Crampton v. Ohio Respondent's Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Crampton v. Ohio Respondent's Brief, 1970. 01fbbf90-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/49eeefc6-09e4-49e7-b856-2d1f5564c2fc/crampton-v-ohio-respondents-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

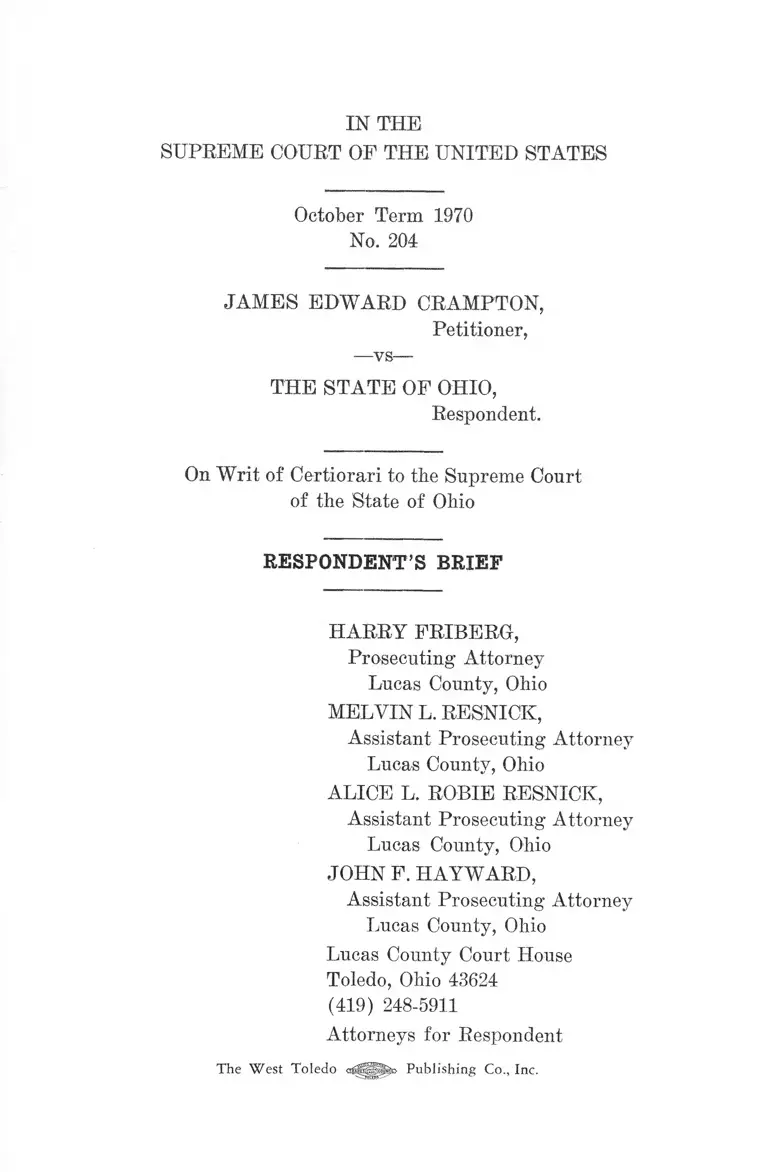

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OP THE UNITED STATES

October Term 1970

No. 204

JAMES EDWARD CRAMPTON,

Petitioner,

—vs—

THE STATE OF OHIO,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Ohio

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF

HARRY FRIBERG,

Prosecuting Attorney

Lucas County, Ohio

MELVIN L. RESNICK,

Assistant Prosecuting Attorney

Lucas County, Ohio

ALICE L. ROBIE RESNICK,

Assistant Prosecuting Attorney

Lucas County, Ohio

JOHN F. HAYWARD,

Assistant Prosecuting Attorney

Lucas County, Ohio

Lucas County Court House

Toledo, Ohio 43624

(419) 248-5911

Attorneys for Respondent

The West Toledo Publishing Co., Inc.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(i)

Page

OPINION BELOW ............ ................ ........... ....... .........1

JURISDICTION ............. .;..... .,............................................ I

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ..... ........................ ...................... 2

STATEMENT .................. ..................... ............... ......... .......... 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............................................... . 2

ARGUMENT:

I. THE OHIO STATUTE WHICH PROVIDES THAT

THE TRIER OF FACT SHALL DETERMINE

BOTH GUILT AND PUNISHMENT IN A SINGLE

VERDICT IN CASES OF MURDER IN THE FIRST

DEGREE IS NOT VIOLATIVE OF PETITIONER’S

RIGHT TO BE FREE FROM SELF-INCRIMINA

TION .............................................................. ............ . 4

A. Applicable Ohio Statutory and Case Law Concern

ing The Recommendation of Mercy By The

Trier of the Facts in a Capital Case.................. ...... 5

B. The Unitary Trial Procedure In A Capital Case

Where The Trier of The Facts Determines Both

Guilt and Punishment is Fundamentally Fair

Under the Due Process Clause and Does Not

Violate An Accused’s Fifth Amendment Protec

tion Against Self-Incrimination ................................13

II. THE DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL PROTECTION

CLAUSES OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION DO

NOT REQUIRE STATUTORY STANDARDS FOR

THE IMPOSITION OF THE DEATH PENALTY BY

THE JURY IN A CAPITAL CASE........................ ....... 29

CONCLUSION 47, 48

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Ashbrook v. Stats, 49 Ohio App. 298, 197 N.E. 214 (1935)............. 11

Application of Rodriguez, 226 F, Supp. 799 (D.N.J.1 9 6 4 ) . 23

Behrens v. United States, 312 F. 2d 223 (7th Cir.1962)..... ..... ..... . 23

Calloway v. United States, 399 F. 2d 1006

(D.C. Cir. 1968)..... ..... ............................................................. 19

Coble v. State, 31 Ohio St. 100 (1876).... ............... ................... . 10

Coleman v. United States, 334 F. 2d 558

(D.C. Cir. 1964)....... ................ .............. ..................................22

Couch v. United States, 235 F. 2d 519

(D.C. Cir. 1956).................... .............................. ..................... 24

Chatterton v. Dutton, 223 Ga. 243,154 S.E.

2d 213 (1967)........................~........ .......................................... 38

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968)..................................... 46

Frady v. United States, 348 F. 2d 84

(D.C. Cir. 1964)......... ...................................... ............ ........... 27

Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966).....................3, 37, 39

Green v. United States, 313 F. 2d 6 (1st Cir. 1963).................... 23, 24

Hill v. United States, 368 U.S. 424 (1962)................. .................. 2,20

Howell v. State, 102 Ohio St. 411,131 N.E.

706 (1921)............................................ ....................... 7,11,12, 40

In re Anderson, 69 Cal. 2d 613, 447 P. 2d 117 (1968)........................ 44

In re Ernst Petition, 294 F. 2d 556 (3rd Cir. 1961)................. ........ 38

(ii)

(hi)

Cases continued

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964)...,.,.... ..... .. ................... 19, 20

Johnson v. Commonwealth, 158 S.E. 2d. 725 (1968)....,—.................. 27

Keveny v. State, 109 Ohio St. 64, 141 N.E. 845 (1923)....................... 10

Knapp v. Thomas, 39 Ohio St. 377, 48 Am. Rep.

462 (1883)............................................................T............. ......34

Licavoli v. State, 20 O.O. 562, 34 N.E. 2d 450 (1935)... :......... ,....... 33

Massa v. State, 37 Ohio App. 532, 175 N.E. 219 (1930)................ 7

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (1970).,..... 13

Michelson v. United States, 335 U.S. 469 (1948).... .......... ............ 28

McGrady v. Cunningham, 296 F. 2d 600 (4th Cir. 1961)............. 23, 24

Myers v. Frye, 401 F. 2d 18 (7th Cir. 1968).................. 20

Oyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448 (1962)......... 36

Pope v. United States, 372 F. 2d 710 (8th Cir. 1967)...................... 27

Salsby v. State, 119 Ohio St. 314, 164 N.E. 232 (1928)... ............... 26

Segura v. Patterson, 402 F. 2d 249

(10th Cir. 1968)........ .............. ..... ...............................3,15,20,47

Shelton v. State, 102 Ohio St. 376,131 N.E. 733 (1921)... ............. 11,12

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942)..................... . 3, 21, 33, 35

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605 (1967).................................... ... 21

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554 (1967)..................... 2, 3,14,17,19, 20,

26,28,38,39,45

Cases eon tinned

Snyder v. Massachusetts, 291 U.S. 97 (1934)..... .... 27

State v. Ausberry, 83 Ohio App. 514, 82 N.E. 2d

751 (1947)........................... ......... .................. .....................................................................................26

State v. Caldwell, 135 Ohio St. 424, 21 N.E.

