Lawson v. Vera Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lawson v. Vera Brief of Appellants, 1995. ebba5cb6-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4a01ea35-42b9-47b5-8a4a-ba7b5d21aa44/lawson-v-vera-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

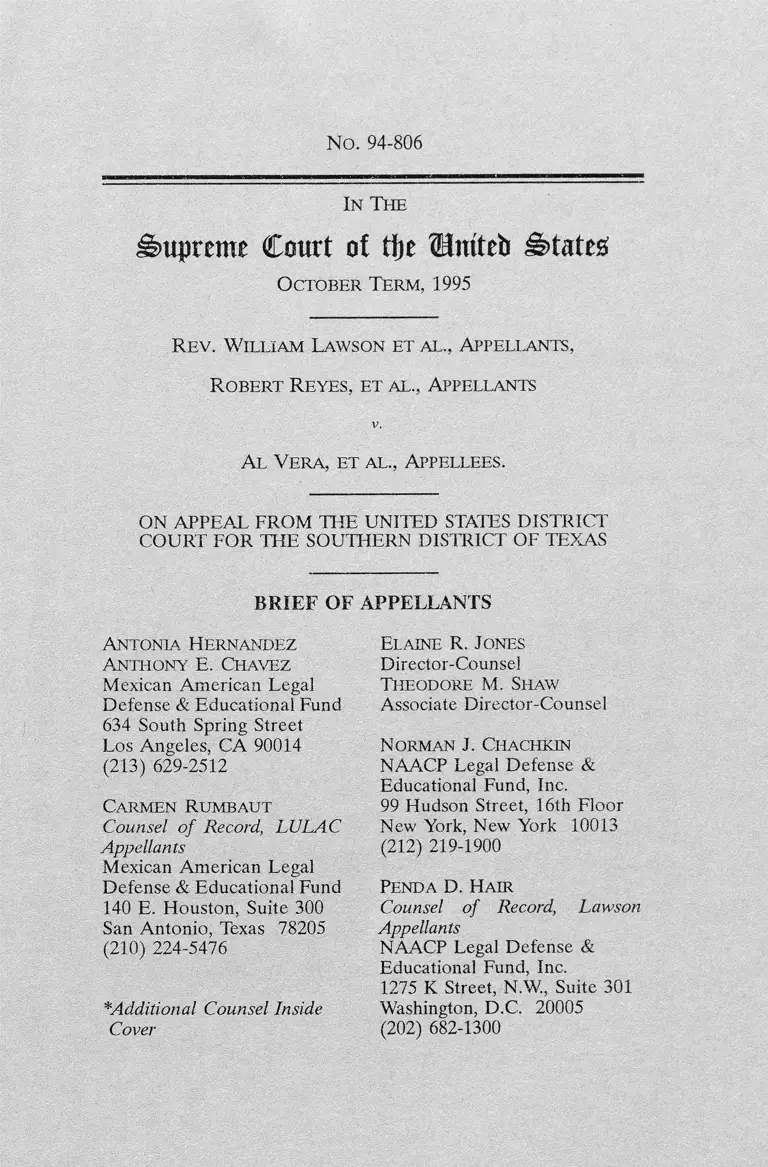

No. 94-806

In The

S u p rem e C ourt of tfte U ntteb i£>tateg

October Term, 1995

Rev . William Lawson et al., Appellants,

R obert Reyes, et al., Appellants

Al Vera , et al., Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Antonia Hernandez

Anthony E. Chavez

Mexican American Legal

Defense & Educational Fund

634 South Spring Street

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

Carmen Rumbaut

Counsel o f Record, LULAC

Appellants

Mexican American Legal

Defense & Educational Fund

140 E. Houston, Suite 300

San Antonio, Texas 78205

(210) 224-5476

*Additional Counsel Inside

Cover

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Associate Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Penda D. Hair

Counsel o f Record, Lawson

Appellants

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W., Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Charles Drayden

Drayden, Wyche & Wood,

L.L.P.

1360 Post Oak Blvd.

Suite 1650

Houston, Texas 77056

(713) 965-0120

Lawrence Boze

2208 Blodgett

Houston, TX 77004

(713) 520-0260

Kevin Wiggins

White, Hill, Sims & Wiggins

2500 Trammel Crow Center

2001 Ross Avenue

Dallas, Texas 75201

(214) 954-1700

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. W hether Texas’ Congressional Districts 18, 29 and 30

should have been sustained even before reaching the

issue of strict scrutiny because race did not

predominate in the construction of these districts,

where:

a. "ideally" compact versions of Districts 18, 29

and 30 were rejected for incumbent

protection and other non-racial reasons;

b. the versions of Districts 18, 29 and 30

adopted by the Texas Legislature were no

more irregular than majority-white districts;

and,

c. areas included within Districts 18, 29 and 30

share common interests other than race?

II. Whether Texas’ Congressional Districts 18, 29 and 30

are narrowly tailored to serve a compelling interest?

III. Whether plaintiffs who have proved no injury have

standing to challenge a State districting plan as a

"racial gerrymander"?

l

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

The State Appellants (No. 94-805) are Texas State

officials George W. Bush, Governor, Bob Bullock,

Lieutenant Governor, Pete Laney, Speaker of the House of

Representatives, Dan Morales, Attorney General, and

Antonio O. Garza, Jr., Secretary of State.

The Lawson Appellants (No. 94-806) are Rev.

William Lawson, Zollie Scales, Jr., Rev. Jew Don Boney,

Deloyd T. Parker, Dewan Perry, Rev. Caesar Clark, David

Jones, Fred Hofheinz and Judy Zimmerman.

The LULAC Appellants (No. 94-806) are Robert

Reyes, Angie Garcia, Robert Anguiano, Sr., Dalia Robles,

Nicolas Dominguez, Oscar T. Garcia, Ramiro Gamboa and

League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) of

Texas.

The United States is the Appellant in No. 94-988.

Appellees are A1 Vera, Edward Blum, Edward Chen,

Pauline Orcutt, Barbara L. Thomas and Kenneth Powers.

li

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions P resen ted ............................................... i

Parties to the Proceeding ....................................................... ii

Table of A u th o rities ...............................................................vii

Opinion B elo w ..................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions In v o lv ed ........... 1

Statement ................................. 1

Proceedings B e lo w .............................................................. 1

Facts ...................................................................................... 3

A. The Major Factors Shaping Texas’ 1991

Congressional Redistricting ........................ 3

1. Incumbent p ro tec tion ....................... 3

2. Potential liability under the Voting

Rights A c t .................................................. 5

3. State legislators’ ambitions . .................... 7

4. Other Factors...................................................8

B. The Interplay of These F acto rs...................... 8

C. The Character of the Resulting Districts . . 11

iii

D. Representation of District Constituencies . 15

Plaintiffs’ Claims ............................................................... 17

The District Court’s Ruling .............................................. 18

Summary of Argument . ........................ .......................... 19

Argument . . ...................................................................... 21

