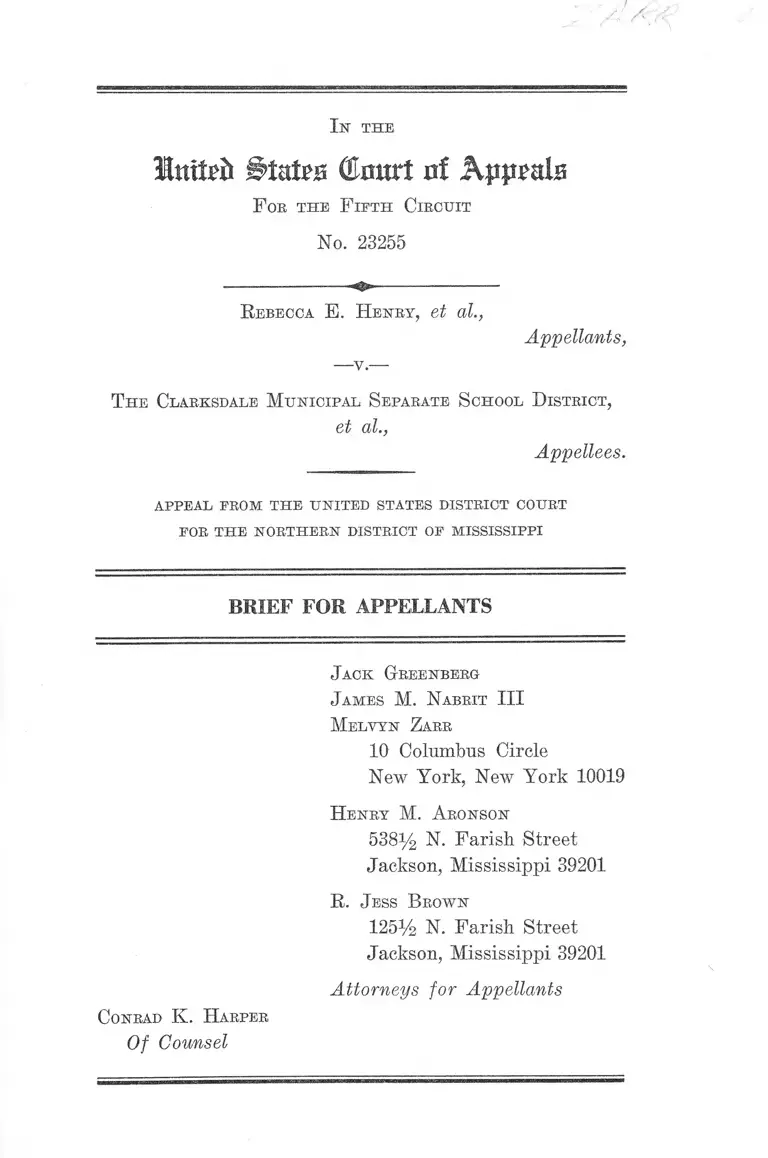

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 22, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District Brief for Appellants, 1966. 4a1cc20b-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/46d034d7-1796-412a-9553-bf8855374fb3/henry-v-clarksdale-municipal-separate-school-district-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

MnlUft down of Kppmlz

F oe t h e F if t h C ib c h it

No. 23255

R ebecca E. H e n r y , et al.,

Appellants,

— v . —

T h e C larksdale M u n ic ip a l S epa ra te S chool D is t r ic t ,

et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

C onrad K. H a rper

Of Counsel

J ack G r een b er g

J a m es M. N abrit III

M elv y n Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H e n r y M. A ronson

538% N. Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

R. J ess B ro w n

125% N. Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case......... ................................... ....... 1

A. Summary of the Litigation______________ -.... 1

B. Statement of Facts ............ ..........................-....— 4

1. Summary of Desegregation under the Board’s

Plan ................................................. 4

2. The Board’s Zoning Scheme ............................. 5

3. Testimony of Educational Experts................ . 10

4. Effect of State Action on Board’s Zone Lines 16

(a) Testimony of School Board Attorney

Luckett ......................................... 17

(b) Testimony of City Commissioner Bell .... 18

(c) Testimony of City Planning Commission

Chairman ...... 20

(d) Testimony of Dr. Aaron H enry .............. 20

5. Opinion of the Court Below............................ 21

6. The Board’s Revised Zone Lines..................... 26

Specifications of Error .................... 27

A r g u m e n t

I. Effectuation of the Brown Decision Bars the

Board’s Use of a Neighborhood School Assign

ment Policy to Justify Its Failure to Eliminate

Segregated Schools, Particularly Where State

Action and Custom Combine to Maintain Neigh

borhoods on a Racial Basis................................ 29

11

II. Actions oy City and County Officials to Effec

tively Remove Virtually All Negroes From

White School Zones Do Not Relieve the Board

of Its Constitutional Obligation to Desegregate

the Schools ....................... .................................. 35

III. The Board’s Plan Falls Short of This Court’s

Standards of Acceptable Pupil and Teacher

Desegregation ............ ...... ............................ 39

C o n c lu sio n ................... ....................................................................... 45

PAGE

T able of C ases

Balaban v. Rubin, 40 Misc. 2d 249, 242 N. Y. S. 2d 974

(Sup. Ct. 1963), rev’d, 20 App. Div. 2d 438, 248

N. Y. S. 2d 574 (2d Dept.), aff’d 14 N. Y. S. 2d 193,

199 N. E. 2d 375 (1964), cert, denied 379 U. S. 881

(1964) ........... .......................... .................................... 33

Barksdale v. Springfield School Comm., 237 F. Supp.

543 (D. Mass. 1965), vacated without prejudice, 348

F. 2d 261 (1st Cir. 1961) ............ ............................... 33

Beckett v. School Board of Norfolk, Civ. No. 2214

(E. D. Va.) ........................................................... ....43,44

Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 213 F. Supp. 819

(N. D. Ind. 1963), aff’d 324 F. 2d 209 (7th Cir. 1963),

cert, denied 377 U. S. 924 (1964) .......... ..................... 33

Blocker v. Board of Education of Manhasset, 226 F.

Supp. 208 (E. D. N. Y. 1964) .................................... 33

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Brax

ton, 326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964) .................... ........ 40

Booker v. Board of Education of Plainfield, 45 N. J.

161, 212 A. 2d 1 (1965) 33

I l l

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) .............. 33

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 382

U. S. 103 (1965) .................................................. 33,39,40

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, Civ. No.

3353 (E. I). Va.) .......................................................... 44

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C.

1955) ....... ........... ...................................................... 23,25

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington, Virginia,

324 F. 2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) .................................... 30

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483

(1958) ........ - ............................................. 25, 29, 31, 32, 39

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ............................ 31

Dowell v. School Board of the Oklahoma Public

Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427 (W. D. Okla. 1963) ....36, 39,44

Dowell v. School Board of the Oklahoma Public

Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W. D. Okla. 1965) .......37, 41,

42, 44

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, Kansas,

336 F. 2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert, denied 380 U. S.

914 ........................... .................................................... 33

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) .............. 30

Gilliam v. School Board of City of Hopewell, Virginia,

345 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1965), reversed on other

grounds, sub nom. Bradley v. School Board of City

of Richmond, 382 IT. S. 103 (1965) ............................ 33

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339 (1960) ................. 36

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683 (1963) ...... 33

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U. S. 218 (1964)

PAGE

33

PAGE

IV

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach,

Fla., 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958) ...........................- 36

Houston Independent School District v. Ross, 282 F. 2d

95 (5th Cir. 1960) ........................................................ 33

Jackson v. Pasadena School Board, 31 Cal. Rptr. 606,

382 P. 2d 878, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 924 (1963) .......... 33

Ivier v. County School Board of Augusta County, 249

F. Supp. 239 (W. D. Ya. 1966) ..................... 39, 41, 42, 44

Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County,

Ga., 342 F. 2d 225 (5th Cir. 1965) ............................ 40

Morean v. Board of Education of Montclair, 42 N. J.

