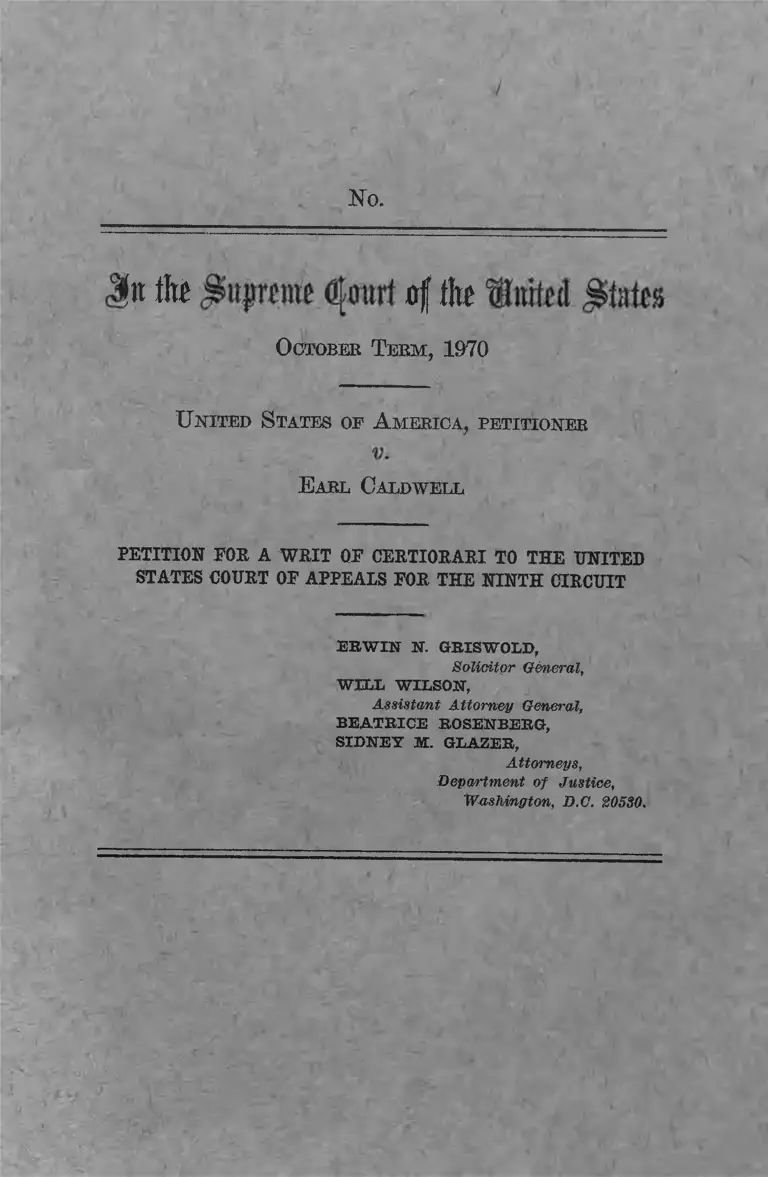

United States v. Caldwell Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

December 31, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Caldwell Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1970. ce507157-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/46195a18-2d39-462b-99e8-19edc465bfdd/united-states-v-caldwell-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Ko.

\vL to of to

OoTOBEE Teem, 1970

U nited S tates of A mebic a, petitionee

E ael Caldwell

PETITION FOE A W EIT OP CEETIOEAEI TO THE ITNITED

STATES COUET OP APPEALS FOE THE NINTH GIECUIT

e e w i n 3sr. g e i s w o l d ,

SoUoltpr General,

W3XL WILSON,

Assistant Attorney General,

BEAXEICE ROSENBEEG,

SIDNEY M. GLAZER,

,1 Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington, B.C. W5S0.

I N D E X

Page

Opinions below______________________________________ 1

Jurisdiction_________________________________________ 1

Question presented___________________________________ 2

Statement__________________________________________ 2

Keasons for granting writ_____________________________ 6

Conclusion__________________________________________ 10

Appendix A_________________________________________ 11

Appendix B _________________________________________ 33

Appendix C_________________________________________ 34

C IT A T IO N S

Cases:

Alderman v. United States, 394 U.S. 165____________ 3

Blair v. United States, 250 U.S. 273________________ 7

Brown v. Walker, 161 U.S. 591_____________ 7

Garland v. Torre, 259 F. 2d 545, certiorari denied,

358 U.S. 910__________________________________ 6

Hale V. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43_______________________ 7

Katz V . United States, 389 U.S. 347________________ 7

Roviaro v. United States, 353 U.S. 53________________ 7

United States v. Bryan, 339 U.S. 323________________ 7

Eule:

Kule 6(g) F.K. Cr. P_____________________________ 2

(I)

411- 861— 70-

Jn ih Ofowrl of tfe MnM plates

October T erm , 1970

J7o.

U nited S tates of A aierica, petitioner

V.

E arl Caldwell

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

The Solicitor General, on behalf of the United States

of America, petitions for a writ of certiorari to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Mnth Circuit in this case.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (App. A, infra)

is not yet reported. The opinion of the district court

is reported at 311 F. Supp. 358.

j u r i s d i c t i o n

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered

on November 16, 1970 (App. B, infra). The jurisdic

tion of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

(I)

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether a newspaper reporter who has published

articles about an organization can, under the First

Amendment, properly refuse to appear before a grand

jury investigating possible crimes by members of that

organization who have been quoted in the published

articles.

STATEMENT

On June 5, 1970, the district court found respondent

Caldwell, a newspaper reporter, guilty of civil con

tempt for refusing to appear before a federal grand

jury in the ISTorthern District of California (1 R. 44-

46). ̂ On appeal, the contempt judgment was reversed.

Respondent, a reporter for the New York Times,

has written a number of articles published in that news

paper about the Black Panther Party. In an article

published in the Times on December 14,1969, he quoted

David Hilliard, a Panther leader, as saying that the

only solution to oppressive government is “armed

struggle.” The article also reported that the “Panthers

have picked up guns” in their revolutionary struggle.

At the time of its publication Hilliard was under in

dictment for threatening to kill the President, having

1 The district court committed respondent to imprisonment

until such time as he might express an intent to testify or until

such time as the term of the grand jury expires, whichever is

earlier. It stayed its order pending the final disposition of the

appeal. Under Eule 6(g), F.E. Cr. P., no grand jury may serve-

more than 18 months. The grand jury here was empaneled on

May 7, 1970, succeeding a prior grand jury. See note 4, p. 4, infra.

stated in a public speech that ‘'We will kill Richard

Mxon.” ^

Subsequently, respondent was subpoenaed to appear

before a federal grand jury investig'ating, among

other things, activities of members of the Panthers.

He moved to quash the subpoena on the ground that,

as a reporter, he should be relieved of any obligation

to appear before the grand jury under the First

Amendment. Alternatively, he requested a protective

order prohibiting grand jury interrogation “concern

ing any confidential interviews or information which

he had obtained exclusively by confidential interviews”

(2 R. 1-2, 29).'® This, he asserted, would include all

unpublished interviews with the Panthers; however, he

indicated a willingness to affirm “before the grand

jury—or in any other place—the authenticity of

quotations attributed to Black Panther sources in his

published articles” (2 R. 11, see 2 R. 49). Respond-

enPs position rested essentially on the claim that his

appearance alone at the secret proceedings would be

interpreted by the Black Panthers “ as a possible dis

closure of confidences and trusts” that would cause

“the Panthers and other groups” to refuse to speak to

him and destroy his effeetiveness as a new^spaperman

(2R. 50-51).

̂This threat against the President was repeated in three is

sues of a magazine published by the Black Panther Party.

