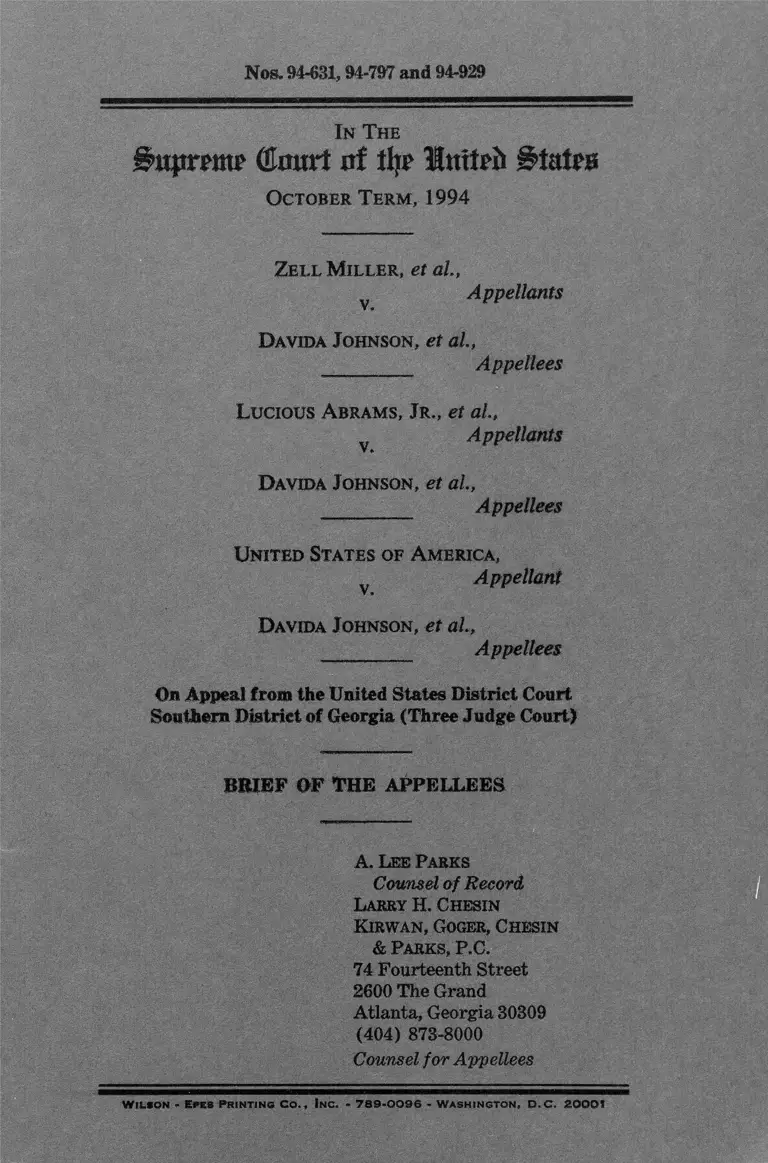

Miller v. Johnson Brief of the Appellees

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Miller v. Johnson Brief of the Appellees, 1995. 64020ab2-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4ab32e4e-a4d3-493b-8eb4-4ed87ff189d1/miller-v-johnson-brief-of-the-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 94-631,94-797 and 94-929

In T he

B’ujtrmr (Smart nf % Ittitefc Stairs

October T erm , 1994

Zell M iller, et a l,

y Appellants

D avida Johnson, et al,

________ Appellees

Lucious A brams, Jr ., et al.,

Appellants

V *

D avida Johnson, et al,

Appellees

United States of A merica,

y Appellant

D avida Johnson, et a l,

________ Appellees

On Appeal from the United States District Court

Southern District of Georgia (Three Judge Court)

BRIEF OF THE APPELLEES

A. Lee Parks

Counsel of Record

Larry H, Chesin

Kirwan, Goger, Chesin

& Parks, P.C.

74 Fourteenth Street

2600 The Grand

Atlanta, Georgia 30809

(404) 873-8000

Counsel for Appellees

W ilso n - Ep e s p r in t in g Co . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n , d .C . 8 0 0 0 1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether Appellants have carried their burden of prov

ing the District Court’s determination that the Eleventh

District is the product of racial gerrymandering is

clearly erroneous?

2. Whether the legislation creating the Eleventh District

is subject to strict scrutiny?

3. Whether the State abandoned any constitutional de

fense of the District by its failure to articulate any

compelling state interest furthered by the intentional

use of racial classifications in its creation?

4. Whether Intervenors may advance compelling state

interests to purportedly justify racial gerrymandering

where the State expressly denies it was so motivated?

5. Assuming the Court accepts one of the proffered

rationalizations for the gerrymandering as a compelling

state interest, whether the District Court correctly

determined the Eleventh District can not survive strict

scrutiny?

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ............................................ i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............. .........-.....-............- v

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........................................ 1

Georgia’s 1992 Redistricting Plan Creates Lines

Which Are Exceedingly Irregular ........... ................ 3

Race Was the Overriding Consideration in Geor

gia’s 1992 Congressional Redistricting Plan ------- 6

Georgia’s 1992 Redistricting Plan Makes a Mock

ery of Traditional Districting Principles ................ 11

The DQJ and the Demand for Maximization......... 18

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .......................................... 23

ARGUMENT...... .................. ....................................... -......- 25

I. PLAINTIFFS HAVE STANDING TO CHAL

LENGE RACIAL GERRYMANDERING IN

THEIR DISTRICT ............ ............................ -......... 25

II. THE DISTRICT COURT’S DETERMINATION

THAT THE ELEVENTH DISTRICT IS THE

PRODUCT OF RACIAL GERRYMANDERING

IS NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS .................... 29

A. Objective Criteria to Govern Application of

Shaw Already E x is t ......................................... 32

III. THE LEGISLATION ESTABLISHING THE

ELEVENTH DISTRICT IS SUBJECT TO

STRICT SCRUTINY ........ ..................................... 33

IV. THE ELEVENTH DISTRICT CANNOT SUR

VIVE STRICT SCRUTINY .................................. 37

A. Third Parties Cannot Supply Compelling

Governmental Interests Which The State

Refuses To Acknowledge........ 37

(iii)

IV

Page

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

B. The Lines of the Eleventh District Are Not

Arguably Necessary Under Section 5 Of The

Voting Rights Act ............................................. 39

C. The Lines of the Eleventh District Are Not

Arguably Necessary Under Section 2 Of The

Voting Rights Act ............................. ............... 43

D. The Desire To Redress The Unquantified Ef

fects of Historical Discrimination Is Not A

Compelling State Interest.................... 46

CONCLUSION ................... 50

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev.

Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977)............... - ..............34, 35, 36

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986)................. 28

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976).........- 40

Brooks v. Mississippi, 469 U.S. 1002 (1984).......— 47

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ___________ ._______________________ 24, 28

Busbee v. Smith, 549 F.Supp. 494 (D.D.C. 1982).. 40

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156

(1980).......- .................................................................. 30

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson, 488 U.S. 469

(1989) ..............................................................27, 34, 38, 39

Evans v. Abney, 396 U.S. 435 (1970) ..... .............. 28

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903 (1956) .................. 28

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 80 S.Ct. 669

(1960) ...................................................................... . 25, 35

Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075 (1993) .... 44

Hays v. Louisiana, 839 F. Supp. 1188 (W.D. La.

1993), vacated omd remanded, 113 S.Ct. 2731

(1994) ......... .................... ............... ....................... 26, 30, 33

Hernandez v. New York, 500 U.S. 352 (1991)----- 28

Holder v. Hall, 114 S.Ct. 2598 (1994) .................... 32, 50

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 (1955) ................. 28

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985).......... 35

Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S.Ct. 2647 (1994)....... 41,49

Katzenbach v. South Carolina, 383 U.S. 301

(1966) ................................. -............................... -...... 40

Kramer v. Union Free School Dist. No. 15, 395

U.S. 621 (1969) ......................................... .............. 38

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967).......... .......... 28

Mayor of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U.S. 877

(1955) ................ ......................................................... 28

Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971) ........... 28

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 16 S.Ct. 1138,

41 L.Ed.2d 256 (1896) ........................... - ...........- 25

Regents of the Univ. of Calif, v. Bakke, 438 U.S.

