Memo for the US as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 12, 1974

34 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Memo for the US as Amicus Curiae, 1974. 8673745d-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b249697-b396-4717-b333-625a92c2b649/memo-for-the-us-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

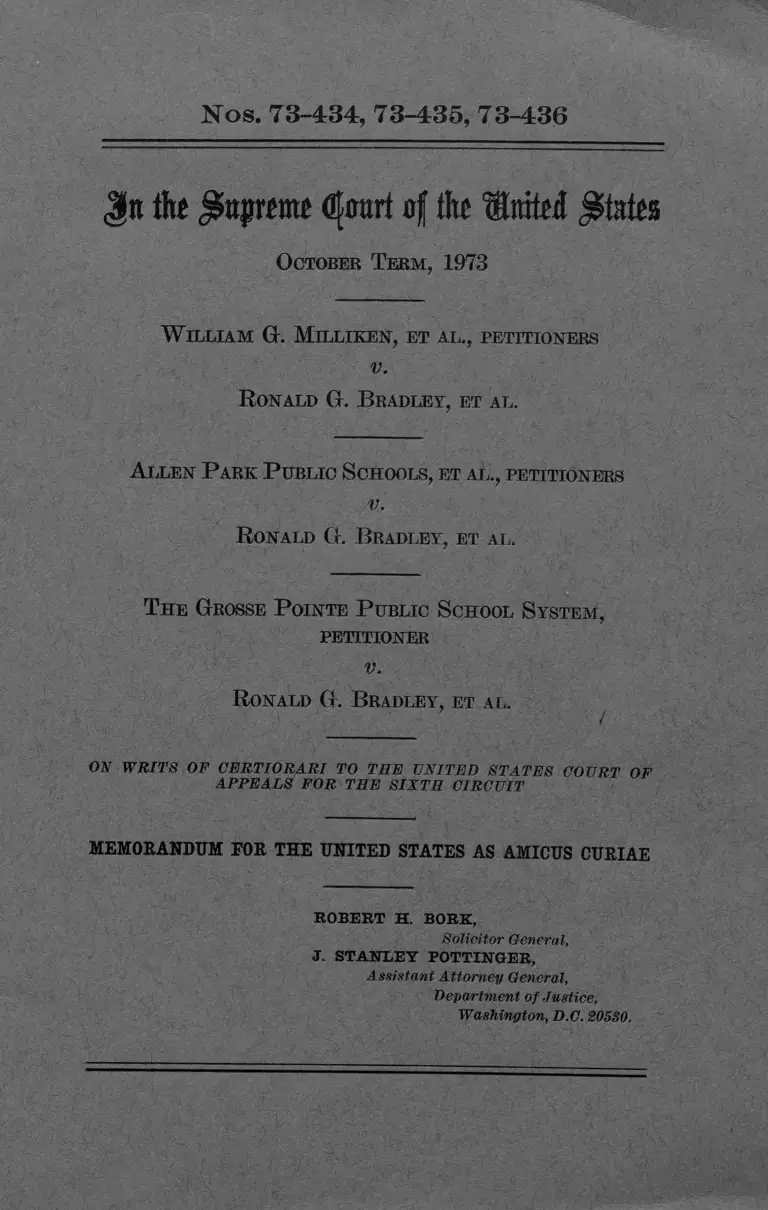

Nos. 73-434, 73-435, 73-436

Jn tftt Supreme (fourt of the tB nM States

October Term, 1973

W illiam G. M illiken, et al., petitioners

v.

R onald G. B radley, et al.

A llen P ark P ublic Schools, et al., petitioners

v.

R onald G. B radley, et al.

T he Grosse P ointe P ublic School System,

PETITIONER

V.

Ronald G. B radley, et al.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

MEMORANDUM FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

ROBERT H. BORK,

Solicitor General,

J. STANLEY POTTINGER,

Assistant Attorney General,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20580.

I N D E X

Page

Interest of the United States_________________ *__________ 1

I. Introductory statement_________________________ 2

II. The remedy for unconstitutional school segregation

may extend beyond the boundaries of a single dis

trict only if, and to the extent that, the violation

has directly altered or substantially affected the

racial composition of schools in more than one

district___________________________________________ 11

III. The record in this case does not support the broad

metropolitan-wide remedy contemplated by the

court of appeals_________________________________ 15

Conclusion______________________________________________ 27

CITATIONS

Cases: ... . .. .

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19___________________________________________ 2

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F. 2d 897___________________ 3, 4

Bradley v. Milliken. 468 F. 2d 902, certiorari denied,

409 U.S. 844_____________________________________ 3, 5

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, Vir

ginia, 338 F. Supp. 67, reversed, 462 F. 2d 1058,

affirmed sub. nom. School Board of the City of Rich-

Richmond v. State Board of Education, 412 U.S. 92_ 2,

7, 12, 14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483__________ 2

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1_________________________ 2

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683____________ 2

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430_____________________________________ 2

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County,

429 F. 2d 364_____________________________________ 14

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado,

413 U.S. 189_____________________________________ 2, 18

(i)

532-849— 74- ■1

II

Cases— Continued page

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455_________________ 2

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 1________________________________________ 5

Spencer v. Kugler, 404 U.S. 1027, affirming 326 F.

