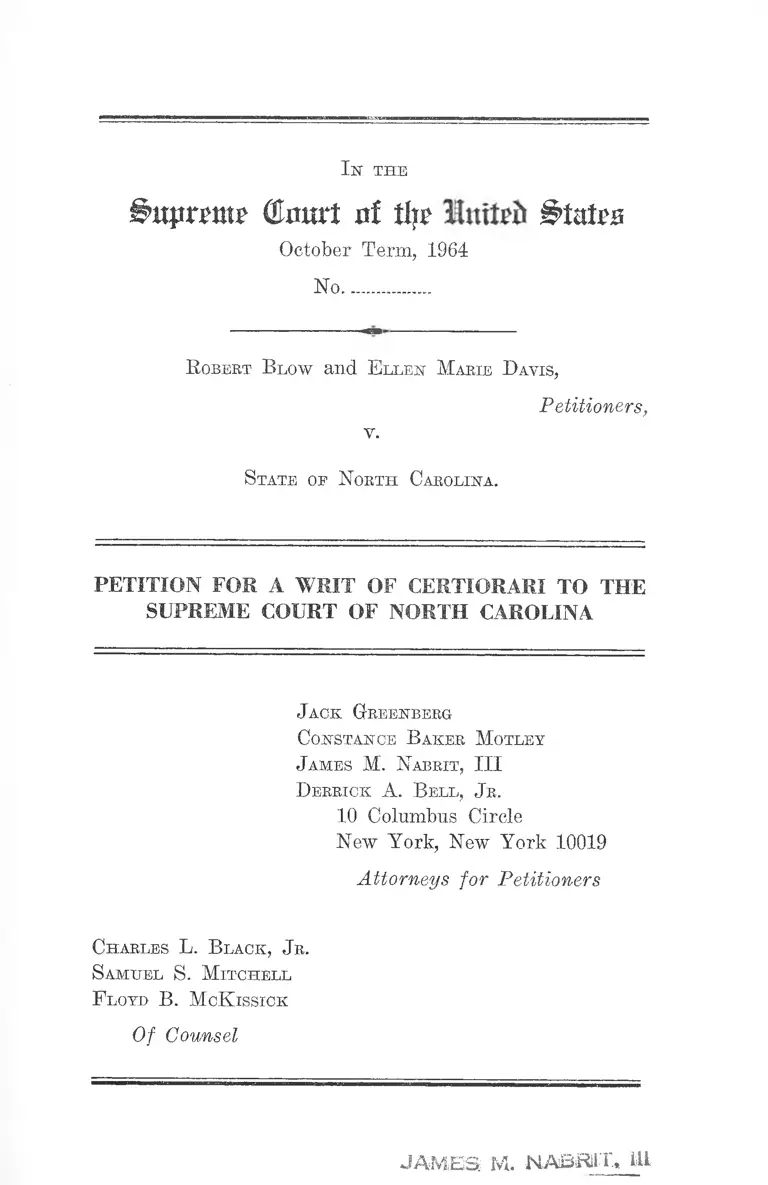

Blow v. North Carolina Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of North Carolina

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Blow v. North Carolina Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of North Carolina, 1964. 708191f8-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/49200cc5-b0df-4cc2-b94f-182d53d2165e/blow-v-north-carolina-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-north-carolina. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

Bnptmw (Hmtt 0! % Stairs

October Term, 1964

No...............

R obert Blow and E llen Marie Davis,

v.

Petitioners,

State op North Carolina.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles L. Black, J r.

Samuel S. Mitchell

F loyd B. McK issick

Of Counsel

J A M E S M. NAlBjFillX., HI

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ................. ....................... 1

Jurisdiction ................................ _........... .......... ..... ...... 1

Questions Presented ..................................................... 2

Constitutional, Statutory and Regulatory Provisions

Involved ......................... 3

Statement ....................................................................... 4

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below .................. .............. ........... ........... ................ 6

Reasons for Granting the Writ ................................... 8

I. The State of North Carolina Has Encouraged

and Enforced Racial Discrimination in Violation

of the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment............................ 9

A. Administrative regulations issued by the

State Board of Health regarding the segre

gation of bathroom facilities in restaurants

involve the State in the discrimination prac

ticed in these cases ................. ..................... 9

B. These convictions enforce and encourage

racial discrimination in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States ....................... 13

11

PAGE

II. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Now Secures to

Petitioners the Right to the Conduct 'Which the

State Seeks to Punish; Therefore,

A. Under federal law, these prosecutions are

abated .......... ................................................. 16

B. These cases, if not reversed outright, should

be remanded to the Supreme Court of North

Carolina for its determination of the abative

effect of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 .. 22

Conclusion ................................................................... 25

Appendix :

Opinion of Supreme Court of N. C. in State v. Ellen

Marie Davis............................................................ la

Opinion of Supreme Court of North Carolina in State

v. Robert Blow ....................................................... 7a

Judgment in State v. Ellen Marie Davis................... 9a

Judgment in State v. Robert Blow ............................ 10a

Certification of Record, State of North Carolina v.

Ellen Marie Davis ................................................. 11a

Certification of Record, State v. Robert Blow .......... 12a

Appendix B :

Statutory and Regulatory Provisions ..................... 13a

Ill

Table of Cases

page

Barr v. Columbia,-----U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d 766 .... 13

Bell v. Maryland, ----- U. S. ----- , 12 L. Ed. 2d

822 .............. .................. ......13,15,18,19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25

Bouie v. City of Columbia,-----U. 8. ------, 12 L. Ed. 2d

894 .................... ................. - ........................ -.......... 13

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 IT. S.

715 .......... ........... -________ _____ _____ ----- ----- 12

Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261 ...... ................-........... 15

Fox v. North Carolina,-----U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d

1032 ..............................- ....- - ........-......-----................ 2,12

Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U. S. (9 Wheaton) 1 (1824) ...... 18

Griffin v. Maryland,----- IJ. S .------, 12 L. Ed. 2d 754 .... 13

Hamm v. Rock Hill, No. 2, Oct. Term 1964, cert.

granted,-----U. S .------, 12 L. Ed. 2d 1042 ..............- 13

Hauenstein v. Lynham, 100 IJ. S. 483 —......... - .......... 22

Lupper v. Arkansas, No. 5, Oct. Term, 1964, cert,

granted,----- IJ. S .------, 12 L. Ed. 2d 1043 ................ 13

Robinson v. Florida, ----- IJ. S. ----- , 12 L. Ed. 2d

711 ............................ ..............-----.......... - ......-11,12,13

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .............-................ .... 14

Sola Elec. Co. v. Jefferson Elec. Co., 317 U. S. 173

(1942) ............-_________ ______________ -........ 18

Sperry v. Florida, 373 U. S. 379 (1963) ......... ........ -..... 18

State v. Broadway, 157 N. C. 598, 72 S. E. 987 (1911) .. 25

State v. Cress, 4 Jones (49 N. C.) 421 (1857) ---------- 23

State v. Foster, 185 N. C. 674, 116 S. E. 561 (1923) .... 24

State v. Long, 78 N. C. 571 (1878) .......~..........- .......—- 23

State v. Massey, 103 N. C. 356, 9 S. E. 632 (1889) ....... 23

IV

PAGE

State v. Moon, 178 N. C. 715, 100 S. E. 614 (1919) . 25

State v. Perkins, 141 N. C. 797, 53 S. E. 735 (1906) _ 25

State v. Putney, 61 N. C. 543 (1866-67) ........................ 25

State v. Williams, 97 N. C. 455, 2 S. E. 55 (1887) . 23

Testa v. Katt, 330 U. S. 386 ______ 1_______ ____ 22

Trustee of Monroe Ave. Church, of Christ v. Perkins,

334 U. S. 813 ............... .............................................. 14

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 .................. ............. 12

United States v. Chambers, 291 U. S. 217 (1934) ___ 18

United States v. Tynen, 78 U. S. (11 Wall.) 88 (1871) .... 18

Williams v. North Carolina,-----U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed.

