Carson v. American Brands, Inc. Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carson v. American Brands, Inc. Brief for Petitioners, 1980. 7791d8fa-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b2b59f2-7abb-4836-9313-90338d421623/carson-v-american-brands-inc-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

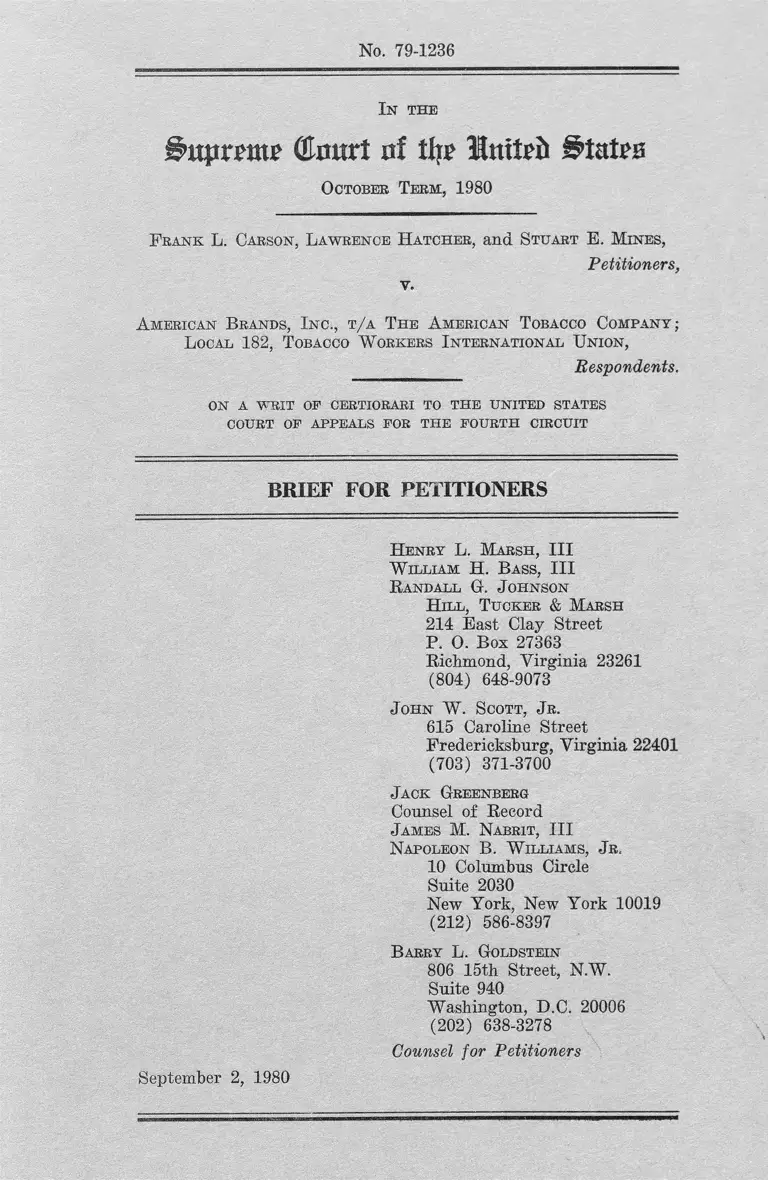

No. 79-1236

In t h e

Bupnmv (tart uf % llmtib States

October Term, 1980

F rank L. Carson, L awrence H atcher, and Stuart E. M ines,

P etition ers,

v.

A merican Brands, I nc ., t/a T he A merican Tobacco Co m pany ;

L ocal 182, T obacco W orkers I nternational Union ,

______ R espondents.

ON A WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OP APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

H enry L. Marsh , I I I

W illiam H. Bass, I I I

Randall G. Johnson

H ill , T ucker & Marsh

214 East Clay Street

P. 0. Box 27363

Richmond, Virginia 23261

(804) 648-9073

John W. Scott, Jr.

615 Caroline Street

Fredericksburg, Virginia 22401

(703) 371-3700

Jack Greenberg

Counsel of Record

James M. Nabrit, I I I

N apoleon B. W illiams, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Barry L. Goldstein

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 638-3278

Counsel fo r P etitioners

September 2, 1980

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

C i r c u i t e r r ed in h o ld in g that an o rde r o f the

d i s t r i c t court, which refused to enter a j o i n t l y

proposed consent d ecree on the grounds o f i t s

a l leged i l l e g a l i t y , was not appealable under 28

U.S.C. §1291 as a c o l l a t e r a l order pursuant to

the C o u r t ' s d e c i s i o n in Cohen v . Bene f i c i a l

I n d u s t r i a l Loan C orp . , 377 U.S. 541 (1949 )?

2. Whether th ere was e r r o r in the Fourth

C i r c u i t ' s h o ld in g th a t the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s

order, which denied approval to a proposed consent

decree g ra n t in g a permanent in ju n c t i o n on the

ground o f the decree 's a l leged i l l e g a l i t y , was

not a p p ea lab le under 28 U.S.C. § 1 2 9 2 ( a ) ( l ) as

an in ter locu tory order re fus ing an injunction?

l

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED. . .................. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................................. iv

CITATION TO OPINION BELOW. . . . . . ...... ............. . 1

JURISDICTION............................................................ 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED... . ....... .................. 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE. ............ 5

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT........ .................... 21

A. Appea lab i l i ty Under §1291............. 21

B. Appea lab i l i ty Under §1292 (a ) ( 1 ) . . . . 22

ARGUMENT........................................................ 22

1. INTRODUCTION. ........................................... 23

2. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER RE

FUSING TO APPROVE THE PARTIES'

JOINTLY PRESENTED CONSENT ORDER

WAS A COLLATERAL ORDER WHICH WAS

APPEALABLE AS AN EXCEPTION TO

THE FINAL JUDGMENT REQUIREMENT

OF 28 U.S.C. §1291. . ................. 25

A. General.................... ........................... 25

B. The Applicable L a w . . . . . . . .......... .. 27

C. App l icat ion of the Cohen

C r i t e r i a . ............................. 30

Page

3. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER

BELOW IS APPEALABLE UNDER

28 U.S.C. 11292(a)(1) AS AN

INTERLOCUTORY ORDER DENYING

AN INJUNCTION....................................... 44

A. The Appl icab le Law....................... 44

B. C r i t e r ia Governing The

App l icat ion o f § 1 2 9 2 (a ) ( l ) ........... 47

1. General ...................................... 47

2. In ter locutory Order.............. 48

3. In junct ive R e l i e f .............. 49

4. Character is t ics o f an

Injunction. ............................... 55

a. More Than a Mere

P r e - t r i a l Order.............. 55

b. Determining the

M er i ts ................................ 56

5. I rreparab le In ju ry ................ 61

C. App l icat ion of the C r i t e r i a

Under § 1 2 9 2 (a ) ( l ) .......................... 61

CONCLUSION.............................................. 76

i l l

Table o f Author i t ies

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver C o . ,

415 U.S. 36 (1974)...................... ...............24,26,35,75

Baltimore Contractors v. Bodinger,

348 U.S. 176 (1955)...... .............................46,47,49,55

Brown v. Chote,

411 U.S. 542 (1973) .......... ......................... 43

Gatl in v. United States,

370 U.S. 294 (1962)........ 27

Chappell & Co. v. Frankel,

367 F . 2d 197 (2d Cir . 1966).............. . 57,65

Cohen v. Bene f ic ia l Loan Corp . ,

377 U.S. 541 ( 1 9 4 9 ) . . . . .............................. 20,23,25,28

30,47

Cobbledick v. United States,

309 U.S. 323 ( 1 9 4 9 ) . . . . . . . . . ............... 27,28

Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay,

437 U.S. 463 ( 1 9 7 8 ) . . . . . . . . ...................... 35,36,71

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry Co.