237, 200 A. 2d 97, 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 688 (1964) ....... 33

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ............................ 30

Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348 F.

2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965) ......... ................................... 22, 39

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U. S. 198 (1965) .......................... 39

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F. 2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963) ................. 30

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F. 2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) ...........................25, 29

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal School District, 355

F. 2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ......................................... 39,41

V

PAGE

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) ......................... 32

Taylor v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 191

F. Supp. 181 (S. D. N. Y. 1961) ................................ 36

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Wright, Public School Desegregation: Legal Remedies

for De Facto Segregation, 40 N. Y. U. Law Rev. 285

(1965) .......................................................................... 38

I n t h e

Unite?* States (Cmtrt nf Appeals

F oe t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 23255

R ebecca E. H e n r y , et al.,

Appellants,

T h e Clarksdale M u n ic ip a l S eparate S chool D is t r ic t ,

et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

A.

Summary of the Litigation

Negro parents and pupils residing in Clarksdale, Mis

sissippi appeal the December 13, 1965 order of the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Missis

sippi approving a desegregation plan submitted by Clarks

dale school authorities pursuant to its orders of June 26,

1964 and August 10, 1965.

2

Suit was filed in April, 1964 seeking injunctive relief

against the Board’s policy of maintaining the public schools

of Clarksdale on a segregated basis (R. 1-12).1 The Board’s

answer admitted the schools were segregated (R. 13-19),

and the district court on June 26, 1964 granted plaintiffs’

motion for a temporary injunction, ordering the Board to

prepare a desegregation plan which would provide a mini

mum of one desegregated grade for the school term be

ginning September, 1964 (R. 20-24). In response, the

Board submitted a plan consisting of four alternative modi

fied stair-step time schedules for desegregation, each of

which was to be accomplished by the assignment of pupils

in accordance with newly designed school boundaries or

zone lines (R. 25-49). Plaintiffs filed objections to the

method and speed of the desegregation proposals (R. 46-

49), but the district court, following an August 19, 1964

hearing of these objections, ordered into effect portions of

two of the Board’s plans “as a tentative and interim pro

cedure” (R. 63) for the purpose of requiring the desegre

gation of grade 1 in September, 1964 and of grade 2 in

January, 1965 (R. 63-64).

On January 5, 1965, appellants filed a motion for further

injunctive relief alleging that no actual desegregation had

resulted from the Board’s implementation of its plan and

1 Negroes in Clarksdale had sought school desegregation since

August, 1954 when a petition, signed by 454 heads of families, was

submitted to the school board (R. 425). The Board never replied,

but the petition and the names of its signers were published in a

local newspaper, with the result that various pressures and intimi

dations caused some of them to withdraw their names (R. 425-26).

Following this, there was less activity for school desegregation, but

another petition, signed by the parents of 25 children, was filed in

1963 (R. 427-28). Again, there was no response from the Board

and again the petition and the names of its signers were published

in a local newspaper (R. 428). Thus followed this action (R. 8-9).

3

that, because of the nature of the plan, no desegregation

could be expected to result (E. 65-67). A full hearing was

held on April 8 and 9, following which the district court,

on August 10, 1965, issued an order (R. 111-17) approving

some of the school zones submitted by the Board and

directing the Board to reconsider their proposals as to

certain other school zones, which nevertheless were “tem

porarily approved” for the Fall semester (E. 115). The

order required inter alia desegregation of five grades for

the 1965-66 school year and the desegregation of the re

maining seven grades during the following two years

(R. 112).

Appellants filed a motion to amend the findings and

judgment (R. 120-125), asserting that court approval of

zone lines conforming to racial neighborhoods and violat

ing educational standards effectively foreclosed any de

segregation for a second year; the motion also challenged

the basis for findings concerning the validity of the zone

lines (R. 122) and asserted that the district court’s con

clusion that the Board had no affirmative constitutional

duty to integrate its schools was incompatible with de

cisions of this Court (R. 123-24). It was denied on August

30, 1965 (R. 126).

In October, 1965, after the start of the new school year,

the Board, in compliance with the district court’s August

10th order, filed a revised plan for those attendance zones

which had not received final court approval (R. 127-35).

Appellants filed objections to the revised plan, pointing out

that only two of the five zones had been altered and that

the Board’s recommendation that two zones be combined

would not, under the circumstances, desegregate those

4

zones. Appellants also opposed the Board’s request that

all zones be retained in their present form until the Fall

of 1966 (R. 136-40). Following a hearing on November 15,

1965, the district court, on December 13, 1965, approved

all the Board’s zone boundaries (R. 148-49). Appellants

filed a notice of appeal on December 14, 1965 (R. 150).

B.

Statement of Facts

1. Sum m ary of Desegregation Under the B oard’s Plan

Public school desegregation was initiated in Mississippi

in the Fall of 1964, after four school districts, including

Clarksdale, were enjoined by federal courts to desegregate

at least 1 grade. Three systems, Jackson, Biloxi and Leake

County, offered first graders their choice of Negro or white

schools, and 61 Negro children enrolled in formerly all-

white schools.2 3 Clarksdale devised an assignment plan

under which all first graders were assigned in accordance

with redrawn school zones lines (R. 25-45, 50-62). As a

result not a single child was enrolled in a desegregated

school (R. 160-62). For the second semester of the 1964-65

school year the Board was required to assign all second

grade pupils in accordance with its school zone lines and

again not a single child teas enrolled in a desegregated

school3 (R. 163-64).

When this case was heard in April, 1965, there were

almost 5,000 students attending the Clarksdale public

2 Yol. II, Southern School News, p. 1 (Sept. 1964).

3 The Board reported that approximately 64 first and second

grade white pupils were residing’ in Negro school zones but that

some entered private schools and others moved or left the system.

None attended desegregated schools (R. 160-64).

5

schools (B. 157-59), but the 2,800 Negro pupils continued

to attend the five Negro schools and the 2,100 white chil

dren continued to attend the six white schools.4

When the Clarksdale schools opened in September, 1965,

they were under the court’s August 10, 1965 order to de

segregate five grades (3, 4 and 12 in addition to grades 1

and 2) (B. 112). But again, no pupils were enrolled in

schools formerly serving the opposite race (B. 195), until,

however, two Negroes were permitted to transfer to a

white school.5

2. The Board’s Zoning Schem e

The City of Clarksdale is bisected from the northeast

to the southwest by a main line of the Illinois Central

Bailroad track. Traditionally, most Negroes in the City

have lived south of these tracks, while the great majority

of the City’s white residents live north of the tracks (B.

381, 775, Population Distribution Map). The Higgins High

School, containing all the Negro pupils in grades 7-12 (ex

cept two), is located south of these tracks, while the high

4 The Clarksdale Board and the Coahoma County Board, under

a written agreement, shared jurisdiction over combined high school

facilities operated for all white high school children in the City

and County. Based on this fact, the Coahoma County Board had

been named a defendant in the complaint (It. 4) ; however, this

agreement was permitted to expire at the end of the 1964-65 school

year (R. 73,156).

5 Following the opening of school, two Negro girls in the 11th

‘grade requested Latin, a course not offered at the Negro Higgins

High School. Under provisions of the court’s August 10, 1965

order requiring the granting of transfers to obtain courses not

offered at schools vdiere they were initially enrolled (R. 114),

they obtained transfers to the white Clarksdale High School (R.

195).

6

schools containing all the white public high school pupils

are located north of the tracks (R. 219, 381).

In similar fashion, four elementary schools, Oliver, Hall,

Washington and Riverton, containing all the Negro ele

mentary pupils, are located south of the Illinois Central’s

tracks. Three of the four elementary schools serving white

pupils are located north of the tracks. The fourth elemen

tary school, Eliza Clark, is located in a white residential

section south of the tracks (R. 273).

