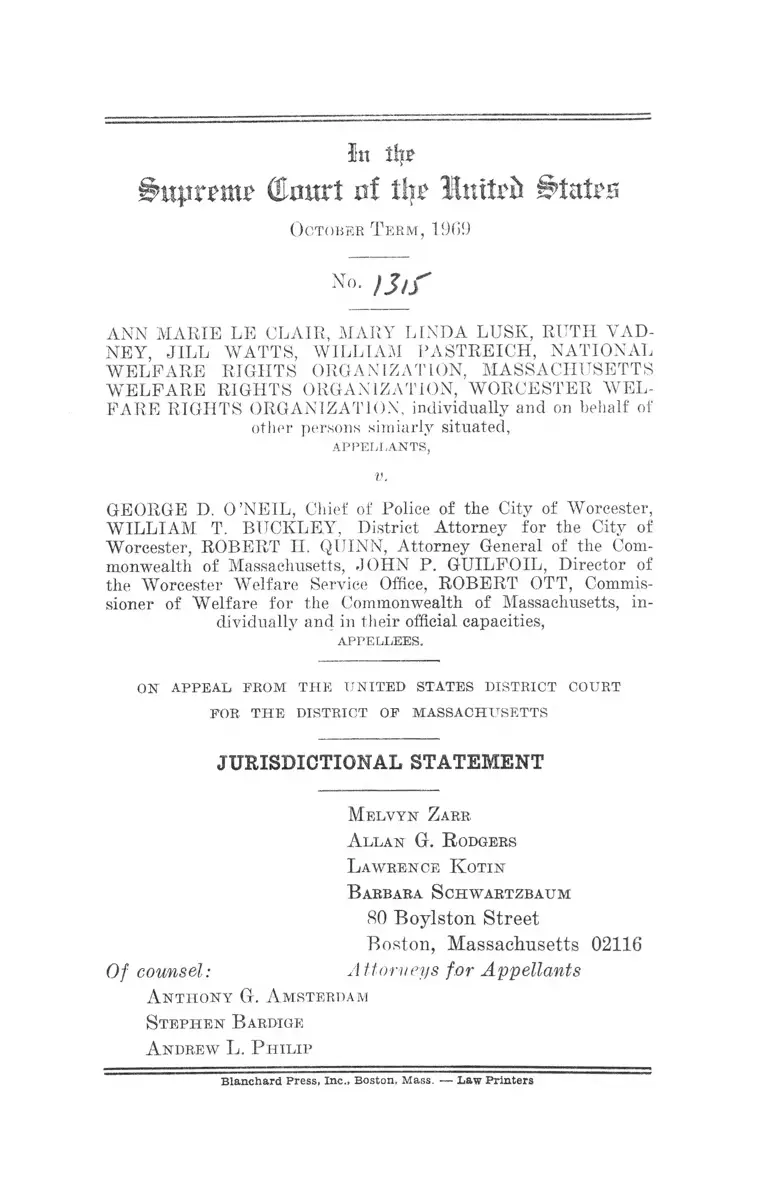

Le Clair v. O'Neil Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Le Clair v. O'Neil Jurisdictional Statement, 1969. 3ebe4fc2-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/486268c0-102a-40b2-8588-0ff022b8649f/le-clair-v-oneil-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

In the

0n;trrmr Court of tljr IHuitrii ^tatru

October T erm , 1909

no. )s,r

ANN MARIE LE CLAIR, MARY LINDA LUSK, RUTH VAD-

NEY, JILL WATTS, WILLIAM PASTREICH, NATIONAL

W ELFARE RIGHTS ORGANIZATION, MASSACHUSETTS

WELFARE RIGHTS ORGANIZATION, WORCESTER W EL

FARE RIGHTS ORGANIZATION, individually and on behalf of

other persons simiarly situated,

APPELLANTS,

V.

GEORGE D. O ’NEIL, Chief of Police of the City of Worcester,

WILLIAM T, BUCKLEY, District Attorney for the City of

Worcester, ROBERT H. QUINN, Attorney General of the Com

monwealth of Massachusetts, JOHN P. GUILFOIL, Director of

the Worcester Welfare Service Office, ROBERT OTT, Commis

sioner of Welfare for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, in

dividually and in their official capacities,

APPELLEES.

ON APPEAL. PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

M elvyn Z aer

A llan G. R odgers

L awrence K otin

B arbara S chwartzbaum

80 Boylston Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02116

Of counsel: A ttorueys for Appellants

A nthony G. A msterdam

Stephen B ardige

A ndrew L. P hilip

Blanchard Press, Inc., Boston, Mass. — Law Printers

INDEX

Opinion Below ...............................................................

Jurisdiction ..................................................................... ^

Statute Involved ..............................................................

Question Presented ........................................................ •’

Statement of the Case .................................................... •“

The Federal Question Presented is Substantial

The Decision Below Seriously Undermines the Power

and Responsibility of the Federal Courts to Protect

Citizens From the Repressive Effects of Vague and

Overbroad State Laws Trenching Upon First and

Fourteenth Amendment Rights ................................ 8

Conclusion .......................................................................

Appendix

Opinion of the United States District Court for the

District of Massachusetts ......................................... '"i

Judgment of the United States District Court for the

District of Massachusetts ........................................... 10a

T able of Cases

Page

Ashton v. Kentucky, 384 U.S. 195 (1966) .................. 10

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 (1964) ................... 13, 21

Baker v. Bindner, 274 F. Supp. 658 (W.D. Ky. 1967) 24

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131 (1966) .................... 23

Cameron v. Johnson, 390 U.S. 611 (1968) ............... 2,18

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1941) . . . . 9,11,16

Carmichael v. Allen, 267 F. Supp. 985 (N.D. Ga. 1966) 24

Commonwealth v. Oaks, 113 Mass. 8 (1873) ............. 8

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965) ............... 9,10,11

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) . . . 13,15, 23

11 Index

Edwards v. South Carolina-, 372 U.S. 229 (1963) . . . 9,

10, 11, 16

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961) .................. 17

Golden v. Zwichler, 394 U.S. 103 (1969) .................... 22

Gregory v. Chicago, 394 U.S. I l l (1969) .................... 13

Guyot v. Pierce, 372 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1967) ........... 24

Hurley v. Hinckley, 304 F. Supp. 704 (D. Mass. 1969),

aff’d sub nom. Doyle v. O’Brien,------U .S.-------, Jan

uary 12, 1970 --------------------------------------------- 6,16, 25

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589 (1967) . 19

Landry v. Daley, 280 F. Supp. 968 (N.D. 111. 1968) 8, 24

Maryland Casualty Co. v. Pacific Coal and Oil Co., 312

U.S. 270 (1941) .......................................................... 22

NAACP v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288 (1964) ................... 10

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) . . 12,16, 20, 21

National Student Association v. Hershey, 412 F.2d

1103 (D.C. Cir. 1969) ................................................. 20

Soglin v. Kauffman, 418 F.2d 163 (7th Cir. 1969) ....... 24

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949) 9,11

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940) ................. 13

Zwichler v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241 (1967) ....... 2, 21, 23, 24

Zwichler v. Boll, 391 U.S. 353 (1968) ........................ 12

Statutes

P age

28 U.S.C. §1253 ............................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) ......................................................... 2,6

28 U.S.C. §2201 ............................................................... 6

28 U.S.C. §2281 ............................................................... 2, 6

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................................................... 2,6

Mass. G. L. c. 266, §120.............................................. 6,18

Mass. G. L. e. 272, §53 ........................................... passim

Index m

Other Authorisation

P age

Note, Declaratory Relief in the Criminal Law, 80 Harv.

L. Rev. 1490 (1967) ................................................... 22

Note, The First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine, 83

Harv. L. Rev. 844 (1970) 12, 13, 15, 22

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the

Administration of Justice, Task Force Report, The

Courts (1967) ........................................................ 13,14

Jn

(Unitrt of tit? litnit?b ^tat?o

October T erm , 1969

No.