2d 343 (1939).......... ........... .................. ..... .................. . .4,12, 40

State v. Chapman, 111 Ohio App. 441,168 N.E.

2d 14 (1959).... ........................... ................ ..... ............. ......... 9-10

State v. Cocco, 73 Ohio App. 182, 55 N.E. 2d

430 (1943)............................ ........ ........................... .............. . 9

State v. Crafton, 15 Ohio App. 2d 160,

239 N.E. 2d 571 (1968)......................................................... ..... 9

State v. Crampton, 18 Ohio St. 182,

248 N.E. 2d 614 (1969).......................................... ........ . 11, 38

State v. Ellis, 98 Ohio St. 390,120 N.E.

2d 218 (1918).............................................................................11

State v. Frohner, 150 Ohio St. 53,

80 N.E. 2d 868 (1948)....................... ....................... ............. ..... 13

State v. Hector, 19 Ohio St. 2d 167, 249 N.E.

2d 912 (1969)........................ ...... ............. .............................. 10

State v. Hickman, 102 Ohio App. 78,141 N.E.

2d 202 (1956).............................................. .............................. 9

State v. Lucas, 93 Ohio App. 281, 109 N.E. 39 (1952)....................... 13

State v. Moore, 149 Ohio St. 226, 78 N.E.

2d 365 (1948).................. .......................... ,........ ..................... 9

State v. Mount, 30 N.J. 195, 152 A. 2d 343 (1959).......... ............ 27

Civ)

Oases continued . .. ,. .......... >

State v. Murdock, 172 Ohio St. 221,174 N.E.

2d 543 (1961)... ........ *££............. ............................. .......... . 10

State v. Strong, 119 Ohio App. 31,196 N.E.-

$ 2d 801 (1963)....................... .................... ..... ....... 9

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958)........,.... .... .............. . 45

United States v. Allegrucci, 299 F. 2d 811

(3rd Cir. 1962)...... ....... ..................... ............................. ....................................... 23

United States v. Behrens, 375 U.S. 162 (1963)...... ............. ........... 23

United States, ex rel Darrah v. Brierly, 290

F. Supp. 960 (E.DJPa. 1968)......................................23

United States v. Curry, 358 F. 2d 904

(2nd Cir. 1966)...................................... ........ ................ . 27

United States ex rel Elksnis v. Gilligan, 256

F. Supp. 244 (S.D.N.Y. 1966)....... ................... ..... ...... . 23

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1968)........... ..................... 19

United States v. Johnson, 315 F. 2d 714

(2nd Cir. 1963)................................................ ........-............... 23

United States ex rel Thompson v. Price, 258

F. 2d 918 3rd Cir. (1958)...................... .................................... 27

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970)............... 3, 4,18,19, 38, 45, 46

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949)............................... 2,20, 21

Winston v. United States, 172 U.S. 510 (1899)................................ 39

Witherspoon v. United States, 391 U.S. 510 (1968)............4, 7, 38, 44,

45, 46, 47

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886)....,.,..... . 21, 35, 38

(vi)

Statutes:

Alaska Stat., §11.15.010; §11.15.020...............................................

Conn. Gen. Stat., §53-10......................................................................

Ga. Code Ann., §26-1101................... ....... i. ........... ........

Ga. Laws, No. 1333 (1970)..................................... ....... ..... .

Iowa Code Ann., §690.2..................................................................

Maine Rev. Stat. Ann., title 17, §2651....... ................ ...................

Mich. Comp. Laws, §750.316.................... i ............. ...............

Minn. Stat. Ann., §609.185............. ;... ............ ........................... .

N.Y. Penal Law's, §1253.0 and §125.35............................................

Ohio Constitution, Article III, Section 11....... ................................

93 Ohio Laws 223............................................ ...... ........ .......!.......

Ohio Revised Code, §2901.01..... ........ .............................. 6, 30, 31,

Ohio Revised Code, §2901.02.........................................................

Ohio Revised Code, §2901.03............... ................................. .........

Ohio Revised Code, §2901.04........ ........... ........ ..... ..... ......... ..........

Ohio Revised Code, §2901.27................... .......................................

Ohio Revised Code, §2901.28..........................................................

Ohio Revised Code, §2945.06.................................... ....... .

45

42

42

42

45

45

45

45

42

33

6

42

30

30

30

30

30

5

(vii)

Statutes continued

Ohio Revised Code, §2945.57................................... ....... ••••■•.....••••••• 8

Ohio Revised Code, §2945.59— ........ ..........................................26

Ohio Revised Code, §2947.05............................ .............................. 24

Ohio Revised Code, §2947.06............................•••••..........................25

Ohio Revised Code, §2951.02................................................ ........ . 25

Ohio Revised Code, §2965.13.......................................................... 34

Ohio Revised Code, §2965.14.......................................................... 34

Oregon Rev. Stat, §163.010....................... ............ ....................... 45

Texas Code Crim. P. Ann., Art. 37.07 (2) (b>........ ................... . 42

West Va. Code, §61-2-2................................. ................................45

Wisconsin Stat. Ann., §940.01............. ...... ............................. . 45

Other Authorities ■ ,

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code........ .............. 41,: 42, 43

Bedau, Death Penalty in America, 27 (rev., ed., 1967).................. 30

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed..................................................... 31

Comment, The Death Penalty Cases, 56 Cal. L. Rev.

1268 (1968).............................................. 4,44

Elman, Of Law and Men, (1956).......... .......... .............................. 18

Kalvin & Zeisel, The American Jury (1966)................ ................. 17

State of Ohio, Commissioner of Corrections (1970)....................... 34

United States Supreme Court Rules................................................17

Webster’s New Twentieth Century Unabridged

Dictionary.................................. .............................................31

(viii)

1

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term 1970

No. 204

JAMES EDWARD CRAMPTQN,

Petitioner,

—vs—

THE STATE OF OHIO,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of Ohio

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Ohio (A. 83-88) is

reported at 18 Ohio St. 2d 182; 248 N. E. 2d 614.

JURISDICTION

On June 11, 1969, judgment was entei'ed by the Supreme

Court of Ohio (A. 82). On July 31, 1969, a petition for

Writ of Certiorari was filed and on June 1, 1970, it was

granted (A. 89), The jurisdiction of this Court rests upon

28 U.S. Code, Section 1257 (3).

2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the Ohio statute which provides that the

trier of fact shall determine both guilt and punishment in a

single verdict in cases of murder in the first degree violates

Petitioner’s right to be free from self-incrimination.

2. Whether the Ohio statute which provides that the trier

of fact may grant or withhold a recommendation of mercy

in cases of murder in the first degree, and which provides

no standards or criteria to assist the trier of fact in making

such determination, violates the Petitioner’s right to Due

Process and Equal Protection of the law.

STATEMENT

The Brief of Amicus Curiae United States contains an

adequate statement of facts pertaining to the Crampton

case.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

There is no constitutional requirement for a split-verdict

or ‘ bifurcated trial’ where the trier of the fact determines

both guilt and punishment [Spencer v. Texas, 385 U. S. 554

(1967)]. The petitioner was not faced with a collision of

constitutional rights in the trial of his case because he

lias ho specific statutory or constitutional right to offer

evidence of allocution prior to a verdict which determines

guilt and punishment [Hill v. U. S:, '368 U. S. 424 (1962);

Williams v. N. Y., 337 U. S. 241 (1949)]. The petitioner’s

Fourteenth Amendment right to be heard in the case at bar

was unfettered. By his. own choice, and for reasons best

known to himself, petitioner declined to take the witness

stand in his own defense. Instead, he presented his defense

of insanity, diminished responsibility and mitigation

through other witnesses. That decision was a free choice

which petitioner made in his own interest and not as a

result o f pressures imposed by the State [ Williams 'v.

Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970); Sequra v. Patterson, 402 F. 2d

249 (1968)]. Petitioner’s claim of unfairness is not: sup

ported by the record in that the jury had all the relevant

evidence in this ease and ' the mere fact that impeaching

evidence may have been introduced had he taken the stand

would not, of itself, be violative of Due Process, [Spencer

v. Teims, 385 U. S. 554 at 565 (1967) ].

