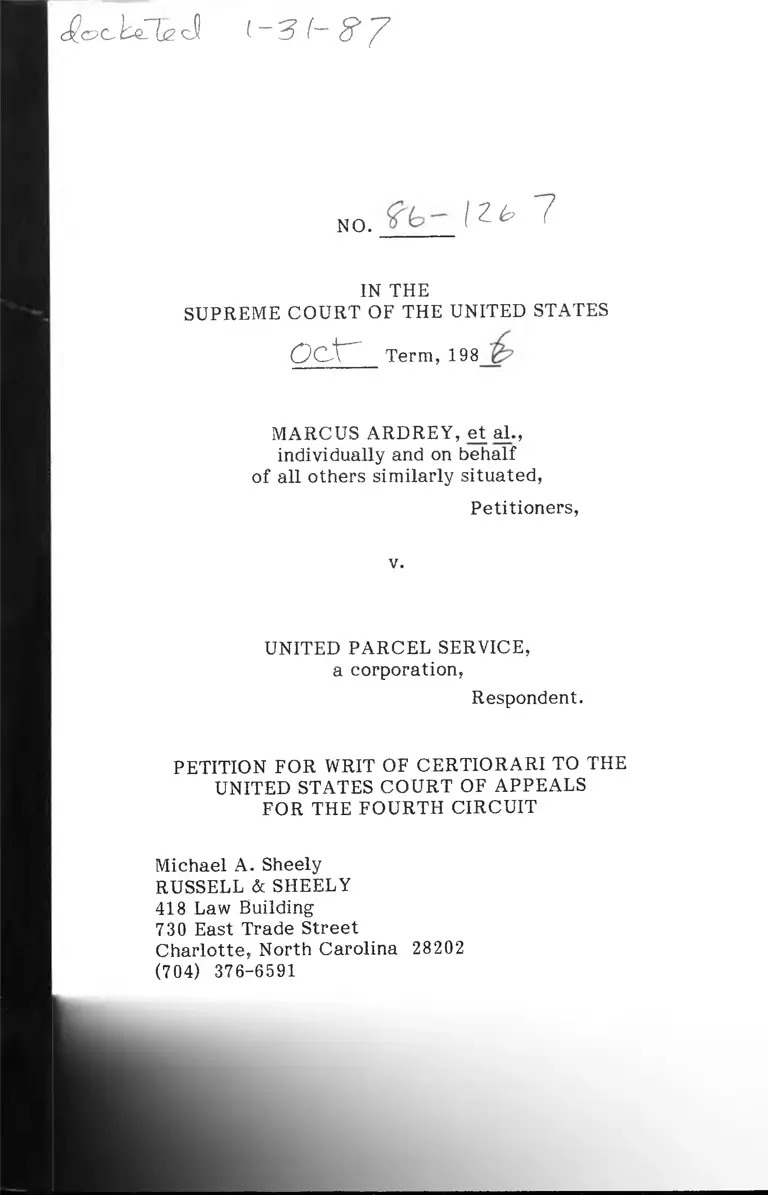

Ardrey v. United Parcel Service Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 30, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ardrey v. United Parcel Service Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1987. 7643aa5d-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/45bae985-71fe-4bcc-a173-895685cab7be/ardrey-v-united-parcel-service-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Copied!

c^c3ckeT7i2 cl ( ~~ 3 ( ~ 8* y

NO. l 2 ^ 7

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

G c JC Term, 198

MARCUS ARDREY, e t alM

individually and on behalf

of all others similarly situated,

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED PARCEL SERVICE,

a corporation,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Michael A. Sheely

RUSSELL & SHEELY

418 Law Building

730 East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

(704) 376-6591

I. QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Are plaintiffs - in a racial discri

mination employment action brought pursuant

to 42 USC §§ 1981 and 2000e et̂ seq - entitled

to pattern and practice discovery in an

effort to prove their individual claims when

said claims are pleaded within the context of

the pattern and practice theory approved by

this Court in International Brotherhood Of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977).

2. Are plaintiffs entitled to discovery

commensurate to the pleaded theory of liabi

lity?

3. Doe3 a requirement by a District

Court that plaintiffs establish their indivi

dual claims before considering any class

discovery requests conflict with this Court's

decision in Elsen v. Carlisle and Jacqueline,

417 U.S. 156 (1974), and the requirements of

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23.

- 1 -

4. When plaintiffs - in a racial

discrimination employment action - have

pleaded their individual claims within the

theories of individual and pattern/ practice

class discrimination, can a District

Court, in reliance upon Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure 26(b)(1) and 26(c): define

the pending action as being limited to the

individual claims of the named plaintiffs;

limit discovery to the individual claims of

the plaintiffs; prohibit adequate pattern and

practice discovery; and require that the

individual claims be established before

requests for class discovery would be con

sidered.

5. Are the Findings of Fact of a

District Court in reference to the individual

claims of the named plaintiffs clearly erro

neous when they: deny the plaintiffs "pat

tern and practice" discovery even though

their individual claims are pleaded within

the context of the pattern and practice

- 2 -

theory; and, require the establishment of

individual claims before considering any

class discovery.

II. LISTING OP ALL PARTIES IN THE CASS

The plaintiffs (Petitioners herein) are

Marcus Ardrey, James Cherry, Bessie Brown,

Louis Funderburk, Horace Jenkins, Joyce

Massey, Jerome Morrow, Sr., Eugene Neal,

Matthew Smith, Jr., Henry Tyson, Sr., Cheryl

Pettigrew, and Carl Watts, individually and

on behalf of all others similarly situated.

The defendant (appellee in the Court of

Appeals; Respondent herein) is United Parcel

Service, a corporation (UPS).

-3-

S)

1

3

4

5

7

7

7

8

17

17

22

25

27

28

34

35

1A

III. TABLE OP CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

LISTING OP ALL PARTIES IN THE

CASE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OP AUTHORITIES

REPORT OP OPINIONS

JURISDICTION

STATUTES AND RULES INVOLVED

STATEMENT OP THE CASE

REASONS WHY THE WRIT SHOULD

BE GRANTED

1. Reason One

2. Reason Two

3. Reason Three

4. Reason Pour

5. Reason Five

6. Reason Six

CONCLUSION

APPENDIX

CERTIFICATE OP SERVICE

-4-

IV. TABLE OP AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE(S)

SUPREME COURT GASES

Burdlne v. Texas Dept of Community 23

" Affairs. 450 U.S. 2~48"(l98l)

East Texas Motor Freight v. 29,30,31

Rodriguez, 431 U.~S. 395 Tl977)

El3en v. Carlisle and Jacqueline, 29,30,33

4T7 U.S. 156 (1974) 34

General Telephone Co. y, Falcone, 30,31

W f U.S. 147' Tl'982)

International Brotherhood of 22

Teamsters v. United States,

$"31 U.S. 324 (1977)

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 22,23,27

411 U.S. 792 (1973) 28

Oppenheimer Fund Inc, v. Sanders, 21,26,27

437 U.S. 340 (1978) 33,34

United States Postal Service Board 16

v. Alkens, 460 U.S. 711 (1983)

OTHER CASES

Burns v. Thlokol Chemical Co., 17,34,35

483 F.2d 300 (5th Clr. 1973)

Diaz v. AT&T,

752 F .2d 1356 (9th Clr. 1985) 17,18,34

Rich v. Martin Marietta, 17,18,19

522" F .2d 333 (10th Clr. 1975) 34,35

-5-

TABLE OP AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE(S)

Trevino v. Celanese. 17,18,25

701 P .2d 397 (5th Cir. 1983) 26,27,34

TREATISES

Wright and Miller, Federal Practice

and Procedure §§ 2008 21

STATUTES

42 USC §§ 1981 8

42 USC § 2000e et se^ 7,8

RULES

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure26(c)

26(b)

23

31,33

8,26,31,33

8,29,30,31,34

V. REPORTS OP OPINIONS

The Order of the District Court is

reported at 615 F.Supp. 1250 (WDNC 1985).

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals is

reported at 798 F.2d 679.(4th Cir. 1986).

