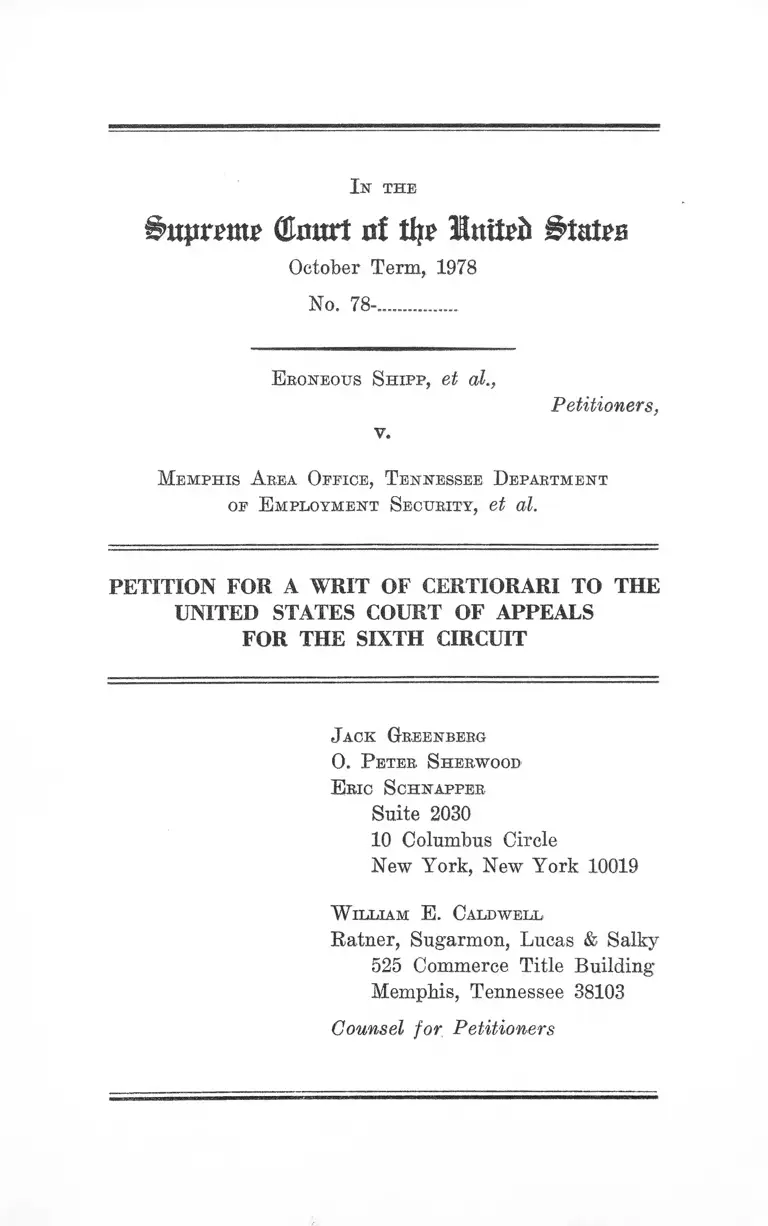

Shipp v TN Department of Employment Security Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1978

93 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shipp v TN Department of Employment Security Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1978. 93877c42-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/49f2ad0c-e0c1-4a83-9d23-042a0ea966e7/shipp-v-tn-department-of-employment-security-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Ik the

(Emtrt of tlje IttttBii States

October Term, 1978

No. 78-..............

E roneous S h ip p , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

M em ph is A rea Oeeice, T ekkessee D epartm ent

oe E m plo ym en t S ecu rity , et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

J ack G reenberg

0 . P eter S herwood

E ric S ch napper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W illiam E . Caldw ell

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas & Salky

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Counsel for Petitioners

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below ............................. 2

Jurisdiction .............................. 2

Questions Presented ................. 2

Statutory Provisions and Rules

Involved ......................... 3

Statement of the Case ............. 4

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT ............. 9

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted To

Resolve A Conflict Among The Circuits

As To Whether An Erroneous Failure

To Certify A Class May Be Corrected

On Appeal Despite An Intervening

Dismissal of the Claims of the Named

Plaintiff ............................ 9

II. The Decision of the Court of

Appeals, Insofar As It Holds That

An Individual Claim of Discrimina

tion Can Be Rejected Without

Deciding Whether There Is A

Pattern or Practice of Discrimina

tion, Is Inconsistent With The

Decision of This Court and of

Three Circuits ....................... 17

III. Certiorari Should Be Granted To

Clarify What Form Of Order Is

Required To Constitute A

"Class Certification" Under

Rule 23(c)(1) ...................... 22

- l

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CONCLUSION .............................. . . 27

APPENDIX

PAGE

Order of the District Court,

December 20, 1974 ............. la

Opinion of the District Court,

September 25, 1975 ............... 9a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals,

August 7, 1978 .................. 39a

Order of the Court of Appeals,

October 26, 1978 ....... 55a

li -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Allen v. Likins, 517 F.2d 532 (8th Cir.

1975) ..................... .......... 10,16

Basel v. Knebel, 551 F.2d 395 (D.C.

Cir. 1977) ......... ................ 11,14

Bradley v. Housing Authority, 512 F .2d

628 (8th Cir. 1975) ................. 10

Burns v. Thiokol Chemical Corp., 483

F. 2d 300 (5th Cir. 1973) ........... . 20

Carter v. Kilbane, 529 F.2d 1370 (6th

Cir. 1975) .......................... 10

Cicchetti v. Lucey, 514 F .2d 362 (1st

Cir. 1975) ................... 12

Cobbledick v. United States, 309 U.S.

323 (1940) .......... 17

Cohen v. Beneficial Loan Corp., 337

U.S. 541 (1949) ..................... 14

Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay, 57 L.Ed.2d

351 (1978) ......................... 2,3,14

Cox v. Babcock & Wilcox Company, 471

F. 2d 13 (4th Cir. 1972) ............ 12

Donaldson v. Pillsbury Co., 554 F.2d

825 (8th Cir. 1977) ................. 10,20

PAGE

- iii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

cont'd

PAGE

East Texas Motor Freight Systems, Inc.

v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 395

(1977) ........................ . 3,8, 13

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) ...............14,20,21,

22,25,26

Frost v. Weinberger, 515 F.2d 57 (2d

Cir. 1975) ............... ......... 11

Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co.

57 L.Ed.2d 364 (1978) ...... ...... 4,15,16

Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co.,

559 F.2d 209 (3rd Cir. 1977) ---.... 11,15

Garrett v. City of Hamtrack, 503

F. 2d 1201 (6th Cir. 1974) ........ 10

Geraghty v. United States Parole

Commission, 579 F.2d 238 (3rd

Cir. 1978) ...................... 11,13

Goodman v.Schlesinger, ____ F,2d ,

18 EPD 18659 (4th Cir. 1978) ....... 12,13

Indianapolis School Commissioners v.

Jacobs, 420 U.S. 128 (1975) ....... 3,13,25

Kremens v. Bartley, 431 U.S. 119 (1977).. 26

Lamphere v. Brown University, 553

F. 2d 714 (1st Cir. 1977) .......... 20

- iv -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

cont 'd

PAGE

Lasky v. Quinlan, 558 F.2d 1133

(2d Cir. 1977) .................... 11

McDonell Douglas Corp v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973) .................. 19,20,21,22

McLish v. Roff, 141 U.S 665 (1891) ..... 17

Napier v. Gertrude, 542 F .2d 825 (10th

Cir. 1976) ........................ 12

Pasadena City Board of Education v.

Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976) ..... 25

Satterwhite v. City of Greenville,

578 F .2d 987 (5th Cir. 1978) ...... 12,13

Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U.S. 393 (1975) ...... 26

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 342

(1977) ............................ 20,21,22

Valentino v. Howelett, 538 F.2d 975

(7th Cir. 1977) ................... 10

Vun Cannon v. Breed, 565 F .2d 1096

(9th Cir. 1977) ................... 12

Walker v. World Tire Corp., 563 F.2d

918 (8th Cir. 1977) .............. 10,16

Weathers v. Peters Realty Corp.,

499 F.2d 1197 (6th Cir. 1974) ..... 10

v

Winokur v. Bell Federal Savings and

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

cont 'd

PAGE

Loan Ass'n, 560 F.2d 271 (7th

Cir. 1977) ......... ........... 10,13,14,16

Zurak v. Regan, 550 F.2d 86 (2d Cir.

1977) ...... . . ...... ....... . . . .

Statutes

11

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ................. 2

28 U.S.C. §1291 ............. ....... 3,17

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VI .. 4

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII .

Rules

Rule 21, Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure ......................

3,4

Rule 23(a), Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure ................ 25,26

Rule 23(b), Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure ................ 4,24,26

Rule 23(c), Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure ........... ..........

Other Authorities

3,22,25,26

3B Moore's Federal Practice

123.01 [11.-1] .............. 22

vx

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1978

No. 78-

ERONEOUS SHIPP, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

MEMPHIS AREA OFFICE, TENNESSEE

DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY,

et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners Eroneous Shipp, et_ £l_. , respect

fully pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to

review the judgments and opinions of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

entered in this proceeding on August 7, 1978 and

October 26, 1978.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The December 20, 1974, order of the district

court, which is not officially reported, is set

out in the Appendix hereto, pp. la-8a. The

September 25, 1975 opinion of the district court,

which is not officially reported, is set out in

the Appendix, pp. 9a-36a. The opinion of the

court of appeals dated August 7, 1978, which is

not yet officially reported, is reprinted in 17

FEP Cases 1430, and is set out in the Appendix,

pp. 37a-54a. The order of the court of appeals

denying rehearing, dated October 26, 1978, is set

out at pp. 55a-56a of the Appendix.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals was

entered on August 7, 1978. Petitioners filed a

timely Petition for Rehearing, which was denied on

October 26, 1978. This Court has jurisdiction

under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Where a district court erroneously

fails to certify a class action and subsequently

dismisses the individual claim of the named

plaintiff, can that failure be corrected on

appeal, pursuant to Coopers & Lybrand v. Live say,

- 3 -

57 L.Ed.2d 351 (1978), or does East Texas Motor

Freight System, Inc, v. Rodriguez, 431 U,S. 395

(1977) preclude an appeal from such an error?

2. In a Title VII action alleging a class

wide policy of discrimination, may the individual

claim of the named plaintiff be decided without

considering whether there is in fact such a

policy?

3. In order to "properly certify" a class

action under Indianapolis School Commissioners

v. Jacobs, 420 U.S. 128 (1975), need a district

court do more than comply with the literal lan

guage of Rule 23(c)(1) by "determin[ing] by order

whether it is to be so maintained"?

STATUTORY PROVISIONS AND RULES INVOLVED

Section 1291, 28 U.S.C., provides in perti

nent part:

The courts of appeals shall have jurisdiction

of appeals from all final decisions of the

district courts of the United States....

Rule 23(c)(1), Federal Rules of Civil Proce

dure, provides:

As soon as practicable after the commencement

of an action brought as a class action,

the court shall determine by order whether it

is to be so maintained. An order under this

subdivision may be conditional, and may be

altered or amended before the decision on the

merits.

- 4 -

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action was commenced on September 16,

1971, against the Memphis Area Office of the

Tennessee Department of Employment Security

(hereinafter "TDES"), a state operated employment

service largely supported by federal funds. The

complaint alleged that TDES had a policy of

referring white applicants to better paying jobs

than those offered to equally qualified black

applicants. Plaintiff alleged that this discrimi

nation was the result in part of discrimination in

the selection of the TDES counsellors involved in

making the referrals. These practices were

alleged to violate Title VI and Title VII of the

1964 Civil Rights Act. Plaintiff, a black appli

cant whom TDES had refused to refer to a particu

lar job, sought relief for himself and for a class

of blacks alleged to be the victims of these

practices.

The complaint specifically alleged that each

of the requirements for a Rule 23(b)(2) and a Rule

23(b)(3) class action were met. TDES claimed it

had no policy of discrimination, but did not deny

any of plaintiff's detailed allegations of numer-

osity, typicality, etc. Extensive discovery was

- 5 -

conducted from 1971 to 1974, most of it with

regard to what were specifically denoted as the

merits of the "class issues". At a pre-trial

conference on March 8, 1974 plaintiff expressly

sought a more formal ruling on the propriety of

the class action, but the district court never

entered any such ruling. The parties are in

disagreement as to the reason for the district

court's inaction; plaintiff maintains that the

court took no formal action because counsel for

TDES stipulated at the March 8,1974 conference

that the case was a proper class action.

The trial of this action was held in two

phases. From March 20-22, 1974, plaintiff pre

sented his case in support of both his individual

claim and the class claim, and TDES offered

its defense to the individual claim. TDES was

granted time to prepare its defense to the class

claim; that evidence was finally presented at a

second hearing on April 23, 1975.

With regard to the individual claim, the

testimony at trial revealed that TDES had refused

to refer plaintiff for a vacancy in the shipping

department of the local RCA plant, although

- 6 -

plaintiff was a former military officer who had

extensive experience managing shipments at an Air

Force base in Europe. TDES officials asserted at

the time of the refusal that plaintiff was un

qualified because he was unfamiliar with shipping

rates in the area, but the white applicant hired

for the RCA job testified that the position did

not in fact require any knowledge of those rates.

Plaintiff also established that in the years

prior to trial the average hourly wage of posi

tions to which TDES applicants were referred were

as follows:

The average wage difference between whites and

blacks was $.38 an hour. TDES classifies appli

cants into occupational categories according to

their experience and level of skill. In the 16

largest categories, within which experience and

skill levels were comparable according to TDES,

white males got better paying jobs than black

Type of Applicant Average Wage

White males

Black males

White females

Black females

$2.56

$2.25

$2.25

$1. 77

- 7

males in every category. There were 13 major

categories, all poorly paid, in which over 90%

of the referrals were black, including domestic

worker (100%), laundress and laundryman (99%)

and janitor (95%). The TDES operations in

Memphis, which until the early 1960's operated on

an officially segregated basis, continued to use

racially identifiable offices.

The district court, however, found for

defendant TDES on both the individual and class

claims. With regard to the claim of the named

plaintiff, it is unclear from the opinion of the

district court whether it concluded that plaintiff

had been denied referral for reasons other than

race, or that such discrimination had caused no

injury because the job at issue had already been

filled. 7a-8a. The district court decision

regarding the named plaintiff was initially

issued on December 20, 1974, prior to completion

of the trial of the class claims. Plaintiff

promptly moved for reconsideration of the indivi

dual claim after a decision on the class claim,

and the district court in fact reconsidered and

reaffirmed its rejection of the individual claim

- 8 -

after deciding the class claim. 36a. With

regard to the class claims, the district court

found that the wide disparity in the wage levels

was primarily the result of past racial discrimi

nation by private employers and "the community"

rather than by TDES itself. 31a-35a.

On appeal the Sixth Circuit refused to

consider the merits of the class claim. It upheld

the dismissal of the claim of the named plaintiff,

but it is again unclear whether the appellate

court believed the district court had found no

discrimination or no injury, and which finding it

was affirming. 49a-50a. The court of appeals did

not reach the merits of the class claims; it held,

rather, that none of the district court orders

regarding the class constituted an adequate

certification of the class. 51a-54a. Plaintiff

urged that, if the district court orders were

inadequate, that error could and should be

corrected on appeal. The Sixth Circuit, however,

concluded that since the district court subsequent

to that error had rejected the claim of the named

plaintiff, dismissal of the class claim was re

quired by East Texas Motor Freight Systems,

Inc, v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 395 (1977). 53a-54a.

