Richmond v JA Croson Company Amici Curiae in Support of Appellant

Public Court Documents

April 21, 1988

42 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Richmond v JA Croson Company Amici Curiae in Support of Appellant, 1988. a45a9d37-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/48cc60ab-d466-4c4b-b165-bade1cb2a987/richmond-v-ja-croson-company-amici-curiae-in-support-of-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

£>

y '

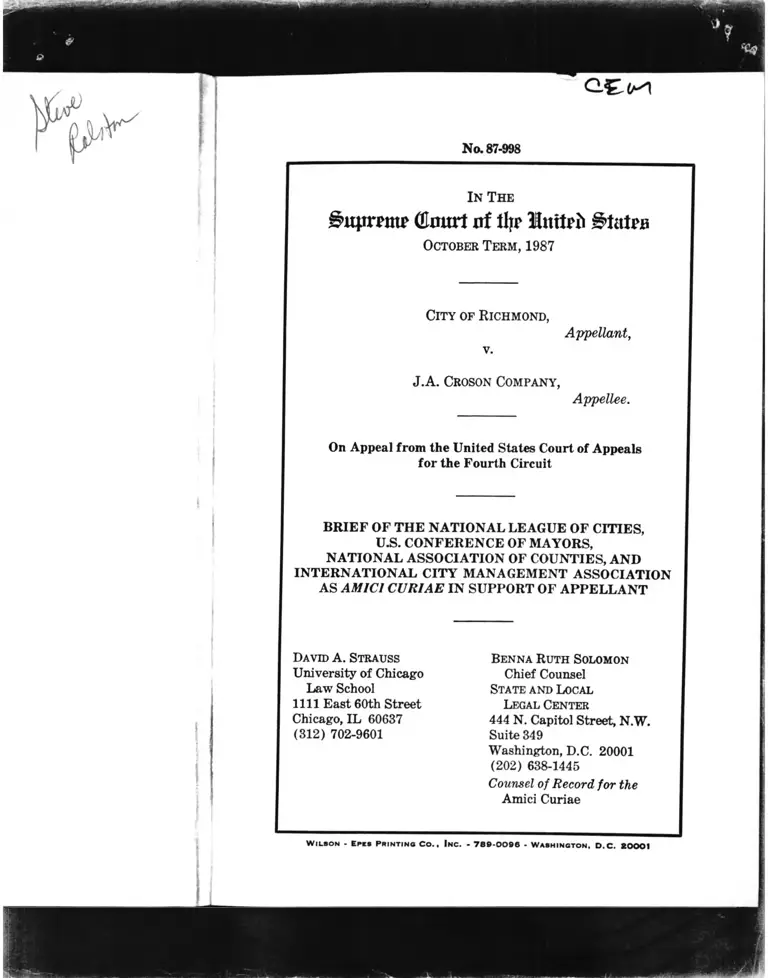

N o. 87-998

In The

( t a r t nf tlyr U n it?h §>U\Ub

October Term, 1987

City of Richmond,

Appellant,

v.

J.A. Croson Company,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL LEAGUE OF CITIES,

U.S. CONFERENCE OF MAYORS,

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF COUNTIES, AND

INTERNATIONAL CITY MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT

David A. Strauss

University of Chicago

Law School

1111 East 60th Street

Chicago, IL 60637

(312) 702-9601

Benna Ruth Solomon

Chief Counsel

State and Local

Legal Center

444 N. Capitol Street, N.W.

Suite 349

Washington, D.C. 20001

(202) 638-1445

Counsel of Record for the

Amici Curiae

W ilso n - Epeb P r in t in g C o . , In c . - 7 86 -O O B 6 - W a s h in g t o n , D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the Equal Protection Clause prohibits the

City of Richmond from remedying the effects of racial

discrimination on minority participation in city construc

tion contracts by enacting a temporary program that,

subject to a waiver provision, requires contractors to

subcontract a portion of their contracts to minority busi

ness enterprises.

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTION PRESENTED................................................ i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...................................... iv

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CU RIAE ......................... 1

STATEMENT...................................................................... 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.......................................... 5

ARGUMENT.............. ............ ............................................ 7

RICHMOND’S MINORITY BUSINESS UTILIZA

TION PLAN DOES NOT VIOLATE THE EQUAL

PROTECTION CLAUSE................................ 7

A. The Court Of Appeals’ Decision Is Inconsistent

With Fullilove v. Klutznick.................................. 7

B. The Richmond Plan Promotes Compelling Gov

ernment Interests And Does Not Impose Unfair

Burdens On Nonminority Contractors. ................. 14

1. The Richmond Plan promotes the compelling

interest of remedying racial discrimination in

the construction industry................................. 14

2. Richmond may enact a race-conscious remedy

for prior discrimination in the local construc

tion industry without admitting complicity in

racial discrimination......................................... 23

3. Richmond’s plan does not unfairly burden

nonminority contractors. ................................. 28

CONCLUSION ................................................................... 30

Appendix I

Minority Business Enterprise Programs of State

Governments............................................................ la

Appendix II

Minority Business Enterprise Programs of Mu

nicipal and County Governments ........................... 14a

(iii)

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Andrus v. Allard, 444 U.S. 51 (1979) .............................. 29

Associated General Contractors v. City and County of

San Francisco, 813 F.2d 922 (9th Cir. 1987), petition

for rehearing pending ................................................... 10

Board of Directors v. Rotary Club, 107 S.Ct. 1940

(1987) .............................................................................. 23,24

Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574

(1983) .............................................................................. 23-24

Byrd v. Local No. 24, IBEW, 375 F. Supp. 545 (D. Md.

1974) ................................................................................ 25

City of Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc., 475 U.S. 41

(1986) ............................................................................. 19,20

Ethridge v. Rhodes, 268 F. Supp. 83 (S.D. Ohio 1967).... 25

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. (10 Otto) 339 (1880) ....... 11

FERC v. Mississippi, 456 U.S. 742 (1982) ................. 10

Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S.

561 (1984) ....................................................................... 28

Franks v. Boivman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976) ............................................................................. 28,29

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980) ....................passim

Fumco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U S 567

(1978) ............................................................................. 17

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ..... 23

Hughes v. Alexandria Scrap Corp., 426 U S 794

(1976) ............................................................................. 24

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977)......................................16, 17,18

James v. Ogilvie, 310 F. Supp. 661 (N.D. 111. 1970) ..... ’ ’ 25

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, 107 S.Ct. 1442

(1987> .................................................................... 13, 16, 18, 28

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ................. 11

Local No. 93, Firefighters v. Cleveland, 478 U S 501

(1986) ............................................................................. 2g

Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC, 106 S. Ct.

3019 (1986) ................................................ 25 28

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) ..................... ’ ’ 25

v

Page

National Black Police Association v. Velde, 712 F.2d

569 (D.C. Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 466 U.S. 963

(1984) ............................... 25

North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann, 402

U.S. 43 (1971).............................................................23,25,26

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973) ................... 25

Percy v. Brennan, 384 F. Supp. 800 (S.D.N.Y. 1977).... 25

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88 (1945).. 24

Reeves, Inc. v. Stake, 447 U.S. 429 (1980)...................... 24

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265 (1978) ................. 11,27,28

Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609 (1984).. 24

Robins Dry Dock & Repair Co. v. Flint, 275 U.S. 303

(1927) ..................................... 29

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) ......................... 24

Schlesinger v. Reservists Committee to Stop the War,

418 U.S. 208 (1974) ............................. 21

Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979) ............. 16, 18,28

Swann v. Cliarlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............................................................ 25-26

The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36

(1872) .............................................................................. 11

United States v. Paradise, 107 S.Ct. 1053 (1987) .....14, 25, 28

White v. Massachusetts Council of Construction Em

ployers, 460 U.S. 204 (1983) ....................................... 24

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 476 U.S. 267

(1986) .............................................................................. passim

