Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Wilson Brief of Defendants-Appellants in Opposition to Motion of Appellee to Dismiss or Affirm

Public Court Documents

November 29, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Wilson Brief of Defendants-Appellants in Opposition to Motion of Appellee to Dismiss or Affirm, 1950. 2cf643e0-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/49eb6cb5-74a9-479f-9da7-018174e1a19a/board-of-supervisors-of-louisiana-state-university-agricultural-mechanical-college-v-wilson-brief-of-defendants-appellants-in-opposition-to-motion-of-appellee-to-dismiss-or-affirm. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

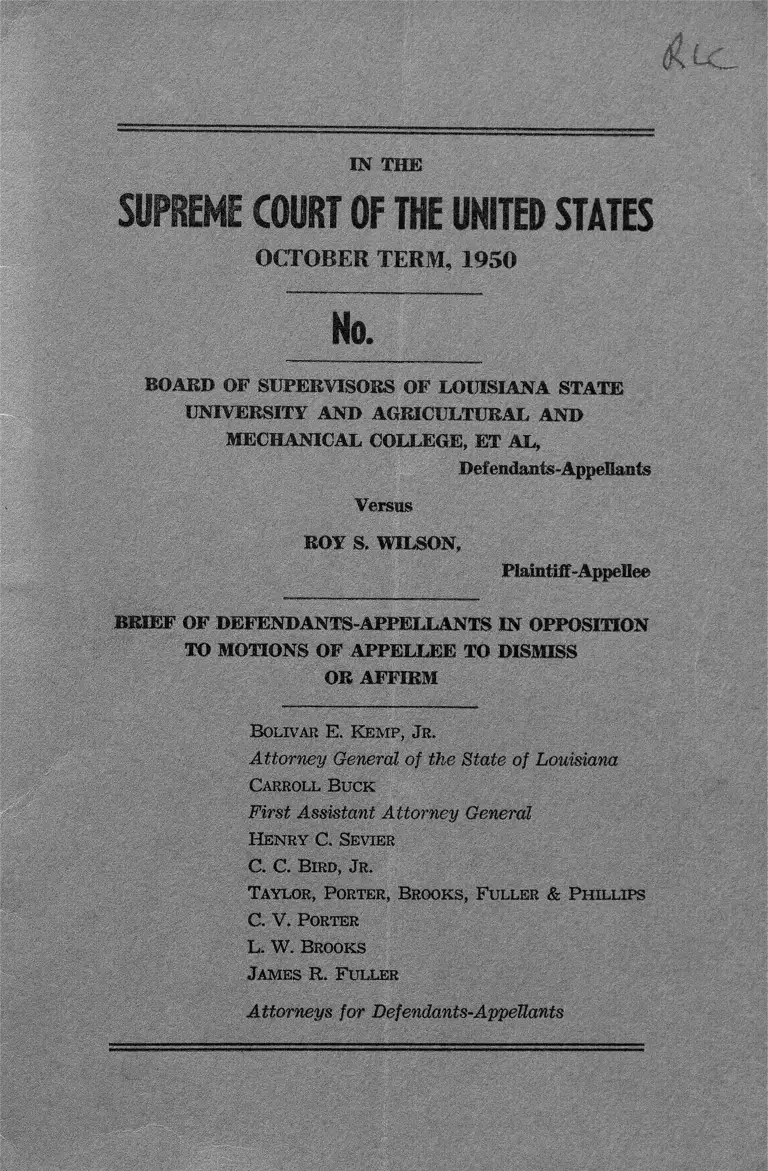

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1950

No.

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF LOUISIANA STATE

UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND

MECHANICAL COLLEGE, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellants

Versos

ROY S. WILSON,

Plaintiff-Appellee

BRIEF OF DEPENDANTS-APPELLANTS IN OPPOSITION

TO MOTIONS OF APPELLEE TO DISMISS

OR AFFIRM

Bolivar E. Kem p , Jr.

Attorney General of the State of Louisiana

Carroll Buck

First Assistant Attorney General

Henry C. Sevier

C. C. Bird, Jr.

Taylor, Porter, Brooks, Fuller & Phillips

C. V. Porter

L. W. Brooks

James R. F uller

Attorneys for Defendants-Appellants

1.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Page

Borges v. Loftis, 87 Fed. 2d 734, 301 U.S. 687, 57 S. Ct.

789, 81 L. Ed. 1344, 301 U.S. 714, 57 S. Ct. 928, 81

L. Ed. 1366 ......................................................................... 2

McLaurin v. OMahoma, 94 L. Ed. 787 ................................. 4

Phillips v. United States, 312 U.S. 246, 61 S. Ct. 480, 85

L. Ed. 800 .......................................................................... 2

Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Company, 312

U.S. 496, 61 S. Ct. 643, 85 L. Ed. 971 ......................... 2

Sweatt v. Painter, 94 L. Ed. 783 ............................................ 4

STATUTES

United States Code, Title 8, Section 4 3 .............................. 2

United States Code, Title 28, Section 1343 ........................ 2

United States Code, Title 28, Section 2281.......................... 2

United States Code, Title 28, Section 1253 5

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1950

No.

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF LOUISIANA STATE

UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND

MECHANICAL COLLEGE, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellants

Versus

ROY S. WILSON,

Plaintiff-Appellee

BRIEF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS IN OPPOSITION

TO MOTIONS OF APPELLEE TO DISMISS

OR AFFIRM

May It Please the Court:

The Appellee filed herein motions to dismiss or affirm

pursuant to Paragraph 3 of Rule 12 of the Rules of the

Supreme Court in response to the jurisdictional statement

filed by appellants.

