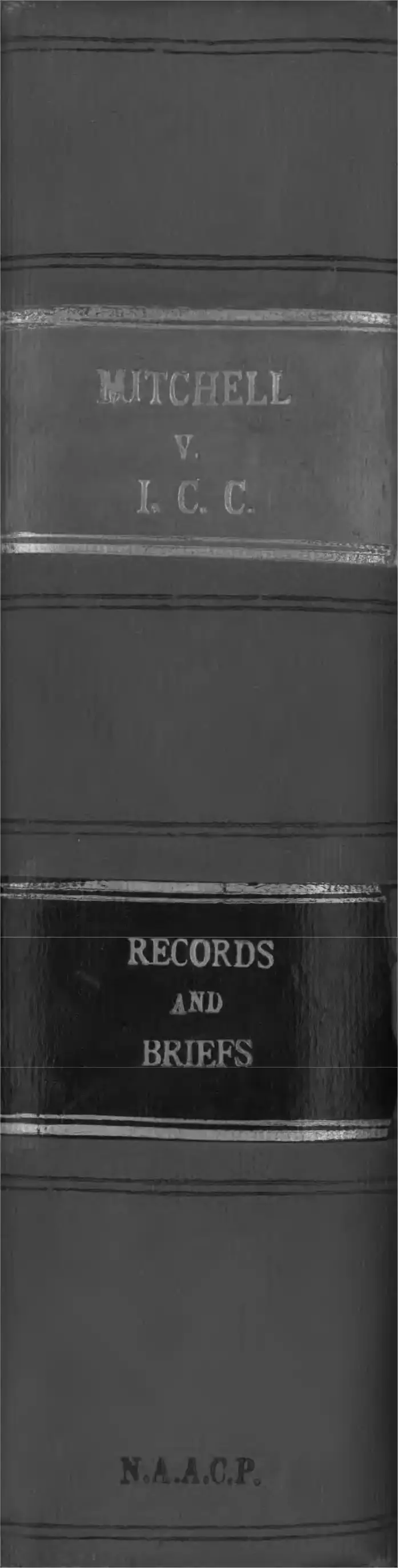

Mitchell v. Illinois Central Railway Company Records and Briefs

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1941

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mitchell v. Illinois Central Railway Company Records and Briefs, 1941. 6b6ef565-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/463288ba-5e76-4f52-a09d-82e083637b17/mitchell-v-illinois-central-railway-company-records-and-briefs. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

RECORDS

INI)

BRIEFS

*\ ‘ k

I

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F or the N orthern D istrict of I llinois

E astern D ivision i

ARTHUR W . MITCHELL,

Plaintiff,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

FRANK 0. LOWDEN, JAMES E. GORMAN, and

JOSEPH B. FLEMING, Trustees of the Estate

of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Rail

way Company, a corporation;

ILLINOIS CENTRAL R AILW AY COMPANY,

a corporation; and

PULLMAN COMPANY, a corporation,

K

In Equity

Defendants.

P E T I T I O N .

RICHARD E. WESTBROOKS,

3000 South State Street,

Chicago, Illinois

and

ARTHUR W. MITCHELL, Pro Se,

417 East 47th Street,

Chicago, Illinois,

Attorneys for Plaintiff.

P R I N T E D B Y C H I C A G O L A W P R I N T I N G C O .

'

.

I N D E X .

PAGE

Excerpts from complaint filed before Interstate Com

mission ......................................................................... 3-9

Excerpts from the answer of the Illinois Central.... 9

Excerpts from the answer of the Rock Island........... 9

Excerpts from the answer of the Pullman Company 10

Exhibit “ A ” proposed report of Examiner, Wm.

A. Disgne ..................................................................... 12-21

Exhibit “ B ” report of Commission............................ 22-40

Order of Commission dismissing the complaint....... 40-41

Exhibit “ C” order of Commission denying petition

for rehearing and reargument ................................ 41-42

IN THE

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F ob the N orthern D istrict of I llinois

E astern D ivision .

ARTHUR W . MITCHELL,

V 8.

Plaintiff,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

FR AN K O. LOWDEN, JAM ES E. GORMAN, and In E(.uity

JOSEPH B. FLEM ING, Trustees of the Estate of

the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railway

Company, a corporation;

ILLINOIS CENTRAL R A IL W A Y COMPANY,

a corporation; and

PULLM AN COMPANY, a corporation,

Defendants.

P E T I T I O N .

To the Honorable Judges of the District Court of the United

States for the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Divi

sion;

Your petitioner, Arthur W. Mitchell, the plaintiff herein,

presents this his petition against the United States of

America, Frank 0. Lowden, Janies E. Gorman, and Joseph

B. Fleming, trustees of the estate of the Chicago, Rock

Island & Pacific Railway Company, a corporation, Illinois

Central Railway Company, a corporation and Pullman

Company, a corporation and thereupon petitioner respect

fully states:

2

I.

That he is now and was at the time of the grievances, in

juries and damages to him sustained by the acts, as herein

after alleged, of certain of the defendants, a native born

citizen of the United States of America, a resident of Chi

cago, County of Cook and State of Illinois; is a duly

licensed and practicing attorney-at-law, and is now and

was a Representative in Congress of the First Congres

sional District of the said State of Illinois.

II.

The defendants and each of them, excepting the United

States of America, are duly organized and incorporated,

severally, as railroad and transportation corporations under

the laws of the State of Illinois, with principal operating

offices at Chicago, Illinois, and within the jurisdiction of

this Honorable Court.

III.

Each of the defendant corporations, mentioned in Para

graph II hereof, is a common carrier engaged in the trans

portation of persons and property by railroad, in interstate

commerce, between points inter alia, in the States of Illi

nois, Tennessee and Arkansas as well as points in various

other states of the United States and as such common car

riers were so engaged at the time of the grievances here

inafter stated as having been suffered by the plaintiff from

the acts of the said defendants; that at the time of the said

grievances last mentioned and for many years prior thereto

as well as subsequently thereafter, continuously to the

present time, the said defendants were engaged in inter

state commerce and are subject to the provisions of the

Interstate Commerce Act and its supplements.

3

The within suit is brought to set aside and annul an order

of the Interstate Commerce Commission, other than for

the payment of money, pursuant to the provisions of the

Act of February 4, 1887, and all amendments and supple

ments thereto, known as the Interstate Commerce Act, the

laws of the United States designated as the Judicial Code

and Judiciary and under the general equity jurisdiction

of this court.

IV.

V.

Defendant, United States of America, is made a party

defendant to this suit as directed by the Congress of the

United States (28 U. S. C. A. Sec. 41, subsection 28; secs.

43-48.)

VI.

The facts and circumstances leading to the order of the

Interstate Commerce Commission herein sought to be set

aside and annulled, are as follows:

On or about, to-wit: September 2, 1937 the plaintiff

duly filed his written complaint with the Interstate

Commerce Commission charging the defendant cor

porations with the doing of certain acts as alleged in

the said complaint, which said acts the plaintiff

charged, were in violation of the Interstate Commerce

Act and the Fourteenth Amendment of the United

States Constitution.

The complaint filed by the plaintiff was duly verified and

in substance is as follows:

II.

That the defendants, and each of them, are common

carriers engaged in the transportation of passengers

4

and property, wholly by railroad, between Chicago,

Illinois; and points in the State of Arkansas, particu

larly the city of Hot Springs, Arkansas; as well as

points in various other states of the United States, in

eluding the State of Tennessee; and as such common

carriers are subject to the provisions of the Interstate

Commerce Act.

m.

