Lee v. Macon County Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

December 5, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lee v. Macon County Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1973. 452972ec-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/47ecbfe2-b24c-43a3-b9a8-081439318468/lee-v-macon-county-board-of-education-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

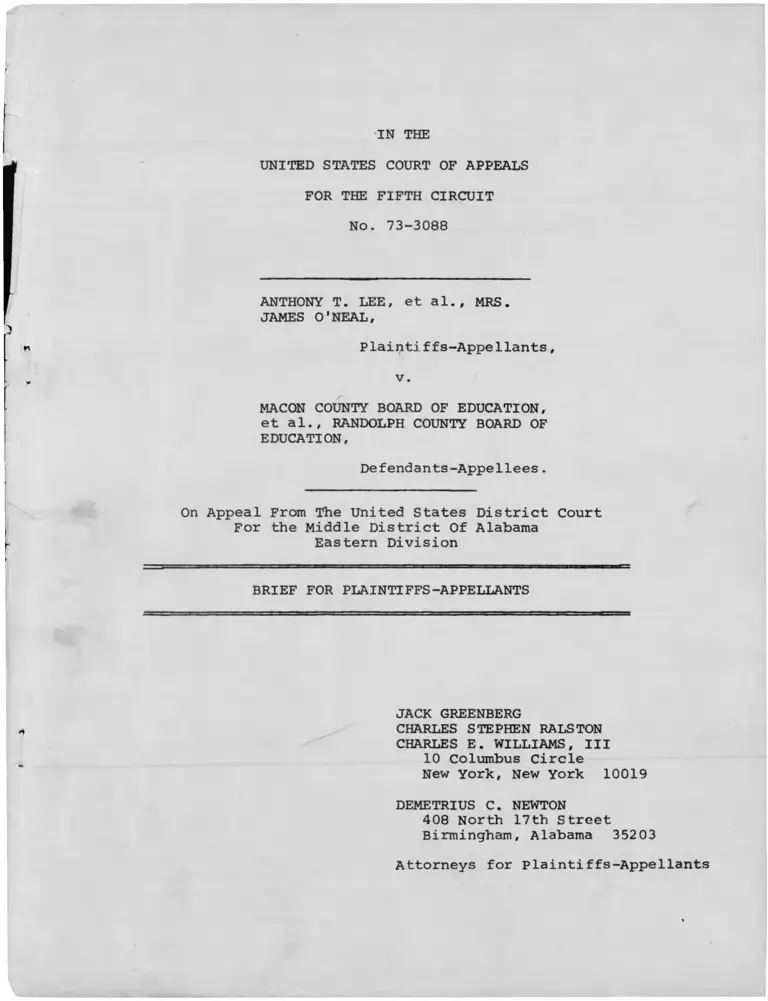

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-3088

ANTHONY T. LEE, et al., MRS.

JAMES O'NEAL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

MACON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al., RANDOLPH COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For the Middle District Of Alabama

Eastern Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

CHARLES E. WILLIAMS, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

■J

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-3088

ANTHONY T. LEE, et al., MRS.

JAMES O'NEAL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

MACON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al., RANDOLPH COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For the Middle District of Alabama

Eastern Division

CERTIFICATE

- ir The undersigned counsel of record for plaintiffs-appellants,

Mrs. James O'Neal, et al., certifies that the following listed

parties have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that judges of this Court

may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to

Local Rule 13(a).

1. Mrs. Inez Knight, Lillie Mae Knight and Rose Ella

Knight as plaintiffs-appellants,

and

as

f̂̂ LQ i t L be * -< * £ } '* Q jL lk .

2 . The Randolph County Board of Educatioo)and its members

defendants-appellees.

