the use of the criteria

could not be sustained. Or, if the criteria are, in the

future, applied only to applications for transfer and

not to applications for initial enrollment by children

not previously attending the city’s school system, then

such action would also be subject to attack on consti

tutional grounds, for by reason of the existing segre

gation pattern it will be Negro children, primarily,

who seek transfers.”

Thus this Court has specifically condemned school as

signment arrangements such as were alleged in the com

plaint and denied by answer in this case, but with respect

to which the Court below decided it had no power to grant

relief. It is to be noted that the complaint in the instant

case specifically alleged a discriminatory administration

of the assignment and reassignment procedures to per

petuate segregation (App. 9a-10a). Also the segregation

policies, alleged in the proposed supplemental complaint—

and admitted for purposes of the decision below—to have

been continued by other methods after the complaint was

filed, appear from the affidavits and exhibits of the plain

tiffs (App. 76a-85a) and the reply affidavit of the Super

intendent (App. 90a) to have been effected in part by the

use of geographic attendance standards applied only to

Negroes living in the Caldwell School area following the

conversion of Caldwell to a “Negro” school. This was one

of the matters about which plaintiffs sought leave for dis

covery proceedings (App. 100a).

26

The local regulations of the Greensboro Board contain

a provision (App. 32a) which explicitly provides for the

Board to consider race and for the Board “ on its own

initiative” to change school assignments of children as

signed to a school where children of another race are

admitted, if the parents so desire. Such a system of con

sidering race and transferring students to preserve

segregation on the “ initiative” of the Board is plainly

incompatible with the Board’s duty to end a discrimina

tory system created by segregation practices and racial

standards for school assignment.

In like manner the procedure by which Thetus McCoy

was assigned to a Negro Junior High School, because that

was the “customary school” (90a-91a; 104a-105a) attended

by Negro students in the area, while all white Caldwell

students in the area were assigned to other schools on com

pletion of the sixth grade, demonstrates that complete

relief cannot be obtained through pupil reassignment pro

cedures so long as pupil assignments are made on the basis

of race and in accordance with past customs. It is said

that no application was made by Thetus for a change of

his assignment to the all-Negro school. But on behalf of

Thetus McCoy it must be emphasized that he had com

pleted the administrative procedures the previous year and

still been assigned to a segregated school and excluded

from a school in which white children living in his area

were routinely admitted; at the time the Board newly

assigned him to a Negro junior high school he had filed a

lawsuit and was a litigant before the court seeking relief

in the form of an order prohibiting all racial school as

signments. In Carson v. Warlick, supra, at 729, the Court

observed:

Furthermore, if administrative remedies before a

school board have been exhausted, relief may be sought

27

in the federal courts on the basis laid therefor by

application to the board, notwithstanding time that

may have elapsed while such application was pending.

Here Thetus McCoy laid the basis for seeking relief in

the Federal Court prior to filing suit. He remains in the

school system, assigned to an all-Negro school although

now he has been promoted to a higher level. While he

may not be entitled to an order requiring his admission

to any particular school, it is submitted that he is certainly

still entitled to maintain an action to seek a prohibition

of the policy of assigning and reassigning students on the

basis of racial considerations, and to whatever benefit may

flow to him personally with respect to his individual school

attendance as the result of the abolition of that policy.

Cf. Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, supra.

If the plaintiffs at a trial on the merits are able to estab

lish that assignment policies based upon race have not

ceased in the Greensboro system the cause is surely not

moot. Avery v. Wichita Falls, supra. Indeed, as held by

the Supreme Court in United States v. W. T. Grant Co.,

345 U. S. 629, 632 even the “voluntary cessation of allegedly

illegal conduct does not deprive the tribunal of power to

hear and determine the case, i.e. does not make the case

moot.” (Emphasis supplied.) In such circumstance it was

held that the fact that if the case were dismissed the de

fendant would be “ free to return to his old ways” , “ to

gether with a public interest in having the legality of the

practices settled, militates against a mootness conclusion.”

The Court further said that while “ [t]he case may never

theless be moot if the defendant can demonstrate that

‘there is no reasonable expectation that the wrong will

be repeated!,)’ [t]he burden is a heavy one” (at 632).

Here, however, the “ allegedly illegal conduct” has not even

ceased.

28

It is submitted that the plaintiffs in this eanse are en

titled to a trial on the merits to offer proof that the sys

tem of assigning pupils on racial grounds did exist and

continues to exist in the Greensboro system, and upon such

proof are entitled to general injunctive relief prohibiting

the unlawful racial assignment practices and for a reten

tion of jurisdiction of the cause by the trial court during

any transition to a nondiscriminatory system.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, f o r the fo re g o in g reasons it is resp ectfu lly

subm itted that the ju d gm en t below should be reversed .

J. K e n n e t h L ee

P. 0. Box 645

Greensboro, North Carolina

C onrad 0 . P earson

2031/2 E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

T htjrgood M arshall

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants