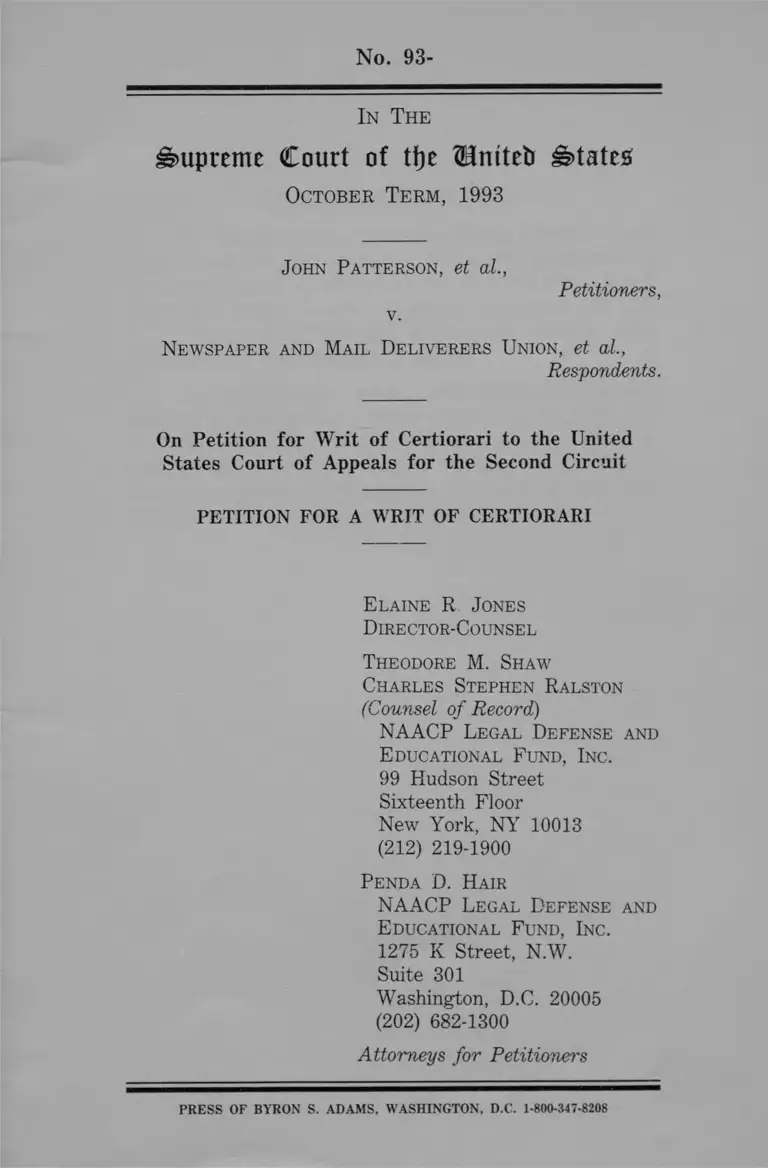

Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers Union Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1993

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers Union Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1993. 746757e3-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b25c654-0239-45f9-8588-84f8da705f2a/patterson-v-newspaper-and-mail-deliverers-union-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

No. 93-

In T h e

Supreme Court of tf)e HrutEtr H>tate£

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1993

John P atterso n , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

N ew spa pe r and Mail D e l iv e r e r s U nio n , et al,

Respondents.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

E laine R Jones

D irector-Co unsel

Theodore M. S haw

Ch a r les St e ph e n Ralston

(Counsel of Record)

NAACP L egal D e f e n se and

E ducational F u n d , Inc .

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

P e n d a D. H air

N A A C P L egal D e f e n se and

E ducational F u n d , Inc .

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Petitioners

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. 1-800-347-8208

1

Q u e s t io n s P r e s e n t e d

1. Does the standard for terminating consent decrees

in cases involving governmental defendants enunciated in

Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell, 498 U.S. 237

(1991) and Rufo v. Inmates of Suffolk County Jail, 502 U.S.

116 L.Ed.2d 867 (1992) also govern in cases involving

private, non-governmental defendants?

2. Did the lower courts err in granting defendants’

motions to dissolve the consent decree in this Title VII

action when the defendants failed to demonstrate compliance

with the decree and in the face of evidence and findings by

the court-appointed Administrator and the trial court that

defendants were continuing to violate the decree?

P a r t ie s

The participants in the proceedings below were:

John R. Patterson, Roland J. Broussard, Elmer

Stevenson, and the class they represent,

Plaintiffs.

11

The United States Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission,

Plaintiff.

Newspaper & Mail Deliverers Union of New York &

Vicinity; New York Times Company; Maxwell Newspapers,

Inc. (New York Daily News, Inc.); New York Post; Dow

Jones Co., Inc.; Evening Journal Association; Hudson News

Company; Metropolitan News Company; Passaic County

News Company; Rockland News Agency; Raritan Periodical

Sales; Bay City News Company; Brodsky News Co.; Crescent

News Distributors Incorporated; Flushing News Company;

Gaynor News Co.; Jersey Coast News Co.; Long Island News

Corp.; Newark Newsdealers Supply Company; New

Brunswick Newsdealers Co.; S. Rachles Newsdealers;

Standard News Co.; Union County Newsdealer Supply Co.;

Boro Park News Co.; Merit News Co., Inc.; Tribune New

York Holdings, Inc.; Westfair Newspaper Distributors;

NDI/Newspaper Distributors; Amsterdam News Company;

El-Diaro-La Prensa; Fairchild Publications; Magazine

Distributors, Inc’s and MDI Distributors, Ltd.; A Co.; Bronx

County News Company; Bronxville News Company; Brooklyn

Daily Inc.; Brooklyn News Company; Brownsville News Co.;

East Island News Company; Eluyn News Co.; F. Printico;

G.I. Distributors, Inc.; Weinberg News Co.; Imperial News

Co.; Long Island Press Publishing Co.; Long View Publishing

Co.; Manhattan News Co., Inc.; Mill Basin News Co.; New

York News Incorporated; Newark Morning Ledger, Co.;

Ridgewood News Company; T Co.,

Defendants.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Pr e s e n t e d ................................................... i

Pa r t i e s ................................................................................................ ii

Opinions Be l o w .............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 2

Statutes In v o l v e d ........................................................ 2

St a t e m e n t o f t h e Ca s e ..........................................