Supp. 1235________________________________________ 11

Swann v. Boaid of Education, 402 U.S. 1_______ 2, 11, 15, 23

United States v. Missouri, 363 F. Supp. 739__________ 14

United States v. Scotland Neck Boaid of Education,

407 U.S. 484______________________________________ 14

United States v. Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043, affirmed

447 F. 2d 441, certiorari denied sub. nom. Edgar v.

United States, 404 U.S. 1016______________________ 14

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451— 2, 14

Statutes:

P.L. 92-318, Section 803, 86 Stat. 235, 372___ 1_____ 2

28 U.S.C. 1292(b)_____________________________ 8

28 U.S.C. 2403______________________________________ 2

42 U.S.C. 2000c-6___________________________________ 2

42 U.S.C. 2000d_____________________________________ 2

42 U.S.C. 2000h-2___________________________________ 2

Jit the j&tpreme d|mtrt of the United States

October Term, 1973

No. 73-434

W illiam G. M illiken, et al., petitioners

v.

R onald G. B radley, et al.

No. 73-435

Allen P ark P ublic Schools, et al., petitioners

v.

R onald G. B radley, et al.

No. 73^36

T he Grosse P ointe P ublic School System,

petitioner

v.

Ronald G. B radley, et al.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR TIIE SIXTH CIRCUIT

MEMORANDUM EOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

The United States has substantial responsibility un

der 42 U.S.C. 2000c-6, 2000d, and 2000h-2, with respect

(i)

2

to school desegregation. This Court’s resolution of the

issues presented in this case will affect that enforce

ment responsibility. The United States participated as

an intervenor in this case in the court of appeals1 and

has participated as amicus curiae or as a party in

most of this Court’s previous school desegregation

cases, including Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483; 349 U.S. 294; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1;

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683; Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430; Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19; Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S.

1; Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451; School Board of the City of Richmond v. State

Board of Education, 412 U.S. 92; Keyes v. School Dis

trict No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413 U.S. 189; and Nor

wood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455.

I

in t r o d u c t o r y s t a t e m e n t

The issue in this case is whether the remedy for

illegal racial segregation of the Detroit public schools

may properly include a cross-district pupil assignment

plan between the Detroit school district and neighbor

ing districts, where the record does not show whether

1 The United States intervened in the court o f appeals pur

suant to 28 U.S.C. 2403, because the constitutionality o f an Act

of Congress (Section 803 of P.L. 92-318, 86 Stat. 235, 372) had

been called into question. The court of appeals found it un

necessary to consider the applicability or constitutionality o f the

statute in question (Pet, App. 189a), which, by its terms, ex

pired on January 1, 1974.

3

constitutional violations affected the racial composition

of schools outside the Detroit district and where the

suburban districts have had no effective opportunity

to be heard on the propriety of a metropolitan-wide

remedy.

This case began in August 1970 when certain of the

respondents, primarily black parents and their chil

dren who attended schools in the Detroit public school

system, sued city and state officials, alleging that the

officials had pursued a policy and practice of racial

discrimination in the operation of the Detroit public

schools, which had resulted in a racially segregated

school system.2 The plaintiffs sought, inter alia, an or

der requiring the defendants to present a plan “ for the

elimination of the racial identity of every school in the

[Detroit] system and to maintain now and hereafter

a unitary, nonracial school system77 (Pet. App. 15a).

The case was twice before the court of appeals on pre

liminary matters (433 F. 2d 897, 438 F. 2d 945), and a

trial on the merits was held from April to July of

1971.

In September 1971, the district court entered its

findings of fact and conclusions of law on the issue of

racial segregation in the Detroit schools (Pet. App.

17a-39a). It found that the Detroit school board had

engaged in official acts of racial discrimination that

2 The complaint also alleged that a recently-adopted Act of

the state legislature unconstitutionally interfered with a volun

tary plan of desegregation adopted by the Detroit Board of

Education (Pet. App. 8a-10a). The Act was held unconstitu

tional by the court of appeals in an earlier phase of this liti

gation (433 F. 2d 897).

4

had contributed to racial segregation in the school

system. The board’s use of optional attendance zones in

areas undergoing racial transition and between schools

of opposite predominant racial composition “ allowed

whites to escape integration” {id. at 25a) ; the board

transported children on a racially discriminatory

basis {ibid.) ; it gerrymandered attendance zones and

altered grade structures “ in a manner which has had

the natural, probable and actual effect of continuing

black and white pupils in racially segregated schools”

{id. at 25a-26a); and it pursued discriminatory

school construction policies {id. at 27a, 28a).

The court also found that official acts of state agen

cies contributed to the racial segregation in Detroit’s

schools. The enactment of state legislation rescinding

a voluntary plan of desegregation that had been

adopted by the Detroit board was designed, the court

held, “ to impede, delay and minimize racial integra

tion in Detroit schools” {id. at 28a) ; 3 and state offi

cials, as well as the Detroit board, participated in

racially discriminatory decisions concerning school

construction {ibid.).1 The court also concluded that

Michigan law vests in the State Board of Education

“ supervision over all public education” {id. at 36a).

3 The details of the statute are set forth in the opinion of

the court of appeals holding it unconstitutional (433 F. 2d

897).

