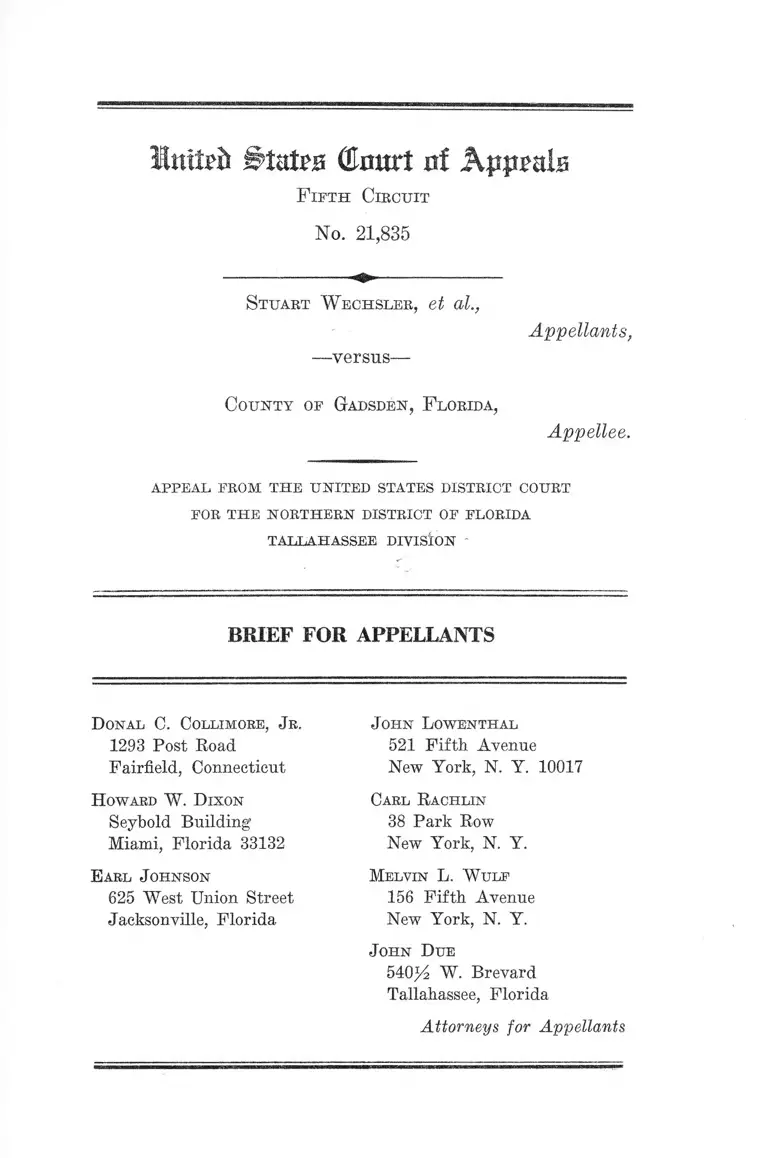

Wechsler v. County of Gadsden, Florida Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 16, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wechsler v. County of Gadsden, Florida Brief for Appellants, 1965. a1c13ad4-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/45214ea0-1d2f-4be3-abec-83f18d99b97a/wechsler-v-county-of-gadsden-florida-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Imtrfr Btdtm (Burnt ui Appeals

F if t h C ibcitit

No. 21,835

S t u a r t W e c h s l e r , et al.,

—versus—

Appellants,

C o u n t y of G ad sd en , F lo rid a ,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

TALLAHASSEE DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

D onal C. Collimoee, Jr.

1293 Post Road

Fairfield, Connecticut

H oward W. D ixon

Seybold Building

Miami, Florida 33132

Earl J ohnson

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida

J ohn L owenthal

521 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10017

Carl Rachlin

38 Park Row

New York, N. Y.

Melvin L. W ulf

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y.

