Correspondence from Counsel to Stone Re: Agenda

Correspondence

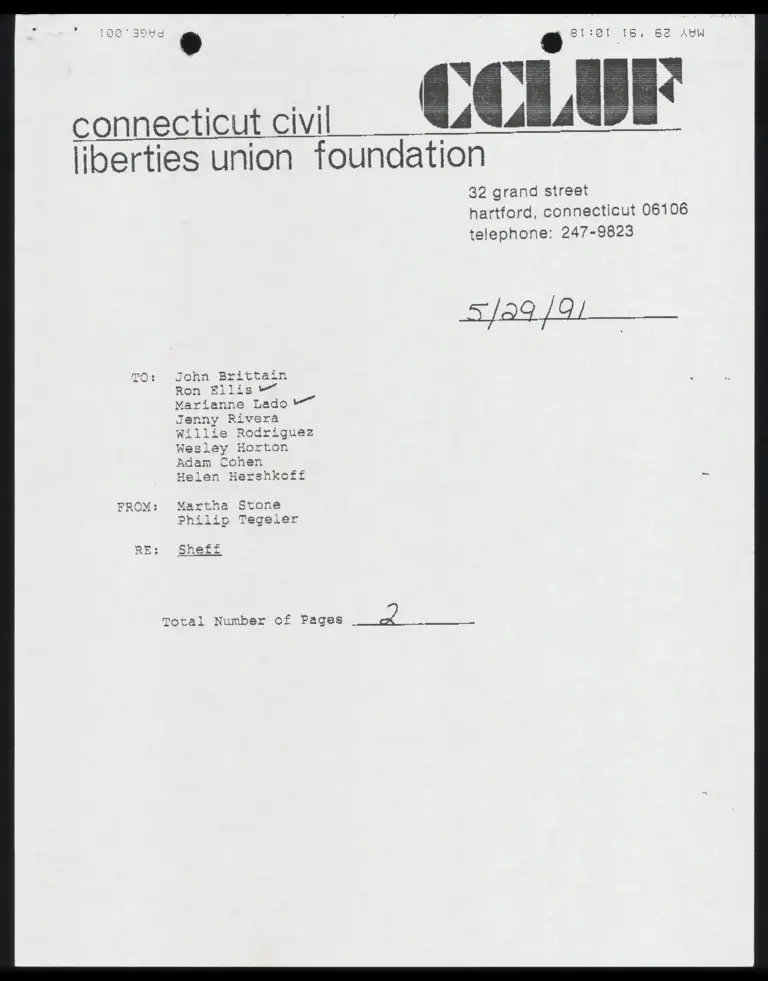

May 29, 1991

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Correspondence from Counsel to Stone Re: Agenda, 1991. e615d00c-a446-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/482cb7d6-ca95-402b-b7f2-5a8b4375fbea/correspondence-from-counsel-to-stone-re-agenda. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

[E358 IaH %

connecticut Civil

liberties union foundation

32 grand street

hartford, connecticut 06106

telephone: 247-9823

5/29/49)

TO: John Brittain

Ron Ellis ww”

Marianne Lado «

Jenny Rivera

Willie Rodriguez

Wesley Horton

Adam Cohen

Helen Hershkoff

FROM: Martha Stone

Philip Tegeler

Total Number ¢f Pages WY,

ZOD 30H %

connecticut civil |

liberties union foundation

32 grand street

hartford, connecticut 0681086

telephone; 247-9823

TO: Sheff Attorneys

FROM: Martha Stone

RE: Sheff Agenda

DATE: May 29, 1991

1. Interviews of Teachers, Principals

2. Interviews with Hartford Hoard of Education

3. New Disparities Expert, Educational Consultant

4, New York Meeting of Remedial Experts

5. Summary of Opticns Document for Community Outreach