Memorandum form Ganucheau (Clerk) to Counsel; Chisom v. Edwards Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

February 29, 1988

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Memorandum form Ganucheau (Clerk) to Counsel; Chisom v. Edwards Court Opinion, 1988. 01732963-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddbf119. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/49b3a373-4110-4617-84e3-e12630101094/memorandum-form-ganucheau-clerk-to-counsel-chisom-v-edwards-court-opinion. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

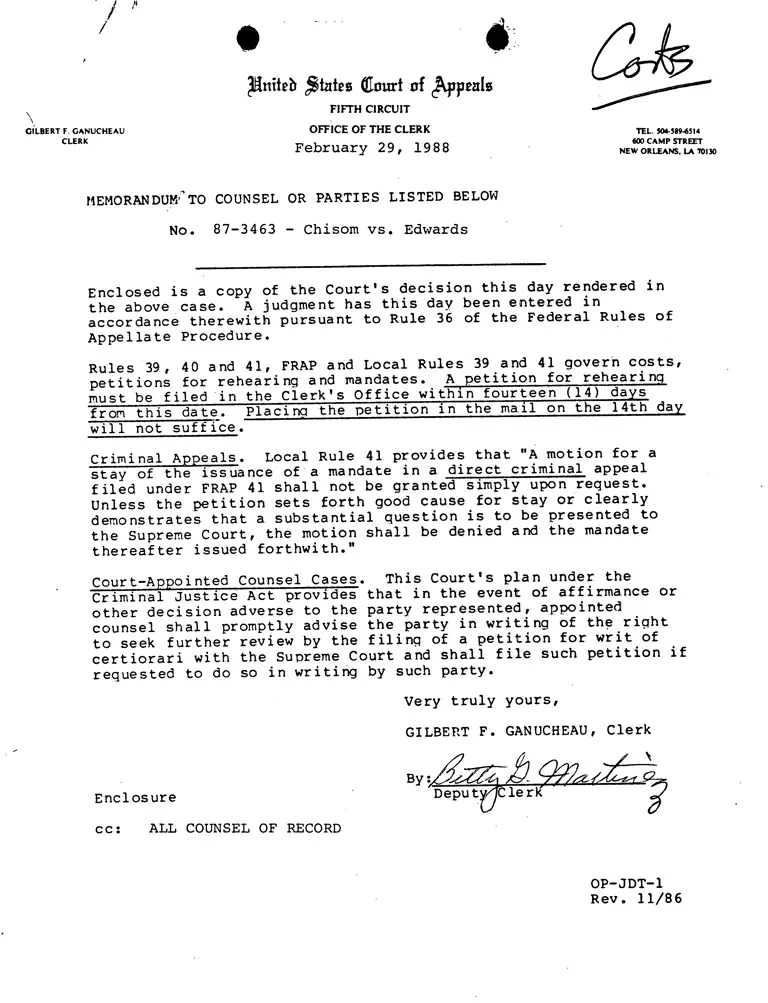

GILBERT F. GANUCHEAU

CLERK

40

pniteb $tates aloud of ppeals

FIFTH CIRCUIT

OFFiCE OF THE CLERK

February 29, 1988

MEMORANDUM' TO COUNSEL OR PARTIES LISTED BELOW

No. 87-3463 - Chisom vs. Edwards

TEL. 504-589-6514

600 CAMP STREET

NEW ORLEANS, LA 70130

Enclosed is a copy of the Court's decision this day rendered in

the above case. A judgment has this day been entered in

accordance therewith pursuant to Rule 36 of the Federal Rules of

Appellate Procedure.

Rules 39, 40 and 41, FRAP and Local Rules 39 and 41 govern costs,

petitions for rehearing and mandates. A petition for rehearing

must be filed Sin the Clerk's Office within fourteen (14) days

from this date. Placing the petition in the mail on the 14th day

will not suffice.

Criminal Appeals. Local Rule 41 provides that "A motion for a

stay of the issuance of a mandate in a direct criminal appeal

filed under FRAP 41 shall not be granted simply upon request.

Unless the petition sets forth good cause for stay or clearly

demonstrates that a substantial question is to be presented to

the Supreme Court, the motion shall be denied and the mandate

thereafter issued forthwith."

Court-Appointed Counsel Cases. This Court's plan under the

Criminal Justice Act provides that in the event of affirmance or

other decision adverse to the party represented, appointed

counsel shall promptly advise the party in writing of the right

to seek further review by the filing of a petition for writ of

certiorari with the Supreme Court and shall file such petition if

requested to do so in writing by such party.

Very truly yours,

GILBERT F. GANUCHEAU, Clerk

By: 112

Enclosure Deput Clerk

cc: ALL COUNSEL OF RECORD

OP-JDT-1

Rev. 11/86

CHISOM v. EDWARDS 2300

Ronald CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs—Appellants,

v.

