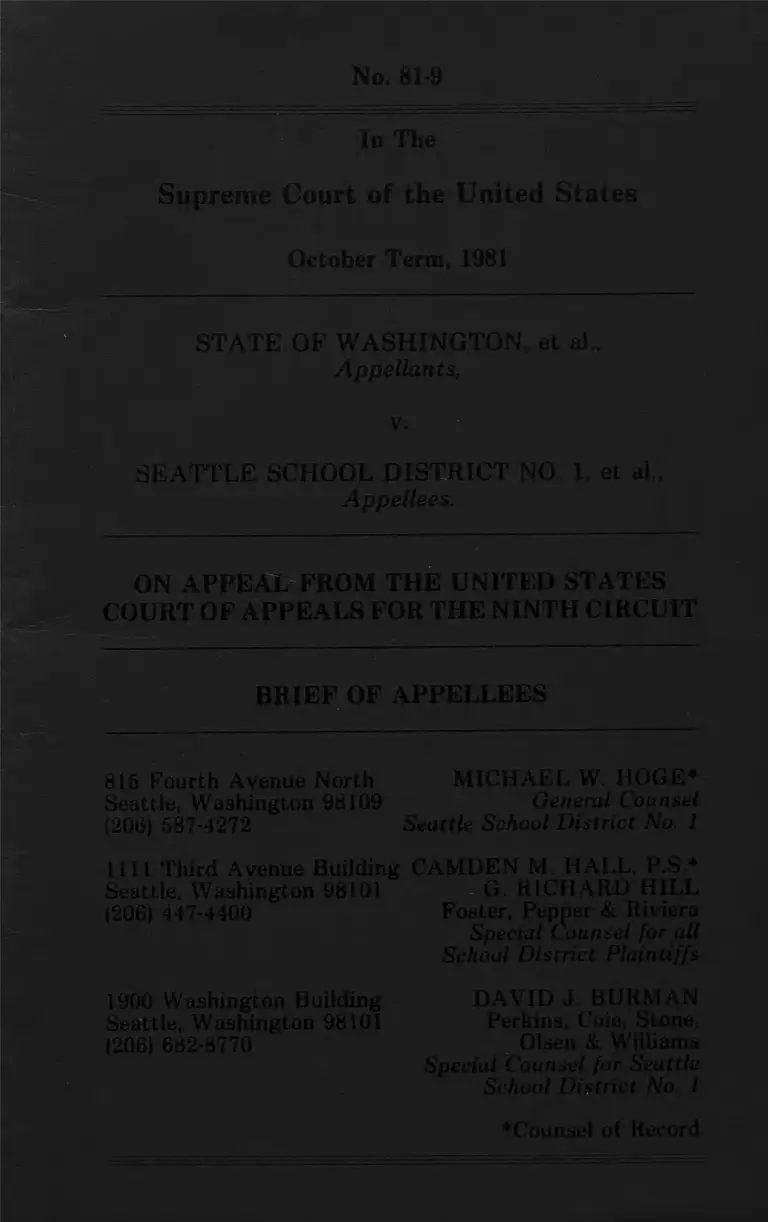

Washington State v. Seattle School District No. 1 Brief of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 25, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Washington State v. Seattle School District No. 1 Brief of Appellees, 1982. b32c4c9d-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4a998d3d-2a6f-4f5c-a1ea-81c701bab14e/washington-state-v-seattle-school-district-no-1-brief-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1981

STATE OF WASHINGTON, et aL,

Appellants,

v,

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al„

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

815 Fourth Avenue North MICHAEL W. HOGE*

Seattle, Washington 98109 General Counsel

(206) 587-4272 Seattle School District No. 1

1111 Third Avenue Building CAMDEN M. HALL, P.S.*

Seattle, Washington 98101 G. RICHARD HILL

(206) 447-4400

1900 Washington Building

Seattle, Washington 98101

(206) 682-8770

Foster, Pepper & Riviera

Special Counsel for all

School District Plaintiffs

DAVID J. BURMAN

Perkins, Coie, Stone,

Olsen & Williams

Special Counsel for Seattle

School District No. 1

♦Counsel of Record

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does a state statute—Initiative 350—requiring

assignment of students to the nearest or next-nearest school

embody a suspect racial classification when it contains

exceptions for all common forms of student assignment

except racial desegregation, specifically prohibits all means

of desegregation other than transfers at students’ option,

and concededly was enacted to terminate a school district’s

mandatory desegregation program?

2. Does substantial evidence support the finding by the

District Court, after nine days of trial that created over 2000

pages of transcript and over 250 exhibits, that discriminatory

purpose was a factor in the adoption of Initiative 350?

3- Does a state’s prohibition of local school districts’

assignment of students to non-neighborhood schools for

desegregation, except where ordered by a court, interfere

with satisfaction of the affirmative federal duty to

desegregate?

4. Does protection of the constitutional rights of school

children by school districts, school board members, and

private citizens constitute a special circumstance rendering

an award of attorney’s fees unjust?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Jurisdiction...................................................................... 1

(

Statement of the Case.............................................................1

A. Introduction................................................ 1

B. Historical Background ............................. 2

C. The Seattle Plan ....................................................4

D. Origin and Passage of Initiative 350............ 7

E. The Initiative 350 Lawsuit......................... 10

F. The District Court’s Decision........................... .10

G. The Court of Appeals’ D ecision.........................12

Summary of Argument................................................... 14

Argum ent................................................................................16

A. Initiative 350 Embodies a Racial

Classification Disadvantaging

M inorities...............................................................16

1. Hunter and Lee ....................................... 16

2. Initiative 350’s Race-Consciousness . . 18

3. Overt v. Covert Classifications..............21

4. Necessity of Further Proof of Purpose 23

5. Conclusion..................................................24

B. Discriminatory Purpose Was a Factor In

Intitiative 350’s Adoption ................... 25

1. Segregative Im p a ct.................................25

2. History and Context of the Initiative’s

A doption ................................ . . . . . . . 27

3. Lack of Relationship Between Means

and Permissible E n d s .............................30

4. Subjective M otivation............................ 32

5. Conclusion................... 34

11

Ill

C. Initiative 350 Deters Satisfaction of

the Affirmative Duty to Remedy Past

Segregation............................................................ 34

1. The Affirmative Constitutional Duty .35

2. Necessity of “ Busing” ............................ 36

3. The “ Saving” Construction of

Initiative 350 ........................................... 38

4. Initiative 350 Is Facially Overbroad . 41

5. Initiative 350 Is Preempted By

Federal Legislation .................................42

6. Conclusion................................................. 44

D. The Court of Appeals Correctly Found

the Successful School District Plaintiffs

Entitled to Their Costs and

Attorney's Fees .................................................... 44

1. Statutory Bases for Award of

Attorney’s F e e s .......................................45

2. An Award of Fees Serves the

Congressional Purposes.......................... 46

3. No Special Circumstances Exist Here . 47

4. An Award Is Due Other Plaintiffs . . . 49

j

Conclusion .................................. 50

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Ambach v. Norwick, 441 U.S. 68 (1979)......................... 27

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964)....................... 19

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(1977)....................14,24,25,28,30,32,33,34

Armstrong v. Board o f School Directors, 616 F.2d

305 (7th Cir. 1980)................................................ .37

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 (1964)............. .41

Board o f Education v. Harris, 444 U.S. 130

(1979)............................................................. .43,44

Brandenburger v, Thompson, 474 F.2d 885

(9th Cir. 1974) ........................................ .49

Brown v. Board o f Education (I), 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ....................................................... ............ 22,26,35

Brown v. Board o f Education (II), 349 U.S. 294

(1955) .............................................................................. 36

Brown v. Califano, 627 F.2d 1221 (D.C. Cir. 1980) . . . .34

Buchanan v. Evans, 423 U.S. 963, aff'g

mem. 393 F. Supp. 428 (D. Del. 1975).................21,22

Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247 (1978)....................... .46,48

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) . . . . . . . . 20,22

Citizens Against Mandatory Bussing v.