I. The 1991 Plan, Including Districts 18, 29

And 30, Should Have Been Sustained Without

Strict Scrutiny ........................................................ 21

A. Race Did Not Predominate Either In The

State Of Texas’ Decision To Create

Majority-Minority Districts Or In The

Ultimate Configuration Of Those

Districts. ....................................................... . 22

B. Districts 18, 29 And 30 Encompass

Communities That Have Actual Shared

Interests ............................. 26

C. The Final Configuration Of The Districts

Resulted From A Constitutionally Permitted

Political Gerrymander, Not From An

Improper Racial G errym ander................... 27

D. The Lower Court’s Decision To Subject

Districts 18, 29 And 30 To Strict Scrutiny

Is Based On Serious Errors Of L a w .......... 30

1. The District Court erred in rejecting

incumbent protection as a "traditional"

districting criterion .................................. 30

IV

2. The district court erred as a matter of

law in refusing to recognize the goal of

incumbent protection as a non-racial

influence on district shape...................... 33

3. The district court applied the wrong

test and erred in ignoring the irregular

shapes of Texas’ majority-white

Congressional districts............................. 36

4. The district court erred in finding a

"racial gerrymander" from a combination

of awareness of racial demography,

valid consideration of race in the

districting process and the existence

of correlations between districting

factors and r a c e ...................................... 38

II. Districts 18, 29 and 30 Each Satisfy

Strict S c ru tin y ......................................................... 45

A. Districts 18, 29 and 30 Are Supported By

A Compelling State In te re s t....................... 46

1. Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act . . . 47

2. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act . . . 48

a. "Reasonably compact" opportunity

districts ............................................. 48

b. Racially polarized voting and other

indicia of barriers to minority

political opportunity ........................ 49

v

B. Districts 18, 29 and 30 are Narrowly

Tailored .................................... ....................... 54

1. Districts 18, 29 and 30 meet this

Court’s requirements for narrow

ta ilo ring ....................... 54

2. The court below erred in interpreting

narrow tailoring to incorporate the

court’s preferred, "ideal" districting

criteria....................................... 56

a. The decision below forces the State

to discriminate against minority

communities of interest and minority

incumbents. . ................. ................ . 56

b. The decision below violates the

principle of federalism. . . . . . . . . . 58

III. The Plaintiffs Lack Standing .............................. 59

C onclusion............................................... 65

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena,

115 S. Ct. 2097, 2117 (1 9 9 5 )........................................... 45

African American Voting Rights Legal Defense

Fund, Inc. v. Villa, 54 F.3d 1345 (8th Cir. 1 9 9 5 ).......... 39

Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984).......................... 59, 60

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976) ...................... 47

Bums v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73 (1966) ........................ 58

Busbee v. Smith, 549 F. Supp. 494 (D.D.C. 1982),

aff’d, 459 U.S. 1166 (1 9 8 3 )........................................... 48

Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1 (1975) ...................... 32, 58

City o f Dallas v. United States,

482 F. Supp. 183 (D.D.C. 1979) .................................... 50

City o f Richmond v. Croson, 488 U.S. 469 (1 9 8 9 ) .......... 46

Davis v. Bandemer,

478 U.S. 109 (1986) .......................... .. . 28, 30, 38, 57, 61

DeWitt v. Wilson, 115 S. Ct. 2637 (1995),

affirming, 856 F. Supp. 1409

(E.D. Calif. 1994).................................... 23, 24, 25, 40, 48

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973).............. 30, 33

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ................... 15

vii

CASES PAGE

Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075 (1993) ___ . . . . . . . 57

Jeffers v. Clinton, 730 F. Supp. 196 (1989),

affd, 498 U.S. 1019 (1990) .............................................. 49

Johnson v. De Grandy,

114 S. Ct. 2647 (1994) . ................. ............. 47, 48, 49, 54

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1 9 8 3 )................... 32

Lujan v. Defenders o f Wildlife,

504 U.S. 555 (1992) ...................... ............................ 59, 60

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995) ............ . passim

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977).............. ........... 58

Monroe v. City ofWoodville, Miss, 819 F.2d 507

(5th Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 484 U.S. 1042 (1988) . . . 39

Personnel Administrator v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256 (1979) .......... .. ............ .............................. 35

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S. Ct. 2816 (1993) . . . . . . . . . . . passim

Terrazas v. Slagle, 821 F. Supp. 1162

(W.D. Tex. 1993) .................................. .. ............ .. 28

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1 9 8 6 )............ passim

United States v. Hays, 115 S.Ct. 2431 (1995)___ 21, 59, 60

United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987) . . . . . . . 54

Voinovich v. Quilter, 113 S.Ct. 1149 (1993) . . . . . . . 46, 48 '

viii

CASES PAGE

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976)........................ 48

Washington v. Seattle School District No. 1,

458 U.S. 457 (1982) ......................................................... 57

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973) ....... ....................... 32

Williams v. City o f Dallas, 734 F. Supp. 1317

(N.D. Tex. 1990)..................................................... 49, 50, 51

Wilson v. Eu, 4 Cal. Rptr. 2d 379 (1992) ............ 23, 24, 40

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978) .......................... 58

Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52 (1964) ........................ 45

Wygant v. Jackson Board o f Education,

476 U.S. 267 (1986) ............................................. 45, 46, 54

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS and STATUTES

U.S. Constitution Amendment XIV

(Equal Protection Clause) ........................................passim

2 U.S.C. § 2 c ...........................................................................54

28 U.S.C. § 1253 ............................... .. ................................1

Voting Rights Act of 1965,

42 U.S.C. §§ 1973, 1973c .........................................passim

OTHER AUTHOIRTY

Webster’s Third International Dictionary (1981) ........... 31

IX

OPINION BELOW

The August 17,1994 opinion below is reported at 861

F. Supp. 1304 and is reproduced at TX J.S. 5a-84a.1

JURISDICTION

Timely Notices of Appeal were filed by the Lawson

Appellants on October 3, 1994 and by the LULAC

Appellants on September 29, 1994 (amended on November

4, 1994), respectively. TX J.S. la, 4a. The Court has

jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment and §§ 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973, 1973c, are set out at

TX J.S. 2, 87a-88a.

STATEMENT

Proceedings Below

Appellees, six Republican Texas voters (including an

unsuccessful Republican candidate in the 1992 general

election in District 18) filed suit on January 26, 1994,

challenging at least 24 of Texas’ 30 Congressional districts.

See TX J.S. 9a & n.3. They claimed that Texas illegally used

race and ethnicity in constructing Congressional districts and

lThis brief uses the following abbreviations:

TX J.S. - Jurisdictional Statement and Appendix of State Appellants

J.A. - Joint Appendix

TR - Trial Transcript, volume:page

TX Ex. - State Defendants’ Trial Exhibit

Lawson Ex. - Lawson Defendant-Intervenors’ Trial Exhibit

LULAC Ex. - LULAC Defendant-Intervenors’ Trial Exhibit

U.S. Ex. - United States’ Trial Exhibit

PX - Plaintiffs’ Trial Exhibit

Dep. - Deposition

failed to follow what they alleged were "traditional"

districting principles. TX J.S. 10a.

The Lawson Appellants, six African-American and

three white voters residing in Districts 18 and 30; the

LULAC Appellants, the League of United Latin American

Citizens (LULAC) of Texas and seven Hispanic voters, one

of whom resides in District 29; and the United States, were

permitted to intervene as defendants. Id. at 11a.

The court below ruled that three districts — Texas’

only two African-American opportunity districts2 (Nos. 18

and 30) and one Hispanic opportunity district (No. 29) —

violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.3 The court upheld the constitutionality of 21

other challenged districts (including new District 28), of

which 18 are majority-white and three are majority-

Hispanic.4

2The terms "majority-minority district" and "opportunity district" are

used interchangeably, to refer to districts that give a single minority,

either African-American or Hispanic, an opportunity to elect a candidate

of its choice. All of the Hispanic opportunity districts in the 1991 plan

have a Hispanic majority in both population and voting-age population

(VAP). District 18 has African-American population of 50.9% and VAP

of 48.6%, while District 30 has African-American population of 50.0%

and VAP of 47.1%. J.A. 158, 160.

districts 29 and 30 were first created after the 1990 Census. District

18 had been a minority-opportunity district since 1971 and its boundaries

were modified after the 1990 Census.

4On September 20, 1994, the court entered an order, nunc pro tunc

to September 2, 1994, enjoining the use of the current districts for the

1996 elections. On December 29, 1994, this Court stayed the district

court’s injunction. On June 29, 1995, this Court noted probable

jurisdiction, thus leaving the stay in effect.

2

Facts

A. Major Factors Shaping Texas’ 1991

Congressional Redistricting

The State of Texas was apportioned three additional

Congressional seats as a result of population growth revealed

by the 1990 census, increasing its total to 30. The

Legislature decided to center the three new districts in three

of the four counties with the largest population growth,

Harris, Dallas and Bexar.5

The district court concluded, on the basis of largely

undisputed evidence, that four types of factors combined to

shape the districts at issue in this case.