4 The court also noted that state law did not provide funds

or authority for the transportation of pupils in Detroit, though

it did provide for transportation of some pupils attending

suburban districts. The court stated that this “ and other fi

nancial limitations, such as those on bonding and the working

o f the state aid formula whereby suburban districts were able

to make far larger per pupil expenditures despite less tax

Turning to tlie question of an appropriate remedy

for the constitutional violations, the district court ad

dressed a pending motion by intervening defendants

to join as additional parties defendant 85 school dis

tricts in the three counties surrounding Detroit, on

the ground that effective relief could not be achieved

without their presence (see I App. 119-129).5 The

court deferred ruling on that motion, pending the

submission of proposed remedies by existing parties

(Pet. App. 38a-39a). In a subsequent hearing, the

court stated that “ perhaps only a plan which em

braces all or some of the greater Detroit metropolitan

area can hope to succeed” (id. at 40a). It ordered the

Detroit school board to submit a proposed plan for

desegregation within its district and ordered the state

defendants to submit a “ metropolitan plan of deseg

regation” (id. at 43a).6

Before ruling on the plans submitted by the state and

city defendants, the district court granted motions by

some of the suburban school districts to intervene in the

proceeding, but restricted their participation essentially

to advising the court on the propriety of a metropolitan

wide remedy in general and on the merits of the par-

effort, have created and perpetuated systematic educational

inequalities*’ (Pet. App. 27a). The court did not indicate

whether any such disparities had affected the racial composition

of the school districts. Cf. San Antonio Independent School

District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1.

5 “A pp.” refers to the five-volume joint appendix, each

volume o f which is separately paginated.

6 The court o f appeals held that this order was not appeal-

able (465 F. 2d 902), and this Court denied certiorari (409 U.S.

844).

6

ticular desegregation plan submitted to the court

(I App. 204-207).

The district court thereafter issued the three rul

ings that were principally at issue in the court of

appeals.

(1) On March 24, 1972, in its ruling on the pro

priety of considering a metropolitan-wide remedy

(Pet. App. 48a-52a), the district court addressed the

question whether it could “ consider relief in the form

of a metropolitan plan, encompassing not only the

City of Detroit, but the larger Detroit metropolitan

area” (id. at 49a). It rejected both the state defend

ants’ argument that no state action caused the seg

regation of the Detroit schools, and the suburban

districts ’ contention that interdistrict relief is inappro

priate unless the suburban districts have themselves

committed violations. The court concluded (id. at

51a) :

[I ]t is proper for the court to consider

metropolitan plans directed toward the de

segregation of the Detroit public schools as an

alternative to the present intra-city desegrega

tion plans before it and, in the event that the

court finds such intra-city plans inadequate to

desegregate such schools, the court is of the

opinion that it is required to consider a metro

politan remedy for desegregation.

(2) On March 28, 1972, the court issued its findings

and conclusions on the three “ Detroit-only” plans

submitted by the city board and the plaintiffs (id. at

53a-58a). It found that the best of the three plans

“ would make the Detroit system more identifiably

Black * * * thereby increasing the flights of Whites

7

from the city and the system” (id. at 55a). From this

the court concluded that the plan “would not accom

plish desegregation” and that desegregation “ cannot

be accomplished within the corporate geographical

limits of the city” (id. at 56a). It accordingly held

that it “ must look beyond the limits of the Detroit

school district for a solution to the problem of seg

regation” (id. at 57a). Relying on Bradley v. School

Board of the City of Richmond, Virginia, 338 F. Supp.

67 (E.I). Va.),reversed,462F .2d 1058 (C.A.4), affirmed

by an equally divided Court, 412 U.S. 92, the court held

that “ [sjchool district lines are simply matters of politi

cal convenience and may not be used to deny constitu

tional rights” (Pet. App. 57a).

(3) On June 14, 1972, the district court issued a rul

ing on the desegregation area (id. at 97a-105a) and

related findings and conclusions (id. at 59a-96a). The

court acknowledged at the outset that it had “ taken no

proofs with respect to the establishment of the bound

aries of the 86 public school districts in the counties

[in the Detroit area], nor on the issue of whether,

with the exclusion of the city of Detroit school district,

such school districts have committed acts of de jure

segregation” (id. at 60a). Nevertheless, it designated

53 of the suburban school districts plus Detroit as the

“ desegregation area” (id. at 101a) and appointed a

panel to prepare and submit “ an effective desegrega

tion plan” for the Detroit schools that would encom

pass the entire desegregation area (id. at 99a). The

plan was to be based on 15 clusters, each containing

part of the Detroit system and two or more suburban

districts (Y App. 111-115), and Avas to “achieve the

532- 849— 74— 2

8

greatest degree of actual desegregation to the end that,

upon implementation, no school, grade or classroom

[be] substantially disproportionate to the overall pupil

racial composition” (Pet. App. 101a-102a).

A divided court of appeals, sitting en banc, affirmed

in part, vacated in part, and remanded for further

proceedings (Pet. App. 110a-240a).7 The court held,

first, that the record supports the district court’s

findings on the constitutional violations committed

by the Detroit board (id. at 118a-151a) and by the

state defendants (id. at 151a-157a).8 It stated that

7 The district court had certified most of the foregoing rul

ings for interlocutory review pursuant to 28 IT.S.C. 1292(b)

(I App. 265-266), and a panel of the court of appeals had

granted leave to appeal (Pet. App. 108a-109a). The case was

initially decided on the merits by a panel, but the panel’s

opinion and judgment were vacated when the court determined

to rehear the case en banc (see Pet. App. llla -112a).

