Rock v Norfolk & Western Railway Company Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 1, 1974

65 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rock v Norfolk & Western Railway Company Brief for Appellants, 1974. acfe5fbd-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/49973de6-0dc3-4911-b2b3-545b6917b31e/rock-v-norfolk-western-railway-company-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

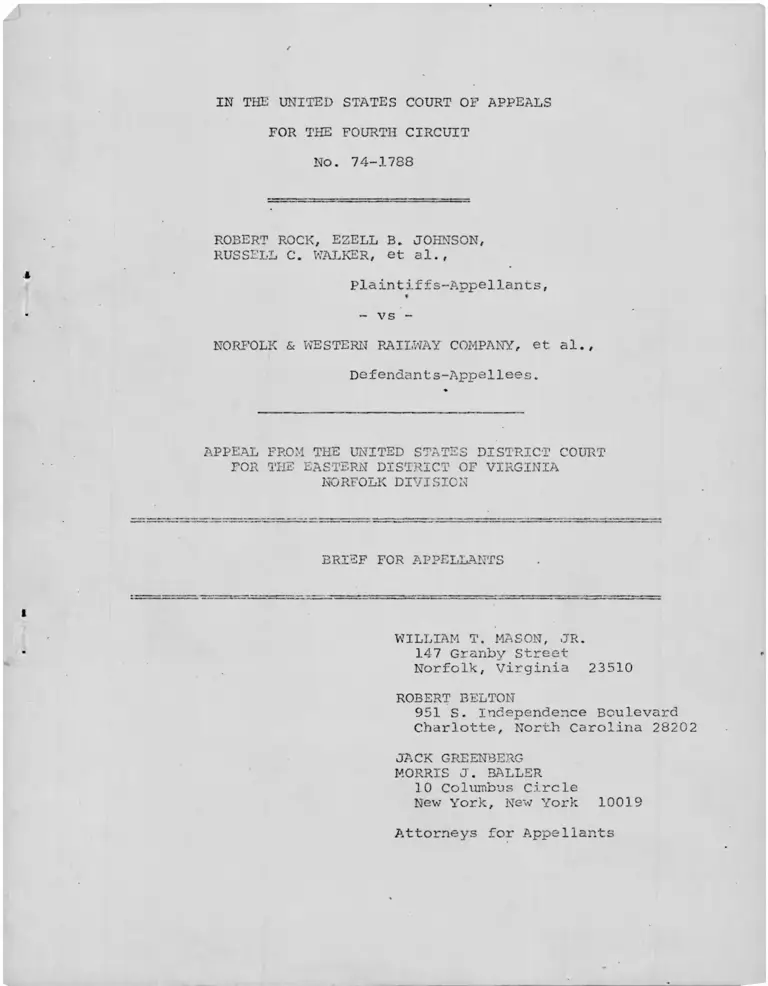

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 74-1788

ROBERT ROCK, EZELL B. JOHNSON,

RUSSELL C. WALKER, et al.,

Plaint if f s-.Appellants,

- vs -

NORFOLK & WESTERN RAILWAY COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

NORFOLK DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

WILLIAM T. MASON, JR.

147 Granby Street Norfolk, Virginia 23510

ROBERT BELTON951 S. Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

JACK GREENBERG MORRIS J. BALLER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for A,ppellants

INDEX

page

Statement of Questions Presented........ ............... 1

Statement of the Case. ................................ 2

Statement of Facts..................................... 6

4 A. Introduction........................ ............. 6

TB. Proof of Economic Loss by Barney Yard Workers..... 14

C. The Merger of Conductors' Rosters................. 21

D. Nickel Plate Merger Payments..................... 25

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ABUSED ITS DISCRETION BY

DENYING BACK PAY TO THE PLAINTIFF CLASS FOR

REASONS WHICH ARE UNFOUNDED IN THE RECORD

AND INADEQUATE IN LAW............................ 28

A. Members of the Plaintiffs' Class

Suffered Severe Economic Injury

Due to Defendants' Discriminatory

Practices.................................... 28

B. Controlling Principles of Law Require

An Award of Back Pay in Typical

Discrimination Cases Like This One........... 31

C. None of the Reasons Stated By The

District Court Justifies the Denial

of Class Back Pay Under Proper Legal

Standards.................................... 32

1. "Equal" pay rates and the separation

of Norfolk Terminal into two yards........ 32

2. N&W's alleged bona-fide offer of

dovetailing.............................. 35

3. The disparate promotion rate and its

causes................................... 39

4. The purportedly minor "degree" of

the discrimination....................... 42

D. Only Discrimination Can Explain the Economic

Disparities Shown by This Record............. 44

l

Pa^e

E. Back Pay and the Nickel Plate Merger

Payments..................................... 47

F. This Court Should Establish Proper

Guidelines for the Computation of Back

Pay Due the Class Members on Remand.......... 48

II. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN MERGING THE

CONDUCTORS' SENIORITY ROSTERS IN A

MANNER THAT UNNECESSARILY PROLONGS THE

IMPACT OF PAST PRACTICES OF DISCRIMINATION...... 49

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN’REFUSING TO

GRANT PLAINTIFFS AN UPWARD ADJUSTMENT IN

THE NICKEL PLATE MERGER'S MONTHLY WAGE

GUARANTEES....................................... 55

CONCLUSION............................................. 60

TABLE OF CASES

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp.,

495 F. 2d 437 (5th Cir. 1974) 36n,49

Bowe v. Colgate Palmolive Co., 489 F.2d 896

(7th Cir. 1973) ................................. 32,57

Corning Glass Works v. Brennan, 42 LW 4827

(1974)............. ............................... . 33n

Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

494 F. 2d 817 (5th Cir. 1974)....................... 32

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., __ F.2d

(5th Cir. No. 72-3239, June 3, 1974) ............ 32,35

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)....... 36,57

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 420 F.2d 1225

(4th Cir. 1970) 57n

Hays v. Potlatch Forests, Inc., 465 F.2d 1081

(8th Cir. 1972) ................................... 57

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870

(6th Cir. 1973).......................... 31,32,35,37n

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

491 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974)...... 32,33n,35,36n,43,49

Jurinko v. Wiegand Co., 477 F.2d 1038

(3rd Cir. 1973), vac'd & rem'd for further

consideration 42 LW 3246 (1973), original

opinion reaff'd, __ F.2d __, 7 EPD 5 9215

(3rd Cir. 1974)............................... 34

ii

Page

Manning v. General Motors Corp., 466 F.2d 812

(6th Cir. 1972) 33n

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134

(4th Cir. 1973) ....................... 8n,31,32,33n,34n,35,36,

44,46,48,57n

Peters v. Missouri-Pacific Railroad Co.,

483 F.2d 490 (5th Cir. 1973), cert. denied

414 U.S. 1002 (1973)....................................... 57

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F. 2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974).............. 31,32,35,36n, 49, 60

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed 404 U.S.

1006 (1971)........................... 8n, 31,33n, 34n, 35,36,46,

49n,57n,58,59

Rock v. Norfolk & Western Rwy. Co.,

473 F. 2d 1344 (4th Cir. 1973).......................... 51n,54

Rosen v. Public Service Gas & Electric Co.,

477 F. 2d 90 (3rd Cir. 1973)............................... 57

Rosen v. Public Service Gas & Electric Co.,

409 F. 2d 775 (3rd Cir. 1969).............................. 59

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348

(5th Cir. 1972)........................................... 43

Schaeffer v. Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 1002

(9th Cir. 1972)........................................... 33n

United States v. Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Co.,

471 F. 2d 582 (4th Cir. 1973)........................ 8n, 52,57n

United States v. Dillon Supply Co., 429 F.2d 800

(4th Cir. 1970)........................................... 57n

United States v. Hayes International Corp.,

456 F. 2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972).............................. 59

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451

F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 406

U.S. 906 (1972).......... ........................... 8n, 52,53nUnited States v. St. Louis-San Francisco R. Co.,

464 F.2d 301 (8th Cir. en banc 1972)........................ 8n

Statute:

Railway Labor Act 45 U.S.C. §151, et seq. 38n

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 74-1788

ROBERT ROCK, EZELL B. JOHNSON,

RUSSELL C. WALKER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

- vs -

NORFOLK & WESTERN RAILWAY COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From the United States District Court For

The Eastern District of Virginia - Norfolk Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of Questions Presented

The issues presented in this Title VII case involving

racial discrimination in employment are:

1. Did the district court err in denying back pay to the

plaintiff class, where —

a. Appellants proved that appellees' discriminatory

employment practices caused substantial economic loss to

black employees; and

b. The district court's reasons for the back pay

denial are unfounded in the record and discredited in

the law?