Palmason, 80 Wash. 2d 445,

495 P.2d 657 (1972) ...................................... . . . .3,29

iv

V

Columbus Board o f Education v. Penick, 443

U S. 449 (1979)............................................... 4,26,35,37

Comstock v. Group o f Institutional Investors, 335

U.S. 211 (1948).............................................................. 36

Cort v. Ash, 422 U.S. 66 (1975)........................................ 29

Crawford v. Board o f Education, No. 81-38...................37

Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 (1970)......................42

Dawson v. Pastrick, 600 F.2d 70

(7th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 450

U.S. 919 (1981)........................................................46-47

Dayton Board o f Education (I), 433 U.S. 409 (1977). . .35

Dayton Board o f Education v. Brinkman (II),

443 U.S. 526(1979)............................................. 4,35,37

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 82 Wash. 2d 11,

507 P.2d 1169 (1973), vacated as moot,

416 U.S. 312 (1974)..................................................24,25

Dennis v. Chang, 611 F.2d 1302 (9th Cir. 1980). . . .47,48

Department o f Revenue v. Hoppe,

82 Wash. 2d 549, 512 P.2d 1094 (1973) .................21

Donaldson v. O'Connor, 454 F. Supp. 311 (N.D.

Fla. 1 9 7 8 ).......................................................................47

Fleming v. Nestor, 363 U.S. 603 (1960 ).......................... 33

Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U.S. (6 Cranch) 87 (1810)................32

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980 )....................43

Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518 (1972).......................... 41

Goss v. Board o f Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) 19

Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co.,

336 U.S. 271 (1949)............................................... 2

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) . . .36

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915) ...........22,23

Hall v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1 (1973).................................... .. . .47

Hines v. Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 52 (1941 )....................... 44

Howard v. Illinois Central R.R., 207 U.S. 463 (1908) . .39

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385

(1969)....................................11,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978)................... .. .48

Incarcerated Men o f Allen County Jail v. Fair,

507 F.2d 281 (6th Cir. 1974)................... ...................47

James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137 (1971)......................... 21

Jenkins v. Anderson, 447 U.S. 231 (1980) ..................... 29

Kasper v. Edmonds, 69 Wash. 2d 799,

420 P.2d 346 (1966).................................... ................ 39

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973) . . . .4

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)........ 22

Kramer v. Union Free School District No. 15, 395

U.S. 621 (1969)..............................................................28

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939)............................ .22

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974 ).............................. 42

Vll

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)......................... 19,24

Lund v. Affleck, 587 F.2d 75 (1st Cir. 1978 ).................47

Lynch v. Overholser, 369 U.S. 705 (1962)....................... 39

Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122 (1980)..............................49

»

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971).................4,18,42

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964).............19,22

Mid-Hudson Legal Services, Inc. v. G & U, Inc.,

578 F.2d 34 (2d Cir. 1978) ..........................................47

Milliken v. Bradley (I), 418 U.S. 717 (1974)....................36

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530 F.2d 401

(1st Cir.), cert, denied, 426 U.S.

935(1976)....................... 35

NAACP v. Medical Center, Inc., 657 F.2d 1322

(3d Cir. 1981 )................................................................ 43

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S.

400 (1968).......................................................................46

New York City Transit Authority v. Beazer, 440

U.S. 568 (1979)..............................................................42

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v. Carey, 447 U.S.

54 (1980).........................................................................46

North Carolina State Board o f Education

v. Swann, 312 F. Supp. 503 (W.D.N.C. 1970),

aff'd,402 U.S. 43 (1971)....... 17,36,37,39,41,42

Northcross v. Board o f Education,

412 U.S. 427 (1973)......................................................46

via

Nyquist v. Lee, 402 U.S. 935 (1971),

aff'g mem. 318 F. Supp. 710

(W.D.N.Y. 1970).................. 11,16,17,18,19,21,23,24,29

Ohio ex rel. Eaton u. Price, 360 U.S. 246 (1959).......... 17

Orr v. Orr, 440 U.S. 268 (1979)........................................ 31

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583 (1883) ............................19

Personnel Administrator o f Massachusetts v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256 (1979)............................... .22,23,24,25,32

Railway Express Agency, Inc. v. New York, 336

U.S. 106 (1949)...............................................................31

Regalado v. Johnson, 79 F.R.D. 447 (N.D. 111. 1978) . .47

Regents o f the University o f California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978)....................................... 23,25,42-43

Rodriguez v. Taylor, 569 F.2d 1231 (3d Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 436 U.S. 913 (1978)................. ........... 47

San Antonio Independent School District v.

Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973 )..................................... 28

Schad v. Borough o f Mount Ephraim,

452 U.S. 61 (1981).......... 41

Seattle School District No. 1 v. State, 90 Wash.

2d 476, 585 P.2d 71 (1978) ................................... 27,29

Seattle School District No. 1 v. Washington,

No. C81-276T (W.D. Wash. Dec. 18, 1981).............38

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940).................................33

State ex rel. Citizens Against Mandatory Bussing v.

Brooks, 80 Wash. 2d 121, 492 P.2d 536

(1972)................................................................... 28

IX

State ex rel. Day v. Martin, 64 Wash. 2d 511, 392

P.2d 435 (1964).......... .................................................. 40

State ex rel. Public Disclosure Commission v. Rains,

87 Wash. 2d 626, 555 P.2d 1368 (1976) .................21

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880).............22

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971)....................... 4,18,27,36

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950)........................... 27

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Ass'n, 517

F.2d 1141 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 5 )...........................................47

United States v. Board o f Education, 88

F.R.D. 679 (N.D. 111. 1980).........................................37

United States v. Carolene Products Co.,

304 U.S. 144 (1938)......................................................28

United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968)...............32

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board o f

Education, 407 U.S. 484 (1972)................................ 35

Vance v. Bradley, 440 U.S. 93 (1979)............................. 24

Vlandis v. Kline, 412 U.S. 441 (1973).............................. 27

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229

(1976)..........................................................21,22,23,24,25

Washington v. Washington State Commercial

Passenger Fishing Vessel Association,

443 U.S. 658 (1979)........................................... 39,43-44

Wright v. Council of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972) . . .35

X

Constitutional Provisions

U.S. Const, amend. X I V .................................10,14,16,45,46

i

U.S. Const, amend. X V ........................................................ 23

Statutes

Akron City Charter § 137.................................................... 16

N.Y. Educ. Law 3201(1) (McKinney 1970)...................... 17

Pub. L. No. 95-561 .............................................................. 45

20 U.S.C. § 1617 ................................................................... 45

20 U.S.C. §§ 1713-14 (1976).................................. ............ 37

20 U.S.C. § 1716 (1976)........................................................ 37

20 U.S.C. § 3193(b) (Supp. I l l 1979)..................... 43

20 U.S.C. § 3192(b)(2) (Supp. I l l 1979)...............................44

20 U.S.C. § 3205 (Supp. I l l 1979) ...............................45,46

28 U.S.C. § 1254(2) (1976)....................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 1983 (1976).................................... 45,46

42 U.S.C. § 1988 (1976)............................................ .45,46,49

42 U.S.C. § 2000d (1976),........................................ .3,42

42 U.S.C. § 2000d-6 (1976)..................................................43

42 U.S.C. § 2000h-2 (1976)..................................................10

42 U.S.C. § 2000h-4 (1976).................................. .43

XI

Rules and Regulations

34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(l)(iii) (1981) ......................................43

34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(2) (1981)............................................ 43

Other Authority

Abernathy, Title VI and the Constitution:

A Regulatory Model for Defining

“Discrimination," 70 Geo. L.J. 1 (1981 )...............43

G. Allport, The Nature o f Prejudice (1954) ...................33

Bell, The Referendum: Democracy ’s Barrier

to Racial Equality, 54 Wash. L.

Rev. 1 (1978)................................................................. 28

Brest, The Supreme Court, 1975 Term—Foreward:

In Defense o f the Antidiscrimination

Principle, 90 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1976)....................... 33

Conf. Rep. No. 798, 92d Cong. 2d Sess. (1972 ).............26

Ely, Legislative And Administrative Motivation

in Constitutional Law, 79 Yale L.J.