s With respect to the State’s violations, the court o f appeals

held: (1) that, since the city board is an instrumentality of

the State and subordinate to the state board, the segregative

actions o f the Detroit board “ are the actions of an agency of

the State” (Pet. App. 151a) ; (2) that the state legislation

rescinding Detroit’s voluntary desegregation plan (see p. 4,

supra) contributed to increasing segregation in the Detroit

bools (ibid.) ; (3) that under state law prior to 1962 the state

iard had authority over school construction plans and must

„ ere fore be held responsible “ for the segregative results” (ibid.) ;

(4) that the “ State statutory scheme of support o f transportation

for school children directly discriminated against Detroit” (id.

at 154a) by not providing transportation funds to Detroit on the

same basis as funds were provided to suburban districts (id. at

151a) ; and (5) that the transportation of black students from one

suburban district to a black school in Detroit must have had the

“ approval, tacit or express, o f the State Board of Education” (id.

at 152a).

9

the acts of racial discrimination shown in the record

are “ causal! v related to the substantial amount of

segregation found in the Detroit school system” (id.

at 157a), and that “ the District Court was therefore

authorized and required to take effective measures to

desegregate the Detroit Public School System” (id.

at 158a).

The court of appeals also agreed with the district

court that “ any less comprehensive a solution than

a metropolitan area plan would result in an all black

school system immediately surrounded by practically

all white suburban school systems, with an over

whelmingly white majority population in the total

metropolitan area” (id. at 163a-164a). It stated that it

could “not see how such segregation can be any less

harmful to the minority students than if the same re

sult were accomplished within one school district”

(id. at 164a).

The court of appeals accordingly concluded that

“ the only feasible desegregation plan involves the

crossing of the boundary lines between the Detroit

School District and adjacent or nearby school dis

tricts for the limited purpose of providing an effective

desegregation plan” (id. at 172a). It reasoned that

such a plan would be appropriate because of the

State’s violations, and could be implemented because

of the State’s authority to control local school dis

tricts. “ [T]he State has committed de jure acts of

segregation and * * * the State controls the instru

mentalities whose action is necessary to remedy the

harmful effects of the State acts” (ibid.). An inter-

10

district remedy is thus “within the equity powers of

the District Court” {id. at 173a).9

The court of appeals expressed no views on the pro

priety of the district court’s “desegregation area.” It

held that all suburban school districts that might be

affected by any metropolitan-wide remedy should be

made parties to the case on remand and be given an

opportunity to be heard with respect to the scope and

implementation of such a remedy {id. at 177a). Under

the terms of the remand, however, the district court

need not receive further evidence on the issue of segre

gation in the Detroit schools or on the propriety of a

Detroit-only remedy {id. at 178a).

It is our view that the remedy for unconstitutional

segregation of the public schools in a school district

can properly extend beyond the boundaries of the dis

trict only where the violation has directly altered or

substantially affected the racial composition of schools

outside the district and only to the extent necessary to

eliminate the segregative effects of the violation.

Where the schools of only one district have been af

fected, there is no constitutional requirement that the

relief include a balancing of the racial composition of

that district’s schools with those of surrounding

districts.

The record does not support the ruling of the court

9 The court sought to distinguish Bradley v. School Board of

the City of Richmond, Virginia, 462 F. 2d 1058 (C.A. 4), affirmed

by an equally divided Court, 412 U S . 92, on the grounds that the

district court in that case had ordered an actual consolidation of

three school districts and that Virginia’s constitution and statutes,

unlike Michigan’s gave the local boards exclusive power to operate

the public schools (Pet. App. 175a).

11

of appeals that a metropolitan-wide remedy is appro

priate to cure the violations found in this case, vir

tually all of which affected only the schools in the De

troit system. The case should be remanded to permit

all the parties, many of whom have not yet been heard

in the district court, to present evidence and argument

on the existence of any constitutional violations that

have directly altered or substantially affected the racial

composition of schools outside Detroit, and on the ap

propriate remedy for any such violation.

II

THE REMEDY FOR UNCONSTITUTIONAL SCHOOL SEGREGA

TION MAY EXTEND BEYOND THE BOUNDARIES OF A

SINGLE DISTRICT ONLY IF, AND TO THE EXTENT THAT,

THE VIOLATION HAS DIRECTLY ALTERED OR SUBSTAN

TIALLY AFFECTED THE RACIAL COMPOSITION OF SCHOOLS

IN MORE THAN ONE DISTRICT

This Court held in Swann v. Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, Id, that the task in fashioning school de

segregation relief “ is to correct * * * the condition

that offends the Constitution.” It follows that “ the

nature of the violation determines the scope of the

remedy” (ibicl.).

The mere co-existence, within a State, of adjacent

school districts having disparate racial compositions

is not itself a constitutional violation. Spencer v.

Kugler, 404 U.S. 1027, affirming 326 F. Supp. 1235

(D. N.J.).10 As Solicitor General Griswold explained

10 In Spencer this Court affirmed the district court’s decision

that, at least in States not recently operating dual school sys

tems, extreme racial imbalance, without more, does not author

ize—let alone require—the court to revise neutrally established

school district lines.

12

last Term in the Memorandum for the United States

as Amicus Curiae in School Board of the City of Rich

mond, Virginia v. State Board of Education (No. 72-

549), supra, at pp. 13-15 (footnote omitted) :

In determining that one school system for the

entire region should be created, the district

court relied upon (Pet. App. 187a) this Court’s

statement in Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 26, that

for remedial purposes, there is “a presumption

against schools that are substantially dispropor

tionate in their racial composition.” But dis

proportionate in relation to what? Surely not

to some absolute standard, for the Constitution

does not establish any fixed ratio of black stu

dents to white students that must be achieved.