The Board maintains that the race of residents was not

considered in drawing zone lines (R. 212, 248), except as

an “incidental factor” (R. 212, 248, 710), with school utiliza

tion, proximity, natural boundaries and safety and health

the major considerations (R. 263). The Board has admitted

following historical boundary lines utilized under the seg

regated system (R. 281-82). Thus, boundary lines such as

the Illinois Central tracks which bisect the City (R. 270)

and the Wilson Avenue line dividing white Eliza Clark and

Negro Myrtle Hall zones (R. 246-47) have traditionally

served as boundaries between Negro and white neighbor

hoods (R. 164-67). The result of continuing to use these tra

ditional zones has been to continue Negro pupils in Negro

schools and white pupils in white schools. Based on Board

statistics provided in March, 1965, 865 Negro high school

pupils, all but two of the total eligible to attend high school,

live south of the Illinois tracks, attend Higgins, and if the

Board has its way, will continue at Higgins (R. 183).6

6 The Board reported 198 of the 1,023 white high school pupils

reside south of the Illinois Central tracks (R. 183), but half of

these live in the Eliza Clark zone, and it is unlikely that any would

attend the Negro Higgins High School if assigned there.

7

As to elementary schools, the Board has zoned the one

white and four Negro elementary schools located south of

the Illinois Central tracks so that all Negroes will be

assigned to schools traditionally serving Negro pupils and

the great majority of white pupils will be assigned to the

white Eliza Clark School. The three remaining white ele

mentary schools located north of the Illinois Central tracks

have been zoned so as to serve only pupils living north of

the tracks (R. 186, 610). Few if any of these students are

Negroes. In fact, the Board estimated that in December

1964, only one Negro elementary school child was eligible

by reason of residence to attend an elementary school now

serving only white pupils (R. 168).T

The Board has followed traditional racial boundary lines

even when they appeared to clash with standards of efficient

school utilization, proximity and other generally accepted

school zoning criteria. For example, the Eliza Clark zone

completely encompassed all white pupils living in the largest

white neighborhood located south of the Illinois Central

tracks, but did not include even one Negro (R. 168), though

Negro neighborhoods surround the Eliza Clark zone on

three sides. While railroad tracks mark the northern and

western boundaries and a highway makes up its southern

boundary, these geographical features do not interfere with

travel, as indicated by the number of pupils required to 7

7 As with the high school students, a percentage of white ele

mentary pupils (145 of 1025) reside in attendance zones serving

Negro schools. But the experience thus far is that none will choose

to accept assignment to such schools.

8

cross both the tracks or the highway under both the Board’s

old (R. 164-67) and new zones (R. 270-71).8

The eastern boundary of the Clark school zone followed

a Clarksdale street, Wilson Avenue, which is only 200 feet

from the school (R. 277). Wilson Avenue is not a major

thoroughfare, is only partially paved, and in some parts

is only a rut through a grassy area (R. 281-82). Its sole

distinguishing characteristic is that whites reside in great

numbers along the western half and Negroes reside in great

numbers along its eastern half (R. 280). Finally, it ap

pears that Negroes live south of Highway 61, which was

the southern boundary of the Eliza Clark zone (R. 282-

83).

The Board Superintendent explained that capacity of the

Clark School and its physical condition dictated the draw

ing of the school’s zone boundaries (R. 280-81). But the

three adjoining Negro elementary schools are all more

crowded than Eliza Clark (R. 183). Indeed, Negro schools

are generally more crowded than schools serving white

pupils. Teacher-pupil ratios are generally higher in the

Negro schools, even though Negro teachers until 1965 were

paid less than white teachers with similar qualifications (R.

610), and the Board traditionally has spent more money

per pupil in white than Negro schools (R. 173, 185).

The Board Superintendent, G-ycelle Tynes, testified that

the system was committed to the neighborhood school plan

which was “time-honored” and “time-tested” (R. 206, 263),

8 During the 1963-64 school year, before this suit was filed, the

Board assigned 710 pupils to schools which required travel across

the Illinois Central Railroad tracks bisecting the City from east

to west. A total of 594 pupils were so assigned during the 1964-65

school year (R. 184-85).

9

that the Board’s adherence to this philosophy was strict,

and that all pupils were required to attend the schools in

their zones (R. 211). In practice, however, the Board has

assigned pupils to schools outside the zones of their resi

dence :

1. All white elementary pupils residing in Zone E-3A,

pending construction of a school in that zone are assigned

to either the Eliza Clark (Zone E-1C) or the Oakhurst

(Zone E-4A) schools (R. 27, 194, 698). When the zone

lines were drawn to include a zone with no school, the

Board estimated that the new building would be ready for

occupancy by September, 1966 (R. 43). In October, 1965,

they reported no school would be constructed until there

were sufficient children in the district to justify a school

building (R. 195-96), and conceded at the November, 1965

hearing that they do not now own sufficient land in the

zone to construct an adequate school (R. 696).

2. Approximately thirty percent of the pupils at the

Eliza Clark School (42 of 147) do not reside within the

Eliza Clark Zone (R. 702-03).

3. During the first semester of the 1964-65 school year,

all pupils who were to be assigned to the new Riverton

School (elementary zone E-2B) when it opened in January,

1965, were assigned together with teachers to two Negro

schools in the system (R. 27).

4. During the current school year, the Board, in order

“to better utilize available class rooms,” enrolled two classes

of pupils in Myrtle Hall who actually reside in the George

Oliver area (R. 707) and a class of sixth grade pupils in

the Riverton School (Zone E-2B) who reside in Zone E-2A,

the Washington School Zone (R. 193-94, 701, 704).

10

3. Testim ony o f Educational Experts

To support the contention that the Board’s zone lines

were gerrymandered to frustrate school desegregation, ap

pellants obtained the assistance of Reginald Neuwein9 and

Myron Lieberman,10 two authorities in the field of educa

tional administration. The two experts spent several days

studying statistics on the school system and surveying the

schools and the community (R. 455, 533). At the April, 1965

hearing, both men testified that, as drawn, the Board’s zone

lines violated generally accepted criteria for school zones

and could be regarded only as an effort to maintain seg

regated schools. They noted that Negro schools were over

crowded and understaffed and that Negro teachers were

underpaid, with the result that these schools were not

9 Reginald Neuwein has 36 years of educational experience and

at present is director of a study of 13,000 elementary and 2,400

secondary Catholic schools in the United States conducted from the

University of Notre Dame. He was Superintendent of Schools in

Stamford, Connecticut and was Director of Administrative Re

search at the Educational Research Council of Greater Cleveland

in Cleveland, Ohio, in which position he advised school superin

tendents and completed 15 school system surveys similar to the

study requested by appellants of Clarksdale’s school system (R.

452-54).

10 Myron Lieberman is Chairman of the Professional Studies Di

vision at Rhode Island College and has charge of the Departments

of Elementary Education, Secondary Education, Industrial Arts

Education, Psychology, Philosophy, the Laboratory School of over

700 pupils and student teaching and faculty research programs.

He has taught at the University of Illinois, Hofstra University,

Emory University, the University of Oklahoma, and served as

Chairman of the Department of Education at Yeshiva University.

Dr. Lieberman, who earned a Ph.D. Degree in Education at the

University of Illinois has over 10 years of experience in work deal

ing with the interrelationship between race and education. He has

published articles and books, given lectures and chaired conferences

dealing with race relations and race in education and served as a

desegregation consultant to the New Rochelle, New York school

system and other systems working on school integration problems

(R. 531-32).

11

capable of offering the quality of education offered at the

white schools. They stated emphatically that both elemen

tary and high school zone lines could be redrafted so as

both to improve school utilization and to provide for a sub

stantial amount of desegregation—despite the increasingly

rigid neighborhood racial patterns.

