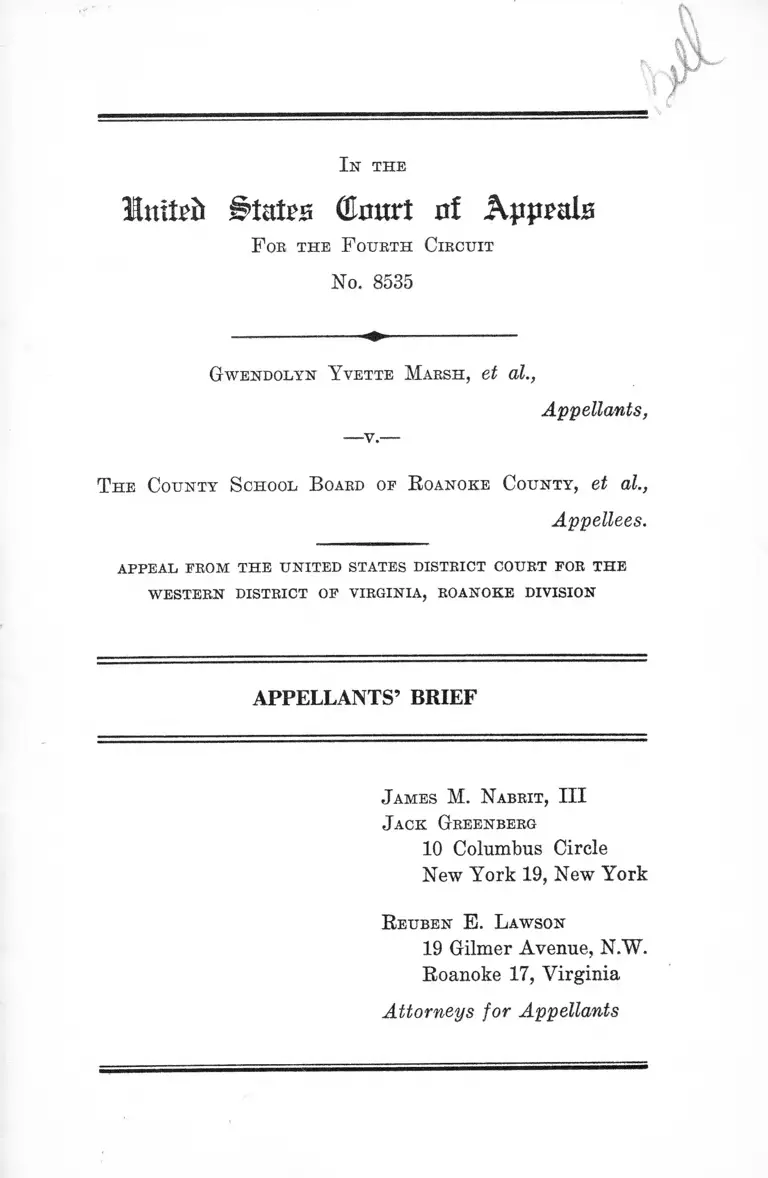

Marsh v The County School Board of Roanoke County Appellants Brief

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1962

45 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Marsh v The County School Board of Roanoke County Appellants Brief, 1962. 77306b0e-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/495d7779-2e20-4739-9c51-6ac4c732c465/marsh-v-the-county-school-board-of-roanoke-county-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

Imtpfc (tart at Appals

F oe the F ourth Cibcuit

No. 8535

Gwendolyn Y vette Maesh, et al.,

Appellants,

T he County S chool B oabd of R oanoke County, et al.,

Appellees.

appeal from the united states distbict court fob the

WESTERN DISTBICT OF VIRGINIA, ROANOKE DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

James M. Nabeit, II I

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R euben E. L awson

19 Gilmer Avenue, N.W.

Roanoke 17, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ............................—- ..........—- 1

Questions Involved........................................................ 5

Statement of Facts........................................................ 7

I. Segregation Practices in the County School

System................................................................. 7

II. Facts Relating to Plaintiffs’ Applications....... 12

A rgum ent....................................................................... 18

I. Plaintiffs were excluded from the all-white

Clearbrook School by use of racially discrimi

natory rules and procedures and are entitled

to injunctive relief requiring their admission 18

A. Plaintiffs possessed all the qualifications

required of white pupils attending Clear

brook but were assigned elsewhere on the

basis of their race......................................... 18

B. The 60-day rule was unreasonable and

racially discriminatory as applied to ap

pellants .......................................................... 18

C. The Placement Board’s protest and hearing

procedure was not an adequate and expedi

tious remedy, as every court that con

sidered it prior to this case has h eld ........ 24

D. Overcrowding at Clearbrook and the estab

lishment of a new all-Negro school in plain

tiffs’ neighborhood cannot bar their admis

sion to Clearbrook......................................... 28

PAGE

II. Appellants are entitled to an injunction re

straining defendants’ discriminatory assign

ment practices .................................................... 30

Conclusion.................. 33

Table of Cases:

Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913 (E. D. Ark. 1960) 37

Adkins v. School Board of City of Newport News,

148 F. Supp. 430 (E. D. Va. 1957), aff’d 246 F. 2d

325 (4th Cir. 1957) .................................................... . 25

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 266 F. 2d 507 (4th Cir. 1959) ...................... 30, 37

Allen y. School Board of City of Charlottesville, 3

Race Eel. Law R, 937 (W. D. Va. 1958) .................. 26

J. W. Bateson Co. v. Romano, 266 F. 2d 360, 2 F. R.

Serv. 2d 26d.42, Case 1 (6th Cir. 1959) .................. 23

Beckett v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 185 F.

Supp. 459 (E. H. Va. 1959), aff’d sub nom. Farley

v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960) .............. 25, 27

Blackwell v. Fairfax County School Board, 5 Race

Rel. Law R. 1056 (E. D. Va., Sept. 22, 1960) ....... 26

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954);

349 U. S. 294 (1955) ................................................ 33, 37

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 242 F. 2d 156

(5th Cir. 1957) ............................................................ 36

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956) ....... 34, 35

Cleary v. Indiana Beach, Inc., 275 F. 2d 543 (7th

Cir. 1960), cert. den. 364 U. S. 825 .......................... 23

Clemmons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio,

228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956) ................................. 29

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ......................... 33, 37

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4th Cir. 1959) 35

n

PAGE

I ll

Dodson v. School Board of the City of Charlottes

ville, 289 F, 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961) .......................... 30, 33

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3d Cir. 1960) .............. 29

Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960) ....... 16

Green v. School Board of Roanoke City, et al. (No.

8534, 4th Cir.) ........................................................... 8

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U. S. 32 (1940) ...................... 36

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321 (1944) ............. . 33

Hill v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d

473 (4th Cir. 1960) ................................................... 33, 37

Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265 F. 2d

95 (4th Cir. 1959) ............... .................................... 35

Hood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School

District No. 2, 295 F. 2d 390 (4th Cir. 1961) ........... 37

Jackson v. The School Board of the City of Lynch

burg, Va. (W. D. Va., C. A. No. 534, Jan. 15, 1962,

not yet reported) ......................... ......... ...............28, 32, 37

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ....................... ....... ...21, 22, 32, 33

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 4 Race

Eel. Law R. 31 (E. D. Va., Oct. 22, 1958; Jan. 23,

1959; Feb. 6, 1959); aff’d 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir.

1960); 179 F. Supp. 280 (E. D. Va. 1959) .............. 26

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d

370 (5th Cir. 1960) ............................... ...... ...22, 27, 33, 37

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 179

F. Supp. 745 (M. D. N. C. 1959), rev’d 283 F. 2d

667 (4th Cir. 1960) ............. ..... ....... ......................... 35

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 283

F. 2d 667 (4th Cir. 1960)

PAGE

29

IV

Merchants Motor Freight, Inc. v. Downing, 222 F. 2d

247, 22 F. R. Serv. 26d.42, Case 1 (8th Cir. 1955) .... 23

New Rochelle Tool Co. v. Ohio Crankshaft Co., 3 F. R.

