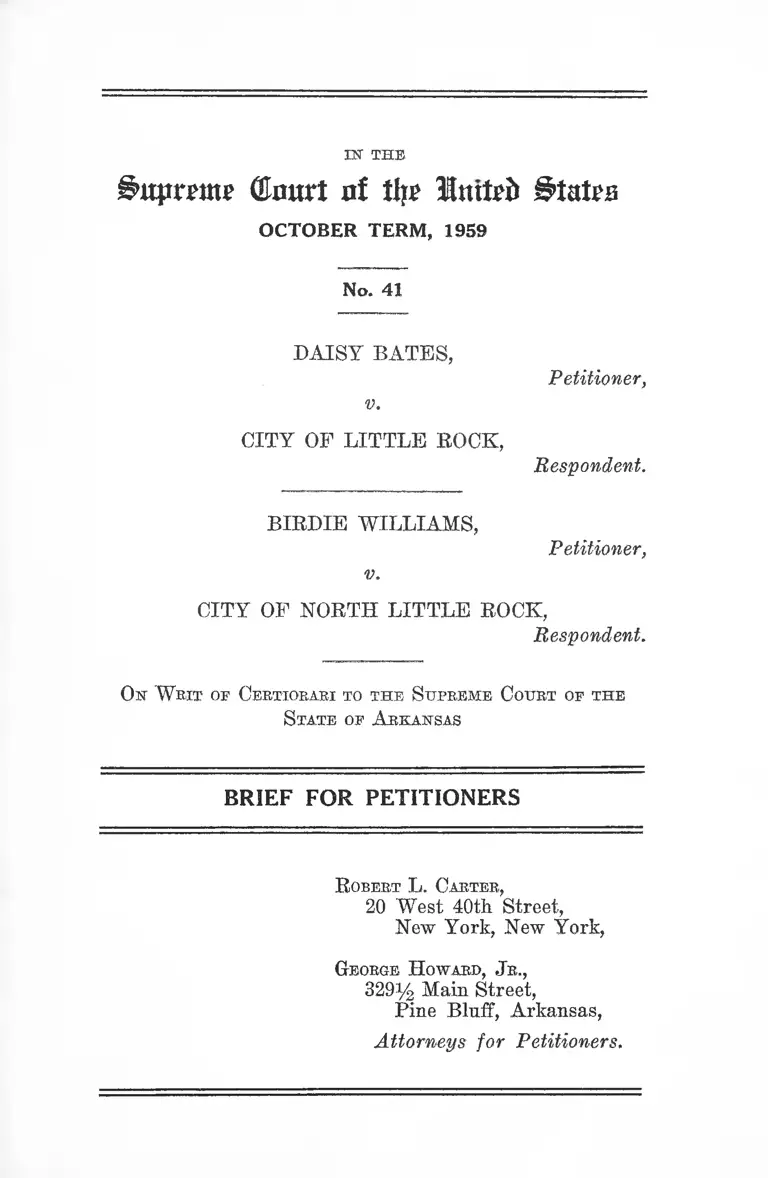

Bates v. City of Little Rock Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

September 17, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bates v. City of Little Rock Brief for Petitioners, 1959. cabac9e7-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/470f3ce1-210d-4bb3-9579-3e10fc9d91f1/bates-v-city-of-little-rock-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Copied!

1ST THEiutpmtte (Emart of % Intfri* i ’tatpfi

OCTO BER TERM , 1959

No. 41

DAISY BATES,

v.

CITY OF LITTLE BOCK,

BIRDIE WILLIAMS,

v.

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Petitioner,

CITY OF NORTH LITTLE ROCK,

Respondent.

O s W hit op Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the

S tate op A rkansas

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

R obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

George H oward, J r.,

329^ Main Street,

Pine Bluff, Arkansas,

Attorneys for Petitioners.

I N D E X

PAGE

Jurisdiction ............................................................... 1

Question Presented .................................................. 2

Statement .................................................................. 2

The Ordinances Involved.......................... 5

Summary of Argument............................................. 8

Argument ..................................................... 11

I. N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama Controls Decision Here 11

II. Unwarranted Interference With the Free Exer

cise of Bights of Freedom of Speech and of

Association Is Here Involved ....................... 13

The Interference Effected Cannot Be Sus

tained on the Ground That It Is a Part of

a Long State Tradition.................................... 13

The Occupation License Tax Ordinances In

volved Here, With Their Manifold Amend

ments, Have No Application to the Activities of

a Non-Profit Membership Organization Whose

Primary Objectives and Principal Activities

Are Directed Towards the Improvement of the

Status of Negro Citizens ............................... 15

Even Assuming Arguendo That These Ordi

nances Could Be Validly Applied Here, the Re

quirement That the Names of Members and

Contributors Be Disclosed to City Officials and

Be Subject to Public Inspection Bears No Rea

sonable Relationship to A. Lawful and Effective

Exercise of the Municipal Taxing Authority,

Which Is the Purported Purpose of These

Regulations ............................................. 18

III. The Ordinances Are Actual And Effective

Interferences With the Freedom of Associa

tion and Not A Mere Abstract Impairment of

Constitutional Rights ...................................... 22

Conclusion ................................................................ 24

11

Table of Cases

PAGE

Aaron v. Cooper, 358 U. S. 1, 3 L. ed. (Adv. pp. 3, 16) 11, 23

American Communications Association v. Douds, 339

U. S. 382 ............................................................... 9,12

Barenblatt v. United States, 360 U. S. 109.............. 9,12

Berry v. Hope, 205 Ark. 1105, 172 S. W. 2d 922 (1943) 15

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (E. D. S. C. 1957),

vacated and remanded, 354 U. S. 933 ...................... 23

Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S, 6 3 ........................... 9

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ............................. 9

First Unitarian Church v. Los Angeles, 357 U. S.