John D ue

540% W. Brevard

Tallahassee, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case .................................................... 1

Specifications of Error ................................................. - 4

A r g u m e n t

I. The District Court was required to retain juris

diction upon the allegations set forth in the re

moval petitions ............ 5

II. The prosecutions of appellants should be dis

missed without further proceedings in the Dis

trict Court, or, in the alternative, should be

enjoined................................................................... 13

III. Appellants are at least entitled to a hearing on

the allegations of their verified removal peti

tions ...................................................................... 14

IY. The authority cited by the District Court does

not support the orders of remand........................ 15

C o n c l u s io n .................................................. 16

A p p e n d ix of F lo rida S t a t u t e s ....................................... 19

T able of A u t h o r it ie s

Cases:

Baines v. City of Danville, 337 F. 2d 579 (4 Cir. 1964) .. 13

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186 (1962) ........................... 10

PAGE

11

Bouie v. Columbia, 378 U. S. 347 (1964) ...................... 12

Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F. 2d 401 (5 Cir. 1961) ........... 9

Council of Federal Organizations v. Bainey,------F. 2d

------(5 Cir. 1964), No. 21795, decided Dec. 28, 1964 .. 14

Dresner, et al. v. Municipal Judge, City of Tallahassee,

------- F. 2 d ------ , decided Aug. 5, 1964 ..... ................ 4,14

Griffin v. Maryland, 378 IT. S. 130 (1964) .................. 10

Hamm v. City of Bock H ill,------U. S . ------- , 85 S. Ct.

384 (1964) ............................... ............................. 12,13,14

Hornsby v. Allen, 330 F. 2d 55 (5 Cir. 1964) .............. 10

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 H. S. 267 (1963) .................. 10

Monroe v. Pape, 365 IT. S. 167 (1961) ......................... 10

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. 8. 415 (1963) ...................... 9

Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110 (5 Cir. 1963), re

hearing denied 319 F. 2d 859, cert. den. 375 H. S.

975 (1964) .................................................................... 10

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. 8. 244 (1963) .... 10

Polito v. Molasky, 123 F. 2d 258 (8 Cir. 1941), cert,

den. 315 U. S. 804 (1942) ........................................ 10

Bachel, et al. v. State of Georgia, ------F. 2 d ------- (5

Cir. 1965), No. 21534, decided Mar. 5, 1965 .......8,13,14

Beynolds v. Cochran, 365 U. S. 525 ............................. 14

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) .............. ....... 11

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. 8. 359 (1931) ......... . 12

PAGE

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 (1962) .................. 10

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940) ............... . 12

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963) ....................- 10

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5 Cir. 1961) .... 8, 9

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 (1948) .......... 12

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) .......... ....... 10

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) .................. 10

Constitution:

First Amendment ........................................................... 6

Fourteenth Amendment ...................................—...... -.... 6,11

Fifteenth Amendment ...................................................... 6

Statutes:

28 U. S. C. §1443 .......................................... ................ 1, 5

28 U. S. C. §1443(1) ................................................... 8

28 U. S. C. §1443(2) .......................................... 10

42 U. S. C. §§1971 et seq .............. ............................. . 6

42 U. S. C. §1983 ................... 10

42 U. S. C. §1988 ........ 9

Florida Statutes:

Section 821.04 ........ 11

Section 821.041(1) ................................................... 11,12

Section 821.06 ................... 11

Section 821.07 ......................................................... —2,11

I l l

PAGE

I n t fr i i C o u r t n f Kppmlz

F if t h C ir c u it

No. 21,835

S t u a r t W e c h s l e r , et al.,

Appellants,

—versus—

C o u n t y of G ad sd e n , F lo rid a ,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

TALLAHASSEE DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

Appellants in these consolidated cases are five Negro

and two white persons charged with criminal trespass in

Gadsden County, Florida.

On August 14, 1964, appellants filed verified removal

petitions in the United States District Court for the North

ern District of Florida, Tallahassee Division (the “ District

Court” ). Removal was sought pursuant to 28 U. S. C.

§1443 (R. 5, 25).

At the time of their arrests, appellants were attempting

to acquaint Negro citizens of Gadsden County with their

federal rights to vote, and to encourage them to register

and vote in federal elections (R. 3, 23).