Serv. 2d 30b.35, Case 1, 25 F. R. D. 20 (N. D. Ohio

1960) ..................... ...... ....... ....................................... 23

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) ..18, 22, 27,

33, 36, 37

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U. S. 395 (1946) 34

Rosenthal v. Peoples Cab Co., 3 F. R. Serv. 2d 26d.43,

Case 1, 26 F. R. D. 116 (W. D. Pa. 1960) .............. 23

School Board of the City of Charlottesville v. Allen,

240 F. 2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956) ..................................... 30

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91 (1945).............. 20

Smith v. Swormstedt, 16 How. (US) 288, 14 L. ed.

942 (1853) ................................................................... 36

Taylor v. School Board of the City of New Rochelle,

191 F. Supp. 181; 195 F. Supp. 231 (S. D. N. Y.

1961) , aff’d 294.F. 2d 36 (2d Cir. 1961), cert. den.

7 L. ed. 2d 339 ............................................................ 30

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County, 159 F. Supp. 567 (E. D. Va. 1957), aff’d

252 F. 2d 929 (4th Cir. 1957), cert, denied 356 U. S.

958 .............................................................................. 25

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County, 166 F. Supp. 529 (E. D. Va. 1958), aff’d in

part and remanded in part, sub nom. Hamm v.

County School Board of Arlington County, 263 F.

2d 226; 264 F. 2d 945 (4th Cir. 1959) .................. . 25, 29

PAGE

Y

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County (E. D. Va., C. A. No. 1341, June 3, 1959),

unreported ........... ..................................................... 25, 33

Thompson v. County School Board, etc., 4 Race Eel.

Law R. 609 (E. D. Va., July 25, 1959); 4 Race Rel.

Law R. 880 (E. I). Va., Sept. 1959) ; 5 Race Rel.

Law R. 1054 (E. D. Va., Sept. 16, 1960) ................. 26

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U. S.

364 (1948) ............ .................................................... 31

Walker v. Floyd County Board (W. D. Va., C. A. No.

1012; Sept. 23,1959, unreported)......................-...... 26

Statutes:

28 U. S. C. §1291 ...................... .............................. - - - 1

28 U; S. C. §1343 .............................................. 2

42 U. S. C. §1981........................................................... 2

42 U. S. C. §1983 ................... 2

F. R. C. P. Rule 23(a) (3) ................... .........- ............2, 35, 36

F. R. C. P. Rule 26(d)(2) ........ .......................... ......... 23

F. R. C. P. Rule 54(c) .................................. - .............. 34

Code of Va., §22-232.8 ________ _________ _____ .14,15,19,

24, 25

Other Authorities:

4 Moore’s Federal Practice 1190 H26.29 ...................... 23

Davis, Administrative Law Treatise, Vol. I, §§6.11,

6.09-6.10.......................... ....... ..........- ............. ........ 19

Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence, 5th Ed., 5 Symons,

1941, Vol. 1, §§260, 261a-n

PAGE

36

In t h e

Httitefc Court of Apprals

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 8535

Gwendolyn Y vette Marsh, et al.,

Appellants,

T he County S chool B oard of R oanoke County, et al.,

Appellees.

appeal from the united states district court for the

WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, ROANOKE DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from a final judgment (129a)1 entered

October 4, 1961, dismissing an action for injunctive and

declaratory relief against racial discrimination brought

by the plaintiffs-appellants, Negro school children and

parents in Roanoke County, Virginia, against the School

Board of Roanoke County, the Superintendent of Schools,

and the Pupil Placement Board of the Commonwealth of

Virginia. This appeal is brought under 28 U. S. C. §1291.

The complaint, filed August 31, 1960, by seven Negro

pupils (five of whom are appellants) and their parents and

1 Citations are to the Appendix to this Brief.

2

guardians, was a class action “ on behalf of all other Negro

children attending the public schools of the County of

Roanoke and their respective parents or guardians” (5a),

under Rule 23(a)(3), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

There was jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. §1343, the action

being authorized by 42 U. S. C. §1983 to enforce rights

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, and by 42 U. S. C. §1981 providing

for the equal rights of citizens.

The complaint identified the defendants County School

Board and Superintendent of Schools (5a-6a) as a state

agency and a state agent, respectively, exercising various

duties in maintaining, operating, and administering the

public schools of Roanoke County. It identified defendants

Oglesby, Justis and Wingo constituting the Virginia Pupil

Placement Board, a state agency vested with statutory

powers over the placement of pupils in schools (8a-9a).

The complaint alleged that despite the Supreme Court’s de

cisions that state-imposed racial segregation was uncon

stitutional and plaintiffs’ applications to the defendants

to attend public schools which they are eligible to enter

except for their race, the defendants were pursuing a

policy, practice, custom and usage of racial segregation and

would continue to do so unless restrained by the Court (7a-

8a). The complaint alleged that defendants were apply

ing the Virginia Pupil Placement Act in such a manner

as to perpetuate the pre-existing segregation system (9a);

that they required pupils seeking to attend a non-segregated

school to pursue certain inadequate administrative remedies

(10a); that plaintiffs had applied to enter an all-white

school prior to the 1960-61 school term and had been denied

admission on a racially discriminatory basis; and that the

various practices of the defendants complained of denied

plaintiffs their liberty without due process of law and the

3

equal protection of the laws secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment (lOa-lla).

Plaintiffs sought a declaration that certain of the ad

ministrative procedures prescribed by the Pupil Placement

Act were inadequate to secure plaintiffs’ rights to a non-

segregated education and need not be pursued by them as a

prerequisite to judicial relief, and prayed for a declaration

that the Pupil Placement Board’s policies and practices in

assigning pupils to segregated schools on the basis of race

was unconstitutional. The complaint also sought temporary

and permanent injunctive relief to restrain defendants from

“ any and all action that regulates or affects, on the basis of

race or color, the admission, enrollment or education of the

infant plaintiffs, or any other Negro children similarly

situated, to and in any public school operated by the defen

dants.” The complaint asked that the defendants be re

quired to present to the Court a comprehensive plan for

desegregation of the school system “with all deliberate

speed” in the event that they requested any delay in full

compliance (12a-14a).

On September 15, 1960, the Court heard and denied the

motion for preliminary injunction. On September 20, 1960,

the county school authorities filed a “Motion To Dismiss

and Answer” (15a). The motion to dismiss urged that the

complaint failed to state a claim charging (1) that facts

detailing the allegations of discrimination were not alleged;

(2) that plaintiffs’ applications for enrollment or transfer

were not timely filed under Placement Board rules and;

(3) that plaintiffs did not exhaust administrative remedies

under the Pupil Placement Act. The answer generally

denied the allegations of the complaint except for the

identity of the defendants and the receipt of plaintiffs’

applications for assignment to Clearbrook School. The an

swer alleged that the County School Board had “ devoted

4

itself to a concerted policy and effort of maintaining

good race relations” ; that prior to plaintiffs’ applications no

Negro pupils had requested admission to any white school;

that a school construction program was in progress, includ

ing a plan to erect a school in the neighborhood where the

plaintiffs lived, to be completed by September 1961, and

to which all of the plaintiffs “will definitely be assigned and

transferred for said 1961-62 school year” ; and that all

legal power over assignments was vested in the Pupil Place

ment Board.

The Placement Board’s answer (21a) generally denied

the allegations of the complaint except for the identity of

the defendants; asserted that the denial of plaintiffs’ re

quests for enrollment in Clearbrook School for the 1960-61

year was in accordance with a rule denying such requests

unless submitted at least 60 days before the school session;

asserted that they were also denied because of the lack

of a favorable recommendation from the county school

authorities; denied that plaintiffs were placed in school

or denied transfers on the “ sole ground of race or color” ;

asserted that the Placement Board was “under no obligation

or compunction to promote or accelerate the mixing of the

races in the public schools” ; and set up as a defense the

fact that the plaintiffs did not invoke the Board’s protest

and hearing procedures.

