Owen v. City of Independence, MO Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Owen v. City of Independence, MO Brief Amici Curiae, 1979. e748f17b-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/474bd207-bc08-4285-8dbd-d434d689f0d9/owen-v-city-of-independence-mo-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

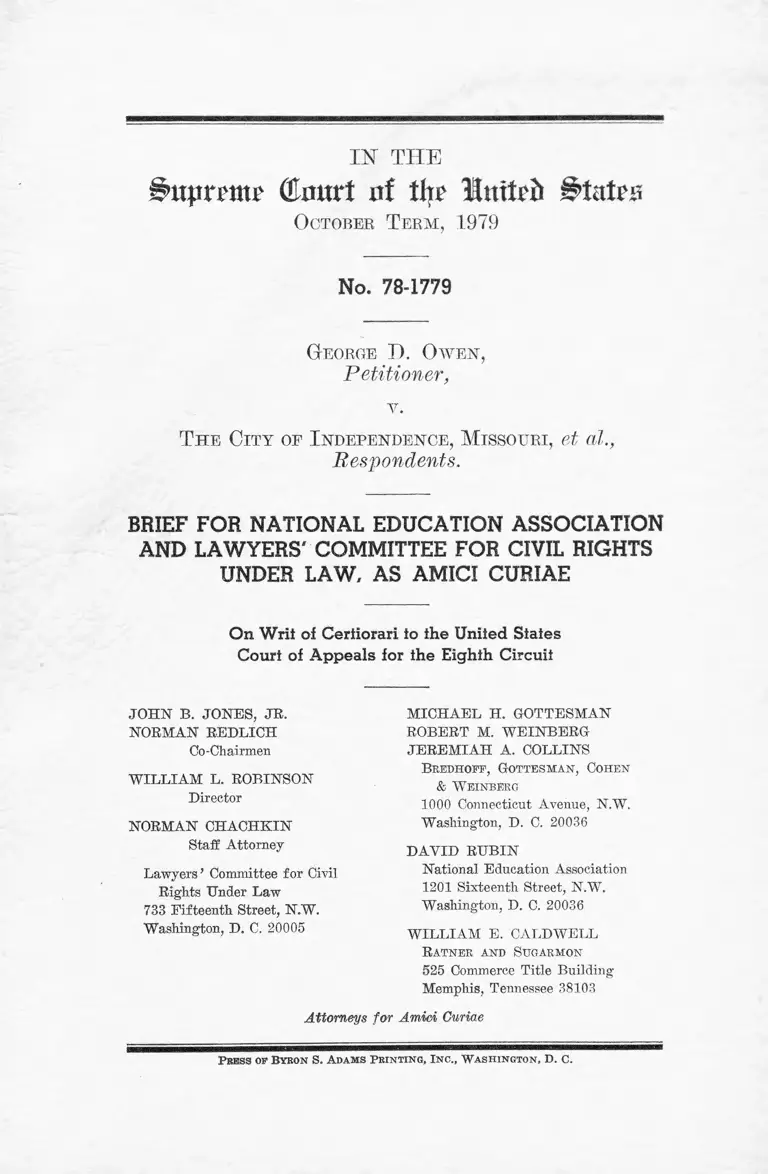

IN' THE

(Euurt o f % Im t r fi States

October Term , 1979

No. 78-1779

George D. Ow en ,

Petitioner,

v.

T he City op I ndependence, M issouri, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION

AND LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, AS AMICI CURIAE

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

JOHN B. JONES, JR.

NORMAN REDLICH

Co-Chairmen

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

Director

NORMAN CHACHKIN

Staff Attorney

Lawyers ’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

MICHAEL H. GOTTESMAN

ROBERT M. WEINBERG

JEREMIAH A. COLLINS

B kedhoff, Go ttesm a n , Cohen

& W einberg

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

DAVID RUBIN

National Education Association

1201 Sixteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Ratnek and Sttgarmon

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

P ress of B yron S. A d a m s P r in t in g , I n c ., W a s h in g t o n , D. C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

T a b l e o f C i t a t i o n s .................................................................................. i

I n t e r e s t o f t h e A m ic i C u r i a e ....................................................... 1

S u m m a r y o f A r g u m e n t .......................... 3

A r g u m e n t ....................................................................................................... 7

I. C o n g r e ss D id N o t I n t e n d M u n ic ip a l it ie s To H a ve

A n y I m m u n i t y I n § 1983 S u i t s ............................ 7

I I . T h e A r g u m e n t s F or I m p o r t in g A M u n ic ip a l D a m

a ge I m m u n i t y I n t o § 1983 A r e W it h o u t F o u n d a

t io n .................................................................. 17

A. “Extending” To Municipalities The Qualified

Immunity Enjoyed By Public Officials Against

Personal Liability ............................................. 17

B. Extrapolating A Qualified Immunity From The

Insulation Which Municipalities Enjoyed From

Certain Tort Actions At Common Law ........... 24

1. Sovereign Immunity (the Governmental/

Proprietary Distinction) ............................ 25

2. The Insulation of “Discretionary” Functions

From Negligence Suits.............................. 32

C o n c l u s i o n .............................................................................. 34

TABLE OF CITATIONS

C a se s :

Allen v. New York, 1 Fed. Cases 506 (S.D.N.Y. 1879) .. 11

Amey v. Allegheny County, 24 How. (65 U.S.) 364

(1861) .........'........................................................ 13

Bailey v. Mayor of New York, 3 Hill 531 (N.Y. 1842) . . 15

Barnes v. District of Columbia, 91 U.S. 540 (1876) . . . . 28

11 Table of Citations Continued

Page

Batchelder v. City of Salem, 58 Mass. 599 (1849) . . . . . 13

Beers v. Arkansas, 20 How. (61 U.S.) 527 (1858) ....... 30

Bertot v. School District No. 1, Albany County, Wyom

ing, Slip. Op. No. 76-1169 (November 15, 1978),

vacated pending rehearing en banc (1979)......... 20-23

Billings v. Worcester, 102 Mass. 329 (1869) ................ 20

Bissell v. City of Jeffersonville, 24 How. (65 U.S.) 287

(1861) .................................................................. 13

Bliss v. Brooklyn, 3 Fed. Cases 706 (E.D. N.Y. 1871) .. 11

Bradley v. Fisher, 13 Wall. (80 U.S.) 335 (1871) . . . . . . 18

Brown v. Rundlett, 15 N.H. 360 (1844) . .................. . 13, 20

Bunker v. City of Hudson, 122 Wis. 43, 99 N.W. 448

(1904) . ............................................................... 19-20

Butz v. City of Muscatine, 8 Wall. (75 U.S.) 575 (1869) 11

Campbell v. City of Kenosha, 5 Wall. (72 U.S.) 194

(1867) .................................................................. 14

Carr v. The Northern Liberties, 35 Penn. State 324

(1860) .................................................................. 33

Chicago v. Robbins, 2 Black (67 U.S.) 418 (1863) . . . . . 28

City of Aurora v. West, 7 Wall. (74 U.S.) 82 (1869) .. 14

City of Chicago v. Greer, 9 Wall. (76 U.S.) 726 (1870). 13

City of Crawfordsville v. Hayes, 42 Ind. 200 (1873) . . 13,20

City of Galena v. Amy, 5 Wall. (72 U.S.) 705 (1867) .. 14

City of Galveston v. Posnainsky, 62 Tex. 118 (1884) .. 26

City of Little Rock v. Willis, 27 Ark. 572 (1872)......... 33

City of Oklahoma City v. Hill Brothers, 6 Okla. 114,

50 P. 242 (1897) .................................................... 19

City of Providence v. Clapp, 17 How. (58 U.S.) 161

(1855) ................. 28

Commissioners of Knox County v. Aspinwall, 21 How.

(62 U.S.) 539 (1859) ............................................. 13

Table of Citations Continued iii

Page

Corp. of New York v. Ransom, 23 How. (64 U.S.) 487

(1860) ................................................................... 11

County Commissioner of Anne Arundel County v.