2

In their verified removal petitions, appellants alleged

that on August 7, 1964, they were driving along a road

leading to unenclosed and unposted lands of a farm ex

ceeding 200 acres. Access to the road was not barred by

any enclosure, and there were no “ No Trespassing” notices

posted along the road. Appellants Preston and Green had

relatives living upon said land, whom Preston and Green

had previously visited without challenge or objection.

As appellants stopped their automobile to talk with

Negroes occupying residences adjacent to the road, a

truck (with a rifle visible in the driver’s compartment)

pulled alongside, and its driver asked appellants what

they were doing. Appellants replied that they were work

ing on voter registration. The truck driver told appel

lants that they were trespassing; appellants said they did

not know they were trespassing, and offered to leave im

mediately; the truck driver replied that appellants were

going to be put under arrest and that he was going “to put

the law on” them. Officers of the Sheriff’s office of Gadsden

County then appeared, arrested appellants, and took them

into custody (E. 2-3, 22-23).

No summons, complaint, warrant, or other written proc

ess was ever served on or given to appellants Wechsler,

McVoy, or Preston. Appellant Wechsler asked the Justice

of the Peace Court of Gadsden County for a copy of any

process in the case, but the request was refused (E. 29).

The four juvenile appellants were charged in written

complaints with “ Trespassing”, but the complaints did not

specify any statute (E. 10). A representative of appellants

was told by the Justice of the Peace of Gadsden County

that appellants were charged with violating Section 821.07

of the Florida Statutes (E. 21-22).

3

In their verified and uncontradicted removal petitions,

appellants alleged, inter alia, that their arrests and prose

cutions “have been and are being carried on with the sole

purpose and effect of harassing [appellants] and of pun

ishing them for, and deterring them from, exercising

their constitutionally protected rights of free speech and

assembly to protest the conditions of racial discrimination

which the State of Florida now maintains by statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, usage and practice, and to urge

Negroes, the victims of this discrimination, to register for

voting in federal and state elections, free of racial dis

crimination.” (E. 4-5, 25.)

The removal petitions alleged in detail the denial and

deprivation, in the state courts and by virtue of state legis

lation, of civil rights protected under federal law. Particu

lar allegations are mentioned hereinafter in the Argument.

Notices of the removals and copies of the removal peti

tions were personally served upon the Prosecuting Attor

ney of the Juvenile Court and the Justice of the Peace

Court for Gadsden County.

The Justice of the Peace Court, after acknowledging ser

vice of the notice and removal petition upon him, never

theless purported to try, convict, and sentence appellants

Wechsler, McVoy, and Preston on August 15, 1964 (E.

31-33).

On August 17, 1964, appellants Wechsler and McVoy

petitioned the District Court for writs of habeas corpus,

on the ground that the removals had divested the state

court of jurisdiction. The petitions for writs were granted,

and the Sheriff of Gadsden County was directed to release

said appellants; but at the same time, the District Court,

4

Carswell, J., sua sponte, without notice to any of the appel

lants and without any hearing on their removal petitions,

entered orders remanding the causes of all seven appellants

to the state courts in Gadsden County, citing as authority

Dresner, et al. v. Municipal Judge, City of Tallahassee,

------F. 2 d ------- , decided by this Court on August 5, 1964

(E. 12, 34).

Appellants’ attorneys immediately moved the District

Court for an order staying further proceedings in the state

courts pending the filing of notice of appeal from the orders

of remand. The District Court denied the motion (E. 13,

35), but this Court granted a stay.

Specifications of Error

The District Court erred in :

(1) failing to retain jurisdiction upon the allegations

set forth in the removal petitions;

(2) failing to dismiss or enjoin the prosecutions of ap

pellants without further proceedings;

(3) remanding without a hearing;

(4) concluding that remand was in the interests of jus

tice and sound judicial administration and in accordance

with the authority cited by the District Court.

5

A R G U M E N T

I.

The District Court was required to retain jurisdic

tion upon the allegations set forth in the removal peti

tions.

The District Court, in granting the petitions of appel

lants Wechsler and McVoy for writs of habeas corpus,

acknowledged that their cases had been removed from the

state court in compliance with the federal removal statutes

(R. 32-33). The cases of all seven appellants were re

moved in the same proper manner and upon .substantially

identical allegations.