ANN MARIE LE CLAIR, MARY LINDA LUSK, RUTH

VADNEY, JILL WATTS, WILLIAM PASTREICH,

NATIONAL WELFARE RIGHTS ORGANIZATION,

MASSACHUSETTS WELFARE RIGHTS ORGANIZA

TION,WORCESTER WELFARE RIGHTS ORGANIZA

TION, individually and on behalf of other persons similarly

situated,

APPELLANTS,

V.

GEORGE D. O’NEIL, Chief of Police of the City of

Worcester, WILLIAM T. BUCKLEY, District Attorney

for the City of Worcester, ROBERT H. QUINN, Attorney

General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, JOHN

P. GUILFOIL, Director of the Worcester Welfare Service

Office, ROBERT OTT, Commissioner of Welfare for the

Commonwealth of Massachusetts, individually and in their

official capacities,

APPELLEES.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Opinion Below

The opinion of the court below is as yet unreported

and is set forth in the Appendix, p. la, infra..

2

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1253 to review the district court’s denial of in

junctive and declaratory relief and dismissal of appellants’

complaint. The district court was composed of three

judges, as required by 28 U.S.C. §2281, to hear appellants’

prayers for interlocutory and permanent injunctions re

straining enforcement of a portion of a Massachusetts

statute, Mass. 6.L. c. 272, §53, on grounds of its federal

unconstitutionality. Original jurisdiction of the suit,

authorized by 42 U.S.C. §1983, was conferred on the dis

trict court by 28 U.S.C. §1343 (3).

The judgment of the court below was entered December

31, 1969 and is set forth in the Appendix, p. 10a, infra.

Timely notice of appeal to this Court was filed January

26, 1970.

Cases supporting this Court’s jurisdiction are Zmckler

v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241 (1967) ; and Cameron v. Johnson,

390 U.S. 611 (1968).

Statute Involved

This case involves the federal constitutionality of so

much of Mass. G.L. e. 272, §53, as proscribes “ disturbers

of the peace.”

§53 provides:

Stubborn children, runaways, common night walkers,

both male and female, common railers and brawlers,

persons who with offensive and disorderly act or

language accost or annoy persons of the opposite

sex, lewd, wanton and lascivious persons in speech

or behavior, idle and disorderly persons, prostitutes,

disturbers of the peace, keepers of noisy and disorder

ly houses and persons guilty of indecent exposure

may be punished by imprisonment in a jail or house

3

of correction for not more than six months, or by a

fine of not more than two hundred dollars, or by both

such fine and imprisonment.

Question Presented

Does the decision below, barring federal plaintiffs

threatened with repeated arrest and prosecution under a

hopelessly vague and overbroad state penal statute from

seeking a declaratory judgment concerning its federal

constitutionality, wTrongly abnegate the federal judicial

power, enforced by controlling decisions of this Court, to

protect First Amendment freedoms from such statutes'!

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the District of Massachusetts dismissing

appellants’ complaint seeking 1) declaratory relief invali

dating so much of Mass. G.L. c. 272, §53 as proscribes “ dis

turbers of the peace” and 2) injunctive relief against its

further enforcement against appellants and others simi

larly situated.

There are two classes of appellants. The first consists

of individuals who stand charged under the challenged

penal provision.1 The second consists of welfare rights

organizations2 to which the individual appellants belong

1 Appellant LeClair is chairman of the Worcester Welfare Rights

Organization (WWRO) and a recipient of Aid to Families with

Dependent Children (AFDC). Appellants Vadney, Lusk and

Watts are members of the WWRO, and Appellant Pastreich is an

organizer for the parent organization, National Welfare Rights

Organization.

2 National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) is a nation

wide voluntary association composed of individual members of

local affiliated welfare rights organizations, whose members are

primarily women receiving AFDC. The goals of NWRO include

adequate income for all Americans, dignity, justice and democracy.

4

and which represent the interests of “ needy mothers of

dependent children living in Worcester [Massachusetts]

who are . . . deterred by fear of arrest and prosecution

[under the challenged penal provision] from participating

in organizational and other First Amendment activities in

the Worcester Welfare Service Office, either as members

or prospective members of the [Worcester Welfare Rights

Organization] or the other plaintiff organizations, or as

nonmembers who seek information and assistance pro

vided by plaintiffs’ activities” (Complaint, If IV).

The following statement of facts was agreed to by coun

sel for appellants and the Attorney General of Massachu

setts, and accepted by the court below.

On July 3, 1969, at approximately 10:30 a.m., the five

To achieve these goals, NWRO distributes information as to the

entitlements and rights of recipients of public assistance, provides

technical assistance to help organize local welfare rights organiza

tions, and serves as a center for cooperation and coordination of

the activities of local welfare rights organizations.

Appellant Massachusetts Welfare Rights Organization (MWRO)

is a branch of NWRO and a voluntary association of more than

2,000 individuals in 23 local organizations throughout the Com

monwealth of Massachusetts. Its members are primarily, but not

solely, women with minor children receiving AFDC. The chief

concerns of the organization are to organize recipients into local

welfare rights organizations in order to obtain for each minor

child the fullest and most equitable aid to which he is entitled, to

publicize and remove the inequities and indignities in the present

administration of the welfare law, and to inform recipients of

public assistance of their rights and entitlements under present

welfare law.

Appellant Worcester Welfare Rights Organization (WWRO)

is a branch of NWRO and MWRO and a charitable corporation of

recipients of public assistance in the City of Worcester, Massa

chusetts. Its members are primarily women with minor children

receiving AFDC. Its primary concern is to establish and maintain

a local welfare rights organization so that recipients in Worcester

can obtain for each minor child the fullest and most equitable aid

to which he is entitled, to publicize and remove the inequities and

indignities in the present administration of the welfare law in

Worcester, and to inform recipients in Worcester of their full

rights and entitlements under law.

5

individual appellants, together with two other persons

not named in this action, entered the waiting room of the

Worcester Welfare Service Office, located at 9 Norwich

Street in Worcester. The waiting room is a large

“ L ’ ’-shaped room which has several chairs placed around

its perimeter and is separated from the actual offices and

work area of the Welfare Department by a wall. These

seven persons set up a folding card table near this wall,

between the door to the inner offices and the receptionist’s

window, in no one’s way.3 Some of them arranged piles of

literature4 on the table and distributed it to those welfare

recipients routinely entering the waiting room who came

up to the table and requested information. Others affixed

small signs to the walls of the waiting room, and one

displayed a flag bearing the insignia of the Welfare Rights

Organization. During the time these seven persons were

in the waiting room, only eight to ten welfare recipients

entered, and no more than three or four were present at

any one time.

After approximately fifteen minutes, an employee of the

Welfare Department entered the waiting room from the

rear office and asked them to remove the table. When

appellants maintained that they needed the table to dis

tribute their literature, this employee indicated that they

would be arrested if they did not comply with his request.

Shortly thereafter, two uniformed officers arrived and re

newed the employee’s request. When the table was not

removed, appellants were placed under arrest. They went

3 No employees of the Welfare Department work in the waiting

room.

4 This literature consisted of copies of the “ Massachusetts Wel

fare Rights Handbook” , a manual which employs a simple text,

cartoons, and sample request forms explaining' welfare benefits;

household supply request forms; and copies of “ Now — Goals of

the Welfare Rights Organization” .

6

with the officers quietly and without incident, at about

11:30 a.m.

As the court below found, the arrest and prosecution

of these appellants was predicated solely upon their in

sistence on quietly maintaining the folding card table in

a nonobstructive place in the waiting room to facilitate their

distribution of welfare rights literature (Appendix pp. 3a-

4a, infra). Nevertheless, in addition to the charge of tres

pass lodged against the individual appellants pursuant to

Mass. G. L. c. 266, §120,5 they were additionally charged

with being “ disturbers of the peace” under Mass. G.L. c.

272, §53.

On July 14, 1969, appellants filed their complaint in the

court below, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1983 and 28 U.S.C.

