Emergency Application for a Stay

Working File

March 13, 2000

9 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Emergency Application for a Stay, 2000. 00ddde93-da0e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/45045fd3-7e81-4217-9517-9cd011806778/emergency-application-for-a-stay. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

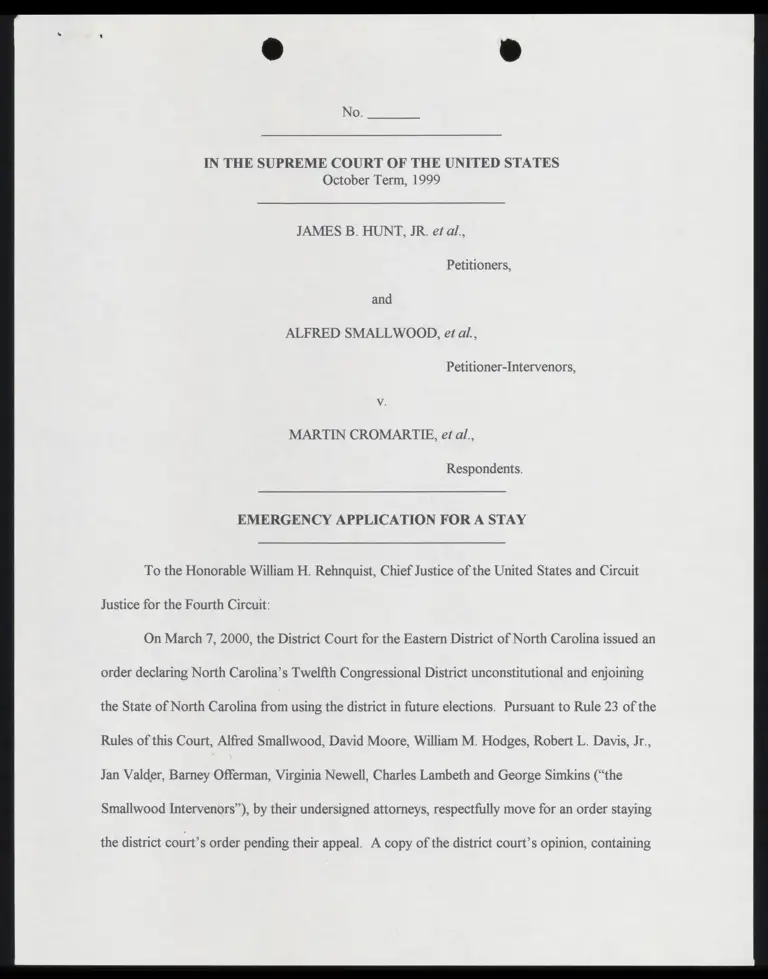

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1999

JAMES B. HUNT, JR. et al,,

Petitioners,

and

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, et al.,

Petitioner-Intervenors,

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.,

Respondents.

EMERGENCY APPLICATION FOR A STAY

To the Honorable William H. Rehnquist, Chief Justice of the United States and Circuit

Justice for the Fourth Circuit:

On March 7, 2000, the District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina issued an

order declaring North Carolina’s Twelfth Congressional District unconstitutional and enjoining

the State of North Carolina foi using the district in future elections. Pursuant to Rule 23 of the

Rules of this Court, Alfred Smallwood, David Moore, William M. Hodges, Robert L. Davis, Jr.,

Jan Valder, Barney Offerman, Virginia Newell, Charles Lambeth and George Simkins (“the

Smallwood Intervenors”), by their undersigned attorneys, respectfully move for an order staying

the district court’s order pending their appeal. A copy of the district court’s opinion, containing

its order and injunction, is contained in Appendix 1 of the State of North Carolina’s emergency

stay application.

fe

ks

M

]

-

Today, the Smallwood Intervenors have also filed a motion for a stay in the district court

however, the court has not yet acted on this motion, nor the request filed by the State March 10,

“le Cue d {use of

2000. As discussed below, this Court should stay the district court’s order because of the

N

irreparable harm to voters (especially minority voters), as well as to the State and candidates

which would result if no stay is granted and because Sap and petitioner-intervenors are

: AN ond

likely to be successful on the TREN! In an effort to not iil he Sorte s emergency

WAH

application for a stay, the Smallwood Intervenors provide additional reasons below for granting a

stay and adopt the Statement of the Case and Statement of the Facts filed by the State in its

emergency stay application.

