Johnson v. United States Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Military Appeals

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson v. United States Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Military Appeals, 1987. f5c96e14-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4874a063-9028-41ce-b250-f93525f16f99/johnson-v-united-states-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-military-appeals. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

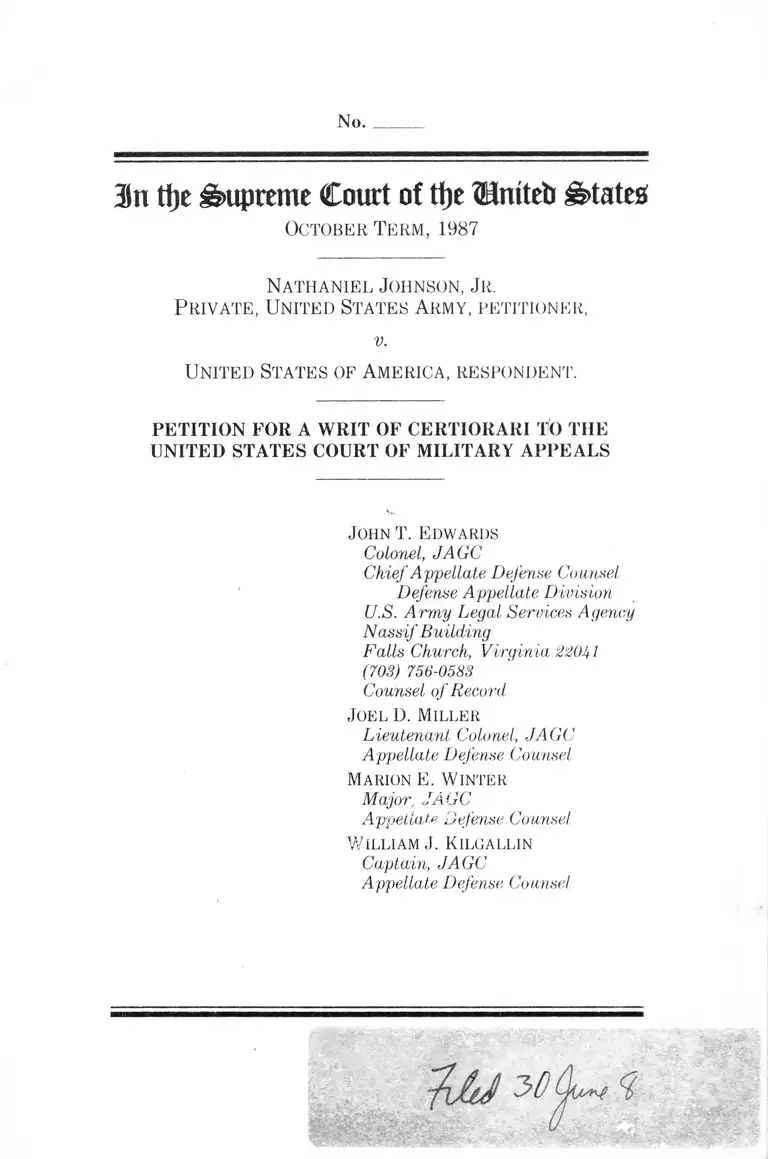

No. _

in t\)t Supreme Court of tfje Bmteb £§>tate$

October Term , 1987

Nathaniel Johnson, J r.

P rivate, United States Army, petitioner,

V.

United States of America, respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF MILITARY APPEALS

John T. Edwards

Colonel, JAGC

Chief Appellate Defense Counsel

Defense Appellate Division

U.S. Arm y Legal Services Agency

N assif Building

Falls Church, Virginia 22041

(70S) 756-0583

Counsel of Record

Joel D. Miller

Lieutenant Colonel, JAGC

Appellate Defense Counsel

Marion E. Winter

Major, JAGC

Appellate Defense Counsel

William J. Kilgallin

Captain, JAGC

Appellate Defense Counsel

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the provisions of Articles 16(1)(A) and 52(a)(2) of the

Uniform Code of Military Justice violate the Due Process

Clause of the Fifth Amendment by failing to require a

unanimous verdict from a court-martial of at least six

members.