§§1343 (3), 2201 and 2281, seeking a declaratory judgment

invalidating the “ disturbers of the peace” law and pre

liminary and permanent injunctions restraining appellees’

enforcement of it against the individual appellants and

against other members and prospective members of the

appellant organizations. Appellants claimed that the “ dis

turbers of the peace” law was vague and overbroad. The

vagueness claim — that the law “ does not give sufficient

notice as to the limits of permissible behavior” -— was

stated in the following terms (Complaint, If VI A) :

The statute is unclear as to the scope of the limitations

which it imposes on plaintiffs’ ability to carry on or

ganizational and other First Amendment activities

and to petition government officials within a waiting

room of a public office, and this vagueness has a chill

ing effect on plaintiffs’ exercise of their First Amend

ment rights. The statute has not been clarified by any

5 This trespass law had only recently been sustained against fed

eral constitutional attack by another three judge panel of the dis

trict court. Hurley v. Hinckley, 304 F. Supp. 704 (D. Mass. 1.969),

aff’d sub nom. Doyle v. O’Brien, -------U .S .------- , January 12, 1970.

7

decision of the Massachusetts courts, nor is there any

readily apparent construction which suggests itself as

a vehicle for rehabilitating the vague language of the

statute in a single prosecution.

The overbreadth claim was stated principally in terms

of the repressive effect of the law on persons not yet ar

rested or prosecuted under it. These persons — whether

members of the appellant organizations who are deterred

by the law from engaging in associational or educational

activities or nonmembers who are deterred “ from joining

by the inhibition of [the individual appellants’ ] rights and

are . . . denied access to information which WWRO has

sought to make available to them” (Complaint, If VI B)

— are in a peculiary vulnerable position as respects the

law’s overbroad sweep.6

Appellees moved to dismiss, challenging, inter alia, the

standing of the appellant organizations to seek injunctive

relief restraining the pending prosecutions against the in

dividual appellants. No challenge was raised to the stand

ing of any of the appellants to seek declaratory relief in

validating the penal provision or to seek injunctive relief

restraining its future enforcement. Nevertheless, the court

below, ex mero motu, held that neither the individual ap

pellants nor the organizational appellants had standing to

seek that relief. It reached that result by holding: 1) That

the individual appellants had no standing to seek any

relief whatever because of the nature of their conduct; and

2) for reasons not clear from its opinion, that “ no valid

distinction relating to standing may, in our view, be drawn

between the various [appellants] ” (Appendix, p. 2a, infra).

Accordingly, it dismissed the complaint.

6 An amended complaint, filed August 2, 1969, challenged the

law enforcement officers’ good faith in adding on this second

charge to what was no more than a simple trespass case.

8

Believing that this novel restriction on access to the

federal courts unjustifiably impedes the protection due

freedoms of association and expression and conflicts with

controlling decisions of this Court, appellants prosecute

the instant appeal.

The Federal Question Presented is Substantial

The Decision Below Seriously Undermines the Power

and Responsibility of the Federal Courts to Protect Citi

zens From the Repressive Effects of Vague and Overbroad

State Laws Trenching Upon First and Fourteenth Amend

ment Rights.

Appellants begin with the statute which the decision

below insulates from federal constitutional scrutiny. The

portion of Mass. G. L. c. 272, §53 proscribing “ disturbers

of the peace” is an obviously vague and overbroad penal

law burdening freedom of expression.

The statute as a whole — “ a charming grabbag of crimi

nal prohibitions” 7 — was amended in 1943 to introduce

the challenged provision.8 Since then, the provision has

received no appellate interpretation. Nor had its common-

law antecedents received any very illuminating treatment

by the Massachusetts courts. No case in this century has

been found which sets forth the elements of the crime.

The leading case, now nearly a century old, appears to

be Commonwealth v. Oaks, 113 Mass. 8 (1873). There, the

defendant was convicted of being a “ disturber of the

peace” for shouting in the street. The Supreme Judicial

Court of Massachusetts affirmed his conviction, giving the

crime the following authoritative interpretation: a “ dis

7 Landry v. Daley, 280 F. Supp. 968, 969 (N.D. Til. 1968). The

full text of the statute is set forth at pp. 2-3, supra.

8 St. 1943, e. 377.

9

turber of the peace” is one whose acts “ are of such nature

as tend to annoy all good citizens, and do in fact annoy

any one present and not favoring them” (113 Mass, at 9).

The challenged statutory provision, as thus authorita

tively construed, offends numerous decisions of this Court

safeguarding freedom of expression from laws such as

these, viz., laws “ sweeping in a great variety of conduct

under a general and indefinite characterization, and leav

ing to the executive and judicial branches too wide a dis

cretion in [their] . . . application.” Cantwell v. Connecti

cut, 310 U.S. 296, 308 (1941). See also Terminiello v. Chi

cago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949); Edwards v. South Carolina, 372

TJ.S. 229 (1963); Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965).

In Terminiello, this Court reversed a conviction for dis

orderly conduct, obtained after the trial judge’s charge had

permitted the jury to convict Terminiello “ if his speech

stirred people to anger, invited public dispute or brought

about a condition of unrest” (337 U.S. at 5). This Court

held that “ a conviction resting upon any of those grounds

may not stand” (337) U.S. at 5), stating:

[A] function of free speech under our system of

government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best

serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of

unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they

are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often

provocative and challenging. It may strike at preju

dices and preconceptions and have profound unset

tling effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea

(337 U.S. at 4).

Terminiello was followed in Edwards v. South Carolina.,

supra, in which this Court reversed the breach of the peace

convictions of about 200 demonstrators who had marched

to the state Capitol in Columbia, South Carolina to petition

10

for redress of racially discriminatory practices. The city

manager of Columbia described their conduct as “ bois

terous” , “ loud” , and “ flamboyant” , consisting of a “ re

ligious harangue” by one of their leaders and the loud

singing of patriotic and religious songs, accompanied by

the stamping of feet and the clapping of hands (372 U.S.

at 233). Their conduct, albeit noisy and some impediment

to traffic, was peaceful and non-violent. They were arrested

and convicted of common law breach of the peace, a crime

“ not susceptible of exact definition” (372 U.S. at 231).

This court reversed, holding that the common law crime

was too vague and indefinite to permit the punishment of

conduct so intimately related to the First Amendment free

doms of free speech, peaceable assembly and petition for

redress of grievances (372 U.S. at 237-38).

Edwards was followed in Cox v. Louisiana, supra, in

which this Court invalidated Louisiana’s breach of the

peace statute, construed as punishing any act tending “ to

agitate, to arouse from a state of repose, to molest, to in

terrupt, to hinder, to disquiet.” This Court held: “ [A]s in

Terminiello and Edwards, the conviction under this statute

must be reversed as the statute is unconstitutional in that

it sweeps within its broad scope activities that are constitu

tionally protected free speech and assembly” (379 U.S.

at 552).

Under these decisions, the “ disturbers of the peace”

law, making criminality turn on witnesses ’ annoyance, ‘ ‘ in

volves calculations as to the boiling point of a particular

person or a particular group” (Ashton v. Kentucky, 381

U.S. 195, 200 (1966)) and thus must be condemned for over-

breadth. Here as in NAACP v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288, 307

(1961), in seeking “ to control or prevent activities consti

tutionally subject to state regulation” , the law employs

“ means which sweep unnecessarily broadly and thereby

invade the areas of protected freedoms” .

11

But the court below refused to invalidate this law, hold

ing that none of the appellants had standing to seek a de

claratory judgment invalidating it. There were essentially

three components of that decision :

1) The court below held that that the challenged pro

vision was “ general, and not specifically directed against

speech” as distinguished from statutes “ in terms. . .over-

broadly directed against speech,” (Appendix, pp. 7a-8a,

infra) ;

2) The court below held that the individual appellants

were guilty of “ hard-core conduct” and thus were de

barred from seeking federal declaratory or injunctive

relief; and

3) The court below held that the appellant organiza

tions had no greater claim than the individual appellants

to standing to seek federal declaratory or injunctive relief.