® He also contended that the court should conduct an inquiry,

pursuant to Alderman v. United States. 391 U.S. 165, to deter

mine whether the subpoena was the product of illegal electronic

surveillance (2 R. 31-32). The district court held that respondent

had no standing to object, and the court of appeals did not reach

the question.

The district court denied the motion to qucash and

directed respondent to appear, subject to the follow

ing provisos, 311 P. Supp. at 362:

(1) That * * * Earl Caldwell * * * shall not be

required to reveal confidential associations,

sources or information received, developed or

maintained by him as a professional Jotmialist

in the course of his efforts to gather news for dis

semination to the public through the press or

other news media.

(2) That specifically, without limiting para-

grapli (1), Mr. Caldwell shall not be required to

answer questions concerning statements made to

him or information given to him by members of

the Black Panther Party unless such statements

or information were given to him for publica

tion or public disclosure;

(3) That, to assure the effectuation of this

order, Mr. Caldwell shall be permitted to consult

with his counsel at any time he wishes during

the course of his appearance before the grand

jury * * *.

The court further stated that it would entertain a

motion for modification of its order ‘‘at any time upon

a showing by the Grovernment of a compelling and

overriding national interest in requiring Mr. Cald

well’s testimony which cannot be served by any alter

native means ***.” “

̂The court order was originally entered on April 8, 1970,

during the term of a previous grand jury. (2 II. 232-236). After

that term expired and a new grand jury was empaneled on

May 7,1970, respondent was served with a new subpoena ad testi-

fmndum. to appear before the newly empaneled grand jury

and the court again denied a motion to quash, reissuing on June 4,

1970, its previous order limiting the scope of the grand jury's

inqidry (1 K. 36-41). It is this latter order that the court of

appeals rerdewed.

In reversing, the court of appeals agreed with the

district court that the First Amendment accords news

paper reporters a qualified privilege to refuse to an

swer questions in response to a grand jury subpoena.

I t went further, however, to conclude that because

grand jury joroceedings are by nature secret, an order

limiting the scope of inquiry did not, “by itself, ade

quately protect the First Amendment freedoms at

stake in this area” (App. A., p. 25, infra). Finding

that respondent had established a relationship of trust

and confidence with the Black Panthers which rested

“on continuing reassurance” that his handling of news

and information has l^een discrete, the court, below

reasoned as follows (App. A., p. 24, infra).

This reassurance disappears when the re

porter is called to testify behind closed doors.

The secrecy that surrounds Grand Jury testi

mony necessarily introduces uncertainty in the

minds of those who fear a betrayal of their con

fidences. These uncertainties are compounded

by the subtle nature of the journalist-informer

relation. The demarcation between what is con

fidential and what is for publication is not

sharply dra’wn, and often depends upon the

particular context or timing of the use of the

information. Militant groups might very under

standably fear that, under the pressure of exam

ination before a Grand Jury, the witness may fail

to protect their confidences with quite the same

sure judgment he invokes in the normal course

of his professional work.

Accordingly, it held that before respondent could be

ordered to appear “the Government must resx>ond by

demonstrating a compelling need for the witness’ pres

ence” (App. A., p. 27).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT

This case does not raise the question whether a

newspaperman—like an attorney or a doctor or a

clergyman—can refuse to disclose information that

he has received as a matter of professional confidence.

That question, in the absence of statute, is not without

difficulty, see Garland v. Torre, 259 F. 2d 545, 550

(C.A. 2), certiorari denied, 358 U.S. 910, but it is un

likely to arise in a federal context since the Depart

ment of Justice, as a matter of policy, does not seek

confidential information in the absence of an over

riding need.** I t does not arise in this case, since the

government did not appeal from, and does not here

contest, the order of the district court specifically pro

tecting respondent from disclosure of any professional

confidences unless the government first convinces the

court of its specific need. Rather, the question that the

decision of the court of appeals raises is the narrower

question whether the First Amendment gives a re

porter an absolute right to refuse to appear before a

grand jury to answer any questions, even questions

about non-confidential matters, unless the government

first shows a specific compelling need. That is a vital

question of first impression, and it plainly calls for

this Court’s review.

® See the Attorney General's recent guidelines for subpoenas to

news media, set forth in Appendix C Iiereto, pp. 3A-36, infra.

7

In Katz V. United States, 389 U.S. 347, 351, this

Court recognized that “ [W]hat a person knowingly

exposes to the public, even in his own home or office, is

not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection”. The

same principle applies equally to any privilege with re

spect to confidential information, whether or not it

arises under the First Amendment. Assuming that

respondent has a right to refuse to disclose informa

tion he receives in confidence, there is no reason why

that privilege should extend to non-confideutial infor

mation communicated to him for the purpose of pub

lication. This is especially true where the non-confiden-

tial information to which the inquiry is directed has in

deed been published in a widely circulated newspaper.

Compare, e.g., Roviaro v. United States, 3'53 U.S. 53,

60-61. The effect of the decision below is, however, to

give a reporter a wholly unique privilege (albeit quali

fied) to refuse to testify in response to a grand jury sub

poena about matters concededly non-confidential in

nature.

I t has long been settled that the giving of testi

mony and the attendance upon court or grand jury in

order to testify are public duties which every person

within the jurisdiction of the government is bound to

perform upon being properly summoned. Blair v.

United States, 250 U.S. 273, 281; United States v.

Bryan, 339 U.S. 323; Brotvn v. Walker, 161 U.S. 591,

600. As this Court observed in Blair (250 U.S. at 282) :

He [the witness] is not entitled to set limits

to the investigation that the grand jury may

conduct * * * I t is a grand inquest, a body

411- 861— 70— 2

with powers of investigation and inquisition,

the scope of whose inquiries is not to be limited

narrowly by questions of jjropriety or forecasts

of the probable result of the investigation, or by

doubts whether any particular individual will be

found properly subject to an accusation of

crime. As has been said before, the identity of

the offender, and the precise nature of the of

fense, if there be one, normally are developed at

the conclusion of the grand jury’s labor, not at

the beginning. Hendricks v. United States, 223

U.S. 178, 184.

And much earlier in Hale v. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43,

65, the Court said: “I t is impossible to conceive

that * * * the examination of witnesses must be

stopped until a basis is laid by an indictment formally

preferred, when the very object of the examination is

to ascertain who shall be indicted.”

This broad power enables the grand jury to pursue

all leads, and gives it the right to investigate on its

own initiative. I t need establish no factual Ijasis for

commencing an investigation, and can pursue rumors

which further investigation may prove groundless. In

short, the grand jury need not have probable cause

to investigate; rather its function is to determine if

probable cause exists. Similarly, a grand jury has

never been required to make any preliminary show

ing as a foundation for calling a particular person—

whatever his statiis or whatever privilege he might

assert—as a witness. The imposition of such precon

ditions upon grand juries would severely impede their

performance of their traditional functions.

9

Moreover, we do not believe that respondent has

asserted substantial grounds in favor of the extraor

dinary limitations that he would impose upon grand

jury proceedings. He asserts that his tenuous rela

tionship with the Black Panthers— t̂he source of the

non-confidential information that he reports—would

be destroyed by their fear that “under the pressure

of examination before a Grand Jury, the witness may

fail to protect their confidences with quite the same

sure judgment he involves in the normal course of his

professional work.” However, the Black Panthers

cannot be sure that respondent has not already spoken

about them, or will not in the future speak about

them, to other governmental agencies, or law enforce

ment officials. Their faith in him must therefore be

under constant re-examination without regard to his

grand jury appearance. Where, as here, he has ex

plicit protection against disclosure of confidential in

formation by virtue of a court order, there is no

reasonable basis for fear that confidences will be

betrayed.

