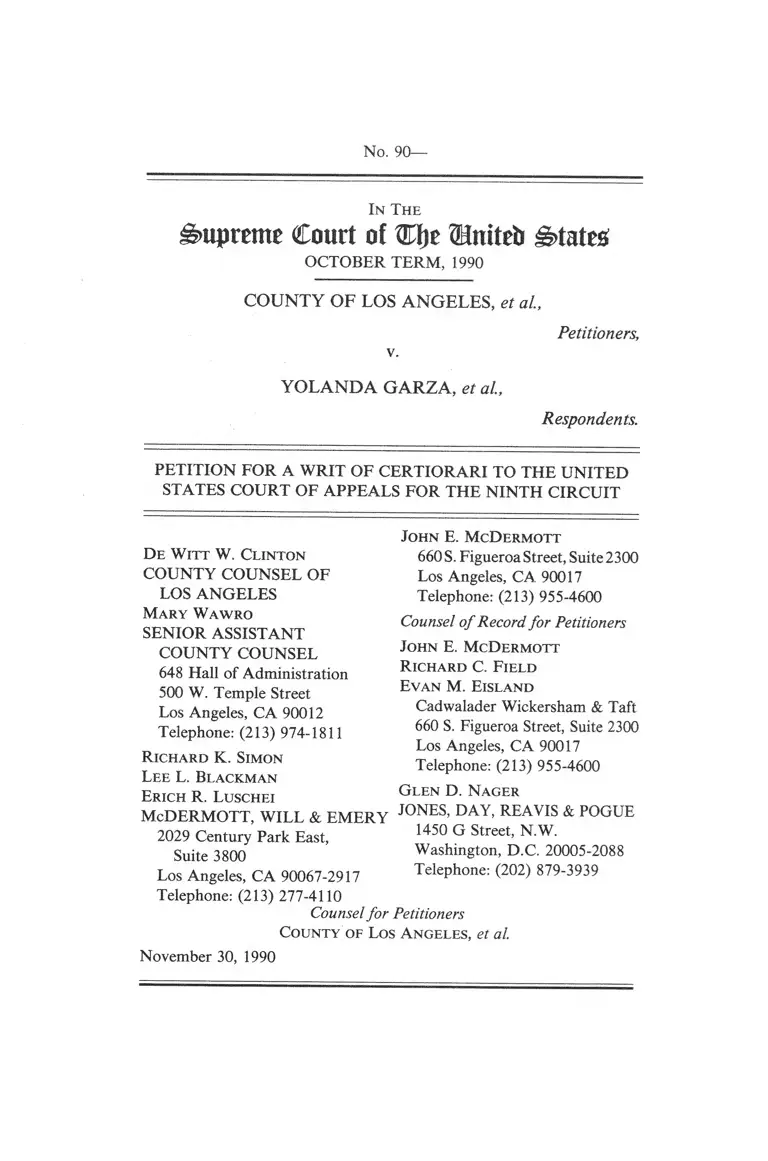

County of Los Angeles v. Garza Petition of Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

November 30, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. County of Los Angeles v. Garza Petition of Writ of Certiorari, 1990. d47202b6-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/48ead080-ab08-4799-bce2-68a350766a7e/county-of-los-angeles-v-garza-petition-of-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 9 0 -

In T he

S u prem e C o u rt of C ljc ®niteb s ta te s

OCTOBER TERM, 1990

COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

YOLANDA GARZA, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

D e W it t W. Clinton

COUNTY COUNSEL OF

LOS ANGELES

M ary W aw ro

SENIOR ASSISTANT

COUNTY COUNSEL

648 Hall of Administration

500 W. Temple Street

Los Angeles, CA 90012

Telephone: (213) 974-1811

R ichard K. Simon

Lee L. Blackm an

Erich R. Luschei

McDe r m o t t , w il l & e m e r y

2029 Century Park East,

Suite 3800

Los Angeles, CA 90067-2917

Telephone: (213) 277-4110

John E. M cD erm ott

660 S. Figueroa Street, Suite 2300

Los Angeles, CA 90017

Telephone: (213) 955-4600

Counsel o f Record for Petitioners

J ohn E. M cD erm ott

R ichard C. F ield

Evan M. E island

Cadwalader Wickersham & Taft

660 S. Figueroa Street, Suite 2300

Los Angeles, CA 90017

Telephone: (213) 955-4600

G len D. N ager

JONES, DAY, REAVIS & POGUE

1450 G Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005-2088

Telephone: (202) 879-3939

Counsel for Petitioners

County of Los A n geles , et al.

November 30, 1990

1

Questions Presented

1. Whether the one-person, one-vote, equal protection rule of

Reynolds v. Sims requires single member districts to be equal in

population or equal in citizens (or eligible voters)?

2. Whether Reynolds obligates a reapportioning body drawing

districts that are equal in population to minimize variations in

citizens and voters among the districts?

3. Whether a district court properly may infer invidious intent

from the adoption of a redistricting plan containing no material

change in boundaries, where the district court expressly found no

racial animus, where a minority group has disavowed interest in

a concentrated minority district and where the reapportioning

body failed to take affirmative action to create a minority

concentrated district because of a partisan political stalemate?

4. Whether a remedial redistricting plan that places the

remedial district in a district other than that which was the basis

for the liability finding and which is not specifically tailored to

curing the discriminatory effects of prior redistricting exceeds the

remedial power of the district court?

5. Whether the “Thornburg effects” are the effects that must

be proven in a vote dilution case alleging intentional

discrimination?

6. Whether a district court exceeds its remedial power by

imposing a Thornburg majority district remedy without first

requiring proof of the “Thornburg effects”?

7. Whether the decennial redistricting rule established in

Reynolds v. Sims should foreclose a postcensal challenge to a

redistricting plan valid under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

at the time it was adopted?

Rule 14.1(b) List of Parties

The petitioners (defendants-appellants in the proceedings

below) are County of Los Angeles; Los Angeles County Board of

Supervisors; Deane Dana, Peter F. Schabarum, and Michael D.

Antonovich, County Supervisors; Richard B. Dixon, County

Administrative Officer; and Frank F. Zolin, County

Clerk/Executive Officer.

The respondents (plaintiffs-appellees in the proceedings

below) are Yolanda Garza, Salvador H. Ledezma, Raymond

Palacios, Monica Tovar and Guadalupe De La Garza,

individually and on behalf of all Hispanic registered voters in Los

Angeles County; and United States of America. The respondents

(intervenors-appellees in the proceedings below) are Lawrence K.

Irvin, Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr., John T. McDonald, Jr.,

Ernestine Peters, Los Angeles Branch NAACP (National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People), Southern

Christian Leadership Conference of Greater Los Angeles, and

The Los Angeles Urban League, individually and on behalf of all

Black registered voters in Los Angeles County; and Sarah Flores.

The respondents (defendants in the District Court and filed a

Brief in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees in the Court of Appeals)

are Kenneth Hahn and Edmund D. Edelman, County

Supervisors.

ii

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented ............................................................. i

Rule 14.1(b) List of Parties ........................................ ii

Table of Authorities............................. vi

Opinions Below .......................................................... 1

Jurisdiction......................................................................... 2