2d 1032 ..................................... ..... ........... ................ 12

S t a t u t e s

Civil Eights Act of 1964, §§201-203, 78 Stat. 243

244 ........ ............. ............ .....3,14,16,17,18, 20, 21, 25,13a

N. C. Gen. Stat. §12-2 (1953) ................ ...3,23,16a

N. C. Gen. Stat. §12-4 (1953) .... ...3,23,16a

N. C. Gen. Stat. §14-134 (1953) ............................3, 4, 6 ,16a

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-1 (1963) .............. ................3,7,12,16a

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-46 (1953) ............................... ..3, 9 ,17a

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-47 (1953) ........... ........... ........ 3,10,18a

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-48 (1953) ............................. . . .3, 11,18a

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-48.1 (1953) ............................ 3,11,18a

1 U. S. C. §109, 61 Stat. 635 ........... .. .......... ........3,19,15a

Y

Other Authorities

page

House Committee on Civil Rights Aet, H.R. Rep.

No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) ......................— 21

Million, Expiration or Repeal of a Federal or Oregon

Statute as a Bar to Prosecution for Violation There

under, 24 Ore. L. Rev. 25 (1944) ---------......... - .... 20

Report of North Carolina Committee to U. S. Commis

sion on Civil Rights (1962), Equal Protection of the

Laws of North Carolina...... —......................—-.......... H

Test Form 451, revised 1958 of the North Carolina

State Board Health Sanitary Engineering Division,

Law Rules and Regulations Governing Sanitation of

Restaurants and Other Food Handling Establish

ments ............... ......... -.......................- ................. 3, 20a

I n t h e

dhtprem? Qlmtrt of tl)0 Ittttpft States

October Term, 1964

No................

R obert Blow and E llen Marie Davis,

Petitioners,

State of North Carolina.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgments of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

entered in the above-entitled cases on March 18, 1964.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinions of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

are reported at 261 N. C. 463, 135 S. E. 2d 14 (1964), and

261 N. C. 467, 135 S. E. 2d 17 (1964) and are set forth in

the appendix hereto, infra, pp. la, 7a.

Jurisdiction

The opinions and judgments of the Supreme Court of

North Carolina were entered on March 18, 1964, infra,

pp. la, 7a, 9a, 10a. On June 24, 1964, the Chief Justice

2

signed an order extending petitioners’ time for filing peti

tion for writ of certiorari to and including August 15, 1964.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, §1257(3), petitioners having

asserted below and asserting here deprivation of rights

secured by the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Where petitioners, two Negroes, were convicted of

trespass for refusing to leave the property of a North

Carolina restaurateur and motel owner, who refused them

service and demanded that they leave solely because of their

race, were their Fourteenth Amendment rights to due

process and equal protection violated, in that:

(A) The state has encouraged racial discrimination in

restaurants by administrative regulation as in the case of

Fox v. North Carolina,-----U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d 1032,

and by laws denying Negroes rights guaranteed white

persons at inns.

(B) The state enforces racial discrimination by arrest

and prosecution; the discrimination has been caused at

least in part, by a custom of segregation supported by

state law; and the state subordinates petitioners’ claims

of equality in the public life of the community to a narrow

property right.

2. In such a case, are the prosecutions abated by the

passage of the Civil Bights Act of 1964 while these cases

were pending:

(A) as a matter of federal law, or in the alternative

(B) must they be remanded for a decision as to abate

ment under state law.

3

Constitutional, Statutory and Regulatory

Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the following provisions of the

Constitution of the United States:

Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3;

Article VI, paragraph 2;

The Fourteenth Amendment.

2. This case involves the following statutes of the United

States.1

Civil Rights Act of 1964, §§201-203, 78 Stat. 243, 244;

1 U. S. C. §109, 61 Stat. 635.

3. This case involves the following North Carolina Gen

eral Statutes.2

N. C. Gen. Stat. §12-2 (1953);

N. C. Gen. Stat. §12-4 (1953);

N. C. Gen. Stat. §14-134 (1953);

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-1 (1953);

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-46 (1953);

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-47 (1953);

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-48 (1953);

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-48.1 (1953).

4. This case also involves test form 451, revised 1958,

Law Rules and Regulations Governing the Sanitation of

Set forth infra at pp. 13a-16a.

Set forth infra at pp. 16a-19a.

4

Restaurants and Other Food Handling Establishments pre

pared by the North Carolina State Board of Health Sani

tary Engineering Division.3

Statement

Petitioners, two Negroes, were arrested while engaging

in a peaceful protest outside the Plantation Restaurant and

Enfield Motel, Enfield, North Carolina after they had been

denied entry into the restaurant. They were convicted of

“trespass” in violation of North Carolina General Statutes

§14-134, infra p. 16a.

The Plantation Restaurant and the adjoining Enfield

Motel, located on interstate highway 301, are owned by the

complaining witness, Mr. W. R. Davis (D. 15, 18, 19; B. 15,

16, 17).4 He manages the restaurant and his wife the

motel (B. 20). Both places are advertised together along

the highway, on the radio, and in newspapers. The motel

advertises the restaurant in its rooms, and guests from

the motel eat at the restaurant. Air. Davis does not indi

cate in any of these advertisements that the facilities do

not serve Negroes (D. 19, 20; B. 17, 18).

Shortly before noon on August 7, 1963, petitioners, as

part of a group of thirty-five, approached the restaurant at

which they had been denied service the previous evening

(D. 16, 17). Although he knew that they sought service

(B. 21), Mr. Davis locked the restaurant upon petitioners’

approach because of their color (D. 17; B. 21):

“The reason I locked the door was because the defen

dant was a Negro and I am white. The restaurant

3 Set forth infra at pp. 20a-22a.

4 “D” refers to record in Davis v. North Carolina.; “B” refers

to record in Blow v. North Carolina.

5

I operate serves white and not Negroes; that is the

reason I locked the door” (D. 17).

Although Mr. Davis’ property extended out to Highway

301, two “white only” signs (D. 18; B. 21) hanging inside

the front doors were the only indication on the premises

or on the advertisements that Negroes were not welcome

(D. 19; B. 17).

Upon reaching the locked doors, petitioner Davis sat

down ontside the restaurant (D. 15). Mr. Davis took hold

of her shoulder and moved her away from the door (D. 16),

and asked petitioners to leave his grounds (B. 16).

Petitioners were neatly dressed and did not block white

patrons from entering the restaurant (D. 20, 22; B. 21, 24).

Mr. Davis “would open the front door and lock it, admitting

white patrons, while the defendant was outside” (B. 21),

and wanted petitioners to leave his grounds solely because

they were Negro.

“She was neatly dressed and the only reason I asked

her to leave was that she was colored” (D. 18).

Mr. Davis decided to “indict” them for trespass (B. 22),

and officers, who were “well aware of [the] policy of not

serving Negroes” (D. 22), arrived and arrested petitioners

for “trespass” because they refused to leave the property

(D. 20, 21, 22; B. 24). The officers testified that petitioner

Davis was not doing anything except sitting on a planter

(D. 23), and Blow was only standing by the planter, several

feet from the door (B. 23). One arresting officer had in the

past arrested a white man at the restaurant for disorderly

conduct, but no white person has ever been arrested on

the charge of trespass at the restaurant (D. 22, 23).

Petitioners waived preliminary hearings in the Mayor’s

Court and the County Solicitor waived hearing in the

6

Comity Recorder’s Court. The petitioners were tried sep

arately before juries in the Superior Court of Halifax

County (D. 14, 15; B. 14, 15). Petitioners (after raising

constitutional defenses discussed, infra, pp. 6-7), were

convicted of trespass under North Carolina General Stat

utes §14-134 and sentenced to twelve months in jail, the

sentence suspended on the condition they pay the costs,

pay a fine of $250, and violate no laws for a period of three

years (D. 12; B. 12). The Supreme Court of North Carolina

affirmed petitioners’ convictions on March 18, 1964 (infra,

pp. la, 7a).