Duckett, 20 Md. 468 (1863) .................................... 20

County of Mercer v. Hackett, 1 Wall. (68 U.S.) 83

(i864) .................................................................. 14

County of Sheboygan v. Parker, 3 Wall. (70 U.S.) 93

(1866) ................................................................... 14

Curtis v. County of Butler, 24 How. (65 U.S.) 435

(1861) ................... 13

Danbury v. Norwalk RR Co. v. Town of Norwalk, 37

Conn. 109 (1870) .................................... 15

Darlington v. Mayor of New York, 31 N.Y. 164 (1865). . 12

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) ...................... 26

Elliot v. Concord, 27 N.H. 204 (1853) ..................... 20

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976) ..................... 31

Freeland v. City of Muscatine, 9 Iowa 461 (1859)....... 20

George v. School District No. 8, 20 Yt. 493 (1848) . . . . 13

Havemeyer v. Iowa County, 3 Wall. (70 U.S.) 294

(1866) ................................................................. 11

Hawkes v. Inhabitants of Charlemont, 107 Mass. 414

(1871) ............................................................. 20

Hodgson v. Dexter, 1 Cranch (5 U.S.) 345 (1803)___ 18

Holden v. Shrewsbury Sell. Dist. No. 10, 38 Vt. 529

(1866) .................................................... ............. 20

Horton v. Inhabitants of Ipswich, 66 Mass. 488 (Mass.

(1853) .................................................................. 20

Hurley v. Town of Texas, 20 Wis. 665 (1866).............. 19

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978).......................... 5, 24

Imbler v. Pachtman, 424 U.S. 409 (1976) ..................... 10

Inhabitants of Searsmont v. Farswell, 3 Maine 450

(1825) ........ 13

IV Table of Citations Continued

Page

Irvine v. Town of Greenwood, 89 S.C. 511 (1911) . . . . 28-29

Jackson v. Inhabitants of Hampden, 16 Maine 184

(1839) ................................................................... 13

Johnson v. State of California, 69 Cal.2d 782 (1968). . 23-24

Johnston v. District of Columbia, 118 U.S. 19 (1886) . . 33

Kawananakoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349 (1907).......... 30

Lake County Estates v. Tahoe Regional Planning

Agcy., 440 U.S. 391 (1979) ................................... 5, 24

Larned v. City of Burlington, 4 Wall. (71 U.S.) 275

(1867) ................................................................... 14

Lee v. Village of Sandy Hill, 40 N.Y. 442 (1869) . . . . . . 19

Levy Court of Washington County v. Woodward, 2

Wall. (69 U.S.) 501 (1865) .................................... 11

Lincoln County v. Tuning, 133 U.S. 529 (1890) ......... 26

Mason v. School District No. 14, 20 Vt. 487 (1848) . . . . 13

Mayor of Lyme v. Henley, 3 B. & Ad. 77 (1862) ......... 29

McGraw v. Town of Marion, 98 Ky. 673, 34 S.W. 18

(1896) .....................................„............................ 19

Mitchell v. City of Burlington, 4 Wall. (71 U.S.) 270

(1867) ................................................................... 11

Monell v. Department of Social Services of the City of

New York, 436 U.S. 658 (1978) ..........................passim

Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693 (1973)....... 26

Moran v. Miami Co., 2 Black (67 U.S.) 722 (1863)___ 14

Morrison v. McFarland, 51 Ind. 206 (1875) .................. 20

Mount Healthy City Board of Ed. v. Doyle, 429 U.S.

280 (1977) ............................................................. 26

Myer and Stucken v. City of Muscatine, 1 Wall. (68

U.S.) 384 (1864) ............................................... 14

Nebraska City of Campbell, 2 Black (67 U.S.) 590

(1862) ........................................................... 28

Table o f Citations Continued v

Page

O’Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563 (1975) .............. 10

Page v. Hardin, 8 B. Monroe 648 (Ky. 1844) .............. 20

Paul v. School District No. 2, 28 Vt. 575 (1856).......... 13

Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967) ............................ 10

Procunier v. Navarette, 434 U.S. 555 (1978)............... 10

Ransom v. Boston, 196 Mass. 248, 81 N.E. 998 (1907) .. 13

Richardson v. School District No. 10, 38 Vt. 602 (1866). 13

Riggs v. Johnson County, 6 Wall. (73 U.S.) 166 (1868). 15

Roach v. Commonwealth, 2 Dali. (2 U.S.) 206 (Pa.) . . . 11

Rogers v. City of Burlington, 3 Wall. (70 U.S.) 93

(1866) .................................................................. 14

Ruck v. Williams, 3 Ilurlst. & N. 308 (1858) ................ 18

Sala v. County of Suffolk, 604 F.2d 207 (2nd Cir.

1979) .................................................................. 25, 29

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974) ................... 10, 21

School District v. McComb, 18 Colo. 240 (1893) ......... 13

Schussler v. Board of Commissioners of Hennepin

County, 67 Minn. 412, 70 N.W. 6 (1897) ............... 19

Seibert v. Mayor of Pittsburg, 1 Wall. (68 U.S.) 272

(1864) ............................................................... 14

Shaw v. Mayor of Macon, 19 Gfa. 468 (1856) .............. 13, 20

Squiers v. Village of Neenah, 24 Wis. 588 (1869)....... 19

State of Missouri ex rel Cullen v. Carr, 3 Mo. App. 6

1876) .................................................................... 20

Stoddard v. Village of Saratoga Springs, 127 N.Y. 261,

27 N.E. 1030 (1891) ............................................... 19

Tenney v. Brandhove, 341 U.S. 367 (1951) . ................ 7,10

Thayer v. Boston, 19 Pick. 511 (Mass. 1837)............ 19, 20

Thompson v. County of Lee, 3 Wall. (70 U.S.) 327

(1866) ................................................. ............. 11

Town Council of Akron v. McComb, 18 Ohio 229 (1849) 19

VI Table of Citations Continued

Page

Trustees of the Town of Milford v. Simpson, 11 Ind.

520 (1858) ............................................................. 13

Von Hostrup v. City of Madison, 1 Wall. (68 U.S.) 291

(1864) ................................................................... 14

Walker v. Hallock, 32 Ind. 239 (1869).......................... 15

Weed v. Borough of Greenwich, 45 Conn. 170 (1877) . . 20

Weightman v. Washington, 1 Black (66 U.S.) 39

(1862) ................................................. 28,29,33

Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S. 308 (1975) . . . . 9-10, 21, 22, 23

Woodcock v. City of Calais, 66 Me. 234 (1877) ........... 20

Woods v. County of Lawrence, 1 Black (66 U.S.) 386

(1862) 13-14

C o n s t it u t io n a n d S t a t u t e s :

Constitution of the United States:

Contract Clause ................................................... 11

Eleventh Amendment............................................ 26

Fourteenth Amendment ......................................... 31

Civil Rights Act of 1871, § 1, 42 U.S.C. § 1983 . . . . passim

M is c e l l a n e o u s :

Bardeen, Common School Law (4th ed. 1888) ............ 13

Beach, Commentaries on the Law of Public Corpora

tions (1893) ............................................. 15,26,27,33

Burke, A Treatise on the Law of Public Schools (1880) 13

Cooley, Treatise on the Constitutional Limitations

(1868) ....... ......... ........... .............................26,27,33

Dillon, Treatise on the Law of Municipal Corporations

(1872) ................................................... 13,14-15, 26-27

Table o f Citations Continued Vll

Page

Note, Liability of Cities for the Negligence and Other

Misconduct of Their Officer sand Agents, 30 Am.

St. Rep. 376 (1893) .........................................20,27-28

Note, On the Patent Laws, 4 L.ed. 488 ......................... 11

Note, Right of One Whose Property Has Been Taken

for Public Use Without His Consent and Without

Condemnation Proceedings to Maintain Action for

Compensation or for Permanent Damages, 28

L.R.A. (N.S. 968 (1910) ....................................... 12

Note, Streets, Change of Grade, Liability of Cities, 30

Am. St. Rep. 835 (1892)......................................... 12

Shearman & Redfield, A Treatise on the Law of Negli

gence (1869) ................................. 15,17, 25, 27, 32-33

Taylor, Public School Law of the United States 295

(1892) ................................................................... 13

IN THE

i? u |trrm r C o u r t o f tljr lu ttrfc S t a ir s

October T erm, 1979

No. 78-1779

G eorge D. Ow en ,

Petitioner,

v.

T he City of I ndependence, M issouri, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION

AND LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, AS AMICI CURIAE

On Writ of Certiorari to the United Stales

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE1

The National Education Association (NEA) is the

largest teacher organization in the United States, with

a membership of approximately 1.7 million educators,

virtually all of whom are employed by public educa

1 Consents of all parties to the filing of this brief have been filed

with the Clerk.