406 F . 2d 399 (5th Cir . 1969).................. 35

Dickinson v. Petroleum Conversion Corp.

338 U.S. 507 (1950) ............ 28,30,40

Eisen v. C a r l i s l e & Jacquelin,

417 U.S. 156 (1974)........... 30,40,41

Enelow v. New York L i f e Ins. Co . ,

293 U.S. 379 (1935)........ 45

Cases Page

- iv -

Cases V Page

Ette lson v. Metropol itan L i f e Ins. Co.

317 U.S. 188 (1942) .................................... 45

Franks v. Bowman Transportat ion C o . ,

424 U.S. 747 (1978)................ ................... 11

Gardner v. Westinghouse Broad

casting Co.

437 U.S. 478 (1978)......................................35,40,46,48

56,59,66,68

69

General E l e c t r i c Co. v. Marvel Rare

Metals C o . ,

287 U.S. 430 (1932)..................................... 56,65

George v. V ic tor Talking Machine Co.,

293 U.S. 377 (1934)..................................... 50

G i l l e sp i e v. U.S. Stee l Corp . ,

379 U.S. 148 (1948).................................... 40

Goldstein v. Cox,

396 U.S. 471 (1970)..................................... 51,52

L iber ty Mutual Ins. Co. v. Wetzel,

424 U.S. 737 (1976)..................................... 68

Maxwell v. Enterprise Wall Paper Co. ,

131 F2d 400 (3rd Cir. 1942 ) . .............. .. 46

Mercanti le National Bank at Dallas v.

Langdeau,

371 U.S. 555 (1963)..................................... 30

Morgens tern Chemical Co. Inc. v.

Schering Corp. ,

181 F . 2d 160 (3rd C ir . 1950)........................ 46,57,65

v

Cases Page

Morgantown v. Royal Ins. Co.,

337 U.S. 254 (1949) ........ ........................... 45,49

Norman v. McKee,

431 F .2d 769 (9th Cir . 1970),

ce r t , denied, IS I v. Myers,

401 U.S. 912 ( 1 9 7 1 ) . . .............. .................20,30,39,43

73

Osborne v. Missouri P.R. Co.,

147 U.S. 248 (1893) .................................. .. 43

Peter Pan Fabrics, Inc. v. Dixon

T e x t i l e Corp . ,

280 F .2d 805 (2d Cir . I 9 6 0 ) . . . ............ . 55

Radio Stat ion WOW, Inc. v.Johnson,

326 U.S. 120 (1945). .............................. .. . 27

Russel l v. American Tobacco Company,

528 F .2d 357 (4th Cir. 1975),

cer t , denied, 425 U.S. 935 (1976)........ 8,16

Safe F l i gh t Instrument Corp. v.

McDonnel-Douglas Corp. ,

482 F .2d 1086 (9th Cir . ) ,

c e r t . denied, 414U.S . 1 1 3 . . . . . ............ 59

Sampson v. Murray,

416 U.S. 61 (1974).............. ........................ 61,65

Se ige l v. Merrick,

590 F . 2d 35 (2d Cir . 1 9 7 8 ) . . ...... ...........19,37,38,39

69,70,73

Shanferoke Coal & Supply Corp. v.

Westchester Serv ice Corp . ,

293 U.S. 449 ( 1 9 3 5 ) . . . . ........ ................... 49

vi -

Gases Page

Smith v. Vulcan Iron Works,

165 U.S. 518 (1897).................................. .24,52,53,55

Stewart-Warner Corp. v. Westinghouse

Elec. Corp. ,

325 F .2d 822 (2d Cir . 1963),

ce r t , denied, 376 U.S. 11........ .............. . 44,46,60

Switzerland Cheese Association,

Inc. v. E. Horne's Market, Inc . ,

385 U.S. 23 (1966) .................................... .24,45,47,48

50,55,56,59

66,68

Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977) .................................. 31,66

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum

Industr ies , Inc . ,

517 F .2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975)................ 35

United States v. American Friends

Service Committee,

419 U.S. 7 (1974)................................ .. . . 43

U.S. v. City o f Alexandria,

F . 2d (5th Cir. ),

22 EPD K30, 828, Ap r i l 10, 1980.......... 26

United States v. City o f Miami,

F .2d (5th Cir. ) ,

7 7 EPDT30,821, Apr i l 10, 1 9 8 0 . . . . . . . 26

United Steelworkers o f America,

AFL-CIO-CLC v. Weber,

443 U.S. 193, 61 L.Ed. 2d 480 (1979). .21,22,31,32

34,35,36,41

67,74,75,76

- v i i -

Cases Page

V irg in ia Petroleum Jobbers Assn. v.

FPC,

259 F .2d 921 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 5 8 ) . . . . ........ 61

Weber v. United Steelworkers of

America, AFL-CIO,

563 F .2d 216 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 7 ) . . . . . . . . . . ’ 22

W.L. Gore & Assoc ia tes , Inc. v.

C a r l i s l e Corp . ,

529 F . 2d 614 (3rd Cir. 1 9 7 6 ) . . . . . _____ 52

Const itut ional Provis ions

F i f th Amendment to the Consti tution o f

the United S t a t e s . ....................................... 2, 7

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1 2 5 4 ( 1 ) . . . . . . . ____ 2

28 U.S.C. §1253 . ........................ . 50,51,52

28 U.S.C. §1291 . . . . . . . . ___ 2,19,21,23,24

25,27,28,29,31,39

28 U.S.C. 81292 (a ) (1 ) ................. 2,19,20,21

22,23,24,27,44,45

46,47,49,50,52,55

56,58,61,63,67,70

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 . . . . . . . . . . ____ 6

Evarts Act o f 1891,

26 Stat. 8 2 6 . . . . . . . . . . . .......... .. 44,53,54

- viii -

Statutes Page

T i t l e V I I , C i v i l Rights Act

o f 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§ §2000e et seq ...................... . . . . 3 ,6 ,7 ,1 7 ,2 5

26,30,31,32,35

39,64,65,66,67

Rules

Rule 23 (e ) , Federal Rules o f

C i v i l Procedure............................ 5,13,23,25

30,36*38

Rule 41 (c ) , Federal Rules o f

C i v i l Procedure.................... 34

Rule 68, Federal Rules o f

C i v i l Procedure.................... 34

L e g i s l a t i v e History

Remarks o f Senator Hubert

Humphrey, 110 Cong. R ec . ,

6548, concerning T i t l e V I I

C i v i l Rights Act o f 1964,

as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§§2000e et seq .............................. 74

Other Author i t ies

Note, Appea lab i l i ty in the

Federal Courts,

75 Harv. L. Rev. 351 (1952 ) . . . 45

Wright & M i l l e r , Federal

Pract ice and ProcedureT . .......... 45,48,52

Abbreviated Form

References to "Joint Appendix below" are

to the Joint Appendix f i l e d in the Court o f

Appeals fo r the Fourth C ircu i t .