545 ......................................................................... 9,12

Ft. Smith v. Midland Valley R. Co., 156 Ark. 479,

246 S. W. 842 (1923) ............................................. 15

G-arner v. Board of Public Works, 341 U. S. 716__ 12,14

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Commit

tee, 360 U. S. 919 .................................................. 23

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233 ......... 9, 21

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U. S. 460 ................ 9,12

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105..................9, 15, 21

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S, 449 . . .2, 5, 8,10,11,12, 23

N.A.A.C.P. v. Arkansas, es rel. Bruce Bennett, At

torney General, 360 U. S, 909 ................................ 23

N.A.A.C.P. v. Bennett, 360 U. S. 471 ....................... 23

N.A.A.C.P. v. Committee on Offenses Against the

Administration of Justice, 358 U. S. 40 ............. 23

N.A.A.C.P. v. Harrison, 360 U. S. 467 .................... 23

N.A.A.C.P. v. Williams, 359 U. S. 550 .................... 23

Newark v. Edwards, 208 Ark. 276, 185 S. W. 2d 925

(1945) 15

1U

PAGE

Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S. 344................................ 23

Shelton v. McKinley, — F. Supp. — (E. D. Ark. June

8, 1959) ....................................................... 23

Speiser v. Randall, 357 IT. S. 513.............................9,12,17

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 ................................ 11

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 .............. 9,10,11

Talley v. Blytheville, 204 Ark. 746, 164 S. W. 2d 900

(1942) .................................................................... 15

Texarkana v. James & Mayo Realty Co., 187 Ark. 764,

62 S. W. 2d 42 (1933) ............................................... 15

Texarkana v. Taylor, 185 Ark. 1145, 51 S. W. 2d 856

(1932) .................................................................... 15

Thomas y. Collins, 323 U. S. 516................................ 9

United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 4 1 ....................... 9

Uphaus v. Wyman, 360 U. S. 7 2 ................................ 9,12

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 148 ....................... 9,12

IN' THE

(Emtrt nf tire United States

OCTO BER TER M , 1959

No. 41

------------------------------------- 0 — ----------- -----------------

D asey B ates, et ah.,

v.

Petitioners,

City of L ittle B ock, et al.,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to the S upreme Court of the

S tate of A rkansas

----- —--------- o-------------------

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

The opinion of the Supreme Court of the State of

Arkansas (R. 66-77) is reported at 319 S. W. 2d 37. The

opinion was from a divided court with Justices Holt and

Smith dissenting.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the court below was entered on Decem

ber 22, 1958 (R. 77, 78). Rehearing was denied on January

19, 1959, with the mandate being stayed pending the filing

and disposition of a petition for writ of certiorari in this

Court (R. 78, 79). The petition was filed on March 13,1959,

and was granted on May 18,1959 (R. 80). The jurisdiction

of this Court rests on Title 28, United States Code, Section

1257(3).

2

Question Presented

Whether Ordinance No. 10,638, an amendment to Ordi

nance No. 7444 governing the payment of an occupation

license tax levied for the privilege of doing business within

the city of Little Bock, and Ordinance No. 2683, an amend

ment to Ordinance No. 1786 governing the payment of an

occupation license tax levied for the privilege of doing

business within the city of North Little Bock, under which

petitioners were tried and convicted because of their re

fusal to supply to city officials the names and addresses of

the members and contributors of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People in the munici

palities involved, are inconsistent with the guaranty of

freedom of association and of privacy in associational

relationships secured against state encroachment by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States?

Statement

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, as this Court knows from prior litigation,

consists of a national organization, which is incorporated

under the laws of the State of New York as a non-profit

membership corporation, and local affiliates, which are

independant unincorporated associations with membership

in the local affiliates being equivalent to membership in the

national organization. See N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357

U. S. 449.

Petitioners Bates and Williams are members of the local

affiliate of the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People in Little Bock and in North Little Bock,

respectively. Each is custodian of the membership list of

the local organization to which she belongs, and petitioner

Williams is President of the N.A.A.C.P. Branch in North

Little Bock.

3

Ordinance No. 10,638 of Little Rock and Ordinance No.

2638 of North Little Rock are identical. They are the

progency of the Attorney General of Arkansas. They are

popularly known as the “ Bennett” ordinances and are so

designated in the opinion of the court below (R. 66). Each

ordinance requires that any organization operating within

the municipality in question must supply to the City Clerk

upon request and within a specified time (1) the official

name of the organization; (2) its headquarters or regular

meeting place; (3) the names of the officers and their

salaries; (4) the purpose of the organization; (5) a state

ment as to dues, assessments and contributions paid, by

whom and when paid, together with a statement reflecting

the disposition of the funds and the net income; (6) and an

affidavit indicating whether the organization is subor

dinate to a parent organization and the latter’s name. The

ordinances specifically provide that all information fur

nished shall be public and subject to inspection during rea

sonable office hours (R. 29-31, 37-38).

A demand was made on petitioner Bates for the afore

said information in respect to the N.A.A.C.P. in Little Rock,

and on petitioner Williams in respect to the N.A.A.C.P. in

North Little Rock. In each instance, substantially all the

information was furnished except the names of members

and contributors.

