Salone v. USA Brief for Plaintiff Appellant

Public Court Documents

May 2, 1980

27 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Salone v. USA Brief for Plaintiff Appellant, 1980. b7a83786-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b14be54-5d8a-46e2-94d7-23a08d9fa723/salone-v-usa-brief-for-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

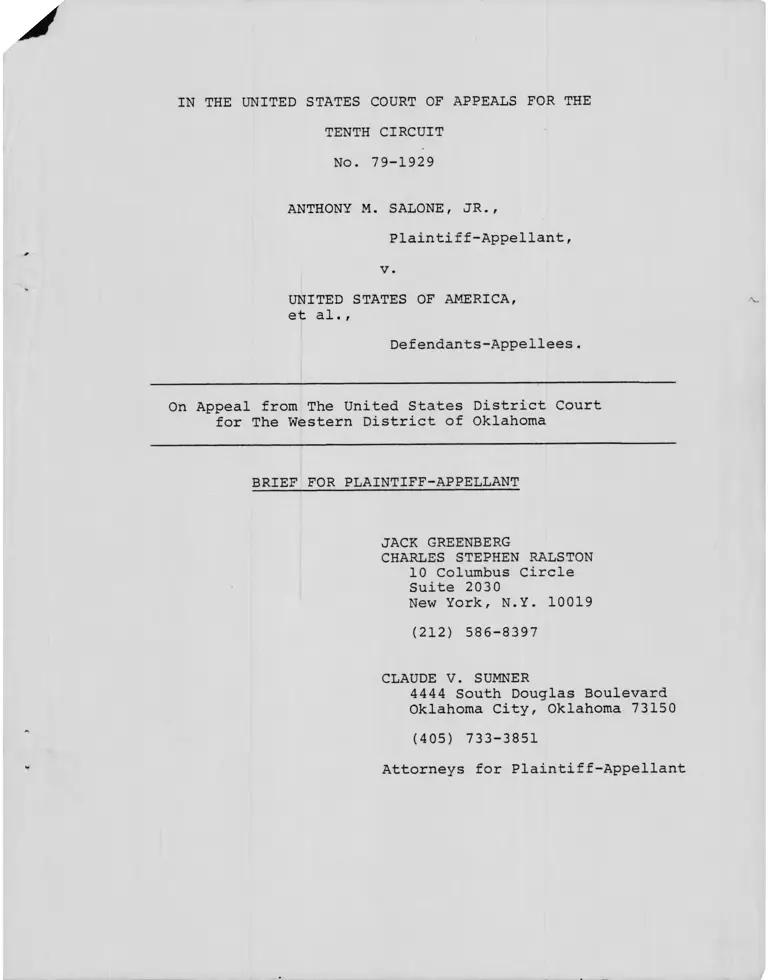

TENTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-1929

ANTHONY M. SALONE, JR.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

On Appeal from The United States District Court

for The Western District of Oklahoma

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

(212) 586-8397

CLAUDE V. SUMNER

4444 South Douglas Boulevard

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73150

(405) 733-3851

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

I N D E X

Questions Presented ............................................. 1

Statement of The Case

A. Course of The Proceedings............................. 2

B. Facts

1. Adequacy of the R e l i e f ........................... 6

2. Attorneys' F e e s .................................. 10

ARGUMENT

I. Plaintiff Was Not Awarded The Full Relief to Which

He Is Entitled under Title V I I .......................12

II. The Amount of Attorneys' Fees Should Have Been

Determined on The Basis of The Time Spent And A

Reasonable Hourly Rate .............................. 18

Conclusion...................... 22

Certificate of Service ........................................ 23

Table of Cases

Albemarle Paper Co, v. Moody, 422 U.S, 405 (1975) . . . . 12, 22

Allen v. Amalgamated Transit Union Local 788, 554 F .2d 876

(8th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 891 (1977)........... 18

Bachman v. Pertschuk, 19 EPD 1(9044 (D.D.C. 1 9 7 9 ) ........... 2 0

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d 437

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ........................................ 13, 14

Booker v. Brown, ____ F.2d ____ (10th Cir., April 7, 1980) . . 21

Brown v. Culpepper, 559 F . 2d 274 C5th Cir, 1 9 7 7 ) ........... 20

Cannon v. University of Chicago, U.S. , 60 L.Ed, 2d

560 (1979)................................................. 19

Page

i

Page

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976) 3

Copeland v. Secretary of Labor, 414 F. Supp. 647 (D.D.C.