We submit that the First Amendment does not

grant respondent immunity from appearing before

the grand jury to testify, at the very least, that he

did indeed hear the words quoted in Ids articles; that

they were made seriously and not in jest. Moreover,

from the published articles it appears that he may

have other information of a non-confidential nature

which would be of interest to the grand jury. Since

respondent may under the present court order claim

a privilege as to particular questions at the time they

10

are asked, the grand jury should not in this ease,

any more than it is in other cases, be required to pre

determine and disclose the scope of its investigation

as a condition to calling before it a reporter who has

uiidertaken to make public many statements, includ

ing allegedly direct quotations from a number of

people.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, it is therefore respectfully

submitted that the petition for a writ of certiorari

should be granted.

E rw in IST. G-riswold,

Solicitor General.

W ill W ilson,

Assistant Attorney General.

B eatrice R osenberg,

S idney M. B lazer,

Attorneys.

D ecember 1970.

APPENDIX A

In the United States Court of Appeals for the

Ninth Circuit

No. 26025

In the Matter of the Application of E arl Caldwell

and N ew Y ork T im es Company for an Order

Quashing Grand Jury Subpoenas,

E arl Caldwell, appellant

V.

U nited S tates op A merica, appellee

On Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Northern District of California

Before: Merrill and E ly, Circuit Judges, and

JA M ESO N , District Judge ^

Merrill, C ircu it J u d g e :

Earl Caldwell appeals from an order holding him

in contempt of court for disregard of an order direct

ing him to appear before the Grand Jury of the

United States District Court for the Northern Dis

trict of California pursuant to a subpoena issued by

the Grand Jury.

Appellant is a black news reporter for the New

York Times. He has become a specialist in the re

porting of news concerning the Black Panther Party.

^Honorable William J. Jameson, United States District

Judge for the District of Montana, sitting by designation.

( 11)

12

The Grand Jm y is engaged in a general investigation

of the Black Panthers and the possibility that they

are engaged in criminal activities contrary to federal

law.

In order to protect First Amendment interests as

serted by appellant, the District Court order of at

tendance, which appellant disregarded, expressly

granted appellant the privilege of silence as to certain

matters until such time as the Government should

demonstrate “ a compelling and over-riding national

interest in requiring Mr. Caldwell’s testimony which

cannot be served by any alternative means.” This pro

tective order provided:

(1) That * * * he shall not be required to

reveal confidential associations, sources or in

formation received, developed or maintained

by him as a professional journalist in the course

of his efforts to gather news for dissemina

tion to the public through the press or other

news media.

(2) That specifically, without limiting para

graph (1), Mr. Caldwell shall not be required

to answer questions concerning statements

made to him or information given to him by

members of the Black Panther Party unless

such statements or information were given to

him for publication or public disclosure.

(3) That, to assure the effectuation of this

order, Mr. Caldwell shall be permitted to con

sult with his counsel at any time he wishes dur

ing the course of his appearance before the

grand jury * * *.

Appellant contends that the privilege granted by

the District Court will not suffice to protect the First

Amendment interests at stake; that unless a specific

need for his testimony can be shown by the United

13

States lie should be excused from attendance before

the Grrand Jury altogether. Thus it is not the scope

of the interrogation to which he must submit that is

here at issue; it is whether he need attend at all.

The ease is one of first impression and one in which

nevfs media have shown great interest and have ac

cordingly favored us with briefs as ‘amici curiae. As

is true with many problems recently confronted by

the courts, the case presents vital questions of public

policy; questions as to how competing public interests

shall be balanced. The issues require us to turn our

attention to the underlying conflict between public

interests and the nature of such competing interests.'’

While the United States has not appealed from

the grant of privilege by the District Court (which it

opposed below) and the propriety of that grant is

thus not directly involved here, appellant’s conten

tions here rest upon the same First Amendment foun

dation as did the protective order granted below.

Thus, before we can decide whether the First Amend

ment requires more than a protective order delimit

ing the scope of interrogation, we must first decide

whether it requires any privilege at all..

̂Where, as here, the alleged abridgement of First .Amend

ment interests occurs as a by-product of otherwise permissible

governmental action not directed at the regulation of speech

or press, “resolution of the issue always involves a balancing

by the courts of the competing private and public interests

at stake in the particular circumstances shown.” Barenblatt v.

Unitexl States. 360 IJ.S. 109, 126 (1959) ; see, e.g., Kmiisberg

V. State Bar, 366 U.S. 36, 50-51 (1961); Bates v. LittZe Roch,

361 IJ.S. 516 (1960) ; N A A C P v. Alatbama, 357 ILS. 449, 460-

67 (1958) ; Kalven, “The Xew York Times Case: A Xote on

‘The Central Meaning of the First Amendment,’ ” 1964, Sup.

Ct. Eev. 191, 214-16 (1964).

14

The Protective Order

The proceedings below were initiated by a motion

by appellant to quash subpoenas issued by the G-rand

JLiry.̂ ’ In his moving papers appellant’s position was

that the “inevitable effect of the subpoenas will be to

suppress vital First Amendment freedoms of Mr.

Caldwell, of the New York Times, of the news media,

and of militant political groups by driving a wedge

of distrust and silence between the news media and

the militants, and that this Court should not coimte-

nance a use of its process entailing so drastic an

incursion upon First Amendment freedoms in the ab

sence of compelling governmental interest—not shown

here—in requiring Mr. Caldwell’s appearance before

the Grand Jury.”

® The first subpoena was served February 2, 1970. It directed

appellant to appear and testify and to bring with him notes

and tape recordings of interviews reflecting statements made for

publication by officers and spokesmen for the Black Panther

Party concerning the aims, purposes and activities of the orga

nization. On March 16, after appellant had protested the scope

of the subpoena, a second subpoena was served. It simply re

quired appellant’s attendance. Appellant’s motion to quash was

directed to both subpoenas. The court denied the motion and

directed compliance with the March 16 subpoena subject to the

protective order. Appellant appealed that decision; but the

appeal was dismissed, apparently on the ground that the Dis

trict Court order was not appealable. By then the term of the

Grand Jury had expired, and a new Grand Jury was sworn.

A new subpoena ad testificandum was served on May 22, 1970.

All proceedings had in connection with the earlier subpoenas

were made a part of the record of the proceedings concerning

this last subpoena. A new order directing attendance was is

sued; this order also contained the protective provisions or

privilege. It is appellant’s disregard of that order which re

sulted in the judgment of contempt now before us.

15

Amici curiae solidly supported appellant in this

position. The fact that the subpoenas would have a

“chilling effect” on First Amendment freedoms was

impressively asserted in affidavits of newsmen of rec

ognized statute, to a considerable extent based upon

recited experience. Appellant’s own history is related

in his moving papers:

Earl Caldwell has been covering the Pan

thers almost since the Party’s beginnings.

Initially received hesitatingly and with caution,

he has gradually won the confidence and trust

of Party leaders and rank-and-file members. As

a result, Panthers will now discuss Party vieivs

and activities freely with Mr. Caldwell. * *

Their confidences have enabled him t'o write in

formed and balanced stories concerning the

Black Panther Party which are imavailalDle to

most other newsmen.

* -X- * ^

I f Mr. Caldwell were to disclose Black Panther

confidences to governmental officials, the grand

jury, or any other person, he would thereby

destroy the relationship of trust which he pre

sently enjoys with the Panthers and othei> mili

tant groups. They would refuse to speak to him;

they would become even more reluctant than

they are noŵ to speak to any newsmen; and the

news media wmiild thereby be vitalljT' hampered

in their ability to cover the views and activi

ties of the militants.