The Little Rock and the North Little Rock Branches of

the N.A.A.C.P. advised the city council by letter, through

their respective Presidents, of their official name, their place

of meetings and the names of their officers, all of whom

are unsalaried. The Articles of Incorporation of the parent

organization were quoted as follows:

. . . voluntarily to promote equality of rights

and eradicate caste or race prejudice among the

citizens of the United States; to advance the interest

of colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suf

frage; and to increase their opportunities for secur-

4

ing justice in the courts, education for their children,

employment according to their ability, and complete

equality before the law. To ascertain and publish

all facts hearing upon these subjects and to take any

lawful action thereon; together with any kind and

all things which may lawfully be done by a member

ship corporation organized under the laws of the

State of New York for the further advancement of

these objects.

for a description of aims and purposes. It was stated that

each local affiliate had been chartered and organized in

accord with those purposes and was seeking to effectuate

the stated objectives within its community. The specific

information requested as to finances was not given, but a

statement showing total receipts, total expenditures and.

the balance on hand was furnished. The requisite affidavit,

to the effect that the organization was an affiliate of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, a New York corporation, was filed.

The anti-N.A.A.C.P. climate in the State, a belief that

public identification of members and contributors might

subject them to harassment, economic reprisals and bodily

harm, and a claim of a constitutional privilege under both

the federal and state Constitutions were cited as the bases

for the refusal to disclose the names and addresses of

members and contributors and any information leading to

their ascertainment. Copies of the Constitution of the

national organization and of the Constitution and By-laws

for Branches were enclosed (R. 25-28, 40-43).

Each petitioner was tried and convicted for a violation

of the ordinance in question in the Municipal Court of her

respective community. Mrs. Bates was fined $100.00 and

Mrs. Williams was fined $25.00. On appeal to the Circuit

Court of Pulaski County each was tried de novo, again

convicted and each fined $25.00 (R. 25, 65). The ordinances

were held valid, and claimed infringements of constitu

tional rights were held to be without substance (R. 25, 65).

5

The cases were consolidated in the Supreme Court of

Arkansas, and the sentences and convictions upheld by a

divided court (R. 77). In its opinion the court below sought

to distinguish the instant litigation from this Court’s holding

in N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 IT. S. 449. It concluded that

here the intrusion on freedom of speech and association

was a “ mere incident to a permissible legal result” (R. 75).

As such, the ordinances were held to impinge in no way

upon the safeguards provided under the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

The Ordinances Involved

Arkansas Statutes, 1947, Section 19-4601 authorizes

municipalities to levy a tax on any person, firm, individual

or corporation engaging in any “ trade, business, pro

fession or calling” within their territorial limits. The

pertinent statutory provisions follow:

Hereafter any city council, board of commis

sioners of board of aldermen . . . shall have the

power to enact . . . an ordinance . . . requiring any

person, firm, individual or corporation who shall

engage in, carry on, or follow any trade, business,

profession, vocation or calling, within the corporate

limits of such city . . . to take out and procure a

license therefor and pay into the city or town treas

ury before receiving same, such a sum or amount

of money as may be specified by such ordinance or

ordinances for such license and privilege. The city

council. . . shall have the right to classify and define

any trade, business, profession, vocation, or calling

and to fix the sum or amount any person, firm,

individual or corporation shall pay for such license

required for the privilege of engaging in, carrying

on, or following, any trade, business, vocation, or

calling, based on the amount of goods, wares or

merchandise carried in stock in any business, or

the character and kind of trade, business, profession,

6

vocation, or calling, but no classification shall be

based upon earnings or income and shall have the

full power to punish for violation of such ordi

nance . . .

Pursuant to these provisions, the city of Little Rock

enacted Ordinance No. 7444 (R. 29) and North Little Rock

enacted Ordinance No. 1786 (R. 37) which established an

annual occupation license tax on various businesses, occu

pations and professions.

Ordinance No. 10,638 of Little Rock and Ordinance No.

2683 of North Little Rock are the latest in a long series

of amendments to these basic privilege license tax enact

ments. Ordinance No. 10,638 enacted by the City of Little

Rock, which is identical in terms to Ordinance No. 2683,

provides as follows:

W hereas, it has been found and determined that

certain organizations within the City of Little Rock,

Arkansas, have been claiming immunity from the

terms of Ordinance No. 7444, as amended, govern

ing the payment of occupation licenses levied for

the privilege of doing business within the city, upon

the premise that such organizations are benevolent,

charitable, mutual benefit, fraternal or non-profit,

and

W hereas, many such organizations claiming the

occupation license exemption are mere subterfuges

for businesses being operated for profit which are

subject to the occupation license ordinance; Now,

T herefore, B e I t Ordained by the City Council oe

the City oe L ittle R ock, A rkansas :

Section 1. The word “ organization” as used

herein means any group of individuals, whether in

corporated or unincorporated.

S ection 2. Any organization operating or func

tioning within the City of Little Rock, including but

not limited to civic, fraternal, political, mutual bene

fit, legal, medical, [fol. 59] trade, or other organ

ization, upon the request of the Mayor, Alderman,

7

Member of the Board of Directors, City Clerk, City

Collector, or City Attorney, shall list with the City

Clerk the following information within 15 days after

such request is submitted:

A. The official name of the organization.

B. The office, place of business, headquarters or

usual meeting place of such organization.

C. The officers, agents, servants, employees or

representatives of such organization, and the sal

aries paid to them.

D. The purpose or purposes of such organiza

tion.

E. _ A financial statement of such organization,

including dues, fees, assessments and/or contribu

tions paid, by whom paid, and the date thereof,

together with the statement reflecting the disposi

tion of such sums, to whom and when paid, to

gether with the total net income of such organ

ization.

F. An affidavit by the president or other offi

ciating officer of the organization stating whether

the organization is subordinate to the parent or

ganization, and if so, the name of the parent organ

ization.

S ection 3. This ordinance shall be cumulative

to other ordinances heretofore passed by the City

with reference to occupation licenses and the col

lection thereof.

[fol. 60] S ection 4. All information obtained pur

suant to this ordinance shall be deemed public and

subject to the inspection of any interested party at

all reasonable business hours.

Section 5. Any section or part of this ordinance

declared to be unconstitutional or void shall not

affect the remaining sections of the ordinance, and

to this end the sections or subsections hereof are

declared to be severable.