1205 (1970)............................................ '. .................... 32

J. Ely, Democracy and Distrust (1980)........................... 24

/

H. R. Rep. No. 94-1558 (1976)................................... 46,49

12 Moore's Federal Practice § 435.01[2] (1981 )............ 45

Proposed Bills on Court Ordered School

Busing—Hearings on S. 528, S. 1147, S. 1647,

& S. 1743 before the Subcomm. on Separation o f

Powers o f the Senate Comm, on the Judiciary,

97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981)......................................13

Xll

S. Rep. No. 94-1011....................................................46,47,48

A. Siqueland, Without a Court Order—The

Desegregation o f Seattle's Schools (1981)...............13

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Public Knowledge

and Busing Opposition (1973) ...................................31

V

No. 81-9

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1981

STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

SEATTLE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

JURISDICTION

Appellants improperly invoke this Court's jurisdiction

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(2) (1976), as to Appellants’ Question

VIII. See note 44 infra.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Introduction

This statement is drawn from the District Court's findings

of fact, 473 F. Supp. 996, J.S. A-l to A-36 (W.D. Wash. 1979),

which the Court of Appeals left wholly undisturbed and in

many particulars expressly affirmed, 633 F.2d 1338, J.S. B-l

2

to B-29 (9th Cir. 1980), and from the evidence consistent with

those findings. Appellants state as facts many of their

contentions rejected by the courts below.1 Because they have

failed to raise any “ very obvious and exceptional showing

of error,” however, this Court should not depart from its

steadfast refusal to review such factual findings. Graver

Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 336 U.S. 271

(1949).

B. Historical Background

The Seattle, Tacoma, and Pasco public school districts

have determined that racial desegregation is an important

educational goal. The overall education of students in a school

system suffers when schools are segregated, and the adverse

effects fall most heavily upon minority students. The greater

the racial imbalance, the greater the impairment. 473 F.

Supp. at 1001 and 1011, J.S. at A-7 and A-25 (Findings of

Fact Nos. 3.1 and 3.1(a) (hereinafter, e.g., “ FF 3.1” )). Since

the early 1960’s, these public school districts have taken

steps to reduce school segregation. Id. at 1002-03 and

1005-07, J.S. at A -8 to A-10 and A-14 to A-18 (FF 3.8, 4.3,

5.1, 6.1, and 6.12). Tacoma and Pasco have assigned students

to other than their “ neighborhood” schools for many years.

Id. at 1002-04, J.S. at A-9 to A-13 (FF 4.3, 4.4, 5.1, and 5.14).

Because the antibusing statute in question arose mainly

in opposition to effective desegregation in Seattle, events

there must be recited in some detail. Segregated housing

patterns in Seattle result in segregated schools under even

a noninvidious neighborhood school assignment policy. Id.

at 1007, J.S. at A-18 (FF 6.14). During the 1960’s and 1970’s,

the minority residential areas expanded, and racial imbalance

in the schools increased. Id. at 1006, J.S. at A-17 (FF 6.8);

J.A. 75-83 and 144-50; Def. Ex. A-97.

1 Contrary to its present contentions, the United States informed the

courts below that the District Court’s findings accurately reflected the

facts.

3

In 1971, after eight years of limited success with voluntary

desegregation transfers, the locally elected Seattle School

Board adopted a mandatory middle school desegregation

program as a back-up to continued voluntary efforts.

Litigation delayed implementation of that program until fall

1972.1 2 The program also prompted a nearly successful effort

to recall four board members. Id. at 1002 and 1006, J.S. at

A-8 and A-16 (FF 3.10 and 6.3).

Until the 1978-79 school year, Seattle employed no

additional mandatory desegregation strategies, and school

segregation increased, except in the middle schools. During

1976-77, the District planned and publicized a voluntary

“ magnet” school desegregation program, which was carried

out in 1977-78. It successfully attracted some new student

movement, but much of that movement was not

desegregative. Id. at 1006, J.S. at A-16 to A-17 (FF 6.5, 6.6,

and 6.8); J.A. 111.

/

In early 1977 several organizations, including intervenor-

plaintiffs American Civil Liberties Union, National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and

Church Council of Greater Seattle threatened legal action

to force Seattle to desegregate. In April 1977 the NAACP

filed a complaint with the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) of

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, charging

the District with violating Title VI, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d (1976),

by maintaining purposefully segregated schools. 473 F. Supp.

at 1005-06, J.S. at A-15 (FF 6.1). OCR scheduled an

investigation.

In May 1977 the Mayor of Seattle and the presidents of

the local Chamber of Commerce, Municipal League, and

Urban League urged the Seattle School Board to adopt a

definition of racial isolation and a commitment to its

elimination by a time certain. J.A. 139-40. This broad support

for locally controlled desegregation was consistent with the

1 Citizens Against Mandatory Bussing v. Palmason, 80 Wash. 2d 445,

495 P.2d 657 (1972).

4

Board’s belief as to its educational, moral, and legal duty,3

and was an important factor in the Board’s June 1977

adoption of a resolution defining segregation {i.e., “ racial

imbalance’ ’4) and directing its elimination by autumn 1979

through use of educationally sound strategies. J.A. 49-50.

The Board further directed a six-month public planning

process. 473 F. Supp. at 1006, J.S. at A-17 (FF 6.9); J.A.

136-38. In July 1977 the Board established equity of

movement (i.e., roughly equal numbers of minority and

majority students mandatorily assigned to non-neighborhood

schools) as an essential feature of acceptable plans. J.A. 127.

C. The Seattle Plan

On December 14, 1977, after a lengthy public process,

including analysis of five model plans5 by a citizens’

3 The Board was well aware that there was some likelihood a court could

find unlawful segregation in Seattle. J.A. 12-13,16-17, 74, & 127. Although

unable and unwilling to examine the motives of its predecessors, the Board

was not unreasonable in its perceptions. Faculty assignment practices,

for instance, had been similar to those which numerous court decisions

have deemed to further schools’ racial identifiability. PI. Ex. 69. Other

historical factors, such as drawing of attendance boundaries and student

transfer policies, in some instances bore at least surface similarity to the

facts reported in Columbus Board o f Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979); Dayton Board o f Education v. Brinkman (II), 443 U.S. 526 (1979);

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973); and similar decisions.

4 The Seattle Plan’s goal to reduce racial imbalance is in no sense a “ racial

balance plan” directed at achieving the goal of “complete racial balance.”

Brief for United States at 5. No particular range or ratio of minority to

majority students is required. The percentage o f minority students in any

school may range from zero, i.e., no minority students, to 20% above the

districtwide minority percentage, provided that no single minority group

is more than 50% of a school’s student body. J.A . 50. This is a less

demanding desegregation goal than has been directed by numerous court

orders reviewed by this Court. E.g., Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 6-10 (1971). See also McDaniel v. Barresi,

402 U.S. 39, 41 (1971).

The Washington State Board of Education and Washington State

Human Rights Commission have adopted the same definition of “ racial

isolation” and have stated it to be public policy to eliminate such “ racial

isolation” by whatever means necessary. 473 F. Supp. at 1002, J.S. at

A-8 (FF 3.11); J.A. 65-69.

5 Each of the plans relied heavily on mandatory student assignments,

either as an initial strategy or as a backup to voluntary strategies. As

Board member Cheryl Bleakney testified, the public, while preferring

voluntary plans if possible (as aid the Board), repeatedly expressed the

desire for stability and predictability in student assignment patterns. J.A.

126-31.

5

committee and over 30 public hearings, the Board by a vote

of six to one adopted the Seattle Plan for school

desegregation. 473 F. Supp. at 1007, J.S. at A-17; J.A.

141-44. The Plan, which contains elements of several of the

model plans, desegregates elementary schools by “ pairing”

and “ triading” minority with majority elementary school

attendance areas. Thus, the Plan assigns individual students

not on the basis of their race (as in some mandatory and most

voluntary plans), but together with all other students in then-

attendance area. Secondary schools are desegregated by

restructured feeder patterns from elementary, to middle, to

high schools.