A. The Proceedings Below........................

B. Statement of the Facts.........................

1. Histoiy of Discrimination in

the Industry..................................... 7

2. The Consent Decree...................... 9

3. Compliance with the

Affirmative Action Provisions. . 13

4. The Role of the

Administrator............................... 14

5. The Motions to Dissolve the

Consent Decree............................ 14

6. Plaintiffs’ Response — The

History of Non-compliance. . . . 15

7. The Decision of the District

Court............................................. 18

Reasons for Granting the Wr i t .......................... 20

In tr o d u c tio n ................................................... 20

I. The Case Presents an Important

Question Regarding the

Standard That Should Govern

the D issolution of Consent

Decrees About Which There Is

Conflict Between the Circuits. . . 2 1

v

j

Q

l

IV

II. The Decisions of the Courts

Below Conflict With Decisions

of This Court That Require

That a Defendant Demonstrate

Compliance With a Consent

Decree Before The Decree Can

Be D issolved.............................. 22

III. The Decision of the Court

Below Will Undermine the

Settlement of Cases in Federal

Court........................... 24

C o n c l u s i o n ........................... 27

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell,

498 U.S. 237 (1991) passim

Epp v. Kerrey,

964 F.2d 754 (8th Cir. 1992) ............................ 19

Evans v. Jeff D.,

475 U.S. 717 (1986) 22

Freeman v. Pitts,

503 U .S .__ , 118 L. Ed. 2d 108 (1992) . 18, 21, 22

In re Hendrix,

986 F.2d 195 (7th Cir. 1993) .............................. 19

Lorain NAACP v. Lorain Bd. of Educ.,

979 F.2d 1141 (6th Cir. 1992) .......................... 19

Marek v, Chesny,

473 U.S. 1 (1985) .............................................. 22

Patterson v. NMDU,

384 F. Supp. 585 (S.D.N.Y. 1974).................... 2, 4

Patterson v. NMDU,

514 F.2d 767 (2nd Cir. 1975)............................ 2, 5

Rufo v. Inmates of Suffolk County Jail,

502 U .S.__ ,

116 L. Ed. 2d 867 (1992)..................... 1, 5, 18, 21

United States v. Swift & Co.,

286 U.S. 106 (1932) ................ .. 18, 19, 20, 22

VI

Pages:

United States v. Western Electric, Co., Inc.,

969 F.2d 1231 (D.C. Cir. 1992) .......................... 19

United States v. Western Electric Co., Inc.,

_ F. Supp.___, 1994 WL 143082 (D.D.C. April

5, 1994).................... 19

W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc. v. C.R. Bard, Inc.,

977 F.2d 558 (Fed. Cir. 1992) . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Statutes: Pages:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) .............................................. ........... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1981 .......................... ............................. .. 3, 4

42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq........................... 4

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)........................................ 2

No. 93-

In T h e

Supreme Court of tf)t ®niteb Jkates

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1993

Jo h n Pa t t e r s o n , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

N e w sp a p e r a n d M a il D e l iv e r e r s U n io n , et al.,

Respondents.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Petitioners John R. Patterson, Roland J. Broussard,

and Elmer Stevenson, on their own behalf and on behalf of

all other persons similarly situated, respectfully pray that a

writ of certiorari issue to review the opinion of the Court of

Appeals for the Second Circuit entered in this proceeding

December 20, 1993.

O p in io n s B e l o w

The opinion of the Second Circuit is reported at 13

F.3d 33 (2d Cir. 1993) and is set out at pages la-12a of the

Appendix hereto ("App."). The order of the Court of

Appeals denying a timely petition for rehearing and

2

suggestion for rehearing en banc is unreported and is set out

at App. at 13a-14a. The decision of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of New York that

was affirmed by the Court of Appeals is reported at 797 F.

Supp. 1174 (S.D.N.Y. 1992) and is set out at 100a-121a.

Other decisions of the district court and of the Court of

Appeals that are relevant to the issues presented by this

petition and that are referred to herein, are set out in the

Appendix as follows: 384 F. Supp. 585 (S.D.N.Y. 1974), 15a-

32a; unreported Final Order and Judgment, 33a-35a; 514

F.2d 1767 (2nd Cir. 1975), 36a-54a; 23 E.P.D. 11 31,001

(S.D.N.Y. 1980), 55a-62a; 42 E.P.D. U 36,722 (S.D.N.Y.

1986), 63a-67a; 46 E.P.D. U 36,722 (S.D.N.Y. 1988), 68a-74a;

772 F. Supp. 1439 (S.D.N.Y. 1991), 75a-92a; 777 F. Supp.

1190 (S.D.N.Y. 1991), 93a-99a; 802 F. Supp. 1053 (S.D.N.Y.

1992), 122a-133a.