ADDITIONAL REASONS FOR GRANTING A STAY

Irreparable Harm will Result to the Interests of the Public and to the State if a Stay

is not issued and the Risk of Harm to Plaintiffs is Insignificant

“1 > tlvee” \ whe SUE hes Oey

| ’S Thy in this case, ordering the State to redraw the Twelfth Congressional

——

3

3

3

wn

9 $

5

>

Q)

=

g

3

3

+

-

«

X

/

District, is clearly incorrect as indicated by Judge Thornburg in dissent. See Cromartie v. Hunt

oh

No. 4:96-CV-104-BO(3), slip op. at 20-22 (E.D.N.C. March 7, 2000) (Thornburg, J., concurring

in part and dissenting in part). The injury from disrupting election processes is significant and has

been frequently recognized by this Court and the federal trial courts. In Reynolds v. Sims, 377

Tg Co uw

U.S. 533, 585 (1964), the-Supreme-€Court cautioned that

under certain circumstances, such as where an impending election is imminent and

a State’s election machinery is already in progress, equitable considerations might

justify a court in withholding the granting of immediately effective relief in a

legislative apportionment case, even though the existing apportionment scheme

was found invalid. . . . [A] court is entitled to and should consider the proximity of

a forthcoming election and the mechanics and complexities of state election laws,

and . . . can reasonably endeavor to avoid a disruption of the election process

which might result from requiring precipitate changes that could make

unreasonable or embarrassing demands on a State in adjusting to the requirements

of the court's decree.

These principles have guided federal trial courts in both reapportionment and vote dilution cases.’

The people of North Carolina have a legitimate interest in holding their primary election

on the scheduled date and would suffer from a delay in the timetable. See, e.g., Chisom v.

Roemer, 853 F.2d 1186, 1190 (5th Cir. 1988) (recognizing the uncertainty that delay introduces

into election process). The district court issued its injunction when the election process for the

2000 Congressional elections was already well under way. The filing period for Congressional

candidates began on January 3, 2000 and ended on February 7, 2000. Primary election voting is

scheduled to begin on March 18, 2000 when the absentee voting period begins. The citizens who

filed notices of candidacy, including 43 Congressional candidates, have raised and spent large

See, e.g., Diaz v. Silver, 932 F. Supp. 462, 466 (E.D.N.Y. 1996) (preliminary injunction denied to

avoid harming public interest where elections scheduled in a few months, even though court found

likelihood of success on Shaw claim and irreparable injury to plaintiffs); Cardona v. Oakland Unified

School District, 785 F. Supp. 837, 843 (N.D. Cal. 1992) (court refused to enjoin election where

primary “election machinery is already in gear,” including the passage of deadline for candidates to

establish residency and start of candidate nominating period); Republican Party of Virginia v. Wilder,

774 F. Supp. 400 (W.D. Va. 1991) (injunction denied in case with “uncertain cause of action with

only possible irreparable harm” and where time for election was close and there was danger of low

voter turnout if election postponed); Cosner v. Dalton, 522 F. Supp. 350 (E.D. Va. 1981) (three-

judge court) (use of malapportioned plan not enjoined where elections were two months away);

Shapiro v. Maryland, 336 F. Supp. 1205 (D. Md. 1972) (court refused to enjoin election where

candidate filing deadline was imminent and granting relief would disrupt election process and

prejudice citizens, candidates and state officials); Sincock v. Roman, 233 F. Supp. 615 (D. Del. 1964)

(three-judge court) (per curiam) (enjoining election would result in disruption in ongoing election

process which would cause confusion and possible disenfranchisement of voters); Meeks v. Anderson,

229 F. Supp. 271, 274 (D. Kan. 1964) (three-judge court) (court held malapportioned districts

unconstitutional but concluded that the “ends of justice” would “best be served” by permitting

elections to proceed)

amounts of money for their campaigns and continue to raise and spend funds campaigning for the

contested primary races.

The State has already taken most of the various administrative steps necessary to hold an

election at the public expense. Candidates, North Carolina election officials and voters (including

the Smallwood Intervenors) will suffer significant, substantial and irreparable harm from the

disruption of this election process, such as low voter turnout, voter confusion, additional burdens

. "

. , / # 8 AK y, : ov we

on candidates, and increased costs.’ \ ME ae P va& OO75¢ lr J Ron in

04 ~

AV Xj

These harms prompted the district court inf v. Hunt to deny injunctive relief to

f

plaintiffs in-that-ease in 1996, where only a few months remained before the general election. As

political scientist Dr. Bernard Grofman® testified in that case, altering the State's regular election

calendar, conducting congressional elections without statewide races on the ballot, and

conducting elections in close proximity to each other all contribute to low voter turnout. See

2See Cardona, 785 F. Supp. at 842-43 (1992) (denying relief due to proximity of election); Banks v.