Instead, whether a particular school is racially

imbalanced or identifiable can be determined

only by comparing it with “ the racial composi

tion of the whole school system.” Swann v.

Board of Education, supra, 402 U.S. at 25; see

also id. at 24.

Thus, the question whether, for example, an

elementary school having a student body 70 per

cent black and 30 percent white is racially im

balanced or has a substantially disproportion

ate racial composition is in itself unanswerable.

Some frame of reference is needed and, as

Swann indicates, the proper comparison (to the

extent that racial balance is relevant) is with

the racial composition of the population in the

school system operating the particular school

since the purpose is to ensure complete elimina

tion of the dual system by having one set of

schools for both blacks and whites. And under

Swann there would be no presumption against

schools, such as the one in the example above, if

13

these schools reflected the black-white ratio of

the entire school system. 402 II. S. at 25-26.

Why then would there be a presumption

against the school system itself with the same

70:30 ratio of blacks to whites, as the district

court concluded here with respect to the school

system of the City of Richmond? (Pet. App.

186a-188a.) Stated differently, on what basis

could the district court conclude that its remedy

should reach outside the school system of the

City of Richmond? Apparently, the court be

lieved that it must look beyond the Richmond

system in fashioning relief because the City

school system is racially disproportionate or

imbalanced in relation to the adjacent County

school systems, thereby resulting in racial iclen-

tifiability of the three systems (e.g., Pet. App.

185a-187a, 230a, 237a-238a). But the court had

to look beyond the Richmond system and com

pare it with the surrounding Counties in the

first place in order to determine whether the

Richmond system is racially imbalanced in com

parison with the adjacent systems. This is not

only circular as a reason for fashioning relief

beyond the Richmond system, but also heedless

of the extent of the constitutional violation be

ing remedied.

Thus, in our view, an interdistrict remedy, requiring

he restructuring of state or local government entities,

is appropriate only in the unusual circumstance where

it is necessary to undo the interdistrict effect of a con

stitutional violation. Specifically, if it were shown that

the racially discriminatory acts of the State, or of sev

eral local school districts, or of a single local district,

have been a direct or substantial cause of interdistrict

14

school segregation, then a remedy designed to eliminate

the segregation so caused would be appropriate.

One example of circumstances warranting interdis

trict relief is where one or more school systems have

been created and maintained for members of one race.

See, e.g., United States v. Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043

(E.D. Texas), affirmed, 447 F. 2d 441 (C.A. 5), cer

tiorari denied sub nom. Edgar v. United States, 404

U.S. 1016; Haney v. County Board of Education of

Sevier County, 429 F. 2d 364 (C.A. 8). Similarly,

where the boundaries separating districts have been

drawn on account of race, an interdistrict remedy is

appropriate. See, e.g., United States v. Missouri, 363

F. Supp. 739 (E.D. Mo.).11 Some form of interdistrict

relief may also be appropriate where pupils have been

transferred across district lines on a racially discrim

inatory basis.

In each instance of an interdistrict violation, the

remedy should, in accordance with traditional prin

ciples of equity and the law of remedies, be tailored to fit

the violation, particularly in view of the deference

owed to existing governmental structures. See, e.g.,

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, Vir

ginia, supra, 462 F. 2d at 1067-1069; cf. Wright v. Coun

cil of City of Emporia, supra, 407 U.S. at 478 (Burger,

C.J., dissenting). Any modification of those structures

11 Cf. Wright v. Council o f City o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451;

United States v. Scotland Neck Board of Education, 407 U.S.

484. In those cases, this Court held that an “ attempt by state

or local officials to carve out a new school district from an ex

isting district that is in the process of dismantling a dual

school system” may be enjoined by the district court if it

would impede the dismantling o f the dual system (id. at 489).

15

should be narrowly framed to eliminate the interdistrict

segregation that has been caused by the particular viola

tion, so as to avoid unnecessary judicial interference

with state prerogatives concerning the organization of

local governments. Thus, a single instance of dis

criminatory cross-district transfers between only two

school districts (see pp. 19-20, infra) would not warrant

the kind of metropolitan-wide interdistrict remedy in

volving 54 districts that the courts below contemplate

here. The appropriate relief should be limited to cor

recting the segregative conditions caused by the trans

fers.12

I l l

THE RECORD IN THIS CASE DOES NOT SUPPORT THE BROAD

METROPOLITAN-WIDE REMEDY CONTEMPLATED BY THE

COURT OF APPEALS

This Court does not have before it a final order

adopting a particular plan of desegregation. It is re

viewing, instead, a general determination that the seg

regation of the Detroit public schools shown on this

record warrants an interdistrict remedy potentially

embracing much or all of the 86-district metropolitan

12 Moreover, even a finding o f some interdistrict violations

would not mean that extensive interdistrict bussing should be

required as a remedy regardless of its disruptive effects or other

costs. This Court specifically stated in Swann that “ [a]n objec

tion to transportation o f students may have validity when the

time or distance o f travel is so great as to either risk the health

of the children or significantly impinge on the educational pro

cess” (402 TT.S. at 30-31), and it indicated that in remedying

school segregation the courts should engage in the process of

informed “ reconciliation of competing values” that “ courts of

equity have traditionally employed” (402 U.S. at 31).

