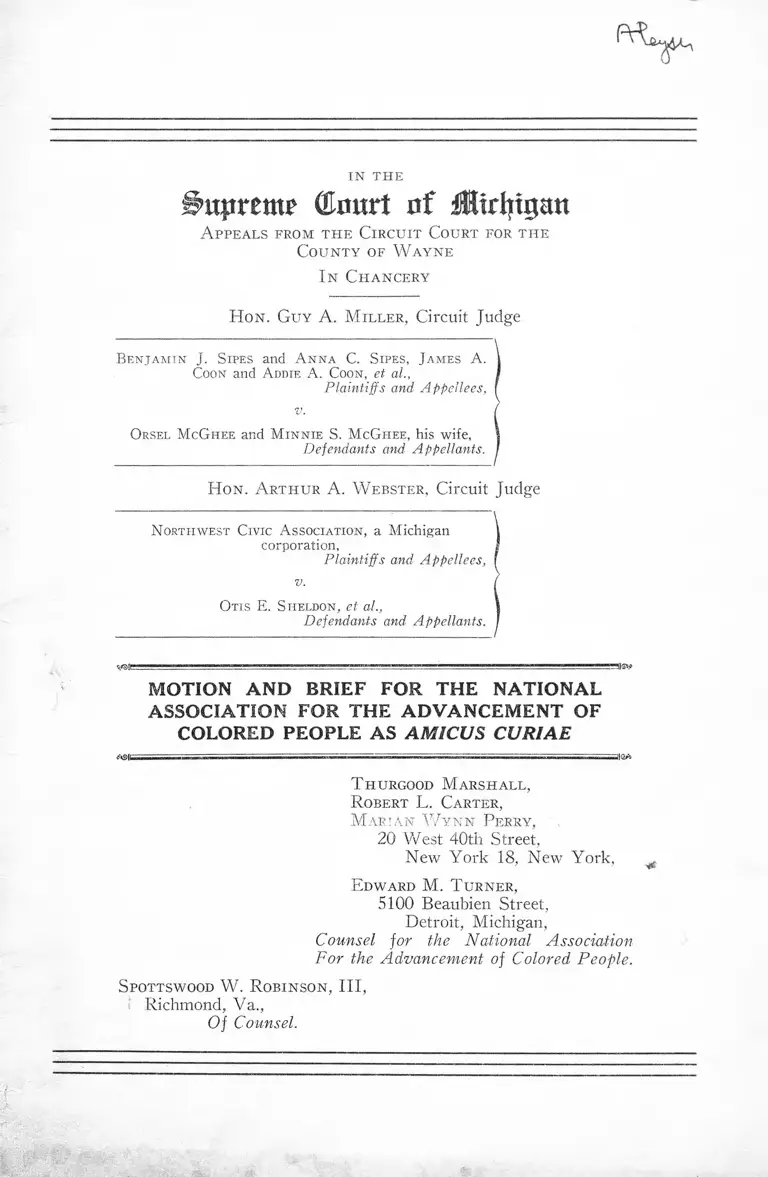

Sipes v. McGhee Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1946

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sipes v. McGhee Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1946. e83b12a6-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4a970a79-03e0-445b-b94d-e32e92b6decc/sipes-v-mcghee-motion-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme (tort of ilirtjtijatt

A ppeals from t h e C ir c u it C ourt for t h e

C o u n t y of W a y n e

I n C h a n c e r y

H o n . G u y A. M ille r , Circuit Judge

Benjamin J. Sipes and A nna C. Sipes, James A.

Coon and A ddie A. Coon, et al.,

Plaintiffs and Appellees,

v.

Orsel McGhee and M innie S. McGhee, his wife,

Defendants and' Appellants.

H o n . A r t h u r A . W ebster , Circuit Judge

Northwest Civic A ssociation, a Michigan

corporation,

Plaintiffs and Appellees,

v.

Otis E. Sheldon, et al.,

Defendants and Appellants.

MOTION AND BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF

COLORED PEOPLE AS AMICUS CURIAE

T hurgood M a r s h a l l ,

R obert L. C arter ,

M a r ia n W y n n P erry ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York, ^

E dw ard M. T u rn e r ,

5100 Beaubien Street,

Detroit, Michigan,

Counsel for the National Association

For the Advancement of Colored People.

S pottswood W . R o b in so n , III,

Richmond, Va.,

Of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for leave to file a brief as Amicus Curiae______ 1

Brief for the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People as Amicus Curiae_________ 3

Statement of F acts___________________________ 3

Statement of Points to be Argued-------------------- 5

Argument:

I. Judicial Enforcement of the Covenant In

Question Is Violative of the Constitution and

Laws of the United States--------------------------- 5

A. The Right to Take and Hold Property

Is Protected By the Constitution and

Laws of the United States______________ 6

B. The Action of the Court Below Enforcing

the Covenant by Injunction Constitutes

State Action in Violation of the Four

teenth Amendment _____________________ 10

II. The Restrictions upon the Use of Land by

Members of Racial or Religious Groups is

against The Public Policy of the State of

Michigan and The United States of America 16

A. The Public Policy of Michigan__________ 18

B. The Public Policy of the United States of

America ________________________________ 20

C. The Race Restrictive Covenant Before

This Court is Injurious to the Interests

of the Public, Interferes with the Public

Welfare and Is at War With the Interests

of Society______________________________ 24

Conclusion_____________________________________ 31

Table—Persons Per Room By Color of Occu

pants, For Residents—Occupied Dwelling

Units, By Number of Rooms, For Detroit

—Willow Run Area: 1944_______________ 32

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases

PAGE

A. F. L. V. Swing, 312 U. S. 321_______________________ 15

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60--------------------------- 8, 9,11

Chicago, Burlington & Quincy v. Chicago, 166 IT. S. 226 14

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 1------------------------------------ 13

Corfield v. Coryell, 4 Wash. C. C. 371--------------------------- 6

Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U. S. 323----- ---------------------- -10,16

Gandolfo v. Hartman, 49 Fed. 181------------------------------ 12

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668----------------------------------- 9

Holden v. Hardy, 169 U. S. 366, 18 Sup. Ct. 383_______ 8

Kennett v. Chambers, 14 How. 38-------------------------------- 12

Parmalee v. Morris, 218 Mich. 625------------ -----------10,15,16

Pittsburgh C. C. & St. Louis R. R. v. Kenny, 95 Ohio

St. 64____________________________________________ _ 17

Raymond v. Chicago Union Trust, 207 U. S. 20---- ---- — 15

Skutt v. City of Grand Rapids, 275 Mich. 258------------ 17, 20

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U. S. 36----------—------------ 6,7, 22

