Wooten v. Moore Appellees' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wooten v. Moore Appellees' Brief, 1968. f8c5ae78-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b270ef0-3697-4c9d-b28a-fbcf7bc0da5d/wooten-v-moore-appellees-brief. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

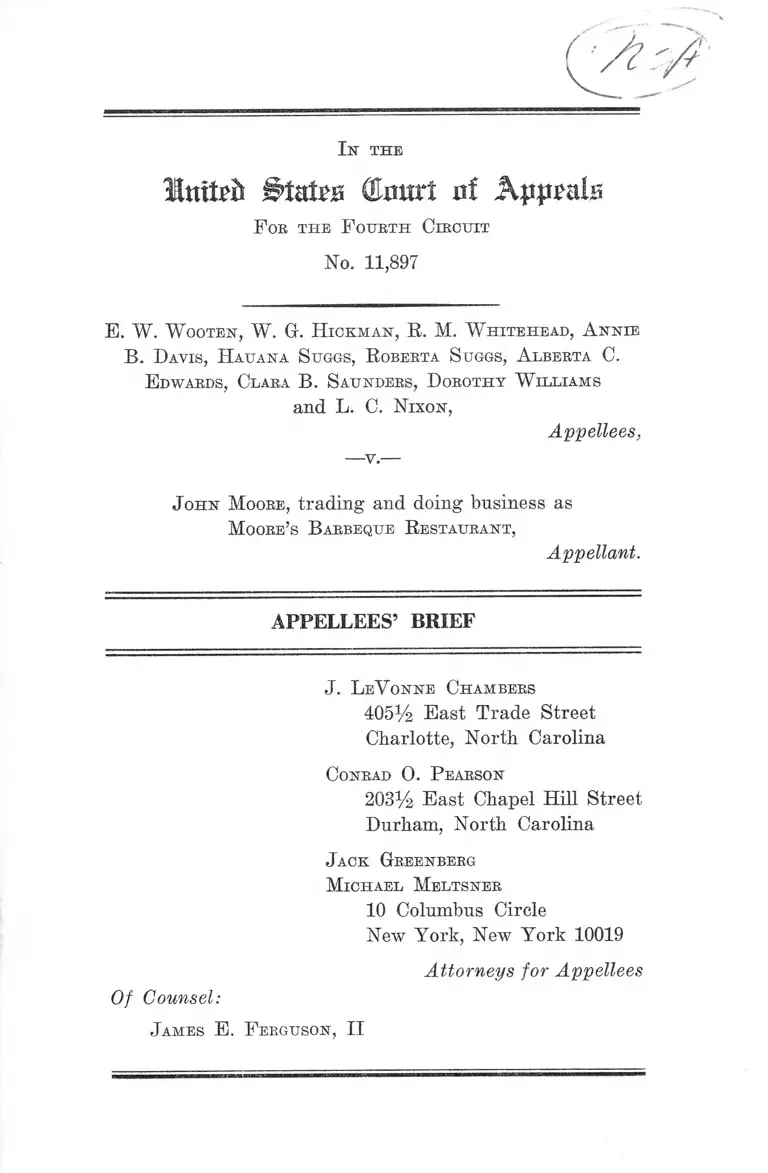

I n' the

Irnfrft States (Emirt ni Appeals

F oe the F otjeth Circuit

No. 11,897

E. W. W ooteh, W. G. H ickman, E. M. W hitehead, A nnie

B. Davis, H auana S uggs, R obekta Suggs, A lberta C.

E dwards, Clara B. Saunders, Dorothy W illiams

and L. C. Nixon,

Appellees,

-v -

J ohn Moore, trading and doing business as

Moore’s B arbeque R estaurant,

Appellant.

APPELLEES’ BRIEF

J. L eV onne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Conrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Jack Greenberg

M ichael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellees

Of Counsel:

James E. F erguson, II

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 1

Questions Involved....... ................ ........ ................ ........... - 4

Statement of Facts ............................................................ 5

A rgument

I. The United States Congress Has Abundant Pow

er to Prohibit Racial Discrimination in a Res

taurant Having the Capacity to Serve 100 Cus

tomers, Located on a United States Highway,

Selling Over $160,000 Worth of Food Annually,

Advertising Through Newspapers, Radio and

Television and Serving at Least Some Interstate

Travelers .................................................................... 8

II. The Court Below Was Clearly Correct in Finding

That Defendant’s Restaurant Is Covered by the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 on the Basis of Defen

dant’s Own Admission That He Did Serve Some

Interstate Travelers, and the Uncontradicted Tes

timony of Six White Witnesses That They Had

Eaten at the Restaurant and That No Inquiry

Had Been Made of Them as to Their Residency 12

III. The Court Below Erred in Finding That Defen

dant Did Not “ Offer to Serve” Interstate Trav

elers in That Its Advertising Contained No Such

Disclaimer and Its Location Would Attract In

terstate Travelers; the Court Also Erred in Find

ing That “ a Substantial Portion of Its Food . . .