265 (1978) ......................................... -..................... 38,39

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) ....... ........... 30

Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994).. 26, 30,

36

V

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816 (1993) ......................'passim

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) ...30,31,43,44

United Jewish Orgs. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144

(1971) ......... ........................................................... 46,49

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333

U.S. 364 (1948) ................................ ...................... 31

Vera v. Richards, 861 F.Supp. 1304 (S.D. Tex.

1994) ........... .................................................... ........... 26

Voinivich v. Quitter, 113 S.Ct. 1149 (1993) ............ 37

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) _____ 36

White v. Register, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)___ _____ 30

Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52 (1964)........ 25, 31, 34

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. of Educ., 476 U.S. 267

(1986)........... ................ ........................... ............ ..27, 38, 39

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc.,

395 U.S. 100 (1969)............. ............................ ...... 31

CONSTITUTIONS

U.S. Const, amend. XIV (Equal Protection

Clause)............. .. .................... ....................................................................... . 1, 24, 34, 36, 38, 49

STATUTES

42 U.S.C. § 1973(a), § 1973(b), § 1973c ..... ..........passim

Ga. Code Ann. § 21-2-3 (1993) ......... .......................... 1

RULES

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 52a............... 30

MISCELLANEOUS

Blumstein, Defining and Proving Race Discrimi

nation: Perspectives on the Purpose v. Results

Approach from the Voting Rights Act, 69 Va. L.

Rev. 633 (1983) .......................................... ............ 28

Aleinkoff and Issacharoff, Race and Redistricting:

Draining Constitutional Lines A fter Shaw v.

Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 588, 589, n.8 (1993)....... 45

Brace, Grofman, Handley & Niemi, Minority Vot

ing Equality: The 65% Rule, 10 Law & Policy

(1988) ...................................... .................................. 45

Vll

Brace, Grofman, Handley, Does Redistricting

Aimed to Help Blacks Necessarily Help Republi

cans?, 49 J. Pol. 69 (1987) ........... ........................

Grofman and Handley, Black Representation

Making Sense of Electoral Geography at Differ

ent Levels of Government, 2 Legis. Stud. Q.,

XIV, 265 (1989) ......... ........................ ..................

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

46

48

BRIEF OF THE APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case presents the question whether the extreme

racial gerrymandering embodied in the legislation estab

lishing Georgia’s Eleventh Congressional District violates

the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. Apply

ing this Court’s decison in Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816

(1993), the District Court found such a violation since

race was the overriding consideration in the District’s

bizarre configuration and since the legislation creating

these lines (O.C.G.A. § 21-2-3) was not narrowly tailored

to further a compelling governmental interest.

Without acknowledging the standard of review appli

cable to the District Court’s findings of fact, Appellants

assail the decision from a variety of angles. The “State

Defendants” (Defendants Miller, Howard and Cleland),

concede the district was racially gerrymandered as defined

in Shaw, supra at 2823 (“the deliberate and arbitrary

distortion of distinct boundaries . . . for [racial] pur

poses”), but assert that the District’s appearance is not

sufficiently irregular or bizarre to come within the reach

of Shaw} The Appellant United States, acting through

the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) goes so far as to

assert that “the appearance of the Eleventh District on a

map comports reasonably with Georgia’s ordinary dis

tricting practices.” DOJ Brief, p. 23. Appellants collec

tively downplay race as but one of several considerations 1

1 One of the Defendants at trial, Speaker of Georgia’s House of

Representatives, the Hon. Thomas Murphy, reluctantly cast the tie

breaking vote in favor of the final Georgia plan. He stated at the

time the State was engaging in racial gerrymandering because

“what we did is went into counties and precincts and picked up

pockets of African-Americans to make a strong district with vot

ing age black population so that it would guarantee a black would

be elected from there.” Tr. II, 62. He characterized the District

as resembling an “octopus.” Tr. II, 63. Speaker Murphy did not

appeal the decision of the District Court.

which affected the boundaries of the District, thus preclud

ing relief.

These portrayals are, at best, advocacy. The lines of

Georgia’s Eleventh District are extraordinarily irregular

by any honest reckoning. They are absolutely without

precedent in the history of Georgia congressional redis

tricting. To contend that race did not drive the decision

making concerning the lines of the Eleventh District is to

deny reality. Georgia’s entire congressional districting

scheme could not be more racialized than it is today.

It is the epitome of what this Court decried in Shaw.

If one fact pervades this case, it is the fact that the

1992 redistricting plan does not remotely resemble what

the Georgia legislature wanted. Georgia is subject to the

preclearance requirements of Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act. Once Georgia chose not to seek a judicial

stamp of approval for its redistricting—an extraordinarily

difficult undertaking in March of an election year—its

only option was to follow the mandate of the DOJ. If it

refused, a federal court in Atlanta had already scheduled

a hearing to draw the lines for the State by default. See

note 22, infra.

The evidence presented at trial established beyond any

doubt that the DOJ approached redistricting in Georgia

with a specific mission. That mission was to maximize

by whatever means necessary both the number of majority

black congressional districts in the State and the percent

age of black voting age population within these districts.

The fact that the State’s African-American population,

other than in Atlanta, is widely and unevenly disbursed

throughout the State south of Atlanta mattered not to

the DOJ:2 J.A. 130. The command was that blacks

2

2 Only 17 out of 159 counties in Georgia are majority black.

They are largely rural and sparsely populated, representing only

7.2 percent of the State’s total black population, according to the

1990 census. Over a third of these people reside in Dougherty

County, in Southwest Georgia, where Albany is the county seat.

PI. Ex. 16A, at 123-24.

3

needed to be linked together with other blacks regardless

of location, regardless of economics, regardless of voter

confusion, regardless of literally anaything other than the

constitutional requirement of one person one vote.3

Georgia’s 1992 Redistricting Plan

Creates Lines Which Are Exceedingly Irregular

Appellants go to significant lengths to make the Elev

enth District appear somehow normal.4 Staring Appellants

in the face, however, are the lines themselves. The most

cursory inspection by someone knowledgeable about Geor

gia’s geography would reveal their extremely irregular

character.

What defines the Eleventh District, both racially and

geographically, is not its very sparsely populated center,

but the serpentine appendages which dramatically spring

from that center. One snakes along the Savannah River

to select portions of the City of Savannah. Another hooks

in a thoroughly confusing fashion through Richmond

County and City of Augusta. Yet another runs like a

thread through Henry County, where the District almost

disappears, only to be reborn in select portions of DeKalb

County adjacent to the City of Atlanta. Additional, odd

13 Even the one-person one-vote requirement was partially sacri

ficed at the alter of racial classification. In order to satisfy the

DOJ’s vision for the State, it was necessary to create an unsually

high overall population deviation (.94). See O’Rourke Report, Pl.

Ex. 85, at 2-3.

4 It is apparent from media reports that the District is widely

perceived as anything but “normal.” An editorial in the Atlanta

Journal describes the District as “grotesque.” A Wall Street Jour

nal editorial has described the District as “bizarrely shaped.” The

Augusta Chronicle has described it as a “crazy quilt.” Along with

congressional districts in North Carolina and Louisiana, it was

featured in the July 12, 1993 issue of Time Magazine, and the

lead story in the February 14, 1994 edition of the New York Times.

PI. Ex. 19-23. J.A. at 29 (Stip. 74). A widely-quoted reference

source on congressional districts, the Almanac of American Politics

1994, refers to the District as a “geographic monstrosity.” Tr.

Ill, 105.

4

appendages are found in Wilkes, Baldwin and Twiggs

Counties.'5

The Eleventh District is not only shocking on this

“macro” level. The fact that the District traverses almost

the entire State at its widest part is only the beginning.