Jurisdiction of these removed cases vested in the Dis

trict Court not through the court’s discretion, but as a

matter of right of the appellants. The District Court has

no discretion to refuse to entertain jurisdiction over cases

properly removed upon adequate allegations.

The verified removal petitions state removal claims cog

nizable under both subsections (1) and (2) of 28 U. S. C.

§1443 (1958).*

# “ §1443. Civil rights cases

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prosecutions,

commenced in a State court may be removed by the defendant

to the district court of the United States for the district and

division embracing the place where it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot enforce

in the courts of such State a right under any law providing

for the equal civil rights of citizens of the United States, or

of all persons within the jurisdiction thereof;

(2) For any act under color of authority derived from any

law providing for equal rights, or for refusing to do any act

on the ground that it would be inconsistent with such law.”

6

The removal petitions alleged the denial, by state offi

cers in state courts and by virtue of state legislation,

of appellants’ equal civil rights under 42 U. S. C. §§1971

et seq. and the First, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amend

ments.

The removal petitions alleged specific facts respecting

the arrests of appellants for criminal trespass, including

allegations that appellants were, when arrested, seeking

to acquaint Negro citizens with their federal rights to

register and vote. The petitions stated that criminal pro

ceedings charging appellants with such trespass were

pending against appellants in the Juvenile Court and the

Justice of the Peace Court of Gadsden County, Florida.

(R. 1-3, 21-23.)

Appellants then alleged that their arrests and prosecu

tions were for the sole purpose of harassing and punishing

appellants for, and deterring them from, exercising their

protected civil rights (R. 4-5, 25). Specifically, appellants

alleged the following in their removal petitions:

The acts for which appellants are being held to an

swer as offenses, insofar as the offenses charged have

any basis in fact, are acts in the exercise of appel

lants’ rights of freedom of speech, assembly, and peti

tion guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments and 42 U. S. C. §1983 (1958), and of their

privileges and immunities guaranteed by the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and 42 U. S. C.

§§1985 and 1971 (1958) to disseminate information con

cerning the rights of Negroes to register and vote in

federal elections without abridgement by reason of

race, and to urge qualified Negroes to register and vote

(R. 3-4, 24).

7

Conviction of appellants on such charges would pun

ish them for the exercise of rights, privileges, and

immunities secured by the federal Constitution and

laws, and deter appellants and others from the future

exercise of such rights, privileges, and immunities

(R. 4, 24).

Insofar as the offenses charged against appellants

are based on allegations of conduct not protected by

the federal Constitution and laws cited, those allega

tions are groundless in fact; there is no evidence on

which appellants may be convicted consistent with the

due process requirements of the Fourteenth Amend

ment (B. 4, 24).

Section 821.07 of the Florida Statutes is unconstitu

tional on its face, in that it is too vague, indefinite,

and uncertain adequately to apprise appellants before

hand of the nature of the conduct condemned by the

statute, and thus fails to meet the due process require

ments of the Fourteenth Amendment (E. 5, 25).

Said Florida statute as sought to be applied con

demns conduct expressly protected by the First, Four

teenth, and Fifteenth Amendments (R. 6, 26).

“The County of Gadsden, through its prosecutor and

police officers, and under the guise of prosecuting peti

tioners for trespass is in fact, using and abusing its

laws in an attempt to deprive petitioners of the equal

protection of the law and deprive them of their rights

guaranteed to them by the First, Fourteenth, and

Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States.” (R. 5, 25.)

Appellants are unable to enforce their federal rights

in the courts of Florida, particularly in Gadsden

County, because those courts are hostile to appellants

by reason of appellants’ race and advocacy of the end

8

of racial segregation, and because those courts enforce

the policy of racial discrimination in violation of 42

U. S. C. §1981 and the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 6-7,

26-27).

On the allegations in the verified removal petitions,

removal is clearly required under 28 U. S. C. §1443(1).

Rachel, et al. v. State of Georgia,------F. 2 d ------- (5 Cir.