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303-------------------- 6, 23

Tyler v. Harmon, 158 La. 439________________________ 9

Wren, Matter of Drummond, Ontario Reports, 1945,

page 778 ________________________________________ 21, 28

Statutes

PAGE

Michigan, Constitution, Article II, Sec. 1_____________ 19

Michigan, Statutes, Title 15, Sec. 380__________________ 19

Title 24, Sec. 293____ 19

Title 25, Sec. 6_________________________________ 18

Title 28, Sec. 380_______________________________ 19

Title 28, Secs. 343-5___________________________ 19

United Nations Charter___________________________ _— 20

United States Code, Title 8, Sec. 42---------------------------- 8, 23

United States Constitution,

Article IV, Section 2________ ________________ 6

Amendment V ________________________________ 6

Amendment X I I I _____________________________ 6

Amendment XIV, Sec. 1----------------------------------- 6

Textbooks and Other Sources

12 American Jurisprudence 663-------------- -------------------- 9

Architectural Forum, January, 1946__________________ 30

Conference on Home Building, Report of Committee on

Negro Housing____________________________ 24

Detroit Free Press, March 17, 1945__________________ 29

Embree, Brown Americans (1943)_____________________ 29

Gelhorn, Contracts & Public Policy (1935), 35 Col. L.

Rev. 678 _____ ......__________________________ __— 23

Mydral, An American Dilemma (1944)------------------------- 30

The State of Race Relations Today, City of Detroit

Interracial Committee --------------------------- 26

The Michigan Chronicle, May 9, 1945----------------------------- 30

Survey Graphic, Public Housing Charts Its Course,

January, 1945 --------------------------------- 28

U. S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of Census,

Special Survey H . O. No. 143, Aug. 23, 1944------ 26

Population Series, C. A. 3, No. 9, Oct. 1,1944 .24, 25, 32

Woofter, Negro Problem in Cities-------------------------------- 28

I l l

IN THE

Supreme Court of jUtcfugan

A ppeals from th e Cir cu it C ourt fob the

C ounty of W ayne

I n C hancery

H on . G u y A. M iller , Circuit Judge

B e n ja m in J . S ipes and A n n a C. S ipes,

J ames A. Coon and A ddie A. C oon,

et al., Plaintiffs and Appellees,

v.

Orsel M cG hee and M in n ie S. M cG h ee ,

his wife,

Defendants and Appellants.

Hon. A rth u r A . W ebster, Circuit Judge

N orthw est C ivic A ssociation,

a Michigan corporation,

Plaintiffs and Appellees,

v.

O tis E. S heldon , et al.,

Defendants and Appellants.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AS AMICUS CURIAE

To the Honorable, The Chief Justice and the Associate

Justices of the Supreme Court of the State of Michigam:

The undersigned, as Counsel for the National Associ

ation for the Advancement of Colored People, respectfully

2

move this Court for leave to file the accompanying brief

as Amicus Curiae in the above entitled appeals.

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People is a membership organization which for

thirty-five years has dedicated itself to and worked for the

achievement of functioning democracy and equal justice

under the Constitution and laws of the United States.

From time to time some justiciable issue is presented

to this Court, upon the decision of which depends the course

for a long time of evolving institutions in some vital area

of our national life. Such an issue is before the Court now.

In the above entitled appeals, this Court is asked to decide

whether enforcement by state courts of a restrictive cove

nant against use or occupancy of land by Negroes violates

the prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution and is against the public policy of the United

States and the State of Michigan.

It is to present written argument on this issue, funda

mental to the good order, welfare and safety of the com

munity, that this motion is filed.

T hubgood M arshall ,

R obert L. Carter,

M arian W y n n P erry,

E dward M. T urner ,

Counsel for the National Association

For the Advancement of Colored People.

S pottswood W . R obinson , III,

Of Counsel.

IN THE

upreme Court of Jltcfngan

A ppeals from th e C ircuit C ourt for the

County of W ayne

I n C hancery

H on . G u y A. M iller , Circuit Judge

B e n ja m in J. S ipes and A n n a C. S ipes,

J ames A. Coon and A ddie A. C oon,

et al., Plaintiffs and Appellees,

v.

Orsel M cG hee and M in n ie S . M cG h ee ,

his wife,

Defendants and Appellants.

Hon. A rth u r A . W ebster, Circuit Judge

N orthwest C ivic A ssociation,

a Michigan corporation,

Plaintiffs and Appellees,

v.

Otis E. S heldon , et al.,

Defendants and Appellants.

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE AS

AMICUS CURIAE

Statement of Facts

These appeals are taken from decrees of the Circuit

Court of Wayne County by which appellants are restrained

3

4

from using or occupying their homes because of their race

or color. In Sipes v. McGhee the restriction thus enforced

by the court was placed upon appellants’ lot by a former

owner, who signed and recorded an agreement as follows:

“ This property shall not be used or occupied by

any person or persons except those of the Caucasian

race. ’ ’

In Northwest Civic Association v. Sheldon, the restric

tive covenant was placed by the original subdivider on 310

lots out of a total of 338 in the subdivision in the following

language:

“ Said premises shall not be sold nor leased nor oc

cupied by any person other than one of the Caucasian

race. ’ ’

The restriction does not appear in the deed of the original

subdivider to the lot now owned by appellant Sheldon, nor

in any subsequent deed.

Shortly after appellants commenced to occupy their re

spective homes, bills of complaint were filed by owners of

neighboring lots, seeking to restrain appellants from violat

ing the said restrictions. In the Sheldon case it was alleged

and proof was offered that Mr. Sheldon is a Negro but it

was not alleged or proved that the other occupants of the

house, Mrs. Sheldon and her parents, are Negroes. It was

alleged and proof offered that appellant McGhee and the oc

cupants of his house are Negroes.

The Circuit Court of Wayne County has entered decrees

restraining all appellants in the McGhee case from using

or occupying the lot in question, and in the Sheldon case

restraining only Otis E. Sheldon from entering upon, using

or occupying the premises in question.

0

Statement of Points To Be Relied Upon

I

Judicial Enforcement of the Covenant in Question Is Vio

lative of the Constitution and Laws of the United States.

A . T he Right to Take and H old Property Is P rotected by the

Constitution and Laws o f the U nited States.

R. T he A ction o f the Court R elow E nforcing the Covenant

by Injunction Constitutes State A ction in V iolation o f the

Fourteenth Am endm ent.

II

The Restrictions Upon the Use of Land by Members of

Racial or Religious Groups Is Against the Public Policy of

The State of Michigan and the United States of America.