2. Did the district court err in ordering merger of former

ly separate seniority rosters for conductors in a manner that

carries forward the promotional disadvantages imposed on black

employees during past periods of 4iscrirnina"t-;'-on?

3. Did the district court err in refusing to correct

presently continuing discrimination in monthly wage guarantees

as part of appellants' entitlement topfull relief from the

economic effects of appellees' discriminatory practices?

Statement of the Case

Appellants are here for the second time seeking full vindi

cation of their right to be free and made whole from racial

discrimination in their employment by appellees. They take this

Title VII appeal from a final order entered May 17, 1974, by the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia,

MacKenzie, J., after proceedings on remand from this Court's first

decision in their case, 473 F.2d 1344 (No. 72-1777, February 13,

1973). This Court has jurisdiction over the appeal under 28

U.S.C. Section 1291.

Plaintiffs-appeHants Rock, Johnson, and Walker ("plaintiffs"

hereafter) embarked on the long road toward justice on May 15,

1967, by filing an EEOC charge against defendant-appellee Norfolk

& Western Railway Company ("N&W") on behalf of their then-local

union, all-black Local 974. They amended their charge on June 12,

1969, to include as respondents the predecessors of defendants-

-2-

appellees United Transportation Union ("UTU") and its virtually

1/all-white Local 550. Their charges alleged, and they have since

proved, comprehensive practices of employment discrimination by

the N&W, UTU, and Local 550.

Plaintiffs filed this class action suit under Title VII

on June 2, 1969 and filed an amended complaint on December 30,

2/1969 (A.I- 4a-10a). Their long road led to trial on the merits

held April 13-16, 1971, to a memorandum opinion by the district

court rendered January 20, 1972 (A.I. 32a-47a), and to a judgment

2/entered on April 28, 1972 (A.l. 66a-77a).

In that opinion, the district court found that N&W had

practiced past and continuing hiring discrimination which led

to the establishment of two racially segregated departments or

yards within its Norfolk Terminal (A.i. 39a-42a). The court below

failed, however, to hold defendants' lock-in seniority system,

which perpetuated the departmental segregation, unlawful; it sim

ply did not address the issue, believing it to be foreclosed by

the court's finding that the black and white yards were "entirely

T T At that time, the defendant international union was denomi

nated Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen ("BRT").

2/ Citations in the form "A.I.___" are to Volume I of the Appendix

filed by plaintiffs with this Court for their last appeal. Plain

tiffs will not again reproduce materials in that appendix, but

will refer to documents contained in those three volumes numbered

I, II, and III in the form indicated. Plaintiffs have filed a

Supplemental Appendix with documents relating to the remand pro

ceedings that followed their first appeal. Citations to that

appendix are in the form "App. ___. "

3/ The procedural history of this case to the point of the first

appeal is set out in plaintiffs' Brief for that appeal, pp. 2-5.

-3-

different" (A.1. 42a-43a). In its decree, the court enjoined the

hiring discrimination and, despite making no finding of seniority

discrimination, modified defendants' seniority system in order to

reduce "friction" (A.i. 45a). It ordered the separate, racially

identified seniority rosters existing in the separate yards merged

by "topping and bottoming," a partial and restrictive remedy (A.I.

44a, 46a) . Plaintiffs had sought the far more rapid and effective

remedy of merger by "dovetailing." The district court also sum

marily denied plaintiffs back pay (A.I. 46a). Plaintiffs appeal-

1/ed.

This Court handed down its opinion on February 20, 1973, 473

F.2d 1344 (App. 1-16). On the issue of seniority relief, the Court

held that plaintiffs were entitled to a dovetailing order and

remanded to the district court for implementation of such a plan

(473 F.2d at 1349, App. 13-14). It neither reversed nor affirmed

the district court's unexplained denial of back pay, but remanded

for reconsideration and for certain findings on disputed factual

and legal issues (473 F.2d at 1350, App. 15-16). In so ordering,

the Court noted,

Since we have concluded that the plaintiffs are

entitled to a more liberal form of merger of the

seniority rosters, it will be appropriate for the

district court to consider anew the issue of the

right of the plaintiffs to back pay against either

the railroad or the union, or both ...

After the filing and prompt denial of a Supreme Court petition

1/for certiorari by UTU (App. 17), the district court conducted full

IT The district court also found that UTU had unlawfully maintained

segregated local lodges and ordered their merger (A.I. 44a-45a).

This order was carried out and not appealed.

5/ The defendant unions in that petition urged that the district

court had abused its discretion in fashioning certain detailed pro

visions of its limited "topping and bottoming" plan. This Court had

not even commented on the same contention when UTU raised it by

cross-appeal (No. 72-1778) .

-4

remand proceedings.- It allowed the parties to conduct detailed

negotiations in an attempt to formulate an appropriate dovetailing

remedy for the seniority discrimination (App. 59, c_f. 473 F.2d at

1349, App. 14). The parties were able to narrow their differences

to a significant extent and left the Court with only a few specific

disputes to resolve in fashioning its dovetailing remedy (App. 59-

107). The court below received evidence and heard testimony

*

pertinent to these disputes, as well as to the back pay question,

at a day-long remand trial held October 4, 1973 (App. 50-323).

After receiving post-trial briefs and hearing oral argument, the

court below issued its Opinion and Order on May 17, 1974 (App. 18-

47) •

The May 17 decision again denied the plaintiff class back pay

(App. 23-26). This time the court gave four reasons in support

of its denial: (1) that plaintiffs had not shown that black jobs

were lower paying than white jobs (App. 23-24); (2).that N&W

had made a good faith offer to merge the segregated seniority lists

in 1968, which offer UTU rejected (App. 24); (3) that calculation

of damages resulting from discrimination would be "pure speculation"

(App. 24-25) ; and (4) that the trial court had only found "a very

bland discrimination" with which conclusion this Court had agreed

in its decision (App. 26).

The court also rejected out of hand plaintiffs' request that

the remedy include readjustment of discriminatory monthly wage

guarantees resulting from a previous N&W merger (App. 19). Its

only stated reason was that plaintiffs had not specifically raised

this issue until the remand proceedings (id.).

-5-

The court entered a comprehensive dovetailing plan (App. 28-

47). Most of the plan had been agreed to by the parties, but the

court resolved five contested issues (App. 19-23). Of signifi

cance to this appeal, the court resolved one of those disputes by

ordering, in effect, a partial "topping and bottoming" (albeit

one which the court labeled "dovetailing") of the seniority rosters

6/

for conductors, denying plaintiffs' prayer for a more effective*

remedy (App. 20-22).

Plaintiffs filed their second notice of appeal on May 29,

1974 (App. 48). They seek full relief with regard to back pay,

conductors' seniority, and monthly wage guarantees.

Statement of Facts

A . Introduction

The brief plaintiffs filed in their first appeal of this case

(No. 72-1777) contains a detailed statement of background facts

and information necessary to put the present issue into its full

context. See Appellants’ Brief filed July 31, 1972 (hereafter

"Br.") at 6-27. Rather than repeat that lengthy statement in full

here, we simply highlight the most basic facts and urge the Court

to refer back to the previous brief where greater detail is desired.

7/1. Background: A Pattern of Segregation.

N&W maintains two yards in its Norfolk Terminal. The

8/

larger is nearly all white and known as the CT Yard; the smaller,

—/ The second level position in the job sequence in both black and white yards, see p. 7 , infra.

7/ For a more detailed description, see Br. 6-14.

8/ The CT Yard was 96% to 99% white during the years pertinent to this record, 1965 to 1971 (A.I. 30a-31a).

the Barney Yard, is virtually all black (A.I. 40a). Local 48 of

UTU now represents all pertinent employees in both yards, but

prior to the district court's 1972 decree each yard was within the

jurisdiction of a separate, segregated local (A.I. 44a, 45a).

Within each yard N&W employs men in the three related jobs

of brakeman, conductor, and car retarder operator. Brakeman is

the entry level position; a brakeman may thereafter promote to

conductor and from there to car retarder operator. The three jobs

10/form a progression in wage rates. Men holding the same position

in either yard earn the same daily pay (A.I. 31a). Most men in the

CT Yard and a minority of men in the Barney Yard have regularly

scheduled work assignments which are obtained by bidding on the

basis of seniority, just like the typical manufacturing plant

worker. The balance of the yardmen work from a rotating list, the

"extra board," from which they are called on a "first in-first

out" basis. So long as a man stays on the extra board his seniority

is not a factor in assignments (A.I. 97a).