1976) ................................................... 15

Cross v. Board of Education, 395 F, Supp, 531, CP, Ark,

17

Day v, Mathews, 53Q F,2d 1083 CD.C, Cir, 1976) 14

Evans v. Sheraton Park Hotel, 503 'F.2d 177 (D.D.C, 19741 , , 18

Fountila v. Carter, 571 F.2d 487 C9th Cir, 19781 , , , , , , 18

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co,, 424 U,S. 747 (.1976112,14,17

Hairston v, R & R Apartments, 510 F,2d 1Q9Q (7th Cir. 19.751, 18

Harkless v, Sweeny Independent School District, 608 F,2d 594

(4th Cir. 1 9 7 9 ) .................... , , , , , , , , , ,20, 21

Hernandez v, Powell, 424 F. Supp, 479 (D, Tex. 19771 , , 15, 17

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc,, 488 F,2d 714 C5th

Cir, 1 9 7 4 ) .......................................... , , , 1,18

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co,, 491 F,2d 1364 C5th

Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) .............................................. 13, 14

King v. Greenblatt, 560 F .2d 1024 (1st Cir. 1977) , , , , , 18

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S, 40Q (1968) . . . 22

Ni.tterright v. Claytor, 454 F, Supp, 13Q (D.D.C, 1978) , , . 15

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis City Schools, 611

F . 2d 624 (6th Cir. 1979.) .............. 18

Parker v, Califano, 561 F,2d 320 (D,C, Cir, 1977), , , 19,20,21

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co,, 535 F,2d 257 (4th Cir,

1 9 7 6 ) ................................................. .. , , 17

Prate v, Freedman, 583 F,2d 42 (2d Cir, 1978) , , , , , , , 18

Richerson v, Jones, 551 F,2d 918 (3rd Cir, 1977) , , 14,15,16,17

Rodriguez v. Taylor, 569 F.2d 1231 (3rd Cir, 1977) , . , , , 18

Selzer v. Berkowitz, 477 F, Supp, 686 (S.D.N.Y, 1979) , , , 2Q

Skelton v, Balzanq, 424 F. Supp, 1231 (D,D,C, 1976) , , , , 17

lx

Page

Stallings v. Container Corp. of America, 75 F.R.D. 511 (D.

Del. 1 9 7 7 ) ................................................... 17

Taylor v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 524 F.2d 263 (10th Cir.

1 9 7 5 ) ..................................................... 1 ,18

Walston v. School Bd. of City of Suffolk, 566 F .2d 1201

(4th Cir. 1 9 7 7 ) ............................................. 18

Other Authorities

Civil Rights Attorneys' Fee Act of 1976 .................... 18

5 C.F.R. §713.221(b)(2) 8

29 C.F.R. §1613.221 (b) ( 2 ) .................................... 8

H. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong. , 2d Sess. p. 8 . . . . . . . 19

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong. 2d Sess., p . 6 ......... 18, 21

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 .......................................... 2

iii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

TENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 79-1929

ANTHONY M. SALONE, JR.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from The United States District Court

for The Western District of Oklahoma

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

Questions Presented

1. Did the District Court grant adequate relief to

a federal government employee who was successful in his claim

that he had been discriminatorily denied promotions in 1970 and

1972 in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964?

2. Did the District Court err by calculating attor

neys' fees as a percentage of the back pay recovered instead of

on the basis of the standards set out in such cases as Johnson

v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974),

and Taylor v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 524 F.2d 263 (10th Cir. 1975)?

1

Statement of The Case

A. Course of The Proceedings

This is the second appeal in an action brought under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16.

Plaintiff-appellant, Anthony M. Salone, Jr., is a black civilian

employee of the United States Air Force at Tinker Air Force Base

in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. This action was commenced in 1973

after a final decision of the Civil Service Commission affir

ming the decision of the Department of Air Force denying his

claim that he had been discriminated against on the basis of race

with regard to certain employment opportunities and that he had

suffered reprisal because he had filed an earlier complaint of

discrimination. During the first administrative processing of

the complaint a Civil Service Commission Complaints Examiner,

following a hearing, had recommended that the Department of the

Air Force find that plaintiff had been discriminated against

and had suffered reprisal (Defendants' Exhibit 1, p. 27).

Despite this recommendation, the Air Force found to the contrary,

requiring the filing of the present action.