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved................ 2

Statement of the Case ........................................................ 3

Reasons for Granting the W rit........................................... 5

I. THE REMEDIAL PLAN IS INVALID ON

TWO SEPARATE EQUAL PROTECTION

ONE PERSON ONE VOTE GROUNDS . . . 6

A. The Remedial Plan Provides Voters In

One District With The Equivalent Of

Twice As Many Votes As Voters In The

County’s Other D istricts..................... 6

B. The Court of Appeals Majority Incorrectly

Assumed That There Was No Way Or

No Obligation To Harmonize Represen

tational Equality And Electoral Equali

ty ........................................................... 11

II. THE COURT OF APPEALS RULING

THAT THE BOARD OF SUPERVISORS

INTENTIONALLY DISCRIMINATED

AGAINST HISPANICS CONFLICTS

WITH DECISIONS OF THIS COURT

AND RESTS ON IMPORTANT CONSTI

TUTIONAL AND STATUTORY QUES

TIONS OF LAW WHICH HAVE NOT

BEEN BUT SHOULD BE SETTLED BY

THIS COURT ..................................... 12

IV

Page

A. The Courts Below Applied An Erroneous

Definition Of Invidious Intent To A

Redistricting Plan Containing No Ma

terial Change In Boundaries Admit

tedly Adopted Without Racial Animus

In Circumstances Where The Hispanic

Community Disavowed Interest In A

Concentrated Hispanic District.......... 13

B. The Remedy Does Not Match The Dis

criminatory Purpose Findings............ 19

III. THE COURT OF APPEALS RULING THAT

BECAUSE PLAINTIFFS PROVED THAT

THE BOARD ACTED WITH A DISCRIM

INATORY INTENT, THEY DID NOT

HAVE TO PROVE THE THORNBURG

PRECONDITIONS OR RACIAL NON

RESPONSIVENESS CONFLICTS WITH

DECISIONS OF THIS COURT AND

RAISES IMPORTANT CONSTITU

TIONAL AND STATUTORY QUES

TIONS OF LAW WHICH HAVE NOT

BEEN BUT SHOULD BE SETTLED BY

THIS COURT .............................................. 22

A. The Courts Below Erred As A Matter Of

Law In Their Determination That

Proof Of Racially Discriminatory Ef

fects Of The Sort Required In A Sec

tion 2 Claim Is Not Required In A

Case Alleging Intentional Discrimina

tion ..................... ............................... 23

B. The Courts Below Imposed A Thornburg

Remedy On The Basis Of Non-Thorn

burg Liability, And Consequently The

Remedy Bears Virtually No Relation

ship To And Vastly Exceeds That

Which It Should Have Been Designed

To Rectify 26

V

Page

IV. THE DECENNIAL REDISTRICTING RULE

BARS PLAINTIFFS’ SECTION 2 CLAIM .. 27

Conclusion............................................................................ 30

Appendix...................................................... Appendix Volume

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Ambach v. Norwich, 441 U.S. 68 (1979)....................... 11

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., 429

U.S. 252 (1977) ....................................................... . 19

Bacon v. Carlin, 575 F.Supp. 763 (D.C. Kan. 1983),

affd, 466 U.S. 966 (1984). ......................................... 29

Board of Estimate v. Morris, U.S. , 109 S.Ct 1433

(1989).......................................................................... 9

Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73 (1966)....................... 9, 10

Cabell v. Chavez-Salido, 454 U.S. 432 (1982)............... 11

Carrington v. Rash, 380 U.S. 89 (1965)......................... 10

City o f Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center,

473 U.S. 432 (1985)................................................... 19

City o f Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980)............... Passim

Clark v. Jeter, 486 U.S. 456 (1988)............................... 29

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986)....................... 23

Foley v. Connelie, 435 U.S. 291 (1978)......................... 11

Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F.Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C. 1984),

affd in part, rev 'd in part sub nom.,

Thornburgh v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986).............. 23

Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365 (1971)................. 10

Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections,

383 U.S. 663 (1966)................................................... 10,29

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985) ................. 19

Page(s)

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)............................. 29

McClesky v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987)....................... 23

McMillan v. Escambia County, 638 F.2d 1239 (5th Cir,

1981), cert dism’dsub nom., Pensacola v. Jenkins, 453

U.S. 946 (1981), vacated in part, 688 F.2d 960 (5th

Cir. 1982).................................................................... 16

McNeil v. Springfield Park Dist., 851 F.2d 937 (7th Cir.

1988), cert, denied, U.S. , 109 S. Ct. 1769

(1989).......................................................................... 25

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)..................... 19, 20

Mt. Healthy City School Dist. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274

(1977).......................................................................... 19

Personnel Administrator o f Mass. v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

(1979)........................................................................ Passim

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964)......................... Passim

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)........................... 24

Rybicki v. State Board o f Elections, 574 F.Supp. 1082

(N.D. 111. 1982).......................................................... 17, 18

Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Board o f Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)........................................................ 19,20

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)....................... Passim

WMCA, Inc., v. Lomenzo, 238 F.Supp. 916, (S.D.N.Y.

1965), affd per curiam, 382 U.S. 4 (1965), vacated as

moot, 384 U.S. 887 (1966)..................... 9

WMCA, Inc. v. Lomenzo, 377 U.S. 633 (1964).............. 9

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971)..................... 25

White v. Daniel, 909 F.2d 1042 (5th Cir. 1990)............ 29

White v. Register, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)......................... 24, 25

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973)........................... 16

vii

Page(s)

Page(s)

Winter v. Docking, 373 F.Supp. 308 (D. Kan.

(1974) .................................................................... 9

Wyche v. Madison Parish Police Jury, 769 F,2d 265

(5th Cir. 1985)...................................................... 16

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973), a jf d sub nom., East Carrol Parish School v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976)............................. 23

STATUTES, RULES AND REGULATIONS

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).................................................. 2

42 U.S.C.A. § 1973 (1965) as amended by Act of

June 29, 1982, Pub. L. 97-205 § 3, 96 Stat. 134 .. passim

U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, § 1 .................................. 2,3

U.S. Const. Amend. XV, § 1 ................................... 2,3

California Election Code § 35000 (West 1989)........ 3

California Election Code § 35001 (West 1989)........ 3

California Gov’t Code § 25005 (West 1988) . . . . . . . 3,22

Los Angeles County Charter, Article II, § 7 .......... 3,15,21,22

Vlll

In The

Supreme Court of Qtt)t SJititeb states;

OCTOBER TERM, 1990

COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

YOLANDA GARZA, et al,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners County of Los Angeles and three members of the

Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors (collectively the

“County”) respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari issue to

review the judgment and mandate of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (the “Court of Appeals”) entered

in this proceeding on November 2, 1990.

Opinions Below

The Order of the United States District Court, Central District

of California (David V. Kenyon, District Judge), denying the

County’s motion for summary judgment is unreported and

appears in the Appendix at A-230. The Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law (“Findings”) of the District Court is

unreported and appears in the Appendix at A-50. The Order of

the District Court that sets forth the Remedial Plan is unreported

and appears in the Appendix at A-152. The Order of the Court

2

of Appeals motions panel (Nelson, Beezer, and Kozinski, Circuit

Judges), temporarily granting a stay of the District Court’s initial

injunction order pending oral argument on the County’s stay

application and granting a motion for expedited scheduling of the

appeal is unreported and appears in the Appendix at A-220. The

Order of the Court of Appeals motions panel staying the District

Court’s initial injunction order pending a decision by the Court

of Appeals on the merits is unreported and appears in the

Appendix at A-164. The Order of the Court of Appeals merits

panel (Schroeder, Nelson and Kozinski, Circuit Judges) denying

the County’s request for judicial notice is unreported and appears

in the Appendix at A-194. The opinion of the Court of Appeals

(Schroeder, Nelson and Kozinski, Circuit Judges; Kozinski,

Circuit Judge, concurring and dissenting in part) is reported at

1990 U.S. App. LEXIS 19470 and appears in the Appendix at

A-l. The Order of the Court of Appeals denying the County’s

petition to recall the mandate is unreported and appears in the

Appendix at A-49.1

Jurisdiction

The judgment and mandate of the Court of Appeals was

entered on November 2, 1990. This petition for certiorari is filed

within 90 days of that date. Jurisdiction is invoked under 28

U.S.C. §1254(1).

Constitutional Provisions And Statutes Involved2

The constitutional provisions and statutes involved in this case

include:

i. U.S. Const, amend. XIV, §1.

ii. U.S. Const, amend. XV, §1.

iii. 42 U.S.C. §1973 (1965) as amended by Act of June 29,

1982, Pub. L. 97-205 §3, 96 Stat. 134 (“Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act” or “Section 2”).

1 Concurrently with the filing of this petition, the County has submitted an

application for a recall of the mandate of the Court of Appeals and for a stay

thereof pending a decision on this petition.