Reginald Neuwein (R. 452) was critical of the placement

of the schools (R. 457) and stated that the school zone

lines did not meet generally accepted criteria (R. 459).

He noted that on both counts the white Kirkpatrick (Zone

E 4-B) and Heidelberg (Zone E 4-C) schools located north

of the Illinois Central tracks in an all white area appeared

well placed and well balanced (R. 459-60), but compared

the Negro Myrtle Hall (Zone E 1-B) and white Eliza

Clark (Zone E 1-C) school zones (R. 461-62), which are

divided by a street (Wilson Avenue) on which Negroes live

on one side and whites on the other (R. 463), and concluded

that no desirable educational benefit occurred from draw

ing the line in this fashion (R. 463-64).

Mr. Neuwein recommended that the zone lines for Eliza

Clark (Zone E 1-C), Riverton (Zone E 2-B) and Washing

ton (Zone E 2-A) be redrawn (R. 465). He also found fault

with the location of the high schools (R. 466-67), suggested

that since the Illinois Central Railroad tracks provided no

serious barrier or hazard, it should not be an automatic

zone line (R. 468-69) and that a more appropriate zone line

between the high school facilities could be drawn in a gen

erally north-south fashion (R. 469-70). Such a zone line

would have educational benefits (R. 470) and would not

serve to perpetuate segregation, as does the present line

(R, 470-71).

Mr. Neuwein compared average class size statistics for

the Negro and white schools and found the average enroll

ment in the white schools 25.1 pupils per class as compared

with a figure of 35.3 pupils per class in the Negro schools

(E. 473). He stated that the differential has a substantial

effect on the quality of education offered in the Negro and

white schools (E. 473-74), because teachers in the larger

classes in Negro schools are less able to administer to the

needs of individual children (E. 477-78).

Another important factor was the average per pupil ex

penditure, which in 1964 was $202.62 for each Negro ele

mentary pupil and $295.00 for each white pupil (E. 475).

Of this amount, there is a difference of $76.00 per pupil

on salary expenditures and $17.00 per pupil for other

operational costs (E. 474-75). At the high school level,

the Board expends $292.00 for each Negro pupil and $424.00

for each white pupil with a differential of $79.00 per pupil

for teacher salaries and $52.00 differential for other opera

tional expenses (E. 476).

Mr. Neuwein concluded that the present zone lines should

be completely re-examined and redrawn to better balance

school population. Such redrawn lines would also accom

plish desegregation (E. 479). Thus, while agreeing that the

white Kirkpatrick and Heidelberg schools appeared prop

erly zoned (E. 510), he stated that these schools were part

of a system that could not truly be desegregated until all

schools were properly zoned (E. 520). Desegregation would

also be furthered, according to Mr. Neuwein, by selection

of faculty according to qualifications and without regard

to race (E. 480-81).

Dr. Myron Lieberman (E. 531) testified that, based on

his study of the Clarksdale school system, he had concluded

12

13

the zone lines were not drawn in accordance with sound

administrative procedures (R. 533). Citing as examples

the Oakhurst, Clark, Hall and Washington school zones,

he indicated that while boundaries should minimize travel

distances and maximize utilization of schools, the white

Clark School was operating at % capacity, while the adjoin

ing Negro Hall and Washington schools were both above

capacity (R. 533-34). He recommended altering the zone

lines so as to assign pupils from Hall and Washington

schools to the Clark school and made similar suggestions

concerning the new Riverton School which was already op

erating close to capacity (R. 534-35).

Based on the number of pupils presently crossing the

Illinois Central Railroad tracks, Dr. Lieberman agreed

with Mr. Neuwein that there was no reason to utilize the

tracks as a boundary in the Clarksdale community and

that some pupils assigned to the Riverton School should

be assigned to the Oakhurst School (R. 537-38).

Dr. Lieberman stated that it would be a miracle if the

Board’s school utilization policies had not adversely af

fected the education of both white and Negro pupils (R.

539). He cited the larger class sizes in Negro schools and

the fact that Negro pupils must travel longer distances

to their assigned schools. He also pointed to the greater

salary of white teachers, the narrower curriculum in the

Negro schools and the fact that even the rated capacity of

Negro schoolrooms is set higher than the figure for white

schoolrooms of similar size (R. 539-41).

As to teacher assignment, Dr. Lieberman noted that there

are 700 more elementary school Negro than white elemen

tary school pupils but only four more Negro teachers

14

assigned to Negro elementary schools than to white ele

mentary schools. He described this as a “staggering dif

ference”, adding that the situation is probably even worse

because there are five teachers in white schools who are

not assigned to classes, but are available for supervisory

or remedial work with pupils. He described the situation

as impossible to defend on any sound administrative basis

(E. 542).

Dr. Lieberman described as an “obvious conclusion” that

the effect of the board’s school zone lines, school construc

tion policy and the school addition policy had the effect

of retaining segregation (R. 543). He stated that if each

pupil in the system were merely assigned to the school

located nearest his home, the lines would have been drawn

much differently, particularly with regard to the Clark,

Hall and Washington school zone lines (E. 543). In addi

tion, some pupils now assigned to Riverton would go to

Oakhurst where there is substantial space available (B.

543-44). He made a similar suggestion as to the high school

zones, indicating that a north-south line, perhaps using the

Sunflower River as a dividing line between the high school

facilities, would probably be the best solution to maximize

utilization of facilities and distance factors (R. 545). He

also suggested that differences in curriculum at the high

school level made necessary some flexibility in the Board’s

transfer policy to enable transfers for genuine educational

reasons (R. 545-46).

He stated that the neighborhood school policy has many

interpretations, but added:

In this community the only criterion for ‘neighbor

hood’ that I can honestly see is in using the criterion of

15

race, that ‘neighborhood’ seems to be defined by ‘white’

or ‘Negro.’ It certainly isn’t defined in terms of distance

from school, because if it were there would be many

Negro pupils going to schools that now enroll only

whites and there would be some white students that

would be going to schools that now are enrolling only

Negroes.

So, I don’t know, but my concept of neighborhood

school would be that you would go to the school near

est your home, provided that due account were given

to the utilization of facilities and safety factors. That,

I believe, is a legitimate conception of a neighborhood

school, and if that were followed in this community I

think the lines could be, as I said before, much dif

ferent from what they are. (R. 547-48).

He added that school zone lines following legitimate

criteria would automatically place large numbers of Negro

pupils in white schools and substantial numbers of white

pupils in Negro schools (R. 548).

He agreed with Mr. Neuwein that the continued assign

ment of teachers on the basis of race is an educational

handicap to all students, both because the racial standard

makes it more difficult to get the best person in each job

and because it tends to fix goals on race instead of the

educational job that must be done, thereby weakening the

educational process (R. 548-49). He indicated that research

shows desegregated faculties improve the educational

standards and general school morale and alter the tradi

tional racial image of the school (R. 549-50).

Dr. Lieberman blamed the Board’s plan for the fact

that those white pupils assigned to Negro schools chose

1 6

to leave the school system or to change their residences

(R. 562). He said that when very few white pupils are as

signed to a Negro school, they can be expected to move

(R. 562). Moreover, he stated that school board policies

are crucial to the racial composition of the schools. Thus,

the plans should be drawn so as not to maximize segrega

tion, which he asserted occurs where a few white pupils are

assigned to a Negro school (R. 562-63).

4. Effect of State Action on Board’s Zone Lines

While the Board’s zone lines as drawn served to direct

most white pupils to white schools and virtually all Negro

pupils to Negro schools, a census taken by the Board

showed there were from 72 to 80 Negro children of school

age, including 32 eligible to enter the first grade in the Fall

of 1964, residing in white school zones (R. 160, 180-81,

608). But a series of official actions, all taken during the

Summer of 1964 by Coahoma County and the City of

Clarksdale, effectively removed almost every Negro fam

ily living north of the Illinois Central tracks (R. 381).