The United States filed a motion for summary judgment

based solely on the administrative record and decision of the

agency. The District Court granted the motion, holding that the

plaintiff was not entitled to a trial de novo of his claims of

discrimination and reprisal. That decision was affirmed by this

2

Court (511 F,2d 902 Cl9 7 5) )_ and a petition for writ of cer

tiorari was filed in the United States Supreme Court, The

decision of this Court was vacated and the case remanded

for reconsideration in light of the Supreme Court's decision

in Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976), holding that

federal employees are entitled to a trial de_ novo of their

claims of discrimination in actions brought under Title VII,

426 U.S. 917 (1976) .

On remand to the District Court the case was

first remanded to the United States Civil Service Commission

for further consideration (Order of Remand, March 28, 1977)

(Rec. on Appeal, p. 55) The Civil Service Commission in

turn sent the case back to the agency for a new decision.

The agency again rejected the complaints examiner's holding

with little elaboration. Therefore, a second action was

filed in the District Court and the two actions consolidated

for trial.

In March, 1979, a five-day trial on the merits of

the claims was held, based on live testimony and documentary

evidence, including the full record of the administrative

processing of the complaint. At the trial the United States

did not contest the fact that plaintiff had been discriminated

against because of his race. Indeed, the government's Pro-

3

Thus, theposed Findings of Fact specifically so acknowledged,

primary issue was the relief to which plaintiff was entitled.

Plaintiff had consistently urged that he should be

put in a higher GS level on the ground that in the absence of

the earlier discrimination, he would have advanced similarly to

comparable white employees who had not been discriminated

against.

The District Court issued an opinion holding that

plaintiff had been discriminated against, that he was entitled

to be retroactively promoted to a GS-7 as of 1970 and a GS-8

step 1 as of 1972, and was also therefore entitled to back pay

to make up the difference between those salaries and the

1/

1/ The government's proposed findings included the following:

4. That the plaintiff has been labeled as a

troublemaker in his work environment because of his

filing of discrimination complaints and has been

reprimanded more than usual for his mistakes in his

job performance.

5. That there existed at Tinker Air Force

Base at the times complained of by plaintiff racial

discrimination in the performance appraisals, pro

motions and job assignments of blacks in civilian

employment.

* * * *

18. That the plaintiff has been a victim of

racial discrimination in his employment at Tinker

Air Force Base during the times complained of by the

plaintiff.

Defendants' Proposed Findings of Fact, pp. 2-3 (Record on Appeal,

pp. 79-80).

4

salaries received as a GS-5 employee (Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law, April 25, 1979, p. 4; Rec. on Appeal,

p. 99 ) • At a hearing on May 3, 1979 , the Court announced that

any counsel fee recovery would be limited to one-third of the

back pay recovery (Transcript of Proceedings, pp. 7 90-91 )_•

Subsequently, the Court entered a judgment granting a total of

$15,544.32 in back pay and $5,181.44, or one-third, in counsel

fees (Rec. on Appeal, pp. 106-07),

A motion to alter or amend the judgment was filed

raising two issues. First, it was urged that plaintiff should

have been promoted to higher levels subsequent to the GS-8,

Step 1, promotion in 1972, since it had not been shown that he

would not have normally advanced but for the discrimination.

Second, it was argued that the amount of attorneys' fees was

inadequate since it did not accurately reflect the work re

quired during the two administrative proceedings, two court

proceedings and an appeal to this Court and the United States

Supreme Court necessary to obtain relief for the plaintiff.

Therefore, the calculation of attorneys' fees simply as a per

centage of the back pay recovery was inappropriate and not in

compliance with prevailing law governing the calculation of

attorneys' fees in civil rights cases (Rec. on Appeal, pp. 110

117). The District Court denied the motion to alter or amend,

holding that plaintiff-appellant would not have advanced above

a GS-8 step 1 in the time since 1972 because he was "a trouble

maker" and his work had been unsatisfactory. With regard to

5

attorneys' fees, the Court held that the amount requested was

unreasonable, but did not make any findings of fact to support

this conclusion. (Rec. on Appeal, p. 133). A timely notice of

appeal was filed (Rec. p. 134) and the case eventually placed on

this Court's calendar B.

B . Facts

1. Adequacy of the Relief

Plaintiff-appellant was hired at the Tinker Air Force

Base initially in 1947 as a wage board (or blue collar) employee.

Following a long period during which he had experienced a number

of difficulties and during which he received few promotions, he

filed a complaint of discrimination in 1967. Shortly afterwards

he was promoted to a GS-5 supply clerk position (Series GS-2005)

where he remained until 1979 (See, Def. Exhibit 1, p. 144; p. 19).

After he had received what he regarded to be an unsatisfactory

and discriminatory performance appraisal he filed the present

complaint of discrimination and reprisal.