VI. JURISDICTION

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals was

decided and entered on August 18, 1986. A

Petition For Rehearing and suggestion for

Rehearing en banc was denied and entered on

November 4, 1986. Jurisdiction of this

Honorable Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1254(1).

V H . STATUTES AND RULES INVOLVED

42 USC § 20Q0e-2(a) provides, in part,

as follows:

(a) Employer Practices

It shall be an unlawful employment prac

tice for an employer -

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to

discharge any individual or otherwise

discriminate against any individual with

respect to his compensation, terms, con

ditions, or privileges of employment

because of such individual's race....

-7-

42 USC § 1981 provides, in part, as

follows:

All persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States shall have the same

right in every State and Territory to

make...contracts...as it enjoyed by

white citizens...

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rule

26(b)(1) provides, in part, as follows:

(b) Unless otherwise limited by order

of the court in accordance with these

rules, the scope of discovery is as

follows:

(1) In General. Parties may obtain

discovery regarding any matter, not pri

vileged, which is relevant to the sub

ject matter involved in the pending

action...

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rules

23 and 26(c)1 (FRCP Rules ____).

V m . STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action, designated as a class

action and brought pursuant to 42 USC §§ 1981

(Civil Rights Act of 1866) and 2Q00e et seq

(Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act),

sought both individual and class/pattern and

1 As provided by Supreme Court Rule 21(f),

the provisions of Rules 23 and 26(c) are set

forth at Appendix, pp. 269A-271A.

- 8 -

practice relief (A 272A-275A .).2 The

District Court had jurisdiction pursuant

to 42 USC § 2000e-5(f) and 28 USC § 1343.

The trial court, subsequent to a non-jury

trial limited to the individual claims of the

plaintiffs, found for UPS on all issues

(A.30A-230A).

The Petitioners had individual race

discrimination claims as follows: failure to

qualify for full-time jobs of preloader or

package car driver (Ardrey, Watts, Cherry);

warnings (Watts, Brown, Cherry, Smith);

suspensions (Watts, Smith); terminations

(Smith, Pettigrew, Massey); training

(Pettigrew); assignment of equipment

(Punderburke, Smith, Neal, Jenkins); removal

of duties (Jenkins); assignment of overtime

(Neal, Brown); denial of days off (Brown);

supervisory harassment (Brown, Neal,

Pettigrew); promotion to supervisor (Neal);

2

References to A. - refer to the

attached Appendix and page numbers.

-9-

and working in a racist atmosphere (all).

In 1 84 of the Complaint, Petitioners

alleged that:

The acts described (in reference to

plaintiffs' individual claims) are mani

festations of a policy and practice

whereby UPS deprives blacks of their

rights to equal employment opportunities

in the following ways ... (parenthesis

added) (A.273A).

The "following ways", (alleging classwide/

pattern and practice discrimination in

disparate treatment, and disparate impact)

are: termination, discipline, suspension,

promotion, and movement from part-time to

full-time positions and a racist atmosphere.3

The plaintiffs notified UPS and the

trial court of their theories of liability

(individuals affected by a general pattern

and practice of discrimination; individual

claims of discrimination).

3

For the full text of f 84 of the

Complaint, refer to A.273A-275A.

- 1 0

UPS has two facilities (Hub;11 General

Office) in Charlotte, North Carolina. Every

plaintiff, except for Pettigrew, worked in

one or more of the hub departments (center,

hub, feeder drivers, maintenance) when their

claims arose. Pettigrew’s claims arose In

the General Office. UPS filed a motion to

limit Initial discovery to the plaintiffs'

Individual claims. Plaintiffs opposed said

motion. The trial court ruled that:

The Court...rules that discovery in this

case shall be limited to the establish

ment of the individual claims of the

present plaintiffs of record. Once 3uch

...actions are established, the Court

will consider requests for further

discovery of a clas3-wide nature. The

plaintiffs have failed to allege or show

how they would be prejudiced by this

bifurcated discovery process...

As a guideline, the parties are advised

that discovery at this time will not be

allowed as to other individuals who are

3--------- -

At the Hub packages are received,

sorted, and placed on either vans for local

delivery (package car drivers) or on tractor

trailers (feeder drivers) for delivery to

other UPS facilities.

- 11 -

not presently plaintiffs of record, or

to statistical Information regarding

groups or classes of employees, unless

3uch discovery would produce Information

relevant to the individual claims

(A.238A-239A) (emphasis added).

In denying plaintiffs’ motion to recon

sider the district court reiterated this

ruling (A.241A-244A).

The plaintiffs' First Set of Interroga

tories , limited to the individual claims of

the plaintiffs, wa3 answered by UPS. The

Second Set sought pattern/practice Informa

tion (A .276A-277A). UPS limited its answers

to: Identity of locations, job titles, de

partments, helrarchy, EEO-1 report job

classification, and lines of progression; and

descriptions of the policies of job perfor

mance review; the bidding/vacancy filling

process; seniority, promotion, transfer,

discipline, and movement from part to full

time positions. UPS, on the grounds of "not

relevant to plaintiffs' Individual claims",

objected to each interrogatory seeking Infor-

- 12 -

mation about: the employment history of

employees; statistics; and, the duties/pay

grades/minimum qualifications for jobs.

(A.276A-277A).

In their first and second Motions To

Compel, plaintiffs sought to compel only as

to the employment practices each was affected

by and in the departments where their indivi

dual claims arose. The trial court, denying

the motions, stated that UPS had provided

sufficient "class discovery" with its answers

to the First Set. (A.245A-262A)

In their Third Set of Interrogatories,

plaintiffs sought information as to the iden

tity of persons who were: disciplined; pro

moted into/qualified for/failed to qualify

for specified jobs;5 considered for promo

tion; and, the Identity of supervisors who

supervised persons holding the specified

5 The specified Jobs were those: jobs

unsuccessfully sought by plantiffs; first

level supervisory jobs; held by Massey and

Pettigrew when each was terminated; and

clerical vacancies for a 6 month period.

-13-

jobs* UPS, in its responses: provided the

annual number of whites and blacks in various

jobs6 as of 12/31 for each year between 1979-

1982; objected to disciplinary information as

irrelevant; limited its responses to the

identity of persons promoted, etc., to those

already made in response to the Pirst Set,

and objected to further responses as being

irrelevant (A.277A-278A). In their Third

Motion To Compel, denied by the trial court,

plaintiffs moved to compel as to the interro

gatories objected to (A.265A-268A).

Throughout this case, the plaintiffs

repeatedly pointed out that their individual

claims were made pursuant to the Teamster

pattern/practice/class discrimination theory

as well as the McDonnell-Douglas/Burdlne

theory.

UPS provided the following limited

information for persons who: either

F-------- -

The jobs were feeder drivers, package

car drivers, loader/unloader, carwash/shif-

ters, part-time clerk, and tracing clerk.

-14-

qualified or failed to qualify for the posi

tions of package car driver and preloader;

were promoted to first level supervisory

positions; were tracing clerk3 and their pro

duction rates; were dispatchers; and, held

certain jobs as of the last day for each year

between 1979-1982. UPS also provided

incomplete disciplinary Information about

individuals whose names were provided by the

plaintiffs. Finally, UPS provided infor

mation as to how vacancies were filled, and

other policies. No pattern and practice

Information was provided for promotions/job

placement for Job3 other than those sought

by the plaintiffs. No pattern and practice

information of any type was provided for

discipline, termination, and assignment of

equipment. Plaintiffs sought information as

to those matters and had individual claims

based on alleged discrimination resulting

-15-

from these practices.7 The Court of Appeals

held that the District Court did not abuse

its discretion by imposing its discovery

limitations.

The opinion below incorrectly stated

that the District Court found that not a

single plaintiff proved a prlma facie case of

discrimination. 798 P .2d 679, 685; (A.29A).

The District Court stated it had reservations

whether some of the plaintiffs failed to

prove a prlma facie case. 615 F.Supp. 1250,

1299, n.3 (A.225A, n.3). Such an observation

itself is irrelevant since after an employer

produces evidence, the issue is whether pre

text and intentional discrimination are pro

ven. Postal Service Board v. Alkens, 460

U.S. 711, 714-717 (1983).