2 Pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 14.1(f), the pertinent text of the provisions

cited in this section are set forth in the Appendix at A-358 to A-360.

3

iv. California Election Code §35000 (West 1989).

v. California Election Code §35001 (West 1989).

vi. California Government Code §25005 (West 1988).

vii. Los Angeles County Charter Article II, §7.

Statement Of The Case

This petition arises from two cases challenging the legality of a

redistricting plan adopted by the five-member Los Angeles

County Board of Supervisors (the “Board”) on September 24,

1981. On August 24, 1988, seven years after the 1981 redistricting

plan was adopted, the Garza plaintiffs filed suit, alleging that the

redistricting plan violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

because the district lines fragmented the Hispanic community,

thereby diluting Hispanic voting strength. The Garza plaintiffs

also alleged that the redistricting plan was adopted for a racially

discriminatory purpose in violation of Section 2 and the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution. (Appendix (“App.”) A-58, Findings 9-11). On

September 8, 1988, the United States filed a separate action which

alleged that the redistricting plan violated Section 2. (App. A-58,

Finding 9).

The Board subsequently moved to dismiss the actions on the

grounds of laches and mootness. The Board argued that because

the plaintiff's unreasonably delayed seven years in bringing suit,

and that the Board would soon redistrict following the 1990

census, plaintiffs’ claims should be dismissed. The Board also

moved for summary judgment on plaintiffs’ Section 2 claims on

the basis that demographic evidence unequivocally showed that

it was impossible in 1981 to create a district in which Hispanics

would constitute a majority of eligible voters. Both motions were

denied (App. A-230), and the parties proceeded to trial. On June

4, 1990, the day before the primary election for Supervisorial

Districts 1 and 3, the District Court below found in favor of the

plaintiff's on their Section 2 and constitutional claims. (App.

A-53).

4

In the June 5 primary, incumbent Supervisor Edmund D.

Edelman was reelected to District 3. (App. A-209). In the District

1 contest, ten candidates ran for the office. (App. A-226). Sarah

Flores, an Hispanic candidate, was the frontrunner. She received

35% of the total vote, including 68% of the Hispanic vote and

31% of the nonHispanic vote. Gregory O’Brien polled second

with 20% of the vote. {Id.). Therefore, Ms. Flores and Mr.

O’Brien were scheduled to face each other in a runoff election on

November 6, 1990 in the last election under the 1981 redistricting

plan.

The remedial proceedings commenced before the district

court on July 23, 1990. On August 1, 1990, the district court

rejected the County’s proposed remedial plan (See App. A-197)

and on August 3, 1990, adopted a plan drawn by plaintiffs. (App.

A-216).

On August 6, 1990, the district court entered a permanent

injunction enjoining the November 6, 1990 runoff election for

District 1, setting aside the results from the June 5 District 1

primary, and ordering the County to implement a special primary

election in November under the plaintiffs’ remedial plan. (App.

A-152). On August 16, 1990, a split motions panel of the Ninth

Circuit (Judge Beezer and Kozinski in favor, and Judge Nelson

against) entered a stay of the special election pending resolution

of the merits of the County’s appeal. (App. A-164).

On November 2, 1990, a merits panel of the Ninth Circuit

(Judges Schroeder, Nelson, and Kozinski) entered a decision

which unanimously upheld the district court’s determination on

liability but was divided in upholding the propriety of the remedy

adopted by the district court. (App. A-l). In a carefully reasoned

dissent, Judge Kozinski demonstrated that the remedial plan of

the district court violates the one-person, one-vote doctrine

because, even though all five districts are equal in population, one

district has two to three times more voters and citizens than

another, thereby substantially overvaluing the votes of voters in

one district while undervaluing the votes of voters in other

5

districts. The majority of the merits panel ordered the matter

remanded to the district court and instructed the district court to

schedule a new primary election at the earliest practical

opportunity.

On November 8, 1990, the district court adopted a schedule

under which candidate filing commenced on November 9, 1990,

and a special primary election will be held on January 22, 1991.

(App. A-165). On November 27, the County’s Petition for

Rehearing En Banc was deemed denied.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

This case raises some of the most significant voting rights issues

since the Court’s decision in Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30

(1986).

First, it raises an issue of enormous constitutional significance

which a panel of the Ninth Circuit could not resolve

unanimously, namely whether the one-person, one-vote rule of

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964), requires districts to be

equal in population or equal in citizens (or eligible voters). This

momentous question is important to every political jurisdiction in

the Southwest and elsewhere with large concentrations of

noncitizens.

Second, the intentional discrimination determination not only

conflicts with this Court’s standard for proving intentional

discrimination articulated in Personnel Administrator o f Mass. v.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 256 (1979), but the implications of that

determination are that every redistricting motivated by partisan

considerations or a desire to preserve incumbencies is invalid if it

fails to maximize minority political influence or compensate for

the effects of long past decisions.

Third, this case raises important questions about the scope of

federal district court remedial powers in fashioning redistricting

plans, questions which are especially timely in view of the

imminent release of the 1990 census and the redistrictings and

redistricting litigation that will follow. The district court’s

remedial plan bears no resemblance to its discriminatory purpose

6

findings which would compel a far different remedy. Remedy, in

short, bears little relationship to liability.

Fourth, the Court of Appeals erred as a matter of law in not

requiring proof of the Thornburg effects in a case alleging

intentional discrimination and in imposing a drastic Thornburg

majority district remedy without proof of the Thornburg effects,

in lieu of a more modest remedy commensurate with the

discriminatory purpose findings. The implications of that decision

for vote dilution litigation are staggering because without

Thornburg's effects test there is no way to measure vote dilution,

or to determine whether it was caused by the electoral scheme

under challenge or to draw a remedy bounded by the theory of

liability.

Finally, if the Court of Appeals’ decision affirmed the district

court’s determination that a Section 2 violation was proven on the

basis of post-1980 demographic changes, then it raises the

fundamental constitutional question whether the decennial

redistricting rule established in Reynolds v. Sims should foreclose

a challenge to a redistricting plan valid under Section 2 at the

time it was adopted.

These issues are not settled in Voting Rights Act or equal

protection jurisprudence.

I.

THE REMEDIAL PLAN IS INVALID ON TWO

SEPARATE EQUAL PROTECTION ONE-PERSON,

ONE-VOTE GROUNDS

A. The Remedial Plan Provides Voters in One District with the

Equivalent of Twice as Many Votes as Voters in the

County’s Other Districts

The most compelling basis for reversing the decision of the

Ninth Circuit is discussed in detail in Judge Kozinski’s dissenting

opinion. Essentially, he believed that the district court’s remedial

plan created unacceptable variations in citizens among

supervisorial districts in violation of the one-person, one-vote

principle announced by this Court in Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S.

7

533 (1964), to the point where the value of a vote cast in one

district is over twice the value of a vote cast in another.

The panel majority did not view such variations in citizenship

as constitutionally significant so long as the five districts in the

remedial plan were equal in total population. Judge Kozinski

found the constitutional problems of unequal voting power to be

impermissible, whether or not population parity was achieved. He

was of the view that equality of voting power is constitutionally

primary.

Judge Kozinski carefully summarized the prior Supreme Court

jurisprudence which supports the principle of electoral equality

(creating five districts each equal in the number of citizens) in

preference to the principle of representational equality (five

districts each equal in total population) adopted by the panel

majority. Surely, such a fundamental conflict of constitutional

principles warrants Supreme Court review, particularly where as

here an unprecedented factual situation of enormous political and

social consequence has been presented that will affect imminent

redistrictings in countless political jurisdictions in the Southwest

with large concentrations of noncitizens.

The remedial plan contains five supervisorial districts that are

nearly equal in population. Yet the district court’s August 6

findings reveal that District 1 (the Hispanic District) has nearly

400,000 fewer voting age citizens than District 3, a variance of

40%. (App. A-154). Those findings also reveal that District 1 has

only 366,145 registered voters, while District 5 has over two times

that number, or 835,408 registered voters (App. A-155), a

variance of 70%. (See Ex. 1520, App. A-336). As a result, the

value of a vote in District 1 is worth over twice what a vote in

District 5 is worth and District 1 will control one-fifth of the

Board seats with but one-tenth of the voters in the County.