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

2

INDEX

Pa^e

Statement of Issue Presented for R e v i e w ........... 111

Statement of the C a s e ............................... 1

Statement of Facts ................................ 4

ARGUMENT:

Introduction..................... 12

I. The Procedure by Which the Decision Was

Made to Permanently Expel Lillie Mae

Knight and Rose Ella Knight Did Not

Comply With the Requirements of the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment..................... 14

C o n c l u s i o n ..................... 21

1

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Black Students v. Williams, 335 F. Supp. 820 aff'd

470 F .2d 957 (5th Cir. 1972) ....................... 14

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education,

294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961) ....................... 13, 14

Gagnon v. Scarpelli, ___ U.S. ___ , 41 U.S.L.W.

4647 (May 14, 1973) ................................ 17

Goldberg v. Kelley, 397 U.S. 2 54 (1970) ............. 17

Green v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 (1959) ............... 15

Griffin v. School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) ................................ 14

Joint Anti-Fascist Refuge Committee v. McGrath,

341 U.S. 123 (1951) ................................ 15

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., C.A. No. 847-E,

M .D . Ala..... .................... ......... ....... . . 1

Mills v. Board of Education, 348 F. Supp. 866

(D.D.C. 1972) ....................................... 14, 15

Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (1972) ............ 17

Paine v. Board of Regents of the University

of Texas, 355 F. Supp. 199 (W.D. Tex. 1972)

aff’d , 474 F .2d 1397 (5th Cir. 1973) .............. 18

San Antonio Independent School Dist. v. Rodriquez,

___ U.S. ____ , 41 U.S.L.W. 4407 (March 21, 1973) ... 14

Williams v. Dade County School Board, 441 F.2d ..... 14

299 (5th Cir. 1971)

li

STATEMENT OF ISSUE PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether the district court erred in refusing to order

the defendant school officials to return certain black students

to school and in upholding their permanent expulsion from

public education?

iii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-3088

ANTHONY T. LEE, et al., MRS.

JAMES O'NEAL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

MACON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al., RANDOLPH COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For the Middle District Of Alabama

Eastern Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This appeal brings to this Court for review the dismissal

of a Motion for Emergency Relief filed on February 7, 1973, by

black high school students from Randolph County, Alabama in the

statewide school desegregation case, Lee v. Macon County Bd. of

Educ., C.A. No. 847-E, M.D. Ala. The motion prayed that three

black students, who were suspended or permanently expelled,

without being afforded hearings, be reinstated in Randolph County

High School and that defendant Board of Education be required

to establish and enforce a program by which the participation

of black students in extra-curricular activities of the high

school would be increased to reflect the percentage of blacks

in the student body (A. 4).

Subsequent to the filing of the Motion for Emergency Relief,

counsel for plaintiffs and counsel for defendants, with the

advice and consent of the district court, agreed to have a hearing

of the issues raised by the motion before defendant Randolph

County Board of Education (A. 112). Defendant Board of Education,

after a hearing held on March 8, 1973, confirmed the suspension

of one of the three black students and the permanent expulsion

of the other two (A. Ill). In addition, defendant Board of Ed

ucation. failed to establish a program for increased participation

by black students in extra-curricular activities.

By a stipulation dated July 9, 1973, the parties agreed

that the papers previously filed plus the transcript of the

March 8, 1973 meeting, would be the only evidence submitted to

the district court and that a final judgment could be entered

without any further notice to the parties. The stipulation was

approved by the district court on July 17, 1973 (A. 111-112).

2

On July 20, 1973, the district court, Varner, J., issued

its order. The court held that the suspended student and the

two students who had been permanently expelled had not been

denied due process of the law. In addition, the court found

that the evidence submitted established that the two students

permanently expelled had been guilty of conduct which included

fighting, being indignant, yelling at an instructor, failing

to cooperate with school officials, being disorderly, cursing

and striking an instructor. In addition, based on these findings.

Judge Varner held that although permanent expulsion was a "harsh"

penalty, under the circumstances it was not unreasonable.

Finally, the court found that there was insufficient evidence

to prove plaintiffs allegations of racial discrimination in

extra-curricular activities at Randolph County High School

(A. 113).

The district court ordered that the Motion for Emergency

0

Relief was dismissed with prejudice and that costs incurred

were taxed against plaintiffs (A. 118).