Edwin EDWARDS, in his capacity as

Governor of the State of Louisiana,

et al., Defendants—Appellees.

No. 87-3463.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

Feb. 29, 1988.

Black registered voters in Orleans Par-

ish of Louisiana brought suit challenging

constitutionality of present system of elect-

ing Louisiana Supreme Court Justices from

First Supreme Court District. The United

States District Court for the Eastern Dis-

trict of Louisiana, Charles Schwartz, Jr., J.,

659 F.Supp. 183, dismissed, and voters ap-

pealed. The Court of Appeals, Johnson,

Circuit Judge, held that: (1) judicial elec-

tions are covered by Voting Rights Act

section which prohibits any law or proce-

dure which has effect of denying or abridg-

ing right to vote on basis of race, and (2)

complaint by black registered voters chal-

lenging current at-large system of electing

state Supreme Court Justices from their

district established theory of discriminatory

intent and stated claim of racial discrimina-

tion under Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments.

Reversed and remanded.

ing or abridging right to vote on basis of

race. Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 2, as

amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 1973.

2. Civil Rights c=13.4(6)

Elections

Discriminatory purpose is prerequisite

to recovery under Fourteenth and Fif-

teenth Amendments. U.S.C.A. Const.

Amends. 14, 15.

3. Civil Rights .c;13.12(3)

Elections c=.7

Complaint by black registered voters

challenging current at-large system of

electing state Supreme Court Justices from

their district established theory of discrimi-

natory intent and stated claim of racial

discrimination under Fourteenth and Fif-

teenth Amendments; voters cited history

of purposeful official discrimination on ba-

sis of race in state and existence of wide-

spread racially polarized voting in elections

involving black and white candidates, con-

cluding that current election procedures for

selecting Supreme Court Justices from

their area diluted minority voting strength.

U.S.C.A. Const.Amends. 14, 15.

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana.

Before BROWN, JOHNSON, and

HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judges.

JOHNSON, Circuit Judge:

Plaintiffs, black registered voters in Or-

1. Elections c=.12(l) leans Parish, Louisiana, raise constitutional

Judicial elections are covered by Vot- challenges to the present system of elect-

ing Rights Act section which prohibits any ing Louisiana Supreme Court Justices from

law or procedure which has effect of deny- the First Supreme Court District. Plain-

Synopsis, Syllabi and Key Number Classification

COPYRIGHT Lc) 19SS by WEST PUBLISHING CO.

The Synopsis, Syllabi and Key Number Classifi-

cation constitute no part of the opinion of the court.

2301 CHISOM v. EDWARDS

tiffs allege that the current at-large system

of electing Justices from the First District

impermissibly dilutes the voting strength

of black voters in Orleans Parish in viola-

tion of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, as amended in 1982 and the four-

teenth and fifteenth amendments. The dis-

trict court dismissed the section 2 claim

pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(6) for failure

to state a claim, finding that section 2 does

not apply to the election of state judges.

Concluding that section 2 does so apply, we

reverse.

The primary issue before this Court is

whether section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

applies to state judicial elections.

I. FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTO-

RY

The facts are undisputed. Currently, the

seven Justices on the Supreme Court of

Louisiana are elected from six geographical

judicial districts. Five of the six districts

elect one Justice each. However, the First

District, comprised of four parishes (Or-

leans, St. Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jef-

ferson Parishes), elects two Justices at-

large.

The population of the four parish First

Supreme Court District is approximately

thirty-four percent black and sixty-three

percent white. The registered voter popu-

lation reveals a somewhat similar percent-

age breakdown, with approximately thirty-

two percent black and sixty-eight percent

white. Over half of the four parish First

Supreme Court District's population and

over half of the district's registered voters

live in Orleans Parish. Importantly, Or-

leans Parish has a fifty-five percent black

population and a fifty-two percent black

registered voter population. Plaintiffs

seek a division of the First District into two

single-member districts, each to elect one

Justice. Under the plaintiffs' plan of divi-

sion, one proposed district would be com-

posed of Orleans Parish with a greater

black population and black registered voter

population than white. The other proposed

district would be composed of Jefferson,

Plaquemines, and St. Bernard Parishes;

this district would have a substantially

greater white population and white reg-

istered voter population than black. It is

particularly significant that no black per-

son has ever been elected to the Louisiana

Supreme Court, either from the First Su-

preme Court District or from any one of

the other five judicial districts.