In many locations, the lines are very difficult if not im

possible to follow, even with a road map. Dr. Timothy

O’Rourke, an expert retained by Plaintiffs, personally

tracked the district lines in several areas. In Augusta,

he testified the lines “will follow a major cross-town road

for a couple of blocks and it will then veer into residen

tial neighborhoods. It is a very difficult line to find. It

certainly is not a line that is easily demarcated on a

map. . .” Tr. Ill, 106. Overall, he found the lines were

“not readily identifiable so that if you are a citizen and

its not really clear to you—one could not easily explain

to you if you were in the vicinity of a line whether you

were in the district or out.” Tr. Ill, 110. See Detail

Map, O’Rourke Supp, Rpt., PI. Ex. 85, at 3.

In Chatham County and the City of Savannah, Dr.

O’Rourke observed similarly strange line configurations.

5 The use of appendages in Georgia’s 1992 congressional redis

tricting legislation to create artificial districts driven by race is

by no means restricted to the Eleventh District. The Second Dis

trict also has numerous appendages along its borders, which meth

odically divide counties and cities in tortuous fashion. One pro

trusion meanders through Houston, Peach and Bibb Counties in a

manner which resembles a tomato splat. J.A. 187-188. At its

northern end, the Eighth District loops around the Second to take

in the western portion of Bibb County. J.A. 62. The resulting

configuration of the Second, Third, Eighth and Eleventh Congres

sional Districts in this area prompted Linda Meggers, Beapportion-

ment Services Director for the Georgia General Assembly for more

than twenty years, to observe: “It gets, very hard to understand

right there.” Tr. I, 79. The Second Congressional District also

includes portions of Meriwether County, taken in by means of a

tiny pathway, which leaves that county divided into three segments,

two of which are non-eontiguous, but nevertheless included in the

same congressional district. Defendant Lt. Governor Howard char

acterized what happened to Meriwether County as. a “terrible

thing—it was just emasculated in this process.” Tr. IV, 218.

5

At the north end of the county, he found a “very, very

narrow [land] bridge indeed” that was “not readilly ac

cessible by roads on the maps” since it was swamp land

within the Savannah Wildlife Refuge. Tr. Ill, 113-15.

At one point inside the City of Savannah, the entire

width of the district was between 2/10 and 3/10 of a

mile. Tr. Ill, 113.

Extensive evidence was provided at trial to support

Dr. O’Rourke’s conclusion that “a tour of the Eleventh

District confirmed what the maps of the district only

begin to suggest: that the lines of the district are, in many

places, jagged and haphazard, difficult to follow, barely

contiguous and plainly noncognizable.” PI. Ex. 85, at 8-9

(Detail Maps).8

The grossly irregular lines of the Eleventh and Second

Districts create very strange features in the Third and

Eighth Congressional Districts as well. The Third District

is “hollowed out” by virtue of the intrusion of the Second

into Meriwether County. The Eighth District has an

almost indecipherable western edge, directly caused by nu

merous gossamer appendages from the Second. Absent a

large detail map, the Eighth District appears to be com

pletely dissected in Bibb County. J.A. 62.

While the lines of the Eleventh District are extraordi

nary in absolute terms, they are even more so when

viewed in light of where the population of the district is

located. The portion of DeKalb County in the Eleventh

District alone constitutes 35.3% of the district’s total

population. The excised portions of DeKalb, Richmond,

Chatham and Baldwin Counties account for nearly 70%

of the district’s population. PI. Ex. 24. 6

6 The difficulty in ascertaining where the lines of the district are

located has prompted the office of the present U.S. Representative

for the Eleventh District to contact Georgia’s Legislative Re-

apportionment Office for more detailed maps. The reason that

staffers provided for the inquiry was “we can’t figure out what’s

ours.” These requests have continued even after the representative

had been in office for almost two years. Tr. II, 34.

6

Of the 18 “other” counties (or parts thereof included

in the Eleventh Congressional District), not one has a

population constituting more than 3.5% of the entire

district. Indeed, 12 have a population constituting 2%

or less of the district’s total. The portion of DeKalb

County included in the Eleventh District by itself repre

sents 4.1% more of the district’s total population than

all of these 18 counties put together. J.A. 131.

Race Was The Overriding Consideration

In Georgia’s 1992 Congressional Redistricting Plan

By placing demographic information over the lines

established in Georgia’s 1992 Congressional Redistricting

Plan, it is immediately apparent that race dominated the

1992 Georgia Congresional Redistricting Plan in general,

and the Eleventh and Second Congressional Districts in

particular. Indeed, it is quite apparent that the Eleventh

District is not a district at all in the conventional sense.

It is nothing but an amalgam of distantly located concen

trations of black population located at the end of racially

gerrymandered appendages attached to a thinly populated

rural center. By means of these computer generated

racially gerrymandered appendages, the district is trans

formed into one which is almost 65% black.

The demographic heart of the population of the Elev

enth District is split amongst portions of three distant

counties, DeKalb, Richmond and Chatham. They account

for almost two-thirds of the total population and more

than 73.7% of the black population of the entire district.

J.A. 131. No one can seriously deny that these areas

were brought into the Eleventh District for purely racial

reasons, and that the “land bridges” used to reach them

exist to avoid including more whites in the district.

The statistics respecting these three counties are simply

overwhelming. DeKalb County as a whole is 42.2%

black. Yet, on the Eleventh District side of the line,

74.6% of the population is black. On the other side of

the line in DeKalb County, only 22.4% of the population

is black. In Richmond County, blacks constitute 42%

7

of the county’s population. Yet, blacks constitute 66%

of the county’s population within the district. Blacks con

stitute only 18.8% of the non-Eleventh portion of Rich

mond. In Chatham County, blacks constitute 38.1% of

the population. Yet, in the portion of the county within

the Eleventh, blacks constitute 84.1% of the population.

On the other side of the line, they constitute only 15%

of the population. PI. Ex. 16, Table 3.

The same phenomenon of dividing citizens by race

exists in the three other non-land bridge split counties as

well.7 PI. Ex. 16, Table 5. In Twiggs County, 88.8%

of the County’s blacks are placed in the Eleventh. In

Wilkes, the figure is 62%, and in Baldwin 89.5%. No

one can seriously argue that such stark divisions are

anything other than an intentional segregation of voters

according to race.

In the face of this uncontroverted statistical evidence,

the State Defendants in particular come forward with

their own explanation for all the split counties, cities and

precincts in the Eleventh District, somehow trying to show

“non-racial considerations” in the dissection of these po

litical subdivisions. While they criticize the Distrct Court

for not commentng on every last squiggle, they surely

7 The two split counties which are exclusively land bridges are

Henry and Effingham.

It was “necessary” to utilize a land bridge in Henry because it

has a substantial population, which is 90% white. It can readily

be seen that the Henry County corridor alone does not link the

black population excised from DeKalb County to other population

changes in the district by itself. The remainder of the linkage is

provided by lining up three additional counties (Butts, Jasper and

Putnam) in “single file” to reach the district’s: “geographic center.”

While these counties remained whole, they are very sparsely popu

lated, collectively accounting for only 3.5% of the district’s total

population. Because they have no significant impact on the Dis

trict’s racial percentages, it was acceptable to leave them whole.

It is admitted by the State that an Effingham County land

bridge exists solely to link black population in Savannah with the

rest of the District. See State Admissions of Fact, Tr. IV, 159-60.

Effiingham County is 85% white.

8

realize that their efforts are an exercise in accentuating

trivialities. Indeed, some of the most compelling evidence

contradicting the State Defendants’ current argument came

from the Defendant Lt. Gov. Howard. When asked what

portions of the boundaries of the Eleventh he considered

to be a function of race, Howard responded “Well, basi

cally the whole district.” Tr. IV, 208. (Emphasis added).

According to him, the district lines were drawn “for the

purpose of achieving a certain racial—a certain racial

composition of the district. I think that’s obvious. I

don’t think anybody disagrees with that.” Id. When ad

vised “Well, they [the Appellants] do”, he responded:

“We’re trying to achieve a certain VAP in a certain

population. Why else would you draw it like that?” Id.

