United Steelworkers of America (AFL-CIO-CLC) v. Weber Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 28, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Steelworkers of America (AFL-CIO-CLC) v. Weber Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1979. 72d7bae8-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/45985592-fbe8-4264-83ad-ede85bf47e5a/united-steelworkers-of-america-afl-cio-clc-v-weber-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

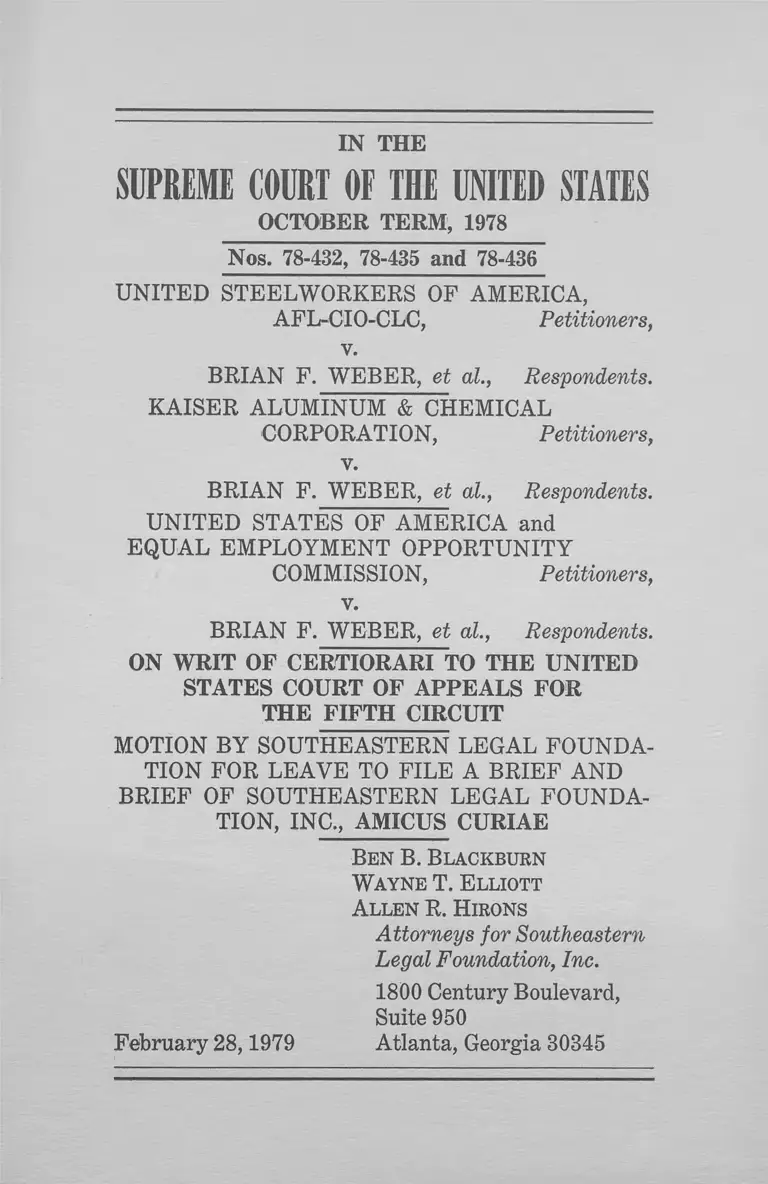

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

Nos. 78-432, 78-435 and 78-436

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIO-CLC, Petitioners,

v.

BRIAN F. W EBER, et at., Respondents.

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL

CORPORATION, Petitioners,

v.

BRIAN F. W EBER, et al., Respondents.

UNITED STATES OF AM ERICA and

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION, Petitioners,

v.

BRIAN F. W EBER, et al., Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MOTION BY SOUTHEASTERN LEGAL FOUNDA

TION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AND

BRIEF OF SOUTHEASTERN LEGAL FOUNDA

TION, IN C., AMICUS CURIAE

B e n B . B l a c k b u r n

W a y n e T . E l l io t t

A l l e n R . H ir o n s

Attorneys for Southeastern

Legal Foundation, Inc.