That the defendants, and each of them, in violation

of Section 1 of the Interstate Commerce Act, Clause 5

thereof, on April 20, 1937, did make and receive a

charge for services rendered and to be rendered in

connection with the transportation of the complainant

from Chicago, Illinois, to Hot Springs, Arkansas, which

was unjust, unreasonable and unlawful; in this, that

complainant on said April 20, 1937, did purchase in

Chicago, Illinois, a first-class round-trip ticket to and

from Hot Springs, Arkansas, over the defendant lines,

and did pay therefor the rates demanded and received

of first class passengers for first class accommoda

tions ; yet defendants failed to furnish complainant

first class accommodations and instead thereof, fur

nished him with second class accommodations over his

protest; which said action of the defendants in charg

ing for and receiving the fare for first class accom

modations and failing to provide same; providing in

lieu thereof, second class accommodations, was unjust,

unreasonable and unlawful, in violation of Section 1,

Clause 5, of the Interstate Commerce Act.

IV.

That the defendants, and each of them, in violation

of Section 2 of the Interstate Commerce Act, on the

date aforesaid, did directly and indirectly charge, de

mand, collect, and receive from this complainant a

greater compensation for service rendered in trans

porting him as a passenger, than was charged, de

manded, collected and received from other persons

(whose names are to complainant unknown) for doing

5

for them a like and contemporaneous service, and did

thereby unjustly discriminate against complainant; in

this, that the defendants did charge this complainant

and received from him the price of first class accommo

dations; yet furnished to him second class accommo

dations, while furnishing first class accommodations

to all others who had purchased first class tickets for

first class accommodations; and such action of the de

fendants did thereby unjustly discriminate against

complainant in violation of Section 2 of the Interstate

Commerce Act.

V.

That the defendants, and each of them, in violation

of Section 3, Clause 1 of the Interstate Commerce Act,

on the date aforesaid, did give undue and unreason

able preference and advantage to certain white per

sons (whose names are to this complainant unknown)

in respect to transporting them from Chicago to Hot

Springs aforesaid; and did subject this complainant

to undue and unreasonable prejudice and disadvantage

in respect to transporting him as aforesaid; in this,

that the aforesaid white persons holding first class

tickets similar identically to the first class ticket held

by this complainant, were transported in a first class

car, said car being equipped with clean towels, clean

washbowls, comfortable seats with upholstered backs

and foot rests; clean smoking rooms, lounging rooms,

observation space, writing desks; writing paper, pen

and ink, magazines and other reading periodicals, reg

ular and efficient porter service, pressing and shoe

shining service, stenographic service, manicuring and

barber shop service, bath service, valet service, radio,

soap of high quality, facilities for serving meals in the

car or the option of having meals in the dining car;

clean toilet facilities with running hot and cold water,

and water for flushing purposes with disinfectant, all

free of charge to first class passengers, and many other

services too numerous to mention or to particularize

more definitely; while this complainant, notwithstand

ing the fact that he possessed a first class ticket en-

6

titling him to ride in a first class car possessing each

and every one of the last named facilities, was com

pelled by the defendants by and through their agents,

servants, and employees and over protest of this com

plainant, to ride in a second class car which possessed

none of the aforementioned facilities but on the con

trary said second class car did not contain clean towels,

nor clean washbowls; nor compartments, berths, sec

tions, drawingrooms, smoking rooms, lounging rooms,

observation space, writing desks, paper, pen, ink, mag

azines, and other reading periodicals; nor porter ser

vice, soap, nor facilities for meals being served in said

car; nor clean toilet facilities with running hot and

cold water for flushing purposes and disinfectant; and

this complainant specifically charges that the second

class car in which he was forced to ride as aforesaid

did not contain the above facilities and did not contain

any one or either of them; but on the contrary the said

second class car was filthy with filthy toilets, and so

remained during the entire time this complainant was

compelled to occupy it, which was for a period of more

than four hours and over a journey of about 160 miles;

beginning at a point just west of Memphis, Tennessee,

and continuing on into Hot Springs, Arkansas.

And in this connection, complainant further states

that the first class car occupied by the aforesaid white

persons holding tickets identically similar to the first

class ticket held by this complainant was large, com

fortable, free from stench and odors, well ventilated,

lighted, and air-conditioned; and always clean and

sanitary; while the second class car which this com

plainant was forced to complete his journey in as out

lined in the preceding paragraph, was divided by par

titions and used jointly for carrying baggage, train

crew, and passengers; that said ear was small, poorly

ventilated, filthy, filled with stench and odors emitting

from the toilet, and otherwise filthy and indescribably

unsanitary.

That said action of defendants in furnishing accom

modations to the aforesaid white persons holding first

7

class tickets which were far superior to the accommo

dations furnished to this complainant on his first class

ticket, was unduly and unreasonably prejudicial to him,

and was unduly and unreasonably preferential to said

white persons to the disadvantage of this complainant,

in violation of Section 3, Clause 1, aforesaid.

VL

That the defendants, claiming to act under authority

of the Arkansas Statute (K irby’s Arkansas Statute,

Sections 6622 to 6632), did force and compel this com

plainant to ride in a second class car, notwithstanding

the fact that complainant held a first class ticket; that

the second class car was the car described in Para

graph Five hereof which by reference is made a part

of this paragraph. That the action of defendants was

based on the fact that this complainant is a Colored

person, and in transporting him in the second class

car referred to, while white persons holding iden

tically similar first class tickets were permitted to

ride in the first class car described in Paragraph Five

of this complaint, which by reference is made a part

hereof, and said practice of the defendants in furnish

ing such unequal accommodations to persons holding

similar first class tickets, under the aforesaid Statute,

causes undue and unreasonable advantage and pref

erence to white persons; and causes undue and unrea

sonable prejudice to this complainant and all other

Colored persons who in the future will use, as inter

state passengers, the lines of the said defendants.

The said unreasonable and undue advantage and

preference to white persons aforesaid; and undue and

unreasonable prejudice to this complainant and all

other Colored persons who in the future will use defen

dant lines, only arises between persons in intrastate

commerce on the one hand and persons in interstate

commerce on the other hand, in this, that said practice

under said law only arises after Colored persons have

entered the State of Arkansas and did not exist while

8

this complainant was traveling in Illinois; that said

law is not intended to and does not operate beyond the

territorial boundaries of said State.

That said action, causing undue and unreasonable

advantage to white persons, and causing undue and

unreasonable prejudice to this complainant, being

based on the State law aforesaid, is in violation of

Section 13, Clause 4, of the Interstate Commerce Act.

VII.

That by reason of the facts stated in the foregoing

paragraph complainant has been subjected to the pay

ment of fares for transportation which were when

exacted and still are unjust and unreasonable in vio

lation of Section 1 of the Interstate Commerce Act;

and said complainant has been unjustly discriminated

against in violation of Section 2 of the Interstate Com

merce Act; that said defendants have been unduly and

unreasonably preferential to some persons while at the

same time being unduly and unreasonably prejudiced

against this complainant in violation of Section 3 of

the Interstate Commerce A ct; that the action of defen

dants in operating under the Arkansas Law causes un

due and unreasonable preference to some persons and

undue and unreasonable prejudice to complainant and

other persons, in violation of Section 13 of the Inter

state Commerce Act, and the Fourteenth Amendment

of the United States Constitution in denying to peti

tioner equal protection of the laws.

W herefore, complainant prays that defendants and

each of them may be required to answer the charges

herein; that after due hearing and investigation an

order be made commanding said defendants and each

of them to cease and desist from the aforesaid viola

tions of said act, and establish and put in force and

apply in future to the transportation of persons be

tween the origin and destination points named in par

agraphs V and VI hereof, in lieu of the services and

facilities named in said paragraphs V and VI, and such

9

other services and facilities as the Commission may

deem reasonable and just; and that such other and fur

ther order or orders be made as the Commission may

consider proper in the premises.”