Howard acknowledged that DeKalb County was an

integral part of this effort. He noted that some black

voters in DeKalb were “ceded” to the majority-minority

Fifth District because of their history of low voter turn

out. “They [the DOJ] wanted us to go in and get all the

blacks that had the best voting records into this [Elev

enth] district. . .” Tr. IV, 209-210. He further testified

that the slice of Henry County that ended up in the

Eleventh was a “bridge” designed to connect “the large

block of black voters in DeKalb County and the large

block of black voters elsewhere.” Tr. IV, 211. Other

locations for this land bridge, such as portions of Newton

and Rockdale Counties, were considered as alternatives

to Henry since they too “don’t have any significant num

ber of black voters.” Tr. IV, 211. Regardless of the

specific route chosen, the State Defendants admitted the

sole purpose of the land bridge was to avoid white popu

lation in the search for black voters.

The Lt. Governor also acknowledged that the irregular

lines in Twiggs County were the product of “computerized

hunting for concentrations of blacks.” Tr. IV, 213. One

portion of the county was “becoming more white so we

left that out.” Id. As for Baldwin County, he recalled

the understandable bitter opposition to splitting the county.

“But the Justice Department told us that we had to go

9

in and get the blacks in Baldwin County . . . and include

that in the Eleventh District. So we did that.” Tr. IV,

312. Wilkes County followed the same pattern; the Lt.

Governor explained its dissection as follows: “The areas

that we have included in the Eleventh District in Wilkes

County were more heavily black than the northern part

of it. So we went in and just got as many black voters

as we could on the southern edge, so that’s why the line

sort of meanders around through there.” Tr. IV, 212.

The land bridge in Effingham County “was done to mini

mize the effects on Effingham County, but at the same

time build a bridge to Savannah to get the black voters

in Savannah as we were directed to do.” Tr. IV, 214.8

Aside from this and other compelling testimony, the

State Defendants’ effort is premised on a logical flaw.

Simply because a district line follows a portion of a pre

cinct line or a municipal boundary line or partially

coincides with a major thoroughfare does not begin to

suggest that its placement was not race-based. Racial

percentages of precincts are well known when they are

included in a district. Tr. II, 271-82. It was the ACLU’s

8 While the Lt. Governor did not testify extensively about the

district lines in Savannah and Augusta, other witnesses did.

Augusta was slashed to pieces solely to achieve desired racial

percentages. Tr. I, 93. It was a “block by block” racial search.

P.I. Tr. 51. So many voting precincts were split that some 32 new

ones had to be created. Tr. II, 224. The land bridge to reach

Augusta is a strip of nearly deserted territory. The State took

its cue from the ACLU’s Max Black plan. The reason for the differ

ence between it and the final plan was explained by Ms. Meggers:

“ l i l t [the Max Black Plan] only drew the three [black majority]

districts. I had to draw all eleven of them.” Tr. I, 102.

As for Savannah, Mr. Dixon, who drew the lines, made clear that

his motives were purely race-based. “Frankly, taking the directive

from the Justice Department, [I was] quite literally identifying

the concentrations of the black urban concentrations in the City

of Savannah and somehow getting to them and incorporating them

in contigiuty [with] the Eleventh District. P.I. Tr., 52. He drew

the lines “to make sure that blacks were on one side and the whites

were on the other.” Id. When asked if there was any consideration

besides race in this effort, he testified there were “none what

soever.” Tr. IV, 159-60.

10

Kathleen Wilde, the primary architect of the “Max Black”

plan, who characterized precincts as the “traditional build

ing blocks” of districting. Tr. IV, 83. The legislative

guidelines say the same thing. J.A. 68-69, 75. It is like

wise an unassailable fact that, in some urban areas, black

population tends to be concentrated on one side of a

major thoroughfare or rail line. Tr. IV, 80. This is the

case both in parts of DeKalb County and in parts of the

City of Savannah. Tr. II, 216. And the computer soft

ware provided racial data in census blocks that often

coincided with these types of “lines.” This was the lowest

level at which the computer could access racial informa

tion, which aside from VAP and total population, was the

only demographic information maintained in the system.

Tr. I, 50-5 l;T r. II, 14.

In light of the way this district’s lines corral black

voters and exclude whites, as borne out by the statistics

concerning the racial impact of those lines on Georgia’s

congressional districts, further discussion of the massive

direct evidence of racial gerrymandering would appear

almost superfluous. As the District Court stated: “At a

glance, the appendages of the Eleventh are obviously

designed to do something; after cursory exploration, it

rapidly becomes clear that the ‘something’ is maximiza

tion of black voting strength.” J.S. App. 49. Suffice it

to say that, without exception, every witness who testified

in the case concerning the redistricting process confirmed

that the 1992 congressional redistricting plan was a de

liberate effort to separate voters according to their race.

See Murphy, Tr. II, 62; Meggers, Tr. I, 101-02-106-07;

125-25, 270-273; Dixon, P.I. Tr. 41-42, 46-49, 51-52;

Hanner, Tr. Ill, 247-259; Garner, Tr. Ill, 210-214.

While Appellants do their level best to downplay the

evidence presented at trial, they cannot honestly disagree

with the Court’s conclusion that “copious amounts of

direct evidence” was presented to establish that the dra

matically irregular lines of the Eleventh Congressional

District were the product of race-based manipulation. J.S.

App. 52.

11

Georgia’s 1992 Redistricting Plan Makes A

Mockery Of Traditional Districting Principles

Shaw makes clear that traditional districting principles,

such as compactness, contiguity and respect for political

subdivisions are not constitutionally required. Neverthe

less, they take on considerable significance in the context

of ascertaining whether racial gerrymandering has oc

curred. This is because they are “objective factors that

may serve to defeat a claim that a district has been gerry

mandered on racial lines.” Shaw, supra at 2827.

Appellants attempt to sidestep this aspect of Shaw

by suggesting that a core traditional districting prin

ciple like compactness has “relative unimportance” in

Georgia. State Brief, at 20; DO! Brief, at 24-25. Such a

contention is simply untrue. While it is correct that the

guidelines of the House and Senate Reapportionment

Committees do not expressly use the word “compactness”,

both sets of guidelines plainly state that, where legal re

quirements are satisfied, “efforts may be made to main

tain the integrity of political subdivisions and the cores

of existing districts.” J.A. 68, 75. Contrary to Appel

lants’ suggestion, Georgia has a long history of reason

ably compact districts, with common economic interests

being the “prime driving force behind congressional re

districting traditionally.” Tr. I, 21-22. Linda Meggers,

among others, recounted the specialized interests tradi

tionally lying at the heart of the First (coastal) District,

the Second (specialized agricultural) District, the Third

(military) District, and the Seventh (textile and carpet

ing) District. Tr. I, 23-27. The Eighth District, not

withstanding its relatively large size, was “definitely agri

cultural from one end to the other.” Tr. I, 14. It was

undisputed that its northward expansion was only under

taken to comply with one-person one-vote. Tr. I, 31-34.

The Ninth District is the State’s mountain district where

poultry is the predominant industry.® Tr. I, 23-27. The 9

9 The Abrams Intervenors argue that the Ninth District was

drawn to be a distinctive white community. This is incorrect. The

12

Tenth has traditionally encompassed the Athens-Augusta

area and the surrounding rural areas of East Central

Georgia. Tr. I, 25. See also P.I. Tr. 59-63; Tr. Ill, 251.

Georgia’s prior congressional maps confirm the signifi

cance of compactness in congressional redistricting. A

review of the maps from 1964, 1971, and 1982 invariably

reflect reasonably compact districts. J.A. 78-81. By way

of contrast, they also amply demonstrate the unprece

dented departure the 1992 redistricting plan made from

those practices.

That the State Defendants would now challenge the

significance of compactness in Georgia congressional re

districting is a remarkable turn of events. During the

preclearance process, Georgia’s Attorney General was

literally pleading with the DOJ not to require what ulti

mately was required. In his letter of March 3, 1992,

he wrote: “In addition, the extension of the Second Dis

trict into Bibb County and the corresponding extension

of the Eleventh District into Chatham County, with all

of the necessary attendant changes, violate all reasonable

standards of compactness and contiguity.” J.A. 118. (Em

phasis added.) How could something which was so criti

cal then become marginal now?