The case was tried May 24, 1961; the Court having re

served judgment on the motion to dismiss. Evidence pre

sented by the plaintiffs was received; the defendants called

no witnesses. On July 10, 1961, the Court filed its memo

randum opinion (122a). The Court stated (125a):

No evidence of any kind was offered indicating that

the Pupil Placement Board had discriminated on ac

count of race or color in the assignment of any student,

new or transferring, to the schools of Roanoke County.

5

The Court said of plaintiffs’ requests for enrollment (125a):

There is absolutely no evidence that these transfer

applications were denied on the ground of color or race.

They were denied solely on account of the fact that

they were not timely filed. The rule that all transfer

requests must be submitted sixty days prior to the

commencement of any school session is not unreason

able and must be complied with except in unusual

cases. It applies to all students, white and colored alike.

The Court concluded that the denial of the plaintiffs’

applications was proper; that the administrative proce

dures set forth in the Pupil Placement Act were not unrea

sonable and must be complied with except in unusual cases;

and that there was no evidence to justify the complaint that

the Pupil Placement Board members were administering

the Act so as to preserve and perpetuate the policy, practice,

and custom of assigning children to separate schools on

the basis of their race and color. The Court held that plain

tiffs were not entitled to any relief.

On October 4, 1961, the Court entered a final judgment

dismissing the case at the plaintiffs’ costs (129a). Notice

of appeal was filed on November 1, 1961 (131a).

Questions Involved

The following questions involved in this appeal were

presented by the pleadings in light of the evidence received

(see Statement of Facts) and were decided in the opinion

below against the claims of the appellants:

1. Whether the Negro pupil-plaintiffs are entitled to in

junctive relief requiring their admission to the all-white

Clearbrook Elementary School, having been refused admis

6

sion by the application of racially discriminatory rules and

procedures.

This question includes several subsidiary issues, namely:

(a) the validity of the Pupil Placement Board’s cut-off date

for applications as applied in the circumstances of this case;

(b) whether the plaintiffs’ failure to pursue the Pupil Place

ment Board’s protest and hearing procedure bars their

obtaining relief; and (c) whether the other matters urged

in defense, i.e., overcrowding at Clearbrook School and

the planned construction of a new all-Negro school in the

area where plaintiffs reside, were proper grounds for the

denial of relief.

2. Whether the plaintiffs and the class they represent

are entitled to injunctive and declaratory relief prohibiting

and condemning the racially discriminatory school assign

ment practices and procedures used by the defendants by

which pupils are initially assigned to schools on a racially

segregated basis and are then subjected to discriminatory,

burdensome and unreasonable procedures and assignment

standards if they attempt to escape the segregated initial

assignments.

The subsidiary issues included are: (a) the validity of

defendants’ initial assignments of pupils on a racial basis

to separate schools in accordance with separate overlapping

Negro and white school zones; (b) the validity of the de

fendants’ practice of planning new schools and selecting

sites for such schools on a racial basis so as to create all-

Negro schools; (c) the validity of defendants’ policy of re

fusing to take action to initiate desegregation and to de

velop a plan to eliminate assignments based on race; (d)

the validity of the defendants’ transfer procedures and

standards in light of the circumstances.

7

Statement of Facts

I. Segregation Practices in the County School System.

The Roanoke County public school system is composed

of 28 schools (28a, 120a) serving “ over 14,000” pupils, only

950 of whom are Negroes (30a). Three of the schools are

all-Negro schools (Carver High School, Craig Avenue and

Hollins elementary schools) (29a, 120a) and the other

schools are all-white (29a), there having been no desegrega

tion of pupils in the county schools at the time of the trial

(35a).2 Teachers (35a) and school buses (55a) are also

allocated on a segregated basis.

Pupils in the system are, with but a few individual excep

tions, assigned to and attending schools in accordance with

school zones established each year by the county school

authorities (31a-32a). Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2 is a map depict

ing the 1960-61 school zones. Separate school zones are

established for the all-Negro schools which overlap the

zones of white schools in the County (32a-33a).3

2 The record does not indicate the fact that after the trial one

Negro pupil (not a party in this case) successfully applied for

and obtained admission to one of the all-white high schools at the

beginning of the 1961-62 school term. Insofar as counsel are aware,

this one child’s admission in a white school represents the only

desegregation which has occurred in the county system.

3 Superintendent Horn testified (32a-33a) :

Q. Except for this type of individual exception, the students

are assigned in accordance with these zones? A. Yes, the

zones for this present year.

Q. Now, is it true that the zones for the three Negro schools

in the County are separate zones in the sense that they overlap

zones established for white schools? A. Yes. The three Ne

groes’ serve the entire County. The zones overlap.

Q. You have one Negro high school and four white high

schools? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, do the four white high schools have separate geo

graphic areas that they serve in the County? A. Yes.

(footnote continued on next page)

The opinion below did not discuss the school zones at all.

The opinion apparently inadvertently confused the evi

dence in this case with that in Green v. School Board of

Roanoke City, et al. (see record in No. 8534, 4th Cir.) which

was tried just after the instant case and does involve a

system described in the opinion as a “ feeder system” under

which certain schools “ feed” their students upon gradua

tion to other pre-designated schools (124a). There was

no evidence about a “ feeder system” in the instant case.

The Negro pupils are “fairly scattered” in different white

school zones about the County (57a), but they all attend the

three all-Negro schools.

Parents having children entering schools are routinely

directed to the school in their zone where they fill out a

Pupil Placement Board form (36a), which is checked by a

teacher or principal and forwarded to the superintendent’s

office where his staff again checks it and indicates a recom

mended assignment on the form. Such recommendations

are made in accordance with the County’s school zones

(37a). The forms are then forwarded to the Pupil Place

ment Board office in Richmond where the recommended

assignments are routinely approved—thus it is that the

students attend schools consistent with the county’s school

zones (37a-38a). Neither Superintendent Horn (38a) nor

Mr. Hilton, Executive Director of the Placement Board

(79a-80a), could recall any instance in which the county

Q. And the Negro high school— Carver— serves Negroes liv

ing everywhere? A. Yes.

Q. And for the elementary schools, the same type of thing

would be true; that is, the Negro school zones established on

the map overlap the white schools? A. Yes, sir. They do.

Q. Do you recall Exhibit 2? Do you recall correctly that

it shows the Negro school zones in crayon in one color and

the white schools in another color? A. I believe it does. But

I believe they are on different colors.

9

authorities’ recommendation for assignment was rejected

by the Pupil Placement Board. Mr. Oglesby, Chairman of

the Placement Board, testified that the only applications

“ that we spend time on are those where there is a conflict

between the desire of the parent and the recommendation

of the local school board,” and that the staff handles the

rest of the applications (83a). Mr. Hilton testified that the

Board assigns about 200,000 pupils a year; that these ap

plications, accompanied by local recommendations (70a-

71a), are handled by “processors” in the office who com

plete the portion calling for “action by the State Board,”

and rubber stamp Mr. Hilton’s signature on the forms

(76a).

It may be noted that the Court below said in its opinion

that “ The School Board and its Division Superintendent

do not make any assignments or any recommendations in

reference thereto.” (Emphasis supplied; 124a.) This

finding that the local authorities do not make recommenda

tions is wholly erroneous (there being no evidence in the

record even tending to support it), and is in conflict with

the uncontradicted testimony of the defendants themselves

and the documentary evidence as well. In addition to the

testimony on this subject discussed above (37a-38a, 79a-

80a, 82a-83a), see the references to and record of recom

mendations for the assignment of the seven plaintiffs in

this case (101a-107a, 43a, 47a-48a). Indeed, the Placement

Board’s answer referred to its policy of refusing transfers

in the absence of a “ favorable recommendation by local

school officials” and asserted that there had been no such

recommendation in plaintiffs’ cases (22a).

When pupils move their homes from one zone to another,

they are transferred either immediately or at the end of

the school session to the school in their new zones (39a),

and when they move into the County during a school

10

year they also attend the school in their zones (49a). The

basic qualification for admission to any of the schools

is residence in the zone, satisfying the age requirements,

and being in the grade levels served by the school (40a).