or Other Products” Had Not Moved in Commerce 16

Conclusion 21

II

Table of Cases

PAGE

Bolton v. State, 220 Ga. 632, 140 S,E.2d 866 (1964) ..... 9

Consolidated Edison Co, v. Labor Board, 305 U.S, 197

(1938) ...... .......................................................................... 10

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat 1, 6 L.ed. 23 (1824) ........... 10

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) ........................... 8

Gregory v. Meyer, 376 F.2d 509 (5th Cir. 1967) .....8,19,20

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964) ....................... 8

Katzenbach v. McClnng, 379 U.S. 294 (1964) ...........8, 9,10,

11, 12, 20

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 377 F.2d 433

(4th Cir. 1967) .......................................................... 8,11,19

Polish Alliance v. Labor Board, 322 U.S. 643 (1944) .... 10

The Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, 379

U.S. 241 (1964) .......................................................... 8, 9,11

United States v. Wrightwood Dairy Co., 315 U.S. 110

(1942) ................................................................................ 10

Wickard v. Filbnrn, 317 U.S. I l l (1942) .....................10,11

Willis v. Pickrick Restaurant, 231 F. Supp. 396 (N.D.

Ga. 1964) .......................................................................... 9

Statutes I nvolved

42 U.S.C. §2000 (a)

42 U.S.C. §2000(b)

42 U.S.C. §2000 (c)

... 13

... 13

.13,14

Ill

Other A uthorities

PAGE

110 Cong. Rec. 1901 .......................................................... 14

110 Cong. Rec. 1903 .......................................................... 15

110 Cong. Rec. 7177 .......................................................... 17

Hearings before Comm, on the Judiciary, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess. Part II ..................................................... ....... 19

Hearings before Senate Comm, on Commerce, 88th

Cong., 2d Sess. 20

I n the

l u t ( d m t r t of Appals

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 11,897

E. W . W ooten, W . G. H ickman, R. M. W hitehead, A nnie

B. Davis, H auana Suggs, R oberta Suggs, A lberta C.

E dwards, Clara B. Saunders, D orothy W illiams

and L. C. Nixon,

Appellees,

— v.—

J ohn Moore, trading and doing business as

Moore’s B arbeque R estaurant,

Appellant.

APPELLEES’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal by defendant John Moore from an

order1 entered by the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of North Carolina enjoining him from

discriminating against Negroes in the operation of Moore’s

Barbecue Restaurant.

The action was initially filed on November 10, 19642

(Appellant’s App. I ) 3 by several Negro plaintiffs seeking

1 The opinion and order filed July 18, 1967, are printed in defendant-

appellant’s appendix at p. 23.

2 This date was mistakenly printed as November 10, 1966, in appellant’s

brief, p. 2.

3 Appellant’s appendix is hereinafter cited as “App. ------ ” . Appellees’

appendix is hereinafter cited as “------ a” .

2

injunctive relief against racially discriminatory practices

by the defendant as violative of plaintiffs’ rights under

the Commerce Clause and Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States, Title II of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000a et seq. and 42 U.S.C.

§1981. Jurisdiction was invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§1343(3) and 42 U.S.C. §2000a-6(a). Plaintiffs sought relief

on their own behalf and on behalf of others similarly

situated pursuant to Eule 23 of the Federal Eules of

Civil Procedure.

Defendant filed answer to the complaint (App. 6) and

to plaintiffs’ interrogatories (5a and see la ) and requests

for admission (13a and see 4a) on February 4, 1965.

Plaintiffs filed additional interrogatories (14a) on Feb

ruary 24, 1965, to which defendant filed answers (18a)

and objections (19a) on March 8, 1965. Defendant’s ob

jections were heard by the Court on April 12, 1965, and

an order (21a) was entered on May 4, 1965, allowing

plaintiffs to examine certain records of purchases by

defendant.

Plaintiffs deposed defendant’s suppliers and five per

sons (22a, 36a, 54a, 69a, 74a) who had eaten at defendant’s

restaurant and the defendant on July 22, and 23, 1965. On

November 22, 1965, a pretrial conference was held.