Students thus remain, if they choose, with other students

from their immediate neighborhoods in established patterns

from grade school through high school. Any inconvenience

is equitably distributed, with roughly equal numbers of

minority and majority students mandatorily reassigned.

Students subject to mandatory assignments spend roughly

half of their school years near their homes.6

Although the mandatory aspects of the Plan were

necessitated by the failure of 15 years of mostly voluntary

efforts, the Plan retains as much opportunity for voluntary

transfers as in a “ voluntary-first” program. 473 F. Supp. at

1007, J.S. at A-17 to A-18 (FF 6.11). Because “ voluntary-

first” strategies have inherently unpredictable results at the

individual student and individual school levels, primary

reliance upon them would have required constant

readjustments and last-minute resort to virtually random

mandatory assignments made purely on the basis of

individual students’ race, as the Board learned from its

experience with the middle schools program. J.A. 88. It is

wasteful and self-defeating to make mandatory “ backup”

assignments of students to programs which have been

6 The length of bus rides under the Seattle Plan was kept to a minimum.

The average "mandatory” bus ride in Seattle is 35 minutes, with 45

minutes maximum. The average “ voluntary” bus ride is 40 minutes, with

60 minutes maximum. Roughly half of all students in Seattle take buses

to school. Somewhat over half of those students do so as part of the Seattle

Plan, with fewer than half of those moving mandatorily.

6

uniquely designed to attract'students with special interests

or talents. The “ mandatory-first” plan based on pairs and

triads permits predictability and stability over time, and has

important educational and practical advantages, without

sacrificing voluntary opportunities. J.A. 130.

Voluntary programs and transportation are considerably

more expensive than mandatory. With the mandatory

assignment patterns of the Seattle Plan, a bus can fill up

with children at a few central stops in a neighborhood and

can take them all directly to the same destination; voluntary

student movement is widely scattered and transportation

correspondingly far less efficient. J.A. 72. Magnet programs

rely on expensive staff, programs, supplies, equipment,

publicity, and annual recruiting efforts to attract students.

State statutes limit the funds that may be raised by special

local property tax levies to spend on such programs. Further,

even assuming whites would volunteer in substantially

increased numbers, Seattle’s minority-area schools lack

capacity to absorb enough white students to desegregate,

especially since even greater numbers of minority volunteers

“ out” could not be expected while programs were being

enhanced to attract whites. J.A. 120-31.

As the undisputed testimony of black Seattle School Board

member Dorothy Hollingsworth and black community

leaders established, J.A. 93-96, 191-93, and 196-98; Tr.

218-25, the Board’s adoption of the Seattle Plan was the

realization, through the local political process, of important

minority educational and political goals. Because a voluntary-

only plan under Initiative 350 would destroy the Seattle

Plan’s equity of movement, minority volunteers would

significantly decline from previous levels in reaction to the

white community’s repudiation of desegregation. 473 F.

Supp. at 1007, J.S. at A-18 (FF 6.16); J.A. 94-95,191-93, and

196-98; Tr. 218-25 and 445-55.7

7 This would cripple voluntary desegregation strategies, which rely for

their limited success upon a disproportionately high level of minority

student transfers. 473 F. Supp. at 1006 & 1010, J.S. A-17 & A-24 to A-25

(FF 6.7, 8.5, 9.1, 10.1, & 11.1).

7

D. Origin and Passage of Initiative 350

A group of citizens unsuccessfully sought to enjoin

adoption of the Seattle Plan, organized Citizens for Voluntary

Integration Committee (CiVIC), and then sought to enjoin

implementation of the Plan. 473 F. Supp. at 1007, J.S. at

A-18 to A-19 (FF 7.1-7.3).

CiVIC also drafted Initiative Measure No. 350 in direct

and sole reaction to the Seattle Plan’s “ forced busing.” 8 Id.

at 1001 and 1008, J.S. at A-6 and A-19 (FF 1.28, 7.4, and

7.9); see 633 F.2d at 1343 and n.2, J.S. at B-4. In composing

the antibusing initiative, the drafters wrote to all

Washington school districts for advice on providing

maximum flexibility for “ normal” operations, and then

satisfied all expressed concerns. 473 F. Supp. at 1008, J.S.

at A-19 (FF 7.8); Def. Ex. A-102; J.A. 102-04.9 The drafters

specifically prohibited all the mandatory desegregation

strategies of the Seattle Plan and all known mandatory

8 The president of CiVIC testified as follows:

Q Isn’t it then an accurate statement to say that Initiative 350

was designed specifically to stop the ... mandatory aspect of

the Seattle Plan or any other mandatory plan such as Seattle

or other school districts might adopt?

A That’s extremely accurate.

J.A. 168.

9 As to transportation of students for all reasons except desegregation,

the legislative co-chair of CiVIC testified: “ (W]e tried to cover those in

our exceptions.” J.A. 189. This CiVIC leader’s testimony is instructive,

especially since it was taken in one of the earlier lawsuits, soon after the

initiative was developed, and long before this litigation alerted the

initiative’s proponents to the danger of acknowledging that the initiative's

only target was mandatory desegregation: “ It was our goal to make this

initiative as flexible as possible not to interfere with the development of

any program in any school district except where they might use

mandatory busing.” J.A. 188-89.

8

alternatives. 473 F. Supp. at 1010, J.A. at A-24 (FF 8.3-8.6).10

The State agrees that “ opponents of the plan . . . drafted,

filed, solicited signatures for and campaigned for passage

of Initiative Measure No. 350___ ” Brief of Appellants at 4.

The terms “ busing,” “ forced busing,” and “ mandatory

busing” in connection with Initiative 350 were synonomous

with busing for desegregation. 473 F. Supp. at 1009, J.S. at

A-21 to A-22 (FF 7.22); Tr. 77-78, 265-66, 349-51, 662, and

715; PI. Ex. 2, Tr. 22. There is a conscious or subconscious

racial factor in at least some opposition to “ forced busing.” 11

CiVIC’s campaign to secure the signatures necessary to place

the initiative on the ballot assured that it would affect only

“ forced busing” and not “ traditional” student assignment

policies of local districts. 473 F. Supp. at 1008, J.S. at A-21

(FF 7.18). That campaign made clear that the purpose of

Initiative 350 was to stop Seattle’s mandatory desegregation

efforts. Id. at 1007-09, J.S. at A-19 to A-23 (FF 7.5, 7.14,

7.19, and 7.23); PI. Exs. 38-44 and 51-67.12

10 The president of CiVIC testified as follows:

Q Isn’t it true that [§ 3 of Initiative 350] was devised specifically

in response to the Seattle Plan in an effort to enumerate those

characteristics of the Seattle Plan which could not be utilized

as an indirect method of getting around the prohibitions of

Initiative 350?

A I ’d have to answer yes.

J.A. 168-69. The CiVIC co-chair, see note 9, supra, testified that the

prohibitions of § 3 were enumerated because

school districts who are committed to using mandatory bussing to

achieve racial integration might very well use another reason for—at

least state another reason, you see, for implementing that plan. They

might for instance, say that the pairing of schools offered a better

education when indeed their goal was really integration if the

initiative was directed strictly to a racial integration of schools.

If the initiative had been directed to its correcting racial

imbalance, if the initiative had said they may not use bussing beyond

the nearest or next nearest school to the purpose of correcting racial

imbalance, then a school district whose—whose goal might be the

integration of the schools could still adopt a pairing plan and say,

well, this plan isn’t really for integration, it is just to achieve better

education. I consider that a not very remote possibility.

J.A. 188-89.

11 J.A. 91-93, 100-04, & 154-67.

12 For example, advertisements in major newspapers around the state

began: “ Initiative 350 was drafted in response to a desegregation plan

enacted by the Seattle school board.” PI. Ex. 38, p. 49, Tr. 486.

9

In July 1978 the election campaign began. CiVIC’s

spokespersons continued to maintain that the initiative

would affect only “ forced busing” for school desegregation,

and repeatedly stated that 99 percent of the State’s 300

school districts would not be affected by the initiative. 473

F. Supp. at 1008-09, J.S. at A-21 (FF 7.18-7.20). The three

the initiative would affect are plaintiffs in this action. Id.

