Response of Defendants to the Motions to Consolidate Appeals, to Designate Parties and to Fix Time for the Filing of the Appendix and Brief of Defendants

Public Court Documents

February 10, 1972

6 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Response of Defendants to the Motions to Consolidate Appeals, to Designate Parties and to Fix Time for the Filing of the Appendix and Brief of Defendants, 1972. ab3035c3-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b2a39c3-1cb5-4a5d-8a44-3ab8823a9bf7/response-of-defendants-to-the-motions-to-consolidate-appeals-to-designate-parties-and-to-fix-time-for-the-filing-of-the-appendix-and-brief-of-defendants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

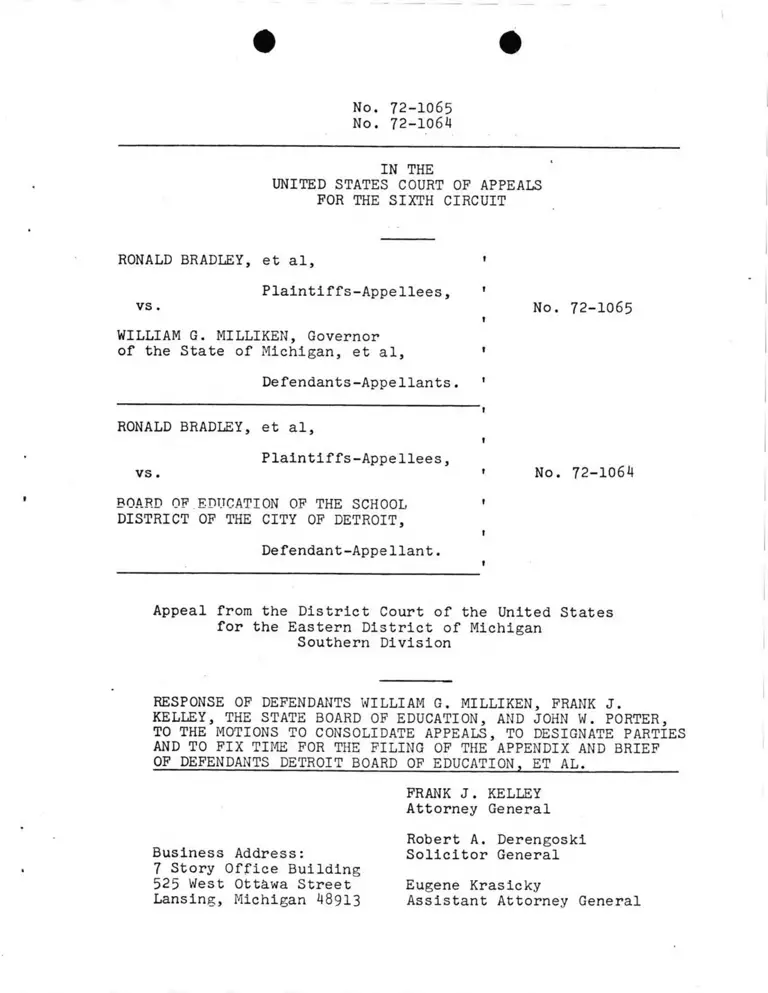

No. 72-1065

No. 72-1064

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RONALD BRADLEY, et al, f

vs .

Plaintiffs-Appellees, f

f

No. 72-1065

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, Governor

of the State of Michigan, et al, t

Defendants-Appellants. f

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

f

V

vs .

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

f No. 72-1064

BOARD OF

DISTRICT

EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL

OF THE CITY OF DETROIT,

Defendant-Appellant.

Appeal from the District Court of the United States

for the Eastern District of Michigan

Southern Division

RESPONSE OF DEFENDANTS WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, FRANK J.

KELLEY, THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, AND JOHN W. PORTER,

TO THE MOTIONS TO CONSOLIDATE APPEALS, TO DESIGNATE PARTIES

AND TO FIX TIME FOR THE FILING OF THE APPENDIX AND BRIEF

OF DEFENDANTS DETROIT BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.__________

Business Address:

7 Story Office Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

Eugene Krasicky

Assistant Attorney General

I

THE MOTIONS TO CONSOLIDATE AND TO DESIGNATE

PARTIES AS APPELLANT AND APPELLEE SHOULD BE

DENIED.____________________________________

A. The Motion to Consolidate

The state defendants cannot see what there is to

consolidate. Although the appeals are docketed separately,

this is one case on appeal. Sixth Circuit Rule 7(2) applies

to companion cases, not to a single case.