There are no specialized elementary or high schools; each

school is attended by the pupils who happen to live in its

zone (39a-40a). A few schools have ability grouping within

grades, but this is left to the principals and teachers (40a).

Both Messrs. Hilton and Oglesby were aware that vari

ous communities used school zones (77a, 84a). However,

Mr. Hilton testified that he did not have a copy of the

school zones used in Roanoke County and had never re

quested one (77a), and that the Placement Board had

never issued any memorandum to local school officials on

the subject of separate overlapping zones for Negro and

white pupils (77a-78a). Chairman Oglesby testified that

the Placement Board had made no announcements and

taken no action with respect to separate overlapping zones

for Negroes and whites in any community (83a-84a).

Mr. Oglesby stated that:

The applications acted on by the Pupil Placement

Board are those in which the wishes of the parents

differ from the ordinary assignment which is recom

mended by the School Board. All those were acted on

carefully. Some of those are Negro and some of them

are white (82a-83a).

He said that the assignment standards used by the Place

ment Board in such cases were: (1) requiring pupils to

attend the closest school to their homes (90a, 93a), without

regard to any school zones used by the local authorities

in organizing the pupils in schools (93a), and (2) requir

ing that transferring pupils have academic qualifications

“ at least up to the average in the school sought” (91a) or

“be good enough for us to believe that he would do the

11

work in the environment in which he wants to go” (92a),

in order to be granted a transfer.

Superintendent Hilton (35a) and the Chairman of the

County School Board, Mr. Trout (60a), testified that there

had been no announcement of any desegregation plans for

the system. Mr. Oglesby indicated that the Placement

Board had never participated in the formulation of any

plans for desegregation of any school district, and “ cer

tainly” did not contemplate doing anything of that nature

(84a). The minutes of the School Board and the Placement

Board do not indicate that any action was taken on a

petition for desegregation of the system submitted by

plaintiffs with their applications (42a~43a, lOSa-llOa, 116a).

Mr. Trout testified that the School Board located schools

for Negroes in the areas of the concentration of the Negro

population, planning the size of facilities on the basis of

the Negro population of the area concerned (61a), and that

this was true of the Pinkard Court School then under con

struction (61a). Superintendent Horn testified to substan

tially the same effect (97a), and stated that the Pinkard

Court School, to be opened in the neighborhood where the

plaintiffs live in September 1961 (94a), had been appointed

an all-Negro staff, and that there was a prepared list of

children—all of whom were Negroes—who were to be ad

ministratively transferred to that school for the 1961-62

term (95a). The School Board had authorized a committee

to purchase the site for this school at a meeting held Sep

tember 13,1960, two days before the preliminary injunction

hearing in this case. The Board’s minutes for the meeting

indicated its plan to base a part of its defense to the pres

ent lawsuit upon the availability of this school in plain

tiffs’ neighborhood (118a).

12

II. Facts Relating to Plaintiffs’ Applications.

The seven plaintiffs all live within the Clearbrook School

zone for white pnpils in the county (49a). They reside

about two and one-lialf miles from Clearbrook School

(where they applied) and ten miles from Carver School

(where they were assigned) (54a). White children attend

ing Clearbrook and living farther from that school than

plaintiffs do ride a school bus through the section where

plaintiffs live (55a).

On July 16, 1960, the plaintiffs’ applications4 and a peti

tion requesting desegregation of the school system were

delivered to Superintendent Horn’s office (40a-42a). Six

of the plaintiffs sought transfer to Clearbrook and one was

a beginner seeking original admission there.

Almost three weeks later (August 4th), these applica

tions were presented by Superintendent Horn at a regular

meeting of the County School Board, which merely directed

that the applications be transmitted to the Pupil Placement

Board (108a-109a). At this meeting Superintendent Horn

stated his view that assignments for the 1960-61 session

should be “ frozen” as of that date. The Board then adopted

a resolution barring further transfers during the school

year except “ for cases where parents have moved from

one school area to another” (109a).

After 11 more days (August 15, 1961), Superintendent

Horn carried out the direction to transmit the applications

to the Placement Board (111a), with a letter indicating

they were “ the applications of 7 Negro children to be ad

4 The Pupil Placement forms are at 101a-107a. The standard

forms do not have any place for parents to indicate their choice

of schools. Plaintiffs wrote in “ Clearbrook” on the line calling for

the name of the county or state. The forms had been executed and

given to plaintiffs’ attorney on June 6, and June 16; the attorney

was not aware of the 60-day rule (125a).

13

mitted to the Olearbrook Elementary School,” and also

stating the date of their delivery to his office by Attorney

Lawson (111a). Superintendent Horn’s assistant, at his

direction, recommended that all of the plaintiffs be assigned

to Carver School (43a, 47a, 101a-107a).

No indication of the reasons for this recommendation

was communicated to the Placement Board (43a, 46a) or

the plaintiffs. Mr. Horn testified that the reason for recom

mending that the plaintiffs be assigned to Carver was that

Clearbrook was overcrowded and that if plaintiffs were

admitted he would be required to admit the other 125 Negro

children living in the same area (47a-48a). He acknowl

edged that none of the other 125 pupils had applied to

enter Clearbrook (48a); that white pupils moving into the

Clearbrook zone after the plaintiffs applied would be ad

mitted routinely (49a), and that some white pupils did

move into the Clearbrook area and were admitted after

plaintiffs applied (58a). An exhibit prepared by Mr. Horn’s

office (12a) indicates that Clearbrook has a capacity of

360 pupils and Carver a capacity of 630 pupils. Another

exhibit indicates that Clearbrook had an enrollment of 383

on September 6, 1960, and 395 on October 1, 1960, while

Carver had an enrollment on September 6, 1960, of 639

and on October 1, of 686 pupils (121a). Carver School had

a lower pupil-teacher ratio than Clearbrook (121a), but it

should be noted that Carver, unlike any other school in

the County, serves all twelve school grades (57a).

On the next day, August 16, Mr. Hilton wrote to Dr.

Horn saying in part (112a):

Since you state that these applications were received

by you on July 14, it would not be in accordance with

Pupil Placement Board regulations to consider the

applications for transfer of these pupils at the begin

ning of the fall semester, September 1960. I refer you

14

to Pupil Placement Board Memo #24, issued July 17,

1959.

The Memorandum No. 24 referred to contains this Place

ment Board resolution (99a):

It was unanimously agreed that the Pupil Placement

Board will not consider any transfer request sub

mitted to it after sixty (60) days prior to the com

mencement of any school semester.

Mr. Hilton’s letter also asked that Mr. Horn advise the

plaintiffs of this information (112a). This was not done

until 13 days later when Superintendent Horn wrote the

parents on August 29th (113a-115a), also informing them

that their children would he assigned to Carver School

“until the Pupil Placement Board acts.” The Placement

Board acted on the same day (August 29) denying the

requests “ in accordance with” the 60-day rule (116a); the

parents were so advised by Mr. Hilton’s letter of August

30 (122a). The school year was scheduled to begin a few

days later on September 6, 1960 (72a). Upon receiving

notice of the Board’s action, the plaintiffs did not file a

further protest with the Placement Board as required by

the Placement Act (Code of Va., §22-232.8). They filed

this action on August 31, 1960 (la). Under the protest pro

cedure the Board is required to hold a hearing within 30

days after receiving a protest; before the hearing the

Board must first “publish a notice once a week for two

successive weeks in a newspaper of general circulation in

the city or county” involved indicating “ the name of the

applicant and the pertinent facts concerning his applica

tion, including the school he seeks to enter and the time and

place of the hearing.” At such a hearing any parent or

guardian of a child in the school involved is entitled to

intervene and participate. The Board is then allowed 30

15

days after the hearing to make its decision (Va. Code

§22-232.8).