How the Federal Questions Were

Raised and Decided Below

In the Superior Court of Halifax County, petitioners

moved for judgment as of nonsuit after the reading of the

indictment. In summary petitioners contended North Caro

lina General Statutes §14-134 violated the United States

Constitution as applied to them because:

1) The Fourteenth Amendment prevents a state from

using its criminal law a) to enforce the racially dis

criminatory practices of a private restaurant owner

once that owner has opened his property to the general

public, b) to inhibit the exercise of free speech in a

place opened to the public at large.

2) The Fourteenth Amendment and Article 1, Section

10 of the United States Constitution prevent inter

preting a statute to include conduct which clearly

falls outside the wording of a statute. Such applica

tion makes the statute unconstitutionally vague in fail

ing to give fair warning that conduct is criminal within

the terms of the statute and amounts to retroactive

legislation.

7

3) The statute delegates legislative power and the

power to cause arbitrary and capricious arrests of a

person in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

4) Petitioner is denied the right to contract and the

benefits therefrom as guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment and 42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1982.

5) Failure of the state court to apply N. C. Gen. Stat.

§72-1, “The Innkeepers Rule,” which establishes stand

ards of practice for innkeepers, was a violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

The motions for judgment as of nonsuit were denied

(D. 3-11; B. 3-11). Petitioners pleaded not guilty and were

tried before a jury (B. 11; D. 11).

Following the State’s case, each petitioner again moved

for judgment as of nonsuit. The motions were denied and

exceptions taken (D. 23; B. 25). Petitioners offered no

evidence but again submitted written motions for judgment

as of nonsuit which were denied and exceptions taken

(D. 24; B. 25).

After a guilty verdict, each defendant moved to set the

verdict aside reiterating the contentions set out in the

motions for judgment as of nonsuit. These new motions

were denied and exceptions taken (I). 31; B. 34). .Defen

dants also moved for new trials alleging errors in the

progress of the trial. Motions were denied and exceptions

taken (D. 31; B. 34).

As assignments of error on appeal to the Supreme Court

of North Carolina, petitioners raised the questions pre

sented in the motions for judgment as of nonsuit and

assigned that these motions were erroneously denied (D. 31-

34 ;B. 34-38).

The Supreme Court of North Carolina explicitly rejected

petitioner Davis’ constitutional objections, infra, pp. la-6a,

holding:

that where a person without permission or invitation

enters upon the premises of another, and after entry

thereon his presence is discovered and he is uncon

ditionally ordered to leave the premises by one in the

legal possession thereof, if he refuses to leave and

remains on the premises, he is a trespasser from the

beginning. . . . We further hold that the provisions of

Gf. S. 14-134 do not conflict with Article 1, Section 17

of the Constitution of North Carolina or with the

Privileges and Immunities, Due Process and Equal

Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

Petitioner Blow’s conviction was affirmed per curiam on the

basis of the Davis opinion, infra, pp. 7a-8a.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

This case involves substantial questions affecting im

portant constitutional rights, resolved by the court below

in conflict with principles expressed by this Court.

9

I.

The State of North Carolina Has Encouraged and En

forced Racial Discrimination in Violation of the Equal

Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

A. A d m in is tra tive regula tions issued by the S ta te B o ard o f

H ealth regarding th e segregation o f b a th ro o m facilities in

restauran ts invo lve th e S ta te in th e d iscrim in a tio n prac

ticed in these cases.

Administrative action in the nature of regulations deal

ing with the maintenance of toilet facilities in restaurants

has been in effect in North Carolina at all times pertinent

to this case. Restaurants in North Carolina cannot operate

without attaining the minimum grade of C in accordance

with tests regulated by the State Board of Health. In par

ticular, N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-46 provides: .

State Board of Health to regulate sanitary conditions

of hotels, cafes, etc.—For the better protection of the

public health, the State Board of Health is hereby au

thorized, empowered and directed to prepare and en

force rules and regulations governing the sanitation

of any . . . restaurant . . . The State Board of Health

is also authorized, empowered and directed to

(1) Require that a permit be obtained from said

Board before such places begin operation, said

permit to be issued only when the establishment

complies with the rules and regulations author

ized hereunder, and

(2) To prepare a system of grading all such places

as Grade A, Grade B and Grade C.

No establishment shall operate which does not re

ceive the permit required by this section and the mini-

10

mum grade of C in accordance with the rules and regu

lations of the State Board of Health. The rules and

regulations shall cover such matters as . . . lavatory

facilities . . .

Under this authorization, the State Board of Health ad

ministers an inspection form on the basis of 1000 points

which provides in the relevant passage:

6. T oilet F acilities : Approved facilities and ap

proved disposal 90* (facilities adequate for each

sex and race 10* . . .) (Form No. 451, revised

July 1958, Law, Rules and Regulations Governing

the Sanitation of Restaurant and Other Foodhan

dling Establishments, prepared by the North Caro

lina State Board of Health Sanitary Engineering

Division, at pp. 26-27.5

In addition to the relevancy of these regulations in the

licensing process, statutes provide for the continued in

spection of operating establishments on the basis of the

same test.

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-47.—Inspections; report and grade

card. The officers, sanitarians or agents of the State

Board of Health are hereby empowered and authorized

to enter any . . . restaurant . . . It shall be the duty

of the sanitarian or agent of the State Board of

Health to leave with the management, or person in

charge at the time of the inspection, a copy of his

inspection and a grade card showing the grade of such

place, and it shall be the duty of the management, or

person in charge to post said card in a conspicuous

5 The entire test form is set out infra, pp. 20a-22a. * stands for

points.

11

place designated by the sanitarian where it may be

readily observed by the public.

Violations of these provisions are punishable by fine and

imprisonment, N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-48, and the State Health

Director can sue to enjoin the operation of a restaurant

which does not meet minimum standards. N. C. Gen. Stat.

§72-48-1. See also, Equal Protection of the Laws of North

Carolina, Report of the North Carolina Committee to the

United States Commission on Civil Rights (1962), p. 220.

Recently in Robinson v. Florida, ----- U. S. ——•, 12

L. Ed. 2d 771, involving several Negro persons who re

mained in a restaurant after being asked to leave, this

Court reversed the conviction in light of a regulation re

quiring separate toilet facilities in restaurants. The Court

held,

While these Florida regulations do not directly and

expressly forbid restaurants to serve both white and

colored people together, they certainly embody a state

policy putting burdens upon any restaurant which

serves both races, burdens bound to discourage the

serving of the two races together. Of course, state

action, of the kind that falls within the proscription of

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, may be brought about through the State’s ad

ministrative and regulatory agencies, just as through

its legislature. Cf. Lombard v. Louisiana, supra, 373

U. S. at 273. Here, as in Peterson v. City of Green

ville, supra, we conclude that the State through its

regulations has become involved to such a significant

extent in bringing about restaurant segregation that

appellants’ trespass convictions must be held to re

flect that state policy and therefore to violate the Four

teenth Amendment (at 773, 774).

On the same day, this Court vacated the judgment in a

restaurant demonstration case coming from North Caro-

12

lina, Fox, et al. v. North Carolina, ----- U. S. ——, 12

L. Ed. 2d 1032, after the North Carolina regulation dis

cussed above had been brought to its attention. In a per

curiam opinion, the Court vacated the judgment in light of

Robinson v. Florida, supra; see also Williams v. North

Carolina,-----U. S. ------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d 1032. Fox, et al.

v. North Carolina, therefore, requires that, at the least,

the judgments of the North Carolina Supreme Court in

these cases be vacated.

In addition to the clear State involvement in light of

Fox and Robinson, the State of North Carolina has become

involved in the racial discrimination practiced in these

cases by denying Negroes guarantees of service at inns

afforded white persons. North Carolina statutory law con

fers upon an innkeeper the duty of service.

N. C. Gen. Stat. §72-1—Must furnish accommodations

—Every innkeeper shall at all times provide suitable

food, rooms, beds and bedding for strangers and

travelers whom he may accept as guests in his inn or

hotel.

In the common law tradition, the innkeeper must accept all

wayfarers,

. . . unless they be persons of bad or suspicious char

acter, or of vulgar habits, or so objectionable to the

patrons of the house, on account of the race to which

they belong, that it would injure the business to ad

mit them to all portions of the house . . . Stale v.

