Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer Brief Amici Curiae, 1975. 73bfcae4-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/472ff5e4-a203-44f2-aa42-8813d237f3e0/fitzpatrick-v-bitzer-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

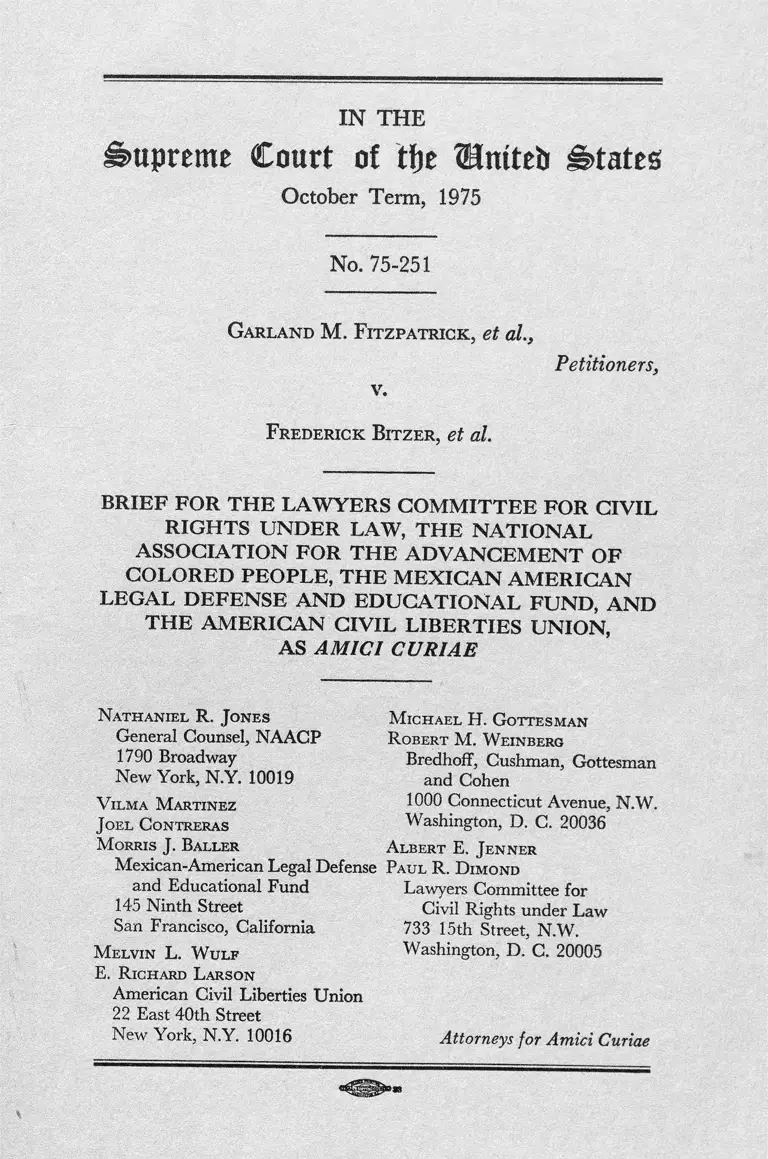

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje Umteb S tates

October Term, 1975

No. 75-251

Garland M. Fitzpatrick, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Frederick Bitzer, et al.

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF

COLORED PEOPLE, THE MEXICAN AMERICAN

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, AND

THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AS AMICI CURIAE

Nathaniel R. J ones

General Counsel, NAACP

1790 Broadway

New York, N.Y. 10019

V ilma Martinez

J oel Contreras

Morris J. Baller

Mexican-American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California

M elvin L. Wulf

E. R ichard Larson

American Civil Liberties Union

22 East 40th Street

New York, N.Y. 10016

M ichael H. Gottesman

R obert M. Weinberg

Bredhoff, Cushman, Gottesman

and Cohen

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Albert E. J enner

Paul R. D imond

Lawyers Committee for

Civil Rights under Law

733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF AM ICI C U R IA E .................................................... 1

INTROD UCTION AND SUMMARY OF A R G U M E N T .......... 2

ARGUMENT: IN ESTABLISHING FEDERAL JU RIS

DICTION OVER EMPLOYEE ACTIONS

AGAINST STATES FOR COMPLETE RE

LIEF, INCLUDING BACKPAY, FOR V IO

LATIONS OF TITLE V II, CONGRESS PRO

CEEDED IN FULL CONFORM ITY W ITH

THE CONSTITUTION ....................................... 9

A. Congress Has Power To Confer Federal Jurisdiction Over In

dividual “Federal Question” Suits Against S ta tes ....................... 10

1. Article III, as originally adopted, conferred federal judicial

power over federal question claims against the states, and

the Eleventh Amendment did not withdraw that power . . . . 11

2. Whatever the correctness of the decision in Hans v. Louisi

ana, its broad declaration that Congress lacks power to con

fer federal jurisdiction over federal question suits against

states is unfaithful to the historical and judicial precedents. . 19

3. This Court has recognized the inapplicability of Hans where

Congress has expressly conferred jurisdiction to entertain

federal question suits against s ta te s .......................................... 23

B. Congress Clearly Decided to Confer Federal Jurisdiction Over

Employee Actions Against States for Complete Relief, Includ

ing Backpay, for Violations of Title V I I ..................................... 28

C. The Foregoing Analysis Gains Additional Strength in This Case

Because the Cause of Action Was Created Pursuant to the

Fourteenth Am endm ent..................................... 31

1. The question whether the later enactment of the Fourteenth

Amendment brings it outside the scope of the Eleventh has

been recognized, but not decided, in prior cases..................... 31

2. The later enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment would,

indeed, bring it outside the reach of the Eleventh, even if the

Eleventh otherwise precluded federal question actions against

states ................................. 33

CONCLUSION ..................................................................................... 37

11

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) .......... 5, 11, 36

Alyeska Pipeline Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975) 11

Brennan v. Iowa, 494 F.2d 100 (8th Cir. 1974), cert, denied

421 U.S. 1015 (1975) ................................................................ 3

Burt v. Board of Trustees of Edgefield Cty. Sch. D., 521 F.2d

1201 (4th Cir. 1975) .......................................... ' . . . . . ......... .. . 4

Cheramie v. Tucker, 493 F.2d 586 (5th Cir. 1974) ................... 33

Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. 41,9 (1793) ............ .. 7, 14-16, 20-22

City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973) ....................... 33

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ..................................... .. 34-35

Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. 264 (1821) ..................... 8, 12, 17-19, 22

County of Lincoln v. Liming, 133 U.S. 529 (1 8 9 0 )........................ 4

Dean Hill Country Club, Inc. v. City of Knoxville, 379 F.2d

321 (6th Cir. 1967), cert, denied 389 U.S. 975 (1967) . . . . 33

Dunlop v. State of New Jersey, 522 F.2d 504 (3rd Cir. 1975) . . 3

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) 3, 4, 26, 28, 29, 30-31, 32-33

Employees v. Department of Public Health, 411 U.S. 279

(1973) .......................................................... ........................ 3, 8, 26-30

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) ............................. 10, 28, 35

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) ................................... 31-32, 33

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 519 F.2d 559 (2nd Cir. 1975) ............ 3, 4, 32

Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U.S. 87 (1810) ............................................ 20

Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824) ........................................... 25

Hander v. San Jacinto Junior College, 519 F.2d 273 (5th Cir.

1975) ........................................................................................ 4

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890) ............................... 8, 20-24, 27

Hopkins v. Clemson Agricultural College, 221 U.S. 636 (1911) 4

Hostrop v. Bd. of Jr. College Dist. No. 515, 523 F.2d 569 (7th

Cir. 1975) ........................................................................ . . . . . 4

Hutchison v. Lake Oswego School District, — F.2d —, 11 FEP ‘ ■

■ Cases 161 (9th Cir. 1975) .......................................................... i 4

Incarcerated Men of Allen County Jail v. Fair, 507 F.2d 281

: (6th Cir. 1974) ..................................................................... 4

Jordan v. Gilligan, 500 F.2d 701 (6th Cir. 1974) .................. 32

Kawanakoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349 (1907) ......................... 10

Kennecott Copper Corp. v. State Tax Commission, 327 U.S.