To support their voter dilution claim,

plaintiffs cite, among other factors, a histo-

ry of purposeful official discrimination on

the basis of race in Louisiana and the exist-

ence of widespread racially polarized vot-

ing in elections involving black and white

candidates. Specifically, plaintiffs allege in

their complaint:

Because of the offical history of racial

discrimination in Louisiana's First Su-

preme Court District, the wide spread

prevalence of racially polarized voting in

the district, the continuing effects of

past discrimination on the plaintiffs, the

small percentage of minorities elected to

public office in the area, the absence of

any blacks elected to the Louisiana Su-

preme Court from the First District, and

the lack of any justifiable reason to con-

tinue the practice of electing two Justices

at-large from the New Orleans area only,

plaintiffs contend that the current elec-

tion procedures for selecting Supreme

Court Justices from the New Orleans

area dilutes minority voting strength and

therefore violates the 1965 Voting Rights

Act, as amended.

CHISOM v. EDWARDS 2302

On May 1, 1987, the district court, 659

F.Supp. 183, dismissed plaintiffs' complaint

for failure to state a claim upon which

relief may be granted. In its opinion ac-

companying the dismissal order, the district

court concluded that section 2 of the Vot-

ing Rights Act does not apply to the elec-

tion of state judges. To support this con-

clusion, the district court relied primarily

on the amended language in section 2

which states "to elect representatives of

their choice." The district court reasoned

that since judges are not "representatives,"

judicial elections are therefore not within

the protective ambit of section 2. Focusing

on a perceived inherent difference between

representatives and judges, the district

court stated, "[fludges, by their very defini-

tion, do not represent voters but are 'ap-

pointed [or elected] to preside and adminis-

ter the law.' " (citation omitted). The dis-

trict court further relied on what was un-

derstood to be a lack of any reference to

judicial elections in the legislative history

of section 2, and on previous court deci-

sions establishing that the "one person, one

vote" principle does not apply to judicial

elections. As to plaintiffs' fourteenth and

fifteenth amendment challenges, the dis-

trict court determined that plaintiffs had

failed to plead an intent to discriminate

with sufficient specificity to support their

constitutional claims. Plaintiffs appeal the

district court's dismissal of both their stat-

utory and constitutional claims.

Di In an opinion just released, the

Sixth Circuit, addressing a complaint that

the present system of electing municipal

judges to the Hamilton County Municipal

Court in Ohio violates section 2, concluded

that section 2 does indeed apply to the

judiciary. Mallory v. Eyrich, — F.2d

—, No. 87-3838, slip op. (6th Cir. Feb. 12,

1988). Other than our district court, only

two district courts have ruled on the cover-

age of section 2 in this context. The Mal-

lory district court, subsequently reversed,

concluded that section 2 does not extend to

the judiciary. Mallory v. Eyrich, 666

F.Supp. 1060 (S.D. Ohio 1987). The other

district court, Martin v. Allain, 658

F.Supp. 1183 (S.D.Miss. 1987), determined

that section 2 does apply to the judicial

branch. After consideration of the lan-

guage of the Act itself; the policies behind

the enactment of section 2; pertinent legis-

lative history; previous judicial interpreta-

tions of section 5, a companion section to

section 2 in the Act; and the position of the

United States Attorney General on this is-

sue; we conclude that section 2 does apply

to the election of state court judges. We

therefore reverse the judgment of the dis-

trict court.

II. DISCUSSION

A. The Plain Language of the Act

The Voting Rights Act was enacted by

Congress in 1965 for a broad remedial pur-

pose—"to rid the country of racial discrimi-

nation in voting." South Carolina v. Kat-

zenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 315, 86 S.Ct. 803,

812, 15 L.Ed.2d 769 (1966). Since the incep-

tion of the Act, the Supreme Court has

consistently interpreted the Act in a man-

ner which affords it "the broadest possible

scope" in combatting racial discrimination.

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S.

544, 565, 89 S.Ct. 817, 831, 22 L.Ed.2d 1

(1969). As a result, the Act effectively

regulates a wide range of voting practices

and procedures. See United States v.

Sheffield Board of Commissioners, 435

U.S. 110, 122-23, 98 S.Ct. 965, 974-75, 55

L.Ed.2d 148 (1978). Referred to by the

Supreme Court as a provision which

"broadly prohibits the use of voting rules

2303 CHISOM v. EDWARDS CHISOM v. EDWARDS 2301

to abridge exercise of the franchise on ra-

cial grounds," Katzenbach, 383 U.S. at 316,

86 S.Ct. at 812, section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, prior to its amendment

in 1982, provided as follows:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting, or standard, practice, or proce-

dure shall be imposed or applied by any

State or political subdivision to deny or

abridge the right of any citizen of the

United States to vote on account of race

or color, or in contravention of the guar-

antees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of

this title.

Congress amended section 2 in 1982 in

response to the Supreme Court's decision in

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct.