T~

Plaintiffs with these claims were: war

nings (Watts, Brown, Cherry, Smith); suspen

sions (Watts, Smith); terminations (Smith,

Pettigrew, Massey); and, assignment of equip

ment (Smith, Neal, Funderburke).

- 16 -

IX. REASONS WHY THE WRIT SHOULD BE GRANTED

1. The decision of the Court of

Appeals below conflicts with the Circuit

Court decisions of Diaz v. AT&T. 752 F,2d

1356, 1362-1364 (9th Cir. 1985); Trevino v.

Celanese, 701 F.2d 397, 404-408 (5th Cir.

1983); Rich v. Martin-Marietta. 522 F.2d 333,

342-349 (10th Cir. 1975), and Burns v.

Thlokol Chemical Company, 483 F.2d 300 (5th

Cir. 1973).

In each of the foregoing cases, the

Court of Appeals reversed either the District

Court's granting of summary judgment In favor

of the employer (Diaz; Trevino) or trial fin

dings of no discrimination (Rich; Burns).

The major reason for each reversal was

each District Court's failure to consider

relevant pattern and practice Information

which was not present because of

Inappropriate discovery restrictions placed

by the court. In each Instance, the appellate

court ruled that the erroneous limitation on

-17-

discovery deprived each plaintiff of disco

very that was necessary to the pleaded

theory. For example, in Diaz, the plaintiff

had a promotion claim at one facility. He

sought pattern/practice information for the

region in which the facility was located.

The employer objected to the pattern and

practice discovery. The plaintiff filed a

motion to compel. The employer filed a

motion for summary judgment. The District

Court, without deciding the motion to compel,

granted the employer's motion for summary

judgment. The Ninth Circuit held that it was

error for the District Court to consider the

motion without examining the pattern/practice

discovery sought by the plaintiff. A second

example is Rich, supra. The fact situations

ln and Ardrey are very similar. The

plaintiffs filed a pattern and practice case.

The plaintiffs' first set of interrogatories

sought practlce/class/pattern discovery. The

District Court upheld the employer's objec-

- 18 -

tions. The plaintiffs’ second set was

limited to named persons and persons who

worked in the vicinity of the plaintiffs.

The case proceeded to trial on the plain

tiffs' individual claims. The focus of the

trial, for the most part, was limited to the

individual claims. The trial court found no

discrimination. The Tenth Circuit reversed

said findings. The major reason for said

reversal was the Inappropriate limitations

placed on the plaintiffs' discovery. The

Tenth Circuit stated that the trial court

should have allowed factual exploration 3ince

there was no other way to determine the

merits of the plaintiffs' claims.

The conflict arises since the Courts

below upheld limitations on discovery which

were held to be erroneous by the above cited

courts. In this case, the appellate court

below held that denial of pattern/practlce

information (e.g. the District Court denied

any pattern/ practice disciplinary or ter-

-19-

mination information except for a few indivi

duals named by the plaintiffs even though

several plaintiffs had individual discipline/

termination claims pleaded in the context of

the pattern or practice theory) was

appropriate. Discovery in each of the cited

authorities was allowed on a facility or

regional basis while in the case below it was

limited to the Jobs sought by plaintiffs or

individuals named by the plaintiffs. In

the case below, several plaintiffs were

denied any pattern/practlce discovery for the

practice which they had been subjected to.®

It Is crucial that this conflict be

resolved by a review and reversal of the opl-

nlon below. The ruling of the appellate

court below Inappropriately allows a District

Court to unduly restrict pattern and prac

tice discovery even though the Teamster

approved theory Is pleaded by the plain-

15---------

See pp. 15-16 and f.n. 7, supra.

- 2 0 -

tiffs. The opinion below creates a restric

tive standard of discovery^ for plaintiffs

who bring employment discrimination cases

within the Fourth Circuit. This standard is

entirely different than those prevalent in

other Circuits. This standard defeats the

purpose of the employment discrimination sta

tutes and the Teamsters approved pattern and

practice theory by denying an adequate scope

of discovery.

9 Such discovery is unduly restric

ted given that: employment discrimination

cases are based on statutes which reflect a

national policy of primary importance; such

restricted discovery deprives plaintiffs of

any meaningful opportunity to utilize the

pattern and practice theory specifically

approved by this Court in Teamsters; and, the

restrictions conflict with the language of

this Court's unanimous opinion in

Oppenheimer Fund, Inc, v. Sanders, 437 U.S.

340, 351 (1973) that the term "relevancy” in

Rule 26(b)(1) encompasses any matter that

bears on or could lead to other matter that

could bear on any issue that is or may be in

the case. It is important to remember that

attempts to replace the term "relevancy" in

Rule 26(b)(1) with more restrictive language

were rejected. See Wright and Miller,

Federal Practice and Procedure Civil § 2008

(1986 Pocket Part, Vol. 8, §2008, p.20 (text)

and pp.21-22 at f.n. 14.3-14.6). (West

Publishing, 1986).

- 21-

2. The limitations of discovery

affirmed by the court below conflict with

this Court's decision in International

Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977). In Teamsters, this

Court held that a plaintiff is entitled to a

presumption of discrimination in the resolu

tion of his individual claim once he has met

his burden of proving a pattern and practice

of discrimination. Such a pattern is proven

by evidence (e.g. statistics, comparative

treatment, combination thereof) which shows

that discrimination is the rule rather than

the exception. Once a plaintiff is armed

with this rebuttable presumption of discrimi

nation in the resolution of his individual

claim, the burden shifts to the employer to

prove a legitimate non-discriminatory reason

for the challenged action. This theory is

different than the resolution for individual

claim within the format set forth in this

Court's decisions in McDonnell-Douglas Corp.

- 22 -

v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) and Burdlne v

Texas Department of Community Affairs, 451

U.S. 248 (1981). In the MeDonnell-Douglas/

Burdlne format, the plaintiff always retains

the dual burdens of persuasion and proof as

to his individual claim, and the employer

never has to prove anything since he only has

to articulate - not prove - a legitimate, non

discriminatory reason.

The discovery limitations of the court

below conflict with Teamsters since they

deprived the plaintiffs of any meaningful

opportunity to prove their individual claims

within the specifically pleaded context of

the Teamster approved pattern and practice

theory. In effect, the discovery rulings

below: limited the analysis of plaintiffs'

individual claims to the MeDonnell-Douglas/

Burdlne format which imposes the never

shifting burdens of proof and persuasion upon

the plaintiff; and, deprived plaintiffs of

any meaningful attempt to prove their indlvi-

-23-

dual claims within the context of the pat-

tern/practlce theory approved by this Court

In Teamsters and specifically pleaded by the

plaintiffs in their Complaint.

The appellate court below incorrectly

stated that plaintiffs were confusing their

class based claims with their individual

attempts to prove pattern/practice discrimi

nation. 798 P .2d 679, 685; (A.26A).

Plaintiffs are entitled to an adequate

attempt to prove a pattern and practice of

discrimination. If successful, the plain

tiffs will have the presumption of discrimi

nation when it comes time to resolve their

Individual claims. With this presumption,

the employer has the burden of proving no

discrimination.

It Is Important that the conflict be

resolved by a review and reversal of the opl-

-24-

nion below. The appellate opinion below

effectively removes the Teamster pattern and

practice theory as a viable theory to prove

an individual claim. It does so by denying

discovery which is necessary for proving

discrimination as the rule rather than the

exception. At best, the opinion below allows

discovery which may prove "isolated" inci

dents of discrimination. This, of course,

fails to meet the Teamster standard.

3. The Court of Appeal’s ruling

conflicts with the Fifth Circuit Court opi

nion in Trevino, supra. In Trevino, supra,

the Fifth Court stated that a plaintiff was

entitled to discovery commensurate with the

pleaded theory. 701 F.2d 397, ^05. As stated

above, the discovery rulings below deprived

plaintiffs of any meaningful opportunity to

prove their individual claims within the fra

mework of the specifically pleaded Teamsters

approved pattern and practice theory. The

conflict arises because the appellate opinion

-25-

below allows a district court, without

abusing its discretion, to limit discovery in

a manner which deprives plaintiffs of a

meaningful attempt to prove the pleaded

theory while Trevino dictates that discovery

commensurate with the pleaded theory is to be

allowed, and the failure to do so constitutes

an abuse of discretion by the District Court.