8

S ection 6. Any person or organization who

shall violate the provisions of this ordinance shall

be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon con

viction thereof shall he fined in a sum not less than

$50.00 nor more than $250.00, and each day of viola

tion shall constitute a separate offense. The City

Council in the enforcement of this ordinance shall

have the power to see injunctive relief.

Section 7. It has been found and determined

by the City Council that certain organizations op

erating within the City of Little Bock have failed

to comply with the terms of Ordinance No. 7444, as

amended, governing the payment of occupation li

censes, and as a result thereof, needed revenue is

being lost, and the enactment of this ordinance will

provide for more efficient administration of such

ordi- [fol. 61] nance. Therefore, an emergency is

declared to exist, and this ordinance being necessary

for the preservation of the public peace, "health, and

safety, shall take effect and he in force from and

after its passage and approval.

Summary of Argument

Petitioners have been convicted and fined for violating

the municipal ordinances here involved, because of their

refusal to furnish to city officials the names and addresses

of N.A.A.C.P. members and contributors. Petitioners con

tend that these ordinances are invalid under the rationale

of N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 TJ. S. 449. Here, as there,

the enforced public identification of those associated to

gether in the N.A.A.C.P. constitutes an effective restraint

upon the free exercise of constitutional guarantees of

freedom of speech and association and is an unwarranted in

fringement upon the privacy of associational relationships.

The corrosive and stifling effect on freedom and privacy

which these ordinances accomplish cannot be justified under

any yardstick established in the decisions of this Court.

9

See Sweesy v. New Hampshire, 354 IT. S. 234; United States

v. Buniely, 345 IT. S. 41; Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 IT. S.

148; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516; Murdoch v. Pennsyl

vania, 319 U. S. 105; DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 IT. S. 353;

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 IT. S. 233.

No secret oath-bound organization committed to law

lessness is here involved, Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S.

63; nor are rights of freedom of speech and association

being asserted to accomplish an unlawful purpose. Hughes

v. Superior Court, 339 IT. S. 460. There is, moreover, absent

that problem of suspected subversion which has led this

Court to sustain inroads upon this area of personal liberty,

as a proper exercise of governmental right of self-preserva

tion, which, under other circumstances, would not be counte

nanced. See Uphaus v. Wyman, 360 IT. S. 72; Baren-

blatt v. United States, 360 U. S. 109. Nor is the situation

here presented one in which the infringement complained

of is a necessary incident to the valid exercise of govern

mental authority in another area. See, e.g., American Com

munications Association v. Douds, 339 U. S. 382. Cf. Speiser

v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513; First Unitarian Church v. Los

Angeles, 357 IT. S. 545. Indeed, there is no rationale which

can supply that compelling justification essential to the

validity of the provisions at issue. See Sweesy v. New

Hampshire, supra.

The ordinances are amendments to municipal privilege

license tax laws pursuant to which various commercial,

business and professional occupations are required to pay

a fee for the privilege of doing business. This authority

relates solely to commercial enterprises. There was no

showing below7 that the N.A.A.C.P. was engaged in any of

the occupational activities taxed, or that any demand had

been made upon the organization or its officers for the

payment of a tax. The record does reveal that the ordi

nances were enacted to find out what was going on in the

N.A.A.C.P., but mere curiosity would not seem to be suffi

cient warrant for curbing freedom of speech and associa-

10

tion or for invading that privacy of association which the

federal Constitution secures. In fact, there is no substan

tial relationship between the disclosures here sought and

effective exercise of the municipal taxing authority which

is the purported reason for the enactment of both ordi

nances.

The N.A.A.C.P. is a dissident organization, unpopu

lar in many areas in the United States, because its funda

mental purposes and aims are to eliminate enforced racial

segregation and to secure equal citizenship status for

Negroes. Movement towards those objectives has effected

a major upheaval in the complex of Negro-white relations

throughout the United States. Especially in the South

today is there fierce resistance to the changes in ideas and

customs which eradiction of racial discrimination neces

sitates. The N.A.A.C.P. is regarded as the major

enemy by those who would maintain the status quo in race

relations in the South, and its destruction is their primary

target. It was in this climate that these regulations were

enacted and petitioners convicted. The basic reason for

enacting and enforcing these ordinances in Little Rock

and North Little Rock was to frighten, intimidate and

coerce those who belong to the N.A.A.C.P., or who believe

in its objectives, into abandoning their ideas of equality

and activities in furtherance thereof—in short, to stifle

freedom of speech and association. The restrictive and

deadening effect on the free exercise of these freedoms

is clearly demonstrated in this record, without manifesta

tions of any compelling subordinating state interest, which

might conceivably justify this result. The ordinances

in question and petitioners’ convictions and fines there

under, therefore, cannot he squared with the principles

enunciated in the decisions of this Court. See N.A.A.C.P.

v. Alabama, supra; Sweesy v. New Hampshire, supra.

11

ARGUMENT

I

N .A .A .C .P . v. Alabam a Controls Decision Here.

The present litigation differs from N.A.A.C.P. v.

Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, only in minor and insignificant

particulars. In that case, a contempt adjudication based

upon a refusal to comply with a court order alleged to be

an invasion of freedom of speech and association was

involved. Here, convictions and sentences for refusal to

comply with the terms of municipal ordinances allegedly

in violation of those constitutional guarantees are before

this Court. In both instances, the interference complained

of concern the freedom and privacy of association^ rela

tionships of members and contributors of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Un

questionably, the constitutional proscription against state

encroachment on freedom of association is not affected

merely by the form in which the state’s prohibited action

is taken. See Aaron v. Cooper, 358 U. S. 1, 3 L. ed. (Adv.

p. 3, 16). In the Alabama case, the constitutional claim

was made by the organization on behalf of its members

and here, by custodians of the membership list as a defense

to criminal prosecutions, both on their own behalf and on

behalf of N.A.A.C.P. members and contributors.