VII.

The defendant, Frank 0. Lowden, James E. Gorman

and Joseph B. Fleming, trustees of the estate of the Chi

cago, Bock Island and Pacific Bailroad Company, a cor

poration and hereinafter called and referred to as the

“ Bock Island,” filed an answer to the complaint above set

forth, (1) it admits that it was a common carrier engaged

in the transportation of passengers and property by rail

road in interstate commerce on April 20, 1937, (2) it denies

that the facts charged in Paragraph III of the complaint

were unjust, unreasonable or unlawful and in violation of

Section 1, Clause 5 of the Interstate Commerce Act; (3)

it denies the charges contained in Paragraph IV of the

complaint and further denies said acts contained in the

said paragraph violated Section 2 of the Interstate Com

merce Act; (4) it denies each and every allegation con

tained in Paragraphs V-VI of the complaint and denies

that the acts charged in said paragraphs violated Section

3, Clause 1 or Section 13, Clause 4 of the Interstate Com

merce Act; (5) it denies the allegations of Paragraph VII

of the complaint and further denies that the acts charged

in said paragraph violated Sections 1, 2, 3 and 13 of the

Interstate Commerce Act and the Fourteenth Amendment

of the United States Constitution and prayed to be dis

missed.

VIII.

The defendant, Illinois Central Bailroad Company, here

inafter referred to as the Illinois Central by and in its

10

answer filed to the above mentioned complaint, (1) denies

that it owned or operated any line of railroad within the

State of Arkansas; (2) it denies each and every allegation

of Paragraphs III, IV, V, VI and the first paragraph of

Paragraph VII of the complaint; (3) it further denies

that the acts or omissions towards the complaint violated

Sections 1 (5), 2, 3 (1) or 13 (4) of the Interstate Com

merce Act and prayed that the complaint be dismissed

as to it.

IX.

The defendant, the Pullman Company, filed its answer

to the above mentioned complaint, by and in its answer,

(1) it admits the allegations of Paragraph I of the com

plaint; (2) it denies the allegations of Paragraph II of the

complaint in so far as it pertains to this defendant and

states that it is a Sleeping Car Company, subject to the

provisions of the Interstate Commerce Act, and furnishes

sleeping car accommodations to passengers traveling be

tween the points stated in Paragraph II of the complaint,

when such passenger contract with it for such accommoda

tions in accordance with the provisions of its tariffs on

file with the Interstate Commerce Commission; (3) it

denies the allegations of Paragraph 3 of the complaint as

applying to it and states that it furnished equal accommo

dations to the plaintiff, for which the plaintiff had paid

and that it had no contract with the plaintiff for accom

modations between Memphis, Tennessee and Hot Springs,

Arkansas; (4) it denies the allegations of Paragraph IV

of the complaint and refers to Paragraph II of its answer

concerning the sleeping car accommodations; (5) it like

wise denies the allegations of Paragraph V of the com

plaint and states that it did not own or control the inferior

accommodations in the equipment which the plaintiff was

compelled to occupy between Memphis and Hot Springs,

11

and (6) it likewise denies the allegations of Paragraphs

VI and VII of the complaint as relating to the plaintiff

and prays the dismissal of the complaint as to it.

X.

The said complaint was assigned for hearing by the

commission by order dated December 4, 1937, of which due

notice was given to all parties.

XI.

A formal hearing of the complaint was heard before

the commission represented by W. A. Disque, examiner,

on March 7, 1938.

XII.

That on said last mentioned date, evidence, both oral

and documentary, was introduced by the plaintiff and the

defendant, Rock Island. A complete transcript of the evi

dence had and taken before the commission as aforesaid,

is hereby made a part of this petition, by reference thereto,

as though fully set out herein and will be offered on behalf

of the plaintiff on the hearing of this petition.

XIII.

Thereafter, briefs were filed by the plaintiff and by the

defendants, and in due course the examiner’s proposed

report was filed, recommending that the complaint should

be dismissed, which said proposed report is hereto attached

and marked Exhibit “ A ” and made a part hereof, and is

as follows:

12

E x h ib it “ A . ”

“ INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION

No. 27844

A rth u r W . M itchell

v.

C hicago, R ock I sland & P acific R ailw ay Com pany ,

T rustees, et al .

Submitted Decided May 5th, 1938.

Present accommodations for colored passengers travel

ing in Arkansas over the line of The Chicago, Rock

Island and Pacific Railway Company on through

journeys from Chicago, HI., to Hot Springs, Ark.,

found not unjustly discriminatory or unduly preju

dicial. Complaint dismissed.

Arthur TV. Mitchell and Richard E. Westbrooks for

complainant.

Wallace T. Hughes, Daniel Taylor, E. A. Smith,

Robert Mitten, H. J. Deany, Erwin W. Roemer, Charles

S. Williston, and Lowell M. Greenlaw for defendants.

R eport P roposed by W m . A . D isque, E xam iner .

Complainant, a negro resident of Chicago, 111., and a

member of the House of Representatives of the United

States, by complaint filed September 2, 1937, alleges,

in effect, that defendants, in connection with their

purported compliance with an Arkansas statute re

quiring segregation of the races during transportation,

do not provide as desirable accommodations for col-

13

ored as for white passengers traveling in Arkansas

over the line of The Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific

Railway Company at first-class fares from Chicago,

111., to Hot Springs, Ark., and that this results in un

reasonable charges and unjust discrimination against,

and undue prejudice to, colored passengers, in viola

tion of sections 1, 2, 3, and 13 of the Interstate Com

merce Act, and the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. However, the only

relief sought is removal and avoidance in the future

of the alleged discrimination and prejudice in the

furnishing of accommodations. The above-named car

rier will be hereinafter called the Rock Island. It is

the principal defendant.

Docket No. 27844— Sheet 2.

Defendants question our jurisdiction to give the

relief, on the ground that the sections of the act in

voked relate only to rates and charges. They take

the position that the only provisions which give this

Commission power over the furnishing of equipment

and facilities of transportation begin with section 1

(10), which says that the term ‘ car service’ as used

in those provisions ‘ shall include the use, control,

supply, movement, * * * and return of * * * cars * * *

used in the transportation of property * * *.’ (Italics

ours.) However section 3 (1) makes it unlawful ‘ to

subject any particular person * * *, or any particular

description of traffic to any undue or unreasonable

prejudice or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever.’

In view of the conclusion reached the question raised

is not important, but it appears to be set at rest by

Interstate Commerce Commission v. Illinois Central

R. Co., 215 U. S. 452, and Pennsylvania R. Co. v. Clark

Bros. Coal Mining Co., 238 U. S. 456, where the Su

preme Court held that this Commission had jurisdic

tion to deal with discrimination in the distribution of

coal cars.

The complaint mentions but a single incident of

alleged discrimination and prejudice, the one herein-

14

after described in which complainant was involved.

Although there is an allegation that ‘ said practice of

the defendants in furnishing such unequal accommoda

tions * * * causes * * * undue and unreasonable preju

dice to this complainant and all other colored persons

who in the future will use * * * the lines of said de

fendants,’ defendants upon brief urge that the com

plaint is sufficient to raise any issue as to practice, on

the ground that one incident does not amount to a

practice, and move that all testimony that does not

relate to this particular incident be stricken. Plainly,

however, the incident was mentioned as representa

tive of an alleged practice that was expected to con

tinue. The prayer is that an order be entered requir-

Docket No. 27844— Sheet 3.

ing defendants to cease and desist from the alleged

violations of the act and provide lawful accommoda

tions in the future for colored passengers from and

to the points involved. Defendants are taking an

unduly technical position. They have long understood

that a complaint is not to be narrowly construed.