Steele, 106 N. C. 766, 11 S. E. 478 (1890).

The laws of North Carolina, therefore, deny equal protec

tion by conferring on white persons rights which are not

afforded Negroes. See: Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350,

352; Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S,

715, 726-727 (concurring opinion).

13

Mr. Davis, the complaining witness, owned both restau

rant and motel. Although the trial judge excluded testi

mony about the interconnections of the two establishments

(D. 19; B. 18, 19, 20), the record clearly states that Mr.

Davis’ motel and restaurant are 60 feet apart on the same

lot of ground and operated together (D. 15, 16, 17, 18, 19;

B. 15, 19). The Supreme Court of North Carolina rejected

the argument on the grounds (1) that petitioners sought

service at the restaurant and not at the motel and (2) that

the motel was managed by Mrs. Davis while the restaurant

was managed by Mr. Davis, infra at p. 5a. But the restau

rant is operated to a significant extent in cooperation with

the motel. Quests at the motel are encouraged to eat at the

restaurant and some of them do (D. 20; B. 18). If the in

fluence of state policy is felt in Mr. Davis’ motel, that in

fluence would reasonably extend to his operation of the

restaurant. Robinson v. Florida, ----- IT. S .------ , 12 L. Ed.

2d 771.

B. T h ese convictions en fo rce and encourage racial d iscrim ina

tio n in v io la tion o f the F o u rteen th A m e n d m e n t to the

C o nstitu tion o f th e U nited States.

This petition presents issues identical to those presented

to this Court in Barr v. Columbia, -----U. S. ——, 12 L. Ed.

2d 766; Bell v. Maryland, ----- U. S. ----- , 12 L. Ed. 2d

822; Bouie v. City of Columbia, —— IT. S .----- , 12 L. Ed.

2d 894; Griffin v. Maryland,-----U. S. ------, 12 L. Ed. 2d

754; Robinson v. Florida,-----U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d 771.

Each of these state convictions was reversed on grounds

other than the “state action” issue presented. The same

issue is now pending decision before this court in two other

cases involving convictions for trespass at places of public

accommodation: Hamm v. Rock Hill, No. 2, October Term

1964, petition for cert, granted ——■ U. S .----- , 12 L. Ed. 2d

1042; Lupper v. Arkansas, No. 5, October Term 1964, peti-

14

tion for cert, granted-----U. S. - — , 12 L. Ed. 2d 1043.

Where a petition for certiorari presents questions identical

with, or similar to, issues already pending before this

Court in another case in which certiorari has been granted,

the petition is appropriate for review. Compare Trustee

of Monroe Ave. Church of Christ v. Perkins, 334 U. S. 813,

with Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

Petitioners’ argument here is threefold. Firstly, the use

of state judicial machinery in the arrest, conviction, and

punishment of petitioners is an exercise of state power in

the Fourteenth Amendment sense. With the utmost re

spect, petitioners submit that Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S.

1, is applicable and cannot properly be distinguished. By

this exercise of state power, the state enforces and encour

ages the custom and usage of racial discrimination and

segregation in the state.

Second, the segregation custom has been caused, at least

in part, by laws of the state of North Carolina. Laws

causally affect social customs beyond the time of their in

validation or repeal and beyond the range of their enforc-

able scope.

Thirdly, state power is involved to a significant degree

where the state has preferred the discriminator’s insub

stantial property claim to the petitioners’ claim of equal

treatment in places of public accommodations.

These cases present additional factors not heretofore

considered by this Court. Since the last time these issues

were presented to the Court, Congress has enacted the

Civil Rights Bill of 1964, 78 Stat. 241 (discussed further

with regard to its abative effect upon these convictions,

infra, pp. 16-25). Congress has prohibited discrimination

or segregation supported by “state action” in certain estab

lishments of public accommodation. §201 provides, inter

alia,

15

§201 (b) Each of the following establishments which

serves the public is a place of public accommodation

within the meaning of this title if its operations affect

commerce, or if discrimination or segregation by it is

supported by State action:

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch

counter, soda fountain, or other facility principally

engaged in selling food for consumption on the prem

ises, including, but not limited to, any such facility

located on the premises of any retail establishment; or

any gasoline station; . . . 78 Stat. 243. (Emphasis sup

plied.)

“State action” in this regard is defined by Congress:

§201 (d) Discrimination or segregation by an estab

lishment is supported by State action within the mean

ing of this title if such discrimination or segregation

(1) is carried on under color of any law, statute, ordi

nance, or regulation; or (2) is carried on under color

of any custom or usage required or enforced by officials

of the State or political subdivision thereof; or (3) is

required by action of the State or political subdivision

thereof. 78 Stat. 243.

Congress has specifically considered the problem of racial

discrimination in places of public accommodation as re

lated to State action prohibited by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Petitioners submit that the complexities of this prob

lem considered most recently by this Court in the opinions

in Bell v. Maryland, supra, show it a particularly appro

priate area for Congressional guidance. See: Fay v. New

York, 332 U. S. 261, 283.

16

II.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Now Secures to Peti

tioners the Right to the Conduct Which the State Seeks

to Punish; Therefore,

A. U nder fed era l law , these p ro secu tions are abated.

On July 2, 1964, the President signed the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241 providing, inter alia:

T itle II See. 201. (a) All persons shall be entitled

to the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services,

facilities, privileges, advantages, and accommodations

of any place of public accommodation, as defined in

this section, without discrimination or segregation on

the ground of race, color, religion, or national origin.

(b) Each of the following establishments which

serves the public is a place of public accommodation

within the meaning of this title if its operations affect

commerce, or if discrimination or segregation by it is

supported by State action: . . .

* # # # *

(2) any restaurant. . .

* * # * #

(c) The operations of an establishment affect com

merce within the meaning of this title if . . . (2) in

the case of an establishment described in paragraph

(2) of subsection (b), it serves or offers to serve inter

state travelers or a substantial portion of the food

which it serves, or gasoline or other products which

it sells, has moved in commerce; . . . 78 Stat. 243.

The Plantation Restaurant clearly falls within the terms

of this statute. The restaurant is located on interstate high

way 301 (D. 15, 18, 19; B. 15, 16, 17), and is advertised

on billboards “for some distance coming into Enfield and

17

for some miles going out of Enfield” (D. 19). Advertise

ments also appear in newspapers, on the radio, and in the

rooms of the adjoining motel (D. 19, 20; B. 17). This res

taurant is clearly one which “offers to serve interstate

travelers” under the terms of §201(C)(2), supra.

An independent part of §201 extends coverage to a res

taurant if the “discrimination or segregation by it is sup

ported by State action,” §201 (b), supra. This section is

defined by §201 (d), 78 Stat. 243:

Discrimination or segregation by an establishment is

supported by State action within the meaning of this

title if such discrimination or segregation (1) is carried

on under color of any law, statute, ordinance, or regu

lation; or (2) is carried on under color of any custom

or usage required or enforced by officials of the State

or political subdivision thereof; or (3) is required by

action of the State or political subdivision thereof.

Petitioners submit that in the case at hand, the discrim

ination was carried on “under color of any custom or

usage required or enforced by officials of the state. . . . ”

The arrest, conviction, and punishment of these petitioners

for their refusal to obey an order which was admittedly

discriminatory and in furtherance of a policy of racial seg

regation (D. 17, 22; B. 21), meet the terms of the Act.

By either view of the Act’s coverage, therefore, had

these alleged offenses occurred after its passage, the Civil

Rights Act would furnish a complete defense. §203, 78

Stat. 244 specifically provides that:

“No person shall . . . (c) punish or attempt to punish

any person for exercising or attempting to exercise

any right or privilege secured by section 201 or 202.”

18

Senator Humphrey, floor manager for the Senate, read into

the record a Justice Department statement explaining

§203(c).

“This [§203(c)] plainly means that defendant in a

criminal trespass, breach of the peace, or other sim

ilar case can assert the rights created by 201 and 202

and that state courts must entertain defenses grounded

upon these provisions.” Cong. Record, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. 9162-3 (May 1,1964).