Whatever question there may be concerning application

of the constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and

of association to a particular set of facts and circumstances

in a specific case, there is no doubt that the Fourteenth

Amendment prohibits governmental interference with these

freedoms and with individual privacy in their exercise,

absent a showing of some overriding and compelling state

justification for the intrusion. See Sweezy v. New Hamp

shire, 354 U. S. 234; Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313;

12

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, supra; Wieman v. Updegraff, 344

U. S. 148.

To give effect to the claimed right of freedom of speech

and of association raised here would not license a violation

of some important state policy, protecting or fostering

a legitimate societal interest. Cf. Hughes v. Superior Court,

339 U. 8. 460. The rationale which has sustained the

right of governments to take measures to meet problems

of subversion, see Uphaus v. Wyman, 360 U. S. 72; Ameri

can Communications Association v. Douds, 339 U. S. 382;

Garner v. Board of Public Works, 341 U. S. 716, "which

in a different context [would raise] constitutional issues of

the gravest character,” Barenblatt v. United States, 360

U. 8. 109, 128, has no present application. Nor is this a

valid exercise of state taxing authority in which encroach

ment on freedom of speech and of association is a necessary

and unavoidable incident. Cf. Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S.

513; First Unitarian Church v. Los Angeles, 357 U. S. 545.

On the contrary, these ordinances and the resultant con

victions now before this Court are simply attempts on the

part of city officials to liquidate the pressure for equal

citizenship rights for Negroes by seeking to resist and turn

back the momentum of our history, with its ever present

antipathy to racial discrimination, albeit often ambivalent

and tenuous, by suppressing the N.A.A.C.P. through the

exposure of its members and contributors to the hostility

of an adverse climate of public opinion.

The record fails to disclose any subordinating state

interest which would justify the interference and restric

tion which the ordinances effect. It is respectfully sub

mitted, therefore, that under the yardstick applied in the

decisions of this Court, these regulations are unconstitu

tional intrusions on freedom of association, and the con

victions thereunder must be set aside. See N.A.A.C.P. v.

Alabama, supra.

13

I 1

Unwarranted Interference With the Free Exercise

of Rights of Freedom of Speech and of Association

Is H ere Involved.

T h e In te rfe ren ce E ffected C annot Be S u sta in ed on th e

G round T h a t It is a P a r t o f a Long S ta te T rad itio n .

The Supreme Court of Arkansas seeks to justify these

provisions on the ground that the enforced disclosure of

organizational members is a requirement of long standing

in the statutory law of the State. Section 64-1302, Arkansas

Statutes, 1947, is cited to support this statement. That

statute provides:

Any association of persons desirous of becoming-

incorporated, under the provisions of this act

[§§ 64-1301-64-1308] shall file with the Clerk of the

Circuit Court and Recorder for the proper county

a copy of their constitution or articles of association,

and a, list of all the members, together with a petition

to said court for a certificate of incorporation under

the provisions of this act. (Emphasis added.)

In short, where a group of persons desires to incorpo

rate, it may do so provided certain information is given

to state officials, including a list of members of the group.

Section 64-1306, Arkansas Statutes, 1947, sets out

specific advantages which corporate status may bring. It

provides:

Any such corporation shall have power to borrow

or raise money necessary or convenient to the ac

complishment of the purposes of the association or

corporation and, from time to time, without limita

tion upon amount, draw, make, accept, indorse, ex

ecute, and issue promissory notes, drafts, bills of

exchange, warrants, bonds, debentures and other

negotiable and non-negotiable instruments and evi

dences of indebtedness and to secure the payment

14

of any thereof and the interest thereon hy mort

gage, pledge, conveyance or assignment in trust of

the whole or any part of the property of the asso

ciation or corporation whether at the time owned or

thereafter acquired; to sell, pledge, or otherwise

dispose of bonds or other obligations of the asso

ciation or corporation for its corporate purposes;

to cooperate with any government agency or agencies

whether national, state, county or municipal, or

with any business or private agency whatsoever in

carrying out the purposes herein contemplated; to

acquire by gift or in any other manner and to sell,

lease, mortgage, pledge, assign, transfer or other

wise dispose of lands or real property . . .

Such corporation and association shall have the

capacity of suing and being sued and is authorized

to do any and all things necessary, convenient, useful

or incidental to the attainment of its purposes as

fully and to the same extent as natural persons

lawfully might or could do, as principals, agents,

contractors, trustees or otherwise.

But the foregoing statutes have no bearing on the instant

litigation. The National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, the parent organization, is a New York

corporation. Neither the Little Rock nor the North Little

Rock N.A.A.C.P. Branches, which are unincorporated as

sociations, have sought to avail themselves of the privi

leges afforded by Sections 64-1302 and 64-1306. These

statutes require that an organization disclose its members,

if it desires to obtain those advantages which corporate

status affords. In exchange for these special privileges,

the relinquishment of the privacy of associational rela

tionships is exacted. But Cf. Mr. Justice Frankfurter’s

opinion in Garner v. Board of Public Works, supra at 724.

Disclosure is not compelled, it is purely optional.1 Thus,

petitioners submit, these statutory provisions furnish no

support for the restrictions here involved.

1 Moreover, it should be added, Section 64-1302 does not require

the filing with the Secretary of State a current list of members, but

only a list of those members at the time the incorporation is sought.

15

T h e O ccu p atio n L icense T ax O rd in an ces Involved

H ere , W ith T h e ir M anifo ld A m endm en ts, H ave No

A p p lica tio n to th e A ctiv ities of a N on-Profit M em

b ersh ip O rg an iza tio n W hose P rim ary O bjec tives

an d P rin c ip a l A ctiv ities A re D irec ted T o w ard s

th e Im provem en t o f th e S ta tu s o f N egro C itizens.