The complaint was accepted and an investigation

followed which unearthed evidence of general patterns of dis

crimination against blacks in the job categories in question, of

a variety of improper employment practices, and of apparent acts

of reprisal against the plaintiff. Both white and black co-workers

of plaintiff attested that they believed he had suffered dis

crimination and reprisal ( See, generally, Def. Exhibit 1, pp. 9-

10, summarizing the affidavits at pp. 76, etseq.). Further, many

6

stated that various supervisors had branded him as a trouble

maker because he had filed complaints of discrimination in the

past. Nevertheless, the local officials at Tinker Air Force

Base proposed a finding of no discrimination (Def. Exhibit 1,

pp. 41-43). Plaintiff exercised his right to have a hearing

before a Civil Service Commission complaints examiner, and

following that hearing, which consumed two days early in 1973,

the complaints examiner issued a recommended decision of 23

pages based on a record of over 700 pages in which he found:

Careful review, study and consideration

of the total record compiled in this

case leads me to conclude that

Mr. Salone has been the victim of

systematic, continuous discrimination

within the Material Processing

Division. The evidence is overwhel

ming that because of previous dis

crimination complaints which he pursued

in 1967 and 1970, Mr. Salone has been

branded as a "troublemaker11 and has

in numerous respects been treated

differently from whites and, in many

cases differently from other blacks who

have not filed discrimination complaints.

Id., p . 19.

The Department of the Air Force handed down its final

decision of little more than a page on March 9, 1973. Its entire

discussion of the record and the recommended decision of dis

crimination was, "The entire record of your complaint has been

carefully reviewed and it has been determined that the evidence

therein does not support your allegations of discrimination based

on race " (Id., p. 6), Despite the requirement of the Civil

Service Commission's regulations no further explanation was given

as to why the detailed findings of the complaints examiner were

- 7

summarily rejected. As stated abovefthis result precipi

tated the present action and eventually culminated in a

five day hearing before the District Court early in 1979.

At the hearing the Court heard many of the same

witnesses who provided affidavits and who testified at the

administrative hearing in Mr. Salone's case. These wit

nesses gave testimony fully consistent with that given during

the administrative process. His co-workers unanimously testi

fied that Mr. Salone was a good and conscientious worker.

However, they had heard from various persons, particularly at

the supervisory levels, that he was "a troublemaker." Most of

those employees assumed that referred to the fact, well known

to everyone, that he had complained about racial discrimination.

None of his co-workers testified either at the trial or during

the administrative process that they themselves thought that

Mr. Salone was a troublemaker or that he did not perform his

duties well. ( See, e.g.; the testimony in the Transcript of

Trial at pp. 275, 278, 289-291; 318; 334-335; 339-340). The

only testimony to the contrary was from supervisors relating to the

period prior to 1972 ( See, e.g., Transcript, pp. 752-53.)

The supervisors charged with discrimination testified

that they had not committed any discrimination. However, the

government did not contest that discrimination had indeed taken

2/

2/ See, 5 C.F.R. §713.221(b) (2) , now 29 C.F.R. §1613.221 (b) (2) .

8

place, but rather focused on what relief Mr. Salone was entitled

to. The only testimony or evidence relating to the period after

1972 were documents showing that Mr. Salone had performed his

duties in a highly satisfactory manner, receiving performance

appraisals in the high nineties on a scale of 100. Indeed, in

1976 he was recommended for an outstanding performance rating.

(Defendants' Exhibit 2).

Mr. Salone himself testified that he believed he

would have advanced to the GS-14 or 15 level if he had been

provided equal employment opportunities earlier in his career.

He specifically noted that his qualifications were equal to or

superior to those of whites who had so advanced. Thus, he had

more than three years of college education as compared to high

school diplomas held by some of the white supervisors.

The testimony further showed that at Tinker Air

Force Base it was not necessary to apply for positions as they

became available. Profiles were developed by a computer of all

employees who had the eligibility for positions, and those

eligible were contacted to find out if they were interested in

the positions (Transcript, p. 235; plaintiff's Exhibit 5,

pp. 6-7). Mr. Salone had been contacted in the period from 1972

for some GS-6 positions, but had declined some on the ground

that they were dead-endand could not lead to further advancement

(Transcript, pp. 687-88). He had not declined others and

although he had been considered for a number of GS-6 positions

9

he had never been promoted to one (Defendants' Exhibit 2).

The District Court in its findings of fact and in

its denial of the motion to alter or amend the judgment found

that Mr. Salone was in fact a troublemaker and did not perform

his duties satisfactorily, notwithstanding the absence of any

testimony to that effect. Indeed, these findings were directly

contrary to the government's admissions in their proposed

findings of fact that he had been "labeled as a troublemaker

. . . because of his filing of discrimination complaints" and

that "the plaintiff's performance in his job was satisfactory "

(Rec. pp. 79 and 80).