These actions were as follows:

(1) The City incorporated a sizeable area of land lo

cated north of elementary zone E-3A (see maps, R.

773, 795), excluding a cluster of Negro homes in

an area along Friar Point Road which is known as

“Tuxedo Park”. The city then purchased these

homes, allegedly for park purposes, had them torn

down and relocated the Negro residents south of the

Illinois Central railroad tracks (R. 323).

(2) The City by a 1964 ordinance (R. 68-70) de-annexed

two strips of land on East Second Street located

17

north of the Illinois Central Bailroad tracks and in

the southern portion of elementary zone E-3A (B.

328). As a result, Negro pupils residing in these

areas were rendered ineligible to attend City schools

(B. 333).

(3) The City and the County, ostensibly to aid in solv

ing parking problems, purchased areas near the

County jail in the central business district (elemen

tary Zone E-3A) for public parking lots (B. 335-36).

Houses occupied by Negroes in this area were torn

down (B. 181).

(a) T estim ony o f School B oard Attorney Luckett

Apxjellants called Board attorney Semmes Luckett to

testify as to his knowledge, and possible participation in,

the enactment of the July, 1964 zoning ordinance and the

property purchases which had the effect of purging virtu

ally all Negroes residing north of the Illinois Central Bail-

road tract (B. 312). Attorney Luckett was familiar with

the content and effect of the ordinance, although indicating

that he had read it for the first time only the day before

(B. 314). He said he could not recall whether or not he

had been present at any official or unofficial meetings of

the Mayor and City Commissioners regarding the ordi

nance (B. 315-19). He admitted that he had discussed the

matters treated in the ordinance with the Mayor and Com

missioners, but in his capacity as a member of the City

Planning Commission and not as school board attorney

(B. 320-21). He denied that the actions taken by the city

were on his recommendation, but admitted that he favored

the actions taken for various reasons which he maintained

had nothing to do with the school system.

18

For example, he had favored for many years city ac

tion to tear down the Negro housing in Tuxedo Park for

reasons of health (R. 327-28). He also was in agreement

with the de-annexation of the Negro residential sections on

East Second Street, just north of the Illinois Central Rail

road tracks (R. 328-29). He also recommended that the

city purchase property around the county jail where Negro

residences were located (R. 337-38), but is not certain

that it was his recommendation that led to the action. He

stated that much of the action had been planned under an

urban renewal project abandoned in 1961 (R. 340). At

torney Luckett said that he had assisted the Board in pre

paring the school zone lines contained in the plan (R. 343)

and knew that the recommendations which were adopted

in the city ordinance would reduce the number of Negroes

who were assigned to white schools (R. 345). He stated he

had not told the school board that his recommendations

would affect the amount of desegregation under the plan

(R. 347), but thought it “entirely possible” that the Board

knew (R. 347-48).11

(b ) T estim ony o f City C om m issioner B ell

One of the City Commissioners, Hudson F. Bell, Jr.,

testified (R. 352) that the July, 1964 ordinance, which an

nexed some areas and de-annexed others, was passed as

11 Attorney Luckett, who is acknowledged as the author of the

State’s Tuition Plan Law (R. 350) (under which some white pupils

assigned to Negro schools were able to withdraw from the public

schools, obtain tuition from the State and enroll in private segre

gated schools) believes that school desegregation is unavoidable,

but also believes that some “escape valve” is necessary for areas

with high percentages of Negroes such as Clarksdale (R. 348-49).

19

part of a city improvement project and conformed to an

urban renewal plan which had to be abandoned in 1961

because of the passage of a state statute (R. 368). The

project was later renewed with local funds obtained from

a sales tax ordinance. He conceded that nothing had been

done about the de-annexed areas for several years, as other

projects were deemed more important (R. 370). He said

the zoning ordinance was the result not of recommenda

tions by Attorney Luckett, but of the Planning Commis

sion, of which Luckett was a member at the time the

recommendations were adopted (R. 371).

Commissioner Bell denied any knowledge of the effect

the zoning ordinance would have on the Board’s desegre

gation plan (R. 372-73), but conceded that the action was

taken after the school suit was filed and after the slum

clearance project had lain dormant for the four years since

the urban renewal program had died. While stating that

revenue from the sales tax ordinance, passed in 1962, en

abled capital improvements to be made, Commissioner Bell

was not able to explain why the need for money had held

up the de-annexation program, since no funds were neces

sary for this purpose (R. 375-76, 378). He maintained that

the de-annexation resulted from the City’s inability to pro

vide the de-annexation areas with sewage facilities and that

the houses in the Tuxedo Park area were subsequently

purchased by the City and torn down because of their bad

condition (R. 388-89). The City and County need for the

property was given as the basis for the purchase of Negro

residential areas located near the County jail (R. 390-94).

Nevertheless, Commissioner Bell conceded that the ordi

nance had the effect of removing all Negroes living north

of the railroad tracks (R. 381) and that this was the only

20

action taken on slum housing, which is located throughout

the city (R. 396-98).

(c ) T estim ony o f City P lann ing C om m ission Chairman

The Board obtained testimony from the Chairman of

the City Planning Commission (R. 400), who sought to sup

port the position of the Board attorney and City Commis

sioner that the City action which removed the Negro resi

dents living north of the railroad tracks was not intended

to achieve this purpose and was done without knowledge of,

or regard to, the Board’s desegregation plan.

On cross examination, however, it appeared that, not

withstanding attempted justification of the zoning ordi

nance based on a desire to rid the area of substandard

housing, only the substandard housing located north of the

Illinois Central Railroad tracks was affected. Virtually all

housing either torn down or de-annexed had been occupied

by Negroes, while some substandard housing occupied by

whites in that area was permitted to stand (R. 414-15, 418-

20, Defs. Exh. 25). Moreover, it appeared that notwith

standing the Chairman of the Planning Commission con

tended that the housing affected by the ordinance had the

highest priority for action under the abandoned urban re

newal plan (R. 405-06), the ordinance also affected (by

de-annexation) the area along East Second Street, which

had been given the lower priority number of XI (Defs.

Exh. 26, pp. 52-55).

(d ) T estim ony o f Dr. Aaron H enry

Appellant and state NAACP leader Dr. Aaron Henry

(R. 425) said that the Board’s school zones and the City’s

2 1

zoning ordinance would prevent school desegregation. He

explained that the great majority of Negroes in Clarksdale

are day laborers or are employed in the farm system (R.

434), that the work is frequently sporadic and that the

pay is very low (E. 438). Negroes live in clearly recog

nizable areas of the city and generally reside in the school

zone areas serving Negro schools (E. 438-39). Housing for

Negroes ranges from very poor to fairly good (E. 440).

Dr. Henry stated that there are areas south of the railroad

tracks (particularly in zone E 2-A) which are just as

dilapidated as the demolished Tuxedo Park or the de-

annexed area along East Second Street (E. 440).

Dr. Henry, who is also the president of the local NAACP

and the only Negro pharmacist (R. 425), knows most of the

Negro residents of Clarksdale. He believes few, if any,

Negroes now live north of the Illinois Central Railroad

tracks (R. 441, 449). He said that he doubts that Negroes

have ever tried to move into the areas served by the

Kirkpatrick, Heidelburg and Oakhurst Schools because

of the mores and the customs of segregation in housing (R.

441). Dr. Henry, whose daughter seeks admission to a

public school on a desegregated basis (E. 441-42), believes

that present conditions in Clarksdale would prevent even

a freedom-of-choice-type desegregation plan from having

any effect in Clarksdale, because of the general opposition

to school desegregation of the white community (E. 442-43).