A . The Public P olicy o f M ichigan.

R. The Public P olicy o f the U nited States o f A m erica.

C. The R ace Restrictive Covenant b e fo re this Court Is In

jurious to the Interests o f the Public, Interferes with the

Public W e lfa re and Is at W ar with the Interests o f Society.

A R G U M E N T

I

Judicial Enforcement of the Covenant in Question

Is Violative of the Constitution and Laws of the

United States.

When. Government, through its courts, enforces the type

of restrictive covenant herein complained of, it is action of

the type proscribed by the Constitution and laws of the

United States.

6

A. The Right to Take and Hold Property Is

Protected by the Constitution and Laws of

the United States.

The right to take and hold property is one of the funda

mental and inherent rights and privileges guaranteed by

the Constitution of the United States:

“ The citizens of each state shall be entitled to all

the privileges and immunities of citizens in the sev

eral States.” Article IV, Sec. 2.

state shall make or enforce any law

which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of

citizens of the United States; nor shall any State

deprive any person of life, liberty, or property with

out due process of law.” Amendment XIV, Sec. 1.

“ No person shall * * # be deprived of life, lib

erty or property without due process of law. * * * ” .

Amendment V.

The Supreme Court of the United States has refrained

from attempting to enumerate the several privileges and

immunities which receive constitutional protection, but it

early recognized as one of those rights the right to acquire,

hold, use and dispose of property, both real and personal.

Thus in the Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U. S. 36, 16 Wall.

36, 21 L. Ed. 394 (1873), Mr. Justice Miller cites with ap

proval Corfield v. Coryell, 4 Wash. C. C. 371 as follows:

“ ‘ The inquiry . . . is, what are the privileges

and immunities of citizens of the several states?

We feel no hesitation in confining these expressions

to those privileges and immunities which are funda

mental; which belong of right to the citizens of all

free governments, and which have at all times been

enjoyed by citizens of the several states which com

pose this Union, from the time of their becoming

7

free, independent, and sovereign. What these funda

mental principles are, it would be more tedious than

difficult to enumerate’. ‘ They may all, however, be

comprehended under the following general heads:

protection by the government, with the right to ac

quire and possess property of every kind, and to pur

sue and obtain happiness and safety, subject, never

theless, to such restraints as the government may

prescribe for the general good of the whole’. ” (at

p. 76).

The Supreme Court went on to state:

‘ ‘ This definition of the privileges and immunities

of citizens of the states is adopted in the main by

this court in the recent case of Ward v. Maryland, 12

Wall. 430, 20 L. ed 452, while it declines to under

take an authoritative definition beyond what was

necessary to that decision. The description, when

taken to include others not named, but which are of

the same general character, embraces nearly every

civil right for the establishment and protection of

which organized government is instituted. They are,

in the language of Judge Washington, those rights

which are fundamental. Throughout his opinion, they

are spoken of as rights belonging to the individual as

a citizen of a state. They are so spoken of in the

constitutional provision which he was construing.

And they have always been held to be the class of

rights which the state governments were created to

establish and secure.”

To make certain that there be no misapprehension about

the national policy on this important problem, Congress has

not been content to rely upon the protection afforded in

the basic framework of the Government. Instead, in order

clearly to demonstrate the purpose of the people of the

United States that there should be no restrictions placed

upon the right of a citizen to acquire and hold property,

8

federal legislation designed to give added protection to these

rights was enacted in 1866 providing as follows:

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right, in every State and Territory, as is en

joyed by white citizens thereof, to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal prop

erty.” U. S. Code, Tit. 8, Sec. 42; R. S. 1798.

The consitutionality of this section has never been chal

lenged. It was construed by the United States Supreme

Court in Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 38 Sup. Ct.

16, 62 L. Ed. 149 (1917). There the constitutionality of a

city ordinance was challenged, which forbade colored per

sons from occupying houses as residences, places of abode

or public assembly on blocks where the majority of the

houses were occupied by white persons, and in like manner

restraining white persons when the conditions as to occu

pancy were reversed. The interdiction was based upon

color and nothing more. The Supreme Court held the ordi

nance unconstitutional, and stated in its opinion:

“ Property is more than the mere thing which a

person owns. It is elementary that it includes the

right to acquire, use, and dispose of it. The Consti

tution protects these essential attributes of prop

erty.” (at p. 74).1

Bases of constitutional protection were found by the Court

to exist in the Fourteenth Amendment and it was held that

the Amendment had been given legislative aid by the enact

ment of the statute above set forth. Discussing such legis

lation, the Court stated:

“ The statute of 1866, originally passed under

sanction of the 13th Amendment (14 Stat. at L. 27,

chap. 31), and practically re-enacted after the adop

tion of the 14th Amendment (16 Stat. at L. 144, chap.

1 See also Holden v. Hardy, 169 U. S. 366. 18 Sup. Ct. 383, 42

L. Ed. 780 (1897).

9

114), expressly provided that all citizens of the

United States in any state shall have the same right

to purchase property as is enjoyed by white citizens.

Colored persons are citizens of the United States

and have the right to purchase property and enjoy

and use the same without laws discriminating against

them solely on account of color. . . . These enact

ments did not deal with the social rights of men, but

with those fundamental rights in property which it

was intended to secure upon the same terms to citi

zens of every race and color.” (at pp. 78-79).

The Court concluded with this statement:

“ We think this attempt to prevent alienation of

the property in question to a person of color was

not a legitimate exercise of the police power of the

State, and is in direct violation of the fundamental

law enacted in the Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution preventing State interference with

property rights except by due process of law. That

being the case, the ordinance cannot stand.” (at p.

82).

Subsequently in Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668, 47 Sup.

Ct. 471, 71 L. Ed. 831 (1926), the Supreme Court on

the authority of Buchanan v. Warley, supra, held unconsti

tutional a city ordinance prohibiting the sale of land and

property to Negroes in any “ community or portion of the

city . . . except on the written consent of a majority of- the

persons of the opposite race inhabiting such community or

portion of the city.” Tyler v. Harmon, 158 La. 439, 104 So.

200 (1925).

Thus both an ordinance directly restricting occupancy

on the basis of race, and an ordinance not itself fixing such

a restriction but seeking to lend the power of the state to

action of private citizens who wish so to limit and restrict

residence on the basis of race, are equally contrary to our

fundamental law, and cannot stand.