(I)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions below .............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction . ................................................................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved . . . 2

Statement of the C ase .................................................... 2

Reasons for Granting the W rit..................................... 3

I. PETITIONER HAS STANDING TO CLAIM

THAT THE PROVISIONS OF ARTICLE

52(a)(2), UCMJ, VIOLATE HIS DUE PROC

ESS RIGHTS .................................................. 4

II. THE PROVISIONS OF ARTICLE 16(1)(A)

AND 53(a)(2), UCJM, VIOLATE THE DUE

PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE FIFTH

AMENDMENT BY FAILING TO RE

QUIRE A UNANIMOUS VERDICT FROM

A COURT-MARTIAL OF AT LEAST SIX

M EM BERS........ ............. 5

Conclusion ....................................................................... 15

Appendix A .................................................................... l a

Appendix B .................................................................... 2a

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68 (1985).................... 6, 8, 14

Apodoca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404 (1972).............. 11

Ballewv. Georgia, 435 U.S. 223 (1978)............ 6, 8, 9, 11

Burch v. Louisiana, 441 U.S. 130 (1978)........ 6, 8, 9, 11

Burns v. Wilson, 346 U.S. 137 (1953)................... 11

Courtney v. Williams, 1 M.J. 267 (CMA 1976) . . . 11

Gosa v. Mayden, 413 U.S. 665 (1973)................... 12

Johnson v. Louisiana, 406 U.S. 356 (1972).......... 11

McKeiver v. Pennsylvania, 403 U.S. 528 (1971) . . 6

Medrano v. Smith, 797 F.2d 1538 (10th Cir.

1986) .................................................................... 5

(III)

IV

Cases-Continued: Page

O’Callahan v. Parker, 395 U.S. 258 (1969).......... 12

Soloriov. UnitedStates,___ U .S.____ , 167 S.Ct.

2924 (1987) ............................... .................... .. 4, 12

United States v. Cleveland, 6 M.J. 939 (ACMR

1979) ................................. 11

United States v. Clay, 1 USMCA 74, 1 CMR 74,

(1951) ................. 10

United States v. Guilford, 8 M.J. 598 (ACMR

1979) pet. denied 8 M.J. 242 (CMA 1980) . . . . . . 12

United States v. Lamela, 7 M.J. 277 (CMA

1979) . ............... 11

United States v. McClain, 22 M.J. 124 (CMA

1986) ........................................................... 6

United States v. Wolff, 5 M.J. 923 (NCMR 1978) . 12

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970)............... 8

Constitution and Statutes:

U.S. Constitution

Amend. V (Due Process Clause)................ 4, 5, 8, 11

Amend. V I ............ ...........................................5, 8, 10

Uniform Code of Military Justice, 10 U.S.C.

§ 801 et seq

Art. 16, 10 U.S.C. 816 ............. ........................ 6, 10

Art. 25, 10 U.S.C. 825 . . . ............................... 12

Art. 51,10 U.S.C. 8 5 1 ............................. .. 4

Art. 52, 10 U.S.C. 852 . . . ............................... 4, 6, 7

Art. 60, 10 U.S.C. 860 . . . . . ................... .. 3

Art. 92, 10 U.S.C. 892 ..................................... 3

Art. 118, 10 U.S.C. 918 ........................... .. 3, 7

Miscellaneous:

Hearings on H.R. 2498 before a Subcommittee of

the Committee on Armed Services, 81st Cong.

1st Sess. (1949) .................................................... 5

V

Miscellaneous - Continued: Page

Manual for Courts-Martial, United States, 1984,

Rules for Courts-Martial (R.C.M.),

R.C.M. 9 2 1 .............................. 4

R.C.M. 922 .......................... 4

R.C.M. 1004 ...................................................... 7

Military Justice Act of 1983, Pub.L.No. 98-209,

97 Stat. 1393 ........................................................ 12

Military Rules of Evidence

Mil.R.Evid. 606 ............................................... 4

War Department Advisory Committee on Mili

tary Justice, Report of (1946)............................. 5

M tf)c Supreme Court of tf)c Unitetr g>tate£

October Term, 1987

N o ._____

Nathaniel J ohnson, J r.

P rivate, United States Army, petitioner,

V.

United States of America, respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF MILITARY APPEALS

The petitioner, Nathaniel Johnson Jr., respectfully re

quests that a writ of certiorari issue to review the judgment

and opinion of the United States Court of Military Appeals

entered in this proceeding.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Military Appeals, rendered

without oral argument, is reported at Docket No. 59,438,

___ M.J_____(C.M.A. April 4, 1988), and is reprinted at Ap

pendix A. The decision of the Army Court of Military Review

is unreported, ACMR 8700268 (A.C.M.R. Nov. 30, 1987) (un

pub.) and is reprinted at Appendix B.

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

1259(3) (Supp. IV 1986).

(1)

2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED

The Constitution of the United States provides:

Amendment V: No person . . . shall be deprived of liberty

or property, without due process of law.