On July 22, 1966, the United States Government filed

application to intervene. The application for intervention

was heard by the Court on October 24, 1966, following

which the Court on January 10, 1967, disallowed the inter

vention (87a). On October 31, 1966, plaintiffs moved for

a preliminary injunction (80a) which was denied by the

Court on December 31, 1966 (85a).

3

The cause came on for hearing on the merits on April 17,

1967 (103a) at which time plaintiffs offered and the Court

admitted (106a) the depositions of defendant’s suppliers,

depositions of five white persons who had eaten at defen

dant’s restaurant and the deposition of defendant. Plain

tiffs also offered, without objection, exhibits, answers to

interrogatories and admissions of defendant. Another

white person (161a) who had eaten at Moore’s Barbecue

Restaurant testified at the hearing. Defendant offered

several exhibits and testified himself (108a). Plaintiffs

renewed their motion for a preliminary injunction in June,

1967 (100a).

On July 18, 1967, the Court entered its opinion and

order (App. 23) enjoining defendant from discriminating

against plaintiffs and other Negroes. The Court found

that defendant’s restaurant came within the requirements

of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

2Q00a(c)(2), in that it served interstate travelers and

that it was principally engaged in selling food for con

sumption on the premises. The Court also found that

defendant did not “ offer to serve” interstate travelers,

and that a “ substantial portion of the food” served by

defendant had not moved in interstate commerce.

Defendant noted an appeal on August 17, 1967. Upon

defendant’s motion an order was entered extending the

time for a period of ninety days from August 17, 1967

for filing the record and docketing the appeal.

On December 22, 1967 plaintiffs filed a motion to dis

miss the appeal on the ground that the case had become

moot. After a hearing, this Court entered an order on

January 22, 1968 denying plaintiff’s motion. The Court

entered an order fixing the time for filing appellees’ brief

and appendix to twenty days from January 22, 1968.

4

Questions Involved

I.

Whether the Congress of the United States has the

Constitutional power to forbid racial discrimination in a

restaurant having the capacity to serve 100 customers,

located on a United States Highway, selling over $160,000

worth of food annually, advertising to the general public,

and serving, at least some, interstate travelers.

II.

A. Whether the Court below erred in finding that de

fendant’s restaurant was covered by the Civil Eights Act

of 1964 on the basis of defendant’s own admission that he

did serve some interstate travelers, and the uncontradicted

testimony of six white witnesses that they had eaten at

the restaurant and that no inquiry had been made of them

as to their residency.

B. Whether the Court below erred in finding that defen

dant did not offer to serve interstate travelers on the

basis of evidence showing that he had engaged in a sub

stantial amount of advertising, that he was located on a

major United States Highway, that he had posted two

signs which read that he did “not cater to interstate

travelers” and that he did not query all of his customers

as to their origin.

C. Whether the Court below erred in finding that a

substantial amount of defendant’s food had not moved in

interstate commerce where the evidence showed that he

had made purchases of nearly $7,000 from out of state

suppliers over a three year period, and that he had pur

5

chased other goods from North Carolina suppliers which

had, in whole or in part, moved in interstate commerce.

Statement of Facts

Defendant John Moore owns and operates Moore’s Bar

becue Restaurant at 1220 Broad Street4 * in the City of

New Bern, North Carolina.6 Broad Street is four lanes

and is also U. S. Highway 70 and IJ. S. Highway 17 at the

place where the restaurant is located. There are parking

spaces between the building and the street6 and to the

east of the building.

The restaurant has 25 booths in the dining room with

accommodations for 100 people (120a). Defendant’s total

sales for 1963 was $156,869.59 (11a), for 1964 was

$164,323.87 (11a), and for 1966 was $177,540.95 (134a-135a).

His total purchases for these years were $87,839.39,

$89,701.56 and $99,000 (11a, 134a-135a).

Defendant made purchases directly from out of state

suppliers of $4,038.58 during 1963 and 1964 and $2,732.01

in 1966 (133a-135a). Defendant also made purchases of

goods which had in whole or in part, moved in interstate

commerce from North Carolina suppliers.

4 The operation which is the subject of this appeal has been closed

down. (See Appellees’ Motion to Dismiss this appeal on the ground of

mootness.) Defendant has since opened another restaurant, the subse

quent operation of which, his counsel has said, is contingent upon the

result of his appeal.

The defendant does not dispute the facts as found by the Court below.

(Appellants Brief, pp. 3-4).

6 The restaurant is somewhat over a mile from the United States Post

Office and Court Building in New Bern (33a).

6 Defendant estimated that there are spaces for 20-25 cars (148a).

6

Defendant, in Ms answer, and at all other times has

admitted that he does not serve Negroes in the dining

room of his restaurant. He has asserted, however, that

he does not serve or offer to serve interstate travelers.