1800 Century Boulevard,

Suite 950

February 28,1979 Atlanta, Georgia 80345

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

~Nos. 78-432, 78-435 and 78-436

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIO-CLC, Petitioners,

v.

BRIAN F. W EBER, et at., Respondents.

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL

CORPORATION, Petitioners,

v.

BRIAN F. W EBER, et at., Respondents.

UNITED STATES OF AM ERICA and

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION, Petitioners,

v.

BRIAN F. W EBER, et at., Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MOTION BY SOUTHEASTERN LEGAL FOUNDA

TION, INC., AMICUS CURIAE,

FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF

In accordance with this Court’s Rule 42, Southeast

ern Legal Foundation, Inc. ( “ Southeastern” ) moves

this Court for leave to file the attached brief amicus

curiae in the above case. Concurrent with the filing

o f this motion, Southeastern has transmitted to the

Clerk of this Court copies of letters of consent from

petitioners United Steelworkers and Kaiser, and from

respondent Brian F. Weber. The Solicitor General, on

behalf of petitioners United States of America and

IN THE

2

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, has re

fused consent to Southeastern, but has stated that he

will not oppose the filing of this motion. A copy of the

Solicitor General’s letter is also on file with the Clerk.

Southeastern is a Georgia not-for-profit corporation

organized for the purpose of advancing the broad pub

lic interest in adversary proceedings involving signifi

cant issues. Southeastern takes a special interest in

questions of law of a national scope that have a direct

effect on the southeastern region. Southeastern is dedi

cated to economic and social progress through the

equitable administration of law. Although it has no

direct interest in this case as an organization, it repre

sents the members of the public who share Southeast

ern’s dedication to assisting the courts in guaranteeing

that the rights of all persons are properly protected

and balanced in the courts. Southeastern’s representa

tion of the public interest includes the representation

of the several hundred individuals and organizations

which contribute financially to Southeastern.

In addition to the filing of a brief amicus curiae with

the Fifth Circuit in the instant case, Southeastern has

participated as amicus curiae in other employment

discrimination cases involving “ reverse discrimina

tion.” Southeastern filed a brief amicus curiae in Vir

ginia Commonwealth University v. Cramer, No. 76-

1937 (4th Cir. Aug. 15, 1978), and in 1977 urged a

reconsideration of the steel industry consent decrees

o f 1974. That latter effort led to a memorandum opin

ion, by the District Court for the Northern District

of Alabama, which clarified its view of the legality o f

the steel industry consent decrees. United States v.

Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., No. CA 74-P-0339-

3

S (N.D.Ala. Mar. 21,1978) (cited at p. 4 of the United

Steelworkers brief to this Court in this case).

However this Court decides this case, its holding

has the potential o f becoming a signpost to all who

are concerned about the direction of affirmative action

in employment. The Court has the opportunity to ex

plain what will be considered permissible affirmative

action in employment and by whom and when it may

be undertaken or ordered. In view of the potentially

broad impact of this case, the participation of amici

curiae is especially appropriate. Southeastern does not

presume to represent the totality of the public interest.

However, we believe the attached brief presents an im

portant public interest view which will otherwise not

be presented to the Court.*

Respectfully submitted,

B e n B . B l a c k b u r n

W a y n e T . E l l io t t

A l l e n R . H ir o n s

Attorneys for Movant

Southeastern Legal

Foundation, Inc.

1800 Century Boulevard

Suite 950

Atlanta, Georgia 30345

(404) 325-2255

* Last term, this Court permitted Southeastern to appear as

amicus curiae in Duke Power Company v. Carolina Environ

mental Study Group, Inc., 434 U.S. 937 (1978); United States

Nuclear Regulatory Commission v. Carolina Environmental

Study Group, 434 U.S. 937 (1978); and Tennessee Valley

Authority v. Hill, 435 U.S. 902 (1978).