2

tional institutions. One of N EA’s purposes is to safe

guard the constitutional rights of teachers and other

public educators.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under

Law is a non-profit corporation organized in 1963 at

the request of President Kennedy. Its Board of Trus

tees includes several past presidents of the American

Bar Association, two former Attorneys General, and a

former Solicitor General of the United States. The

Committee’s primary mission is to involve private

lawyers throughout the country in the quest of all

citizens to secure their civil rights through the legal

process.

The resolution of this case will have an important

impact upon the extent to which those who are injured

by the unconstitutional actions of public officials and

entities can secure complete relief in the federal courts.

Both amici have a vital interest in the resolution of this

case.

Pursuant to that same interest these amici filed a

brief in Monell v. Department of Social Services of the

City of New York, 436 U.S. 658 (1978). In Monell

this Court held that municipalities are “ persons” and

can be sued directly under § 1983 for monetary relief.

The Court left open, however, the question whether

municipalities should be afforded any form of qualified

immunity in such suits. That question is presented in

the instant case, and its resolution will determine

whether complete relief is, indeed, available in the

federal courts to those who suffer injuries from uncon

stitutional actions of municipalities.

This brief is filed to provide the Court with the views

of the amid, refined through extensive litigation under

3

the Fourteenth Amendment and 42 U.S.C. § 1983, that

municipalities do not enjoy any form of immunity from

damage liability for violations made actionable by

§ 1983.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. The question here is solely one of statutory inter

pretation : Did the Congress that enacted § 1983 intend

to provide municipalities with some form of immunity

against liability for damages in § 1983 suits'? Congress

intended no such immunity. The words of § 1983—that

municipalities “ shall be liable to the party injured in

an action at law” —are broadly remedial and contain

no indication of a congressional intention to adopt an

immunity for municipalities. And, Congress knew that

the statute would subject municipalities to monetary

liability, yet there was not a mention in the entire

course of legislative consideration of the bill that mu

nicipalities would or should have any immunity in suits

under § 1983.

Further, there was no “ tradition” of any municipal

immunity “ so well grounded in history and reason”

that the 1871 Congress must be assumed to have sub

silentio incorporated an immunity into its enactment

—indeed, the “ tradition” was that wherever munici

palities were subject to suit, which by 1871 was a broad

range of cases, they had no immunity of any kind. As

of 1871, municipalities were subject to suit for every

breach of contract, for every violation of constitution

or statute (whether state or federal), and for a wide

range of torts. In all instances where they were subject

to suit, municipalities had no immunity of any kind

against damage awards. Particularly pertinent here,

4

it was well established as of 1871 that enactment of a

statute imposing liability on municipalities did not

carry with it any implicit damage immunity; whenever

municipalities were made subject to damage liability

by statute, that liability was enforced without extend

ing any immunity to the municipalities. Congress can

not be assumed to have silently intended that the enact

ment of § 1983 would carry with it an immunity for

municipalities which did not then exist with respect to

any other cause of action against municipalities.

II. The court below, and others, without having es

tablished the necessary predicate of legislative intent,

have nevertheless held that § 1983 provides municipali

ties a qualified damage immunity, basing their holdings

upon one or the other of two distinct rationales. Neither

of these rationales furnishes a proper justification for

importing any kind of municipal damage immunity

into § 1983.

A. There is no basis for “ extending” to municipali

ties the qualified immunity enjoyed by public officials

against personal liability. Nothing could be plainer

than that as of 1871 the good faith immunity enjoyed

by public officials was wholly inapplicable to damage

awards against the public treasury. The English courts,

which had established the public official immunity doc

trine later followed by the American courts, had re

peatedly declared the doctrine “ inapplicable” to dam

age awards against the public treasury. The American

cases similarly recognized the propriety of awarding

damages against municipalities notwithstanding that

the wrong was committed in the good faith and reason

able belief that it was lawful.

Further, the reasons which underlie the common-law

qualified immunity for public officials in their individ

5

ual capacity do not justify a similar immunity for

governmental entities. And, twice recently this Court

has recognized that fact. Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678,

699, n. 32 (1978); Lake County Estates v. Talioe Re

gional Planning Agcy., 440 U.S. 391, 405 n. 29 (1979).

B. There were two common law doctrines which insu

lated municipalities from certain types of tort actions

altogether, regardless of the relief sought (injunctive

or monetary). Neither could have formed a predicate

for an unexpressed congressional intent to qualify the

damage liability of municipalities, in § 1983 actions.

1. The sovereign immunity enjoyed by municipalities

at common law with respect to certain of their func

tions affords no basis for imputing to Congress an un

stated intention to limit the amenability of municipali

ties to damage awards under § 1983. Sovereign immu

nity was not a damage immunity. Its effect, where it

applied, was to insulate the municipality from suit al

together. The doctrine’s existence did not reflect a pru

dential judgment about the desirability of holding mu

nicipalities accountable for their torts; rather, it re

flected a matter of power-—as the sovereign made the

law, it could be sued only if and to the extent it chose

to subject itself to the law it made. Given the nature of

that immunity, it was by definition abrogated by enact

ment of a statute by the state (or, where, as here, fed

eral power exists, the federal government) subjecting

a municipality to suit. Such enactments by states were

widespread as of 1871, and their effect was to make

municipalities liable in damages without immunity.

There is no basis for attributing to Congress a differ

ent intention when it made municipalities suable in this

statute.

6

2. There was also at common law a doctrine insulat

ing municipalities from tort suits challenging “ discre

tionary” decisions. This was not an immunity; rather,

it defined what constituted a cause of action and what

did not. I f the law of negligence had been made applic

able to every decision of a municipality, then the legis

lative judgments of the elected officials could have been

subjected to judicial review on a claim they were not

“ reasonable,” and judges and juries could thereby have

second-guessed and overturned discretionary decisions

entrusted to the legislature. To protect against this,

the courts carved out those functions which were com

mitted to a governmental entity’s legislative “ discre

tion” and made them not subject to suit (for injunc

tive or monetary relief) under the “ reasonable man”

standard. But the rationale of the “ discretionary func

tion” doctrine also defined its limits. Where a munici

pality was subject to “ duties which are absolute and

imperative in their nature,” there was no protection

against injunction or damages for “ non-performance

or mis-performance. ” The doctrine is thus by its terms

inapplicable to § 1983. Municipalities do not have dis

cretion to violate the federal Constitution. The inquiry

under § 1983 is not whether public decisions are “ rea

sonable,” but whether they are in violation of the fed

eral Constitution and/or federal statutes. The very

purpose of § 1983 was to vest the federal courts with

the power to conduct this inquiry. The “ discretionary

function” doctrine cannot justify a presumption that

Congress silently intended to create a qualified immu

nity for municipalities from damage liability under

§ 1983.

7

ARGUMENT

I. CONGRESS DID NOT INTEND MUNICIPALITIES TO HAVE

ANY IMMUNITY IN § 1983 SUITS.

In this brief we address only the question whether

municipalities 2 have some form of immunity in actions

brought against them under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which

was enacted as part of § 1 of the Civil Rights Act of

1871. The question is solely one of statutory interpre

tation : Did the Congress that enacted § 1983 intend to

provide municipalities with some form of immunity

against liability for damages in § 1983 suits ? As we

show below, Congress intended no such immunity.

There is no warrant in the language of § 1983 or in its

legislative history for finding a congressional inten

tion to establish such an immunity; and, there was no

“ tradition” of any such immunity “ so well grounded

in history and reason” 3 that the 1871 Congress must

be assumed to have sub silentio incorporated an im

munity into its enactment—-indeed, the “ tradition”

was that wherever municipalities were subject to suit,

which by 1871 was in a broad range of cases, they

simply had no immunity of any kind.

The words of § 1983 are broadly remedial and con

tain no indication of a congressional intention to adopt

an immunity for municipalities:

2 Throughout this brief, we use the term “ municipalities” to

include all forms of local government: cities, counties, school dis

tricts, etc. This Court drew no distinction between the various

forms of local government in Monell, concluding that all were

embraced within the statutory term “ person,” 436 U.S. at 690.

The analysis we proffer herein likewise would warrant no distinc

tion between them with respect to the immunity question.

3 Tenney v. Brandhove, 341 U.S. 367, 376 (1951).

8

Every person who, under color of any statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any

State or Territory, subjects, or causes to be sub

jected, any citizen of the United States or other

person within the jurisdiction thereof to the depri

vation of any rights, privileges, or immunities se

cured by the Constitution and laws, shall he liable

to the party injured in an action at law, suit in

equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.

[Emphasis added].

The congressional debates which culminated in pas

sage of this provision confirm Congress’ intent that

these statutory words were to be given their full sweep.