The Notice of Appeal, Bond for Costs on Appeal and

Designation of Record on Appeal were filed in the district court

on August 14, 1973 (A. 119-122).

As of the date hereof the student suspended has returned

to school while the two students permanently expelled are still

not receiving an education. This appeal is limited to the two

students who have been permanently expelled from Randolph County

3

High School.

Statement of Facts

On February 2, 1973, Mrs. Inez Knight, the mother of Lillie

Mae Knight, a seventeen-year-old eleventh grader at Randolph

County High School, and Rose Ella Knight, a fourteen-year-old

ninth grader at Randolph County High School,was informed that

her two children wanted her to come to school (A. 72-73).

Upon Mrs. Knight's arrival at the school Mr. Hulond Humphries,

principal of Randolph County High School, brought her two

daughters to her and informed Mrs. Knight that she should take

them home because they refused to cooperate with him (A. 73).

Mr. Humphries did not inform Mrs. Knight or her daughters of

what specific charges, if any, were being brought against Lillie

Mae and Rose Ella, or of what procedures would be followed in the

future to determine whether they would be allowed to return to

school (A. 60).

Subsequent to sending Lillie Mae and Rose Ella Knight home,

Mr. Humphries sent two letters dated February 2, 1973, to the

Randolph County Board of Education requesting that Lillie Mae

Knight and Rose Ella Knight be permanently expelled from Randolph

County High School (A. 43-46). However, neither Mrs. Knight nor

her children were informed of these letters.

4

In the letter referring to Lillie Mae Knight, Mr. Humphries

alleged the following: (1) That she had been involved in a

fight on January 11, 1973; (2) that he had imposed as punishment

a requirement that she write a six-page report entitled "Ways to

Solve Problems Without Fighting," which was due on January 16, 1973

and that he had had a conference with Mrs. Knight at the time the

punishment was imposed (A. 43); (3) that Lillie Mae Knight did not

turn in the report on the date set and when he discussed this with

her on January 22, 1973, she became "very indignant." Therefore,

Mr. Humphries sent her home for three days or until she wrote the

report (A. 43) and Lillie Mae Knight returned to school on January

26, 1973 (A. 43); (4) that on February 2, 1973, Lillie Mae Knight

advised her sister that she did not have to obey an order from

a teacher and when the teacher involved attempted to discuss this

with Lillie Mae she yelled at him and told him not to touch her

(A. 42-43). The letter concluded with a statement that because

Mrs. Knight had failed to help in solving the problem and Lillie

Mae had refused to cooperate he was asking that she be dismissed

from school (A. 44).

The letter referring to Rose Ella Knight alleged the following

(1) That on November 28, 1972, Rose Ella received five licks for

refusing to allow a male teacher paddle her (A. 45); (2) that on

December 1, 1972, she received five licks for misconduct in the

school library (A. 45); (3) that on January 11, 1973, she received

5

three licks, was ordered to apologize at a school assembly

and placed on probation for the remainder of the school year

for allegedly fighting, cursing and hitting a teacher (A. 45);

(4) that rather than apologizing as ordered, Rose Ella Knight

protested her innocence and Mr. Humphries, ignoring her protest,

threatened to send her home unless she apologized (A. 45);

(5) that on January 25, 1973, Rose Ella Knight got into a yelling

match with another student (A. 45); (6) that on February 1, 1973,

Rose Ella was brought to the office by a teacher for refusing to

obey an order and refusing to take punishment. She turned in her

books but returned to school on February 2, 1973, and at that

time Mr. Humphries sent her home with her mother (A. 44-45).

The letter concluded with a statement that Mr. Humphries had

three unsatisfactory conferences with Mrs. Knight and that he

was asking for the dismissal of Rose Ella because she had been

uncooperative (A. 46) .