How is it possible to create districts equal in population but so

unequal in citizens? By packing non-citizens into District 1. It is

undisputed that if one uses either citizenship or voting age

citizenship instead of total population as the apportionment base,

one cannot form a majority Hispanic voting age citizen district

in 1980 or 1990. (Ex. 4151A, App. A-340). That is because only

42% of Los Angeles County’s Latinos age 18 and older are

citizens, compared to 97% of Blacks and 95% of Whites. Latinos

were 27.6% of the County’s population in 1980 but only 14% of

its citizens. Hispanic total population therefore is not a good

measure of the distribution of Hispanic voting age citizens.

Hispanic voters and citizens, moreover are residentially dispersed

throughout Los Angeles County in a nonrandom manner.

Essentially, those who are citizens and eligible to vote do not live

where most immigrant, noncitizen Hispanics live. For example,

67% of Spanish origin registered voters live in precincts which

are less than 40% Spanish origin. (Ex. 5540, App. A-337).

Hispanic citizens, in other words, are distributed quite differently

from Hispanic persons.

The remedial plan, in effect, burdens the right to vote of

citizens in other districts to benefit citizens in District 1, by

concentrating people in District 1 who legally are not entitled to

vote. This distributes political power on the basis of the presence

o f noncitizens, a criterion unrelated to and in fact at odds with

the exercise of that franchise by the only people entitled to

exercise that franchise—citizens. This is crucial to understand—

plaintiffs are claiming a right to a district packed with Hispanic

noncitizens who are not even covered by Section 23 * to ensure an

Hispanic voting age citizen majority that otherwise cannot be

created in 1980 or in 1990.

Reynolds clearly commands rejection of such districts:

And, if a State should provide that the votes o f citizens in one

part of the State should be given two times, or five times, or

10 times the weight of votes of citizens in another part of the

State, it could hardly be contended that the right to vote of

those residing in the disfavored areas had not been effectively

diluted.

3 Section 2 only protects “members of the electorate,” i.e., citizens. Thus, while

Section 2 authorizes packing of Hispanic citizens into a district, within the limits

of the one-person, one-vote rule, it does not authorize the packing of non

citizens.

9

377 U.S. at 562, see also at 566-67 (“The basic principle of

representative government remains, and must remain unchanged

—the weight of a citizen’s vote cannot be made to depend on

where he lives.”). And more recently in Board o f Estimate v.

Morris, the Court stated: “The personal right to vote is a value in

itself, and a citizen is, without more and without mathematically

calculating his power to determine the outcome of an election,

shortchanged i f he may vote for only one representative when

citizens in a neighboring district, o f equal population, vote for two-,

or to put it another way, if he may vote for one representative

and the voters in another district half the size also elect one

representative.” U.S. , 109 S.Ct. 1433, 1440, (1989)

(emphasis added).

The Supreme Court, moreover, has made clear that citizenship

is a permissible apportionment base and that a state need not

include aliens in the apportionment base.5 In Burns v. Richardson,

384 U.S. 73 (1966), for example, the Court stated:

Neither in Reynolds v. Sims nor in any other decision has this

Court suggested that the States are required to include aliens,

transients, short-term or temporary residents, or persons

denied the vote for conviction of crime, in the apportionment

base by which their legislators are distributed and against

which compliance with the Equal Protection Clause is to be

measured.

384 U.S. at 92.6 In Burns, while the Court made clear that states

are not required to include “aliens,” among others, in the

apportionment base, it declined to rule that they must be

5 See WMCA, Inc. v. Lomenzo, 377 U.S. 633 (1964) (upholding New York’s

state constitution which apportioned on the basis of citizenship); see also

WMCA, Inc. v. Lomenzo, 238 F. Supp. 916 (S.D.N.Y. 1965), expressly

upholding citizenship as the apportionment base, ajfd per curiam, 382 U.S. 4

(1965) (Justice Harlan referred to lower court decision as “eminently correct”),

vacated as moot, 384 U.S. 887 (1966) and discussion in Burns, 384 U.S. at 91

(such an apportionment “presented problems no different from apportionments

using a total population measure”); see also Winter v. Docking, 373 F. Supp. 308

(D. Kan. 1974) (upholding Kansas agricultural census which excludes aliens).

6 “While Burns does not, by its terms, purport to require that apportionments

equalize the number of qualified electors in each district, the logic of the case

(Footnote continued on following page)

10

excluded, because that decision “involves choices about the

nature of representation with which we have been shown no

constitutionally founded reason to interfere.” 384 U.S. at 92.

Immediately thereafter the Court stated that choices about the

apportionment base are sometimes constrained by the

Constitution, citing Carrington v. Rash, 380 U.S. 89 (1965) as an

example. Id. The Burns Court did not address the question

whether or when the Reynolds right itself, a citizen’s right to

undebased voting, might itself provide such a constitutional

constraint on apportionment base choices, because that issue was

not before the Court. This, of course, is the issue before the Court

in this case.7

(Footnote continued from previous page)

strongly suggests that this must be so . . . . [I]n a situation such as ours—as

that in Burns—one or the other of the principles must give way. If the ultimate

objective were to serve the representational principle, that is to equalize

populations, Burns would be inexplicable, as it approved deviations from strict

population equality that were wildly in excess of what a strict application of that

principle would permit.” (footnote omitted) Kozinski, Dissenting Opinion

(App. A-39).

7 Judge Kozinski correctly noted in his dissenting opinion that “[w]hen

considered against the Supreme Court’s repeated pronouncements that the right

being protected by the one-person, one-vote principle is personal and limited to

citizens, [the majority’s arguments] do not carry the day.” (App. A-40). Indeed,

the majority decision is deeply flawed and in fact implicitly rests on the

invention of a new and heretofore unrecognized right, a right all people

evidently hold to “equal representation.”

This Court has long recognized that “the right to vote in state elections is

nowhere expressly mentioned” in the Constitution, Harper v. Virginia State

Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663, 665 (1966). Nor has the Supreme Court ever

recognized any implied equal representation constitutional right. Indeed, such a

right is inconsistent with the only voting right that the Supreme Court has

implied, namely the “equal right to vote.”

Supreme Court decisions virtually exclude the possibility of any such implied

right. Noncitizens are strongly protected against discrimination because ever

since Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365 (1971), state and local governments

have been barred from discriminating against them in the distribution of

economic benefits. Exactly the opposite is true, however, with regard to

discriminations for the purpose of defining state or local political communities.

For example, in holding that New York could bar noncitizens from employment

as state police personnel the Court recognized that the states had an “historical

power to exclude aliens from participation in its democratic political

institutions, as part of the sovereign’s obligation to preserve the basic concept

(Footnote continued on following page)

11

B. The Court of Appeals Majority Incorrectly Assumed that

there Was No Way to Harmonize Representational Equality

and Electoral Equality

Even using total population as the apportionment base, it is

undisputed that plaintiffs could have created five districts equal

in population but without such gross variances in citizens and

registered voters. (RT 3/15/90 at 4-20, App. A-318). Of course,

had they done so, Latinos would not be a majority of the voting

age citizens in any district even today and they would not be able

to meet Thornburg’s geographic compactness condition. Use of

harmonizing criteria, then, would have necessitated dismissal of

plaintiffs’ Section 2 claim and a far less drastic remedy for the

intentional discrimination determination than the Thornburg

majority district remedy imposed by the district court.

The County had attacked the district court remedial plan on

two separate equal protection one-person, one-vote grounds:

(i) That where total population is a poor predictor

statistically of the distribution of citizens as in the present

case, citizenship—not total population—is the

constitutionally required apportionment base for one-person,

one-vote purposes. This is the clash between electoral and

representational equality discussed in section I. A, supra-, and

(ii) That the reapportioning body (here the district court)

is constitutionally obligated at least to attempt to satisfy both

aspects of the one-person, one-vote doctrine, i.e., if utilizing

districts equal in population, it must minimize variances in

citizens and in voters to the extent possible.