5. Opinion of the Court Below

The district Judge reviewed all the evidence then before

him in a lengthy Memorandum Opinion dated August 10,

1965 (R. 74-110). His conclusions may be summarized as

follows:

22

a. In conformity with this Court’s adoption of the De

partment of Health, Education and Welfare’s school de

segregation guidelines in Price v. Denison Independent

School District Board of Education, 348 F. 2d 1010 (5th

Cir. 1965), the desegregation rate was set so as to en

compass all grades by the 1967-68 school year (R. 74-75).

b. The court referred to several school desegregation

decisions which it interpreted as having held neighborhood

school zones a constitutionally permissible method of de

segregation if all pupils within the zone were required to

attend their assigned school and the boundaries of each

zone were drawn on a nonracial basis (R. 76-77). Utilizing

these principles in reviewing the validity of the zone lines

contained in the Board’s plan, the court determined that

the junior and senior high school zones and the elementary

zones located north of the Illinois Central railroad tracks

should be approved, despite the fact that there were few

Negroes residing in the area north of the tracks and few

whites living in the zones located south of the tracks. The

court found that the residential patterns “arise from racial

housing patterns which have developed over the years”

(R. 80). The court found that the railroad tracks were a

proper and reasonable natural boundary and that selection

of this boundary as a school zone line did not create the

racial housing patterns and therefore did not in any way

detract from the appropriateness of such a boundary (R.

80). As to the one white and four Negro elementary zones

located south of the Illinois Central tracks, the court indi

cated that it was not convinced that more efficient zone

lines could not be constructed (R. 91). The board was or

dered to reconsider its recommendations as to these

school zones, which were nevertheless to be placed into

operation on a temporary basis for the first semester of

23

the 1965-66 school year (E. 91-92). As to these zones, the

court stated that it lacked the educational expertise to make

a final determination, but it rejected the suggestions made

by appellants’ educational experts, although conceding both

men were “educationally and theoretically well qualified”

(E. 96). The court felt they lacked practical experience in

the operation of the Clarksdale schools (E. 96-97) and that

their philosophy showed a commitment to mixing Negro

and white pupils in a classroom (E. 99-100). The court

regarded as the basic issue in this case not whether actual

integration occurred, but whether pupils were dealt with

as individuals without regard to race (E. 97). In support of

this interpretation of the Supreme Court’s school desegre

gation decisions, the district court quoted Briggs v. Elliott,

132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955) and a number of appel

late court decisions based on the Briggs v. Elliott opinion.

c. The district court recognized and took measures to

correct several of the deficiencies in the administration of

Negro schools complained of by appellants, including

teacher salary scales, curricula, teacher-pupil ratios and

per pupil expenditure of public funds (E. 92-93). The

court ordered that all these deficiencies be corrected and

that greater expenditures in the Negro school be authorized

if necessary to bring these schools up to white school

standards.

d. The court found merit in appellants’ complaint that

teachers were assigned on a segregated basis, but deter

mined that, because teacher contracts had already been

issued for the 1965-66 school year, immediate relief would

create “unnecessary and serious problems”, justifying tem

porary deferral of the problem of faculty desegregation

(E. 95-96).

24

e. Reviewing the evidence submitted by appellants that

numerous official actions taken by city and county officials

had greatly decreased the number of Negroes eligible to

attend white schools, the court found no connection between

the board’s obligation to desegregate the public schools

and the official actions; these he found had been planned for

several years. Nor did the court see any problem in the

fact that the school board attorney was a member of the

Planning Commission which recommended all these mu

nicipal actions (R. 107). It viewed appellants’ evidence as

an effort to demonstrate a conspiracy between the defen

dants and the city and county agencies to frustrate deseg

regation efforts (R. 107), but rejected the argument as

unsupportable (R. 108-09).

Following its Memorandum Opinion, the district court

entered what it designated a final order, approving the high

school zones and the elementary zones located north of the

Illinois Central tracks as well as the pace of the desegrega

tion plan, adding requirements that all school facilities be

equalized and that students seeking courses not offered in

their assigned schools be given the right to transfer to

schools where such courses are offered (R. 114). The order

temporarily approved the school zones located south of the

Illinois Central tracks, but required reconsideration of these

zones by the board and a resubmission of zones “predicated

on efficient utilization of available school facilities on a

racially nondiscriminatory basis in accordance with sound

education principles” (R. 115-16).

The order further provided that, notwithstanding the ele

mentary subdistricts located north of the Illinois Central

tracks had been approved, the Board was free to revise

25

these boundaries if this was necessary to accommodate

changes in the elementary attendance zones located south of

the Illinois Central tracks. The order awarded costs to

appellants and retained jurisdiction of the case for addi

tional orders which might become necessary or appropriate

(E. 116-17).

On August 18,1965, appellants filed a motion to amend the

findings and judgment (B. 120-25), in which they pointed

out that the court’s August 10th order effectively denied

them relief. They supported this contention by pointing

out that the school zones as approved by the court effec

tively excluded Negroes from white schools, that under

such zones no desegregation had been effected in grades

one and two and that the evidence indicated that no de

segregation could be expected in the future. The motion

also sought reconsideration of the court’s view that the

Brown decision could be carried out by eliminating dis

crimination even though no integration resulted. Appel

lants cited this Court’s decision in Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 348 F. 2d 729 (5th

Cir. 1965), which rejected the teaching of Briggs v. Elliott

and, upon reexamination of the second Broum opinion,

concluded that it “clearly imposes on public school au

thorities the duty to provide an integrated school system.”

Appellants also maintained that the proof offered by their

expert witnesses clearly showed that the Board’s zone lines

violated generally accepted criteria for drafting school

boundaries and could be justified only as a means for main

taining segregation. On August 30, 1965, the district court

denied and overruled plaintiff’s motion (R. 126).

26

6 . The B oard’s R evised Zone Lines

In October, 1965, the Board submitted its revised plan for

the elementary attendance zones located south of the Illinois

Central tracks. The sole change recommended was that the

zone line dividing the white Eliza Clark school from the

Negro Myrtle Hall school be eradicated and that, effective

in September, 1966, all first and second grade pupils in the

combined zone be assigned to the Eliza Clark school and

all pupils in grades three through six be assigned to the

Myrtle Hall school (R. 129-31). Appellants promptly filed

objections to the revised plan (R. 136-4.0), contending that

there was no greater justification for retaining the zone

lines of the other elementary schools (R. 137) and that,

while the eradication of the line between the Myrtle Hall

and Eliza Clark zones appeared to have advantages from

an educational and desegregational standpoint, the practi

cal effect of assigning the 115 white children from Eliza

Clark with the approximate 415 Negro pupils from Myrtle

Hall would be that white parents would refuse to send their

children to the school and would move their residences to

areas north of the Illinois Central tracks where, as the

evidence shows, Negroes could not obtain housing (R. 137).

Appellants also objected to the Board’s request that the

revised zone plan not go into effect until September, 1966,

in view of the court’s approval of the zones for one semester

only (R. 138-39). Appellants further complained that the

Board had failed to report what action, if any, had been

taken to comply with that portion of the court’s August

10, 1965 order requiring utilization of all school facilities

(R. 139-40). Following a hearing on November 15, 1965,

the court on December 13, 1965 gave full approval to the

27

board’s revised plan and ordered it into effect for the 1966-

67 school year (R. 141-49).

Specifications of Error

The District Court erred in :

1. Refusing to hold that the Board, having established

and maintained a racially segregated school system, is con

stitutionally obligated to submit a desegregation plan which

actually disestablishes segregation patterns and eradicates

Negro and white schools.

2. Approving the attendance school zones contained in

the Board’s desegregation plan over objections that such

zones are both conformed to racial neighborhoods and de

signed to perpetuate segregated schools, and despite in

disputable evidence that:

a. Approval of such zones retains almost intact Negro

and white schools;

b. The approved zones do not satisfy generally accepted

criteria for school zones;

c. The zone lines are drawn to capitalize on pendente life

rezoning and relocation action by City and County

officials effectively removing large numbers of Negro

families from zones serving white schools;

d. The Board’s policy of school construction and school

additions fosters perpetuation of segregation;

e. The Clarksdale school system is readily adaptable to

zoning which effectively integrates the schools while

conforming to classical school zoning criteria;

28

f. Community conditions and pressures render inad

visable further delay in requiring an assignment pol

icy which actually disestablishes segregated schools.