1490, 64 L.Ed.2d 47 (1980), wherein the

Court concluded that section 2 operated to

prohibit only intentional acts of discrimina-

tion by state officials. Thereafter, Con-

gress, in disagreement with the high court's

pronouncement, amended section 2 with lan-

guage providing that proof of intent is not

required to successfully prove a section 2

violation. Instead, Congress adopted the

"results" test, whereby plaintiffs may pre-

vail under section 2 by demonstrating that,

under the totality of the circumstances, a

challenged election law or procedure has

the effect of denying or abridging the right

to vote on the basis of race. However,

while effecting significant change through

the 1982 amendments, Congress specifical-

ly retained the operative language of origi-

nal section 2 defining the section's cover-

age—"[n]o voting qualification or prerequi-

site to voting or standard, practice, or pro-

cedure shall be imposed...." Section 2, as

amended in 1982, now provides:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequi-

site to voting or standard, practice, or

procedure shall be imposed or applied by

any State or political subdivision in a

manner which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of

the United States to vote on account of

race or color, or in contravention of the

guarantees set forth in section

1973b(f)(2) of this title, as provided in

subsection (b) of this section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is es-

tablished if, based on the totality of cir-

cumstances, it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or elec-

tion in the State or political subdivision

are not equally open to participation by

members of a class of citizens protected

by subsection (a) of this section in that

its members have less opportunity than

other members of the electorate to par-

ticipate in the political process and to

elect representatives of their choice.

The extent to which members of a pro-

tected class have been elected to office in

the State or political subdivision is one

circumstance which may be considered:

Provided, That nothing in this section

establishes a right to have members of a

protected class elected in numbers equal

to their proportion in the population.

Section 14(c)(1), which defines "voting"

and "vote" for purposes of the Act, sets

forth the types of election practices and

elections which are encompassed within the

regulatory sphere of the Act. Section

14(c)(1) states,

The terms "vote" or "voting" shall in-

clude all action necessary to make a vote

effective in any primary, special, or gen-

eral election, including, but not limited

to, registration, listing pursuant to this

subchapter or other action required by

law prerequisite to voting, casting a bal-

lot, and having such ballot counted prop-

erly and included in the appropriate to-

tals of votes cast with respect to candi-

dates for public or party office and prop-

ositions for which votes are received in

an election.

Clearly, judges are "candidates for public

or party office" elected in a primary, spe-

cial, or general election; therefore, section

2, by its express terms, extends to state

judicial elections. This truly is the only

construction consistent with the plain lan-

guage of the Act.'

In Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 831

F.2d 246 (11th Cir.1987), the Eleventh Cir-

cuit addressed the issue of the coverage of

section 2. In Dillard, the court rejected

the defendant county's implicit argument

that the election of an at-large chairperson

of a county commission was not covered by

section 2 due to that position's administra-

tive, as opposed to legislative, character.

The Dillard court stated,

Nowhere in the language of Section 2

nor in the legislative history does Con-

gre.,s condition the applicability of Sec-

tion 2 on the function performed by an

elected official. The language is only

and uncompromisingly premised on the

fact of nomination or election. Thus, on

the face of Section 2 it is irrelevant that

the chairperson performs only adminis-

trative and executive duties. It is only

relevant that Calhoun County has ex-

pressed an interest in retaining the post

as an electoral position. Once a post is

open to the electorate, and if it is shown

that the context of that election creates a

discriminatory but corrigible election

practice, it must be open in a way that

allows racial groups to participate equal-

ly.

Id. at 250.

The State asserts that by amending sec-

tion 2 in 1982, Congress intentionally graft-

I. Evidence of congressional intent to reach

all types of elections, regardless of who or

what is the object of the vote, is the fact that

ed a limitation on section 14(c)(1) that "can-

didates for public or party office" only

include "representatives"; since judges are

not "representatives," state judicial elec-

tions are exempt from the protective mea-

sures of the Act. In making this conten-

tion, the State, as well as the district court,

points to the distinctive functions of judges

as opposed to other elected officials. Spe-

cifically, the district court, citing Wells v.

Edwards, 347 F.Supp. 453 (M.D.La. 1972),

affd, 409 U.S. 1095, 93 S.Ct. 904, 34

L.Ed.2d 679 (1973), notes that the "one

person, one vote" principle of apportion-

ment has been held not to apply to the

judicial branch of government on the basis

of this distinction. See also Voter Infor-

mation Project v. City of Paton Rouge,

612 F.2d 208 (5th Cir.1980). In Wells, the

plaintiff sought reapportionment of the

Louisiana Supreme Court Judicial Districts

in accordance with one person, one vote

principles. The Wells court rejected the

plaintiff's claim, reasoning that the "pri-

mary purpose of one-man, one-vote appor-

tionment is to make sure that each official

member of an elected body speaks for ap-

proximately the same number of constitu-

ents." Wells, 347 F.Supp. at 455. The

district court then concluded that since

judges do not represent, but instead serve

people, the rationale behind one person, one

vote apportionment of preserving a repre-

sentative form of government is not rele-

vant to the judiciary. Id.