(FF 7.19).

A voters’ pamphlet was mailed to all of the State’s

registered voters. The arguments for Initiative 350 by CiVIC

focused on “ forced busing.” PI. Ex. 2, Tr. 22. The arguments

against the initiative warned that the initiative would return

the Seattle; Tacoma, and Pasco public schools to segregation,

and made clear that the initiative arose in reaction to

Seattle’s desegregation program. 473 F. Supp. at 1008, J.S.

at A-20 to A-21 (FF 7.13 and 7.14). Both positions recognized

that the initiative had one direct and immediate objective:

halting desegregative non-neighborhood assignments in

Seattle.

The electorate passed Initiative 350 at the November 7,

1978, general election. In Seattle’s predominantly minority

37th Legislative District, the initiative failed. Id. at 1009,

J.S. at A-22 (FF 7.24 and 7.25).13

Initiative 350 permits local school districts to assign

students to other than their nearest or next-nearest schools

for all common reasons except desegregation. Id. at 1010 and

1013, J.S. at A-24 to A-25 and A-29 to A-30 (FF 8.3 and 8.8

and opinion).14 It permits a local community to obtain a

desegregated educational experience for its students only if

a court orders the school district to do so. Id. at 1011, J.S.

at A-25 (FF 8.9 and 8.10). The initiative would end the

13 The initiative also failed in the predominantly white 43rd District, which

is generally that area of Seattle joined since 1972 with the 37th District

in the mandatory middle school desegregation program.

“ Defendant State Superintendent of Public Instruction testified he was

unaware of any “ forced busing,” other than for desegregation, not

encompassed within the exceptions of the initiative. J.A. 96-97.

10

desegregation programs in Pasco, Tacoma, and Seattle and

prevent Seattle from eliminating racial imbalance. Id. at

1010, J.S. at A-24 to A-25 (FF 8.5, 9.1, 10.1, 11.1, and 11.2).

E. The Initiative 350 Lawsuit

Prior to Initiative 350’s effective date, the Seattle, Pasco,

and Tacoma School Districts, board members from those

districts, and several individuals as guardians of their

student children (the “ school district plaintiffs” ) brought suit

charging that Initiative 350 discriminated on the basis of

race in violation of state law, the Fourteenth Amendment,

and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and that the

State and the United States had caused purposeful

segregation that was reflected in Seattle’s schools. R. 1.

A number of parties intervened in the action. The local

intervenor-plaintiffs contended additionally that Seattle was

guilty of purposeful segregation and that if, as a result of

Initiative 350 or otherwise, the District did not voluntarily

desegregate, the court should order it to do so. The claims

that the State and the United States had caused unlawful

school segregation and that Seattle had not adhered to a

noninvidious school assignment policy in the past were

bifurcated for trial, if necessary, as Phase II of the litigation.

The United States intervened as a plaintiff under 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000h-2 (1976). CiVIC and several individuals intervened

as defendants.

F. The District Court’s Decision

After nine days of trial, producing over 2000 pages of

transcript and over 250 exhibits, the District Court

determined that it was

compelled to find Initiative 350 unconstitutional upon

several grounds: (1) it forbids mandatory student

assignments for racial reasons but permits such student

assignments for purposes unrelated to race, (2) a racially

discriminatory purpose was one of the factors whicn

caused Initiative 350 to be adopted, and (3) the initiative

is overly inclusive in that it permits only court-ordered

busing of students for racial purposes even though a

11

school board may be under a constitutional duty to do

so even in the absence of a court order.

473 F. Supp. at 1012, J.S. at A-27.

As to the first ground, the District Court relied primarily

upon Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969), and Nyquist

v. Lee, 402 U.S. 935 (1971), aff'g mem. 318 F. Supp. 710

(W.D.N.Y. 1970) (three-judge court). The only difference from

those cases was purely superficial. There, the laws expressly

prohibited or burdened efforts to remedy or protect against

discrimination; Initiative 350 prohibited for all purposes the

use of a technique necessary to remedy segregation, but then

created exceptions for every significant purpose other than

desegregation. "This is as effective a racial classification as

is a statute which expressly forbids the assignment of

students for racial balancing purposes.” 473 F. Supp. at 1013,

J.S. at A-30.

Under its second rationale, the District Court found that

it could not precisely ascertain the subjective intent of each

person who voted in support of Initiative 350, and that a

judgment could not be based upon what might be “ ‘safely

assume[d]’ as to the subjective intent of the voters.” Id. at

1014, J.S. at A-31. Consequently, the court relied primarily

upon circumstantial indicia of purpose. The court found that

Initiative 350 would result in a substantial increase in public

school segregation, that such an increase would damage the

education of minority children, and that this impact was both

a “ certainty” and a contemplated result of the initiative. Id.

at 1015, J.S. at A-33 to A-34. Moreover, the background and

context of the initiative made it clear that one significant

purpose of Initiative 350 was terminating effective

desegregation. The initiative forbids "every major effective

technique” of desegregation. Further, it was a “ marked

departure from the. . . norm” for "an administrative decision

of a subordinate local unit of government” to be "overridden

in a statewide initiative by voters, a great number of whom

were entirely unaffected by” the decision. Id. at 1016, J.S.

at A-35. That departure was even more telling in light of the

12

traditional local autonomy of school boards with respect to

the assignment of students. Id.

Third, the District Court held that Initiative 350

improperly applies on its face to a school district under an

affirmative constitutional duty to desegregate, leaving as

its only recourse “ litigation in order to have a court declare

the course of action that it should take.” Id. at 1016, J.S.

at A-36.

The school district plaintiffs incurred substantial

attorney’s fees and costs in the litigation—funds which would

otherwise have been available for educational purposes.

Nonetheless, the District Court refused to award attorney’s

fees to the school district plaintiffs on the grounds that the

public had already paid the fees. J.S. at C-2.

G. The Court of Appeals’ Decision

Despite successful implementation of the Seattle Plan, the

State sought review in the Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit. The State did not specifically dispute any of the

underlying facts found by the District Court. With one judge

dissenting, the Court of Appeals affirmed the conclusion that

Initiative 350 is unconstitutional, but reversed the District

Court’s denial of the school district plaintiffs’ motion for

attorney’s fees.

As to the constitutional issues, the Court of Appeals found

it necessary to discuss only the District Court’s conclusion

that Initiative 350 embodies an invidious racial classification,

agreeing with the District Court that Initiative 350 was

materially indistinguishable from the statute overturned by

this Court in Lee. 633 F.2d at 1342-43, J.S. at B-4 to B-5.

In short, “ Initiative 350 embodies a constitutionally-

suspect classification based on racial criteria because it

legislatively differentiates student assignment for purposes

of achieving racial balance from student assignment for any

other significant reason.” Id. at 1343-44, J.S. at B-5. If it

13

were to make a difference that the classification was covertly

rather than overtly embodied in the initiative, “ [lawmakers

who seek to establish impermissible racial classifications will

in the future be able to achieve, by artfully worded statutes

like Initiative 350, constitutionally forbidden goals.” Id. at

1344 and n.4, J.S. at B-6 to B-7.

As to attorney’s fees, the Court of Appeals held that

nothing in the plain language or legislative history of the

relevant statutes foreclosed or limited awards to publicly

funded plaintiffs. Id. at 1348, J.S. at B-14 to B-15. On the

contrary, such awards would further the congressional

purposes of encouraging vindication of constitutional rights

and stimulating voluntary compliance with the law. Id.

The Court of Appeals denied rehearing and rehearing en

banc, J.S. at E-l, and this Court subsequently noted probable

jurisdiction.

Now in its fourth year, the Seattle Plan has not only

successfully desegregated the public schools, but has done

so with significant community support and without violence

or racial tension.15 As the Court of Appeals noted, “ the

‘Seattle Plan’ in particular has been hailed as a model for

other large cities.” 633 F.2d at 1341, J.S. at B-l.