Subsequent to the Court's decision Mr. Salone was

put in the position of a Freight Rate Specialist (Series GS-

2131, 7/12) at the GS-8, step 6 level, retroactive to 1972.

According to the official position classification standards of

the United States Civil Service Commission (now the Office for

Personnel Management) the freight rate specialist position

ranges from GS-7 to GS-12 depending upon the level of respon

sibility. Thus, it is a job series through which promotions to

higher levels may be achieved because of an increased level of

responsibility and performance without the necessity of com

petitive bidding (See, Plaintiffs' Exhibit 5, p. 5) ,

2. Attorneys' Fees

As noted above,this action has taken more than seven

years solely because of the Air Force's continued refusal to

acknowledge clearly established discrimination until the trial

in 1979. Because of the initial decision of the District Court

10

to deny relief without a full trial, the case had to be taken

to this Court and ultimately to the Uni ted States Supreme

Court. Upon remand there were further administrative pro

ceedings; because relief was again not provided a five-day trial

was required.

Following the District Court's announcement that the

fee award would be limited to a percentage of the back pay

award and an entry of an order to that affect, a motion to alter

or amend was filed with affidavits showing the number of hours

necessitated by the multiplicitous proceedings. Total fees in

3/

the amount of $20,045 were requested. It is uncontradicted that

Mr. Salone had paid out of pocket to the attorneys who first

handled his action through the initial appeal to this Court fees

of $4,515.00 (Affidavit of Anthony M, Salone, Jr.). Thus, vir

tually the entire amount awarded would be used up to compensate

for the work done before the remand and the further proceedings

that eventually lead to success in the lawsuit, with either the

plaintiff or his trial counsel having to absorb a loss of $6,000.

The Government at no point contested the reasonableness of the

hours spent nor the hourly rates requested. The Court simply

made the conclusory statement that the amount requested was un

reasonable without any findings of fact to support that

conclusion.

3/ See, Motion to Alter or Amend the Judgment, p. 6 (Record,

p. 215), for the hours claimed and the hourly rates, together

with the supporting affidavits (Record 216-230).

11

ARGUMENT

I.

Plaintiff Was Not Awarded The Full Relief

to Which He is Entitled under Title VII

The Supreme Court in Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975) held that:

It is also the purpose of Title VII

to make persons whole for injuries

suffered on account of unlawful un

employment discrimination . . . .

Where racial discrimination is con

cerned, "the [district] court has

not merely the power but the duty

to render a decree which will so

far as possible eliminate the dis

criminatory effects of the past . . . "

422 U.S. at 418. Specifically, where the injury is of an

economic character, the Court held that -

. . . The injured party is to be

placed, as near as may be, in the

situation he would have occupied

if the wrong had not been committed.

Wicker v. Hoppock, 6 Wall 94, 99

(1867) .

422 U.S. at 418-19. See also, Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976).

Thus, the courts have adopted the principle that once

it has been found that a person has been discriminated against,

then relief should be fashioned to place him in his "rightful

place." That is, to the extent possible he should be put in the

situation he would have been in if there had been no discrimination.

Further, the presumption is that the victim of discrimination would

have advanced and been promoted in the usual fashion, The employer

has the burden of demonstrating by clear and convincing evidence

12

that the employee:

would have never been advanced because

of that individual's particular lack

of qualifications for a more difficult

position or for other good and

sufficient reasons such employee would

never have been promoted. It is

apparent that whether any particular

individual would have been advanced

under a color-blind system cannot now

be determined with 100% certainty.

The court . . . will have to deal with

probabilities. Any substantial doubts

created by this task must be resolved

in favor of the discriminatee . . . .

The discriminatee is the innocent

party in these circumstances.

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d 437, 445

(5th Cir. 1974).

Thus, the discriminated against employee does not

have the burden of showing that he would have achieved a

certain level. Rather:

It is the employer who created the dis

criminatory situation which prevented

free choice in the first instance. It

is, therefore appropriate to require

the employer to show that its invidious

limitations on free mobility were not

the cause of the discriminatee's current

position in the economic ladder.

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F .2d 1364, 1380 (5th

Cir. 1974). Similarly, any doubts as to whether the dis

criminatee would have performed well enough to be advanced must

be resolved in his favor. As the Supreme Court has held:

It is true, of course, that obtaining

. . . evidence . . . [of] what the

individual discriminatee's job per

formance would have been but for the

discrimination— presents great diffi

culty. No reason appears, however,

13

why the victim rather than perpetrator

of the illegal act should bear the

burden of proof on this issue.