They were well aware of the kind of accommodations

they were furnishing and were not taken by surprise,

but came to the hearing with a full array of witnesses

adequately informed respecting all the facts. They

objected at the hearing to the receipt of any testi

mony not confined to the incident mentioned, but their

objections were overruled by the examiner.

At the hearing complainant moved that the Rock

Island’s answer be stricken, contending that it violated

Rule IV, (d), (e) of the Rules of Practice, because it

did not state fully, completely and with particularity

the nature and grounds of the defense. Paragraph

(e) of the rule deals specifically with answers to

allegations under sections 2 and 3 of the act. How

ever, there is no indication that complainant was put

to any material disadvantage by defendant’s failure

and the matter may be passed, as it calls only for a

reprimand.

15

The case is built mainly on an unpleasant experi

ence complainant had a little over a year ago. On

the evening of April 20, 1937, he left Chicago for Hot

Springs, over the lines of the Illinois Central Railroad

Company to Memphis, Tenn., and the Rock Island

beyond, traveling on a first-class round-trip ticket he

had purchased from the initial carrier’s ticket agent

in Chicago. He had requested a bedroom on defend

ants’ through Chicago-Hot Springs Pullman sleeping

car, but none being available, the ticket agent provided

him with a compartment as far as Memphis in the

sleeper destined to New Orleans, La. Just before the

train reached Memphis, on the morning after leaving

Chicago, he had a Pullman porter transfer him, to-

Dochet No. 27844—Sheet 4.

gether with his hand baggage and other personal

effects, to the Chicago-Hot Springs sleeper then on

the same train, but which was to leave Memphis at

8:30 a.m., on Rock Island train no. 45, and reach Hot

Springs, 193 miles west, at 1:05 p.m., the same day.

Plenty of space was available and the porter assigned

him a particular seat in that car, for which he was to

pay the established fare, 90 cents. Shortly after

leaving Memphis and crossing the Mississippi River

into Arkansas the train conductor took up the Mem

phis-Hot Springs portion of his ticket, but refused to

accept payment for the Pullman seat from Memphis,

and in accordance with custom, compelled him, over

his protest and finally under threat of arrest, to move

into the so-called Jim Crow car, or colored coach, in

compliance with an Arkansas statute requiring segre

gation of colored from white persons by the use of

cars or sections thereof providing ‘ equal, but separate

and sufficient accommodations,’ for both races. Com

plainant’s baggage and other personal effects were

allowed to go on to destination in the Pullman car.

Later, the conductor returned the portion of the ticket

he had taken up and correctly advised complainant

that he could get a refund on the basis of the second-

16

class fare from Memphis, which was one cent less per

mile than the first class fare. The refund was never

claimed from defendants and is not here sought, but

defendants stand ready to make it upon application.

Complainant has an action at law pending against the

defendants in the Circuit Court of Cook County, 111.,

for damages incident to his transfer.

The Pullman car contained 10 sections of berths and

two compartment-drawing rooms. The use of one of

the drawing rooms would have amounted to segrega

tion under the State law and ordinarily such accom

modations are available. Whether the 90-cent seat

fare would have been applicable is not clear, but both

drawing rooms were occupied by white passengers.

Docket No. 27844— Sheet 5.

The car was of modern design and had all the usual

facilities and conveniences found in standard sleeping

cars. It contained a smoking room for men and a

dressing room for women. It was air conditioned, had

hot and cold running water, tables, carpet, mirrors,

wash basins with good soap, clean linen towels, and

separate flushable toilets for men and women. It

was in excellent condition throughout. First-class

white passengers had, in addition to the Pullman

sleeper, the exclusive use of the train’s only dining

car and only observation-parlor car, the latter having

somewhat the same accommodations for day use as the

Pullman car and, in addition, a wi’iting desk and

perhaps a radio. The white passengers could range

throughout the portion of the train behind the colored

coach, but colored passengers were confined to that

car.

The colored coach, carried next to the baggage car,

was the first passenger car behind the locomotive.

Behind it came a white day coach, the dining car, the

sleeper and finally the observation-parlor car, all

being Rock Island equipment, except the sleeper. The

colored coach, though of standard size and steel con

struction, was an old combination affair. It was

17

divided by partitions into three main parts, one for

colored smokers, one for white smokers, and one, in

the middle, for colored men and women, hut primarily

the latter, and known as the women’s section, each

section having seats for about 20 passengers. Com

plainant sat in the women’s section. The car was

poorly ventilated and not air conditioned. The up

holstery was of leather. There was a toilet in each

section, but only the one in the women’s section was

equipped for flushing and it was for the exclusive use

of the colored women. The car was without wash

basins, soap, towels or running water, except in the

Avomen’s section. According to complainant the car

was filthy and. foul smelling, but the testimony of

defendants, as we shall later see, is to the contrary.

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 6.

The car contained, besides complainant, several other

colored passengers, including women. Two pairs of

seats in the colored men’s section were used as an

office by the conductor and the flagman, who were

white. These conditions had prevailed for at least

25 years.

The above facts are gathered principally from com

plainant’s testimony, but several other colored per

sons, who had traveled from Memphis to Hot Springs

over the Rock Island at times during the above-men

tioned period, gave similar testimony as to the condi

tion of the cars in which they rode. They also told

of colored coaches between these points that had

common toilets for men and women and of the absence

of carpets and foot rests, while much more desirable

accommodations were provided for white passengers

traveling in coaches. This treatment of the colored

race cannot be too strongly condemned.

Defendant’s witnesses, namely the conductor and

flagman of the train and the superintendent who had

charge of getting the equipment ready at Memphis,

testified that they noticed no dirt, filth or obnoxious

odors in the car; that it was as clean as it could be

18

made; that in accordance with the usual practice it

was thoroughly cleaned, disinfected, equipped with

newly laundered seat and seat-back linen covers, and

inspected at Memphis before it was put into the train.

Each section of the car contained a cooler of ice water

and a 12-inch electric fan. Incidentally, the Eock

Island keeps eight men busy preparing equipment for

13 or 14 trains per day.

Since the early part of July, 1937, the Eock Island

has been running a colored coach between Memphis

and Hot Springs that is entirely modern. It is of

all-steel construction, with six-wheel trucks. It is

divided by a partition into two sections, one for col

ored and the other for white passengers. It has

comfortable seats with plush upholstery and linen seat

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 7.

covers, linoleum floor covering, air conditioning, elec

tric light, and electric fans. In each section there are

wash basins, running hot and cold water, free paper

towels and drinking cups, and separate flush toilets

for men and women. There is no smoker section, as

smoking nowadays is generally permitted in all coaches

and sections thereof, and even in some instances, or

to some extent, in Pullman cars. The present colored

coach is as fully desirable in all its appointments as

the coach used by the white passengers traveling at

second-class fares. One of the complainant’s witnesses

testified that as late as September, 1937, he found

conditions in the colored coach between Memphis and

Hot Springs ‘ very bad,’ but evidently he was not

riding the train that carried the new car, as he said

the men and women used the same toilet.

The present colored coach takes care of colored

second-class passengers, but there is no Pullman, din

ing or observation-parlor car for colored first-class

passengers. Only about one negro to 20 white pas

sengers rides this train from and to points on the

line between Memphis and Hot Springs and there is

hardly ever a demand from a colored passenger for

19

Pullman accommodations; the conductor recalled but

10 or 12 in the past 32 years of his service on the

train. What demand there may have been at ticket

offices does not appear.

Various previous proceedings akin to this one are

Council v. Western & A. R. Co., 1 I.C.C. 339; 1 I.C.R.