- 9 -

Plaintiffs filed a timely Petition for

Rehearing, and moved, under Rule 21, Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, to add additional

plaintiffs. On October 26, 1978, the court

of appeals denied the Petition for Rehearing, and

held that it lacked jurisdiction to add parties to

the action.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted To Resolve

A Conflict Among The Circuits As to

Whether An Erroneous Failure To Certify

A Class May Be Corrected On Appeal

Despite An Intervening Dismissal of the

Claims of the Named Plaintiff

This case presents an important and recurring

procedural problem. As viewed by the Sixth Cir

cuit the district judge, despite two requests

by plaintiff's counsel, erroneously failed to

decide whether the case should be formally certi

fied as a class action. By the time the case

1_/ As we note infra, we maintain that the

district court did adequately certify the class,

PP- 21-26, and that the court of appeals erred in

deciding the individual claim without first

deciding the class claim. Pp. 17-21.

- 10 -

reached the court of appeals, however, the dis

trict court had decided against the named plain

tiff on the merits of his individual claim, a

decision the appellate court upheld. Petitioner

urged that the court of appeals should correct the

erroneous lack of certification. The Sixth

Circuit, however, concluded that it was powerless

to correct that error since plaintiff, although

presumably a proper class representative when

certification was first sought, had subsequently

been held to have no personal claim and thus not

to be a member of the alleged class. 51a-54a.

The circuits are widely divided on this

• 2/issue. In addition to the Sixth Circuit,— the

3/ 4/Seventh— and Eighth Circuits— hold that an

2/ The Sixth Circuit's position prior to the

instant case had been unclear. See Carter v.

Kilbane, 529 F.2d 1.370, 1371 (6th Cir. 1975);

Garrett v. City of Hamtrack, 503 F.2d 1201 (6th

Cir. 1974); Weathers v. Peters Realty Corp., 499

F.2d 1197 (6th Cir. 1974).

3/ Winokur v. Bell Federal Savings and Loan

Ass1 n , 560 F.2d 271 (7th Cir. 1977); Valentino v.

Howlett, 528 F.2d 975, 979-81 (7 th TIT! 1977).

4/ Walker v. World Tire Corp., 563 F. 2d 918,

921-23 (8th Cir. 1977); Allen v. Likins, 517

F . 2d 532, 534-35 (8th Cir. 1975); Bradley v .

- 11

erroneous denial of certification cannot be

corrected on appeal if in the interim the named

plaintiff ceased to be a proper representative.

c / r j

The S e c o n d T h i r d a n d District of Colum

bia—^Circuits take the opposite position, hold

ing that an erroneous failure to certify can

be reviewed and corrected by an appellate court,

and that the appellate decision regarding certi

fication "relates back" to the date on which

the district court failed to certify the class.

4J Cont 'd

Housing Authority, 512 F.2d 626, 628-29 (8th Cir.

1975); but see Donaldson v. Pillsbury Co., 554

F .2d 825, 831-2 n.5 (8th Cir. 1977).

5/ Lasky v, Quinlan, 558 F .2d 1133, 1136-37

(2d Cir. 1977); Zurak v. Regan, 550 F . 2d 86,

91-91 (2d Cir. 1977); Frost v. Weinberger, 515

F.2d 57, 64 (2d Cir. 1975).

6/ Geraghty v. United States Parole Commission,

579 F.2d 238, 245-254 (3rd Cir. 1978); Gardner v .

Westinghouse, 559 F . 2d 209, 214-17 (3rd Cir.

1977) (Seitz, J. concurring), aff'd 57 L.Ed. 2d

364 (1978). Geraghty relied on the decisions of

the Second and District of Columbia Circuits. 579

F.2d at 250 n.48.

V Basel v. Knebel, 551 F.2d 395 , 397 , n.l

(D.C.Cir. 1977).

- 12 -

Other circuits have adopted a variety of

intermediate standards. In the Fifth Circuit an

erroneous denial of certification can be corrected

on appeal if the plaintiff sought an evidentiary

hearing on the propriety of certification, but

8 /apparently not otherwise.— The practice of the

Fourth Circuit is to decide whether the denial of

certification was erroneous, but not to permit the

original plaintiff to represent the class; in

stead the case is remanded to the district court

with instruction that the case is to "be retained

on the docket for a reasonable time to permit

a proper plaintiff ... to present himself to

9 /prosecute the action."— In the Tenth Circuit the

denial of certification can and must be corrected

on appeal if failure to do so would mean that the

claim would "evade review."A5/

8/ Satterwhite v.City of Greenville, 578 F.2d

9 8 7 , 995-96 n.10 (5th Cir. 1978) (en banc), cert

pending No. 78-1008.

9/ Goodman v. Schlesinger, F . 2d ,

18 EPD 18659, p. 4607 (4th Cir. 1978); Cox v .

Badcock & Wilcox Company, 471 F.2d 13, 16 (4th

Cir. 1972).

10/ Napier v. Gertrude, 542 F.2d 825, 828 (10th

Cir. 1976). The issue is apparently unresolved

- 13

The existence of this conflict is widely

recognized. The Third Circuit, noting that the

Fifth and Seventh Circuits had adopted rules

different than its own, stated:

We acknowledge that the courts of

appeals are divided on the question of

whether under the recent Supreme Court

decisions, the denial of class action status

is appealable by a named plaintiff whose

claim has become moot. Geraghty v. United

States Parole Commission, 579 F.2d 238, 251

n.19 (3rd Cir. 1978);

The Fourth Circuit recently conceded that its

rule "is apparently contrary to the [Fifth Cir

cuit] Satterwhite majority." Goodman v. Schlesin-

ger, ____ F. 2d ____, 18 EPD 18659, p. 4607 (4th

Cir. 1978). Satterwhite in turn referred to the

more restrictive Seventh Circuit decision with an

understated "but see". Satterwhite v. City of

Greenville, 578 F. 2d 9 8 7 , 996 ( 5th Cir. 1978).

This conflict reflects a disagreement among

the lower courts as to the meaning of recent

decisions of this Court. In holding that an

10/ Cont'd

in the First and Ninth Circuits. See Cicchetti

v. Lucey, 514 F . 2d 362, 368 (1st Cir. 1975).

Vun Cannon v ■ Breed, 565 F.2d 1096, 1101 n.7 (9th

Cir. 1977).

14

erroneous denial of certification cannot be

appealed if the claim of the named plaintiff has

been rejected, the Sixth and Seventh Circuits

analogized such a case to Rodriguez v. East Texas

Motor Freight, 431 U.S. 395 (1977), where certifi

cation had never been sought, and Indianapolis

School Commissioners v. Jacobs, 420 U.S. 128

(1975), where an inadequate certification had

never been appealed. 53a-54a; Winokur v. Bell

Federal Sav. & Loan Ass 'n, 560 F.2d 271 , 276

(1977) . In permitting an appeal the District of

Columbia Circuit suggested such a case is closer

to Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976), where the case was certified before

the claim of the named plaintiff became mo.ot.

Basel v. Knebel, 551 F.2d 395, 397 n.l (D.C. Cir.

1977).

We contend that the issue presented by this

Petition is controlled by the recent decisions of

this Court holding that a denial of certification

may not be the subject of an interlocutory appeal.

Coopers & Lybrand v, Livesey, 57 L.Ed. 2d 351

(1978) ; Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co.,

57 L.Ed. 2d 364 (1978). In Coopers & Lybrand,

this Court rejected a claim that such a denial was

- 15 -

"effectively unreviewable on appeal from a final

judgment" and thus an appealable collateral order

under Cohen v. Beneficial Loan Corp., 337 U.S. 541

(1949); this Court insisted that "an order denying

class certification is subject to effective review

after final judgment at the behest of the named

plaintiff...." 57 L.Ed. 2d at 358 (emphasis

added). In Gardner the Court held that denial of

certification was not an "irreparable" denial of

class injunctive relief, emphasizing that "if,

after judgment on the merits, the relief granted

is unsatisfactory, the question of class status is

fully reviewable." 57 L.Ed.2d at 368 n.6 (emphasis

added). This passage is a quotation from the

Third Circuit opinion in Gardner, and there the

evident concern of the court of appeals was to

insist that a denial of certification could be

appealed after final judgment regardless of

whether that judgment rejected or mooted the

claims of the named plaintiff. Gardner v .

Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., 559 F.2d 209,

214-15 (3rd Cir. 1977) (Seitz, J., concurring).

The decision below, and many of the conflict

ing decisions in other circuits, address the

situation where a named plaintiff no longer has an

- 16

active claim against the defendant because

his claim was rejected on the merits. But the

same problem arises if the named plaintiff pre

vails, for should full relief be awarded to him

and the defendant not appeal, the dispute between

the defendant and the named plaintiff would

be moot. Thus the Eighth Circuit has held that

a named plaintiff is barred from appealing a

denial of certification not only when his claim

has been re jected,— ^but also when he has obtained

all the relief he personally sought in the ac-

1 2 /tion.— The Seventh Circuit has held that

a defendant can deliberately prevent an appeal

from a denial of certification simply by tendering

the plaintiff all the relief he personally re-

1 3 /.quested, thus mooting his claim.— 'if these

decisions are correct, appellate review after

final judgment of a denial of certification would

11/ Walker v. World Tire Corp., 563 F.2d 918 (8th

Cir. 1977).

12/ Allen v. Likins, 517 F,2d 532 (8th Cir. 1975).

13/ Winokur v. Bell Federal Sav. & Loan Ass'n, 560

F.2d 271, 274 (7th Cir. 1977).

- 17

be impossible, not merely in some cases, but in

most. If that is so Gardner and Coopers & Lybrand

were incorrectly decided.

The decision in this case, like the similar

rule in the Seventh and Eighth Circuits, creates

an unprecedented anomaly in federal law: an

erroneous district court decision denying certifi

cation, or an erroneous failure to act on a

request for certification, is absolutely insulated

from appellate review. In authorizing appeals

from "final orders" under 28 U.S.C. §1291, it was

the intent of Congress that that appeal bring up

with it all previous orders entered and actions

taken by the district court, "to have ‘the whole

case and every matter in controversy in it decided

in a single appeal." McLish v. Roff, 141 U.S.

661, 665 (1891). Postponement of appellate review

of a denial of certification is intended only to

determine when that review is to occur, not to

"defeat the right to any review at all." Cobble-

dick v. United States, 309 U.S. 323, 324-25

(1940).

- 18 -

II* The Decision Of The Court of Appeals,

Insofar As It Holds That An Individual

Claim of Discrimination Can Be Rejected

Without Deciding Whether There Is A Pattern

or Practice of Discrimination, Is Incon

sistent With The Decisions of This Court

and of Three Circuits

In deciding the individual claim of the named

plaintiff, the district court repeatedly recog

nized that the resolution of that claim depended

to a substantial degree on whether, as plaintiff

claimed, the defendant had engaged in a general

practice of discrimination against black appli

cants. After hearing all the evidence on the

individual claim, the trial judge agreed to defer

any decision on it until he could decide the class

claim as well.— The judge subsequently issued a

tentative opinion on the individual claim, holding

that the plaintiff had failed to meet his burden

14/ Transcript of Hearing of March 22, 1975,

pp. 129-130.

- 19 -

of proving discrimination. 7a-8a. But the trial

court agreed to reconsider its view of the

individual claim after deciding the class claims,

and only finally rejected the individual claim

on the basis of its determination that there was

no general practice of discrimination. 36a. On

appeal the .Sixth Circuit proceeded in an entirely

different manner. It disposed of Shipp's personal

claim in a single unexplained sentence asserting

that the finding of no discrimination was "not

clearly erroneous", 49a-50a; but it expressly did

not decide whether the district court had erred in

finding no class-wide discrimination, even though

that finding was a foundation of the district

court's rejection of the individual claim.

54a. .

This Court has repeatedly held that the

existence of a pattern of discrimination is of

critical importance to resolving a claim of

discrimination against a particular individual.

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792, 804-805 (1973), held that a defendant's

"general policy and practice with respect to

minority employment" would be relevant to a claim

- 20

that the plaintiff there had been rejected for

employment because of his race. Both Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 357-62 (1977), and

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co, 424 U.S. 747,

772-73 (1976), hold that proof of a general

practice of discrimination shifts to the defendant

the burden of proof, requiring it to establish

that an unsuccessful minority applicant was not

rejected because of his or her race.

Under Teamsters, Franks and Me Donne 11

Douglas an individual claim of discrimination

cannot ordinarily be decided without first decid

ing whether there is a class-wide pattern of

discrimination. Three circuits expressly require

that the plaintiff be permitted to establish the

latter issue prior to a determination of the

former

The court of appeals in the instant case

refused to decide the merits of the class claim of

15/ Lamphere v. Brown University, 553 F.2d 714,

719 (1st Cir. 1977); Burns v. Thiokol Chemical

Corp., 483 F .2d 300, 306 (5th Cir. 1973); Donald-

son v. Pillsbury Co. , 554 F.2d 825, 832-33 (8th

Cir. 1977), cert, denied 434 U.S. 856 (1977).

- 21

a pattern and practice of discrimination, even

though that was the foundation of the district

court's opinion. It upheld the district court's

conclusion of no discrimination against Shipp

without considering the correctness of the dis

trict court's premise that there was no general

practice of discrimination. This resolution of

the merits was inconsistent with Franks, Team

sters , McDonnell Douglas and the practice in

other circuits.

This issue is inextricably intertwined with

the first Question Presented. Even in a case

where a trial judge erroneously denies certifica

tion, the individual plaintiff would be entitled

under Franks, Teamsters, and McDonnell Douglas to

discover and introduce evidence of a general

practice of discrimination in support of his own

claim. Ordinarily a district court finding of no

discrimination against the named plaintiff could

not be upheld if the court of appeals found there

was a class-wide pattern or practice of dis

crimination. Thus the only way an appellate court

could reject an individual claim and then dismiss

a possibly meritorious class claim for want of a

proper representative would usually be to dis

- 22 -

regard Franks, Teamsters and McDonnell Douglas and

refuse in passing on the individual claim to

consider whether there was a general practice of

discrimination. Consequently in this case, as in

most others, the court of appeals only had an

opportunity to erroneously dismiss the class claim

because it had first erroneously rejected the

individual claim.

III. Certiorari Should Be Granted To Clarify

What Form Of Order Is Required To

Constitute A "Class Certification" Under

Rule 23(c)(1)

Rule 23(c)(1), Federal Rules of Civil Proce

dure, provides in pertinent part:

As soon as practicable after the commencement

of an action brought as a class action,

the court shall determine by order whether it

is to be so maintained.

The Committee Note indicates that the Rule means

simply what it says, that the order must determine

"whether an action brought as a class action is to

be so maintained." 3B Moore's Federal Practice

f23.01[11.—1] (emphasis added). Until the deci

sion in this case, no opinion of this or any lower

court read Rule 23(c)(1) other than in that

literal manner.

- 23

The Sixth Circuit did not question that the

district judge had in fact determined "whether"

the case was to be maintained as a class action;

on the contrary, it noted that there had actually

been a "trial on the merits of the class action

claims" and a decision "on the merits" of those

claims. 40a-42a, 46a n.15. Nor is there any

suggestion that the district judge, having deter

mined that the case could proceed as a class

action, failed to enter an order memorializing

that determination. Actually there are ten such

orders. The trial judge issued four orders au

thorizing and regulating discovery expressly bear-

16/ing on "the class action issue of the case",—

and five orders, including the pretrial order,

providing for how and when the "class action

aspect of the case" was to be tried.— ^In its

16/ Court of Appeals Appendix, pp. 21a (July 16,

1973), 30a (December 11, 1973), 48a (December 17,

1973). A fourth order was issued on March 15,

1973.