As the District Court found, the Eleventh District is

not compact by any credible definition of the term.10 J.S.

mountain region of the State is not race-based. The region is

geographically distinct. (In contrast, the Eleventh traverses four

regions of the State. PL Ex. 43.). There are no adjacent black

population concentrations that were excluded. No evidence was

offered at trial to suggest that racial gerrymandering had anything

to do with the configuration of the Ninth District. In a state 73%

white, there will be predominantly white districts, particularly

when 61.7% of its black citizens are packed into three majority-

minority districts.

10 Even the Attorney General testified that the Eleventh District

is not compact. P.I. Tr. 148. The only witness at trial to offer a

contrary opinion was an expert retained by the State Defendants.

She offered a “meanderingness” test developed by the State De

fendants’ attorneys especially for this litgation. None of the

13

App. 80. The massive amount of evidence presented at

trial on this subject confirms what any reasonable in

dividual would conclude given even a nodding acquaint

ance with the geography of the State and its redistricting

history.11 12 The sole reason for this lack of compactness is

that “reasonable standards of compactness and contiguity”

were of no interest to the DOJ. All that mattered was the

lumping together of distantly located urban and suburban

blacks by means of a sprawling, and often tortuous, rural

pathway.112

Appellants refer to it in the briefs, and for good reason. The

District Court found it “especially useless in analyzing the Elev

enth District” since its measures only “the vast—and sparsely

populated” core of the District while the “narrow—and densely

populated—appendages escape notice.” J.S. App. 79. Far from

aiding Appellants, the test is “an excellent means of highlighting

the egregiously manipulated portions of any voting district.” Id.

Not surprisingly, using mathematical measurements of compact

ness the Eleventh District scores the lowest in Georgia, and among

the lowest nationwide (bottom 8% in “dispersion score” ; bottom

11% in “perimeter score” ). PI. Ex. 85, 7.

11 The State Defendants offered into evidence maps of certain

Georgia cities for the ostensible purpose of showing that “geo

metric niceness” is relatively unimportant in drawing municipal

boundaries. These maps are irrelevant to whether compactness is

a traditional districting principle in congressional redistricting.

At the Pretrial Conference', the District Court advised the parties

that municipal boundaries are accretions of annexations which are

tax-driven and that the Court had little interest in them. At trial,

the Court again advised the State these maps were without evi

dentiary value. Tr. V, 120-21, 123. And the State offered no evi

dence as to how they were relevant.

12 At pp. 23-24 of its Brief, the DOJ states the Eleventh District

“generally occupies an area similar in shape to, but generally south

of, the former Tenth District, which also spans a central part of

the State from Augusta to the Atlanta suburbs.” What the DOJ

bases this statement on is unknown. It is clearly wrong. A cursory

review of prior redistricting maps shows that the “old Tenth” does

not resemble the Eleventh District in any way, shape or form.

The old Tenth had no hooks, tails or other wild protrusions nor did

it ever extend, in the words of Ms. Meggers, “literally from the

shadow of the Capital to Tybee [Lighthouse in Savannah].” Indeed,

14

Appellants had to acknowledge that “respect for politi

cal subdivisions” is an important and traditional redis

tricting principle in Georgia. They are thus forced to

contend that political subdivisions were respected in 1992.

In fact, nothing could be further from the truth.

The essence of the State Defendants’ argument is that

“86.6% of the entire area of the Eleventh Congressional

District is comprised of whole counties” and that “71.1%

of the Eleventh Congressional District lines runs right

along boundaries of the State, counties or municipali

ties.” 13 These numbers, however, do not mean political

subdivisions have been respected. All that these numbers

demonstrate is that county boundaries have been followed

only where relatively few people are located and where

there is no material impact on the racial composition of the

district. Once again, the statistics tell the story in dra

matic fashion.

As shown in Plaintiffs’ Table 2 (PI. Ex. 24), the por

tions of DeKalb, Richmond and Chatham Counties located

in the Eleventh District represent less than 3 .5% of the

land area included in the district. Yet, almost two-thirds

of the population of the district and almost three-quarters

of the black population of the district resides in these three

relatively small areas, all at the extreme ends of appen

dages. LA. 131.

When the analysis is extended to include all eight split

counties, it can be seen that political subdivisions have

been “respected” where less than 27% of the district’s

citizens reside. Id. Where the vast majority of people live,

political subdivisions have not been respected at all.

The degree to which political subdivisions have not

been respected in the 1992 congressional redistricting plan

it never extended further southeast than Richmond County and the

City of Augusta.

13 The State Defendants’ utilization of State boundaries to “up”

its percentages is curious indeed. The State has little choice but

to draw congressional districts within them.

15

is without precedent in Georgia history. Between 1931

and 1964, Georgia’s congressional districts had no split

counties. J.A. 81. In 1964, only Fulton County was

split—in order to comply with one person one vote. J.A.

78. In 1971, two counties were split, Fulton and Whit

field.14 J.A. 79. In 1982, only three (of 159) counties

were split—the metro Atlanta counties of Fulton, DeKalb

and Gwinnett. J.A. 80.

The 1992 congressional redistricting plan splits 26

counties. PL Ex. 16A. This represents a 1200% increase

over the 1971 plan and a 767% increase over the 1982

plan. In the Eleventh District alone, almost three times

as many counties are split than were split in the entire

1982 congressional redistricting plan. Of the 26 split

counties in the current congressional redistricting plan,

20 of them occur in the Eleventh and Second Districts.

These numbers are stunning in light of the heavy em

phasis citizens placed on not splitting counties at public

hearings on redistricting held throughout the State in

1991. Tr. Ill, 207, 246; P.I. Tr. 43.

The 1992 congressional redistricting plan is no less

sparing of municipalities. J.A. 128. Prior to 1964, there

were no split municipalities. In 1971 there were two,

Atlanta and Dalton (Whitfield County). In 1982, five

metro Atlanta cities were split. However, the 1992 plan

splits 31 municipalities, an increase of 520% over the

previous decade.

The evidence at trial was uncontradicted that the

ACLU’s “Max Black” plan served as the minority popu

lation benchmark throughout. Including whole, albeit

sparsely populated, counties did not alter the racial com

position of the district in any significant way because

Ms. Meggers intensified the racial gerrymander where it

counted—in the densely populated, but distantly located,

black urban centers. As she testified: “I was trying to

14 The splitting of Whitfield County was due to political considera

tions. The legislature took a “big beating” for having done so.

Tr. I, 35. The split was removed in the next round of redistricting.

16

clean the plan up, get back the whole counties as much

as I could, and at the same time achieve this benchmark

number that had been presented to us in the Max Black

plan.” Tr. I, 96-97. The lines Ms. Meggers drew in

urban areas became even more irregular than the ACLU

lines and necessitated splitting more precincts. Tr. I,

98-99; Tr. IV, 84. “[W]hat I did was basically go in

and find white areas to take out to offset the whites I

may have added in the rural counties.” Tr. II, 30; Tr. I,

102, 224. By creating more jagged and irregular lines

in population centers, including splitting precincts, Ms.

Meggers got the plan “within just fractions of a percent

age of what they achieved” in the Max Black congres

sional plan. Tr. II, 55.

As the foregoing makes clear, the State Defendants’

assertions regarding “respect for political subdivisions” is

a charade. Essentially they argue that, as long as it can

locate a “desert” in which to adhere to county lines, it

then gained free rein to engage in racial gerrymandering

the population centers that are the lifeblood of any voting

district.1'5

Georgia’s 1992 redistricting plan maintains but token

contiguity throughout its various districts. Dr. O’Rourke

characterizes the Eleventh District as merely a “conglom

eration of dissimilar places.” Tr. Ill, 134. Some of these

places, he observed, were connected by “narrow threads.”

In his Supplemental Report (PI. Ex. 85, at 8), he refer

ences several areas where the Eleventh “barely satisfies

the test of contiguity.” In the Richmond County “hook”,

the district narrows to the width of the local airport. In 15

15 A similar disrespect for political subdivisions is evident in the

Second District. There, twelve counties are split. In each, the

district includes a highly disproportionate share of the county’s

black residents. In Bibb County, the Second lassos in 82.4% of

the county’s black citizens. In Dougherty County, the figures rises

to 85%. In Muscogee County, the figure rises still further, to

86.9%. As shown at J.A. 135-136, the inclusion of black voters

in the Second District, via gerrymandered lines, had a determina

tive impact upon the district racially.

