Smith v Drew City Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1965

23 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Drew City Brief for Appellant, 1965. f80c0ca3-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4504dee3-43c7-43b2-8914-ff1c59305e36/smith-v-drew-city-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

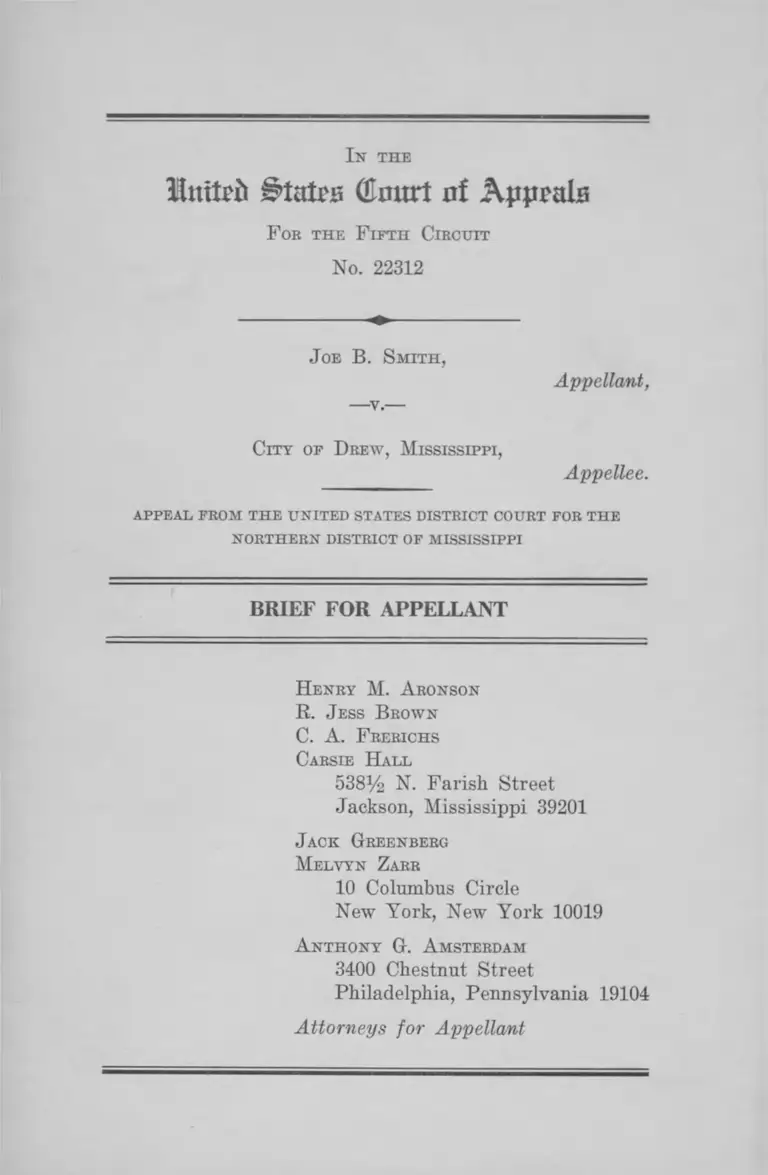

Mmteii i>tatp£ (Em irt of A jip ra la

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 22312

In the

J oe B. Smith,

Appellant,

City of Drew, Mississippi,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM TH E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

NORTH ERN DISTRICT OF M ISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

H enry M. A ronson

R. Jess B rown

C. A. F rerichs

Carsie Hall

538% N. Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

J ack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ..................................................... 1

Specification of E rro r ....................................................... 3

A rgument

I. Appellant’s Removal Petition Adequately States

a Case for Removal Under 28 U. S. C. §1443 ..... 4

II. Appellant’s Removal Petition Was Timely Filed 12

Conclusion ......................................................................... 14

Statutory A ppendix ............................................................. la

Table of Cases

Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Supp. 626 (E. D. Ark.