17/ These orders were issued on March 11, 1974,

March 22, 1974, June 13, 1974 (id_. p. 738a),

December 20, 1974 (id. p. 744a) and January 5,

1975.

- 24

decision on the merits the district court included

a finding that it had "jurisdiction of ... the

class action allegations made by plaintiff Shipp".

31a,

The Sixth Circuit, however, found all of

these orders insufficient to meet the requirement

of Rule 23(c)(1). Its opinion suggests the dis

trict court orders were inadequate for three

reasons. First, the court of appeals objected

that the trial judge had failed to make detailed

findings that each of the requirements of Rule

23 were met.— 'Second, the court of appeals

complained that the trial judge had failed to

specify the subsection of Rule 23(b) under which

the class action was to proceed. 47a-48a.

Third, the court of appeals repeatedly stressed

that the trial judge had failed to "certify" the

class, indicating that the use of this term was

necessary or of special importance. 47a.

18/ "[T]he district court never ... made any

determination that the prerequisites for a class

action were met, specifically that plaintiff's

claims were typical of the claims of the class

or that plaintiff would fairly and adequately

protect the interests of the class pursuant to

Rule 23(a)." 46a.

- 25

The court of appeals apparently based these

requirements, and its conclusion that the class

was not "properly certified", on its reading

of Indianapolis School Commissioners v. Jacobs,

420 U.S. 128 (1975). 53a. But Jacobs does not

require that a Rule 23(c)(1) order do more than

actually determine whether a case may be main

tained as a class action. In Jacobs the order

rejected as insufficient by the majority stated

only that plaintiffs were "qualified as proper

representatives of the class whose interest they

seek to protect." 420 U.S. at 130. This clearly

did not decide whether the action was to be heard

as a class action, but merely held that the

requirement of Rule 23(a)(4) had been satisfied.

Similarly in Pasadena City Board of Education v .

Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 (1976), counsel for the

parties had "treated [the case] as a class

action", 427 U.S. at 430, but there was no proof

the trial court had done so.

On three occasions this Court has held the

order of a district court sufficient to satisfy

the requirements of Rule 23(c)(1) and thus of

- 26 -

Article III. Kremens v . Bartley, ̂ ^431 U.S.

119 (1977); Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co. ,— ^424 U.S. 747 (1976); Sosna v. Iowa,— ̂

419 U.S. 393 (1975). None of the orders approved

by this Court could meet the three-part standard

set out by the Sixth Circuit below. None of the

orders in Kremens, Franks and Sosna made express

findings that each of the particular requirements

of Rule 23(a) and (b) were met, and none of them

used the term "certify". The order in Sosna

neither specified the subheading of Rule 23(b)

being utilized nor defined the class. The deci

sion below is clearly inconsistent with this

Court's approval of the orders in Kremens, Franks

and Sosna.

The Sixth Circuit's requirements for a Rule

23(c)(1) order, if applied only prospectively,

would nonetheless be erroneous. But the court of

19/ The order is set out at p. 270a of the

Appendix, No. 75-1064, October Term, 1976.

2QJ The order is set out at p. A53 of the Appen

dix, No. 74-728, October Term, 1975.

21/ The order is set out at pp. 45-46 of the

Appendix, No. 73-762, October Term, 1974. The

document in Sosna was a stipulation of fact

approved by the district court. 419 U.S. at

397-98.

- 27

appeals applied those newly announced standards to

orders issued three to four years earlier. The

retroactive application of such a construction of

the Federal Rules is certain to wreak havoc in

other cases as it did here, for few Rule 23(c)(1)

orders would meet those standards. Otherwise well

tried cases will have to be dismissed because of a

failure to meet procedural standards of which

neither counsel nor the trial court could have

been aware. To do so would be to elevate form

over substance in a manner entirely inconsistent

with the purposes of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure.

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons a Writ of Certiorari

should issue to review the judgment and opinion of

the court of appeals.

- 28

Respectfully submitted.

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Ratner, Sugarmon,

Lucas & Salky

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Counsel for Petitioners

APPENDIX

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

WESTERN DIVISION

No. C-71-373

ERONEUS SHIPP, Individually and on

behalf of all others similarly

situated,

Plaintiff,

v.

MEMPHIS AREA OFFICE OF THE TENNESSEE

DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY,

et al. ,

Defendants.

ORDER

Plaintiff, a black male, has sued the Memphis

Area Office of the Tennessee Department of Employ

ment Security, the Tennessee Department of Person

nel, and Jane L. Hardaway, its (former) Commis

sioner, for alleged racial discrimination with

la -

respect to its failure to refer him to a job

through the Tennessee Department of Employment

Security at Memphis, Tennessee. Jurisdiction is

asserted under the post-Civil War civil rights

acts and the 1964 Civil Rights Act as amended

(Title VII). By order of the Court, after ex

tended discovery, trial was had on Shipp's

claim with opportunity for defendants to respond

at a later hearing on the merits of the class

action claim.

Plaintiff, a native Memphian and a college

graduate, has considerable service as an officer

in the Army Air Force in handling military corgo

and passengers. After termination of his military

service as a first lieutenant, he attended gradu

ate school for a time in 1963, but was unable to

obtain suitable employment in New York City where

he was then living. After unsuccessfully applying

for employment in Memphis in 1964, he taught for

several years in Arkansas public schools and then

taught language and English in the Memphis City

School System after obtaining a required certifi

cate in Tennessee. On Friday, March 7, 1969,

after hearing a radio broadcast the day before

©

- 2a -

initiated by the Memphis Office of the Tennessee

Department of Employment Security, Shipp called to

inquire about a job opening for an assistant or

analyst in a traffic department. He talked to

Mrs. Ewing in the Tennessee Department of Employ

ment Security office about his interest and

background and was advised to come in for an

interview for possible employment on March 11,

although she was not encouraging that his qualifi

cations were suitable for this particular spot.

He reported in person, however, on March 10, with

an application, and talked to Mrs. Askew at

the Tennessee Department of Employment Security

office. She also discouraged him about the

particular job which offered higher pay than the

approximately $6,700.00 Shipp had been earning,

since the job required heavy experience in rates,

and suggested that he consider other possible

openings.

Shipp, suspicious that he was being shunted

aside, demanded an opportunity to interview the

employer. Mrs. Askew responded that it was

against policy to reveal the "client's” or pros

pective employer's name unless the Tennessee

- 3a -

Department of Employment Security itself con

sidered the applicant qualified and recommended

the interview. With notebook and pencil in hand,

Shipp began to take notes of his interview with

Askew, who at his insistence, then dialed on the

telephone the employer, RCA at Memphis.

Shipp did not believe Mrs. Askew-^actually

made the call, but heard one side of the purported

telephone conversation while she spoke to Robert

Phillips in the RCA personnel office and heard her

ask if the job were filled. She then informed

Shipp that the job was not open, that the employer

did not consider his background sufficient for the

job and was not interested in an interview. Still

not having RCA's name divulged as the prospective

employer, Shipp even more dissatisfied, then

demanded to speak to Mrs. Ewing who had returned

to her desk in the commercial and sales division

of the Tennessee Department of Employment Security

office during the course of his discussion with

Mrs. Askew. He stated he did not believe Mrs.

Askew had actually made the call but had only

JV Mrs. Askew was a supervisor, Mrs. Ewing an

interviewer, at the time in the same department.

Both are white.

- 4a -

pretended to do so, and was still apparently

taking notes of what was taking place. At

this time, Shipp intimated that he felt he was

being mistreated and misled by reason of his

negro race in connection with this job. He

wondered why the job was already filled under

the circumstances known to him, and indicated no

interest in other possible openings. Despite

Shipp's insistence, Ewing refused to call RCA

again, stating she could not try to bypass

her supervisor. Shipp was taken to the Tennessee

Department of Employment Security manager's office

after asserting these complaints, which created

something of a commotion in this division of the

Tennessee Department of Employment Security.