573 (1946) .......... 4

Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Corp., 337 U.S. 682 (1949) . . . 16

Maryland v. Wirtz, 392 U.S. 183 (1968) ....................... ' 26

Meyer v. State of New York, 344 F.Supp. 1377 (S.D. N.Y.

1971), affirmed 463 F,2d 424 (2nd Cir. 1972) ..................... 33

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ....................................... 28, 33

New Jersey v. Wilson, 11 U.S. 164 (1812) ................................. ' 20

Ill

Page

North Carolina v. Temple, 134 U.S. 22 (1890) ......................... 20

Parden v. Terminal R. Co., 377 U.S. 184 (1963) .......... 8, 23-30, 33

Petty v. Tennessee-Missouri Bridge Commission, 359 U.S. 275

(1959) ........................................................................................... 12

Powell v. McCormack, 395 U.S. 486 (1969) .............................. 19

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969), affirming 270 F.

Supp. 331 (D. Conn. 1967) ......................... ........................... 32

Singer v. Mahoning County Board of Mental Retard., 519 F.2d

748 (6th Cir. 1975) ........................................ ................ ............ 4

Sires v. Cole, 320 F.2d 877 (9th Cir. 1963) ............................... 33

Skehan v. Board of Trustees of Blaomsburg State Col., 501 F.2d

31 (3rd Cir. 1974) .................................................................. .... 32

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873) .................................. 34

State Depart, of Health and Rehabilitation Services v. Zarate,

407 U.S. 918 (1972), affirming 347 F.Supp. 1004 (S.D. Fla.

1971) ................................................... 32

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ....................... 34

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969) .............. 36

United States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965) ..................... 3

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir.

1973) .................................................................................... 5

United States v. Texas, 143 U.S. 621 (1892) ............................. 3

United States ex rel. Lee v. State of Illinois, 343 F.2d 120 (7th

Cir. 1965) ..................................................................................... 33

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313 (1880) ......................................... 35

Wyman v. Bowens, 397 U.S. 49 (1970), affirming 304 F.Supp.

717 (S.D. N.Y. 1969) ......................................................... 32

Constitutional Provisions

Article III, Section 2 . .

Article VI ...................

Eleventh Amendment ,

Fourteenth Amendment

Section 1 ...................

Section 5 ...................

Statutory Provisions

Civil Rights Act of 1871, 42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................... 26, 33

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, as amended by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 ................................... 2-37

Section 706 (f) (1), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5 (f) (1) ................... 3

Section 706 (g), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g) ............................... .. 3

...............6-7, 11-22

................... 10, 11

..................... 2-37

2, 8-9, 27-28, 31-36

........ .. 34

. . 3, 8, 31, 34, 35

Fair Labor Standards A c t ........................................................ 3,

Federal Employers Liability A c t ....................................................

M iscellaneous

Federalist No. 32 (Hamilton) ......................................................

Federalist No. 81 (Hamilton) ............................................ 12-14.

Flack, “The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment” (John

Hopkins Press, 1907; Peter Smith, 1965) ...............................

Hart and Wechsler, “The Federal Courts and the Federal Sys

tem” (2nd Ed. 1973) ................................................................

H. Rep. No. 92-899, 92d Cong. 2d Sess. (1972) .......................

“Legislative History of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972,” published by the Senate Committee on Labor and

Public Welfare (1972) ................................................ 3, 4, 5,

S. Rep. No. 92-681, 92d Cong. 2d Sess. (1972) .........................

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “For All the People . . . By

All the People” (1969) ..................................... ........................

Page

26, 30

23, 26

14

20-21

34

4

29

29, 30

29

5

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje Hmteb S tates

October Term, 1975

No. 75-251

Garland M. Fitzpatrick, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Frederick Bitzer, et al.

B R IE F FO R T H E LA W Y E R S C O M M IT T E E FO R CIVIL

R IG H T S U N D E R LAW , T H E N A T IO N A L

A SSO C IA T IO N FO R T H E A D V A N C E M E N T O F

C O L O R ED PE O PLE , T H E M E X IC A N A M E R IC A N

L EG A L D E F E N S E A N D E D U C A T IO N A L F U N D , A N D

T H E A M E R IC A N C IV IL L IBE R T IE S U N IO N ,

A S A M IC I C U R IA E

IN T E R E ST O F A M IC I CURIAE*

The Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law is

a non-profit corporation organized in 1963 at the request of

President Kennedy: its Board of Trustees includes thirteen

past presidents of the American Bar Association, three

former Attorneys General, and two former Solicitors Gen

eral of the United States. The Committee’s primary mission

is to involve private lawyers throughout the country in the

quest of all citizens to secure their civil rights through the

legal process.

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

* This brief is filed, pursuant to Rule 42(2), with the consent of the

parties.

2

ored People (NAACP) is a non-profit membership associa

tion representing the interests of approximately 500,000

members in 1800 branches throughout the United States.

Since 1909, the NAACP has sought through the courts to

establish and protect the civil rights of minority citizens.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund was established in 1968. Its primary objective is to

secure the civil rights of Mexican Americans through litiga

tion and education.

The American Civil Liberties Union is a nation-wide,

non-partisan organization of over 250,000 members dedi

cated to protecting the civil liberties of all persons includ

ing, inter alia, the right of all persons to equal treatment

under the law.

The issue in this case is whether, consistent with the

Eleventh Amendment, state employees may secure monetary

relief in private actions when they have suffered discrimina

tion in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Each of the amici has a vital interest in the resolution of

this issue.

This brief is filed to provide the Court with the views of

amici, refined through extensive litigation under Title VII

and the Fourteenth Amendment, that the Eleventh Amend

ment is not a barrier to the private cause of action against

states for complete relief from prior discrimination, includ

ing backpay, created by Congress in the 1972 amendments

to Title VII.

IN T R O D U C T IO N A N D SU M M A RY O F

A R G U M EN T

In 1972, Congress amended Title VII to extend its pro

tections against discrimination to employees of state and

local governments. With unmistakable clarity, Congress

evinced an intention to create two separate mechanisms for

3

enforcement of these protections: (1) a suit by the Attorney

General to recover injunctive relief and backpay for em

ployees who have suffered unlawful discrimination; and (2)

a suit by the injured employees themselves, if the Attorney

General does not act within 180 days of the filing of a

charge, to recover that same relief for their own benefit.1

No one disputes Congress’ power to impose the substan

tive prohibitions of Title VII upon the states. The 1972

amendments, as Congress explained in enacting them, were

an exercise of the power conferred by Section 5 of the Four

teenth Amendment “to enforce, by appropriate legislation,

the provisions of this article.”2

Nor does anyone dispute Congress’ authority to authorize

suits in federal court by the Attorney General to recover

backpay on behalf of discriminatees. “ [Sjui'ts by the United

States against a State are not barred by the Constitution.”

Employees v. Missouri Public Health Dept., 411 U.S. 279,

285-286 (1973) (recognizing Congress’ power to authorize

suits by the Secretary of Labor to recover unpaid minimum

wages and unpaid overtime compensation withheld by states

from hospital and school employees in violation of the Fair

Labor Standards Act) .3

1 Sections 706(f)(1) and (g), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f) (1) and (g).

See also “Legislative History of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972,” published by the Senate Committee on Labor and Public

Welfare (hereinafter “Leg. Hist.” ), pp. 1815-16, 1847. Congress addi

tionally provided that if the employees themselves bring the suit, and

are successful, they may be awarded attorneys fees. Section 706(g). 42

U.S.C. §2000e-5(g).