Board of Educ. of Peoria, 659 F. Supp. 394, 398 (C.D. Ill. 1987) (“the candidates had already begun

campaigning, forming committees to raise funds, making decisions about political strategy, and

spending money for publicity purposes”); Knox v. Milwaukee County Bd. of Election Comm'rs, 581

F. Supp. 399, 405 (E.D. Wis. 1984) (“candidates' election reports have been filed, campaign

committees organized, contributions solicited, . . . literature distributed); Martin v. Venables, 401 F.

Supp. 611, 621 (D. Conn. 1975) (denying relief where parties had selected their endorsed candidates

and time for challengers to qualify for primaries had passed); Dobson v. Mayor and City Council of

Baltimore, 330 F. Supp. 1290, 1301 (D. Md. 1971) (disrupting election schedule would mean present

candidates would lose, in large measure, the benefit of their campaigning to date); Klahr v. Williams,

313 F. Supp. 148, 152 {poe 1970) (redistricting where filing deadline was less than two months

away would involve serious risk of confusion and chaos), aff'd sub nom. Ely v. Klahr, 403 U.S. 108,

113 (1971).

Dr. Grofman has been accepted as an expert in the areas of political participation and voting rights

by numerous federal district courts. His work has also been often cited by federal courts in cases

related to districting, including |Thornburgh v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) and Shaw v. Reno, 509

U.S. 630 (1993).

-

4

Expert Witness Declaration in Shaw v. Hunt, Bernard N. Grofman, Ph.D., July 24, 1996, at 6,

attached hereto as Appendix 1. According to Dr. Grofman, this result is exacerbated for minority

groups, such as African Americans, because they tend to be poorer and less well educated than

their white counterparts, and, consequently, tend to have lower levels of political participation.

See id. at 9. This analysis caused Dr. Grofman to conclude in Shaw that “even if it were

technically feasible that a new congressional plan could be drawn (either by the legislature or by

the [district] court) and implemented within the next few months, any attempt to hold primary

elections between now [July 24, 1996] and the November 5, 1996, election date under that plan

would result in primary elections with especially low turnout,” id. at 12, and would be “a potential

source of considerable voter confusion,” 7 at 13.

Ab g.2 A (Aq < )

The district court in Shaw accordingly refused to disrupt North Carolina’s election process

~~

on remand from this Court’s 1996 decision even after a finding by the Supreme Court that the

Congressional plan was unconstitutional. The decision of the Shaw district court to permit

elections to Hi dad fron under a plan found unconstitutional is supported by Supreme Court

10g C ~oted =

precedent. pe rE oa 57 77 U.S. at 585 (“[U]nder certain circumstances, such as where an

impending election is imminent and a State’s election machinery is already in progress, equitable

considerations might justify a court withholding the granting of immediately effective relief in a

legislative apportionment case, even though the existing apportionment scheme was found

invalid”). See also Watkins v. Mabus, 502 U.S. 954 (1991); Republican Party of Shelby County

v. Dixon, 429 U.S. 934 (1976); Ely v. Klahr, 403 U.S. 108 (1971).

The same undesirable effects, especially for minority voters, will inevitably result if the

of Ye tout he low

~distriet-court’s order is not stayed. The order will nullify the efforts of candidates to date and

Ne

result in lower voter participation and considerable confusion in any rescheduled elections.

These harms are exacerbated by the timing and scope of the district court decision. This

presents a separate, but related basis for granting a stay in this case. This Court issued its decision

in Hunt v. Cromartie, 526 U.S. |, 119 S. Ct. 1545 (1999) in May, 1999. However, despite

the urgency of the State’s election schedule, the district court did not issue its discovery schedule

\agq

until August 23,2000, three months after this Court’s decision. In its order, the court set

discovery to conclude on an expedited basis by October 2, 1999 and scheduled the case for trial in

November, 1999. Despite making it very clear during the trial that they understood the time

pressures of the State’s election schedule and that candidates would begin filing for offices in

January, the court waited over three months to issue its opinion after expediting trial. In the time

te i cond

that this-Court took to issue its opinion, candidates filed to run in and the State proceeded to

prepare for the May 2, 2000 primary. While this case presents complex issues that may require

significant time to analyze, the role of the district court in contributing to the potential electoral

disruption in this case presents another reason for a stay.

Moreover, the district court’s decision is coming on the eve of the 2000 redistricting. In

just over one year, the Census Bureau will release the 2000 Census data and the State will begin

the redistricting process, a process that inevitably will result in at least some Congressional

districts being redrawn. To require the State to engage in the disruptive process now only to

repeat it in another year would be unduly burdensome and duplicative. Moreover, redistricting

now would require the use of 1990 data which is less accurate and less reflective of North

Carolina’s year 2000 population. Rather than engaging in a disruptive redistricting process that

Spin a a. x Shaadi af

will invariably produce districts drawn according to inaccurate data, this Court would be i Cle

lu Cove of lS Lee of

consistent with well-established precedent to allow the State to proceed a pace with the 2000

rr

elections under the current plan.