Amendment VI: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused

shall enjoy the right to . . . an impartial jury.

The Uniform Code of Military Justice [hereinafter UCMJ], 10

U.S.C. § 801 et seq. (1982 and Supp. IV 1986) provides:

Article 16: The three kinds of courts-martial in each of

the armed forces are-(l) general courts-martial, con

sisting of (A) a military judge and not less than five

members.

Article 52(a)(2): No person may be convicted of any other

offense, except as provided in section 845(b) of this title

(Article 45(b)) or by the concurrence of two-thirds of the

members present at the time the vote is taken.

Article 52(b)(2): No person may be sentenced to life im

prisonment or to confinement for more than ten years,

except by the concurrence of three-fourths of the

members present at the time the vote is taken.

Statement of the Case

On December 5, 1986, petitioner was lured out of his room

on the pretense of a telephone call. Once in the hallway, the

lights were turned off and petitioner was beaten by a group

of soldiers. Petitioner subsequently returned to his room and

obtained a knife. He then returned to the hallway and con

fronted one of his attackers, Sergeant Britton. In the course

of that confrontation, Sergeant Britton was fatally stabbed

(R. 171-175). On February 4 and 5, 1987, petitioner was tried

at Fort Eustis, Virginia, before a general court-martial com

posed of officer members. Contrary to his pleas, he was found

guilty of premeditated murder (noncapital) and violation of a

lawful general regulation in contravention of Article 118 and

3

92, UCMJ, 10 U.S.C. §§ 918 and 892 (1982), respectively.

Petitioner was sentenced to a dishonorable discharge, con

finement for the rest of his natural life, forfeiture of all pay

and allowances and reduction to Private (E-l). The convening

authority approved the sentence pursuant Article 60, UCMJ,

10 U.S.C. § 860.

After voir dire and challenge of court members, the pane!

in petitioner’s court-martial consisted of five officer

members. Before trial on the merits began, petitioner’s

defense counsel objected to a court composed of only five

members. The military judge overruled the objection (R. 91).

Defense counsel subsequently requested that if the members

found petitioner guilty of premeditated murder, the military

judge should determine whether the vote on findings was

unanimous (R. 317-318). This request was also denied (R.

323). The constitutional question involved was litigated at

trial and at every stage of the appellate process. The issue

granted by the Court of Military Appeals, as a prerequisite to

this Court’s jurisdiction, was as follows:

WHETHER THE MILITARY JUDGE ERRED TO

THE SUBSTANTIAL PREJUDICE OF APPELLANT

IN PERMITTING APPELLANT TO BE TRIED FOR

PREMEDITATED MURDER BY A COURT-MARTIAL

COMPOSED OF ONLY FIVE MEMBERS AND IN

FAILING TO DETERMINE IF THE FINDINGS

WERE UNANIMOUS.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Petitioner has been condemned to spend the rest of his

natural life in confinement by a process which has been

deemed inherently suspect and constitutionally infirm for

every jurisdiction in the United States, save one. This Court

has held that a five-member jury is unconstitutional per se

and that findings of a six member jury must be unanimous.

Petitioner was convicted of premeditated murder and man-

datorily sentenced to life imprisonment by a nonunamious

five-member jury.

4

The basis upon which military courts have distinguished a

soldier’s due process protections from those afforded every

other American citizen has been vitiated by the Court’s deci

sion in Solorio v. United States, ___ U .S .____ , 107 S.Ct.

2924, 97 L.Ed.2d 364 (1987). In Solorio, the Court greatly ex

panded court-martial jurisdiction and expressly declined to

consider the issue of a due process claim since such had not

been raised at the Court of Military Appeals. 107 S.Ct. at

2933, n.18. Petitioner’s due process claim has been litigated

at every stage of trial and appeal and offers this Court the op

portunity to establish the basic parameters of minimum due

process in military criminal jurisdiction.

I.

PETITIONER HAS STANDING TO CLAIM THAT THE

PROVISIONS OF ARTICLE 52(a)(2), UCMJ, VIOLATE

HIS DUE PROCESS RIGHTS.

Article 51(a), UCMJ, 10 U.S.C. § 851(a), requires that the

members of a court-martial vote on findings by secret written

ballot. The votes are counted by the junior member and

checked by the president, who is the senior member. Article

52(a)(2), U.C.M.J., 10 U.S.C. § 852(a)(2), requires that only

two-thirds of the members need concur in order to render a

guilty verdict. See also Manual for Courts-Martial, United

States, 1984 [hereinafter M.C.M., 1984], Rules for Courts-

Martial [hereinafter R.C.M.] 921. “Except as provided in

Mil.R.Evid. [Military Rule of Evidence] 606, members may

not be questioned about their deliberations and voting.”