Superintendent Horn testified that he had not taken any

action to advertise the 60 day rule in Roanoke County or

to make it known to anyone (51a-52a); that when Memo

randum No. 24 came to him from the Placement Board it

was merely kept on file (62a); that it was not reproduced

locally or distributed to principals, teachers, parents, the

press, or the School Board (52a). Mr. Hilton testified that

when the 60 day rule was adopted one cop}7 was sent to

each school superintendent (65a); that there was no re

quest that local authorities publicize the rule; and that

there was no publication of the rule in the form of a par

ticular notice in the newspapers (65a); but that there was

a general practice of releasing such information to the

Richmond, Virginia newspapers and the news wire ser

vices, the witness stating, “ I think that applied to this par

ticular release” (65a). There is no indication on the ap

plication forms that there is any deadline for applications

(P. P. B. Form No. 1; 101a).

Under the 60 day rule there was a slight variation in

the cut-off date in different communities around the State

(66a). It should be noted that as the rule was announced

July 17, 1959 (99a), less than 60 days prior to the 1959-60

school session, the first cut-off date to occur after the rule

was adopted was not until the summer of 1960.

Mr. Oglesby testified that the 60-day rule was applicable

only to pupils whose parents’ desires conflicted with the

local school board’s assignment recommendations (85a);

that transfers requested after the cut-off date would be

granted if there was no conflict between the parents’ de

sires and the local recommendations (86a-87a); that this

would be true in the case of administrative transfers such

as where a school burned down or a school became over-

16

crowded (87a); that the Board would accept the local rec

ommendation where a child enrolling for the first time

applied late (88a); and that there would he no attempt to

apply the rule where pupils moved into the system during

a school year (88a).

The text of the 60-day rule referred to “any transfer

request” (99a), but did not mention initial enrollments

in the schools. Mr. Hilton stated that he knew of no public

announcement that the rule also applied to original enroll

ments, but that this interpretation had been given to indi

vidual superintendents who had inquired (66a). The plain

tiff who applied for original enrollment in the first grade

was admitted at the all-Negro Carver school, but was not

permitted to attend the all-white school requested (67a-

70a).

On August 29, the same day the Placement Board denied

plaintiffs’ applications, it also adopted a new rule super

seding the 60-day rule (117a). The new rule mentioned

both “ applications for original placement” and for “ trans

fers” , fixed July 1 as the new deadline for filing with either

the Superintendent of Schools or the Placement Board

(the former rule referred only to filing with the Place

ment Board), and excepted cases of change of residence

after July 1 (117a).

The members of the Placement Board who were serving

when the 60-day rule was adopted resigned effective June

1, 1960 (71a).5 The new (and present) members did not

assume office and hold a meeting until about July 25, 1960

(71a; cf. 81a). During the period from June 1 to July 25,

1960, there was no Board functioning. Placement applica- 6

6 The former members were Messrs. Farley, Randolph and White.

See, Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960), describing

their segregation policies.

17

tions received in the Richmond office during this period

were held there but not approved until the new Board be

gan functioning (71a).6

6 The trial court refused to receive the depositions taken and

offered by the plaintiffs in evidence (26a-27a). Mr. Hilton’s depo

sition, excluded but a part of the record on appeal, contains some

slight amplification of the factual situation mentioned above (R.

47; depositions pp. 78-79) :

Q. Mr. Hilton, what happened to all the pupil placement

blanks, which were sent in to your office prior to the date

that the new Placement Board began to function, and sub

sequent to the date that the old Board ceased to function—

and what were the dates? A. The old Board resigned as of

June 1st. Those applications were placed in the files, awaiting

a Board to take action.

Q. Now, the dates of those were what? What date did the

old Board resign, effectively? A. As I recall, the old Board’s

resignation was June 1, 1960.

Q. And what was the date the new Board took over! A.

I can’t tell you the dates of the appointment. July, some time,

I believe—July, about the 25th or 26th, was the first meeting

of the new Board.

Q. In other words, during the period from July 1st to July

25th, or 26th, or whatever it was, there was no Board func

tioning at all? A. No, sir.

18

ARGUMENT

I.

Plaintiffs were excluded from the all-white Clearbrook

School by use of racially discriminatory rules and pro

cedures and are entitled to injunctive relief requiring

their admission.

A. Plaintiffs possessed all the qualifications required

of white pupils attending Clearbrook but were as

signed elsewhere on the basis of their race.

It is undisputed that the plaintiffs met the basic qualifi

cations required of white pupils attending Clearbrook

School, in that they lived within the school zone and were

in the appropriate school grades (40a, 49a). White pupils

living in the zone are routinely initially assigned to Clear

brook on the basis of their residence in the zone. This is

accomplished by local recommendations based on the school

zone, which are routinely approved by the Pupil Place

ment Board (36a-38a). Plaintiffs’ initial placement in

Carver school was based on race through use of the sepa

rate overlapping school zones for Negroes. Thus, plain

tiffs were forced to request transfers to obtain assignments

which white pupils similarly situated are granted as a

matter of course under the routine initial assignment pol

icy. Cf. Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961).

Similarly, one plaintiff, Barbara West, sought original

placement in the first grade at Clearbrook a right routinely

granted to white pupils living, as she did, in the zone.

B. The 60-day rule was unreasonable and racially

discriminatory as applied to appellants.

The conclusion of the Court below that plaintiffs’ trans

fer applications “were denied solely on account of the fact

19

that they were not timely filed”, and that the 60-day rule

was “ not unreasonable” , was the principal basis for denial

of the requested relief. Plaintiffs submit that the use of

the 60-day rule in the circumstances of their case was

unreasonable and racially discriminatory in that:

1. the defendants made no reasonable effort to make

the existence of the 60-day rule known to pupils and

parents in Roanoke County, and took no action to ad

vise the public of its applicability to some initial en

rollments ;

2. the 60-day rule is discriminatory and operates

to preserve segregation in that it is not applicable to

routine transfers or routine initial assignments recom

mended by local school authorities;

3. filing the applications prior to the deadline in

1960 would not have materially affected decision of the

applications since the Placement Board had no mem

bers at that time and did not begin functioning until

after the applications were submitted.

The record clearly reveals that none of the defendants

made any reasonable effort to publicize the 60-day rule in

Roanoke County (51a-52a; 65a). The memorandum con

taining the rule was sent by the Placement Board to the

Superintendent of Schools, who did nothing but place it

in his files. There was no official publication of the rule

anywhere.7 There was no effort by anyone to make the

60-day rule known in Roanoke County to pupils, teachers,

principals, parents, or even to the County School Board.

7 See the discussion in Davis, Administrative Law Treatise, Vol.

I, §6.11, on the egregious deficiencies of the states in disseminating

administrative regulations and making them accessible to the

public. Cf. the Federal Register System discussed in §§6.09-6.10.

Note the newspaper publication required for each pupil’s assign

ment hearing by Ya. code §22-232.8.

20

This regulation was little more than a private communi

cation passing from the Placement Board to Superinten-

dant Horn, and then to the latter’s files. It is true that the

Placement Board did make the rule “ available” to the

press when adopted. But this was in Richmond, Virginia,

not Roanoke County, and was in July 1959, almost a year

before the first cut-off date occurred under the rule. (The

record is silent as to which, if any, newpapers actually

published it.) Certainly this was no reasonable notice to

people in Roanoke County. The variability of the cut-off

date in different places (due to different opening dates for

schools) further lessens the possibility that press coverage

of the 1959 announcement could have been meaningful to

the public if there was any.

The Placement Board conspicuously failed to use the

most simple, efficient and obvious method of disseminating

the rule to persons concerned, namely, printing the rule

on the standard application form.8

It is submitted that it is a sheer denial of elementary

standards of fairness to hold the plaintiffs bound by an

administrative rule when no reasonable effort was made

to publicize the existence of the rule.9

“ To enforce such a statute would be like sanctioning

the practice of Caligula who ‘published the law, but

it was written in a very small hand, and posted up

in a corner, so that no one could make a copy of it.’

Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, p. 278.”

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91, 96 (1945).

Enforcement of the 60-day rule against plaintiff Barbara

West was completely unjustifiable for an additional reason.