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 772, n. 32

(1976) .

These principles "apply with full force to the

Government as employer." Day v. Mathews, 530 F.2d 1083, 1085-

86 (D.C. Cir. 1976), citing with approval Baxter v. Savannah

Sugar Refining Corp., supra, and Johnson v, Goodyear Tire &

Rubber Co., supra. In the case of an individual federal

employee who has established discrimination, it is "'impossible

. . . to recreate the post with exactitude' . . . precisely

because of the employer's unlawful action," and, therefore,

"it is only equitable that any resulting uncertainty be resolved

against the party whose action gave rise to the problem." Day

v. Mathews, 530 F.2d at 1086. See also, Richerson v. Jones,

551 F .2d 918 (3rd Cir. 1977).

Applying these principles to the present case, it is

clear that plaintiff is entitled to additional relief. It must

be presumed that if he had been promoted to GS-8, step 1,

position on June 28, 1972, then he would have advanced in the

seven years since that time. Under the authorities cited above,

the burden was on the defendant to establish by "clear and

convincing evidence," that Mr. Salone never would have advanced

at all to a higher GS level as was normal for similarly situated

employees.

This burden was not met. As we have shown in the

statement of the facts, the District Court's conclusion that

14

Mr. Salone was in fact a troublemaker and did not perform his

job satisfactorily since 1972 is clearly not only unsupported

by the evidence, but is directly contrary to it. Documentary

evidence introduced by the government establishes that he re

ceived performance appraisals near the maximum possible; its

own proposed findings of fact admitted that he performed his

job satisfactorily. Further, the same proposed finding

acknowledge that he had been labelled a troublemaker by super

visors because he had filed discrimination complaints. The

evidence fully supported this conclusion. His peers— both

black and white co-workers— testified in 1972 and 1973 during

the administrative proceedings and again at trial in 1979 that

he was a good worker who did his job in a non-disruptive fashion,

but that he had been branded as a "troublemaker" because he

asserted his rights.

Under facts similar to those in the present case,

one court has held that where a woman had been discriminated

against, she was entitled to retroactive promotions which took

into consideration additional upgrading she would have received

in the absence of the original discrimination. Nitterright v.

Claytor, 454 F. Supp. 130 (D.D.C. 1978) (retroactive promotion

to GS-6 on July 28, 1971, GS-7 on July 28, 1972, and GS-8 on

July 2, 1976, with appropriate back pay). See also, Hernandez

v. Powell, 424 F. Supp. 479 (D. Tex. 1977); Copeland v. Secre

tary of Labor, 414 F. Supp. 647 (D.D.C. 1976). The Third

Circuit approved the principle of such relief in Richerson v.

15

Jones, 551 F.2d 918 (3rd Cir. 1977), although it reversed the

district court and remanded for further findings to support its

conclusion that the plaintiff had the specific qualifications to

advance to a GS-12 higher level supervisory position. Still, it

made it clear that the government bore the burden of showing

that even absent discrimination the plaintiff's qualifications

were such that he would not have been selected for the GS-12

position.

It is clear from the evidence here that Mr. Salone, as

an employee performing at a high level of competence, could have

advanced beyond a GS-8 position in the seven (now eight) years

since 1972 if he had not been discriminatorily denied a promotion

to that level then. First, at Tinker Air Force Base competitive

promotions were given without the necessity of employees applying

for jobs. All employees with the necessary qualifications were

automatically considered. Under federal law and Civil Service

Regulations, plaintiff would have been eligible for promotion to

a GS-9 or GS-10 position after one year in grade at GS-8, or as

of June 28, 1973. He would then have been eligible for a GS-11

after one more year as a GS-9 or 10, for a GS-12 after one more

5/

year, and so on. Although, as the Court held in Richerson, it

5/ Above the GS-11 level, an employee can advance only one

grade at a time. Below that, a jump of two grades after one

year in grade is possible. For this reason, there are compara

tively few persons in the GS-8 and GS-10 grades throughout the

federal service.

16

cannot be assumed that an employee will advance automatically

indefinitely, certainly it is more than likely that he would

have advanced above a GS-8. Certainly, in view of the reasons

given by the court below for holding otherwise, a remand as was

done in Richerson is appropriate.