Plaintiffs have consistently maintained that jobs in the two

yards are substantially similar, particularly at the brakeman

level. The district court, mistakenly viewing this as the control

ling factual issue in the case, ruled against that position. It

found, "the work done in the two Yards is not the same, has only

!7 The Barney Yard work force was 92% to 98% black during the

years in question (A.I. 30a-31a).

10/ Shortly before the time of trial, brakemen earned $29.26 per

eight-hour shift, conductors $31.50, and car retarder operators

$32.66. These disparities among the jobs are comparable to those

existing throughout the pertinent period. See N&W's Further Answer

to First Interrogatories, filed December 7, 1970, Nos. VI(A), (C);

IV (A), (C).

9/

-7-

small vestiges of similarity, and, in fact, is an entirely different

trade" (A.I. 42a-43a). On appeal, however, after a careful reci

tation of some of the evidence plaintiffs presented on this question,

this Court rejected the district court's conclusion (473 F.2d at

1349, App. 11-12).

N&W achieved the near-total segregation of its Norfolk

Terminal Yards by a classically discriminatory pattern of hiring,

t

as the court below found and as this Court recognized (A.I. 39a-

42a, 45a; 473 F.2d at 1348, App. 9). It maintained separate hiring

offices in both of the segregated yards, with each office hiring%

for that yard only. Vacancies were never posted or advertised and

recruitment was carried out by word-of-mouth communication with the

respective segregated workforces of the two yards, quite naturally

resulting in referrals of "relatives and friends" of the incumbents

(A.I. 45a). This hiring system and its discriminatory results

remained in effect until the district court's injunction on May 1,

11/1972 (A.I. 41a-42a, 45a).

11/ cf- un-itpd States v. Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Co. , 471 F.2d

582,~586 (4th Cir. 1973); United States v. Jacksonville Terminal

Co., 451 F.2d 418, 448 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 406 U.S. 906

(1972); United States v. St. Louis-San Francisco R. Co., 464 F.2d

301 (8th~Cir. en banc 1972); Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d

791, 794-5 (4th Cir. 1971), cert. dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1971);

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134, 137 (4th Cir. 1973).

In-all of these cases, the original hiring discrimination occurred

only prior to the effective date of Title VII, July 2, 1965.

Post-1965 hiring under the discriminatory system was consider

able. With deference to this Court's correct general understanding

that "Railroad employment is contracting and the opening up of new

jobs is becoming increasingly rare" (App. 10, 473 F.2d at 1348),

we note that such is not the case here. Since July 2, 1965, N&W

had hired 115 new CT Yard brakemen (100 whites, 15 blacks) and 34

new Barney Yard brakemen (27 blacks, 7 whites) by the trial of

April, 1971 (A.I. 31a).

-8-

2. Defendants' Discriminatory Seniority System

As with most traditional seniority systems in the rail

road industry, defendants' collectively bargained seniority

arrangements (see A.III. 793a-802a) were designed to inhibit

movement of employees between different seniority units and promote

longevity and stability within seniority units. They succeeded.

At Norfolk Terminal, the Barney Yard formed one seniority

unit and the CT Yard a separate unit (A.I. 29a). A yardman could

transfer between units only at the price of forfeiting all his

accumulated seniority in the original unit and starting over as a

new man in the other unit (id.). Within each yard, separate

seniority rosters were maintained for brakemen, for conductors,

and for car retarder operators (A.I. 30a). N&W concedes that no

business necessity justifies this system (see Br. 38).

Against its backdrop of segregated yards brought about

by segregated hiring, defendants' arrangements form a familiar

example of a seniority system made unlawful by Title VII. See Br.

35-39. In its initial opinion the district court did not find the

system unlawful, but only "abrasive" (A.I. 45a). it based this

holding exclusively on the finding that work in the tv/o yards is

not "the same, nor is one more menial than the other" (jLcL ; see

also finding (9), A.I. 42a-43a). To eliminate the "friction"

caused by separate, segregated rosters — but not to remedy any

unlawful seniority system — the court below ordered the rosters

merged by "topping and bottoming" (A.I. 45a-46a, see A.I. 66a-69a

12/-- For a more detailed statement, see Br. 8, 24-26, 38.

12/

-9-

and 77a-l-77a-4).

On appeal, this Court specifically rejected the basis for the

district court's ruling — the finding of only "small vestiges of

similarity" between the yards — noting inter alia that "it is

contradicted both by the prior conduct of the railroad and by its

admissions in the record that a 'dovetailing' of the seniority

rosters in the two yards was practical" (App. 11-12, 473 F.2d at

1 3 /

1349). This Court held "topping and bottoming" inadequate as a

matter of law and ordered the court below to formulate a merger of

14/rosters by "dovetailing" (App. 14, 473 F.2d at 1349). On remand,

the district court entered a dovetailing decree (App. 19-23) from

which plaintiffs appeal in one respect involving the method of

consolidating the conductors' rosters. (See Argument II, infra).

This decree was to take effect on June 17, 1973.

15/3. The inequality of Economic Opportunity

Plaintiffs introduced a massive array of proof at the

first trial showing that work opportunities in the two segregated

yards were not only separate but also unequal. Defendants did not

meaningfully rebut any of that proof, then or later, and conceded

its major consequences (see infra). Since the main issue on this

appeal involves back pay, we focus here on the proof of economic

— f Once again on remand, the district court nevertheless stated, "we held that the two Yards were indeed separate and distinct.The appellate court agreed" (App. 26).

14/ The exact meaning and operation of both "topping and bottoming"

and "dovetailing" are spelled out at Br. 25. This Court accurately

summarized the differences at 473 F.2d at 134'8, App. 9-11.

15/ For a more detailed statement, see Br. 14-24. See also part B of this Statement of Facts, pp. 14- 21, infra.

-10-

disparities between the white and black yards, and the unlawful

practices which caused those disparities.

CT Yard men enjoy opportunities for more regular, more

frequent, and more secure work than their Barney Yard counterparts.

This advantage reflects the greater availability of work in the CT

Yard both in terms of greater demand for work per man and greater

stability of work demand. Plaintiffs proved with specificity that

furloughs (lay-offs) visit Barney Yard men far more frequently

than comparable CT Yard workers. The evidence as summarized in

plaintiffs' first Brief shows that

Barney Yard men are furloughed far more frequently

than CT Yard men of the same or less seniority (in

their respective yards); Barney Yard men are on

furlough status for a much greater number of days

and weeks in the aggregate, and usually for much

longer periods of time on particular occasions,

than CT men of the same or less company seniority;

and the danger of furlough continues until much

later in the career of Barney Yard men than in that of their CT Yard counterparts.16/

Br. at 16-17. Counsel for N&W in open court admitted this dispar

ity in the impact of furloughs (A.II. 775a).

At N&W as in most of American industry, when a worker is on

lay-off, he earns no wages.

The district court made no mention of these undisputed and

crucial facts in either of its opinions.

Further economic disparities result from differences between

the two yards in the rate and frequency of promotion of brakemen

This summary is based not merely on witness testimony, but on an exhaustive study of the furlough records of CT and Barney Yard

employees (A. III. 854a—904a) . Appendix A to the appellants'

earlier Brief analyzes these records with telling effect (Br. A-l A—2) .

-11-

into the higher-paying positions of conductor and car retarder

operator. There are far more promoted positions in the CT Yard

17/

than in the Barney Yard. This fact is shown both by the propor

tionately far greater numbers of CT Yard men holding seniority in

̂ ' 18/ promoted positions throughout the relevant years (A.I. 30a-31a),

and by the greater number of CT Yard men actually working or

regularly assigned to work in promoted positions on three randomly

. ’ 1 2 / chosen dates just prior to trial (A.III. 824a-823a). N&W's counsel

also admitted this disparity between the yards in open court (A.II.

/ ” " ---------— In large part this results from the composition of work crews

in the two yards: one conductor normally supervises two brakemen

in the CT Yard^ (A.I. 28a, 172a—173a, 177a; A.II. 514a); but a con

ductor s crew in the Barney Yard may have anywhere from two to ten

brakemen and averages six to eight (A. 1. 156a-157a; A.H. 492a,

514a). Thus at any one time a higher percentage of yardmen working the CT Yard are conductors.