INDEX

Page

INTEREST OF THE SOUTHEASTERN

LEGAL FOUNDATION ................................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............................ 2

ARGUM ENT:

I. EMPLOYMENT QUOTAS SHOULD BE

STRICTLY LIMITED TO REMEDYING

THE EFFECTS OF PAST ILLEGAL

DISCRIMINATION ON IDEN TIFIA

BLE VICTIMS OF THAT DISCRIMI

NATION ........................................................ 3

IL ALL ENTITIES WHICH ADOPT EM

PLOYMENT QUOTAS MUST FIRST

SATISFY THE D IS C R IM IN A T IO N

FINDING AND VICTIM IDENTIFICA

TION TEST .................................................. 6

CONCLUSION 14

11

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases: Page

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ............. 5, 10, 11, 13

Martini v. Republic Steel Corp., 532 F.2d 1079

(6th C ir.), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 927 (1976) . 11

Regents of University of California v. Bakke,__

U.S. _ , 98 S.Ct. 2733 (1978) ........................ 5, 10

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

Inc., No. CA 74-P-0339-S (N.D.Ala. Mar. 21,

1978) ....................................................................... 8

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

Inc., 517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

425 U.S. 944 (1976) ....................................... 8, 12

United Steelworkers Justice Committee v. United

States, 553 F.2d 415 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, de

nied, 435 U.S. 914 (1978) ................................... 11

Weber v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 563

F.2d 216 (1977), rehearing denied, 571 F.2d

337 (5th Cir. 1978) ..................................... passim

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

Nos. 78-432, 78-435 and 78-436

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

IN THE

AFL-CIO-CLC, Petitioners,

V.

BRIAN F. W EBER, et al, Respondents.

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL

CORPORATION, Petitioners,

V.

BRIAN F. W EBER, et al., Respondents.

UNITED STATES OF AM ERICA and

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION, Petitioners,

V.

BRIAN F. W EBER, et al., Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF SOUTHEASTERN LEGAL FOUNDA

TION, INC., AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The interest o f Southeastern Legal Foundation,

Inc. ( “ Southeastern” ) and its reasons for participat

ing in this case are set forth in the attached motion

for leave to file this brief. That statement of interest

is incorporated herein.

2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The use of quotas as a method o f selecting eligible

workers for jobs or other benefits of employment

should be strictly limited to remedying the effects o f

past illegal discrimination against identifiable victims

o f that discrimination. Such remedial quotas should

operate to place a discriminatee into his or her “ right

ful place,” which would have been occupied by the

discriminatee but for previous illegal discrimination.

The use o f quotas conditioned upon findings of past

illegal discrimination and limited to assisting identi

fied victims of that discrimination creates no new vic

tims and thereby eliminates the possibility of “ reverse

discrimination.”

Although a quota does not operate to return an in

jured discriminatee to his or her rightful place as

accurately as does an adjustment o f seniority, it is

an acceptable remedial tool so long as it does not

operate to create new victims of discrimination.

This limited use of quotas guarantees protection for

all workers by producing remedies for past injuries

while not creating new injuries. It is premised upon

specific findings of past discrimination and specific

identification o f victims in each case. To the extent it

requires such findings, this approach may well dis

courage the use of quotas voluntarily or in settlement

agreements.

The practical result o f this approach is that quotas

would be limited to case-by-case agency, legislative,

and judicial determinations which include specific

findings of past illegal discrimination and identifiable

3

victims. Southeastern believes that this limited ap

proach to the use o f quotas is the only approach con

sistent with the Constitution, Title VII of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964, equitable principles, fundamental

fairness and the decisions of this Court.

ARGUMENT

I.