Second, the particular job series into which plain

tiff was placed in 1979, retroactive back to 1972, is one that

allows a progression without competition to higher GS levels as

duties and responsibilities increase. He was placed in series

GS-2131, 7/12, (Freight Rate Technician) with grades from GS-7

6/

to GS-12. By a natural progression, therefore, he would almost

certainly have moved to a higher grade level.

To summarize, if any positions became open during the

period June 28, 1972, to the present at a higher GS-level for

which he would have been qualified, plaintiff is entitled to

retroactive promotions to them. If the positions are encumbered,

then Mr. Salone is entitled to the next available position, see

Stallings v. Container Corp. of America, 75 F.R.D. 511 (D. Del.

1977), Hernandez v. Powell, infra, Skelton v. Balzano, 424 F.

Supp. 1231 (D.D.C. 1976), with back and front pay until he assumes

it. See, Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257, 269

(4th Cir. 1976), Cross v. Board of Education, 395 F. Supp. 531 (D.

Ark. 1975) and the opinion of Chief Justice Burger, in Franks v.

Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 781 (1976).

6/ Position descriptions and qualifications, and grade levels

and the standards by which increases in grades are determined are

set out in two publications of the Office of Personnel Management

(formerly the Civil Service Commission), Handbook X-118, Quali

fication Standards for Positions Under the General Schedule, and

the Position Classification Standards for Positions Under the

General Schedule. 17

II.

The Amount of Attorneys1 Fees Should Have Been

Determined, on The Basis of The Time Spent And

A Reasonable Hourly Rate

In an action brought under Title VII, and the various

other civil rights statutes, a prevailing plaintiff is entitled

to an award of counsel fees based on a number of factors which

focus on the time spent and the quality of the work done. These

factors are set out in detail in Johnson v. Georgia Highway

Express, Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974) and Evans v. Sheraton

Park Hotel, 503 F.2d 177 (D.C. Cir. 1974), and were endorsed by

this Court in Taylor v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 524 F.2d 263 (10th

Cir. 1975) . Indeed, the courts of appeals have been unanimous

in holding that counsel fees in civil rights cases should be

governed by the Johnson standards. See, King v. Greenblatt, 560

F.2d 1024, 1026 (1st Cir. 1977); Prate v. Freedman, 583 F.2d 42

(2d Cir., 1978); Rodriguez v, Taylor, 569 F.2d 1231 (3rd Cir.

1977); Walston v. School Bd. of,City of Suffolk, 566 F .2d 1201

(4th Cir. 1977); Hairston v. R & R Apartments, 510 F.2d 1090,

1093 n. 3 (7th Cir. 1975); Allen v. Amalgamated Transit Union

Local 788, 554 F.2d 876, 884 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S.

891 (1977); Fountila v. Carter, 571 F.2d 487, 496 (9th Cir. 1978);

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis City Schools, 611 F .

2d 624 (6th Cir. 1979).

The Johnson standards were specifically endorsed by

Congress when it enacted the Civil Rights Attorneys1 Fee Act of

1976. See, S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong. 2d Sess., p. 6, and

See,

18

H. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong. 2d Sess., p. 8.— Of crucial

importance is the principle that the amount of fees should not

be geared to the monetary recovery of the plaintiff. Otherwise,

as here, the plaintiff will suffer an out-of-pocket loss as a

condition of vindicating his civil rights. See, H. Rep.

No. 94-1558, supra, at p. 9.

When various of the factors set out in Johnson and

are applied here, we urge that the amounts requested are

£/clearly reasonable. The affidavits and supporting documentation

1_ / . Although the legislative history of the 1976 Act does not

directly control interpretation of the counsel fee provision in

the 1972 Act, it is entitled to careful consideration as "'a

secondarily authoritative expression of expert opinion.'" Parker

v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320, 339 (D.C. Cir. 1977). In Cannon v.

University of Chicago, ___U.S. ___, 60 L.Ed. 2d 560, 569, n. 7,

the Supreme Court relied on the legislative history of the 1976

Act in interpreting an earlier civil rights act, stating:

Although we cannot accord these remarks

the weight of contemporary legislative his

tory, we would be remiss if we ignored these

authoritative expressions concerning the

scope and purpose of Title IX and its place

within "the civil rights enforcement scheme"

that successive Congresses have created over

the past 110 years.

8/ The factors, which are those listed in the ABA Code of Pro

fessional Responsibility, are: (1) the time and labor required;

(.2) the novelty and difficulty of the questions; (3) the skill

required to perform the legal services properly; (4) preclusion

of other employment; (.5) the customary fee; (6) whether the fee is

fixed or contingent; (7). time limitations imposed by the client

or circumstances; (_8)_ the amount involved and the results obtained;

(9) the experience,reputation, and ability of attorneys; (10) the

undesirability of the case; (11) the nature and length of the

professional relationship with the client; (12) awards in similar

cases.