Because of the nature of operations, there are slightly more

car retarder operator positions in the Barney Yard than in the CT

Yard (A. III. 824a-853a, see Br. 18, nn. 14-15 and Br. 19, n. 16).

But the number of positions involved is insignificant compared to

the number of conductor positions and combining the two still

leaves a greatly disproportionate number of promoted positions on the CT side (id.).

18/ From 1965 to 1971, the proportion of CT Yard men who had been

promoted above brakeman varied from 55.5% to 63.6%. The analogous

proportion of Barney Yard men ranged between 22.2% and 27.6%. On

the last date for which the record contains data, January 1, 1971,

the figures were: CT Yard — 210 promoted of 378 total, 55.5% pro

moted; Barney Yard — 38 promoted of 140 total, 27.1% promoted (A.I. 29a-31a; A.III. 805a-823a).

19/ The data is as follows (A.III. 824a-853a):

(i) December 7, 1970 (actually working) - 76 promoted CT men, 18 promoted Barney Yard men. Ratio (CT to Barney) 4.24 to 1.

(ii) March 12, 1971 (actually working) - 64 promoted CT men,11 promoted Barney Yard men. Ratio - 5.82 to 1.

(iii) March 15, 1971 (regularly assigned) - 87 promoted CT men, 20 promoted Barney men. Ratio - 4.35 to 1.

During this period, the ratio of all CT men to all Barney Yard

men was only about 2.7 to 1 (as of January 1, 1971) (A.I. 30a).

-12-

776a).

Of course, when a man works in a promoted position at Norfolk

Terminal, he earns several dollars per shift more than a brakeman.

See p. 7, n. 10, supra.

The district court did not deal with these facts in its

January 20, 1972 opinion. In its opinion on remand, the court

acknowledged the smaller number of promoted positions and the

slower rate of advancement in the Barney Yard (App. 24, 25), but

dismissed the proof of lag in Barney Yard promotions as an example

of plaintiffs' "speculative statistics," or "pure speculation,"

or the Barney Yard men's "personal choice [not to promote] ... a

2 0/

matter of personal whim and not opportunity" (App. 22, 25).

Plaintiffs also proved disparities in the promotion of yardmen

to the management positions of assistant yardmaster and yardmaster

21/(Br. 20-21)’. On this point the court below found discrimination

"to a degree" in its first opinion, since Barney Yard men were

"blocked" from those jobs by N&W's whites-only recruitment policy

(A.I. 42a, 46a). The court reiterated this view in its remand

22/opinion (App. 25).

— ‘ These characterizations are utterly without basis in, and con

trary to, the entire record (see pp. 40- 42, infra).

21/ Of 18 hourly workers promoted to management, 17 were whites,

and one was black. Nine of the whites previously worked in the CT

Yard; the one black came from the Barney Yard only in 1968 and only

after years of pressure from Barney Yard men in support of his

appointment (A.II. 519a-522a; A.III. 811a-812a, 915a).

22/ There the court remarks that "our view of the evidence indicates

only three yardmasters in twenty-five years" (App. 25). This view

is clearly erroneous and evidently reflects the court's misunder

standing that the seniority date appearing opposite each yardmas

ter ' s name on the brakeman's list (see, e.g., A.III. 811a-812a) is

his date of promotion to yardmaster. In fact it is his date of

initial hire by the Company. As the N&W official in charge of yard-

masters explained at trial, all 10 of the yardmen elevated to management had been so promoted within the last 15 years, at least three

of them since 1965 (A.II. 519a-521a).

13-

Finally, plaintiffs presented convincing evidence that N&W

had long denied then a $.40 per shift bonus payment (the "air hose

arbitrary") which it paid to CT Yard employees for performing

11/similar duties. See Br. 23. The district court has never entered

any findings or conclusions in regard to this element of plaintiffs'

economic injury.

B. Proof of Economic Loss by Barney Yard Workers

Plaintiffs proved at the initial trial that Barney Yard

employees had far more limited opportunities for income than CT

Yard employees because of differences in the nature of employment

in the respective yards (see A (3), supra). At the remand trial,

plaintiffs proved comprehensively and specifically the extent of

the losses thereby inflicted on Barney Yard men.

The source of the income disparities in this case is not any

differential in hourly or daily pay rates. As previously noted

(p. 7 , supra) and as stressed by the district court (App. 23), a

brakeman or conductor or car retarder operator in the Barney Yard

receives the same wage rate as his CT Yard counterpart in the same

classification. Plaintiffs have never contended or sought to prove

24/

otherwise at any stage of this litigation.

Plaintiffs have always insisted, and continue to insist, that

notwithstanding the identity of base wage rate scales, CT Yardmen

enjoy an enormous advantage over Barney Yard workers in terms of

HZ' After years of requests and negotiations, the "arbitrary" was

extended to Barney Yard employees in 1968 (A.III. 804a). There was

no change in their duties at this time (A.II. 555a).

24/ A minor exception amounting to $.40 per shift is the issue

concerning the air-hose arbitrary, see n. 23, supra.

-14-

total income. At no stage of the litigation has any defendant or

any court contended otherwise. These two uncontested facts are

consistent with each other because plaintiffs proved, also without

dispute, the major operative factors explaining the income dis

parity: (i) the lesser amount of work per man in the Barney Yard,

and the consequently greater exposure of Barney Yard brakemen to

furlough; (ii) the Barney Yard's smaller number and percentage of»

promoted positions paying substantially above the brakeman rate,

and the consequently lesser and slower accessibility of promotions

to Barney Yard employees. See pp. 11- 13, supra.

Plaintiffs introduced comprehensive evidence detailing the

substantial disparity between Barney Yard (black) incomes and CT

Yard (white) incomes at the remand trial. This data went basically

unchallenged by defendants and unmentioned by the court below.

The principal proof of income disparities on remand took the

form of an extensive, detailed analysis comparing gross incomes for

all CT and Barney Yard employees, provided by N&W from its records

2 5/

during remand discovery (Pi.Ex. R-l, R-2). The results of that

analysis are shown by a series of charts and tables, Pi.Ex. R-4

through R-15, R-19 (App. 365- 411), which compare the gross earnings

of Barney and CT Yard employees individually and in larger or

smaller groups, mostly (but not entirely) in terms of average

earnings for members of the groups, with breakdowns and statistical

•=iv These voluminous documents, while part of the record on appeal,

are not reproduced in the Appendix. All information appearing

thereon is concisely tabulated in Pi.Ex. 3-A and 3-B (App. 342-

364, see App. 249- 251).

-15-

controls for seniority (year of hire), time period (earnings years,

1965 through 1973), and part-time or part-year employment. See

explanations at App. 248- 286.

These analyses show a consistent pattern. Running through

them as an almost unvaried theme is proof that almost all CT Yard

employees earned substantially more than almost all similarly

situated Barney Yard employees invalmost every year from 1965

through 1973. Further, they show that the difference in earnings

between CT and Barney men of comparable seniority is substantial

rather than marginal in most cases. They show on the whole and on

the average a disparity of approximately $1,200 per man per year

— 17% of the average Barney Yard man's total earnings — between

CT Yard incomes and Barney Yard incomes.

More specifically, these exhibits — whose integrity and

26/accuracy were not contested below — contain the following:

— In the following discussion of plaintiffs' statistical and

graphic evidence, several concepts and terms are used as they were

at trial. "Earnings year" refers to calendar years in which a

particular employee or group of employees had income from N&W (App.

253). "Year of hire" is the year in which the employee's brakeman

seniority date falls (App. 254). "Seniority groupings" were twelve

carefully and objectively selected sets of years of hire, chosen

so that detailed comparisons could be made of men in the two yards

who had approximately the same amount of company (brakeman) senior

ity (App. 254). The twelve seniority groupings included, respec

tively, years of hire (1) 1925-1941, (2) 1945-1949, (3) 1951-1953,

(4) 1954-1955, (5) 1956-1957, (6) 1960-1961, (7) 1962-1963, (8)

1965-1967, (9) 1968-1969, (10) 1970, (11) 1971, (12) 1972 (id.).

(In years not listed none were hired.) All averages are, of

course, properly weighted averages (App. 265). "Partial earnings"

were defined in such a way as to allow for exclusion from averaging

of those employees who were not actively employed during the entire

year in question (App. 274-277, Pi.Ex. R-15, App. 403-406). The

employees were also tabulated on Pi.Ex. R-4 and R-5 according to

a code which indicates racial identification (App. 255).