1963) ................................................................................. 5

Braun v. Sauerwein, 77 U. S. (10 Wall.) 218 (1869) .... 5

Cleary v. Bolger, 371 U. S. 392 (1963) .......................... 13

Colorado v. Maxwell, 125 F. Supp. 18 (D. Colo. 1954),

leave to file petition for prerogative writs denied

sub nom. Colorado v. Knous, 348 U. S. 941 (1955) .... 5

Colorado v. Symes, 286 U. S. 510 (1932) ........................ 5

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965) .......................... 5, 6

Dombrowski v. Pfister,------ U. S . ------- , 33 U. S. Law

Week 4321, April 26, 1965 .........................................10,12

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) ....... 5

Ex parte Dierks, 55 F. 2d 371 (D. Colo. 1932), manda

mus granted on other grounds sub nom. Colorado v.

Symes, 286 U. S. 510 (1932)

PAGE

5

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963) ............... 5

Hague v. CIO, 307 U. S. 496 (1939) .............................. 5

Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964) ................... 5

Hodgson v. Millward, 3 Grant (Pa.) 412 (1863) ........... 5

Hodgson v. Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. 285 (No. 6568)

(E. D. Pa. 1863) ............................................................. 5

In re Duane, 261 Fed. 242 (D. Mass. 1919) ................... 12

Knight v. State, 161 So. 2d 521 (1964), reversed sub

nom. Thomas v. Mississippi,------ U. S .------- , 33 U. S.

L. W. 3349 (April 26, 1965) .......................................... 9

Logeman v. Stock, 81 F. Supp. 337 (D. Neb. 1949) .... 5

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U. S. 145 (1965) ....... 11

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ........................ 10

Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110 (5th Cir. 1963) ...... 10

New York v. Galamison, ------ F. 2d ------ , 2d Cir.,

Nos. 29166-75, Jan. 26, 1965, cert. den. ------ U. S.

------ , April 26, 1965 ........................................................ 5

Potts v. Elliott, 61 F. Supp. 378 (E. D. Ky. 1945) ..... 5

Pugach v. Dollinger, 365 U. S. 458 (1961) ................... 13

Rachel v. Georgia, 5th Cir., No. 21354, March 5, 1965.... 2, 4

Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117 (1951) ................... 13

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880) .......... 7

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880) ..........6,10

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 (1931) ........... 10

11

PAGE

m

Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257 (1880) ....................... 5

United States v. Clark, S. D. Ala. C. A., No. 3438-64,

decided April 16, 1965 .................................................. 6

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5tk Cir. 1961),

cert. den. 369 U. S. 850 (1962) .................................... 5

Statutes Involved

28 U. S. C. §74 (1940) ....................................................... 12

28 U. S. C. §1443 ............................................................... 3, 4

28 U. S. C. §1443(1) ..........................................................6,10

28 U. S. C. §1443(2) .......................................................... 5

28 U. S. C. §1446(b) .......................................................... 13

28 U. S. C. §1446 (c) ....................................................... 12,13

42 U. S. C. §1971 .............................................................4, 5, 6

42 U. S. C. §1983 ........................................................... 4, 6,12

Habeas Corpus Suspension Act of 1863 ....................... 5

La. Const., Art. VIII, § l(d ) ............................................ 11

Miss Code Ann., 1942, §2089.5 (Supp. 1964) .......1, 3, 6, 8,10

Miss. Code Ann., 1942, §1762 (Supp. 1964) ..................... 11

Miss. Code. Ann., 1942, §1762-01 (Supp. 1964) ................ 11

Miss. Code. Ann., 1942, §1202 .......................................... 12

Miss. Constitution, §241-A .............................................. 11

Miss. Constitution, §244 .................................................... 11

PAGE

In the

llmtrii States GJmtrt of Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 22312

J oe B. Smith,

Appellant,

—v.—

City of Drew, Mississippi,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM TH E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

NORTH ERN DISTRICT OF M ISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of United States District

Judge Claude F. Clayton, remanding to the Mississippi

court from which appellant had removed it a criminal pros

ecution related to attempts by Negro citizens of the City

of Drew, Mississippi to register to vote free of racial dis

crimination.