17

Effingham County, the Eleventh District contracts to a

strand less than Vi mile wide. In Savannah, the district

sends a tentacle through a breach in East Victory Drive

that is even narrower. In Henry County, the western

edge of the district is but several hundred yards from the

eastern border. In Chatham County, one connecting point

consists of swamp land. Tr. Ill, 115. At another point,

the district is nothing more than the water column of the

Savannah River itself. Tr. IV, 161. In a state as large

as Georgia, and in a district which is 260 miles long,

this is a remarkable spectacle.

A district which violates, in Georgia’s Attorney Gen

eral’s own words, “all reasonable standards of compact

ness and contiguity,” provides strong objective evidence

that something dramatic is impacting the district lines.

The District Court found it is “practcally stipulated” (J.S.

App. 43) that but for race, none of this would have

been considered, let alone implemented. No prior con

gressional redistricting map in Georgia’s history contains

districts even remotely resembling the Eleventh.18

The DOJ sums up its discussion of traditional dis

tricting principles with the bald assertion that the Eleventh

District “comports reasonably with Georgia’s ordinary

districting practices.” DOJ Brief, p. 23. This is not a 16

16 While “communities of interest” were not specifically refer

enced in Shaw, a significant amount of time was devoted to this

subject at trial. The DOJ, along with the Abrams Intervenors,

argued that blacks constitute a distinct community of interest co

extensive with their skin color. The Court rejected this for a

variety of reasons, among them that poor blacks in Savannah do

not feel some automatic bond to those living in black neighborhoods

in Metro Atlanta, many of which are quite affluent. J.S. App. 45-

46. Dr. O’Rourke provided “compelling testimony . , . making it

exceedingly clear that there are no tangible ‘communities of inter

est’ spanning the hundreds of miles of the Eleventh District.”

J.S. App. 81; PI. Ex. 85, at 10-29. Black medium income in DeKalb

County, for example, is nearly 50% higher than black medium

income in the next ranking county (Richmond) and more than

twice as high as black medium income in the lowest ranking eight

counties.

18

serious argument. Surely if the DOJ was aware of a

prior Georgia congressional district dominated by tails,

hooks, protrusions, with utterly indecipherable designs at

the end of these appendages, it would have brought it to

the District Court’s attention. It most assuredly did not.17

The DOJ And The Demand For Maximization

Long before the DOJ provided formal notice that it

would not accept anything less than the maximum number

of majority-minority districts that could be constructed

in the State, the DOJ had communicated this requirement

to members of Georgia’s Black Legislative Caucus, which

was represented by the ACLU. As early as August, 1991,

State Rep. Tyrone Brooks of Atlanta announced to the

General Assembly:

“We are simply trying to maximize our voting

strength, and I think we are right in line with the

mandate for the U.S. Department of Justice.

The Justice Department is not going to say, well,

the lines look funny, or you got a portion of

Chatham, you got a portion of DeKalb, more citi

zens of DeKalb are in this plan than Chatham.

They are not going to be concerned about trivial

issues like that. They are going to be concerned

about whether or not you’re diluting the voting

strength of minorities or whether or not you are max

imizing the voting strength of minorities. That’s the

only thing that I get from Washington when I talk

to the lawyers. They want to make sure that,

wherever possible—that you are drawing majority-

17 The DOJ’s assertion that districts the State “continues to

draw” (i.e., in 1992) should serve as. an “appropriate benchmark”

for determining- whether a district is highly irregular or bizarre

is almost Kafkaesque. It was the DOJ’s pummelling which drove

the State to draw the Second, Third, Fifth, and Eighth and Elev

enth Districts as it did. As Bob Hanner, Chairman of the House

Reapportionment Committee, testified, the only thing DOJ officials

were interested in was racial percentages. Tr. Ill, 256. Ultimately,

the Georgia legislature “split virtually everything except homes to

. . . maximize black percentages.” Tr. Ill, 250.

19

minority districts. And that’s all I hear. I don’t

hear them saying the lines look funny, the map looks

crazy or it’s a zig-zag or it’s something someone just

threw on the wall. I hear them saying, make sure

you don’t dilute, and make sure, wherever possible,

you create majority black districts, and I don’t hear

anything different.”

PI. Ex. 130, 16-18. (Emphasis added.)

While the DOJ studiously avoided the term “maximiza

tion” and the “wherever possible” standard in its written

communications with the State, there is no question that

the effect of its written communications was to require

precisely what it told Representative Brooks was necessary

to pass DOJ muster.

The technique used by the DOJ to coerce the State

into maximizing the number of minority-majority districts

was to exploit the “purpose” prong of Section 5 of the

VRA. The initial plan offered by the State of Georgia was

obviously not retrogressive since it doubled the number

of majority-minority districts, from one to two.18 In this

litigation, the DOJ freely admitted that neither Georgia’s

first or second submissions were retrogressive.

In utilizing the “purpose” prong of Section 5 to impose

its maximalist will on the State, the DOJ resorted to

the concept of “pretext.” J.S. App. 25-26.19 Any plan

18 At a June, 1990 training conference of the State Legislature

Reapportionment Task Force held in Baltimore, Maryland, then-

Assistant Attorney General for the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division,

John Dunne, advised the attendees that the DOJ was going to take

a particularly exacting approach to redistricting in Georgia. P.I.

Tr. 17. Georgia’s legislative leadership was determined to ap

proach redistricting so as to “meet the mandates of the Justice

Department. . . [T]hat was a positive thing the committee wanted

to do.” Tr. Ill, 252.

19 Notwithstanding its admitted use of “confidential informants”

to spy on State legislators and officials throughout the redistricting

process, the DOJ presented absolutely no evidence at trial suggest

ing any effort to discriminate against minorities in the two con

gressional redistricting plans that were rejected by the DOJ. In

deed the only evidence was to the contrary. Tr. Ill, 221, 258.

20

which did not lump as many blacks together as another

plan was deemed suspect. Of course, the DOJ had before

it the ACLU’s Max Black plan. It was obvious through

out the redistricting process that this was the standard by

which all other plans would be judged. J.S. App. 20;

Tr. I, 65.

Initially, the DOJ did not formally require that the

State extend the Eleventh District to Savannah. Its initial

rejection letter, dated January 21, 1992, raised a concern

“that the Georgia legislative leadership was predisposed

to limit black voting potential to two black majority dis

tricts”, and made specific comments concerning the need

to better recognize “the black voting potential” in the

southwest (Second) district and in Baldwin County in

the Eleventh. J.A. 105-106.

The DOJ’s rejection letter did not specify what it meant

concerning black voters in the Second District. However,

as the District Court noted, to maximize the number of

black districts in the State, it would be necessary to some

how place black population concentrations in Macon

into the Second District, and extend the Eleventh to

Savannah. This was the “linchpin” of Ms. Wilde’s Max-

Black plan. She had alerted the DOJ that it was the

“key to drawing a third black district.” PI. Ex. 57. See

J.S. App. 19-20.

Based on the information before him, Senate Majority

Leader Wayne Garner became convinced that, despite

the lack of specificity in the DOJ’s rejection letter, no

plan was going to gain DOJ approval unless the Eleventh

was extended into Chatham County and the black resi

dents of Savannah were gerrymandered into the district.

He testified: “[Ljooking at this entire process and listen

ing to the other members of the committee, I was of the

opinion and told the Lt. Governor early on, I said if we’re

going to get a plan past the Justice Department and get

us out of here and on to these elections, that district is

going to have to go to Savannah. In talking with Ms.

Meggers, my point was the district must have the highest

21

percentage of black population that we could get, [re

gardless] of where we have to go.” Tr. Ill, 210. Solely

to “get the percentages high enough” for the DOJ (Tr.

Ill, 210), the Georgia Senate passed a plan in late

February, 1992 containing an extension to Savannah in

the Eleventh, and including black concentrations in

Macon in the Second District by means of a tentacle

extending into Bibb County.20

Senator Garner informed Georgia House Reapportion

ment Committee Chairman Mr. Hanner that in his view,

the DOJ “was going to mandate” a district extending from

DeKalb to Savannah. Tr. Ill, 254. However, the House

would not go along “unless the Justice Department man

dated us to do it in writing.” Tr. Ill, 250. As Repre

sentative Hanner testified: “I thought it was ridiculous.