(Footnote continued from previous page)

of a political community.” Foley v. Connelie, 435 U.S. 291, 295-96 (1978). The

Court reiterated this point in Cabell v. Chavez-Salido, 454 U.S. 432 (1982), in

upholding a California law requiring that “peace officers” be citizens, and in

Ambach v. Norwich 441 U.S. 68 (1979), in upholding a Connecticut law

requiring that public school teachers be citizens. It is frankly unimaginable that

the Supreme Court, having held that state and local governments can

disenfranchise noncitizens and bar them from elective and many appointive

offices, would find that noncitizens nonetheless have an implied constitutional

right to equal representation.

12

The district court did not address this issue at all. Neither did

the Ninth Circuit majority opinion. Judge Kozinski would have

remanded to see if it is possible to reconcile both the interests of

electoral and representational equality—to construct a remedy

where districts are equal in population and with less variance

among citizens. (App. A-46 to A-48).

The Ninth Circuit’s opinion, therefore, appears to be based on

a false assumption—that there is a conflict between the two

interests when in fact there may not be. Thus, there is an

alternative not considered by the panel majority which permits

the Court to avoid the need to select which aspect of the one-

person, one-vote doctrine is constitutionally preferred—the lower

court should be instructed to comply with both. There is no

reason why the lower court could not fashion a remedial plan in

which each district contains at least roughly equal numbers of

people and people eligible to vote. Only Judge Kozinski

acknowledged this possibility. The majority nowhere discusses

what its decision would be if it were not forced to choose between

the two prongs of the one-person, one-vote standard.

II.

THE COURT OF APPEALS RULING THAT THE BOARD

OF SUPERVISORS INTENTIONALLY DISCRIMINATED

AGAINST HISPANICS CONFLICTS WITH DECISIONS

OF THIS COURT AND RESTS ON IMPORTANT

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY QUESTIONS OF

LAW WHICH HAVE NOT BEEN BUT SHOULD BE

SETTLED BY THIS COURT

The district court acknowledged that the Board did not act

with any racial animus or hostility when it adopted the 1981

redistricting plan under challenge here. In fact, the Board tried

to create a more Hispanic district in 1981 but could not do so

because of a partisan political stalemate. Four votes were required

to enact a plan and the Board was split 3-2 along Conservative-

Liberal, Republican-Democratic lines. The Republicans wanted

13

to make District 3, which already was Democratic, more

Hispanic. The Democrats tried to make the Republican districts

more Hispanic and hence more Democratic because

concentrating them in District 3 would not have changed the

balance of power. When they could not agree on a plan, the Board

simply reenacted the existing lines adopted in 1971, with minor

changes.

The district court’s conversion of this political stalemate into

intentional discrimination, despite exonerating findings, was a

clear error of law which resulted from the use of an erroneous

definiton of invidious intent. The importance of, and uncertainty

surrounding, the question of what the elements are of a racially

discriminatory purpose, the application of those elements to a

situation involving non-action and race-neutral partisan political

objectives, and the proper relationship between a discriminatory

purpose finding and the remedy ordered, warrant certiorari in

this case.

A, The Courts Below Applied an Erroneous Definition of

Invidious Intent to a Redistricting Plan Containing No

Change in Boundaries Admittedly Adopted Without Racial

Animus in Circumstances Where the Hispanic Community

Disavowed Interest in a Concentrated Hispanic District

The district court determined that the Board intended to

discriminate against Hispanics in the 1981 redistricting, not

because of any desire on the part of the Board to harm Hispanics,

but because the result of the Board’s protection of incumbents

and political philosophies was the Board’s failure to take

affirmative action to create a majority Hispanic district in total

population: “It was not because of a desire on anyone’s part to

dilute or diffuse or to keep the Hispanic community powerless; it

was because they could not find the way to do what everyone

wanted to do. And that sometimes happens in politics.” (App.

A-55; see also App. A-83 to A-84, Findings 175-181).

The district court’s finding that the Board discriminated

against Hispanic interests, even though it had no desire to harm

14

those interests, evidences a misunderstanding of the

constitutional definition of invidious intent set forth by the Court

in Personnel Administrator o f Mass. v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

(1979), and City o f Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980). In those

decisions, the Court rejected a definition of invidious intent “that

a person intends the natural and foreseeable consequences of his

voluntary actions,” Feeney at 278, and held that:

‘Discriminatory purpose,’ however, implies more than intent

as volition or intent as awareness of consequences. . . . It

implies that the decisionmaker . . . selected or reaffirmed a

particular course o f action at least in part Because o ff not

merely ‘in spite o ff its adverse effects upon an identifiable

group. . . .

442 U.S. at 278 (citations omitted) (emphasis added).

The district court’s finding that the Board acted for a

“discriminatory purpose” is not a finding of the sort that Feeney

and Mobile require, because it is not a finding that fragmentation

of the Hispanic Core or dilution of Hispanic voting strength was

a desired consequence or goal of the 1981 redistricting. The court

found that the Board in 1981 approached redistricting with

exactly the opposite racial “objective” in mind, that is “to protect

their incumbencies while increasing Hispanic voting strength.”

(App. A-54 to A-55).

The Hispanic community in 1981, moreover, opposed—indeed

attacked—any proposal to focus the Hispanic population in a

single district. (RT 1/3/90, at 67-73, App. A-271; RT 1/10/90,

at 147-48, App. A-278; App. A-78, Finding 148). Instead,

Hispanic leaders proposed a “non-negotiable plan” in which

there would be one 50 percent Hispanic and one 42 percent

Hispanic district in total population. (App. A-78, Finding 149;

RT 1/4/90, at 193-94, App. A-281). The representatives of the

Board responsible for proposing a plan, however, could not

achieve consensus on any such plan. The plan proposed by the

Hispanic community threatened to lower the Republican

registration in the First Supervisorial District significantly (thus

threatening the ouster of a “conservative” by a “liberal”). (RT

15

1/3/90, at 22-23, App. A-269; App. A-80 to A-81, Findings 157-

58). The alternatives proposed by the representatives of the

conservatives on the Board were unacceptable to other members

of the Hispanic community (although they increased Hispanic

registration in the Third District and had minor effects on the

Hispanic percentage in the First District), and to the Board’s

liberal minority (which perceived the proposals as reducing their

ability to influence the other members of the Board). {Id.-, RT

1/8/90, at 124-32 App. A-284; App. A-76, A-79, A-81, Findings

138, 151, and 159). Because the County Charter required four

votes out of five in order to amend the district lines, the political

stalemate resulted in but minimal change: only what was needed

to equalize population. (App. A-82, Finding 172).

This evidence led the district court to the fundamental, but

unremarkable, finding that the preexisting “fragmentation”8 * of

the Hispanic community under the status quo plan ultimately

adopted in 1981 was not cured in 1981 because of a political

stalemate. As the County argued, and the district court found, no

change in the political boundaries could be agreed on because all

of the ambitious redistricting plans threatened to change the

political balance of power, not by electing an Hispanic or

avoiding the election of an Hispanic, but by replacing an Anglo

Republican with an Anglo Democrat or by diluting Republican

or Democratic influence. (App. A-55).

The importance of the distinction adopted by the trial court

between incumbency-protection that is tied to the quest to obtain

or maintain partisan advantage and incumbency-protection

which seeks to prevent the election of racial or ethnic minorities

who have a partisan outlook in common with the Anglo

8 With regard to the pre-1981 findings, neither the district court nor the

appellate panel explained how they were relevant to the 1981 plan—the only

districting at issue. What happened in these early years is obviously only the

most tenuous evidence of the Board’s purpose in 1981, since, among other

matters, it was a different board. The pre-1981 findings might be relevant if their

effects were perpetuated in the 1981 districting. The problem is that the district

court made no finding that any of these early acts of discrimination exerted

causal effects that significantly influenced events in 1981.