2 Leg. Hist. 79, 420, 1173-74.

3 See also Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 669 (1974); United

States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128, 140-141 (1965); United States v.

Texas, 143 U.S. 621, 643-646 (1892); Brennan v. Iowa, 494 F.2d 100,

103 (8th Cir. 1974), cert, denied 421 U.S. 1015 (1975); Dunlop v.

State of New Jersey, 522 F.2d 504, 515-516 (3rd Cir. 1975). And see

the decision below, Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 519 F.2d 559, 570 (2nd Cir.

1975).

4

But the Eleventh Amendment has been invoked, and con

strued by the court below, to invalidate that portion of the

1972 amendments by which Congress created a private

cause of action for backpay against state governments (al

beit not, presumably, against local governments which do

not enjoy the protection of the Eleventh Amendment4).

The practical consequences of that ruling, if upheld, are

awesome.

There are millions of state employees,5 and Congress

found that employment discrimination against them is

4 It is hornbook law that a “suit against a county, a municipality, or

other lesser governmental unit is not regarded as a suit against a state

within the meaning of the Eleventh Amendment.” H art and Wechsler,

The Federal Courts and the Federal System, 690 (2nd Ed. 1973). See,

e.g., County of Lincoln v. Luning, 133 U.S. 529, 530 (1890); Flopkins

v. Clemson Agricultural College, 221 U.S. 636 (1911); Kennecott Cop

per Corp. v. State Tax Commission, 327 U.S. 573, 579 (1946); Edel-

man v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 667 n. 12 (1974); Incarcerated Men of

Allen County Jail v. Fair, 507 F.2d 281, 287 (6th Cir. 1974); Hander

v. San Jacinto Junior College, 519 F.2d 273, 279 (5th Cir. 1975);

Singer v. Mahoning County Board of Mental Retard., 519 F.2d 748,

749 (6th Cir. 1975); Burt v. Board of Trustees of Edgefield Cty. Sch.

D., 521 F.2d 1201, 1205 (4th Cir. 1975); Hostrop v. Bd. of Jr. College

Dist. No. 515, 523 F.2d 569, 577 n. 3 (7th Cir. 1975); Hutchison v.

Lake Oswego School District, F.2d , 11 FEP Cases 161, 165

(9th Cir. 1975). In the instant case, the court below concluded that

the State Employees’ Retirement Commission is the “alter ego” of

the State, and thus enjoys whatever immunity the Eleventh Amend

ment provides the State of Connecticut (519 F.2d at 564-565). Peti

tioners have not sought review of that holding, and accordingly our

brief assumes arguendo that respondents are “the state” for Eleventh

Amendment purposes.

5 Congress found that there are more than ten million employees of

state and local governments. Leg. Hist. 77, 418. The congressional data

does not indicate how much of the total represents employees of the

states, or of agencies which are the “alter ego” of the states and thus

share the states’ Eleventh Amendment immunity, but the figure surely

is in the millions.

5

“more pervasive than in the private sector.”6 It is a central

purpose of Title VII “to make persons whole for injuries

suffered on account of unlawful employment discrimina

tion,” Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody>, 422 U.S. 405, 418

(1975), a purpose which in most cases cannot be achieved

without backpay, Id. at 418-421. It is also the purpose of

Title VII to prompt employers to discard their discrimina

tory practices, a purpose with which backpay has “an ob

vious connection,” Id. at 417.7

Congress, deeming these considerations equally applicable

to state employers, made backpay available against the

states. Congress also made the judgment, given the multi

tude of potential claims by state employees, not to make

the Attorney General the sole prosecutor of Title VII claims

on behalf of such employees. Declaring that preservation

of the discriminatee’s cause of action was “paramount,”73

6 Leg. Hist. 77-78, 418-419. Congress relied in part upon a report of

the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, For All the People . . . By All

the People (1969). The report “examined equal employment oppor

tunity in public employment in seven urban areas located throughout

the country—North as well as South” (Leg. Hist. 77). The House

Committee summarized the report’s findings as follows (ibid.) :

The report’s findings indicate that widespread discrimination

against minorities exists in State and local government employ

ment, and that the existence of this discrimination is perpetuated

by the presence of both institutional and overt discriminatory prac

tices. The report cites widespread perpetuation of past discrimina

tory practices through de facto segregated job ladders, invalid

selection techniques, and stereotyped misconceptions by supervisors

regarding minority group capabilities.

7 “If employers faced only the prospect of an injunctive order, they

would have little incentive to shun practices of dubious legality. It is

the reasonably certain prospect of a backpay award that ‘pr°vicle[s] the

spur or catalyst which causes employers and unions to self-examine and

to self-evaluate their employment practices and to endeavor to elim

inate, so far as possible, the last vestiges of an unfortunate and ignomi

nious page in this country’s history’.” Id. at 417-418, quoting United

States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354, 379 (8th Gir. 1973).

7a Leg. Hist. 1847.

6

Congress expressly conferred a private cause of action when

ever the Attorney General has not sued within 180 days

of the filing of an employee’s charge.

Invalidation of the private cause of action for backpay

would mean either that Title V II’s objectives would go

partially unfulfilled, or that Congress would have to appro

priate the additional sums necessary to enable the Attorney

General to institute actions wherever a valid claim of dis

crimination existed. Whether the Eleventh Amendment

subjects Congress to this Hobson’s choice is the issue posed

by this case.

We show in this brief that Title V II’s private cause of

action for backpay does not contravene the Eleventh

Amendment. Our showing proceeds upon the following

analysis:

Immunity from suit is an attribute of sovereignty. While

the states retained their sovereignty over most matters upon

entering the Union, they yielded their sovereignty to the

extent that the Constitution conferred powers upon the na

tional government—powers which were declared to be “su

preme”.

As originally adopted, however, Article III, Section 2 of

the Constitution—which defined the federal judicial power

—encroached upon state sovereignty in greater respects than

did the remainder of the document. For in addition to creat

ing judicial power over all federal questions—a power

which was understood to embrace federal question claims

against the states, and which excited no controversy as it

was wholly consistent with the cession of sovereignty made

by the states in joining the Union—it also created judicial

power over state law “controversies . . . between a State and

citizens of another State . . . and between a State . . . and

foreign states, citizens or subjects.” This provision did excite

controversy, for read literally it trespassed upon the sover

eignty retained by the states: the states would become sua

7

ble in federal court upon “state law” claims which they had

not consented to entertain in their own courts.

In urging ratification of the Constitution, supporters as

sured the states that the “diversity” clause was not to be

read literally: it was not intended to depart from the gen

eral principle that a sovereign is immune from suit absent

consent, and thus it would allow “state law” suits against

states only where not inconsistent with their sovereignty, i.e.,

where they had consented to suit. That promise proved

short-lived, however, for in Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. 419

(1793), four of the Court’s five justices construed the di

versity clause literally, to confer federal judicial power

over any claim against a state by a non-citizen of that state.

Only the lone dissenter, Justice Iredell, would have confined

the diversity clause to state-law claims upon which the

States had consented to suit. (Significantly, Justice Iredell

recognized and approved Congress’ power to create federal

jurisdiction over federal question claims against the states).

The Eleventh Amendment was a reaction to Chisholm.

It was designed to reinstate the original understanding of

the diversity clause, to which only Justice Iredell had ad

hered in Chisholm. The wording of the Amendment—

which speaks in diversity terms—is no accident; it defines

the metes and bounds of the alteration which its framers

sought to accomplish. There is no historical evidence

that the Amendment was intended to withdraw federal ju

dicial power over federal question claims against states,

and indeed such a withdrawal would have been wholly in

consistent with the Amendment’s objective: to restore the

states’ “sovereign” immunity from suit. The framers of the

Amendment would surely have chosen different words if

their intention had been to preclude all suits against states,

for they were aware that all who had articulated the “origi

nal understanding” which they sought to reinstate—includ

ing Justice Iredell—had approved the existence of federal

8

judicial power over federal question claims against the

states.

In Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. 264 (1821), Chief Justice

Marshall confirmed that the Eleventh Amendment had not

withdrawn federal judicial power over federal question

claims against states. But 69 years later, in Hans v. Louisi

ana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890), the Court declared otherwise. Al

though the Hans Court might have decided the case before

it on narrower grounds, it announced that states could never

be sued in federal court without their consent. This conclu

sion was premised upon a wholly erroneous reading of the

historical and judicial precedents. This Court has subse

quently recognized that, whatever the correctness of the

holding in Hans on the narrow issue presented there, its

broad declaration of universal immunity will not be fol

lowed when it collides with an express decision by Congress,

in exercising the sovereign powers of the national govern

ment, to confer federal jurisdiction over individual causes

of action against the states. Par den v. Terminal R. Co.,

377 U.S. 184 (1963); Employees v. Department of Public

Health, 411 U.S. 279 (1973).

Parden and Employees involved the Commerce Clause.

That clause does not authorize Congress to regulate states

per se, but only to regulate interstate commerce. Accord

ingly, this Court recognized that Congress could make the

states susceptible to suits under the Commerce Clause only

as the states voluntarily brought themselves within the ambit

of the commerce power by engaging in interstate commerce.

The instant case, by contrast, involves an exercise of con

gressional power pursuant to Section 5 of the fourteenth

Amendment. As that Amendment empowers Congress to

regulate the states directly, there is no need here, as there

was in the commerce cases, to find a subsequent waiver of

immunity by the states’ electing to bring themselves within

the ambit of congressional power: the states are by defini

tion within the ambit of Congress’ power to enforce the

9

Fourteenth Amendment. Their sovereignty in this area was

yielded up to the national government when the Amend

ment was adopted, and with it the sovereign’s right to im

munity from suit.

Of course, that the states have ceded Congress the power

to confer federal jurisdiction over federal question claims

against them does not mean that the federal courts auto

matically have jurisdiction to entertain such claims. The

lower federal courts have only such jurisdiction as Congress

opts to confer upon them. Congress, sensitive to the ex

traordinary cession of state sovereignty implicit in our fed

eral scheme, has treaded warily in conferring jurisdiction

over individual causes of action against states, and this

Court has demanded clear evidence of Congressional intent

before concluding that the states have been made suable.

Such evidence exists in the case of the 1972 Amendments

to Title VII. Congress decided that employee actions

against states should be available, in which employees could

recover all appropriate relief, including backpay.

The foregoing analysis, although valid for Congress’ exer

cise of any of its enumerated powers, gains additional

strength in this case because the cause of action was created

pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment. Even if the

Eleventh Amendment had withdrawn federal judicial power

over all claims against states under the Constitution as it

then existed, the Fourteenth Amendment, adopted 70 years

later, mandated Congress to fashion remedial schemes “ap

propriate” to enforce the obligations which that Amend

ment imposed directly upon the states.

ARGUMENT

IN E ST A B L ISH IN G F E D E R A L JU R ISD IC T IO N O V E R

E M PL O Y E E A C T IO N S A G A IN ST ST A T E S FO R CO M

P L E T E R E L IE F , IN C L U D IN G BA C K PA Y , FO R V IO

L A T IO N S O F T IT L E VII, C O N G R ESS P R O C E E D E D

IN F U L L C O N F O R M IT Y W IT H T H E C O N ST IT U T IO N .

10

A . Congress H as Power To Confer Federal Jurisdiction over

Individual “Federal Question” Suits Against States.

In 1907, Mr. Justice Holmes, writing for the Court, suc

cinctly stated the source of the sovereign’s immunity from

suit. Kawanakoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349, 353 (1907) :

Some doubts have been expressed as to the source

of the immunity of a sovereign power from suit without

its own permission, but the answer has been public

property since before the days of Hobbes. Leviathan,

chap. 26, 2. A sovereign is exempt from suit, not be

cause of any formal conception or obsolete theory, but

on the logical and practical ground that there can be

no right as against the authority that makes the law

on which the right depends.

In the instant case, the State of Connecticut asserts that

it is immune from a suit which Congress has authorized.

That assertion of immunity obviously does not fit traditional

notions of sovereign immunity, for here the state is not “the

authority that [made] the law on which the right depends.”

Congress made the law; it acted within its power in doing

so; and the Constitution declares that Congress’ decision is

“the supreme law of the land; . . . anything in the constitu

tion or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.”

Art. VI, cl. 2.

Connecticut’s lack of “sovereignty” with respect to the

subject matter of this suit is an outgrowth of our federal

system, which creates bifurcated sovereignties. While the

states of course remain sovereign with respect to all matters

not committed to the control of the national government,

they are not and cannot be “sovereign” in those areas where

the federal power is “supreme.” By entering the Union, and

accepting the Constitution, the states yielded up their sover

eignty to this extent. “[E]very addition of power to the

General Government involves a corresponding diminution

of the governmental powers of the States. It is carved out

of them.” Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 346 (1880).

11

The decision below thus does not vindicate Connecticut’s

“sovereignty,” but rather deprives the federal government

of a portion of its sovereignty. What the court below has

done, in the name of the Constitution, is to reverse the

Supremacy Clause. It has hamstrung Congress in the choice

of means for implementing powers which Congress indis

putably possesses, and conditioned Congress’ ability to utilize

the means Which it prefers—and prefers for good reasons8

—upon the states’ consenting to that use.

Of course, a constitution could be written which com

manded such incongruous results. But as we show in this

brief, nothing in our Constitution commands them.

1. A rtic le III, as originally adopted, conferred federal judicial

pow er over federal question claims against the states, and the

Eleventh A m endm ent did not w ithdraw that power.

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution—which defines

the federal judicial power—differs in an important respect

from all other provisions of the Constitution. The other pro

visions delineate clear lines between those matters which

remain the states’ domain, and those which are ceded up

to the federal government. But Article III, Section 2, ob

literates those lines to some extent; in addition to conferring

federal judicial power over “federal” questions, it confers

such power over “state law” questions where there is diver

sity of citizenship. And its literal language appears to au

thorize suits against states by non-citizens without exception,9

thus wholly eradicating the states’ immunity from suit in

areas of “state law” where their sovereignty is retained.

8 Not only does Congress’ allowance of employee suits lessen the

sums which must be appropriated for the Attorney General, but it also

reflects Congress’ judgment that employee enforcement is critical to the

accomplishment of Title V II’s objectives. Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 415 (1975). See also Alyeska Pipeline Co. v.

Wilderness Society, 421 U.S. 240, 263 (1975).

9 Article III, Section 2 extends the judicial power to “controversies

. . . between a State and citizens of another State . . . and between a

State, and foreign states, citizens, or subjects.”

12

It is thus not suprising that while the “federal question”

portion of the Article excited no concern among the state

legislatures during the ratification process, the “diversity”

portion—particularly that relating to the suability of states

—was a subject of great discussion. The concern was not

merely a theoretical one about the nature of the states’ re

tained sovereignty, but a very practical one as well.10 The

war of revolution had drained the resources of the colonies.

In order to finance the war, the colonies had borrowed

heavily. They entered the Union with debts they knew

they could not meet. So long as they remained independent

entities this was not a problem, for they retained the power

to deny access to their courts to disappointed creditors. But

the diversity jurisdiction in the proposed Constitution, they

feared, would enable foreign creditors, and creditors from

other states, to secure judicial awards compelling payment.

It was to quiet these fears that Alexander Hamilton, in

Federalist No. 81, “digressfed]” to discuss “a supposition

which has excited some alarm upon very mistaken

grounds” :

It has been suggested that an assignment of the pub

lic securities of one State to the citizens of another,

would enable them to prosecute that State in the fed

eral courts for the amount of those securities; a sugges

tion which the following considerations prove to be

without foundation.