1. Incumbent protection.

More than a year in advance, the Texas

Congressional Delegation began work with the "overriding

objective" of "incumbency protection," seeking "to influence

the Legislature to draw districts that would maximize their

chances for reelection," TX J.S. 23a, 24a. The court below

noted that the Legislature "openly acknowledged" this fact:

"The incumbents ‘have practically drawn their own districts.

Not practically, they have.’" Id. at 24a (quoting Senator

Johnson, Chair, Subcommittee on Congressional Districts).

Traditionally, protection of incumbents has prevailed

over compactness in Texas Congressional redistricting. See

TX J.S. 15a (post-1960 creation of additional, statewide at-

large seat, to maintain status of all incumbents; configuration

of district running from the Houston area through rural east

Texas into the southern ends of both Tarrant and Dallas

5Most of that growth was attributable to increases in Hispanic and

African-American population. TX J.S. 13a. Tarrant County, which is

adjacent to Dallas County, was the other top growth area, id., so the new

Dallas district reflected the growth in this region.

3

Counties to protect seat of "Tiger Teague;"6 post-1970

redistricting "notable at least in part because of the great

lengths to which the state legislature went to solicit the views

of incumbent congressmen"). The court below cited Ted

Lyon, a former member of the Texas House and Senate

involved in post-1980 and post-1990 redistricting:

"[C]ompactness is not a ‘traditional districting principle’ in

Texas. For the most part, the only traditional districting

principles that have ever operated here are that incumbents

are protected and each party grabs as much as it can." Id.

at 15a n.9.7

In the 1991 redistricting, new technology permitted

the Legislature to go further than previously "on a block-by-

block or neighborhood- or town-splitting level to corral

voters perceived as sympathetic to incumbents or to exclude

opponents of incumbents." Id. at 55a. As the court below

found, citing the construction of invalidated Districts 18 and

29:

[M]any incumbent protection boundaries sabotaged

traditional redistricting principles as they routinely

divided counties, cities, neighborhoods, and regions.

6One member of the Texas Legislature remarked during the 1967

floor debates "that if you were to drive down Interstate 45 from the

northern border of C.D. 6 in southern Dallas and Tarrant counties to the

southern border of the district in the northern suburbs of Harris County,

with all the doors opened, you’d kill most of the voters in the district.’"

J.A. 298, 302 (statement of former State Senator Mauzy).

’Regular shapes and respect for political subdivisions have a weak

history, at best, as districting goals in Texas. See TX J.S. 15a n.9.

Although the court below thought that prior plans were more compact

than the 1991 plan, the Legislature in prior years undisputably lacked the

technological capacity needed to draw districts as precisely as those

adopted in 1991. Many legislators stated without contradiction that

compactness has never been a strong State interest in Congressional

districting. E.g. J.A. 391 (former State Senator Lyon); id. at 303 (former

State Senator Mauzy).

4

For the sake o f maintaining or winning seats in the

House of Representatives, Congressmen or would be

Congressmen shed hostile groups and potential

opponents.. . . The Legislature obligingly carved out

districts of apparent supporters of incumbents, as

suggested by the incumbents, and then added

appendages to connect their residences to those

districts.

Id. at 55a-56a (emphasis added) (footnotes and citations

omitted). In addition, a substantial part of the districts’

irregularity was caused by the goal of putting incumbents’

residences into their districts and not pairing incumbents in

the same district. "[Ijncumbent residences repeatedly fall

just along district lines." Id. at 24a.& * 8

Significantly, incumbent protection was an overriding

factor in shaping majority-white as well as minority

opportunity districts. Many Texas Congressional districts

were "disfigured less to favor or disadvantage one race or

ethnic group than to promote the reelection of incumbents."

Id. at 9a (footnote omitted).9

2. Potential liability under the Voting Rights Act.

The Legislature was aware as it redistricted of its

vulnerability under § 2 of the Voting Rights Act if it

fragmented an African-American or Hispanic population

concentration that was "sufficiently large and geographically

compact"10 to constitute an effective majority in a single

member district. It was well known that two such large and

&See TX J.S. 24a-25a (describing a half dozen such instances).

“See Addendum to this Brief (maps showing highly irregular shape of

interwoven, majority-white Districts 6 (including parts of five counties)

and 12, in comparison to invalidated District 30 (entirely within Dallas

metroplex)).

10Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50 (1986).

5

geographically compact African-American populations

existed, in Harris County (Houston) and in Dallas County,

and that a sufficiently large and compact Hispanic

population existed in Houston. The fact that a compact,

majority-black district could be drawn in the Dallas area had

been well publicized at least since the early 1980’s, when the

African-American community was deliberately divided

between District 5 and District 24. Plaintiffs’ main lay

witness, Kent Grusendorf,11 a Republican member of the

House of Representatives, testified at trial that a compact,

viable African-American district was "absolutely" possible in

Dallas and that fairness required it. TR 1:99-101.12

In Harris County, District 18 had been represented

by an African American since the election of Barbara

Jordan. The Hispanic population had experienced

phenomenal growth and was sufficient to constitute the

majority in two Congressional districts. TX J.S. 13a. A

highly-publicized plan creating a new majority-Hispanic

district, while maintaining the opportunity of African

Americans to elect their candidate of choice in District 18,

was proposed by State Representative Roman Martinez at

the outset of the redistricting process.13

uPlaintiffs presented only two non-plaintiff witnesses at trial, Rep.

Grusendorf and their expert, Dr. Weber.

12Plaintiffs’ expert, Dr. Weber, testified that the Owens-Pate plan for

Dallas included a 45.6% African-American population district, J.A. 143,

which was "reasonably compact" and would give African Americans an

opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice in Dallas. TR 111:115.

See also TR 11:30-31, 127-131 (testimony of Dr. Weber).

13TX J.S. 36a-37a. Rep. Martinez’ plan did not split any precincts,

TX J.S. 39a, and it maintained the Democratic nature of District 25, thus

protecting white incumbent Mike Andrews, id. at 36a-37a. His plan

could have been even more compact if District 25 had not been drawn

to protect for incumbency. E.g. TR IV:41 (Democrats, including

Hispanics, were removed to District 25). The highly compact Owens -

6

State Exhibit 12, produced by Christopher Sharman,

the Legislature’s chief technician and map drawer, TX J.S.

26a, confirms what was obvious to the Legislature. Taking

no political, incumbency, geographic or factors other than

race and district shape into account, Mr. Sharman produced

an extremely compact version of District 18 that closely

parallels the population and African-American percentage of

existing District 18. Mr. Sharman testified that without

political and other influences, creation of a compact version

of District 18 was "fairly easy." TR IV:68. Similarly, Mr.

Sharman was able, when excluding incumbency and other

factors, to produce compact districts with minority

population comparable to that of the current Districts 29

and 30. Id. at 68-69; TX Ex. 12.

3. State legislators’ ambitions.

Closely related to incumbent protection is Texas’

tradition of tailoring new or vacant districts to be favorable

to aspiring members of the State Senate and House of

Representatives.14 In the 1991 plan, state legislators so

assisted included white Senator Green, African-American

Pate plan, see TX J.S. 49a, created districts with 53% African-American

population (Dist. 18) and a 52.9% Hispanic population (Dist. 28) in

Houston. J.A. 142. See also U.S. Ex. 1086, tape 2, at 19-20 (Texas

Republican Party’s studies indicated that a Hispanic opportunity district

"not a dragon or a dinosaur district with unreasonable contortions" could

"be created to serve a real community of interest . . . along with an

expanded existing Black Congressional district"). Dr. Weber testified that

a "reasonably compact" district with an African-American voting-age

majority was possible in the Harris County area in 1991. TR 111:113.

uSee TX Ex. 62 (chart listing examples). This tradition goes back at

least to 1971, when Congressional districts were drawn to promote the

election of then-Senators Charles Wilson and Barbara Jordan. U.S. Ex.

1071, at 10 (Deck of Dr. J. Morgan Kousser). See aho J.A. 394 (Edward

Martin).

7

Senator Johnson, Hispanic Senator Tejeda, and Hispanic

Representative Martinez.