19

demonstrate that counsel for plaintiffs are experienced in liti

gation and in federal EEO matters. This case required appeals

all the way to the Supreme Court on novel and important public

issues in order to vindicate the rights of the plaintiff. It

was also necessary to go through administrative proceedings and

two proceedings in the district court, largely because of the

government's adamant refusal to acknowledge the discrimination

suffered by the plaintiff until the twelfth hour. The total

time spent on these various tasks was reasonable, and the hourly

rates are appropriate for attorneys of similar experience and ex

pertise in their localities. See, Brown v. Culpepper, 559 F.2d

274 (5th Cir. 1977)($65 and $75 per hour); Harkless v. Sweeny

Independent School District, 608 F.2d 594 (4th Cir. 1979) ($75 per

hour); Bachman v. Pertschuk, 19 EPD 1[9044 (D.D.C. 1979) ($35 to

$85 per hour). Even in civil rights cases that are not class

actions, the courts have regularly awarded fees based on pre

vailing hourly rates. See, e .g ., Selzer v. Berkowitz, 477 F. Supp.

686 (S.D.N.Y. 1979) (rates up to $125 per hour); Parker v. Califano,

443 F. Supp. 789 (D.D.C. 1978)($72 per hour).

The district court failed to apply these well established

principles when it simply calculated attorneys' fees as a percentage

of the back pay award, without any consideration of the amount of

time and expertise it took to achieve the results in this case. To

begin with, pegging the counsel fees solely to the amount of back

pay fails to consider the substantial future benefits that plaintiff

will receive by virtue of his promotion. Moreover, the intangible

20

benefits of the vindication of one's civil rights are completely

discounted. Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District, 608

F.2d at 598. Thus, such a method of calculation is particularly

inappropriate in a Title VII action. Beyond that, the award

bears no relationship to the work actually done. For example, the

small amount in no way can compensate adequately for the effort

expended in the administrative process or on the appeal to this

Court and the Supreme Court, work that must be included in the

award. Booker v. Brown, ____F.2d ____(10th Cir., April 7, 1980),

The policy considerations behind the various counsel

fee provisions also militate against awarding a fee based on a

percentage of the recovery. The basic purpose of the fee statutes

is to encourage attorneys to take on the often arduous job of

enforcing the civil rights statutes. Thus, Congress' intent is

that fees be comparable to those recovered in comparable federal

litigation such as antitrust cases. S. Rep. 94-1011 (94th Cong.,

2d Sess.), p. 6. Encouraging the participation of the private

bar is particularly important in Title VII cases where the federal

government is the defendant, since enforcement of the Act is left

solely to individual employees acting as "private attorneys

general." Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320, 331 (D.C. Cir. 1977).

Awards of back pay in individual employment discrimination cases

are generally small. See, e .g ., Harkless v. Sweeny Independent

School District, 608 F.2d at 594. If fees are based on a percentagge,

they will tend to be so small as to be a disincentive to counsel

to take such cases since they will, as here, bear no relationship

21

to the work required to achieve the result.

Finally, the result in this case, as it will be in

virtually all other individual Title VII cases, is to render

either the plaintiff or his counsel out-of-pocket for fees, a

result directly contrary to the rationale of the fees provisions

as articulated by the Supreme Court:

If successful plaintiffs were routinely

forced to bear their own attorneys'

fees, few aggrieved parties would be

in a position to advance the public

interest by invoking the injunctive

powers of the federal courts. Con

gress therefore enacted the provision

for counsel fees— not simply to penalize

litigants who deliberately advance argu

ments they know to be untenable but,

more broadly, to encourage individuals

injured by racial discrimination to seek

judicial relief . . . .

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968). This

outcome is therefore inconsistent with the underlying purpose of

the Act as a whole, which is to "make persons whole for injuries

suffered on account of unlawful unemployment discrimination."

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the court

below should be reversed.

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

212-586-8397

CLAUDE V. SUMNER

. 4444 South Douglas Boulevard

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73150

405-733-3851

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

22

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served a copy of the

attached Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant by mailing the same to

Larry D. Patton, Esq,, United States Attorney and John E.

Green, Esq., First Assistant United States Attorney, 4434 United

States Courthouse, Oklahoma City, ^Oklahoma 731Q2.

0

1

Dated: May , 1980, CHARLES STEPHEN "RALSTON

Counsel for Plaintiff-

Appellant

23