A. The court’s distinction between statutes “ in terms

. . .overbroadly directed against speech” and “ general”

statutes “ not specifically directed against speech” (Ap

pendix, pp. 7a.-8a, infra) cannot save the challenged provi

sion. Neither in Cantwell nor Terminiello nor Edwards nor

Cox was the penal provision “ in terms” directed against

freedom of expression. In Cox, for example, the statute

was generally phrased in terms of any act which produced

the proscribed result of arousing, molesting, disquieting,

etc. Nevertheless, it was struck down because of its sus

ceptibility to infringe First Amendment rights.

The distinction drawn below betrays a misunderstand

ing of the rationale of this Court’s overbreadth decisions.

These decisions do not depend upon the circumstances that

a statute is “ in terms” overbroadly directed against

speech. Rather, they are concerned with any statute whose

sphere of operation includes and overreaches constitution

ally protected speech, and which — through lack of the

12

“ narrow specificity” required of regulations that operate

in this area — is “ susceptible of sweeping and improper

application.” NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 432-433

(1963). This rationale was stated with clarity in Button,

supra, 371 U.S. at 432-33:

[I]n appraising a statute’s inhibitory effect upon. . .

rights [of free expression], this Court has not hesi

tated to take into account possible applications of the

statute in other factual contexts besides that at bar

. . .The objectionable quality of vagueness and over

breadth does not depend upon absence of fair notice

to a criminally accused or upon unchannelled delega

tion of legislative powers, but upon the danger of

tolerating, in the area of First Amendment freedoms,

the existence of a penal statute susceptible of sweep

ing and improper application. . . .Because First

Amendment freedoms need breathing space to sur

vive, government may regulate in the area only with

narrow specificity.

To require that a statute be directed “ in terms” against

speech is to ignore the fact that many statutes which are

susceptible of sweeping and improper application trench

ing upon freedom of expression are so hopelessly vague —

like this one — that it is impossible to discern what, if any

thing, they are directed against.9

9 It is discernible that ‘ ‘ such statutes historically have been

used in reprisal against unpopular groups or persons who espouse

unpopular causes. Cf. Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131; Cox v.

Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536; Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U.S. 154; Gar

ner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157.” Zwicker v. Boll, 391 U.S. 353, 354

(1968) (dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Douglas).

See also Note. The First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine, 83

Harv. L. Rev. 844, 861, n. 67 (1970) :

The distinction between “ by terms” and “ general” laws is

highly formalistic and rather elusive. How, for example,

13

The doctrines of vagueness and overbreadth are not un

related, for both respond to sweeping state regulations

that have the vice of leaving too much discretion in the

control of expression to the police, prosecutors and the

courts. The mere presence of such statutes on the books —

their “ existence” (NAACP v. Button, supra, 371 IT.S. at

433) — has a tendency to frighten off free expression by

requiring the citizen to steer far clear of the danger zone.

See, e. g., Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 97-98 (1940) ;

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360, 378-79 (1964); Dombrow-

ski v. Pfister, 380 IT.S. 479, 494 (1965). Finally, such laws

raise a threat to the very principle of legality itself.

[UJnder our democratic system of government, law

making is not entrusted to the moment-to-moment

judgment of the policeman on his beat.......... To let a

policeman’s command become equivalent to a criminal

statute comes dangerously near making our govern

ment one of men rather than of laws. . .There are

ample ways to protect the domestic tranquility with

out subjecting First Amendment freedoms to such a

clumsy and unwieldy weapon (Gregory v. Chicago,

394 IT.S. I ll , 120-21 (1969) (concurring opinion of

Mr. Justice Black)).

The disadvantages to the community of tolerating these

laws on the books have long been recognized by legal schol

ars; only recently they were reiterated by the President’s

Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration

of Justice in its Task Force Report, The Courts, pages

103-04 (1967);

should laws punishing improper solictitation of legal busi

ness be categorized? Cf. NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415

(1963) (barratry law as construed held void for overbreadth).

14

Foremost among its disadvantages is that it consti

tutes an abandonment of the basic principle upon

which the whole system of criminal justice in a demo

cratic community rests, close control over exercise of

the authority delegated to officials to employ force and

coercion. This control is to be found in carefully de

fined laws and in judicial and administrative account

ability. The looseness of the laws constitutes a charter

of authority on the street whenever the police deem it

desirable. The practical costs of this departure from

principle are significant. One of its consequences is to

communicate to the people who tend to be the object

of these laws the idea that law enforcement is not a

regularized, authoritative procedure, but largely a

matter of arbitrary behavior by the authorities. The

application of these laws often tends to discriminate

against the poor and subcultural groups in the popu

lation. It is unjust to structure law enforcement in

such a way that poverty itself becomes a crime. And

it is costly for society when the law arouses the feel

ings associated with these laws in the ghetto, a sense

of persecution and helplessness before official power

and hostility to police and other authority that may

tend to generate the very conditions of criminality

society is seeking to extirpate.

B. The high social and legal cost that attends the ex

istence of these laws requires a more effective judicial

remedy than mere reversal of criminal convictions arising

15

under them: they must be expunged altogether.10 This

court has plainly recognized that point by relaxing tradi

tional rules of standing in cases where such laws are chal

lenged under the First Amendment. We must be quick to

concede with the court below that “ [t]he extent of accept

able relaxation has never been precisely defined” (Appen

dix, p. 7a, infra). Nevertheless, the Court has insisted that

standing doctrines be adapted to favor challenges to vague

and overbroad statutes that may jeopardize First Amend

ment freedoms.

We have consistently allowed attacks on overly broad

statutes with no requirement that the person making

the attack demonstrate that his own conduct could not

be regulated by a statute drawn with the requisite

narrow specificity . . . By permitting determination of

the invalidity of these statutes without regard to the

permissibility of some regulation on the facts of par

ticular cases, we have, in effect, avoided making vin

dication of freedom of expression await the outcome

of protracted litigation (Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380

U.8. 479, 486-87 (1965)).

10 See Note, The First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine, 83

Harv. L. Rev. 844, 874-75 (1970) :

[W]hen analysis . . . is focused on the judicial process neces

sary to cure either statutory vagueness or statutory over

breadth, the two constitutional vices appear in practice to

merge. If a vague statute is not held bad on its face, it is re

mitted to a process of hammering out the limits of interven

tion under the impact of particular fact situations in the

expectation that over time a core of definite coverage will

take shape by accretion. But a prolonged and costly process

of bringing clarity to statutory commands, like the uncertain

process of case by case excision, holds preferred freedoms in

abeyance for an indefinite period and tolerates the intimida

tion of protected activity caused by a law whose (literal or

permissible) scope is uncertain. Thus the doctrines of vague

ness and overbreadth supply identical considerations militat

ing against piecemeal judicial rehabilitation of statutes when

preferred rights are at stake

16

But what the court below has done is to turn this Court’s

doctrine on its head: it has specifically required of the in

dividual appellants that they demonstrate that their own

conduct could not be regulated by a more narrowly drawn

statute. It has refused “ to take into account possible ap

plications of the statute in other factual contexts besides

that at bar” (NAACP v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 432).

It has refused to recognize that the statute “ may be invalid

if it prohibits privileged exercises of First Amendment

rights whether or not the record discloses that the [indi

vidual appellants have] engaged in privileged conduct”

{ibid.).

The court below reached this wrong result by asking the

wrong threshold question. It posed this question as

“ whether plaintiffs had a constitutional right to erect a

table in the waiting room in connection with their distrib

uting literature and their efforts to organize welfare recipi

ents” (Appendix, p. 4a, infra). It held that they did not, and

then refused to allow them “ to argue that in factual situ

ations not presented by [this] case enforcement of the

statute would pass the bounds of state power” (Appendix,

p. 5a, infra).