4. Other factors.

Several other traditional factors affected district lines

and produced irregularities. The State achieved absolute

population equality, with each district having 566,217

residents, a feat that caused considerable irregularity.

Requests from communities to be in a particular district

were accommodated where possible. The placement of

industry, universities,15 airports, government installations

and other economic criteria was given great weight.16

B. The Interplay of These Factors

District 30. In Dallas, State Senator Eddie Bernice

Johnson intended to run for Congress from the new district.

She represented a compact, politically cohesive district in the

State Senate that was majority-minority. Senator Johnson

early in the process proposed creating a new district in

lsE.g., TR III: 182-183 (universities and factories).

16For example, the State intentionally placed NASA into three

different districts to enhance representation of this important state

interest. J.A. 249-50. See also id. at 249 (District 29 deliberately includes

major industries along Houston Ship Channel), 300 (location of

industries considered in 1967 redistricting). Other non-racial influences

include the tradition that Democrats would not seek affirmatively to

interfere with existing Republican seats; the desire of Democrats to

retain seats currently held by Democrats; the reluctance to redraw lines

in a manner that placed two incumbents in the same district; locations

of friends, supporters and family members of incumbents and aspirants;

and non-racial, idiosyncratic factors.

8

Dallas that overlapped substantially with her Senate district,

was compact, and did not split any precincts. However, as

found by the district court, her proposal "drew much

opposition from incumbents and was quickly abandoned."

TX J.S. 31a. See also id. at 49a.

The irregular contours of District 30 resulted from

accommodating the demands of incumbents Martin Frost

and John Bryant (both white) as well as other non-racial

interests. The western, irregular border of District 30 goes

out to Grand Prairie because Senator Johnson had

relatives17 in the City, as well as a political base that was

predominantly white. Congressman Frost also had strong

political ties to Grand Prairie and after a fierce battle, they

split the City in a compromise. See, e.g., TX J.S. 32a. The

portion of that City in District 30 is only 14.7% African

American. PX 34T. Also to the west, one large arm goes

out to Dallas-Fort Worth Airport, which all agreed was

included for strictly non-racial reasons.18 Irregularities in

Oak Cliff and in the eastern boundary resulted from

compromises with incumbents Frost and Brvant, TX J.S.

32a.

After Frost and Bryant won back territory on the east

and west of District 30, the District was forced further north,

because of the traditional one-person, one-vote requirement

of population equality among districts. But just north of the

predominantly African-American neighborhoods of South

Dallas are the affluent, highly Republican, Park Cities

neighborhoods, which both the incumbent and the residents

wanted to remain in Republican District 3. E.B. Johnson

17Plaintiffs’ expert testified that including the relatives of an African-

American incumbent is not a racial gerrymander, even if the relatives

also are black. TR 111:120.

wSee, e.g. TR 11:223-24, 111:116 (Plaintiffs’ expert concedes that

extension of District 30 to airport "didn’t have anything to do with race").

9

Dep. 130; U.S. Ex. 1038. District 30 accordingly was

configured around Park Cities (creating a huge incursion by

District 3 into the middle of District 30),19 and picked up a

large number of white residents,20 including a Jewish

community that was unhappy in District 3,21 two small

African-American communities, in Hamilton Park and

Plano, which shared many ties with South Dallas and whose

residents requested to be in District 30, and northern

corridor industry such as Texas Instruments to add to the

District’s economic stature.

Districts 18 and 29. The court below found that

factors other than race and ethnicity "influenced the

boundary drawing of the Harris County districts." TX J.S.

38a.22 The court noted that District 25, represented by white

incumbent Mike Andrews, "was to be kept intact and

Democratic," id. at 38a. A suggestion by Congressman Craig

Washington that District 18 be reconfigured based on the

shape of his former State legislative district "was

unacceptable ‘because it would have taken a large chunk out

of District 25,’" id.

Another non-racial factor "was the desire of Senator

19See Addendum to the Brief (map); J.A. 406 (map).

^The northern segment of District 30 is 24% African-American. See

J.A. 335 (weighted average for segments 3 and 4).

21Lawson Ex. 22 11 3; Lawson Ex. 25 HI 6-7.

“The district court cited the testimony of Dr. Richard Murray, a local

political scientist, that "various factors influenced the Legislature in

designing Districts 18 and 29: a clear commitment to improve the

representational opportunities for Hispanics; the personal ambitions of

certain members of the Harris County delegation; protection of

incumbents; party politics; class interests; preservation of the 18th as an

African-American majority seat; and keeping certain neighborhoods

together." TX J.S. 47a.

10

Gene Green23 to draw a Congressional district in which he

could run, namely one which included as much of his Senate

district as possible," id. State Representative Roman

Martinez, who aspired to run for Congress from the same

area, proposed a compact plan in which a new majority-

Hispanic district would overlap substantially with his House

District. Id. at 36a-37a. This plan was rejected because it

did not do enough to accommodate Senator Green’s

interests. The court below found that "the borders of

District 29 became increasingly distended as [Rep. Martinez]

and Senator Green fought to place their state constituents

within the new district." Id. at 66a; see also id. at 38a-39a.

It bears repeating that if population was taken out of

a proposed district to protect incumbents, or for other non-

racial reasons, new population had to be found to meet

population equality requirements; it is obvious that

incumbents and aspiring state legislators would want those

new voters to have characteristics as similar as possible to

those of the voters taken out of the district as initially

proposed.

C. The Character of the Resulting Districts

Although the shape of Congressional Districts 18, 29

and 30 is more irregular than alternatives earlier suggested

by minority legislators, the areas and voters included within

each of the districts as finally configured share significant

economic, social and political interests. To begin with, each

district is located within a single metropolitan area.

The core residential areas that comprise District 18,

in Houston, have remained unchanged since Barbara Jordan

was elected in 1971. Lawson Ex. 16 H 7. In shaping the

district after the 1990 census, the Legislature added

“ Senator, now Congressman, Green is white; Rep. Martinez is

Hispanic.

11

communities to which the children of existing residents of

the core areas had migrated. J.A. 261 (testimony of Paul

Colbert). Residents of the migration areas have ties, such

as church membership and Sunday worship, with the

downtown neighborhoods, and all residents in current

District 18 are "part of the same media markets, including

media directed toward African Americans." Lawson Ex. 13

H 17 (statement of Councilwoman Sheila Jackson Lee); see

also Lawson Ex. 12 H 9 (statement of Rev. William Lawson).

Non-minority neighborhoods traditionally in the District,

such as Montrose, which indicated a desire to remain in it,

were retained. See J.A. 397.

Local institutions affect the elected leaders’ ties to

the people and communities in District 18. For example,

one witness noted: "Texas Southern University (TSU), a

historically majority-black university with a substantial white

student population, is located in District 18. Our

Congressman, Craig Washington, our State Representative,

A1 Edwards, and our City Councilman, A1 Calloway, all went

to TSU. The late Congressman Mickey Leland also went to

TSU." Lawson Ex. 18 11 8 (statement of Deloyd T. Parker).

Congressional nominee Sheila Jackson Lee24 explained that

because District 18 is wholly within Harris County, "[tjhese

areas share the same City and County representatives" and

"[i]f a District 18 constituent were to bring a local problem

to my attention — whether that individual is black, white,

Hispanic, or Asian; whether that individual lives in the

north, south, east or west of the district — I would know

which local representative could best address that problem,

so that the representative and I could coordinate our efforts

to work together on the issue." Lawson Ex. 13 H 10.

Similarly, the residents of District 29 in Houston have

common demographic and economic characteristics. Because

24At the time of trial, Councilmember Lee was the Democratic

nominee in District 18.