R.C.M. 922(e), MCM, 1984. Thus, polling of court-martial

members is prohibited. As a result, petitioner was denied the

opportunity to ascertain the numerical composition of the

verdict on findings.

The Article and Rule for Court-Martial requiring a secret

ballot, in effect, insulate Article 52(a)(2), UCMJ, from due

process scrutiny. Petitioner submits that the secret ballot

provisions were never intended to permit this result. Rather,

secret balloting was intended to shield the court-martial

members from unlawful command influence. Congress has

5

long been concerned that court-martial members may be sub

ject to unlawful command influence. See Hearings on H.R.

2498 before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed

Services, 81st Cong. 1st Sess. 628, 640-641, 825-26, and 1075

(1949); Report of War Department Advisory Committee on

Military Justice, 6-7 (1946) (committee investigated com

mander’s control of courts-martial during World War II and

concluded that it was necessary to limit commanders’ in

fluence of court-martial members). Legislation designed to

protect court-martial members from unlawful command con

trol should not now be allowed to deny petitioner an oppor

tunity to litigate a question of fundamental due process.

Petitioner should not be denied standing because the

numerical composition of the verdict was not preserved for

appeal. This is especially true since petitioner made a timely

motion to determine whether the verdict was in fact

unanimous. Accordingly, this Court should presume that

petitioner’s verdict was less than unanimous and that peti

tioner suffered prejudice. Cf Mendrano v. Smith, 797 F.2d

1538, 1540 n .l (10th Cir. 1986) (“Since, as required by the

Uniform Code of Military Justice the court-martial voted by

secret ballot, our record does not reveal the number of votes

for conviction. However, we consider the two-thirds rule’s

validity because it did apply to this trial and assume only two-

thirds, or four members of the court-martial voted for convic

tion”).

II.

THE PROVISIONS OF ARTICLES 16(1)(A) AND 52(a)(2),

UCMJ VIOLATE THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE

FIFTH AMENDMENT BY FAILING TO PROVIDE A

UNANIMOUS VERDICT FROM A COURT-MARTIAL OF

AT LEAST SIX MEMBERS.

A. Minimum Due Process Requires a Unanimous Verdict

of at Least Six Members.

The Due Process Clause requires a unanimous verdict of a

six member fact-finding body in any non-petty criminal pros

6

ecution. In Burch v. Louisiana, 441 U.S. 130 (1979), the

Court held that a less than unanimous verdict from a six-

member jury was unfair and unconstitutional.' Citing Ballew

v. Georgia, 435 U.S. 223 (1978) (five-member jury is un

constitutional per se). In Ballew, the Court stressed that at

“some point, [the] decline in jury size leads to inaccurate fact

finding and the incorrect application of the common sense of

the community to the facts .’’Ballew, 435 U.S. at 232. Accord

ingly convictions, where unanimity is not required of fact

finding bodies composed of six or fewer members, are unfair

and violate due process.

In Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 79 (1985), the Court

reasoned, “[t]he State’s interest in prevailing at trial-unlike

that of a private litigant—is necessarily tempered by its in

terest in the fair and accurate adjudication of criminal cases.”

The same compelling interest in ensuring accurate findings

of fact applies to the parties in courts-martial.

B. Due Process in the M ilitary Context Does N ot Justify

Less Than a Unanimous Six Member Verdict.

Courts-martial have not been subject to the jury trial

demands of the Constitution. United States v. McClain, 22

M.J. 124, 128 (C.M.A. 1986). The Due Process Clause never

theless requires that criminal trial procedures foster accurate

fact-finding and fundamental fairness. See McKeiver v. Penn

sylvania, 403 U.S. 528, 543 (1971). Military members accused

of crimes and the Government of the United States share a

compelling interest in the accurate disposition of criminal

charges. Cf Ake v Oklahoma, 470 U.S. at 79.

To facilitate fact-finding at general courts-martial, Con

gress has provided that such courts, designed to dispose of

non-petty offenses, consist of “not less than five members.”