The response of the United States di.sputed the con

tention that First Amendment freedoms were endan

gered.

Newsmen filing affidavits herein allege that

they fear, in effect, that the Black Panthers

will refrain from furnishing them with news.

411- 861— 70-

16

This contention, is specious. Despite some as

sertions by Black Panther leaders to the con

trary, the Black Panthers in fact depend on

the mass media for their constant endeavor to

maintain themselves in the public eye and thus

gain adherents and continued support. The}'

have continued un(;easing-ly to exploit the facili

ties of the mass media for their own X)urposes.

Assuming, arguendo, that this statement is eorrect,

it is not fully responsive to the claim that First

Amendment fi.'eedonis arc; endangered. The premise

underlying the (xOvernnu;nt’s statement is that First

Amendment interests in this area are adecpiately

safeguarded as long as potential news makers do not

cease using the media as vehicles for their communi-

cation with the public. But the First Amendment

means more than that. I t exists to preserve an “un-

traniineled press as a vital soiirce of public informa

tion,” Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U.S. 233,

250 (1936). Its objective is the maximization of the

“spectrum of available knowledge,” Gristvold v. Con

necticut, 381 U.S. 479, 482 (1965). Thus, it is not

enough that Black Panther press releases and public

addresses by Panther leaders may continue unabated

in the wake of subpoenas such as thĉ one here in

question. I t is not enoiigh that the public’s knowh'dge

of groups such as the Black Panthers sliould l,)e con-

tinc’d to their delilcerate public pronouncements or

distant new's accounts of their occasional dramatic

forays into the public view.

The need for an untrammeled press takes on spe

cial urgency in times of widespread protest and dis

sent. In such times the First Amendment protections

exist to maintain communication with dissenting

groups and to provide the public with a wide range of

information about the nature of protest and hetero-

17

doxy. See, e.g., Associated Press v. United States,

326 U.S. 1, 20 (1945); Thornhill v. AlaMma, 310 U.S.

88,102 (1940).

The affidavits contained in this record required the

eonelusion of the District Court that “ eoinpelled dis

closure of information received by a journalist within

the scope of such confidential relationships jeopar

dizes those relationships and thereby impairs the jour

nalist’s ability to gather, analyze, and publish the

news. ’ ’

Accordingly we agree with the District Court that

First Amendment freedoms are here in jeopardy.

On the other side of the balance is the scope of the

(Irand Jury’s investigative power.

In his moving papei-s appellant complained that the

Grovernment had not disclosed the subject, direction

or scope of the Grand Jury inquiry and that efforts

of counsel to obtain some specification had been un

availing.

Government counsel has said only that the

grand jury has “broad investigative powers,”

that he cannot “limit the inquiry of the grand

jury in advance,” and that the subject and

scope of the grand jury’s investigation is “no

concern of a subpoenaed witness.”

The Government in opposing appellant’s motion to

quash, stated its position in these terms:

On the basis of what he has written, directly

quoting statements made to him for publication

by spokesmen for the Black Panther Party, Earl

Caldwell obviously can give and should come

forward with evidence which will be helpful to

the Grand Jury in its inquiry.

Thus, as is true in innumerable instances, the Grand

Jury does not know what it wants from this witness.

I t wants to find out what he knows that might shed

18

light on the general problem it is investigating. This

type of wide-ranging, open-ended inquiry is, of course,

typical of many Grand Jury proceedings. See Hale v.

Henkel, 201 U.S. 43 (1906); Note, “The Grand Jury

as an Investigatory Body,” 74 Harv. L. Rev. 590, 591-

92 (1961). I f the privilege of silence as defined by the

District Court is made available to news gatherers, the

Grand Jury will be deprived of their assistance as

witnesses in such general investigations.

The question posed below was whether, as a matter

of law, this loss to the Grand Jury, this impediment

to its traditionally broad scope of inquiry, outweighs

the injury to First Amendment freedoms.

The Government stresses the historic traditions of

the Grand Jury with its extensive powers of investi

gation, see, e.g.. Hale v. Henkel, stip-ra, and the cor

responding duty of the citizenry to come before the

Grand Jury to give testimony. United States v. Bryan,

339 U.S. 323 (1950); Blair v. United States, 250 U.S.

273 (1919). But these general propositions of Govern

ment authority necessarily are tempered by constitu

tional prohibitions and other exceptional circum

stances. See United States v. Bryan, supra, at 331;

Blair V. United States, supra, at 281-82. In this re

spect we find guidance in the Supreme Court deci

sions regarding conflicts between First Amendment in

terests and legislative investigatory n e e d s t h e

Court has required the sacrifice of First Amend-

'‘Like the Grand Jury, legislative committees have long

been viewed as invaluable instruments of governance. See, e.g.,

BarenUatt v. United States, 360 U.S. 109, 111 (1959); United

States V. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41, 43 (1953).

19

ment freedoms only where a compelling need for the

IJartieular testimony in question is demonstrated."

If the Grand Jury may require appellant to make

available to it information obtained by him in his

capacity as news gatherer, then the Grand Jury and

the Department of Justice have the power to appro

priate appellant’s investigative efforts to their own

behalf—^̂to convert him after the fact into an inves

tigative agent of the Government. The very concept

of a free press requires that the news media be ac

corded a measure of autonomy; that they should be

free to pursue their own investigations to their own.

ends without fear of governmental interference, and

that they should be able to protect their investigative

processes. To convert news gatherers into Department

of Justice investigators is to i.nvade the autonomy

of the press by imposing a governmental function

upon them. To do so where the result is to diminish

their future capacity as news gatherers is destructive

of their public function." To accomplish this where it

has not been shown to be essential to the Grand Jury

' DeGregory v. Attorney General o f Neio Hampshire, 383

U.S. 825 (1966) ; Gihson v. Florida Legislative Investigation

OommAttee, 372 IT.S. 539 (1963); N A AG P v. Alabama, 357

U.S. 449, 460-67 (1958); Sioeesy v. Neio Ilam/pslvire, 354 U.S.

235 (1957) ; Y/atkins v. United States, 354 U.S. 178 (1957) ;

United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41 (1953). It is .necessary

that, as the investigation proceeds, step-by-step, “an adequate

foundation for inquiry must be laid.” Gihson v. Florida Legis

lative Investigation Committee, snyra, at 557.

® It is a paradox of the Government’s position that, if groups

like the Black Panthers cease taking reporters like appellant

into their confidence, these journalists will, in the future, be

unable to serve a public function either as news gatherers or as

prosecution witnesses.

20

inquiry simply cannot be justified in the public in

terest.

l^hirther it is not unreasonable to expect journalists

everywh(‘re to temper their reporting so as to reduce

the probability that they will be required to submit

to interrogation. The First Amendment guards

against governmental action that induces such self-

censorship. See New York Tim.es v. Sullivan, 376

U.S. 254, 279 (1964); Smith v. California, 361 U.S.

147 (1959).

I t was on such, considerations as these that the

balance was struck by the District Court. I t ruled:

When the exercise of the grand jury power of

testimonial compulsion so necessary to the ef

fective functioning of the court may impinge

upon or repress First Amendment rights or

freedom of speech, press and association, which

centuries of experience have found to be indis

pensable to the survival of a free society, such

power shall not be exercised in a manner likely

to do so until there has been a clear showing

of a compelling and overriding national in-

t(0‘ost that cannot be served by any alternative

means.

Finding that tlie Government had shown no com

pel ing or over-riding national interest for testimony

of the sort specified, the District Court imposed the

limits we have set forth earlier in this opinion. It

reserved jurisdiction to modify its order on a showing

of such governmental interest which cannot be served

by means other than by appellant’s testimony.