12

it is the least wealthy of Texas’ Congressional districts, "there

is definitely a community of interest." J.A. 477 (Martinez

Dep.). The same Spanish language media serves the

community throughout District 29. J.A. 396 U 14. Both

Districts 18 and 29 provide for ease of transportation and

communication among their residents, as Dr. Paul Geisel, an

expert demographer, testified: "Both of these districts

are . . . historic political wards of [Houston]. . . . [Districts

18 and 29 are small as congressional districts. It is possible

to visit all parts of either district in any direction in less than

1 hour." J.A. 289. Dr. Richard Murray, a well-respected,

local political scientist, reported about Districts 18 and 29:

"Stable neighborhoods and communities of interest were

generally respected. . . . Stable innercity neighborhoods —

River Oaks, south Montrose, the East End, Third Ward,

Acres Home — were not divided." Lawson Ex. 26, at 17.25

The same characteristics are found in District 30 in

Dallas County. Other Texas Congressional districts that

include part of the Dallas metroplex also spread to rural

counties. District 30, however, is located totally within the

metropolitan area. Congresswoman Johnson testified about

the small African-American neighborhoods26 at the northern

“ Plaintiffs’ only expert witness testified: "I know Professor Murray

very well, and I respect him." TR V:75. Dr. Murray found:

The congressional district plan adopted by the Texas Legislature

created districts in Harris County [that] bring together people,

including minorities not well represented in the legislative

chambers even in the 1990’s, who share a number of

demographic and political behavioral characteristics."

Lawson Ex. 26, at 25. See also J.A. 395-96 111 11-12; Lawson Ex. 18 1 8.

“ Hamilton Park is the first subdivision that would sell lots to African

Americans on which to build new houses. Middle-income and upper-

income African Americans migrated from South Dallas first to Hamilton

Park, then to the McShan Road area and up the northern corridor to

Plano. Johnson Dep. 132-133.

13

end of District 30: "In terms of a community interest . . .

many of them are dentists and physicians who practice, have

offices in [South Dallas]. They go to church in that area.

They participate in social groups in the area. I live in

Southwest Dallas County and many of them are my personal

friends and social associates." Johnson Dep. 134. Residents

of both the northern and the southern parts of District 30

are members and active supporters of local organizations

such as the NAACP and Urban League. Id. at 142. Indeed,

both African-American and white communities in North

Dallas were included within District 30 because they did not

feel adequately represented in their prior, predominantly

Republican, Congressional districts. Johnson Dep. 132-133,

135; Lawson Ex. 22 H 3; Lawson Ex. 25 1111 6-7.

As with District 18 in Houston, migration patterns

were considered in determining areas to be included within

District 30. TX J.S. 28a-29a (citing PX 8B (transcript in

Terrazas v. Slagle)). In addition, communities of interests

reflected by support for regional, mass transportation were

considered. District 30 was designed in part based upon

voting pattern data from the local referenda on Dallas Area

Rapid Transit (DART) "to determine where there might be

more communities of interest, where there would be support

that would go beyond the color of the candidate." TX J.S.

34a (quoting Johnson Dep. 144). The DART light rail

system is not regularly shaped, yet, as explained by DART

Board member and former Texas House member Jesse

Oliver, "the DART light rail system appears to be the

skeleton of District 30 [and] DART bus routes appear to be

the veins and arteries of District 30." J.A. 402; see J.A. 406-

07 (DART maps).27

27As Mr. Oliver stated: "The close relationship between District 30

and the DART service area is a logical one. The light rail starter system

was designed to serve transit-dependent people; and those people are

usually low to moderate income workers, who most often are minorities.

District 30 includes this same community of people." J.A. 402 H 11.

14

D. Representation of District Constituencies

The court below made no finding that the

configuration of any of the three invalidated Congressional

districts had affected the adequacy of representation

afforded constituents, much less that there were any such

effects along racial lines. The evidence was to the contrary.

For example, white plaintiff Barbara Thomas was

"very, very favorably impressed" with nominee Sheila Jackson

Lee and expected that as a Congresswoman, Lee will reach

out to white voters and attempt to build racial bridges.

Thomas Dep. 74, 78. One white resident of District 18

described the responsiveness of Congressman Mickey Leland

and nominee Sheila Jackson Lee to all district residents. He

testified that whites in the district "feel comfortable with that

representation" and that there is widespread white support

for majority-minority districts such as District 18.28 Two

white District 30 residents described how their former

representatives had ignored them and how their

representation has improved since they had been placed in

District 30.29

Witnesses emphasized that these districts were not

segregated,30 but instead helped to overcome the effects of

“ Lawson Ex. 10 f 9 (statement of David Jones). Mr. Jones referred

to a recent survey conducted by Texas A&M University indicating that

six of ten whites supported majority-minority districts and only 23 percent

of whites were opposed. Id. 11 10.

^Lawson Ex. 22 11 3 (statement of Marc Stanley); Lawson Ex. 25 111!

6-7 (statement of Judith E. Zimmerman). See also Lawson Ex. 21 11

10(statement of Grady W. Smithey, Jr.).

“ ''Segregation" is an inappropriate description of the majority-

minority Districts at issue here. In Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339

(1960), the word "segregate" was used to describe allegations that "[t]he

essential inevitable effect of this redefinition of Tuskegee’s boundaries is

to remove from the city all save only four or five of its 400 voters, while

15

segregation.31 The only plaintiff from District 30, Pauline

not removing a single white voter or resident. The result of the Act is

to deprive the Negro petitioners discriminatorily of the benefits of

residence in Tuskegee, including inter alia, the right to vote in municipal

elections.1' Justice Frankfurter, known for his precision in the use of

language, said that if those allegations remained uncontradicted or

unqualified after trial, "the conclusion would be irresistible . . . that the

legislation is solely concerned with segregating . . . voters," id. at 341

(emphasis added).

Here, in contrast, District 18, 29 and 30 are the most integrated

districts in Texas’ 1991 districting plan, with all of the State’s other 27

districts having a higher percentage of a single race or ethnic group than

any of these three districts. In voting age population, District 18 is

47.1% black, 35.2% white and 13.7% Hispanic; District 29 is 55.4%

Hispanic, 9.8% black and 33.4% white; District 30 is 47.1% black, 36.1%

white and 15.1% Hispanic. As the results in District 29 indicate, there

is no bar to white candidates running or being elected. Texas has seven

Congressional districts that are more than 80% white. It is not accurate

to describe an integrated, minority opportunity district as "segregated,"

especially when heavily white districts are not labelled that way.

The court below also used the term "segregate" in an unusual

sense, to refer both to including minority voters into integrated minority

opportunity districts and to the placement of other minority voters into

majority-white districts. E.g. TX J.S. 68a. Plaintiffs’ expert was similarly

expansive in his definition of segregation. Dr. Weber first stated that

District 30 was not "a strong indication of segregation," because many

African Americans in the close vicinity were excluded. TR 111:110. He

later changed his testimony and said that District 30 was segregated, but

he was unable to say whether blacks were segregated into (or out of) the

District and he testified that whites were segregated into the District.

TR 111:139.

31White resident Judith Zimmerman explained: "Far from segregating

voters, the creation of a majority-minority district in Dallas has provided

an opportunity for a long overdue joining of historically divided forces.

Dallas is extremely polarized along racial lines, and this district is a

wonderful tool to help us pull together." Lawson Ex. 25 U 7. Dallas

businessman Albert Black stated: "I grew up in a segregated

neighborhood.. . . I do not understand how anyone could think a district

that brings together an African-American businessman from South Dallas

16

Orcutt, described the district forcefully: "It is integrated. Of

course it is, and you know it." Orcutt Dep. 110-11 (emphasis

added)."

Plaintiffs’ Claims

The nature of the claims asserted by plaintiffs in this

case are fundamentally different from other post-Shaw v.

Reno lawsuits, such as those involving Georgia and

Louisiana. Plaintiffs in this case do not seek a remedy that

will make these three majority-minority districts majority

white. Plaintiffs here do not contend that majority-non

white districts would not exist in Dallas or Harris County

except as a result of race-conscious redistricting. To the

contrary, plaintiffs readily conceded that what they regard as

"color-blind" redistricting would result in African-American

opportunity districts in both counties, and in a

predominantly Hispanic district in Harris County. Plaintiffs’

central trial court exhibit was their alternative districting

plan, deliberately drawn by plaintiffs’ expert without

consideration of race. Even under such a plan, plaintiffs

acknowledged that Districts 18, 29 and 30 would be majority-

non-white. This case thus presents the circumstance

described in Shaw, 113 S. Ct. at 2828, in which recognition

of existing communities would result in non-white districts.