We may assume, for purposes of this case, that appel

lants did not have “ a constitutional right” to erect their

table to distribute literature immune against regulation

or even prohibition under a narrowly drawn statute such

as a trespass law.11 But neither did the protestors in, say,

Cantwell or Edivards have “ a constitutional right” to en

gage in their activities immune against all manner of crim

inal sanctions, however narrowly drawn. In Edwards, this

11 The individual appellants have been convicted of trespass, and

we may assume for purposes of this decision that this narrowly

drawn penal provision passes constitutional muster and may be

constitutionally applied to their activities. See Hurley v. Hinckley,

304 F. Supp. 704 (D. Mass. 1969) (3 judge court) aff’d sub noun.

Doyle v. O’Brien, —— U .S .-----38 U.S. L.W. 3253, January 12,

1970.

17

Court distinguished the case before it from one involving

“ the evenhanded application of a precise and narrowly

drawn regulatory statute evincing a legislative judgment

that certain specific conduct be limited or proscribed. If,

for example, the petitioners had been convicted upon evi

dence that they had violated a law regulating traffic, or

had disobeyed a law reasonably limiting the periods during

which the State House grounds were open to the public,

this would be a different case. See Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 U.S. 296, 307-08. . .; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157,

207 . . . (concurring opinion) ” 12

But the individual appellants do have “ a constitutional

right” not to be additionally subjected to an amorphous

criminal prohibition like “ disturbers of the peace.” More

than that, they have a right under controlling decisions of

this Court to seek to invalidate that vague and overbroad

law. And quite apart from the matter of the standing of

the individual appellants to do so, the appellant organiza

tions have standing to seek the latter relief.

C. Although the court below should have taken into

account “ possible applications of the statute in other fac

tual contexts besides that at bar” , the law’s application

even in this context reveals its susceptibility to abuse. The

gravamen of the charge against the individual appellants

is simply that they quietly set up a folding card table

against one wall of the welfare office waiting room in order

to facilitate their distribution of welfare rights literature

(see Appendix, pp. 3a.-4a, infra). For this, they were ar

rested, charged with and convicted of trespass — properly,

we assume, see note 11, supra.

12 Mr. Justice Harlan’s concurring opinion in Garner stressed

that the vagueness and overbreadth doctrines “ demand of the

state legislature that it focus on the nature of the otherwise “ pro

tected” conduct it is prohibting, and that it then make a legislative

judgment as to whether that conduct presents so clear and present

a danger to the welfare of the community that it may legitimately

be criminally proscribed” . (368 U.S. at 203).

18

But in addition to this charge, the appellee officers lodged

a second, more serious,13 charge against the individual ap

pellants. It is hard to escape the conclusion that this second

charge — of being “ disturbers of the peace” — added

nothing to the first but a broad, drastic, efficacious damper

upon unpopular expression. One might well question the

good faith of the officers in invoking, cumulatively, this

second vague, menacing charge.14 But proving the officers’

bad faith would be a different matter for, under this

Court’s decision in Cameron v7. Johnson, 390 U.S. 611, 621

(1968), the individual appellants would have to show that

the officers added on the second charge against them “ with

no expectation of convictions.”

The very impossibility of such a showing points up the

repressive potential of the charge and the statute on which

it rests. “ Disturbers of the peace” is so vague and over

broad a penal provision that conviction under it would in

variably be possible. All that police officers or welfare offi

cials are required to do in order to make out a case against

the individual appellants is to testify that they were an

noyed by and did not favor their demonstration (See pp.

8-9, supra,).15

13 Trespass carried only a small maximum fine at the time, where

as the “ disturbers of the peace” provision carries a maximum

penalty of six months in jail and a $200 fine (see Appendix, p.

2a, infra).

14 See appellants’ amended complaint, discussed, supra, at note 6.

15 Subsequent to the decision below, on February 17, 1970, four

of the five individual appellants were tried in Worcester’s no-record

court. That court refused to entertain these appellants’ federal

constitutional claims, ruling that they were in the exclusive pro

vince of higher courts. Simply upon the testimony of a welfare

official that the quiet presence of these appellants disturbed the

decorum of the welfare office by attracting the attention of his

subordinates, three of these appellants (LeClair, Lusk and Pas-

treich) were convicted. They have claimed an appeal to the crim

inal court of record for a trial de novo. The fourth appellant —

Jill Watts — was acquitted on precisely the same testimony.

19

And that same kind of testimony could lead to the arrest,

prosecution and conviction of the individual appellants or

of other members or prospective members of the organiza

tional appellants were they to engage in any of a range

of associational and educational activities in connection

with their welfare rights campaign. For example, that

same kind of testimony could lead to their arrest, prose

cution and conviction if they were to peacefully and non-

obstrucively distribute their literature outside the welfare

office.16

That is precisely why the appellant organizations, quite

apart from the individual appellants, have standing to

raise the possible, mischievous applications of the statute

that menace a wide range of their privileged activities.

The gravamen of their claim is that needy mothers of de

pendent children in Worcester, Massachusetts, who have

not been arrested or prosecuted “ are deterred by fear of

arrest and prosecution [under §53] from participating in

organizational and other First Amendment activities in

the Worcester Welfare Service Office, either as members

or prospective members of the WWRO or the other [ap

pellant] organizations, or as nonmembers who seek infor

mation and assistance provided by appellants’ activities.”

(Complaint, U IV). Moreover those persons “ who are

not members of a welfare rights organization are being

restrained from joining by the inhibition of [appellants’]

rights, and are also being denied access to information

which WWRO has sought to make available to them”

(Complaint, 1J VI B).

In dismissing the complaint on the papers, the court

below could not have treated these allegations as frivolous

16 “ It is no answer to say that the statute would not be applied

in such a case.” (Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 II.S. 589,

599 (1967)), for as long as the possibility exists, the statute poses

a danger to First Amendment freedoms, see Part A, supra.

20

in law or in fact; indeed, the application of the ‘ ‘ disturb

ers of the peace” provision by the Worcester police seems

to have triggered its subsequent use by four other police

departments against persons connected with the Massachu

setts Welfare Rights Organization.

Decisions of this Court make clear that these organi

zations have standing to assert the constitutional rights

of their members, prospective members and those they

seek to serve. See NAACP v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at

428.17 See also National Student Association v. Hershey,

412 F.2d 1103, 1120-21 (D.C. Cir. 1969). The practical rea

son why the appellant organizations have standing to

challenge the law is simply that they are in the best posi

tion to demonstrate the drastic damper that the law im

poses on the whole range of their associational and educa

tional activities. Prosecution or conviction under this law

does not constitute the central threat to these activities.

Rather, the central threat is posed by the law’s potential

and actual use to terminate expression through police ac

tion. As far as the First Amendment is concerned, the

damage is done when the expression is terminated.

This is so for the obvious reason that expression de

signed to protest social ills or to stimulate social change

must be timely to be effective. Activities such as appel

lants’ must be carried on while the political and social is

sues they address are alive and the authorities and the

public are sensitive to them. If peaceful change through

political persuasion is to remain a possibility in our so

ciety, a minority’s capacity to carry its just moral claims

to the public must not be crippled. Arrest, without more,

has that crippling effect.

17 The similarity of appellants’ nascent associational activities to

those of labor or civil rights groups is striking, but need not be

pursued at length here.

21

If the police can terminate privileged activities and ar

rest the persons involved, First Amendment rights mean

little. Of course, those arrested may interpose the First

Amendment as a defense: their prosecutions may later be

dropped; they may be acquitted; or they may have their

convictions reversed on appeal. But the damage will have

been done; their privileged activities will have been ter

minated and their communication frustrated at the only

time when it was meaningful. It is in this intensely prac

tical sense that freedoms of association and expression

“ are delicate and vulnerable, as well as supremely precious

in our society.” NAACP v. Button, supra, 371 IT.S. at 433.