3

II

An analysis of the plain meaning of the Ohio statute

(§2901.01 Ohio Revised Code) makes clear that the intent

of the Ohio Legislature was not to authorize arbitrary and

capricious executions, but to attempt to individualize pun

ishment.

The attack on jury sentencing based on absence of stand

ards undermines all discretionary punishment procedures,

up to and including the power of executive clemency, be

cause Due Process requirements apply to all penological

systems. [Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942)], and

[Oiaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966)], are no au

thority for petitioner’s argument, as this Court has fre

quently indicated that the concept of Due Process is not so

narrow as to exclude discretionary jury sentencing [With

4

erspoon v. Illinois, 391 U. S. 510 (1968), Williams v. Flor

ida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970)].

Ohio courts have restricted penalty juries to a con

sideration of the evidence in the case deciding whether to

recommend or withhold mercy [State v. Caldwell, 135 Ohio

St. 424, 21 N.E. 2d 343 (1939)], a “ standard” which can

he readily evaluated by applicable Due Process criteria,

unlike the proposed standards of the Model Penal Code.

Even avowed opponents of capital punishment contend

that the imposition of standards is not the solution to

the problem [56 Cal. Law. Rev. 1268, 1270 (1968) ]. Those

who oppose capital punishment should pursue its elimina

tion in the legislative arena, where some success has already

been achieved.

There is a fundamental inconsistency in an approach

which simultaneously assumes “ irrational, arbitrary and

capricious” juries and “ enlightened public opinion” which

no longer tolerates the imposition of the death penalty.

Petitioner therefore fails to show either Due Process or

Equal Protection violations under existing Ohio practice.

ARGUMENT

I

THE OHIO STATUTE WHICH PROVIDES

THAT THE TRIER OF FACT SHALL DE

TERMINE BOTH GUILT AND PUNISH

MENT IN A SINGLE VERDICT IN CASES

OF MURDER IN THE FIRST DEGREE IS

NOT V I O L A T I V E OF PETITIONER’S

RIGHT TO BE FREE FROM SELF-INCRIM-

INATION.

5

A. Applicable Ohio Statutory and Case Law Concerning

The Recommendation of Mercy By The Trier of the Facts in

a Capital Case.

Murder in the First Degree under Ohio law is punishable

by death unless the court1 or .jury makes a recommendation

1. Ohio law provides for a waiver o f jury trial in a capital case and

should an accused plead guilty, a bench trial is had to determine the

degree o f the crime. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2945-06, provides

in part:

" . . . If the accused is charged with an offense punish

able with death, he shall he tried by a court to be composed

o f three judges, consisting of the judge presiding at the

time in the trial o f criminal cases and two other judges

to be designated by the presiding judge or chief justice of the

supreme court. Such judges or a majority of them may decide

all questions o f fact and law arising upon the trial, and

render judgment accordingly. If the accused pleads guilty

o f murder in the first degree, a court composed o f three

judges shall examine the witnesses, determine the degree

o f crime, and pronounce sentence accordingly. In rendering

judgment of conviction o f an offense punishable by death

upon plea o f guilty, or after trial by the court without the

intervention of a jury, the court may extend mercy and re

duce the punishment for such offense to life imprisonment

in like manner as upon recommendation o f mercy by a

ju r y .. .”

8:

of mercy:2 3 . The mandatory death sentence for Murder in

the First Degree in Ohio was changed in 1898 by the follow

ing legislative addition to the penalty portion of the statute:

. .unless the jury trying the accused recom

mends mercy, in which ease the punishment

■ shall be imprisonment for life.m

The brief filed by Amici contains an extensive review of

the Ohio cases pertaining to the issue of a mercy recom

mendation.4 With two exceptions,5 we concur in that review

2. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2901,01,: -

"N o person shall purposly, and either o f deliberate and

premeditated malice, or by means o f poison, or in perpetra

ting or attempting to perpetrate rape, arson, robbery, or

burglary, kill another.

Whoever violates this section is guilty o f murder in the

first degree and shall be punished by death unless the jury

trying the accused recommends mercy, in which case the

punishment shall be imprisonment for life.

Murder in the first degree is a capital crime under

Sections 9 and 10 o f Article 1, Ohio Constitution.’ ’

3. 93 Ohio Laws 223 (1898). Ohio has five other statutes conferring

capital sentencing discretion to a jury and has two non-capital criminal

statutes conferring that same power.

4. Brief o f Amici, pp. 21 to 26 and footnotes 31 through 41. Herein

after Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and the National Office for the Rights of the Indigent will be

referred to as Amici.

». It is submitted that the law of Ohio as evinced by the decisions

o f the Supreme Court o f Ohio is that the granting or withholding of

a. mercy recommendation is within the absolute discretion o f the jury,

but to be based upon the evidence in the case.

The conclusion of Amici that a jury must make an affirmative

7

finding in order to grant mercy and none to withhold mercy is merely

an assumption (See- Amici Brief, page 22, footnote 34). H ie assump

tion is based upon a superfluous statement by the writer o f the opinion

in Massa v. State, 175 N.E. 219 ( 1930) . The court, by way of obiter

stated that the death penalty was warranted in view o f the evidence in

the case; that he found nothing in the record to support a recom

mendation of mercy. The case was not on review as to the basis upon

which the jury determined the penalty’ and, as a matter of law, could not

be. (See cases cited by Amici at page 27 o f their brief) If the granting

or withholding o f mercy cannot be reviewed in Ohio, can it fairly

be said that Ohio, law, in effect, requires an affirmative evidentiary

ground to grant mercy and none to withhold it? W e submit that it

could just as well be said that withholding mercy requires an affirmative

evidentiary ground.

Amici next state (pages 22-23, footnote 35) that the State o f Ohio

excludes scrupled jurors from capital cases. Apparently the contention

is based upon the statement found in the case o f Howell v. State, 102

O.S. 411, 131 N.E. 706 ( 1921) , wherein the court cautioned that any

decision on penalty should be based on evidence or lack thereof and

not on any scruples or facts which may have come to their knowledge

while not acting as a juror. (See direct quote in Amici’s Brief, page

22-23) Ohio law in regard to exclusion of jurors in a capital case

is stated in Ohio Revised Code, Section 2945.25 (C ) :

"A person called as a juror on an indictment may be

challenged for the following causes:

(C ) In the trial o f a capital offense, that his opinions

preclude him from finding the accused guilty of an offense

punishable with death. . .”

This statute was in effect at the time o f Howell and is still in effect.

This type o f exclusion was differentiated in Witherspoon v. Illinois,

391 U.S. 510 (1968), and cannot be interpreted as excluding people

who have scruples against capital punishment.

8

and will not duplicate the matter in this brief.

Ohio law provides for the introduction of character evi

dence by a defendant.6 He may parade any number of such

witnesses to show his reputation and background. The

State may not introduce any evidence in regard to the char

acter of a defendant until and unless the defendant tries to

establish his good character.7 However, the State may in

its case in chief introduce evidence of any acts of the de

fendant which, if material, tend to show motive, intent, ab-

c. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2945.57:

"The number of witnesses who are expected to testify

upon the subject of character or reputation, for whom

subpoenas are issued, shall be designated upon the praecipe

and, except in cases, o f murder in the first and second

degree, manslaughter, rape, assault with intent to commit

rape, or selling intoxicating liquor to a person in the habit

of becoming intoxicated, shall not exceed ten upon each side,

unless a deposit of at least one per diem and mileage fee for

each o f such additional witnesses is first made with the

clerk of the court of common pleas. .

?. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2945.56:

"W hen the defendant offers evidence o f his character

or reputation, the prosecution may offer, in rebuttal thereof,

proof o f his previous conviction o f a crime involving moral

turpitude, in addition to other competent evidence.”

9

senee of mistake or accident on Ms part.8 The latter type of

evidence must be accompanied by a limiting instruction to

the jury as to the purpose of the evidence.9 Case law in

OMo has restricted the introduction of tMs type of testi

mony in respect to the time, locality and character of the

act and, in addition, the act must fall within the designation

of crimen falsi of the common law.10 The credibility of the

s. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2945.59:

. "In any criminal case in which the defendant’s motive or

intent, the absence o f mistake or accident on his part, or the

defendant’s scheme, plan, or system in doing an act is mate

rial, any acts o f the defendant which tend to show his motive

or intent, the absence of mistake or accident on his part, or

the defendant’s scheme, plan or system in doing the act in

question may be proved, whether they are contemporaneous

with or prior or subsequent thereto, notwithstanding that

such proof may show or tend to show the commission of

another crime by the defendant.”