16

incumbents hardly can be overstated—the former is not

illegitimate.10

Notwithstanding its clear determination that the district lines

of 1971 could not be changed in 1981 because of a race-neutral

political stalemate, the district court also adopted a legal

conclusion that the inability to act, which was the consequence

of such political considerations, could not justify the failure to

cure the fragmentation of the Hispanic community which existed

in 1981. (App. A-55). In its detailed Findings, the district court

adopted a number of proposals of the plaintiffs which warp this

finding of a political stalemate into some kind of intentional effort

to disadvantage Hispanics. Some of the formulations are quite

remarkable doublespeak: A political stalemate is not inaction, it

is an intentional effort “to avoid the consequences of a

redistricting plan designed to eliminate the fragmentation of the

Hispanic population.” (App. A-83, Finding 174.) (There is no

finding, of course, that the consequences to be avoided were

Hispanic empowerment or greater Hispanic influence.)

Recognition that the status quo was the only option became an

“awareness” and thus an “intention” to continue the

fragmentation of the Hispanic Core and the dilution of Hispanic

voting strength. (App. A-84, Finding 181.) (There is, of course,

no finding of a desire to continue Hispanic fragmentation or to

adversely impact Hispanic political participation. Indeed, the

evidence confirmed that the major participants in 1981 all sought

to create an Hispanic district but could not find a consensus

which accomplished that objective. (App. A-76, A-79, Findings

133, 151, 152 and App. A-54 to A-55)

Feeney and Mobile require reversal here because the district

court expressly found that racial animosity played no part in the

adoption of the 1981 plan: “ ‘It was not because of a desire on

anyone’s part to dilute or diffuse or to keep the Hispanic

10 See Wyche v. Madison Parish Police Jury, 769 F.2d 265, 268 (5th Cir. 1985);

McMillan v. Escambia County, 638 F.2d 1239, 1245 (5th Cir.), cert dism’d sub

nom., Pensacola v. Jenkins, 453 U.S. 946 (1981), vacated in part, 688 F.2d 960

(5th Cir. 1982); see also White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973).

17

community powerless.’ ” (App. A-55). This was a struggle

between political ideologies as the district court determined as a

finding of fact. While litigants are allowed to prove invidious

intent with a large variety of inferential evidence,11 the inference

that the board desired to harm Hispanic interests because such

harm inevitably resulted from the Board’s decision cannot

succeed here because the district court determined that no such

intent existed.12

In upholding the district court’s intentional discrimination

ruling, the Court of Appeals relied heavily on finding 181:

“The Supervisors appear to have acted primarily on the

political instinct of self-preservation. The Court finds,

however, that the Supervisors also intended what they knew

to be the likely result o f their actions and a prerequisite to self

11 The Feeney Court observed that:

This is not to say that the inevitability or forseeability of consequences of a

neutral rule has no bearing upon the existence of discriminatory intent.

Certainly, when the adverse consequences of a law upon an identifiable

group are as inevitable as the gender-based consequences [here], a strong

inference that the adverse effects were desired can reasonably be drawn. But

in this inquiry—made as it is under the Constitution—an inference is a

working tool, not a synonym for proof. When, as here, the impact is

essentially an unavoidable consequence of a legislative policy, that has in

itself always been deemed to be legitimate, and when, as here, the statutory

history and all of the available evidence affirmatively demonstrate the

opposite, the inference simply fails to ripen into proof.

442 U.S. at 279 n. 2 (alternations added).

12 The district court was of the understanding that the preservation of

incumbencies was a “form of discrimination” if it impeded an enhancement of

minority voting strength. (App. A-148). In support of this position, the district

court cited Rybicki v. State Board o f Elections, 574 F.Supp. 1082, 1109 (N.D.

111. 1982). This citation is the ultimate illustration of the district court’s

misperception of the meaning of invidious intent. In Rybicki, the district court

considered the preservation of incumbencies as one piece of circumstantial

evidence supporting the Crosby plaintiffs’ claim of intentional discrimination.

574 F.Supp. at 1110. The Rybicki court, however, relied on additional evidence

that showed, through the weight of collective inferences, that the purpose of the

redistricting was to harm the ability of blacks to elect a candidate. 574 F.Supp.

at 1092. The district court here, in other words, confused the definition of intent

with the means of proof.

(Footnote continued on following page)

18

preservation—the continued fragmentation of the Hispanic

Core and the dilution of Hispanic voting strength.”

If the words in this finding mean what they seem to mean—

that the Board intended Hispanic vote dilution because it “knew”

that would be the “likely result” of its action—this finding is

clearly inadequate as a matter of law to support an intentional

discrimination conclusion. It equates intent as volition with intent

as a goal or desired consequence, in clear contravention of Feeney

and Mobile.

The court’s interpretation of finding 181 not only reads it to

mean something other that what it says, but also reads it in a way

that is simply inconsistent with other parts of the district court’s

opinion which exonerated the Board of any charge of purposeful

discrimination. Thus, the district court concluded that the Board

adopted the 1981 plan “not because of a desire on anyone’s part

to dilute or diffuse or to keep the Hispanic community

powerless,” and further that “had the Board found it possible to

protect their incumbencies while increasing Hispanic voting

strength, they would have acted to satisfy both objectives.”13

Read fairly, these findings together with 181 simply exonerate

the Board under Feeney and Mobile: They say that the Board had

(Footnote continued from previous page)

Unlike Rybicki, in which an Anglo Democrat sought to preserve his

incumbency against the challenge of a black Democrat by a change in the status

quo to a more Anglo district, the district court in this case found that the Board

through stalemate did nothing, essentially leaving the lines from 1971 in place.

The effect was not to protect an Anglo against a minority of the same party but

rather against an Anglo of a different political philosophy. The distinction

between this case and Rybicki is that the district court expressly found no intent

to harm Hispanic interests, whereas in Rybicki the district court found an intent

to dilute black voting strength.

13 The courts below erred in ruling that the Board’s action, though not taken

out of racial prejudice, animosity or hostility, was nonetheless taken for a

racially discriminatory purpose. A “discriminatory purpose” under the Equal

Protection Clause is one that reflects racial prejudice, antipathy, hostility or

racism. This is the concept embodied in the proposition often repeated that the

clause prohibits only racially “invidious” actions, and its operational meaning

is that plaintiffs must prove that the Board acted to dilute Hispanic voting

strength because it thought them less worthy or deserving than others.

(Footnote continued on following page)

19

knowledge of the effects of the plan on Hispanic voting strength

but did not act for the purpose of bringing about these effects14.

B. The Remedy Does Not Match the Discriminatory Purpose

Findings

In this case the remedy ordered by the district court and

affirmed by the Court of Appeals bears only a limited relationship

to the acts of intentional discrimination on the basis of which the

Board was held liable,15 in violation of this Court’s longstanding

constitutional remedial jurisprudence that the scope of the

remedy is determined by the nature of the liability.

(Footnote continued from previous page)

Perhaps the clearest explanation of the invidiousness requirement is in City

o f Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, 473 U.S. 432 (1985), where the court, in

rejecting the argument that “mental handicappedness” was a suspect

classification, explained the basis of the rule that racial classifications are

suspect: “[S]uch considerations are deemed to reflect prejudice and antipathy—

a view that those in the burdened class are not as worthy or deserving as others.”

(emphasis added) 473 U.S. at 440.

14 Because there was no such evidence, the Court of Appeals erred in ruling

that the Board’s racially discriminatory purpose, if any, was the cause of its

adoption of the 1981 redistricting plan. The causative purpose rule of Arlington

Heights, supra, and Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985) is not applicable

in this case. See also, Mt. Healthy City School Dist. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977).

That rule was developed to deal with cases in which the plaintiff succeeded in

proving that one of the desired effects or goals or objectives of a governmental

action was discriminatory but one or more other goals were not, In such a case

the burden shifts to the governmental agency charged with discriminating to

prove by a preponderance of the evidence that it would have taken the same

action quite apart from the discriminatory purpose. 429 U.S. 270-271, n. 21.