It is inherent in the nature of sovereignty not to be

amenable to the suit of an individual without its con

sent. This is the general sense, and the general prac

tice of mankind; and the exemption, as one of the at

tributes of sovereignty, is now enjoyed by the govern

ment of every State in the Union. Unless, therefore,

there is a surrender of this immunity in the plan of the

10 This concern is described in Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. 264, 406-

407 (1821); Petty v. Tennessee-Missouri Bridge Comm’n., 359 U.S.

275, 276, n. 1 (1959).

13

convention, it will remain with the States, and the dan

ger intimated must be merely ideal. The circumstances

which are necessary to produce an alienation of State

sovereignty were discussed in considering the article of

taxation, and need not be repeated here. A recurrence

to the principles there established will satisfy us, that

there is no color to pretend that the State governments

would, by the adoption of that plan, be divested of the

privilege of paying their own debts in their own way,

free from every constraint but that which flows from

the obligations of good faith. The contracts between

a nation and individuals are only binding on the con

science of the sovereign, and have no pretensions to a

compulsive force. They confer no right Of action, in

dependent of the sovereign will.

To what purpose would it be to authorize suits

against States for the debts they owe? How could re

coveries be enforced? It is evident, it could not be done

without waging war against the contracting State; and

to ascribe to the federal courts, by mere implication,

and in destruction of a pre-existing right of the State

governments, a power which would involve such a con

sequence, would be altogether forced and unwarrant

able.11

As is apparent, Hamilton was not saying that the states

could never be sued in the federal courts. He was saying

that immunity from suit was “in the nature of sovereignty,”

and thus except as to those matters upon which the Consti

tution “produce [d] an alienation of State sovereignty” the

states remained immune. Because the Constitution did not

take from the states “the privilege of paying their own debts

in their own way,” they retained their sovereignty on this

11 Federalist No. 81 (Hamilton), in The Federalist (Modern Library

Ed.), pp. 529-530 (emphasis in original).

14

matter, and the fear that they could be sued in federal court

to compel payment of their debts was unwarranted.

In the text quoted above, Hamilton indicated that the

“circumstances which are necessary to produce an alienation

of State sovereignty”—and Which, implicitly, would with

draw the states’ immunity from suit—had been “discussed

in considering the article of taxation.” The reference was

to Federalist No. 32, where he had said:

But as the plan of the convention aims only at a

partial union or consolidation, the State governments

would clearly retain all the rights of sovereignty which

they before had, and which were not, by that act, ex

clusively delegated to the United States. This exclusive

delegation, or rather this alienation, of State sovereign

ty, would only exist in three cases: where the Constitu

tion in express terms granted an exclusive authority to

the Union; where it granted in one instance an authori

ty to the Union, and in another prohibited the States

from exercising the like authority; and where it granted

an authority to the Union, to which a similar authority

in the States would be absolutely and totally contradic

tory and repugnant. (Id. at 194; emphasis in original)

Hamilton’s promise that the states could not be sued on

their debts proved short-lived. In Chisholm v. Georgia, 2

U.S. 419 (1793), four of the Court’s five justices declared

that a state law assumpsit action by a creditor seeking to

compel the state’s payment of a debt was indeed within the

federal jurisdiction, a holding which they premised upon

the literal language of the diversity clause. Justice Iredell

dissented, and his dissent is important to an understanding

of what the Eleventh Amendment was later adopted to

accomplish.

Justice Iredell fully recognized that Congress could make

the states amenable to suits in federal court on federal ques

tion claims, a power which he deemed relevant “to the

15

execution of the other authorities of the general government

(which it must be admitted are full and discretionary, with

in the restrictions of the constitution itself),” id. at 432.

These “special objects of authority of the general govern

ment, wherein the separate sovereignties of the states are

blended in one common mass of supremacy,” id. at 435,

were not the cause of his concern. As to them, he observed

only that he believed an act of Congress was necessary to

confer jurisdiction to entertain such suits, a course which

he did not understand Congress to have yet taken, id. at

448-449.

Rather, Justice Iredell’s concern was with the intrusion

upon state sovereignty which the majority drew from the

“peculiar” feature of Article III, Section 2: that after con

ferring federal question jurisdiction it “also goes further”

and confers diversity jurisdiction as well, id. at 435-436. In

his view, analysis of the extent to which states were suable

under the diversity jurisdiction had to begin with an under

standing of the respective sovereignties of the national and

state governments, id. at 435:

Every state in the union in every instance where its

sovereignty has not been delegated to the United States,

I consider to be completely sovereign, as the United

States are in respect to the powers surrendered. The

United States are sovereign as to all the powers of gov

ernment actually surrendered. Each state in the union

is sovereign as to all the powers reserved. It must be

so, because the United States have no claim to any

authority but such as the states have surrendered to

them. Of course, the part not surrendered must remain

as it did before.

But here was the rub: if under the diversity jurisdiction

a state could be sued in federal court on state law grounds,

it would lose the sovereign’s immunity from suit in those

very areas where the Constitution left the states sovereign.

16

Could this have been the framers’ intention? Justice Iredell

thought not. He believed that the diversity clause made

the states suable only where, under the common law, the

sovereign could be sued (i.e., by its consent) (id. at 436-

446). By this construction, Justice Iredell believed that the

language of the diversity clause could be given effect with

out abrogating the states’ retained sovereignty.

The majority’s holding in Chisholm sent shock tremors

through the state legislatures. The Eleventh Amendment

was proposed by an overwhelming vote at the next session

of Congress, and was ratified by the states with “vehement

speed.”12 Its wording is the strongest evidence that its pur

pose was narrow: to reinstate the framers’ original intent

with respect to the diversity clause (i.e., to maintain the

states’ immunity with respect to matters within their re

tained sovereignty), and not to withdraw federal judicial

power over federal claims against states:

The judicial power of the United States shall not be

construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, com

menced or prosecuted against one of the United States

by citizens of another state, or by citizens or subjects

of any foreign state.

This language, of course, tracks the diversity clause of Arti

cle III, Section 2, and it defines the metes and bounds of

the alteration which its authors sought to accomplish. The

failure to prohibit all suits against states cannot be deemed

an oversight. Its authors surely knew that both Hamilton

and Justice Iredell had recognized the availability of federal

question suits against states, and there is no evidence that

the Amendment was intended to make the states immune

from suit where they were not sovereign. Had its authors

indeed had such an intention, it is difficult to believe that

they would have chosen words so ill-suited to the task.

12 Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Corp., 337 U.S. 682, 708 (1949)

(dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter).

17

That the purpose of the Eleventh Amendment was con

fined to the diversity clause was soon confirmed by Chief

Justice Marshall. In Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. 264, 380-

383 (1821), he described the original intention of the draf

ters of Article III, Section 2, an intention which he did not

find overturned by the Eleventh Amendment:

“The counsel for the [state] . . . have laid down the

general proposition, that a sovereign independent state

is not suable except by its own consent.

This general proposition will not be controverted.

But its consent is not requisite in each particular case.

It may be given in a general law. And if a state has

surrendered any portion of its sovereignty, the question

whether a liability to suit be a part of this portion, de

pends on the instrument by which the surrender is

made. If, upon a just construction of that instrument,

it shall appear that the state has submitted to be sued,

then it has parted with this sovereign right of judging

in every case on the justice of its own pretensions, and

has entrusted that power to a tribunal in whose impar

tiality it confides.

The American States, as well as the American peo

ple, have believed a close and firm Union to be essential

to their liberty and to their happiness. They have been

taught by experience, that this Union cannot exist with

out a government for the whole; and they have been

taught by the same experience that this government

would be a mere shadow, that must disappoint all their

hopes, unless invested with large portions of that sover

eignty which belongs to independent states. Under the

influence of this opinion, and thus instructed by experi

ence, the American people, in the conventions of their

respective states, adopted the present constitution.