9. State v. Crafton, 15 Ohio App. 2d 160, 239 N. E. 2d 571 (1968),

reversible error for failure o f the trial court to charge on limited

purposes o f the testimony even though no request to charge was made.

10. State v. Hickman, 102 Ohio App. 78, 141 N.E. 2d 202 (1956), the

acts must be so related to the offense charged, in character and point

o f time, as tend to show intent, motive, habit or state o f mind, pro

vided acts come within designation o f crimen falsi o f the common law ;

See also State v. Cocco, 73 Ohio App. 182, 55 N.E. 2d 430 (1943) ;

within a reasonable period o f time in the same locality.

The Ohio cases reveal that this type o f evidence is very limited.

See State v. Moore, 149 O.S. 226, 78 N.E. 2d 365 (1948), threats

by defendant against a third person prior to killing; State v. Strong,

119 Ohio App. 31, 196 N.E. 2d 801 (1963), boasts made by de

fendant to third persons o f having committed offenses o f arson and

sex deviation not admissable in murder case; State v. Chapman, 111

testimony of the defendant or of any witness may be im

peached by showing prior convictions of crime.11

Ohio App. 441, 168 N.E. 2d 14 (1959), evidence o f prior sex re

lations with victim’s sister eight years prior to crime charged not

admissible in rape and incest violation.

n . Ohio Revised Code, Section 2945.42-.

"N o person is disqualified as a witness in a criminal

prosecution by reason o f his interest in the event thereof

as a party or otherwise, or by reason o f his conviction for

crime. . .Such interest, conviction, or relationship may be

shown for the purpose o f affecting the credibility o f such

witness. . .”

This statute permits examination as to convictions of a witness for

an offense under state laws. State v. Murdock, 172 O.S. 221, 174 N.E.

2d 543 (1961). It does not include convictions under city ordi

nances. Coble v. State, 31 O.S. 100 (1876).

Petitioner at page 11 o f his brief, footnote 14, has cited the case

o f State v. Hector, 19 O.S. 2d 167, 249 N.E. 2d 912 (1969) for the

proposition that a defendant can be cross examined as to pending

indictments. The case cited does not stand for that proposition what

soever. The case involved a witness for the State where the defense

desired to show that by testifying for the State, the witness was in

hope o f leniency on his own charges. In this regard the statement

in Keveny v. State, 109 O. S. 64, 141 N. E. 845 (1923) states the

law:

"O f course you cannot impeach a witness by merely showing

an indictment, but you may affect his interest in his present

testimony. .

The rule as to showing interest by pending indictment would never

be applicable to a defendant, and we suggest that any attempt to

do so would be misconduct, grounds for mistrial, and reversible

error.

11

Counsel for petitioner has urged this Court that mitiga

tion and background evidence of the accused is totally inad

missible in a capital case in Ohio.12 We cannot agree with

such statement in view of the opinion of the Ohio Supreme

Court in this very case.13 We quote from that opinion which

appears at page 86-87 of the Appendix of this case:

“ Defendant argues that, if an accused elects

to assert his right against self-incrimination,

he can not present any evidence which would

tend to mitigate on the question of his punish

ment.

“ This is obviously mot true. Defendant can,

as he did in the instant case, present such

testimony by witnesses other than himself.

(Emphasis Ours)

Petitioner’s reliance upon Ashbrook v. State, 49 Ohio App.

298,197 N. E. 214 (1935) and State v. Ellis, 98 0 . S. 21,120

N. E. 218 (1918) is questionable, to say the least, in view of

the holdings in Shelton v State, 102 0 . S. 3/6, 131 h . E. 704

(1921) and Hoivell v. State, 102 O.S. 411, 131 N.E. 706

12. Petitioner’s Brief, page 21.

13. State o f Ohio v. James Crampton, 18 O.S. 2d 182, 248 N.E. 2d 614

(1969).

12

(1921).14 Further, in State v. Caldwell, 135 0. S. 424 at 428,

21 N. E. 2d 343 (1939) cited by petitioner at page 21, foot

note 24, of his brief, it should be specifically noted that the

court’s, reason for finding no prejudicial error in not giving

the charge requested relating to the jury’s consideration of

sociological matters and environment which they may find

from the evidence, was that the requested instruction was

substantially identical to the answers the Court gave the

jury. In addition, the mere instruction presupposes that

sociological and environmental matters were in evidence

in the case. At page 428 of the opinion, the Court stated:

“ Clearly, the question was not directed to

the evidence of the environment of the defend

ant as contained in the record.”

l i . Shelton v. State, 102 O.S. 376, 131 N.E. 733, (1921)

"Syl. 1. It is the privilege of an accused upon trial to

argue to the jury in person or by counsel every controlling

fact which the evidence tends to support, and every reason

able inference therefrom touching the question of his guilt

or innocence, or which may tend to mitigate or lessen the

penalty, where the jury are empowered to fix such penalty.

"Syl. 2 . Upon trial, under an indictment for murder in the

first degree, a refusal to permit the accused in person or by

counsel to argue to the jury the desirability, advisability or

wisdom of recommending mercy, is a denial of the right of

the accused to 'defend in person and with counsel’ under

Section 10, Article I o f the Constitution o f the State o f

Ohio.”

Howell v. State, 102 O. S. 411, 131 N. E. 706, ( 1921)

"Syl. 4. In such a case, it is not error for the trial court

to permit counsel for the state to argue that a recommen

dation for mercy should be withheld.”

13

See also State v FroJmer, 150 0. S. 53, 95, 80 N. E. 2d 868

(1948), wherein the appellant’s entire case was pointed to

ward an extension of mercy.15 ............

B. The Unitary Trial Procedure In A Capital Case Where

The Trier of The Facts Determines Both Guilt and Punish

ment is Fundamentally Fair Under the Due Process Clause

And Does Not Violate An Accused’s Fifth Amendment Pro

tection Against Self-Incrimination.

The attack by the petitioner and amici16, on the unitary

trial procedure has been on two fronts: one, that the pro

cedure is fundamentally unfair17 in that (a) if an accused

takes the stand, evidence may be presented which is prej

udicial to the guilt issue, and (b) if an accused does not

is. State v. Frohner, 150 O. S. 53, 80 N. E. 2d 868 (1948) wherein the

court also stated at page 117:

"A ll that was sought in this case below was an extension of

mercy. In an effort to sustain such request the family life

of appellant’s parents was gone into.”

In State v. Lucas, 93 Ohio App. 281 at 288; 109 N.E. 39 (1952)

where twelve witnesses testified as to reputation and character the

court stated:

' "Undoubtedly this testimony was presented for the purpose

o f influencing the judges in favor of an extension o f mercy.”

16. Brief o f Amici, pp. 72 through 74; brief of petitioner pp. 9 through

19.

17. Amici’s brief, Appendix A, page 69- But see argument of Anthony

Amsterdam in Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (1970) in 7 Criminal

Law Reporter 4039 (5-13-70). "O n the single verdict issue, I want to

make, perfectly clear that we are not relying on any general unarticu

lated standard o f 'fairness’ . W e are relying on specific constitutional

rights.”

14

take the stand lie may be sentenced on less than all of the

relevant evidence; and two, that a capital defendant’s Fifth

Amendment protection against self-incrimination is violated

if he exercises his “ constitutional” right to allocution be

fore verdict on the guilt issue.18 It is to be noted that nei

ther petitioner nor amici maintain that the State is constitu

tionally compelled to have a bifurcated trial in a capital

case.19

This Court in Spencer v Texas, 385 U. S. 554, 567 (1967),

specifically rejected the bifurcated trial as being a constitu

tional commandment under the Fourteenth Amendemnt, and

expressed the view that such a matter was legislative and a

determination which, if made by the Court, would be an un

justifiable encroachment upon the powers o f the State.

Not being constitutionally compelled to have a bifurcated

trial, does the unitary trial unconstitutionally burden the ex

ercise of an accused’s Fifth Amendment privilege against

self-incrimination, and further, does the procedure under

which a capital case is tried in Ohio run afoul of the Due

Process requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution!