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS:

U.S. Const. Amend V, Due Process Clause...... ..... 7

U.S. Const. Amend. XIV

Equal Protection Clause .................................. 7

Section 5 .................................................... 10-11, 12,13

Public Works Employment Act of 1977, Section

1 03 (f)(2 ), 42 U.S.C. 6705(f)(2 ) ............ 7 ,8,9,10,12

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

CON GRESSIONAL MATERIALS: Page

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2768 (1866) ..... 11

BOOKS:

H. Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amend

ment (1965) ............................................................ 11

J. Gillies & F. Mittelbach, Management in the

Light Construction Industry (1962) ................... 18

R. Glover, Minority Enterprise in Construction

(1977) ...................................................................... 18

R. Harris, The Quest for Equality (1960) ............... n

J. tenBroek, The Antislavery Origins of the Four

teenth Amendment (1951) .............................. H

In T he

§ u p m n r (Em trt n f tljr llu ttrii S ta irs

October T erm, 1987

No. 87-998

City of Richmond,

v Appellant,

J.A. Croson Company,

_________ Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL LEAGUE OF CITIES,

U.S. CONFERENCE OF MAYORS,

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF COUNTIES, AND

INTERNATIONAL CITY MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT

INTEREST OF THE AM ICI CURIAE

The amici, organizations whose members include mu

nicipal and county governments and officials throughout

the United States, have a strong interest in legal issues

that affect state and local governments. This case con

cerns the constitutionality of a temporary minority sub

contracting program adopted by the City of Richmond,

Virginia. The program provides that any firm awarded

a construction contract by the City shall, unless it re

ceives a waiver, subcontract 30% of the value of the

contract to minority business enterprises.

This is a case of great importance to the amid. Pro

grams comparable to Richmond’s are very common

among state and local governments. After the Court

noted probable jurisdiction in this case, we undertook

a survey of state, municipal, and county governments;

the results are reproduced in the appendices to this brief.

The survey identifies 36 States and 190 local govern

ments throughout the Nation that have adopted programs

that use a variety of devices, including numerical goals

or targets, to expand minority access to government con

tracts. The vast majority of these programs were adopted

after this Court’s decision in Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448

U.S. 448 (1980), which upheld a similar program enacted

by Congress. Many of the programs, including Rich

mond’s, were modeled on the federal program upheld in

Fullilove. As we explain below (pages 7-10), the decision

of the court of appeals in this case imposes more strin

gent requirements on state and local governments than

Fullilove imposed on the federal government. Many state

and local programs, therefore, would be jeopardized by

the approach taken by the court of appeals, if it were to

prevail.

These efforts by state and local governments represent

a practical and constructive attempt to deal with the

effects of discrimination at the level of government where

such problems are best addressed. Because amici believe

that it is exceptionally important that those efforts not

be jeopardized, we offer this brief to assist the Court in

its resolution of this case.1

STATEMENT

1. In April 1983, the Richmond City Council adopted

a Minority Business Utilization Plan. The Plan provides

that a contractor who is awarded a construction contract

by the City shall, unless granted a waiver, subcontract

at least 30% of the value of the contract to minority

business enterprises (MBEs).2 J.S. App. 2a. The City

will grant a waiver if a “ sufficient [number of] . . .

1 The parties’ letters of consent to the filing of this brief have

been lodged with the Clerk.

2 The Plan contains a detailed definition of which businesses

qualify as minority business enterprises. These provisions require

that the firm be owned by members of minority groups and that it

be either controlled or operated by minority group members. See

J.S. Supp. App. 115-116, 251-252. A general contractor that is

itself a minority business enterprise need not subcontract 30% of

its contract to other MBEs. Id. at 247. The Plan requires the City

to verify that an enterprise claiming to be an MBE is not a sham.

See id. at 62.

. 2 3

qualified [MBEs] . . . are unavailable or are unwilling

to participate in the contract.” J.S. Supp. App. 67-68.

The Plan is explicitly “ remedial” (id. at 248) and tem

porary; it expires at the end of June 1988 (ibid.).

The City ̂Council adopted the Plan after holding a

hearing during which it received testimony and informa

tion about the history of public construction contracting

in Richmond. The Council learned that during the pre

ceding five years, only two-thirds of 1% of the dollar

value of construction contracts awarded by Richmond

was awarded to MBEs. J.S. Supp. App. 38, 115. The

population of Richmond is approximately 50% minority.

Ibid. The City Manager and a member of the City

Council stated, on the basis of their experience, that

there was widespread discrimination in the construction

industry in general and in Richmond in particular; op

ponents of the Plan within the Council, and representa

tives of contracting associations who spoke at the hear

ing, did not dispute these statements. Id. at 38, 164-165.

2. In September 1983, the City invited bids on a proj

ect that involved the installation of certain plumbing

fixtures in the City Jail. Appellee was the only bidder.

After the bidding was closed, appellee sought a waiver

of the requirement that it subcontract with an MBE.

J.S. App. 2a-3a; J.S. Supp. App. 120-124. The City

declined to grant the waiver and, when appellee sought

to increase the price of its contract with the City, the

City reopened the bidding on the contract. The City

invited appellee to submit a new bid. J.S. App. 3a.

Instead, appellee brought this action, which was re

moved to the United States District Court for the East

ern District of Virginia. Appellee sought injunctive and

declaratory relief and damages, claiming, among other

things, that the Plan violated its rights under the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The

district court rejected appellee’s claims (J.S. Supp. App.

110-232), and the court of appeals affirmed (id. at 1-

109). This Court granted appellee’s petition for a writ

of certiorari, vacated the judgment of the court of ap

4

peals, and remanded the case for reconsideration in light

of Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 476 U.S. 267

(1986). See 106 S.Ct. 3327 (1986).

3. On remand, a divided court of appeals reversed the

judgment of the district court and held the Plan uncon

stitutional. J.S. App. la-26a. The majority acknowl

edged that a City may use a racial preference in order

to “ redress a practice of past wrongdoing” (J.S. App.

14a). But the majority ruled that the Richmond Plan

was invalid because there was “no record of prior dis

crimination by the city” in this case. Id. at 6a. The ma

jority explained that, for example, “ [t]here has been no

showing that qualified minority contractors who sub

mitted low bids were passed over . . . [or] that minority

firms were excluded from the bidding pool.” Id. at 8a.

The majority further asserted that the statements

made during the City Council hearing were not sufficient

to support the Plan because they were “ conclusory and

“highly general” (J.S. App. 6a). The majority also

rejected as “ spurious” (id. at 8a) the City’s argument

that an inference of discrimination was raised by the

virtual absence of city contracts awarded to minorities,

even though minorities constituted half the City’s popula

tion. The majority stated that this disparity did not

“ demonstrate discrimination” because “ [t]he appropri

ate comparison is between the number of minority con

tracts and the number of minority contractors” (id. at

7a; emphasis in original).

Finally, the majority concluded that even if the Plan

were supported by the need to remedy past discrimina

tion, it would be unconstitutional because “ it is not nar

rowly tailored to that remedial goal.” J.S. App. 11a.

The majority asserted that the 30% figure was chosen

“ arbitrarily” ; that the definition of an MBE was not

narrowly tailored; that the provision for a waiver was

too “ restrictive” ; and that the temporary nature of the

plan was immaterial because “ [w]hether the . . .

[P]lan will be retired or renewed in 1988 is, at this

point, nothing more than speculation.” Id. at lla-13a.

Judge Sprouse dissented. J.S. App. 14a-26a. The

court of appeals denied rehearing en banc by a vote of

6-5. Id. at 27a-28a.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

A. The decision of the court of appeals is inconsistent

with Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980). Fulli-

love upheld a federal program that is indistinguishable

from Richmond’s Minority Business Utilization Plan in

every relevant respect. Moreover, the evidence support

ing the Richmond Plan is stronger than the evidence

adduced in Fullilove.