We agree with the District Court that the First

Amendment requires this qualified privilege, and we

21

find notliiiig unreasonable in the terms in which it

was there defined/

Attendance

We have noted, the issue upon this appeal goes

beyond the (|uestion of a privileg'e to decline to re-

.spond to interrogation in certain ai-('as. The District

Court ruled tliat, although protec.ted 1>y its limited

privilege, Caldwell was reqiiirc'd to rc'spond to the

subjioena by a])pearing ])efor(' tlui (fraud Jury to an

swer (questions not privileged. Appellant contends that

his mere appearance before tlie (fi'and Jury will result

in loss of his news sources. The Cfovernment ques

tions this result.

Garlnnd v. Torre. 259 F. 2d 54-5 (2d Cir.) cert, denied.

358 U.S. 910 (1958), is not to the contrary. That case in

volved a libel suit in which an author attributed alleged de

famatory remarks reported by her to a “network executi\'e."

The author, when called as a witness in the libel action against

the network, claimed a First Amendment privilege not to dis

close the informant’s identity and was held in contempt for

her refusal to divulge the source.

The Second Circuit (per Judge, now ilr . Justice Stewart)

affirmed the judgment of contempt. But, in doing so, it ac

cepted the proposition “that comjnilsory disclosure of tamfl-

dential sources of inforniatioii may entail an abridgement of

press freedom * * *” Id., at 5-18. The test was “wiietlier the

interest to be served by com})e]!ing the testimony of the wit

ness in the present case justifies some im[)airmeut of this First

Amendment freedom,” Id. In that case the court, noted that it

wiis “not dealing here with the use of tlie judicial process to

force a wholesale disclosure of a newspaper’s confidciitial sources

of news nor with a case where the identity of the news source

is of doubtful relevaiice or materiality.” Id., at 549-50. There

the information 'was essential for the trial of plaintiff’s

case; “The question asked of a]5pcllant went to the heart of

plaintiff’s claim.” Id. Thus an over-riding need for tlie specific

testimony was shown.

22

The affidavits on file cast considerable light on the

process of gathering news about militant organiza

tions. ̂ I t is apparent that the relationship which an

effective privilege in this area must protect is a very

tenuous and unstable one. Unlike the relation between

an attorney and his client or a physician and his pa

tient, the relationships between journalists and news

sources like the Black Panthers are not rooted in any

service the journalist can provide his informant apart

® One reporter for the New York Times states: “[0 ]u every

story there is a much subtler and much more important form

of commnnication at work between a reporter and his sources.

It js built up over a period of time working with and writing

about an organization, a person, or a group of persons. The

reporter and the source each develops a feeling for what the

other will do. The reporter senses how far he can go in writing

before the source will stop communicating with him. The

source, on the other hand, senses how much he can talk and

act freely before he has to close off his presence and his in

formation from the reporter. It is often through such subtle

communication that the best and truest stories are written and

printed in The Times, or any other newspaper.”

Appellant relates his own experience as follows: “I began

covering and writing articles about the Black Panthers al

most from the time of their inception, and I myself found

that in those first months that they were very brief and reluc

tant to discuss any substantive matter with me. However, as

tliey realized I could be trusted and that my sole purpose was

to collect my information and present it objectively in the

newspaper and that I liad no other motive, I found that not

only were the party leaders available for in-depfii interviews

but also the rank and file members were cooperative in aiding

mo in the newspaper stories that I wanted to do. During the

time that I have been covering the party, I have noticed other

newspapermen representing legitimate organizations in the news

media being turned away because they were not known and

trusted by the party leadership.

“As a result of the relationship that I have developed, I

have been able to write lengthy stories about the Panthers

23

from the publication of the information so obtained.

G-oldstein, “Newsmen and their Confidential Sources,”

The New Republic 13 (March 21, 1970). The relation

ship depends upon a trust and confidence that is con

stantly subject to reexamination and that depends in

turn on actual knowledge of how news and informa-

that have appeared in The New York Times and have been of

such a nature that other reporters who have not Imown the

Panthers have not been able to write. Many of these stories

have appeared in up to 50 or 60 other newspapers around the

country.

“Tire Black Panther Party’s method of operation with, regard

to members of the press is significantly different from that of

other organizations. For instance, press credentials are not rec

ognized as being of any significance. In addition, interviews

are not normally designated as being ‘backgrounders’ or ‘off

the record’ or ‘for publication’ or ‘on the record.’ Because no

substantive interviews are given until a relationship of trust

and confidence is developed between the Black Panther Party

members and reporters, statements are rarely made to such

reporters on an expressed ‘on’ or ‘off’ the record basis. Instead,

an understanding is developed over a period of time between

the Black Panther Party members and the reporter as to

matters which the Black Panther Party wishes to disclose for

publication and those matters which are given in confidence.”

He concludes: “* * * if I am forced to appear in secret

grand jury proceedings, my appearance alone would be inter

preted by the Black Panthers and other dissident groups as a

possible disclosure of confidences and trusts and would similarly

destroy my effectiveness as a newspaperman.”

A fellow black reporter, on leave of absence from The New

York Times, states: “From my experience, I am certain that a

black reporter called upon to testify about black activist

groups will lose his credibility in the black community gen

erally. His testifying will also make it more difficult for other

reporters to cover that community. The net result, therefore,

will be to diminish seriously the meaningful news available

about an important segment of our population.”

24

tion imparted have been handled and on continuing

reassurance that the handling has been discreet.®

This reassurance disappears when the reporter is

called to testify behind closed doors. The secrecy that

surrounds Grand Jury testimony necessarily intro

duces uncertainty in the minds of those who fear a

betrayal of their. confidences. These uncertainties are

compounded by the subtle nature of the journalist-

informer relation. The demarcation between what is

confidential and what is for publication is not sharply

drawn and often depends upon the particular context

or timing of the use of the information. Militant

groups might very understandably fear that, under

the pressure of examination before a Grand Jury,

the witness may fail to protect their confidences with

quite the same sure judgment he invokes in the nor

mal course of his professional work.

The Government characterizes this anticipated loss

of communication as Black Panther reprisal; as mani

festing a Black Panther demand that, “if you sub

poena Caldwell, we will never speak to you again.”

It argues that it is unthinkable that the American

people would capitulate to such extortion.

But it is not an extortionate threat we face. I t is

human reaction as reasonable to expect as that a client

will leave his lawyer when his confidence is shaken.

The news source has placed no price tag or exaction

on enjoyment of First Amendment freedoms save its

® This is not necessarily true of every news source. In po

litical and diplomatic areas where the source is an under

cover tipster the relationship may well be sufficiently protected

by a privilege not to disclose the source.

25

contirming confidence in the discretion of tlie re-

porterd“

As the Grovernment points out, loss of such a sensi

tive news source can also result from its reaction to

indiscreet or unfavorable reporting or from a report

er’s association with Government agents or persons

disapproved of by the news source. Loss in such a case,

however, results from an exercise of the choice and

prerogative of a free press. I t is not the result of

Government compulsion.

We conclude that the privilege not to answer cer

tain questions does not, by itself, adequately protect

the First Amendment freedoms at stake in this area;

that without implementation in the manner sought

to appellant the privilege would fail in its very pur

pose.

On the other side of the balance is the Grand

Jury’s right to summon this witness before it and in

secrecy compel him to ansAver questions or to resort

to his privilege. I t is not the right to secure appear

ance and testimony that is itself in issue; the Dis

trict Court’s protective order alone would suffice were

that all. I t is the right to compel presence at a secret

interrogation with which we are concerned.