The Act’s author and manager in the House, Repre

sentative Shellabarger, in his speech introducing the

bill, explained the breadth of construction which was

contemplated—an explanation which was quoted in

Monell v. New York City Dept, of Social Services, 436

U.S. 658, 684 (1978), and bears repeating here:

This act is remedial, and in aid of the preserva

tion of human liberty and human rights. All stat

utes and constitutional provisions authorizing such

statutes are liberally and beneficently construed.

It would be most strange and, in civilized law,

monstrous were this not the rule of interpretation.

As has been again and again decided by your own

Supreme Court of the United States, and every

where else where there is wise judicial interpre

tation, the largest latitude consistent with the

words employed is uniformly given in construing

such statutes and constitutional provisions as are

meant to protect and defend and give remedies

for their wrongs to all the people. . .. Chief Justice

Jay and also Story say:

‘ Where a power is remedial in its nature there

is much reason to contend that it ought to be con

strued liberally, and it is generally adopted in the

9

interpretation of laws’ Story on Constitution, see.

429.

This view of the sweep of the bill was voiced by its

sponsors (and acknowledged by its opponents)

throughout the debates in passages cited in Monell, 436

IT.S. at 683-687 and note 45. A repeated theme was

that the provision represented the exercise of the entire

power which Congress possessed under the Constitu

tion to remedy violations of that Constitution. Ibid.

The 1871 Congress made a positive determination

to subject municipalities to suits under § 1983. Id. at

686, 690. And, that Congress knew that municipalities

would be subject to monetary liability in such suits.

Id. at 690. Yet, there was not a mention in the entire

course of legislative consideration of the bill that mu

nicipalities would or should have any immunity in suits

under § 1983.

The silence of the statute and in the debates on the

subject of an immunity for municipalities is of course

powerful evidence that none was intended. But con

gressional intent may sometimes be discerned from

other sources. That has proven to be true with respect

to the personal immunities which this Court has found

are enjoyed by public officials under § 1983. This Court

has found that at the time of the enactment of § 1983,

the state of the law was that many public officials were

immunized, either absolutely or qualifiedly, from per

sonal liability for their official acts. When this Court

encountered damage claims against such officials, it

was confronted with the question whether the 1871

Congress intended, sub silentio, that the existing per

sonal immunities would be applicable in suits under

§ 1983. The Court recognized that this “ immunity ques

10

tion involves the construction of a federal statute. ..

Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S. 308, 314 (1975). The

question thus was not whether an immunity might

make sense as a policy matter, but whether Congress

intended its inclusion in § 1983. Where an immunity

was well established in 1871 and its rationale compati

ble with the purposes of § 1983, this Court “ presume[d]

that Congress would have specifically so provided had

it wished to abolish the doctrine.” Pierson v. Bay, 386

U.S. 547, 555 (1967). Using the words of Mr. Justice

Frankfurter in the seminal case on this issue, Tenney

v. Brandhove, 341 U.S. 367, 376 (1951), where there

was in 1871 a “ tradition” of an immunity “ so well

grounded in history and reason” that “ [w]e cannot

believe Congress . . . would [have] impinge[d]” upon

it by “ covert inclusion in the general language [of

§ 1983],” §1983 was construed to incorporate that

immunity.4

The claim that the 1871 Congress must have intended

municipalities to have some form of immunity in § 1983

suits has not previously been resolved by this Court.

It is our submission that this claim founders on the

most basic threshold proposition: there was simply no

immunity for municipalities that the 1871 Congress

could have assumed it was incorporating in § 1983.

+ On that basis, the Court in Tenney concluded that § 1983

adopted the absolute immunity of legislators as to what they do

or say in legislative proceedings. Applying the same analysis, this

Court has found § 1983 to provide an absolute immunity for judges,

Pierson v. Ray, supra, and prosecutors, Imbler v. Pachtman, 424

U.S. 409, 424 (1976), and a qualified immunity for other cate

gories o f public official. Pierson, supra; Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416

U.S. 232 (1974); Wood v. Strickland, supra; O’Connor v. Donald

son, 422 U.S. 563 (1975); Procunier v. Navarette, 434 U.S. 555

(1978).

11

Congress may not be found to have incorporated in its

enactment, sub silentio, an immunity which did not

exist.

As of 1871, municipalities were suable for most of

their actions. They were subject to suit for every breach

of contract, for every violation of constitution or stat

ute, whether federal or state, and for a wide range of

torts.5 And, in all instances where they were subject

5 Federal Constitutional Violations. The most important provision

of the federal Constitution, prior to the Reconstruction Amend

ments, imposing duties upon municipalities was the Contract

Clause. As was observed in Monell, 436 U.S. at 681, the federal

courts “ vigorously enforced the Contract Clause against munici

palities— an enforcement effort which included various forms of

‘ positive ’ relief, such as ordering that taxes be levied and collected

to discharge federal-court judgments, once a constitutional infrac

tion was found.” In addition to the cases cited in Monell, id. at

673, n. 28, see Iiavemeyer v. Iowa County, 3 Wall. (70 U.S.) 294,

303 (1866); Thompson v. County of Lee, 3 Wall. (70 U.S.) 327,

330 (1866); Mitchell v. City of Burlington, 4 Wall. (71 U.S.) 270

(1867) ; Butz v. City of Muscatine, 8 Wall. (75 U.S.) 575, 584

(1869).

Federal Statutory Violations. Federal patent laws were in effect

from 1790 on. Note, On the Patent Laws, 4 L.ed. 488. Damage

actions against municipalities for infringement of patent were com

mon, and the remedial standards were identical to those applied in

suits against private defendants. See, e.g., Corp. of New York v.

Ransom, 23 How. (64 U.S.) 487 (1860) ; Bliss v. Brooklyn, 3 Fed.

Cases 706 (E.D. N.Y. 1871); Allen v. New York, 1 Fed. Cases 506

(S.D.N.Y. 1879). We found no other federal statute of broad

applicability which imposed duties upon municipalities prior to

1871, and which thus could have produced litigation seeking mone

tary relief from municipalities. For two narrow federal statutes

which led to monetary judgments, see Roach v. Commonwealth,

2 Dali. (2 U.S.) 206 (Pa.) (judgment against State, prior to adop

tion of Eleventh Amendment) ; Levy Court of Washington County

v. Woodward, 2 Wall. (69 U.S.) 501 '(1865).

State Constitutions. Most state constitutions contained a provi

sion prohibiting takings without just compensation. These provi-

12

to suit, regardless of the form of the action, municipali

ties had no immunity of any kind against damage

awards; in all such suits, their liability in damages was

sions were regularly enforced against municipalities through dam

age awards. Note, Eight of One Whose Property Has Been Taken

for Public Use Without His Consent and Without Condemnation

Proceedings to Maintain Action for Compensation or for Perma

nent Damages, 28 L.R.A. (N.S.) 968 (1910). During the 1870’s,

many state constitutions were amended to broaden the “ just com

pensation” principle beyond literal “ takings” to property injuries

inflicted incidentally (e.g., by regrading the streets so that a mer

chant’s store was no longer accessible to the public). The state

courts “ have been unanimous in holding that under such consti

tutional provision a city is liable to [the property owner] for all

direct and consequential damage arising from its action in grading

or changing the grade o f its streets, unless he is compensated under

the power of eminent domain before the work is done . . . ” Note,

Streets, Change of Grade, Liability of Cities, 30 Am. St. Rep. 835,

837 (1892) (citing cases).

State Statutes. State statutes imposed many obligations upon

municipalities, the violation of which was enforceable by damage

action. The statutes authorizing suits for damages for a municipal

ity ’s failure to prevent a riot, the analogue upon which the Sher

man Amendment had been modeled, was much discussed during the

debates on § 1983, Monell, 436 U.S. at 667-668, n. 17, as was the

New fo rk Court of Appeals’ 1865 decision rejecting a city ’s claim

that the statute violated the city ’s right to due process under the

state constitution, Darlington v. Mayor of New York, 31 N.Y. 164

(1865) (see passages cited in Monell, at 667-668, n. 17). In some

states, the extension of the “ just compensation” principle to non

takings was accomplished by state statute, rather than constitu

tional amendment. Note, Streets, Change of Grade, supra, 30 Am.

St. Rep. at 848-849. State statutes restricting the grounds for dis

charging municipal employees, or requiring due process incident

to discharge, gave rise to damages in actions denominated “ con

tract” (see below under “ Employment Cases” ). And, most im

portantly, state statutes were applied widely to sustain tort damage

awards (see below under “ Torts” , and infra, pp. 27-30).