Fullilove cannot be distinguished on the ground that

it involved the exercise of congressional power under Sec

tion 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The basis of Con

gress’s broad Section 5 power is the concern that the

States might fail to act against discrimination. Here,

Richmond has acted to remedy discrimination. It would

be paradoxical to interpret the grant of power to Con

gress in the Fourteenth Amendment in a way that re

duces the authority of state and local governments to

remedy racial discrimination. In addition, state and lo

cal remedies for discrimination have many practical ad

vantages over remedies imposed by the more remote and

less knowledgeable federal government.

B. Although Fullilove is sufficient to dispose of this

case, the Richmond Plan also satisfies the standards pre

scribed in this Court’s other decisions concerning race

conscious measures.

1. Richmond has a strong basis for concluding that

racial discrimination in the construction industry af

fected minorities access to City contracting opportu

nities. The most compelling evidence is that minorities,

who are half of Richmond’s population, received less than

one percent of public construction contracting funds.

The court of appeals’ dismissal of that evidence is mani

festly erroneous. In addition, Richmond had nonstatis-

tical evidence of discrimination from several sources.

The court of appeals ruled that this evidence was in

adequate because the Richmond City Council did not

5

6

make a “ finding” or “ showing” that identified particular

discriminatory acts. This Court’s decisions, however,

establish that such findings are not required. In addi

tion, requiring a government to identify discriminatory

acts will inject an unnecessarily divisive and adversarial

element into the process of designing remedies for racial

discrimination.

A race-conscious remedy was a fully appropriate re

sponse to the discrimination that Richmond identified in

the construction industry. Simply requiring that firms

in the industry not discriminate would not have been

effective. Because of prior discrimination, minority firms

now lack experience; they would accordingly be at a com

petitive disadvantage even if there were no longer any

discrimination at all. An effective remedy for the ves

tiges of discrimination must provide a temporary way

to overcome that competitive disadvantage.

2. Contrary to the court of appeals, Richmond was

entitled to adopt a race-conscious remedy for discrimi

nation in the construction industry even if the City itself

did not discriminate. As this Court has often held, state

and local governments have a compelling interest of the

highest order in remedying private discrimination. That

interest is even greater when the City is attempting to

ensure that its own funds will not be spent in a way that

supports, or perpetuates the effects of, private discrimi

nation. A race-conscious measure will sometimes be the

only effective means of promoting these exceptionally im

portant government interests.

3. Richmond’s Plan does not unfairly burden non

minority contractors. To a large extent, the burdens im

posed by the Richmond Plan fall on the taxpayers. In

that respect, the Plan is superior to nearly every other

affirmative action measure that this Court has consid

ered. The burden on nonminority subcontractors who

compete with minority firms is limited and diffuse.

Moreover, the Richmond Plan does not uproot settled ex

pectations but only denies, at most, the contingent possi

bility of future economic gain.

7

ARGUMENT

RICHMOND’S MINORITY BUSINESS UTILIZATION

PLAN DOES NOT VIOLATE THE EQUAL PROTEC

TION CLAUSE.

A. The Court Of Appeals’ Decision Is Inconsistent With

Fullilove v. Klutznick.

1. In Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980), this

Court held that Section 1 0 3 (f)(2 ) of the Public Works

Employment Act of 1977, 42 U.S.C. 6 7 0 5 (f)(2 ), does

not violate the equal protection component of the Fifth

Amendment’s Due Process Clause. Section 1 0 3 (f)(2 )

provided that 10% of the funds granted under the Act

was to be used to procure services and supplies from

MBEs. The Richmond Minority Business Utilization

Plan was modeled on Section 103(f) (2 ), and it is indis

tinguishable from Section 1 0 3 (f)(2 ) in every relevant

respect. Indeed, the arguments supporting the Richmond

Plan are significantly stronger than those advanced in

support of Section 103(f) (2).

a. Section 103(f) (2) was supported by the same kind

of statistical disparity as the Richmond Plan— a dispar

ity between the percentage of minorities in the general

population and the percentage of government contract

funds received by minorities. The court below, without

referring to Fullilove, condemned as “ spurious” and “ not

. . . meaningful” the overwhelming disparity between

the percentage of minorities in Richmond’s population

and the percentage of Richmond’s public construction

contract funds that had been awarded to minorities. J.S.

App. 8a, 10a. But in Fullilove, a majority of the Mem

bers of this Court relied on precisely the same statistical

comparison to support their conclusion that Section

103(f) (2) was a permissible remedy for past discrimi

nation.3

3 See 448 U.S. at 459 (opinion of Burger, C.J.) (“ in fiscal year

1976 less than 1% of all federal procurement was concluded with

minority business enterprises, although minorities comprised 15-

8

Indeed, in Fullilove the statistical disparity— minori

ties were 15% to 18% of the population and received

less than 1% of public contracting funds— was far less

dramatic than the 0.67% to 50% disparity that Rich

mond faced. The conclusion that Richmond had an ade

quate statistical basis for enacting a subcontracting re

quirement therefore follows a fortiori from Fullilove.

b. The court of appeals ruled that the Richmond Plan

was not narrowly tailored to its remedial objective be

cause the City’s waivable 30% goal was an “ arbitral' [y]

. . . figure [that] simply emerged from the mists.” J.S.

App. 11a. Fullilove rejected just such an attack on the

10% figure used by Congress. See, e.g., Brief for Peti

tioner General Building Contractors, Fullilove v. Klutz-

nick, No. 78-1007, at 22 (“ Congress made a purely ar

bitrary selection” of a 10% requirement).

Justice Powell explained in Fullilove why Congress’s

choice of a 10% requirement was reasonable, and his ex

planation fully justifies the waivable 30% figure chosen

by Richmond. Justice Powell explained that the 10%

requirement of Section 1 0 3 (f)(2 ) was warranted be

cause that figure fell approximately “ halfway between

the present percentage of minority contractors and the

percentage of minority group members in the Nation.”

448 U.S. at 513-514 (Powell, J., concurring). See also

id. at 488-489 (opinion of Burger, C.J.). There were

almost no minority contractors in Richmond (see J.S.

Supp. App. 164), which has a minority population of

50%. The City’s choice of a waivable 30% goal is there

fore firmly supported by Justice Powell’s reasoning.

18% of the population” ) ; id. at 562-563 (“ [The] 10% MBE par

ticipation requirement . . . was thought [by Congress] to be

required to [avoid] . . . repetition of the prior experience . . .

[in which] participation by minority business accounted] for

an inordinately small percentage of government contracting.” ) ;

id. at 511 (Powell, J., concurring) (“ By the time Congress en

acted § 1 0 3 (f)(2) in 1977, it knew that other remedies had failed

. . . [because] the fact remained that minority contractors were

receiving less than 1% of federal contracts.” ) ; id. at 520 (Marshall,

J., concurring in the judgment).

9

c. The court of appeals’ approach to the nonstatisti-

cal bases of the Richmond Plan is similarly irreconcil

able with Fullilove. The court of appeals discounted the

statements, made during the Richmond City Council’s

hearing, that the construction industry in Richmond had

been marked by discrimination, on the ground that these

statements were “ conclusory,” “ general,” and often made

by supporters of the Plan. J.S. App. 6a. But in Fulli

love, a majority of the Members of this Court relied

extensively on statements of comparable generality made

by supporters of Section 1 0 3 (f)(2 ). Indeed, the state

ments on which the Court relied in Fullilove were, for

the most part, made in connection not with Section

103(f) (2) but with other federal programs to aid mi

nority enterprises. See 448 U.S. at 458-463 (opinion of

Burger, C.J.) ; id. at 504 (Powell, J., concurring) ; id. at

520 (Marshall, J., concurring in the judgment).

d. The court of appeals ruled that the City’s plan was

invalid because the City had not made “ showing[s]”

(J.S. App. 8a) or “particularized findings” of prior dis

crimination (id. at 5a). But Chief Justice Burger ex

plicitly noted in Fullilove that Section 1 0 3 (f)(2 ) “ re

cites no preambulary ‘findings’ ” (448 U.S. at 478).