Art. 16(1)(A), UCMJ, 10 U.S.C. § 816(1)(A). In a noncapital

case, only two-thirds of such members need concur in a find

ing of guilty. Art. 52(a)(2), UCMJ, 10 U.S.C. § 852(a)(2). On

the other hand, both Congress and the President have re

quired a higher standard for findings in capital cases. When

the death penalty is mandatory, the findings of “not less than

7

five members” must be unanimous. Art. 52(a)(1), UCMJ, 10

U.S.C. § 852(a)(1). The President, acting under statutory

authority, has recently provided that the non-mandatory im

position of the death penalty may be considered only after the

entry of unanimous findings. R.C.M. 1004(a)(2), MCM, 198J,h1

Neither Congress nor the President has required unanimous

findings for noncapital premeditated or felony murder, the

two findings for which Congress has nonetheless required the

mandatory imposition of life imprisonment. Art. 118, UCMJ,

10 U.S.C. § 918. Accordingly, while the less stringent,

nonunanimous findings of five members prevents the death

penalty from being imposed on petitioner, such non

unanimous findings nevertheless provide the basis for imposi

tion of a mandatory sentence to confinement for life.

The Congressional and Presidential procedures for find

ings and sentence at courts-martial recognize, at least for im

position of the death penalty, the well-established due process

concept that the procedural protection afforded depends to a

large extent upon the interests at stake.2 They fail to

acknowledge, however, the compelling interest of both peti

tioner and the United States that no accused, including peti

tioner, be found guilty of an infamous crime and be deprived

of his liberty for the rest of his life on the basis of unreliable

findings.3 Thus, the deliberative process of petitioner’s court-

martial must be scrutinized under the test adopted to resolve

criminal due process concerns. The test balances three fac

tors.

The first is the private interest that will be affected by

the action of the State. The second is the governmental

1 This provisions became effective in February 1986. App. 21, R.C.M.

1004(aX2), MCM, 1984.

2 Congress also partially applies this concept by requiring a three-fourths

rather than a two-thirds vote of the members for any sentence to confine

ment in excess of ten years. Art. 52(b)(2), UCMJ, 10 U.S.C. § 852(b)(2). The

only exception to this rule is where mandatory life imprisonment is the

minimum punishment.

3 The court members are not instructed and may not consider that a ver

dict of guilty to premeditated murder automatically results in a sentence to

life imprisonment in a noncapital case.

8

interest that will be affected if the safeguard is to be pro

vided. The third is the probable value of the additional or

substitute procedural safeguards that are sought, and the

risk of an erroneous deprivation of the affected interest if

those safeguards are not provided.

Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. at 77.

Petitioner’s private interest in the accuracy of the findings

at trial, which placed his life and liberty at risk, is “uniquely

compelling.” Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. at 78. Such an in

terest weighs heavily in the balancing analysis. Id.

To weigh the second and third factors, it must be deter

mined what additional or substitute procedural safeguards

petitioner seeks. Petitioner objected to a court-martial of less

than six members (R. 91). Petitioner relied, inter alia, on the

sixth and fourteenth amendment holdings in Ballew and

Burch that five-person as well as nonunanimous six-person

juries may not constitutionally convict a defendant for a non-

petty criminal offense. Petitioner also relied on the Due Proc

ess Clause and the holdings of Ballew and Burch to the extent

they are predicated upon due process concerns as well as

sixth amendment considerations (R. 91).

A fact-finding body of only five persons, whether composed

of private citizens or soldiers, produces results so unreliable

as a matter of law that the Due Process Clause is violated.

The Court reached this conclusion in Ballew based upon em

pirical data compiled after its decision in Williams v. Florida,

339 U.S. 78 (1970), upholding the use of a six-person jury.

Ballew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. at 239. Relying on this data, the

Court reached specific findings that:

[Progressively smaller juries are less likely to foster ef

fective group deliberation. At some point, this decline

leads to inaccurate factfinding. The risk of convicting an

innocent person . . . rises as the size of the jury

diminishes . . . . [T]he verdicts of jury deliberation in

criminal cases will vary as juries become smaller, and . . .

9

the variance amounts to an imbalance to the detriment of

one side, the defense . . . . [T]he presence of minority

viewpoints [diminishes] as juries decrease in size. When

the case is close, and the guilt or innocence of the defend

ant is not readily apparent [larger juries] will insure

evaluation by the sense of the community and will also

tend to insure accurate factfinding.

Ballew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. at 232-38. The evidence indicates

that as the size of juries diminishes to five and below, the risk

of conviction of innocent defendants increases. 435 U.S. at

234-35. Unanimity of five-person juries does not remedy the

sixth amendment infirmities. A unanimous five-person jury

cannot assure that the group engages in meaningful delibera

tion and truly represents the sense of the entire community.

435 U.S. at 241. Savings in time and money do not justify the

State’s interest in five-person juries. 435 U.S. at 243-44.