Unknown to Shipp, however, RCA's personnel

office had also solicited job applicants from

private employment services during February of

1969, as well as the Tennessee Department of

Employment Security for the traffic department

job, dealing particularly with transportation and

shipping rates. The Tennessee Department of

Employment Security submitted several potential

names of white persons for the job to RCA prior to

the Shipp episode, and Phillips had several

5a -

conversations with Ewing indicating a desire for

recent rate experience. Phillips also interviewed

one B. E. Fletcher during February, then employed

at Central Soya, and on or about March 4, 1969,

Fletcher gave his employer notice that he intended

to resign and accept the RCA position in contro

versy. Phillips, however, did not then notify the

Tennessee Department of Employment Security that

the job was considered filled, even though

Fletcher had prospectively been offered the job to

report about mid-March. RCA at the time had

an affirmative action program after some contact

with E.E.O.C. representatives. Phillips did not

know Shipp's race and was not told his race on

March 10th when Askew of the Tennessee Department

of Employment Security discovered the job was no

longer open.

Evidence was presented on Shipp's behalf of a

background indicating segregation by race prior

to 1964 in Tennessee Department of Employment

Security employment offices. Evidence was also

presented showing a preponderance of whites in

managerial, supervisory and interviewer positions

in the Tennessee Department of Employment Security

office in Memphis in 1969. Statistical evidence

- 6a -

was also offered with analyses, which plaintiff's

counsel asserts is indicative of a plan, practice,

or effective result of racial discrimination

by this office (and defendants) at the time suit

was instituted and when Shipp's interview took

place.

The Court concludes, however, that Shipp

himself has failed to demonstate racial prejudice

or discrimination against him in connection with

his job application and his transactions with

the Memphis Tennessee Department of Employment

Security Office in March of 1969, Shipp has

failed to prove the charges made by him against

any of the defendants. As an aside, it is

pertinent to note that Shipp also failed to prove

any damage whatsoever by reason of his not receiv

ing the RCA job. That Memphis operation closed

about six months later and most employees lost

their jobs. Both Phillips and Fletcher in the

fall of 1969, had to seek other employment. Shipp

himself averaged some $7,500 in earnings during

1969-1970, and 1970-71 school years.

The cause of action brought by Eroneous Shipp

is dismissed and he will bear his own costs which

are assessed against him. This dismissal, how-

7a

ever, is without prejudice to the consideration of

the class action claims, equitable in nature,

seeking affirmative relief against defendants for

alleged unlawful discriminatory employment prac

tices. Nothing indicated in this order is in

tended to be a determinative finding or conclusion

with respect to the asserted class action claim.

A hearing on the merits of the latter claim

is set for January 6, 1975, at 9:30 A.M.

This _____ day of December, 1974.

Harry W. Wellford /s/_____________

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT JUDGE

Filed: December 20, 1974

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

WESTERN DIVISION

No. C-71-373

ERONEUS SHIPP, Individually and on

behalf of others similarly

situated,

Plaintiff,

v.

MEMPHIS AREA OFFICE OF THE TENNESSEE

DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY,

et al.,

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM OPINION

Plainiff, Eroneus Shipp, commenced this

action by complaint filed on September 16, 1971,

against defendant Memphis Area Office of the

Tennessee Department of Employment Security (here-

9a

after called, as indicated, "Memphis Area Office,"

"Memphis Office," or "TDES"). This was filed as a

class action on behalf of similarly situated black

persons charging defendant with individual and

class-wide race-based discrimination in its job

referral and related services, as well as in its

own employment practices. Such alleged racially

discriminatory actions were asserted to violate

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. §200 et_ seq., [sic.] the Civil Rights Act

of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981, and 42 U.S.C. §1983, as

well as the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States. Plaintiff sought

individual as well as class-wide equitable relief

against defendant.

The court entered an order on December 20,

1974, after hearing with respect to Shipp's

individual claim, denying him relief but without

adverse effect upon the class action aspects of

the case. Further hearings were held as to the

latter asserted class action claims, and expert

testimony was adduced by both sides.

The basic issues involved were (1) whether

blacks, because of race, were referred to em

ployers by TDES to jobs poorer in quality and in

10a -

pay than those to which whites were referred; (2)

whether TDES failed to use appropriate and/or

necessary procedures to eliminate relationships

with allegedly racially discriminatory employers;

(3) whether TDES discriminated against blacks in

internal hiring and promotion practices; and (4)

whether TDES established or continued the racial

identifiability of certain job categories because

of past racial practices.

TDES was created in response to the problems

spawned by unemployment. It consists of two

coordinate divisions, the unemployment compensa

tion division and the state employment service.

T.G.A. §50-1332. The employment service division

is financed by the United States Department of

Labor to maintain free public employment offices

throughout the state pursuant to 29 U.S.C. §§49 to

49(k), and subsequent federal legislation.

(T.C.A. §50-1346). The employment service divi

sion in Memphis is the subject of this litigation.

Historically the Memphis Area Office operated on a

racially segregated basis until the late 1950's.

A separate office serving primarily blacks was

maintained in Memphis by TDES until approximately

11a

1 9 6 0 Subsequently the office was moved to a

new location serving both whites and blacks,

although the domestic and casual labor office

continued to deal primarily with black employees.

When all the activities were combined in a single

office at 1295 Poplar in 1969 , this Memphis

office of IDES handled a full range of both white

and black clientele. After the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 was adopted, however, explicit racial

specifications for jobs or applicants were elim

inated, although by 1962 blacks were being serv

iced by the office which had formerly handled

white job applications. The TDES staff in the

primary office at 1295 Poplar began to be filled

with a significant number of blacks by 1968,

whereas before it was predominantly but not

exclusively white in racial make-up.

In 1970, significantly altering the operation

of TDES in Memphis, a Job Bank computer-assisted

information system, was implemented, and Memphis

was selected by the Department of Labor as one of

a handful of cities to participate in an experi

mental "Conceptual Model" (hereafter, "COMO")

_!_/ This was separate from a farm office which

serviced primarily black farm laborers.

12a -

approach to the delivery of manpower services.

Prior to that time TDES interviewers specialized

in occupational categories, and they dealt with

both employers and applicants in their assigned

occupational "specialities." These interviewers

viewed and referred applicants seeking jobs, and

would conduct "file searches" in an effort to

match pending job orders in the specified occupa

tions with pending applications for those par

ticular jobs. Applicants could find out what

jobs were available from interviewers.

The Job Bank program came into being under

Manpower Development and Training Act to improve

the problem of communication about jobs. The Job

Bank is designed to afford more immediate avail

ability of orders through a central control and to

allow city-wide exposure of applicants to listed

jobs. A part of the philosophy behind the Job

Bank program was the improvement of opportunities

for disadvantaged persons and minorities. One of

the intended benefits of the design of the Job

Bank was to separate job order-taking from the

interviewing and referral process. It was hoped

that this program would help disadvantaged appli

cants in the availability of openings to all

13a -

interviewers so as to reduce the danger of "play

ing favorites." It was also expected that the new

computerized information-gathering system would

better enable local employment service offices to

identify the characteristics of job-seekers

who are not recieving maximum benefits of such

service. This program, according to one of

plaintiff's own experts did not produce in Memphis

or elsewhere all the desired effects and ad

vantages .

On April 15, 1970, the Memphis Office began

the COMO operational program in conjunction

with the Job Bank system, again with a primary

goal of serving the disadvantaged more adequately,

and the "hard core" unemployed. The purpose of

the COMO design was to improve the manpower

delivery system by "self-service use by job ready

applicants of a computerized Job Bank listing of

job openings and other information about job

opportunities;" "job-finding assistance and

instruction, job development, and job market

information for applicants who are unsure of

their degree of job-readiness;" "a controlled

caseload, team approach to provide a hard-core

and disadvantaged with the full range of intensi

14a -

fied manpower services." The Memphis TDES

office was organized in a manner deemed effective

to deliver all of these levels of service to those

with greatest need for manpower services.