638; Heard v. Georgia R. Co., 1 I.C.C. 428; 1 I.C.R.

719; Edwards v. Nashville C. & St. L. Ry. Co., 12 I.C.C.

247, and Crosby v. St. Louis-S. F. Ry. Co., 112 I.C.C.

239. In the first four proceedings affirmative findings

and orders were entered requiring the removal of

unjust discrimination and undue prejudice to colored

passengers, but not in the last one. Each rested on

its own facts. None presented the same situation as

the instant proceeding.

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 8.

For the purposes of this proceeding complainant

accepts segregation under the Arkansas statute, but

urges that defendants, to remove and avoid unjust

discrimination and undue prejudice, are bound to

provide the same equipment and accommodations for

colored passengers as for white passengers. In other

words, he says that if defendants are to continue the

Pullman sleeper, the dining car and the observation-

parlor car for white passengers, they must provide

similar facilities, three extra cars, for colored passen

gers paying first-class fares plus the additional charges

provided by tariff for seat space.

Complainant urges that collection of the first-class

fare, notwithstanding the fact that second-class ac

commodations were furnished him, was violative of

sections 1, 2, 3 and 6 of the Interstate Commerce A ct;

also of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion, on the ground that he was deprived of money

without due process of law and denied equal protec

tion of the laws. It is sufficient to say that a first-class

ticket was furnished and charged for because com

plainant wanted it, and that after it developed that the

first-class accommodations west of Memphis were all

20

taken by other passengers defendants offered to re

fund the difference. Moreover, as already stated,

complainant is here seeking no relief from the charges

paid.

Complainant urges that the Rock Island, having

received from him the first-class fare but having failed

to furnish first-class accommodations west of Mem

phis, violated section 13(4) of the act. That provision

relates to intrastate fares that are unjustly discrimina

tory or unduly prejudicial in their relation to inter

state fares. No intrastate fares are here involved.

There was no break in complainant’s journey at the

Tennessee-Arkansas State line. He was engaged in

through interstate travel from Chicago to Hot Springs.

Moreover, as said in the next preceding paragraph,

Docket No. 27844— Sheet 9.

complainant was furnished a first-class ticket because

he asked for it, and refund awaits him.

Regardless of what finding may be made respecting

the Rock Island, the Illinois Central asks that the

complaint be dismissed as to it. There is no showing

that colored passengers are treated differently from

white passengers on their journeys from Chicago to

Memphis and apparently that road is in no way

chargeable with discrimination, even though it par

ticipates in the through transportation under joint

fares and other arrangements. This carrier is a

proper, but perhaps not necessary party. It was

named as a defendant apparently out of abundance

of caution, because it participated in the movement.

The Pullman Company also asks dismissal, regard

less of what may be done as to the Rock Island, con

tending that it is not chargeable with discrimination

because it provides accommodations in the form of

drawing rooms, which if not already occupied or

reserved for some one else, are available for colored

passengers west of Memphis. Apparently there is no

discrimination on its part, if the 90-cent seat fare is

applicable.

21

The present colored coach meets the requirements

of the law. As there is comparatively little colored

traffic and not likely to be such demand for Pullman,

dining and observation-parlor car accommodations by

colored passengers as to warrant the running of any

extra cars, the discrimination and prejudice is plainly

not unjust or undue. Only differences in treatment

that are unjust or undue are unlawful and within the

power of this Commission to condemn, remove and

prevent.

The complaint should be dismissed.”

XIV.

The plaintiff on or about May 25, 1938, duly filed excep

tions to the said proposed report in which exceptions,

among other things the plaintiff contended that his con

stitutional rights under the 14th Amendment of the United

States had been violated.

XV.

The defendant, Rock Island filed a reply to the excep

tions, on or about June 4, 1938.

XVI.

On or about July 6, 1938, the cause came on before the

full Commission for oral argument.

XVII.

On or about November 7, 1938, the Commission filed its

report and order thereon dismissing the complaint. The

said report was dissented to by five members of the said

Commission.

22

XVIII.

The said report, including the dissenting expressions and

the order of the Commission are hereto attached and

marked Exhibit B and made a part hereof and is as fol

lows :

E xh ibit B.

INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION

Reed. 11/28/38

No. 27844

A rthur W . M itchell

v.

C hicago, R ock I sland & P acific R ailw ay Company

ET AL.

Submitted July 6, 1938. Decided November 7, 1938.

Present accommodations for colored passengers trav

eling in Arkansas over the line of The Chicago,

Rock Island and Pacific Railway Company on

through journeys from Chicago, 111., to Hot Springs,

Ark., found not unjustly discriminatory or unduly

prejudicial. Complaint dismissed.

Arthur W. Mitchell and Richard E. Westbrooks for

complainant.

Wallace T. Hughes, Daniel Taylor, E. A. Smith,

Robert Mitten, H. J. Deany, Erwin W . Roemer, Charles

S. Williston, and Lowell M. Greenlaw for defendants.

23

R eport of the C ommission

By th e Commission :

Exceptions to the examiner’s report were filed by

complainant, to which the trustees of The Chicago,

Rock Island and Pacific Railway Company, herein

after called the Rock Island, replied. The proceeding

was orally argued.

Complainant, a negro resident of Chicago, 111., and

a member of the House of Representatives of the

United States, by complaint filed September 2, 1937,

alleges, in effect, that defendants, in connection with

their purported compliance with an Arkansas stat

ute requiring segregation of the races during trans

portation, do not provide as desirable accommodations

for colored as for white passengers traveling in Ar

kansas over the line of the Rock Island at first-class

fares from Chicago, 111., to Hot Springs, Ark., and

that this results in unreasonable charges and unjust

discrimination against, and undue prejudice to, col

ored passengers, in violation of sections 1, 2, 3, and

13 of the Interstate Commerce Act, and the four

teenth amendment to the Constitution of the United

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 2.

States, guaranteeing due process of law and equal

protection of the laws. However, the only relief

sought is removal and avoidance in the future of

the alleged discrimination and prejudice in the fur

nishing of accommodations.

Defendants question our jurisdiction to give the

relief sought, on the ground that the sections of the

act invoked relate only to rates and charges. They

take the position that the only provisions which give

this Commission power over the furnishing of equip

ment and facilities of transportation begin with sec

tion 1 (10), which says that the term “ car service”

as used in those provisions “ shall include the use,

control, supply, movement, * * * and return of # * #

24

cars * * # used in the transportation of property

* * (Italics onrs) However section 3 (1) makes

it unlawful “ to subject any particular person * * #,

or any particular description of traffic to any undue

or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any

respect whatsoever.” In view of the conclusion

reached the question raised is not important, but it

appears to be set at rest by Interstate Commerce

Commission v. Illinois Central R. Co., 215 U. S. 452,

and Pennsylvania R. Co. v. Clark Bros. Coal Mining

Co., 238 U. S. 456.

The complaint mentions but a single incident of

alleged discrimination and prejudice, the one herein

after described in which complainant was involved.

Although there is an allegation that “ said practice

of the defendants in furnishing such unequal accom

modations * * * causes # * * undue and unreasonable

prejudice to this complainant and all other colored

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 3.

persons who in the future will use * * # the lines of

said defendants,” defendants upon brief urge that

the complaint is insufficient to raise any issue as to

practice, on the ground that one incident does not

amount to a practice, and they move that all testi

mony that does not relate to this particular incident

be stricken. Plainly, however, the incident was men

tioned as representative of an alleged practice that

was expected to continue. The prayer is that we

require defendants to cease and desist from the al

leged violations of the act and to provide lawful

accommodations in the future for colored passengers

from and to the points involved. Defendants are tak

ing an unduly technical position. They have long

understood that a complaint is not to be narrowly

construed. They were well aware of the kind of

accommodations they were furnishing and were not

taken by surprise, but came to the hearing with wit

nesses adequately informed respecting all the facts.