10

B. The Action of the Court Below Enforcing the

Covenant by Injunction Constitutes State

Action in Violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

It is our contention here that the action of the court

below in enforcing this covenant is unconstitutional. We

do not argue that the contract itself violates the consti

tution. Therefore, because our contention is based on

action by the state itself, neither Parmalee v. Morris, 218

Mich. 625 (1925), nor Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U. S. 323,

46 Sup. Ct. 521, 70 L. Ed. 969 (1926), are in point.

For the reasons considered supra, there is no question

that it would have been beyond the legislative power of the

State of Michigan or the City of Detroit to have enacted a

law providing that a covenant in the precise terms of those

herein involved should be enforceable by the courts by

means of a decree of specific performance, an injunction,

and proceeding for contempt for failure to obey the decree.

It seems inconceivable that so long as the legislature is so

restricted, a court of equity may by its command compel

the specific performance of such a covenant, and thus give

the sanction of the judicial department of the government

to an act which was not within the competency of its legis

lative department to authorize.

But in this case the court below has gone further. It

has not required that parties perform their contracts. It

has by judicial action created a rule of property and has

made that rule binding upon persons who have not agreed

to it. In such circumstances it must be entirely clear that

the government, and only the government, is the effective

force depriving the appellants of their property.

We cannot emphasize too strongly that the immediate

consequence of the decree now under review is to bring

11

about that which the legislative and executive departments

of the government are powerless to accomplish. This

decree has all the force of a statute. It has behind it the

sovereign power. It follows that by this decree the appel

lants have been deprived of liberty and property, not by

individual, but by governmental action.

It is not the appellees but the sovereignty, which has

spoken through its courts, which has issued a mandate to the

appellants directing them to move from their homes and

restraining and enjoining them from using or occupying

the premises. In rendering such a decree, the court has

functioned as a law making body. It is the court which

has effectuated a policy of racial segregation. It is the

court which has virtually announced to all colored persons:

“ You shall not use or occupy land which you own or lease

simply because you are of the African race.”

It has practically declared: “ If the owners of property

in a particular locality, however extensive its area may be,

see fit to agree on such a policy of segregation, these courts,

sitting in equity, may by their decrees enforce such a policy,

even if it be conceded that they would be prohibited from

doing so by the decision of the Supreme Court of the

United States if the legislative branch of the Government

had established a like policy.”

To test the incongruity of such a situation, let us sup

pose that after the decision in Buchanan v. Warley, supra,

the Common Council of the City of Louisville had adopted

an ordinance permitting the residents of the same districts

which were affected by the ordinance which the Supreme

Court had declared unconstitutional, to enter into a covenant

in the precise terms of that which the court below has en

forced in this case, and providing for their enforcement by

the court. "Would it not at once have been said that it was

12

an intolerable invasion of the Constitution as interpreted by

the Supreme Court? But that is exactly what has been

done in the present cases by the adjudication which is now

here for review.

Such inconsistency between legislative and judicial ac

tion was the subject of the following comment in Gandolfo

v. Hartman, 49 Fed. 181 (C. C., S. D. Cal., 1892):

“ It would be a very narrow construction of the

constitutional amendment in question and of the deci

sions based upon it, and a very restrictive application

of the broad principles upon which both the amend

ment and the decisions proceed, to hold that, while

the State and municipal legislatures are forbidden

to discriminate against the Chinese in their legisla

tion, a citizen of the State may lawfully do so by

contract, which the Courts may enforce. Such view

is, I think, entirely inadmissible. Any result in

hibited by the Constitution can no more be accom

plished by contract of individual citizens than by

legislation, and the court should no more enforce the

one than the other. * * * But the principle governing

the case is, in my opinion, equally applicable here,

where it is sought to enforce an agreement made

contrary to the public policy of the government, and

in violation of the principles embodied in its Con

stitution. Such a contract is absolutely void and

should not be enforced in any Court, certainly not

in a court of equity of the United States.” (at pp.

182, 183).2

An illuminating analysis of the extent to which the

state is called upon to take action in enforcing a restrictive

covenant appears in the brief amicus curiae submitted by

the Attorney General of the State of California, Bobert W.

Kenny, in the case of Andersen v. Anseth, pending on ap-

2 Compare: Kennett v. Chambers, 14 How. 38, 14 L. Ed. 316

(1852).

13

peal in the Supreme Court of the State of California (L. A.

No. 19759). There, the Attorney General supports the re

spondent’s conclusion that the race restrictive covenant

should not be enforced. In establishing the interest of the

state in the appeal, the brief takes the following position:

“ The state as a whole is interested in this matter.

The aid of its courts, nisi prius appellants, has been

sought; its clerks, sheriffs and constables have been

called to issue and serve writs, which issue in the

name of the People of the State of California. Ulti

mately (if the hopes of plaintiffs and appellants are

realized) even the jails of the State may be called

upon to play a part in these actions.

“ Under such circumstances we do not feel that the

legal arm of the state should remain inactive.

“ When the state is called upon to take State action

in its own name against a large segment of its law

abiding citizens, the law officers of the state should

be heard.”

It is settled that action by the judicial arm of the state

is state action within the prohibition of the Fourteenth

Amendment-

In the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 1, 3 Sup. Ct. 18, 27

L. Ed. 835 (1883), where the Supreme Court was examin

ing into the power of the Congress to enact legislation seek

ing to secure for the recently freed slave full and equal

enjoyment of accommodations, facilities, inns, public con

veyances and other places of public amusement, judicial

action was recognized as state action within the prohibition

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus the Court states:

‘ ‘ In this connection it is proper to state that civil

rights, such as are guaranteed by the Constitution

against state aggression, cannot be impaired by the

wrongful acts of individuals, unsupported by state

14

authority in the shape of laws, customs or judicial

or executive proceedings. The wrongful act of an

individual, unsupported by any such authority, is

simply a private wrong, or a crime of that individual;

an invasion of the rights of the injured party, it is

true, whether they affect his person, his property or

his reputation; but if not sanctioned in some way by

the State, or not done under state authority, his

rights remain in full force, and may presumably be

vindicated by resort to the laws of the State for re

dress. An individual cannot deprive a man of his

right to vote, to hold property, to buy and to sell, to

sue in the courts or to be a witness or a juror; he

may, by force or fraud, interfere with the enjoyment

of the right in a particular case; he may commit an

assault against the person, or commit murder, or use

ruffian violence at the polls, or slander the good name

of a fellow citizen; but, unless protected in these

wrongful acts by some shield of state law or state

authority, he cannot destroy or injure the right; . . .

(at p. 17).

“ It [the Fourteenth Amendment] nullifies and

makes void all state legislation and state action of

every hind which impairs the privileges and immuni

ties of citizens of the United States or which injures

them in life, liberty or property without due process

of law, or which denies to any of them the equal

protection of the laws.” (at p. 11). (Italics added.)

In Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad v. City of

Chicago, 166 U. S. 226, 17 Sup. Ct. 581, 41 L. Ed. 979

(1896), the Supreme Court found that the action of a court

in the State of Illinois in depriving appellant of land with

out due process of law was within the prohibition of the

Fourteenth Amendment, and the Court states:

“ But it must be observed that the prohibitions of

the Amendment refer to all the instrumentalities of

the State, to its legislative, executive, and judicial

15

authorities, and, therefore, whoever by virtue of

public position under a state government deprives

another of any right protected by that Amendment

against deprivation by the state, ‘ violates the con

stitutional inhibition; and as he acts in the name and

for the state, and is clothed with the state’s power,

his act is that of the state.’ This must be so, or, as

we have often said, the constitutional prohibition has

no meaning, and ‘ the state has clothed one of its

agents with power to annul or evade it.’ ” (at p. 234).

Further the Court states:

‘ ‘ But a state may not, by any of its agencies, dis

regard the prohibitions of the 14th Amendment. Its

judicial authorities may keep within the letter of the

statute prescribing forms of procedure in the courts

and give the parties interested the fullest oppor

tunity to be heard, and yet it might be that its final

action would be inconsistent with that Amendment. ’ ’

(at p. 235).8

The action of a state court granting an injunction

against picketing was found by the Supreme Court to con

stitute an invasion of the rights secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment and the Court in its opinion stated in American

Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U. S. 321, 61 Sup. Ct.

568, 85 L. Ed. 855 (1940):

“ The scope of the Fourteenth Amendment is not

confined by the notion of a particular state regarding

the wise limits of an injunction in an industrial dis

pute, whether those limits be defined by statute or by

the judicial organ of the state.” (Italics added.)

The case of Parmalee v. Morris, 218 Mich. 625 (1922),

wherein a race restrictive covenant was upheld as not in 3

3 See also Raymond v. Chicago Union Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20,

28 Sup. Ct. Rep. 7, 52 L. Ed. 78 (1907).

16

itself violating the 14th Amendment, is not controlling in

this case, since the issue-of state action was not raised on

that appeal. In its decision there, this Court made the fol

lowing statement:

“ Were the defendant’s claim of rights based

upon any action taken by the authority of the State,

an entirely different question would be presented. ’ ’ 4

Further, in the decision in the Parmalee case, it is stated

that the protection of the 14th Amendment is confined to

“ state legislation” . Such a narrow definition of state ac

tion is not in line with the United States Supreme Court’s

decisions on this point as indicated, supra. Therefore the

Parmalee case can no longer be considered authoritative.

II

The Restrictions Upon the Use of Land by

Members of Racial or Religions Groups Is

Against the Public Policy of the State of Mich

igan and the United States of America.

It is said an agreement is against public policy if “ it is

injurious to the interests of the public, contravenes some

established interest of society, violates some public statute,

is against good morals, tends to interfere with public wel

fare or safety, or, as it is sometimes put, if it is at war with

the interests of society and is in conflict with the morals of

the time.” 12 Amer. Jur. 663.

4 The case of Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U. S. 323, 46 Sup. Ct. 521,

70 L. Ed. 969 (1926), is sometimes cited in support of the constitu

tionality of judicial enforcement of restrictive covenants. There the

Supreme Court pointed out that the constitutionality of the decrees

of the lower court had not been raised on appeal and was not before

the Court.

17

In Skutt v. City of Grand Rapids, 275 Mich. 258 (1936),

this Court adopted as its definition of public policy the fol

lowing statement from Pittsburgh C. C. <& St. Louis R. Co.

v. Kenney, 95 Ohio St. 64:

“ What is the meaning of ‘ public policy’ ! . . .

In substance it may be said to be the community com

mon sense and common conscience, extended and

applied throughout the State to matters of public

morals, public health, public safety, public welfare,

and the like. It is that general and well settled public

opinion relating to man’s plain, palpable duty to his

fellow men, having due regard to all the circum

stances of each particular relationship and situation.

“ Sometimes such public policy is declared by con

stitution, sometimes by statute, sometimes by judicial

decision. More often, however, it abides only in the

customs and convictions of the people—in their clear

consciousness and conviction of what is naturally and

inherently just and right between man and man. It

regards the primary principles of equity and justice

and is sometimes expressed under the title of social

and industrial justice, as it is conceived by our body

politic. . . . It has frequently been said that such

public policy is a composite of constitutional provi

sions, statutes and judicial decisions, and some courts

have gone so far as to hold that it is limited to these.

The obvious fallacy of such a conclusion is apparent

from the most superficial examination. When a con

tract is contrary to some provision of the Constitu

tion, we say it is prohibited by the Constitution, not

by public policy. When a contract is contrary to

statute, we say it is prohibited by statute, not by

public policy. When a contract is contrary to a

settled line of judicial decisions, we say it is pro

hibited by the law of the land, but we do not say it is

contrary to public policy. Public policy is the corner

stone—the foundation—of all constitutions, statutes

and judicial decisions, and its latitude and longitude,

18

its height and its depth, greater than any or all of

them. ’ ’

A proper exercise of the equitable discretion of the

Court, in the light of the anti-social character of the con

tract here involved and the large actual and potential injury

to public and community interests which would result from

the enforcement of the decree in the court below requiring

the appellants to move from their homes, should have led

the court below to refuse the relief requested by the plain

tiff-respondent.

A. The Public Policy of Michigan

The decree of the court below in Northwest Civic Asso

ciation v. Sheldon has the effect of barring appellant Otis

E. Sheldon from living with his wife, Louise Sheldon, who

is likewise an appellant, in a home which they have pur

chased for that purpose. Such a result, in itself, is clearly

grounds for finding that the action of the court below in

the Sheldon case is against public policy. In 1883 the Mich

igan legislature by Public Act 23 validated marriages and

legitimatized the issue of marriages between Negroes and

whites. (25 Mich. Stat. Ann. 6.) The practical fact of the

situation is that the appellant Louise Sheldon may remain

in her home but her husband may not visit her without be

coming liable to contempt proceedings. And this result is

arrived at solely because of appellant Otis E. Sheldon’s

race. Such an unwarranted interference, against the wishes

of the parties, with a marital relationship violates the most

fundamental concepts of human decency and runs counter

to the purpose of Public Act 23 of the Michigan legislature

of 1883.

There are many other clear indications that the public

policy of the State of Michigan, insofar as it is reflected

19

in it's constitution and statutes, is opposed to segregation.