Mrs. Knight, having received no information concerning when

her two children would be allowed to return to school, filed

the Motion for Emergency Relief on February 8, 1973. The

motion alleged denial of due process of law and prayed that

the court reinstate her two children in Randolph County High

School (A. 4). Subsequent to the filing of the motion counsel

for plaintiffs and counsel for defendants, with the advice

and consent of the district court, agreed to have a hearing

before defendant Randolph County Board of Education. This

hearing was held on March 8, 1973 (A. Ill).

6

At the hearing, Mr. R. D. Simpson, Superintendent of

the Randolph County High School, read into the record the two

letters that were written by the principal of Randolph County

High School (A. 42-46). On cross-examination Mr. Simpson admitted

that other than the letters from the principal he had no personal

knowledge of any disciplinary problems involving the two girls

(A. 50). Further, Mr. Simpson stated that once a student is

permanently expelled from the Randolph County Public School

System no arrangements are made for the student to receive any

form of education (A. 49). Therefore, if the Board of Education

granted the principal's request that Lillie Mae and Rose Ella

Knight be permanently expelled from school their public education

would come to an end.

The only evidence presented against Lillie Mae Knight and

Rose Ella Knight at the hearing were the letters read into the

record by Mr. Simpson, who admitted he had no knowledge of the

events described therein, and the testimony of Mr. Huland

Humphries, the principal of Randolph County High School who

wrote the letters. Mr. Humphries, however, admitted at the

beginning of his testimony that he had no personal knowledge

of the incidents of misconduct (A. 51). He did state that his

letters were based on investigations he conducted, however, Mr.

Humphries failed to describe these investigations or offer any

statements by teachers or other proof to support his conclusions

as to what in fact occurred (a . 51). Therefore, the only

7

evidence presented against Lillie Mae Knight and Rose Ella

Knight at the hearing to determine whether the harsh penalty

of permanent expulsion from public school would be imposed was

the unsupported hearsay testimony of the principal of Randolph

County High School.

Mr. Humphries stated that he decided to request the permanent

expulsion of Lillie Mae Knight and Rose Ella Knight because the

girls refused to take punishment claiming that they were

innocent of the charges against them. He further stated that

he interpreted this refusal to accept punishment as a failure

to cooperate (A. 55-57).

After the hearsay testimony of Mr. Humphries, Lillie Mae

Knight, Rose Ella Knight and Mrs. Inez Knight, unlike their

accusers, testified in their own behalf and subjected themselves

to cross-examination by defendants' attorney (A. 57-77).

Lillie Mae Knight testified that the fighting incident

of January 11, 1973, occurred when she was attempting to

defend herself from an attack by another girl (A. 62); that

she had prepared the report assigned to her as punishement

but it was found to be unacceptable (A. 62-63); and that she had

intended to rewrite it but was dismissed from school before she had

the opportunity (A. 63). In addition, Lillie Mae testified that on

8

the day she was dismissed from school she was not advising

her younger sister to disobey the teachers1 orders, but was

merely informing Rose Ella that their mother was coming to

school to attempt to solve the problem and Rose Ella should

wait for her arrival (A. 58-59). Finally, Lillie Mae Knight

testified that she walked away from the teacher because she only

had a limited time to get to her next class, not as was alleged,

to defy the teacher's authority (A. 59-60).

Rose Ella Knight testified about the circumstances

sourrounding the incidents of conduct alleged in Mr.

Humphries' letter (A. 63-69). She stated that the striking

of the teacher was accidental and when she apologized the teacher

stated that he knew she didn't mean it (A. 67-68). In addition,

Rose Ella testified that she had written an original and four

modifications of the paper that had been assigned as punishment

for fighting, but each time Mr. Humphries rejected it, even

after one of the teachers had found it to be satisfactory (A. 68).

Generally Rose Ella Knight's testimony was that she did not

believe that her conduct was of a nature to justify the punishment

she had received (A. 63-69).