The appellate opinion below is in

conflict with this Court’s description

of the meaning of the term "relevancy” as

used in PRCP Rule 26(b)(1). In Oppenhelmer,

supra, this Court, after quoting the text of

Rule 26(b)(1),10 stated that relevant encom

passes "any matter that bears on, or reaso-

I T

The quoted rule in Oppenhelmer was the

1973 version. The 1980 amendments to the

Federal Rules did not change the term

"relevant” In Rule 26(b)(1) even though there

had been suggestions for change. See footnote

10, supra. The text of the first paragraph

of Rule 26(b)(1) is the same now as It was In

1978. The 1980 amendments, which add the

second paragraph to Rule 26(b)(1), do not

reduce the Oppenhelmer definition of rele

vancy. Said paragraph allows a court to pro

tect a party from abusive discovery

requests in a given situation.

-26-

nably could lead to other matter that could

bear on, any issue that is or may be in the

case." 437 U.S. 340, 351. The appellate

opinion below conflicts with Oppenheimer in

that discovery which was relevant to the

individual claims of the plaintiff within the

context of the pleaded theory of a pattern

and practice of discrimination was not

allowed.

It is important that the conflict bet

ween the appellate court opinion below and

the Trevino and Oppenheimer decisions be

resolved for the reasons set forth in the

last paragraph of Section IX(1), and footnote

11, supra.

4. The discovery rulings below conflict

with this Court's language in McDonnell-

Douglas, supra, that statistical data (i.e.

pattern/practice information) was to be con

sidered because it may be reflective of

restrictive or exclusionary practices. 411

-27-

U„S. 792, 806, f.n.19.H The discovery

rulings below deprived the plaintiffs of any

meaningful opportunity to fully utilize this

aspect of the McDonnell-Douglas/Burdine for

mats It did so by depriving them of pattern/

practice information described by this Court

in McDonnell-Douglas as being helpful.

5.--------The opinion of the appellate court

below does not appear to explicitly address

the issue of whether the District Court’s

ruling that the plaintiffs had to establish

their individual claims before any class

discovery would be considered (A.238A-239) is

in conflict with this Court’s language in

IT” --------

Petitioners recognize that in McDonnell-

Douglas this Court 3tated that such "sta- ’

tistics "may’’ be of assistance, and further

more that such determinations, though

helpful, may not, standing alone, be deter

minative of challenged individual decisions.

Petitioners submit however that such a

restriction further underscores their argu

ment concerning the pleaded/proven pattern

and practice theory wherein such general evi

dence can prove a pattern which gives rise to

the presumption of discrimination when ana

lyzing the individual claim.

- 28 -

Bisen v, Carllsle-Jacqueline. 417 U.S. 156,

177-178 (1974). In Elsen, this Court stated

that there is nothing In the history or

language of Rule 23 that gives a court any

authority to conduct a preliminary inquiry

Into the merits of a suit in order to deter

mine class action maintenance.12 The

District Court’s requirement is an inquiry in

12

This Court’s decision in East Texas Motor

Freight v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S7~WT, 91 S.Ct.

1891 (1977) is not applicable. In East

Texas, this Court, concerned with the careful

application of Rule 23 in Title VII cases,

held that the appellate certification of a

class was Inappropriate. The plaintiffs

never moved for class certification and lost

their individual claims In a trial limited to

said claims. In footnote 12 of East Texas,

this Court recognized that an appropriately

certified class would not be destroyed

because the class representatives lost their

Individual claims. In this case plainitffs

failure to prove their individual claims,

as argued above, Is due, at this point, to

the prejudicial and erroneous denial of

necessary pattern/practice discovery. East

Texas Is concerned with adherence to Rule 23;

this matter Is concerned with the appropriate

scope of discovery.

-29-

to the merits in that it requires, before

considering whether the requisites of Rule

23(a) are met, a plaintiff prove his indivi

dual claim.13 The District Court's action

engrafted an unauthorized preliminary

requirement upon those set forth in Rule

23(a). The plain language and history of

Rule 23, neither authorizes any preliminary

inquiry into the merits, nor do they require

a plaintiff to prove his individual claim

before class certification is granted. See

Risen, supra.

The East Texas, supra, and General

Telphone Company v. Falcone. 457 U.S. 147,

102 S.Ct. 2364 (1982) decisions of this Court

do not justify either the requirement or

13

The conflict is further augmented by the

deprivation of necessary discovery. This

deprivation, described above, resulted in

the plaintiffs not being afforded a meaning

ful opportunity to prove their individual

claims within the pleaded theory.

-30

discovery limitations of the courts below,14

In each of these cases, this Court held that

a District Court was to carefully follow Rule

23 in employment discrimination cases.

Neither decision comes remotely close to sup

porting the actions of the Courts below in

denying pattern/practice discovery and

requiring a plaintiff to prove his individual

case before any class discovery will be con

sidered.

The District Court was able to deny the

necessary pattern/practice and impose the

challenged requirement by utilizing the

discretion it has pursuant to PRCP Rule 26(c)

to define ’’pending action” in PRCP Rule

26(b)(1) to be limited to the individual

claims of the named plaintiffs, and removing

T5

The Court of Appeals below justified its

affirmation of the District Court by its

reliance on East Texas and Palcone. 798 F.2d

at 685; (A.26A-27A).

-31-

the claims of class/pattern/practice discri

mination (A.243A). This is an abuse of

discretion, particularly since the plaintiffs

pleaded their individual claims within the

context of the Teamster3 approved practice/

pattern of discrimination. Under the

District Court's approach, a trial judge may

define the theories of liability by defining

the scope of the pending lawsuit. The theory

of liability of any action is defined by its

pleadings. A court is not free to add to or

detract from the scope of the allegations set

forth in the pleadings in such a manner which

removes a theory of liability or defense.

The scope of an action may be reduced or in

creased because: the resolution of one issue

(e.g. statute of limitations) may resolve the

entire matter? and, the presence or absence

of a meritorious claim or defense. Such a

determination is based upon the evidence that

is present in the record. In this case, the

-32-

determination was not based upon record evi

dence. It was determined solely by the

District Court stating "this is in" or "this

is out." Thi3 is an abuse of discretion.

There is nothing present in either the

language or history of Rules 26(b)(1) and

26(c) which allow a Judge to rule that a por

tion of the allegations are not part of the

law suit. Such action simply constitutes an

abuse of discretion.

Finally, the District Court's use of

Rules 26(c) and 26(b)(1) allows a trial court

to define "relevancy" in rule 26(b)(1) in

such a manner so as to defeat the broad

meaning given to relevancy by this Court in

Qppenheimer, supra. It does by removing

Issues clearly present In the pleadings.

This removal is simply accomplished by

defining what Is "pending." This defeats the

broad definition In Qppenheimer which defines

relevancy as "any Issue that is or may be In

the case." 437 U.S. 340, 351.

-33-

It Is important that the conflict bet

ween the opinion below and the above quoted

language of Elsen, Rule 23, and Oppenhelmer

be resolved by a review and reversal of the

opinion below. The actions of the courts

below: are clearly inconsistent with the

purposes of Elsen, Oppenhelmer, and Rule 23;

allow a trial court to impose an additional

requirement on Rule 23; and, allow a trial

court to deny appropriate discovery through

improper use of the Rules of Civil Procedure.

6. For each of the five foregoing

reasons, the findings of the District Court

below are clearly erroneous. These findings

- like the Diaz and Trevino summary judgments

and the Burns and Rich trial findings - were

based upon Incomplete evidence, and a failure

to consider pattern and practice evidence.

The failure to consider the pattern and prac

tice evidence was due to the inappropriate

discovery limitations. The process below is

the same as what happened In Diaz, Trevino,

-34-

Rich, and Burns except that In those cases

the appellate courts corrected the error,

while In this case, the appellate court below

compounded the error by joining in and

affirming its commission.