8 This form, PPB Form No. 1, does not even provide a space for

parents to indicate their choice of schools (101a).

9 The applications were filed Ju|\| 16th. Plaintiffs were not even

told that they were late until August 29 (113a-115a).

21

The plain language of the rule referred only to transfers.

Defendants made no effort whatsoever to notify the public

that “ transfer request” included some applications for

original enrollment by new pupils. Mr. Hilton merely so

advised school superintendents who troubled to inquire

(66a).

The lack of publicity given to the 60-day rule is readily

understandable when its extremely limited applicability

is understood. On its face the rule applies to “ any trans

fer request” , but under the Placement Board’s policy, it

does not apply to any of the routine types of transfer

requests. It does not apply to cases of change of residence

during the school year or to any requested transfers

recommended local school authorities (85a-88a). Likewise,

it does not apply to every request for original placement,

only to those where parents and school authorities dis

agree.

This Court held in Jones v. School Board of the City of

Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72, 77 (4th Cir. 1960), that place

ment criteria applicable only to transfer requests and not

to applications for initial enrollment would be “ subject to

attack on constitutional grounds, for by reason of the

existing segregation pattern it will be Negro children,

primarily, who seek transfers.” Similar reasoning reveals

the discriminatory operation of the 60-day rule. Where

a placement rule, such as this deadline, is applicable only

to a limited class of transfers and initial enrollments de

fined by reference to local recommendations, and the local

recommendations are based on race under an invalid system

of separate school zones for whites and Negroes, it is

evident that any restriction made applicable only to per

sons who dispute the recommendations will be primarily

applicable to Negroes seeking to enter white schools. The

fact that the rule might in some cases apply to white

children (if, for example, they applied to a Negro school

22

or were protesting local school zones) does not validate

the rule. Its plain effect is to reinforce the segregated

situation by placing special restrictions on persons seek

ing a change. It should therefore be held invalid under

the reasoning of Jones v. School Board of the City of

Alexandria, supra. The holding in Jones has been followed

in Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798, 803 (8th Cir. 1961),

where the court directed an order requiring a school board

to make all initial assignments on the same basis used

to determine transfer applications. See also Mannings v.

Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370, 374 (5th Cir.

1960).

The racially discriminatory effect of the 60-day rule is

strikingly illustrated by the case of plaintiff Barbara

West, who applied for original enrollment in a first grade

class. She was permitted to enter a first grade class de

spite this “ late” application, as were white children who

applied to Clearbrook even “ later.” The difference in

treatment was that the white children in her area who

applied “ late” were allowed to go to Clearbrook (49a-

50a), while plaintiff was assigned to the all-Negro Carver

school. This discrimination is sought to be esplained by

the fact that all the “ late” applicants were assigned where

the local authorities recommended. But, we have already

seen that the recommendations are based on the unlawful

dual racial school zones. The 60-day rule’s effect is to

prevent a pupil from obtaining desegregation while not

affecting pupils who do not protest the routine racially

segregated assignments.

Finally, under the peculiar circumstances prevailing in

the summer of 1960, the plaintiffs’ delay in filing their

applications could not have materially affected the time the

Placement Board could act upon them, since the Place

ment Board had no members when the applications were

filed, and would have had the applications in ample time

23

for action when it did begin functioning if they had been

expeditiously handled by the local school authorities.

The Roanoke County schools opened on September 6,

1960. The deadline for receipt of applications by the

Placement Board was thus about July 8, 1960. Plaintiffs’

applications were delivered to Dr. Horn’s office nine days

later, on July 16, but the Placement Board had no mem

bers and was not approving applications from June 1

until the first meeting of the new members on July 2510

(71a). If the applications had been promptly forwarded

to the Placement Board when received in the superin

tendent s office they would have been available for action

when the new board began work on July 25. However,

0 I f the Court deems it necessary to consider the depositions (see

M S 6C o ^ % ’fi?27«TayTbvf COnsf dered even though excluded by the trial Court (26a-27a). The exclusion was contrary to the express

terms of Rule 26(d) (2), providing: P

“ The deposition of a party or of any one who at the time

o± taking the deposition was an officer, director, or managing

agent of a public or private corporation, partnership, or asso

ciation which is a party may be used by an adverse party for

any purpose.” 1 J

The trial Court erred in ruling that the depositions could be used

only for impeachment. 4 Moore’s Federal Practice 1190, P 6 .29 :

Rule 26 (d )(2 ) permits the deposition of a party to be

used by an adverse party for any purpose at the trial or hear-

w m e3fn u°Ugr party is Present at the trial and has testified orally. In that situation the deposition may be used

as evidence of an admission and may be introduced as inde

pendent or original evidence by the adverse party and not

26e(d ) ( l ) ° ” PUrp°SeS ° f lmPeacilment as provided in Rule

See Cleary v. Indiana Beach, Inc., 275 F. 2d 543 (7th Cir 19601

Sf/ p 7 T ° ° l « L ° ;

t 1 * •JR- J erv- 2d 30b'35’ Case J> 25 FRD 20 (N. D. Ohio 19601 •

Merchants Motor Freight, Inc. v. Downing, 222 F 2d 247 22 F r '

3 FwR'n f 2d 26d'43’ Case T 26 F. R. D. 116 (W. D Pa 1960) •

i ^ 2 , C i J S " ! ’ 266 R 2d 36°- 2 * K- St v - «

B; S\ Hl? ^ as the ehief administrative officer (Executive Secretary) of the Placement Board is plainly within the purview of Rule 26(d) (2). pmimy witum

24

Superintendent Horn held the applications for 19 days

to present them to the School Board (a departure from

the routine practice; 37a). When the School Board di

rected that they be sent to the Placement Board they were

still not sent for another eleven days.

It would have been a futile and vain act for plaintiffs to

have filed the applications at the time required by the

60-day rule since they could not have acted upon them at

that time in any event. The effect of the ruling below is

to penalize plaintiffs for not having done an act which

could not have made any difference had it been performed.

C. The Placement Board’s protest and hearing proce

dure was not an adequate and expeditious remedy,

as every court that considered it prior to this case

has held.

Plaintiffs’ applications were filed July 16th. They re

ceived no notice of their assignments until Superintendent

Horn’s letter of August 29 (113a-115a). Under the

procedure provided by Va. Code §22-232.8, plaintiffs could

not possibly have obtained a hearing and decision before

the beginning of the term on September 6. The protest

procedure requires a newspaper publication of a notice

once a week for two successive weeks prior to a hearing.

The Placement Board could take as much as 60 days after

a protest is filed before deciding it. Therefore, plaintiffs

filed this action on August 31, 1960, and sought to obtain

a preliminary injunction prior to the start of the school

session.

In Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke (W. D.

Va. July 1961), Judge Lewis held that plaintiff’s failure to

file a protest was justified as an “unusual circumstance”

where the Placement Board did not act until five or six days

before the school term began (see record in 4th Cir. No.

8534). In the instant case Judge Lewis pretermitted the

issue.

25

Plaintiffs’ decision not to pursue the protest machinery

was even more justifiable since every court that had

considered §22-232.8 had held that Negro pupils seeking

desegregation need not follow the procedure. Judge Hoff

man’s holding in Beckett v. School Board of City of

Norfolk, 185 F. Supp. 459 (E. D. Ya. 1959), aff’d sub nom.

Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960), while

relying in part on the Placement Board’s fixed opposition

to desegregation, was also based upon a determination

that the remedy was inadequate since the Placement Board

had not acted upon the applications until three days prior

to the school term and the protest procedures reqrured

so much time.

Prior to the Beckett case, Judge Bryan had reached a

similar conclusion on several occasions in the Thompson

case, infra. None of the Negro pupils who obtained ad

mission to white schools during the several years such

orders were issued in Arlington were required to follow

the protest machinery. This was true both before and

after the Placement Act amendments of 1958. Compare

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington County,

159 F. Supp. 567 (E. D. Va. 1957) (procedure is “ too

sluggish and prolix” ), aff’d 252 F. 2d 929 (4th Cir. 1957),

cert, denied 356 IT. S. 958, and Adkins v. School Board of

City of Newport News, 148 F. Supp. 430, 442-443 (E. D.