On August 20, 1964, appellant filed in the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi his

verified petition for removal (R. 2-10). The removal pros

ecution involved a charge of disturbance of the peace, in

violation of Miss. Code Ann., 1942, §2089.5 (1964 Supp.),

set out, infra, la. On September 8, 1964, appellee’s motion

to remand to the Circuit Court of Sunflower County, Missis

2

sippi, was filed (R. 12-14). The motion to remand chal

lenged the sufficiency of the removal petition on its face

(R. 13-14). Judge Clayton held no evidentiary hearing,

but considered appellee’s motion to remand on briefs of

the parties. On December 30, 1964, Judge Clayton entered

an order remanding the case to the Circuit Court of Sun

flower County on the grounds that “ [tjhere is no valid claim

that any state statutory or constitutional provision will

result in the denial of defendant’s equal civil rights on the

trial of this case in the state court” (R. 21).

Since the prosecution was remanded without hearing on

the jurisdictional facts, the factual allegations of the re

moval petition must be taken as true for purposes of this

appeal (Rachel v. Georgia, 5th Cir., No. 21354, decided

March 5, 1965). Those allegations are as follows.

Appellant Joe B. Smith is a white citizen of the United

States and of the State of New York. On August 13, 1964,

at approximately 7 :00 p.m., appellant was engaged in con

versation with Glenn Moore and Willie Saunders, Negro

residents of the City of Drew, Mississippi in the Hunter

High School playground in Drew (R. 2). Appellant was

active in an attempt to encourage Negro citizens of the

State of Mississippi to register to vote free of racial dis

crimination and was and is a member of the Council of

Federated Organizations, an unincorporated association of

persons engaged in seeking by lawful means the equal rights

of Negroes and all persons in the State of Mississippi and

the United States (R. 2). Appellant had been engaged in

conversation for about three minutes when he was ap

proached by C. E. Floyd, Chief of Police of the City of

Drew, and advised that he was under arrest for “ trespass

ing on school property” (R. 3).

3

On August 14, 1964, appellant was tried before W. O.

Williford, Mayor and Justice of the Police Court of the

City of Drew, and was convicted of disturbance of the peace

in violation of Mississippi Code Ann., 1942, §2089.5 (1964

Supp.), and sentenced to 90 days’ imprisonment and fined

the sum of three hundred dollars (R. 3). Appellant ap

pealed to the Circuit Court of Sunflower County for trial

de novo by posting an appeal bond in the sum of five

hundred dollars (R. 3).

Appellant’s arrest and subsequent prosecution were and

presently are being carried out with the purpose and effect

of harassing him and punishing him for his attempt to

exercise—and to encourage others to exercise— constitu

tionally protected rights, particularly the right to register

to vote free of racial discrimination (R. 6).

Judge Clayton’s remand order and stay pending appeal

were entered December 30, 1964 (R. 20-22); notice of ap

peal was timely filed January 9,1965 (R. 23).

Specification of Error

The court below erred in holding that appellant’s petition

for removal did not state a removable case under 28

U. S. C. §1443.

4

A R G U M E N T

I.

Appellant’s Removal Petition Adequately States a

Case for Removal Under 28 U. S. C. §1443.

“ I f a petition for removal states sufficient in the way of

allegations to support proof of adequate grounds for re

moval, it is to be treated in the same manner as a com

plaint in federal court.” Rachel v. Georgia, 5th Cir., No.

21354, decided March 5, 1965, slip opinion at p. 8. “ Unless

there is patently no substance in [the] . . . allegation, a

good claim for removal has been stated.” Id. at p. 9.

A. The Removal Petition Is Sufficient Under 28 U. S. C.

§14 43(2 ).

Appellant’s petition adequately alleges that he is prose

cuted for acts under color of authority of federal laws pro

viding for equal civil rights (R. 5-6, 8). See appellant’s

Appendix Brief, Parts IIA, C, filed herewith.1 The laws

providing for equal civil rights which appellant invokes are

42 U. S. C. §1971 (protecting the right to vote free of racial

discrimination and to peacefully encourage others to do

so) and 42 U. S. C. §1983 (protecting the First-Fourteenth

Amendment right of freedom of expression and the federal

privilege and immunity of supporting the right of Negro

citizens to register to vote in state and federal elections

free of the racial discrimination proscribed by 42 U. S. C.