IX

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1980

No. 79-1236

FRANK L. CARSON, LAWRENCE HATCHER,

and STUART E. MINES,

Pe t i t i on e rs ,

v.

AMERICAN BRANDS, INC., T/A THE

AMERICAN TOBACCO COMPANY; LOCAL 182,

TOBACCO WORKERS INTERNATIONAL,

TOBACCO WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION,

Respondents.

ON A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

CITATION TO OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Court o f Appeals fo r the

Fourth C ircu i t is reported at 606 F .2d 420. The

opinion and judgment o f the Court o f Appeals are

set forth in the Appendix to the P e t i t i o n for a

Writ of C e r t io ra r i , pp. la , 52a. The opinion o f

the D i s t r i c t Court for the Eastern D i s t r i c t of

V i r g i n i a i s r ep o r t e d at 446 F.Supp. 790. The

opinion and judgment o f the D i s t r i c t Court are

a lso set for th in the Appendix to the P e t i t i o n for

a Writ of C e r t io ra r i , pp. 28a, 51a. .

- 2 -

JURISDICTION

J u r isd ic t io n o f th is Court is invoked pur

suant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1). The judgment o f the

Court o f Appeals d ismissing the appeal was entered

on September 14, 1979. On June 16, 1980, th is

Court g ra n ted the p e t i t i o n f o r a w r i t o f c e r

t i o r a r i l im it ed to Question 1 presented by the

p e t i t i o n . On Ju ly 24, 1980, the C l e r k o f the

Supreme Court granted p e t i t i o n e r s , pursuant to

request , u n t i l September 2, 1980 in which to f i l e

a b r i e f .

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case invo lves the F i f t h Amendment to the

Const i tut ion o f the United States.

This case a lso invo lves the f o l l o w in g f ede ra l

s t a tu t e s :

a. 28 U.S.C. §1291

The cou r t o f appea ls s h a l l have

ju r i s d i c t i o n o f appeals from a l l f i n a l

dec is ions o f the d i s t r i c t courts o f the

United States , the United States D is

t r i c t Court f o r the D i s t r i c t o f the

Canal Zone, the D i s t r i c t Court o f Guam,

and the D i s t r i c t Court o f the V i r g i n

Is lands, except where a d i r e c t rev iew

may be had in the Supreme Court.

b. 28 U.S.C. §1292(a)

The c o u r t o f appea ls s h a l l have

ju r i s d i c t i o n o f appeals from:

(1 ) In te r lo cu to ry orders o f the

d i s t r i c t courts o f the United States ,

3

the United States D i s t r i c t Court f o r the

D i s t r i c t o f the Canal Zone, the D i s t r i c t

Court o f Guam, and the D i s t r i c t Court of

the V i r g i n I s l a n d s , or o f the judges

thereo f , grant ing , continuing, modify

ing, re fus ing or d is so lv ing in junct ions,

o r r e f u s i n g t o d i s s o l v e o r m o d i f y

i n j u n c t i o n s , e x c ep t where a d i r e c t

rev iew may be had in the Supreme Court.

c. 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2

(a ) I t sha l l be an unlawful employment

p ra c t i c e fo r an employer—

(1 ) to f a i l or re fuse to h ire or

to discharge any ind iv idua l , or o ther

wise to d iscr im inate against any i n d i v i

dual with respect to h is compensation,

terms, c o n d i t i o n s , o r p r i v i l e g e s o f

employment, because o f such in d iv id u a l ' s

race, co lo r , r e l i g i o n , sex, or nat ional

o r i g in ; or

( 2 ) t o l i m i t , s e g r e g a t e , o r

c l a s s i f y h is employees or applicants f o r

em p loym ent in any way wh ich w ou ld

depr ive or tend to depr ive any i n d i v i

dual o f employment o p p o r t u n i t i e s or

otherwise adverse ly a f f e c t h is status as

an employee , because o f such i n d i v i

dua l 's race, c o lo r , r e l i g i o n , sex, or

nat ional o r i g in .

- 4 -

( c ) I t sha l l be an unlawful employment

p r a c t i c e f o r a l a b o r o r g a n i z a t i o n - -

( 1 ) t o exc lude o r to e x p e l

from i t s membership, or otherwise

t o d i s c r i m i n a t e a g a i n s t , any

i n d i v i d u a l because o f h i s r a ce ,

c o lo r , r e l i g i o n , sex, or nat ional

o r i g in ;

(2 ) to l im i t , segregate , or

c l a s s i f y i t s membership or a p p l i

cants f o r membership, or to c la s

s i f y or f a i l or re fuse fb r e f e r for

employment any ind iv idua l , in any

way which would depr ive or tend to

depr ive any ind iv idua l o f employ

ment oppor tun i t ies , or would l im i t

such em p loym ent o p p o r t u n i t i e s

or otherwise adverse ly a f f e c t h is

s t a tu s as an employee or as an

appl icant f o r employment, because

o f such in d iv id u a l ' s race, co lo r ,

r e l i g i o n , sex, or na t iona l o r i g in ;

or

( 3 ) to cause or a t tempt to

cause an employer to d iscr iminate

against an ind iv idua l in v i o l a t i o n

o f th is sect ion.

( j ) N o th ing c o n ta in ed in t h i s sub

chapter sha l l be in terp re ted to require

any employer, employment agency, labor

organ iza t ion , or j o in t labor-management

committee subject to th is subchapter to

g ran t p r e f e r e n t i a l t r ea tm en t to any

ind iv idua l or to any group because o f

the r a c e , c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , sex , or

na t iona l o r i g in o f such ind iv idua l or

group on account o f an imbalance which

may e x i s t w i th r e s p e c t to the t o t a l

number or percentage o f persons o f any

race, c o lo r , r e l i g i o n , sex, or nat ional

o r i g i n e m p lo y e d by any e m p l o y e r ,

r e f e r r ed or c l a s s i f i e d f o r employment by

any employment agency or labor organiza

t ion , admitted to membership or c la s

s i f i e d by any l a b o r o r g a n i z a t i o n ,

o r adm it ted t o , o r employed in , any

apprenticeship or other t ra in ing pro

gram, in comparison w i th the t o t a l

number or percentage o f persons o f such

race, co lo r , r e l i g i o n , sex, or nat ional

o r i g in in any community, State , sec t ion ,

or other area, or in the a va i lab le work

fo rce in any community, State , sect ion ,

or other area.

d . Rule 2 3 ( e ) , Federal Rules o f C i v i l Pro-

cedure

- 5 -

A c lass act ion sha l l not be d i s

m is s e d o r com prom ised w i t h o u t th e

approval o f the court, and no t ice o f the

proposed d i s m is s a l s h a l l be g i v e n to

a l l members o f the c lass in such manner

as the court d i r e c t s .