The gravamen of plaintiffs’ claim concerns not

whether Districts 18, 29 and 30 should be majority-non-white,

but only what the particular contours of these districts

should be. Plaintiffs contend that under a race-neutral

districting process, the minority population should actually

have been higher in District 18 and about the same in

District 30. Only in District 29, which is currently

represented by a white incumbent, do plaintiffs advocate a

(like me) and an Anglo businessman from North Dallas (like Jerry

Johnson) to further economic development in the entire Dallas area

could be considered segregative." Lawson Ex. 1, at 16.

17

substantial increase in the proportion of whites.32

The District Court’s Ruling

The court below invalidated Districts 18, 29 and 30,

while upholding the constitutionality of 18 majority-white

and three majority-Hispanic districts,33 It subjected Districts

18, 29 and 30 to "strict scrutiny" because it said that they

were "racial gerrymanderjs]," TX J.S. 69a, defined as

districts intentionally created to be majority-minority, which

did not comport with "traditional" districting criteria, which

the court held must be "objective" and "ideal." Id. The

court specifically excluded protection of incumbents from

among "traditional districting" factors, because it is not an

“ Plaintiffs advocated combined-minority districts, proposing to put

more Hispanics into the African-American opportunity districts, and

more African-Americans into the Hispanic districts, a legal argument

discussed in note 80, below. The following chart shows the white and

minority population of Districts 18, 29 and 30 in the current plan and in

plaintiffs’ proposed alternative plan:

Black and Hispanic White

District 18

Current Plan 370,913

Plaintiffs’ Plan 411,915

District 29

State’s Plan 397,459

Plaintiffs’ Plan 311,096

District 30

State’s Plan 375,233

Plaintiffs’ Plan 364,467

(65.5%) 177,036 (31.3%)

(72.7%) 142,668 (25.2%)

(70.2%) 157,461 (31.4%)

(54.9%) 233,660 (41.3%)

(66.3%) 177,661 (31.4%)

(64.4%) 191,519 (33.8%)

The net overall effect of plaintiffs’ plan for these three districts of more

than 1.5 million residents is to increase white population by 55,689,

mostly in District 29, which so far has elected the candidate of choice of

white, and not Hispanic, voters, TR 11:18, J.A. 181 H 38.

“ Plaintiffs dropped their challenge to the remaining six districts,

including three majority-Hispanic districts.

18

"ideal" criterion, id. at 56a & n.43, and because "many of

the voters being fought over [by the incumbents] were

African American," id. at 64a.

Applying strict scrutiny, the court did not address

whether Texas had a compelling justification for creating

minority opportunity districts in the Houston and Dallas

areas because it concluded that the districts were not

"narrowly tailored." Id. at 69a-74a. The court held that in

creating majority-minority districts, the State must maximize

regularity of district shape,34 even though no such rule exists

for majority-white districts. The court found "dispositive"

the "fact that alternative plans for Districts 18, 29 and 30

were all much more geographically and otherwise logical," id.

at 73a.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S. Ct. 2816 (1993), and Miller v.

Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995), hold that when "race

predominates in the redistricting process," id. at 2488, a

plaintiff who has standing may require a State to justify its

districting plan by demonstrating that there was a compelling

State interest for taking race into account and that the plan

was narrowly tailored to achieve the compelling goal. On

the other hand, these cases reaffirm that, absent proof that

racial considerations predominated the districting process,

there is no colorable claim of a Fourteenth Amendment

violation even though a particular electoral district has a

majority-minority population. See Miller, 115 S. Ct. at 2490.

The factual findings below — if not the lower court’s

^"Because a Shaw claim embraces the district’s appearance as well as

its racial construction, narrow tailoring must take both these elements

into account. That is, to be narrowly tailored, a district must have the

least possible amount o f irregularity in shape, making allowances for

traditional districting criteria." TX J.S. 72a (footnote omitted and

emphasis added).

19

sweeping characterizations of the case -- and abundant

evidence in the record demonstrate that race was not "the

predominant factor motivating the legislature’s decision to

place a significant number of voters within or without"

Districts 18, 29 and 30. Miller, 115 S. Ct. at 2481.

Differences between the districts as enacted and those which

plaintiffs conceded would be appropriate, see TX J.S. 48a,

were attributable to reasons that have nothing to do with

racial motive. Because this case involves the interplay of

numerous political factors (primarily Texas’ tradition of

partisanship and incumbent protection) in the districting

process, and the Legislature’s simultaneous awareness of the

State’s racial demography, of its obligations under § 5 of the

Voting Rights Act, and of the need to avoid fragmentation

of concentrations of minority voters that would subject it to

potential liability under § 2 of the Act, the court below erred

in subjecting the challenged districts to "strict scrutiny" as

though race predominated.

The Court below also erred in its belief that the only

redistricting principles which could be considered were those

listed in Shaw, 113 S. Ct. at 2827. It specifically rejected

incumbent protection, TX J.S. 56a, as a traditional

redistricting criterion as well as other non-racial

considerations that actually influenced the 1991 Texas

redistricting. Moreover, the three districts invalidated

below have contiguity in the same way as other challenged

districts found legal by the trial court, and they likewise

reflect as much respect for political subdivisions as those

other districts.

Even if the Court were to determine that "strict

scrutiny" is the appropriate analytic standard, the judgment

below must still be reversed. The State had an extremely

strong basis in evidence for concluding that a compelling

interest supported the creation of these minority opportunity

districts in light of the population concentrations, polarized

voting, the history of discrimination and, with respect to

20

District 18, the requirement of non-retrogression. The court

below erred in holding that a majority-minority district "must

have the least possible amount of irregularity of shape,

making allowances for traditional districting criteria," TX J.S.

72a, which did not include incumbency protection. This is

a clear misreading of this Court’s language in Shaw stating

that there would be a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment if "a state concentrated dispersed minority

population in a single district by disregarding traditional

principles such as compactness, contiguity, and respect for

political subdivisions," 113 S. Ct. at 2827. There is nothing

in the Shaw opinion which says or indicates that the three

principles mentioned are exclusive. And the fact that "Shaw

nowhere refers to incumbent protection as a traditional

districting criterion," TX J.S. 56a, does not mean that a court

in a democratic society can shut its eyes to such political

reality.

Plaintiffs’ complaint should have been dismissed

because they failed to introduce evidence sufficient to

demonstrate their standing.35 Although they are residents of

Districts 18, 29 and 30, none of the plaintiffs presented

evidence that they suffered the harms discussed in Shaw, 113

S. Ct. at 2826.

ARGUMENT

I . The 1991 Plan, Including Districts 18, 29 And 30,

Should Have Been Sustained Without Strict

Scrutiny

This is not a case like Miller v. Johnson, in which a

legislature enacted several redistricting plans based on

multiple criteria — each of which was criticized for not

including enough minority districts -- and thereafter adopted

a plan in which all factors "that could realistically be

35See United States v. Hays, 115 S. Ct. 2431, 2435 (1995)(dismissal

proper if evidence sufficient to support standing not adduced at trial).

21

subordinated to racial tinkering in fact suffered that fate,"

115 S. Ct. at 2475. Here, the Legislature started with an

undisputed awareness of plans that would produce compact,

contiguous, minority-opportunity Congressional districts in

urban areas where large concentrations of minority voters

resided. The legislature ultimately adopted a plan that

included minority opportunity districts in those metropolitan

areas, but the districts’ shape -- while remaining contiguous,

having as much respect for political subdivisions as others

created under the plan, and including equal population —

became somewhat less regular and compact solely as a result

of complex political compromising designed to protect

incumbents, achieve partisan advantage and accomplish

other non-racial goals.