The Court relied on the same rationale in Burch:

[M]uch the same reasons that led us in Ballew to decide

that use of a five-member jury threatened the fairness of

the proceeding and the proper role of the jury, lead us to

conclude now that conviction for a non-petty offense by

only five members of a six-person jury presents a similar

threat to preservation of the substance of the jury trial

guarantee and justifies our requiring verdicts rendered

by six-person juries to be unanimous.

Burch v. Louisiana, 441 U.S. at 138. Once again, the Court

rejected the S tate’s justification that the use of

nonunanimous six-person juries saved time and money. 441

U.S. at 139.

In the case sub judice, the military judge articulated the

following justification for his ruling:

[T]he objection is denied based on the fact that the

Manual permits the five member court that is the

minimum number in a General Court-Martial, of course

10

such as we have today. In my opinion, this is not constitu

tionally impermissible.

(R. 92). This ruling ignores the specific language of Article

16, UCMJ, 10 U.S.C. § 816, one basis for due process in

military courts. Further, it ignores the empirical data relied

on in Ballew.

First, the jurisdictional requirement of Article 16, UCMJ,

is for “not less than five members.” Nothing in that language

evidences a Congressional intent that there shall be no more

than five members assembled as a general court-martial.

Therefore, the statute in no way prohibited the military

judge, in safeguarding fundamental fairness, from ordering

the detail of additional members to assure accurate fact

finding where appellant was on trial for an infamous offense

which mandates the loss of his liberty for the rest of his life.

Second, the provisions of the UCMJ do not alone define due

process for courts-martial.

Generally speaking, due process means a course of legal

proceedings according to those rules and principles

which have been established in our system of

jurisprudence for the enforcement and protection of

private rights. For our purposes, and in keeping with the

principles of military justice developed over the years, we

do not bottom those rights and privileges on the Con

stitution. We base them on the laws as enacted by Con

gress. But, this does not mean that we can not give the

same legal effect to the rights granted by Congress to

military personnel as do civilian courts to those granted

to civilians by the Constitution or by other federal

statutes.

United States v. day , 1 USCMA 74, 1 CMR 74, 77 (1951). Ac

cordingly, even though petitioner may have no sixth amend

ment entitlement to trial by jury,4 the requisites of

4 Petitioner asserts that all United States citizens are entitled to the ex

plicit protections of the Bill of Rights, and his status as a soldier does not

deprive him of the right to a jury “in all criminal prosecutions.” It is clear

that only the right to grand jury indictment is expressly denied to soldiers

1 1

due process for civilian trials give meaningful definition to

the protections to be afforded petitioner. The Due Process

Clause has always applied to court-martial procedure. Burns

v. Wilson, 346 U.S. 137, 142-43 (1953). Further, the Court of

Military Appeals has adopted the requirement that a party

who urges a different rule than the one prevailing in the

civilian community bears the burden of demonstrating that

unique military conditions dictate the rule. Courtney v.

Williams, 1 M.J. 267, 270 (CMA 1976).

Petitioner was entitled to evaluation of the facts by that

sense of the community which would tend to insure accurate

fact-finding. SeeBallew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. at 238. Unanimi

ty of six-person juries is required to ensure that a sense of the

community stands between the zealous prosecutor or biased

judge. Burch v. Louisiana, 441 U.S. at 135-37. In the

military, there is even a greater need for procedural

safeguards to stand against the zealous or biased military

commander. Verdicts based on votes of 10-2, 9-3 and 6-0 are

sufficient to serve this function. See generally Apodoca v.

Oregon, 406 U.S. 404 (1972); Johnson v. Louisiana, 406 U.S.

356 (1972). Those based on votes of 4-1 or 4-2 are not. Burch

v. Louisiana, 441 U.S. at 135-37.

The Army Court of Military Review has long considered

the reasoning of this Court as enunciated in Ballew and

Burch inapposite to trial by courts-martial. That court had

relied on the very restrictive nature of court-martial jurisdic

tion to remedy the constitutional infirmities of courts-

martial:

It cannot be gainsaid that the military trial must be fair

and impartial. See e.g., United States v. Lamela, . . . 7

M.J. [277] at 278: United States v. Cleveland, 6 M.J. 939,

942 (A.C.M.R. 1979). The trial is, however, by a unique,

military tribunal that is essentially different from the

jury envisioned by the Sixth Amendment. The composi

tion of courts-martial is different, as the members are

“when in actual service in time of war or public danger.’’ U.S. Const,

amend. V. An American soldier is neither an indentured servant nor a

second-class citizen.

