Walker v. City of Birmingham Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. City of Birmingham Reply Brief, 1966. f260ad47-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/46b43478-6aed-4aca-9fdc-2c5a33f742b8/walker-v-city-of-birmingham-reply-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

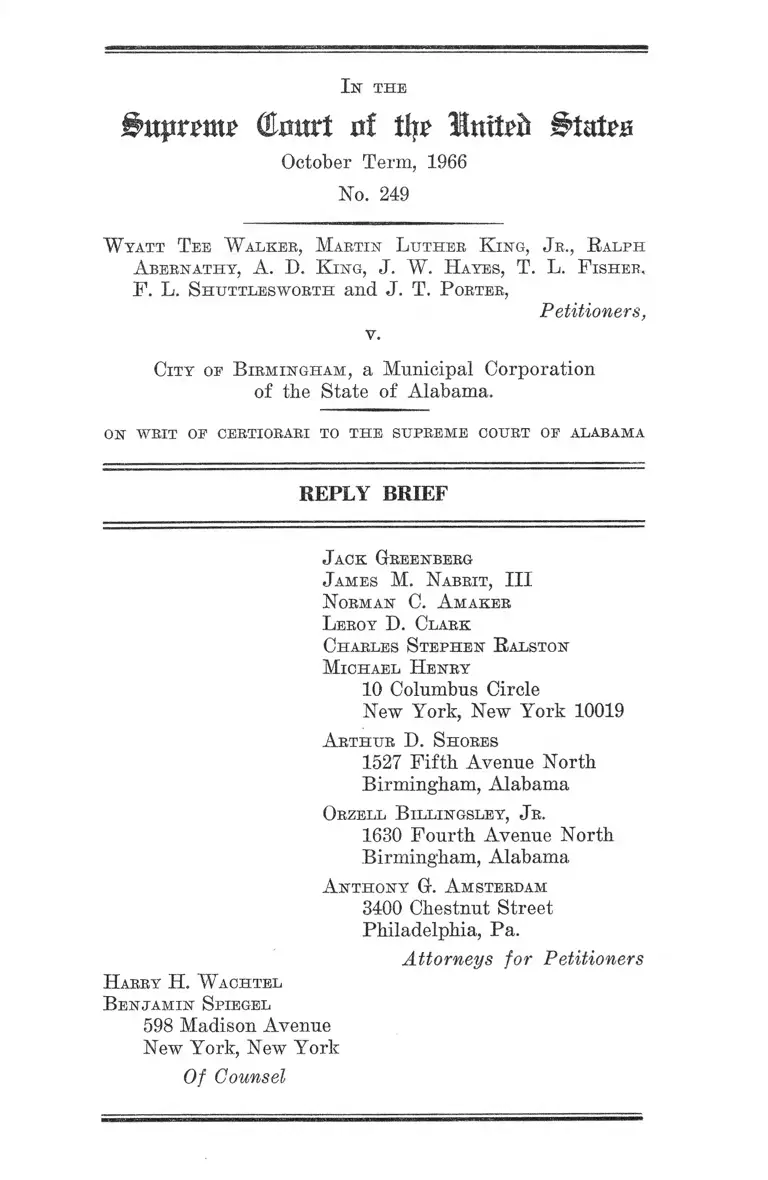

In th e

(Enitrt ni % Untteft dtateR

October Term, 1966

No. 249

W yatt T ee W alk eb , M abtin L u th er K ing , J r ., R alph

A bern ath y , A. D. K in g , J. W. H ayes, T. L. F ish er ,

F . L. S h u ttlesw orth and J . T . P orter,

Petitioners,

v.

Cit y of B ir m in g h a m , a Municipal Corporation

of the State of Alabama.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

REPLY BRIEF

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A m aker

L eboy D . Clark

Charles S teph en R alston

M ichael H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A rt h u r D . S hores

1527 Fifth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Orzell B illin gsley , J r .

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

Attorneys for Petitioners

H arr y H. W achtel

B e n ja m in S piegel

598 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

Of Counsel

Isr th e

(Emtrt of % lUttfrd §>Mm

October Term, 1966

No. 249

W yatt T ee W alker , M artin L u th er K in g , J r ., R alph

A bernath y , A. D. K in g , J. W. H ayes, T. L. F ish er ,

F. L. S h u ttlesw orth and J. T. P orter,

Petitioners,

v.

City of B ir m in g h am , a Municipal Corporation

of the State of Alabama.