Because of this very different fact pattern, the

prerequisite determination requiring the application of "strict

scrutiny" announced in Miller: that "race predom inate^] in

the redistricting process," 115 S. Ct. at 2488, could not be

justifiably made in this case; and for this reason, the court

below should have sustained the legislative districts without

undertaking a "strict scrutiny" analysis.

A. Race Did Not Predominate Either In The

State Of Texas’ Decision To Create Majority-

Minority Districts Or In The Ultimate

Configuration Of Those Districts.

Miller held that the predominance o f race in the

districting process, not district shape, is the touchstone for

application of "strict scrutiny." 115 S. Ct. at 2490.

To make this showing ["that race was the

predominant factor motivating the legislature’s

decision to place a significant number of voters

within or without a particular district"], a plaintiff

must prove that the legislature subordinated

traditional race-neutral districting principles,

including but not limited to compactness, contiguity,

22

respect for political subdivisions or communities

defined by actual shared interests, to racial

considerations.

115 S. Ct. at 2481. The Court also recognized: "[A] State

is free to recognize communities that have a particular racial

makeup, provided its action is directed toward some

common thread of relevant interests. ‘[W]hen members of

a racial group live together in one community, a

reapportionment plan that concentrates members of the

group in one district and excludes them from others may

reflect wholly legitimate purposes.’" Id. at 2490 (quoting

Shaw, 113 S. Ct. 2816, 2826).36

Further insight into the applicable standards is

provided by the Court’s action on the same day that Miller

was announced, summarily affirming the lower federal court

ruling that upheld California’s Congressional and State

legislative districting plans, DeWitt v. Wilson, 115 S. Ct. 2637

(1995). The creation of majority-minority districts was a

strong motivating factor in the DeWitt districting plan, which

was proposed by a panel of Masters and adopted by the

California Supreme Court. See Wilson v. Eu, 4 Cal. Rptr. 2d

379 (1992).37 As found by the Supreme Court of California,

36Miller directed courts "to exercise extraordinary caution" and

recognized "the intrusive potential of judicial intervention into the

legislative realm." 115 S. Ct. at 2488. Even to invoke strict scrutiny,

plaintiffs must show that race "predominated" in the districting process

and other considerations were "subordinated," id. at 2488. Justice

O’Connor’s concurring opinion explained: "[t]he threshold standard the

Court adopts . . . [is] a demanding one" and "[application of the Court’s

standard does not throw into doubt the vast majority of the Nation’s 435

Congressional districts," id. at 2497.

37The Masters "devoted intense efforts to comply with the federal

Voting Rights Act." 4 Cal. Rptr. 2d at 383. They explicitly gave "federal

Voting Rights Act requirements . . . the highest possible consideration,"

id. at 397. Because the Masters had no knowledge of whether the

second and third preconditions of Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 50

23

the Masters engaged in "successful efforts to maximize the

actual and potential voting strength of all geographically

compact minority groups of significant voting age

population," id. at 393 (emphasis added). Despite the

Masters’ deliberate creation of minority opportunity districts

in all areas of the State where the minority population was

sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a

majority in a single-member district, the three-judge court

found that strict scrutiny was not required because "the

Masters’ Report sought to balance the many traditional

redistricting principles, including the requirements o f the

Voting Rights Act," 856 F. Supp. 1409, 1413 (E.D. Calif.

1992) (emphasis added).38

When these principles are applied to the facts found

by the district court, it is clear that race was not "the

predominant" motive within the meaning of Miller and,

hence, that strict scrutiny of the Texas districting plan was

not required. Like the Masters in DeWitt, Texas created

majority-Hispanic or majority-African-American districts only

where either the Hispanic or African-American population

was sufficiently large and compact to satisfy the first

(1986), were satisfied in any regions of California, they chose to minimize

the risk of a successful § 2 claim by creating a majority-minority districts

wherever the first Gingles prong was met. 4 Cal. Rptr. 2d 379, 383, 397,

399 (Masters did not have evidence of voting patterns and thus chose to

"draw boundaries that will withstand section 2 challenges under any

foreseeable combination of factual circumstances and legal rulings.").

Indeed, the Masters went further and where a compact minority

population was not large enough to constitute a majority in a district, the

panel nonetheless kept the minority population together in an effort to

promote minority influence. Id. at 383-384.

38Although the court alternatively found that the plan would survive

strict scrutiny, 856 F. Supp. at 1414, there was no evidence of racially

polarized voting, thus suggesting that this Court’s summary affirmance

was based on the conclusion that strict scrutiny was not required.

24

precondition of Gingles.39 The Legislature decided to make

Districts 18, 29 and 30 majority-minority only after it was

clear that such majority-minority districts could be created

in conformity with compactness and other "ideal" criteria.

Compactness was not subordinated to race or ethnicity in

determining the number of majority-minority districts. The

State did not maximize the number of majority-minority

districts.40 In fact, it instead rejected proposals that would

have created additional minority opportunity districts.41

The Masters in DeWitt identified reasonably compact

majority-minority districts and then built the rest of the

State’s plan around those districts. If Texas had adopted the

idealized, most compact versions of Districts 18, 29 and 30,

strict scrutiny would not be triggered. Instead of rigidly

adopting and building around the idealized versions, Texas

in the final borders of its minority opportunity districts

accommodated non-racial goals, such as incumbent

protection, State legislator aspirations, placement of non

population areas like airports and industry, placement of

incumbents’ residents, funding sources and friends, and

requests from voters of all race and ethnic groups and

39478 U.S. at 50. The Legislature was thoroughly advised about the

standards applied under § 2 of the Voting Rights Act through the "gray

books" prepared by and presentations given by knowledgeable Texas

Legislative Counsel attorneys. See TX J.S. 17a.

i0E.g., TR 111:21 (plaintiffs’ expert, Dr. Weber, testified: "Texas 1991

redistricting plan is not designed to maximize black voting strength").

41The decisive role of compactness in the decisions when to create

majority-minority districts and the absence of a "race for its own sake"

motive is demonstrated by the State’s rejection of proposals for

additional majority-minority districts. The Legislature rejected proposals

for majority-minority districts that would have joined together dispersed

minority populations with no apparent communities of interest. For

example, State Representative Jerald Larry proposed a third majority-

African-American district that would have traversed parts of 15 counties.

J.A. 305-06; Lawson Ex. 11 H 6. See also J.A. 253, 397.

25

religions. Such accomodations are characteristic of the

democratic society in which we live.

The evidence is overwhelming that the predominant,

overriding motive in moving from regularly shaped to

irregularly shaped versions of the opportunity districts was

not race, but incumbent protection. As plaintiffs’ main lay

witness, Representative Grusendorf, conceded, "the odd

configuration of District 30 was the result of protecting Frost

and Bryant." TX J.S. 32a.

Adjusting the borders of a compact African-American

or Hispanic district to better serve non-racial goals does not

convert an appropriate and "wholly legitimate" consideration

of race, Miller, 115 S. Ct. at 2490, 2500 (quoting Shaw, 113

S. Ct. at 2826), into "the predominant" use of race to

determine the ultimate shape of the district. Rather than

increasing the degree of racial motive, Texas’ choice of

irregular over regularly shaped versions of the minority

opportunity districts decreased the role of race and ethnicity,

by bringing additional influences into the decision.

B. Districts 18, 29 And 30 Encompass

Communities That Have Actual Shared

Interests

In describing the characteristics of districting plans

that need not be tested under a strict scrutiny standard, the

Court in Miller distinguished legislative recognition of

"communities that have a particular racial makeup [as well

as] . . . some common thread of relevant interests" from a

legislative assumption that persons of the same race will

prefer the same candidates at the polls, id. at 2490. The

extensive record in this case amply demonstrates that Texas

Districts 18, 29 and 30 all bring together "members of a

racial group [who] live together in one community," id., and

who have deep, common bonds.

The extensive evidence of voting patterns presented

by experts for both the plaintiffs and the State leaves no

26

doubt that the State was not relying on the unproven

assumption of political cohesion among African Americans

in Houston and Dallas and among Hispanics in Houston.