Ju r is d ic t io n

The decision of the Second Circuit was entered on

December 20, 1993. A timely petition for rehearing was

filed and was denied on February 7, 1994. Jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

St a t u t e s In v o l v e d

This case involves Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a), which provides in

pertinent part as follows:

(a) It shall be an unlawful employment

practice for an employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any

individual with respect to his compensation, terms,

conditions of employment, because of such

3

individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin;

* * *

(c) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for

a labor organization—

(1) to exclude or to expel from its membership, or

otherwise to discriminate against, any individual

because of his race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin;

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify its membership or

applicants for membership or to classify or fail or

refuse to refer for employment any individual, in any

way which would deprive or tend to deprive any

individual of employment opportunities, or would

limit such employment opportunities or otherwise

adversely affect his status as an employee or as an

applicant for employment, because of such

individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin; or

(3) to cause or attempt to cause an employer to

discriminate against an individual in violation of this

section.

This case also involves 42 U.S.C. § 1981, which

provides in pertinent part as follows:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts . . . as is

enjoyed by white citizens . . . .

4

St a t e m e n t o f t h e C a s e

A. The Proceedings Below.

This action is based on Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq., and 42

U.S.C. § 1981. It was filed by African American employees

of various newspapers on their own behalf and on behalf of

a class on July 11, 1973. The complaint alleged that the

defendant Newspaper and Mail Drivers’ Union (N.M.D.U.)

and a number of New York area newspapers and newspaper

distributors, including the New York Times and the Daily

News1, had engaged in a variety of practices that had the

purpose and effect of discriminating against African

American drivers. (J.A. 1-14.)2 Subsequently, an action

making similar allegations was filed by the United States

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (J.A. 30-38.)

The two cases were consolidated for all purposes and a four

week trial on the merits was held in 1974 before then

District Court Judge Lawrence W. Pierce.

After the trial had concluded, the parties entered into

a settlement agreement that was approved by Judge Pierce,

who made findings of fact and entered a consent decree that

embodied the injunction at issue here. Patterson v. NMDU,

384 F. Supp. 585 (S.D.N.Y. 1974). (App. 15a-35a.) A white

worker objected to the decree and filed an appeal to the

‘Although the consent decree was signed by virtually all of the

newspaper publishers and distributors in the New York Metropolitan

Area for whom the N.M.D.U. is the bargaining agent, only N.M.D.U.

the New York Times, the New York Daily News, and the New York

Post were actively involved in the proceedings that led to the

dissolution of the consent decree that is at issue here. Only the

Times and the News actually participated in the appeal in the Second

Circuit.

2Record citations are to the Joint Appendix filed below ("J.A.")

or to the original record.

5

Second Circuit. The court affirmed the entry of the decree

on March 20, 1975 and the case was returned to the district

court. Patterson v. NMDU, 514 F.2d 767 (2nd Cir. 1975).

(App. 36a-54a.)

On November 9, 1979, a number of the defendants

moved to modify the decree by eliminating the role of the

Interim Administrator. Judge Pierce denied the motion on

a number of grounds, including a finding that the goals and

timetables provisions had not been met, and that there

continued to be claims that the decree was being violated in

a number of respects. (App. 55a-62a.) In 1985, the Times

and other defendants filed a second motion. Since Judge

Pierce had been elevated to the court of appeals, the case

had been assigned to Judge Conner in 1982. Both the

private plaintiffs and the EEOC opposed the motion and

various proceedings took place, which will be described in

more detail below. Finally, on July 29, 1992, Judge Conner

issued an order vacating the injunction in its entirety,

although jurisdiction was retained to resolve certain

outstanding claims by class members. Judge Conner also

denied a motion to alter and amend the judgment and a

motion by private plaintiffs to restore the injunction pending

appeal. (App. 100a-121a; 122a-133a.)

Both the private plaintiffs and the EEOC appealed.

The Second Circuit affirmed, holding that the standard

enunciated by this Court in Board of Education of Oklahoma

City v. Dowell, 498 U.S. 237 (1991) and Rufo v. Inmates of

Suffolk County Jail, 502 U.S.__ , 116 L.Ed.2d 867 (1992) for

vacating or modifying consent decrees when the defendant

was a local governmental agency should be applied in all

cases. The court acknowledged a division between the

circuits on this issue. (App. 9a.) The Court of Appeals did

not mention or discuss the issue of the defendants’ failure to

demonstrate that they had complied with all aspects of the

decree over a reasonable period of time, or the evidence

introduced by the petitioners that, in fact, various of the

defendants had violated the decree. Petitioners filed a

6

petition for rehearing and a suggestion for rehearing en banc.

The petition for rehearing was based on the failure to deal

with the issue of violations of the consent decree; the

suggestion for rehearing en banc was based on whether Rufo

should apply where the defendant was not a governmental

agency. The petition for rehearing was denied without

opinion on February 7, 1994.

B. Statement o f the Facts.

1. History of Discrimination in the Industry.

Although this case was settled by the parties, Judge

Pierce had before him the record of a four-week trial on the

merits of the claims of racial discrimination in the industry.

Thus, when he approved the decree he made detailed

findings of fact. The focus of the claims were jobs at all of

the newspapers and other publishers who employed members

of the Newspaper and Mail Drivers Union to deliver

newspapers and other periodicals in the metropolitan area of

New York City and outlying areas.

Judge Pierce described the way the industry

functioned:

The nature of the delivery industry is such

that the employers’ needs for delivery department

employees vary from day to day, and indeed, shift to

shift, depending upon the size and quantity of the

publication(s) being distributed. Thus, each employer

. . . maintains a regular work force (Regular Situation

holders) for its minimum needs, and depends upon

daily shapers to supplement the force. . . . [A]t the

major employers the shapers are categorized into

groups with descending daily hiring priorities. Group

I is restricted . . . to persons who have at one time

held a Regular Situation in the industry. They have

first shaping priority at every shift, in order of their

7

shop seniority. After the Group I is exhausted . . .

the next hiring priority shall go to Group II members

[consisting] of all persons in Group I and all persons

holding Regular Situations in the industiy.. . . [T]he

remaining open jobs, if any, will go to Group III

members who have appeared for the shape, in order

of their shop tenure.