Throughout history secret interrogation has posed

problems and caused unease. See, e.g., Kote, ‘"An His

torical Argument for the Right to Counsel During

Police Interrogation,” 73 Tale L.J. 1000, 1034-15

(1964). We do not doubt that secret interrogation is

in general essential to the integrity and effectiveness

of the Grand Jury process. HoAÂeÂer, implicit in the

Quite a different situation would be presented Avere tlie

demand unrelated to the priAuleged relationship: E.g. “Tlie

police must free our leader.”

36

extraordinary nature of secret interrogations, is the

possibility of conflict with basic rights. When this is

shown to occur it is appropriate to inquire into the

need in the particular case for the specific incursion.

Since compulsion to attend and testify entails the

exercise of judicial iDrocess, it is appropriate that the

inquiry be judicially entertained.

The question, then, is whether the injury to First

Amendment liberties which mere attendance threatens

can be justified by the demonstrated need of the Gov

ernment for appellant’s testimony as to those subjects

not already j)rotected by the privilege.

Appellant asserted in affidavit that there is nothing

to which he could testify (beyond that which he has

already made public and for which, therefore, his

appearance is unnecessary) that is not protected by

the District Court’s order. If this is true—and the

Government apparently has not believed it necessary

to dispute it—appellant’s response to the subpoena

would be a barren performance—one of no benefit to

the Grand Jury. To destroy appellant’s capacity as

news gatherer for such a return hardly makes sense.

Since the cost to the public of excusing his attendance

is so slight, it may be said that there is here no public

interest of real substance in competition with the

First Amendment freedoms that are jeopardized.

If any competing public interest is ever to arise in

a case such as this (where First Amendment liberties

are threatened by mere appearance at a Grand Jury

investigation) it will be on an occasion in which the

witness, armed with his privilege, can still serve a

useful purpose before the Grand Jury. Considering

the scope of the privilege embodied in the protective

order, these occasions would seem to be unusual. I t is

not asking too much of the Government to show that

such an occasion is presented here.

27

In light of these coiisiclerations we hold that where

it has been shown that the public’s First Amendment

right to be informed would be jeopardized by requir

ing a journalist to submit to secret Grand Jury

interrogation, the Government must respond by dem

onstrating a compelling need for the witness’ presence

before judicial process properly can issue to require

attendance.

We go no further than to announce this general

rule. As ŵe noted at the outset, tMs is a case of first

impression. The courts can learn much about the prob

lems in this area as they gain more experience in

dealing with them. For the present we lack the

omniscience to spell out the details of the Govern

ment’s burden “ or the type of proceeding that would

Appellant, in his brief to this court, has carefully spelled

out what he feels would be required; “Specifically, we con

tend that, before it may compel a newsman to appear in grand

jury proceedings under circumstances that would seriously

damage the newsgathering and reporting abilities of the press,

the Government must show at least: (1) that there are rea

sonable grounds to believe the journalist has information, (2)

specifically relevant to an identified episode that the grand

jury has some factual basis for investigating as a possible

violation of designated criminal statutes within its jurisdiction,

and (3) that the Government has no alternative sources of the

same or equivalent information whose use would not entail an

equal degree of incursion upon First Amendment freedoms.

Once this minimal showing has been made, it remains for the

courts to weigh the precise degree of investigative need that

thus appears against the demonstrated degree of harm to First

Amendment interests involved in compelling the journalist’s

testimony.” While there is much to commend this suggestion,

we are not certain that it represents the best or most satis

factory formulation of the requirement. See, for example.

People V. Dohm, et al., Circuit Court of Cook County, Crimi

nal Division, Ao. 69-3808, May 20,1970.

28

accommodate efforts to meet that burden/^ The fash

ioning of specific rules and procedures appropriate

to the particular case can better be left to the District

Court under its retained jurisdiction. Cf., White

Motor Co. V. United States, 372 U.S. 253 (1963).

Finally we wish to emphasize what must already be

clear: the rule of this case is a narrow one. I t is not

every news source that is as sensitive as the Black

Panther Party has been shomi to be respecting the

performance of the “ establishment” press or the ex

tent to which that performance is open to view. It is

not every reporter who so uniquely enjoys the trust

and confidence of his sensitive news source.

The Fourth Amendment Issue

Appellant also moved to quash the Grand Jury

subpoenas on the ground that they were based upon

information obtained by unconstitutional surveillance

of his interviews with Black Panther members. He

sought a hearing to determine whether the subpoenas

were so obtained. Alderman v. United States, 394 U.S.

165 (1969). The District Court denied the motion

solely on the ground that appellant lacked standing

to raise the Fourth Amendment contention. This is

assigned as error.

In light of our disposition of the First Amendment

question in this case, we need not reach this issue. The

United States might never meet the First Amendment

burden imposed upon it by the District Court order

as here implemented. Even if the Govermnent does

meet that burden, the court may not have to reach

this Fourth Amendment claim; the Government’s

Appellant suggests that the Government's specification

of need could be presented in camera to the District Court

with appellant or his counsel present.

sh'o-wing of need for appellant’s testimony may dis

close a basis for the (xovernment’s information which

would present no Fourth Amendment problem. If

such a problem is presented it coidd then be discussed

in light of the specific facts.

Accordingly, we regard decision upon this question

as unnecessary to the present disposition of the case.

We reserve the issue and decline to reach it here.

Reversed and remanded with instructions that the

judgment of contempt and the order directing attend

ance before the Grand Jury be vacated. The District

Court under its retained jurisdiction may enteifain

such further proceedings as may be initiated by the

United States.

J amesox, District Judge (Concurring):

This ease presents narrow issues in the “ delicate

and difficult” task of reconciling the First Amendment

guarantee of freedom of the press with the fair ad

ministration of justice, including the broad investiga

tory power of a grand jury and the obligation of a

witness to testify. While perhaps unnecessary for a

determination of this appeal, it is helpful, in my

opinion, to note the guidelines for resolving conflicts

in this sensitive area, as summarized by Judge, now

Mr. Justice, Stewart, in Garland v. Torre, 259 F. 2d

545, 548-549 (2d Cir.) cert, denied 358 U.S. 910 (1958) :

But freedom of the press, precious and vital

though it is to a free society, is not an absolute.

What must be determined is whether the in

terest to be served by compelling the testimony

of the witness in the present case justifies some

impairment of this First ilmendment freedom.

That kind of determination often presents

a “ delicate and difficult” task. (Citing

cases). * * *

* * * Freedom of the press, hard-won over

the centuries by men of courage, is basic to a

30

free society. But basic too are courts of justice,

armed with the power to discover truth. The

concept that it is the duty of a witness to

testify in a court of law has roots fully as deep

in our history as does the guarantee of a free

press.

I t would be a needless exercise in pedantry

to review here the historic development of that

duty. Suffice it to state that at the foun

dation of the Republic the obligation of a wit

ness to testify and the correlative right of a

litigant to enlist judicial compulsion of testi

mony were recognized as incidents of the judi

cial power of the United States. (Citing

cases). * * *

Without question, the exaction of this duty

impinges sometimes, if not always, upon the

First Amendment freedoms of the witness.

Material sacrifice and the invasion of pei’sonal

privacy are implicit in its performance. The

freedom to choose whether to speak or be silent

disappears. * * *

If an additional First Amendment liberty—

the freedom of the press—is here involved, we

do not hesitate to conclude that it too must give

place under the Constitution to a paramount

public interest in the fair administration of

justice. * * *

As stated in the court’s opinion (note 6) Garland

V. Torre was a civil action for libel.̂ ̂ The obligation

to appear and testify is even stronger and the scope

of inquiry is broader in grand jury investigations. '̂*

As Judge Merrill’s opinion notes, Garland v. Torre did

not involve the “txse of the judicial process to force a whole

sale disclosure of a newspaper’s confidential sources of news

nor with a case where the identity of the news source is of

doubtful relevance or materiality.”