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

General . On October 24, 1975, p e t i t i o n e rs ,

p re s en t and fo rm er seasona l employees at the

Richmond Leaf Department o f the American Tobacco

Company, a subsidiary o f American Brands, In c . ,

which is located in Richmond, V i r g in ia , f i l e d a

complaint on beha l f o f themselves and other black

employees at the Richmond Leaf Department.

The complaint charged that defendant Ameri

can Brands, I n c . , d e fen dan t Tobacco W orkers '

In te rna t iona l Union, and defendant Local 182 o f

the Tobacco W o rke rs ' I n t e r n a t i o n a l Union, in

v i o l a t i o n o f the C i v i l R ig h ts Ac t o f 1964, 42

U .S .C . § §2000e, e t s e q . , and 42 U.S.C §1981,

d i s c r i m i n a t o r i l y d en ied b la ck workers h i r i n g ,

promotion, and t ran s fe r opportun it ies and d i s -

c r i m i n a t o r i l y r e s t r i c t e d b la ck workers to low

paying and otherwise undesirab le jobs.

A f t e r the conduct o f extens ive d iscovery , the

d i s t r i c t c o u r t , on March 1, 1977, c e r t i f i e d a

c lass cons is t ing o f (1 ) black persons, current ly

and formerly employed who were seasonal employees

o f the American Tobacco Company's Richmond Leaf

Department on or a f t e r September 9, 1972, and (2 )

black persons who applied f o r seasonal employment

at the American Tobacco Company's Richmond Lea f

Plant on or a f t e r September 9, 1972.

The pa r t i e s reached a settlement o f p la in

t i f f s ' claims, entered into a proposed consent

decree, Joint Appendix 24, and j o i n t l y moved for

- 6 -

7

approval and entry o f the proposed decree. The

d i s t r i c t court denied the motion on the ground

that the proposed decree v i o l a t e d the prov is ions

o f T i t l e V I I o f the C i v i l Rights Act o f 1964, as

amended, 42 U .S.C . §§2000e e t seq. . in th a t i t

provided, in the absence o f proof that defendants

had engaged in r a c i a l l y d iscr im inatory actions or

that p l a i n t i f f s and c lass members were v ic tims o f

r a c ia l d iscr im inat ion by defendants, f o r p re fe ren

t i a l treatment o f black employees on the basis of

race and co lo r . 446 F.Supp. at 788-791.

A d d i t i o n a l l y , i t h e ld th a t both T i t l e V I I

and the F i f t h Amendment to the Const i tut ion o f the

U n ited S t a t e s p rec luded a d i s t r i c t c ou r t from

plac ing what i t termed a " f e d e r a l stamp o f appro

v a l " upon an agreement which provided p r e f e r e n t ia l

t r ea tm en t on the ba is o f r a c e or c o l o r in the

absence o f proo f o f d iscr im inat ion by defendant

and in the absence o f proof that p l a i n t i f f and

c l a s s members were v i c t im s o f d i s c r i m in a t i o n .

446 F.Supp. at 784

On May 14, 1979, the United States Court o f

Appeals f o r the Fourth C ircu i t ordered the merits

o f the appea l to be de te rm ined ejn banc . On

September 14, 1979, however, the Court o f Appeals

ordered the appeal dismissed on the ground that

- 8 -

the order appealed from below was not appealable

w i t h i n the intendment o f 28 U .S .C . §§1291 and

V

1292. Chief Judge Haynsworth and C ircu i t Judges

Winter and Butzner d issented in an opinion ho ld ing

that the order was appealable and that the consent

decree should have been approved.

His tory o f Rac ia l D iscr im inat ion . American

Brands, In c . , employs 150 seasonal employees and

100 regu lar , or f u l l - t im e , employees to process

and s t o r e l e a f t o ba cco at the Richmond L e a f

Department o f the American Tobacco Company in

Richmond, V i r g in i a .— The seasonal employees, a l l

o f whom are b l a c k , work between s i x and n ine

months dur ing the y ea r . By c o n t r a s t , r e g u l a r

employees, o f whom 34% are white , work throughout

u 2/

the y ea r .— Both the seasonal and regular

1J The fa c ts concerning employment s t a t i s t i c s o f

defendant American Brands, Inc. are contained in

that defendant 's answer to p l a i n t i f f s ' i n t e r r o

ga to r i e s , r e levant portions o f which are included

in the Record below as the p a r t i e s ' Joint Appendix,

and are a l s o c o n ta in e d in the op in ion s be low .

Moreover, the operat ion o f the American Tobacco

Co. is descr ibed in Russell v. American Tobacco

Co■ , 528 F . 2d 357 (4th C i r . 1975), c e r t . denied,

425 U.S. 935 (1976).

2/ The fo l l o w in g tab le represents the r a c ia l

c om p os i t i on o f the employees a t the Richmond

Leaf Department from 1968-1976:

employees are represented by defendant Local 182,

Tobacco Workers' In ternat ional Union (her ina f te r

"T .W . I .U . " ) .

P r io r to September 16, 1963, union ju r i s d i c

t i o n ove r job p o s i t i o n s at the Richmond L ea f

Department was div ided betweeen Local 182 o f the

T .W . I .U . and L oca l 214 o f the T .W . I .U . The

former, whose membership was then a l l white, had

exc lus ive ju r i s d i c t i o n over regular job c lass

i f i c a t i o n s . Local 214's membership was l imited

to black employees who were seasonal workers at

3/

the Richmond Leaf Department.—

While the exis tence of two separate unions at

the Department was o f f i c i a l l y te rm inated on

September 16, 1963, the p re -ex is t ing patterns o f

- 9 -

2/ (con 'd )

Year Regular Employees Seasonal Employees

1968

Whites

4 1

Blacks

5 2

Whites

0

Blacks

~TT5

1970 40 59 0 175

1973 40 56 0 176

1976 37 57 0 135

See defendant American Brand' s answer

Tnterrogatory #14 in Joint Appendix below.

- 10

r a c i a l d i s c r i m in a t i o n , however , c on t inu ed in

e f f e c t at the Richmond L e a f Department as a

consequence o f regu la t ions and procedures estab

l i s h i n g the system o f s e n i o r i t y and t r a n s f e r

r igh ts o f employees.