I thought—I just didn’t think we’d have to—I thought

that was the max, and I did not think we would ever

have to do that.” Tr. Ill, 250; Tr. II, 69.

By letter of March 20, 1992, the DOJ made it explicit

where it stood. Georgia’s plea that the “extension of the

Second District into Bibb County and the corresponding

extension of the Eleventh into Chatham County, with

all of the necessary attendant changes, violates all reason

able standards of compactness and contiguity” fell on deaf

ears. In the Eleventh District, the extension to Savannah

would be required. The DOJ rationalized this require

ment by citing the February 1992 Senate Plan referenced

above—the Plan that was passed solely because the

Senate leadership believed it was ultimately going to be

mandated by the DOJ. J.A. 124. As for the Second

District, the DOJ now made it clear that it was going

to require the inclusion of “black population concentra

tions in areas such as Meriwether, Houston, and Bibb

[City of Macon] Counties.” J.S. App. 124-125. The fact

20 The Senate Plan generated three majority-minority districts

in terms of population, but not in terms if VAP. In terms of VAP,

the Senate Plan was 58.66% black in the Eleventh District, but

“only” 47% black in the Second. J.A. 63.

22

that the State had previously been forced to split counties

elsewhere to satisfy the DOJ served as the “evidence”

that the failure to split additional counties elsewhere at

the DOJ’s command was “pretextual.” 21 J.S. App. 125.

Since the Macon/Savannah trade had been “suggested to

the legislature during the redistricting process”, it simply

had to be done. J.S. App. 125. Issues of compactness,

contiguity, respect for political subdivisions and former

district cores, local economic interests and the like were

entitled to no consideration whatsoever.

All of the foregoing machinations aimed at minority

vote maximization transpired prior to this Court’s opinion

in Shaw v. Reno. Faced with litigation on one, if not two

fronts,22 a legislative session which was over by April 1,

21 Although the DOJ cites earlier versions of metro Atlanta’s

Sixth District in its brief (DOJ Brief at 32-33), its rejection

letters make no reference to it. Its configuration is unremarkable.

The district had to split counties due to one-person one-vote and

the need to maintain the majority-minority Fifth District.

22 Absent DOJ preclearance, a State must obtain a declaratory

judgment under Section 5 from the District Court for the District

of Columbia before a redistricting law can take effect. If the

failure to obtain preclearance results in a malapportionment, the

State is subject to suit. In Georgia, such a suit was filed on

February 12, 1992 in the U.S. District Court in Atlanta. The case,

Jones v. Miller, C.A. No. 1:92-CV-330-JOF, was filed by Republican

interests seeking to have the Court draw the State’s Congressional

district lines. The complaint also alleged a violation of Section 2

of the VRA and sought to have the Court draw “the maximum

number of majority black districts” which could be drawn. PI.

Ex. 80, p. 4. The Court in Jones had indicated that, if a plan

was not precleared by the close of the legislative session, it would

“commence drawing a plan” on April 3, 1992. P.I. Tr. 148; Tr.

V, 23.

The State Defendants moved to dismiss the Complaint in Jones

v. Miller on February 20, 1992. It labelled the maximization effort

“legally unsupportable” (PL Ex. 81, at 5) and asserted that “ [t]his

amounts to nothing more than a complaint that the State should

have, but has not, sought proportional representation for minority

citizens as a goal.” Id. at 17. The State Defendants lambasted the

claim as “not only unprecedented, but dangerous to the political

process in this nation.” Id. at 18. They noted how the resulting

23

candidate qualifying which was set to begin on April 27,

a primary election in July and a general election in

November, the State simply folded. Without formal com

mittee review in either the House or Senate, the Georgia

General Assembly hastily passed a third plan precisely

as the DOJ had laid it out in its March 20 letter. This

third plan was hand-carried to Washington on April 1,

1992. A letter granting preclearance was issued the

following day.

In strictly numeric terms, Georgia’s 1992 congressional

redistricting plan was the proverbial political feast for

blacks. Even though Georgia’s black VAP was 24.59%

for the State’s total VAP, majority-minority districts con

stituted 27.27% of the State’s eleven districts. In the

Eleventh District, the lumping together of distantly lo

cated blacks and the extensive surgery to avoid whites

resulted in a saturated district containing a black popu

lation of 64.07% and a black VAP of 60.36%.23

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Incantations of historical discrimination cannot auto

matically conjure up remedial action. Governments must

quantify the present day effects, if any, and insure there

is a tight fit between the continuing consequences of the

past discrimination and the remedy being implemented.

“racial polarization would encourage candidates of one race to be

unresponsive to the needs or wishes of another race”, thereby

breeding “extremism in both races to the detriment of all citizens.”

Id. at 19. A Max Black plan in the State Defendants’ words, “will

most certainly have the effect and result of diminishing minority

effectiveness in the political process.” Id. at 4. There are astonish

ing words in light of the positions taken by the State Defendants

in this case.

23 The impact of racially gerrymandering congressional district

lines for the purpose of creating majority-minority districts has

a dramatic impact on the VAP in the remaining districts. These

districts are now all overwhelmingly white in composition. Black

VAP in these districts ranges from 3.47% to 20.32%, with the

average being 12.9%. The racial polarization about which the

State Defendants spoke so eloquently in Jones v. Miller, supra, has

come to fruition.

24

In Georgia, the “remedy” was maximization, both of

the number of majority black districts and the minority

populations included within them. There is no connec

tion between the “Max-Black” benchmark used by the

DOJ and the narrow tailoring required whenever race

conscious remedies are invoked, unless narrow tailoring

is defined as proportional representation of the races. To

argue otherwise is to fall victim to an entitlement men

tality that demands indefinite dividends from a national

debt that was truly due to past generations.

Appellees strongly disagree with the thesis of the State

Defendants’ appeal which argues that the existence of any

non-racial factor which influenced, however slightly, any

twist or turn of the district’s boundary provides an ex

emption from the teachings of Shaw v. Reno. Unless a

district is 100% black, there will always be some bit or

piece of boundary not drawn solely to segregate the races.

For example, it might be a land bridge moving the dis

trict from one concentration of minority voters to other

distant populations. The racial purpose is still the same.

Racial gerrymandering occurs when the State draws a dis

trict that artificially manipulates non-compact dispersed

minority populations into a majority black district with

out regard for the State’s traditional districting principles.

The test of such a districts legality begins with the Vot

ing Rights Act, but ends with the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Under the Fourteenth Amendment, racial classifications

are “presumptively invalid and can be upheld only upon

extraordinary justification.” Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). The racial gerrymander of

voting districts must be subject to the same constitutional

scrutiny as any other legislative use of race. Shaw clearly

so held. We should not turn away from the principles

that give primacy to our constitution because the siren

song of racially proportional representation deafens us to

the subtle, but ultimately racial plea Intervenors make to

exempt majority-minority districts from constitutional ac

countability.

25

Shaw v. Reno catalogs just why Appellants’ vision of

America’s political landscape is inconsistent with our con

stitutional limitations on the use of racial classifications

as a basis for legislation. Congress has defined the extent

to which the federal government will involve itself at the

State ballot box with the passage of the Voting Rights

Act. Congress never dreamed this Act would mutate into

a justification for racial gerrymandering to further the

DOJ’s mandate of proportional racial representation via

a de facto affirmative action program purportedly de

signed to redress “past discrimination”.

The Abrams Intervenors would eviscerate Shaw by de

nying Plaintiffs’ standing. Do Appellants truly believe

America is better off politically segregated because the

end result may be more Black office holders? They seek

to legitimize the gerrymander as “benign” discrimination

when the tools used to fashion the racial gerrymander

are straight out of Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339

(1960) and Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

The old rallying cry of ‘separate but equal’ has been

reincarnated in the ‘separate but maximized’ demands

of the Intervenors. Justice Douglas phrased it best, calling

it the “separate but better off theory.” Wright v. Rocke

feller, 376 U.S. 52, 61-62 (1964).