16

area. In our view, the record does not support such a

remedy, because it does not show that the constitu

tional violations have directly altered or substantially

affected the racial composition of schools in districts out

side of Detroit.

Neither the district court nor the court of appeals

predicated its conclusion concerning the propriety of

a metropolitan-wide remedy on the existence of any

violation caused by or affecting more than one district.

There is, first of all, no finding that any school district

other than Detroit has engaged in racial discrimina

tion: the district court specified that it had taken no

evidence on whether the suburban districts “have com

mitted acts of de jure segregation7’ (Pet. App. 60a).

Nor is there any proof that state or local officials

gerrymandered district lines for purposes of racial

discrimination. On this point, too, the district court

took no evidence (ibid.).

The district court found—and the court of appeals

upheld the findings—that the Detroit school board

had committed unlawful acts of discrimination caus

ing substantial racial segregation in the Detroit

schools and that the state defendants had also com

mitted violations contributing to the segregation in

those schools (id. at 118a-157a; see id. at 24a-28a, 33a-

38a). But the record thus far does not establish any

basis for concluding that the state or city violations

have directly altered or substantially affected the racial

composition of schools outside Detroit.

The district court, in its September 27, 1971, rul

ing on the issue of segregation, considered “ the pres

ent racial complexion of the City of Detroit and its

17

public school system’ 7 in light of “ what has happened

in the last half century” in the Detroit metropolitan

area (Pet. App. 19a). In the course of that general

historical review, the court stated (id. at 23a) : “ Gov

ernmental actions and inaction at all levels, federal,

state, and local, have combined, with those of private

organizations, such as loaning institutions and real

estate associations and brokerage firms, to establish

and to maintain the pattern of residential segrega

tion throughout the Detroit metropolitan area.” While

the court also noted that “ there is an interaction be

tween residential patterns and racial composition of

the schools” (id. at 24a), its findings of constitutiona]

violations and racial segregation in the schools were

limited to “ the Detroit school system” (ibid.).13 It

did not find that any suburban school segregation was

caused by any state or local acts of de jure racial

discrimination.

Similarly, the court of appeals concluded that the

discriminatory practices of the state and city defend

ants are “ causally related to the substantial amount

of segregation found in the Detroit school system”

(id. at 157a; emphasis added) and that the district

court was required “ to desegregate the Detroit Public

School System” (id. at 158a; emphasis added).14 The 13 14

13 The district court’s conclusions were that u[t]he public

schools operated by defendant Board are * * * segregated on

a racial basis” (Pet. App. 26a; emphasis added) and that the

State and the Detroit board “have committed acts which have

been causal factors in the segregated condition of the public

schools of the City of Detroit” (id. at 33a; emphasis added).

14 The decision of the court of appeals dealt at some length

with the question of violations within the city o f Detroit (see

Pet. App. 118a-151a). Although one of the petitioners appears

18

court of appeals also stated, however, that “ the State

has been guilty of discrimination which had the effect

of creating and maintaining racial segregation along

school district lines” (id. at 172a). That statement ap

pears in the section of the court’s opinion relating to

the propriety of an interdistrict remedy in circum

stances where a Detroit-only remedy would lead to an

overwhelmingly black city school system. The state

ment is followed by a reference to an earlier section

of the opinion concerning the violations committed by

the State (id. at 151a-157a). The earlier section itself,

however, cites only one instance of a possible inter

district violation.

As we indicated above (p. 8, n. 8, supra), the

court of appeals found that the State committed five

constitutional violations. With respect to four of those

violations, there is nothing to indicate that any of them

affected the racial character of schools outside the

Detroit system. First, the court held that the State

was derivatively responsible for the Detroit board’s

violations (Pet. App. 151a), but, so far as this record

shows, those violations themselves affected only the

schools within the Detroit district. Second, the State’s

legislative interference with Detroit’s voluntary de

segregation plan contributed, in the court’s words,

only to “ segregation of the Detroit school system”

now to challenge the affirmance by the court of appeals o f the

findings concerning intra-Detroit violations (see Brief for Pe

titioner in 73-436, pp. 15-18), the correctness o f that aspect of

the decision was not questioned in any of the petitions. In any

event, this aspect of the decisions below appears consistent with

this Court’s decision last Term in Keyes v. School District No.

1, Denver, Colorado, 413 U.S*

19

{ibid.). Third, the court held that the State’s author

ity to supervise school site selection and to approve

building construction plans means that the State is

responsible for “ the segregative results” of “ Detroit’s

school construction program” {ibid.) ; again, there is

no basis for concluding that Detroit’s construction

program affected suburban districts.15 Fourth, there

is no indication in the record or in the opinions below

how, if at all, the availability of state-financed trans

portation for some Michigan students outside Detroit

but not within Detroit {ibid.) might have affected the

racial character of any of the State’s school districts.

The fifth violation that the court of appeals attrib

uted to the State is the only one that can be said, on

the present record, to have had some interdistrict ra

cial impact. In one instance, the suburban Carver

school district arranged by contract to have its black

high school students educated in a predominantly

black Detroit high school, because “ no white sub

urban district (or white school in the city) would

take the children” (Pet. App. 137a). The court of

appeals stated that this cross-district transportation

“ could not have taken place without the approval,

tacit or express, of the State Board of Education”

{id. at 152a). Of course, such an arrangement be

tween the Carver and Detroit school boards was state

15 The court of appeals asserted that, “ as was pointed out

above, the State approved school construction which fostered

segregation throughout the Detroit metropolitan area” (Pet.