For each of the reasons set forth above,

this Court should grant the writ.

X. CONCLUSION

This the day of. 1987.

RUSSELL & SHEELY

MICHAEL A. SHEELY

4l8 Law Building

730 East Trade Street

Charlotte, NC 28202

(704) 376-6591

cr

Attorney for Petitioners

-35-

XI. APPENDIX

TABLE OP CONTENTS

PAGE(S)

Opinion of the Court of Appeals 2A-29A

Order of the District Court 30A-230A

(8-19-85)

Order of the Court of Appeals 231A-232A

Denying Petition For Rehearing

Order of the District Court(9-6-85) 233A-234A

Pinal Judgment of the District Court 235A

(9-6-85)

Discovery Procedure Order of the 236A-240A

District Court (10-26-82)

Discovery Procedure Order of the

District Court (11-22-82)

Discovery Order of the District

Court (4-1-83)

Discovery Order of the District

Court (7-15-83)

Discovery Order of the District

Court (4-19-84)

Text of FRCP Rules 23 and 26(c)

Complaint

Description of Interrogatories

/Responses

241A-244A

245A-262A

263A-264A

265A-268A

-1A-

269A-271A

272A-275A

276A-278A

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-2239

Marcus Ardrey,

James Cherry,

Bessie Easterling Brown,

Louis Funderburk,

Horace Jenkins,

Joyce Massey,

Jerome Morrow, Sr.,

Eugene Neal,

Matthew Smith, Jr.,

Henry Tyson, Sr.,

Cheryl Pettigrew,

Carl Watts, individually and

on behalf of all others similarly

situated,

Appellants,

versus

United Parcel Service,

a corporation,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Western District of North

Carolina, at Charlotte. Robert D. Potter,

Chief Judge. (C/A 82-323).

Argued: May 6, 1986 Decided: August 18, 1986

Before MURNAGHAN and WILKINSON, Circuit

Judges, and HAYNSWORTH, Senior Circuit

Judge.

-2A- •

Michael A. Sheely (Russell, Sheely &

Hollingsworth on brief) for Appellants;

William W. Sturges (Weinstein, Sturges,

Odom, Groves, Bigger, Jonas & Campbell,

P. A. on brief) for Appellee.

MURNAGHAN, Circuit Judge:

I

Numerous plaintiffs employed by the

West Carolina district of United Parcel

Service ("UPS"), which encompasses the

western part of North Carolina and all of

South Carolina and is centered in Charlotte,

North Carolina, by complaint dated May 20,

1982 moved for class certification, filed

individual discrimination claims pursuant

to 29 U.S.C. Section 621, Age Discrimination

in Employment Act ("ADEA"), Section 1981 of

the 1866 Civil Rights Act, and Title VII of

the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The plaintiffs

alleged class discrimination against them

as a race. Specifically, they alleged that

UPS had engaged in a "policy and practice

whereby UPS deprives blacks of their rights

to equal employment opportunities."

- 3 A - .

On

information and belief plaintiffs alleged

four ways in which UPS's policy and practice

operated, namely through 1) termination,

discipline and suspension; 2) promotion;

3) transfer of employees from part-time to

full-time positions; and 4) racist

atmosphere.1

1 The various individual plaintiffs

alleged discriminatory acts:

(1) Marcus Ardrey— alleged he was

prevented from moving from a part-time

to a full-time position because of his

race; (2) James Cherry— alleged he

was denied a full-time position (he

was employed half-time) and received

unjustified warnings because of his

race; (3) Bessie Easterling [Brown]—

was denied days off, subjected to

unwanted physical contact by junior

white employees and subjected to

harassment by white dispatchers because

of her race; (4) Louis Funderburk— was

treated differentially as a UPS driver

because of his race; (6) Joyce Massey—

was discharged because of her race;

(7) Jerome Morrow, Sr.— was denied

promotion and required to work in a

racist atmosphere because of his race;

(8) Eugene Neal— was harassed and

denied promotion because of his race;

(9) Matthew Smith, Jr.— was given poor

work runs, poorer equipment, and

warning letters for infractions he did

not commit because of his race;

(Continued)

- 4 A -

The instant appeal concerns the

district court's handling of the discovery

phase of the case. In their first set of

interrogatories the named plaintiffs

requested information related to their

individual claims, as alleged in their

complaint. UPS answered these interroga

tories and provided information not only

about the specific UPS employee in question,

but also about others who had been promoted,

transferred or qualified for various

positions. ̂ At the same time as they served

their first set, plaintiffs served a second

(10) Henry Tyson, Jr.— was subject to

working in a racist atmosphere; (11)

Carl Watts— was disciplined because of

his race; (12) another plaintiff, who

was allowed to intervene, Cheryl

Pettigrew, alleged racial discrimination

in her treatment by her supervisor,

training and subsequent discharge.

2 For example, for plaintiff Marcus

Ardrey, UPS provided the "name, race,

prior experience, prior education,

qualifications, date of hire, date

became full-time of each person who

obtained a full-time package car

driving position between January 1,

1980 and December 31, 1982"; for

(Continued)

- 5 A -

set of interrogatories seeking "class

pattern/practice information" about the

Charlotte, North Carolina headquarters of

the UPS West Carolina region. Plaintiffs

sought information about the employment

history of all employees who had worked in

the Charlotte headquarters since January 1,

1979, about all vacancies which occurred in

all job titles since January 1, 1979, the

name and race of each person who filled the

vacancies and the date the facancies

occurred and were filled, about transfer and

promotion system policies, and the names,

race and job titles of persons with

knowledge of various personnel practices,

including hiring, promotion and transfer and

the methods by which employees were disci

plined and the ways employees were

plaintiff James Cherry, UPS provided

similar information on those part-time

bargaining unit employees who were

promoted to and qualified for full time

package car driving positions.

-6A-

transferred from part-time to full-time

positions. Plaintiffs also requested

information about the number of whites and

blacks who were promoted, transferred,

employed, or qualified for full-time jobs.

In response to the second set of

interrogatories, UPS filed many answers and

documents, but objected to interrogatories

seeking information about the employment

history of employees, statistics, and

duties, pay grades and minimum qualifica

tions for jobs that were not related to the

claims of individual plaintiffs.3

For example, UPS refused to provide

the number of whites and blacks in

various broad categories of employment

for 1979 to date because "such data

would be irrelevant to plaintiff

Pettigrew's claim" and objected "to

providing information on the job duties

and pay rates of management, supervisory

and clerical jobs that are not involved

in any of plaintiffs' individual claims."

- 7 A -

Before these two sets of interrogato

ries were served on defendant, UPS had

moved for (and the district court had

granted on October 22, 1982) a limitation

on initial discovery which restricted

plaintiffs to discovery about information

related to their individual claims as

opposed to information regarding their

class action. In granting such a limitation,

the court stated that "[ojnce such

individual action or actions are established,

the Court will consider requests for

further discovery of a class-wide nature.

The plaintiffs have failed to allege or show

how they would be prejudiced by this

bifurcated discovery process." The court

noted it agreed with counsel for UPS that

plaintiffs would be required "to establish

viable individual actions" before class

discovery would be allowed. The court

relied on East Texas Motor Freight System,

Inc, v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 395, 403 (1977)

- 8 A -

and General Telephone Co. of Southwest v.

Falcon, 457 U.S. 147 (1982) in so deciding.^

Subsequent to UPS's refusal to answer

various of their second set of interrogato

ries, plaintiffs filed motions to compel.

On April 1, 1983, the court denied these

motions on the ground that the information

requested (e.g,, name and race of all

persons qualified to be package drivers,

statistical information about promotions to

other jobs, movement from part-time to other

full-time jobs, which were not sought by-

plaintiffs) , was "hardly germane to [the

individual plaintiffs'] claims in view of

the statistical data already furnished in

respect to the specific jobs they sought."

The district court established a

guideline "that discovery at this time

will not be allowed as to other indi

viduals who are not presently plaintiffs

of record, or to statistical information

regarding groups or classes of employ

ees, unless such discovery would produce

information relevant to the individual claims."