Mrs. Inez Knight testified that it was her opinion that prior

to the dismissal of her two daughters, Mr. Humphries had been

harassing them because two - members of their family had been

charged with murder (A. 71). She stated that she tried to explain

to the principal that her younger child was having great

9

difficult coping with this situation and asked for some special

consideration in dealing with her, but Mr. Humphries would not

listen (A. 71-72). She also indicated that she had told Rose

Ella not to take anymore paddlings because she believed that it

*

was improper to have her fourteen—year-old daughter paddled

by a male teacher or administrator (A. 72-73) .

The members of defendant Randolph County Board of Education

did not file an opinion for the record, but they did confirm

the permanent expulsion of Lillie Mae Knight and Rose Ella

Knight (A. Ill) .

By a stipulation dated July 9, 1973, the parties agreed

that absent a request from the court, the papers previously

filed plus the transcript of the March 8, 1973 hearing would be

the only evidence submitted to the district court and that a

final judgment could be entered without any further notice to

the parties. The stipulation was approved by the district court

on July 17, 1973 (A. 111-112).

The district court, Varner, J., issued its order on

July 20, 1973. Even though all of the evidence presented against

Lille Mae and Rose Ella Knight was hearsay, the girls

never had an opportunity to confront and cross-examine their

accusers and no opinion was filed by the Board of Education;

the court held that they had not been denied due process of law.

In addition the court found that the hearsay evidence submitted

10

established that Lillie Mae Knight and Rose Ella Knight

had been guilty of conduct which included fighting, being

indignant, yelling at an instructor, failing to cooperate

with school officials, being disorderly, cursing and

striking an instructor. The court held, based on these

findings, that although permanent expulsion was a "harsh"

penalty, it was not unreasonable (A. 113).

The district court ordered that the Motion for Emergency

Relief was dismissed with prejudice and that costs incurred

be taxed against plaintiffs.

The Notice of Appeal, Bond for Costs on Appeal and

Designation of Record on Appeal were filed in the district

court on August 14, 1973 (A. 118).

As of the date hereof Lillie Mae Knight and Rose Ella

Knight are still not receiving an education.

11

ARGUMENT

Introduction

The central issue in this appeal is the constitutionality

of the permanent expulsion of two black students from the

schools of Randolph County Alabama. As shown by the statement

of facts, the effect of that expulsion has been to permanently

deny them the right to all public education.

Appellants do not argue that school officials cannot

impose proper discipline on students for misconduct or

that they cannot otherwise control disruptive activity in

a school so as to be able to carry on its program of education.

We do urge, however, that it is settled law that before a

school system can expose students to the severe punishment

of permanent expulsion from school they must conduct hearings

which conform to the "rudiments of an adversarial system"

which requires, as a minimum, that there be some opportunity

for the student to confront his or her accusers and that a

decision as momentous as the determination that a student

will no longer be allowed to receive a free public education

cannot be based solely on hearsay testimony. If this basic

(

12

requirement of due process'is not met the effect is

that a proceeding which should be a hearing in the nature

of an adversarial proceeding is transformed into a rubber

stamp for a predetermined verdict of guilt with the severe

penalty of permanent expulsion as punishment.

In addition, appellants urge that there are constitutional

limitations on the kind and severity of punishment that

can be meted out by school officials. As this Court held

in Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education. 294 F.2d

150, 157 (5th Cir. 1961):

"Turning then to the nature of the . . . power

to expel . . ., it must be conceded . . . that

that power is not unlimited and cannot be

arbitrarily exercised. Admittedly, there must

be some reasonable and constitutional ground

for expulsion . . . "

Appellants urge that where there has been an absolute denial

of education the procedures followed at the hearing at which

that penalty is imposed must meet the highest standards of

13

fairness and the reasons for the imposition of that harsh penalty

are subject to strict scrutiny to determine whether they are

reasonable. Students who have been permanently expelled are

denied the right to an education that is available to all

other students. This total denial, unlike mere inequities in

the quality of education, violates equal protection unless it

serves a compelling state interest that cannot be fulfilled

by less drastic means. Cf. San Antonio Independent School

Dist. v. Rodriquez, ___ U.S. ___ , 41 U.S.L.W. 4407, 4418

(March 21, 1973); Griffin v. School Bd. of Prince Edward County.