(App. 19a.) All of the jobs involve equivalent skills,

regardless of which list the worker who fills them is on. The

jobs are unskilled and most workers either drive trucks or do

floor work. Because the contract provides that a Regular

Situation is required for Union membership, only Regular

Situation holders and members of Groups I and II are Union

members. Finally, the Group system provides the priority list

for filling Regular Situations as they may become vacant.

(App. 20a.)

The Union was founded in 1901 and apparently had

no minority members. Historically, the Union constitution

limited membership to "the first bom legitimate son" of a

member. (App. 20a.) The industry had a closed shop and

Union members were consistently hired before non-Union

men at all industry shapes. Prior to 1952, when the Group

structure was adopted, the Union’s nepotistic policy resulted

in discrimination against minorities (and, of course, women)

and foreclosed them from any employment in the industry.

Although the Group structure appeared on its face to

discard discriminatory policies and to open up Union

membership and employment policies to the entire labor

force, "there is uncontroverted evidence that certain . . .

provisions of the contract have been administered

haphazardly, and that the Group structure has been

circumvented by friends and family of Union members. In

practice . . . no non-Union Group III shaper in the industry

has achieved a Regular Situation, and thus Union

membership, by moving up the Group system since 1963."

(App. 21a.)

8

Since minorities had historically been denied free and

equal access to Union membership, the result was that they

continued to be almost totally excluded from the industry.

In 1974, there were 4,200 members of the Union, including

900 pensioners. More than 99% of these Union members were

White. Of 2,855 persons actively working in the industry,

including 2,460 Regular Situation, 123 Group I members,

and 272 Group III members, only 70 persons — or 2% —

were African American, Spanish-sumamed, Asian, or Native

American. (App. 21a-22a.)

Thus, twenty years after the industry instituted a

purportedly neutral Group structure of employment and

hiring priorities, minorities were still almost totally excluded

from the industry. Based on statistical analyses presented by

the EEOC, Judge Pierce found that the relevant work force

for the industry in 1974 was 30% minority. Therefore, their

participation was "still grossly disproportionate" to what

would be expected in the absence of discrimination. (App.

22a.)

2. The Consent Decree.

Based on the above findings regarding discrimination

against minorities in the industry, Judge Pierce approved the

settlement agreement presented by the parties. (J.A. 50-99.)

All parties voluntarily agreed to the entry of an injunction

that was designed to end the entrenched practices in the

industry that had excluded minority workers.

The injunction was in three parts, all of which ran

against both the union and the employers. Section A, titled

"Equitable Relief' was described by Judge Pierce thus: "As

with many resolutions of employment discrimination cases,

the Settlement Agreement in these actions contains general

provisions permanently enjoining the defendants from

discriminatory practices in violation of Title VII." (App.

22a.) Section A provides, inter alia:

defendant [NMDU] . . . will be permanently enjoined

9

from engaging in any act or practice which has the

purpose or effect of discriminating against any

individual or class of individuals on the basis of race,

color or national origin . . . nor shall they take any

action which would deprive or tend to deprive any

individual of employment opportunities or otherwise

adversely affect his status as an employee or as an

applicant for employment because of such individual’s

race, color or national origin.

defendant employers. . . will be permanently enjoined

from engaging in any act or practice which has the

purpose or the effect of discriminating against any

individual or class of individuals in their bargaining

units represented by NMDU on the basis of race,

color or national origin. They shall not fail or refuse

to hire for employment any such individual on the

basis of race, color or national origin, not shall they

take any other action which would deprive any such

individual of equal employment opportunities or

otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee

or as an applicant for employment because of such

individual’s race, color or national origin.

(J.A. 57-58.)(Emphasis added.)

Section B of the consent decree established an

Administrator, who was empowered "to take all actions . . .

as he deems necessary to implement the performance of the

Order." The Administrator was not only to supervise the

new affirmative action provisions of the decree closely, but

also to closely supervise "employment opportunities in the

industry on behalf of all workers." (J.A. 59) The powers of

the Administrator included determining "all complaints that

any individual in the bargaining units in the industry

represented by NMDU has been allegedly denied equal

employment opportunities on the basis of race, color or

national origin." (App. 57a.) Some of the Administrator’s

duties were explicitly tied to rectifying or deterring areas of

10

industry practice that were particularly abused in the past —

e.g., use of layoffs and transfers to "jump" non-minority

drivers over minorities, or issuing arbitrary Group lists.3

Section C of the decree, entitled "AFFIRMATIVE

ACTION PROGRAM," provided that the defendants shall

institute an affirmative active program "designed so that a

sufficient number of minority workers [Black, Spanish-

sumamed, Oriental, and American Indians] will be employed

by the defendant employers (and accepted for membership

by NMDU as provided herein) within the bargaining units

represented by NMDU in order to achieve a minimum goal

of 25% minority employment in the industry within such

bargaining units by June 1, 1979." (J.A. 60-61; emphasis

added.) The decree contained detailed provisions by which

the goal of 25% minority employment by June 1, 1979, was

to be reached. The Administrator was given broad powers

to oversee the carrying out of the affirmative action plan and

3Judge Pierce further described the role of the Administrator:

The Administrator appointed in these consolidated actions

will be charged with the responsibility of seeing that the terms

of the Settlement Agreement under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 are diligently and conscientiously

implemented. This Act was designed primarily to protect,

and provide a more effective means to enforce, the civil rights

of persons within the jurisdiction of the United States. It

aims, inter alia, to eliminate discriminatory practices by

businesses, labor unions, or employment agencies and thereby

to encourage the growth of economic opportunities for

minority individuals, thus strengthening the economic

foundation essential to the full enjoyment of civil rights.