Not only the text of the Act, but all the implications of

the text are matters of the federal law, completely over

riding contradictory state law. Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U. S.

(9 Wheaton) 1 (1824); Sola Elec. Co. v. Jefferson Elec.

Co., 317 U. S. 173 (1942); Sperry v. Florida, 373 U. S. 379

(1963). Federal authority has therefore removed the “of

fense” charged in the cases at bar from the state’s category

of punishable crimes, and petitioners submit that federal

law abates their convictions and the forthcoming punish

ment.

The general federal rule is that a change in the law,

prospectively rendering that conduct innocent which was

formerly criminal, abates prosecutions which were started

under the prior law. See Bell v. Maryland, —— U. S .----- ,

12 L. Ed. 2d 822, 826-7, n. 2; United States v. Chambers, 291

U. S. 217 (1934); United States v. Tynen, 78 U. S. (11

Wall.) 88 (1871). Though the case has apparently never

arisen, there would seem to be no reason for the non

application of this rule to the operation of a federal statute

upon a state proceeding where the federal statute has the

effect of securing the right to conduct which formerly was

unlawful, and rendering unlawful the actions of the pro

prietor whose interests the state prosecution seeks to pro

tect. Cf. Bell v. Maryland, supra, at p. 828. Indeed the gen-

19

eral rule is a fortiori in this case because the federal author

ity is paramount.

The only possible exception to this general rule is the

first sentence of the Act of February 25, 1871, R. S. 13,

now codified in 1 U. S. C. §109, 61 Stat. 635:

Repeal of statutes as affecting existing liabilities.—

The repeal of any statute shall not have the effect to

release or extinguish any penalty, forfeiture, or lia

bility incurred under such statute, unless the repealing

Act shall so expressly provide, and such statute shall

be treated as still remaining in force for the purpose

of sustaining any proper action or prosecution for the

enforcement of such penalty, forfeiture, or liability. . . .

There are numerous reasons why this saving clause is

inapplicable in the present case. This statute, even more

limited than the one discussed by this court in the Bell

case refers to “repeal” only. It seems inappropriate to label

the effect of the Civil Rights Act upon the state trespass

laws as a “repeal” or the equivalent of a repeal, Bell v.

Maryland, supra, at p. 828. Also, it is very clear in the

context and legislative history of the 1871 Act, that the

Congress that passed it had in mind only the effect of one

federal “statute” upon another, and never intended the

crucial word “statute” to apply to state laws at all. It

would violate normal canons of construction in criminal

matters to stretch this wording to cover a problem in fed

eral-state relations which its framers did not consider;

see Million, Expiration or Repeal of a Federal or Oregon

Statute as a Bar to Prosecution for Violation Thereunder,

24 Ore. L. Rev. 25, 31, 32 (1944).

Further considerations demand this narrow reading of

the saving clause. Where Congress has established affirma

tive rights to conduct which previously had been labeled as

20

criminal, it would be strange indeed to infer an intent of

Congress that states carry out punishment under the old

criminal label. As said in Bell v. Maryland, supra:

. . . The legislative policy embodied in the superven

ing enactments here would appear to be much more

strongly opposed to that embodied in the old enactment

than is usually true in the case of an “amendment” or

“repeal.” It would consequently seem unlikely that the

legislature intended the saving clause to apply in this

situation, where the result of its application would be

the conviction and punishment of persons whose

“crime” has been not only erased from the statute books

but officially vindicated by the new enactments. A leg

islature that passes a public accommodations law mak

ing it unlawful to deny services on account of race

probably did not desire that persons should still be

prosecuted and punished for the “crime” of seeking

service from a place of public accommodations which

denies it on account of race. Since the language of the

saving clause raises no barrier to a ruling in accordance

with these policy considerations, we should hesitate

long indeed before concluding that the Maryland Court

of Appeals would definitely hold the saving clause ap

plicable to save these convictions. 12 L. Ed. 2d 829.

When working within the area of its own responsibility,

this court should hesitate expanding a narrowly drawn

saving clause, with the result of condoning the punishment

of petitioners for doing what Congress has, in one of the

great legislative enactments of our time, said that it is in

the national interest they be allowed to do unpunished.

Secondly, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 speaks of the

rights and privileges of equal treatment in places of public

21

accommodation as “secured” from punishment by the Act,

§203(c), supra. The normal dictionary meaning of the

word “secured” and the legislative history of the Act go

far in indicating that Congress looked towards the protec

tion from punishment of persons who had exercised

“rights,” at least of a moral nature, before the passage

of the Act. House Comm., on Civil Rights Act H. R. Rep.

No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963).

One need not become concerned with questions of a

“retroactive” application of the Civil Rights Act. The

Act, when defining “discrimination . . . supported by State

action, . . . ” (§201(d)), supra, and when forbidding punish

ment for the exercise of secured rights §203 (c), supra, is

directed towards the elimination of State enforced segre

gation customs in places of public accommodation. The

convictions and punishment of these petitioners, which the

State of North Carolina here seeks to enforce before this

Court, as the highest court in the appellate processing of

these convictions, are the very actions in furtherance and

perpetuation of racial discrimination against which Con

gress has acted.

We ask here whether this Court should avoid the direc

tive against punishment embodied in the act and the gen

eral federal policy of abating these prosecutions by a broad

reading of the saving clause. Petitioners submit that such

an unprecedented, lavish, reading would be an anomaly

in light of the above considerations and the fact that peti

tioners face punishment for conduct which Congress has

declared to be in the national interest, outlawing contrary

private and state concerns.

Avoidance of this anomaly would not alone be a sufficient

ground for reversal if the technical grounds were shaky.

They are not, they are quite solid. The supervening fed-

22

eral law, paramount in authority, cannot have less effect on

state law than it would on federal law. The settled federal

rule, absent federal statute, would produce the effect of

abatement. The one “saving” statute in this context and

on the basis of legislative history is quite inapplicable to

save these state convictions. These considerations cor

respond exactly with the obvious equities of these cases,

and no contrary public or private interests can now be

asserted which have not been outlawed.

The settled federal rule of abatement, therefore applies

to these judgments, and no statutory bar to its application

exists. The judgments should be reversed on this ground

and remanded for dismissal.

B. T h ese cases, i f n o t reversed o u tr ig h t, sh o u ld be rem a n d ed to

th e S u p re m e C ourt o f N orth C arolina fo r its d e term in a tio n

o f the abative e ffect o f th e fed era l C ivil R ig h ts A ct o f 1964 .

The minimal result required in these cases by the deci

sion in Bell v. Maryland, supra, is their remand to the

state courts. In Bell, this Court remanded to the state court

twelve trespass convictions under circumstances similar

to those in the present cases, in order that the Maryland

court could determine the effect of the Maryland public

accommodations law enacted subsequent to state court pro

ceedings, but while the cases were still under review. In

the present cases, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (discussed

supra at 16-22), is the intervening statute requiring the

redetermination by the North Carolina courts. Although

this statute is federal, the federal law is a part of the law

of each state. Hauenstein v. Lynkam, 100 U. S. 483; Testa

v. Katt, 330 U. S. 386. At the least, therefore, the Bell hold

ing requires the remand of these cases to the Supreme Court

of North Carolina.

23

North Carolina, like Maryland, Bell v. Maryland, supra,

at 826, follows the universal common-law rule that when the

legislature removes the condemnation from conduct which

was previously deemed criminal, pending criminal proceed

ings are abated. In State v. Williams, 97 N. C. 455, 2 S. E.

55, 56 (1887) the North Carolina Supreme Court held:

“The act punished must be criminal when judgment is

demanded and authority to render it must still reside

in the court.”

That pronouncement is one of a list of similar decisions.

State v. Cress, 4 Jones (49 N. C.) 421 (1857); State v.