Employment Cases. Claims of wrongful discharge by municipal

employees invariably were treated as “ contract” actions, and dam-

13

understood to be identical to that of private corpora

tions and private individuals. There were, to be sure,

two common law doctrines which insulated certain mu-

ages were regularly awarded against muncipalities for wrongful

discharge. Thus an 1880 treatise stated: “ Where [a] teacher is

wrongfully dismissed on charge of incompetency or any similar

charge, he is entitled to recover from the district his wages for the

balance of the term contracted for. ’ ’ Burke, A Treatise on the Law

of Public Schools 84 (1880). Accord, Bardeen, Common School

Law 46 (4th ed. 1888) ; Taylor, Public School Law o f the United

States 295 (1892). Many of these were true “ breach of contract”

actions. See, e.g,, Mason v. School District No. 14, 20 Yt. 487

(1848) ; George v. School District No. 8, 20 Vt. 493 (1848) ;

Richardson v. School District No. 10, 38 Vt. 602 (1866) ; Batchel-

der v. City of Salem, 58 Mass. 599 (1849); Trustees of the Town

of Milford v. Simpson, 11 Ind. 520 (1858) ; City of Crawfordsville

V. Hayes, 42 Ind. 200 (1873) ; Brown v. Rundlett, 15 N.TI. 360,

370 (1844). But many were really actions for violation of statutes

requiring due process, or restricting the grounds for discharge, and

damages were awarded for such statutory violations under the

rubric “ breach of contract.” See, e.g., Paul v. School District No. 2,

28 Vt. 575, 578-580 (1856) (statute construed to limit grounds to

incompetency or unfaithfulness) ; Inhabitants of Searsmont v. Far-

well, 3 Maine 450 (1825) (statute limiting grounds) ; Shaw v.

Mayor of Macon, 19 6a. 468, 469 (1856) (same) ; Jackson v. In

habitants of Hampden, 16 Maine 184 (1839) (dismissal without

adherence to statutory procedures) ; School District v. McComb,

18 Colo. 240 (1893) (same) ; Ransom v. Boston, 196 Mass. 248, 81

N.E. 998 (1907) (same).

Contract Cases Generally. “ Upon authorized contracts,” munici

palities were “ liable in the same manner, and to the same extent,

as private corporations or natural persons. ’ ’ Dillon, Treatise on the

Law of Municipal Corporations 702 (1872). See also Burke, A

Treatise on the Law of Public Schools 66-67 (1880) ; City of Chi

cago v. Greer, 9 Wall. (76 IJ.S.) 726 (1870). The most frequently

litigated breach of contract actions, at least in federal court, were

those for failure to pay interest on municipal bonds. Commissioners

of Knox County v. Aspinwall, 21 How. (62 U.S.) 539 (1859) ;

Amey v. Allegheny County, 24 How. (65 U.S.) 364 (1861) ; Bissell

V. City of Jeffersonville, 24 How. (65 U.S.) 287 (1861); Curtis v.

County of Butler, 24 How. (65 U.S.) 435 (1861) ; Woods v. County

14

nicipal functions from suit in tort, for any type of

relief (injunctive as well as monetary). We discuss

these infra, at pp. 25-34, and show that they have

of Lawrence, 1 Black (66 U.S.) 386 (1862) ; Moran v. Miami Co.,

2 Black (67 U.S.) 722 (1863) ; Von Hostrup v. City of Madison,

1 Wall. (68 U.S.) 291 (1864) ; County of Mercer v. Hackett, 1

Wall. (68 U.S.) 83 (1864); Seibert v. Mayor of Pittsburg, 1 Wall.

(68 U.S.) 272 (1864) ; Myer and Stuchen v. City of Muscatine,

1 Wall. (68 U.S.) 384 (1864) ; County of Sheboygan v. Parker,

3 Wall. (70 U.S.) 93 (18C6) ; Rogers v. City of Burlington, 3 Wall.

(70 U.S.) 93 (1866) ; Lamed v. City of Burlington, 4 Wall. (71

U.S.) 275 (1867) ; Campbell v. City of Kenosha, 5 Wall. (72 U.S.)

194 (1867) ; City of Aurora v. West, 7 Wall. (74 U.S.) 82 (1869).

A city ’s plea that execution of judgment would cause it great harm

met with this response from the Supreme Court:

The Counsel for the [city] has called our attention, with em

phasis and eloquence, to the diminished resources of the city,

and the disproportionate magnitude of its debt. Much as. per

sonally, we may regret such a state of things, we can give no

weight to considerations of this character, when placed in the

scale as a counterpoise to the contract, the law, the legal rights

of the creditor, and our duty to enforce them. Such securities

occupy the same ground in this Court as all others which are

brought before us. When clothed with legal validity it is our

purpose to sustain them, and to give to their holders the bene

fit of all the remedies to which the law entitles them . . .

[W ]e cannot recognize a distinction, unknown to the law,

between this and any other class of obligations we may be

called upon to enforce.

City of Galena v. Amy, 5 Wall. (72 U.S.) 705, 710 (1867).

Torts. As explained infra, pp. 25-31, the common law divided the

functions of municipalities into two categories, “ governmental”

and “ proprietary,” and rendered municipalities suable for tort

only with respect to their “ proprietary” functions (the “ govern

mental” functions being shielded by the state’s sovereign immu

nity). However, as also explained infra, pp. 27-30, the states by

statute withdrew sovereign immunity with respect to many “ gov

ernmental” functions, thus giving rise to a body of statutory tort

law which was well developed by 1871. Wherever municipalities

were suable, they were liable for their negligent acts ‘ ‘ on the same

principles and to the same extent as a private corporation. ’ ’ Dillon,

15

no relevance to the construction of § 1983. The point

at this juncture is that it was well understood that this

common law insulation was overridden by the enact

ment of a statute making municipalities accountable

in court, and such statutes were widespread as of 1871.

The enactment of such a statute did not carry with it

any implicit damage immunity for municipalities;

when municipalities were made subject to statutory

liabilities in damages, these liabilities were enforced

without extending any immunity to the municipalities.6

Congress cannot be assumed to have thought that the

enactment of § 1983 would carry with it an immunity

for municipalities that did not exist under other forms

of statutory liability.

Treatise on the Law of Municipal Corporations 33 (1872). Accord:

Beach, Commentaries on the Law of Public Corporations 265

(1893); Shearman & Redfield, A Treatise on the Law of Negligence

139, 149, 159 (1869) ; Bailey v. Mayor of New York, 3 Hill 531,

538-539 (N.Y. 1842); Danbury v. Norwalk RR Co. v. Town of

Norwalk, 37 Conn. 109, 119 (1870). Similarly, “ [i]n regard to the

use of its corporate property, a municipal corporation [was] bound

to an observance of the same rules which the law impose [d] on

individuals,” and was therefore “ responsible, as an individual

would be under the same circumstances, for the creation and main

tenance of a public nuisance, and [was] liable to a public prosecu

tion, or to a private action at the suit of any one specially injured

thereby.” Shearman & Redfield, supra at 181. See also Walker v.

Hallock, 32 Ind. 239, 244 (1869). And, “ the federal courts found

no obstacle to awards of damages against municipalities for com

mon-law takings.” Monell, 436 U.S. at 687, n. 47. For an indication

of the enormous volume of tort damage awards which had been

rendered against municipalities as of 1871, see generally the cases

and materials cited infra at pp. 19-20, 27-28.

Execution of Monetary Judgments Against Municipalities. For a

comprehensive description of the manner in which federal and

state courts achieved execution of monetary judgments against

municipalities as of 1871, see Riggs v. Johnson County, 6 Wall.

(73 U.S.) 166 (1868). See also Monell, 436 U.S. at 674, n. 30.

6 See infra, pp. 19-20, 27-29.

16

It is important to understand how we derived cer

tain of the propositions set forth in the preceding

paragraph. There were literally thousands of reported

eases as of 1871 awarding damages against municipali

ties for wrongs they were found to have committed. We

do not purport to have read all of them. We have read

several hundred of those cases and examined contem

poraneous treatises discussing thousands more. We did

not find a single case in which a municipality was held

to have committed an actionable wrong and yet was in

sulated from paying damages from those injured by

that wrong. Indeed, there appear to have been only a

handful of cases in which the question of a damage

immunity for municipalities was even addressed, and

in each it was rejected out of hand.7 It is always difficult

to prove a negative; we cannot say that no case exists

in which some court found some municipality immune

from damages; we can only say that we could not find

one and the treatises do not mention any. But the

question here is whether there was a municipal im

munity from damages so well established in the law

of the time that Congress must have intended to adopt

it as part of § 1983. That question can be answered

definitively: if there were such an immunity, there

would not have been a multitude of cases where munici

palities were found to be liable in damages without even

asserting the immunity; and, there would not have been

uniform rejection of the existence of the immunity in

those rare cases we could find where it was asserted.