The complaint, praying for the issuance of a preliminary

injunction, was filed in the United States District Court,

Eastern District of Louisiana, Baton Rouge Division, and a

2

specially constituted District Court of the United States was

convoked under the authority of Title 28, United States Code,

Section 1343; Title 8, United States Code, Section 43; and

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281.

The order attacked was a resolution adopted by Board

of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and Agricul

tural and Mechanical College, a public corporation, organized

and existing under the laws of the State of Louisiana, and

particularly the Constitution of Louisiana of 1921, Article

XII, Section 7, and Louisiana Revised Statutes of 1950, Title

17, Section 1451, et seq., which said resolution reads as

follows:

“BE IT RESOLVED that pursuant to the laws of Loui

siana and the policies of this Board the administrative

officers are hereby directed to deny admission to the

following applicants: Nephus Jefferson, Dan Columbus

Simon, Willie Cleveland Patterson, Charles Edward

Coney, Joseph H. Miller, Jr., Roy Samuel Wilson, Lloyd

E. Milburn, Lawrence Alvin Smith, Jr., James Lee Per

kins, Edison George Hogan, Harry A. Wilson, Anderson

Williams.’’

Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and

Agricultural and Mechanical College objected to the juris

diction of the specially constituted District Court of the

United States on the authority of the following, among other,

cases, to-wit: Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman

Company, 312 U.S. 496, 61 S. Ct. 643, 85 L. Ed. 971; Phillips

v. United States, 312 U.S. 246, 61 S. Ct. 480, 85 L. Ed. 800;

and Borges v. Loftis, 87 Fed. 2d 734, 301 U. S. 687, 57 S. Ct.

789, 81 L. Ed. 1344, 301 U. S. 714, 57 S. Ct. 928, 81 L. Ed.

1366.

3

The specially constituted District Court took jurisdiction

under the statutes above mentioned in spite of the authorities

above cited, as the complainant had brought the action on

his own behalf and on behalf of other Negro citizens of the

United States residing in the State of Louisiana to be admit

ted to the Law School of Louisiana State University and

Agricultural and Mechanical College, and prayed for a pre

liminary injunction restraining the named defendants from

making any distincton on the basis of race or color in the

consideration of plaintiff or any other applicant for admis

sion to the Law School of Louisiana State University and

Agricultural and Mechanical College.

The defendants answered the complaint and defended,

in effect, on the ground that the State of Louisiana maintains

separate schools for white and colored residents, that two

Law Schools are maintained by the State of Louisiana, one

of which is located at Louisiana State University and Agri

cultural and Mechanical College and is for white students,

and the other is located at Southern University and is for

colored students, both of which offer equal facilities for a

legal education and admission to the bar of the State of Loui

siana, and that, therefore, plaintiff and all others similarly

situated are required under the law to attend Southern Uni

versity Law School and are not eligible for admission to the

Law School of Louisiana State University and Agricultural

and Mechanical College.

The defendants offered the evidence that was immedi

ately available within the short time allowed before trial,

which evidence showed, among other things, that the State

of Louisiana had appropriated for the past year an amount

4

of some $2800.00 for each law student of Southern University

and some $600.00 for each law student of Louisiana State

University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, that the

faculty, equipment and facilities of both schools are substan

tially equal and are adequate and sufficient to fully educate

and equip a student to practice law in the State of Louisiana

and that graduates of both institutions have the same rights

under the law to be admitted to the bar of the State of

Louisiana.

The specially constituted United States District Court

found for the plaintiff, but a reading of the Court’s decision

will show that it has misinterpreted the holdings of this

Court in the cases of McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 94 L. Ed. 787

and Sweatt v. Painter, 94 L. Ed. 783.

The United States District Court abused its discretion in

granting a preliminary injunction as same should not have

been issued under the facts shown by defendants. The plain

tiff had access at all times to Southern University Law

School which satisfied the requirements of the previous hold

ings of this Court.

This appeal presents several serious questions of law and

of fact that should be reviewed by this Court as the State of

Louisiana has obviously complied in every practicable manner

with the law as laid down by this Court. Appellants should

not, therefore, be denied the privilege of presenting oral

argument and written brief in support of their contentions.

The specially constituted United States District Court

having been convoked under the above cited authorities and

having rendered judgment in said case, this Honorable Court

5

has appellate jurisdiction under the authority of United States

Code, Title 28, Section 1253. The motions filed by appellee

do not question the appellate jurisdiction of this Court.

The motions of appellee to dismiss or affirm should,

therefore, for the reasons above shown, be denied or over

ruled.

And defendants shall ever so pray.

Respectfully submitted,

Bolivar E. Kem p , Jr.

Attorney General of the State of Louisiana

Carroll Buck

First Assistant Attorney General

Henry C. Sevier

C. C. B ird, Jr .

Taylor, Porter, Brooks, F uller & Phillips

C. V. Porter

L. W. Brooks

James R. Fuller

Baton Rouge, Louisiana,

November 29, 1950.

6

CERTIFICATE

I, L. W. Brooks, of counsel for defendants-appellants in

the above entitled action, hereby certify that on the 29th

day of November, 1950, I served copies of the foregoing brief

upon the attorneys for the plaintiff-appellee by depositing

same in the United States mails, postpaid, addressed to them

as follows:

A. P. Tureaud,

612 Iberville Street,

New Orleans, Louisiana.

U. Simpson Tate,

Anderson Building,

1718 Jackson Street,

Dallas 1, Texas.

Thurgqod Marshall,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, November 29, 1950.

L. W. Brooks.