Indeed, given the timing of this case, the irreparable injury to the public and the

Trudy ol (AS

Smallwood Intervenors far .out-ways that of the plaintiffs in this case. In City of Alexandria, the

Fourth Circuit concluded that “the public interest would be served by granting the stay” in that

case “even though plaintiffs as a practical matter may suffer a binding and final defeat through the

granting of the stay. . . .” City of Alexandria, 719 F.2d at 700. The court interpreted

vb J 44 “irreparable injury” “to mean more than any injury that cannot be wholly recompensated or

eradicated. Both the extent of injury and the consequences over the long ferm must likewise be

taken into account.” Id. (emphasis added). As the next redistricting cycle is imminent, granting a

stay would not permanently prevent plaintiffs from acquiring the remedy they seek: a new

redistricting plan. If during or after the 2000 redistricting cycle, plaintiffs are not satisfied with

the new plan, they may participate in the process of creating a more palatable plan or challenge

the constitutionality of the plan subsequently. The reasoning of the court in Dickinson v. Indiana

State Election Bd., 933 F.2d 497, 502 (7th Cir. 1991) is instructive:

The district court also concluded that, on equitable grounds, the pending 1991

redistricting (based on the 1990 census) makes entry of relief inappropriate. The

district court did not err in making this finding. The legislative reapportionment is

imminent, and Districts 49 and 51 may well be reshuffled. The legislature should

now complete its duty, after which the plaintiffs can reassess whether racial bias

still exists and seek appropriate relief.

Furthermore, this is consistent with the most recent decisions of district courts that have

considered constitutional challenges to redistricting plans late in the decade. See, e.g., Maxwell v.

Foster, No. 98-1378, slip op. at 7 and 8 (W.D. La. Nov. 24, 1999) (district court granting State

of Louisiana’s motion for summary judgment and finding that “rapid-fire reapportionment

immediately prior to a scheduled census would constitute an undue disruption of the election

process, the stability and continuity of the legislative system and would be highly prejudicial, not

only to the citizens of Louisiana, but to the state itself”), attached hereto as Appendix 2.

Therefore, the long term harm to plaintiffs is not as significant as the current injury to the public

and the State if this stay is not granted.

IL Movants are Likely to Succeed on the Merits

Judge Thornburg is correct in his analysis of the merits of this case. See Cromartie v.

Hunt, No. 4:96-CV-104-BO(3), slip op. at 3-19 (E.D.N.C. March 7, 2000) (Thornburg, J.,

concurring in part and dissenting in part). In moving for a stay, it is not the Smallwood

Intervenors’ burden to show a certain probability of success on the merits, but only present a

substantial case on the merits when a serious legal question is involved and the equities weigh in

ek favor of a stay. See Ruiz v. Estelle, 650 F.2d 555, 565 (5th Cir. 1981); see also, Wildman v.

yal

[>

Berwick Universal Pictures, 983 F.2d 21 (5th Cir. 1992); Nat'l Treasury Employees Union v.

Von Raab, 808 F.2d 1057, 1059 (5th Cir. 1987); U.S. v. Baylor Univ., 711 F.2d 38, 39 (5th Cir.

1983). The existence of a well-reasoned dissent indicates a substantial chance that defendants will

prevail on the merits. {i}

Hie UNC helaw

For the reasons Judge Thornburg states, this-Court should not have applied strict scrutiny

to the North Carolina General Assembly’s decision to create the Twelfth Congressional District.

This Court was incorrect as a matter of law to declare the Twelfth Congressional District

unconstitutional. This provides a sound basis to conclude that the Defendants and Defendant-

intervenors will succeed on the merits. In addition, as discussed above, the timing and scope of

this Court’s remedy is also at issue and provides an independent basis for Defendants and

Defendant-intervenors’ success on the merits in this case.

| (

ION 4, rue CONCLUS #5 ht ber, . {ict a

{ D

For the reasons set forth herein, the Smallwood Ytervenord Yevpectiilily request that this

I~

Court stay the district court order declaring North Carolina’s Twelfth Congressional District

unconstitutional and enjoining the State of North Carolina from using the district in future

elections. They also join in the State’s Emergency Application for Stay Pending Appeal of the

Decision of the Three-Judge Court for the United States District Court for the Eastern District of

North Carolina.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE R. JONES ADAM STEIN

Director-Counsel and President Ferguson, Stein, Wallas, Adkins

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN Gresham & Sumter, P.A.

NAACP Legal Defense and 312 West Franklin Street

Educational Fund, Inc. Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27516

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600 (919) 933-5300

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

TODD A. COX

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1444 1 Street, N.W., 10th Floor

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

This 13th day of March, 2000.