* * * *

In light of these broad national purposes, this Court considers

it of paramount importance that the Administrator it appoints

here possess a finely tuned sensitivity to the social impact of

past discriminatory employment practices, and a balanced

sense of dedication and commitment to the elimination of

these practices.^

(App. 30a.)

11

to ensure that the goal was reached. Judge Pierce

summarized the major features of the plan:

. . . elimination of past abuses of the Group system;

elimination of the contract provision which restricted

Group I to former Regular Situation holders;

provision for an orderly flow of Group III

shapers—alternating one minority person with one

non-minority person—into steady and secure

employment in the industry, first as members of

Group I and from there, as Regular Situations

become vacant, to Regular Situations. Union

membership will be offered to each Group III worker

as he reaches the bottom of Group I. The plan

further provides that until the 25% minority employment

goal is achieved, employers shall hire, at the entry level,

three minority persons for every two non-minority

persons. In addition, minorities who are presently

active on Group III at the News and the Times will

immediately move to the bottom of the Group I list,

with an equal number of non-minorities to

immediately follow them onto the Group I list.

(App. 23a-24a; emphasis added.)

With regard to the 25% minority employment goal in

particular, Judge Pierce’s opinion made findings that it was

justified because the relevant workforce as of 1974 was 30%

minority. Therefore he held that a goal of 25% minority

representation in the industiy by June, 1979, was

appropriate. (App. 28a-29a.)

The Second Circuit affirmed Judge Pierce’s order in

all respects. In its decision it recited the long history of

discrimination in the industry:

While the current Group Structure, which was

adopted in 1952, appears on its face to open Union

membership to anyone in the labor force, Union

membership, because of lax administration of the

12

contract provisions, has largely remained attainable

only by the family and friends of a Union member.

Manipulations of the system that resulted in the maintenance

of a virtually all-white work force included "artificial inflation

of the Group I lists," "fictitious lay-offs," and "outright false

assertions of Group I status by persons who have obtained

Union membership cards, the validity of which have not been

challenged by employers." These practices violated Title VTI

by locking in "‘minorities at the non-union level of entry in

the industry, and thereby . . . perpetuating] the impact of

past discrimination.’" (App. 40a-41a.) The court affirmed

the propriety of the 25% hiring goal specifically on the basis

of its relationship, as found by Judge Pierce, to the relevant

labor force as demonstrated by the 1970 census. (App. 44a.)

3. Compliance with the Affirmative Action

Provisions.

In late 1979, defendant New York Daily News filed

a motion seeking relief, under Rule 60(b), F. R. Civ. Proc.,

from certain provisions of the decree, particularly

termination of the Administrator, whose term was set at five

years, subject to being extended by the Court. Judge Pierce

denied the motion and reappointed the Administrator as

Interim Administrator. Judge Pierce specifically noted the

failure of the defendants to meet the 25% goal within the

time provided by the decree. Indeed, he found that the

industry was only 12.16% minority, less than half of the goal

that was set five years before. (App. 58a.)

4. The Role of the Administrator.

Throughout the life of the decree, the Administrator

has played a vital role in overseeing compliance. Under the

provisions of the settlement agreement, minority workers

were able to file claims and to secure orders, where justified,

to require compliance. Between 1974 and the end of 1981,

at least 91 claims had been submitted and adjudicated, in

some instances through appeals to the district court judge.

13

By the date of the dissolution of the decree, at least 278

claims had been submitted to the Administrator. Of key

importance, as will be discussed in more detail below, has

been the Administrator’s role in ensuring that proper Group

III and Group I lists were promulgated and in verifying the

level of compliance with the Affirmative Action plan.

5. The Motions to Dissolve the Consent Decree.

In April, 1985, a number of the defendants filed new

motions to vacate the order of Judge Pierce with regard to

the Affirmative Action provisions and the Administrator.

The basic argument made in support of these motions was

that the 25% goal had been reached and that therefore the

decree was no longer necessary.

Both the private plaintiffs and the EEOC strenuously

objected to these motions.4 Both agreed that Section A of

the decree, embodying permanent injunctive relief, should be

retained in its entirety. The private plaintiffs also urged that

the court retain both the affirmative action provisions and

the Administrator until full compliance with the decree had

been demonstrated.

Judge Conner ordered that notice be given to the

class that the Consent Decree might be vacated. After

extensive pre-hearing briefing, an evidentiary hearing was

begun in 1987. Judge Conner suspended the hearing when

it became evident that the defendants could not prove that

minority employment had in fact reached an asserted 24.89%

industry-wide. (J.A. 272-73.)

4While the EEOC initially took the position that the

Administrator should be retained, in 1991 it took the view that only

the permanent injunction provisions needed to be retained.

14

6. Plaintiffs’ Response — The History of Non-

compliance.

Plaintiffs presented substantial evidence that there

had been a consistent pattern of violations of the decree.

