Legal Defense Fund Asks Federal Court to Order Admission of Montgomery Negro to Alabama University Graduate School

Press Release

August 6, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 3. Legal Defense Fund Asks Federal Court to Order Admission of Montgomery Negro to Alabama University Graduate School, 1965. 64be1d35-b692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/483a25a5-515d-4f65-854f-1cb17082b749/legal-defense-fund-asks-federal-court-to-order-admission-of-montgomery-negro-to-alabama-university-graduate-school. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

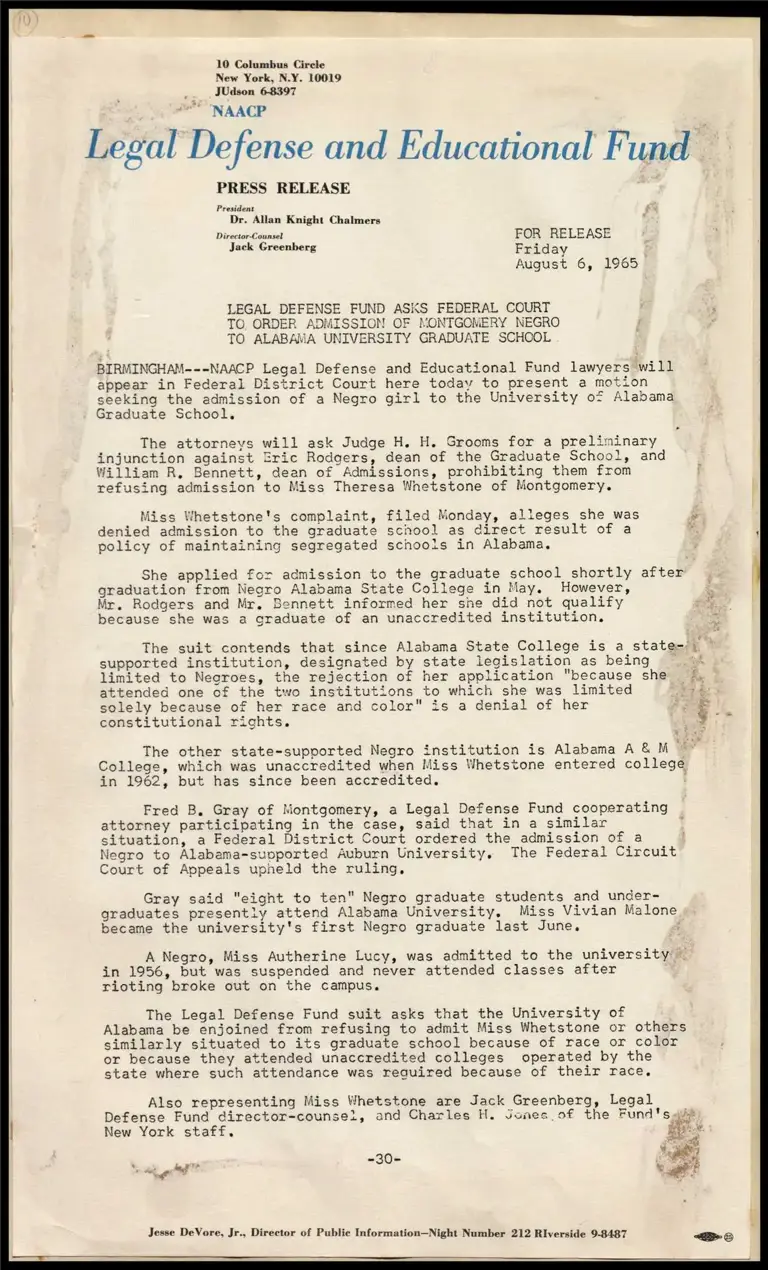

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

Presiden

Dr. Allan Knight Chalmers

Director-Counsel FOR RELEASE

Jack Greenberg Friday

August 6, 1965

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND ASKS FEDERAL COURT

TO. ORDER ADMISSION OF MONTGOMERY NEGRO

TO ALABAMA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL

BIRMINGHAM---NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund lawyers will

appear in Federal District Court here today to present a motion

seeking the admission of a Negro girl to the University of Alabama

Graduate School.

The attornevs will ask Judge H. H. Grooms for a preliminary

injunction against Eric Rodgers, dean of the Graduate School, and

William R, Bennett, dean of Admissions, prohibiting them from

refusing admission to Miss Theresa Whetstone of Montgomery.

Miss Whetstone's complaint, filed Monday, alleges she was FS

denied admission to the graduate school as direct result of a i

policy of maintaining segregated schools in Alabama.

She applied for admission to the graduate school shortly after

graduation from Negro Alabama State College in May. However,

Mr. Rodgers and Mr, Bennett informed her she did not qualify Se

because she was a graduate of an unaccredited institution. s

The suit contends that since Alabama State College is a staten’)

supported institution, designated by state legislation as being A

limited to Negroes, the rejection of her application "because she 4%,

attended one of the two institutions to which she was limited :4

solely because of her race and color" is a denial of her

constitutional rights.

The other state-supported Negro institution is Alabama A & M %

College, which was unaccredited when Miss Whetstone entered college

in 1962, but has since been accredited.

Fred B. Gray of Montgomery, a Legal Defense Fund cooperating

attorney participating in the case, said that in a similar

situation, a Federal District Court ordered the admission of a ;

Negro to Alabama-supported Auburn University. The Federal Circuit

Court of Appeals upheld the ruling,

Gray said "eight to ten" Negro graduate students and under-

graduates presently attend Alabama University, Miss Vivian Malone

became the university's first Negro graduate last June.

A Negro, Miss Autherine Lucy, was admitted to the university *

in 1956, but was suspended and never attended classes after

rioting broke out on the campus.

The Legal Defense Fund suit asks that the University of

Alabama be enjoined from refusing to admit Miss Whetstone or others

similarly situated to its graduate school because of race or color

or because they attended unaccredited colleges operated by the

state where such attendance was required because of their race.

Also representing Miss Whetstone are Jack Greenberg, Legal

Defense Fund director-counsel, and Charles H. Jones of the Fund's

New York staff.

&

seen? race ee

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 Riverside 9-8487