New York.-- Thurgood Marshall today served notice that there will be no letup…

Press Release

January 3, 1958

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. New York.-- Thurgood Marshall today served notice that there will be no letup…, 1958. bb172b6f-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4a35075b-c0c6-423a-a4e7-65361eaac591/new-york-thurgood-marshall-today-served-notice-that-there-will-be-no-letup. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

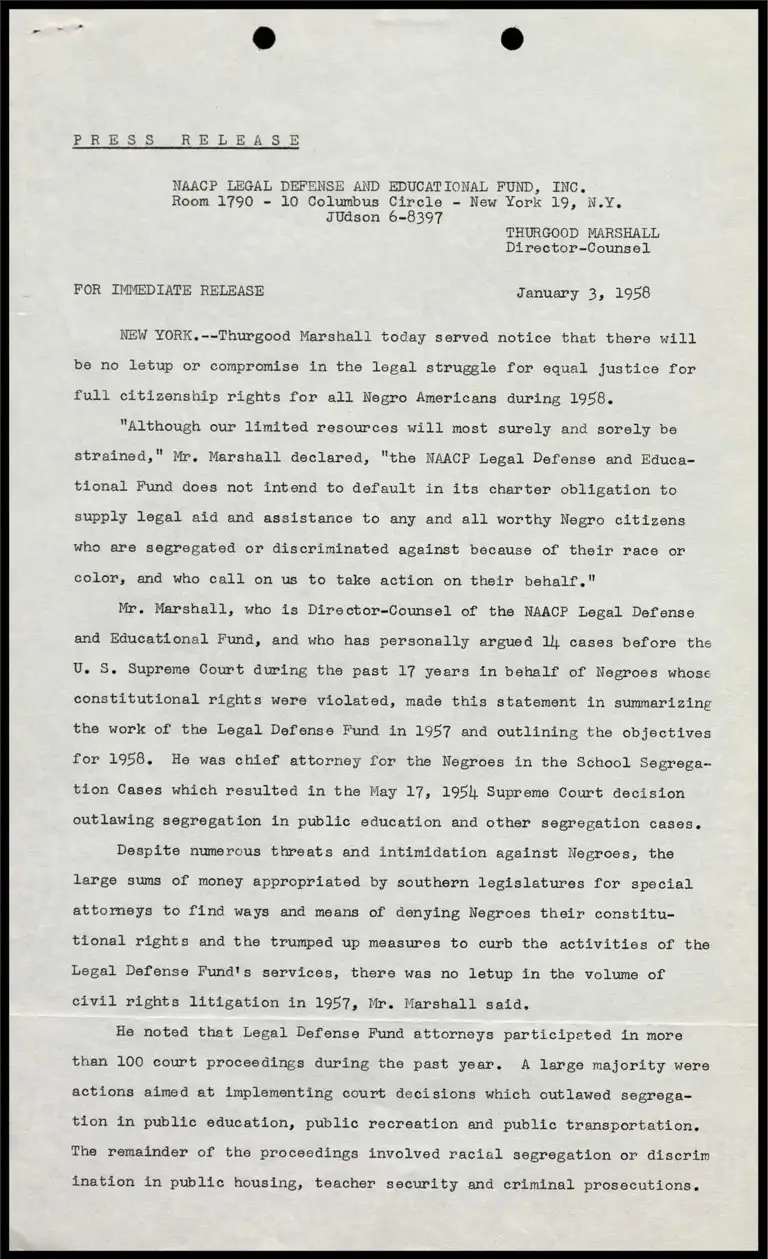

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Room 1790 - 10 Columbus Circle - New York 19, N.Y.

JUdson 6-8397

THURGOOD MARSHALL

Director-Counsel

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 3, 1958

NEW YORK.--Thurgood Marshall today served notice that there will

be no letup or compromise in the legal struggle for equal justice for

full citizenship rights for all Negro Americans during 1958.

"Although our limited resources will most surely and sorely be

strained," Mr. Marshall declared, "the NAACP Legal Defense and Educa-

tional Fund does not intend to default in its charter obligation to

supply legal aid and assistance to any and all worthy Negro citizens

who are segregated or discriminated against because of their race or

color, and who call on us to take action on their behalf,"

Mr. Marshall, who is Director-Counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, and who has personally argued 1h. cases before the

U. S. Supreme Court during the past 17 years in behalf of Negroes whose

constitutional rights were violated, made this statement in summarizing

the work of the Legal Defense Fund in 1957 and outlining the objectives

for 1958. He was chief attorney for the Negroes in the School Segrega-

tion Cases which resulted in the May 17, 195) Supreme Court decision

outlawing segregation in public education and other segregation cases.

Despite numerous threats and intimidation against Negroes, the

large sums of money appropriated by southern legislatures for special

attorneys to find ways and means of denying Negroes their constitu-

tional rights and the trumped up measures to curb the activities of the

Legal Defense Fund's services, there was no letup in the volume of

civil rights litigation in 1957, Mr. Marshall said.

He noted that Legal Defense Fund attorneys participeted in more

than 100 court proceedings during the past year. A large majority were

actions aimed at implementing court decisions which outlawed segrega-

tion in public education, public recreation and public transportation.

The remainder of the proceedings involved racial segregation or discrim

ination in public housing, teacher security and criminal prosecutions.

-2=

Resistance in 1957 to court decisions, Mr. Marshall pointed out,

included an ' ‘endless rash of laws," regulations, investigations and a

series of reprisal measures which further sought to deny Negroes

their basic constitutional rights and also halt the legal activities

of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Such measures are designed to indi-

rectly inhibit integration, Mr. Marshall declared.

"There is every indication that these measures will increase

rather than subside," the civil rights attorney predicted, "and we

must be prepared to meet them."

Mr. Marshall pointed out that only seven of the cases in which

Legal Defense Fund attorneys participated during the year resulted in

adverse decisions. Appeals are now pending in five of them.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund is a non-profit orgai

organization incorporated in 190 to render legal aid to Negroes suf-

fering injustices because of race and color and who cannot afford to

engage the services of qualified legal counsel.

Until recent years the Fund's activities were exclusively direc-

ted toward securing for Negro citizens rights long denied, although

specifically guaranteed them under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the Federal Constitution. However, the Fund

has had to become involved in First Amendment cases because much of

the recent legislation in the South restricts freedom of speech and

association,

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund recently moved its

offices to the New York Coliseum building following a series of bur-

glaries and rifling of the files. It is now located at 10 Columbus

Cirele, Room 1790, New York 19, N. Y.

- 30 -