In § 1983, Congress enacted a statute that declares

without qualification that municipalities “ shall be li

able” to parties injured by violations of federal Con

7 See infra, pp. 18-20.

17

stitutional or statutory duties “ in an action at law,

suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.”

There is no basis for attributing to Congress an Tin-

stated intention to qualify the statutory declaration by

conferring upon municipalities an immunity that did

not exist elsewhere in the law. Nevertheless, the court

below, and others, without having established the neces

sary predicate of legislative intent, have found it ap

propriate to adopt such an immunity, based upon one

or the other of two distinct rationales. We discuss these

rationales separately below, and show the impropriety

of adopting an immunity for municipalities based on

either.

II. THE ARGUMENTS FOR IMPORTING A MUNICIPAL DAM

AGE IMMUNITY INTO § 1983 ARE WITHOUT FOUNDATION.

A. "Extending" To Municipalities The Qualified Immunity

Enjoyed By Public Officials Against Personal Liability

The court below chose to “ extend the limited im

munity [enjoyed by] the individual defendants to

cover the City as well,” 589 E.2d at 338. No explana

tion was proffered below for this extension, and noth

ing eoidd be plainer than that as of 1871 the good faith

immunity enjoyed by public officials sued in their in

dividual capacity—an immunity which had evolved

out of concern for “ the harshness and impolicy of cast

ing on individuals a public duty, and making them re

sponsible out of their private means for the non-fulfill

ment of it” 8 *— was wholly inapplicable to damage

awards against the public treasury. The English courts,

8 Shearman & Redfield, A Treatise on the Law of Negligence 209

(1869).

18

which had established the official immunity doctrine

later followed by the American courts,9 had repeatedly

declared the doctrine “ inapplicable” to damage awards

against the public treasury.10 As Baron Bramwell ex

plained in Ruck v. Williams, 3 Hurlst. & N. 308, 319

(1858) :

I can well understand if a person undertakes

the office or duty of a Commissioner, and there are

no means of indemnifying him against the conse

quences of a slip, it is reasonable to hold that he

should not be responsible for it. I can also under

stand that, if one of several Commissioners does

something not within the scope of his authority,

the Commissioners as a body are not liable. But

where Commissioners, who are a quasi corporate

body, are not affected (i.e. personally) by the re

sult of an action, inasmuch as they are authorized

by act of parliament to raise a fund for payment

of the damages, on what principle is it that, if an

individual member of the public suffers from an

act bona fide but erroneously done, he is not to be

compensated? It seems to me inconsistent with

actual justice, and not warranted by any principle

of law.

The American cases similarly recognized the pro

priety of awarding damages against municipalities

notwithstanding that the wrong was committed in the

good faith and reasonable belief that it was lawful.

The most cited statement of the principle was Chief

9 See Hodgson v. Dexter, 1 Cranch (5 U.S.) 345, 363-3G4 (1803) ;

Bradley v. Fisher, 13 Wall. (80 U.S.) 335, 347-353 (1871).

10 Shearman & Redfield, supra, at pp. 208-210, and cases cited in

n. 1 thereat.

19

Justice Shaw’s opinion in Thayer v. Boston, 19 Pick.

511, 515-516 (Mass. 1837) :

There is a large class of cases, in which the rights

of both the pumic and of individuals may be deeply

involved, in which it cannot be known at the time

the act is done, whether it is lawful or not. The

event of a legal inquiry, in a court of justice, may

show that it was unlawful. Still, if it was an act

done by the officers having competent authority,

either by express vote of the city government, or

by the nature of the duties and functions with

which they are charged, by their offices, to act upon

the general subject matter, and especially if the

act was done with an honest view to obtain for the

public some lawful benefit or advantage, reason

and justice obviously require that the city, in its

corporate capacity, should be liable to make good

the damages sustained by an individual, in conse

quence of the acts thus done. It would be equally

injurious to the individual sustaining damage, and

to the agents and persons employed by the city

government, to leave the party injured no means

of redress, except against agents employed, and

by what at the time appeared to be competent au

thority, to do the acts complained of, but which

are proved to be unauthorized by law.

Accord: Town Council of Akron v. McComh, 18 Ohio

229, 230-231 (1849) ; Hurley v. Town of Texas, 20 Wis.

665, 669-670 (1866); Squiers v. Village of Neenah, 24

Wis. 588, 593 (1869) ; Lee v. Village of Sandy Hill, 40

N.Y. 442, 448-451 (1869) ; Stoddard v. Village of Sara

toga Springs, 127 N.Y. 261, 268, 27 N.E. 1030, 1031

(1891); McGraw v. Town of Marion, 98 Ky. 673, 680-

683, 34 S.W. 18 (1896); Schussler v. Board of Commis

sioners of Hennepin County, 67 Minn. 412, 70 N.W.

6, 7 (1897) ; City of Oklahoma City v. Hill Brothers,

6 Okl. 114, 137-139, 50 P. 242, 249 (1897) ; Bunker v.

20

City of Hudson,, 122 Wis. 43, 54, 99 N.W. 448, 452

(1904).11

We have not found a single ease, despite extensive

research, in which any American court in the Nine

teenth Century ‘ ‘ extended” to municipalities the im

munity for good faith acts enjoyed by officials against

individual liability.

While the court below did not attempt to explain its

extension of an immunity intended for public officials

in their individual capacity to municipalities, that ef

fort was made by a panel of the Tenth Circuit in Bertot

v. School District No. 1, Albany County, Wyoming,

Slip. Op. No. 76-1169 (November 15, 1978), vacated

pending rehearing en banc (1979).

11 In addition to the decisions cited in text, which expressly

articulated the Thayer principle, there were innumerable decisions

awarding damages against municipalities for violations expressly

found to have been committed in good faith. See e.g., Page v.

Hardin, 8 B. Monroe 648 (Ky. 1844) ; Holden v. Shrewsbury Sch.

Dist. No. 10, 38 Vt. 529, 532 (1866) ; Horton v. Inhabitants of

Ipswich, 66 Mass. 488, 489, 492 (Mass. 1853) ; Billings v. Wor

cester, 102 Mass. 329, 332-333 (1869) ; Hawks v. Inhabitants of

Charlemont, 107 Mass. 414, 417 (1871); Freeland v. City of Mus

catine, 9 Iowa 461, 464 (1859); Elliot v. Concord, 27 N.H. 204

(1853) ; State of Missouri ex rel Cullen v. Carr, 3 Mo. App. 6, 10

(1876) ; Weed v. Borough of Greenwich, 45 Conn. 170, 183 (1877);

Woodcock v. City of Calais, 66 Me. 234, 235-236 (1877) ; and see

generally, Note, Liability of Cities for the Negligence and Other

Misconduct of Their Officers and Agents, 30 Am. St. Rep. 376,

405-411 (1893). Still other cases recognized that the doctrine of

official immunity was inapplicable to suits against the municipality,

without inquiring further into the existence or non-existence of

good faith. Shaw v. Mayor of Macon, 19 6a. 468, 469 (1856) ;

County Commissioners of Anne Arundel County v. Duckett, 20

Md. 468, 481-482 (1863); Brown v. Rundlett, 15 N.H. 360, 370

(1844) ; Morrison v. McFarland, 51 Ind. 206, 210 (1875), citing

City of Crawfordsville v. Hays, 42 Ind. 200 (1873).

21

This Court in Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S., supra

at 240, and Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S., supra at 319-

320, had spelled out the reasons underlying the com

mon-law qualified immunity for public officials in their

individual capacity: (1) that individuals should not

be deterred from seeking public office by the risk of

personal financial exposure; (2) that it would be un

fair to subject those who do accept public service to

personal liability for good faith performance of their

office; and (3) that public officers should make deci

sions on public matters in the public interest and

should not be rendered timid by the need to weigh on

the scales a personal, non-public consideration, i.e.,

concern for their potential personal liability.

The Tenth Circuit panel in Bertot found the third

of these factors to justify a good faith immunity for

the government entity as well as for the individual

public officials (slip op. at 5-6):

The reasons for the application of the doctrine

of qualified immunity are as compelling when con

sidering the members individually as they are to

the evaluation of the members acting collectively.