The causative purpose rule is not applicable in this case because the plaintiffs

have failed to prove that one of the Board’s desired effects, goals or objectives

in the 1981 redistricting was to fragment Hispanics or dilute their vote. They

have proven only that the Board acted for a legitimate goal, preserving

incumbencies, with knowledge of the racial consequences. This proof is not

sufficient to invoke the causative purpose rule for the obvious reason that the

Board did not act for two purposes: it acted for one entirely legitimate purpose.

15 The Court’s two major cases addressing the remedial authority of federal

courts are Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971) and Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974), both school desegregation

cases. The Swann Court stressed that while judges are given discretion in

(Footnote continued on following page)

20

The Board was found to have intentionally discriminated

against Hispanics in four redistrictings: 1959; 1965; 1971; and

1981. Neither of the courts below explained how the first three

redistrictings related to the Board’s liability for the 1981

redistricting, which was the only one ever challenged.

Presumably, the implicit theory of the courts below was that the

discriminatory effects of those redistrictings were perpetuated

because of the 1981 redistricting stalemate. Even assuming,

however, that the 1981 redistricting did perpetuate

discriminatory effects produced by these prior redistrictings, the

remedy ordered by the court goes substantially beyond what

would be required by the discriminatory intents of these pre-1981

redistrictings or the cumulative discriminatory effects

(assumedly) produced by all three of them combined.

In finding 112 (App. A-72) the district court found that,

the Board has redrawn the supervisorial boundaries over the

period 1959-1971, at least in part, to avoid enhancing

Hispanic voting strength in District 3, the district that

historically had the highest proportion of Hispanics . . . .

Although the court found discriminatory intention in the

redistricting of District 3, the court-ordered remedial plan makes

District 1, not District 3, the Hispanic district. This can neither

be explained nor justified by a theory that discriminatory effects

of the 1959-1971 redistrictings were either perpetuated or for that

matter aggravated by the 1981 redistricting. How can a District

1 remedy be a responsive cure to the acts with respect to District

3 that were the basis of liability? *

(Footnote continued from previous page)

imposing equitable remedies, their powers only may be exercised on the basis of

a constitutional violation and “with any equity case, the nature of the violation

determines the scope of the remedy.” Swann, 402 U.S. at 16. Milliken provides

an example of a remedial order that violated the principles established in Swann.

The Court noted that “controlling principle consistently expounded in our

holdings is that the scope of the remedy is determined by the nature and extent

of the constitutional violation.” Milliken, 418 U.S. at 744. It also noted that “the

remedy is necessarily designed, as all remedies are, to restore the victims of

discriminatory conduct to the position they would have occupied in the absence

of such conduct.” 418 U.S. 717, 747.

21

The County is not quibbling with details of the remedy: Of

course district courts need some degree of discretionary flexibility

in fashioning remedies in these complex cases. But this is not the

problem here. The court simply created the remedial Hispanic

district in a different one than was the basis of its liability finding.

Moreover, if it is pre-1981 behavior that is to be remedied in

part, then one would not make District 1 the Hispanic district but

District 3, which was the District affected by that behavior, not

District 1. Given that the 1981 redistricting was the result of non

action rather than action, the remedial plan of the district court

can be upheld only if it represents a plan that would have been

adopted at some earlier time but for the purportedly improper

decisions by which the Board is said to have discouraged

Hispanic challengers from running in the Third District. That

being so, the first aspect of the lower court’s plan—placing the

Hispanic seat in the First District—patently exceeds the remedial

power of the court. There is not the slightest evidence that the

Board would have moved Hispanics from the Third to the First

District but for its improper motive. The court’s plan, in fact,

includes areas never proposed for addition to the most Hispanic

district and excludes areas which used to be in the district but

which were never proposed to be excluded. This exercise confirms

the fact that the district court’s remedy is considerably more than

a remedy for the incumbency-protection which the district court

condemned. It is a remedy which makes District 1 the Hispanic

district, not because that would remedy the effects of past

discrimination (incumbency protection), but for the altogether

affirmative purpose, unrelated to the liability findings, of ensuring

Hispanic success by devaluing the votes of 90% of the County’s

citizens in the other four districts.

The district court’s rejection of the County’s proposed remedial

plan, therefore, was highly inappropriate because it in fact made

District 3 the Hispanic district. Nor were four votes required to

enact it as the Court of Appeals held.17 (App. A-24)

17 The four-vote County Charter requirement only applies to redistrictings after

a decennial census and “within one year after a general election.” (App. A-360)

(Footnote continued on following page)

22

III.

THE COURT OF APPEALS’ RULING THAT BECAUSE

PLAINTIFFS PROVED THAT THE BOARD ACTED WITH

A DISCRIMINATORY INTENT, THEY DID NOT HAVE

TO PROVE THE THORNBURG PRECONDITIONS OR

RACIAL NONRESPONSIVENESS CONFLICTS WITH

DECISIONS OF THIS COURT AND RAISES IMPORTANT

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY QUESTIONS OF

LAW WHICH HAVE NOT BEEN BUT SHOULD BE

SETTLED BY THIS COURT.

The County contended below that plaintiffs’ intentional

discrimination claim must fail because plaintiffs were obliged to

prove both discriminatory purpose and discriminatory effects

which are the same as the three effects established as a threshold

precondition to a successful Section 2 claim in Thornburg. It is

undisputed that a compact district with an Hispanic voting

majority could not have been created in 1981. Thus, the 1981

redistricting plan did not violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act under the criteria established in Thornburg at the time it was

adopted.

The Court of Appeals, however, held that, in a case where

discriminatory intent is proven, the Thornburg preconditions

need not be established so long as the challenged districting

produced some racially discriminatory effects. It further held that

the 1981 redistricting challenged here did produce some

discriminatory effects less than the Thornburg effects but

nonetheless affirmed a Thornburg majority district remedy.

There are two problems with the Court of Appeals’ ruling.

First, the court erred as a matter of law in not requiring proof of

the Thornburg effects in a case alleging intentional

discrimination. If uncorrected, the Court of Appeals’ decision

(Footnote con tinued from previous page)

The two-thirds supermajority requirement did not apply here because the

County’s proposed remedial redistricting plan was not “made within one year

after a general election.” Because the County Charter is silent, state law

controls, which specifies three votes is sufficient. California Govt. Code, Section

25005. (App. A-359) The County’s plan therefore is a valid legislative act.

23

will wreak havoc in future voting rights suits, because it severs

the concept of “vote dilution" from Thornburg’s brightline test

without substituting any criteria at all for measuring when

dilution actually has occurred and whether it has been caused by

the districting scheme under challenge. Second, it renders the

district court’s Thornburg majority district remedy

unsupportable. A far less drastic remedy commensurate with the

discriminatory purpose findings should have been ordered.

A. The Courts Below Erred As a Matter of Law in Their

Determination that Proof of Racially Discriminatory Effects

of the Sort Required in a Section 2 Claim is Not Required in

a Case Alleging Intentional Discrimination

The Supreme Court has made it abundantly clear that the

equal protection clause requires both intent and effect. Davis v.

Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109, (1986); McClesky v. Kemp, 481 U.S.

279, 292 (1987). Proof of the sort of effects required by Thornburg

to maintain a constitutional claim is not reasonably open to

dispute.

Prior to the amendment of Section 2 in 1982, minority vote

dilution cases under the Constitution were successful only where

effective voting majorities could be created.18 Another keystone

of these constitutionally based challenges was proof of racially

polarized voting (which consists of two elements—minority

political cohesion and white bloc voting that usually defeats the

preferred candidate of minority voters). Thornburg, 478 U.S. at

48-51. Indeed, Section 2’s so called Senate factors, which include

polarized voting, derive from minority vote dilution cases under

the Constitution. See Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297, 1305

(5th Cir. 1973), ajfd sub nom., East Carrol Parish School v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976). The effective voting majority and

18 The Thornburg trial court found it “doubtful” that a racial vote dilution

theory could be applied “under any circumstances to smaller aggregations of

voters than those sufficient to make up effective single-member district voting

majorities.” Gingles v. Edmisten, 589 F.Supp. 345, 380-81 (E.D.N.C. 1984),

(Footnote continued on following page)

24

polarized voting requirements, of course, are the same as the

three Thornburg preconditions.