-9A-

(Emphasis provided.) The court reasoned

that because UPS had already provided

information about individuals and their

claims pursuant to the first set of

interrogatories, UPS was not required to

produce the "comprehensive employment

history" requested in the second set which

was not relevant to individual claims. The

court also noted such information would be

inordinately burdensome for defendant to

prepare.

Plaintiffs served defendant with a

third set of interrogatories on April 6,

1983. UPS objected to providing discipli

nary information about the number of blacks

and whites who had received warnings, or who

were suspended or disciplined, and limited

its responses to information about individual

employees which it had already provided.5 A

5 Defendant again noted that it

objected "to furnishing the requested

information for all employees in the

(Continued)

- 1 0 A -

third motion to compel ensued which the

district court denied. The plaintiffs

moved for reconsideration, on the grounds

of our opinions in Lilly v. Harris-Teeter,

720 F.2d 326 (4th Cir. 1983), cert, denied,

466 U.S. 951 (1984), and Knighton v . The

Laurens School District, 721 F .2d 976 (4th

Cir. 1983). The district court subsequently

modified its order and compelled UPS to

provide the names of those in the Charlotte

office who made various employment decisions

pursuant to our decision in Lilly, 720 F .2d

at 338, which held that where the "same . .

managerial personnel were responsible for

decision making" in several allegedly

discriminatory contexts, a case of discrim

inatory intent might be made out. In other

regards, the district court reaffirmed its

earlier order.

requested job classifications . . .

since the information would not be

relevant to the individual claims of

any plaintiff and would be unduly

burdensome to obtain.

- 1 1 A -

The case was heard by the court without

a jury and trial was limited to plaintiffs'

individual claims. The district court

found for UPS on all issues and dismissed

plaintiffs' claims. The court found no

evidence that individual black plaintiffs

had been discriminated against in regard to

warnings, suspensions, terminations,

promotions, or moves into full-time jobs,

or had been treated in any way different

from whites. After lengthy findings of

fact, the court examined the relevant law as

set forth in McDonnell Douglas Corp, v.

Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) and Texas

Department of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248 (1981), which establishes a

shifting burden for Title VII discrimination

suits. The court examined the specific

legal elements of the individual plaintiffs'

claims and found that "Defendant offered

substantial evidence that the alleged

adverse employment actions concerning the

- 1 2 A -

Plaintiffs were £>ased upon legitimate,

nondiscriminatory business considerations."

In addition, the court found that plaintiffs

had not shown that the reasons offered by

defendant to explain its employment actions

were pretextual. The district court

concluded that defendants had not discrim

inated against plaintiffs on account of race

or sex in violation of Title VII or Section

1981. Because it only reached plaintiffs'

individual allegations of discriminatory

treatment, the court did not discuss

plaintiffs' class-based pattern/practice

claim, i.e., that UPS had a "policy and

practice whereby [it] deprives blacks of

their rights to equal employment oppor

tunities ."

The district court retained jurisdiction

of the case as a possible class action for

fourteen days in order to allow preparation

by plaintiffs of a class certification

motion. Because the parties did not submit

- 1 3 A -

a schedule for class certification, the

court dismissed that portion of plaintiffs'

case and entered judgment for the defendants

on September 6, 1985.

II

On appeal, plaintiffs contend that the

district court's limitation of discovery to

their individual discrimination claims

thwarted their efforts to establish that UPS

engaged in a "pattern and practice" of

discrimination against blacks. Because

"class-wide" discovery was not allowed,

plaintiffs were unable to establish pattern

and practice discrimination according to

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324,

331, 335-36 (1977) . Teamsters discrimination

differs from a McDonnell Douglas/Burdine

Title VII claim in that it allows a plaintiff,

by preponderance of the evidence, to show

that an employer had "a pattern or practice

of employment discrimination" or that

"disparate treatment" of black employees was

-14A-

the "company's standard operating proce-

dure--the regular rather than the unusual,

practice." Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 436. For

a Teamsters claim, the plaintiff, after

establishing a prima facie case of discrim

ination, must then, by the preponderance of

the evidence, establish that discrimination

was the "standard operating procedure" of

the defendant. Most often, the plaintiff

establishes such a case by statistics,

bolstered by other testimony. 431 U.S. at

336, 339.

Plaintiffs' argument is that they were

prevented from obtaining the class-wide

discovery related to other black and white

employees of UPS which would allow them to

establish through statistics that UPS had a

"pattern or practice" or standard operating

procedure of discrimination against blacks.

Ill

We begin with the familiar principles

that a district court has wide latitude in

- 1 5 A -

controlling discovery and that its rulings

will not be overturned absent a showing of

clear abuse of discretion. Rabb v. Amatex

Corp., 769 F .2d 996, 999 (4th Dir. 1985);

Belcher v. Bassett Furniture Industries,

Inc., 588 F .2d 904, 907 (4th Cir. 1978);

Ellis v. Brotherhood of Railway, Airline and

Steamship Clerks, 685 F.2d 1065, 1071 (9th

Cir. 1982), aff'd in part and rev'd in part,

466 U.S. 435 (1984). The latitude given the

district court extends as well to the manner

in which it orders the course and scope of

discovery. Eggleston v. Chicago Journeymen

Plumbers Etc., 657 F.2d 890, 902 (7th Cir.

1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 1017 (1982) ;

Sanders v. Shell Oil Co., 678 F.2d 614, 618

(5th Cir. 1982) . Although it is "unusual to

find an abuse of discretion in discovery

matters," Sanders, 678 F.2d at 618, a

district court may not, through discovery

restrictions, prevent a plaintiff from

pursuing a theory or entire cause of action.

- 1 6 A -

Diaz v. American Tel. & Tel., 752 F.2d 1356,

1363 (9th Cir. 1985); Trevino v. Celanese

Corp., 701 F .2d 397 (5th Cir. 1983).

To put plaintiffs' claims that they

were improperly denied discovery into

perspective, it is necessary to examine the

two broad theories of Title VII cases—

disparate treatment and disparate impact.

At the outset, it is important to note that

the two theories are not applied "with

wooden inflexibility and in unvarying

accordance with the details of their

original formulations, nor in mutually

exclusive fashion." Lewis v. Bloomsburg

Mills, Inc., 773 F.2d 561, 572 (4th Cir.

1985) . Nonetheless, the two theories are

also not "simply interchangeable"— they

indeed do "reflect critical substantive

differences as to discrimination in the

context of Title VII."

The first theory advanced by plaintiffs

was that they were discriminated against by

- 1 7 A -

their employer because of their race, i.e.,

they were subject to "disparate treatment."

Those claims require a determination of

whether the individual plaintiffs were

victims of racial discrimination. In order

to show this, the plaintiffs at all times

have the "ultimate burden of persuading the

court that [they were] the victim[s] of

intentional discrimination." Burdine, 450

U.S. at 256. Whether plaintiffs have in

fact shouldered the burden is subject to the

"analytical framework" of McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green, supra, which is "'intended

progressively to sharpen the inquiry into

the elusive factual question of intentional

discrimination' in private, nonclass Title

VII cases," Coates v. Johnson & Johnson, 756

F.2d 524, 541 (7th Cir. 1985), citing

Burdine, 450 U.S. at 255 n.8. The district

court here applied the schema of Burdine and

McDonnell Douglas and plaintiffs make no

objection to the district court's finding

-18A-

that they did not surmount the hurdel of

showing that the legitimate, nondiscrimina-

tory reason [s]" for UPS's treatment of the

individual plaintiffs were pretextual.

McDonnell Douglas, 411 U.S. at 802; Burdine,

450 U.S. at 254.

A second inquiry is necessary where

plaintiffs, as here, advance a second

theory--a claim that they were subject to

disparate treatment in such a way as to make

them proper representatives of a class

subject to such treatment. The plaintiffs

(if proper class representatives) must

establish individual claims factually

related to the alleged class claims, since a

class-based disparate treatment suit proceeds

on the theory that a company discriminates

against its black employees by treating them

differently than its white employees. In

order to establish a disparate treatment

claim, otherwise known as a "pattern and

practice case," plaintiffs must '"prove more

- 1 9 A -

than the mere occurrence of isolated or

"accidental" or sporadic discriminatory

acts. [They need] to establish by a

preponderance of the evidence that racial

discrimination was the company's standard

operating procedure— the regular rather than

the unusual practice.'" Teamsters, 431 U.S.

at 336, quoted in Pouncy v. Prudential Ins.