Indeed, a majority of the Members of the Court empha

sized that it is inappropriate to require a legislative body

to produce specific findings to support the actions it

takes.'*

In Fullilove, of course, the question was whether Con

gress should be required to make specific findings. But 4 *

4 See 448 U.S. at 478 (“Congress, of course, may legislate with

out compiling the kind of ‘record’ appropriate with respect to

judicial or administrative proceedings.” ) ; id. at 502-503 (Powell,

J., concurring) (“ Congress is not expected to act as though it were

duty bound to find facts and make conclusions of law. . . . [F ] ore-

ting] Congress to make specific factual findings with respect to

each legislative action . . . would mark an unprecedented imposi

tion of adjudicatory procedures upon . . . the legislative process.” ) ;

id. at 520 n.4 (Marshall, J., concurring in the judgment) (The

“view [that] Congress must make particularized findings . . . is

fundamentally misguided.” ).

10

imposing such requirements on a state or local legisla

tive body is at least as intrusive and unjustifiable. Cf.

FERC v. Mississippi, 456 U.S. 742, 777-778 (1982)

(O’Connor, J., dissenting). The inappropriateness of the

requirement of specific findings stems from the nature

of the legislative process itself. When elected representa

tives act, they bring to bear knowledge that they have

gathered from a wide range of sources, including their

general experience in public life and their contacts with

constituents. This collective knowledge cannot be cabined

in “ findings” or “ showings” about specific acts of dis

crimination.

e. The court below appears to have concluded that

the Richmond Plan was invalid because it was not based

on evidence of discrimination by the City itself. J.S.

App. 5a, 6a, 8a, 9a. But there was no suggestion in

Fidlilove that Section 103(f) (2) was justified because

of discrimination by the federal government, as a dissent

in that case pointed out. 448 U.S. at 528 (Stewart, J.,

dissenting). Section 103(f) (2 ), like the Richmond Plan,

was directed to discrimination in the construction indus

try and among the recipients of federal grants. See,

e.g., id. at 475, 478 (opinion of Burger, C .J .); id. at

505-506 (Powell, J., concurring).

2. The court of appeals did not attempt to reconcile

its decision with Fidlilove or to explain why state and

local subcontracting requirements must meet standards

that are stricter than those specified in Fullilove. Other

courts of appeals, however, have asserted that Congress

has greater power to remedy racial discrimination than

state and local governments have. See, e.g., Associated

General Contractors v. City and County of San Fran

cisco, 813 F.2d 922, 928-934 (9th Cir. 1987) (petition

for rehearing pending).

a. The notion that Congress’s authority to remedy dis

crimination is greater than that of state and local gov

ernments is unfounded in the law, and represents an

unwarranted inversion of important values of federal

ism. It is true, of course, that Section 5 of the Four

11

teenth Amendment greatly expanded the power of Con

gress to remedy racial discrimination. See Katzenbach v.

Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 650-651 (1966); Ex Parte Vir

ginia, 100 U.S. (10 Otto) 330, 345-346 (1880). But the

reason for this expansion was not to occupy the field or

to preempt state and local action designed to remedy dis

crimination. Rather, the drafters of the Fourteenth

Amendment expanded the power of Congress because

they doubted that the States would adequately enforce

the rights of the newly freed slaves to be free from un

lawful discrimination.6

Against this background, it would be highly paradoxi

cal to construe the Fourteenth Amendment to reduce the

authority of state and local governments to deal with the

problem of discrimination. The determination that ra

cial discrimination was a national problem did not mean

that it ceased to be a local problem. On the contrary,

there is every reason to believe that the Framers of the

Fourteenth Amendment would have welcomed state and

local efforts to eradicate the effects of discrimination,

where such efforts were forthcoming. Cf. The Slaughter-

House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36, 77-78 (1872)

( “ [T]he Fourteenth Amendment [did not] . . . transfer

the security and protection of all the civil rights . . .

from the States to the Federal Government” ) ; see

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265, 368 (1978) (opinion of Brennan, White,

Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ.).

From a practical standpoint, local remedies for dis

crimination are likely to be far preferable to federal

remedies. Congress lacks familiarity with local condi

6 See, e.g., The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36,

70-71 (1872); Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2768 (1866)

(statement of Sen. Howard) (Section 5 “enables Congress, in case

the States shall enact laws in conflict with the principles of the

amendment, to correct that legislation” ) ; R. Harris, The Quest

for Equality 53 (1960); J. tenBroek, The Antislavery Origins of

the Fourteenth Amendment 204-207 (1951); H. Flack, The Adop

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment 138 (1965).

12

tions; it acts on the basis of nationwide generalizations

that will necessarily be over- and under-inclusive. For

example, while some industries have a record of racial

discrimination throughout the Nation, it is also some

times the case that the firms in a particular locality have

engaged in discrimination even though the industry has

an excellent national record. Under the court of ap

peals’ approach, the local government’s power to act in

such a situation will be sharply limited. Congress will be

forced to choose between imposing a national solution,

which may be excessive, and allowing the problem to go

without remedy.

Similarly, a local government will be able to tailor its

remedy to local conditions. For example, any nationwide

numerical goal or target will be unrealistically high for

areas of the country with a low minority population, and

too low to be a fully effective remedy in areas with a

high minority population. Local programs will not en

counter this difficulty. Of course, a national goal may

contain a waiver provision, as the Section 103(f) (2)

program did. But if variations are to be made to accom

modate local conditions, it is far better that they be

adopted through local political processes than by the dis

cretionary judgments of a federal administrator.

b. Nothing in the opinions in Fidlilove suggests that

the Fourteenth Amendment’s expansion of Congress’s au

thority restricts the power of state and local govern

ments to remedy discrimination. Members of the Court

did, of course, emphasize the scope of Congress’s power

to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment. See, e.g., 448

U.S. at 483 (opinion of Burger, C.J.) ; id. at 499-502

(opinion of Powell, J ). But they did so only to answer

arguments that Congress might lack the power to act

in this area. See, e.g., id. at 476 (opinion of Burger,

C.J.). State and local governments have always had the

authority— under the police power and, as here, by virtue

of their power to control public expenditures— to act

against racial discrimination. The opinions in FullUove

do not suggest that the existence of Congress’s power

under Section 5 somehow derogates from that traditional

state and local authority."

c. Perhaps most important, local solutions to the prob

lems of racial discrimination have crucial political and

social advantages over federal measures. When a deci

sion is made at the local level, the officials responsible

for it can be held directly politically accountable. Conse

quently, a decision by the elected officials of a state or

local government reflects a decision by the people most

directly affected to address the problem of racial dis

crimination in a certain way. The process of considering

and enacting a remedy like Richmond’s can help build a

consensus. If circumstances change, the remedy can be

modified. A federal requirement, by contrast, is imposed

coercively from above. Ultimately the problems stem

ming from racial discrimination will be solved not by

such coercive measures but by the development of a con

sensus and an understanding at the local level.

As we have noted (pages 1-2, supra), state and local

governments throughout the Nation have determined,

through their elected representatives, that public con

tracting requirements comparable to Richmond’s will

help to remedy the effects of racial discrimination. In

these ways, FullUove has become “ an important part of

the fabric of our law” (Johnson v. Transportation

Agency, 107 S. Ct. 1442, 1459 (1987) (Stevens, J., con

curring) ; see id. at 1461 (O’Connor, J., concurring in the

judgment)). It has become the basis for political and

economic accommodation of the various interests that are

affected when the government attempts to remedy the

effects of discrimination— an accommodation that has 6

13

6 Thus Chief Justice Burger’s statement that “ in no organ of

government, state or federal, does there repose a more compre

hensive remedial power than in the Congress, expressly charged by

the Constitution with competence and authority to enforce equal

protection guarantees” (448 U.S. at 483) must be taken to mean

what it says: Congress’s authority is as broad as that of state and

local governments. The opinion does not say— and, in our view,

it would be paradoxical and incorrect to say— that congressional

power is broader.

