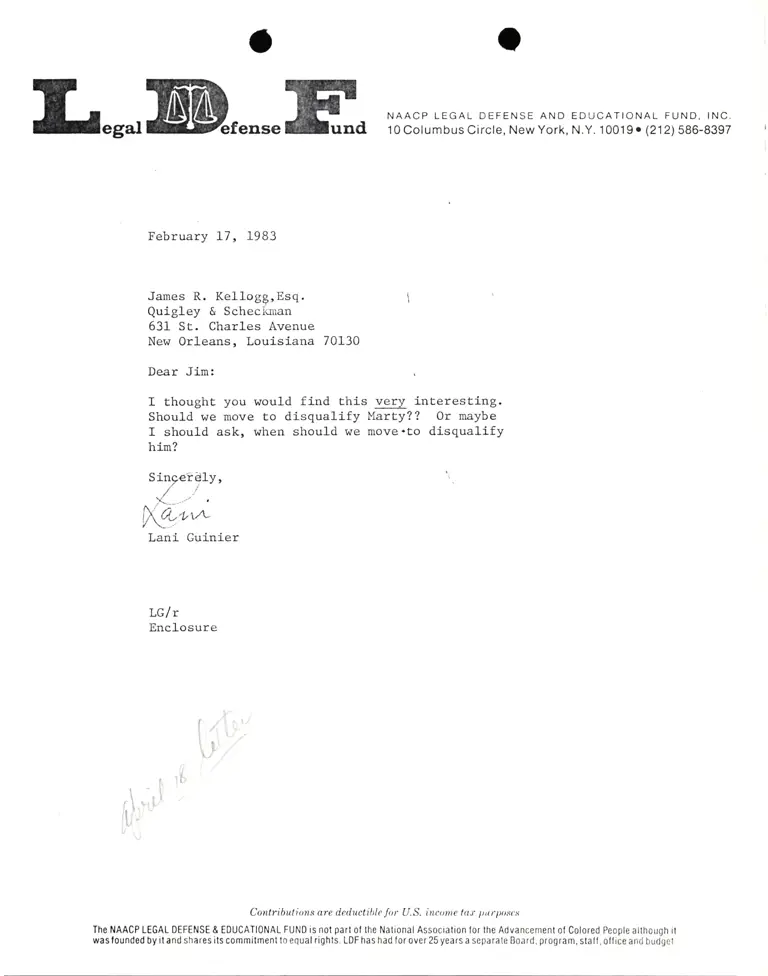

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to James R. Kellogg

Correspondence

February 17, 1983

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to James R. Kellogg, 1983. ce46fb84-e492-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/49a5109e-6352-4e34-974a-dd5200f71f07/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-james-r-kellogg. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Lesar@renseH"

February 17, 1983

James R. Kellogg,Esg. I

Quigley & Scheckman

631 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

|uliol,j, you would find this very interesting.

Should we move to disqualify Marty?? Or maybe

I should ask, when should we move'to disqualify

him?

Singe-rdly, '..

//(_ .,

fi,!,+'n

Lani Guinier

LGlr

Enclosure

Contributions are dcductihlo for U.S. in<ttme lo,t' pury)s(s

The NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATI0NAL FUN0 is not part ol the National Associalion,or the Advancement ol Colored People atthough it

was loundsd by it and shares its commilment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 25 years a seflara te Board, prog ram, stafl, olfice and budgel

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE ANO EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

lOColumbusCircle,NewYork,N.Y.l00l9o(212)586-8397 |

,t

\i

/1, r.

't'

l, -