The petitioner in the instant case elected not to take the

stand and be subject to cross-examination. The record re

veals that, petitioner instead presented four witnesses, none

ls. Id. at page 76, footnote 77:

"The effect of the single verdict sentencing procedure

which he challenges is to confront a capital defendant with

the grim specter o f having to sacrifice one or another o f his

precious constitutional rights, either allocution or seif-

incrimination.”

19. Id. at page 78, footnote 79.

15

of whom testified in respect to the facts of the crime (R. 278

et seq). Guilt in this case was never seriously contested and,

consequently, the petitioner’s case was largely medical in

nature. The petitioner’s mother testified and gave the jury

the benefit of the petitioner’s childhood and general back

ground. (A, 49-59). The medical testimony, because of its

psychiatric nature, brought out the petitioner’s entire per

sonality; and because the petitioner felt inclined to intro

duce various hospital reports, his entire life history was dis

played to the jury. We can only assume that this was done

in an effort to mitigate the penalty since there was nothing

contained in the records which support a conclusion that

petitioner was not guilty by reason of insanity. Thus, all

that could be said of petitioner’s life was before the jury

without the necessity of his having had to take the stand.

Petitioner and amici urge that this type of situation ag

gravates the ‘tension’ as to his constitutional right to remain

silent and his desire to produce mitigating testimony. We

submit that defendant can introduce such evidence by other

witnesses, and that, nevertheless, the unitary trial is not by

its; nature unconstitutionally coercive.

The arguments in this regard are very well stated in

Segura v. Patterson, 402 F. 2d 249 (10th Oir., 1968), wherein

there appears:

“ One answer to this contention is that miti

gating evidence could be introduced through

other witnesses. Nevertheless, it is quite cott-

.... ceivable as indeed it was shown below, that the ,

accused may be the only available source of

material mitigating information. Therefore,

there is a strong compulsion to take the stand.

16

This compulsion does not derive from <my co

ercion of the State. Instead, it arises from the

desire of the accused to act in his own en

lightened self-interest. He is compelled to

testify only in the sense that it may be to h is .

advantage to do so. The choice is his embrac

ing no more substantial ‘chilling effects’ in a

single verdict situation than it does in any

other instance. It is always the case that in

exercising the constitutional right to remain

silent, the individual is forced to forego his op

portunity to personally appeal to the jury.

Whether such an appeal relates to the deter

mination of guilt or punishment or both, it can

not he denied that the inducement not to re

main silent and thus to forego a specific con

stitutional right does not arise from any un

necessary burden imposed by the State. We

conclude that the single-verdict procedure

does not ‘ needlessly chill the exercise of basic

constitutional rights’. (Emphasis Ours)

A defendant during a criminal trial is often faced with a

similar choice in regard to the issues of self-defense, acci

dent, duress, insanity, lesser included offenses, and alibi.

Petitioner and amici might also argue that these issues re

quire separation on the constitutional claim that a defend

ant has a Sixth Amendment right to present his defense, but

that to do so would impinge his Fifth Amendment right to

remain silent. To carry this to its extreme could in some

cases involve a four-stage trial, and we can see no reason

why such a. ruling would not be applicable to all criminal

17

trials where more than one issue may be involved.20 The ef

fect of such a procedure on the administration of criminal

justice would be devastating. It would be an affront to the

jury system and an insult to the intelligence of the people

of the United States. They are the persons who share in

the responsibility of the administration of criminal justice

by the giving of their time and energy to serve as jurors and

decide different issues under proper instructions by a

court. The court in Spencer v. Texas, supra, at 565 stated:

‘ ‘ It would be extravagant in the extreme to

take Jackson as envincing a, general distrust

on the part of this court of the abilities of

juries to approach their task responsibly

and to sort out discrete issues given to them

under proper instructions by the judge in a

criminal case, or as standing for the propo

sition that limiting instructions can never

purge the erroneous introduction of evidence

or limit evidence to its rightful purpose.”

and as noted by the Court in its footnote to this premise :

‘ ‘ Indeed the most recent scholarly study of

jury behavior does not sustain the premise

that juries are especially prone to prejudice

when prior crime evidence is admitted as to

credibility. Kalven and Zeisel, The American

Jury (1966), the study contrasts the effect of

such evidence on judges and juries, and con

cludes that ‘ Neither the one nor the other can

20 . Petitioner in the case at bar has injected an additional issue which is

beyond the limitations o f the writ granted herein. Inasmuch as the

insanity issue was not within the issues designated in the granting of

certiorari, we have declined to comment in that regard. (Rules o f the

Supreme Court 40 ( i ) (d ) ( 2 ) .

18

be said to be distinctively gullible or skeptical.’

Id. at 180.” . . . .

The late Justice .Felix Frankfurter in his report to the

Royal Commission on Capital Punishment stated:

, “ May I:say, with all respect, I do not under

stand the view that juries are not qualified to

discriminate between situations calling for

mitigated sentences.” 21

This Court has recently discussed the question of ‘ com

pelled’ incrimination in the case of Williams v. Florida, 399

U. S. 78 (1970) wherein it was stated by Justice White that.:

“ The defendant in a criminal trial is fre

quently forced to testify himself and to call

other witnesses in an effort to reduce the risk

of conviction. .. .That the defendant faces such

a dilemma demanding a choice between com

plete silence and presenting a defense has

never been thought an invasion of the privil

ege against compelled self-incrimination. ”

That case dealt with notice o f alibi, but the principle re

mains the same. Justice White’s further comment that

there is nothing in the Fifth Amendment which would en

title a defendant to await the jury’s verdict on. the State’s

case-in-chief before deciding whether or not to take the

stand is particularly applicable to the procedure requested

by petitioner and amici. There have been no added pres

sures brought to bear on the defendant, and the State has

not added to the natural consequences o f the trial. He is

simply left the choice of testifying in an effort to either

escape conviction or reduce the effect thereof, or not testi

fying because he feels he stands a better chance remaining

2L Elman, O f Law and Men (1956)

silent. The benefit is with, the defendant in that he can

make that choice with full knowledge of the possible bene

fits or detriments to him. As Justice Black stated in his dis

sent in the Williams case, supra,

“ . . .and obviously there will be times when the

trial process itself will require the defendant to

do something in order to try to avoid a con

viction.”

The petitioner and amici have particularly stressed the

case of U. 8. v. Jackson, 390 U. S. 570 (1968) as supporting

their contention that the unitary trial imposes a needless

burden which “ chills” the exercise of basic constitutional

rights. We believe the principles of the Jackson case to be

clearly distinguishable from the issues in the case at bar.

First, Jackson dealt with specific constitutional rights: the

Fifth Amendment right not to plead guilty and the Sixth

Amendment right to demand a jury trial. As will be shown

later in this brief, allocution is not a specific constitutional

right. Second, the petitioner, in the case at bar, was not

subject to a different penalty depending on his choice of a

jury or court trial or in his choice of taking the stand or

not.22 There was, therefore, no extra burden imposed by the

State. The choice was that of the petitioner, and it must be

assumed that he made the choice which he knew was most

favorable to himself. It cannot therefore be said that the

unitary trial “ needlessly encourages” the waiver of the

right to remain silent.

Petitioner next places reliance on JacJison v. Denno, 378

U. S. 368 (1964). Again, as noted in Spencer v. Texas,

22. See Calloway v. U. S., 399 F. 2d 1006 at 1009 n. 4 (C A D C ) cert,

denied 393 U.S. 987 (1968) (U S. v. Jackson distinguished) .

19

20

supra, the Court in Jackson v. Denno, supra, was dealing

with specific constitutional rights and the procedure set

forth therein was designed as a specific remedy to insure

that an involuntary confession was not, in fact, relied on by

a jury, 385 U. S. at 565. Amici’s premise that Jackson v.

Denno, supra, is not weakened by Spencer v. Texas, supra,

is erroneously based on an alleged ‘ specific constitutional

right’ to allocution.

This Court in Hill v. U. S„ 368 U. S. 424, 428, (1962), held

that allocution is not a constitutional right.23 In Williams v.

N. Y., 337 U. S. 241 (1949), this Court held that the Due

Process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment did not re

quire a judge to have hearings and give a convicted person

an opportunity to participate in those hearings when he

came to determining the sentence to be imposed. As stated

in Seqwra v. Patterson, supra,

23. Hill v. US., 368 U.S. 424, 428 ( 1962)

"The failure o f a trial court to ask a defendant represent

ed by an attorney whether he has anything to say before

sentence is imposed is not o f itself an error o f the character

or magnitude cognizable under a writ o f habeas corpus. It

is an error which is neither jurisdictional nor constitutional.