Long, 78 N. C. 571 (1878); State v. Massey, 103 N, C. 356,

9 S. E. 632 (1889).

North Carolina has two statutes which could conceivably

limit the common law rule,

N. C. Gen. Stat. §12-2. Repeal of statute not to affect

actions.—The repeal of a statute shall not affect any

action brought before the repeal, for any forfeitures

incurred, or for the recovery of any rights accruing

under such statute.

N. C. Gen. Stat. §12-4. Construction of amended

statute.—Where a part of a statute is amended it is

not to be considered as having been repealed and re

enacted in the amended form; but the portions which

' are not altered are to be considered as having been

the law since their enactment, and the new provisions

as having been enacted at the time of the amendment.

The former statute is one even more narrowly drawn

than the similar statute considered by the court in Bell,

supra. The latter statute, rather than acting as a saving

clause, appears to exclude liability where the basis of

criminality no longer remains, see State v. Massey, supra,

24

at 633. What the Court said in Bell, supra, regarding the

establishment of an affirmative right to previously “crim

inal” conduct is applicable to both statutes:

“The absence of such terms [‘amendment’ and ‘re

peal’] from the public accommodations laws becomes

more significant when it is recognized that the effect

of these enactments upon the trespass statute was

quite different from that of an ‘amendment’ or even a

‘repeal’ in the usual sense. These enactments do not

—in the manner of an ordinary ‘repeal,’ even one that

is substantive rather than only formal or technical—

merely erase the criminal liability that had formerly

attached to persons who entered or crossed over the

premises of a restaurant after being notified not to

because of their race; they go further and confer upon

such persons an affirmative right to carry on such con

duct, making it unlawful for the restaurant owner or

proprietor to notify them to leave because of their

race. Such a substitution of a right for a crime, and

vice versa, is a possibly unique phenomenon in legis

lation; it thus might well be construed as falling out

side the routine categories of ‘amendment’ and ‘re

peal.’ ” 12 L. Ed. 2d at 828.

These considerations are consistent with North Carolina

law. Of those cases which have held that criminal liability

is not abated by the repeal or amendment of a statute, all

deal with statutes which were simply repealed and re

enacted, or amended in some insubstantial way. In . each

case, the conduct remained a crime after the change in the

law. The repeal was a mere technicality in the enactment

of a new statute which proscribed the same conduct. E.g.,

State v. Foster, 185 N. C. 674, 116 S. E. 561 (1923); State

25

y. Moon, 178 N. C. 715, 100 8. E. 614 (1919); State v.

Broadway, 157 N. C. 598, 72 S. E. 987 (1911); State v.

Perhins, 141 N. C. 797, 53 S. E. 735 (1906); State v. Putney,

61 N. C. 543 (1866-67). The effect of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 is not so slight.

It suffices here to raise the question of the North Carolina

law. If this Court does not reverse the convictions out

right as a matter of federal law, the North Carolina court

should be given the opportunity to decide the question of

the abative effect of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 under

North Carolina law. Bell v. Maryland, supra, at 830-831.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, petitioners pray

tha t the petition for w rit of certiorari be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles L. Black, J r,

Samuel S. Mitchell

F loyd B. McK issick

Of Counsel

A P P E N D I C E S

APPENDIX

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Spring Term, 1964

No. 147—Halifax

State,

v.

E llen Marie Davis.

Appeal by defendant from Parker, J., October Criminal

Session 1963 of Halifax.

The defendant was tried upon a bill of indictment charg

ing her with a violation of the provisions of OS 14-134, in

that she unlawfully trespassed upon the premises of the

Plantation Restaurant at Enfield, North Carolina. The

restaurant is owned and operated by William R. Davis, the

prosecuting witness, who also owns the Enfield Motel

located about 50 feet north of the restaurant on the same

side of Highway 301. The restaurant serves white people

only and has a sign to that effect at the entrance thereof.

The State’s evidence tends to show that the Plantation

Restaurant is located about 65 feet from Highway 301 with

in the town limits of Enfield; that on the night of 6 August

1963 the defendant and other Negroes, approximately 35

in number, forced their way into the Plantation Restaurant

through the back door and took seats at tables where white

customers were being served. That around noon on 7

August 1963 the defendant, accompanied by approximately

2a

35 other Negroes, approached the front entrance of the

Plantation Restaurant, and the owner of the restaurant

locked the front door. The defendant sat down on the

floor mat in front of the door. The owner of the restaurant

unlocked the front door and repeatedly requested the de

fendant and others to move away from the front door in

order that his customers might enter the restaurant. He

also requested them to leave the premises. Neither the de

fendant nor the other Negroes present paid any attention

to the requests of the proprietor of the restaurant. Offi

cers were called, and the request to the defendant and the

other Negroes to leave the premises of the restaurant was

again made in the presence of the officers, and upon the

failure of the defendant and others to unblock the en

trance to the restaurant and leave the premises, the defen

dant and others were arrested and charged with trespass.

The State’s evidence also tends to show that on this

occasion the defendant never requested service at the

restaurant.

The defendant moved for judgment as of nonsuit at the

close of the State’s evidence. Motion denied. The defen

dant offered no evidence.

The jury returned a verdict of guilty as charged in the

bill of indictment. From the judgment imposed, the de

fendant appeals, assigning error.

Attorney General Bruton; Deputy Attorney General

R alph Moody for the State

T heaoseus T. Clayton ; W. 0 . W arner ; Samuel S. Mitch

ell; F loyd B. McK issick for the defendant

Denny, C .J .

The appellant assigns as error the refusal of the court

below to sustain her motion for judgment as of nonsuit.

3a

The defendant contends that GrS 14-134, which in per

tinent part reads: “If any person after being forbidden to

do so, shall go or enter upon the lands of another, without a

license therefor, he shall be guilty of a misdemeanor,” is

unconstitutional by reason of conflict with Article I, Sec

tion 17 of the Constitution of North Carolina and the

Privileges or Immunities, Due Process and Equal Protec

tion Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States; that said prosecution here rests

upon an unlawful exercise of legislative power by a private

citizen, to wit, the prosecuting witness. In other words,

the defendant contends she has the inherent right to exer

cise the fundamental freedom to enter upon the premises

of any private business which is open to the public gen

erally, whether she is forbidden to do so or not, and any

abridgement of that right is unconstitutional.

This Court, in S. v. Clyburn, 247 NC 455, 101 SE 2d 295,

speaking through Rodman, J., said: “Our statutes, GS

14-126 and 134, impose criminal penalties for interfering

with the possession or right of possession of real estate

privately held. These statutes place no limitation on the

right of the person in possession to object to a disturbance

of his actual or constructive possession. The possessor may

accept or reject whomsoever he pleases and for whatsoever

whim suits his fancy. When that possession is wrongfully

disturbed it is a misdemeanor. The extent of punishment

is dependent upon the character of the possession, actual

or constructive, and the manner in which the trespass is

committed. Race confers no prerogative on the intruder;

nor does it impair his defense.

“The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States created no new privileges. It merely pro

hibited the abridgement of existing privileges by state ac

tion and secured to all citizens the equal protection of

the laws. * * *

4a

“ * * * (I) t is apparent the Legislature intended to pre

vent the unwanted invasion of the property rights of an

other, S. v. Cooke, supra (246 NC 518, 98 SE 2d 885;

S. v. Baker, 231 NC 136, 56 SE 2d 424. It is not the act

of entering or going on the property which is condemned;

it is the intent or manner in which the entry is made that

makes the conduct criminal. A peaceful entry negatives

liability under GS 14-126. An entry under a bona fide

claim of right avoids criminal responsibility under GS

14-134 even though civil liability may remain. S. v. Faggart,

170 NC 737, 87 SE 197; S. v. Wells, 142 NC 590; S. v.

Fisher, 109 NC 817, S. v. Crosset, 81 NC 579.