In distinguishing between investigations by a grand jury

and those conducted by commissions created by Congress, Mr.

Justice Douglas noted that the grand jury is the “only ac-

31

The First Amendment rights of appellant were

recognized fully by Judge Zirpoli in providing for

the protective order discussed in the court’s opinion.

While not conceding the validity or propriety of the

qualified privilege granted appellant, the Government

did not seek review of that order on this a p p e a l

The order entered by the district court is adequate

to protect any unnecessary impingement of First

Amendment rights after the appearance of the wit

ness before the grand jury.

Accordingly we are concerned with the narrow

question of whether the Government’s showing of a

“ compelling and overriding national interest that can-

cusatory body in the Federal Government that is recognized

by the Constitution,” and that “[I]t has broad investigational

powers to look into what may be offensive against federal crim

inal law.” Dissenting opinion in Hannah v. Larche. 363 IT.S.

420,499 (1960).

“̂At oral argument counsel for the Government submitted

a press release from the Attorney General settiiig forth new

Department of Justice guidelines for subpoenas to the news

media, in which it is expressly recognized that the “Depart

ment does not approve of utilizing the press as a spring board

for investigations”, and which provide, inter alia, that “[TJhere

should be sufficient reason to believe that the information sought

is essential to a successful investigation—particularly with ref

erence to directly establishing gialt or innocence”; that “[T]he

government should have unsuccessfully attempted to obtain the

information from alternatn'e non-press sources”; that subpoenas

“should normally be limited to the verification of published

information and to such surrounding circumstances as relate

to the accuracy of the published information” ; and tliat “sub

poenas should, wherever possible, bo directed at material in

formation regarding a limited subject matter, should cover a

reasonably limited period of time, and should avoid requiring

production of a large volume of unpublished material.” John

N. Mitchell, “Free Press and Fair Trial: The Subpoena Con

troversy,” an address before House of Delegates, American

Bar xCssociation (August 10, 1970).

32

not be served by any alternative means” may be re

quired in advance of the issuance of a subpoena.

Appellant did not have any express constitutional

right to decline to appear before the grand jury.

This is a duty required of all citizens, hlor has Con

gress enacted legislation to accord any type of priv-

ilege to a news reporter.^® In my opinion the order

of̂ the district court could properly be affirmed, and

this would accord with the customary procedure of

requiring a witness to seek a protective order after

appearing before the grand jury. I have concluded,

however, that Judge Merrill’s opinion properly holds

that tne same result may be achieved by requiring

the G-overnment to demonstrate the compelling need

for the witness’s presence prior to the issuance of a

subpoena and in this manner avoid anj ̂ unnecessary

impingement of First Amendment rights.

As Judge Merrill has suggested, this is a ease of

first impression. I t would seem that the district court

could develop procedures which would not imduly

hamper or interfere with the investigatory powers of

the grand jury. The Government would have the same

burden, except that it would make its showing at a

hearing in advance of the issuance of subpoenas

rather than after the witness appears and seeks a

protective order.

^"Several states have enacted legislation granting qualified

privileges to newsmen.

APPENDIX B

In the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit

No. 26025

(D.C. #Misc. 10426)

l x THE Matter of the Applicatiox of E arl Cald

well AXD New York Times Compaxy foe ax Order

Quashixg Gtraxd J ury Subpoexas ̂ E ari. Caldwell,

APPLICAXT

V.

E xited States of Aaierica

Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Northern District of California.

This cause came on to be heard on the Transerijot

of the Record from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California and was duly

suhmitted.

On consideration whereof, I t is now here ordered

and adjudged by this Court, that the judgment of the

said District Court in this Cause be, and hereby is

reversed and that this cause be and hereby is re

manded to the said District Court with instructions

that the judgment of contempt and the order direct

ing attendance before the grand jury be vacated. The

District Court under its retained jurisdiction may

entertain such further proceedings as may be initiated

by the United States.

Filed and entered November 16,1970.( 3 3 )

APPENDIX C

Department of J ustice,

IFasMngton, D.G., September 2, 1970.

Memo No. 692

To A ll U nited States Attorneys

Subject: Guidelines for Subpoenas to the News Media.

The following guidelines for subpoenas to the news

media are quoted from the address “ Free Press and

Pair Trial: The Subpoena Controversy” by the Hon

orable John N. Mitchell, Attorney General of the

United States, before the House of Delegates, Ameri

can Bar Association, at St. Louis, Missouri, on Au

gust 10, 1970.

W ill W ilson,

Assistant Attorney General,

Crimmal Division.

First: The Department of Justice recognizes that

compulsory process in some circumstances may have

a limiting effect on the exercise of First Amendment

rights. In determining whether to request issuance of

a subpoena to the press, the approach in every case

must be to weight that limiting effect against tlie

public interest to be served in the fair administration

of justice.

Second: The Department of Justice does not con

sider the press “ an investigative arm of the govern

ment.” Therefore, all reasonable attempts shoukl be

made to obtain information from non-press sources

before there is any consideration of subpoenaing

the press. ( 3 4 )

35

Third: I t is the policy of the Department to insist

that negotiations with the press be attempted in all

cases in which a subpoena is contemplated. These ne

gotiations should attempt to accommodate the inter

ests of the grand jury with the interests of the news

media.

In these negotiations, where the nature of the in

vestigation permits, the government should make clear

what its needs are in a particular case as well as its

willingness to response to particular problems of the

news media.

Fourth: I f negotiations fail, no Justice Department

official should request, or make any arrangements for,

a subpoena to the press without the express authori

zation of the Attorney General.

If a subpoena is obtained under such circimistaTices

without this authorization, the Department will—as a

matter of course—^move to quash the subpoena with

out prejudice to its rights subsequently to request the

subpoena upon the proper authorization.

Fifth: In requesting the Attorney General’s au

thorization for a subpoena, the following principles

will apply:

A. There should be sufficient reason to believe that

a crime has occurred, from disclosures by non-press

sources. The Department does not approve of utilizing

the press as a spring board for investigations.

B. There should be sufficient reason to believe that

the information sought is essential to a successful in

vestigation ^particularly with reference to directly

establishing guilt or innocence. The subpoena should

not be used to obtain peripheral, non-essential or

speculative information.

C. The Government should have unsuccessfully at

tempted to obtain the information from alternative

non-press sources.

36

D. Authorization requests for subpoenas should nor

mally be limited to the verification of published in

formation and to such surrounding circumstances as

relate to the accuracy of the published information.

E. Great caution should be observed in requesting

subpoena authorization by the Attorney General for

unpublished information, or where an orthodox First

Amendment defense is raised or where a serious claim

of confidentiality is alleged.

F. Even subpoena authorization requests for pub

licly disclosed information should be treated with care

because, for example, cameramen have recently been

subjected to harassment on the grounds that their

photographs will become available to the government.

G. In any event, subpoenas should, wherever pos

sible, be directed at material information regarding

a limited subject matter, should cover a reasonably

limited period of time, and should avoid requiring

production of a large volume of unpublished material.

They should give reasonable and timely notice of the

demand for documents.

These are general rules designed to cover the great

majority of cases. I t must always be remembered that

emergencies and other unusual situations may de

velop where a subpoena request to the Attorney Gen

eral may be submitted which does not exactly conform

to these guidelines.