14

taken place on the local level, in scores of localities and

more than two-thirds of the States, throughout the Na

tion. There is no sufficient reason for upsetting these

accommodations and precluding state and local govern

ments from addressing the problem of discrimination in

this way.

B. The Richmond Plan Promotes Compelling Government

Interests And Does Not Impose Unfair Burdens On

Nonminority Contractors.

FuLlilove is, in our view, sufficient to dispose of this

case. But there is no inconsistency between Fidlilove and

the standards established in the other decisions of this

Court that have considered the constitutionality of race

conscious measures. Although the Court does not appear

to have agreed on a specific formulation of these stand

ards, it is clear that such a measure is constitutional if

it is designed to achieve a sufficiently important gov

ernment objective and if it is tailored so as not to im

pose undue burdens on individuals who are not members

of minority groups.7

The Richmond Plan satisfies these standards. Indeed,

although we do not believe that a state or local govern

ment must show a “ compelling” interest in order to sus

tain a race-conscious remedy, the objectives that the

Richmond Plan promotes are in fact compelling, and the

burdens it imposes on nonminorities are minimal.

1. The Richmond Plan promotes the compelling inter

est of remedying racial discrimination in the con

struction industry.

The Richmond City Council explicitly stated that it

was adopting the Minority Business Utilization Plan for

the purpose of remedying prior racial discrimination.

The court of appeals did not deny that the Plan would

7 See, e.g., United States v. Paradise, 107 S. Ct. 1053, 1064 &

n.17 (1987) (plurality opinion); Wygant, 476 U.S. at 274 (plurality

opinion); id. at 286-287 (O’Connor, J., concurring); id. at 301-302

(.Marshall, J., dissenting); id. at 313 (Stevens, J., dissenting).

15

be an effective means of remedying the effects of dis

crimination in the construction industry. Instead, the

court ruled that Richmond did not have an adequate

basis for concluding that such discrimination exists. In

this section we address that aspect o f the court of ap

peals’ decision. In addition, we will explain why a race

conscious subcontracting requirement like Richmond’s is

an especially useful means— indeed, an indispensable

means— of remedying discrimination in the construction

industry.

The court of appeals also suggested that Richmond

was entitled to remedy only its own discrimination, and

that remedying discrimination in the construction indus

try did not constitute a sufficient government interest to

uphold the Richmond Plan. We address that aspect of the

court of appeals’ reasoning in Part B2 below.

a. i. In Wygant, Members of this Court stated that

a government may adopt a race-conscious remedy for

past discrimination when it “ha [s] a strong basis in evi

dence for its conclusion that remedial action [is] neces

sary.” 476 U.S. at 277 (plurality opinion). See also id.

at 293 (O’Connor, J., concurring) ( “ a firm basis for

concluding that remedial action [is] appropriate” ). The

Richmond City Council had more than a “ strong basis”

for concluding that there was discrimination in the con

struction industry. Perhaps the clearest evidence was

the stark statistical disparity: minorities constitute half

of Richmond’s population, but have received only two-

thirds of 1% of public construction contract funds.

The court of appeals dismissed this statistical demon

stration as “ spurious” (id. at 8a) and “not . . . mean

ingful” (id. at 10a). “The appropriate comparison,” the

court asserted, “ is between the number of minority con

tracts and the number of minority contractors” (id. at

7a; emphasis in original). The court of appeals stated

that the City’s “ [s]howing that a small fraction of city

contracts went to minority firms,” did not “demonstrate

discrimination” because “ the number of minority-owned

contractors in Richmond was also quite small.” Ibid.

16

This ruling is manifestly incorrect. The error in the

court of appeals’ approach is clear from numerous deci

sions of this Court, and it was recently explained by

Justice O’Connor: when discrimination prevents minori

ties from “ obtaining th[e] experience” that they need

to qualify for a position, the “ relevant comparison” is

not with the percentage of minorities in the pool of quali

fied candidates but with “ the total percentage of [minori

ties] in the labor force.” Johnson v. Transportation

Agency, 107 S. Ct. 1442, 1462 (1987) (opinion concur

ring in the judgment). See also id. at 1462-1463; Steel

workers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 198-199 (1979) ; Inter

national Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324, 339 n.20 (1977). Discrimination does not

merely prevent established minority contractors from

obtaining contracts; it discourages and prevents minori

ties from entering the pool of contractors in the first

place. The absence of the disparity on which the court

of appeals insisted may simply be evidence that minorities,

faced with widespread discrimination, did not quixotically

enter a business in which they knew they would not be

allowed to succeed.

An individual who wishes to take advantage of sub

contracting opportunities must expend considerable re

sources. Such an individual ordinarily must incorporate,

obtain bonding, hire managerial employees, buy or lease

equipment, establish contacts with union hiring halls or

other sources of labor, arrange credit, investigate bidding

opportunities, and determine the bid that the newly formed

firm can enter. These are costly operations. If there is

discrimination at any stage— in the discretionary deci

sions of general contractors, in the practices of bonding

companies, in the judgments banks or equipment leasing

companies make about creditworthiness, in the willing

ness of skilled or unskilled laborers to work for a mi

nority business— the minority group member is immedi

ately placed at a competitive disadvantage. In these cir

cumstances, few minority entrepreneurs will be willing to

invest the necessary resources to establish a contracting

17

firm. They will pursue opportunities in a different field,

where discrimination may be less of an obstacle to success.8

Significantly, these barriers continue to exist after acts

of intentional discrimination have ceased. “ [B]arriers

to competitive access ha[ve] their roots in racial and

ethnic discrimination, and . . . continue today, even

absent any intentional discrimination or other unlawful

conduct.” Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 478 (opinion of Burger,

C.J.). Experience— a “ track record”— is highly important

to any firm seeking contracting opportunities. Id. at 467.

A network of contacts and a prior working relationship

can be crucial in obtaining credit, bonding, or high-

quality employees. See Fumco Construction Corp. v.

Waters, 438 U.S. 567, 570, 572 (1978) (describing hir

ing by construction “job superintendent” who “ hired only

persons whom he knew to be experienced and competent

in th[e] type of work or persons who had been recom

mended to him as similarly skilled” ) .

Indeed, it is often rational, and not an act of racial

discrimination, for general contractors, banks, and others

to give preferential treatment to firms that have an

established record of reliability. This case furnishes an

example: the district court found that a minority sub

contractor interested in obtaining part of appellee’s con

tract could not obtain a timely price quotation from a

supplier because the minority entrepreneur “ was un

known to” the supplier, and the supplier’s agent “ was

not allowed to quote to unknown [firms] until they had

undergone a credit investigation.” J.S. Supp. App. 123.

Because discrimination has prevented minorities from

entering the field in the past, minority firms will con

tinue to suffer the competitive disadvantages caused by

relative lack of experience even if there is no longer any

8 On several occasions, this Court has recognized that entrenched

hiring discrimination will deter minorities from applying for jobs.

See, e.g., Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC, 106 S. Ct.

3019, 3036-3037 (1986); Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 365-367. It follows

a fortiori that discrimination will discourage minorities from form

ing contracting firms, a much more expensive and difficult task.

18

intentional discrimination at all. Minority group mem

bers will, accordingly, be unwilling to establish firms,

and the disparity on which the court of appeals insisted

will not appear.

Of course, it is theoretically possible that these bar

riers were not the source of the virtual exclusion of

minorities from Richmond’s public contracting business.