Employment Quotas Should Be Strictly Limited To

Remedying The Effects of Past Illegal Discrimination

On Identifiable Victims of That Discrimination

Southeastern urges this Court to affirm the holding

below insofar as it states (a ) that employers and

unions may not, pursuant to Title VII, voluntarily

adopt racial quotas in the absence of a finding of prior

hiring or promotion discrimination, and (b ) that

preferences assisting individual victims of discrimina

tion are permitted by Title VII. See Weber v. Kaiser

Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 563 F.2d 216, 224-25

(1977), rehearing denied, 571 F.2d 337 (5th Cir. 1978)

( “ Weber” ).

Southeastern believes that such findings are a pre

requisite to the use of quotas as individualized relief.

Boiled down to its bare bones, this case is about

whether one worker may be arbitrarily preferred over

another in employment opportunities when both are

equally situated. As characterized by the petitioners,

this case is about the permissible scope o f Title VII

voluntary compliance. While that is an important fea

ture o f this case, undue attention and deference to

voluntary compliance as a feature of Title V II tends

4

to obscure that this case is about rights. Indeed it is

a certain type o f voluntary compliance— the quota—

which the courts below found to have violated some of

those rights.

Southeastern believes that a quota can be used in a

way that protects the rights of all workers. A quota

which works to remedy the injuries of past employment

discrimination and at the same time respects the rights

o f incumbent non-victim workers serves the goal o f

equal employment opportunity for all. A quota which

grants preferential treatment to some at the expense

of others falls short of that goal o f equality. The quota

adopted by Kaiser and United Steelworkers was a

quota o f the latter type.

A quota which seeks to place an individual worker

in the position he would have held but for illegal dis

crimination against him, need not simultaneously op

erate to discriminate against some other worker. As

the Fifth Circuit said in the decision below:

“ A minority worker who has been kept from

his rightful place by discriminatory hiring

practices may be entitled to preferential

treatment ‘not because he is Black, but be

cause, and only to the extent, he has been

discriminated against.’ ”

Id. at 224. Another way of expressing the Fifth Cir

cuit’s statement is that a quota is only objectionable if

it affects two equally situated individuals and grants

a preference to one of them. If, on the other hand, a

quota is used only to place an identified victim of past

discrimination in his rightful place, the quota dis

criminates against no one. Its operation is strictly

5

remedial. The use of a quota in this latter sense is to

reconstruct what would have happened to the victim

of past discrimination if he had been treated equally

with his peers at the time of the discrimination. While

a quota does not operate to place a victim of past

discrimination in his rightful place as successfully as

an award o f proper seniority, in certain situations it

may be the most efficient remedial tool available.

Southeastern reads the Fifth Circuit’s opinion to

require, as a prerequisite to using quotas, both a find

ing of past discrimination and an identification of

individual victims. See id. at 224-25. The first part of

the test is expressly stated by the Fifth Circuit. The

second part of the test is expressed through the use of

the term “ rightful place.” Both parts of the test are

founded upon decisions o f this Court.

In Regents of University of California v. Bakke,__

U.S. _ , 98 S.Ct. 2733, 2755 (1978) ( “Bakke” ), Mr.

Justice Powell stated that this Court had never ap

proved preferential classifications in the absence of

proven constitutional or statutory violations. In his

discussion of employment discrimination cases, he

noted that racial preferences were premised upon the

need to remedy injuries caused by past discrimination.

Id., 98 S.Ct. at 2754. Thus a finding of past discrimi

nation and a need for remedial relief are prerequisites

to the use of quotas.

This Court has also held that the process of return

ing victims of past discrimination to their “ rightful

places” demands an identification of the actual victims

of the discrimination. International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 371-72

6

(1977) ( “ Teamsters” ) . Teamsters dealt with seniority

rights as opposed to quotas, but the goal of the remedi

al relief was identical to that of the quota in this case—

to put victims in their rightful places. I f the restora

tion o f seniority rights in Teamsters could be achieved

only after evidentiary hearings which identified vic

tims and disclosed the extent of necessary relief, id.

at 376, no less is necessary for the use of quotas.