A detailed application card is filled out

when an applicant at TDES applies. It reflects

the applicant's work history and other information

2 /necessary for occupational or DOT coding— and

other information necessary for referral action.

The back of this application card contains in

formation pertaining to test results, if any,

and other special information, as well as a

record of job referral action for the particular

applicant and follow-up contact information. For

those who have not previously filed applications,

there is an intake and briefing session which

explains the operation of the office. Applica

tions are filled out at the receptionist desk and

2/ The Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT)

is a system of coding types of jobs designed by

the Department of Labor. The system utilizes a

six-digit code in which the first three digits

indicate the job or the occupation, and the second

three digits indicate to what extent particular

job requires the employee to relate to data, to

relate to people, and to relate to things.

15a -

filed by occupational code with a cross index.

The applications are maintained on file until the

applicant is placed, or until 60 days from the

last contact. Applicants who are not "job ready"

or who need more special attention for some reason

are referred to counselors. A more detailed

counseling control card is maintained for this

group of job seekers. Applicants who do not need

special attention or help go to the Job Bank

viewers where they may look for job openings in

areas of their interest or look generally at all

job openings available that day. When an appli

cant selects a job in which he is interested he

then goes to a interviewer who determines his

eligibility for the job in question, checks with

the Order Taking Unit to see if the job is still

open and whether the number of referrals requested

by the employer have already been made. An

applicant who is referred to a job is given a Job

Bank referral slip to deliver to the employer.

The employer indicates the action taken on the

referral and returns this slip to TDES.

When an employer telephones TDES in Memphis

seeking applicants for a job opening, a person in

the Order Taking Unit (who, although classified as

16a

an interviewer, does not necessarily have contact

with applicants) takes down all relevant informa

tion pertaining to the opening on a job order

form. That job order is transmitted daily by wire

to the TDES computer center in Nashville where the

information is transferred to microfilm cards and

returned to Memphis the next morning for use in

the Job Bank. The information available to

applicants contains all relevant data about the

job but the microfilm viewers do not reveal the

employer's name. (The employer's name and other

data are available, however, on the viewers

used by interviewers and counselors of TDES.)

Although the Memphis Office operates branch

offices and conducts activities related to the

primary function of job referral and placement,

most of the operation is now conducted at one

main location. In May of 1973, however, the

Commercial, Professional & Technical Division

moved from the main office to another location.

Applicants seeking clerical, professional or

technical jobs are now referred to that other

location nearby, which handles a higher percentage

of while [sic] applicants than the main office.

This CP&T office handles higher-paying and

17a

better quality positions such as clericals,

engineers, bookkeepers, etc. This separate

unit maintains its own applicant files and does

its own file searches, and all applicants seeking

employment in these occupational classifications

are referred to the separate CP&T office. The

vast majority of employees at the latter office

are white. The Memphis Office still operates a

separate "Domestic and Casual Labor" unit.

Casual, day, domestic, and farm applicants

are now handled in an annex at the main office

location. Most of the applicants handled in this

unit are for jobs of three days duration or less,

such as warehouse loading, yard work, and mis

cellaneous jobs of this type. The unit also

handles such full-time jobs as domestic help.

This unit is not, however, a part of the Job

Bank operation and job orders are taken directly

by the unit without coming from central control.

The procedures described as employed begin

ning in 1970 and up to the present are more

efficient and helpful to job applicants, including

blacks. There has been continued improvement

in service to black and minority group job appli

cants in the Memphis office of TDES since 1970.

The Job Bank system has increased the participa

18a -

tion of black applicants in job opportunities and

areas previously available, for the most part,

to white applicants.

State employment agencies, including TDES,

that receive federal assistance in the implemen

tation and operation of job opportunity programs

are not to refer appplicants to employers known to

be engaged in racially discriminatory employment

practices. Employer relations unit representa

tives of TDES have responsibility to deal with

employers and to counsel those who may be believed

or found to engage in racially discriminatory acts

or procedures, and they may initiate recommenda

tions to cease "doing business" with such em

ployers. Normally, however, an interviewer or

order taker within the TDES would initiate infor

mation or request for action relative to an

alleged discriminatory employer. Such an em

ployer's card may be marked for "control"-purposes

and excluded from use as being a racially discrimi

nating "suspect" employer. Normally, however, the

use of tests, even though not validated, would

not place an employer in such a category. There

is an area equal employment opportunity represen

tative (formerly called a minority group represen

19a -

tative) whose responsibility essentially is to

gain compliance with the 1964 Civil Rights Act as

amended, and to coordinate activities of TDES with

local race sensitive agencies.

In 1971, the percentage of minority race

persons of TDES was approximately the same as

that of the percentage of minority to the whole

number of State of Tennessee employees. The

Personnel Department of the State of Tennessee,

however, at this time had a lesser percentage

of black and minority employees. Under a new

State administration, however, after 1971 these

percentages improved as to incidence of black

employees, including those in supervisory posi

tions. The defendant department heads initiated

actions to improve utilization of black employees

prior to the filing of this suit. In 1971, the

percentage of black employees in the Memphis

Office of TDES was approximately twice that of the

State as a whole (approximately one-fourth),

although there were relatively few interviewers in

the main office. The majority of the traffic in

the Memphis Office then and now, however, is

black. There is still some opportunity for

discrimination by interviewers and others in

- 20a -

the Memphis office since 1970, but plaintiff has

failed to demonstrate by proof specific instances

of such discrimination. There still must be

judgments made of applicants' abilities, file

search suitabilities, and code ratings, but

no system can avoid the possibility of discrimina

tion.

In dealing under guidelines suggested by the

Department of Labor with suspected discriminatory

employers, TDES procedures causes them to be

placed "on control" or to be eliminated as

sources of employment pending investigation and

attendant circumstances. It was not the practice

of TDES to notify the local office of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission if discrimina

tory practices were suspected of a given employer,

nor did TDES refuse to serve employers who ad

ministered tests which might prove to have dis

parate effects on blacks. An area Equal Employ

ment Opportunity representative, a black, was

appointed after passage of Titles VI, VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 to serve as liason

with community agencies and to improve minority

group opportunities and representation.

21a -

According to plaintiff's data, by trial of

this cause, 34% of Memphis Area Office employees

were black, roughly equivalent to the percentage

of black adult population in the City. Some were

classified as managers, others as counselors,

interviewers, clerks, typists, ERR's, and "agents.1

The higher salaried positions generally, however,

reflected relatively fewer blacks, because 38% of

the whites had been hired before 1964 and only 13%

of the blacks had been hired before that date,

giving the blacks relatively less seniority and

experience. This was borne out by the data

indicating that the higher salaried blacks, for

the most part were hired before 1964, and the same

situation prevailed for whites. Significant

advancement was made by blacks as counselors and

3/managers m recent years.— Black employees do

fill most of the lower paying positions. Most of

the white interviewers had been hired prior to

1964, while most black interviewers were hired

after 1964.

3J For instance, 35% of counselor II positions

were filled by blacks; 50% of counselor III

positions, and 25% of counselor I positions.

- 22a -

The State of Tennessee follows a civil

service system in which classified civil service

job openings are filled (whether by new hires or

by promotions) in accordance with a classification

system established by the Department of Personnel.

See TCA §8-3001 et seq. Generally, an employment

certification list is maintained and State agen

cies hire from the top five eligibles, and in the

case of promotions, vacancies are filled from the

top three eligibles for promotion. Tests are

usually involved, or have been involved in many

classifications. In the case of the position of

interviewer at the Memphis Office of TDES,

for example, tests are involved and performance is

an important factor in selection. Validation

studies in connection with these tests were being

made at time of trial. The Department of Person

nel furnishes TDES the names of eligible as to the

interviewer (and other) classifications. TDES is

considered to be a total "civil service" agency

except as to non-skill, lower paying positions.