377 U.S. 218 (1964); Mills v. Board of Education. 348 F. Supp.

866 (D.D.C. 1972).

I.

THE PROCEDURES BY WHICH THE DECISION WAS

MADE TO PERMANENTLY EXPEL LILLIE MAE KNIGHT

AND ROSE ELLA KNIGHT DID NOT COMPLY WITH

THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE

OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

It is well established that when the government takes

action that injures an individual, it must conform to basic

requirements of due process. This principle has been applied

in many instances, including the suspension or expulsion of

students in public schools. See Dixon v. Alabama State Board

of Education, 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961); Williams v. Dade

County School Board, 441 F.2d 299 (5th Cir. 1971); Black Students

14

v. Williams, 335 F. Supp. 820 aff'd 470 F.2d 957 (5th Cir. 1972).

See also, e.g., Green v. McElrov. 360 U.S. 474 (1959); Joint

Anti-Fascist Refuge Committee v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123 (1951).

While the specific requirements of due process may be flexibly

applied to school disciplinary procedures, certain basic require

ments must be satisfied.

Generally, the procedures must be such so as to produce an

informed decision not only as to whether the students committed

the offense charged, but also whether the offense justified

the particular discipline imposed. Appellants contend that the

procedures adopted by the school board below did not meet these

requirements.

The main deficiences in the proceedings were that the

school board relied solely on hearsay testimony and that the

burden was placed on the students to demonstrate why they should

be allowed to return to school rather than the burden being on

the school authorities to justify the imposition of the severe

penalty of permanent expulsion. C f . Mills v. Board of Education,

348 F. Supp. 966, 881 (D.D.C. 1972).

The principal presented the only testimony against Lillie

i

Mae Knight and Rose Ella Knight and he admitted that he had no

personal knowledge of the alleged incidents of misconduct. The prin

cipal stated that his conclusions were based on investigations, but nc

description of the investigation was given. The teachers who made the

- 15 -

charges were not present, did not testify, nor were they

available for cross-examination. Thus, although Lillie Mae

and Rose Ella Knight were represented by counsel, and their

counsel was allowed to cross-examine the principal, the right

of confrontation and cross-examination was merely illusory.

The total absence of opportunity to cross-examine the

students' accusers, and thereby clarify the circumstances

surrounding the alleged incidents of misconduct, made it

necessary for the girls to provide explanations for their

conduct, refute the charges made, and justify their return

to school. If they did not, the hearsay testimony of the

principal would have been accepted as true and their permanent

expulsion would have been automatic. Since the testimony of

the principal would have been accepted as true absent contra

diction by the students, the effect was that the burden of

proof was on Lillie Mae Knight and Rose Ella Knight to establish

that they should be readmitted to school rather than on the school

authorities to justify their contention that the two girls should

be permanently expelled, j

Further, the proceedings were deficient in that they did

not address themselves to the second issue before the school

board; that is, assuming the students did commit the acts they

were accused of was the harsh and irrevocable punishment of

barring fourteen and seventeen-year-old high school students

from receiving any future education reasonable and proper.

16

As was stated in the introduction hereto, in making the

determination of whether the punishment imposed was reasonable,

the fact that the school board was not imposing a one week,

one month or one year suspension from school but, instead,

was sanctioning the permanent denial of a public education

is of the utmost importance and requires that those who would

impose such a penalty meet the highest possible standard of

fairness and satisfy the most rigid procedural requirements

possible.

We urge that recent decisions of the Supreme Court that

establish procedural requirements in the area of probation and

parole revocation are directly applicable and should govern.

In Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (1972), the court explicitly

held that a parole revocation hearing had to address itself

not only to "any contended relevant facts" but also as to

"whether the facts as determined warrant revocation." 408 U.S.

at 488. Moreover, a person faced with revocation must be given

an opportunity to show why the violation did not warrant revo

cation. Ibid. Further, the parole board must not only make

findings of fact, but must specify the "reasons for revoking

parole." I<3. at 489. See also, Gagnon v. Scarpelli, ___ U.S.