In sum, the proper test for the use of quotas requires

both a finding of past illegal discrimination and an

identification of victims.

II.

All Entities Which Adopt Employment Quotas Must

First Satisfy The Discrimination-Finding and

Victim Identification Test

Since the purpose of requiring discrimination-find

ing and victim identification is to guarantee that reme

dial quotas protect the rights of all workers, there can

be no variations in the rigors of the test depending on

what entity is applying it. Thus, the demands of the

test apply to courts, government agencies, legislatures

and voluntary parties. No other standard can guaran

tee equal employment opportunity for all.

All judicial decrees, including consent decrees, and

government conciliation agreements, which include

quotas, must be premised upon findings and identifica

tions. I f this Court should hold that the type of quota

test asserted by Southeastern has retrospective appli

cation, existing decrees, settlements and agreements

using quotas may be subject to challenge if they have

7

not been predicated upon adequate findings and iden

tifications.

The Fifth Circuit held that the hiring ratio agreed

to by Kaiser and United Steelworkers could not have

been approved even if it had been judicially imposed.

Weber, supra at 224. The approach of the Fifth Circuit

properly assumes that the outer limits of remedial

relief under Title V II are measured by what the courts

can do in the name o f equity and not by what private

parties may do voluntarily. Even though the court did

not “probe into the distinctions between court-ordered

remedies and permissible remedies agreed upon volun

tarily by private parties,” id., the court did say that

“ there is strong authority to support the position that

courts are not subject to the same restrictions as em

ployers.” Id. at 223.1 * * * * * VII

1 If there is any ambiguity in the Fifth Circuit’s opinion with

respect to the permissible use of quotas, it comes from two

statements found in its discussion of the district court’s de

cision. First, the Fifth Circuit stated that “Title VII does not

prohibit courts from discriminating against individual em

ployees by establishing quota systems where appropriate.”

Weber v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 563 F.2d 216,

223 n.12 (1977), rehearing denied, 571 F.2d 337 (5th Cir.

1978). The court’s choice of words is unfortunate. While Title

VII permits judicially ordered quotas, such quotas are remedi

al and do not discriminate “against individual employees” if

properly premised on findings and identifications. According

to the Fifth Circuit’s discussion in the text following footnote

12, such carefully conditioned quotas are what the court con

sidered appropriate.

Second, by referring to the steel industry consent decrees

and the Fifth Circuit’s 1975 decision upholding them, id. at

223, the opinion leaves the impression that those consent de

crees were legally correct in the adoption of quotas which were

similar to the quota in this case. This impression must be

8

Petitioners argue that the Title VII goal of volun

tary settlement permits private parties to adopt quota

remedies without first having to make “ findings” of

past discrimination. If courts may not grant quota

relief without first finding past illegal discrimination

and identifying victims, then private parties must be

at least, i f not more, restricted in the adoption of quotas.

Even though this case does not involve a consent

decree and this Court does not specifically have to

address consent decree relief, Southeastern believes that

any decision reached by this Court which does not con

sider the full range of possible quota-creating mecha

examined in light of a post appeal statement by the district

judge that he had not determined whether there had been prior

employer discrimination before he signed the consent decrees.

See United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., No.

C.A. 74-P-0339-S, memorandum op. 5, 9 (N.D.Ala. Mar. 21,

1978) {“Allegheny-Ludlum” ) .

It is inexplicable why the Fifth Circut arrived at what

appear to be conflicting decisions in this case and the steel

industry case. See United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Indus

tries, Inc., 517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 425 U.S.

944 (1976). The district judge has stated that the “essence”

of the relevant steel industry consent decree “is a collective

bargaining agreement. . . .” Allegheny-Ludlum, supra at 3.

The quota in this case is also contained in a collective bargain

ing agreement. Likewise in both cases there were no findings

of discrimination before the quotas were adopted. If the only

difference between Weber and the steel industry consent de

crees is that the latter were subscribed by a judge, there is

no meaningful difference. In retrospect, one further differ

ence may be that the Fifth Circuit was not presented with

reverse discrimination claims and arguments in the steel in

dustry consent decree case. Southeastern suggests that the

Fifth Circuit would decide the steel industry consent decree

case differently today.