But it is extremely unlikely. See Teamsters, 431 U.S. at

342 n.23; Johnson, 107 S. Ct. at 1465 (O’Connor, J.,

concurring in the judgment). Faced with the undisputed

fact that there were essentially no minority contractors

in a City that was half minority, the Richmond City

Council could have concluded either that virtually no

minorities were willing and able to become contractors,

or that some appreciable percentage had been excluded

by discrimination. The Council, with its intimate knowl

edge of the City’s history, thought the latter hypothesis

was more plausible. There is no justification for denying

the City the right to reach this conclusion.

ii. In addition to the statistical evidence, the Rich

mond City Council had other reasons to believe that dis

criminatory practices had denied minorities opportunities

in the construction industry. For example, a member of

the City Council, as well as the City Manager, speaking

from experience, stated their judgment that there had

been widespread discrimination in the construction in

dustry. J.S. Supp. App. 38, 164-165. In addition, the

discriminatory exclusion of minorities from craft unions

is so notorious that this Court has held it a proper sub

ject for judicial notice. Weber, 443 U.S. at 198 & n.l.

Craft unions supply employees to construction firms, and

often new construction firms are formed by craft work

ers.8 Thus the historic discrimination against minorities

by the craft unions is likely to have had a severe effect

on minorities’ opportunities in the construction industry.

Finally, as the district court noted (J.S. Supp. App.

8 See, e.g., J. Gillies & F. Mittelbach, Management in the Light

Construction Industry 27, 28 (1962); see generally R. Glover,

Minority Enterprise in Construction (1977).

1

165), the City had before it the same evidence that Con

gress had when it enacted the Fullilove program—

“ abundant evidence from which [a legislature] could con

clude that minority businesses have been denied effective

participation in public contracting opportunities by

procurement practices that perpetuated the effects of

prior discrimination,” and “ direct evidence” that a “ pat

tern of disadvantage and discrimination existed with

respect to state and local construction contracting”

(Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 477-478 (opinion of Burger,

C .J.)).

The court of appeals considered this nonstatistical

evidence insufficient because it was not captured in ad

equately “ particularized findings” (J.S. App. 5a). As we

noted above, this conclusion is inconsistent with Fullilove,

and it ignores the realities of the legislative process. The

court of appeals relied exclusively on Wygant for its con

trary conclusion, but one Members of the five-justice

majority in Wygant fully explained why specific findings

of prior discrimination should not be required. 476 U.S.

at 289-293 (O’Connor, J., concurring). And it appears

that a majority of the Court in Wygant rejected a require

ment that a government must make formal findings of

discrimination before adopting a race-conscious remedy.

See id. at 312 n.7 (Marshall, J., dissenting).

The court of appeals rejected the City’s reliance on the

data developed by Congress with the statement that

“ [n]ational findings do not alone establish the need for

action in a particular locality.” J.S. App. 9a. But in City

of Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc., 475 U.S. 41

(1986), a case involving an ordinance that arguably af

fected First Amendment rights, this Court squarely

rejected— as “unnecessarily rigid”— the contention that

because the City had not presented “ studies specifically

relating to ‘the particular problems or needs of Renton,’

the city’s justifications for the ordinance were ‘conclusory

and speculative.’ ” Id. at 50 (citations omitted). This is

19

20

almost precisely the contention that the court below

accepted.

Renton held that a City is “ entitled to rely on the ex

periences of . . . other cities” even when it is regulating

in an area involving constitutional rights. Id. at 51. A

City is not required “ to conduct new studies or produce

evidence independent of that already generated by other

cities, so long as whatever evidence the city relies upon

is reasonably believed to be relevant to the problem that

the city addresses.” Id. at 51-52. The statistical evi

dence of discrimination in Richmond gave the City ample

reason to believe that the congressional findings were

relevant to its situation.

Finally, the court of appeals’ approach is insensitive to

important practical considerations that affect state and

local governments. First, as a practical matter, a require

ment that a City compile a “ record” or make specific

“ findings” with an eye toward judicial review will place

all but the largest localities at an unwarranted disadvan

tage. Translating the insights, experience, and judgment

of an elected official into a “ record” or “ particularized

findings” suitable for judicial review is a task for a pro

fessional staff, preferably a staff with an extensive legal

background. Congress and the Executive Branch of the

federal government employ staffs that are adept at com

piling a record that will withstand the kind of review

that the court of appeals’ opinion contemplates. But

many medium-size and small localities— whose delibera

tions may be every bit as careful and thoughtful— do not

employ, and cannot afford to employ, that kind of pro

fessional staff.

Second, and more important, the court of appeals’

approach ignores the nature— and the special advantages

— of the political process. The court of appeals appears

to have required that state and local governments iden

tify particular occasions on which identifiable acts of

discrimination occurred. See, e.g., J.S. App. 8a ( “There

has been no showing that qualified minority contractors

who submitted low bids were passed over. There has

been no showing that minority firms were excluded from

the bidding pool.” ).

Such a procedure— in which specific discriminatory

acts or actors are identified— would benefit no one. It

would require state and local governments to engage

in a destructive process of recrimination and accusation

if they wished to address the effects of racial discrimi

nation through a race-conscious remedy. The genius of

the political process is that it can often find a solution,

even to problems as difficult as those implicated in this

case, without reopening old wounds and setting individ

uals against each other. See Schlesinger v. Reservists

Committee to Stop the War, 418 U.S. 208, 221 n. 10

(1974) ( “The legislative function is inherently general

rather than particular and is not intended to be respon

sive to adversaries asserting specific claims or interests

peculiar to themselves.” ). The divisive process envisioned

by the court of appeals would forfeit these advantages.

b. A race-conscious subcontracting requirement is a

fully appropriate remedy for the discrimination that

Richmond found to exist in the construction industry.

A measure that simply required the firms involved in the

construction industry not to discriminate would not have

been effective. Indeed, we do not understand the court

of appeals to have suggested otherwise.

As we noted above, and as Members of the Court ex

plained in detail in Fullilove, discrimination in the con

struction industry creates a variety of subtle but severe

barriers to competitive success. Intentional discrimination

can handicap a construction firm in ways that a mere pro

hibition against discrimination cannot prevent, no matter

how diligently it is enforced. More important, even after

intentional discrimination has ceased, minority firms will

continue to suffer from its effects. A simple prohibition

against discrimination will do nothing to remedy those

effects. See pages 16-18, supra; Fullilove, 448 U.S. at

461-467, 477-478 (opinion of Burger, C.J.).

For example, as we have noted, a rational, non-

discriminatory general contractor will often prefer to

21

22

give work to a subcontractor with which it has worked on

previous projects and which it knows to be reliable. A

bank or a bonding company will have nondiscriminatory

reasons for giving better terms to firms with a long record

of reliable performance. Informal networks, developed

over years of working together, will often be the best

means of hiring good employees. See pages 17-18, supra.

In each of these areas, minority firms are at a com

petitive disadvantage because they lack experience and

contacts; and they lack experience and contacts because of

past discrimination. This disadvantage cannot be over

come simply by banning discrimination. It can be over

come only by a compensatory remedy that improves the

competitive position of minority firms.

Richmond’s subcontracting requirement accomplishes

this task in a measured, tailored fashion. It is a tem

porary device; the City will reassess the need for a race

conscious remedy before extending it. It does not guaran

tee any particular contract to any minority firm. Because

of the waiver provision, minority firms have an incentive

to be as efficient as possible; if their costs are too high, a

general contractor may obtain a waiver. Moreover, as the

district court explained (J.S. Supp, App. 145-146):

[U]nder the Plan, there remains every incentive for

both MBEs and non-MBEs to compete against one

another. . . . The Plan simply changes the struc

ture of the competition, by requiring non-MBEs to

team up, insofar as possible, with MBEs, to com

pete for contracts against other teams of non-

MBEs and MBEs.

