Correspondence from Clerk to All Counsel

Public Court Documents

February 22, 1971

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Correspondence from Clerk to All Counsel, 1971. bc015949-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/49abe1c8-8731-488e-8067-79454f1346fc/correspondence-from-clerk-to-all-counsel. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

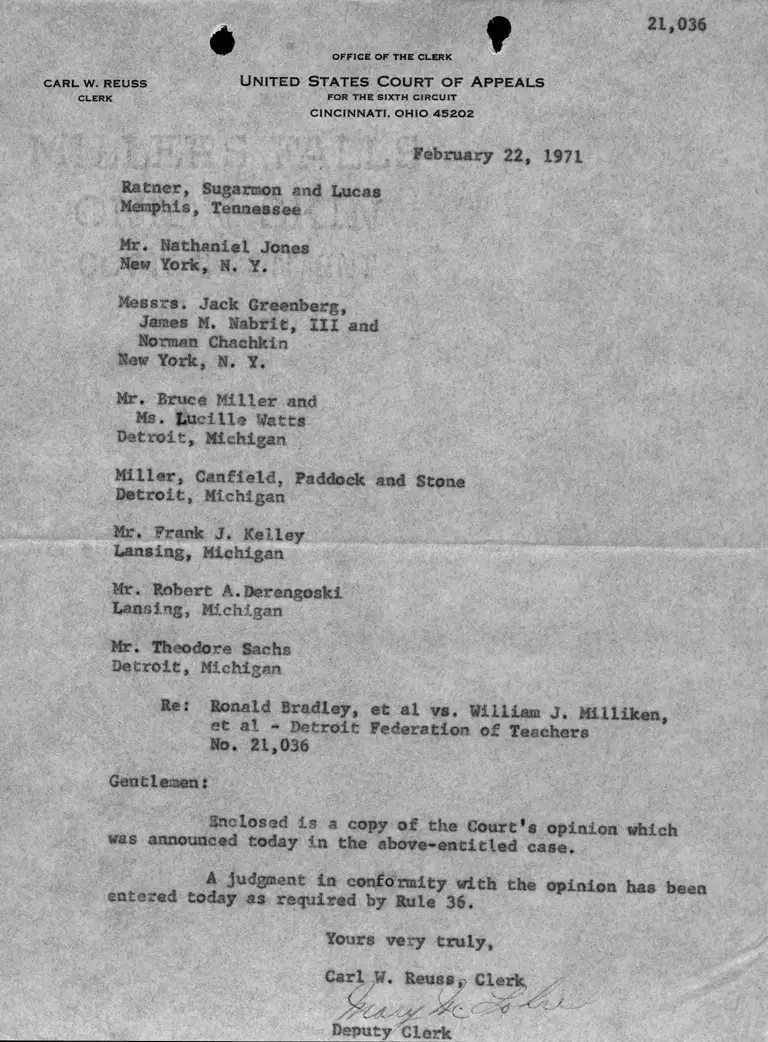

OFFICE OF THE CLERK

21,036

CARL W. REUSS

CLERK

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE SIXTH C IR C U IT

CINCINNATI, OHIO 45202

February 22, 1971

Eatner, Sugarmon and Lucas

;Memphis, Tennessee

Mr. Nathaniel Jones

New York, K. Y.

Messrs. Jack Greenberg,

James M. Nabrit, III and

Norman Chachkin

New York, N. Y.

Mr. Bruce Miller and

Ms. Lucille Watts

Detroit, Michigan

Miller, Canfield, Paddock and Stone

Detroit, Michigan

Mr. Frank J« Kelley

Lansing, Michigan

Mr. Robert A.Derengoski

Laos1ng, Mlchigan

Mr* Theodore Sachs

Detroit, Michigan

Re: Ronald Bradley, et al vs. William J. Milliken,

et a1 _ Detroit Federation of Teachers No. 21,036

Gentlemen:

inclosed is a copy of the Court’s opinion which

was announced today in the above-entitled case.

A judgment in conformity with the

entered today as required by Rule 36. opinion ha© been

Yours very truly,