Specifically, after the defendants had filed their repeated

motions to vacate the decree, the Administrator found

various of the defendants had violated the decree and

engaged in intentional discrimination. The following

examples are illustrative.

a. In 1987 the Administrator held that the Daily

News and the NMDU had violated the decree when they

issued a new Group III list. The Administrator required

them to use a revised list that was constructed in adherence

to the requirements of the permanent injunction in Part A

of the Decree and that would be consistent with the goals

and timetables provisions in Part C. Judge Conner affirmed

the decision on appeal by the NMDU. (App. 68a-74a.)

b. In 1990 the Administrator held that the New York

Times and the NMDU had engaged in intentional

discrimination in violation of a number of the provisions of

the Decree, including Part A when they issued a new Group

III list that did not comply with the 3/2 ratio required by the

Decree. He also found that the Times and the Union

violated 11 15 of the decree dealing with the standards to be

followed in giving preferences to certain employees to be

placed on a Group III list, 11 29, dealing with the

establishment of a system for the submission of applications,

and 1111 1 and 2, the general injunction provisions, in that

there was intentional discriminatory treatment with regard to

the offlist hiring of minority employees and other practices

of the industry.5 (J.A. 415.) Again, the decision of the

5The Administrator had instructed the Times and the Union not

to issue the list, but they did so anyway. The hearing on this matter

(Claim 186) began in October, 1985, and ended 6,000 transcript pages

later in May 1988. As a result of the Administrator’s subsequent

15

Administrator was affirmed by Judge Conner. (App. 75a-

92a).

c. In 1991 the Administrator found that the NMDU

and the Westfair Newspaper Distributors had engaged in

intentional discrimination and retaliation in violation of Part

A by passing over two minority workers in favor of white

workers. (J.A. 537-38.)6

d. In 1989 the Administrator found that a black

driver had been discharged by Metropolitan News for racially

motivated reasons. (J.A. 397.) On appeal to Judge Conner,

the claim was settled by giving the claimant a Regular

Situation and damages. (Rec. #224.)7

In addition, in 1991 plaintiffs submitted to the district

court and the Administrator, as an Offer of Proof in

opposition to the Motions to Dissolve the Decree, the

affidavits and declarations of 29 minority employees attesting

to continuing acts of discrimination in violation of the

Decree. The complained of acts included restrictions in

training opportunities, discrimination in the filling of

foreman and supervisory positions, and an increase in

retaliation and threats for complaining of discrimination.

orders with regard to Claim 186, half of the 47 Regular Situation

positions filled in the summer of 1992 went to minority workers.

Proceedings to determine back pay for the Claim 186 claimants are

still pending.

'This claim was settled by the parties pending an appeal to Judge

Conner.

7In addition to these post-1985 claims, in 1984 the Administrator

found that the New York Post and the Union had violated 1115 of the

Decree and had obstructed "the goals of the consent decree in seeking

minority employment.” He required the reordering of the Group I list

and the Regular Situation Holders. Administrator’s Decision in Claim

165, Jan. 4, 1984, p. 1. (Rec. # 69.) This order was affirmed by

Judge Conner on July 10, 1984. (Rec. #73.)

16

Plaintiffs’ Offer of Proof and Declarations, August 19, 1991.

(Rec. #228.)

As noted above, in 1987 Judge Conner found the

evidence insufficient to establish that the industry as a whole

had met the 25% goal. (J.A. 277.) However, in 1988 he

suspended the 3/2 ratio for placing workers on the Group III

list. (J.A. 310.) Further briefing was requested on the

defendants’ motions to dissolve the decree. In the

meantime, other individual claims of discrimination

continued to be filed with the Administrator relating, inter

alia, to carrying out the relief ordered with regard to the

above listed matters. It was not until 1991, after Judge

Conner ordered that compliance reports relating to the 25%

goal be verified, that the defendants adduced legally

competent evidence to support their claim that the goal had

been reached and that 27.97% of the Regular Situation

holders in the industry were minority.

The plaintiffs, on the other hand, argued that the goal

should be adjusted to reflect the current labor market, which

had increased to 42.4% minority according to the 1980

census8 and to over 50% minority according to the 1990

census.9 Since the 25% goal had not been reached until 12

years after the decree required, they suggested, the goal

should be adjusted to reflect changed circumstances.

7. The Decision of the District Court.

On August 8, 1992, Judge Conner issued his decision

dissolving the consent decree and the injunction embodied

in it in its entirety. The reason given was that the 25% goal

had been reached and that therefore the purpose of the

decree had been satisfied. With regard to the private

plaintiffs’ evidence that the defendants had violated anti

8Judge Conner accepted this figure as accurate. (J.A. 265.)

9J.A 697-98.

17

discrimination provisions of the decree in a variety of

respects, the court held:

Even assuming, arguendo, the LDF’s proposition that

defendants have continued to violate the Consent

Decree and that discrimination remains prevalent in

the industry, such arguments are not relevant to

defendants’ application for vacation of the Consent

Decree.

* * *

. . . The Court granted the LDF an opportunity to

request an evidentiary hearing before the

Administrator on the only fact relevant to the issue of

whether to terminate the Consent Decree — whether the

25% minority employment goal has been achieved. The

LDF did not avail itself of that opportunity for over

six months and cannot be heard to complain now.

(App. 114a-115a; emphasis added.)

The private plaintiffs filed a notice of appeal and a

motion to reinstate the injunction pending appeal. In

support of that motion they introduced affidavits from

minority workers alleging further current discriminatory

actions. (J.A. 719-77.) Although the district court denied

that motion, it reaffirmed the jurisdiction of the

Administrator to enforce prior orders and to resolve claims

filed prior to August 8,1992. (App. 127a-128a.) The EEOC

also filed a notice of appeal. As noted above, the Court of

Appeals affirmed the decision of the district court without

mentioning, let alone addressing, the evidence of continuing

violations of the decree.