-16-

i

(1) PI. Ex. r-4 (App. 364- 373 ) is a set of distribution

diagrams showing gross earnings of individuals in each year 1965-

1973, broken down by Yard (CT or Barney), race, seniority classi

fication (year-of-hire group), and income range (at $500 intervals).

It does not show averages, but actual incomes. R-41s distribution

shows a remarkably consistent pattern, with CT Yard employees'

incomes higher on the income range scale (farther toward the right)

than those of Barney Yard men. To simplify (but not distort) this

pattern, we may examine median incomes. The median income for

each yard in each year fell into the following ranges:

Yd./Yr. 1965

CT $7000-7499

BY $6000-6499

1970

CT $8000-8499

BY $7500-7999

1966 1967 1968 1969

$7500-7999 $7500-7999

$6000-6499 $6500-6999

1971 1972

$7500-7999 $8500-8999

$6500-6999 $7500-7999

1973

$7000-7499 $9000-9499

$6000-6499 $8000-8499

$11,000-11,499

$9000-9499

With remarkable consistency, the range of the median CT Yard income

exceeds that of the median Barney Yard income by $1,000.

A more detailed comparison of median incomes pits CT and

Barney medians within seniority classifications against each other

(where incomes exist within the classification for both yards).

The result may be expressed in tabular form (numbers refer to num

ber of seniority classifications).

Year CT Median Higher BY Median Higher Same Median

1965 6

1966 7

1967 6

1968 6

1969 7

1970 8

1 0

0 0

1 0

1 1

1 0

1 0

-17-

1971 8 0 21972 7 1 11973 7 0 2

Total 62 6 6

"thus, almost without exception, the median incomes of CT men

grouped by seniority classifications exceed those of their Barney

Yard contemporaries.

(2) Pi.Ex. R—5 (App. 374 - 382 ) is merely a summary and sim

plification of R-4 (App. 259 ). On it, the pattern of disparate

incomes becomes so plain that on inspection it immediately strikes

the eye.

(3) Pi.Ex. R-7 (App. 387 - 390 ), which summarizes and analyzes

the more detailed information contained in PI.Ex. R-6 (App. 383 -

386), compares average earnings of all CT and Barney Yard employees

broken down by seniority classification and earnings years. It

shows, again with remarkable consistency, that CT Yard employees

earned more than their Barney Yard contemporaries. We may summarize

the information contained in this table by the following chart.

(Figures listed show numbers of different years in which employees

in the yard and seniority classification indicated had a higher

income than their contemporaries in the other Yard.)

Seniority Classif1'n: 1925-41 1945-49 1951-53 1954-55 1956-57

CT Avg. Higher 4 8 9 9 9BY Avg. Higher 5 1 0 0 0

Seniority Classif1'n: 1960-61 1962-63 1968-69 1970 1971

CT Avg. Higher 9 9 6 4 2BY Avg. Higher 0 0 0 0 1

(No meaningful comparisons were possible for the 1965-67 or 1972

classifications.) Thus, in 69 of the 76 possible comparisons of

-18-

contemporaries, the CT men came out ahead. In the classifications

including all men hired between 1951 and 1970 — comprising

almost 90% of the employees in Norfolk Terminal (App. 342- 364) —

in no year did Barney Yard men earn as much as their CT Yard con

temporaries .

(4) Pi.Ex. R-9 (App. 392), which summarizes and analyzes the

more detailed information contained in Pi.Ex. R-8 (App. 391),

studies income disparities between contemporaneously hired CT and

Barney Yard employees not year-by-year (like R-6 and R-7), but as

overall annual averages for the nine-year period. The results show

that in every seniority classification but one (years of hire 1925-

1941), CT Yard employees out-earned their Barney Yard counterparts

by over $1,000 per man per year, and usually much more. The exact

differences are summarized in tabular form below. (The numbers

are differences between average CT income and average Barney

income; the negative number indicates a higher average for the

Barney Yard.)

Seniority Classif’n: 1925-41 1945-49 1951-53 1954-55 1956-57

Disparity — $190 $1032 $2478 $1740 $1705

Seniority Classif'n: 1960-61 1962-63 1968-69 1970 1971

Disparity $1644 $2096 $1098 $1726 $1591

(Meaningful comparisons could not be made for classifications 1965-

67 and 1972.)

(5) Pi.Ex. R—10, R—11, R-12, and R-13 (App. 393 - 401 ) contain

exactly the same types of information as do R-6 through R-9, in

the same format (App. 274, 280). The former series differs from

-19-

the latter only in that the averages were calculated "with partial

incomes excluded" (see n. 26, supra). The patterns shown by these

exhibits are precisely the same as the ones detailed above. In

fact, the summary chart of the set, R-13 (App. 401) , shows an even

more consistent and pronounced degree of CT Yard incomes' superi

ority over Barney Yard incomes than does R-9.

(6) Pi. Ex. R—14 (App. 402) £ulls together the information

contained in Pi.Ex. R-3 through R-9 and synthesizes it in the most

general format (App. 283). It deals not with employees divided

into different seniority classifications, but with all employees

of whatever seniority in each yard. It shows a dramatic disparity

in the overall average incomes of employees in the two yards in

every year.

Average Earnings Comparisons (All Employees)

Year 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969CT Avg. Income $6957 $7994 $7818 $73 59 $8571BY Avg. Income

Difference (CT- $5749 $5681 $6270 $6305 $6895

BY) $1208 $1813 $1548 $1054 $1676Ratio (CT/BY) 1.21 1.32 1.25 1.16 1.24

Year 1970 1971 1972 1973 1965-73CT Avg. Income $8026 $7332 $8594 $9662 $7978BY Avg. Income

Difference (CT-

$7454 $6398 $7884 $8949 $6793

BY) $572 $934 $710 $713 $1185Ratio (CT/BY) 1.08 1.15 1.09 1.08 1.17

Year in and year out CT Yard men out-earned Barney Yard men '

average of $1,185 per man per year. Put another way, the average

CT Yard income exceed the average Barney Yard man's income by 17%

each year.

We feel compelled to engage in this detailed recapitulation of

plaintiffs' evidence showing significant racially-identifiable

-20-

y

income differences because the district court made no findings

whatever on this evidence and it comes before this Court for

initial review. To the extent the court below made any finding

relating to the comparative earnings of Barney Yard and CT Yard2 7/

employees, it found that they were "exactly the same."

C. The Merger of Conductors' Rosters

In accordance with this Court's mandate, the court below

on remand developed and decreed a lengthy and technical plan for

the merger of seniority rosters by dovetailing (App. 28- 47).

Only one issue arising from that injunctive order is again before

the Court: the basic form of the dovetailing required to eliminate

past discrimination in promotions to conductor rank. Certain back

ground facts must be presented to place this issue in context.

In both yards, brakemen gain the opportunity to qualify as

conductors as N&W determines the need for additional conductors

in the order of their brakeman seniority (A.III. 798a-799a). A

brakeman must pass a conductor's test to qualify, and may choose

28/not to qualify; however, neither factor is an issue here. Con

ductor's seniority is established at the time the examination is

passed (id.). The crucial point is that the need for conductors

in the particular yard determines the demand for promotion of

brakemen, and thus the length of time brakemen must work before

27/ App. 23) (emphasis is original) . See p. 14, supra, for

explanation.

28/ In this event, the seniority roster is marked "Relq Rights-

Cond" next to his name (see, e.g., A.III. 805a-807a). Only thir

teen Barney Yard men have so opted, but of these at least six had

qualified for the higher position of car retarder operator (id.

805a, 809a) so that their relinquishment may have been to maximize

their access to the best job and at least does not indicate non-

promotability.

-21-

gaining the opportunity to promote.

The record contains a large body of uncontradicted evidence

showing that CT Yard men gain the chance to promote to conductor,

2 9/and do so, far more rapidly than their Barney Yard counterparts.