REPLY BRIEF

1. The City has argued that the Court applied a rule

that the invalidity of an injunction may not be litigated

in defense of a criminal contempt charge to the area of

free speech in Iiowat v. Kansas, 258 U.S. 181. While we

doubt that this is a proper reading of Iiowat, supra,1 the

simplest answer to the City’s claim is that Iiowat was de

cided at a time when the protections of the First Amend

ment were deemed inapplicable to the States. In Prudential

1 The opinion of the Court in Iiowat v. Kansas, 258 U.S. 181, makes

no reference to any defense grounded on freedom of speech. The de

fendants in Howat attacked their convictions on the ground of the federal

uneonstitutionality of a Kansas “ compulsory arbitration law.” The state

courts sustained the injunctive power of the court on grounds independent

of that statute. Inasmuch as the state court “ did not depend on the con

stitutionality of that act for its jurisdiction or the justification of its

order” (258 U.S. at 190), the Court concluded that the case was decided

“ in the state courts on principles of general, and not Federal, law . . . ”

(ibid.).

2

Ins. Go. v. Cheek, 259 U.S. 530, 543, the Court said that

“neither the Fourteenth Amendment nor any other provi

sion of the Constitution of the United States imposes upon

the State any restriction about ‘freedom of speech’ , . . . ”

Not until Gitlow v. Neiv York, 268 U.S. 652, 666, did a ma

jority of the Court “ assume” that the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment protected free speech against

infringement by the States. Only subsequent to Gitlow,

supra, were there holdings that the First Amendment pro

tections applied against the States.2

2. The Brief for Respondent (pp. 48-62) also argues

that the contempt convictions should be sustained on the

basis of conduct other than a violation of Birmingham City

Code Section 1159, the law forbidding parades, proces

sions, or demonstrations without a permit. The City claims

that the conviction can be sustained on a conspiracy charge,

on charges of congregating in mobs and of conduct calcu

lated to cause breaches of the peace, and for violation of

a battery of statutes and ordinances relating to pedestrian

traffic.

It is sufficient answer that none of these charges were

relied upon, or even mentioned by either of the courts be

low.3 Both courts below relied on the theory that peti

2 See, e.g., Fishe v. Kansas, 274 U.S. 380; Stromberg v. California, 283

U.S. 359, 368; Dejonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353, 364.

8 The City seeks support for its conspiracy theory in a statement by

the trial court that petitioners made “ concerted efforts” to violate the in

junction. (Brief of Respondent, p. 19, note 9.) The quoted language does

not support the City’s assertion that the court found a conspiracy. In

deed, neither court below even used the word “ conspiracy.”

Nothing in either opinion below supports the notion that petitioners

were convicted for violation of provisions enjoining congregating in mobs

or conduct calculated to cause a breach of the peace. The trial court did

not state that petitioners were charged with any such violations; it men

tioned only the charges that they issued a press release containing deroga-

3

tioners violated the injunction’s prohibition against parades

without permits (R. 420, 437-438). It would be impermis

sible for this Court to affirm the petitioners’ contempt con

victions on a ground on which the courts below did not

choose to put the convictions and did not make any find

ings. Garner v. Louisiana, 368 ILS. 157, 164. And, if the

Supreme Court of Alabama had relied on the various

grounds now relied on by respondent, it would have vio

lated the principle of Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196, by

affirming a criminal conviction on appeal on the basis of

charges never litigated at trial. See also, Shuttlesworth

v. Birmingham, 376 U.S. 339 (per curiam). Furthermore,

respondent’s claim merely reinforces petitioners’ objection

that the injunction was vague and overbroad. We point

out one example. If, as the City now claims for the first

time, petitioners were convicted for violating Birmingham

City Code sections 1142 or 1231 (Brief of Respondent,

pp. 49, 79-80), the convictions obviously would be invalid

under Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87, a case

involving the very same two laws. Moreover, notwithstand

ing the City’s rhetoric in referring* to mobs, riots, violence

and disorder, there is simply no evidence that petitioners

engaged in any such conduct. We submit that the descrip

tion of the events of April 12 and April 14, 1963 in Peti

tory statements about Alabama courts and the injunctive order and that

they participated in parades without a permit (R. 420). The Alabama

Supreme Court found a violation of the order on the basis of parades

without a permit (R. 437-438), relying on a supposed concession in peti

tioner’s brief in that court (ibid.).

The claim that petitioners’ convictions may be sustained on the theory

that they violated a host of laws regulating pedestrian traffic and other

matters (Brief of Respondent, pp. 49, 77-83) is insupportable. None of

these laws was ever mentioned in this litigation before the City’s brief

in this Court. It is absurd for the City to contend at this late date that

petitioners were convicted for jaywalking, failing to keep to the right

side of crosswalk, loitering or some similar violation, when no such claim

was ever made or considered in any court below.

4

tioners’ Brief, pp. 16-22, fairly and completely describes

the record.

Respectfully submitted,

H a r r y H . W achtel

J ack G-reenberg

J ames M . N abrit, I I I

N orman C. A m aker

L eroy D . Clark

Charles S teph en R alston

M ichael H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A r th u r D . S hores

1527 Fifth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Orzell B illingsley , J r .

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

A n t h o n y G-. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

Attorneys for Petitioners

B e n ja m in S piegel

598 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

Of Counsel

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 219