See 42 U.S.C. §2000a(e) (2).7 To this end he has posted two

signs approximately one foot by one and one-half feet in

the windows by the entrances to his restaurant with the

following in 1% inch letters:

“We do not cater to interstate patrons and the

principal foods sold in this restaurant are North

Carolina products.” (See App. 26.)

The Court below found, on the basis of defendant’s testi

mony that “ [defendant and members of his family keep

watch on customers entering the restaurant, and when

there is anything to indicate the possibility that a would-be

patron is an interstate traveler, such as a car with out-

of-state license plates, the person is interrogated and if

7 The Court below looked only to the direct interstate purchases in

determining whether a “substantial portion of the food . . . or other

products . . .” sold had moved in commerce. 42 U.S.C. §2000a(c) (2).

Plaintiffs had introduced the depositions of defendant’s North Carolina

suppliers showing that many of these products purchased by the defen

dant had moved in commerce. These depositions are part of the record

on appeal, but are not included in appellees’ appendix. Plaintiffs main

tain here that the Court below erred in failing to consider these products.

(See Argument II B infra.)

The great majority of the products purchased by defendant from the

following suppliers had moved in commerce: Continental Baking Com

pany in Raleigh; The American Bakeries Company in Rocky Mount;

The Henderson Cigar and Candy Company in New Bern; Colonial Stores

in New Bern; Brothers Frozen Foods in Kinston; the C. W. Howard

Company in Kinston; Armstrong Grocery Company in New Bern; Boyd

Brothers in New Bern; and Hayes Crary, Sr. in New Bern.

The ingredients of the products purchased from the following had

moved in commerce: the New Bern Coca Cola Bottling Company; Dr.

Pepper Bottling Company in New Bern; and the Pepsi Cola Bottling

Company in New Bern. Some other products, including containers and

packing materials from other suppliers had moved in commerce. All the

seafood had come from navigable waters.

7

found to be an interstate traveler, is refused service.”

(App. 26).8

Defendant does not indicate his restrictive policy as to

service in any of his advertising in newspapers and on

radio and television9 (151a-152a). Nor is there any indica

tion of this policy on the large signs in front of his restau

rant.

Defendant admitted on direct examination (117a), again

on cross-examination (159a-160a) and the Court found

(App. 26-27) that he did not keep out all people from

outside of North Carolina. Plaintiffs produced at the trial

a witness (161a) who had come to New Bern from Wash

ington, D. C. the day before and who had eaten at Moore’s

without having been interrogated as to his residency. Plain

tiffs also introduced the depositions of five white persons

from outside of New Bern10 who had eaten at Moore’s

restaurant none of whom had been questioned as to their

residency.11

8 Defendant’s counsel pointed ont that the license of a car pulling into

a parking space in front of the restaurant would probably not be visible

to anyone inside, particularly if no license plate appeared on the front

o f the car (45a, 65a).

9 It was shown that one such newspaper carrying his advertising was

given to all guests at the Holiday Inn in New Bern, a modern motel with

100 rooms (42a-43a, 26a).

10 Jack Hornbeck (22a), from Michigan, Adam Stein (36a), from

Virginia and Charles Morgan Smith (54a) from Colorado, all law

students who had recently arrived in North Carolina for the Summer;

also David Townquist (69a) a writer and translater from Durham, North

Carolina and Carol Euth Silver (74a), an attorney from California who

had been working for several months in Durham, North Carolina. Town

quist and Silver visited the restaurant May 5, 1965; Hornbeck, Stein and

Smith on June 10, 1965.

11 Although the Court below stated that these witnesses “ drove up to

the restaurant in ears bearing North Carolina license plates” (App. 28),

the uncontradieted testimony was that Hornbeck, Stein and Smith

arrived in a car with New Mexico license plates (25a), (39a), (55a, 65a).

8

ARGUMENT

I.

The United States Congress Has Abundant Power to

Prohibit Racial Discrimination in a Restaurant Having

the Capacity to Serve 100 Customers, Located on a

United States Highway, Selling Over $160 ,000 Worth

of Food Annually, Advertising Through Newspapers,

Radio and Television and Serving at Least Some Inter

state Travelers.

The defendant seeks a declaration by this Court that

Congress did not have the constitutional power to prohibit

racial discrimination in the operation of Moore’s Barbecue

Restaurant.12 (Appellant’s Brief, p. 8) This argument is

made in the face of The Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v.

United States, 379 U.S. 241, 85 S.Ct. 1, 13 L.Ed 2d 258

(1964) and Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294, 85 S.Ct.