The Richmond Plan does, however, ensure that a general

contractor will not lose a job because it has subcontracted

with a minority firm that has higher costs as a result of

past discrimination. And, of course, the Richmond Plan

requires general contractors to make real efforts to seek

out minority firms; it does not permit a general con

tractor to make a merely perfunctory effort before re

turning to the traditional ways of doing business.

23

2. Richmond may enact a race-conscious remedy for

prior discrimination in the local construction in

dustry without admitting complicity in racial dis

crimination.

As we have explained, the Richmond City Council

had more than sufficient basis for concluding that racial

discrimination in the construction industry blocked mi

nority access to city construction contracts, and the Rich

mond Plan was well designed to remedy this situation.

But passages in the opinion below suggest that the court

imposed an additional requirement on Richmond: the

City, the court of appeals suggested, could enact a race

conscious plan only to remedy its own prior discrimina

tion. The Richmond Plan, according to the court of

appeals, could not be justified as a remedy for discrimina

tion in the construction industry, no matter how conclu

sively Richmond demonstrated the existence of that dis

crimination, unless the City itself was in some sense guilty

of discrimination. See J.S. App. 5a, 6a, 8a, 9a.

This conclusion is erroneous. In some circumstances, a

local government is obligated to use race-conscious means

to remedy its own discrimination. North Carolina State

Board of Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43, 46 (1971);

see also Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430

(1968). The question in this case, however, is not what

a state or local government is obligated to do but what

it may do. It is well established that a state or local gov

ernment not only may act to remedy private discrimina

tion but has the most compelling interest in doing so.

Moreover, both logic and this Court’s decisions support the

conclusion that a state or local government may use race

conscious measures to remedy private discrimination and

its effects.

a. This Court has repeatedly recognized that govern

ments have an interest of the highest order in eliminat

ing private discrimination and its effects. See, e.g.,

Board of Directors v. Rotary Club, 107 S. Ct. 1940, 1947

(1987) ( “ the State’s compelling interest in eliminating

discrimination against women” ) ; Bob Jones University

24

v. United States, 461 U.S. 574, 604 (1983) (“ [T]he gov

ernment has a fundamental, overriding interest in eradi

cating racial discrimination” ) ; Runyon v. McCrary, 427

U.S. 160, 179 (1976); Railioay Mail Association v. Corsi,

326 U.S. 88 (1945). Indeed, the Court has recently ruled

that a State government’s interest in “ eliminating dis

crimination and assuring its citizens equal access to pub

licly available goods and services”— an interest similar to

that asserted by Richmond in this case— is not only a

“compelling state interest [] of the highest order" (Roberts

v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 624 (1984)), but

is sufficiently weighty to justify the infringement of a con

stitutional right (see id. at 623). See also id. at 632

(O’Connor, J., concurring) ( “ the profoundly important

goal of ensuring nondiscriminatory access to commercial

opportunities in our society” ) .

b. The City’s interest in combatting private discrim

ination is even stronger in this case, because the City is

attempting to ensure that its own expenditures of public

funds do not contribute to the harms caused by discrim

ination. Richmond is not acting merely as a regulator

of private affairs, as the States were in Roberts, supra,

and Rotary Club, supra-, instead, the City is attempting

to prevent its own spending decisions from supporting

subtle forms of discrimination or perpetuating the effects

of past discrimination. The Court has recognized that a

local government has unusually great latitude to promote

its interests when it is not acting in a regulatory capacity

but is, for example, “expend [ing] only its own funds in

entering into construction contracts for public projects”

( White v. Massachusetts Council of Construction Em

ployers, 460 U.S. 204, 214-215 (1983)). See also Reeves,

Inc. v. Stake, 447 U.S. 429, 436-437 (1980) ; Hughes v.

Alexandria Scrap Corp., 426 U.S. 794, 810 (1976).

When, as here, the City is attempting to avoid giving

support to private racial discrimination and its effects,

the City’s power is at its greatest.

We note in this connection that several courts have

held that a state or local government can violate the Con

25

stitution by entering into contractual relationships with

private firms that discriminate.10 See also National Black

Police Association v. Velde, 712 F. 2d 569 (D.C. Cir.

1983) (officials are subject to personal liability if they

knowingly provide public funds to recipients engaged in

discrimination), cert, denied, 466 U.S. 963 (1984). While

we do not agree with these decisions, they further estab

lish the extraordinary weight of state and local govern

ments’ interest in ensuring that public funds are not

spent in a way that perpetuates racial discrimination or

its effects. Cf. Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455

(1973).

c. In view of the extraordinary importance of the gov

ernment’s interest in eliminating private discrimination

and its effects, it would be unreasonable to preclude state

and local governments from using race-conscious meas

ures in appropriate circumstances. The Court has ap

proved race-conscious remedies for government discrim

ination because there are occasions on which government

discrimination, and its effects, cannot be eliminated with

out such measures. See, e.g., North Carolina State Board

of Education, supra-, McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39,

41 (1971).

The same is sometimes true of private discrimination.

As the Court has recognized, sometimes a mere require

ment of nondiscrimination is not enough to prevent such

discrimination or to alleviate its effects. See, e.g., Local

28 of Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC, 106 S. Ct. 3019,

3036-3037 (1986); Fullilove, supra. See also Paradise,

107 S. Ct. at 1065-1072. The Court has specifically stated

that a school board may voluntarily remedy de facto seg

regation— segregation that is not the result of discrimina

tion by the government— by adopting a race-conscious

student assignment policy. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen-

10 Notably, many of these cases involved the construction industry.

See, e.g., Percy v. Brennan, 384 F. Supp. 800, 811-812 (S.D.N.Y.

1977); Byrd v. Local No. U , IBEW , 375 F. Supp. 545, 559-560

(D.Md. 1974); James v. Ogilvie, 310 F. Supp. 661 (N.D. 111. 1970);

Ethridge v. Rhodes, 268 F. Supp. 83 (S.D. Ohio 1967).

26

burg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971). See also

North Carolina State Board of Education, 402 U.S. at 45.

We of course recognize that race-conscious measures

must not be imposed casually, for whatever reason they

are adopted. They must be supported by appropriate

government interests. Moreover, the government must

take care that they do not unfairly burden nonminori

ties. But there is no basis for wholly prohibiting state

and local governments from using such measures to

remedy discrimination in appropriate cases, even if the

discrimination does not have its source in the govern

ment’s own actions.

d. The court of appeals’ conclusion that a state or

local government is limited to remedying its own dis

crimination was based entirely on statements from

Wygant. See J.S. App. 5a, quoting 476 U.S. at 274

(plurality opinion of Powell, J .). See also Wijgant, 476

U.S. at 288 (opinion of O'Connor, J .). Understood in

context, however, these statements do not support the

court of appeals’ conclusion.

Wygant involved a provision of a collective bargaining

agreement under which a school board, in making lay

offs, was to maintain a certain racial balance among

teachers. See 476 U.S. at 270-272 (plurality opinion).

That affirmative action provision, if analyzed as a reme

dial measure, was capable of being justified only in one

of two ways— as a remedy for prior discrimination by

the school board, or as a general response to the fact

that widespread discrimination in society has placed

racial minorities in a disadvantaged position. See id. at

288 n.* (opinion of O’Connor, J .).11

Justices Powell and O’Connor were concerned to reject

the suggestion that this latter notion of societal dis

crimination could justify the provision. Justice Powell

reasoned that such a justification is “ too amorphous” and

11 The school board also suggested that the measure could be

justified on the ground that it provided “ role models” for school-

children (see 476 U.S. at 274 (plurality opinion)), but that is a

nonremedial justification that has no counterpart in this case.

I

“ overexpansive” ; because “ [n]o one doubts that there

has been serious racial discrimination in this country,”

any remedies based on this notion of societal discrim

ination would be “ ageless in their reach into the past,

and timeless in their ability to affect the future.” Id. at

276 (plurality opinion).