Prior experience is, of course, a factor in TDES

promotions, and Memphis Area Office appplicants

are given priority over those from other areas.

23a

The Department of Personnel has not identified the

race of persons on eligibility lists in accordance

with D.S. Civil Service Commission requirements.

Generally, according to plaintiff's counsel's

contentions, minority applicants, based on test

scoring, do not attain the top three or top five

• • 4 /positions

Blacks, according to 1970 census figures, in

Shelby County, Tennessee, comprised a substantial

majority of "poverty level" or less economic

family units, although they comprised only about a

third of the population, and they experienced more

than twice as much unemployment proportionately.

Some studies attribute the disproportion to

"institutionalized behavior" as contrasted to

specific discriminatory conduct in the Memphis

area in considering the heavy concentration of

blacks in relatively low-paying jobs. This is

part of a national problem with respect to urban

minority employment.

In 1966, the relative occupational position

of black males in the Memphis area in comparison

4/ See proposed finding #34, (plaintiff's).

- 24a -

to whites was approximately the same as in the

South as a whole, although there was a substantial

gap between the average income of black and white

males, and this gap continued into 1970. In 1969

there were 22,422 white referrals, 35,480 non

white job referrals by the Memphis Office of TDES

in response to 31,198 job "orders." There were

23,186 placements, of which 7,309 were white,

15,877 non-white. In 1972, there were 19,668

white referrals, 36,829 non-white, in response to

41,911 job orders, resulting in 20,084 placements,

of which 14,054 were non-white. Unquestionably

the TDES Office was an important source of jobs

for blacks in Memphis as well as in the United

States as a whole. In 1973,-^68% of referrals

were to blacks, and 58% of placements were to

blacks. There was, however, a difference in that

same period of about thirty cents an hour in the

average hourly rate of black and white males

in the jobs to which they were referred. There

was even a greater differential, over-all, between

5/ Over a ten month period analyzed by plain

tiff's expert, Dr. Joseph C. Ullman, a consultant

with the Department of Labor's Manpower Adminis

tration.

- 25a -

black and white females. The disparity, however,

between the races as to job referral differentials

decreased as educational levels increased.

References to Dr. Ullman's analysis of data on

behalf of plaintiff is made to a ten month 1972—

1973 period in which defendant TDES computerized

figures were made available to plaintiff. The

differences were determined by plaintiff's expert

to be statistically significant.

From the over-all 68% average of referrals to

black males during the period analyzed, there was

only a slight difference in the ratio referred to

so-called "higher paying industries" and to "low

wage, industries," but there was about a ten

percent variance from the norm in the case of

referrals of black females in respect to "high

pay" and "low pay" categor ies . This was due,

primarily, to the large number of black females,

largely uneducated, unskilled, and unexperienced,

who were referred in domestic and service posi

tions. There was not a signficant gap, however,

in average referral wage rates of black and white

females to "high-wage industries" during this

period studied. This was a contrast to the

26a -

significant differences in the other categories

mentioned as to both male and female referrals.

More blacks were referred, on a percentage basis,

to low-skill jobs than to high-skill jobs, based

on DOT codes used by the Department of Labor in

compiling its statistics. When skill and ex

perience were demonstrated to be job requisites or

desirable, the proportionate differences between

black and white referrals proved to be less

significant. Other than possible discrimination

involved, by the employer, or by some TDES em

ployee, Dr. Ullman thought a likely explanation

for the disparity to be based on more job ex

perience on the part of white applicants, and that

TDES "interviewers are referring whites with

experience in preference to blacks without ex

perience." His opinion was that a presently

racially neutral policy on the part of TDES,

particularly the Memphis office, in referring more

job experience whites than less experienced

blacks, has an effect of perpetuating past dis

crimination. He conceded, however, that substan

tially disportionate effects would be required on

the part of TDES to place the higher percentage

27a -

of uneducated or comparatively uneducated blacks,

unskilled as well as inexperienced, in comparison

to better educated (attaining a higher grade

level), more skilled and more job experienced

whites, particularly as to hard core unemployed.

For instance, defendant's expert, Dr. Bernard R.

Siskin, in studying the same ten month statistics,

concluded that "it is almost three times more

likely that a white applicant is high-skilled than

a black is high-skilled." He also concluded that

the data studied was misleading and inaccurate

because it did not relate to individual applicant

data or experience rather than referral data.

6 /Dr. Siskin' s— conclusions were m many

areas contrary to those of Dr. Ullman. For

example, he found that black females were being

disproportionately referred to permanent jobs,

in comparison to temporary jobs, than were white

females, whereas black males were being dispropor

tionately referred to temporary jobs, but this he

explained was due to black males being referred to

laborer jobs which they were seeking more than

were white males. He found that it took more than

6/ Dr. Siskin of Temple University has testified

also for plaintiffs in discrimination cases.

- 28a -

50% more referrals to place a black than a white

and concluded that this situation reflected upon

the statistical data relied upon by Oilman. After

adjustment, taking this factor into account, the

racial disparity in regard to referrals to high-

skill or low-skill jobs was reduced significantly,

particularly as to males. His conclusion was that

the TDES data showed that agency to be acting in a

"complete racially neutal manner," in Memphis, and

was, moreover, not inconsistent with some affirma

tive action indications.

In substance, Dr. Siskin found disparities

between the races due primarily to differences

in skills, education and other factors after

analyzing (the data. He found no evidence that

racial discrimination played any significant role

in practice or procedure during the 1972-1973

period studied in the Memphis office. Particu

larly as to those with high school education

or better, he found differences, if any, with

regard to referrals to be relatively unsubstantial

and of no practical significance with respect to

race. He found an over-all wage differential,

as adjusted, of approximately 18 cents but con

sidered this difference to be accounted for

29a -

by considerations of disparities in skills,

experience, and special education. Over-all,

public employment service, such as that of TDES,

handles only about five percent of total job

placement in the economy, but it is an important

employment factor to blacks.

Whites who apply at the Memphis Office of

TDES are almost twice as likely to have high skill

experience than blacks; 25% more, in proportion,

of white males have at least a high school educa

tion than black males; 30% more white females

have at least a high school education than black

females .—^Approximately 40% of blacks so apply

ing have less than a high school equivalent,

whereas only 10% of white females are in this

category, and only 15% of white males. In the

Memphis community at large approximately 37% of

black employees are categorized as laborers,

compared to less than 6% of white males. Approxi-

7] It is more than five times as likely that

black female applicants to the Memphis Office

will have a ninth grade education or less in

comparison to white females; three times as

likely black males will be so educationally

handicapped in contrast to white males. (16%

to 3% in case of females, 16.5% to 5% in case of

males).

- 30a

mately 75% of black employees were categorized as

laborers or "operatives" (56% of black females),

as compared to 27% white males (21% white females)

so categorized in 1969.

From these findings the court concludes that

the court does have jurisdiction of this cause,

including the class action allegations made by

plaintiff Shipp as to all defendants. The Memphis

Area Office of TDES is an "employment agency"

within the meaning of Title VII 42 U.S.C. §2000e

(b) and (c), and the other parties were appro

priately named in Rule 19 to effectuate complete

relief to the extent indicated. Charges under the

post Civil War Civil Rights Acts, 42 U.S.C. §1981

and 1983 and under the 14th Amendment may be

afforded separate relief. Johnson v. R.E.A., 43

U.S.L.W. 4623, ____ U.S. ____ (5-19-75). See

Long v. Ford Motor Co., 496 F.2d 500 (6th Cir.

1974).

There was no bad faith indicated by TDES with

regard to black employment opportunities following

a seasonable opportunity to comply with the

provisions of Title VII enacted in 1964. The

employment practices of TDES, and particularly the

Memphis Office, were facially neutral and non-dis-

criminatory until approximately 1970. In respect

31a -