App. 157a). But its only reference is to an earlier section of

the opinion that relates to the segregative impact in Detroit o f

the school construction program in that district ( id. at 144a-

151a).

20

action which may have amounted to unconstitutional

racial segregation,16 regardless of whether the State

Board participated in it. But the appropriate remedy

would he one tailored to fit that possible violation—

also regardless of State Board participation—since

such participation would not change the nature or

consequences of the violation. An isolated instance of

cross-district transfers on account of race between

only two school districts (and possibly involving re

fusals for racial reasons by schools in one or a small

number of other districts to accept the transferred stu

dents) cannot, as a matter of equity, support a metro

politan-wide interdistrict remedy involving 54 or more

school systems.

Indeed, neither the district court nor the court of

appeals predicated its holding on the existence of a

violation affecting the racial composition of the sub

urban districts. The district court determined that a

metropolitan-wide remedy would be appropriate to

desegregate the Detroit schools, because it concluded

that any effective plan limited to Detroit “ would ac

centuate the racial identifiability of the district as a

Black school system, and would not accomplish deseg

regation’ ’ (Pet. App. 56a). The court of appeals

reached the same conclusion: “ [A]ny Detroit only

desegregation plan will lead directly to a single seg

regated Detroit school district overwhelmingly black

in all of its schools” (id. at 172a-173a). Such a rem

edy “ cannot correct the constitutional violations here

in found” (id. at 173a).

The prediction that massive “ white flight” will re

sult from an effective intra-Detroit desegregation

1G See Pet. App. 96a, 137a-139a; I I App. 109-111, 131.

21

plan is inherently speculative, and in any event does

not change the nature of the violation to he remedied.

For that reason, such a prediction does not in itself

warrant interdistrict relief. On this aspect of the case,

also, we adhere to the following views stated last

Term by Solicitor General Griswold in response to

a similar prediction by the district court in the Rich

mond case (Memorandum for the United States as

Amicus Curiae, supra, pp. 17-20; footnotes omitted or

renumbered) :

The district court also believed that the school

system of the City of Richmond could not be

come a unitary system within its boundaries

because a “ viable racial mix” would not be pos

sible in light of the racial composition of Rich

mond’s population (Pet. App. 207a, 420a, 519a;

see, e.g.y id. at 201a, 230a, 237a-238a, 436a-442a,

444a). The court pointed to evidence that the

current proportion of blacks to whites in the

Richmond school system has resulted in whites

leaving Richmond’s public schools and that un

less the trend were reversed, the City’s schools

might become all black.

The duty of the district court in this case

was to ensure that the Richmond school system

converted to a unitary system. And as we have

discussed, see pp. 11-17, supra, as long as the

school authorities operate just schools instead

of one set of schools for blacks and another for

whites, it matters not at all whether the system

has more black students than white students or

vice-versa. The schools of Vermont are not seg

regated even though most of them are all white.

Under the district court’s theory and its con

solidation order, which would reverse the racial

22

composition of the Richmond schools from ma

jority black to majority white, the apparent

goal is to have a school system with substan

tially more white children than black children.

But the Fourteenth Amendment does not prefer

predominantly white school systems over pre

dominantly black school systems and it does not

sanction the district court’s transforming its

preference in this regard into a constitutional

command.

We of course agree that the federal courts

have wide discretion to bring about unitary

school systems. But as Chief Justice Marshall

stated long ago, to say that the matter is within

a court’s discretion means that it is addressed

not to the court’s “ inclination, but to its judg

ment ; and its judgment is to be guided by sound

legal principles.” 17 The purpose of a court-

ordered remedy in these cases is to cure the vio

lation, to correct “ the condition that offends the

Constitution.” Swann v. Board of Education,

supra, 402 U.S. at 16. Yet here the district court,

instead of ordering relief within the bounds of

Richmond’s constitutional violation, went far

beyond in the hope of forestalling the result of

a possible migration of whites from the City, a

result not in itself unconstitutional but thought

by the district court to be undesirable.

I f a certain desegregation plan would become

ineffective shortly after implementation this is

certainly something the district court should

consider. Surely it would have been proper in

this case for the district court to seek a remedy

within the Richmond system that promised

17 United States v. Burr, 25 Fed. Cas. 30, 35 (No.

14,692d, 1807).

23

maximum stability. But the desire to preserve

the existing racial character of the City of Rich

mond or of its school system is not of constitu

tional dimensions and does not warrant includ

ing within the scope of relief other school

systems that are uninvolved in Richmond’s vio

lation. Petitioners may prefer a consolidated

school system with a large, stable white enroll

ment ; the Constitution does not.

Indeed, even in the context of relief within a single

district, this Court clearly indicated in Swann (402

U.S. at 31-32) that the proper remedy in school de

segregation cases does not include pursuit of demo

graphic changes. When the violations found have been

cured, “ [t]he [school] systems would then be ‘unitary’

* * (402 U.S. at 31), and “ in the absence of a

showing that either the school authorities or some

other agency of the State has deliberately attempted

to fix or alter demographic patterns to affect the

racial composition of the schools, further intervention

by a district court should not be necessary” (402 U.S.

at 32). Obviously, there is even less reason to extend

the remedy across district lines on the basis of demo

graphic differences (in the absence of interdistrict

violation).

