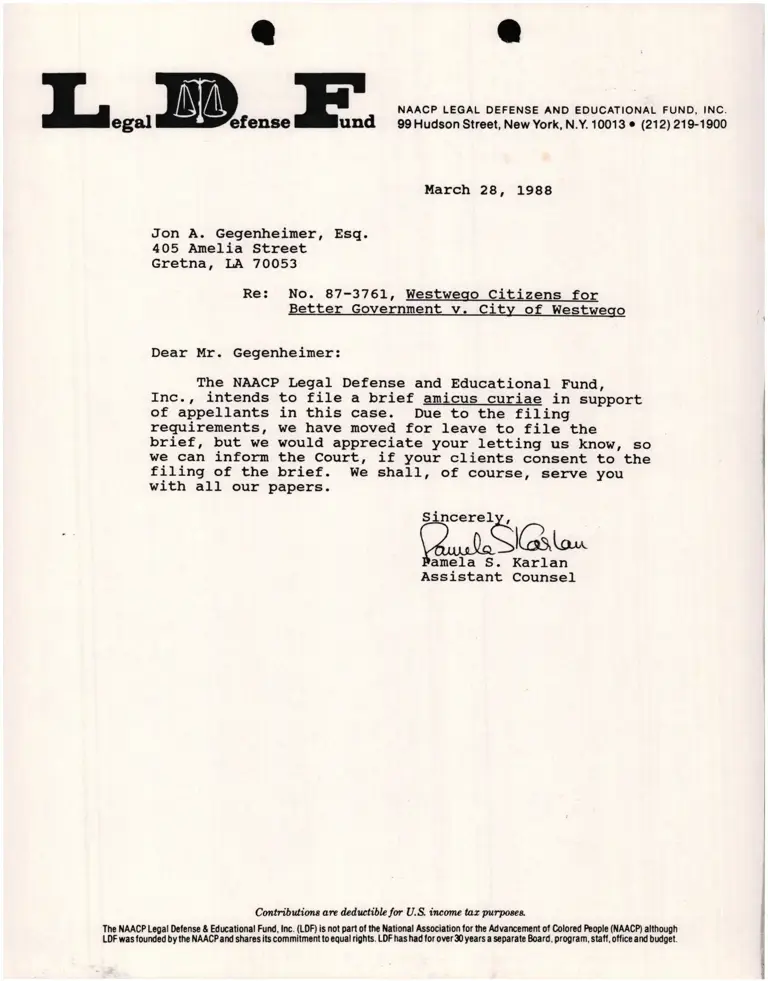

Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Jon A. Gegenheimer, Esq. Re. Westwego Citizens for Better Government v. City of Westwego

Correspondence

March 28, 1988

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Jon A. Gegenheimer, Esq. Re. Westwego Citizens for Better Government v. City of Westwego, 1988. dfefebef-ec92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/45349d6d-27ce-46de-85d3-ca6f5c78ff47/correspondence-from-pamela-karlan-to-jon-a-gegenheimer-esq-re-westwego-citizens-for-better-government-v-city-of-westwego. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Lesa,EerengeE

Itlarch 28, 1988

Jon A. Gegenheimer, Esq.

405 AmeIia Street

Gretna, I"A 70053

Re: No. 87-376t, Westwego Citizens for

Better Government v. City of Westweqo

Dear Mr. Gegenheimer:

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., intends to file a brief amicus curiae in support

of appellants in this case. Due to the filing

requirementsr w€ have moved for leave to file the

brief, but we would appreciate your letting us know, so

we can infom the Court, if your clients consent to the

filing of the brief. We shalI, of course, serve you

with aII our papers.

Conffidione on dedutiblclor U.S hnome tarpu,rpsea,

Thc i{MCP [cgal Oclcnsc & Edcatlonal Fund, lnc. (L0R ls not part ol tttc llational Assoclation lor $c Advancsmcnl ot Colond hople ([{AAGP) althouoh

LDFwaslounded bythc i{MCPand sharcs ltscommitm0ntto rquslrlChts. LDF hashrd lorowrX)ycars a soparate Board. program, stratl, otlics and budget.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

ggHudson street, Newyork, N.y.10013 o (2121219.1900

Sincerelv.

f,*4*SG't"^

Assistant Counsel