12

drawn exclusively from the accused’s own profession

based on specified qualifications (one of which is judicial

temperament), with specialized knowledge of the profes

sion, and subject to only one challenge other than for

cause. Their functioning differs, too. For example, it in

cludes the questioning of witnesses and the determining

of sentences. In view of such compositional and func

tional differences, the studies relied upon in Ballew and

Burch are inapposite. United States v. Wolff, . . . 5 M.J.

[923] at 925. The differences between the institution of

courts-martial and the institution known as a jury have

been recognized as necessary as well as constitutional.

O’Callahan v. Parker, 395 U.S. 258, 89 S.Ct. 1683, 23

L.Ed.2d 291 (1969). When the use of courts-martial has

impinged on constitutional rights, the remedy has been to

limit the exercise of their jurisdiction rather than to alter

the nature of the tribunal, for courts-martial are not fun

damentally unfair. Gosa v. Mayden, 413 U.S. 665, 93

S.Ct. 2926, 37 L.Ed.2d 873 (1973).

United States v. Guilford, 8 M.J. 598, 602 (ACMR 1979), pet.

denied, 8 M.J. 242 (CMA 1980). The bedrock of this legal

reasoning has been rendered fatally flawed by this Court’s

decision in Solorio, 107 S.Ct. 2924, which expressly abandons

any limitation on military jurisdiction over soldiers as set out

in O’Callahan v. Parker,5

Further, while there is a compositional and functional dif

ference between military jurors and their civilian counter

parts, such does not excuse a denial of due process protec

tions. Article 25, UCMJ, 10 U.S.C. § 825 requires convening

authorities to appoint court members who are best qualified

by reason of age, education, training, experience, length of

service and judicial temperament. Rather than excuse

nonunanimous verdicts, the extraordinary composition of

military juries demands that anything less than a unanimous

5 Congress’ decision to place military tribunals directly under Supreme

Court scrutiny also evidences a congressional desire that military courts

parallel civilian courts unless military necessity dictates the contrary. See

Military Justice Act of 1983, Pub. L. No. 98-209, 97 Stat. 1393.

13

six-member verdict be considered unreliable per .sc, since the

opinion of one such “blue ribbon” military fact-finder must be

given substantially more credence than the dissenting opinion

of one civilian juror.

The size of a five-member court-martial alone renders

group deliberation less effective. The risk of an erroneous

conviction is still greater by virtue of the small size of the

group. The variance in results still amounts to an imbalance

to the detriment of the defense solely as a result of the

group’s small size. Five members do not adequately represent,

minority viewpoints; in close cases, five members do not pro

vide the requisite sense of the community necessary to pro

duce reliable results. Moreover, small groups of five members

in the military are more easily subjected to the subtle

pressures of unlawful command influence.

In addition to the safeguards found in the members’ ability

to ask questions and take notes, soldiers are entitled to the

due process protection inherent in the requirements that

courts-martial be composed of at least six members and that

all six-member findings be unanimous.6 A requirement of

unanimity has the value of producing more accurate findings,

as both Congress and the President have clearly acknowl

edged by their requirements of unanimity in capital cases.

Petitioner specifically seeks this requirement of unanimity

of six members in at least all cases where confinement for life

is mandatory upon a finding of guilty. No accused should be

deprived of his liberty for life based upon findings which may

be erroneous or generated by known infirmities. The pro

cedural safeguards of assembling more than five members

and requiring unanimity on findings are therefore absolutely

essential.

Government interests are not adversely affected if these

safeguards are provided. First, the appointment of a suffi

cient number of members in premeditated and felony murder

cases to ensure the assembly of more than five members

6 The assembling of seven or more members, even without a requirement

for unanimity in findings, would also satisfy constitutional concerns.

14

burdens the government little in terms of time or money. The

assembly of six or more members is a common occurrence in

courts-martial practice. General court-martial convening

authorities have sufficient members within their jurisdiction

from which to appoint court-martial members. Second, the

government shares the same compelling interest of all

military accused in producing accurate findings. Ake v.

Oklahoma, 470 U.S. at 79. The government has no legitimate

interest in the mandatory imposition of a sentence to life con

finement against an accused who has been found guilty and

sentenced to life imprisonment by an inherently suspect

court-martial panel.

f )

CONCLUSION

The military’s mission of defending this country is without

a doubt a most compelling state interest. Petitioner’s interest

in receiving a fair trial resulting in accurate findings of fact is

equally compelling. There has been no showing that com

pliance with the basic due process rights expressed in Burch

will in anyway harm the national defense. The perception of

fairness and accurate verdicts can only enhance the morale

and effectiveness of men and women in our Armed Forces.