The experts agreed and the evidence was overwhelming that

African Americans in the Houston area in fact support the

same political candidates, that African Americans in the

Dallas area in fact vote cohesively as a group and that

Hispanics in the Houston area in fact vote cohesively with

each other, but not with African Americans. (This data is

discussed in more detail in Point II. A.2.b., below.) Because,

as described above (see supra pp. 11-14), these districts were

designed to recognize known communities of common

interests, and were not based on stereotypes, they are not

subject to strict scrutiny.

C. The Final Configuration Of The Districts

Resulted From A Constitutionally Permitted

Political Gerrymander, Not From An

Improper Racial Gerrymander

The essence of this case is political "gerrymandering,"

not racial "gerrymandering." The decision to protect all

sitting incumbents and to make the three new districts

Democratic had strong partisan implications. In a State

where roughly half the votes go to Republicans, the 1991

districting plan designed 73% (22 of 30) of the

Congressional districts to elect Democrats.42 This feat

42J.A. 346. See also U.S. Ex. 1000 (partisan index for Texas 1991

Congressional districts). The Democratic districts had majorities of

Democratic voters of at least 54.8%, while the Republican districts had

Republican majorities of at least 60.6%. Jd. One of the districts (No.

23) drawn with a Democratic majority in 1991 elected a Republican in

1992, probably because the incumbent was under investigation and

subsequently was indicted. The Republicans captured additional seats in

1994, but the 1994 losses were probably facilitated by the partisan

gerrymander, i.e., because the Legislature had spread Democratic voters

thinly in the effort to maximize the number of Democratic-controlled

districts, small shifts in voter choice toward the Republican direction

27

naturally required creative line drawing, but the effort was

a far-flung search for Democrats, not minorities.

The fact that Texas had engaged in a political, and

not racial, gerrymander was well known at the time. A

Bandemer-type43 lawsuit was filed by Republicans even

before the final plan was adopted.44 Republicans (except

incumbents happy with their high Republican percentages)

uniformly denounced the plan as D em ocratic

gerrymandering.45 No one claimed racial gerrymandering in

favor of African-American or Hispanic voters. Instead, the

opposite claim was made, that African-American and

Hispanic voters were disadvantaged in the quest to protect

all Democratic incumbents (most of whom happened to be

white).46

The transformation of Rep. Grusendorf, plaintiffs’

main trial witness, is illustrative. In 1991, Rep. Grusendorf

found the district lines "very logical and rational, . . .

dissecting communities very creatively in order to pack

Republicans and maximize Democratic representation." He

stated: "This plan was drawn with only one thing in mind,

and that is to protect Democratic incumbents, p e r i o d J.A.

376, 380 (Texas House Floor Debate, Aug. 21, 1991)

(emphasis added). Only after claims of partisan

gerrymandering lost in federal court47 did Rep. Grusendorf

resulted in the loss of seats.

i3Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986).

i4See Terrazas v. Slagle, 821 F. Supp. 1162, 1172 (W.D. Tex. 1993).

45E.g., J.A. 346, 351.

4<sTX J.S. 18a; U.S. Ex. 1005 (Republican claims of minority vote

dilution).

A1Terrazas, supra note 44.

28

discover the racial gerrymandering assertion, while still

complaining more about the partisan nature of the plan.48

It is no mere coincidence that all plaintiffs in this

case are Republicans.49 Plaintiffs presented at trial a plan

that kept the same number of majority-minority districts, but

dramatically altered the Democrat-Republican balance, from

22/8 to 15/15. TR IV:175-177. Plaintiffs’ expert admitted

that plaintiffs’ alternative plan sought "to provide a fairer

distribution of the seats based upon what we know about

partisan divisions in the State." TR V:24 (emphasis added).

With large, multi-ethnic, minority populations, it was

inevitable that minority voters, like all other voters, would

get caught up in the partisan engineering. The State’s

constitutionally legitimate effort not to fragment large,

compact minority populations was carried out in the

overarching context of its political gerrymander, with the

result that the boundaries of both minority and non-minority

districts, not only in Houston and Dallas, but throughout the

State, were made more irregular.

The irregularity was exacerbated where the State was

inserting new Democratic districts into metropolitan areas

with a "shortfall" of Democratic voters.50 But majority-

minority districts were treated no differently than majority-

white districts in the distortion of their shapes to produce

Democratic majorities in all Democratic districts.

48TR 1:99 ("the problem in congressional districting was not in the

Black district, but . . . the feeding frenzy of white Democrats"), 100-101

("fairness" and Voting Rights Act "required majority-minority districts

here"), 116 (Congressman Frost needed "Black voters to get re-elected"

"[bjecause they vote Democratic").

™See J.A. 390 H11 16, 17.

50See U.S. Ex. 1041 ("there just aren’t alot of spare Democratic voters

in and around Dallas").

29

Another way minority voters were caught up in the

partisan gerrymandering is the happenstance that in Texas

African-American, and to a lesser extent Hispanic, voters are

Democrats. In the quest to find Democrats, African

Americans and Hispanics were desirable, but so were white

Democrats, as demonstrated by the intense fight between

Eddie Bernice Johnson and Martin Frost over white voters

in Grand Prairie. Such consciousness of race and ethnicity

in the quest for Democrats is not constitutionally suspect, as

discussed in Point D.2., below. Unless the Court concludes

that Davis v, Bandemer,51 should be overruled, a result that

appellants do not advocate, there is no constitutional basis

for new, anti-partisan gerrymandering rules, applicable only

to majority-minority districts.

D. The Lower Court’s Decision To Subject

Districts 18, 29 And 30 To Strict Scrutiny Is

Based On Serious Errors Of Law

1. The District Court erred in rejecting incumbent

protection as a "traditional" districting criterion.

Miller and DeWitt establish that strict scrutiny applies

only when race was "the predominant" motive for a

districting plan and "race for its own sake . . . was the

legislature’s dominant and controlling rationale." 115 S. Ct.

at 2488, 2486. It follows that where majority-minority

districts can be created without displacing the State’s other

districting criteria, as in DeWitt, race is not "predominant."

It also follows that where any conflicts between the goal of

creating majority-minority districts and other districting

51See also Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735, 752, n.18 (1973)

(partisan gerrymandering does not constitute a Fourteenth Amendment

violation, even when "the shapes of the districts would not have been so

‘indecent’ had the Board not attempted to “wiggle and joggle’ border

lines to pockets of each party’s strength").

30

objectives resulted in compromises, those other districting

factors were not "subordinated," nor was race "the dominant

and controlling" factor, id.

The centrality of incumbent protection, as described

in the district court’s opinion, makes clear that race and

ethnicity could not have been, unless one misuses the

adjective, the "predominant"52 factor motivating the

Legislature’s 1991 action. The district court’s opinion

describes numerous instances in which the goal of creating

majority-minority districts conflicted with the goal of

incumbent protection, and the minority opportunity goal did

not predominate.

For example, although the district court characterized

Senator Johnson as motivated solely by a desire to create a

majority-African-American district, the court recognized that

the plan she initially proposed "drew much opposition from

incumbents and was quickly abandoned." TX J.S. 31a n.22.

Rather than constituting evidence that the Legislature’s final

plan for District 30 is an unconstitutional racial

gerrymander, this finding is fatal to the claim that race and

ethnicity predominated. In contrast to Senator Johnson’s

proposal, the State’s plan came about only after intense

political battles were fought, block by block, voter by voter,

and the interests of minority voters were compromised to

accommodate incumbent Congressmen.53

The district court did not deny that incumbent

protection predominated, but instead reasoned: "Shaw

nowhere refers to incumbent protection as a traditional

districting criterion." TX J.S. 56a. Excising incumbent

52The definition of predominant is: "holding an ascendancy" or

"having superior strength, influence, authority or position." Webster’s

Third New International Dictionary 1786 (1981).

S3See J.A. 388 (Senator Johnson had to accommodate incumbents to

get plan passed by Legislature).

31

protection simply because it is not explicitly listed in Shaw

is an error of law. Miller indicates that "traditional race-

neutral districting principles . . . includ[e] but [are] not

limited to" compactness and other factors on the illustrative