377, 13 L.Ed2d 290 (1964) where all nine justices found

ample constitutional authority for Title II of the Civil

Rights Act. See also, Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306,

85 S.Ct. 384, 13 L.Ed2d 300 (1964); Georgia v. Rachel, 384

U.S. 780, 86 S.Ct. 1783, 16 L.Ed2d 925 (1966); Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 377 F.2d 433 (4th Cir. 1967);

Gregory v. Meyer, 376 F.2d 509 (5th Cir. 1967); Willis v.

Townquist and Silver testified that they arrived in a ear rented in

Durham (69a, 75a).

Stein and Smith also all testified that on the day they visited the

restaurant they noted a car parked in Moore’s lot with Florida license

plates (42a, 58a).

12 Alternatively defendant argues that he is not covered by the terms

of Title II o f the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Appellant’s brief, p. 19)

or that the Act should be read restrictively to exempt him. These con

tentions are met in the second part of this brief, infra.

9

Pickrick Restaurant, 231 F. Supp. 396 (N.D. Ga. 1964) (3

judge Court), appeal dismissed, sub nom. Maddox v. Wil

lis, 382 TJ.S. 18; Bolton v. State, 220 Ga. 632, 140 S.E.2d

866 (1964).

The Supreme Court found the necessary constitutional

support for Title II in the Commerce Clause.13

“Our study of the legislative record, made in light of

prior cases, has brought us to the conclusion that

Congress possessed ample power in this regard. . . . ”

Heart of Atlanta, 379 U.S. at 250.

The Court reviewed the legislative history of the Act and

found reasonable testimony indicating that interstate com

merce was burdened in a variety of ways because of

prevailing racial discrimination in places of public ac

commodation. The Court noted, among other things, that

the legislative history showed that in our mobile society

commerce was adversely affected because the travel of

Negroes was inhibited by discrimination in public accom

modations, Heart of Atlanta, 379 U.S. at 252, McClung,

279 U.S. at 300, that per capita spending by Negroes at

places of public accommodation was significantly lower

than for whites, adversely affecting national commerce,

McClung, 379 U.S. at 299-300, that Negroes with skills

were reluctant to accept employment and move into areas

where there was discrimination in places of public accom

modation, thus adversely affecting national commerce,

13 The Court though relying upon the Commerce Clause in Heart of

Atlanta, supra, and McClung, supra, indicated that there was possibly

additional constitutional authority in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth

Amendments. Heart of Atlanta, 379 U.S. at 250. See also separate

opinions of Justices Goldberg and Douglas, 379 U.S. at 378 and 391.

Appellees in no way abandon this argument. However, it would seem

that since the authority under the commerce clause is so clearly available

that it would be unnecessarily burdensome to set out this alternative

authority.

10

McClung, 379 U.S. at 300 and that commerce has been

adversely affected by the wide unrest caused by discrimi

nation in places of public accommodation. McClung, 379

U.S. at 300.18a Reviewing this testimony presented to

Congress, the Court found that discrimination in restau

rants affected commerce:

“We believe that this testimony afforded ample basis

for the conclusion that established restaurants in such

areas sold less interstate goods because of the discrimi

nation, that interstate travel was obstructed directly

by it, that businesses in general suffered and that many

new businesses refrained from establishing there as a

result of it. . . . ” McClung, 379 U.S. at 300.

The Court, further, had no difficulty in finding support

in its previous decisions for the proposition that many

seemingly local places of public accommodation could be

reached by national legislation where Congress had rea

sonably found, as in this area, that there was a cumulative

effect on commerce. In McClung the Court pointed to the

cases extending from Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat 1, 6 L.Ed

23 (1824) through Consolidated Edison Co. v. Labor Board,

305 U.S. 197, 83 L.Ed. 126, 59 S.Ct. 206 (1938); United

States v. Wrightwood Dairy Co., 315 U.S. 110, 86 L.Ed

726, 62 S.Ct. 523 (1942); Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. I l l ;

87 L.Ed. 122, 63 S.Ct. 82 (1942) and Polish Alliance v.

Labor Board, 322 U.S. 643, 88 L.Ed 1509, 64 S.Ct. 1196

(1944) and said:

“ This Court has held time and again that this power

[the commerce clause] extends to activities of retail

establishments, including restaurants, which directly

13a See also the discussion as to the purpose, coverage and affect on

commerce in Part II of this brief.

11

or indirectly burden or obstruct interstate commerce.”

McClung, 379 U.S. at 301.

In Heart of Atlanta, Mr. Justice Clark, writing for the

Court, exhaustively treated the broad power granted to

Congress by the Commerce Clause. See Section 7, Heart

of Atlanta, 379 U.S. at 254-261. See also Newman v. Piggie

Park Enterprises, Inc., supra.