They objected at the hearing to the receipt of any

25

testimony not confined to the incident mentioned, but

their objections were properly overruled by the ex

aminer.

At the hearing, complainant moved that the Rock

Island’s answer be stricken, contending that it vio

lated rule IV (d), (e) of the Rules of Practice, be

cause it did not state fully, completely, and with

particularity the nature and grounds of the defense

nor deny specifically and in detail each material alle

gation of the complaint. However, there is no indi

cation that complainant was put to any material

disadvantage by defendant’s failure; and striking

the answer would avail nothing, for the proceeding

would nevertheless be at issue. Rule IV (b) and

Smokeless Fuel Co. v. Norfolk & W. Ry. Co., 85 I.C.C.

395.

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 4.

The case is built mainly on an unpleasant experience

complainant had about 18 months ago. On the eve

ning of April 20,1937, he left Chicago for Hot Springs,

over the lines of the Illinois Central Railroad Com

pany to Memphis, Tenn., and the Rock Island beyond,

traveling on a round-trip ticket he had purchased

at 3 cents per mile from the initial carrier’s ticket

agent in Chicago. He had requested a bedroom on

defendants’ through Chicago-Hot Springs Pullman

sleeping car, but none being available, the ticket agent

provided him with a compartment as far as Memphis

in the sleeper destined to New Orleans, La. Just

before the train reached Memphis, on the morning

after leaving Chicago, he had a Pullman porter trans

fer him, together with his hand baggage and other

personal effects, to the Chicago-Hot Springs sleeper

then on the same train, but which was to leave Mem

phis at 8:30 a.m., on Rock Island train no. 45, and

reach Hot Springs, 193 miles west, at 1 :05 p.m., the

same day. Space was available and the porter assigned

him a particular seat in that car, for Avhich he was

to pay the established fare, 90 cents. Shortly after

leaving Memphis and crossing the Mississippi River

26

into Arkansas the train conductor took up the Mem

phis-Hot Springs portion of his ticket, but refused

to accept payment for the Pullman seat from Memphis,

and in accordance with custom, compelled him, over

his protest and finally under threat of arrest, to move

into the car provided for colored passengers, in pur

ported compliance with an Arkansas statute requiring

segregation of colored from white persons by the use

of cars or partitioned sections thereof providing

“ equal, but separate and sufficient accommodations” ,

for both races. Complainant’s baggage and other per

sonal effects were allowed to go on to destination in

Docket No. 27844— Sheet 5.

the Pullman car. Later the conductor returned the

portion of the ticket he had taken up and correctly

advised complainant that he could get a refund on

the basis of the coach fare of 2 cents per mile from

Memphis. The refund was never claimed from de

fendants and is not here sought, but defendants stand

ready to make it upon application. Complainant has

an action at law pending against defendants in the

Circuit Court of Cook County, 111., for damages in

cident to this transfer.

The Pullman car contained 10 sections of berths

and 2 compartment-drawing rooms. The use of one

of the drawing rooms would have amounted to segre

gation under the State law and ordinarily such ac

commodations are available to colored passengers

upon demand, the 90-cent seat fare being applicable. Oc

casionally they are used by colored passengers, but

in this instance both drawing rooms were already

occupied by white passengers. The car was of modern

design and had all the usual facilities and conveniences

found in standard sleeping cars. It contained a smok

ing room for men and a dressing room for women.

It was air conditioned, had hot and cold running water,

tables, carpet, mirrors, wash basins with good soap,

clean linen towels, and separate flushable toilets for

men and women. It was in excellent condition through

27

out. First-class white passengers had, in addition to

the Pullman sleeper, the exclusive use of the train’s

only dining car and only observation-parlor car, the

latter having somewhat the same accommodations for

day use as the Pullman car and, in addition, a writing

desk and perhaps a radio.

The coach for colored passengers was in the rear

of the baggage car. Behind it were a day coach for

white passengers, the dining car, the sleeper and, fin-

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 6.

ally, the observation-parlor car, all being Rock Island

equipment, except the sleeper. The colored-passenger

coach, though of standard size and steel construction,

was an old combination affair, not air conditioned.

It was divided by partitions into three main parts,

one for colored smokers, one for white smokers, and

one, in the center, for colored men and women, but

primarily the latter and known as the women’s sec

tion, each section having seats for about 20 passengers.

Complainant sat in the women’s section. There was

a toilet in each section, but only the one in the women’s

section was equipped for flushing and it was for the

exclusive use of the colored women. The car was

without wash basins, soap, towels, or running water,

except in the women’s section. According to com

plainant, the car was filthy and foul smelling, but the

testimony of defendants, as we shall later see, is to

the contrary. The car contained, besides complain

ant, several other colored passengers, including women.

Two pairs of seats in the colored men’s section were

used as an office by the conductor and the flag-man,

who were white. These conditions had prevailed for

at least 25 years.

The above facts are gathered principally from com

plainant’s testimony, but several other colored per

sons, who had traveled from Memphis to Hot Springs

over the Rock Island at times during the above-men

tioned period, gave similar testimony as to the con

2 8

dition of the cars in which they rode. They also told

of colored coaches between these points that had com

mon toilets for men and women and of the absence

of carpets and foot rests, while much more desirable

accommodations were provided for white passengers

traveling in coaches.

Docket No. 27844— Sheet 7.

Defendant’s witnesses, namely the conductor and

flagman of the train and the superintendent who had

charge of cleaning the equipment at Memphis, tes

tified that they noticed no dirt, filth, or obnoxious

odors in the car; that in accordance with the usual

practice it was thoroughly cleaned, disinfected,

equipped with newly laundered seat and seat-hack linen

covers, and inspected at Memphis before being put

into the train. Each section of the car contained a

cooler of ice water and a 12-inch electric fan. Inci

dentally, the Rock Island employs eight men at Mem

phis preparing equipment for 13 or 14 trains per day.

Since the early part of July, 1937, when the coach

above described was taken out of service, the Rock

Island has operated a modern combination coach be

tween Memphis and Hot Springs. It is of all-steel

construction, with six-wheel trucks. It is divided by

a partition into two sections, one for colored and the

other for white passengers. It has comfortable seats,

linoleum floor covering, and is air conditioned. In

each section there are wash basins, running hot and

cold water, free paper towels and drinking cups, and

separate flush toilets for men and women. There is

no smoker section, as smoking nowadays is generally

permitted in all coaches and sections thereof, and

even in some instances, or to some extent, in Pullman

cars. The combination coach is as fully desirable in

all its appointments as the coach used entirely by

white passengers traveling at second-class fares. One

of the complainant’s witnesses testified that as late

as September, 1937, he found conditions in the colored-

passenger coach between Memphis and Hot Springs

29

“ very bad” , but evidently he was not riding the train

that carried the new car ...................... same toilet.

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 8.

Only about 1 negro to 20 white passengers rides

this train from and to points on the line between

Memphis and Hot Springs, and there is hardly ever

a demand from a colored passenger, for Pullman

accommodations; the conductor recalled but 10 or 12

instances, in the past 32 years of his service on the

train, wherein colored passengers who had entered

Pullman cars were required by him to move into the

colored-passenger coach. He estimated that the de

mand for Pullman accommodations did not amount

to one per year. What demand there may have been

at ticket offices does not appear.

The present coach properly takes care of colored

second-class passengers, and the drawing rooms and

compartments in the sleeper provide proper Pullman

accommodations for colored first-class passengers, but

there are no dining-car nor observation-parlor car

accommodations for the latter and they can not law

fully range through the train.