It was in this context— in which the only suggested

remedial justifications were an open-ended notion of

societal discrimination, on the one hand, and “discrimin

ation by the local government unit in question” on the

other— that Justices Powell and O’Connor insisted on the

latter. Richmond, however, did not enact its Plan on the

basis of an open-ended assertion of societal discrimina

tion. Rather, Richmond is attempting to remedy discrimi

nation in a specific industry, on the basis of abundant

evidence (including evidence of which this Court has taken

judicial notice) that such discrimination exists. Such a

remedial effort does not present the problems of limit

lessness and amorphousness with which Justices Powell

and O’Connor were concerned.

This interpretation of the statements in Wygant is

confirmed by Justice Powell’s opinions in both Bakke and

Fullilove. In Bakke, Justice Powell contrasted “ identified

discrimination” with “ ‘societal discrimination,’ an amor

phous concept of injury that may be ageless in its reach

into the past.” 438 U.S. at 307. In Fullilove, where

there was no suggestion of prior discrimination by the

federal government, Justice Powell again emphasized that

“ identified” discrimination was sufficient to uphold the

race-conscious remedy. See 448 U.S. at 496, 497, 515.

This demonstrates that Justice Powell’s concern was that

the discrimination be “ identified” — that is, that it be

narrower than general societal discrimination—not that

it be attributable to the government actor in question. In

Wygant, the only form of identified discrimination was

discrimination by the unit of government itself. Rich

mond, however, is addressing another form of identified

discrimination. Its Plan is therefore fully consistent with

Justice Powell’s approach.

27

28

3. Richmond’s plan does not unfairly burden non

minority contractors.

The Court has emphasized that race-conscious remedial

measures must not impose undue burdens on nonminori

ties. See, e.g., Johnson, 107 S. Ct. at 1455-1456; Wygant,

476 U.S. at 282-284 (opinion of Powell, J .). The bur

dens that the Richmond Plan imposes on nonminorities

can fairly be characterized as minimal. At all events,

they are well within the range permitted by this Court’s

decisions.

To a large extent, the burdens imposed by the Rich

mond Plan fall on the City itself. They are therefore

distributed among the taxpayers. Not only is this per

haps the fairest way of dealing with the costs of remedy

ing discrimination, but it ensures that there will be a

political check on the program. I f its costs grow too

great, not isolated individuals but the taxpayers as a

whole will demand that the Plan be modified or repealed.

Because it spreads much of its cost among the taxpayers,

the Richmond Plan is superior to nearly every other

remedial measure that this Court has considered; those

measures imposed virtually the entire burden on specific

individuals and shifted little or none of it to the tax

payers (or to a comparably large group) ,12

The principal burden of the Richmond Plan falls on

the taxpayers because a general contractor can include

12 In the cases involving competitive seniority— Wygant, Fire

fighters Local Union No. 1781 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984), and

also, in important respects, Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976)— the burden fell entirely on the nonminority

employees who lost the benefits of their seniority; it is difficult to

identify any burden that fell on the employer or could be passed on

to taxpayers or customers. In cases involving affirmative action in

hiring, promotions, or university admissions— Paradise, Johnson,

Local No. 93, Firefighters v. Cleveland, 478 U.S. 501 (1986), Local

28 of Sheet Metal Workers, Weber, and Bakke— the government

or employer incurred, in theory, the additional cost of employing

or educating a minority applicant who was supposedly less well-

qualified. But in practical terms that cost is not likely to be great.

Realistically, the burden fell on the disappointed applicant.

29

in its bid— and thereby pass through— any additional

costs that reflect the competitive disadvantage of the

minority subcontractors. Neither the general contractor,

nor any bonding or lending institution, nor any other

firm that deals with the minority subcontractor, is forced

to incur additional net costs.

It is of course true that the Plan is likely to cause

some nonminority subcontractors to lose business. But

in this respect, as well, the Plan contrasts sharply, and

favorably, with the measures that this Court has invali

dated in the past. The collective bargaining agreement

in Wygant, for example, resulted in layoffs of non

minority employees whose seniority would otherwise have

protected them. This aspect of Wygant was crucial to

the outcome of that case. See 476 U.S. at 282-284

(Powell, J . ) ; id. at 294-295 (White, J., concurring).

By contrast, the burden imposed on individual firms

by the Richmond Plan— like the burden imposed by the

federal program upheld in FuHilove— is “ limited and so

widely dispersed that it [ ] . . . is consistent with funda

mental fairness.” FuHilove, 448 U.S. at 515 (Powell,

J., concurring) (footnote omitted). The Richmond Plan

affects only the construction industry, only a segment

of that market— municipal contracts— and only 30% of

the dollar volume of that segment. We know of nothing

in the record that suggests that any costs that the Rich

mond Plan imposes on nonminority contractors will be

concentrated on a few firms. Moreover, far from up

rooting settled expectations acquired through years of

seniority, the Richmond Plan threatens only the con

tingent possibility of future economic gain. This in

terest, as the Court has emphasized, has always been

entitled to only minimal legal protection. See, e.g., Andrus

v. Allard, 444 U.S. 51, 66 (1979); Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 778 (1976); Robins

Dry Dock & Repair Co. v. Flint, 275 U.S. 303, 308-309

(1927) (Holmes, J.).

Finally, since Richmond had ample reason to conclude

that there was substantial discrimination in the con-

30

struction industry, “ it was within [the City’s] power

to act on the assumption that in the past some nonmi

nority businesses may have reaped competitive benefit

over the years from the virtual exclusion of minority

firms from these contracting opportunities.” Fullilove,

448 U.S. at 485 (opinion of Burger, C.J.). As we noted,

following Justice Powell’s logic in Fullilove, the 30% fig

ure chosen by Richmond was a reasonable estimate of

the amount of City contracting dollars that would have

reached minorities in the absence of discrimination. See

page 8, supra. There is reason to believe, therefore, that

the nonminority firms that are disadvantaged by the

Richmond Plan may be losing only opportunities that

they would not have had in the absence of prior dis

crimination.

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the court of appeals should be re

versed.

Respectfully submitted,

David A. Strauss

University of Chicago

Law School

1111 East 60th Street

Chicago, IL 60637

(312) 702-9601

April 21,1988

Benna Ruth Solomon

Chief Counsel

State and Local

Legal Center

444 N. Capitol Street, N.W.

Suite 349

Washington, D.C. 20001

(202) 638-1445

Counsel of Record for the

Amici Curiae

APPENDICES

APPENDIX I

Minority Business Enterprise Programs

of State Governments 1 2

State Citation Coverage Goals

Alabama Exec. Order No. 89

(1978)

2

Arkansas Exec. Order No. 83-2 Goods and services 10%

Ark. Stat. Ann. Creates MBE office;

§§ 5-916.2 to 5-916.6 defines functions

Exec. Order

Proc. E083-2

Goods and services 10%

1 In addition to the procurement measures listed in the Table, Alaska law provides for an employment

preference for “economically disadvantaged minority residents” in areas of the State suffering from underem

ployment. The Labor Commissioner identifies zones of underemployment. In those zones, residents who are

“economically disadvantaged minority residents” have a preference for 25% of the jobs or a percentage repre

sentative of the number of minority citizens in the zone, whichever is greater. Alaska Stat. §30.10.170 (1987).

Georgia allows an income tax credit of 10% of payments made by contractors to MBE subcontractors. H.B.

635 A /P , S.B. 48-7-38, eff. Jan. 1, 1985.

Kansas has established an Office of Minority Business to offer advice and technical assistance to M BEs; the

office helps locate resources and acts as a minority advocate.

2 The 1978 Executive Order created a Department of Small and Minority Business Enterprise to encourage

those businesses. The policy was to be “implemented by all State agencies, departments and institutions by

purchasing a fair proportion of the supplies, commodities and services required . . . . ’ ’