The defendant here, however, would have this Court

rule, despite the Supreme Court’s very recent analysis of

the legislative history of Title II and the Congressional

power under the Commerce Clause, that because John

Moore primarily engages in a local business he is outside

the purview of Congressional regulation. It should be

sufficient to repeat that his restaurant is located on U. S.

Highways 17 and 70, it has a capacity of approximately

100 persons, it sold $177,000 worth of food in 196614 and

it serves some interstate travelers. The fact that his oper

ation “may be trivial by itself is not enough to remove him

from the scope of federal regulation where, as here, his

contribution, taken together with that of many others simi

larly situated, is far from trivial.” Wickard v. Filburn, 317

U.S. I l l , 127-28; quoted in McClung, 379 U.S. at 301.

Since the Supreme Court had sustained the constitution

ality of Title II upon a rationale which clearly encom

passed Moore’s Barbecue Restaurant, the Court below was

entirely correct in concluding that because the defendant

admitted refusing service to Negroes “ the sole, determin

14 The Supreme Court’s statement, as set out above, that Congress

drew a reasonable conclusion that “ established restaurants in such areas

sold less interstate goods because of racial discrimination” is highlighted

in this case. Defendant very clearly has attempted to refrain from

making interstate purchases to avoid coverage. He thus burdens com

merce not only in limiting his patrons to whites but also in making

commercial decisions as to purchases on a racial basis.

12

ative question for the Court is whether Moore’s Barbecue

Restaurant is an establishment covered by Title II, Sec

tion 201 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” (App. 29)

The Supreme Court had used strikingly similar language

in indicating the duty of federal courts under the Act.

It said that

“where we find that the legislators, in the light of

the facts and testimony before them, have a rational

basis for finding a chosen regulatory scheme necessary

to the protection of commerce, our investigation is at

an end. The only remaining question . . . is whether

the particular restaurant either serves or offers to

serve interstate travelers or serves food, a substan

tial portion of which has moved in interstate com

merce.” McClfyng, 379 U.S. at 304.

II.

The Court Below Was Clearly Correct in Finding That

Defendant’ s Restaurant Is Covered by the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 on the Basis of Defendant’ s Own Admission

That He Did Serve Some Interstate Travelers, and the

Uncontradicted Testimony of Six White Witnesses That

They Had Eaten at the Restaurant and That No Inquiry

Had Been Made of Them as to Their Residency.

Mr. Moore’s restaurant is located on U. S. Highway 17

and 70, has a capacity of up to 100 patrons in the dining

room and parking places for 100 cars. He has placed two

signs in his windows indicating that he does not “ cater

to interstate patrons.” It would seem unlikely that this

would deter many interstate travelers who had come to

his restaurant. Some might not see the sign. Some might

be confused as to its meaning. (What does “cater” mean

13

in this context?) Some might ignore it, not earing to get

back in their ears after having stopped.

And there was ample evidence for the Court below to

conclude that some interstate travelers are served. Mr.

Moore admits that his methods for enforcing his policy

are considerably less than fool-proof.15 16 The testimony of

plaintiffs’ six white witnesses that none were questioned

concerning their places of origin supports Mr. Moore’s

admission. Indeed, in the face of Mr. Moore’s admission

at trial that some interstate travelers were served,16 it

would have been clear error for the Court to have found

otherwise. Therefore, defendant must be arguing here that

occasional service to interstate travelers is not enough to

bring a restaurant within the Act.

The scheme of Title II of the Civil Eights Act is, in its

relevant portions as follows:

42 U.S.C. §2000a(a) forbids discrimination in places of

public accommodations as defined by the Act;

42 U.S.C. §2000a(b) lists and describes those places

covered, including restaurants, subject to the “com

merce” test in Section ( c ) ;

42 U.S.C. §2000(c) sets out commerce tests for the

places of public accommodation as described in Sec

tion (b). The test for a restaurant is whether “ it

15 Direct examination by Mr. Tucker:

Q. Mr. Moore, can you keep out every person who is from out

side North Carolina? A. It is impossible for me to keep everyone

out. (117a)

Cross examination by Mr. Chambers:

Q. Now, you testified in direct examination by Mr. Tucker that it

is impossible for you to keep all the interstate travelers out? A.

Well, I would say so, because I do not know everybody in the world.

(159a)

16 See note 13 supra.

14

serves or offers to serve interstate travelers or a sub

stantial portion of the food which it serves . . . or

other products which it sells has moved in commerce.”