4/

Sen io r i ty and Transfer R igh ts .— P r io r to

September 16, 1963, permanent job vacancies were

f i l l e d by c a n va ss in g the employees w i t h in the

bargain ing unit o f the union having ju r i s d i c t i o n

o f the jobs in which the v a c a n c ie s e x i s t e d .

This procedure b en e f i t t ed the white members o f

Local 182 in the compet it ion fo r permanent job

p o s i t i o n s .

F o l l o w in g the 1963 merger o f the l o c a l s ,

the rules governing the f i l l i n g o f vacancies in

the fu l l - t im e pos i t ions continued to exclude or

d is a d va n ta g e the b la ck workers who had been

d is c r im in a to r i l y assigned to seasonal pos i t ions .

When management r e q u e s t s a job t r a n s f e r o f a

r e g u l a r employee tha t employee does not l o s e

s e n io r i t y r i g h ts , but when management requests a

4/ See defendant American Brand's answers to

In te r ro ga to r i e s #20-56 in Joint Appendix below.

11 -

seasonal employee t̂ o t ran s fe r to fu l l - t im e work

that employee loses his s e n io r i t y r i gh ts .

M oreove r , when a r e g u l a r worker t r a n s f e r s

from one fu l l - t im e job to another one the employee

reta ins a l l o f h is s e n io r i t y r i g h ts , but when a

seasonal worker t rans fe rs to a fu l l - t im e job he

5/

lo s e s a l l o f h i s s e n i o r i t y r i g h t s . - F u r t h e r

more, a seasonal worker who transfers to a f u l l

t ime p o s i t i o n a lmost always must e n t e r at a

bot tom - leve l p os i t ion because the regular workers

have the f i r s t opportunity to move to the vacan

c ies in fu l l - t im e pos i t ions .

Accord ing ly , i f a seasonal worker is employed

in a seasonal pos i t i o n above the e n t r y - l e v e l , he

f requent ly w i l l be required to su f f e r a short-term

pay cut in order to move in to a fu l l - t im e pos i t ion .

The imposit ion o f these p ena l t ies , the loss o f

s e n io r i t y and the poss ib le reduction in short-term

pay, serve to lock in the e f f e c t s o f the h i s t o r i c a l

5/ The t ran s fe r r in g seasonal worker loses not

only his "com pet i t i v e " s e n io r i t y r i gh ts , e . g .,

r igh ts fo r job secu r i ty and promotion, but also

his " b e n e f i t " s e n io r i t y r i gh ts , e . g . , r i gh t fo r

sick leave and vacat ion, except for retirement

bene f i t s . Cf. Franks v. Bowman Transportat ion

Co., 424 U.S. 747, 765 (1976T.

- 12 -

d i s c r i m in a t o r y p r a c t i c e s which e x i s t e d at the

Richmond L e a f D i v i s i o n . These p r a c t i c e s were

responsib le , as o f February 13, 1976 f o r c reat ion

o f a s i tu a t ion in which only one o f the 16 p os i -

6 /

t ions o f watchman was held by a black employee.™

The h i s t o r i c a l p rac t ices o f d iscr im inat ion

have continued to l im i t the employment opportuni

t i e s o f b la ck workers f o r s u p e r v i s o r y as w e l l

as h o u r ly j o b s . A lmost in v a r a b l y the Company

s e lec ts i t s superv isory employees from i t s f u l l

t ime s t a f f . The Company has n e v e r promoted a

seasonal worker d i r e c t l y to a superv isory pos i

t ion . The cont inuat ion o f the e f f e c t s o f the past

segrega t ive p rac t ices has resu lted in the s e l e c

t ion o f a d isp ropo r t iona te ly small group o f the

Company's b la ck employees as s u p e r v i s o r s . As

o f A p r i l , 1976, only 20% o f these pos i t ions were

f i l l e d by b lacks.—^

6/ See de fendant American Brand 's answer to

In te r roga tory #15(c) continued in Joint Appendix

be low.

7/ Id. In te r roga tory #65.

13

Proposed Consent D e c r e e . D i s c o v e r y con

ducted by the par t ies fo l l o w in g the commencement

o f th is lawsuit showed dramat ica l ly the degree to

which p a r t i c u l a r job c l a s s i f i c a t i o n s cou ld be

i d e n t i f i e d by race. I t a lso showed the extent

to which s e n i o r i t y r u l e s and t r a n s f e r r u l e s

impinged on the capacity o f defendants to e ra d i

cate the v e s t i g e s o f past r a c ia l d iscr im inat ion .

The p a r t i e s , o f course, had d i f f e r i n g views on the

extent to which such l in g e r in g e f f e c t s e x i s t . To

r e s o l v e t h e i r d isagreem ent and to s e t t l e the

controversy, the par t ies negot ia ted a proposed

consent decree s e t t l i n g a l l claims outstanding

between them and p re s en ted i t t o the d i s t r i c t

c o u r t , in accordance w i th Rule 2 3 ( e ) o f the

Federal Rules o f C i v i l Procedure.

One o f the p r in c ipa l features o f the proposed

7/ . . .

consent decree— was a s e n io r i t y clause requ ir ing

7/ Pa r t I I I o f the proposed consent d ec re e

stated the fo l low ing :

" I I I . INJUNCTIVE RELIEF FOR THE CLASS

In f u l l and f i n a l settlement o f any and

a l l claims fo r in junct ive r e l i e f a l l e g ed in the

Complaint, the par t ies agree to the fo l low ing :

1. For the purposes o f determining e l i g i b

i l i t y f o r vacations and f o r promotions,

14

curren t and fu tu re employees to be c r e d i t e d

with actual time worked at the plant as seasonal

employees. Another f e a t u r e o f the proposed

7/ (contd. )

l a y - o f f s and r e c a l l s , e v e ry curren t

and future regular hourly paid produc

t i o n employee o f the Richmond L ea f

Department w i l l be cred i ted with actual

t ime worked as a seasona l employee

commencing with the date o f h i r e o f the

las t period of continuing employment as

a seasonal employee in accordance with

Section 1 o f A r t i c l e 7 o f the current

c o l l e c t i v e bargaining agreement govern

ing seasonal employees. The combined

t o t a l o f such seasona l and r e g u la r

employment w i l l apply toward s e r v i c e

requ irem ents f o r v a c a t i o n s , and f o r

promot ions , demotions, l a y - o f f s and

r e c a l l s .

2. Regular employees who have served the

p r o b a t i o n a r y p e r i o d as a s e a s o n a l

employee during the last period of his

or her continuous seasonal employment

at Leaf p r io r to being transferred to

r e g u la r Lear employment w i l l become

e l i g i b l e f o r m e d i c a l b e n e f i t s and

s i ck b e n e f i t s immediate ly upon such

transfer to regular employment.