18

R e a s o n s f o r G r a n t in g t h e W r it

In t r o d u c t io n

This case presents important issues concerning the

standards that govern the dissolution of a consent decree

entered as part of a negotiated settlement. Although this is

a civil rights case, the decision below necessarily applies to

all actions brought under federal law in federal court. First,

the case raises squarely the question of whether this Court’s

seminal decision in United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106

(1932) has any continuing vitality or whether, as the lower

court held, it has been overruled sub silentio by Rufo v.

Inmates o f Suffolk County Jail, 502 U.S.___, 116 L.Ed.2d 867

(1992).10

Second, the case raises the question of the meaning

of the requirement reiterated by this Court in Freeman v.

Pitts, 503 U .S .___, 118 L.Ed.2d 108, 139 (1992), Board of

Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell, 498

U.S. 237, 249-50 (1991) and Rufo, 116 L.Ed.2d at 886-87,

that a defendant has a heavy burden of demonstrating good

faith and substantial compliance with a consent decree as a

precondition to having it modified or dissolved.

Third, the decision below has important implications

concerning the binding effect of negotiated settlements and

the impact on the settlement process of defendants being

able to obtain dissolutions of consent decrees without

demonstrating full compliance with all aspects of the

agreement. In short, the question is, should a prohibitory

injunction be vacated in the face of proof of continuing

violations, based solely on proof (here disputed) that relief

10Here, the issue arises in a case involving a negotiated settlement

that embodies an injunction. The issue of whether the standard of

Swift or that of Rufo governs modification or dissolution of an

injunction also arises when the injunction has been imposed by a

federal court as a result of a litigated case.

19

designed to remedy past acts of discrimination has been

carried out.

I. T h e Ca s e Pr e se n t s a n Im p o r t a n t Q u e st io n

R e g a r d in g t h e St a n d a r d T h a t Sh o u l d

G o v e r n t h e D isso l u t io n o f Co n s e n t D e c r e e s

A b o u t W h ic h T h e r e Is C o n flic t B e t w e e n th e

C ir c u it s .

The basis for the decision below was that the

standard established for modifying or dissolving consent

decrees established by United States v. Swift & Co., supra,

had effectively been superseded by this Court’s decisions in

Dowell and Rufo. The court acknowledged that the district

court’s decision in this case was apparently the first that so

held (App. 8a.) It also acknowledged that "[ajmong other

circuits, there appears to be some dispute as to the

appropriate standard for modifying consent judgments."

(App. 9a.)

Indeed, it is apparent that there is both conflict and

uncertainty in the lower federal courts as to whether Dowell

and Rufo overruled Swift & Co. Thus, while the Seventh

Circuit has held that Swift & Co, was completely overruled

by Rufo (In re Hendrix, 986 F.2d 195, 198 (7th Cir. 1993)),

the Sixth and Eighth Circuits have only applied Rufo to

cases involving governmental entities (Lorain NAACP v.

Lorain Bd. o f Educ., 979 F.2d 1141 (6th Cir. 1992); Epp v.

Kerrey, 964 F.2d 754 (8th Cir. 1992)), and the Federal Circuit

has declined to apply the Rufo standard to commercial

litigation involving a private defendant (W.L. Gore &

Associates, Inc. v. C.R. Bard, Inc., 977 F.2d 558 (Fed. Cir.

1992)). The lack of certainty in the lower courts was

recently discussed in the A.T. & T. anti-trust case, United

States v. Western Electric Co:, In c .,__ F. Supp. ___ , 1994

WL 143082, p. 6 (D.D.C. April 5, 1994), citing United States

v. Western Electric, Co., Inc., 969 F.2d 1231, 1235 n. 7 (D.C.

Cir. 1992).

20

Of course, neither Dowell nor Rufo explicitly

overruled Swift & Co. To the contrary, those decisions only

held that the Swift standard should not be applied to cases

involving local government institutions because permanent

governance by a federal court tended to undermine the

representative and democratic character of such institutions.

The fact that Swift was not explicitly overruled, in decisions

that discuss its principles at some length, militates against a

conclusion that Swift was, nevertheless, overruled sub silentio.

In any event, given the importance of the role of

settlement and consent decrees in disposing of litigation in

the federal courts, it is imperative that both litigants and the

lower courts understand clearly what is the standard

governing modification and dissolution of consent decrees.

Therefore, this Court should grant certiorari to clarify and

make explicit whether and to what extent the Swift standard

still has vitality.

II. T h e D e c isio n s o f t h e C o u r t s B e l o w C o n f l ic t

W it h D e c isio n s o f T h is C o u r t T h a t R e q u ir e

T h a t a D e f e n d a n t D e m o n s t r a t e C o m p l ia n c e

W it h a C o n s e n t D e c r e e B e f o r e T h e D e c r e e

Ca n B e D is s o l v e d .

As set out above, the district court itself had held on

a number of occasions after the motions to dissolve the

injunction had been filed, that both the Union and various

of the other defendants had violated the decree and, indeed,

had committed acts of intentional discrimination. Moreover,

the private plaintiffs, petitioners herein, had introduced and

proffered extensive evidence of other violations of specific

provisions of the decree during the same period of time.

Nevertheless, the district refused to consider this

evidence, holding that it was "irrelevant" in deciding whether

to dissolve the decree in its entirety. Rather, it held that

since one provision of the decree, that the industry have 25%

21

minority drivers, had been complied with, the decree could

be dissolved.11

Under the decisions of this Court, it was clear error

for the district court to hold that whether the defendants

had continued to violate the consent decree was irrelevant

to whether the decree should be dissolved. It was also error

for the Court of Appeals to fail even to address this

contention of plaintiffs. Thus, in Dowell the Court directed

the district court to "address itself to whether the Board had

complied in good faith with the . . . decree since it was

entered" in deciding whether the decree should be dissolved.