If First Amendment freedoms are to be real and not

merely academic, they must encompass the right to engage

in the protected activity itself: they must protect mem

bers and sympathizers of the appellant organizations from

arrest and other police interference. That protection can

only be amply afforded by striking at the source of the

overhanging threat — the illegal laws themselves, which

grant to the police censorial discretion over the citizen’s

fundamental freedoms. This Court’s observation in Bag

gett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360, 373 (1964) is squarely in

point: “ Well-intentioned prosecutors and judicials safe

guards do not neutralize the vice of a vague law. ’ ’

D. This Court has repeatedly reaffirmed the protective

jurisdiction of the federal courts to provide declaratory

relief invalidating just such laws. In ZwicMer v. Koota,

(ZwicMer 1), 389 U.S. 241 (1967), the Court reaffirmed the

primary role of the federal judiciary in deciding questions

of federal law, particularly questions concerning the con

stitutionality of a state statute on its face for repugnancy

to the First Amendment. “ In such case to force the plain

tiff who has commenced a federal action to suffer the delay

of state court proceedings might itself effect the imper

missible chilling of the very constitutional right he seeks

22

to protect.” (389 TT.S. at 252). Accord, Cameron v. John

son, 390II.S. 611, 615 (1968).

Of course, not everyone has standing to challenge such

a statute, even though society’s stake in its invalidation

is large. Thus, this Court has required that the issue of the

statute’s validity be more than just an abstract question:

it “ must be presented in the context of a specific live griev

ance.” Golden v. Zwickler (Zwickler II), 394 U.S. 103, 110

(1969).18 But this requirement is nothing more than the

basic notion of justiciability, enunciated in Maryland Cas

ualty Go. v. Pacific Coal and Oil Co., 312 U.S. 270, 273

(1941) as:

Basically the question in each case is whether the facts

alleged, under all the circumstances, show that there

is a substantial controversy, between parties having

adverse legal interests, of sufficient immediacy and

reality to warrant the issuance of a declaratory judg

ment.

The present case plainly meets that test, for we take it

to be indisputable that there is a real, substantial and im

mediate controversy between the parties as to the validity

of the “ disturbers of the peace” provision.19 The court

below found nothing to the contrary. But it proceeded to

introduce a new, more restrictive test phrased in terms of

standing — a test which it thought justified by certain

18“ [T]he standing objection survives to protect court and

prosecutor from idle litigation from the unharmed, merely curious

or truculent citizen. ” Note, Declaratory Belief in the Criminal Law,

80 Harv. L. Rev. 1490, 1509 (1967).

19 See Note, The First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine, 83

Harv. L. Rev. 844, 909 (1970), which argues that “ a party’s

‘ standing ’ to assert overbreadth should be dependent on the same

factors which determine whether the challenged statute should be

invalidated on its face or not. ’ ’

passing references of this Court to the term “ hard-core

conduct” .20

Appellants do not doubt or deny the validity of some

such restriction upon justiciability (or standing) as is ex

pressed by the “ hard-core” concept. We may assume that

if the individual appellants had thrown their card table or

their literature about the welfare office a different case

would be presented from the case at bar. This would be so,

simply, because the application of the “ disturbers” stat

ute to extreme conduct of that sort could not possibly signal

any overhanging threat of the law’s use within the scope

of First Amendment concern. But if the phrase “ hard

core conduct” has—as we think it does—the utility of

making this point, it also has considerable ambiguity.

Misunderstood and extravagantly employed as it was be

low, the “ hard-core” notion trenches deeply on the con

trolling, protective decisions of this Court discussed in

parts B and C, supra. So used, it threatens broadside

abridgement of vital procedural safeguards devised by the

court to protect First Amendment freedoms from the

destructive impact of vague and overbroad penal provi

sions such as that under attack here.

The subversive effect of this novel limitation of the

federal protective jurisdiction is nicely illustrated by ap

plying the reasoning of the court below to ZwicMer I. Un

der the “ hard-core” test of standing used below, Zwickler

would have been forclosed from seeking declaratory relief

against the anonymous handbill statute if, for example,

he had also engaged in conduct justifying a charge of

littering. He would thereby have been guilty of “ hard

core conduct” within the lexicon of the court below: i.e.,

conduct which could be reached by a law drawn with the

“ requisite narrow specificity” (Bombrowski, supra, 380

20 See Bombrowski v. Pfister, supra, 380 U.S. at 491-92; Brown

v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131, 142 (1966) (concurring opinion).

24

U.S. at 486). Accordingly lie would have been denied

standing to challenge even a statute not so drawn.

But in ZwicJcler I, there was no inquiry by this Court

as to whether Zwickler’s activities might have been regu

lated by a more narrowly drawn statute. Indeed, in the

subsequent case of Cameron v. Johnson, supra, the Court

upheld a challenged statute, together with the appellants’

standing to challenge it, while at the same time implying

that that very statute could validly be applied to their ac

tivities.

The court below conceded (Appendix, p. 8a, supra)

that its decision brought it into conflict with numerous deci

sions of other lower federal courts. See, e.g., Baker v. Bind-

ner, 274 F. Supp. 658 (W.D. Ky. 1967) (3-judge court) ;

Carmichael v. Allen, 267 F. Supp. 985 (N.D. Ca. 1966)

(3-judge Court); Lanclry v. Daley, 280 F. Supp. 968 (N.D.

111. 1968). The conflict is real indeed, generated by those

courts’ firm adherence to the controlling decisions of this

Court previously cited. And recently the Court of Ap

peals for the Seventh Circuit decisively rejected an at

tempt to give the “ hard-core doctrine” the interpretation

adopted by the court below. Soglin v. Kauffman, 418 F.2d

163, 166 (7th Cir. 1969).

The court below offered no considerations of policy to

justify its extension of the “ hard-core” concept so as to

undercut such decisions of this Court as ZwicMer I, nor

did it appear to recognize the mischievous effect its ruling

would have upon the federal protective jurisdiction that

is indispensable to safeguard First Amendment freedoms

against vague and overbroad state penal laws. Indeed

the principal effect of the ruling below is to “ only delay

the drafting and enactment of [a statute] which in a con

stitutional manner wouuld protect legitimate regulation

of the activities here involved.” Guyot v. Pierce, 372 F.2d

25

658, 663 (5th Cir. 1967).21 The decision below is unsup

ported by reason or policy, destructive of vital First

Amendment safeguards, and in conflict, with controlling

decisions of this Court. It urgently requires correction

by this Court.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, appellants pray that prob

able jurisdiction be noted.

Respectfully submitted,

M elvyn Z arr

A llay Gf. R odgers

L awrence K otin

B arbara S chwartzbaum

80 Boylston Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02116

Attorneys for Appellants

Of Counsel:

A nthony Gf. A msterdam

S tephen B ardige

A ndrew L. P hilip

21 Indeed, in Hurley v. Hinckley, supra, noted in the decision

below, Appendix, p. 2a, infra, another three-judge panel of the

Massachusetts District Court reached and decided the question

of the validity of the Massachusetts trespass statute, in a suit

brought by welfare rights demonstrators charged for activities

much more instrusive upon the routine of the welfare office than

those of the individual appellants here. The district court held

the statute constitutional and this Court summarily affirmed,

Doyle v. O’Brien, —— U .S .------ , January 12, 1970.

la

APPENDIX

Opinion of the United States District Court

For the District of Massachusetts

Civil Action No. 69-748-J

U nited S tates D istrict Court

D istrict op Massachusetts

A nn M arie L eClair, M ary L inda L usk , R uth Y adney,

■Jill W atts, W illiam P astreich, National W elfare

R ights Organization, M assachusetts W elfare R ights

Organization, W orcester W elfare R ights Organization,

individually and on behalf of other persons similarly

situated,

v.

George D. O ’Neil, Chief of Police of the City of Worcester,

W illiam T. B uckley', District Attorney for the City of

Worcester, R obert H. Qu in n , Attorney General of the

Commonwealth of Massachusetts, J ohn P. Guilfoil, Di

rector of the Worcester Welfare Service Office, R obert

Ott , Commissioner of Welfare for the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts, individually and in their official capacities,

DEFENDANTS.

Before A ldrich, Circuit Judge,

J ulian and Garrity, District Judges.