Various previous proceedings akin to this are Coun-

cill v. Western & A. R. Co., 1 I. C. C. 339; 1 I. C. R.

638; Heard v. Georgia R. Co., 1 I. C. C. 428; 1 I. C. R.

719; Edivards v. Nashville, C. & St. L. Co., 12 I. C. C.

247; and Crosby v. St. Louis-S. F. Ry. Co., 112 I.

C. C. 239. In the first four proceedings affirmative

findings and orders were entered requiring the re

moval of unjust discrimination and undue prejudice

to colored passengers, but not in the last cited case.

Each rested on its own facts. None presented the

same situation as the instant proceeding.

Several decisions of the Supreme Court are re

ferred to. In Louisville, N. 0. <& T. R. Co. v. Missis

sippi, 133 U. S. 587, and Chesapeake < f i 0. Ry. Co. v.

Kentucky, 179 U. S. 388, statutes of the States of Mis

sissippi and Kentucky requiring segregation of colored

30

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 9.

passengers in intrastate commerce were upheld as

not repugnant to the commerce clause of the Consti

tution. The State courts, at least for the purpose

of limiting the constitutional question, had held that

the statutes applied only intrastate, and the question

of whether they were constitutional, so far as inter

state traffic was concerned was not decided. In Chiles

v. Chesapeake £ 0. Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71, dealing with

coach passengers, the Supreme Court held that in a

southern State a railroad has the right, by the estab

lishment of appropriate rules and regulations, to re

quire segregation, intrastate and interstate, aside from

any statutory requirements, provided substantially

the same accommodations are furnished for the two

races. It said that railroad regulations respecting

this matter were subject to the same tests of reason

ableness as those enacted by legislative authority and

that rules and regulations induced by the general

sentiment of the community for which they are made

and upon which they operate are not unreasonable.

In McCabe v. Atchison, T. £ S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S.

151, several negroes attacked, before it became ef

fective, a statute of the State of Oklahoma requiring

segregation, on the ground that it violated the four

teenth amendment. They sought to enjoin the carrier

defendant therein from complying with its terms, but

no basis was shown for equitable relief and the de

cree of the lower court dismissing the bill Avas affirmed.

In South Covington £ C. Street Ry. Co. v. Kentucky,

252 U. S. 399, the Supreme Court held that the Ken

tucky segregation statute, as applicable intrastate to

an interurban electric carrier, which also operated

principally interstate, was not an unconstitutional in

terference with interstate commerce.

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 10.

Complainant urges that defendants, to remove and

avoid unjust discrimination and undue prejudice, are

bound to provide the same equipment and accommo-

31

dations for colored passengers as for white passengers.

In other words, he says, that if defendants are to

continue all the present first-class accommodations

for white passengers, they must provide similar ac

commodations for colored passengers on the same

basis of charge. He understands that it is for defend

ants to determine whether this equality of treatment

should be accomplished by the running of extra cars

solely for colored passengers or by partitions in the

cars now operated. The statute sets up two distinct

groups of passengers, and the question for our de

termination is whether the circumstances and condi

tions surrounding these respective kinds of traffic are

so substantially different as to justify the difference

in treatment here alleged to be unlawful.

Complainant contends that the extent of the demand

for first-class accommodations for colored passengers

has no bearing on the question presented. He urges

that McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co., supra, is

to the effect that a constitutional right is personal

and that lack of volume of colored traffic or limited

demand by colored passengers for Pullman space is

no defense to a charge that under segregation which

results in the occupancy of unequal facilities colored

passengers are denied equal protection of the laws.

That case dealt with an Oklahoma statute which al

lowed defendants to provide sleeping cars, dining cars,

and chair cars to be used exclusively by either white

or negro passengers, separately but not jointly. The

court below had concluded that sleeping cars, dining

cars, and chair cars, were, comparatively speaking,

Docket No. 27844— Sheet 11.

luxuries, and that it was competent for the legisla

ture to take into consideration the limited demand

for such accommodations by one race, as compared

with the demand on the part of the other. Complainant

relies upon the following statement contained in the

Supreme Court’s decision:

32

It is not questioned that the meaning of this

clause is that the carriers may provide sleeping

cars, dining cars and chair cars exclusively for

white persons and provide no similar accommo

dations for negroes. The reasoning is that there

may not he enough persons of African descent seek

ing these accommodations to warrant the outlay

in providing them. Thus, the Attorney General of

the State, in the brief filed by him in support of

the law, urges that “ the plaintiffs must show that

their own travel is in such quantity and of such kind

as to actually afford the roads the same profits, not

per man, hut per car, as does the white traffic, or,

sufficient profit to justify the furnishing of the

facility, and that in such case they are not supplied

with separate cars containing the same. This they

have not attempted. What vexes the plaintiffs is

the limited market value they offer for such accom

modations. Defendants are not by law compelled

to furnish chair cars, diners nor sleepers, except

when the market offered reasonably demands the

facility.” And in the brief of counsel for the ap

pellees, it is stated that the members of the legis

lature “ were undoubtedly familiar with the char

acter and extent of travel of persons of African

descent in the State of Oklahoma and were of the

opinion that there was no substantial demand for

Pullman car and dining car service for persons of

the African race in the intrastate travel” in that

State.

This argument with respect to volume of traffic

seems to us to be without merit. It makes the con

stitutional right depend upon the number of per

sons who may be discriminated against, whereas

the essence of the constitutional right is that it is

a personal one. Whether or not particular facil

ities shall be provided may doubtless be conditioned

upon there being a reasonable demand therefor, but,

if facilities are provided, substantial equality of

33

treatment of persons traveling under like condi

tions cannot be refused. It is the individual who

is entitled to the equal protection of the laws, and

if he is denied by a common carrier, acting in the

matter under the authority of a state law, a facility

or convenience in the course of his journey which

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 12.

under substantially the same circumstances is fur

nished to another traveler, he may properly com

plain that his constitutional privilege has been in

vaded.

Defendants say that what the Court evidently meant

by this comment was that a carrier could not abso

lutely refuse to afford colored passengers Pullman

accommodations, but had to provide them if there

was reasonable demand from colored passengers. In

any event, we are not here considering a constitutional

question, but rather questions of the act. Volume of

traffic is an important consideration in determining

whether certain services demanded are warranted and

whether a difference in treatment is justified.

At the hearing complainant stated that segregation

was not involved and apparently for the purpose of

this case he accepted it, regarding the Arkansas stat

ute as requiring it in that State for all passengers,

both interstate and intrastate. However, in his ex

ceptions he opposes it as abominable and urges that

the statute does not require it as to interstate pas

sengers. The statute is general in its terms in that

like the Mississippi and Kentucky statutes dealt with

by the Supreme Court, it does not mention either

intrastate or interstate passengers. These lat

ter statutes, as already stated, were by State courts

confined to intrastate passengers and the Supreme

Court accepted these constructions as binding on it.

Complainant also relies on the Supreme Court’s con

clusion in McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co.,

supra, to the effect that the Oklahoma statute had to

34

Docket No. 27844^-Sheet 13.

be construed as applying only intrastate because theie

bad been no construction to the contrary by the State

court. Be that as it may, the present case arose out

of the apparent assumptions of the parties that the

Arkansas statute was applicable to interstate traffic,

and while it is not for us to construe the statute, we

think, in view of its general terms, that until further

informed by judicial determination, defendants are

justified, as a matter of self protection, in assuming

that it applies to interstate, as well as intrastate,

traffic. What we are here dealing with is the practice

of the carriers in assumed compliance with the stat

ute, a practice which they could follow even if there

were no statute.