Va. 1957), aff’d 246 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1957), with Thomp

son v. County School Board of Arlington County, 166

F. Supp. 529, 531 (E. D. Ya. 1958) (after amendment to

present form, Placement Law held “ still not expeditious” ),

aff’d in part and remanded in part, sub nom. Hamm v.

County School Board of Arlington County, 263 F. 2d 226

and 264 F. 2d 945 (4th Cir. 1959). Judge Bryan rejected

the protest machinery as inadequate once more after the

invalidation of the massive resistance laws. Thompson v.

County School Board of Arlington County (E. D. Va.,

C. A. No. 1341, unreported “Memorandum on Formulation

26

of Decree on Mandate” dated June 3, 1959), holding that

Negro pupils could ignore the protest machinery because

it still was not expeditious.

The simple fact is that none of the dozens of Negro

pupils who obtained admission to white schools by court

orders in the Arlington County case,11 Fairfax County,12 13

or Alexandria13 school segregation cases were required to

pursue the Placement Board’s protest machinery.

There were similar rulings in the Charlottesville and

Floyd County cases by Judges Paul and Thompson, Allen

v. School Board of City of Charlottesville, 3 Race Rela

tions Law Reporter 937, 938 (W. D. Va. 1958); Walker

v. Floyd County School Board (W. D. Va., C. A. No. 1012;

Sept. 23, 1959, unreported).

Another equally fundamental reason why plaintiffs should

not be required to pursue the protest machinery is that

such a requirement would be, in itself, racially dis

criminatory in light of the assignment policies of the de

fendants. As was true with the 60-day rule discussed

above, the protest machinery never need be pursued by

a student seeking the local board’s recommendations which

are based on the invalid dual racial school zones. The

practice of initially assigning pupils on the basis of race

and then requiring a protest and hearing for a student

11 See for example Thompson v. County School Board, etc., 4

Race Rel. Law R. 609 (B. D. Va. July 25, 1959); 4 Race Rel. Law

R. 880 (E. D. Va. Sept. 1959) ; 5 Race Rel. Law R. 1054 (E. D. Va.

Sept. 16, 1960).

12 Blackwell v. Fairfax County School Board, 5 Race Rel. Law R.

1056 (E. D. Va. Sept. 22, 1960).

13 Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 4 Race Rel. Law

R. 31, 33 (E. D. Va. Oct. 22, 1958; Jan. 23, 1959; Feb. 6, 1959);

affd 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ; see also 179 F. Supp. 280

(E. D. Va. 1959).

27

to obtain a desegregated assignment is discriminatory,

especially where the assignment criteria used in deciding

protests are different from those applied in the initial

assignments. Beckett v. School Board of Norfolk, 185

F. Supp. 459 (E. D. Va. 1959), aff’d sub nom. Farley v.

Turner, supra; Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction,

211 F. 2d 370, 373 (5th Cir. 1960). In addition, the

machinery is designed to discourage dissidents by publiciz

ing the fact of their application in the press.

The protest and hearing procedure is an inadequate

remedy in that Negro pupils seeking desegregation start

it at a disadvantage since the racial initial assignments

require them to protest in order to obtain that which

white pupils obtain without protesting, namely, assign

ment in their zones of residence.

The protest machinery affords no means for correcting

the discrimination except in fortuitous cases, as the cir

cumstances of this case illustrate. Plaintiffs live in the

Clearbrook zone for white pupils, but the closest school

to their homes was actually Ogden School (54a), another

all-white school. Under the Placement Board’s established

criterion for cases where the parents and local authorities

disagree, namely, requiring pupils to attend the closest

schools to their homes and ignoring local school zones

(93a), the plaintiffs would not be able to qualify for

Clearbrook, the school white pupils in their zone attend

(even if they could satisfy the special academic criterion).

This vividly demonstrates the correctness of the holdings

in the Jones and Norwood cases, supra, condemning the

use of the different assignment criteria for transfers and

initial assignments. The policy of testing Negroes seek

ing admission to white schools by a proximity rule while

applying a zone rule to all others, is an obvious dis

crimination. Judge Michie so held in Jackson v. The School

Board of the City of Lynchburg, Va. (W. D. Va., C. A.

No. 534, January 15, 1962, not yet reported), stating:

If the Pupil Placement Board is not going to make

the initial placements of all public school students in

the state (and, as indicated above, it obviously cannot)

and if on appeal it is not going to consider whether

or not those placements have been made on a dis

criminatory and racial basis, then obviously the ap

peal to the Pupil Placement Board can afford no ade

quate remedy to those children who have been

discriminated against because of their race unless per

chance they happen to live nearer to the school they

wish to attend. Under these circumstances it would

be almost a cruel joke to say that administrative

remedies must be exhausted when it is known that

such exhaustion of remedies will not terminate the

pattern of racial assignment but will lead to a remedy

only in a few given cases based on geography—a

consideration which has been disregarded in the as

signment of white pupils.

D. Overcrowding at Clearbrook and the establishment

of a new all-Negro school in plaintiffs’ neighborhood

cannot bar their admission to Clearbrook.

The record shows that despite a slightly overcrowded

condition at Clearbrook school (23 above capacity on open

ing day; 35 over on October 1; 120a-121a),14 white pupils

who applied after plaintiffs did were accepted at Clear

brook under the routine practice (49a-50a). This is a plain

racial discrimination.

Overcrowding defenses were rejected as discriminatory

in Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington County,

14 Carver School where plaintiffs were assigned was also over

crowded ; 9 over capacity opening day, 56 over on October 1.

29

166 F. Supp. 529, 536 (E. D. Ya. 1958) (court approved

rejection based on overcrowding); case remanded 264 F. 2d

945 (4th Cir. 1959) (plaintiffs subjected “to tests that

were not applied to the applications of white students

seeking transfers” ) ; on remand, 4 Race Rel. L. Rep. 609,

610 (E. D. Ya., July 25, 1959) (overcrowding criterion

rejected as discriminatory). See also Clemmons v. Board

of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir.

1956).

The superintendent’s explanation that if these seven

pupils were admitted he might be required to admit 125

more Negroes, who had not applied for Clearbrook, cannot

justify the discrimination practiced against plaintiffs. A

similar argument was rejected and described as “ fraught

with unreality” in Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385, 386, 391

(3d Cir. 1960). If large numbers of Negroes had applied

for Clearbrook a different situation would have existed.

In the situation which did exist, plaintiffs were excluded

on an overcrowding standard not used to bar later white

applicants.

The construction of a new all-Negro school in the plain

tiffs’ neighborhood, as a planned and calculated part of

the defense to this case (118a), is equally unavailing to

bar the plaintiffs. The new school was planned so as to

maintain the segregated system with facilities to accom

modate the Negroes living in its area. White children in

the same area attend Clearbrook and were not placed on

the list for administrative reassignment to the new school,

as the Negroes were (95a-96a).

The effect of this action is no different from that in

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 283 F. 2d

667 (4th Cir. 1960), where Negro pupils were held entitled

to attend a desegregated school notwithstanding the

transformation of a near-by school to all-Negro use. Like

30

wise, in Dodson v. School Board of the City of Charlottes

ville, 289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961), a practice of assigning

white children living in the zone of the all-Negro Jefferson

school to other schools, while refusing to let Negroes living

in the Jefferson area transfer out, was held to be discrim

inatory at 442-443. See also, Taylor v. School Board of

the City of New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181, 185; 195 F.

Supp. 231 (S. D. N. Y. 1961), aff’d 294 F. 2d 36 (2d Cir.

1961), cert. den. 7 L. ed. 2d 339, condemning a prior prac

tice of allowing white pupils in a Negro school area to

transfer out while denying this right to Negroes.

II.

Appellants are entitled to an injunction restraining

defendants’ discriminatory assignment practices.