OPINION

December 23, 1969

A ldrich , Circuit Judge. Before isolating the ques

tions of standing which we find determinative of this case

in which three judges in the District of Massachusetts are

asked to consider the constitutionality of a Massachusetts

disturbing-the-peace statute, a detailed statement of the

facts and background would be appropriate.

2a

On June 20, 1969 another panel of three judges sitting

in this district in the ease of Hurley v. Hinckley, Chief of

Police, 304 F. Supp. 704, a class suit brought by and on

behalf of plaintiffs similar to those presently at bar,

held that Mass. Gr.L. c. 266, § 120, a criminal trespass

statute, hereafter § 120, did not violate due process because

of vagueness and overbreadth, or unconstitutionally limit

the plaintiffs’ First Amendment rights sought to be exer

cised in a Welfare Service Office. On July 3, 1969 the pres

ent plaintiffs engaged in activities more fully described

hereafter, in another Welfare Service Office, and refused

to desist from certain conduct until the police were called.

On July 5 they were charged in a local court with trespass

under § 120, and with being “ distributors of the peace,”

under Mass, Gr.L. c. 272, § 53.1 Section 53 carries a maxi

mum penalty of six montlis in jail, and a $200 fine where

as 4 120 carries only a small fine. Trial was set for both

sets of cases on July 17.

On July 14 plaintiffs filed the present complaint. The

defendants moved to dismiss,2 but stipulated that the prose

cution under § 53 would be postponed until further notice.

After the three-judge court was constituted defendants

were temporarily restrained from prosecuting the § 53

1 “ Stubborn children, runaways, common night walkers, both

male and female, common railers and brawlers, persons who with

offensive and disorderly act or language accost or annoy persons

of the opposite sex, lewd, wanton and lascivious persons in speech

or behavior, idle and disorderly persons, prostitutes, disturbers of

the peace, keepers of noisy and disorderly houses and persons

guilty of indecent exposure may be punished by imprisonment in

a jail or house of correction for not more than six months, or by

a fine of not more that two hundred dollars, or by both such fine

and imprisonment.”

2 While defendants ’ motion to dismiss challenges the standing

only of plaintiffs not being prosecuted in the state court, the argu

ment at the hearing encompassed all plaintiffs. As explained infra,

no valid distinction relating to standing may, in our view, be drawn

between the various plaintiffs.

3a

actions until further order of court, and after hearing, a

temporary injunction was entered to the same effect. On

this same day the court heard defendants’ motion to dis

miss. Meanwhile, plaintiffs had been convicted of tres

pass under § 120, from which they have claimed an appeal.

The complaint alleges that four of the plaintiffs are

members of the Worcester (Massachusetts) Welfare Rights

Organization, (WWRO), a branch of geographically larger

organizations, and that one is a Worcester recipient of Aid

to Families with Dependent Children. The fifth plain

tiff, William Pastreich, is a paid organizer. The defend

ants are the Worcester Chief of Police, the District Attor

ney, the Attorney General and various Welfare officials.

Plaintiffs assert that, they bring this action on behalf of

themselves and “ needy mothers of dependent children liv

ing in Worcester who are threatened and intimidated by

the arrest and prosecution of the above-named plaintiffs

and who are deterred by fear of arrest and prosecution

from participating in organizational and other First

Amendment activities in the Worcester Welfare Service

Office.”

According to the complaint the five plaintiffs, and two

others, entered the waiting room of the Worcester Welfare

Office, hung up some signs, and distributed circulars. In

the wall between the waiting room and the inner office

where applicants were processed there was a receptionist’s

window. Plaintiffs set up a folding card table near this

wall. Plaintiffs created no other disturbance, but refused

requests to remove the table until the police arrived.3

The prosecution which plaintiffs seek to enjoin relates

3 Other facts, of no relevancy, are omitted. Considerable space

was spent in the record and at the argument over plaintiffs’ as

sertion that before they arrived they had received permission to

erect the table. Not only did defendants deny this, but plaintiffs

ultimately conceded, as they must, that any permission was duly

revoked and that their conduct continued nonetheless.

4a

solely to plaintiffs’ insistence on maintaining the table;

no other strictures were placed upon them. They were

not requested to leave, either before or after they set up

the table, or to reduce their number, or to desist from

assembling or organizing, to take down their signs or to

stop distributing their circulars. Additionally, the com

plaint refers to plaintiffs’ right to “ petition.” There

are no factual allegations that they were seeking to peti

tion, let alone that they were prevented from doing so.

Turning to the question whether plaintiffs have standing

to maintain the present action, plaintiffs base their claim

on the contention that they are seeking to vindicate First

Amendment rights. Even if freedom to exercise these

rights exists within the Welfare Office, which, for present

purposes, we assume, plaintiffs face substantial difficulties.

These may be divided into two basic questions: whether

plaintiffs had a constitutional right to erect a table in the

waiting room in connection with their distributing litera

ture and their efforts to organize welfare recipients, and

whether, if they did not, they had standing to protect the

future exercise of rights from “ chills” resulting from the

use of a potentially broad statute against persons claim

ing and exercising First Amendment rights.4

4 There is still further matter, whether since the state proceed

ings had previously commenced, plaintiffs are precluded from

maintaining this action by reason of 28 U.S.C. § 2283. We do not

reach that question. See Baines v. City of Danville, 4 Cir., 1964,

337 F.2d 579, cert, denied sub nom. Chase v. McCain, 1965, 381

U.S. 939; Cooper v. Hutchinson, 3 Cir., 1950, 184 F.2d 119, 124

and n. 11; Landry v. Daley, N.D. 111., 1968, 288 F. Supp. 200, 221-

25, appeal dismissed sub. nom. Landry v. Boyle, 393 U.S. 220.

Comment, Federal Injunctions Against State Actions, 35 Geo.

Wash. L. Rev. 744, 782 (1967) ; Note, Power to Enjoin State

Prosecutions Violative of Federally Protected Rights, 114 TJ. Pa.

L. Rev. 561 (1966) ; Brewer, Dombroski v. Pfister: Federal In

junctions Against State Prosecutions in Civil Rights Cases — A

New Trend in Federal-States Judicial Relations, 34 Fordham L.

Rev. 71, 97-103; Note, Incompatibility — The Touchstone of Sec

tion 2283’s Express Authorization Exception, 50 U. Va. L. Rev.

1404, 1414-23 (1964).

The usual prerequisite for a successful attack upon a

statute for constitutional infirmity is that one’s own con

duct be constitutionally protected; normally a party may

not rely on another’s constitutional rights. United States

v. Raines, 1960, 362 TT.S. 17, 21; Yazoo d M.V.R.R. v.

Jackson Vinegar Co., 1912, 226 U.S. 217. If a party is

prosecuted for engaging in conduct which the state has

power to punish he will not normally be allowed to argue

that in factual situations not presented by his case enforce

ment of the statute would pass the bounds of state power.

His is not the most appropriate case for decision of issues

turning on the impact of the statute in imagined situations

involving quite different activities. See A. Bickel, The

Least Dangerous Branch, 149 (1962). If this rule is to be

applied in the case at bar we are clear that plaintiffs have

no standing. Whatever First Amendment rights existed

in the Welfare Office, they could not be exercised at the

expense of the primary purpose the office was designed to

serve.

“ Even where municipal or state property is open to the

public generally, the exercise of First Amendment rights

may be regulated so as to prevent interference with the

use to which the property is ordinarily put by the State.”

Food Employees v. Logan Valley Plaza, Inc., 1968, 391

U.S. 308, 320 (dictum). See Note, Regulation of Demon

strations, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 1773, 1776-77, (1967). Cf.

Adderley v. Florida 1966, 385 U.S. 39; Cox v. New Hamp

shire, 1941, 312 U.S. 569. Reasonable latitude must be

permitted to the persons in charge. Waiting rooms are not

traditional forums of protest, and a high degree of peace

and order is necessary to their normal operation. Cf.

Note, Regulation of Demonstrations, supra, at 1777.