Every CT Yard brakeman hired on or before September 18, 1963 had

by the time of the initial trial (April, 1971) been offered the

opportunity to move up to conductor (A.III. 811a-815a, cf. 818a-

821a and 829a, App. 195, 202) . In stark contrast, no Barney Yard

man hired after March 18, 1956 had by the same time had any oppor-

30/tunity to promote to conductor (A.III. 805a-806a, cf. 808a). At

least 76 CT Yard employees who had been promoted to conductor had

brakeman seniority dates later than that of the youngest (latest-

hired) Barney Yard conductor (id.-), App. 409~410 )•

The disparate rate of promotion in the two yards reflects

the same pattern. Most CT Yard brakemen hired before 1964 were

promoted to conductor after 6-7 years as a brakeman (A.III. 811a-

815a, cf. 818a-821a and 829a). Two who testified, both whites

hired in 1961, had been promoted within three years of their hire

(A.II. 708a, 718a). Three of plaintiffs' witnesses, blacks also

hired in 1961, had never been promoted, even by the remand trial

(A. 1. 207a; A. II. 768a, 771a; App. 181) , nor had another Barney

.29/ The court below entered no finding on this point in its initial

opinion. In its remand decision it held that, "This may be true

. . . . Progression may be slower in one Yard than another, but

this is the nature of the work of the Yard, not the racial charac

teristics of those laboring therein" (App. 24) .

30/ While not explicitly in the record, we might note that no

other brakemen were promoted to conductor in either yard prior to

the remand trial, when the situation therefore remained as before.

-22-

Yard witness hired in January, 1957 (App. 148). Most of the

Barney Yard men who had received a chance to promote first had to

wait a period of 8-15 years after hire (A.I. 84a-85a, 147a, 192a-

193a, 198a, 360a; A.III. 805a-809a).

Because of the disparate rates and availabilities of access

to promotions, Barney Yard brakemen in two categories suffer

present disadvantage in terms of their conductor status, vis-a-vis

their CT Yard contemporaries. (i) Those Barney Yard men (hired

before March 18, 1956) who have been promoted carry a later senior

ity date on the Barney Yard conductor roster than the date that the

CT Yard brakemen hired at the same time carry on the other conductor

roster; and (ii) Barney Yard men hired between March 18, 1956 and

September 18, 1963 have never had the opportunity, as have CT

employees hired during this period, to qualify for conductor and

establish conductor's seniority.

At the remand trial, plaintiffs and the unions advanced con

flicting proposals on the form of dovetailing of the separate

conductors' rosters (App. 79-83). Plaintiffs proposed that the

merger would recognize "terminal seniority" dates, e.g., dates of

initial hire (see App. 29) to eliminate the two disparities listed 31/

above. The unions argued for a straight combining of the two

existing lists, carrying over onto the merged roster only the

previously-established dates on the separate conductors' rosters.

— / Plaintiffs' proposal also contemplated giving an adjusted

conductor's seniority date, based on terminal seniority date, to

any Barney Yard employee not previously offered an opportunity to

qualify as a conductor who did so successfully under other remedial

provisions of the dovetailing plan, e.g., paragraph 2 (c)(v) (App.

-23-

The Company maintained a neutral position on the two proposals,

but eliminated any business necessity objection to either one

(App. 246 ). It stated to the court, by counsel,

If you dovetail on conductor seniority it is

generally going to have the effect of younger

CT men being above older Barney Yard men who

are both conductors. If you dovetail by date

of hire it will be a more even mix. But either

way you do it is workable and acceptable to

the company. (Id.) *

Plaintiffs introduced detailed evidence showing the difference

in results between their proposal and the unions' (Pi.Ex. R-16,

App. 407- 410, explanation at App. 155- 159). As fairly representa

tive examples of these results, we spell out what that evidence

shows with respect to three Barney Yard men who testified. Plain

tiff Robert Rock, hire date 9-4-47, would under the unions' pro

posed dovetailing lose out in bidding competition to H. A. Green

(white), hire date 10-29-55, and 55 other CT Yard men junior to

Rock in terminal seniority but senior in conductor's seniority

(App. 407- 410). Plaintiff Russell Walker, hire date 8-10-55,

would under the unions' proposal lose competitions against F. E.

Henderson (white), hire date 7-6-57, and 37 other CT men junior

to him (id.). Witness Larry Walker (black), hire date 1-25-57

(and never offered a chance to promote, App. 148), would not have

any bidding rights as conductor, although 68 CT men hired after

him would (App. 407- 410). These anomalies in moving from brake-

man's to conductor's seniority in the context of a comparison of

the two yards reflect, of course, the factors discussed in part

A (3), supra, and at p. 21 above.

-24-

The district court, branding plaintiffs' proposal a plan

for "super-seniority" (App. 20, 22), ordered the conductors'

rosters merged on the basis of existing conductor seniority dates,

in accordance with UTU's wishes (App. 23).

D . Nickel Plate Merger Payments

In 1964 the N&W absorbed the Nickel Plate Railroad and its

employees through a merger (App. 223, 228, -233). As part of*

the merger agreement, N&W and UTU agreed on certain protective

provisions for N&W employees affected by the merger, and the Inter

state Commerce Commission adopted those provisions in approving the

merger (App. 223, 228). These provisions amount to a wage

guarantee agreement (App. 223).

Every yardman employed by N&W as of October, 1964 receives

a specified level of protection under this agreement (App. 233 ,

32/

304 ). The wage level guaranteed to each yardman reflects his

average monthly earnings in the one year period immediately prior

to the Nickel Plate merger (App. 224 ). The more a yardman worked

— and earned — during that period, the higher will be his present

monthly wage guarantee.

N&W's officials explained how wage claims under the protective

plan operate. The yardman submits a claim form showing his pro

tected wage level ("test period" wage) and his actual earnings for

the month pertinent to the claim, and asserting his availability

for more work had it been available and the amount consequently

due him (difference between guaranteed wage and actual earnings)

-li/ Employees hired after October 16, 1964, the effective date of

the merger, receive no wage protection under the plan (App. 233 ).

-25-

(App. 240 ). If the employee failed to accept or "protect" work

that he otherwise would have received, the amounts he thereby

failed to earn are deducted from the amount due, under the theory

that he failed to mitigate losses (App. 114-115, 229-231, 240).

Other than these elements of his claim, the claimant need submit

no further evidence and the Railway may not interpose other issues

(App. 240) . *

N&W regularly expends very considerable sums pursuant to the

Nickel Plate merger agreement. It had made some payments every

month for at least four years preceding the remand trial (App. 236)

In 1972, about $3,000,000 was paid out over the entire N&W system

(App. 224 ). At Norfolk Terminal alone, N&W paid $242,593 to

yardmen in the period January 1, 1971 through August, 1973 for an

average of roughly $7,500 per month (App. 411, 224-225)

Because of defendants' racially discriminatory employment

practices before 1965 and their pronounced effect on the relative

earnings of CT and Barney Yard employees during the 1963-1964 test

period, CT Yard employees presently carry far higher monthly wage

guarantees than comparable Barney Yard workers. An analysis of a

list showing protected income levels for CT and Barney Yard men

as of May, 1973 (App. 412-441) shows that CT Yard men carried

substantially larger monthly guarantees than Barney Yard men hired

33/

in the same year.

Several typical examples may be shown in tabular form

Year of Hire #CT Avg. CT #BY Avg. BY

1946 3 $1254 1 $10051947 2 $1092 3 $9921951 7 $1180 5 $8761955 12 $1031 10 $8681956 8 $989 12 $7781961 8 $911 9 $653

-26- (cont1 d)

The example of the individual employees who testified is also

instructive. Eddie Wilson (white), who during the test period was

a brand new brakeman in the CT Yard (seniority date 3-1-63, App.

137 ), worked five days a week and achieved a protected rate now

fixed at $912 per month despite being near the bottom of his

seniority list (App. 114 ). Wilson's protection level was by no

means unusual for the CT Yard; on the contrary he testified that

most CT Yard men carry an even higher guarantee (App. 143 ). Yet

Wilson's rate is higher than that of witnesses Reid and Walker,

both black Barney Yard men 7-8 years senior to Wilson (App. 148 ,

163), whose guarantees amount to $897 and $859.68 per month,

respectively (App. 150 , 171 ). Black Barney Yard man Thornton,

more nearly Wilson's contemporary (although also his senior by

18 months) had a guarantee of $300 less — $615.98 (App. 181 ,

182) .

33/ cont'd

1962 11 $900 6 $6541963 23 $897 4 $660

(Source: Pi.Ex. 25, App. 412 -441 ).

It is noteworthy that these averages correspond closely to

the individual figures presented in witness testimony, see infra.

-27-

ARGUMENT

I. the district court abused its discretion

BY DENYING BACK PAY TO THE PLAINTIFF CLASS

FOR REASONS WHICH ARE UNFOUNDED IN THE RECORD AND INADEQUATE IN LAW.

A. Members of the plaintiffs' Class Suffered Severe Economic

Injury Due to Defendants' Discriminatory Practices.