1 Because counsel for appellant are counsel in numerous cases

pending in this Court which raise virtually identical issues of con

struction of 28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958), appellant has sought leave

of the Court to include the arguments common to all cases in an

Appendix Brief, to be filed in all.

5

§1971), discussed in appellant’s Appendix Brief, Parts

IIA, B (l) . On the facts alleged in the removal peti

tion, there can be no doubt that the conduct for which ap

pellant is prosecuted is colorably2 protected by the First-

Fourteenth Amendments, Edwards v. South Carolina, 372

U. S. 229 (1963); Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44

(1963); Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964); Cox v.

Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965); and constitutes an exercise

of the federal privilege and immunity of supporting the

efforts of Negro citizens to register to vote free of racial

discrimination, cf. Hague v. CIO, 307 U. S. 496 (1939). The

acts of appellant to support others in attempting to register

to vote are also protected by 42 U. S. C. §1971. See United

States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961), cert. den.

2 A state defendant petitioning for removal under §1443(2) is

not required to show that he is protected by federal law : that ques

tion is the issue on the merits after removal jurisdiction has been

sustained. On the preliminary question of jurisdiction, it should

be sufficient to show colorable protection. This is the rule in fed

eral-officer removal cases, e.g., Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257,

261-62 (1880); Potts v. Elliott, 61 F. Supp. 378, 379 (E. D. Ky.

1945) (civil case); Logemann v. Stock, 81 F. Supp. 337, 339

(D. Neb. 1949) (civil case); Ex parte Dicrks, 55 F. 2d 371, 374

(D. Colo. 1932), mandamus granted on other grounds sub nom.

Colorado v. Siymes, 286 U. S. 510 (1932) ; Colorado v. Maxwell,

125 F. Supp. 18, 23 (D. Colo. 1954), leave to file petition for pre

rogative writs denied sub nom. Colorado v. Knous, 348 U. S. 941

(1955), and it was so held under the Habeas Corpus Suspension

Act of 1863 removal provisions, on which the removal section of

the Civil Eights Act of 1866, now 28 U. S. C. §1443(2) (1958), was

based. See Hodgson v. Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. 285 (No. 6568)

(E. D. Pa. 1863) (civil case). The facts of the case appear in

Hodgson v. Millward, 3 Grant (Pa.) 412 (Strong, J at nisi prius,

1863), and Justice Grier’s decision is approved in Braun v. Sauer-

wein, 77 U. S. (10 Wall.) 218, 224 (1869). New York v. Galamison,

2d Cir., Nos. 29166-75, decided January 26, 1965, cert, den., ------

U. S .------ , April 26, 1965, takes this view, in dictum, under present

§1443(2). Slip opinion at p. 976. Compare Arkansas v. Howard,

218 F. Supp. 626 (E. D. Ark. 1963), where defendant was unable

to make a colorable showing.

6

369 U. S. 850 (1962); United States v. Clark, S. D. Ala.

C. A., Xo. 3438-64, decided April 16, 1965 (three-judge Dis

trict Court). For these reasons, prosecution for those acts

is removable.

B. The Removal Petition Is Sufficient Under 28 U. S. C.

§14 43(1 ).

Appellant’s petition adequately alleges that he is denied

and cannot enforce in the Mississippi state courts rights

under federal laws providing for equal civil rights (E. 6-10).

See appellant’s Appendix Brief, Parts IIA, B. The rights

claimed are those enumerated in the preceding paragraph

under the First, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments,

and 42 U. S. C. §§1971, 1983, discussed in appellant’s Ap

pendix Brief, Parts IIB (l).

Appellant relies upon Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U. S. 303 (1880) (see appellant’s Appendix Brief, Part

H B (2 )), since the state statute under which appellant is

prosecuted is offensive to the Constitution of the United

States.

Miss. Code Ann., 1942, §2089.5 (1964 Supp.), under which

appellant is prosecuted, is unconstitutionally vague. Cox

v. Louisiana., 379 U. S. 536, 551-52 (1965). In Cox, the

Supreme Court of the United States struck down for over-

breadth a Louisiana statute which provided, in relevant

part:

Whoever with intent to provoke a breach of the

peace, or under circumstances such that a breach of

the peace may be occasioned thereby . . . crowds or

congregates with others . . . in or upon . . . a public

street or public highway, or upon a public sidewalk, or

7

any other public place or building . . . and who fails

or refuses to disperse and move on . . . when ordered

so to do by any law enforcement officer of any munici

pality, or parish, in which such act or acts are com

mitted, or by any law enforcement officer of the state

of Louisiana, or any other authorized person . . . shall

be guilty of disturbing the peace. La. Rev. Stat.