If it could be doubted, whether from its nature, it

were not supreme in all cases where it is empowered to

18

act, that doubt would be removed by the declaration,

that “this constitution, and the laws of the United

States, which shall be made in pursuance thereof, and

all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the

authority of the United States, shall be the supreme

law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be

bound thereby; anything in the constitution or laws of

any state to the contrary notwithstanding.”

This is the authoritative language of the American

people; and, if gentlemen please, of the American

States. It marks, with lines too strong to be mistaken,

the characteristic distinction between the government

of the Union and those of the states. The general gov

ernment, though limited as to its dbjects, is supreme

with respect to those objects. This principle is a part

of the constitution; and if there be any Who deny its

necessity, none can deny its authority.

To this supreme government ample powers are con

fided; and if it were possible to doubt the great pur

poses for which they were so confided, the people of

the United States have declared, that they are given

“in order to form a more perfect union, establish jus

tice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the com

mon defense, promote the general welfare, and secure

the blessings of liberty to themselves and their posteri

ty.”

With the ample powers confided to this supreme gov

ernment, for these interesting purposes, are connected

many express and important limitations on the sover

eignty of the states, which are made for the same pur

poses. The powers of the Union, on the great subjects

of war, peace, and commerce, and on many others, are

in themselves limitations of the sovereignty of the

states; but in addition to these the sovereignty of the

states is surrendered in many instances where the sur

19

render can only operate to the benefit of the people,

and where, perhaps, no other power is conferred on

Congress than a conservative power to maintain the

principles established in the constitution. The main

tenance of these principles in their purity, is certainly

among the great duties of the government. One of the

instruments by which this duty may be peaceably per

formed, is the judicial department. It is authorized to

decide all cases of every description, arising under the

constitution or laws of the United States. From this

general grant of jurisdiction, no exception is made of

those cases in which a state may be a party. When we

consider the situation of the government of the Union

and of a state, in relation to each other; the nature of

our Constitution; the subordination of the state govern

ments to that constitution; the great purpose for which

jurisdiction over all cases arising under the constitution

and laws of the United States is confided to the ju

dicial department, are we at liberty to insert in this

general grant, an exception of those cases in which a

state may be a party? Will the spirit of the constitution

justify this attempt to control its words? We think it will

not. We think a case arising under the constitution or

laws of the United States, is cognizable in the courts

of the Union, whoever may be the parties to that case.

See also, id . at 412.

2. W hatever the correctness of the decision in H ans V. Louis

iana, its broad declaration that Congress lacks pow er to con

fer federal jurisdiction over federal question suits against

states is unfaithful to the historical and judicial precedents.

Congress first conferred general federal question jurisdic

tion upon the lower federal courts in 1875.1S It was inevita

ble that cases would soon come to the Court involving fed

eral claims against states. What was not inevitable—indeed, 13

13 Powell v. McCormack, 395 U.S. 486, 515-516 (1969).

20

what was an extraordinary coincidence—was that the first

cases to arrive would look so much like Chisholm.

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890), and its compan

ion case, North Carolina v. Temple, 134 U.S. 22 (1890),

were (like Chisholm) suits to compel states to honor their

debt obligations. But, unlike Chisholm, they were federal

question suits, the creditors contending that the states had

impaired the obligation of their contracts by legislating

exemption from their debts. The similarity to Chisholm

clearly impressed the Hans Court, which repeatedly referred

to the historical evidence that resistance to the enforceability

of state debts was the immediate objective of the Eleventh

Amendment, 134 U.S. at 12-13, 16.14

The Court recognized that the Eleventh Amendment

could not preclude the suit, for the creditor was a citizen

of Louisiana, id. at 10:

In the present case the plaintiff in error contends

that he, being a citizen of Louisiana, is not embarrassed

by the obstacle of the 11th Amendment, inasmuch as

that Amendment only prohibits suits against a State

which are brought by the citizens of another State, or

by citizens or subjects of a foreign state. It is true, the

Amendment does so read; and if there were no other

reason or ground for abating his suit, it might be main

tainable. . . . (emphasis added).

But the Court found two “other reasons.” One, which

would have been entirely sufficient to dispose of the case,

was that Congress had not conferred jurisdiction upon the

14 It was not until a decade after adoption of the Eleventh Amend

ment that the Court ruled that the impairment of obligation of contract

clause “extends to contracts to which a state is a party, as well as to

contracts between individuals.” Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U.S. 87 (1810),

as characterized in New Jersey v. Wilson, 11 U.S. 164, 166 (1812).

Thus, the authors of the Eleventh Amendment probably did not antici

pate that state debts might still be. reachable under the federal ques

tion clause of Article III.

21

lower federal courts to entertain the suit, id. at 18.15 16 But

the Court did not rest with that. It flatly declared that

Congress was without power to create such a cause of ac

tion, for Article III, Section 2, as originally adopted did

not include, within the federal judicial power, federal ques

tion claims against states, id., at 10-18.

This declaration proceeded from a misunderstanding of

the relevant historical and judicial precedents. The Court

quoted Hamilton’s discussion in Federalist No. 81, and Jus

tice Iredell’s analysis in Chisholm, and drew from these

the erroneous lesson that all suits against states were for

bidden—a result which the Hans court presumed to have

been intended by the framers of the original Constitution,

frustrated by Chisholm, and restored in spirit by the Elev

enth Amendment, id. at 13-14:

The obnoxious clause to which Hamilton’s argument

was directed, and which was the ground of the objec

tions which he so forcibly met, was that which declared

that ‘the judicial power shall extend to all . . . contro

versies between a State and citizens of another State,

. . . and between a State and foreign states, citizens or

subjects.’ It was argued by the opponents of the Con

stitution that this clause would authorize jurisdiction

to be given to the Federal courts to entertain suits

against a State brought by citizens of another State, or

of a foreign state. Adhering to the mere letter, it might

be so; and so, in fact, the supreme court held in Chis

holm v. Georgia; but looking at the subject as Hamilton

did, and as Mr. Justice Iredell did, in the light of his

tory and experience and the established order of things,

15 The Court reasoned that as the statute conferring federal question

jurisdiction invested the federal courts with jurisdiction “concurrent

with the courts of the several States,” and as the “state courts have no

power to entertain suits by individuals against a State without its con

sent,” Congress had not intended to confer jurisdiction over actions

against states, id. a t 18.

22

the views of the latter were clearly right-—as the people

of the United States in their sovereign capacity subse

quently decided (emphasis added).

This passage, on its face, discloses the slip in the Court’s

analysis. The Court recognized that the “obnoxious clause”

was the diversity clause, that it was this clause which

Chisholm had misconstrued by adherence to the “mere

letter,” and that the Eleventh Amendment was adopted to

reverse Chisholm. Yet from these correct premises the

Court drew the non-sequitur that that Amendment nar

rowed the scope of the federal question clause as well.

The Court appears to have overlooked entirely that both

Hamilton and Justice Iredell recognized and approved the

suability of states on federal question grounds. The Court

did not overlook, however, that Chief Justice Marshall had

said the same in Cohens. The latter observation was “con

ceded” to support the plaintiff in Hans, but “the observation

was unnecessary to the decision, and in that sense extra

judicial, and, though made by one who seldom used words

without due reflection, ought not to outweigh the important

considerations referred to which lead to a different conclu

sion,” id. at 20.

In sum, the Hans court construed the Constitution to pre

clude federal question claims against the states only by

misreading the relevant historical and judicial sources, and

by expressly disagreeing with Chief Justice Marshall’s more

contemporaneous reading of the framers’ intent. Moreover,

the Hans opinion, which contains extensive passages about

state sovereignty, takes no account of the fact that on fed

eral questions, where the states have ceded power to the

“supreme” federal government, the states are not sovereign.

Considering the weakness of Hans’ foundations, It is not

surprising that Hans’ broad declaration collapsed upon first

impact with a federal question suit against a state brought

pursuant to a congressional conferral of jurisdiction to enter

tain such suits.