3. Approving a gradual stair-step desegregation plan

in the absence of valid administrative factors justifying

further delay, notwithstanding Negro educational facilities

remain dramatically inferior.

4. Refusing to require the immediate submission of a

specific plan providing for the nonracial hiring and assign

ment of teachers and other faculty personnel.

29

A R G U M E N T

I.

Effectuation of the Brown Decision Bars the Board’s

Use of a Neighborhood School Assignment Policy to

Justify Its Failure to Eliminate Segregated Schools, Par

ticularly Where State Action and Community Custom

Combine to Maintain Neighborhoods on a Racial Basis.

This Court has now clearly held that school boards op

erating a dual system are required by the Constitution

not merely to eliminate the formal application of racial

criteria to school administration, but must by affirmative

action seek the complete disestablishment of segregation

in the public schools. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Sep

arate School District, 348 F. 2d 729, 355 F. 2d 865. As

succinctly stated in the first Singleton case, “ . . . the second

Brown opinion clearly imposes on public school authorities

the duty to provide an integrated school system.” 348

F. 2d 729 at 730, n. 5.

The record clearly shows that pupil assignment via the

zone lines submitted by the Clarksdale Board will not suffice

to effect any change in the traditionally segregated assign

ment patterns which the Brown decision, and this Court,

have held invalid and which the district court specifically

enjoined.

Even if the Board’s zone lines reflected traditional ad

herence to assigning each child to the neighborhood school

closest to his home, the Brown decision would necessitate

additional measures to bring about a desegregated school

system. This Court and other courts have frequently held

3 0

that if the application of educational principles and theories

results in the preservation of an existing system of imposed

segregation, the necessity of vindicating constitutional

rights will prevent their use. Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d

256 (8th Cir. 1960); Ross v. Dyer, 312 F. 2d 191, 196 (5th

Cir. 1963); Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington,

Virginia, 324 F. 2d 303, 308 (4th Cir. 1963).

The Sixth Circuit, reviewing evidence that school zone

lines had been drawn so as to preserve a maximum amount

of segregation, in Northcross v. Board of Education of City

of Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964), held not only

that the burden of proof rested with the school board to

demonstrate that challenged zone lines were not drawn to

preserve a maximum amount of segregation, but added:

Where the Board is under compulsion to desegregate

the schools (1st Brown case, 347 U. S. 483) we do not

think that drawing zone lines in such a manner as to

disturb the people as little as possible is a proper

factor in rezoning the schools. 333 F. 2d at 664. See

also Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsborough,

Ohio, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956).

In this case, the Board’s commitment to the neighborhood

school policy appears less than convincing when it is con

sidered that, prior to this suit, pupils were assigned to

schools much further than those located closest to their

homes in order to comply with the segregated system. Ex

cept for those grades now covered by the Board’s plan,

pupils are still assigned on the basis of race, with the re

sult that many pupils are required to travel past schools

to which, but for their color, they would have been routinely

assigned. Thus, for a full decade after the Brown decision,

31

Board assignment policy required violation of the neigh

borhood school principle to effect segregation. Now the

Board opposes any departure from assignment on a strict

neighborhood basis which would possibly alter segregated

patterns.

In addition, the Board’s zones are obviously drawn

with regard to the racial boundaries in the community.

Appellants’ experts testified that the lines did not comport

with generally accepted zoning criteria (R. 459, 533) and

suggested alternate lines which would have both complied

with educational criteria and effected integration of the

Clarksdale schools (R. 479, 543). Some of the Board lines

requiring many Negro pupils to travel substantial dis

tances to overcrowded Negro schools, while white schools

located closer to their homes are underutilized, are in

genious : e.g., the use of the Illinois Central Railroad track

(the major racial dividing line in Clarksdale) as the sole

zone boundary for high schools and the key elementary

school zone boundary, even though the railroad tracks are

amply dotted with safe underpasses, and the board, prior to

the desegregation order, directed during the 1963-64 school

year 1,100 pupils to schools requiring the crossing of the

Illinois Central tracks and 639 during the 1964-65 school

year (R. 538). Others are ingenuous, particularly the east

ern zone line of the Eliza Clark School, which faithfully

follows Wilson Avenue (a traditional racial boundary with

Negroes living on the east side and whites on the west side

of the street), even when that street narrows to a grassy

field (R. 463). All may accurately be categorized as part

of a scheme which deprives Negro pupils of both their

constitutional right to attend schools administered on a

nonracial basis, Cooper v. Aaron, 358 TJ. S. 1, 17 (1958),

32

and their right, clear even prior to Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), to equal educational facili

ties. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950).

While the Board altered the most flagrantly gerry

mandered elementary zone line, the line between Zone E1C,

the Eliza Clark white elementary school, and Zone E1B,

the Myrtle Hall Negro elementary school (R. 666-67), even

this action was taken with knowledge based on experience

that, at least during this transitional period, Clarksdale’s

white pupils will not attend a predominantly Negro school.

The Board’s use of Wilson Avenue, an unpaved road

little used for travel hut generally acknowledged as a

long established racial dividing line, typifies the motiva

tions behind the Board’s construction of all its zone lines.

The elimination of that line after the district court refused

to approve it and the consolidation of the Clark and Hall

zones with a resulting Negro-white ratio so uneven as to

almost invite parents to withdraw their children from the

public schools reflects the Board’s intention to substitute

form for substance in the school desegregation process.12

12 In interrogatories served on the Board after its revised plan

was announced, appellants, noting- that the combined zones would

consolidate schools with 415 Negro pupils and only 115 white

pupils, inquired: “Under such circumstances and based on the

Board’s experience with the reluctance of white parents to permit

their children to attend schools with Negroes, particularly where

the Negro student body constitutes a majority, what plans or other

action has the Board undertaken to maintain the stability of the

community in Zone El-C [the combined zone] and prevent white

parents from moving or enrolling their children in private schools”

(R. 191). The Board responded :

These defendants have neither the power nor authority to

prevent anyone from moving from where he or she lives. Nor

do they have the power or authority to prevent any parent

from enrolling his or her child in a private school (R. 196).

33

The district court’s acceptance of the Board’s revised

plan reflects that court’s failure to grasp the settled prin

ciple that schemes which technically approve desegregation

but retain the school system in its dual form must be struck

down. Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683 (1963);

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County,

377 U. S. 218 (1964); Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir.

1960); Houston Independent School District v. Ross, 282

F. 2d 95 (5th Cir. 1960).

Appellants do not here seek the type of relief sought in

cases involving school segregation not shown to have re

sulted from officially sponsored and supported state action.13

Nor does this case, as indicated above, raise merely the

issue apparently presented in Gilliam v. School Board of

City of Hopewell, Virginia, 345 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1965),

reversed on other grounds, sub nom. Bradley v. School

Board of City of Richmond, 382 U. S. 103 (1965), of the

validity of school zone lines drawn in accordance with gen

erally accepted criteria but resulting in only token de

segregation. In this case the issue is clear and settled.

13 The right to such relief has been sustained in B ooker v. B o a rd

o f E d u c a tio n o f P la in fie ld . 45 N. J. 161, 212 A. 2d 1 (1965);

B alaban v. R u b in , 40 Misc. 2d 249, 242 N. Y. S. 2d 974 (Sup. Ct.

1963) , rev’d, 20 A. D. 2d 438, 248 N. Y. S. 2d 574 (2d Dept.),

aff’d, 14 N. Y. S. 2d 193, 199 N. E. 2d 375 (1964), cert, denied,

379 U. S. 881 (1964), 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 690; M orean v. B o a rd

o f E d u c a tio n o f M ontcla ir, 42 N. J. 237, 200 A. 2d 97, 9 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 688 (1964); Jackson v. P asadena School B oard , 31 Cal.