§14:103.1 (Cum. Supp. 1962).

The Court held that impermissible vagueness inhered in the

phraseology “with intent to provoke a breach of the peace,

or under circumstances such that a breach of the peace

may be occasioned”, saying (379 U. S. at 551-52):

The Louisiana Supreme Court in this case defined the

term “breach of the peace” as “ to agitate, to arouse

from a state of repose, to molest, to interrupt, to hin

der, to disquiet.” 244 La., at 1105, 156 So. 2d, at 455.

[This] definition would allow persons to be punished

merely for peacefully expressing unpopular views.

Yet, a “ function of free speech under our system of

government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best

serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of

unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they

are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often

provocative and challenging. It may strike at preju

dices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling

effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is

why freedom of speech . . . is . . . protected against

censorship or punishment . . . There is no room under

our Constitution for a more restrictive view. For the

alternative would lead to standardization of ideas either

by legislatures, courts, or dominant political or com

8

munity groups.” Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1,

4-5. In Terminiello convictions were not allowed to

stand because the trial judge charged that speech of

the defendants could be punished as a breach of the

peace “ ‘if it stirs the public to anger, invites dispute,

brings about a condition of unrest, or creates a dis

turbance, or if it molests the inhabitants in the enjoy

ment of peace and quiet by arousing alarm.’ ” Id., at 3.

The Louisiana statute, as interpreted by the Louisiana

court, is at least as likely to allow conviction for inno

cent speech as was the charge of the trial judge in

Terminiello. Therefore, as in Terminiello and Edwards

[v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963)] the convic

tion under this statute must be reversed as the statute

is unconstitutional in that it sweeps within its broad

scope activities that are constitutionally protected free

speech and assembly. Maintenance of the opportunity

for free political discussion is a basic tenet of our con

stitutional democracy. As Chief Justice Hughes stated

in Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359, 369: “ A

statute which upon its face, and as authoritatively con

strued, is so vague and indefinite as to permit the pun

ishment of the fair use of this opportunity is repug

nant to the guaranty of liberty contained in the

Fourteenth Amendment.”

The same degree of impermissible vagueness inheres in

§2089.5, since it punishes “ [a]ny person who disturbs the

. . . peace of others . . . by conduct either calculated to pro

voke a breach of the peace, or by conduct which may lead

to a breach of the peace, or by any other act. . . . ”

9

As construed by the Supreme Court of Mississippi, the

term “ breach of the peace” reaches federally protected

activities that create unrest in others, such as the effort of

a racially mixed group to enter and remain in a white

waiting room in a bus terminal. Kniglit v. State, 161 So. 2d

521 (1964), reversed per curiam, sub nom. Thomas v. Mis

sissippi, ------ U. S. ------ , 33 U. S. L. W. 3349 (April 26,

1965). In Knight, the Supreme Court of Mississippi found

a “breach of the peace” in the following circumstances (161

So. 2d at 522):

When the [Negro] defendant and her [racially

mixed] group of seven others, after disembarking

from the bus, entered the west (white) waiting room

of the Terminal, the mood of the fifty people, including

some newspapermen, on the inside, immediately

changed. It became “ ugly and nasty” . The people be

gan to move in and toward the group. The officers saw

expressions on the faces of the people and heard their

talk about this crowd and their accusations that the

group were a bunch of agitators and trouble makers.

The defendant used no vulgar or indecent language

and made no unusual gestures; but she appeared to

be afraid. At no time did she advise the officers that

she had business in the waiting room nor did she

assert any claim that she was exercising her right of

free speech or any other right.

Captain Ray, seeing the change in the attitude of

the people, and deeming that the defendant and her

group were the root of the trouble, and believing that,

under the circumstances then existing, a breach of the

peace was about to occur, twice ordered the defendant

10

and the other members “ to move on” . When they re

fused, he arrested all of them.