23

3. This C ourt has recognized the inapplicability of H ans where

Congress has expressly conferred jurisdiction to entertain

federal question suits against states.

It was not until 1963 that the collision came. Par den v.

Terminal R. Co., 377 U.S. 184 (1963), was a suit brought

under the Federal Employers’ Liability Act, a statute giving

railroad employees a federal cause of action for damages

suffered in the course of their employment. Following the

passage of the FELA, the State of Alabama acquired own

ership of a small railroad. An employee of that railroad,

injured in the course of his employment, brought suit for

damages under the FELA. The State of Alabama asserted

that the railroad was “an agency of the State and the State

had not waived its sovereign immunity from suit.” 377 U.S.

at 185.

The Court noted the legal issues, and their novelty, in

these words (id. at 187):

Here, for the first time in this Court a State’s claim

of immunity against suit by an individual meets a suit

brought upon a cause of action expressly created by

Congress. Two questions are thus presented: (1) Did

Congress in enacting the FELA intend to subject a

state to suit in these circumstances? (2) Did it have

the power to do so, as against the state’s claim of im

munity?

Answering the first question, the Court concluded that Con

gress in enacting the FELA intended its provisions to be

applicable to all railroads, “whether they are state owned

or privately owned.” (id. at 188).

The Court then turned to the second issue: whether

Congress has power, consistent with the Eleventh Amend

ment, to create a federal cause of action for damages against

a state. The Court began by rejecting Hans as controlling

authority, explaining that, however broadly worded the

Hans opinion, it must be understood in the context in which

26

gage in the interstate transportation business on a waiver of

the State’s sovereign immunity from suits arising out of

such business.” Id. at 198. The disagreement of the dis

senters was with the Court’s conclusion that Congress in

enacting the Federal Employers’ Liability Act had intended

to subject states so engaged to such suits.

That Congress may pursuant to its commerce power sub

ject states to suits in federal courts was again the founda

tion of this Court’s analysis in Employees v. Department

of Public Health, 411 U.S. 279 (1973). The Court dealt

there with the 1966 amendments to the Fair Labor Stand

ards Act, by Which Congress made the substantive provi

sions of the FLSA applicable to state hospital and educa

tional employees. The Court had already upheld the con

stitutionality of the substantive coverage, Maryland v. Wirtz,

392 U.S. 183 (1968), but had reserved the question whether

individuals could sue to recover unpaid wages, id. at 199-

200.

In Employees, the Court stated the issue as “whether

Congress has brought the States to heel, in the sense of lift

ing their immunity from suit in a federal court.” 411 U.S.

at 283. The Court concluded “that Congress did not lift the

sovereignty immunity of the States under the FLSA,” id.

at 285, because “we have found not a word in the history

of the 1966 amendments to indicate a purpose of Congress

to make it possible for a citizen of that state or another

state to sue the state in the federal courts,” and it “would

be . . . surprising . . . to infer that Congress deprived Mis

souri of her constitutional immunity without . . . indicating

in Some way by clear language that the constitutional im

munity was swept away,” ibid.18

18 This was also the conclusion in Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651

(1974), an action under 42 U.S.C. §1983, the Court finding that “the

threshold fact of congressional authorization to sue a class of defend

ants which literally include States is wholly absent,” id. at 672.

27

But the Court recognized in Employees that Congress has

power to lift the states’ immunity, id. at 286-287:

The Solicitor General, as amicus curiae, argues that

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1, should not be construed

to apply to the present cause, his theory being that in

Hans the suit was one to collect on coupons attaching

to state bonds, while in the instant case the suit is a

cause of action created by Congress and contained in

§16(b) of the Act. It is true that, as the Court said in

Parden, ‘the states surrendered a portion of their sov

ereignty when they granted Congress the power to reg

ulate commerce’. 377 U.S., at 191. But we decline to

extend Parden to cover every exercise by Congress of its

commerce power, where the purpose of Congress to give

force to the Supremacy Clause by lifting the sovereignty

of the states and putting the states on the same footing

as other employers is not clear (emphasis added).

We show in the next section that here the congressional

purpose to put the states “on the same footing as other em

ployers” is unmistakable. Thus, while the states are in gen

eral “sovereign” in their dealings with their own employees,

here Congress has “lifted their sovereignty” to the extent that

Title VII imposes obligations which must be met, and, as

part of that “lifting”, has made the states suable by ag

grieved employees for violations of those obligations. Before

turning to the evidence of that congressional decision, how

ever, it is important to note a significant difference in the

analysis required here from that in Parden and Employees.

The source of the congressional power here is the Fourteenth

Amendment. Whereas the Commerce Clause does not au

thorize Congress to regulate states per se, but only to regu

late interstate commerce, the Fourteenth Amendment does

authorize Congress to regulate the states directly. Only as

a state might elect to engage in interstate commerce would

it come within the ambit of the congressional power to cre

ate private “commerce” causes of action against it. But the

28

Fourteenth Amendment is different, for the states brought

themselves within its ambit, “consented” to Congress’ creat

ing a private cause of action against them pursuant to that

Amendment, when the Amendment was added to the Con

stitution. As the Court explained in Ex Parte Virginia, 100

U.S. at 346:

“The prohibitions of the 14th Amendment are di

rected to the States, and they are to a degree restric

tions of state power. It is these which Congress is em

powered to enforce, and to enforce against state action,

however put forth, whether that action be executive,

legislative or judicial. Such enforcement is no invasion

of state sovereignty. No law can be, which the people

of the States have, by the Constitution of the United

States, empowered Congress to enact.”

It is thus not necessary here, as it was in Parden, to find a

subsequent waiver of immunity by the states’ electing to

bring themselves within the ambit of congressional power.

The states are by definition within the sphere of Congress’

power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment.

B. Congress Clearly D ecided to Confer Federal Jurisdiction

Over Employee Actions Against States for Complete R e

lief, Including Backpay, for Violations of T itle VII.

Of course, that the states have ceded to Congress the

power to create private causes of action against them does

not mean that the federal courts may take jurisdiction of all

“federal question” actions against states. The lower federal

courts have only such jurisdiction as Congress opts to confer

upon them. Congress, sensitive to the extraordinary cession

of state sovereignty implicit in our federal scheme, has

treaded warily in conferring federal court jurisdiction over

private actions against states. See, e.g., Monroe v. Pape,

365 U.S. 187-192 (1961); Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S.

651, 675-677 (1974). This Court accordingly has demand

ed clear evidence of a congressional decision to authorize

private suits against states before concluding that Congress

29

has made the fateful judgment to “lift” the states’ immu

nity. Employees, supra, 411 U.S. at 285-286; Edelman,

supra, 415 U.S. at 674-677. See also Parden, supra, 377

U.S. at 198-199 (dissenting opinion).

Such clear evidence exists in the case of the 1972 amend

ments to Title VII. Congress not only amended the defini

tion of “employer” to add states and local governments, but

also amended the enforcement provisions, expressly making

governmental employers suable by the Attorney General or,

if he does not act within 180 days of the filing of a charge,

by aggrieved employees.19 In a section-by-section analysis

of the bill, the floor managers in the Senate (Senators Wil

liams and Javits) explained that the conferees had not

stopped with empowering the Attorney General to sue, but

had also allowed “the person aggrieved to elect to pursue

his or her own remedy under this title in the courts where

there is agency inaction, dalliance or dismissal of the charge,

or unsatisfactory resolution,” because “the individual’s

rights to redress are paramount under the provisions of

Title V II” and thus “it is necessary that all avenues be left

open for quick and effective relief.”20

19 As the Conference Report explained (S. Rep. No. 92-681, 92d

Cong. 2d Sess. 17-18 (1972); H. Rep. No. 92-899, 92d Cong. 2d Sess.