The record conclusively proves that there were consistent and

massive differences between the tojtal income of CT Yard employees

and that of similarly .situated Barney Yard employees. See pp. 14-21,

supra. Given the racial composition of the yards, these are also

white-black differences. For a typical or average Barney Yard man,

these differences amounted to a loss of just under $10,000.00 in

personal income between the effective date of Title VII and the

34/date of the remand trial.

Plaintiffs' evidence as to disparate incomes stands unrebutted.

N&W did introduce (without explanation) two admittedly incomplete

and unsystematic documents purporting to show a few isolated cases

in which some Barney Yard employees earned more than one or a

few CT Yard contemporaries (N&W Ex. 2, 3, App.442- 455, explained

at App. 305-307). This disproves nothing in plaintiffs' showing,

34/ We apply here the average annual disparity of $1,185.00 per

man per year (App. 402, p.20 supra) to the period of 8 1/4 years.

With more individualized calculations, plaintiffs could show

that many men actually had a lesser disparity, many had a greater

disparity, and a few may have had little or no difference. These

questions of individual calculation are not before the court, the

district judge having reserved them for later proceedings if the

court had reached the issue (A.i. 83a, App. 318-319 )•

-28-

since they never contended that every single Barney Yard Man earned

„ j yless than every single CT Yard man.

Beyond these minor quibbles, N&W attacked plaintiffs' proof

as failing to account for employee variables other than seniority—

factors such as military leave, sickness, willingness to work over

time, etc.— which also determine a railroad worker's income (App.

196-197/ 211/ 296)- All this might,, theoretically, be of some value

(although we can only guess to which side)— if there were any indi

cation in the record that these other variables would in fact have

made any difference in the pattern of income disparity. But there

is no such indication, statistical or otherwise. N&W did not

even try to elicit testimony that Barney Yard workers were sick more

often, and therefore accumulated less gross earnings; or that they

were more often on military leave, or less available to work over

time, etc., than whites. In fact, the available evidence indicates

that if some of these factors were included, the income disparities

would be even greater. See Pi. Ex. R-10 through R-13, comparative

36/income averages with partial earnings excluded (App. 393-401 ).

We invite the Court to compare plaintiffs' exhibits R-3

through R-15 with N&W Ex. 2 and 3 for thoroughness, reliability,

and fairness. we note also that a number of N&W "examples" involve

the few higher paid white Barney Yard workers and lower paid black

CT Yard employees (App. 297 -299). These anomalies were themselves

the product of racial discrimination.

36/ The exclusion of partial earnings would act as a control for

such factors as military leave or long-term disability or illness,

which would reduce incomes to the point where they did not figure

in the calculations on these exhibits.

-29-

N&W's theory is thus at best "pure speculation" in the true sense;

a hypothesis without attempted factual verification. And as a

matter of common sense it is extremely dubious that N&W's hypothesis

could account for any significant part of a disparity of nearly

$1200 per man per year.

We have exhaustively detailed the sources of this income dis

parity, rooted in the division between two yards with vast dif-

*ferences in opportunity for work, advancement and income (see pp.

10 - 14, supra). This Court has already recognized that the

placement of the black segment of the Norfolk Terminal workforce

into the inferior side of this division was racially discriminatory

(App. 9, 473 F.2d at 1348). The seniority system that kept them

there was likewise discriminatory and therefore required effective

remedial modification (App. 9-14, 473 F.2d at 1348-9). The

economic losses suffered by black Barney Yard employees are inci

dents of defendants' practices of discrimination in the "terms

and conditions" of employment in violation of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2000e-2 (a), (c) .

The court below did not explain the import of its conclusion

that "this is not the case of disparate wage levels in various

departments. . . [or] in which white jobs paid more than black

jobs; or . . . where Negro jobs were lower paying and less desirable"

(App. 23) . If this is a finding that blacks suffered no financial

disadvantage as a result of their confinement to the Barney Yard,

then it is clearly erroneous and must be reversed. If, on the

other hand, it stands for the obvious fact that hourly and daily

wage rates are equal for both yards, then it simply fails to address

the issue framed by this case. in either event this Court must

-30

conclude that income loss of a type compensable under Title

VII did occur, and consider whether to make the plaintiff class

whole by an award of back pay.

B. Controlling Principles of Law Require An Award Of

Back Pay in Typical Discrimination Cases Like This

One.

Section 706(g) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5(g),

provides the district courts with the power to frame appropriate

*remedies for employment discrimination "with or without back

pay." The district courts do not, however, have uncontrolled

and unreviewable discretion in exercising this choice. On

the contrary, that exercise of discretion must serve the re

medial purposes of Title VII and conform to standards announced

by the appellate courts including this Court. Moody v. Albemarle

Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134, 141-142 (4th Cir. 1973); see also

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co. (ACIPCO), 494 F.2d 211,

251-253 (5th Cir. 1974); and Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co.,

486 F.2d 870, 876-877 (6th Cir. 1973). In this Circuit the

governing standard is that implicit in Robinson v. Lorillard

Corp. , 444 F. 2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed. 404 U.S.

1006 (1971), and announced in Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co.,

supra at 142:

Because of the compensatory nature of a back pay

award and the strong congressional policy embo<died

in Title VII, a district court must exercise its

discretion as to back pay in the same manner it

must exercise discretion as to attorney fees under

Title II of the Civil Rights Act . . . Thus, a

plaintiff or a complaining class who is successful

in obtaining an injunction under Title VII of the

Act should ordinarily be awarded back pay unless

special circumstances would render such an award

unjust. [citations omitted.]

-31-

This same standard, has now been firmly adopted by the Fifth

Circuit, Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364,

1375 (5th Cir. 1974), Pettway v. ACIPCO, supra at 252-253;

Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 494 F.2d 817, 819 (5th

Cir. 1974); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398,

421-422 (5th Cir. 1974); and by the Sixth Circuit, Head v.

Timken Roller Bearing Co., supra at 876; and implicitly adopted

and explicitly applied by the Seventh Circuit Bowe v. Colgate

Palmolive Co., 489 F.2d 896, 902-904 (7th Cir. 1973), following

its prior decision in the same case, 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. 1969).

Each of these cases ordered an award of class wide back

pay in circumstances similar to, and in many instances far less

compelling than, those presented here. The Moody principle

supported by all these authorities requires a back pay award

in this case unless this Court finds "special circumstances

that would render such an award unjust". we turn next

to the reasons advanced, by the court below for denying back pay,

in light of this test.

C. None of the Reasons Stated By The District Court

Justifies the Denial of Class Back Pay Under Proper

Legal Standards.

The district court advanced four groups of reasons in its

remand decision for reaffirming its earlier unexplained denial

of back pay. None of these reasons stands up under established

legal principles and a review of the factual record.

1. "Equal" pay rates and the separation of

Norfolk Terminal into two yards.

The first set of reasons stated by the district court for

its denial of back pay is that Barney Yard jobs paid the same as

-32-

corresponding CT Yard jobs, that disparities in promotion rates

were characteristic of conditions in the two yards not of

the workers themselves, and that Barney Yard men had not

applied for CT Yard work (App. 23-24). The latter two reasons

amount to reliance on the fact that Norfolk Terminal contains

two different yards. The court erred in denying back pay for

these reasons. *

As discussed above, the court's conclusion regarding

relative pay in the two yards was either clearly erroneous or

wholly unresponsive to the issue here (seepp. 15-21.30,supra).

A railroad worker buys his family a home with his income, not

his hourly wage rate. As a matter of common sense and as a

matter of law, a loss of total income is just as much a loss

whether it results from diminished hourly pay in a particular

job ^ or from diminished hours of work at a given pay rate

(as here)— or from denial of equal opportunity to promote or

39/transfer into higher paying jobs (also as here). The court's

distinction has no substance.

This would be the typical Equal Pay Act case under 29 U.S.C.

Section 206 (d). See, for example, Corning Glass Works v. Brennan,

42 LW 4827 (1974). It is far less common in Title VII situations.

— cf. the female protective lav/ cases such as Manning v.

General Motors Corp., 466 F.2d 812 (6th Cir. 1972), and

Schaeffer v. Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 1002 (9th Cir. 1972).

Those cases, in contrast to this one, involved a mandatory state

statute presumed valid until held contrary to federal law. This

case involves voluntary acts of private discrimination. Cf.

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., supra at 1377.

2^/ The latter is the most frequent Title VII back pay sit

uation, as in Robinson and Moody, but in no logical way dis

tinguishable from the others.