. . . It is apparent that conscientious board mem

bers will be just as concerned that their decisions

or actions might create a liability for damages on

the board or the local entity as they would on

themselves. The restriction on the exercise of in

dependent judgment is the same. The individuals

are the same in whatever capacity, their good

faith is the same in each capacity whether it is

individual good faith, board good faith when con

sidered collectively, or official capacity good faith.

* * * *

Qualified immunity should thus be applied to the

board as such and to the individuals in their offi-

22

eial capacities. . . . The individuals with this quali

fied immunity conduct the official board business,

make the decisions, and carry on the official busi

ness. I f they have such immunity, there would

seem to be no reason why it should not be carried

into their collective actions as a board.

The rationale of the Bertot court is doubly wrong:

it misapprehends the role of a court in construing

§ 1983; and it misapprehends the rationale for the

public official immunity doctrine.

First, as we discussed above, at pp. 7-10, supra,

the question is not whether immunizing municipali

ties is a good idea, but whether there is any reason

to conclude that Congress intended to establish such

an immunity sub silentio in § 1983. In the absence of

an established body of law recognizing such an im

munity in 1871, there is no justification for attributing

such an intent to Congress. And as we have shown, the

law in 1871 was all to the contrary.

Second, the Bertot panel misunderstood the public

interest sought to be protected by the third of the rea

sons listed above underlying the public official immu

nity. The Court in Wood, supra, stated that reason as

follows (420 U.S. at 319-320) :

Denying any measure of immunity in these cir

cumstances “ would contribute not to principled

and fearless decision-making but to intimidation.”

. . . The imposition of monetary costs for mistakes

which were not unreasonable in the light of all the

circumstances would undoubtedly deter even the

most conscientious school decision-maker from ex

ercising his judgment independently, forcefully,

and in a manner best serving the long-term inter

est of the school and the students.

23

The Bertot panel assumed that public officials would

be deterred from acting “ forcefully” by entity liability

as well as by personal liability, and that therefore the

reason expressed in Wood would equally justify an

immunity for the governmental entity—i.e., public

officials must be able to act free from the concern that

their actions on behalf of the entity might violate the

law and thus result in monetary liability for the entity.

But the predicate of the statement in Wood, and of

the common law from which it drew, is that public

officials’ judgments on the public matters with which

they deal should not be clouded by personal considera

tions, i.e. the threat to their own pocketbooks. It hardly

follows that they should be equally insulated from con

sidering the impact of their decisions on the treasury

of the entity they were elected to serve. Consideration

of possible “ corporate” liability is appropriate in any

decision-making process, and indeed is essential to as

suring that governmental entities will comport them

selves in a manner consistent with their legal obliga

tions. Constitutional and statutory proscriptions on the

conduct of governmental entities are meant to be taken

into account and to affect the decisions of those

charged with running those entities. The consideration

of possible entity liability is a proper public concern

and should not be confused with the personal concern

raised by the possibility of individual liability.12

12 See Johnson v. State of California, 69 Cal.2d 782 (1968), in

which the court considered whether “ [t]he danger that public

employees will be insufficiently zealous in their official duties”

might serve as a basis for entity immunity under state laws. Noting

that official immunities were developed to protect public employees

‘ ‘ from the spectre of extensive personal tort liability” (id. at 790;

emphasis added), the court stated that it did not “ deem an em

ployee’s concern over the potential liability of his employer, the

24

Twice recently, this Court has recognized that the

considerations underlying the public official immunity

do not apply to governmental entities. In Hutto v. Fin

ney, 437 U.S. 678, 699 n. 32 (1978), the Court, in

approving an award of attorney’s fees from the state

treasury, criticized the dissenters who “ would appar

ently leave the officers to pay the award,” because the

latter result would:

. . . def[y] this Court’s insistence in a related con

text that imposing personal liability in the absence

of bad faith may cause state officers to “ exercise

their discretion with undue timidity.” Wood v.

Strickland, 420 U.S. 308, 321.

Similarly, in Lake County Estates v. Tahoe Planning

Agcy., 440 U.S. 391, 405 n. 29 (1979), the Court, while

holding individual regional legislators to be immune,

stated that “ [i ]f the respondents have enacted uncon

stitutional legislation, there is no reason why relief

against [the entity] itself should not adequately vin

dicate petitioners’ interests.”

B. Extrapolating A Qualified Immunity From The Insulation

Which Municipalities Enjoyed From Certain Tort Actions

At Common Law

In his concurring opinion in Monell, 436 U.S. at

713-714, Mr. Justice Powell noted that one of the ques-

tions remaining “ for another day” was “ whether the

protection available at common law for municipal cor-

governmental unit, a justification for an expansive definition of . . .

immune acts.” Id. at 792. The court ‘ ‘ consider[ed] it unlikely that

the possibility of governmental liability will be a serious deterrent

to the fearless exercise of judgment by the employee, ’ ’ but believed

that if such deterrence did occur, it might well be ‘ ‘ wholesome.”

Id. at 792.

25

porations, see post, at 720-721, support[s] a qualified

municipal immunity in the context of the § 1983 dam

ages action.” The reference was to a passage in Mr.

Justice Rehnquist’s dissenting opinion noting that “ no

state court had ever held that municipal corporations

were always liable in tort in precisely the same manner

as other persons,” id. at 720-721. The Second Circuit

has ruled that this consideration warrants extending

to municipalities a qualified good faith immunity from

damages for injuries caused by their constitutional

violations. Sola v. County of Suffolk, 604 F.2d 207, 211

(2nd Cir. 1979).

There were, indeed, two common law doctrines which

insulated municipalities from certain types of tort

actions altogether, regardless of the relief sought, in

junctive or damages. We discuss each of those doc

trines now, and show that neither could have formed

the predicate for an unexpressed congressional intent

to qualify the damage liability of municipalities in

§ 1983 actions.

1. S overeig n Im m un ity (the G ovem m en ta l/P rop rieta ry

Distinction).

At common law, the doctrine of sovereign immunity

insulated state governments from tort actions. When

the state delegated certain of its functions to a muni

cipality, the municipality was deemed an “ arm of the

state.” “ In chartering a municipal corporation, the

state, in fact, charters a portion of itself . . . A munici

pal organization is only a contrivance to aid the state

to administer the laws . . . ” Shearman & Redfield,

supra, at p. 143. With respect to those “ governmental”

functions the municipality enjoyed the state’s sovereign

immunity from suit:

26

So far as [municipal corporations] exercise

powers conferred on them for purposes essentially

public—purposes pertaining to the administration

of general laws made to enforce the general policy

of the state—they should be deemed agencies of

the state, and not subject to be sued for any act or

omission occurring while in the exercise of such

power, unless by statute the action be given. In

reference to such matters they should stand as does

sovereignty, whose agents they are, subject to be

sued only when the State by statute declares they

may be.

Beach, Commentaries on the Law of Public Corpora

tions, 266 (1893), quoting City of Galveston v. Posnain-

sky, 62 Tex. 118 (1884).13

Certain of a municipality’s functions, however, were

deemed not to have been delegated by the state, but

rather to have been voluntarily adopted by the citizens

of the municipality. As to these “ proprietary” func

tions, municipalities were treated the same as private

corporations: 14

[W ]ith respect to local or municipal powers

proper (as distinguished from those conferred

upon the municipality as a mere agent of the state)

13 A ccord : Cooley, Treatise on the Constitutional Limitations

240 (1868). The doctrine of sovereign immunity at common law

differed in scope, purpose and effect from the immunity extended

by the Eleventh Amendment. Thus, while the common-law doctrine

applied to some functions of municipalities, “ [t] he bar of the Elev

enth Amendment to suit in federal courts . . . does not extend to

counties and similar municipal corporations.” Ml. Healthy City

Board of Ed. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274, 280 (1977). See also Edelman

v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 667 n. 12 (1974) ; Moor v. County of

Alameda, 411 U.S. 693 (1973); Lincoln County v. Luning, 133

U.S. 529 (1890).

14 Except in South Carolina, see pp. 28-29 n. 17, infra.

27

the inhabitants are to be regarded as having been

clothed with them at their request and for their

peculiar and special advantage and . . . as to such

powers and the duties springing out of them, the

corporation has a private character, and is liable,

on the same principles and to the same extent as

a private corporation.