17-18 (1972)):

The conferees adopted a provision allowing the [Equal Employ

ment Opportunity] Commission, or the Attorney General in a case

against a state or local government agency, to bring an action in

Federal district courts if the Commission is unable to secure from

the respondent ‘a conciliation agreement acceptable to the Com

mission.’ Aggrieved parties are permitted to intervene. They may

bring a private action if the Commission or Attorney General has

not brought suit within 180 days or the Commission has entered

into a conciliation agreement to which such aggrieved party is not

a signatory. The Commission, or the Attorney General in a case

involving state and local governments, may intervene in such pri

vate action.

20 Section-By-Section Analysis of H.R. 1746, reprinted in Legislative

History of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, published

by the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, p. 1847.

3 0

The evidence of Congressional intent here is, of course,

markedly different from that found insufficient in Employees.

Although Congress in the 1966 amendments to FLSA had

amended the definition of “employer” to include state gov

ernments, it had not changed the enforcement provisions of

the statute. The Court, noting that there was “not a word in

the history of the 1966 amendments to indicate a purpose

of Congress” to permit private actions against states, was

unwilling to infer that Congress had “silently” lifted the

states’ immunity from suit. 411 U.S. at 285. Here, by con

trast, the evidence of congressional intent to permit private

actions is explicit. Furthermore, this Court relied in Em

ployees upon two additional considerations not present here:

(1) that “private enforcement of the Act was not a para

mount objective,” id. at 28621; and (2) that private actions

under the FLSA could yield twice the recovery of suits by

the Secretary of Labor: “it is one thing, as in Par den, to

make a state employee whole; it is quite another to let him

recover double against a state . . . . [W]e are reluctant to

believe that Congress in pursuit of a harmonious federalism

desired to treat the States so harshly,” id. at 286.22

Similarly, this case is altogether different from Edelman v.

Jordan {supra, n. 18), where the Court found “wholly

absent” the “threshold fact of congressional authorization to

21 In contrast, Congress created under Title V II a private cause of

action precisely because the private rights were deemed “paramount,”

Leg. Hist. 1847.

22 Under Title V II, by contrast, the remedies are the same whether

suit is brought by the Attorney General or by aggrieved employees, ex

cept that the latter may recover attorneys fees. Whether attorneys fees

are even a concern of the Eleventh Amendment is a question on which

a conflict of circuits exist (the court below holding that they are not)

and is the subject of the cross-petition in this case, No. 75-283. We

intend to file an amici curiae brief in No. 75-283, arguing that awards

of attorneys fees are never precluded by the Eleventh Amendment.

Rather than incorporating that argument into the instant brief, we

have opted to await the filing of the cross-petitioner’s brief, so that our

discussion can be responsive to the cross-petitioner’s contentions.

31

sue a class of defendants which literally includes States,”

415 U.S. at 672.

In sum, the Eleventh Amendment imposes no barrier to

private actions for backpay where, as here, (1) Congress has

acted within its enumerated powers in imposing a substan

tive obligation, (2) Congress has unmistakably created a

private cause of action in the federal courts to recover reme

dies from the states for violating that obligation, and (3) the

states are within the ambit of the congressional regulatory

power (either directly, as under the Fourteenth Amendment,

or by voluntarily bringing themselves within it, as in the

commerce cases).

G. The Foregoing Analysis Gains Additional Strength in This

Case Because the Cause of Action Was Created Pursuant

to the Fourteenth Amendment.

If we are right that Congress is empowered to create a

private cause of action against states in effectuation of any

of Congress’ enumerated powers, there is no need to examine

the special considerations which arise from the fact that the

Fourteenth Amendment was adopted after the Eleventh, and

that the cause of action involved here was created by Con

gress in the exercise of the authority conferred upon it by

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. But these special

considerations would compel the conclusion that the Elev

enth Amendment is inapplicable here, even if the Court dis

agreed with our broader contention.

1. The question whether the later enactment of the Fourteenth

A m endm ent brings it outside the scope of the Eleventh has

been recognized, but not decided, in prior cases.

The question whether the Eleventh Amendment is ap

plicable to suits for vindication of the Fourteenth was first

presented in Ex Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908). The

Court noted the question, but expressly refrained from de

ciding it {Id. at 150) :

“We think that, whatever the rights of complainants

may be, they are largely founded upon that [the Four

32

teenth] Amendment, but a decision in this case does not

require an examination or decision of the question

whether its adoption in any way altered or limited the

effect of the earlier [Eleventh] Amendment.”

Instead, the Court accorded complainants the relief they

sought by holding the Eleventh Amendment inapplicable to

suits for injunctive relief against state officers.

Remarkably, neither this Court nor any lower court had

occasion to discuss the question which Ex parte Young left

open until Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974). In

Edelman, Mr. Justice Marshall observed, in dissent, id. at

694, n. 2:

“It should be noted that there has been no determi

nation in this case that state action is unconstitutional

under the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus, the Court

necessarily does not decide whether the States’ Elev

enth Amendment sovereign immunity may have been

limited by the later enactment of the Fourtenth

Amendment to the extent that such a limitation is

necessary to effectuate the purposes of that Amend

ment, an argument advanced by an amicus in this

case.”

However, some lower courts, including the court below

(519 F.2d at 571), have construed the Court’s opinion in

Edelman as indeed determining the issue.23 They point to

the Court’s disapproval24 of three prior decisions25 in which

23 Jordan v. Gilligan, 500 F.2d 701, 709 (6th Cir. 1974); Skehan v.

Board of Trustees of Bloomsburg State Col, 501 F.2d 31, 42-43, n. 7

(3rd Cir. 1974).

24 415 U.S. at 670-671, and n. 13 thereat.

25 Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969), affirming 270 F.

Supp. 331, 338, n. 5 (D. Conn. 1967) ; State Depart, of Health and

Rehabilitation Services v. Zarate, 407 U.S. 918 (1972), affirming 347

F. Supp. 1004 (S.D. Fla. 1971); Wyman v. Bowens, 397 U.S. 49

(1970), affirming, 304 F. Supp. 717 (S.D. N.Y. 1969) (order at CCH

Poverty Law Rep. 1(10,506 [1968-1971 Transfer Binder]).

33

the Court had, without discussion of the sovereign immu

nity question, affirmed monetary awards against states for

violating the Fourteenth Amendment. But the cases dis

approved, although involving substantive violations of the

Fourteenth Amendment, did not arise under a statute where

in Congress had conferred jurisdiction over actions for

monetary relief against the states. On the contrary, each

arose under 42 U.S.C. §1983, a statute which does not

authorize suits against the states themselves.26 The Court in

Edelman declared the Par den analysis inapplicable to §1983

actions precisely because “the threshold fact of congressional

authorization to sue a class of defendants which literally in

cludes States is wholly absent.” 415 U.S. at 672: see also

id. at 675-677.

2. The later enactment of the Fourteenth A m endm ent would,

indeed, bring it outside the reach of the Eleventh, even if the

Eleventh otherwise precluded federal question actions

against states.

This case is thus the first to present squarely the issue left

open in Ex parte Young as to the relationship between the

Eleventh and Fourteenth Amendments. Here, Congress de

cided that a private cause of action against the states should

be created to implement the Fourteenth Amendment. Even

if the Eleventh Amendment deprives Congress of the power

to authorize such causes of action to effectuate those pro

visions of the Constitution which antedated that Amend

ment, that Amendment cannot restrict Congress’ power to

26 Cheramie v. Tucker, 493 F.2d 586, 587-588 (5th Cir. 1974);

Meyer v. State of New York, 344 F. Supp. 1377, 1379 (S.D. N.Y.

1971), affirmed, 463 F.2d 424 (2nd Cir. 1972) ; Dean Hill Country

Club, Inc. v. City of Knoxville, 379 F.2d 321, 324 (6th Cir. 1967),

cert, denied, 389 U.S. 975 (1967); United States ex rel. Lee v. State

of Illinois, 343 F.2d 120 (7th Cir. 1965) ; Sires v. Cole, 320 F.2d 877,