9

nisms, from voluntary programs to litigated decrees,

will leave everyone— the courts, the government, and

private parties— unclear as to their rights and respon

sibilities with respect to affirmative action relief. If

this Court merely affirms the Fifth Circuit’s decision,

some may conclude that the law prevents voluntary

agreements and judicially imposed quotas in the ab

sence of specific findings and identifications, but that

the law allows consent decrees such as the steel indus

try decrees. Such a result would be illogical and open

the courts to manipulation efforts by private parties.

As Judge Wisdom rightly noted in his dissent below,

employers could use friendly suits to “ circumvent the

holding of Weber.” Id. at 229 n.6 (Wisdom, J. dis

senting) .

Southeastern agrees with Judge Wisdom’s logic that

the holding of the majority in Weber necessarily means

that district courts, “ before accepting . . . consent de

cree [s], will be forced to determine the existence and

extent of past discrimination by the defendants.” Id.

Southeastern believes Judge Wisdom’s dissent correctly

describes the implication of a requirement that quotas

must be remedial only and premised only upon a find

ing of discrimination and an identification of victims.

Logic compels the further conclusion that everyone,

private party, government agency, and court, is bound

by the strict requirements o f the “ finding/identifica-

tion” test.2 Any other result would manifest a disre

2 So long as there is a legally sufficient finding of past illegal

discrimination and identification of victims, the use of quotas

as remedial tools should be permitted. For courts and govern

ment adjudicatory agencies subject to judicial review, the

10

gard for the rights of employees innocent of any wrong

doing. In Teamsters, this Court showed particular con

cern for the legitimate expectations of innocent em

ployees, by requiring the district court to strike a bal

ance “ between the statutory rights of victims and the

contractual rights of non-victim employees.” Team

sters, supra at 376.

Utilizing a quota as a remedial tool only when it

operates to place identified victims of past illegal dis

crimination in their “ rightful places” (or as close as

findings and identifications would be tested, of course, by the

preponderance of the evidence standard. Private parties which

adopt quotas cannot be expected to objectively examine evi

dence detrimental to themslves, and therefore a preponderance

standard may not be an adequate safeguard as to them. Per

haps only findings which are the equivalent of admissions can

justify the adoption of quotas by private parties. Thus, they

may be said to adopt quotas at their own risk. While this ap

proach may discourage voluntary agreements or settlements

including quota provisions, it may be the only approach which

satisfies all the relevant interests and legal standards while

guaranteeing equal opportunity for all.

Acknowledging that the Congress may not be subject to the

same limitations in relief choice as apply to courts, govern

ment agencies and private parties, Southeastern nevertheless

believes that even a congressionally approved quota must be

prefaced by what Mr. Justice Powell has called “detailed legis

lative consideration of the various indicia of previous con

stitutional or statutory violations. . . .” Regents of University

of California v. Bakke, _ U.S_____ 98 S.Ct. 2733, 2755 n.41

(1978) (opinion of Powell, J.). Even if the Congress may be

able to legislate the use of quotas, based on past constitutional

or statutory violations, any entity responding to the legislative

determination should still be required to apply the legislative

determination on a case-by-case approach. In any event, South

eastern does not read the Title VII legislative history so as to

justify the type of quota which has injured Weber.

11

practicable to their rightful places), strikes a proper

balance. Innocent employees have no “ legitimate ex

pectations” subject to injury by the placement of vic

tims of discrimination into their rightful places. But,

unless this Court makes it absolutely clear that quotas

may be used only after a finding of discrimination and

an identification of victims, the rights o f innocent em

ployees will not be adequately protected.