Section. 19-4601, Arkanas Statutes, 1947, and the oc

cupation license tax ordinances enacted thereunder, apply

to commercial enterprises. See Texarkana v. Taylor, 185

Ark. 1145, 51 S. W. 2d 856 (1932) (involving a tax on occu

pations, including attorneys-at-law); Texarkana v. James

S Mayo Realty Co., 187 Ark. 764, 62 S. W. 2d 42 (1933)

(involving a broker’s tax on persons engaged in the buying

and selling of real estate); Newark v. Edwards, 208 Ark.

276, 185 S. W. 2d 925 (1945) (involving a tax on meat mar

kets) ; Talley v. Blytheville, 204 Ark. 746, 164 S. W. 2d 900

(1942) (involving a tax on taxicab service).

A tax on interstate commerce was held invalid. See

Ft. Smith v. Midland Valley R. Co., 156 Ark. 479, 246 S. W.

842 (1923). And in Berry v. Hope, 205 Ark. 1105,172 S. W.

2d 922 (1943), an ordinance, requiring a license for the

house to house selling “ of goods, wares and merchandise

of any description,” as applied to the sale of religious

tracts by members of the Jehovah Witnesses, was held to

constitute an unlawful invasion of guarantees of freedom

of speech and of religion in accord with this Court’s decision

in Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105. Thus, Arkansas

decisional law expressly recognizes that the municipal tax

ing power authorized by Section 19-4601, Arkansas Statutes,

1947, is subject to limitations imposed by the provisions

of the federal Constitution.

Ordinance No. 7444 of Little Eock, as originally en

acted, applied to a variety of commercial enterprises rang

ing from advertising, abstract and title companies, billiard

and pool miniature companies, cobblers, florists, mattress

16

manufacturers to vending machine scales (Tr. 65).2 It

was first amended by Ordinance No. 7469 (Tr. 103,

106) which sought to clarify the various classifications of

the businesses affected. Ordinance No. 7475, the second

amendment, levied a tax on cleaning and pressing estab

lishments (Tr. 112); Ordinance No. 7483 affected U-Drive

cars (Tr. 114) ; Ordinance No. 7504, plumbing and gas

fittings (Tr. 117); Ordinance No. 7527, frozen food lockers

and public warehouses (Tr. 119); Ordinance No. 7538, air

plane sales and services (Tr. 121); Ordinance No. 7573,

interstate and radio broadcasting (Tr. 123); Ordinance

No. 7677, collecting agencies (Tr. 128); Ordinance No.

7803, parking lots (Tr. 130); Ordinance No. 7809 relieved

charitable organizations engaging in the occupations af

fected from the payment of the privilege tax (Tr. 132);

Ordinance No. 7876, washaterias (Tr. 134); Ordinance No.

7843, auditors and accountants (Tr. 136); Ordinance No.

7844, stage shows, vaudeville acts, etc. (Tr. 138); Ordinance

No. 7934, junk dealers (Tr. 142); Ordinance No. 7935,

coin operated radios (Tr. 144); Ordinance No. 8017, auc

tioneers (Tr. 146); Ordinance No. 8139, photographers (Tr.

148); Ordinance No. 8191, tree surgery (Tr. 154); Ordi

nance No. 8049, premium stamps (Tr. 158); Ordinance No.

8214, floor finishers (Tr. 161); Ordinance No. 8228, mobile

produce salesmen (Tr. 163); Ordinance No. 8236, street

cars and bus advertising (Tr. 167) ; Ordinance No. 8261,

display advertising (Tr. 169); Ordinance No. 7515, linen

and towel supply service (Tr. 171) Ordinance No. 8530,

bakeries and doughnut shops (Tr. 173); Ordinance No. 8531,

automobile dealers (Tr. 177); Ordinance No. 8554, portable

typewriters and small adding machines (Tr. 178); Ordi

nance No. 8568, sightseeing coaches (Tr. 179); Ordinance

No. 8980, the production of electricity (Tr. 188); Ordinance

No. 9014, the distribution and sale of natural gas (Tr. 191);

2 The “Tr.” citations here are to the original unprinted record

on file in the office of the Clerk of this Court.

17

Ordinance No. 9015, the Southwestern Bell Telephone

Company (Tr. 194); Ordinance No. 9125, meat inspection

(Tr. 199); Ordinance No. 9161, drive-in theatres (Tr. 205);

Ordinance No. 9162, television (Tr. 207); Ordinance No.

9241, pistols (Tr. 211); Ordinance No. 9243, municipal

owned auditoriums (Tr. 220); Ordinance No. 9306, profes

sional bondsmen (Tr. 225); Ordinance No. 9328, convales

cent nursing- homes (Tr. 251); Ordinance No. 9378 re

pealed Ordinance No. 9241 (Tr. 255); Ordinance No.

9406, the sale and transfer of pistols (Tr. 256); Ordinance

No. 9845, ice manufacturing (Tr. 262); Ordinance No. 10,063

repealed Ordinance No. 9125 with respect to meat inspec

tion (Tr. 264); Ordinance No. 10,167 amended Ordinance

Nos. 7476 and 9845 in respect to ice manufacturing (Tr.

266); Ordinance No. 10,270, automobile express business

(Tr. 268); Ordinance No. 10,495, the Midwest Video, Inc.

(Tr. 270); Ordinance No. 10,496, the Rowley United Thea

tres, Inc. (Tr. 276); and Ordinance No. 10,638, the present

amendment.