It is not a fundamental defect which inherently results

in a complete miscarriage o f justice, nor an omission incon

sistent with the rudimentary demands o f fair procedure.”

(Emphasis ours)

Although the Hill decision was based on a non-capital case, the con

stitutional question involved is the same. See Myers v. Frye, 401 F. 2d

18, 21, (7th O r. 1968), a capital case where the doctrine o f Hill was fo l

lowed.

21

“ If a judge need not allow allocution as a

constitutional right when determining the

penalty, it follows that there is likewise no-

such right to so influence a jury.”

The cases of Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 Uv S. 535 (1942)

and Specht v. Patterson, 386 U. S. 605 (1967) do not sup

port petitioner or amici’s statement that allocution is a con

stitutional right.24 The Specht case cited by petitioner and

amici adhered to the decision of Williams v. N. Ysupra.

However, the court could not. extend the Williams v. N. Y

doctrine to a Colorado habitual sex offender procedure

which did not make the commission of a specified crime the

basis for sentencing. The question, as noted by the court,

was similar to the recidivist cases where a distinct issue was

presented and naturally defendant must have a full oppor

tunity to be heard, etc. Thus, no comparison can be used by

petitioner insofar as the rationale of the Specht case is con

cerned. The petitioner in the instant case had an oppor

tunity to be heard, etc. Moreover, the petitioner was free

to place in evidence mitigating and background evidence,

which he did through his mother. Psychiatric evidence was

introduced going toward diminished responsibility and in

sanity.

The Skinner case, supra, was decided on an equal pro

tection basis and not on his opportunity to be heard. There,

as in the case of Yick Wo v. Hopkms, 118 IT. S. 356 (1886),

there was an invidious discrimination. As will be shown in

our “ Standards” argument, no invidious discrimination can

be shown in a unitary trial procedure.

Consideration of what is stated by the Court in Williams

v. N. Y., supra, 251-2:

2i. Brief of Amid, page A-71 and footnote 77 at page A-75-76.

22

. .And it is conceded that, no federal consti

tutional objection would have been possible if

the judge here had sentenced appellant to

death because appellant’s trial manner im

pressed the judge that appellant was a bad risk

for society, or if the judge had sentenced him

to death giving’ no reason at all. ” ■■■■■

implies that allocution is not a specific constitutional right.

I f a judge may isentence a, man for no reason at all, al

locution cannot he said to have constitutional status.

Under Ohio practice, no special procedure has been en

acted for allocution in a capital ease, other than by the de

fendant’s opportunity to testify or to have other witnesses

testify at the trial itself. There is nothing in Ohio compar

able to the Federal sentencing procedure under rule 32 (a)

of the Federal Code of Criminal Procedure which specifi

cally provides for the court to consider evidence in miti

gation. In view of this, the cases cited by amici and peti

tioner concerning procedural Due Process do not apply. An

example is the case of Coleman v. U.S., 334 F. 2d 558

(D. C. C:ir. 1964), where, after the District of Columbia

mandatory death penalty statute was amended to pro

vide for recommendations of life imprisonment, a statute

was enacted to establish a procedure for reduction of

sentence. As stated at page 562 in that opinion:

“ Whereas in cases charging murder in the

first degree after March 22, 1962, a jury was

authorized to recommend life imprisonment, as

to appellant’s case a ‘procedure’ was estab

lished whereby the judge was ‘to consider the

circumstances in mitigation and in aggrava

tion.” (Emphasis, Ours).

23

In snebt.a situation, as in.a split-vei'dict procedure, allo

cution has specifically been provided for by statute and

procedural Due Process would then require a fair deter

mination of the issues involved. In this sense only would

allocution as part of the sentencing process be subject to the

scrutiny of Due Process.The statement of amici at page 71,

footnote 75, that allocution is a constitutional right is not

supported by the decisions cited in that footnote. See Green

v. U.8., 313 F. 2d 6 (1st Oir. 1963); U.S. v Johnson, 315 F.

2d 714 (2nd Cir. 1963); and Behrens v. U. 8., 312 F. 2d 223

(7th Oir..1962), affirmed 375 U.S. 162 (1962). Those de

cisions w7ere based in two instances on rule 32 (a) of Federal

Rules of Criminal Procedure and in the other case on rule

43 requiring presence of defendant and counsel. In each

case, the procedure giving the opportunity for allocution

was in some way erroneously conducted. But there is

nothing in those opinions which can be interpreted as hold

ing allocution in and of itself to be a constitutional right.25

25. See U.S, ex rel Darrah v. Briefly, 290 F. Supp. 960 (1968) at 963

where it is stated:

"However, there is no constitutional right to allocution. McGrady v.

■Cunningham, 296 F. 2d 600, 96 A. L. R. 2d 1286 (4th Cir. 1961) ; Appli

cation o f Rodriquez, 226 F. Supp. 799 (D . N. J. 1964) ; United States ex

rel. Elksnis v. Gilligan, 256 F. Supp. 244 (S. D. N. Y. 1966). Although

allocution is afforded a defendant as of right in all Federal Criminal pro

ceedings, F. R. Crim. Proc. 32 (a.) ; United States v. Allegrucci, 299 F. 2d

811 (3rd Cir. 1962), the basis therefor does not rest upon constitutional

grounds. Indeed, the Supreme Court o f the United States has expressly

indicated its reluctance to base the Federal right embodied in Federal Crim

inal Rule 32 upon the Constitution.

" [1 2 } Instead, it merely observed that this right is "ancient in the law.”

United States v. Behrens, 375 U.S. 162 165, 84 S, Ct. 295, 11 L. Ed. 2d 224

Although Ohio has a. mandatory statute requiring the-court

to inquire of the defendant whether he has anything to say

before sentence is pronounced126, the practice, because of the

unreviewability of the death sentence, is a mere f ormality in

capital cases and the two non-capital cases in Ohio where *

(1963).

"See also McGrady v. Cunningham, 296 F. 2d 600 (1961). A state

court conviction o f murder in the first degree where no allocution was had.

The Court stated at page 602,

"The only two cases cited on this point are federal cases, Couch v. US.,

98 U.S. App. D. C. 292, 235 F. 2d 519, and Green v. US., 365 U.S. 301,

81 S. Ct. 653, 5 L. Ed. 2d 670. Both o f these cases arose under rule 32

(a) F. R. Cr. P., 18 U. S. C. A., which provides, insofar as material, as

follows:

'Before imposing sentence the court shall afford the de

fendant an opportunity to make a statement in his own be

half and to present any information in mitigation o f pun

ishment.’

"'There is no similar rule applicable by statute or rule o f court in Virginia

and apparently it has never been suggested before that there is any such

rule in Virginia . . .

"W e conclude therefore that there is no merit in the appellant’s con

tention on this point and we may further remark in passing that even under

the federal rule failure to grant the right o f allocution directly to the

prisoner rather than to counsel for the prisoner would not entitle the

prisoner to a new trial. The only effect would be to set aside the sen

tence and send the case back for resentencing after compliance with the

rule. See Couch v. U. S., supra, and Green v. U. S., supra. And this

is also the rule in the states that still require allocution.”

26. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2947.05:

"Before sentence is pronounced, the defendant must be

informed by the court o f the verdict o f the jury, or the find

ing o f the court, and asked whether he has anything to say

as to why judgment .should not be pronounced against him.”

25 ‘

a jury fixes the puuishmefit. It is to be noted also that the

Ohio statute is far short of Federal Buie 32 (a) which speaks

of evidence in mitigation.

In most non-capital cases, the defendant can, after being

convicted, be referred to a probation department for a j)re

sent ence investigation and report.27 28 If the court refuses a

referral to the probation department, the defendant can

still invoke Ohio Bevised Code, Section 2947.06 to hear

testimony to mitigate the sentence.®8

27. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2951.02:

"Where the defendant has pleaded guilty, or has been

found guilty and it appears to the satisfaction of the judge

or magistrate that the character o f the defendant and the

circumstances o f the case are such that he is not likely again

to engage in an offensive course o f conduct, and the public

good does not demand or require that he be immediately

sentenced, such judge or magistrate may suspend the im

position o f the sentence and place the defendant on pro

bation upon such terms as such judge or magistrate deter

mines.”

28. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2947.06:

"The trial court may hear testimony o f mitigation o f a sen

tence at the term of conviction or plea, or at the next term.

The prosecuting attorney may offer testimony on behalf o f

the state, to give the court a true understanding o f the case.

The court shall determine whether sentence ought immedi

ately to be imposed or the defendant placed on probation.

The court o f its own motion may direct the department of

probation o f the county wherein the defendant resides, or its

own regular probation officer, to make such inquiries and

reports as the court requires concerning the defendant, and

such reports shall be confidential and need not be furnished ;

to the defendant or his counsel or the prosecuting attorney

unless the court, in its discretion, so orders ,

26

In capital cases, inasmuch as the sentence of life or death

is unreviewable either by the trial court or appellate court,

the statute means nothing insofar as mitigation is con

cerned, and the only effect of error in this regard is to

send the case back for resentencing.89

We earnestly submit that the arguments advanced here in

support of bifurcation in the trial of a capital case are less

compelling than the same arguments raised concerning the

recidivist trial procedure in Spencer v. Texas, supra. In

Spencer, the defendant’s prior convictions were in evidence,

whether or not he testified. In the case at bar, however,

petitioner’s prior convictions could come to the knowledge

of the jury without his approval* 30 only in two ways: (1)

through cross-examination had he chosen to testify, and/or

(2) through evidence of his prior convictions introduced

pursuant to Section 2945.59, Ohio Revised Code.31 32 As the

record discloses, the State did not offer such evidence in

this case for the reason that the prior acts would not have

gone to the matters mentioned in the statute. Remoteness

would have been an additional limiting factor.3,2 It therefore

appears that even the dissenters in Spencer, under the facts

presented in this case, would agree that petitioner’s con

stitutional rights have not been violated.

An exhaustive review of the cases in this matter dis

closes that the split verdict procedure may, in some ways,

29. See Sals by v. State, 119 O. S. 314, 164 N. E. 232 (1928) ; Slate v.

Ausberry, 83 Ohio App. 514, 82 N. E. 2d 751 (1947)

30. It should be remembered that petitioner himself introduced his re-

cividist record by offering various hospital records.

31. See footnote 8, supra.

32. See footnote 10, supra.

be a more modern method of resolving the determination

of guilt or innocence and punishment. However, none of

the cases have held the single verdict procedure unconsti

tutional. Some of the courts have actively suggested in

their opinions that their legislatures enact statutes re

quiring bifurcated trials.3,3 Some courts have merely stated

the. proposition that this is not a judicial question but a

legislative one.* 34

W e would urge, as was suggested in Frady v. U. S., 348

F. 2d 84 (D. C. Cir. 1964); Pope v. U.S., 372 F. 2d 710, (8th

Cir. 1967); and U.S. v. Curry, 358 F. 2d 904, 914-915 (2nd

Cir. 1966) that because of the inherent problems in the

adoption of such a procedure, the question is best left with

the respective legislatures of the States. Only through com

prehensive studies of the individual procedural and sub

stantive laws of the1 respective states could such a proced

ure be put into effect without chaos.

As stated by Mr. Justice Cardozo in Snyder v. Massachu

setts, 291 TJ. S. 97, 105 (1934), and repeated often by the

court, a state rule of law

“ does not run foul of the Fourteenth Amend

ment because another method may seem to our

thinking to be fairer or wiser or to give a surer

promise of protection to the prisoner at

bar.”

The Court has additionally stated that it was not a rule-

making organ for the promulgation of state rules of crim

33. State v. Mount, 152 A. 2d 343 (1959), 30 N . J. 195 (legislation

subsequently enacted).

; U. S. ex rel, Thompson v. Trice, 258 P. 2d 918, 922 (3rd Cir. 1958)

(Legislation in Pennsylvania subsequently enacted).

34 Johnson v. Commonwealth, 158 S. E. 2d 725.

27

28

inal- procedure, ■■Spme&r -v. -Terns, .385 :\?U. S. 554, 564

(1967),

The trial in the instant case was fundamentally fair.

Neither impeachment evidence nor prior convictions of

crime were introduced by the State in the instant case. Had

the same been introduced the court under Ohio law would

have given the jury instructions concerning the limited pur

pose of such evidence. The petitioner was able to intro

duce background evidence and could have, if he so desired,

introduced character testimony. Petitioner’s and amici’s

objection to the unitary trial because of the possible infus

ion of prejudicial evidence concerning these latter issues is

effectively answered in Michelson v. U. S., 335 IT. S. 469,

485 (1948):

“ limiting instructions on this subject are no

more difficult to comprehend or apply than

those upon various other subjects.”

To say that allocution is a specific constitutional right is to

read into the Constitution what is not there. The argu

ments of petitioner and amici based on that premise must

fall.

The State of Ohio has as much, if not more, of a valid

state purpose in maintaining its unitary trial proceedings in

a capital ease as Texas had in enforcing its former reeividist

statute in a unitary trial.

The unitary trial procedure has been in use throughout

the history of our country by every state in the Union.

There has been no showing in the arguments advanced by

petitioner why Ohio law and practice should be an excep

tion to the statement in Spencer v. Texas, supra:

29

“ To say that the two-stage jury trial in. the .

English-Conneeticut style is probably the fair

est, as some commentators and courts have

suggested, and which we might well agree were

' the matter before us in a legislative or rule

making contest, is a far cry from a constitu--

tional determination that this method of hand

ling the problem is compelled by the Four

teenth Amendment.

. . .“ Two-part jury trials are rare in our juris--

prudence; they have never been compelled by

. this court as a matter of constitutional

law, or even as a matter of federal procedure.

To take such a step would be quite beyond the

pale of this court’s proper function in our Fed

eral system. It would be a wholly unjustifiable

encroachment by this Court upon the constitu

tional power of States to promulgate their own

rules of evidence to try their own state-created

crimes in their own state courts, so long as

their rules are not prohibited by any provision

of the United States Constitution, which these

rules are not. ”

THE DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL PRO

TECTION CLAUSES OF THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED

STATES CONSTITUTION DO NOT RE

QUIRE STATUTORY STANDARDS FOR

THE IMPOSITION OF THE DEATH PEN

ALTY BY THE JURY IN A CAPITAL CASE.

The development of laws relating to capital crimes in the

United States demonstrates a pattern beginning in the

Nineteenth Century and continuing to the present day which

shows increasing selectivity in imposing the death pen

30

alty.35 An analysis of tile statutes of the State of Ohio and

other states shows that the legislatures of the several states

have attempted in various ways to permit those who try the

ease, whether judge or jury, some flexibility in deciding

whether the death penalty is called for in every “ cap

ital” crime.3:6 There can be no disputing the fact that the

motivation of the legislatures has been largely humane and

that the enactments are attempts to institutionalize the in

creasing sensitivity of civilized men and women with refer

ence to the application of the death penalty.37

Petitioner and those supporting his position in this ease

argue that the practice in Ohio courts permitted under

Section 2901.01, Ohio Revised Code, amounts to killing

people at the whim of a jury. We will attempt to demon

strate that the facts argue otherwise, and that merely be

cause statistics show that juries are becoming more and

more selective in the administration of the death penalty,

this does not demonstrate that the provisions of Ohio’s

First Degree Murder statute have become meaningless

with reference to punishment.

35. See Bedau, The Death Penalty in America, 27 (revised edition 1967) .

See also Appendix B, Brief o f Amici.

36. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2901.01 (first degree murder)

Ohio Revised Code, Section 2901.02 (killing by obstructing a rail

road)

Ohio Revised Code, Section 2901.03 (killing o f a guard by a prisoner)

Ohio Revised Code, Section 2901.04 (killing a police officer)

Ohio Revised Code, Section 2901.27 (kidnapping for extortion)

Ohio Revised Code, Section 2901.28 (killing a kidnap victim)

See also Appendix B, Brief of Amici.

37V See Bedau, The Death Penalty in America, 1-8 (revised edition, 1967)

31

In effect, petitioner is employing a quantitative argument,

saying that because only a minority of persons convicted of

capital crimes are actually sentenced to death, one must

view life imprisonment as the principal punishment pre

scribed for Murder in the First Degree. As is often the case

in the interpretations of the Constitution by this Court,

we think it is important to analyze first the plain meaning

of the words in Ohio Revised Code, Section 2901.01 relating

topenalty:

“ Whoever violates this section is guilty of

murder in the first degree and shall be pun

ished by death unless the jury trying the ac

cused recommends mercy, in which case the

punishment shall be imprisonment for life.”