-33-

The self-evident truth that slower Barney Yard promotion

rates resulted from employment needs there, as opposed to

mistreatment of Barney Yard employees as individuals, is like

wise a distinction without operative meaning for this case.

The plaintiffs base their case on the inequality of "terms and

conditions" of employment, including number and rate of pro-40/

motions, between the two yards. To concede the difference as

such can only strengthen— not rebut— the claim for back pay.

Finally, the court opined that no Barney Yard men applied

for CT Yard jobs. This too blinks at the nature of the case.

As this Court has noted, Barney Yard men had no seniority rights

to exercise in applying or bidding for CT Yard jobs (App. 5,

473 F.2d at 1346). Therefore to "apply" for such a job would

require the Barney Yard employee to forfeit his accumulated

seniority, which in this industry is regarded (as the court

below elsewhere noted) with "sanctity" (App. 25). Refusal to

commit seniority suicide under an unlawful seniority system

obviously cannot disqualify Barney Yard men from receiving

back pay. Cf_. Jurinko v. Wiegand Co. , 477 F.2d 1038 (3rd Cir.

1973), vac1d and rem1d for further consideration 42 LW 3246

(1973) , original opinion reaf f' d, ___F.2d ____, 7 EPD 5[9215

— In this respect the instant case exactly fits the pattern

of Robinson and Moody. There too the discrimination was not^

in maintaining lower paying jobs with less opportunity for ad

vancement, but in assigning only blacks to them and preventing

their movement to better jobs.

(3rd Cir. 1974).

More generally, the court below seems to have justified

its decision by the fact that Norfolk Terminal is and will

for a time remain divided into two distinct yards or depart

ments (App. 26, 28-30). This is yet another distinction with

out a difference. separate, segregated departments formed the

factual context in Robinson, Moody, Head, Johnson, Pettway

and Franks. Plaintiffs in a Title VII case need not prove

that there should be only one operational unit in order to

recover back pay. Economic discrimination can also exist be

tween separate racially identified departments, as it does here.

2. N&Ws alleged bona-fide offer of dovetailing.

The court below next recited a set of reasons related to

a purported offer by N&W to the defendant unions to negotiate

a merger of rosters in 1968 (App. 24 , A.Ill- 926a).

Our most basic response is that such an offer is irrelevant

to the back pay issue. In addition, the court1s factual

assertions in this regard are without foundation in the record.

The court placed heavy stress on N&W's bona fides in mak

ing the offer to negotiate a merger (A.I. 44a, App. 24). It

placed no emphasis on the fact that nothing came of the offer

and the rosters were merged, (by topping and bottoming) only in 1972

41/

^ The classes in Robinson and Moody, were of course _ in the

same situation. Applications for ^hlte^ ° ^ S. ^ i^ a^ 1p3y their seniority were not made an element of their back p y

claims.

-35-

at court order. This confounds the concerns of Title VII:

. . . good intent or absence of discriminatory

intent does not redeem employment procedures or

testing mechanisms that operate as “built-in

headwinds" for minority groups and are unrelated

to measuring job capability. . . .

Congress directed the thrust of the Act to the

consequences of employment practices, not

simply the motivation.

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 432 (1971). It follows

that good faith intentions to alleviate discrimination— as

distinct from actual results— provide no defense to a back

pay award. This Court long ago held that,

. . . back pay it not a penalty imposed as asanction for moral turpitude; it is compensation

for the tangible economic loss resulting from

an unlawful employment practice. Under Title VII

the plaintiffs’1 class is entitled to compensation

for that loss, however benevolent the motives for

its imposition.

Robinson, supra at 804; quoted with approval in Moody, supi.a

at 141. The Fifth Circuit has at least three times in recent

months vigorously rejected similar defenses based on good.

faith but ineffective efforts to clean house; the sixth Circuit

42/agrees.

Even apart from the legal insufficiency of the "offer" as

a back pay defense, the facts in this case argue strongly

——/ see Johnson, sup_ra at 1376; Pettway, supra at. 253; and.

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp. , 495 F.2d 437, 443

(5th Cir. 1974). ' In Baxter the Court held bluntly,

Even assuming that Savannah has taken actions in

good faith to dissipate its previous discriminatory

conduct, such actions are of little consequence

where, as the instant case reveals, economic loss

has occurred in the past and discrimination presently

-36-

against reliance on it to defeat the relief sought. As the

court below found, the proposal died because the union

defendants refused to consider it (App. 24; see Br. 26-27).

The plaintiffs are innocent and bear no part of the re

sponsibility for the failure of this purported initiative

by the Company.

The court however intimated, without so finding, that

plaintiffs knew of the merger offer in 1968 (App. 24). The

record refutes that guess. At trial, Robert Rock, the lead

plaintiff and in 1968 the chairman of the black local (A. I

100a), testified that he had never seen or heard of N&W's

letter to UTU (BRT) offering a merger of rosters (id. 127a-

129a). Maurice p. Haynes, in 1968 President and in 1971 acting

Local Chairman of the black union (A.I. 221a) likewise had no

knowledge of the offer (id. 247a). The International Vice

President of UTU in charge of the "offer" confirmed that it

42/ (Cont'd)

continues which results in financial deprivation to

a company's black employees. Whether ah employer

is beneficent or malevolent in implementing its

employment practices, the same prohibited result,

adheres if they are discriminatory; economic loss

for the class of discriminatees. In Title VII

litigation, neither benign neglect nor activism will

be judicially tolerated if the outcome of such prac

tices is racially discriminatory and results in mone

tary loss.

Id. In all three cases, the employer had actually implemented.

changes beneficial to black employees-not, like N&W, just brief

ly talked about them.

Accord; Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., supra at 877.

-37-

had not been communicated to the black union or its officers

(A.II. 763a-764a). Nobody testified that it had. The record

in fact contains nothing to support the district judge's

intuition of awareness on the part of Barney Yard leaders,

but on the contrary only unrebutted evidence to the contrary.

The trial court concluded its reasoning on the point by

presuming (without any reference to or foundation in the facts

of record) that plaintiffs had chosen to reject the dovetail

ing offer in 1968 (when as shown above they knew nothing

about it)(App. 24). This is of course pure speculation: no

party ever offered or even discussed a dovetailing merger with

plaintiffs at any time. indeed, the same international Union

Vice President., after denying that there had been any communi

cation of the company's offer to the black local, testified,

It is entirely possible and may be probable that

Brother Rock or Peanort or Haynes said, "let's

talk about dovetailing." It may have been, but

if they would I would have immediately discouraged

it as being impossible. So accordingly I do not

think that we gave it any consideration or even talked

about it. (A.II. 764a).43/

Finally, other undisputed facts of record severely

undercut the force of the finding that the 1968 offer was in

good faith. N&W fully expected union opposition to scuttle

its proposal when made (A.II. 607a). After its rejection by

UTU, the company took no further action: it did not inform

the black local of its offer or the failure of negotiations

and never again raised the issue with UTU (A.n. 630a-361a).

In 1969-1970 N&W and UTU engaged in 65 days of intensive col

lective bargaining during which the merger of rosters was

Of course, under the Railway Labor Act, 45 U.S.C. Section

151 et seq., a local union like the black local is powerless to

38-

never once mentioned by either party (A. II 700a 704a),

and emerged with the same old seniority system (id. 765a,

A. Ill 793a-802a).

Even if this Court accepts the finding that N&W made

the initial 1968 merger offer in good faith, the record shows

that subsequently N&W rejoined the defendant unions in dis

playing a callous disregard for the aspirations of Barney

Yard employees to gain equal access to CT Yard jobs. Such

is not the stuff of which back pay defenses are made, under

any view of the law.

3. The disparate promotion rate and its causes.

Recognizing that promotion to the higher paying positions

does come more slowly to Barney Yard brakemen, the court be

low characterized that disparity in part as a matter of ob

jective employment needs and. in larger part as a matter of

purely personal choice by Barney Yard employees (App. 25) .

In neither case, the court implies, is the resultant economic

loss the defendants' responsibility. As to the first expla-

nation--objective conditions--we have already shown that this

43/ (Cont'd)

negotiate with a carrier on its own for seniority rights.

All such negotiations must be conducted by the international

Union through its General Chairman (A. II 675a-676a, 682a- 684a). Therefore, the International's refusal to negotiate a

dovetailing rendered plaintiffs legally incapable of the act

of rejecting the offer, which the court below attributed to

them.

-39-