Discrimination or segregation based on race or color is

forbidden in inns, hotels, restaurants, and other places of

public resort and amusement, 28 Mich. Stat. Ann. 343-5; in

public schools, 15 Mich. Stat. Ann. 380; and in the premiums

or policies of life insurance companies, 24 Mich. Stat.

Ann. 293.

The state is forbidden by Article II, Section 1, of the

constitution of Michigan from discrimination in the follow

ing language:

“ All political power is inherent in the people.

Government is instituted for their equal benefit, se

curity and protection.”

In an opinion of the Attorney General of the State of

Michigan, October 7, 1940, cited at 28 Mich. Stat. Ann. 343,

it is stated that Negroes may not lawfully be prohibited

from living in a city or from staying all night solely because

of race or color.

In the light of these constitutional and statutory provi

sions, it is clear that the Michigan public policy is opposed

to segregation of the races whether accomplished by indi

vidual action or by authority of the state.

It is apparent that should a suit in equity be brought

before this Court against an innkeeper whose inn was built

upon land covered by a race restrictive covenant, seeking

to force him to exclude Negroes, this Court must hold that

enforcement of the covenant would be in violation of the

public policy of the State. Otherwise this Court would, by

its decree, require the innkeeper to commit a misdemeanor.

The laws of Michigan would also require this Court to find

such a covenant unenforceable as against a public school

built on land covered by such a covenant.

20

It would seem to follow that such a race restrictive cove

nant, the enforcement of which in some instances would

require this Court to direct the commission of a crime, must

be against public policy of the state of Michigan in all

eases. Since the restriction runs against use or occupancy,

it would be most inequitable to enforce it against a private

owner, forbidding him to occupy his own property, while

refusing to enforce it against a commercial owner, and re

quiring him to allow Negroes to live in his hotel or inn.

B. The Public Policy of the United States

of America

The public policy of the United States concerning seg

regation is also reflected by the Constitution, by the Amend

ments thereto, by statutory enactments thereunder, and by

the decisions of the courts interpreting this written body

of law. In addition, the public policy of the United States

must necessarily be changed and increased by its subscrip

tion to the Charter of the United Nations, the preamble of

which contains the following statement:

“ We, the people of the United Nations, determined

to save succeeding generations from the scourge of

war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold

sorrow to mankind, and to reaffirm faith in funda

mental human rights, in the dignity and worth of

the human person, in the equal rights of men and

women and of nations large and small . . . and

for these ends to practice tolerance and live together

in peace with one another as good neighbors . . . ”

As a member of the United Nations the United States is

pledged to promote universal respect for the observance

of “ human rights and fundamental freedoms for all with

out distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.”

21

In determining the solemnity with which onr govern

ment has undertaken its responsibility for promoting these

basic purposes of the United Nations, it is significant that

the United Nations grew out of the struggle in which our

government and the people of the country willingly sacri

ficed the lives of thousands of its citizens in order to insure

the perpetuation and maintenance of our way of life. In

that war, the declared purpose of our government as set

forth in the Atlantic Charter was the establishment of the

four freedoms which included freedom from fear and free

dom of worship. It cannot be said that the dedication of our

nation to victory in the war to establish these principles

did not affect our public policy. In fact the actions of the

whole people in sacrificing their lives and resources to

establish these principles is the clearest evidence of the

public policy of this country.

The effect of the United Nations Charter and the Atlantic

Charter upon the public policy of a member nation of

the United Nations has been discussed in full in Matter

of Drummond Wren decided in the Ontario Supreme Court

on October 29, 1945 (Ontario Reports, 1945, p. 778). In

that case the Ontario Court found a restriction against the

sale of land to Jews “ or persons of objectionable nation

ality” to be unenforceable as against the public policy of

Ontario and Canada. Significantly after reviewing the re

sponsibility of the Government of Canada for maintaining

the principles expressed in the Charter of the United

Nations, the Court stated that the public policy applicable

did not depend upon the terms of a local statute against

racial discrimination but was based on a broader policy,

established through the adoption of the United Nations

Charter, which, after ratification, became a part of the

fundamental law of the Dominion.

Further documenting of the public policy of the United

States and member nations of the United Nations in

this regard, the Anglo-American Commission, consisting

of representatives appointed by the British Crown and the

President of the United States to conduct an inquiry on

Jews in Europe and Palestine, discussed at some length in

Eecommendation No. 7 of its report the effect of racial or

religious restrictions upon the sale, lease or use of land

in Palestine and stated that the retention of such stipula

tions are “ harmful to cooperation and understanding be

tween Arabs and Jews.”

Even prior to the entry of our country into a war

against fascism in Europe and Asia, public policy of the

United States was opposed to segregation and proscriptions

based on race or color. Public policy concerning the legal

rights of Negroes was first established following the Civil

"War when the people of the United States enacted the 13th

Amendment to abolish slavery and the 14th Amendment

to abolish the badges of servitude.

In a consideration of the Amendments in 1872 while the

struggle for their enactment was still alive in the memory

of the court, the Supreme Court stated in the Slaughter-

House Cases, supra:

“ . . . no one can fail to be impressed with the

one pervading purpose found in them all, lying at

the foundation of each, and without which none of

them would have been even suggested; we mean the

freedom of the slave race, the security and firm

establishment of that freedom, and the protection of

the newly made freedman and citizen from the op

pressions of those who had formerly exercised unlim

ited dominion over him.” (at p. 71).

23

Subsequently, in 1879, in Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U. S. 303, 25 L. Ed. 664, after referring at length to its

decision in the Slaughter-House Cases, the Court stated:

“ What is this [the amendment] but declaring

that the law in the States shall be the same for the

black as for the white; that all persons, whether

colored or white, shall stand equal before the laws

of the States, and, in regard to the colored race, for

whose protection the Amendment was primarily de

signed, that no discrimination shall be made against

them by law because of their color! The words of

the Amendment, it is true, are prohibitory, but they

contain a necessary implication of a positive im

munity, or right, most valuable to the colored race—

the right to exemption from unfriendly legislation

against them distinctively as colored; exemption from

legal discriminations, implying inferiority in civil

society, lessening the security of their enjoyment of

the rights which others enjoy, and discriminations

which are steps toward reducing them to the condi

tion of a subject race.” (at p. 308).

Nothing can be more explicit in explaining the public

policy of the United States than section 42 of Title 8 of the

United States Code which we shall set forth here once more.

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right, in every State and Territory, as is en

joyed by white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal prop

erty.”