The three tests are in the alternative. Only the third

test—where a “ substantial portion of food . . . has moved

in commerce”— requires a showing of substantiality. De

fendant, apparently would have this Court read such a

requirement into the “serve” test; Congress, however, chose

not to. When Representative Willis sought to amend

42 U.S.C. §2000a-(c) (2) to strike “ it serves or offers to

serve interstate travelers or” and insert in lieu thereof

the following: “a substantial number of the patrons it

serves are interstate travelers and . . . ” (emphasis sup

plied), 110 Cong. Rec. 1901 (Daily Ed., Feb. 5, 1964)

Congressman Celler opposed the amendment:

“ This amendment would change that. Instead of being

in the disjunctive, it would be in the conjunctive, and

the Attorney General would have to prove two things.

First, he would have to prove that in a particular

restaurant the service is to a substantial number of

interstate travelers. Not merely to interstate travelers

but to a ‘substantial’ number of interstate travelers.

And, in addition, he would have to prove that a sub

stantial portion of the food which is served has moved

in interstate commerce. That is a proof that is two

fold, and it makes it all the more difficult for the

Attorney General to establish that proof. It cuts, as it

were, the import of the words ‘affect commerce’, which

are on page 43, line 24, in half. You have this situa

tion, for example. Whereas, in the proposal before

us, many restaurants are within the orbit of the pro

hibition of the bill, many of such restaurants would

not be covered under this amendment. Take, for ex

ample, a roadside restaurant which sells home-grown

15

food which does not come from outside the State. That

would not be covered under the amendment. Further

more, a local restaurant which serves loeal people with

food coming from all over the United States would

not be covered under the amendment. Let me repeat

that.

“ We have very significant results here. Instead of

having all restaurants covered, under this amendment

you would eliminate the restaurant, for example, a

roadside restaurant, that sells home-grown food. You

would also eliminate the local restaurant that serves

local people with food that comes from all over the

country. I do not think we want such a situation to

develop, and for that reason I believe that the whole

purpose of covering restaurants would be defeated by

this amendment” (110 Cong. Rec. 1902 (Daily Ed.

February 5, 1964) at 1902) (emphasis supplied).

The amendment was rejected at p. 1903.

The Court below was clearly correct when it said:

“ [Irrespective of one’s intent to effectively remove

himself from the Act and its prohibitions, he must in

fact and in law not serve interstate travelers if he

shall avoid ‘affecting commerce.’ The reasons for re

quiring a strong showing on such an issue as this

becomes manifest when viewed in light of the strong

congressional policy underlying the purpose of the

Act.” (App. 31)17

17 See also the discussion in Section III infra, setting out the Con

gressional intent of covering all restaurants under Title II.

16

III.

The Court Below Erred in Finding That Defendant

Did Not “ Offer to Serve” Interstate Travelers in That

Its Advertising Contained No Such Disclaimer and Its

Location Would Attract Interstate Travelers; the Court

Also Erred in Finding That “ a Substantial Portion of

Its Food . . . or Other Products” Had Not Moved in

Commerce.

In the event that this Court should rule against plain

tiffs in their contention that the Court below was clearly

correct in finding that defendant served interstate travelers,

the order below should be affirmed on the ground that de

fendant offered to serve interstate travelers, or on the

ground that a substantial portion of defendant’s food or

other products moved in commerce. On these two issues,

the Court below erred.

Relevant to a consideration of both, and also to the

issue as to the meaning of “ serve” 18 is the legislative record

of Title II.

It is clear beyond doubt that key legislators assumed

coverage of virtually all restaurants. In the Senate, Sena

tor Magnuson, Chairman of the Commerce Committee,

presenting an analysis of Title II, said:

“Most public eating places would be within the ambit

of Title II because of their connection with interstate

travelers or interstate commerce. And in some areas,

public eating places would come within the ambit of

Title II, because of the factor of State action.

“At any rate, it is clear that few, if any, proprietors

of restaurants and the like would have any doubt

whether they must comply with the requirements of

18 See also Section II supra.

17

Title I I ” 110 Cong. Rec. 7177 (Daily Ed., Apr. 9,1964)

(emphasis supplied).18

Attorney General Kennedy stated the central purpose of

the Act as follows:

Arbitrary and unjust discrimination in places of

public accommodation insults and inconveniences the

individuals affected, inhibits the mobility of our citi

zens, and artificially burdens the free flow of commerce.

Consider, for instance, the plight of the Negro trav

eler in some areas of the United States.

For a white person, traveling for business or plea

sure ordinarily involves no serious complications. He

either secures a room in advance, or stops for food

and lodging when and where he will.