The Supreme Court of the United States has consistently

warned that, where freedom of expression is involved, vague

penal laws cannot be tolerated. Stromberg v. California,

283 U. S. 359, 369 (1931); NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S.

415, 433 (1963); Dombrowski v. Pfister, ------ U. S. ------ ,

33 U. S. L. W. 4321 (April 26, 1965). One important rea

son for this ban is that statutes such as §2089.5 provide

law enforcement officers with a blank check; in effect,

§2089.5 gives a policeman discretion to arrest any person

in a public place whom he finds objectionable. Thus, a

person may be forced not only to relinquish his constitu

tional rights, but may also be forced to answer criminally

for their exercise. As this Court recognized in Nesmith

v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110, 121 (5th Cir. 1963):

[LJiberty is at an end if a police officer may without

warrant arrest, not the persons threatening violence,

but those who are its likely victims, merely because the

person arrested is engaging in conduct which, though

peaceful and legally and constitutionally protected, is

deemed offensive and provocative to settled social cus

toms and practices. When that day comes . . . the

exercise of [First Amendment rights] must then con

form to what the conscientious policeman regards the

community’s threshold of intolerance to be.

In addition, appellant’s case is removable under 28

U. S. C. §1443(1) as construed in Strauder v. West Vir

ginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880), because appellant is denied

and cannot enforce in the state courts his right to trial by

a jury from which Negroes are not discriminatorily ex

11

eluded. By force of the holding3 in Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U. S. 145 (1965), certain of Mississippi’s con

stitutional provisions governing the qualifications of elec

tors4 are void on their face, and hence Miss. Code Ann., 1942,

§1762 (Supp. 1964), which, in effect, qualifies only electors

as jurors,5 is equally facially unconstitutional.

Finally, appellant’s removal petition contained the alle

gation, which Judge Clayton assumed to be true for pur

poses of his decision, that the arrest and prosecution of

appellant “have been and are being carried on with the

sole purpose and effect of harassing [appellant] and of

punishing him for, and deterring him from, exercising his

constitutionally protected rights . . . ” (R. 6). Such an

3 The Supreme Court struck down Louisiana’s voter registration

laws because they vested in the registrars discretion to determine

the qualifications of applicants for registration circumscribed by

no definite or objective standards for the registration process. The

Louisiana laws provided, inter alia, that an applicant “be able to

understand and give a reasonable interpretation of any section of

[the United States or Louisiana] Constitution when read to him by

the registrar.” La. Const. Art. VIII, § l (d ) .

4 Mississippi Constitution §244, in relevant part:

Every elector shall, in addition to the foregoing qualifica

tions be able to read and write any section of the Constitu

tion of this State and give a reasonable interpretation

thereof to the county registrar. He shall demonstrate to

the county registrar a reasonable understanding of the duties

and obligations of citizenship under a constitutional form

of government . . . .

Mississippi Constitution, §241-A:

In addition to all other qualifications required of a person

to be entitled to register for the purpose of becoming a quali

fied elector, such person shall be of good moral character.

5 Miss. Code Ann., 1942, §1762 (Supp. 1964):

Every male citizen not under the age of twenty-one (21)

years, who is either a qualified elector or a resident free

holder of the county for more than one year . . . is a com

petent juror . . . .

Resident freeholders may be qualified as jurors only pursuant to

special judicial proceedings in the circuit courts. Miss. Code Ann

1942, §1762-01 (Supp. 1964).

12

allegation has been held to state a valid claim under 42

U. S. C. §1983. Dombrowski v. Pfister,------U. S . ------- , 33

U. S. L. W. 4321, 4324 (April 26, 1965). In Dombrowski,

the United States Supreme Court held that federal courts

should enjoin state prosecutions brought “ to impose con

tinuing harassment in order to discourage [civil rights]

activities.” Thus, the Supreme Court recognized a “ right”

of citizens to be free of bad faith or harassment prosecu

tions; such a right is eo ipso “denied” by prosecution.

II.

Appellant’s Removal Petition Was Timely Filed.