Nor, in our view, do the district court’s general re

marks about housing discrimination {supra, p. 17),

on which its present decision apparently was not

based, provide a proper foundation for the interdistrict

relief contemplated by the courts below. Indeed, more

specific evidence and findings of housing and other

collateral discrimination were relied upon last Term

in the Richmond case, and we adhere, on this point

24

as well, to the views stated in the Memorandum for

the United States as Amicus Curiae in that case (pp.

23-26; footnotes renumbered).

Petitioners rely primarily on evidence of

housing discrimination and of various kinds of

either intrasystem or state-wide racial dis

crimination to overcome this presumption.18 The

housing pattern in the Richmond metropolitan

area is similar to that found in most metro

politan areas of this country. The inner city

has a large black population and the surround

ing suburbs are primarily white. While the

causes of this housing pattern are manifold, the

court of appeals accepted the contention “ that

within the City of Richmond there has been

state (also federal) action tending to perpetu

ate apartheid of the races in ghetto patterns

throughout the city, and that there has been

state action within the adjoining counties also

tending to restrict and control the housing

location of black residents” (Pet. App. 572a).

Other acts cited as establishing an inter-sys

tem violation are Virginia’s ‘ *massive resist

ance” campaign against school desegregation

(Pet. App. 313), various types of delaying ac

tions undertaken to resist desegregation of the

Richmond schools (Pet. App. 189a), actions by

state officials tending to reinforce racism (Pet.

App. 189a), construction of racially identifiable

schools after Brown I (Pet. App. 287a), dis

crimination in public employment in Henrico

and Chesterfield Counties (Pet. App. 510a),

18 They also mention past instances of transportation of

black students across school division lines in the State in

order to perpetuate state-enforced segregation o f schools

(Pet. App. 360a; cf. id. at 388a). * * *

25

lack of public transportation for poor persons

(Pet. App. 514a), past state restrictions on in

ter-racial contacts of various kinds,19 and state

approval of school construction sites without

regard to the impact on school desegregation

(Pet. App. 206a).

Such acts are a shameful part of our history,

and the Nation has in recent years enacted

laws to remedy many of them. See, e.g., 42

U.S.C. 1973 (voting), 2000e (employment), and

3601-3619 (housing). See also the Virginia

Fair Housing Law, enacted in 1972, Code of

Virginia, Title 36, Chapter 5. But even if some

or all of these acts, including participation in

residential housing discrimination, have con

tributed in some degree to the present racial

composition of the public schools in the

three school systems within the metropolitan

Richmond area, the question remains whether

there is a sufficiently proximate and substan

tially causal relationship to the racial disparity

between school systems to warrant a conclu

sion that state-enforced racial discrimination

in the public schools has resulted.20

Racial discrimination in such areas as hous

ing, employment, and public expenditures are

19 See, e.g., Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454; Loving

v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1; N AAGP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415.

20 The past existence of state-imposed discrimination,

including school segregation, might, for example, also have

contributed in some degree to decisions by individuals to

discriminate in their social relationships, but this does not

in itself necessarily convert what would otherwise be pri

vate discrimination into state action. Compare Moose

Lodge No. 107 v. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163, and Evans v. Abney.

396 U.S. 435, with Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267,

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153, and Burton v. Wilming

ton Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715.

26

serious problems that must be attacked directly

so that they can be eliminated from our society.

But as this Court said in Swann, supra, 402

U.S. at 22-23:

The elimination of racial discrimination

in public schools is a large task and one

that should not be retarded by efforts to

achieve broader purposes lying beyond

the jurisdiction of school authorities. One

vehicle can carry only a limited amount

of baggage. It would not serve the impor

tant objective of Brown I to seek to use

school desegregation cases for purposes

beyond their scope although desegrega

tion of schools ultimately will have im

pact on other forms of discrimination.

We therefore conclude that the record in the present

case does not warrant the fashioning of a metro

politan-wide remedy. We recognize, however, that, for

practical purposes, the record was made at a time

when only an intra-Detroit remedy was sought (see

Pet. App. 13a-15a) and when many of the suburban

school districts were not parties. We submit that the

appropriate disposition in these circumstances is to

remand the case to the district court with instructions

to join as parties all the school districts in the three-

county metropolitan area. The district court should

take evidence and make findings of fact concerning

any constitutional violations involving the suburban

districts and any interdistrict racially segregatory im

pact of the Detroit violations. I f no such violation or

impact is shown, relief should be limited to Detroit. I f

any such violation or impact is shown, the district

court should, after considering the evidence and argu-

27

ment of all affected school districts, fashion appropri

ate relief to remedy the particular violations found.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the court

of appeals should be vacated and the case should be

remanded for further proceedings in accordance with

the principles stated herein.

Respectfully submitted.

R obert H . B ork,

Solicitor General.

J. Stanley P ottinger,

Assistant Attorney General.

F ebruary 1974.

U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE:1974

■ : - r

: ®|SSfe

'' t' ,‘l" , ■" :

* y ' r

' ' F 1 '

\ : r! ,'\ s

- ■ C,.V ;f'fec ,

■

1 0 S '

8 S IS " ;-

\vk - p 5?

s

.

M . - 1/ - : ; -

- \

, .;. , ' 1 '' , - • . ‘

• ■ . ’ V ■■■''’

. ■ r -