15

consent decree a l lowed seasona l employees to

t rans fer to permanent job posit ions as vacancies

occurred provided, o f course, no regular employees

7/ (contd. )

3. In the event that vacancies in hourly

paid permanent production job c l a s s i f i

cat ions at the Richmond Leaf Department

are not f i l l e d by r e g u la r p roduc t ion

employees, then a l l q u a l i f i e d hou r ly

paid seasona l p rodu c t ion employees

w i l l be g iven the opportunity to f i l l

such vacancies p r io r to h i r ing from the

outside.

4. In the even t tha t va canc ies in the

job c l a s s i f i c a t i o n , Watchman, at the

Richmond Leaf Department are not f i l l e d

by regular production employees, then

a l l q u a l i f i e d hou r ly paid seasona l

production w i l l be given the opportunity

to f i l l such vacancies p r io r to h ir ing

from the outside.

5. The Richmond Leaf Department adopts a

goal o f f i l l i n g the production super

v iso ry pos it ions of Foreman and Ass is

tan t Foreman w i th q u a l i f i e d b lacks

un t i l the percentage o f blacks in such

p o s i t i o n s equals 1/3 o f the t o t a l o f

such pos i t ions. The date o f December

31, 1980 is hereby established fo r the

accomplishment o f th is goal.

See Joint Appendix at 27a-28a.

- 16

desired the pos i t ions .

These p r o v i s i o n s were pa t te rn ed a f t e r the

r e l i e f fashioned for seasonal workers in Russell

v. American Tobacco Company, supra, 528 F.2d 357,

362-64 (4th Cir. 1975), c e r t . denied, 425 U.S. 935

(1976). Under the f i r s t above-mentioned feature

of the proposed consent decree, seasonal workers

are a l lowed to ma inta in t h e i r s e n i o r i t y upon

trans fe r to regular pos i t ions . Under the second

feature, seasonal employees are permitted to bid

on vacancies in c l a s s i f i c a t i o n s , such as watch

men, which were once reserved for whites.

In a d d i t i o n , the proposed consent decree

contained, in Part I I I , sect ion 5, an a f f i rm at iv e

action prov is ion to reduce a h i s t o r i c a l underrep

resentat ion of blacks which had ex is ted in the

supervisory pos i t ions. This prov is ion provided

th a t :

The Richmond Leaf Department adopts a

goal o f f i l l i n g the production super

v isory posit ions o f Foreman and Ass is

tant Foreman with q u a l i f i e d blacks u n t i l

the percentage o f blacks in such pos i

t ions equals 1/3 o f the to ta l o f such

p o s i t i o n s . The da te o f December 31,

1980 i s hereby e s t a b l i s h e d f o r the

accomplishment of th is goal.

Joint Appendix at 31a.

Furthermore, the consent decree el iminated

the requirement that seasonal workers must serve a

17

p ro b a t ion a ry p e r io d when they t r a n s f e r to a

fu l l - t im e pos i t ion . F ina l ly , the decree contained

a general in junction p roh ib i t ing the defendants

from d i s c r im in a t i n g a g a in s t b lack workers and

a report ing provis ion requiring the Company to

submit fo r a three-year period s p e c i f i c reports

d e t a i l i n g compliance w i th the Decree . J o in t

Appendix at 31a.

A l l o f the par t ies found that these p ro v i

sions represented, in l i g h t o f the h is to ry o f the

Richmond Leaf Department, a settlement that was

8 /reasonable, just , and f a i r to a l l concerned— .

Despite the i r agreement, the d i s t r i c t court, by

order f i l e d June 2, 1977, denied the jo in t motion

o f the par t ies to approve and enter the proposed

consent decree.

Several reasons were o f f e red by the d i s t r i c t

court in support o f i t s r e f u s a l to grant the

motion. F i r s t , the d i s t r i c t court judge stated

that T i t l e V I I o f the C i v i l Rights Act and the

due process clause o f the F i f th Amendment to the

8/ See the Memorandum in Support o f Entry o f

Proposed Consent Decree f i l e d by defendant Ameri

can Brands, Inc. in the d i s t r i c t court. Also, see

Memorandum in Support o f Entry o f Proposed Consent

Dec ree f i l e d in the d i s t r i c t cour t by the two

union defendants on A p r i l 15, 1977.

18

Const i tu t ion p roh ib i ted the defendant employer,

defendant, unions, and the d i s t r i c t court from

granting p r e f e r e n t i a l treatment to employees based

upon race except upon a showing o f past or present

d i s c r i m in a t i o n committed by the d e fen da n ts .

Second, the d i s t r i c t c ou r t s a id th a t the

proposed consent d ec re e was f a t a l l y f l aw ed in

seeking to provide f o r p r e f e r e n t i a l treatment fo r

black employees who were not shown to be v ic t ims

o f d iscr im inat ion . Moreover, because the in t r o

ductory sect ion o f the proposed consent decree

contained a p rov is ion in which defendants denied

that th e i r actions had been d iscr iminatory or un

lawful , and contained another p rov is ion in which

p l a i n t i f f s stated that they did not admit that

d e f e n d a n t s ' a c t i o n s were l a w fu l , the d i s t r i c t

court concluded that there was not " c r e a t e (d ) any

fac tua l basis upon which r e l i e f may be g ranted ."

446 F.Supp. at 788-789.

The d i s t r i c t court conceded, however, that

p r io r to September 1963, the " r egu la r job c l a s s i

f i c a t i o n s o f truck d r i v e r , watchman, maintenance,

storage , and b o i l e r operator . . . were reserved

f o r whites on ly " , 446 F.Supp. at 782, and that, as

o f A p r i l 5, 1976, only 20% o f the 35 superv isory

pos i t ions were f i l l e d with black employees. I d .

at 783.

19

P e t i t i o n e r s appea led the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s

order to the Fourth C ircu i t . That court dismissed

the appeal on the ground that the order was non-

appealable under 28 U.S.C. §§1291 and 1292 ( a ) ( 1 ) .

In holding that the d i s t r i c t cour t 's judgment

was not a p p ea lab le as an i n t e r l o c u t o r y decree

denying an injunction, the Court o f Appeals said,

"Here, in junct ive r e l i e f was not f i n a l l y denied;

i t was merely not granted at this stage o f the

proceedings." 600 F.2d at 423. I t regarded the

order as deciding only that the case should go to

t r i a l . I d . at 423.

Fol lowing the ra t iona le o f the Second C ircuit

in Se iga l v. Merr ick, 590 F.2d 35 (2d Cir. 1978),

i t held that disallowance o f the inter locutory

appeal would strengthen the power o f the d i s t r i c t

courts to draw part ies into presenting more favor

ab le s e t t l e m e n t p ro p osa ls . The d e n ia l o f one

agreement, i t said, did not necessar i ly prevent a

more "sweetened" agreement from being approved.

606 F.2d at 423-24. The court was obl iv ious to

whether the order dec ided the m er i ts o f the

action. I t stated that "whatever the d i s t r i c t

court 's reasons fo r re fus ing a decree, appeals o f

r i g h t s from those r e fu s a l s would encourage an

endless s tr ing o f appeals and destroy the d i s t r i c t

court 's superv is ion of the action as contemplated

by Fed.R.Civ .Proc. 2 3 (e ) " . Id. at 424.