Co. of America, 668 F.2d 795, 802 (5th Cir.

1982). Statistical evidence may be used in

a disparate treatment case to show "both

motive and a pattern or practice of racial

discrimination. In a proper case, [the

court] may infer racial discrimination if

gross statistical disparities in the

composition of an employer's work force can

be shown." Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 335 n.15,

quoted in Pouncy, 668 F.2d at 802. Once

plaintiffs have established that unlawful

discrimination has been the company's

standard operating procedure by way of

statistical evidence, the burden shifts to

- 2 Q A -

defendants to articulate a reason why such

proof is "inaccurate" or "insignificant" or

to show that they had a nondiscriminatory

reason for the "apparently discriminatory

result." Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 360 n .46;

Coates v. Johnson & Johnson, 756 F.2d at 532.

In summary, the "liability portion of

a . . . class disparate treatment case is

essentially comparable to the framework

outlined in McDonnell Douglas-Burdine for

individual disparate treatment actions," but

[t]he focus in a class action is

"on a pattern of discriminatory

decision-making," of which specific

allegations of alleged discrimina

tion may be a part, although not

always controlling if the number

of such instances is not signifi

cant. The class action "may fail

even though discrimination against

one or two individuals have been

proved." The pattern or practice

claim may also fail'— despite any

statistical evidence offered by

plaintiffs— if the defendant

articulates a nondiscriminatory,

nonpretextual reason for every

discharge. On the other hand,

the class claim does not fail

just because the district court

finds that the company has satis

factorily explained the discharges

of the named class representatives

- 2 1 A -

and any other testifying employees.

Since strong statistical evidence,

without anecdotal evidence, may in

some cases form a prima facie case,

a defendant's successful rebuttal

of each alleged instance of dis

crimination weakens, but does not

defeat, a plaintiff's class claim.

Neither statistical nor anecdotal

evidence is automatically entitled

to reverence to the exclusion of

the other.

Coates v. Johnson & Johnson, 756 F.2d at

532-33 (citations ommitted).

The scope of discovery in Title VII

cases is geared to allowing plaintiffs to

proceed under either a disparate treatment

or pattern or practice theory or both.

Generally, undue restrictions of discovery

in Title VII cases are "especially frowned

upon." Trevino, supra, 701 F.2d at 405.

The restrictions placed on such discovery

are dictated "only by relevance and burden

someness ." Rich v. Martin Marietta

Corporation, 522 F.2d 333, 343 (10th Cir.

1975) .

In addition, "statistical evidence is

unquestionably relevant in a Title VII

-22A-

disparate treatment case." Diaz, supra, 752

F„2d at 1362. Such evidence may help

establish a prima facie case and is often

crucial for the plaintiff’s attempt to

establish an inference of discrimination.

Id. Such evidence may also aid the plain

tiff in showing that a "defendant's articu

lated nondiscriminatory reason for the

employment decision in question is pretext-

ual." Id. at 1363. In a pattern and

practice case, "[s]tatistical data is

relevant because it can be used to establish

a general discriminatory practice in an

employer's hiring or promotion practices.

Such a discriminatory pattern is probative

of motive and can therefore create an

inference of discriminatory intent with

respect to the individual employment decision

at issue. In some cases, statistical

evidence alone may be sufficient to establish

a prima facie case." Id.

The question here presented is whether

- 2 3 A -

the restrictions placed on discovery by the

individual claimants prevented them from

gathering evidence to show that there was

such a "general discriminatory practice" on

the part of UPS. Plaintiffs claim they were

prevented from getting discovery of a

"class-wide nature," i .e ., discovery relat

ing to their proposed class action. They

were restricted to discovery on their

individual claims and were not allowed to

get discovery "regarding groups or classes

of employees, unless such discovery would

produce information relevant to the

individual claims."

However, the district court did allow

discovery as to information regarding others

similarly situated to the individual

plaintiffs. For example, UPS provided the

name, race, prior job, hire date and date the

individual became a driver for thirteen

individuals who were part-time bargaining

employees promoted to full-time package car

24A-

driving positions from January 1, 1980 until

December 31, 1981, in regard to Marcus

Ardrey's claim; for James Cherry, UPS

provided similar information as to the

twenty-five persons who were part-time

employees who were promoted to full-time

package car drivers from January 1, 1978

until December 31, 1979 and for twenty-four

who failed to qualify as package car drivers

in the same period; for plaintiff Joyce Y.

Massey, UPS provided similar information on

those promoted to supervisory jobs since

January 1, 1979.

Conversely, what UPS refused to provide

was information about promotion to other

positions, positions which plaintiffs did

not seek, or concerning the employment

histories of employees who held jobs which

were not relevant to individual claims. The

reason articulated by the district court for

refusal to grant such discovery was that it

would be burdensome. We are satisfied that

- 2 5 A -

the district court did not exceed its dis

cretion in so restricting discovery.

Plaintiffs' argument that the restrictions

foreclosed their opportunity to develop a

pattern and practice case is without merit.

The discovery allowed as to their individual

claims was sufficient to develop evidence,

statistical and otherwise, relating to

whether discrimination was the "standard

operating procedure" of UPS in regard to

their positions, or concerning promotions,

transfers, suspensions or discipline,

related to their individual claims.

Plaintiffs confuse their "class-based"

claims— as potential representatives of a

class of UPS employees— with their individual

attempts to show a discriminatory pattern and

practice by UPS. The district court has the

responsibility of managing complex Title VII

litigation under guidelines established by

the Supreme Court. In East Texas Motor

Freight v. Rodriguez, supra, the Court has

- 2 6 A -

held that district courts must pay close

attention to certification of class

representatives in a Title VII suit. In

General Telephone Co. of Southwest v.

Falcon, supra, the Court rejected the Fifth

Circuit's "across the board" rule which

permitted a class action representative to

represent, on the basis of his or her

discrimination claim, a class of persons who

have no claim in common other than an

allegation that a defendant company has a

policy of discrimination. Falcon, 457 U.S.

at 157. A proper class representative must

"bridge the gap" between his individual

claim and the allegation that the defendant

has a general policy of discrimination

against others of his or her race. The

prospective representative must offer proof

of

much more than the validity of his

own claim. Even though evidence

that he was passed over for promo

tion when several less deserving

whites were advanced may support

the conclusion that repondent was

- 2 7 A -

denied the promotion because of

his [race], such evidence would

not necessarily justify the

additional inferences (1) that

this discriminatory treatment is

typical of petitioner's promotion

practices, (2) that petitioner's

promotion practices are motivated

by a policy of ethnic discrimina

tion . . ., or (3) that this

policy of ethnic discrimination

is reflected in petitioner's

other employment practices. . . .

Falcon, 457 U.S. at 158. A district court

errs if it fails "to evaluate carefully the

legitimacy of the named plaintiff's plea

that he is a proper class representative

under Rule 23(a)." Id. at 160. See also

jjiHy v« Harris-Teeter Supermarket, supra,

720 F.2d at 333; Holsey v. Armour & Co., 743

F.2d 199, 216 (4th Cir. 1984), cert. denied,

___ U.S. ___, 105 S.Ct. 1395 (1985).

The district court here correctly

following the dictate of Falcon to evaluate

carefully the claims of the individual

plaintiffs in a Title VII suit. We are not

in a position to second-guess the district

court's determination of such matters, given

- 2 8 A -

the complext task of managing the multi

farious questions which arise in such liti

gation. While we do not hold that the

procedure followed by the district court in

allowing individual discovery, while delay

ing class-wide discovery, would invariably

be proper or required under Falcon, it was

no abuse of discretion here.