Rptr. 606, 382 P. 2d 878, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 924 (1963); B locker

v. B oard o f E d u c a tio n o f M anhasset, 226 F. Supp. 208 (E. D. N. Y.

1964) ; B arksda le v. S p rin g fie ld School C om m ., 237 F. Supp. 543

(D. Mass. 1965), vacated without prejudice, 348 F. 2d 261 (1st

Cir. 1961) ; and denied in B e ll v. School C ity o f G ary, In d ia n a , 213

F. Supp. 819 (N. D. Ind. 1963), aff’d, 324 F. 2d 209 (7th Cir.

1963), cert, denied, 377 U. S. 924 (1964), and D ow ns v. B o a rd o f

E d u c a tio n o f K ansas C ity , K ansas, 336 F. 2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964),

cert, denied, 380 U. S. 914 (1965).

34

A school board under injunction to desegregate does not

comply by assigning pupils according to zone lines which

reinforce rather than disestablish traditionally segregated

schools. If the contrary were true, then, as the Fourth

Circuit said in invalidating Prince Edward County’s tui

tion grant plan as a scheme to evade school integration,

appellees would “have indeed accomplished a remarkable

feat, stultifying a decade of judicial effort to bring about

compliance with Brown v. Board of Education. But the

label applied to these . . . . schools cannot blind courts, or

anyone else, to the realities.” Griffin v. Board of Super

visors, 339 F. 2d 486 (4th Cir. 1964).

35

II.

Actions by City and County Officials to Effectively

Remove Virtually All Negroes From White School Zones

Do Not Relieve the Board of Its Constitutional Obliga-

tin to Desegregate the Schools.

Despite the Board’s efforts to construct its zones to

contain pupils of one race, a substantial number of Negro

families lived in four areas located north of the Illinois

Central Railroad tracks as of March, 1964, when this suit

was filed. Two groups lived just north of the tracks on

East Second Street; a third group lived near the County

Jail and a fourth resided in a section just north of the

City boundary in an area named Tuxedo Park. Due to

intervening action by city officials of Clarksdale and Coa

homa County, none of the children of these families are

now eligible to attend white schools. A zoning ordinance,

enacted in July, 1964 by the City of Clarksdale, de-annexed

the property on East Second Street where the Negroes

lived; the City and County purchased and demolished the

homes located near the County Jail; and the City pur

chased and demolished the homes in Tuxedo Park, after

annexing adjoining territories containing white residences.

While the Board denies any knowledge of the City and

County action, and city officials maintain that the ordi

nance was not intended to affect school desegregation, the

testimony shows that of all the reasons given (desire to

clear dilapidated housing, to acquire needed property and

exclude areas where no sewage lines can be provided), the

real reason for pushing through in a few months measures

which had lain dormant for years was the removal of Negro

residents from areas served by white schools. See Taylor

36

v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181,

192 (8. D. N. Y. 1961); cf. Gomillion v. Lightfool, 364 U. S.

339 (1960).

Appellants introduced evidence that the Board attorney

was a member of the City Planning Commission and not

only had knowledge of the changes but had recommended

some of them. Other school officials also conceded that they

were aware of the zoning changes and governmental pur

chases which effectively removed virtually all Negroes

living in school zones serviced by white schools. Appellants

did not, as the District Judge suggests (R. 107), introduce

this evidence to prove a conspiracy between the school

board and the City and County officials or to show that

school officials had offered perjured testimony. Rather,

they sought to show that the Board was aware of the gov

ernmental actions, all of which directly affect their general

obligation under the Constitution and their specific obliga

tion under two Federal court orders to desegregate the

schools, and passively accepted it. Appellants reject the

Board’s contention that the matter was beyond their control.

For example, pupils uprooted by the City and County could

have been offered the right to attend the school in the

zone of their former residence, thereby permitting pupils

to cross its zone lines to obtain a desegregated education;

as it is now, crossing of zone lines is presently required

in order to better utilize segregated schools (R. 701, 704,

707).

The Board’s obligation is clear. This Court has already

indicated it would condemn school zone lines drawn to re

flect patterns of segregation caused by housing ordinances.

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach, Fla.,

258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958). More recently, in Powell v.

School Board of the Oklahoma Public Schools, 219 F. Supp.

37

427 (W. D. Okla. 1963), a district court noted the strong

connection between housing and school segregation and de

termined that the results of past patterns of housing segre

gation must be dealt with by the school board. The court

stated:

The patrons of the School District had lived under a

dual system and the children’s residential areas were

fixed by custom, tradition, restrictive covenants and

laws. The Negro people had been segregated so com

pletely in their residential pattern that it was difficult

to determine what way, method and plan and what pro

gressive plans should be adopted and carried out in

the future.

Two years later, in Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma

Public Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971, 980 (W. D. Okla. 1965),

the court ordered the school board to take affirmative action

to integrate the system, holding:

The validity of defendant Board’s action in rezoning

its public schools must be judged not only in the light

of the result (more than 90% of the system’s schools

remained virtually all Negro or all white), but also with

regard to the residential patterns in Oklahoma City,

established by statute, and by restrictive covenant, and

maintained at present by various discriminatory cus

toms and practices which effectively limit the area

where Negroes live to easily definable areas. To draw

school zone lines without regard to these residential

patterns is to continue the very segregation which

necessitated the rezoning action, and requires judicial

condemnation of the procedure. Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U. S. 356.

38

While speaking in a different context, Judge J. Skelly

Wright has taken a clear position that school boards must

consider residential segregation in order to prepare zone

lines which are constitutionally valid.

Where state policy expressed by its several agen

cies lends itself to, and leads toward, segregated

schools, the responsibility of the state is plain. For

example, where state policy with reference to hous

ing or state encouragement of private racial cove

nants in housing leads to residential segregation, and

the school board uses the neighborhood plan in mak

ing pupil assignments, the school segregation that re

sults is clearly the responsibility of the state. Certainly

the state will not be allowed to do in two steps what

it may not do in one.14

It is therefore irrelevant whether appellee school officials

were parties to creating the identifiable racial patterns

that have existed for a long time in Clarksdale or to carry

ing out the official actions in the Summer of 1964 that

completed this segregation. Housing segregation exists,

and the Board may not close its eyes to this reality and

may not simply duplicate the segregation housing patterns

in the schools. This in effect is what results when a Board

faced with this problem adopts the policy as proclaimed

by the Superintendent at the November, 1965 hearing on

the revised plan:

The School Board is disregarding totally the racial

characteristics of the people and is simply proposing

these zones as being the best for the children and

14 Wright, P u b lic School D esegrega tion: L ega l R em ed ies fo r

D e F acto S eg reg a tio n , 40 N. Y. U. Law Rev. 285, 295 (1965).

39

patrons of this school district, and racial considera

tions are just simply out the window (R. 672).

The Board’s duty is not at this late date to become color

blind, but to draw school zone lines that will create inte

grated schools in so far as is practicable and consistent with

sound educational practice. Dowell v. School Board of Okla

homa City Public Schools, supra; Kier v. County School

Board of Augusta County, 249 F. Supp. 239, 244 (W. D.

Va. 1966).

III.

The Board’s Plan Falls Short of This Court’s Stand

ards of Acceptable Pupil and Teacher Desegregation.

In Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348

F. 2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965), this Court adopted the U. S.

Office of Education’s “Statement of Policies for School De

segregation under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 (April, 1965)” as its minimum desegregation stand

ard. In March 1966, its “Revised Statement of Policies for

School Desegregation” was issued, which is no less relevant

to judicial appraisal of school plans. See Bradley v. School

Board of Richmond, 382 U. S. 103 (1965); Singleton v. Jack-

son Municipal Separate School District, 355 F. 2d 865 (5th