Complainant urges that collection of the first-class

fare, notwithstanding the fact that second-class ac

commodations were furnished him, was violative of

sections 1, 2, 3, and 6 of the act; also of the fourteenth

amendment, on the ground that he was deprived of

money without due process of law and denied equal

protection of the laws. It is sufficient to say that a

first-class ticket was furnished and charged for be

cause complainant wanted it, and that after it de

veloped that the first-class accommodations ordinarily

available for colored passengers west of Memphis were

all taken by other passengers defendants offered to

refund the difference. Moreover, as already stated,

complainant is here seeking no relief from the charges

paid.

Complainant urges also that the Rock Island, hav

ing received from him the first-class fare but having

failed to furnish first-class accommodations west of

Memphis, violated section 13(4) of the act. That pro

vision relates to intrastate fares that are unjustly

discriminatory or unduly prejudicial in their relation

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 14.

to interstate fares. No intrastate fares are here in

volved. There was no break in complainant’s journey

35

at the Tennessee-Arkansas State line. He was engaged

in through interstate travel from Chicago to Hot

Springs. Moreover, as said in the next preceding

paragraph, complainant was furnished a first-class

ticket because he asked for it, and refund awaits him.

Regardless of what finding may be made respecting

the Rock Island, the Illinois Central asks that the

complaint be dismissed as to it. There is no showing

that colored passengers are treated differently from

white passengers on their journeys from Chicago to

Memphis and apparently that road is in no way charge

able with discrimination, even though it participates

in the through transportation under joint fares and

other arrangements. This carrier is a proper, but

perhaps not necessary party. It was named as a

defendant apparently out of abundance of caution,

because it participated in the movement.

The Pullman Company also asks dismissal, regard

less of what may be done as to the Rock Island, con

tending that it is not chargeable with discrimination,

because it provides accommodations in the form of

drawing rooms, which if not already occupied or re

served for someone else, are available for colored

passengers west of Memphis at the 90-cent charge.

There is no discrimination on its part.

It is not for us to enforce the State law. We under

stand that to be a matter for State authorities. But

in deciding the case on the facts presented we must

recognize that under the State law defendants must

segregate colored passengers. In these circumstances

we find that the present colored-passenger coach and

the Pullman drawing rooms meet the requirements

of the act; and that as there is comparatively little

colored traffic and no indication that there is likely

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 15.

to be such demand for dining-car and observation-

parlor ear accommodations by colored passengers as

to warrant the running of any extra cars or the con

struction of partitions, the discrimination and preju-

36

dice is plainly not unjust or undue. Only differences

in treatment that are unjust or undue are unlawful

and within the power of this Commission to condemn,

remove, and prevent.

The complaint wall be dismissed.

E astman, Commissioner, dissenting:

In his dissenting expression Commissioner Lee has

correctly indicated the rule which railroads must fol

low to avoid unlawful discrimination between white

and colored passengers, where State statutes require

their segregation. So far as coach travel is con

cerned, it is clear that the Rock Island was not con

forming to this rule, when complainant made his trip

to Hot Springs, but is probably conforming to it now.

So far as Pullman accommodations are concerned, I

am not satisfied that defendants were observing the

rule then or that they are observing it now.

The latter conclusion I reach reluctantly, for I

realize that, where segregation is required, the prac

tical difficulties of observing the rule with respect to

Pullman accommodations are very great. The facts

are that white passengers were and are given adequate

opportunity to obtain seats, berths, compartments, or

rooms in Pullman cars, together with the right to use

any dining car or observation car that may be attached

to the train, whereas colored passengers have no op

portunity to obtain seats or berths in the body of the

car or to use dining or observation cars, but may ob

tain accommodations in a compartment or room, pro

vided one can be found that has not been previously

Docket No. 27844^-Slieet 16.

been taken by a white passenger. If the conditions

were reversed, I cannot believe that the white pas

sengers would regard this as equality of treatment and

opportunity.

The practical difficulty lies, of course, in the fact

that the demand for Pullman accommodations on the

part of colored passengers is very small. So long as

37

this condition exists, I am not prepared to say that

it is necessary for a railroad to attempt the partition

of observation or dining cars, but I do believe that it

is necessary to provide some Pullman space, small

though it may be, which will be reserved for the oc

cupancy of colored passengers and which white pas

sengers will not be permitted to occupy, and to pro

vide means by which meals from the dining car may

be served in such space.

Lee, Commissioner, dissenting:

The rule was laid down in the early days of this

Commission that it was the duty of the railroads to

furnish, for all passengers paying the same fare, cars

in all respects equal and provided with the same

comforts, accommodations, and protection for travel

ers. Councill v. Western & Atlantic R. R. Co., 1 I. C.

C. 339; William H. Heard v. The Georgia R. R. Co.,

1 I. C. C. 428. It was further held “ * * * that the

separation of white and colored passengers paying

the same fare is not unlawful if cars and accommo

dations equal in all respects are furnished to both

and the same care and protection of passengers is

observed.” Edwards v. Nash., Chat. & St. Louis Ry.

Co., 12 I. C. C. 247. In the latter case the Commission

said:

“ While, therefore, the reasonableness of such

regulation as to interstate passenger traffic is es

tablished, it by no means follows that carriers may

discriminate between white and colored passengers

in the accommodations which they furnish to each.

If a railroad provides certain facilities and accom

modations for first-class passengers of the white

race, it is commanded by the law that like accom-

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 17.

modations shall be provided for colored passengers

of the same class. The principle that must govern

is that the carriers must serve equally well all pas

sengers, whether white or colored, paying the same

38

fare. Failure to do this is discrimination and sub

jects the passenger to ‘ undue and unreasonable prej

udice and disadvantage.’ ”

In each of the three cases, because the railroad had

furnished colored passengers inferior accommodations

to those furnished white passengers of the same class,

a finding of discrimination was made. No decision

has been found in which this Commission, on such

facts, has held to the contrary.

In this case complainant, traveling on a first-class

ticket and offering to pay for a seat in the Pullman

car, to which the Pullman porter had assigned him,

and in which there was “ plenty of space” , was re

quired to move from the Pullman car into the coach

provided for colored passengers. The latter was

described as “ an old combination affair” , not air-

conditioned, which was divided into three parts, and,

except in the Avomen’s section, was Avithout wash

basins, soap, towels, or running water.

Testifying for defendants, the conductor, Avho re

fused to sell complainant a seat in the Pullman car,

and had him removed into the coach provided for

colored passengers, said that “ during the thirty-two

years I have worked over there in Arkansas, for the

Rock Island Railroad Company, it has never had any

first-class accommodations for Negroes” and “ I would

not have sold a seat in Section 3 or any other space

in the Pullman car to Congressman Mitchell because

he Avas a colored person. ’ ’ Witnesses other than com

plainant testified that they had been refused Pullman

accommodations on Rock Island trains solely because

they were Negroes. In view of this evidence, I ques

tion the statement in the report that Pullman accom

modations ordinarily “ are a Available to colored pas

sengers upon demand.”

Docket No. 27844—Sheet 18.

I f the action complained of does not constitute undue

or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage under the

39

act, as those terms are understood, then I am at a loss

to understand their meaning. The act which we ad

minister authorizes no difference in treatment of

passengers because of color, and it is my understand

ing that the segregation statutes of the State require

equal accommodations for persons of the two races.

No doubt the action of the Rock Island in refusing to

permit complainant to occupy a seat in the Pullman car

was due to the State statute, requiring the segregation

of white and colored passengers. Conceding the car

rier’s legal right to segregate white and colored pass

engers in the State of Arkansas, in segregating such

passengers, it must accord to one class accommoda

tions substantially equal to those accorded the other.

If the carrier provides certain accommodations for

first-class white passengers, it is required to provide