Still another requirement in the pre-1982 intentional

discrimination cases was proof that the jurisdiction under

challenge had been unresponsive to minority interests.19 Here,

plaintiffs made no claim that the County had been unresponsive

to Hispanics and offered no evidence to that effect.

(Footnote continued from previous page)

affd in part, rev’d in part sub nom., Thornburgh v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)

As the Court explained:

There is, first oif, the fact that the principle cases authoritatively

developing the vote dilution concept have involved the impact of

districting upon effective voting majorities. See, e.g., Rogers v. Lodge, 458

U.S. 613 .. . (1982); Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 . . . (1980); White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755 . . . (1973). Confined to such measurable

aggregations, the concept has a principled basis which permits rational and

consistent, albeit sometimes difficult, application; not so confined, it lacks

any such basis. That is to say, at the effective voting majority level it is

possible to say with substantial assurance that to submerge or fracture such

an aggregation in a racially polarized voting situation effectively deprives

it of the presumptive capability to elect, solely by its group voting strength,

representatives “of its choice.” . . . The raw power of such an aggregation

“to elect” provides a clear measure of its voting strength, hence a fair and

workable standard by which to measure dilution of that strength. Short of

that level, there is no such principled basis for gauging voting strength,

hence dilution of that strength. Nothing but raw intuition could be drawn

upon by courts to determine in the first place the size of those smaller

aggregations having sufficient group voting strength to be capable of

dilution in any legally meaningful sense and, beyond that, to give some

substantive content other than raw-power-to-elect to the concept as

applied to such aggregations.

We are doubtful that either the Supreme Court in developing the dilution

concept in constitutional voting rights litigation, or the Congress in

embodying it in amended Section 2 o f the Voting Rights Act intended an

application open-ended as to voter group size. There must obviously be some

size (as well as dispersion) limits on those aggregations o f voters to whom

the concept can properly be applied. We do not readily perceive the limit

short o f the effective voting majority level that can rationally be drawn and

applied.

590 F.Supp. at 381 (emphasis added).

19 In the pre-1982 cases, the Supreme Court recognized that the surest

indication that “vote dilution” is in fact an accurate characterization of a

challenged practice is the existence of nonresponsiveness by the governmental

body at issue to the minority group’s interests. Both White v. Register, 412 U.S.

(Footnote continued on following page)

25

The amendment of Section 2 did not change the proof required

to establish a constitutional claim, nor could it. Section 2

eliminated the need to prove an invidious purpose to prevail on a

Section 2 claim. It did not, however, eliminate or in any way

address the already existing and continuing proof requirements

of a constitutional claim, which already included the three

Thornburg preconditions and nonresponsiveness.

No purpose would be served by having a different “effects” test

to define minority vote dilution in claims under Section 2 than

under the Constitution. Thornburg represents the culmination of

an historical search for standards by which to assess claims of

vote dilution. It established a set of “clear rules over muddy

efforts to discern equity,” that prevent courts from building

“castles in the air, based on quite speculative foundations.”

McNeil v. Springfield Park Dist., 851 F.2d 937, 942-44 (7th Cir.

1988) cert, denied, U.S. , 109 S.Ct. 1769 (1989). Thornburg's

first precondition, for example, is a concrete recognition of the

amorphous nature of claims that voting strength has been

“impaired” or “diluted,” and of the constitutional, statutory and

jurisprudential limitations which surround these claims. The

brightline approach in Thornburg obviously was a response to the

difficulties inherent in trying to assess when a voting system

sufficiently disadvantages a minority group so that a court

confidently can find that it has in fact been denied equal

opportunity to participate in the political process. The difficult

(Footnote continued from previous page)

755, 767-69 (1973) and Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 149-52 (1971), for

example, featured prominent discussions of nonresponsiveness, and this was

largely the basis on which the Mobile v. Bolden Court distinguished White, 446

U.S. 68-70, the only successful pre-1982 challenge to voting district practices by

minority group members to succeed in the Supreme Court.

Nonresponsiveness is an inference that arises from a governmental body’s

treating minority groups less well than others in the distribution of government

services, employment and the like that that body does not need to take into

account the electoral behavior of that minority group. White, 412 U.S. at 767.

Nonresponsiveness is uniquely probative evidence that the allocation of racial

populations among districts is not operating to protect their interests and that

nonelectoral avenues for the exercise of political influence are also not

functioning fairly. In sum, such evidence establishes that a plausible vote

dilution claim really is such.

26

effects assessment problems that underlie Thornburg are just as

real and troublesome in constitutional cases as in Section 2 cases.

The courts below erred as a matter of law by failing to

require proof of discriminatory effects of the sort required by

Thornburg. Consequently, failure to prove a Section 2 violation

in 1981 also requires reversal of the district court’s determination

that the plaintiffs established their intent claims.

B, The Courts Below Imposed a Thornburg Remedy on the Basis

of Non-Thornburg Liability, and Consequently the Remedy

Bears Virtually No Relationship to and Vastly Exceeds that

Which It Should Have Been Designed to Rectify

To warrant the granting of a Thornburg-based majority district

remedy, plaintiffs should have to prove the Thornburg conditions.

The district court’s remedial plan was premised on findings that

the plaintiffs had proven the Thornburg effects in addition to

discriminatory intent, but the Court of Appeals affirmed on the

basis of the latter finding only, holding that proof of the

Thornburg preconditions was unnecessary when discriminatory

purpose was proven. The Court of Appeals nonetheless affirmed

the Thornburg majority district remedy and in so doing it

committed clear reversible error.

Under Swann and Milliken, supra, p. 19, fn. 15, the remedy

should have been tailored to those effects actually caused by the

pre-1981 and 1981 discriminatory redistrictings, which would

have entailed a District 3 remedy with less than a majority

Hispanic voting age citizen district. Instead, plaintiffs were

provided a Thornburg remedy without having to prove

Thornburg liability, a remedy far beyond the effects proven, and

far beyond the scope of the liability determination. Without proof

of the Thornburg preconditions, the remedy ordered here clearly

places the plaintiffs in a better position than they would have

occupied had the Board not engaged in the intentionally

discriminatory acts on the basis of which it has been held liable.

27

THE DECENNIAL REDISTRICTING RULE BARS

PLAINTIFFS’ SECTION 2 CLAIM

It is undisputed that Hispanics could not comprise a majority

of the voting age citizens in any potential district in 1980. The

district court, however, found that such a district could be formed

in 1985 or at least by 1988 and therefore concluded that a Section

2 violation occurred. The County contended that the decennial

redistricting rule of Reynolds v. Sims would foreclose any Section

2 claim if the County’s 1981 redistricting plan was valid when it

was adopted, /.e. , was not the result of discriminatory purpose.21

The Court of Appeals miscomprehended the County’s

argument. The Court of Appeals properly held the decennial

redistricting rule was inapplicable in a case where a finding of

intentional discrimination purpose is made and the County does

not contend otherwise. The Court of Appeals, however, never

addressed whether the rule would foreclose the Section 2 claim if

the intentional discrimination determination is reversed. The

district court determined that single member district systems,

which already are subject to decennial revision under federal,

state and local law, nevertheless may be subjected to more

frequent reapportionment if postcensal demographic evidence

indicates that a minority group which could not form a district

majority at the time a decennial plan was adopted becomes

sufficient in size and concentration to form a majority of the

21 The Court of Appeals’ decision is utterly unclear on whether the post-1980

evidence could be used to form a majority Hispanic district to prove a Section 2

violation. If the decision is to be read as upholding the district court’s finding of

a majority district for purposes of proving a Section 2 violation sometime after

1981, then the panel completely failed to address the second and third

Thornburg preconditions which must be established to prove a Section 2