B. The Motion to Designate Parties as

Appellant and Appellee.___________

This motion is the second attempt by a party to

this appeal to change, without any cogent reason, the practice

established by the rules of appellate procedure.

PR App P, 28(h) makes the plaintiff in the lower

court the appellant for purposes of briefs and appendix when

a cross appeal is filed, unless the parties otherwise agree or

the court otherwise orders. The parties have not otherwise

agreed. Is there any substance in'the defendant Detroit Board's

claim that the court should otherwise order? Obviously the

answer is "no."

Defendant Detroit Board's claims in this regard are

found in paragraphs 5 and 6 of page 3 of its motion. The first

-1-

claim, in substance, is that the issue upon which plaintiffs

have cross appealed "almost" does not affect the state defendants.

There are two answers: (1) Since this issue does affect the

defendant Detroit Board, "almost solely," it is properly

designated an appellee; (2) if the state defendants do not

object to being designated as appellee on this issue, why should

the defendant Detroit Board complain?

The second claim (paragraph 6 of the motion), in

substance, is that the significant issue, in terms of trial time

and briefing, and in terms of its importance to the parties and

the community, is the issue of student segregation, the decision

on which all defendants appeal. Consequently, the defendants

should be the moving party on the appeal and should have the

opportunity to present their case first. There are two defects

in this claim: (1) the Confederate calvary's motto should have

no application to this appellate review of a chancery case; this

is not a jury trial. (2) Whether this Court first hears the

"vast majority and substance" of this issue in appelleefs brief

(assuming this is correct) rather than in appellant's brief does

not appear to make any difference. The state defendants are

confident that this Court will render its decision on the basis

of its consideration of no less than all the briefs and all of

the arguments.

-2-

Manifestly, the court rule was designed to

accommodate the case where a defendant appeals and a plaintiff

cross appeals. This is the situation here. If the Court feels

that the rule should be changed in this case to accommodate the

Court, the state defendants can have no objection. But the

state defendants do say that no sound reason has been given

to modify the rules to accommodate the strategy of one of the

parties.

II.

THE MOTION TO FIX TIME FOR THE FILING OF

APPENDIX AND BRIEFS SHOULD BE GRANTED.

The state defendants concur with the defendant

Detroit Board of Education in this motion. In view of tbp

fact that none of the defendants have sought a stay of the

District Court's order it cannot be said that the motion is

brought for purpose of delay. Because of the volume and

complexity of the proceedings, the purely physical aspects of

printing the record require the additional time. This will

be true regardless of whether the plaintiffs or the defendants

are ultimately the appellant, and in this regard the state

defendants reiterate their position that the plaintiffs should

be the appellant as provided by the appellate rules.

Since the defendants will not know, prior to the

Court's decision on plaintiffs' motion to dismiss, whether there

-3-

is in fact an appeal, it is certainly in the interest of

economy of both time and money not to commence the printing

process until this threshold issue is decided.

Again, because no stays have been sought, there

can be no claim that the motion was filed for purposes of

delay.

CONCLUSION

The motion to designate parties as appellant and

appellee should be denied because there are no substantial

reasons for deviating from the court rules. This case is no

different from any other in this regard, and the court rules

clearly establish a workable procedure.

The motion to fix time for the filing of appendix

and briefs should be granted because (1) the expense of printing

should not be incurred prior to the parties knowing that there

will be an appeal, (2) the physical impossibility of printing

the appendix in less than 90 days, and (3) the extention of time

is not sought for purpose of delay, there being no stay of

proceedings in the trial court.

Dated: Fe truary 10, 1972

Business Address:

7 Story Office Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Respectfully submitted,

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor GeneralA „ w A -,

Eugene Krasicky

George L. McCargar

Gerald F. Young

Assistant Attorneys General

-4-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that a true copy of the foregoing

response to the motions to consolidate appeals, to designate

parties and to fix time for the filing of the appendix and

brief of defendants Detroit Board of Education, et al, was

served upon the following named addressees this 10th day of

February, 1972 by United States mail, postage prepaid, addressed

to them at their respective business addresses:

Messrs. Louis R. Lucas and

William E. Caldwell

Mr. Nathaniel R. Jones

Messrs. J. Harold Flannery,

Paul R. Dimond and

Robert Pressman

Mr. E. Winther McCroom

Messrs. Jack Greenberg and

Norman J. Chachkin

Mr. George T. Roumell, Jr.

Mr. Theodore Sachs

Mr. Alexander B. Ritchie

Assistant Attorney general

Dated: February 10, 1972