In Voter Information, this Court, bound

by the holding in Wells due to the Supreme

Court's summary affirmance of that deci-

sion, rejected the plaintiffs' claim for reap-

votes on propositions are within the purview

of the Act. Section 14(c)(1).

2305 CHISOM v. EDWARDS CHISOM v. EDWARDS 2306

portionment of judicial districts on the one

person, one vote theory. Voter Informa-

tion, 612 F.2d at 211. However, the Voter

Information Court then emphasized that

the plaintiffs further asserted claims of

racial discrimination under the fifteenth

amendment which resulted in the dilution

of black voting strength. Recognizing the

difference between the two types of claims,

the Court expressly rejected the applicabili-

ty of the Wells decision to claims of racial

discrimination, stating,

[T]he various 'one man one vote' cases

involving Judges make clear that they do

not involve claims of race discrimination

as such.

To hold that a system designed to di-

lute the voting strength of black citizens

and prevent the election of blacks as

Judges is immune from attack would be

to ignore both the language and purpose

of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend-

ments. The Supreme Court has fre-

quently recognized that election schemes

not otherwise subject to attack may be

unconstitutional when designed and oper-

ated to discriminate against racial minori-

ties.

Id. (footnote omitted).

We, like the Voter Information Court,

are bound by the Supreme Court's affirm-

ance of Wells and its holding that the one

person, one vote principle does not extend

to the judicial branch of government.

2. The distinction between equal protection

principles applicable to claims based on one

person, one vote principles of apportionment

and those based on racial discrimination is

not without prior Supreme Court precedent.

See White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 93 S.Ct.

2332, 37 L.Ed.2d 314 (1973) (Court reversed

decision of district court that reapportion-

ment plan for Texas house of Representa-

tives violated one person, one vote princi-

ples, but affirmed the district court's conclu-

However, the district court's reliance on

Wells in the instant case is misplaced as we

are not concerned with a complaint seeking

reapportionment of judicial districts on the

basis of population deviations between dis-

tricts. Rather, the complaint in the instant

case involves claims of racial discrimination

resulting in vote dilution under section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act and the fourteenth

and fifteenth amendments. Therefore, the

district court erred to the extent it relied on

Wells in support of its conclusion that sec-

tion 2 does not apply to the judiciary.2

The Voting Rights Act was enacted, in

part, to facilitate the enforcement of the

guarantees afforded by the Constitution.

Indeed, section 2, as originally written, no

more than elaborated on the fifteenth

amendment, providing statutory protection

consonant with that of the constitutional

guarantee. Mobile, 446 U.S. at 60, 100

S.Ct. at 1496. Therefore, the reasoning

utilized by the Court in Voter Information

to extend the protection from racial dis-

crimination provided by the fourteenth and

fifteenth amendments to the judiciary com-

pels a conclusion by this Court that the

protection from racial discrimination pro-

vided by section 2 likewise extends to state

judicial elections.

It is difficult, if not impossible, for this

Court to conceive of Congress, in an ex-

press attempt to expand the coverage of

the Voting Rights Act, to have in fact

sion that a particular portion of the plan

unlawfully diluted minority voting strength.).

See also Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735,

751, 93 S.Ct. 2321, 2330, 37 L.Ed.2d 298

(1973) ("A districting plan may create multi-

member districts perfectly acceptable under

equal population standards, but invidiously

discriminatory because they are employed 'to

minimize or cancel out the voting strength of

racial or political elements of the voting pop-

ulation.' ") (citations omitted).

amended the Act in a manner affording

minorities less protection from racial dis-

crimination than that provided by the Con-

stitution. We conclude today that section

2, as amended in 1982, provides protection

commensurate with the fourteenth and fif-

teenth amendments; therefore, in accord-

ance with this Court's decision in Voter

Information, section 2 necessarily em-

braces judicial elections within its scope.

Any other construction of section 2 would

be wholly inconsistent with the plain lan-

guage of the Act and the express purpose

which Congress sought to attain in amend-

ing section 2; that is, to expand the protec-

tion of the Act.