The court below refused to issue an injunction against

the defendants as prayed,15 holding that the Placement

Board’s practices and policies were justified and that the

County Board and Superintendent were not in fact per

forming assignment duties (127a-128a) and concluding that

there was no justification for entering a permanent in

junction. The case was dismissed and “ stricken from the

docket” (129a).

The undisputed evidence demonstrates that the County

School authorities have a system of recommending the

assignments of pupils in accordance with a dual system of

attendance areas based on race (37a); that the pupils in

the County are in fact attending school consistent with the

15 Part B of the Prayer for Eelief (13a) was modeled after the

language approved by this Court in School Board of City of

Charlottesville v. Allen, 240 P. 2d 59, 61 (4th Cir. 1956), and

directed to be used in Allen v. County School Board of Prince

Edward County, 266 F. 2d 507, 511 (4th Cir. 1959).

31

dual racial zones (31a-33a); and that neither the Super

intendent of Schools nor the Secretary of the Placement

Board could recall any case where the Placement Board

had not accepted the recommended assignment from Ro

anoke County (38a; 79-80a). The Placement Board’s an

nounced policy was to examine only those of the thousands

of placements involving a conflict between the parents and

local authorities (83a).

The Court’s finding that the County authorities did not

make “any recommendations in reference” to assignments

(124a), may and should be disregarded as a plain error

based upon no evidence. United States v. United States

Gypsum Co., 333 U. S. 364, 394-395 (1948) held that an

appellate court may disregard a trial finding under Rule

52(a) where “ left with a definite and firm conviction that

a mistake has been committed.” The testimony and docu

mentary evidence conclusively demonstrates that the County

authorities routinely recommend assignments and recom

mended the assignments of the plaintiffs to Carver School.

There is no evidence from wdiich even an inference that

the local authorities did not recommend assignments could

be drawn, and no relevant demeanor testimony which might

justify the finding—since all the evidence came from the

defendants themselves and from their records. (See pages

8-9, supra.)

The Court’s conclusion that the School Board and Divi

sion Superintendent “ do not make any assignments” (124a)

is true only in the sense that the Placement Board has

ultimate statutory authority to make assignments and its

staff rubber-stamps every application. But the undisputed

evidence shows that under the Placement Board’s policy,

local authorities exercise the decisive judgment in the vast

majority of cases since the Placement Board approves their

recommendations unless there is a protest. Proof that the

county authorities actually shape the assignment pattern

32

lies in the fact that pupils are actually attending school in

accordance with the school zone maps approved annually

by the County School authorities (31a-32a), while the

Placement Board has never even received or requested a

copy of the school zone maps (77a).

In Jack.son v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg,

Virginia (W. D. Va. C. A. No. 534, Jan. 15, 1962), not yet

reported, Judge Miehie appraised the relationship between

the Placement Board and local boards of education as

follows:

If the Pupil Placement Board is not going to fulfill

the duty, with which it has been charged by statute, of

making the initial assignments throughout the state

(and obviously it cannot), then the only remedy for the

discrimination found to exist in the initial assignments

is by injunction directed to the appropriate school

board and school officials who are in fact (though not

in theory) in charge of making the initial assignments.

When the initial assignments are admittedly made

on a racial basis as is the case here, and the Pupil

Placement Board on appeal to it will not consider

whether the initial placements have been made on a

racial basis but only the location of the appellant’s

home and, if that location would entitle him to go to

the school to which he has applied, his grades, re

quiring the exhaustion of such a “ remedy” wrnuld be

merely an exercise in futility.

It is apparent that the actual result of the defendants’

assignment policies (however the responsibility is allocated

between them) is the use of a dual system of attendance

areas based on race. This was condemned by this Court in

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d

72, 76 (4th Cir. 1960) in the clearest language before the

present case arose.

33

The reassignment policy, by which pupils initially placed

on , the basis of race are then required to meet special

residence and academic standards, having no relation to

the method of initial placement and the organization of the

pupils in the schools, in order to transfer, are equally clearly

invalid under numerous precedents. Jones v. School Board

of the City of Alexandria, supra; Hill v. School Board of

the City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960); Dodson

v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, 289 F. 2d

439 (4th Cir. 1961); Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th

Cir. 1961); Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277

F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960); Thompson v. County School

Board of Arlington County (E. D. Va. C. A. No. 1341,

Sept. 16, 1960), 5 Race Eel. L. E. 1056.

The School Board’s demonstrated practice of creating

further segregation by planning and constructing new

school facilities on a racial basis, administratively trans

ferring only Negro pupils to such schools, and staffing them

with all Negro personnel, is also an unconstitutional perpet

uation of segregation which is inconsistent with the school

authorities’ duty under Brown v. Board of Education, 347

IT. S. 483 (1954); 349 U. S. 294 (1955), and Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) to “ devote every effort toward

initiating desegregation and bringing about the elimination

of racial discrimination in the public school system” (358

U. S. at 7). It is equally clear that defendants are not

performing these duties when they continue to make initial

assignments on the basis of race and refuse to make plans

for eliminating the segregated system by creating a non-

raeial assignment system.

One of the traditional equity principles which Brown

requires the courts to use in shaping remedies in these

cases is the equitable principle of granting complete relief.

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 IT. S. 321, 329 (1944). The obliga

34

tion to grant complete relief, even when it benefits persons

not before the court, is evident, from Porter v. Warner

Holding Co., 328 U. S. 395, 398 (1946) where-the Court

said:

And since the public interest is involved in a pro

ceeding of this nature, those equitable powers assume

an even broader and more flexible character than when

only a private controversy is at stake. Virginian R.

Co. v. System Federation, R. E. I)., 300 US 515, 552,

81 L ed 789, 802, 57 S Ct 592. Power is thereby resi

dent in the District Court, in exercising this jurisdic

tion, “ to do equity and to mould each decree to the

necessities of the particular case.” Hecht Co. v. Bowles,

321 US 321, 329, 88 L ed 754, 760, 64 S Ct 587. It may

act so as to adjust and reconcile competing claims and

so as to accord full justice to all the real parties in

interest; if necessary persons not originally connected

with the litigation may be brought before the court

so that their rights in the subject matter may be deter

mined and enforced. In addition, the court may go

beyond the matters immediately underlying its equi

table jurisdiction and decide whatever other issues and

give whatever other relief may be necessary under the

circumstances. Only in that way can equity do complete

rather truncated justice. Camp v. Boyd, 229 US 530,

551, 552, 57 L ed 1317, 1326, 1327, 33 S Ct 785.

Indeed, Rule 54(c), F. R. C. P. requires the courts to grant

the relief to which the parties are entitled whether or not

demanded. , . , , i

The defendants argued below that under Carson v. War

ticle, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956), the plaintiffs could not

maintain a class action but in light of the pupil placement

law can only obtain individual relief for assignment to

35

particular schools. The. manner of the trial court’s citation

of Qarson v. Warticle, supra, indicates apparent agreement

with that view (126a).

Plaintiffs submit that Carson v. Warlick, supra; Coving

ton v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4th Cir. 1959) and Holt

v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265 F. 2d 95 (4th Cir.

1959), are inapplicable and do not support the proposition

that the courts are powerless to deal with discriminatory

assignment practices affecting pupils in a school system,

except by reviewing individual applications to a particular

school. This was the theory used to justify the trial court’s

action in McCoy v. Greensboro City Boa,rd of Education,

179 F. Supp. 745, 749-780 (M. D. N. C. 1959), which this

Court reversed, 283 F. 2d 667 (4th Cir. 1960). Actually,

the Carson, Covington and Holt cases held that injunctive

relief would not be granted where parties had failed to

pursue reasonable and adequate administrative remedies

under a pupil placement law. The Court in Carson made

it plain that it was not deciding what relief might be

granted where some individuals had exhausted their ad

ministrative remedies or where the remedies afforded were

inadequate or unreasonable. The Court said in Carson, at

238 F. 2d 724, 729:

“We are dealing here, of course, with the admin

istrative procedure of the state and not with the right