These provisions were squarely aimed at reaching all

the professional, commercial and business occupations

within the municipality. The tax is not automatic, and

before the city can require payment of the tax, there

must be a showing that the individual or organization

affected is engaged in one of the activities for wThich a

license is required. See Speiser v. Randall, supra. Thus,

here there must have been a showing (1) that the N.A.A.C.P.

was engaged in a business or commercial activity for

which a license is required; (2) that a claim for payment

of the tax has been made; (3) that an immunity based upon

the non-profit character of the organization was asserted.

Only then are the provisions of Ordinances No. 10,638 and

2638 conceivably applicable. None of these prequisities is

present in this record.

18

Even A ssum ing A rg u en d o T h a t T h ese O rd in an ces

Could Be V alid ly A p p lied H ere , th e R eq u irem en t

T h a t th e N am es of M em bers a n d C o n trib u to rs

Be D isclosed to C ity Officials a n d Be S u b jec t to

P u b lic Inspection B ears No R easo n ab le R e la tio n

ship to A L aw fu l an d E ffective E xercise of th e

M unicipal T ax in g A u th o rity , W h ich is th e P u r

p o rted P u rp o se of T h ese R egu lations.

The occupation license tax is either a flat tax on the

occupation affected, a pro rata tax upon stocks, goods

on hand or upon capacity of the establishment, or a per

capita tax upon the number of specialized employees. It

seems obvious, therefore, petitioners respectfully submit,

that the names of an organization’s members and contrib

utors have no bearing upon the effective enforcement of

the occupation tax ordinance, or upon whether the

N.A.A.C.P. is engaged in a taxed occupation, is a non

profit organization and exempt from the tax, or operating

for profit and subject to the tax.

The evidence in the record conclusively reveals that

these “ tax revenue measures” were principally intended

to interfere with the freedom of association of members

of petitioners’ organization.

Mr. Loy, sponsor of Ordinance No. 10,638, testified as

follows in respect to its purposes (R. 22-24).

A. The purpose of the ordinance and me being

Vice Chairman of the Finance Committee of Little

Rock, and the City being in a condition of very bad

financial strain, it was determined that if we could

strengthen the privilege tax ordinance it would bring

in the additional revenue the City needed and the

purpose back of the ordinance was strictly to develop

revenue.

Q. I take it that there had been evidence brought

before the City Council that there had been viola

tions of the privilege tax ordinance by organiza

tions! A. We have had in the City of Little Rock

in the past year numerous different organizations

that were formed, clubs, organizations and what-not.

19

It was thought that in many eases that many of

these organizations were not paying their proper

privilege taxes.

Q. Well, now, just two questions. I want to refer

specifically to Paragraph E of the ordinance. What

was the purpose of the requirement you made of

identifying the persons who paid dues, fees, assess

ments and/or contributions insofar as this would

strengthen the privilege tax ordinance and bring

in increased revenue for the City?

# # #

A. Under the State laws, any individual, company

or corporation or what have you that wants to sell

beer—if it happened to be in my Ward, I would

have to approve the approval of the beer license

before that person, firm or corporation would be

permitted to have a license in the City of Little

Rock. Not only that, but in doing that, we have

to determine who owns or belongs to the different

organizations from a felony standpoint and from

a gambling standpoint and consequently that para

graph in the ordinance was specifically to determine

whether any of the members or the individual, firm or

corporation was guilty of a felony or possibly

gambling or liquor violations or gambling violations

that had been previously done or would be done in

the future.

Q. In other words, as I understand your state

ment, Paragraph E of the ordinance applies only

to organizations that sell beer or sponsor gambling,

is that correct? A. There is no way to determine,

if you read the ordinance and where you have maybe

50 or 100 or several hundred individuals, firms or

corporations—to determine what the intent or what

the characterability of the people was unless you

had a complete list of who was involved.

Q. Would the list of names help you to know

whether or not they sold beer or gambled f A. The

Police Department has a pretty good idea of the

different people in Little Rock in the different

organizations, clubs and what have you.

Q. You have in Paragraph D of the Ordinance,

“ The purpose or purposes of such organization”—

I am reading from the ordinance? A. That’s right.

20

Q. As I understand your testimony, you need the

names and addresses of the people you request in

Paragraph E to determine whether or not they have

committed some felony or engaged in gambling!

A. If they had nothing to hide in any way, they

wouldn’t have any objection to going ahead and

answering the questions as put out in the ordinance

if they had nothing to hide.

Mr. Paul 0. Duke, sponsor of Ordinance No. 2683,

similarly described its purposes (R. 48-50):

Q. Mr. Duke, did you sponsor this Ordinance?

A. I did.

Q. Then you are quite familiar with the contents

of it? A. Fairly well.

Q. Now in the introductory clause of this Ordi

nance, it is stated that it was enacted for the purpose

of implementing your Privilege Tax Ordinance which

is No. 1786. Are you familiar with that Ordinance?

A. That is right, yes, sir.

Q. Also in your introductory clause of 2683 it is

stated that certain organizations have been claim

ing immunity to this Privilege Tax. Now, to your

knowledge, do you know whether or not a request

has ever been made on the North Little Rock Branch

of the NAACP for a Privilege Tax? A. Not that

I know of.

Q. I will further ask you, sir, in what way does

North Little Rock City Ordinance No. 2683 implement

your Privilege Tax Ordinance? A. Now, that is

a connection there that it was just trying to find

out if there was a privilege tax involved in this,

in your organization, the NAACP.

Q. Now, you further stated that you are familiar

with your Privilege Tax Ordinance which is 1786,

and I believe in that Ordinance you have a list of

the _ organizations and list of businesses that are

subject to that privilege tax, is that correct, sir?

A. Yes, sir, there is.

Q. Now, have you personally examined City Ordi

nance No. 1786 to determine whether or not this

organization is covered by this tax? A. Not com

pletely.

21

Q. And you voted on this measure 2683 before

you investigated 1786 to determine whether or not

this organization was subject to it! A. I did.