15 The Seattle Plan achieved its goal of elimination of racial imbalance

in 1979 and has maintained desegregated schools since. Desegregated

education has become institutionalized in Seattle. After extensive citizen

involvement, the School Board in February 1981 adopted a three-year

plan to maintain stable desegregated schools, again citing its “ legal and

educational duty.” For a current account of desegregation in Seattle, see

Proposed Bills on Court Ordered School Busing-Hearings on S. 528, S.

1147, S. 1647, & S. 1743 before the Subcomm. on Separation o f Powers

of the Senate Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) (October

16,1981, statement of Suzanne Hittman, Seattle School Board President).

For an historical account of development of the Seattle Plan, see A.

Siqueland, Without a Court Order—The Desegregation of Seattle's Schools

(1981).

14

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The District Court correctly recognized three ways in

which Initiative 350 violates the Fourteenth Amendment.16

If this Court finds support for any one of the bases of

unconstitutionality, as did the Court of Appeals, the

judgment must be affirmed.

First, Initiative 350 directly embodies an invidious racial

classification admittedly unsupported by any compelling

state interest. Designed to treat student assignments for

desegregation differently from all other student assignment

matters, it operates to maintain and increase segregation,

to inhibit equal educational opportunity, and to deny

(cont.)

Contrary to the “ conventional wisdom” that mandatory busing for

desegregation causes substantial “ white flight” and is therefore

counterproductive, white student attrition in Seattle has been roughly

the same in the four years of the Seattle Plan’s operation as it was in

the three years preceding the Plan. The white loss from predominantly

minority and transition areas, which is “ certain” with a neighborhood

assignment policy, has been reduced. See 473 F. Supp. at 1010-11, J.S.

at A-25 (FF 11.3). Test scores in Seattle have slightly improved; significant

improvements are expected in the longer term, consistent with the national

research. Moreover, even apart from test scores, a diverse student body

better prepares students for life in a pluralistic society. Thus, the

experience in Seattle is consistent with that nationwide, as shown by the

State’s own Ex. A-133, Tr. 1346 (Harris Poll) at pp. ix, x, and 40:

While there are whites who are still emotionally disturbed at

the notion of busing for racial balance, the almost automatic

claim that “ busing is a disaster” simply does not hold up in

the face of the facts from this study. . . . The irony of busing

to achieve racial balance is that rarely has there been a case

where so many have been opposed to an idea, which appears

not to work badly at all when put into practice. . . . Among

whites whose children have been bused for desegregation, 78%

say the experience is satisfactory or highly satisfactory.

“ Whether Initiative 350 violates the State Constitution was expressly

left unaddressed by the District Court. 473 F. Supp. at 1016, J.S. at A-36.

If the District Court and Court of Appeals were incorrect as to federal

law, the case should be remanded for application of state law and, if

necessary, for Phase II of the litigation. See Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 271 (1977).

15

minority interests. School operations in Washington have

traditionally been local matters, and only after adoption of

the Seattle Plan for desegregation did the voters of the State

as a whole .feel the necessity to dictate student assignment

policy in one narrow area to three local districts. In so doing,

Initiative 350 restructures the political process in a non

neutral manner by foreclosing to minorities the traditional

mechanism of influencing one’s local school board as a means

of attaining educational goals.

Second, the District Court’s finding that Initiative 350

purposefully discriminates against racial minorities is

compelled by the evidence. Prior to the election, it was well

known to the electorate that the initiative would end the

Seattle Plan and dramatically increase school segregation,

and that voluntary desegregation efforts had failed and

would fail again. The context and purpose of Initiative 350

was opposition to the Seattle Plan and effective school

desegregation. Discriminatory purpose was also reflected in

the procedural departure from the norm represented by the

first use of the statewide initiative process to deal with a

traditionally local school district matter in one area, racial

desegregation, and—by careful design—only in that area.

Further, the absence of a close relationship between the

antibusing initiative and any permissible purpose, as well

as evidence of subjective intent, both reflected discriminatory

purpose.

Third, Initiative 350 unconstitutionally interferes with the

affirmative duty of school districts to remedy past unlawful

segregation. It prohibits local school districts from assigning

students beyond their neighborhood schools, except pursuant

to court order, without regard to whether those local school

districts have or perceive a constitutional duty to

desegregate. Because the statute on its face is susceptible

of application to constitutionally required conduct, it is

invalid.

Finally, the Court of Appeals correctly held that the

successful school district plaintiffs are entitled to their costs

16

and attorney’s fees. Federal law requires such an award

unless special circumstances render it unjust. No such

circumstances exist here. Indeed, a denial of costs and fees

would mean that school board members must choose between

surrendering the constitutional rights of their students,

which they are sworn to uphold, or irreparably diverting

necessary funds from education.

ARGUMENT

A. Initiative 350 Embodies a Racial Classification

Disadvantaging Minorities

The Court of Appeals and the District Court properly relied

upon Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969), and Nyquist

v. Lee, 402 U.S. 935 (1971), aff'g mem. 318 F. Supp. 710

(W.D.N.Y. 1970), in concluding that Initiative 350 reflects

an invidious racial classification unjustified by any

compelling state interest.

1. Hunter and Lee

In Hunter this Court held that § 137 of the Akron City

Charter violated the Fourteenth Amendment. The charter

provision, which was added by a referendum, prevented the

city council from implementing, without the approval of a

majority of voters, any ordinance dealing with racial,

religious, or ancestral discrimination in housing. The

provision thus created “ an explicitly racial classification

treating racial housing matters differently from other racial

and housing matters.” Id. at 389. The Court pierced the

superficial neutrality of the provision: “ although the law on

its face treats Negro and white, Jew and Gentile in an

identical manner, the reality is that the law’s impact falls

on the minority.” Id. at 391. Applying the “ suspect

classification” test to the provision, the Court found that

none of Akron’s justifications amounted to a compelling state

interest.

Justice Harlan’s concurrence focused on § 137’s

restructuring of the political process in a racially

17

discriminatory manner: "Here, we have a provision that has

the clear purpose of making it more difficult for certain racial

and religious minorities to achieve legislation that is in their

interest." Id. at 395. Such a provision is “ discriminatory on

its face," and must fall “ unless it can be supported by state

interests of the most weighty and substantial kind." Id. at

393.

In Lee a three-judge court held Hunter dispositive as to

a New York statute prohibiting student assignments and

certain other actions “ for the purpose of achieving racial

equality in attendance.” 318 F. Supp. at 712. Like Initiative

350, the New York antibusing statute had the effect of

differentiating between racial matters and other problems

in the same area. Hunter, according to the court in Lee,

stands for the principle that “ the state creates an ‘explicit

racial classification’ whenever it differentiates between the

treatment of problems involving racial matters and that

afforded other problems in the same area." Id at 718. Because

the lower court’s sole stated rationale and any possible

alternative theories in Lee apply equally to Initiative 350,

this Court’s summary affirmance is controlling here. Ohio

ex rel. Eaton v. Price, 360 U.S. 246, 247 (1959).17

17 The United States contends that Lee may be explained on two grounds

that make it inapplicable here. First, it is said that the statute in Lee

“ clearly prohibited ‘all efforts to achieve racial balance’ (318 F. Supp. at

715)___ r' Brief at 25. Second, the statute in Lee prohibited race-conscious

assignments “ pursuant to a court finding of unconstitutional

segregation,” and thus this Court’s affirmance was governed by the

decision two weeks earlier in North Carolina State Board o f Education

v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971). Brief at 25-26 & n.27. Neither distinction

is satisfactory.