U.S . GOVERNMENT PRINTJNG OFFICE; 1970

' ' 7 > X'-. > I. ' '«i^<C<,'v -A, - * V . A 'V ̂ Ar. '-'A, X ' 7 , ■ A X " '1 /' >v . r - -, * ' ~ .. '■‘X. XX '̂ ‘ ̂ '■■o’ . ^ C',ivX, /̂•<' '*A fX ̂ 1 ̂ ̂ X*" 1̂ ̂\ tr ̂ ̂ ' X7\(, ‘'X ]'

■ ' K : r ' . t ; - : ' : ' ■- " : x > > x v

, ̂ 'X ' p ' ' ‘ ' y y ‘A' ^ ’' ' - . Js*-, ’ \ {' f f ^ " ,-i X

' V - \ . < < ■ - \ A ' , - r ̂ ■ < 7. A&'» ^ ‘v X ' \ " '^XV ‘' '"x •' X , . - j X " , A ,' x ‘ X n i-x, ‘ I ' c~\ ^. , - . ^ 'r-t£A ‘X >X .A:^V7 y'7,‘ ' X X X X <X^S^ X’ X ' X " ,;-X""',- x>\7x,\. -X 'Y'‘"X'.rA'?,:;. XXX-;~;>- XX -AS •■;• /rx-./;'aX.,4'' ; -aV̂xx'■• • v x- ‘ --! ̂■x-X'X' x,^;x.;x ■ X -• x'V'xxiXxx >A-- fW-' > -- J „ T ̂ X ,

i ‘ / X - ’■/ X A A > ' X // x".V'V: X'X^^ '

_ ,>^Av ..... L. .. ,. .^l... A.. .X V A A •/ ' ^ X / x X - ■_ A / ; A -̂V - ̂ 'x x A -'X:c XX̂'r ’ X' X ? X'.->v'-jA ,v 'i 'i# > X ’~̂,\ A !-• X -'A Xt ,'

2 '̂ x^v -X ' X > / / V -JX. A.VA'x A .;ivAy :;.t Kf- V>-V .xVXA A"'- -

X '.--fXA-' ' :"’* 'Vx;I'-'AX;"VV/A'-:'^:,v-s ̂ z-'' X'l \ •" ̂ ̂ L ̂ I ~v ̂ . X< V x: ? X'̂ V- ' h,cA'’-iXV '■'X t,,, X-Av ,i

V.-w A 1 it\A' V -■ 7 iu . X■'•/" V. - X X 'k- / / > I ̂ ̂ A ’ f X ■- '' "'/"A A' '- .A A - - a . ̂ A A ' l ̂ - A < ^ 'f i '-̂ X 't', ) r>A X *A/ " . V , . ., iV . . ’ A X - ^ S f V A - < : V; . A a a a ’4'A ' .-T ' A A .V x A a a ' A A V '' , A .7 ;A>_rix^Af. '/A'~ X ' I■- r ^ t . x x x ; 7̂ A ^ a L: 7̂^■ x A rA 'A .

r ̂> ' -X' A A > V - , „ vy

7 3xaAt A-, x -aA -,/J

'■ ' ' / ^';/ >X/ / '" ’ '‘i- J,^7 ' - •■ < *c.'y^ iy^ ,' % ' ^ ' ’V - ' - X'v' X., X '- .X 7 - A 'A A / X 7 < ' A X ' X X x X / t X j 7 , . - X y 'A V ’̂ y t X *X/A'A^' 7^-17 ? V , ' - ' -- . ̂ ' V L X ^ X , A* A]'" A i ^ ’ Ax^ AY>A’'A' s' '-'̂ A 3 \aa

Z -4 Z1 j . % z i J \ x^'^X'"" P x * ' /A''-''

> 7 i e A : ^ x A 7 x . x x : ^ ' : v : A ' .:7lxx.yA" ^ aX X p : 7- V ' ̂ X X '1®B ■M0' ŷ yX- “ • T • A p./xA A: x: 41, ̂ .A ‘ “' t - . . X X X aA iY'xA"^'

{. A - x x ■■' -̂‘ ' ' '̂ '" A '7

. ' i f A 'A^ >X( A 5 ' ' - V ' 7 : ' - " Y - ' I y Y jY X » iSSY ‘ ' ’ *’ x x X Y ̂ r -,y 7,.)X jf '■'7 \ . X / , j | . , x X ^" "'X-' X , A . x ; r > ^ ' x ^ Y* i'7 A -x X " 'X ' ' ̂ ,A A '-A ?x '

P ■ AX- xf. . . aYXx;^7 '/A^AAi' - A X ’̂ .x . . ix iY A - x v ,X '7 y v\7'7V -VAY ̂ V : 'A 'X y -'XX /-'.pvX ■ "'iyy>rt. *;;? -Ax y'L ̂ ' • ; „ '77-7 7 7 ,,x v . x . _ a . 7 - r x ' X x ...X P .A ...... A " ........ . ..... .....A.,-.......X ...Y.7.A..Y A>^

m

4"7 ,;. :Y '‘x A 7 . 7 . , . i i v < . 7 A 'A ', i - y - K .y < '• -* A( y,i . . ’-iA aX x

y A Y ^ ^ Y t- .X y A A y I '< . a >'

Y '-Y a X ^ X A X / , Ya . - v; A 'Y A - x .- ^ X vX

r . 7 4 - , X V ̂aY'" " iaA X ‘ V j X ' ax4 . 17 1 A V , - x X

■ a x . " x - ; . i J v x J A v p A y A x ; , / 7 7 a : p / x

:;x • .YPaVy xY,.y7,P-;77.A:AYx YYv AYA ‘.x x Y-x / - x a - I

-l iv 'I -' X'i '*, »̂'i ■>

'>• " # ^ v: yaW ;7 - ' , X n-=* ’’-̂ ' >7

' ' * X V r .

I *

XI I #

XXts ' A " 'X "!f'' .' 'X̂ sAX/ A X ̂ " x V 7 ' .^7 P ^ . M ; Y /- ' ; X X - ̂ Ax 't. "'7

X'* A x x A x P -''' ''Y Yx VAy Y'A/ X x' v -‘X/,-^'rA- AA# ‘

X p A ‘ A | , 7 i/'x ; xy AAA ̂ x’ X % I : P'S'XAP A , A ? AvX’- 'A 'VA" YY X :A a Al x > x ' y A " - X ' . x ;

/Y.AA a ’’y \Yr' 3 f A xx 7A , ''X'-ĵ fyf y ̂ x /iX A 'X x .X ,.

A, .̂ ■YA,.x .1, I,, AA,«r7iA.|. XX xX/yAAAAY- A ,.YAA, .,-7 ...';. 'A, .>...7..,,.:

;MY

, 1 \ ' - , x 7̂. . . ; A v M . M X‘Y . A A a ’’ y \Yr' ^A A X x y Y ', ''X\2̂ f y f y -" 7 . s«y A#X7 AA- APY.I r • A-.pYAX . y 7,. # ^ .,7 7 .,^

’; - Y-^: A Y;,x x a : AYy^lAfYiM^ /y AY'M pJtYAXM ^'Y

■'■'•y. S-S77 y - " y f . y ^ 7 , 3 r . , v, . : ,7 '. '-A 7 " - .x . \

7 ,7 7 5 7 7 . 7 . 7 7 , ,4 .7 7 7 ;- 7 ,x 7 ' 7 ’.7v X 3 . y ; x 7 7 >

. ,' . X ̂ y ’ X ; 7/ -X/ X̂rt-.«'1,,,X'Y * ̂ "-, ' ^ • -̂AAÂ y * ^ y .7 'v -, .. X"., ̂ ~''’ X .a i MS.y -j. , ' j,'4 ̂ i 7>-, 5- .4; ̂ ^ X > j -y. -. '

I , ^ 7 -7̂ i 3 -.'M̂i

/X' X — X