The significance of such legislation upon the exercise of

judicial discretion in dealing with contracts inconsistent

with public policy, thus authoritatively declared, has been

stated by one commentator in the following language:

“ . . . the courts will refuse to enforce a con

tract, not ‘ because it is illegal’ or because the legis-

24

lature ‘ intended that a person making* such a con

tract be punished’, but because they have satisfied

themselves, in the light of what has been indicated

to them by legislative bodies, at home or abroad, the

contract is against public policy . . . the courts

should frown upon contracts which, though not

touching a penal statute, involve other conduct which

has been inveighed against by the legislature. What

is suggested is not an extension of the scope of judi

cial disapprobation of contracts, for at all times the

courts have freely declared that non-criminal agree

ments might be against public policy and conse

quently unenforcible. What is urged, again, is

merely that legislative judgments should be used as

indicators of the occasion for employment of the

common law rule governing the validity of con

tracts.” (Italics added.) Gelhorn, Contracts and

Public Policy (1935), 35 Col. L. Rev. 678, 691-2.

C. The Race Restrictive Covenant Before This

Court Is Injurious to the Interests of the

Public, Interferes with the Public Welfare

and Is at War with the Interests of Society

Residental segregation, which is sought to be maintained

by court enforcement of the race restrictive covenant before

this Court, “ has kept the Negro occupied sections of cities

throughout the country fatally unwholesome places, a

menace to the health, morals and general decency of cities,

and plague spots for race exploitation, friction and riots!”

Report of the Committee on Negro Housing of the Presi

dent, Conference on Home Building, Vol. VI, pp. 45, 46

(1932).

The extent of overcrowding resulting from the enforced

segregation of Negro residents is daily increasing. The

United States Census of 1940 examines the characteristics

of 19 million urban dwellings. The census classifies a

25

dwelling as overcrowded if it is occupied by more than 1%

persons per room. On this basis 8 percent of the units occu

pied by whites in the nation are classified in the 1940 census

as overcrowded, while 25 percent of those occupied by non

whites are so classified. In Baltimore, Maryland, Negroes

comprise 20 percent of the population yet are constricted

in 2 percent of the residential areas. In the Negro occupied

second and third wards of Chicago, the population density

is 90,000 per square mile, exceeding even the notorious

overcrowding of Calcutta.

In Table A, post, there are set forth the statistics of

number of persons per room by color for resident occupied

dwelling units in 1944 in the Detroit-Willow Run Area.

These figures show that while in the total population over

crowding was serious, for the non-white population the

problem reached critical proportions.

Thus, 8 percent of the non-white residents of the Detroit-

Willow Run Area lived at a density in excess of IV2 persons

per room, while only 2.3 percent of the white residents were

classified as overcrowded in the census of 1940.

The critical lack of housing facilities in Michigan’s non

white population is emphasized by the following quotation

from another census study of the Detroit Metropolitan

District.

“ Vacancy rates were generally lower in Negro

sections than in white sections. The gross vacancy

rate among dwelling units for Negro occupancy was

0.4 percent and among those for white occupancy 0.8

percent.

“ Habitable vacancies represented about seven

eighths of the unoccupied dwellings intended for

white occupants and one half of those for Negro

occupants.

“ Crowded dwelling units-—those housing’ more

than IV2 persons a room—made up 1.3 percent of

the dwellings in white neeighborhoods and 7.4 per

cent of the dwellings in Negro neighborhoods. These

units [Negro housing*] had only one percent of all

the entire area but were occupied by three percent

of its population.” (U. S. Department of Commerce,

Bureau of Census, Special Survey H. 0. No. 143,

August 23, 1944.)

The overcrowding of the entire community during the

period from 1940 to 1944 can be emphasized by the growth

of the Detroit Metropolitan District’s population from

2,295,867 in 1940 to 2,455,035 in 1944. During the same

period the non-white population in the Metropolitan area

increased from 171,877 to 250,195 (U. S. Department of

Commerce, Bureau of Census, Population Series C. A. 3

No. 9, October 1, 1944).

According to the Bureau of Census, the non-white popu

lation of Detroit itself increased from 150,790 in 1940 to

213,345 in June of 1944, a percentage increase of 41.5 per

cent. There exists no accurate survey of the extent of race

restrictive covenants in the Detroit Metropolitan District.

However, the experience of the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People in Detroit indicates

that such restrictions constitute a serious limitation on the

amount of living space available for Detroit Negro citizens.

On June 19, 1946, the City of Detroit Interracial Com

mittee submitted its Report on The State of Race Relations

Today. In this report is the statement of Director George

Schermer which contains a discussion of the social effect

of restrictive covenants. Mr. Schermer states:

“ These practices have inflicted serious injury to a

large number of individuals. Also it takes no effort

to demonstrate that they have inflicted serious social

injury upon the entire community.” (at p. 7).

26

27

Competent professionals working in the housing field

repeatedly have pointed out the social cost and public injury

which resulted from these race restrictions. Thus, John J.

Blandford, Jr., Administrator of the National Housing

Agency, speaking in Columbus, Ohio on October 2, 1944,

had this to say:

“ I do not need to tell you of the difficulties we

encountered even after we could establish the need

of migrating Negro war workers. We met troubles

from the start of the war housing job, but they were

multiplied every time we tried to build a project,

open to Negroes. These difficulties—of site selec

tion, of obtaining more ‘ living space’—were deep-

rooted and had to be overcome, one by one. And

delays only made more desperate the plight of both

those who migrated to take war jobs and those al

ready living in war industry centers.

“ The average citizen knows generally that re

strictions on Negroes abound, just as he knows slums

abound in our major cities. But does he know that,

as in those cities, there’s hardly a decent piece of

land a Negro can build on in his own home town!

Does he know that new living space is imperative

because the present limited spaces are crowded to the

point that disease and crime ultimately will be bred

there—if it doesn’t already exist? Does he know

how the concentration of war industries has affected

the lives of Neg’roes who have lived a few blocks

away from his own home for years—now crowded

together as never before—or the newcomers who

have been forced upon them? Well, if not, the facts

must be told and told again as facts about his home

town—not of cities far away.

“ The core of the housing problem of Negroes is,

of course, more living space.”

To the same effect is the comment of the Commissioner,

Federal Public Housing Authority, Philip M. Klutznick, in

his article, Public Housing Charts Its Course, published in

Survey Graphic for January, 1945:

“ But the minority housing problem is not one of

buildings alone. More than anything else it is a

matter of finding space in which to put the buildings.

Large groups of these people are being forced to

live in tight pockets of slum areas where they in

crease at their own peril; they are denied the oppor

tunity to spread out into new areas in the search for

decent living.

“ The opening of new areas of living to all

minority groups is a community problem. And it is

one of national concern.”