The statute in Lee, like Initiative 350, dealt only with desegregative

student assignments and related techniques. 318 F. Supp. at 712. If

anything, the prohibitions of Initiative 350 are broader in that § 3 prohibits

desegregative school pairing, merging, or clustering: desegregative grade

restructuring; and desegregative feeder schools. Neither the New York

statute nor Initiative 350 prohibited voluntary desegregation efforts. See

N.Y. Educ. Law 3201(1) (McKinney 1970). Thus, the Lee court’s comment

that the statute “ clearly applies to all efforts to achieve racial balance”

must have reflected only the court’s earlier conclusion that voluntary plans

18

2. Initiative 350's Race-Consciousness

As the Court of Appeals and the District Court recognized,

Initiative 350 is like the charter provision in Hunter and the

statute in Lee. It is race-conscious in its history and race-

related in its purpose and effect. The initiative draws a

distinction between those groups who seek the law’s

protection against racial discrimination in student

assignments and those who seek to regulate student

assignments in the pursuit of other ends. Compare Hunter,

393 U.S. at 390.

Initiative 350’s drafting and campaign history plainly

demonstrates the intention to limit student assignments for

desegregation, but not to limit any other assignments, as

is suggested by the very name of the proponents—Citizens

for Voluntary Integration Committee. In the course of

drafting, the exceptions to the “ nearest or next-nearest’ ’ rule

and the desegregation tools specifically prohibited were both

expanded. Although more artfully crafted than the statute

in Lee, the initiative was offered to, and accepted by, the

electorate as the most recent step in opposition to “ forced

busing,” i.e., effective desegregation. Compare 318 F. Supp.

at 716-17.

The law's purpose and effect plainly fall on the minority,

by dismantling local school desegregation programs,

preventing future adoption of such programs, injuring

educational achievement of minority students, and requiring

(cont.)

“ have not had a significant impact on the problems of racial segregation

in the Buffalo public schools; indeed it would appear that racial isolation

is actually increasing.” 318 F. Supp. at 715. That is precisely the situation

in this case, and the Justice Department’s attempted distinction merely

reemphasizes the applicability of Lee.

The same is true with respect to the second “ distinction.” There was

no “ court finding of unconstitutional segregation” in Lee. The statute

was struck down m its entirety, not just as applied to districts under court

orders to desegregate. Indeed, the district court in Lee specifically upheld

the personal standing of parents of children in schools suffering only from

“ de facto segregation,” which there is “ no constitutional duty to undo.”

Id. at 713-14. Thus, if Lee was directly controlled by the Swann cases,

it was by McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971), discussed infra at 41-42,

which upset state court interference with race-conscious student

assignments by a local district not acting under a “ court finding of

unconstitutional segregation.”

19

expensive and time-consuming litigation for the vindication

of constitutional rights. In Hunter, this Court noted that only

minorities need the protection of a fair housing law to halt

segregative housing choices by whites. 393 U.S. at 391. Here,

as in Lee, only minorities need the protection of a

desegregation plan to halt segregative school choices by

whites.

As in Hunter, the initiative specially burdens, indeed

forecloses, the attainment of important minority educational

and social goals through the local political process. In Hunter

local voters could still enact fair housing ordinances, but

Initiative 350 flatly prohibits local non-neighborhood

assignments for desegregation, absent a court order. The

requirement that any amendments to Initiative 350 be

adopted at the state, rather than the local, level effectively

removes from Seattle's minority community any realistic

hope of amendment. See note 28 infra.

The State asserts that there is no unique burden on

minorities for three reasons: First, the Seattle Plan reassigns

some members of all races, and terminating the Plan

necessarily affects them all. Second, many minority parents

dislike non-neighborhood assignments. Brief of Appellants

at 19-20. Third, the initiative might have some application

to assignments unrelated to desegregation. Id. at 10.

The first reason is merely the suggestion—repeatedly

rejected by this Court—that separate schools, separate

seating, antim iscegenation statutes, repeal of

antidiscrimination laws, and the like affect both blacks and

whites.18 The correct approach is shown by Goss v. Board

o f Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963), where the Court

" E.g., Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 8 (1967) (“ The mere fact of equal

application does not mean that our analysis of these statutes should follow

tne approach we have taken in cases involving no racial discrimi

nation -----” ); McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184,188 (1964) ("all whites

and Negroes who engage in the forbidden conduct are covered by the

section and each member of the interracial couple is subject to the same

penalty” ); Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399, 403 (1964) (fact that

candidates of all races must designate race on ballot does not remove

requirement’s “ purely racial character and purpose” ). The State is

apparently unaware that McLaughlin overruled Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S.

583 (1883).

20

unanimously held that “ [t]he alleged equality—which we view

as only superficial—of enabling each race to transfer from

a desegregated to a segregated school does not” remove the

action’s “ purely racial character and purpose.” Id. at 688.

The second reason is simply irrelevant. Everyone, including

the Seattle School Board, would prefer to accomplish school

desegregation in some other manner. Yet, the record in this

case establishes that mandatory non-neighborhood

assignments were essential to effective desegregation, and

that minority parents had invoked the local political process

and accepted some inconveniences to obtain desegregated

education. Even if minority leaders had opposed the Seattle

Plan, that would not justify a denial of the interests of other

minority children. See Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482

(1977); id. at 503 and n.2 (Marshall, J., concurring).

Third, in the hope of escaping the conclusion that the

initiative is a racial classification, the State strains to apply

it to nonracial student assignments. These situations, which

either do not occur in the real world or else fall within the

broad exceptions to the initiative,19 are nothing more than

after-the-fact speculation as to possible, unintended side

19 For instance, there is no evidence in the record that school districts

assign students to other than their nearest or next-nearest school to

“ balance class size.” The Spokane newspaper article (Ex. A-130) cited by

the State, Brief at 10 n.6, was successfully objected to as hearsay, and

was admitted only for the limited purpose of showing what was before

some voters prior to the Initiative 350 vote. Tr. 937. The witness through

whom the State wished to make its point testified that the only non

neighborhood busing in Spokane is due to “ overcrowding,” Tr. 934, which

of course is among the initiative’s exceptions.

The suggestion that districts would transport students away from

neighborhood schools simply to secure transportation reimbursement from

the State is likewise unfounded. In recent years the State has reimbursed

a substantial portion of, but far from all, local transportation expenses.

Because local districts must contribute their own resources to any

transportation, it is always a losing proposition financially.

21

effects of a measure designed to affect only racial matters.

Initiative 350 must be construed as repeatedly interpreted

by its sponsors.20 CiVIC consistently denied that the

initiative would affect anything but desegregation busing.

The State’s argument, that a statute which clearly and

admittedly was intended to deal with race relations can be

saved by additional but unanticipated impacts, stands

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), on its head.21

3. Overt v. Covert Classifications

The only difference between the statute here and that in

Lee is one of form and not substance. Initiative 350 was more

carefully drafted—and purposefully so. Thus, unless clever

language excuses the same objective as in Lee and Hunter,

Initiative 350 must be subjected to strict scrutiny.

That Hunter and Lee apply to artful as well as obvious

racial classifications is clear from Buchanan v. Evans, 423

U.S. 963, a ffg mem. 393 F. Supp. 428 (D. Del. 1975). In that

case, a statute directed officials to consider consolidating the

state’s school districts, with two exceptions, into a smaller

number of districts. The district court found the two

exceptions—Wilmington and districts with over 12,000

pupils—were intended to preclude desegregative

consolidations of other districts with the largely minority

Wilmington district. Although consolidating Wilmington

with other districts could still be accomplished by

referendum, although one other district was inadvertently

excluded by the 12,000-student provision, although there was

20 The basic rules of construction applicable to enactments of the

legislature also apply to direct legislation by the people. State ex rel. Public

Disclosure Commission v. Rains, 87 Wash. 2d 626, 633, 555 P.2d 1368,

1373 (1976). Determining the collective intent of the people is the objective,

and material in the official voters’ pamphlet is relevant. Department of

Revenue v. Hoppe, 82 Wash. 2d 549, 552, 512 P.2d 1094, 1096 (1973).

n Nor is the argument supported by James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137

(1971). The referendum at issue in James applied not to integrated housing

but to low-income housing, and the Court found no evidence that it was

in fact an inadvertently broad statute aimed only at race relations in

housing. Id. at 141. Here the critical fact of race-consciousness is openly

admitted.

22

no finding of an interdistrict constitutional violation, and

although the statute was “ racially neutral on its face,” the

district court found that the statute reflected “ a suspect

racial classification.” 393 F. Supp. at 442. This Court

affirmed summarily, with three Justices dissenting on other

grounds.