20

The Fourth C ircu it recognized that i t s d ec i

sion was contrary to the decis ion in Norman v.

McKee, 431 F.2d 769 (9th Cir , 1970), c e r t . denied,

IS I v, Meyers, 401 U.S. 912 (1971), where the Ninth

C ircu it had held that orders disapproving proposed

settlements of s tockholder 's d e r iva t iv e suits are

9/

appealable as c o l l a t e r a l orders .— However, i t

merely noted the exis tence o f the case and did

9f Although the opinion in the Fourth Circuit

below im p l ied that p e t i t i o n e r s on ly sought an

inter locutory appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1 29 2 (a ) ( l ) ,

606 F.2d at 421, p e t i t i o n e rs , in f a c t , appealed

the decis ion under both §1291 and § 1 29 2 (a ) ( l ) . To

help c l a r i f y the matter, the facts concerning the

appeal are stated herein.

By l e t t e r to the Clerk o f the Fourth C ircuit

Court o f Appeals dated January 13, 1978, p e t i

t ioners stated that the d i s t r i c t court 's order

below was appealable under 28 U.S.C. §1291. Sub

sequently, however, p e t i t i on e rs f i l e d , on February

9, 1979 a supplemental memorandum in which they

stated, on page 2, that the case did not invo lve

the c o l l a t e r a l order doctr ine o f Cohen v. Bene f i

c i a l I n d u s t r i a l C orp . , 3 77 U.sT 541 (1949) .

On February 20, 1979, p e t i t i o n e r s f i l e d a

Supplemental Reply Memorandum in which they noted

the existence o f a c o n f l i c t between the c i r cu i t s

on the issue of appea lab i l i t y under §1291 o f a

d i s t r i c t court 's order disapproving a proposed

settlement of a de r i va t i v e action. Because the

proposed decree contained a request for an in

junction, pe t i t ion e rs stated that ju r i sd i c t i o n

could be upheld under §1292 (a ) ( l ) without reaching

21-

not s tate why the court 's analysis there was not

persuasive.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

A. Appea lab i l i ty Under §1291

P e t i t i o n e r s contend that the order o f the

d i s t r i c t court denying approval to the p a r t i e s '

j o i n t l y proposed consent decree was appealable as

a c o l l a t e r a l order. Separate and apart from the

issue o f whether defendants have pract iced ra c ia l

d iscr iminat ion against p l a i n t i f f s , th is Court has

established that a p r iva te employer and union can

vo lu n ta r i l y es tab l ish an a f f i rm a t iv e action plan

on behal f o f black employees in an industry in

which there is an imbalance o f black employees

with respect to white employees a r is ing out of a

9/ ( c on td . )

the issue under §1291. They cautioned, however,

that the court would be confronted with deciding

the appea lab i l i ty o f the order as a c o l l a t e r a l

order under §1291 i f the court could not sustain

ju r i s d i c t i o n under § 1 29 2 (a ) ( l ) . See p e t i t i o n e r s '

Reply to B r ie f in Opposition to C e r t io ra r i , n.4.

Although pe t i t ioners subsequently emphasized

the appea lab i l i ty o f the d i s t r i c t court 's order

under §1292 (a ) ( l ) in the i r Supplemental B r ie f fo r

the Appellants On Consideration En Banc, they did

not, at any time, waive or drop the ir ins istence

that the o rde r was ap pea lab le as a c o l l a t e r a l

order under §1291.

22

h i s t o r i c a l exclusion o f blacks. See United S t e e l -

workers o f America, AFL-CIO-CLC v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193 (1979). The denial o f the r igh t to s e t t l e

v o lun ta r i ly the instant action in accordance with

p r inc ip les set forth in Weber, supra, is there fore

a c o l l a t e r a l order a f f e c t in g r igh ts c o l l a t e r a l to

the merits o f the action and thus was appealable

under §1291.

B Appea lab i l i t y Under §1292 (a ) ( l )

P e t i t i on e rs contend that an examination o f

the grounds stated by the d i s t r i c t court in sup

port o f i t s order denying approval to entry o f a

consent decree granting a permanent injunct ion,

d iscloses that the order reso lved the merits of

the in junct ive claims and o f the T i t l e V I I claims.

Since these grounds prec luded the f i l i n g o f a

subsequent motion by p e t i t ion e rs f o r a prel iminary

in junction, the d i s t r i c t cour t 's order was appeal-

able under §1292 (a ) ( l ) as an in ter locutory order

refusing an injunct ion.

ARGUMENT

I

INTRODUCTION

This case concerns the a p p e a l a b i l i t y o f a

d i s t r i c t court 's order which, on the basis o f the

- 23

F i f t h C i r c u i t ' s opinion in Weber v. United S t e e l

workers o f America, AFL-CIO, 563 F .2d 216 (5th

Cir. 1977), subsequently reversed by th is Court in

Un ited S t e e lw o rk e rs o f America, AFL-CIO-CLC v .

Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979), refused to approve,

pursuant to Rule 23 o f the Fed. R. C iv . P. , a

j o in t motion by the part ies to enter a proposed

consent decree g ra n t in g permanent in ju n c t i o n

P e t i t i o n e r s contend that the order o f the

d i s t r i c t cour t i s a p p ea lab le , pursuant to the

c o l l a t e r a l order doctr ine, see Cohen v. B ene f ic ia l

Industr ia l Loan Corp. , 377 U.S. 541 (1949), as an

exception to the f i n a l i t y requirement o f 28 U.S.C.

§1291. P e t i t i on e rs also submit that the order is

appea lab le under 28 U.S.C. 1 1 2 9 2 (a ) (1 ) as an

in ter locu tory order denying in junct ive r e l i e f .

The a p p e a l a b i l i t y o f a d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s o rde r

which refuses to enter a j o i n t l y proposed consent

decree s e t t l in g the action and granting a perma

nent in junction, is a case o f f i r s t impression

in th is Court.

The in ter locu tory order o f the d i s t r i c t court

denied approval, under Rule 23 (e ) , o f the p a r t i e s '

j o i n t l y proposed consent decree and thereby

denied the i r j o in t request f o r a permanent injunc

tion. The appea lab i l i t y o f orders o f the d i s t r i c t

- 24 -

cour ts r e fu s in g to approve proposed consent

decrees has not been prev iously determined by the

Court. Furthermore, the Court has not, in general,

determined when i n t e r l o c u t o r y orders deny ing

permanent injunctions are appealable under §1292

( a ) ( 1 ) . Compare, e . g . , Smith v. Vulcan Iron Works,

165 U.S. 518 (1897) with Switzerland Cheese Asso-

t ion , Inc, v. E. Horne's Market, In c . , 385 U.S.

23, 23-25 (1966).