Q. Well, what did you find, sir! A. That this

was up to the discretion of the Ordinance to be

involved to see if there was privilege tax due the

City of North Little Rock.

Q. And I believe you stated that you are familiar

with the Privilege Tax Ordinance! A. I said to

some extent.

Q. To some extent. Then you don’t know

whether or not your privilege tax ordinance covers

this organization already, do you! A. I couldn’t

say.

Q. All right, sir. I would like for you to tell the

Court just in what way would the listing of the

official name of the organization, business place or

its meeting place, the names and addresses of con

tributors would implement your tax ordinance! A.

This was simply put in to see if there was other means

involved in your organization. We were not—we are

not acquainted with your organization whatsoever.

Q. Then you just wanted to find out what goes on

in the organization, is that right! A. That is right.

By our rights—

Q. Sir! A. By our rights we are asking that.

This testimony indicates that the municipalities pur

port to use their taxing authority in order to violate rights

of freedom of speech and association. This, petitioners

submit, the state cannot do, and these ordinances, therefore,

do not meet the standards required by the Fourteenth

Amendment. See Murdoch v. Pennsylvania, supra; Oros-

jean v. American Press Go., 297 IJ. S. 233.

22

I I I

The Ordinances Are Actual And Effective Inter

ferences W ith Freedom of Association and Not A Mere

Abstract Impairment of Constitutional Rights.

Petitioners based their refusal to comply with the terms

of the ordinances, which required disclosure of the names and

addresses of members and contributors of the N.A.A.C.P.

on the fear and belief that such disclosure would lead to

reprisals, harassment and bodily harm. In the testimony

introduced or proffered below, it was shown that there had

been a loss in membership of both Branches, which was

attributed to fear on the part of persons who normally

joined that their names might be published and they might

suffer hardship (R. 10-19; 52-56; 58-62). There was also

testimony that persons who had become publicly identified

with the Association had been subjected to pressures and

harassment. Both Mr. Fair, Vice President of the North

Little Rock N.A.A.C.P. Branch, and petitioner Williams

received annoying telephone calls and had to have their

telephone numbers changed several times (R. 55, 60). Mrs.

Williams had rocks thrown at her home, and her life was

threatened by letter and over the phone (R. 60). She was

denied temporary employment which she normally received

each year (R. 61). She was pointed out on the street as

the woman who had been arrested because of belonging to

the N.A.A.C.P. (R. 61). The devastating and corrosive effect

on freedom of association caused by the public identifica

tion of N.A.A.C.P. members is perhaps best epitomized by

petitioner Williams’ statement that none of the annoyances

or harassments testified to had occurred before passage of

the “ Bennett” ordinance and her public identification with

the Association. “ I was called a respectable woman before

that time” (R. 62).

Ordinances 10,638 and 2683 are another in a series of

efforts on the part of southern communities to restrict and

23

stifle the activities of the N.A.A.C.P., apparently in the

belief that by silencing the organization, the demand for

equal rights and equal justice will also die. See Robison,

“ Protection of Associations Prom Compulsory Disclosure

of Membership,” 58 Col. L. Rev. 614 (1958); “ Freedom of

Association,” 4 Race Rel. L. Rep. 207 (1959). Many of

these attempts have reached this Court. See, e.g.,

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, supra, and 360 U. S. 240 (again re

versing the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama);

N.A.A.C.P. v. Harrison, 360 IT. S. 467 (vacating and re

manding the judgment below on application of the doctrine

of federal abstention); N.A.A.C.P. v. Committee on

Offenses Against the Administration of Justice, 358 U. S.

40 (vacating the judgment below and remanding cause as

moot); N.A.A.C.P. v. Arkansas, ex rel Bruce Bennett,

Attorney General, 360 U. S. 909 (certiorari denied);

N.A.A.C.P. v. Bennett, 360 U. S. 471 (vacating and remand

ing judgment below for reconsideration in light of

N.A.A.C.P. v. Harrison) ■ N.A.A.C.P. v. Williams, 359 IT. S.

550 (certiorari denied in absence of a final judgment) ;

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Committee, 360

IT. S. 919 (certiorari denied); see also Scull v. Virginia, 359

IT. S. 344; Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (E. D. S. C.

1957), vacated and remanded, 354 IT. S. 933; Shelton v.

McKinley, — F. Supp. — (E. D. Ark. June 8, 1959).

The purpose and effect of these regulations are to restrict

and curb N.A.A.C.P. activities by interfering with the free

dom and privacy of associational relationships of members

in the N.A.A.C.P. Merely because the views and objec

tives of the Association do not meet with the approval

of state and local officials in Arkansas, see Cooper v. Aaron,

supra, the state cannot interfere with the rights of in

dividuals to freely advocate realization of those objectives

and to associate together in the N.A.A.C.P. for the pur

pose of engaging in lawful activity in furtherance of these

aims. Such, however, is what is attempted here.

24

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the reasons hereinabove stated,

petitioners submit that the convictions and sentences

here involved should be reversed, and that Ordi

nance No. 10,638 and Ordinance No. 2638 should

be struck down as prohibited by the due process clause

of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

Respectfully submitted,

R obebt L. Cabteb,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

(xEOKGE IIOWAPJ), J r.,

329% Main Street,

Pine Bluff, Arkansas,

Attorneys for Petitioners.

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing brief have

been served by depositing the same in a United States mail

box, with first-class postage prepaid, to the following

counsel of record:

Joseph C. Kemp, Esq.

812 Pyramid Life Building-

Little Rock, Arkansas

Reed Thompson, Esq. ,

North Little Rock

Arkansas

Dated: Sept. 17, 1959.

R obebt L. Cabteb.

Supreme P rinting Co., I nc., 54 Lafayette Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320