Appellant’s removal petition was filed “ before trial”

within the meaning of 28 U. S. C. §1446(c), since it was

filed before appellant’s trial de novo in the circuit court.6

This is demonstrated by the legislative history of 28 U. S. C.

§1446(c). Prior to 1948, the civil rights removal provisions

pertaining to criminal prosecutions allowed the filing of a

removal petition “ at any time before the trial or final

hearing-----” 7 Under these provisions, removal was timely

if effected subsequent to a summary trial but prior to a

trial de novo.8 The 1948 revisers apparently intended no

change, since the purposes of the removal acts in criminal

6 Mississippi law permits a trial de novo in a court of record

after summary trial in a court of no record. Miss. Code Ann. 1942,

§1202.

7 Rev. Stat. §641; Judicial Code §31 (1911); 28 U. S. C. §74

(1940). The original provision, Act of April 9, 1866, §3, 14 Stat.

27, had adopted the procedure of the Act of March 3, 1863, §5,

12 Stat. 755, 756, which, as amended by the Act of May 11, 1866,

§3, 14 Stat. 46, allowed removal “ before a jury is empanelled.”

8 In re Duane, 261 Fed. 242 (D. Mass. 1919).

13

cases might be thwarted if a defendant could be “ rushed

into trial in State courts before [a] petition for removal

could be filed” 9 (Historical and Revision Notes to 28

U. S. C. §1446(c)). The revisers said: “ Words ‘or final

bearing’ following the words ‘before trial’, were omitted

for purposes of clarity and simplification of procedure.” 10

The allowance of removal prior to trial de novo is sup

ported by policy as well as legislative history. If a state

trial has actually begun, interests of comity, efficiency of

judicial administration and avoidance of piecemeal litiga

tion dictate against federal intervention.11 But when a

defendant is accorded a trial de novo and removes his

case prior to the commencement of trial, no such interests

bar the way to retention of federal jurisdiction.

9 This is exactly what happened in this case: appellant was

rushed into state court trial the day after his arrest (R. 2-3, 15-16).

10 This revision note may be contrasted with the note to §1446(b ),

governing civil cases, where a change of law was clearly intended.

11 See Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117, 120, 123-24 (1951);

Pugach v. Bollinger, 365 U. S. 458 (1961); Cleary v. Bolger, 371

U. S. 392,401 (1963).

14

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the order of the district

court remanding appellant’s case should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Henry M. A ronson

R. Jess Brown

C. A. F rerichs

Carsie Hall

538% N. Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Jack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Appellant

Certificate o f Service

T his is to certify that on May ....... , 1965, I served a

copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellant and Appendix

Brief for Appellant upon P. J. Townsend, Jr., Esq.,

attorney for appellee, by mailing a copy thereof to him,

c/o Townsend and Welch, 111 South Main Street, Drew,

Mississippi, by United States mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellant

A P P E N D I X

la

STATUTORY APPENDIX

28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958):

§1443. Civil rights cases

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prose

cutions, commenced in a State court may be removed

by the defendant to the district court of the United

States for the district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot

enforce in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the juris

diction thereof;

(2) For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights, or for re

fusing to do any act on the ground that it would be

inconsistent with such law.

Miss. Code Ann., 1942, §2089.5:

§2089.5. Disturbance of the public peace, or the peace

of others.

1. Any person who disturbs the public peace, or the

peace of others, by violent, or loud, or insulting, or

profane, or indecent, or offensive, or boisterous con

duct or language, or by intimidation, or seeking to in

timidate any other person or persons, or by conduct

either calculated to provoke a breach of the peace, or

by conduct which may lead to a breach of the peace,

or by any other act, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor,

2a

and upon conviction thereof, shall be punished by a fine

of not more than five hundred dollars ($500.00), or by

imprisonment in the county jail not more than six (6)

months, or both.

2. The provisions of this act are supplementary to

the provisions of any other statute of this state.

3. I f any paragraph, sentence or clause of this act

shall be held to be unconstitutional or invalid, the

same shall not affect any other part, portion or pro

vision thereof, but such other part shall remain in full

force and effect.

Sources : Laws, 1960, ch. 254, §§1-3.

38