Dillon, Treatise on the Law of Municipal Corporations

33 (1st ed., 1872).15 *

In reality, by 1871 municipal corporations were far

more amenable to suits in tort than the governmental/

proprietary distinction would suggest. For sovereign

immunity was lost if “ by statute the action be given.”

Beach, supra, at 266. During the early and mid-Nine-

teenth Century, the courts found that as to many “ gov

ernmental” functions the states had by statute with

drawn the immunity. The process by which this was

accomplished is described in Shearman & Redfield,

supra, pp. 145-153, and in Note, Liability of Cities for

the Negligence and Other Misconduct of Their Officers

15 Accord: Cooley, supra, at p. 248; Beach, supra, at 770. This

dichotomy resulted in cities being more generally amenable to tort

actions at common law than counties and school districts, for the

latter were considered to be exercising delegated “ state” powers

in most if not all of their activities:

Counties, townships, school districts, and road districts do not

usually possess corporate powers under special charters; but

they exist under general laws of the State, which apportion

the territory of the State into political divisions for conveni

ence of government, and require of the people residing within

those divisions the performance of certain public duties as a

part of the machinery of the State. . . . Whether they shall

assume those duties or exercise those powers, the political

divisions are not allowed the privilege of choice; the legisla

ture assumes this division of the State to be essential in repub

lican government. . . .

Cooley, supra, at 240. A ccord : Beach, supra, at 267.

and Agents, 30 Am. St. Rep. 376, 380-387 (1893).

While a minority of the state courts required explicit

statutory conferral of a cause of action to lift sov

ereignty, 30 Am. St. Rep. at 381—rulings which often

were followed by the enactment of such explicit stat

utes, ibid—“ a decisive majority of the courts in this

country, both state and national” ruled that the imposi

tion of a duty upon a municipality by charter or stat

ute 11 implies that redress should be accorded in the

courts to anyone injured by its non-performance or

mis-performance,” id. at 385 (emphasis added). By

whichever route was followed in a particular state,

there developed throughout the nation an entire body

of statutory tort law: causes of action which could not

have been brought at common law were brought pur

suant to statute. See, e.g., City of Providence v. Clapp,

17 How. (58 U.S.), 161, 167-169 (1855); Weightman

v. Washington, 1 Black (66 U.S.) 39, 50-52 (1862);

Nebraska City v. Campbell, 2 Black (67 U.S.) 590, 592

(1862); Chicago v. Robbins, 2 Black (67 U.S.) 418,

422-425 (1863); Barnes v. District of Columbia, 91

U.S. 540, 544-552 (1876).16

Municipalities thus were broadly amenable to tort

actions as of 1871: for their “ proprietary” actions they

were suable at common law the same as a private cor

poration, and for their “ governmental” actions they

were suable to the extent—and it was a considerable

extent—that statutory causes of action had been created

as described above.17 And in both contexts—-the common

10 State court cases to the same effect are collected in Note, supra,

30 Am. St. Rep. at 380-387.

17 In his dissenting opinion in Monell, 436 U.S. at 721, Mr.

Justice Rehnquist cited Irvine v. Town of Greenwood, 89 S.C. 511

29

law action for “ proprietary” torts, and the statutory

action for ‘ ‘ governmental” torts—municipalities were

found liable in damages in a multitude of cases; 18 * our

research did not disclose a single case where a munici

pality was afforded any immunity, qualified or other

wise, from paying damages for injuries resulting from

an actionable tort.10

The sovereign immunity enjoyed by municipalities

at common law affords no basis for imputing to Con

gress an unstated intention to qualify the amenability

(1911), as reflecting a view that municipalities enjoyed “ absolute”

tort immunity. In Irvine, the South Carolina Supreme Court

rejected the “ governmental/proprietary ” distinction, and held that

all functions of municipalities were “ governmental.” The Irvine

court acknowledged that its ruling conflicted with decisions of the

United States Supreme Court, decisions in other states, and the

views expressed in the treatises, and it cited no decision from any

other state supporting its position. The effect of its decision, as the

court recognized, id. at 514, 518, was to render municipalities

suable only for statutory torts, i.e., in causes of action which the

General Assembly of South Carolina had authorized by statute.

In Sala, 604 F.2d, supra at 211, the Second Circuit, citing Mr.

Justice Rehnquist’s dissent, read a good faith immunity into § 1983,

reasoning that as § 1983 was “ enacted by a Congress accustomed

to nearly absolute municipal immunity” its statute should not “ be

read to implement a doctrine of liability without fault.” Even if

this were not a non sequitur, its premise (that Congress was “ ac

customed to nearly absolute municipal immunity” ) overlooked both

the universal acceptance (outside of South Carolina) of the pro

prietary functions doctrine and the statutory developments ren

dering municipalities suable for “ governmental” acts.

;s See sources cited at pp. 19-20, 27-28.

19 Although not a damage immunity, there was a rule of damages

applicable with respect to at least some municipal torts that, in

order to recover, the “ plaintiff [must have] sustained some peculiar

damage beyond the rest of the K ing’s subjects” by reason of the

tort. Weig'htman v. Washington, 1 Black (66 U.S.) 39, 53 (1862),

citing Mayor of Lyme v. Henley, 3 B. & Ad. 77 (1832).

30

of municipalities to damage awards under § 1983. The

doctrine of sovereign immunity was not a damage im

munity. Its effect, where it applied, was to insulate

the municipality from suit altogether, and thus to

preclude the entry of any kind of relief (injunctive

as well as monetary) against the municipality. The doc

trine’s existence did not reflect a prudential judgment

about the desirability or undesirability of holding mu

nicipalities monetarily accountable for their torts, but,

rather, reflected a truth about the nature of power: as

the sovereign made the law, it could be sued only if and

to the extent it chose to subject itself to the law it

made. Beers v. Arkansas, 20 How. (61 U.S.) 527, 529

(1858) ; Kawananakoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349, 353

(1907). The law of torts was state law; the state was

the sovereign which made that law; and except as the

state elected to subject itself (and its “ arms,” the mu

nicipalities) to obedience to that law, and assume ac

countability in its courts for failure to obey, no action

would lie.

Given the nature of that immunity, it was by defini

tion abrogated by enactment of a statute by the state

or, where federal power exists, the federal government,

subjecting a municipality to liability. The abolition of

sovereign immunity through the statutory creation of

causes of action was widespread by 1871, and its effect

was that municipalities were made subject to damage

liability without immunity.20 With respect to violations

of the federal Constitution and federal statutes, Con

gress was the “ sovereign” ; the states had no control

over the decision of Congress whether their subordi

20 See pp. 27-29, supra.

31

nate governmental bodies could be sued.21 When Con

gress decided to include municipalities among the

“ persons” against whom a § 1983 cause of action could

be brought, and thus to make municipalities amenable

in damages for violating those negative duties imposed

by the Fourteenth Amendment, Monell, supra, 436

U.S. at 679-680, it rejected en toto the sole foundation

upon which the common law immunity had rested, i.e.

the unavailability of suit. It cannot be presumed that

the 1871 Congress intended this imposition of statutory

liability to carry with it a municipal immunity from

damages when in no other statutory action against mu

nicipalities did such an immunity exist.

There is, accordingly, nothing about the common law

doctrine of sovereign immunity which justifies imput

ing to Congress an unstated intention to create a

“ qualified” immunity for local governmental bodies in

§ 1983 suits. To impute to Congress such an intention

would require assuming that Congress intended, with

out expressing its intention in the statute or the de

bates, to create an immunity entirely unknown to the

law. The state of the law in 1871 was that entities either

were suable or were not, and if suable they had no im

munity. Congress made them suable under § 1983, and

there is no conceivable basis for imputing to Congress

an intention that they should enjoy a qualified im

munity.

21 And the authority which Congress was exercising, that be

stowed by the Fourteenth Amendment, was federal authority, not

state authority. The laws enacted by Congress during the post-

Civil War period were “ grounded on the expansion of Congress’

powers— with the corresponding diminution of state sovereignty—

found to be intended by the Framers and made part of the Consti

tution upon the states’ ratification of [the 13th, 14th and 15th]

Amendments.” Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445, 455-456 (1976).

32

2. The Insulation of "D iscretion a ry" Functions From

N eg lig en ce Suits.

There was also at common law a doctrine protecting

municipalities from tort suits challenging “ discretion

ary” decisions. I f the law of negligence had been made

applicable to every decision of a municipality, then the

legislative judgments of the elected officials could have

been subjected to judicial review on a claim that they

were not “ reasonable” . The effect would have been to

transfer the ultimate legislative power to judges and

juries. To protect against this, the courts fashioned