Thus, the two interests are neither inconsistent nor mutually

exclusive and can coexist to promote an effective fighting

force while maintaining the constitutional rights of its

soldiers. Anything less than a minimum requirement for

unanimous six-member verdicts clearly thwarts constitu

tional due process and fundamental fairness. In the absence

of a clear and compelling national interest requiring other

wise, soldiers are entitled to the same accuracy from fact

finders in criminal trials as are all other citizens of the United

States.

Respectfully Submitted,

J ohn T. E dwards

Colonel, JACK'

Chief A ppellale Defense Counsel

Defense A p pel lute Division

U.S. Arm y Legal Services Agency

Nassif Building

Falls Church, Virginia 22051

(7OK) 756-058.1

Counsel of Record

J o el I). Mil l e r

Lieutenant Colonel, JAGC

Appellate Defense Counsel

Marion E. W in ter

Major, JAGC

Appellate Defense Counsel

W illiam J. Kilo allin

Captain, JAGC

Appellate Defense (Counsel

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A

UNITED STATES COURT OF MILITARY APPEALS

USCMA Dkt. No. 59438/AR

CMR Dkt. No. 8700268

United States, appellee

v.

Nathaniel Johnson, J r. (214-72-8044), appellant

ORDER

On consideration of the petition for grant of review of the

decision of the United States Army Court of Military Review,

we concluded that appellant’s court-martial was convened

and conducted in accordance with the Uniform Code of

Military Justice. Accordingly, it is by the Court, this 4th day

of April, 1988

ORDERED:

That said petition for review is granted on the issue raised

by appellate defense counsel; and

That the decision of the United States Army Court of

Military Review is affirmed.

For the Court,

Isl J ohn A. Ch its , III

Deputy Clerk of the Court

cc: The Judge Advocate General of the Army

Appellate Defense Counsel (KILGALLIN)

Appellate Government Counsel (HAUSKEN)

(la)

2a

APPENDIX B

UNITED STATES ARMY COURT OF

MILITARY REVIEW

ACMR 8700268

United States, appellee

V.

P rvate E-2 Nathaniel J ohnson, J r. (214-72-8044),

United States Army, appellant

United States Army

Transportation Center and Fort Eustis

J. R. HOWELL, Military Judge

For Appellant: Lieutenant Colonel Joel D. Miller, JAGC,

Major Marion E. Winter, JAGC, Captain William J. Kilgallin,

JAGC (on brief).

For Appellee: Colonel Norman G. Cooper, JAGC, Lieutenant

Colonel Gary F. Roberson, JAGC, Captain Gary L. Hausken,

JAGC (on brief).

30 November 1987

DECISION

Before

DeFORD, Kane, and Smith

Appellate Military Judges

Per Curiam:

On consideration of the entire record, including considera

tion of the issue personally specified by appellant, we hold the

findings of guilty and the sentence as approved by the con

vening authority correct in law and fact. Accordingly, those

findings of guilty and the sentence are AFFIRMED.

FOR THE COURT:

I si William S. F ulton, J r.

WILLIAM S. FULTON, JR.

Clerk of Court

U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1988-214-291/62026

R E P L Y T O

A T T E N T I O N O F

U N I T E D S T A T E S A R M Y L E G A L S E R V I C E S A G E N C Y

N A S S I F B U I L D I N G

F A L L S C H U R C H . V I R G I N I A 2 2 0 4 1 5 0 1 3

D E P A R T M E N T O F T H E A R M Y

June 6, 1988

,p

Defense Appellate

Division

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

ATTN: Mr. Steve Ralston

99 Hudson St.

New York, New York, 10013

Dear Mr. Ralston:

I am one of the appellate attorneys assigned to represent

Private Nathaniel Johnson. I believe this is an appropriate

case for an amicus curiae pleading from the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund. As the“enclosed pleading sets out, Johnson was

tried and convicted of murder by a five-member military jury.

We believe that in light of the Supreme Court decision in

Solorio v. United States. __ JJ.S.___ 107 S.Ct. 2924, 97 L.Ed

2d 364 (1987), the issue of minimum military due process must

now be addressed by the Court.

If you are interested in pursuing this case as an amicus

curiae. I will be pleased to offer any assistance I can.

Thank you for your consideration of this matter.

Sincerely

t .a p ta ± ii ,

Appellate Defense Counsel

(202) 756-0572

WJK:mj j