___, 41 U.S.L.W. 4647 (May 14, 1973), imposing the same require

ments in probation revocation proceedings. Morrissey, of course,

relied heavily on Goldberg v. Kelley, 397 U.S. 254 (1970), which

applied similar requirements to determine whether to terminate

welfare benefits.

17

In view of the great importance of education in our society

it seems self-evident that a student faced with permanent

expulsion from public school and the consequent termination

• iof education at a level which is considered less than the

minimum for social and economic success is entitled to no less

1/than criminals facing re-incarceration.

The principal of Randolph High School stated both in his letters

requesting the permanent expulsion of Lillie Mae Knight and Rose

Ella Knight (A. 44, 46) and in his testimony at the hearing

(A. 52) that his decision to request that penalty was not based

solely on the alleged incidents of misconduct involving the two girls

but also on the fact that he failed to get cooperation from

them and their mother in solving what he viewed as a substantial

disciplinary problem. Therefore, the actions and statements

of Mrs. Knight and her two daughters that the principal

interpreted as being examples of lack of cooperation were

important factors in his decision to see the punishment

imposed.

Mrs. Knight explained to the members of the Board of

Education that the conduct that the principal interpreted as a

1/ Just as a person faced with being returned to prison or

with being deprived of the necessities of life, a student has

"an interest of extremely great value" that must be protected.

Paine v. Board of Regents of the University of Texas, 355 F.

Supp. 199 (W.D. Tex. 1972) aff'd, 474 F.2d 1397 (5th Cir. 1973)

IB

refusal to cooperate was in fact an attempt on her part to

explain to him the great strain that she and her two children

were under because of the murder charges against her brothers

and an attempt to work out a procedure for handling any future

disciplinary problems that might arise which would take the

problems her daughters were experiencing at home into consideration

(A. 70-73). This testimony clearly refutes the principal's

claim that Mrs. Knight and her children were uncooperative.

However, the Board of Education failed to discuss the issue of

whether in view of the facts presented at the hearing the

school authorities had established that the permanent expulsion

of Lillie Mae and Rose Ella Knight was a reasonable and proper

punishment.

Since the Board of Education did not file an opinion

setting forth how the decision supporting permanent expulsion

was arrived at it cannot be determined whether this issue was

ever considered off the record, however, even if it was, the

very failure to explain why a lesser sanction was not chosen

was in and of itself a denial of due process of law. Therefore,

whether the Board failed to consider the issue or just failed

to report the reasons for its decision, its actions amounted to

2/-

a denial of due process of law.

2/ The denial of due process of law makes it unnecessary

for this Court to reach the ultimate question of whether the

imposition of the penalty of permanent expulsion was unreasonable

in this case, however, if such a determination was necessary

it would be appellants' contention that it is clear on the record

that it was and the district court's holding to the contrary

was error.

19

Appellants are aware, of course, that in administrative

proceedings such as a school disciplinary hearing, due process

requirements cannot be imposed too rigidly. However, where,

as in the instant case, the harsh penalty of termination of a

student's education is involved, the highest possible standards

of fairness must be adhered to. Therefore, the total reliance

on hearsay, the shifting of the burden of proof from the school

authorities to the students and the failure to either consider

or properly report the consideration of the issue of whether

the penalty imposed was reasonable, both singularly and in

conjunction, amounted to a denial of due process of law and

the District Court's holding to the contrary was erroneous.

20

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the District

Court to the extent it affects Mr. Inez Knight and her

daughters Lillie Mae Knight and Rose Ella Knight should be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

CHARLES E» WILLIAMS, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appe Hants

21

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on the 5th day of October,

1973, copies of the Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants were

served upon counsel for appellees via United States mail,

air mail, postage prepaid, addressed as follows:

JohnS. Casey, Esq.

P. 0. Box 266

Heflin, Alabama 36264

* * frc*

Attorney for Plaintiffs-

Appe Hants