This is not a new situation, but it is becoming more

aggravated from year to year. As far back as 1928 one of

the most discerning writers in this field clearly pointed out

what was happening and its social dangers:

‘ ‘ Congestion comes about largely from conditions

over which the Negroes have little control. They are

crowded into segregated neighborhoods, are obliged

to go there and nowhere else, and are subjected to

vicious exploitation. Overcrowding saps the vitality

and the moral vigor of those in the dense neighbor

hoods. The environment then, rather than heredi

tary traits, is a strong factor in increasing death-

rates and moral disorders. Since the cost of sick

ness, death, immorality and crime is in part borne

by municipal appropriations to hospitals, jails and

courts, and in part by employers’ losses through

absence of employees, the entire community pays for

conditions from which the exploiters of real estate

profit.” Woofter, Negro Problem In Cities (1938)

at page 95.

It is also widely recognized that these anti-social cove

nants are not characteristically the spontaneous product of

29

the community will but rather result from the pressures

and calculated action of those who seek the exploit for their

own gain residential segregation and its consequences.

This process has been aptly discribed by W oof ter, op. cit.

supra at page 73:

“ The riots of Chicago were preceded by the

organization of a number of these associations

(neighborhood protective associations); and an

excellent report on their workings is to be found in

The Negro in Chicago, the report of the Chicago

Race Commission. The endeavor of such organiza

tions is to pledge the property holders of the

neighborhood not to sell or rent to Negroes, and to

use all the possible pressures of boycott and ostra

cism in the endeavor to hold the status of the area.

They often endeavor to bring pressure from banks

against loans on Negro property in the neighbor

hood, and are sometimes successful in this.

“ The danger in such associations lies in the ten

dency of unruly members to become inflamed and to

resort to acts of violence. Although they are a usual

phenomenon when neighborhoods are changing from

white to Negro in northern cities, no record was

found in this study where such an association had

been successful in stopping the spread of a Negro

neighborhood. The net results seem to have been a

slight retardation in the rate of spread and the cre

ation of a considerable amount of bitterness in the

community.” Cf. Embree, Broivn Americans (1943)

at page 34 reporting 175 such organizations in Chi

cago alone.

James M. Haswell, in a featured article in the Detroit

Free Press for March 17,1945, estimates 150 such organiza

tions are functioning in Detroit.

30

The same thesis with reference to the City of Detroit

was recently elaborated by Dr. Alfred M. Lee, Professor of

Sociology at Wayne University:

“ Emphasizing overcrowding and poor housing as

one of the major causes of racial disturbances, Lee

declared that in his opinion real estate dealers and

agents have been doing more to stir up racial an

tagonisms in Detroit than any other single group.

“ ‘ These men (real estate dealers),’ Lee said,

‘ Are the ones who organize, promote and maintain

restrictive covenants and discriminatory organiza

tions. I am convinced that once it is possible to

break the legality of these covenants, a great deal of

our troubles will disappear.’ ’ ’ As reported in The

Michigan Chronicle for May 9, 1945.

Other significant analyses of racial conflicts emphasize

the evils of segregation and its contribution to tension and

strife.

“ But they [the Negroes] are isolated from the

main body of whites, and mutual ignorance helps

reinforce segregative attitudes and other forms of

race prejudice” . Myrdal, An American Dilemma,

(1944) vol. 1, page 625.

‘ ‘ The Detroit riots of 1943 supplied dramatic evi

dence: rioting occurred in sections where white and

Negro citizens faced each other across a color line,

but not in sections where the two groups lived side

by side.” Good Neighbors, Architectural Forum,,

January 1946.

The dangers to society which are inherent in the restric

tion of members of minority groups to overcrowded slum

areas are so great and are so well recognized that a court

of equity, charged with maintaining the public interest,

should not, through the exercise of the power given to it

31

by the people, intensify so dangerous a situation. There

fore, in the light of public interest, the court below erred

in granting the plaintiff’s petition and ordering the defen

dants to move from their homes.

Conclusion

The action of the Court below enforcing the race re

strictive covenants against appellants violates the Constitu

tion of the United States and is against public policy of the

State of Michigan and the United States of America.

Therefore, the decrees below should be vacated.

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood M arshall,

R obert L. Carter,

Marla n W y n n P erry,

E dward M. T urner,

Counsel for the National Association

For the Advancement of Colored People.

S pottswood W. R obinson , III,

Of Counsel.

32

TABLE A *

T able 28.—Persons Per Room by Color of Occupants, for Resident-O ccupied Dwelling

Units, by Number of Rooms, for Detroit-W illow Run A rea: 1944

T otal

N umber of Rooms

Total

1 room .................

2 rooms .................

3 rooms .................

4 rooms .................

5 rooms .................

6 rooms .................

7 rooms .................

8 rooms .................

9 or more rooms. .

Reporting Persons per room

person 0.50 or 0.51 to 0.76 to 1.01 to 1.51 to 2.01 or

per room less 0.75 1.00 1.50 2.00 more

733,040 250,745 204,600 201,355 55,055 16,995 4,290

16,885 9,845 4,620 2,420

32,505 9,570 15,510 4,675 2.035 715

68,750 8,360 32,615 17,215 6,270 3,685 605

108,460 38,115 31,515 22,550 13,475 2,255 550

229,295 67,980 61,435 80,410 15,070 4,400

159,610 70,290 39,765 38,665 10,890

59,840 24,915 23,210 8,910 2,805

33,880 19,635 9,350 3,025 1,870

23,815 11,880 6,710 5.225

Nonwhite

Number of Rooms Reporting Persons per room

person 0.50 or 0.51 to 0.76 to 1.01 to 1.51 to 2.01 or

per room more 0.75 1.00 1.50 2.00 more

Total............. 56,100 11,990 11,275 17,655 10,450 3,575 1,155

1,705 880 385 440

2 rooms ................... 3/410 770 1,485 660 275 220

3 rooms ......... '........ 7,535 770 3,080 1,815 935 715 220

4 rooms ................... 11,385 3,410 2,530 2,530 2,090 550 275

5 rooms ................... 15,015 3,135 2,255 5,445 2,530 1,650

6 rooms ................... 9,570 2,255 1,320 3,080 2,915

7 rooms ................... 3,630 770 990 1,155 715

8 rooms ................... 2,640 770 825 440 605

9 or more rooms. . . 1,210 110 275 825

* United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census, Series CA-3, No. 9, October 1,

1944.

The figures on white occupancy in the text of the brief are arrived at by subtracting the figures

for “non-white” from the figures for “total” occupancy.

<^g!|£5i»2i2 [5386]

L awyers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y . C .; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300