Not so the Negro traveler. He must either make

elaborate arrangements in advance, if he can, to find

out where he will be accepted, or to subject himself

and his family to repeated humiliation as one place

after another refuses them food and shelter.

He cannot rely on the neon signs proclaiming

“Vacancy,” because too often such signs are meant

only for white people. And the establishments which

will accept him may well be of inferior quality and

located far from his route of travel.

The effects of discrimination in public establish

ments are not limited to the embarrassment and frus

tration suffered by the individuals who are its most

immediate victims. Our whole economy suffers. When

large retail stores or places of amusement, whose

goods have been obtained through interstate com

merce, artificially restrict the market to which these

goods are offered, the Nation’s business is impaired. 19

19 See also Rep. Celler’s remarks concerning the proposed substan

tiality test, II, supra.

18

Business organizations in this country are increas

ingly mobile and interdependent, and they tend to ex

pand beyond the areas of their origins. As they find

it necessary or feasible to engage in regional or na

tional operations, they establish plants and offices in

various parts of the country. These installations

benefit the localities in which they are established

and affect the commerce of the country. Artificial

restrictions on their employees limit this type of

mobility and its benefits to the national economy.

Further, if we add together only a minor portion

of all the discriminatory acts throughout the country

in any one year which deny food and lodging to

Negroes, it is not difficult at all to see how, in the

aggregate, interstate travel and interstate movement

of goods in commerce may be substantially affected.

No matter—in Mr. Justice Jackson’s words— “how

local the operation which applies the squeeze,” com

merce in these circumstances is discouraged, stifled,

and restrained among the States as to provide an ap

propriate basis for congressional action under the

commerce clause.

Mr. Chairman, discrimination in public accommoda

tions not only contradicts our basic concepts of liberty

and equality, but such discrimination interferes with

interstate commerce and the development of unob

structed national market.

We pride ourselves on being a people who are gov

erned by laws. This pride is justified when we pro

vide legal means for the settlement of human differ

ences and the satisfaction of justified complaints.

Mass demonstrations disrupt the community in which

they occur; they also disrupt the country as a whole.

But no one can in good faith deny that the grievances

which these demonstrations protest against are' real.

19

(Hearings before Comm, on the Judiciary, 88th Cong.

1st Sess. Part II, pp. 1374-75.)

This central purpose of the Act—coverage of all res

taurants—was specifically recognized by this Court in

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 377 F.2d 433,

436 (4th Cir. 1967) where the Court said:

“We think the Congress plainly meant to include

within the coverage of the Act all restaurants, cafe

terias, lunchrooms, lunch counters, soda fountains, and

all other facilities primarily engaged as a main part

of their business in selling food for consumption on

the premises. We are further of the opinion that the

statutory language accomplished that purpose.”

See also Gregory v. Meyer, 376 F.2d 509 (5th Cir. 1967).

The rather ambiguous disclaimer of defendant’s signs

and his erratic questioning of customers does not mean

that he does not offer to serve interstate travelers. The

restaurant advertises to the public at large and is located

on an interstate highway. In Newman, supra, this Court

was very clear in holding that any restaurant on an inter

state highway offers to serve interstate travelers:

“If the ‘commerce’ tests are the principal criteria, and

we think they are, clarity of coverage is promoted. A

traveler can then intelligently assume that an eating

place on an interstate highway is covered.” Newman,

supra, at 435.

In the light of this language it seems unlikely that Moore

could remove himself from the Act. At any rate, what he

has done is certainly not enough.

It is also clear that a substantial portion of defendant’s

food had moved in commerce. In Gregory, the 5th Circuit

20

noted that the legislative history indicates that “ substan

tial” as used here means “ anything more than a minimal

amount. Hearings on S. 1732 before the Senate Committee

on Commerce, S.Bep. No. 872, 88th Cong., 2d Sess., pp.

1717-173, 212, 220.” Gregory at 511.

The defendant admits that approximately $4,000 worth

of goods were purchased in both 1963 and 1964 from out

of state and approximately $2,700 was so purchased in

1966. We maintain that this alone meets the substantiality

test. There were additional out of state products purchased

by the defendant from North Carolina firms;20 the Dis

trict Court failed to consider these items in its opinion.

This was clearly erroneous. Katsenbach v. McClung, supra,

and Gregory v. Meyer, supra.

In light of the legislative history of the Act and the evi

dence before the Court below, it was error for the Court

not to find that a substantial portion of defendant’s food

had moved in commerce.

20 See note 7 supra.

21

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the order below should be affirmed.

of Counsel:

Respectfully submitted,

J. L eV onne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Conrad 0. P earson

2031/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J ack Greenberg

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellees

James E. F erguson, II

MEIIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C .=*^^»219