1965), No. 21534, decided March 5, 1965.

In both Rachel and the case at bar, appellants alleged

that they have been denied or cannot in the state courts

enforce their rights under laws providing for equal civil

rights, because of prosecutions in the state courts for tres

pass under state legislation. This Court held in Rachel that

such allegations compel removal. The allegations in the

case at bar are no less adequate and substantial than those

in Rachel, and similarly compel removal.

Among the rights asserted by appellants at bar is the

right to be free of state prosecution designed to interfere

with the rights of Negro citizens to register and vote. Such

a right was upheld by this Court in United States v. Wood,

295 F. 2d 772 (5 Cir. 1961), enjoining the state prosecution

of a field worker engaged in encouraging Negro citizens to

register and vote, even though the field worker was not him

self qualified to register and vote in the county, and even

assuming that he would receive a fair trial in the state

courts and would possibly be acquitted. This Court said:

“ The legislative history of [42 IT. S. C.] section 1971

would indicate that Congress contemplated just such

activity as is here alleged—where the state criminal

processes are used as instruments for the deprivation

of constitutional rights.” 295 F. 2d at 781.

9

Similarly in the case at bar, appellants alleged, with

out contradiction, that they were arrested and were being

prosecuted because of their activity in encouraging voter

registration, and that the state criminal processes were

thus being used as instruments for the deprivation of

constitutional rights.

On the basis of the record in this Court and in view of

the circumstances prevailing in Gadsden County, it is most

unlikely that, if the state prosecutions of appellants are

allowed to proceed, significant further Negro registration

will take place. Negroes who have lived all their lives under

the white supremacy conditions obtaining in Gadsden

County can hardly be expected to register and otherwise

exercise their rights and privileges of citizenship if the only

persons who come to apprise them of those rights and en

courage them to exercise those rights thereby incur arrest

and prosecution in state courts. These harassing prosecu

tions not only intimidate the Negro citizens of Gadsden

County, but also deprive them of the aid and encourage

ment of the only persons who have ventured to apprise

them of their rights.

If these trespass prosecutions of appellants were al

lowed to continue, the civil rights of Negro citizens of

Gadsden County to register and vote would be reduced to

a meaningless nullity. Federal courts have statutory au

thority to shape an appropriate remedy for the vindication

of civil rights. 42 U. S. C. 1988 (1958); Brazier v. Cherry,

293 F. 2d 401 (5 Cir. 1961). The courts accord such vital

rights as those to register and vote the protection neces

sary to their preservation. United States v. Wood, supra

p. 8; see also, e.g., NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963).

10

Appellants also allege requisite jurisdictional facts for

removal under 28 U. S. C. §1443(2), to wit, that appellants

were arrested for exercising their rights to free speech

and other equal rights under the federal Constitution and

laws, that appellants’ arrests were effected for the sole

purpose of furthering racial discrimination, and that ap

pellants cannot enforce their equal civil rights in the state

courts because Florida and its courts by statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, usage and practice support and main

tain a policy of racial discrimination. Taylor v. Louisiana,

370 U. S. 154 (1962); see also Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S.

284 (1963); Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 (1963);

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 (1963); Griffin

v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 130 (1964).

The District Court has the power to receive evidence

and try the jurisdictional facts. Polito v. Molasky, 123 F. 2d

258 (8 Cir. 1941), cert, denied 315 U. S. 804 (1942). See

also Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293, 313 (1963).

Claimed denials of the full enjoyment of equal civil rights

by state officers acting under color of law are cognizable in

the United States District Courts as matters of first impres

sion. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886); Baker v.

Carr, 369 U. S. 186 (1962); Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167

(1961); Hornsby v. Allen, 330 F. 2d 55 (5 Cir. 1964).

The arrests of appellants under the circumstances in

this case also violated their civil rights, contrary to

42 U. S. C. §1983, to freedom from unlawful arrest, freedom

of speech, and freedom of association. Nesmith v. Alford,

318 F. 2d 110, 124 (5 Cir. 1963), rehearing denied 319 F. 2d

859, cert, denied 375 U. S. 975 (1964).