B. The Legislative History of Section 2

Our conclusion today finds further sup-

port in the legislative history of the 1982

amendments to section 2. An overriding

principle which guides any analysis of the

legislative history behind the Voting Rights

Act is that the Act must be interpreted in a

broad and comprehensive manner in ac-

cordance with congressional intent to com-

bat racial discrimination of any kind in all

voting practices and procedures. Thus, in

the absence of any legislative history war-

ranting a conclusion that section 2 does not

apply to state judicial elections, the only

acceptable interpretation of the Act is that

such elections are so covered. See Shef-

field, 435 U.S. 110, 98 S.Ct. 965.3

As previously noted, Congress amended

section 2 in direct response to the Supreme

Court's decision in Mobile v. Bolden,

3. In She I ield, the Supreme Court declined to

adopt a narrowing construction of § 5 and

the preclearance requirements of the Act

whereby § 5 would cover only counties and

political units that conduct voter registration.

"[I]n view of the structure of the Act, it

would be unthinkable to adopt the District

The Senate Report states that amended

[section] 2 was designed to restore the

"results test"—the legal standard that

governed voting discrimination cases pri-

or to our decision in Mobile v. Bolden.

.... Under the "results test," plaintiffs

are not required to demonstrate that the

challenged electoral law or structure was

designed or maintained for a discrimina-

tory purpose.

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 106

S.Ct. 2752, 2763 n. 8, 92 L.Ed.2d 25 (1986)

(citations omitted). In amending section 2,

Congress preserved the operative language

of subsection (a) defining the coverage of

the Act and merely added subsection (b) to

adopt the "results test" for proving a viola-

tion of section 2. In fact, the language

added by Congress in subsection (b)—"to

participate in the political process and to

elect representatives of their choice"—is

derived almost verbatim from the Supreme

Court's standard governing claims of vote

dilution on the basis of race set forth in

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 93 S.Ct.

2332, 37 L.Ed.2d 314 (1973), prior to Mobile

v. Bolden. See S.Rep.No. 417, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. 27, reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code

Cong. & Admin. News 177, 205 (Congress'

stated purpose in adding subsection (b) was

to "embod[y] the test laid down by the

Supreme Court in White."). In White, the

Court stated "[t]he plaintiffs' burden is to

produce evidence ... that [the minority

groups'] members had less opportunity

than did other residents in the district to

participate in the political processes and to

Court's construction unless there were per-

suasive evidence either that § 5 was intended

to apply only to changes affecting the regis-

tration process or that Congress clearly man-

ifested an intention to restrict § 5 cover-

age...." 435 U.S. at 122, 98 S.Ct. at 974.

2307 CHISOM v. EDWARDS

elect legislators of their choice." Id. at

766, 93 S.Ct. at 2339.4

Further, contrary to the statement in the

district court's opinion that the legislative

history of the 1982 amendments does not

address the issue of section 2 applying to

the judiciary, Senator Orrin Hatch, in com-

ments contained in the Senate Report, stat-

ed that the term "'political subdivision'

encompasses all governmental units, in-

cluding city and county councils, school

boards, judicial districts, utility districts,

as well as state legislatures." S.Rep. 417

at 151, 1982 U.S.Code Cong. & Admin.

News 323 (emphasis added). While the

above statement by Senator Hatch is not a

definitive description of the scope of the

Act, we believe the statement provides per-

suasive evidence of congressional under-

standing and belief that section 2 applies to

the judiciary, especially since the Report is

silent as to any dissent by senators from

Senator Hatch's description.

Additionally, the Senate and House hear-

ings on the various bills regarding the ex-

tension of the Voting Rights Act in 1982

are replete with references to the election

of judicial officials under the Act. The

references primarily occur in the context of

statistics presented to Congress indicating

advances or setbacks of minorities under

the Act. The statistics chart the election of

minorities to various elected positions, in-

cluding judges. See Extension of the Vot-

ing Rights Act: Hearings on H.R. 1407,

H.R. 1731, H.R. 2942, and H.R. 3112, H.R.

3198, H.R. 3473 and H.R. 3498 Before the

4. It might be argued that since the Supreme

Court used the term "legislators" and Con-

gress chose "representatives," Congress there-

by rejected language limiting the coverage of

§ 2 to legislators. The better analysis is that

Congress did not use the term "representa-

tives" with a specific intent to limit the sec-

tion's application to any elected officials.

Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Comm. on the Judi-

ciary, 97th Cong.lst sess. 38, 193, 239, 280,

503, 574, 804, 937, 1182, 1188, 1515, 1528,

1535, 1745, 1839, 2647 (1981); Voting

Rights Act: Hearings on S. 53, S. 176'1, S.

1975, S. 1992, and H.R. 3112 Before the

Subcomm. on the constitution of the

Senate Comm. on the Judiciary, 97th

Cong.2d Sess. 669, 748, 788-89 (1982).

Once again, the legislative history does not

reveal any dissent from the proposition

that such statistics were properly con-

sidered by Congress in amending the Act.