498 U.S. at 249-50. Rufo held that where modification of a

decree is sought because of unforeseen changed

circumstances that make compliance difficult or

"substantially more onerous," the party seeking modification

must "satisfy a heavy burden" to demonstrate that it "made

a reasonable effort to comply with the decree." 116 L.Ed. 2d

at 886-87. And in Freeman, the Court made clear that a

demonstration by the defendant of good faith compliance

with a decree is a prerequisite to being relieved of its

requirements. Thus, "[w]hen a school district has not

demonstrated good faith under a comprehensive plan to

remedy ongoing violations, we have without hesitation

approved comprehensive and continued district court

supervision." 118 - L.Ed.2d at 139. Moreover, a

demonstration of good faith compliance with part of decree

uThe petitioners continue to dispute whether even this provision

of the decree had been complied with. The decree is clear that the

goal was to achieve 25% minority representation by June 1, 1979,

when such representation would reasonably reflect the relevant labor

market. That goal was not achieved, and the defendants could not

demonstrate that the industry was over 25% until 1991, twelve years

late, and when the relevant labor market was over 50% minority.

Thus, the effect of the lower court decision was to convert a goal

designed to measure reasonable compliance into a rigid upper-limit

quota that freed the defendants from further compliance with the

settlement.

22

can only result in relief from those parts of the decree

complied with. Id. at 139-40.

The decision below is therefore in clear conflict with

governing decisions of this Court. Even if the Swift standard

does not govern, the decisions in Dowell, Rufo, and Freeman

mandate reversal.

III. T h e D e c isio n o f t h e C o u r t B e l o w W ill

U n d e r m in e t h e Se t t l e m e n t o f Ca se s in

F e d e r a l C o u r t .

This Court has repeatedly held that the settlement of

cases is highly favored, and has applied this rule to civil

rights litigation on a number of occasions. See, e.g., Evans

v. Jeff D., 475 U.S. 717, 732-33 (1986); Marek v, Chesny, 473

U.S. 1, 10 (1985). Albeit unintentionally, the decision below

will substantially discourage plaintiffs from settling complex

employment discrimination and other civil rights litigation.

Settlement decrees in these types of cases are

achieved through an extensive and complicated process of

negotiation. The result is inevitably a compromise, based on

interdependent promises and obligations. A carefully

framed decree will spell out the relationships between its

provisions and when and under what circumstances certain

provisions may be terminated. The decree in the present

case is no exception.

As set out in the Statement of the Case above, the

decree contained general prohibitions against discrimination,

as well as a variety of specific obligations undertaken by the

defendants, including receiving and processing applications

for membership, the handling of grievances on a

nondiscriminatory basis, the admission to membership in the

Union of persons listed on an employer’s Group I list on the

same basis as others, assisting persons to obtain and retain

membership, and the maintenance of registers and other

23

records. The decree also contained affirmative action

provisions keyed to the goal of 25% minority representation

by June 1, 1979, and provided for an Administrator to

oversee the carrying out of the decree and to receive and

adjudicate complaints of noncompliance.

The affirmative action provisions are intended to

further the fundamental purpose of the decree that are set

out in Part A ,i.e., the elimination of discrimination in the

industry. The 25% representation was to be reached by

June 1, 1979, when that representation was still related to

the relevant labor market. If that goal was met on time,

then the 50% and 60% hiring ratios would end. However,

the settlement contemplated that the permanent parts of the

decree would remain, and that the defendants would

continue to be enjoined from engaging in discrimination

prohibited by Title VII and by the decree itself, as well as

required to follow various procedures set out in the decree.

Of course, under principles now made clear by this Court,

the defendants could seek the dissolution of even these parts

of the decree by meeting their burden of demonstrating

good faith compliance, i.e., that they were no longer engaged

in acts of discrimination. This they utterly failed to do.

Rather, the Court of Appeals has sanctioned virtually

unlimited and unreviewable discretion to district courts to

rewrite and dissolve a comprehensive settlement if any part

of it has been complied with. This result derives from what

the court below termed a "flexible standard for modifying

decrees" whose purpose is to correct pervasive discrimination

in an entire industry.

The message of the decision below to defendants,

therefore, is that belated compliance with some goal

embodied within a complex decree will mean freedom from

all other contractual obligations into which they freely

entered. The message to plaintiffs is equally clear; they can

no longer rely on the sanctions of the law to enforce a

settlement decree carefully negotiated and approved. Not

24

only do defendants not have to demonstrate compliance, but

their protracted violation of a decree will be deemed

"irrelevant." Plaintiffs’ proof of continuing and serious

breaches of an agreement and continued rampant

discrimination will result in their being told that they must

bring a new lawsuit.12 Intransigence, if persisted in long

enough, will thus be rewarded.

The combined force of these messages to plaintiffs is

that only if they go forward and prove discrimination can

they have confidence that a decree will remain in force until

it is obeyed. A settlement, no matter how broad and

inclusive it may be, cannot be relied upon. Such a result

destroys any incentive for plaintiffs to enter into a settlement

and, therefore, undermines the favored status of settlements

established by decisions of this Court.

12See the Appendix at 114a-116a.

25

C o n c l u s io n

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted and the decision of the court

below reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

D irecto r -Co u n sel

Th e o d o r e M. Shaw

Charles Steph en Ralsto n

(Counsel of Record)

NAACP Leg al D efense a n d

E d u c a tio n a l Fu n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Pe n d a D . Ha ir

NAACP Leg al D efense a n d

Ed u c a tio n a l Fu n d , In c .

1275 K. Street, N.W,

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Petitioners