While by no means attempting to exalt form over substance,

we think it significant to note that the Ohio statute speaks

in terms of “ a recommendation of mercy.” * 2 3 4 *’8

3S. Black’s Law Dictionary, Ath Edition, defines "mercy” as follows:

"The discretion of a judge, within the limits o f positive

law, to remit altogether the punishment to which a con

victed person is liable, or to mitigate the severity o f his sen

tence; as when a jury recommends the prisoner to the mercy

o f the court.”

Webster’s New Twentieth Century Unabridged Dictionary, 2nd Edi

tion. defines "mercy” as:

"1. A refraining from harming or punishing offenders,

enemies, persons in one’s power, etc., kindness in excess of

what may be expected or demanded by fairness; forbearance

and compassion.

2. A disposition to forgive, pity, or be kind.

3. The power to forgive or be kind; clemency; as,

throw yourself on his mercy.

4. Kind or compassionate treatment; relief o f suffer

ing.”

32

It is respectfully submitted that it would not be hyper-

literal to point out that the definitions of “ mercy” imply

discretion. Indeed, the word itself is used in defining

mercy. In the legal sense and in the recognized universal

definitions of the word, which surely must have some sig

nificance for legislatures in the process of enacting our

laws, the word implies the power to forgive or to be kind

in excess of what may be expected or demanded by fair

ness. Petitioner here seeks to argue that the exercise of

such a power is not only unconstitutional within the mean

ing of the applicable clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, but “ irrational.”39 It is respectfully submitted that an

honeist examination of the words of the statute with atten

tion to their accepted meanings, cannot but result in the

conclusion that the exercise of the power is not irrational,

but is, rather, the exercise of forbearance and compassion,

human qualities long exalted in both the moral and legal

traditions of civilized society.

Petitioner and amici seek to establish that because it is

statistically demonstrable that- capital punishment is not

imposed in a majority of cases where defendants are con

victed of capital crimes, such disposition is the “ normal”

course of justice.40 Presumably, it makes the imposition

of capital punishment in such cases “ abnormal” , and also

“ abnormal” the State’s attempts to provide every possible

opportunity for the exercise of human ideals, including sta-

utory means by which defendants convicted of capital crimes

can be spared the death penalty.

39. Brief o f petitioner, James Edward Crampton, page 31.

40. Brief of amici, page 69-

33

We maintain, therefore, that an observation and analysis

of the statute involved cannot but result in the conclusion

that it manifests a bona fide attempt to permit juries the

exercise of human qualities which may go beyond the mere

basic requirements of justice.41

It will no doubt be argued that the absence of standards

permits the exercise of the decision-making power of the

jury in capital cases on basis other than compassion and

kindness; indeed, perhaps on the basis of prejudice, fear,

hatred, and other human qualities not so exalted. The

question then becomes: is it a violation of Due Process or

Equal Protection when punishment consists of two possible

alternatives to be selected in the discretion of the jury!

It is submitted respectfully that the answer to the last pre

ceding question is “ no” , whether the Ohio concept of

“ mercy” or the California concept of “ discretion” is relied

upon, and the remainder of the argument herein is an at

tempt to support that conclusion.

Petitioner contends that Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S.

335 (1942), means that Ohio cannot give its juries power to

draw a distinction between those capital defendants who

receive the death penalty and those who are sentenced to

life imprisonment. I f so, then how may Ohio give its

Governor the power! The Constitution of Ohio vests the

entire pardoning power in the Governor.4" The only limi

tation on such power is found in the Constitution itself.43

+i. See Brief o f amid curiae United States I (A ) 1.

42. Article III, Section II o f the Ohio Constitution.

43. See Lkavoli v. Slate, 20 O. O. 562, 568, 34 N. E. 2d 450, (1935).

No other body, whether legislative or judicial, can exercise

like power.44 The Governor may grant a reprieve, com

mutation, or pardon to any person under sentence of death

with or without notice or application from the convicted

felon.45

In Ohio, any condemned person can make application to

the Pardon and Parole Commission. Each application re

ceived is acted upon by the Commission. The Commission,

after investigating the case, makes a recommendation for

or against the granting of the reprieve, pardon, or com

mutation to the Governor.46 The Governor acts individ

ually upon each application he receives. After a capital

felon has exhausted all of his judicial appellate remedies,

he still is afforded this executive remedy. The exercise

of the power of clemency is sought by almost all convicted

felons sentenced to death in Ohio.47 If a convicted capital

44. Knapp v. Thomas, 39 O. S. 377, 48 Am. Rep. 462 (1883).

43. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2965.14.

+6. Ohio Revised Code, Section 2965.13.

47. The following table shows the ultimate disposition o f cases involving

the death penalty in Ohio. These statistics were provided by the Gover

nor’s Office, Commissioner o f Corrections, Ohio Penitentiary. From the

table, it can be seen that one-third of all the death sentences in the State

o f Ohio from 1956 up to and including July, 1970, were commuted by the

Governor.

34

Years Men Rec’d. Executed Lima State

Hospital

Commuted Death

Row

1956-60 28 12 4 12 0

1961-65 24 3 2 12 7

1966-70 39 0 0 6* 33

Total 91 15 6 30 40

^During this period from 1966 up to and including July 2, 1970, there

were only six (6 ) commutations o f sentences granted by the Governor. .

felon is denied Due Process and Equal Protection by the

jury imposing the death penalty without standards, then

the same defendant is denied Due Process and Equal Pro

tection when the Governor sees fit to grant one convicted

felon a pardon or commutation and not another. Both

would have to be declared unconstitutional if either one

were so declared. Stated otherwise, i f the Governor’s

clemency power is not violative of Due Process and Equal-

Protection guarantees, then it cannot be a violation of those

guarantees for a state to grant a trial jury the right to

recommend mercy.

Petitioner relies principally on two decisions of this

Court to support his contention that the imposition of the

death penalty within the discretion of the jury is a violation

of Due Process and Equal Protection. First is the case of

Skinner v. Oklahoma, supra. Petitioner relies on this case

as authority in support of the Equal Protection argument

because the court in that- case held that the State of Okla

homa could not sterilize thieves without sterilizing em

bezzlers. Citing the case of Yick Wo -v. Hopkins> 118 U. S.

356 (1886), the Court in Skinner said:

“ When the law lays an unequal hand on

those who have committed intrinsically the

same quality of offense and sterilizes one and

not the other, it has made as invidious a dis

crimination as if it had selected a particular

race or nationality for oppressive treat

ment.48

The law of the State of Ohio makes no such invidious dis

crimination. It simply says that the punishment for Mur

der in the First Degree shall be death, and that the jury

48. Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535, 541 (1942).

35

36

which hears the case will have the right to decide whether

the punishment in a particular case, in its discretion, should

he imprisonment for life. There is no distinction between

First Degree murderers in the law. The distinction is

made and the discrimination lies in the decision of the

jury which hears the case. The petitioner’s attempt to

argue that the power thus granted First Degree Murder

juries hy the law of Ohio to discriminate is invidious does

not succeed. Indeed, in Yick Wo, this Court struck down

a licensing law which permitted discrimination against

individuals of a specific nationality because the evidence

disclosed that persons of Chinese origin had, in fact, been

discriminated against.49 In the instant case, however, there

is no showing and no argument that the operation of Ohio’s

First Degree Murder statute has been unfair or discrim

inatory on the basis of race, creed, color, or any of the

other constitutionally objectionable grounds for discrim

ination. Can there be invidious discrimination in the ab

stract? In the instant case, this Court is asked to declare

a statute unconstitutional because the jury is given cer

tain power within its discretion and not subject to stand

ards in the usual statutory sense. Because the jury is not

bound to specify its standards in the exercise of its judg

ment as to punishment, this Court is asked to create a

presumption that the decisions of a jury in such a situ

ation are irrational, therefore, invidious and therefore

violative of the Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. We fail to see how this Court can find “ in

vidious discrimination in the air.” 50

49. Yick W o v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 373 (1886)

50. See Oyler v. Boles, 368 U. S. 448 (1962).

*

37

In support of petitioner’s claim that his Due Process

rights have been violated, he cites Giaccio v. Pennsylvania,

382 U. S. 399 (1966), in which this Court overturned a

Pennsylvania statute permitting the assessment of costs

against acquitted defendants, among others, and which