Because of the extensive fact finding critical to any

analysis of this type of claim, the District Court’s judg

ment as to the existence of a bizarre district that is the

product of racial gerrymandering must be affirmed unless

clearly erroneous. And since the State has declined to de

fend this district once strict scrutiny is applied, the out

come of this case should be clear.

ARGUMENT

I. PLAINTIFFS HAVE STANDING TO CHALLENGE

RACIAL GERRYMANDERING

Leary of mounting a frontal assault to reverse Shaw

so soon after its announcement, the Abrams Intervenors’

chosen strategy is to limit its reach. To deny Plaintiffs’

standing would completely eviscerate Shaw and redirect

us from the path Shaw has blazed towards the color-

blind society all parties acknowledge to be the ultimate

goal.

Only the Abrams Intervenors have raised the issue of

standing before this Court.124 Their argument is a simple

one—Appellees have purportedly suffered no “individual

harm” and therefore lack the requisite standing to chal

lenge a majority black voting district constructed by

means of a racial gerrymander.

The Abrams Intervenors’ “individual harm” argument

is really no more than a restatement of the dissenting

view in Shaw that the plaintiffs suffered no “cognizable

injury.” Shaw resolved that issue by untethering the in

dividual harm suffered “[w]hen voting districts are care

fully planned like racial wards” (Hays v. Louisiana,

Case No. 92-1522, Slip Opinion, at 10 (on remand))

from the concept of group harm inherent in the vote

dilution setting relied upon by the dissenting Justices.

Notwithstanding stare decisis, the Abrams Intervenors

effectively ask this Court to overrule Shaw after the ink

has barely dried.35

The theory is a dangerous one because of its conse

quences if it were ever accepted. Practically speaking, no 24 25 * *

24 In light of Shaw v. Reno, the District Court denied their Mo

tion to Dismiss for lack of standing in its entirety. Abrams J.S.

App. 104-111. As to the voters, the three judge Court unanimously

stated that the Motion “borders on frivolous.” Abrams J.S. App.

110. No post-N/mw district court has denied voters standing to

challenge the constitutionality of a congressional redistricting

scheme. See Hays v. Louisiana, 839 F. Supp. 1188 (W.D. La.

1993) ; Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D. N.C. 1994); Vera

v. Richards, 861 F. Supp. 1304 (S.D. Tex. 1994).

25 The District Court’s opinion acknowledges that, if Plaintiffs’

claim were considered solely in the context of vote dilution or inter

ference with their ability to cast a ballot, these Plaintiffs have

suffered no individual harm. J.S. App. 33. The Court, correctly

observed, that Shaw was not addressing these harms, but the harm

which occurs when the state “reinforces racial stereotypes and

threatens to undermine our system of representative democracy by

signaling to elected officials that they represent a particular racial

group rather than their constituency has a whole.” J.S. App. a t 32,

citing Shaw, 113 S.Ct. at 2828.

26

27

voter could ever challenge a racially gerrymandered ma

jority minority district. This approach would sterilize

Shaw v. Reno and wrongly insulate patently unconstitu

tional racial classifications in the context of voting dis

tricts from judicial review.

The argument also misperceives the nature of Plain

tiffs’ claim. Shaw v. Reno clearly recognizes a voters’

entitlement to challenge the use of racial classifications

in the creation of voting districts. As the District Court

unanimously recognized, “the cases stress that unlawful

racial gerrymandering and its resulting balkanization is

harmful to citizens of all races. The injury flowing to

an individual so classified for voting purposes is mani

fest from Shaw.” Abrams J.S. App. at 11. This is not

a vote dilution case brought by white voters. Plaintiffs

bring the “analytically distinct claim” recognized in Shaw

that the redistricting plan under review cannot rationally

be understood as anything other than an effort to segre

gate voters into separate voting districts on the basis of

their race without sufficient justification. Shaw, 113 S.Ct.

at 2830.

Stripped to the bare wood, the Abrams’ argument on

standing is but a contention that overall proportionality

—i.e., matching the percentages of majority white and

majority black districts with the racial demographics of

the entire state’s population— negates any basis for con

stitutional scrutiny. They would forgive all intentional,

race-based line drawing which creates majority black dis

tricts no matter how egregious the gerrymandering.®8

This modern day version of “separate but equal” can

not be squared with the precedents of this Court premised 26

26 The standing defense parallels the increasingly time worn,

if not now obsolete, contention that deployment of racial classifica

tions perceived as beneficial to the minority are considered “benign”

racial discrimination exempt from strict scrutiny. The Court has

rejected this contention time and time again. See e.g., Richmond

v. J. A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989) ; Wygant v. Board of

Education, 476 U.S. 276 (1986). Every post-STwiw District Court

decision has rejected the argument.

28

on the nondiscrimination paradigm which “embodies the

idea that race-dependent decisions are unacceptable ex

cept in the most unusual and compelling circumstances.”

Blumstein, Defining and Proving Race Discrimination:

Perspectives on the Purpose v. Results Approach from

the Voting Rights Act, 69 U.Va.L.Rev. 633, 638 (1983).

This principle has been a central feature of this Court’s

equal protection jurisprudence combatting government-

sponsored separation of the races since Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).127 In Shaw, the

Court made clear the non-discrimination principle ap

plied equally to voting districts.

In Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), this Court

found Virginia’s anti-miscegenation statute barring inter

racial marriage unconstitutional. The Court rejected the

State’s argument that, since the law applied to white and

black citizens alike, there was no violation of equal pro

tection. The constitutional issue did not turn on proof

of the law’s effect (or lack thereof) on any particular

racial group but on the government’s sponsorship of

racial classifications. The Court’s decisions rejecting

race-based jury selection, regardless of what race is being

excluded, make the same point. Hernandez v. New York,

500 U.S. 352 (1991); Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S.

79 (1986).

Plaintiffs challenging intentionally-crafted, drastically

irregular black majority voting districts possess the same

credentials to complain as the Loving plaintiffs. While

there is no constitutional right to vote in any particular

election or to be a member of any particular district,

voters do have grounds to complain if the district in which

they vote cannot rationally be understood as anything

other than an effort to segregate voters into separate vot

ing districts on the basis of their race without sufficient 27

27 See e.g., Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971) (swimming

pools) ; Evans v. Abney, 396 U.S. 435 (1970) (parks); Gayle v.

Browder, 352 U.S. 903 (1956) (transportation) ; Mayor of Balti

more v. Dawson, 350 U.S. 877 (1955) (beaches) ; Holmes v. Atlanta,

350 U.S. 879 (1955) (golf courses).

29

justification. Under the Abrams’ view of standing, the

State could assign its citizens into racially segregated dis

tricts, loosened from all relevant geographical moorings, in

order to achieve proportionality. Simply put, the argument

makes no sense. If a citizen and registered voter in a gerry

mandering congressional district cannot complain of the

constitutional violation enunciated in Shaw, who can?128

The Abrams Intervenors finally argue that white citi

zens should not be able to complain about being included

in a majority black district. That is but an exercise in

rhetoric. It is the artificiality of the district stemming

from the intentional manipulation of its racial makeup

that raises the constitutional ante to the level of strict

scrutiny. While the Intervenors scoff at the stigmatic harm

a voter suffers by being included in what the public sees

as a racially rigged district, Plaintiff Henry Zittrouer

gave poignant testimony about what it was like to be

irrelevant to the congressional politcal process, to know

you and your family now live in a spindly land bridge

made up, in large part, of uninhabited swamp land that

is politically divorced from your home county. He is

separated from his relatives by only a dirt road; but that

defines the dividing line between congressional districts.

Tr. V, 26-29. Henry Zittrouer became a brick on the

highway of electoral busing. Constitutionally, he deserves

the right to have his case heard.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT’S DETERMINATION

THAT THE ELEVENTH DISTRICT IS THE PROD

UCT OF RACIAL GERRYMANDERING IS NOT

CLEARLY ERRONEOUS

The State Defendants no longer pretend the Eleventh

District can survive strict scrutiny.09 Instead, the State 28 29