“What is the meaning of the word ‘enter’ as used in

the statute defining criminal trespass? The word is used

in GS 14-126 as well as GS 14-134. One statute relates to

an entry with force; the other to a peaceful entry. We have

repeatedly held, in applying GS 14-126, that one who re

mained after being directed to leave is guilty of a wrongful

entry even though the original entrance was peaceful and

authorized. S. v. Goodson, supra (235 NC 177, 69 SE 2d

242); S. v. Fleming, 194 NC 42, 138 SE 342; S. v. Bobbins,

123 NC 730; S. v. Webster, 121 NC 586; S. v. Gray, 109

NC 790 ; S. v. Talbot, 97 NC 494. The word ‘entry’ as used

in each of these statutes is synonymous with the word ‘tres

pass.’ It means an occupancy or possession contrary to the

wishes and in derogation of the rights of the person hav

ing actual or constructive possession. Any other interpreta

tion of the word would improperly restrict clear legisla

tive intent. * * * ”

In light of the foregoing decision and the authorities

cited therein, we hold that where a person without per

mission or invitation enters upon the premises of another,

and after entry thereon his presence is discovered and he

is unconditionally ordered to leave the premises by one

5a

in the legal possession thereof, if he refused to leave and

remains on the premises, he is a trespasser from the be

ginning.

Likewise, “it is the law of this jurisdiction that although

an entry on lands may be effected peaceably and even with

permission of the owner, yet if, after going upon the

premises of another, the defendant uses violent and abusive

language and commits such acts as are reasonably cal

culated to intimidate or lead to a breach of the peace, he

would be liable for trespass civiliter as well as crimiliter

(S. v. Stinnett, 203 NC 829, 167 SE 63), for ‘It may be,

he was not at first a trespasser, but he became such as

soon as he put himself in forceable opposition to the prose

cutor.’ ” Freeman v. Acceptance Corp., 205 NC 257, 171 SE

63.

The defendant further contends that her arrest and

prosecution were violative of her rights under GS 72-1,

which reads as follows: “Every innkeeper shall at all times

provide suitable feed, rooms, beds and bedding for strangers

and travelers whom he may accept as guests in his inn or

hotel.” (Emphasis ours)

There is evidence in the record to the effect that the

prosecuting witness owned the Enfield Motel; however,

there is no evidence in the record tending to show that the

prosecuting witness operated or managed the motel. Fur

thermore, there is no evidence tending to show that the

defendant ever applied for lodging at the motel. There

fore, we hold that GS 72-1 has no application to the facts

in this case.

We further hold that the provisions of GS 14-134 do not

conflict with Article I, Section 17 of the Constitution of

North Carolina or with the Privileges or Immunities, Due

Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution o.'f the United States.

United States v. Harris, 106 US 629, 27 L.Ed. 290.

6a

The evidence adduced by the State in the trial below was

sufficient to carry the case to the jury and to support the

verdict rendered.

The motion for judgment as of nonsuit was properly

overruled.

We have examined the remaining assignments of error

and they present no prejudicial error.

In the trial below, we find

No Erbor.

7a

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Spring Term, 1964

No. 148—Halifax

State,

v.

R obert Blow.

Appeal by defendant from Parker, J., October Criminal

Session 1963 of Halifax.

The defendant was tried upon a bill of indictment charg

ing him with a violation of the provisions of GS 14-134, in

that he unlawfully trespassed upon the premises of the

Plantation Restaurant at Enfield, North Carolina. The

restaurant is owned and operated by William R. Davis,

the prosecuting witness, who also owns the Enfield Motel

located about 50 feet north of the restaurant on the same

side of Highway 301. The restaurant serves white people

only and there is a sign to that effect at the entrance

thereof.

The jury returned a verdict of guilty as charged in

the bill of indictment. From the judgment imposed, the

defendant appeals, assigning error.

Attorney General Brtjton; Deputy Attorney General

Ralph Moody for the State

Theaoseus T. Clayton ; W. 0 . W arner ; Samuel S. Mitch

ell; F loyd B. McK issick for the defendant

8a

P er Curiam.

The State’s evidence against this defendant was substan

tially the same as the evidence in the case of S. v. Davis,

ante.

The defendant’s assignments of error purport to raise

the same questions raised in the above case. The trial,

verdict and judgment entered in this case will be upheld on

authority of the opinion in S. v. Davis, supra.

No E rror.

9a

Judgment

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Spring Term, 1964

No. 147—Halifax County

State,

vs.

E llen Marie Davis.

This cause came on to be argued upon the transcript of

the record from the Superior Court Halifax County: Upon

consideration whereof, this Court is of opinion that there

is no error in the record and proceedings of said Superior

Court.

It is therefore considered and adjudged by the Court here

that the opinion of the Court, as delivered by the Honor

able Emery B. Denny, Chief Justice, be certified to the

said Superior Court, to the intent that the proceedings be

had therein in said cause according to law as declared

in said opinion. And it is considered and adjudged further,

that the defendant and surety to the appeal bond, Bankers

Fire and Casualty Insurance Company, do pay the costs

of the appeal in this Court incurred, to wit, the sum of

Thirty and 45/100 dollars ($30.45), and execution issue

therefor. Certified to Superior Court this 30th day of

March 1964.

Adrian J. Newton

By /s / Sarah B. B anner

Clerk of the Supreme Court

Sarah B. Hanner, Deputy Clerk

A True Copy

/ s / Adrian J. Newton

Clerk Supreme Court

Judgment

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Spring Term, 1964

No. 148—Halifax County

S tate,

vs.

R obert Blow.

This cause came on to be argued upon the transcript of

the record from the Superior Court Halifax County: Upon

consideration whereof, this Court is of opinion that there

is no error in the record and proceedings of said Superior

Court.

It is adjudged by the Court here that the opinion of the

Court, be certified to the said Superior Court, to the intent

that the proceedings be had therein in said cause according

to law as declared in said opinion. And it is considered

and adjudged further, that the defendant and surety to the

appeal bond, Bankers Fire and Casualty Insurance Com

pany, do pay the costs of the appeal in this Court incurred,

to wit, the sum of Thirty-One and 60/100 dollars ($31.60),

and execution issue therefor. Certified to Superior Court

this 30th day of March 1964.

Adrian J. Newton

By /s / Sarah B. Hanner

Clerk of the Supreme Court

Sarah B. H anner, Deputy Clerk

A T rite Copy

/ s / Adrian J . Newton

Clerk of the Supreme Court

11a

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

State of North Carolina

v.

E llen Marie Dayis

Appeal docketed

Case argued

Opinion filed

17 January 1964

25 February 1964

18 March 1964

Final judgment entered 18 March 1964

I, Adrian J. Newton, Clerk of the Supreme Court of

North Carolina, do hereby certify the foregoing to he a

full, true and perfect copy of the record and proceedings

in the above entitled case as the same now appear for the

originals on file in my office.

I further certify that the rules of this Court prohibit

filing of petitions to rehear in criminal cases.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and

affixed the seal of said Court at office in Raleigh, North

Carolina, this the 24th day of April 1964.

/s / Adrian J. Newton

Clerk of the Supreme Court

of North Carolina

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

State

v.

R obert Blow

Appeal docketed

Case argued

Opinion filed

11 January 1964

25 February 1964

18 March 1964

Final judgment entered 18 March 1964

I, Adrian J. Newton, Clerk of the Supreme Court of

North Carolina, do hereby certify the foregoing to be a

full, true and perfect copy of the record and proceedings

in the above entitled case as the same now appear from the

originals on file in my office.

I further certify that the rules of this Court prohibit

filing of petitions to rehear in criminal cases.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and

affixed the seal of said Court at office in Raleigh, North

Carolina, this the 24th day of April 1964.

/ s / Adrian J. Newton

Clerk of the Supreme Court

of North Carolina

13a

APPENDIX B

Statutory and Regulatory Provisions

Civil Rights Act of 1964, %%201-203, 78 Stat. 243, 244:

Sec. 201. (a) All persons shall be entitled to the full and

equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges,

advantages, and accommodations of any place of public

accommodation, as defined in this section, without discrim

ination or segregation on the ground of race, color, religion

or national origin.