Finally, throughout the Senate Report on

the 1982 amendments to section 2, Con-

gress uses the terms "officials," "candi-

dates," and "representatives" interchange-

ably when explaining the meaning and pur-

pose of the Act. This lack of any consist-

ent use of the term "representatives" indi-

cates that Congress did not intentionally

choose that term in an effort to exclude

certain types of elected officials from the

coverage of the Act.

In contrast to the examples of legislative

history which plaintiffs cite in support of

their position that section 2 applies to state

judicial elections, the State offers no con-

vincing evidence in the legislative history

contrary to the plaintiff's interpretation of

the Act. Instead, the State relies primarily

on the plain meaning of the word "repre-

sentative" to assert that judges are exempt

from the Act. The State's position is un-

tenable.' Judges, while not "representa-

Had Congress wished to do so, it could have

easily promulgated express language to effec-

tuate that intent.

5. The State asserts that the Dole compromise

prohibiting proportional representation evi-

dences congressional intent that § 2 only ap-

ply to legislative officials. Proportional rep-

resentation, the State continues, is relevant

CHISOM v. EDWARDS

tives" in the traditional sense, do indeed

reflect the sentiment of the majority of the

people as to the individuals they choose to

entrust with the responsibility of adminis-

tering the law. As the district court held

in Martin v. Allain:

[i]udges do not "represent" those who

elect them in the same context as legisla-

tors represent their constituents. The

use of the word "representatives" in Sec-

tion 2 is not restricted to legislative rep-

resentatives but denotes anyone selected

or chosen by popular election from

among a field of candidates to fill an

office, including judges.

658 F.Supp. at 1200.

C. Section 5 and Section 2

The plaintiffs further support their posi-

tion that judicial elections are covered by

section 2 by citing to the recent case of

Haith v. Martin, 618 F.Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C.

1985), affd, - U.S. -, 106 S.Ct. 3268,

91 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986), wherein the district

court held that judicial elections are cover-

ed by section 5 and the preclearance re-

quirements of the Act. In Haith, the de-

fendant state officials sought to exempt

the election of superior court judges in

North Carolina from the preclearance re-

quirements of section 5 by relying on the

cases holding that the one person, one vote

principle does not apply to the judicial

branch of government. In an analysis

strikingly similar to that employed by the

to the legislature; therefore, Congress in-

tended § 2 to apply only to the election of

legislators. However, what belies the State's

argument is that proportional representation

may occur in any election wherein the peo-

ple elect individuals to comprise a group.

For instance, Louisiana elects seven Justices

to comprise the Supreme Court. Certainly,

the prohibition on proportional representa-

tion in § 2(b) applies in such a situation to

2308

Court in Voter Information, the district

court in Haith rejected the defendants' ar-

guments as misplaced due to the fact that

the plaintiff's claim was one based on dis-

crimination, not malapportionment. The

Haith court stated "[a]s can be seen, the

Act applies to all voting without any limita-

tion as to who, or what, is the object of the

vote." 618 F.Supp. at 413. See also Kirk-

sey v. Allain, 635 F.Supp. 347, 349 (S.D.

Miss.1986) ("Given the expansive interpre-

tation of the Voting Rights Act and § 5,

this Court is compelled to agree with the

pronouncement in Haith v. Martin" that

section 5 applies to the judiciary.).

In the instant case, the State argues that

the Supreme Court's affirmance of Haith

does not compel a conclusion that section 2

applies to judicial elections as section 5

involves the mechanics of voting, while sec-

tion 2 involves the fundamental right to

vote for those who govern. We reject this

asserted distinction. If, for instance, Loui-

siana were to enact an election statute pro-

viding that no blacks would be able to vote

in elections for Louisiana Supreme Court

Justices, it is undisputed, after Haith, that

such a statute would be invalidated under

the preclearance requirements of section 5.

To hold, as the State asserts, that such an

egregious statute would not be subject to

the requirements of section 2 as well would

lead to the incongruous result that, while

Louisiana could not adopt such a statute in

1988, if that statute were in effect prior to

prevent a legal requirement that the number

of blacks on the Louisiana Supreme Court

correspond to the percentage of blacks in the

Louisiana population. Moreover, the State

conceded at oral argument that executive

officials could be covered by § 2, underlying

their assertion that congressional fear of pro-

portional representation evidenced intent

that § 2 only apply to the legislature.

2309 CHISOM v. EDWARDS CHISOM v. EDWARDS 2310

1982, minorities could only challenge the

statute under the Constitution and not the

Voting Rights Act. Such a result would be

totally inconsistent with the broad remedial

purpose of the Act. Moreover, section 5

and section 2, virtually companion sections,

operate in tandem to prohibit discriminato-

ry practices in voting, whether those prac-

tices originate in the past, present, or fu-

ture. Section 5 contains virtually identical

language defining its scope to that of sec-

tion 2—"any voting qualification or prereq-

uisite to voting, or standard, practice, or

procedure with respect to voting...."