The employment of state judicial power together with

county sheriffs and prosecutors to enforce the racial dis

11

crimination shown here constitutes such application of

state power as to bring to bear the guarantees of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 TJ. S. T

(1948).

No warrants or other process in the state court pro

ceedings were ever served upon or given to the adult ap

pellants ; and the complaints against the juvenile appel

lants charge “ Trespassing” but do not specify any statute.

These circumstances are alone sufficient ground for dis

missal of the proceedings against appellants.

The Justice of the Peace Court of Gadsden County told

a representative of appellants that they were charged with

violating Section 821.07 of the Florida statutes (R. 21-22).

Assuming that such oral communication would be sufficient

to satisfy due process requirements of notice to appellants,

Section 821.07 does not set forth or define the crime of

trespass, but simply provides that the requirement of post

ing notices in conspicuous places around the enclosure1 of

enclosed lands, in order to obtain the benefit of the statutes

prohibiting trespass on enclosed lands, shall not apply to

tracts of land not exceeding 200 acres on which there is a

dwelling house.

In Section 821.04, the crime of trespass is defined as the

willful entry, with the view of trespassing, upon any en

closure of another without prior permission of the owner

or occupant. Section 821.06 provides that such enclo

sure must be conspicuously posted with notices. Section

821.041(1) provides that unauthorized entry “upon any

legally enclosed and legally posted land shall be prima

facie evidence of the intention of such person to commit

an act of trespass . . . .”

12

The combined effect of those statutes is that if a person

enters an enclosed tract of land on which there is a dwell

ing house, but which tract of land is not posted, the person

may be committing trespass if the tract of land is less

than 200 acres, but not if it exceeds 200 acres. Whether

the prima facie evidence rule of Section 821.041(1) would

apply to an unposted tract not exceeding 200 acres, in

view of the explicit reference in Section 821.041(1) to

“ legally posted land”, is not clear. For a statute to re

quire a defendant to determine at his peril either the acre

age of a tract or the applicability of the prima facie

evidence rule is plainly not consistent with due process

requirements of clarity and certainty.

Moreover, the criminal trespass proceedings against ap

pellants in this case penalize actions that were expressive

of claims and of views. Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S.

359 (1931); Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940). The

requirements of statutory clarity are in such cases higher

than in the general case. Winters v. New York, 333 U. S.

507 (1948).

The prosecutions of appellants for violation of the Flor

ida trespass statutes in the circumstances of this case would

not be consistent with the requirements of due process.

Bouie v. Columbia, 378 U. S. 347 (1964); Hamm v. City

of Rock H ill,------U. 8 . ------- , 85 S. Ct. 384 (1964).

13

II.

The prosecutions of appellants should be dismissed

without further proceedings in the District Court, or,

in the alternative, should be enjoined.

The same allegations that established the jurisdictional

facts for removal also require dismissal of the prosecutions

rather than further proceedings in the District Court.

The allegations in the removal petition were verified and

uncontradicted. The District Court acknowledged that the

removals were proper, and that the Justice of the Peace

of Gadsden County nevertheless thereafter purported to

try two of the appellants (R. 32-33). The record is thus

already replete with sworn and uncontroverted statements

of fact, and with recognition by the District Court of facts

and conduct by state officials, proving the unlawful pur

poses of the arrests and prosecutions of appellants. The

present record is more than sufficient to require dismissal

of the prosecutions without further proceedings in the

District Court. Rachel, et al. v. State of Georgia, supra

p. 8, at page 15; Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, supra p. 12.

As alternative relief in their removal petitions, appel

lants requested an injunction against the state court prose

cutions. Such injunction is entirely warranted by the facts

and circumstances. See, e.g., Baines v. City of Danville,

337 F. 2d 579, 589 (4 Cir. 1964), in which the Court said:

“ The Removal Acts, for instance, contain no reference

to injunctions, but the power to enjoin a continuation

of state court proceedings is an obvious corollary of

the power to remove the action from state to federal

jurisdiction.”

14

III.

Appellants are at least entitled to a hearing on the

allegations of their verified removal petitions.