(b) Each of the following establishments which serves

the public is a place of public accommodation within the

meaning of this title if its operations affect commerce, or if

discrimination or segregation by it is supported by State

action:

(1) any inn, hotel, motel or other establishment which

provides lodging to transient guests, other than an es

tablishment located within a building which contains not

more than five rooms for rent or hire and which is actually

occupied by the proprietor of such establishment as his

residence;

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch counter,

soda fountain, or other facility principally engaged in sell

ing food for consumption on the premises, including, but

not limited to, any such facility located on the premises of

any retail establishment; or any gasoline station,

(3) any motion picture house, theater, concert hall, sports

arena, stadium or other place of exhibition or entertain

ment; and

(4) any establishment (A) (i) which is physically located

within the premises of any establishment otherwise cov-

14a

ered by this subsection, or (ii) within the premises of

which is physically located any such covered establishment,

and (B) which holds itself out as serving patrons of such

covered establishment.

(c) The operations of an establishment affect commerce

within the meaning of this title if (1) it is one of the

establishments described in paragraph (1) of subsection

(b); (2) in the case of an establishment described in para

graph (2) of subsection (b ); it serves or offers to serve

interstate travellers or a substantial portion of the food

which it serves, or gasoline or other products which it sells,

has moved in commerce; (3) in the case of an establishment

described in paragraph (3) of subsection (b), it customarily

presents films, performances, athletic teams, exhibitions,

or other sources of entertainment which move in commerce;

and (4) in the case of an establishment described in para

graph (4) of subsection (b), it is physically located within

the premises of, or there is physically located within its

premises, an establishment the operations of which affect

commerce within the meaning of this subsection. For pur

poses of this section, “commerce” means travel, trade,

traffic, commerce, transportation, or communication among

the several States, or between the District of Columbia

and any State, or between any foreign country or any

territory or possession and any State or the District of

Columbia, or between points in the same State but through

any other State or the District of Columbia or a foreign

country.

(d) Discrimination or segregation by an establishment

is supported by State action within the meaning of this

title if such discrimination or segregation (1) is carried

on under color of any law, statute, ordinance, or regula

tion; or (2) is carried on under color of any custom or

usage required or enforced by officials of the State or

15a

political subdivision thereof; or (3) is required by action

of the State or political subdivision thereof.

(e) The provisions of this title shall not apply to a

private club or other establishment not in fact open to

the public, except to the extent that the facilities of such

establishment are made available to the customers or pa

trons of an establishment within the scope of subsection (b).

Sec. 202. All persons shall be entitled to be free, at any

establishment or place, from discrimination or segrega

tion of any kind on the ground of race, color, religion or

national origin, if such discrimination or segregation is

or purports to be required by any law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, rule, or order of a State or any agency or

political subdivision thereof.

Sec. 203. No person shall (a) withhold, deny, or attempt

to withhold or deny, or deprive or attempt to deprive, any

person of any right or privilege secured by section 201, or

202, or (b) intimidate, threaten, or coerce, or attempt to

intimidate, threaten or coerce any person with the purpose

of interfering with any right or privilege secured by sec

tion 201 or 202, or (c) punish or attempt to punish any

person for exercising or attempting to exercise any right

or privilege secured by section 201 or 202.

1 U.S.C. $109, 61 Stat. 635: Repeal of statutes as affecting

existing liabilities.—The repeal of any statute shall not

have the effect to release or extinguish any penalty, for

feiture, or liability incurred under such statute, unless the

repealing Act shall so expressly provide, and such statute

shall be treated as still remaining in force for the purpose

of sustaining any proper action or prosecution for the en

forcement of such penalty, forfeiture, or liability. The ex

piration of a temporary statute shall not have the effect

16a

to release or extinguish any penalty, forfeiture, or liability

incurred under such statute, unless the temporary statute

shall so expressly provide, and such statute shall be treated

as still remaining in force for the purpose of sustaining

any proper action or prosecution for the enforcement of

such penalty, forfeiture, or liability.

# # # # *

North Carolina General Statutes %12-2 (1953): Repeal of

statute not to affect actions.—The repeal of a statute shall

not affect any action brought before the repeal, for any

forfeitures incurred, or for the recovery of any rights

accruing under such statute. (1830, c. 4; E.C. c. 108, s. 1;

1879, c. 163; 1881, e. 48; Code, s. 3764; Eev. s. 2830. C.S.,

s. 3948.)

N.C. Gen. Stat. %12-4 (1953): Construction of amended

statute.—Where a part of a statute is amended it is not

to be considered as having been repealed and re-enacted

in the amended form; but the portions which are not altered

are to be considered as having been the law since their

enactment, and the new provisions as having been enacted

at the time of the amendment. (1868-9, c. 270, s. 22; 1870-1,

c. I l l ; Code, s. 3766; Eev., s. 2832; C.S., s. 3950.)

N.C. Gen. Stat. %14-134. (1953): Trespass on land after

being forbidden.—If any person after being forbidden to do

so, shall go or enter upon the lands of another, without a

license therefor, he shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and

on conviction, shall be fined not exceeding fifty dollars, or

imprisoned not more than thirty days.

N.C. Gen. Stat. §72-1 (1953): Must furnish accommoda

tions.—Every innkeeper shall at all times provide suitable

food, rooms, beds and bedding for strangers and travelers

17a

whom he may accept as guests in his inn or hotel. (1903,

c. 563; Rev., s. 1909; C.S., s. 2249.)

N.G. Gen. Stat. §72-46 (1953): State Board of Health to

regulate sanitary conditions of hotels, cafes, etc.—For the

better protection of the public health, the State Board

of Health is hereby authorized, empowered and directed to

prepare and enforce rules and regulations governing the

sanitation of any hotel, cafe, restaurant, tourist home,

motel, summer camp, food or drink stand, sandwich manu

facturing establishment, and all other establishments where

food or drink is prepared, handled, and/or served for pay,

or where lodging accommodations are provided. The State

Board of Health is also authorized, empowered and directed

to

(1) Require that a permit be obtained from said Board

before such places begin operation, said permit to

be issued only when the establishment complies with

the rules and regulations authorized hereunder, and

(2) To prepare a system of grading all such places as

Grade A, Grade B, and Grade C.

No establishment shall operate which does not receive

the permit required by this section and the minimum grade

of C in accordance with the rules and regulations of the

State Board of Health. The rules and regulations shall

cover such matters as the cleanliness of floors, walls, ceil

ings, storage spaces, utensils, and other facilities; ade

quacy of lighting, ventilation, water, lavatory facilities,

food protection facilities, bactericidal treatment of eating

and drinking utensils, and waste disposal; methods of food

preparation, handling, storage, and serving; health of em

ployees; and such other items and facilities as are neces

sary in the interest of the public health.

18a

N.C. Gen. Skat. %72-47 (1953): Inspections; report and

grade card.—The officers, sanitarians or agents of the

State Board of Health are hereby empowered and au

thorized to enter any hotel, cafe, restaurant, tourist home,

motel, summer camp, food or drink stand, sandwich manu

facturing establishment, and all other establishments where

food or drink is prepared, handled and/or served for pay,

or where lodging accommodations are provided, for the

purpose of making inspections, and it is hereby made the

duty of every person responsible for the management or

control of such hotel, cafe, restaurant, tourist home, motel,

summer camp, food or drink stand, sandwich manufacturing

establishment or other establishment to afford free access

to every part of such establishment, and to render all aid

and assistance necessary to enable the sanitarians or agents

of the State Board of Health to make a full, thorough and

complete examination thereof, but the privacy of no person

shall be violated without his or her consent. It shall be the

duty of the sanitarian or agent of the State Board of Health

to leave with the management, or person in charge at the

time of the inspection, a copy of his inspection and a grade

card showing the grade of such place, and it shall be the

duty of the management, or person in charge to post said

card in a conspicuous place designated by the sanitarian

where it may be readily observed by the public. Such grade

card shall not be removed by anyone, except an authorized

sanitarian or agent of the State Board of Health, or upon

his instruction.

N.C. Gen. Stat. %72-48 (1953): Violation of article a mis

demeanor.—Any owner, manager, agent, or person in

charge of a hotel, cafe, restaurant, tourist home, motel,

summer camp, food or drink stand, sandwich manufacturing