Under these circumstances the only question is whether

the welfare officials, in curtailing plaintiffs’ activities,

abused their discretion. Massachusetts Welfare Rights Or

6a

ganization v. Ott, 1 Cir., 11/6/69; Wolin v. Port of New

York Authority, 2 Cir., 1968, 392 F.2d 83, cert, denied,

393 U.S. 940. We cannot say that it was unreasonable to

object to the erection of a table within the waiting room.

We distinguish the suggestion in Wolin that it may be a

question of fact whether it is unreasonable to object to a

table in a large terminal building. In the present case

quite apart from any question whether the particular lo

cation interfered with the privacy of applicants wishing

to talk with employees in the inner office, we hold that

it was within the discretion of the welfare officials to

determine that a table occupied by non-applicants unduly

burdened the capacity of a room, necessarily of limited

size, provided for waiting applicants. Plaintiffs assert

that at the time in question there were never more than

four applicants in the room. Non constat that many more

might well be expected at other times. Plaintiffs’ own

conduct suggests as much. It was scarcely necessary to

introduce five plaintiffs and two others to proselytize four

applicants.5 In any normal waiting room, such as that

described in the complaint, extra furniture has a poten

tial for obstruction and officials need not wait until the

potential is realized before acting. We conclude that no

undue restriction was placed upon plaintiffs’ exercise of

First Amendment rights.

Because of what is termed the chilling effect of uncon

stitutional statutes and prosecutions upon the general

5 Alternatively, the fact that plaintiffs entered the waiting room

seven strong to assert a right to maintain a table may suggest

that the issue was not simply the table as such, but was who was

to be the boss. Additionally, if one were to look to labor union cases

as a guide, the table might be taken to suggest that the Welfare

officials were taking sides and affirmatively endorsing the re

cruitment activities of the WWRO, so that speech was, in effect,

being put into their mouths. If this was the confrontation, or the

issue, plainly it must be resolved in favor of those in charge of

the office.

exercise of First Amendment rights by any person wish

ing to do so, courts have sometimes relaxed the require

ment that the complaining party show that as to him a

statute has been applied unconstitutionally, that is, that

his conduct was constitutionally privileged and could not

be prohibited by the state. See, e.g., Thornhill v. Alabama,

1940, 310 U.S. 88; Winters v. New York, 1948, 333 U.S.

507; Runs v. New York, 1951, 340 U.S. 290. But cf. Feiner

v. New York, 1951, 340 U.S. 315; Dennis v. United States,

1951, 341 U.S. 494; United States v. Petrillo, 1947, 332 U.S.

1. The extent of acceptable relaxation has never been pre

cisely defined. See generally Sedler, Standing to Assert

Constitutional Jus Terti in the Supreme Court, 71 Yale

L. J. 599 (1962); Amsterdam, Note, The Void-For-Vague-

ness Doctrine in the Supreme Court, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev.

67 (1960). Mr. Justice Brennan, concurring in Brown v.

Louisiana, 1966, 383 U.S. 131, 143, expressed the view,

at 147-48 that “ It suffices that petitioners’ conduct was

arguably constitutionally protected and was ‘ not the sort

of ‘ ‘ hard-core ’ ’ conduct that would obviously be prohibited

under any construction.’ ” 6 We would elaborate on this

suggestion. Since the purpose of permitting a party,

not himself engaged in constitutionally protected conduct,

to attack a statute is to remove the chilling effect for the

benefit of others, the standard should be set by the reason

itself: do the overall circumstances reasonably suggest

that regardless of whether the plaintiff’s particular conduct

was constitutionally privileged, privileged conduct would

not be exempted from prosecution?

The chilling effect may be found in the fact that the

statute in terms is overbroadly directed against speech.

6 The inner quote was from Dombrowski v. Pfister, 1965, 380 U.S.

479, at 491-92, an abstention case. With great, deference, we sug

gest the problems of abstention and standing are not necessarily

the same.

8a

This was the case in, e.g., Thornhill v. Alabama, supra;

Winters v. New York, supra. See Sedler; supra, 71 Yale

L. J. 599, 614-25 (1962). In such a situation it may well

be anticipated that the authorities, so directed, cannot

be counted upon to restrict themselves to clearly legitimate

prosecutions. If, on the other hand, the statute is general,

and not specifically directed against speech, one must look

beyond the statute to the circumstances as a whole in order

to determine whether other persons, viewing what the

authorities have in fact done, might justifiably appre

hend that bona fide attempts on their part to exercise

First Amendment rights would be likely to be prose

cuted.7

In applying this test we do not look at any single mat

ter, but at the overall circumstances. So viewing the case

at bar, we do not think it could be fairly said that the

statute was being employed to inhibit First Amendment

rights. Plaintiffs were accorded throughout broad liberties

of speech and association. Their presence was not objected

to ; their soliciting, their speech, their organizational ac

7 We cannot suggest that the courts have adopted this ap

proach. Indeed, one can find a case such as Baker v. Binder, W.D.

Ky., 1967, 274 F. Supp. 658, where the court drew no distinction

between statutes addressed to speech and statutes addressed to

conduct generally, and granted relief after specifically finding

that the police had acted in an exemplary fashion under the cir

cumstances. The issue of standing was not even considered. A dis

senting judge urged that there should be abstention. In other

cases disorderly conduct statutes have been declared unconstitu

tional on their face without close discussion of the quality of past

official conduct. See Landry v. Daley, N.D. 111., 1968, 280 F. Supp.

969 (incorporating by reference 280 F. Supp. 944-52) ; Commer

cial v. Allen, N.D. Ga., 1965, 267 F. Supp. 985. On the other hand,

some cases could be taken to implicitly indicate that when general

statutes are under attack there is no standing to assert the First

Amendment rights of others. See United States v. Petrillo, supra;

Sedler, supra, 71 Yale L. J. 599, 614-25 (1962). Cf. Feiner v. New

York, supra.

9a

tivities were not interrupted. The sole stricture was

against obstruction of the office. In seeking to analogize

Brown v. Louisianna, supra, plaintiffs overlook that the

protesters there were arrested and removed for merely

being present. Here plaintiffs were asked only to cease the

physically obstructing part of their conduct. The authori

ties distinguished between permissible, non-disturbing

speech, and conduct that they could reasonably feel in

terfered with the activities of the office.8

Plaintiffs accordingly fail to fit even a liberal test of

standing. Their assertion that their prosecution “ re

strained [plaintiffs and others] in the exercise of their

right to assemble, organize, distribute literature and peti

tion’ ’ and that other persons were “ being denied access

to information which WWRO has sought to make avail

able to them” are mere conclusions of the pleader, unwar

ranted on the record, in fact and in law.

Because plaintiffs have not shown a violation of their

constitutional rights, the complaint must be dismissed.

(s ) B ailey A ldrich

B ailey A ldrich

U. 8. Circuit Judge

(s ) A nthony J ulian

A nthony J ulian

U. 8. District Judge

(s) W . A rthur Garrity, J r.

W . A rthur Garrity, J r .

U. 8. District Judge

8 For what it is worth we might note that plaintiffs were not

automatically proceeded against for disturbing the peace, but

were first requested to remove the table, and were given fair

warning when they persisted, before the police were called.

10a

Judgment of the United States District Court

For the District of Massachusetts

[Caption Omitted]

Before A ldbich, Circuit Judge, and J ulian and G arrity,

District Judges.

ORDER OF DISMISSAL

December 31, 1969

In accordance with the Opinion, handed down on Decem

ber 23, 1969, it is

Ordered:

That the Preliminary Injunction, entered in the above-

entitled action on September 15, 1969 be, and it hereby

is, dissolved.

I t I s F urther Ordered that said Complaint be, and it

hereby is, dismissed.

(s) B ailey A ldrich

B ailey A ldrich

U. 8. Circuit Judge

(s) A nthony J ulian

A nthony J ulian

U. S. District Judge

(s) W . A rthur Garrity, J r .

W . A rthur Garrity, J r .

U. S. District Judge