Given the wide discovery allowed on the

individual plaintiff's claims, we hold that

the district court did not abuse its discre

tion by foreclosing discovery on plaintiffs'

pattern and practice claims. The district

court found that no one of the individual

plaintiffs had established a prima facie

case of discrimination by UPS. For the

foregoing reasons, the decision of the

district court is

AFFIRMED.

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

CHARLOTTE DIVISION

D-C-82-323-P

MARCUS ARDREY, JAMES CHERRY, )

BESSIE EASTERLING, et al., )

)Plaintiffs, )

)

vs- ) 0 R D E R

)UNITED PARCEL SERVICE, )

)Defendant. )

___________________________________)

The Plaintiffs filed this action on May

20, 1982 alleging they were discriminated

against by the Defendant because of race,

sex, and age in violation of 42 U.S.C.

Section 2000e et seq. ("Title VII"), 42

U.S.C. Section 1981 (Section 1981) and 29

U.S.C. Section 621 et seq. ("ADEA"). By

Order of April 9, 1984 the ADEA claims were

dismissed. The trial was heard before the

undersigned on November 26, 27, 28 and

December 21, 1984 in Charlotte, North

Carolina. The Plaintiffs were represented by

- 3 0 A -

a

Michael A. Sheely and the Defendant was

represented by William W. Sturges. After

full trial of the matter, the Court, having

carefully considered the testimony and

exhibits, enters the following findings of

fact and conclusions of law:

FINDINGS OF FACT

(1) The Defendant, United Parcel

Service ("UPS") is a corporation

engaged in the interstate trans

portation of parcels. It.employs

in excess of fifteen employees and

is an "employer" within the meaning

of 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e— (b) and

a person" within the meaning of

42 U.S.C. Section 1981.

(2) Local Union No. 71 of the Teamsters

is the bargaining agent at UPS for

the bargaining unit in which the

majority of the Plaintiffs are

members. The positions covered by

the collective bargaining agreement

package car drivers, feeder

drivers, part-time loader/unload—

ers, sorters, car washers, mechan

ics, and building maintenance. The -31 A-

policy of UPS in reference to

full-time bargaining unit posi

tions provides that for every

three openings two openings would

be filled by part-time bargaining

unit employees and the third open

ing would be filled from the

street.

(3) There are twelve Plaintiffs in

this litigation who were all

employed at the West Carolina

District of UPS. This district

encompasses the western part of

North Carolina and all of South

Carolina.

(4) The Plaintiff, Marcus Ardrey, a

black male is currently employed by

UPS as a full-time car washer

shifter. He asserts claims of

racial discrimination in the denial

of package car driver position and

preloader position.

(5) The Plaintiff, James Cherry, a

black male, is currently employed

by UPS as a full-time package car

driver. He asserts claims of

racial discrimination in the denial

-32A-

of a preloader position and in the

issuing of warnings to him. In

addition, he claims the warnings

were issued in retaliation for his

opposition to practices illegal

under Title VII.

(6) The Plaintiff, Bessie Easterling

Brown, a black female, is cur

rently employed by UPS as a feeder

driver. She alleges racial dis

crimination in the issuance of

warnings to her, the denial of

time off, her one day discharge

and her general treatment by the

supervisors.

(7) The Plaintiff, Lewis Funderburk, a

black male, is currently employed

by UPS as a feeder driver. He

alleges racial discrimination in

the assignment of feeder driver

equipment.

(8) The Plaintiff, Horace Jenkins, a

black male over forty, was for

merly1 employed by UPS as a package

1

There is a pending EEOC charge about (continued)

-33A- .

car driver. He alleges age and

racial discrimination in the

denial of light duty work, the

removal of the responsibility of

"call tags" and "one shots" and

the assignment of equipment. His

ADEA claim has already been dis

missed and summary judgment in

favor of UPS was granted on his

light duty claim.

(9) The Plaintiff, Joyce Massey, a

black female, was formerly

employed by UPS as a part-time

simulator. She alleges sex and

race discrimination in her dis

charge after she was laid off by

UPS. She was not a member of Local

Union No. 71.

(10) The Plaintiff, Eugene Neal, a black

male, is currently employed by UPS

as a feeder driver. He alleges

racial discrimination and retalia

tion in the denial of a supervisor

position and in assigning overtime

work. He further testified that

Mr. Jenkins' possible reemployment in 1984.

The charge is still pending before the EEOC

and is not included in this litigation.

. - 3 4 A -

racial discrimination exists in

the assignment of feeder driver

equipment.

(11) The Plaintiff, Matthew Smith, a

black male, is currently employed

by UPS as a feeder driver. He

alleges racial discrimination in

the assignment of feeder driver

equipment and the issuance of

warnings and suspensions.

(12) The Plaintiff, Carl Watts, a black

male, is currently employed by UPS

as a part-time loader. He alleges

racial discrimination in the denial

of a package car position and in

the issuance of warnings.

(13) The Plaintiff, Cheryl Pettigrew, a

black female, was formerly

employed by UPS as a tracer clerk.

She alleges racial discrimination

in her treatment by her supervisor,

her training and her subsequent

discharge.

(14) The Plaintiffs, Jerome Morrow and

Henry Tyson, black males, are cur

rently employed by UPS as full-

• - 3 5 A- -

time car wash shifters. They

allege racial discrimination by

having to work in a racist atmos

phere .

(15) All of the Plaintiffs allege

racial discrimination by being

subjected to work in a racist

atmosphere.

(16) All of the Plaintiffs filed a

timely charge with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission

("EEOC") and exhausted their

administrative remedies.

A. ARDREY - PACKAGE CAR DRIVER

(1) On April 7, 1980 Mr. Ardrey

applied for a full-time package

car position. His application

revealed he was convicted on July

16, 1979 of a DUI and his license

was suspended for six months.

(2) Applicants for driving jobs must

meet designated pre-qualification

requirements before they are

accepted as candidates to qualify

as drivers. One of these require-

- 3 6 A - -

ments is that an applicant must

have an acceptable driving record

for the past three years. Such a

record has been defined as one

that does not have a license

suspension or revocation within

the past three years for, among

other reasons, driving under the

influence.

(3) Mr. Ardrey was denied the opportu

nity to qualify for a driving job

because he did not have an accept

able driving record for the pre

ceding three years because of the

DUI conviction.

There is not any evidence that any

white person was allowed to qualify

without meeting the three year

clean record requirement. Mr.

Ardrey does not contend that the

Company's failure to qualify him

because of his DUI was a pretext

for discrimination.

(4) Mr. Ardrey complains because he was

mistakenly told by two white

management employees that it was

only two years. Mr. Johnson, a

- 3 7 A -

black supervisor, told Mr. Ardrey

that it was three years. It is

not clear why Mr. Ardrey contends

the mistake is suppose to corre

late to race.

(5) The Court finds that Mr. Ardrey

failed to show that in applying

for the package car position he

was treated differently because of

his race. (The Plaintiff's

Proposed Findings of Fact also

state that Mr. Ardrey failed to

prevail on this claim.)

PRELOADER - ARDREY AND CHERRY

1. Ardrey's Training

(1) Mr. Ardrey was hired by UPS in

August 1973 as a part-time trailer

unloader. He was in the military

between August 1975 and August

1979. In October 1979 he

returned to UPS as a part-time

unloader.

(2) On February 11, 1980 Mr. Ardrey

began training for a full-time

preloader position on the sortrac.

The qualification period is thirty

days.

(3) The sortrac is a 250 feet long

conveyor belt with twelve slides

on each side of the conveyor belt.

Belts carry packages which are

diverted down the slides for load

ing into package vans. There are

approximately forty package cars

parked on each side at the end of

the slides for loading. The

slides are eight to ten feet long

and ten feet wide. The higher end

of the slide is about five and a

half feet and the lower end is

about three feet. There are return

conveyor belts beneath the slides.

(4) Preloaders also work in the "box

line" area which is next to the

sortrac. Packages in the boxline

are delivered to the preloaders by

being placed in cages which are on

a continually running conveyor

belt. The parties disagree as to

what is the easiest area to work

on the sortrac.

(5) The keyers divert packages to the

slides and cages. A package which

- 3 9 A -

is incorrectly keyed and does not

belong on a slide is a missort or