Since the removal petitions alleged facts which, if true,

sustain the removals and require dismissal of the state

court prosecutions, it necessarily follows—and it is the law

—that appellants at the very least are entitled to a hearing

in the District Court to prove their allegations. Rachel,

et al. v. State of Georgia, supra p. 8; Hamm v. City of

Rock Hill, supra p. 12.

In remanding without a hearing, the District Court de

nied appellants their right to invoke federal jurisdiction.

Such a denial without a hearing violates due process of law.

Reynolds v. Cochran, 365 U. S. 525 (1961); Council of Fed

eral Organizations v. Mize, 339 F. 2d 898, 901 (5 Cir. 1964).

The orders of remand by the District Court sua sponte,

without any hearing and without allowing arguments to

explore and clarify the issues for the appellate record,

constitute prejudicial error properly reversible by this

Court.

15

IV.

The authority cited by the District Court does not

support the orders of remand.

Contrary to the District Court’s conclusion, and as dem

onstrated by the facts and authorities cited hereinabove,

the interests of justice and sound judicial administration

plainly compel removal and dismissal of the state court

prosecutions. ,

The District Court, in its orders of remand, cited Dres

ner, et al. v. Municipal Judge, City of Tallahassee, decided

by this Court on 'August 5, 1964. In that ease, the District

Court was directed to modify its order in connection with

applications for habeas corpus. That case has no bearing

on the issues now before this Court.

16

CONCLUSION

The orders of remand should be reversed and the

cases returned to the District Court with directions to

dismiss the prosecutions without further proceedings.

Respectfully submitted,

D onal C. Collimore, Jr.

1293 Post Road

Fairfield, Connecticut

J ohn L ow enthal

521 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10017

H oward W. D ixon

Seybold Building

Miami, Florida 33132

Carl R achlin

38 Park Row

New York, N. Y .

E arl J ohnson

625 West "Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida

Melvin L. W ulf

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y.

J ohn D ue

5 4 0 W. Brevard

Tallahassee, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

17

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that on the 16th day of April, 1965, I

served a copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellants upon

H. T. Reynolds, Juvenile Court, Gadsden County, Quincy,

Florida, and William D. Lines, Prosecuting Attorney,

Gadsden County, Quincy, Florida, by mailing a copy

thereof to each of them at their above respective addresses

via U. S. mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants

19

APPENDIX OF FLORIDA STATUTES

821.04 T respass o n en clo su r e

No person in this state shall willfully, and with the view

of trespassing, enter any enclosure of another or enter

upon any tract of land bounded or entirely surrounded by

sea, gulf, bay, river, or by creeks or lakes, without per

mission of the owner or occupant, authorized to give such

permission, being previously obtained, and every person

so trespassing shall be imprisoned not to exceed ninety days

or fined not exceeding fifty dollars.

821.041 U n a u t h o r ize d e n t r y o n l a n d ; p r im a eacie

EVIDENCE OF TRESPASS

(1) The unauthorized entry by any person into or upon

any legally enclosed and legally posted land shall be prima

facie evidence of the intention of such person to commit

an act of trespass and. of intent to commit any other act

pertaining to said land, the improvements thereto or growth

thereon, committed while within said enclosure.

821.06 L an ds m u s t be posted

The provisions of §§ 821.04 and 821.05 shall not apply to

lands which have not been posted in at least three conspicu

ous places around the enclosure, where it is enclosed by a

fence, or lands which have not been posted in conspicuous

places every eight hundred yards where the same is bounded

or formed by a sea, gulf, bay, river, creeks or lakes, and

when so posted as herein provided, such sea, gulf, bay,

river, creeks or lakes shall be taken and considered as an

enclosure. The parties posting the notices or those present

at the time of posting such notices shall be competent to

2 0

prove the posting. Such notices shall be kept in position

where they can be seen.

821.07 P o stin g c e r t a in en closed l a n d n o t n e ce ssar y

It shall not be necessary to give notice by poster on any

enclosed tract of land not exceeding two hnndred acres

on which there is a dwelling house, in order to obtain the

benefits of the statutes of this state prohibiting trespass

on enclosed lands.

38