Concern with transparently race-conscious statutes did not

end with Evans:

This rule applies as well to a classification that is

ostensibly neutral but is an obvious pretext for racial

discrimination. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356;

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347; cf. Lane v. Wilson,

307 U.S. 268; Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339.

Personnel Administrator o f Massachusetts v. Feeney, 442

U.S. 256, 272 (1979). Such a racial classification is

presumptively invalid, regardless of any other proof of

motivation and regardless whether the classification is

“ covert or overt.” Id. at 274. Feeney is thus consistent with

the Court’s duty to strike down “ sophisticated as well as

simple-minded modes of discrimination.” Lane v. Wilson, 307

U.S. 268, 275 (1939).22

The courts below correctly concluded that Initiative 350

creates a racial classification. It is not the rare classification,

such as those in Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214

(1944), or Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880), that

expressly burdens only a racial minority. Nor is it a

classification, such as those in Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954); McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184

(1964); and Hunter, that mentions race, and race relations,

but does not expressly burden one race more than another.

22 The “ covert or overt” language in Feeney is also consistent with the

jury discrimination cases. In those cases, no classification is explicit on

the face of the law. Substantial underrepresentation in practice, however,

is sufficient to shift the burden to the state to rebut the suggestion of

discriminatory purpose. Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 494-95 (1977);

accord, Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. at 241. This case is an even clearer

one for shifting the burden since it is admitted that the law in fact deals

with racial matters.

23

Instead, it is a classification, such as those in Gomillion, Yick

Wo, and Guinn,23 all mentioned approvingly in Feeney, that

only transparently avoids the express mention of race and

race relations, but that undeniably deals with both.

4. Necessity o f Further Proof of Purpose

Finally, the State asserts that its appeal rests on the

proposition that after Washington v. Davis "courts are no

longer free to presume from the face of a given statute—as

was done in Hunter and Lee—that an illicit segregative

purpose motivated its passage.” Brief of Appellants at 23

(emphasis in original). The assertion that Davis overturned

Hunter and Lee is simply wrong. Race-conscious statutes—

such as those in Hunter, Lee , and this case—by their very

concern with racial matters create a risk that bias infected

the majority’s consideration of minority interests, at least

where they do not benefit the minority. Compare Regents

o f the University o f California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 357

(1978) (opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall, & Blackmun,

J.J.).24 Only the absence of any alternative means of

satisfying a compelling state interest is normally sufficient

to dispel that suspicion of antipathy.

Accordingly, Hunter was cited approvingly in Davis, which

went on to state “ [tjhat is not to say that the necessary

discriminatory racial purpose must be express or appear on

the face of the statute___ ” 426 U.S. at 241. The Court has

since made it clear that, because the statutes in Hunter and

the present case burden minorities and involve concern with

racial matters, they are not the kind of neutral laws with

23 In Guinn v. United States, for example, the Court struck down an

Oklahoma constitutional amendment that imposed a literacy test for

voting but grandfathered all those who had voted in 1866 and their lineal

descendants. Because the 1866 election was the last major election before

adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment, the Oklahoma scheme covertly

reflected a racial classification. 238 U.S. at 364. Initiative 350 is equally

clever, but equally obvious.

24 Contrary to the Bakke situation, where the governmental benefit to

the minority is at the expense of the majority, elementary and secondary

school desegregation deprives no one of the benefit of an education.

24

inadvertent impact authorized by Davis. As the Court stated

in Feeney: “ Certain classifications, however, in themselves

supply a reason to infer antipathy. Race is the paradigm.

A racial classification, regardless of purported motivation,

is presumptively invalid and can be upheld only upon an

extraordinary justification.” 442 U.S. at 272.

If Davis, which involved no express or implicit race-

consciousness and no allegation by plaintiffs of

discriminatory purpose, and Arlington Heights, which

involved no express race-consciousness and insufficient proof

of implicit consideration of race, overturn Hunter and Lee,

then this Court and others must seek out direct evidence of

racial prejudice in every case. It has always been enough to

invoke strict scrutiny that the majority was dealing, overtly

or covertly, with matters that present an inherent risk of

antipathy toward minority interests. See Vance v. Bradley,

440 U.S. 93, 97 (1979). That risk is sufficient to shift to the

State the burden of dispelling the inference of prejudice,

usually by establishing “ an extraordinary justification” for

the action. See Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 9-11 (1967);

J. Ely, Democracy and Distrust 145-48 (1980). Any other rule

would place the courts in the unnecessary and unwise

position of protecting minority interests only by directly

accusing other branches of government of racial prejudice.

5. Conclusion

The Court cannot fail to recognize the potential for the

corruptive influence of prejudice in a decision whether to

allow desegregation. No other proof of invidious purpose is

necessary. Instead, the burden should shift to the State to

show, for example, that the State interest was sufficiently

compelling, and the sacrifice of desegregation sufficiently

necessary, to outweigh the potential for corruption. That is

a burden the State never even attempted to satisfy. Instead,

the initiative contradicts the “ compelling” state interest in

public school desegregation. DeFunis v. Odegaard, 82 Wash.

25

2d 11, 35, 507 P.2d 1169, 1184 (1973), vacated as moot, 416

U.S. 312 (1974).25

B. Discriminatory Purpose Was a Factor In

Initiative 350’s Adoption

Even if the covert but conceded race-consciousness of

Initiative 350 were not enough to invoke strict scrutiny, the

District Court correctly concluded, under the second prong

of Feeney, that a discriminatory purpose was at least one

factor in the proposal and adoption of the initiative.

In Arlington H eights v. M etropolitan Housing

Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977), the Court reviewed

some of the important indices of whether a governmental

action is im perm issibly infused with purposeful

discrimination:

(a) “ The impact of the official action—whether it ‘bears

more heavily on one race than another,’ Washington v.

Davis, supra, 426 U.S. at 242—may provide an

important starting point.”

(b) “ The historical background of the decision,”

including the “ specific sequence of events leading to the

challenged decision” ana procedural and substantive

departures from the norm in connection with the

decision, is important circumstantial evidence.

(c) Finally, the “ legislative or administrative history”

of the decision may provide direct evidence of purpose

and of subjective intent.

Id. at 266-68. Substantial evidence, ignored by the State,

supports the District Court’s conclusion that Initiative 350

is purposefully segregative under Arlington Heights.

1. Segregative Impact

The dramatic increase in minority racial isolation that

Initiative 350 would have caused was fully foreseen, not just

25 Initiative 350 makes impossible attainment of public schools’ legitimate

educational goal of racially diverse student bodies. The institutional

interest in diverse student bodies is not only legitimate but is one aspect

of academic freedom protected by the First Amendment. Regents o f the

University o f California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 311-15 (1978) (Powell, J.).

26

easily foreseeable. See Columbus Board o f Education v.

Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 464-65 (1979). Both lower courts

concluded that Initiative 350 was directed only at racial

desegregation. 473 F. Supp. at 1010, J.S. at A-24 (FF 8.3);

633 F.2d at 1343-44, J.S. at B-5 to B-6. Both courts found

it would be impossible to desegregate Seattle’s schools

without resort to the methods prohibited by the initiative.

473 F. Supp. at 1010, J.S. at A-24 (FF 8.5); 633 F.2d at 1346,

J.S. at B -ll. Moreover, the inconvenience of desegregation

would no longer have been shared equitably. Rather, the

limited desegregation obtainable under Initiative 350 would

result largely from efforts of minority students. 473 F. Supp.

at 1006-07, J.S. at A-16 to A-18 (FF 6.6, 6.7, and 6.16).

Further, the District Court below concluded that the racial

isolation under Initiative 350 would disproportionately injure

the education of minority students. Id. at 1001, 1011, and

1015, J.S. at A-7, A-25, and A-33 (FF 3.1, 3.1(a)); see 633 F.2d

at 1346-47, J.S. at B-9 to B-13.26 That same finding as to both

purposeful and non-purposeful segregation by the district

court in Brown v. Board o f Education was adopted by this

Court: “ Segregation of white and colored children in public

schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children.

The impact is greater when it has the sanction of