Therefore, statutory construction, consist-

ency, and practicality point inexorably to

the conclusion that if section 5 applies to

the judiciary, section 2 must also apply to

the judiciary. See Painpanga Mills v.

Trinidad, 279 U.S. 211, 217-218, 49 S.Ct.

308, 310, 73 L.Ed. 665 (1929).

D. The Attorney General's Interpreta-

tion

In United States v. Sheffield Board of

Commissioners, 435 U.S. at 131, 98 S.Ct.

at 979, the Supreme Court concluded that

the contemporaneous construction of the

Act by the Attorney General is persuasive

evidence of the original congressional

understanding of the Act, "especially in

light of the extensive role the Attorney

General played in drafting the statute and

explaining its operation to Congress."

Since its inception, the Attorney General

has consistently supported an expansive,

not restrictive, construction of the Act.

Testifying at congressional hearings prior

to the passage of the Act in 1965, the

Attorney General stated that "every elec-

tion in which registered voters are permit-

ted to vote would be covered" by the Act.

Voting Rights: Hearing Before Subcomin.

No. 5 of the House Judiciary Comm., 89th

Cong. 1st Sess. (1965), at 21. See also

Allen, 393 U.S. at 566-67, 89 S.Ct. at 832-

33. Continuing the trend of broadly inter-

preting the Act to further its remedial pur-

pose, the Attorney General has filed an

amicus curiae brief in the instant case in

which he maintains that the "plain meaning

of [the language in section 2] reaches all

elections, including judicial elections" and

that the pre-existing coverage of section 2

was not limited by the 1982 congressional

amendments. This construction of the Act

by the Attorney General further bolsters

our holding today that section 2 does apply

to state judicial elections.

E. Plaintiffs' Constitutional Claims

Plaintiffs also appeal the district court's

dismissal of their constitutional claims for

failure to plead specific discriminatory in-

tent. In their complaint, plaintiffs allege,

in pertinent part:

The defendant's actions are in violation

of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amend-

ments to the United States Constitution

and 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 in that the

purposes and effect of their actions is to

dilute, minimize, and cancel the voting

strength of the plaintiffs.

[2, 3] In the instant case, the district

court was correct in concluding that dis-

criminatory purpose is a prerequisite to

recovery under the fourteenth and fif-

teenth amendments. See Washington v.

Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 239-241, 96 S.Ct. 2040,

2047-48, 48 L.Ed.2d 597 (1976). However,

the district court erred in finding that

plaintiffs' complaint did not establish a the-

ory of "discriminatory intent." In Voter

Information, this Court held that if "plain-

tiffs can prove that the purpose and opera-

tive effect of such purpose" of the chal-

lenged electoral practices is to dilute minor-

ity voting strength, the plaintiffs are enti-

tled to some form of relief. Voter Infor-

mation, 612 F.2d at 212. When compared

with the complaint in Voter Information,

the plaintiffs' complaint in the instant case

is sufficient to raise a claim of racial dis-

crimination under the fourteenth and fif-

teenth amendments.'

III. CONCLUSION

Where racial discrimination exists, it is

not confined to elections for legislative and

executive officials; in such instance, it ex-

tends throughout the entire electoral spec-

trum. Minorities may not be prevented

from using section 2 in their efforts to

6. In Voter Information, the plaintiffs' com-

plaint alleged,

25. The sole purpose of the present at-

large system of election of City Judge is to

ensure that the white majority will contin-

ue to elect all white persons for the office

of City Judge.

26. The present at-large system was in-

stituted when "Division B" was created as

a reaction to increasing black voter regis-

combat racial discrimination in the election

of state judges; a contrary result would

prohibit minorities from achieving an effec-

tive voice in choosing those individuals soci-

ety elects to administer and interpret the

law. The right to vote, the right to an

effective voice in our society, cannot be

impaired on the basis of race in any in-

stance wherein the will of the majority is

expressed by popular vote.

For the reasons set forth above, we re-

verse the judgment of the district court and

remand for proceedings not inconsistent

with this opinion.

REVERSED AND REMANDED.

tration and for the express purpose of di-

luting and minimizing the effect of the

increased black vote.

27. In Baton Rouge, there is a continu-

ing history of "bloc voting" under which

when a black candidate opposes a white

candidate, the white majority consistently

casts its votes for the white candidate, irre-

spective of relative qualifications.

612 F.2d at 211.

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts—West Publishing Company, Saint Paul, Minn.