This Court held in Teamsters that in striking the

balance between statutory rights of victims and con

tractual rights of non-victim employees, a district

court must “ state its reasons so that meaningful re

view may be had on appeal.” Id. ( “ contractual rights”

in the Teamsters context means “ seniority” ). In the

instant case it is more accurate to describe the two

interests to be balanced as “ the statutory rights of

victims against the statutory rights of potential vic

tims.” I f reasons for meaningful review were required

in Teamsters, they are even more required here when

statutory rights are balanced against each other.

As a practical matter, employees innocent of any

wrongdoing have had a difficult time obtaining mean

ingful review of voluntary agreements, settlements

and judicial decrees which contain quotas affecting

those employees.3

3 For example, attempts by incumbent non-minority steel

workers to challenge the scope and effects of the steel industry

consent decrees have had no success. In Martini v. Republic

Steel Corp., 532 F.2d 1079 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 429 U.S.

927 (1976), principles of comity prevented the steelworkers

from pursuing relief, and in United States Steelworkers Jus

tice Committee v. United States, 553 F.2d 415 (5th Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 435 U.S. 914 (1978), their intervention challenge

was held untimely.

12

In the typical voluntary collective bargaining agree

ment, such as the one Weber has challenged, the em

ployer and the union agree to take certain affirmative

action. The impetus for such agreements may be sim

ply the good intentions of the parties, or, as in this

case, fear of future litigation and threats from the

federal government. Whatever the reason, innocent

employees such as Weber have no say in the agree

ment process and are not technically parties to it.

Likewise, conciliation settlements, or agreements,

and consent decrees do not generally include parties

with an interest in opposing or limiting the nature

and degree of affirmative action. Rather, the dis

gruntled parties involved, if any, tend to be those who

argue that they have not received enough relief. The

steel industry litigation involving two consent decrees

adopted in 1974 is an excellent example of the process

at work. See United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum In

dustries, Inc., 517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, de

nied, 425 U.S. 944 (1976).

If innocent employees are not made parties from the

very start, they can only defend their interests if they

are quick enough to realize what might happen to them

before it actually does and seek to intervene before

time defeats them.

Realistically, many potential victims of quotas will

not act in time to intervene in existing proceedings,

whether the proceedings are before a government agen

cy or before a court, since they generally fail to react

until the quota implementation has its adverse impact

on them. Their failure to intervene will prevent a

proper representation of their interests unless the de

13

cision makers are constrained by the strict requirement

o f finding past illegal discrimination and identifying

victims before instituting a quota. If the adoption of

quotas is so carefully circumscribed, the dangers of

creating new victims o f quota discrimination will be

greatly reduced. Quotas properly used will be strict

ly remedial and will produce no adverse consequences

for anyone.

The approach to quotas which Southeastern urges

this Court to adopt is, we believe, the only approach

which adequately balances the private settlement theme

of Title VII, Title V II’s specific prohibition against

employment discrimination, the overall purpose of Title

V II to guarantee equal employment opportunities for

all, and the equitable principles enunciated by this

Court in Teamsters, supra at 376. Unlike the peti

tioners, Southeastern does not attach such superior and

overriding importance to voluntary settlement as to

justify virtually any form of voluntarily adopted af

firmative action. However, while quotas must be lim

ited in use and only allowed after certain conditions

are met, they are not foreclosed by the approach sug

gested in this brief.

14

CONCLUSION

Southeastern respectfully urges this Court to affirm

the decision of the Fifth Circuit by holding that quotas

may be used only after a factual finding of past illegal

discrimination and then only to provide relief to identi

fied victims of the illegal discrimination by placing

them, so far as practicable, in their rightful places.

This Court is further urged to apply this standard to

all entities which might adopt or order the use of

quotas.

Respectfully submitted,

B e n B . B l a c k b u r n

W a y n e T . E l l io t t

A l l e n R . H ir o n s

Attorneys for Southeastern Legal

Foundation, Inc.

Southeastern Legal Foundation, Inc.

1800 Century Boulevard

Suite 950

Atlanta, Georgia 30345

(404) 325-2255