This case seemingly presents an opportunity

fo r the Court to reso lve both issues. P e t i t i on e rs

submit, however, that there are spec ia l fac tors

operative here, such as the Congressional p r e f e r

ence for voluntary settlement of T i t l e V I I actions,

see Alexander v, Gardner-Denver Co. , 415 U.S. 36,

44 (1974), and the pecul iar nature o f the grounds

assigned by the d i s t r i c t court in support o f i t s

order, which w i l l permit the Court to decide th is

case without determining, in general, the appeal-

a b i l i t y o f o rde rs deny ing proposed s e t t l em en t

decrees or the appea lab i l i ty o f orders denying

permanent i n ju n c t i v e r e l i e f . However, these

spec ia l circumstances do warrant allowance o f an

appeal from the order below under both §1291 and

§1292 (a ) ( 1 ) .

25

THE DISTRICT COURT ORDER REFUSING TO

APPROVE THE PARTIES' JOINTLY PRESENTED

CONSENT ORDER WAS A COLLATERAL ORDER

WHICH WAS APPEALABLE AS AN EXCEPTION

TO THE FINAL JUDGMENT REQUIREMENT OF

28 U.S.C. §1291.

A. General

Sect ion 1291 o f T i t l e 28 o f the United States

Code authorizes an appeal to a federa l court o f

appeals o f a f i n a l "dec is ion " or judgment, o f a

federa l d i s t r i c t court. This Court, however, has,

in in terp re t ing the statute to e f fe c tua te i t s pur

poses, made exceptions to the " f i n a l judgment"

rule . One such exception is the c o l l a t e r a l order

doctr ine under which the Court has allowed the

appeal o f an in ter locutory orders which is c o l l a t

e r a l to the m er i ts o f the u n d e r l y in g a c t i o n .

See Cohen v. B en e f ic ia l Industr ia l Loan Corp. , 337

U.S. 541 (1949).

This doctr ine, pe t i t ioners contend, is a p p l i

cable to an order o f the d i s t r i c t court which, in

a T i t l e V I I action, denied, under Rule 23 o f the

Fed. R. Civ. P. , approval o f a proposed consent

decree, on the ground that the decree provided

p re f e ren t ia l treatment on the basis of race to

black employees who were not victims of r a c i a l l y

discr iminatory actions by defendants.

26

At the outset, pe t i t ione rs s tress the impor

tance of the issue involved. Voluntary settlement

o f employment discr im ination suits l i e s at the

heart o f the e f f o r t to enforce T i t l e V I I . This

Court has emphasized th a t " (c ) o o p e r a t i o n and

voluntary compliance were se lected as the p r e f e r

red means for achiev ing" the goal of equal oppor

tunity in employment. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver

Co. , 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974). Judic ia l review in

the courts o f appeals of settlement decrees has

been extremely instrumental in carry ing out this

purpose of the statute . See, e . g . , . United States

v. City o f Miami, ___ F . 2d ___ (5th Cir. ) , 22 EPD

1130,821, Ap r i l 10, 1980; United States v. City o f

A l e x a n d r i a , _ F.2d ___ (5 th C i r . ) , 22 EPD

1130,828, Apr i l 10, 1980.

C onve rse ly , d i s a l l o w a n ce o f i n t e r l o c u t o r y

review o f orders disapproving proposed settlement

decrees is l i k e l y to f rust ra te the achievement o f

the purposes o f T i t l e V I I . Not only would i t put

a l l voluntary settlements of T i t l e V I I act ions at

the mercy o f d i s t r i c t judges but i t would also

force the part ies needless ly to undergo expensive,

time-consuming t r i a l s .

27

B. The Applicable Law

With the exception of 28 U.S.C. §1292, and

ce r ta in j u d i c i a l l y created except ions, the appeal-

a b i l i t y o f orders o f the d i s t r i c t court to the

federa l courts o f appeals is l im ited by 28 U.S.C.

§1291 to " f i n a l d ec is ions . " See Cobbledick v .

United S t a t e s , 309 U.S. 323 (1940 ) ; C a t l i n v .

United S ta tes , 370 U.S. 294 (1962). In i t s d e c i

sion in Cobbledick v. United S ta tes , supra, the

Court found that Congress, with the enactment o f

§1291, prohib ited "piecemeal d ispos i t ion on appeal

of what for p ra c t ica l purposes is a s ing le con

troversy . . . (and) set i t s e l f against enfeebling

ju d i c i a l admin is trat ion ." I d . 309 U.S. at 324.

Moreover, the Court has noted that the pur

pose of the f i n a l judgment rule is to avoid "the

obstruction to just claims that would come from

permitting the harassment and cost o f a succes

sion of separate appeals from the various rulings

to which a l i t i g a t i o n may g i v e r i s e , from i t s

i n i t i a t i o n to entry o f judgment." Cobbledick v .

United S ta tes , supra, 309 U.S. at 324. Thus, the

f in a l judgment ru le , which "has the support o f

c o n s id e r a t i o n s g e n e r a l l y a p p l i c a b l e to good

ju d ic ia l adminis trat ion" , Radio Station WOW, In c ,

v. Johnson, 326 U.S. 120 (1945), i s , in the f in a l

analys is , designed to enable courts and l i t i g a n t s

- 28 -

to avoid "the mischief of economic waste and o f

delayed j u s t i c e . " I d . 326 U.S. at 123. Also see

Dickinson v. Petroleum Conversion Corp. , 338 U.S.

507, 511.

D esp i t e the laudab le goa ls o f §1291, the

courts have discovered that there are occasions

where a s t r i c t app l ica t ion o f the f i n a l judgment

r u l e w i l l not e f f e c t u a t e the purposes o f the

statute and instead "would p ra c t i c a l l y defeat the

r igh t o f any review at a l l . " Cobbledick v . United

S ta tes , 309 U.S. at 324. In these cases, denial

o f the r i g h t t o an immediate a p p e l l a t e r ev iew

would cause irreparable- injury to the party seek

ing review. This i s the basic j u s t i f i c a t i o n for

the C o u r t ' s adopt ion o f the c o l l a t e r a l order

doctr ine under which cer ta in in ter locutory orders

can be immediately appealed despite the absence of

a f in a l judgment terminating the action.

The c o l l a t e r a l order doctr ine was ar t icu la ted

and applied in Cohen v. B en e f ic ia l Industr ia l Loan

Corp. , 337 U.S. 541 (1949). There, the Court, in

uphold ing an i n t e r l o c u t o r y appea l o f an order

denying a request by defendant for the posting o f

a bond by p l a i n t i f f , observed that the

order o f the D i s t r i c t Court did not make

any step toward f i n a l d ispos i t ion o f the

merits o f the case and w i l l not be mer

ged in f in a l judgment. When that time

comes, i t w i l l be too la te e f f e c t i v e l y

29

t o r e v i e w the p re s en t o r d e r , and the

r i gh ts conferred by the statu te i f i t

i s a p p l i c a b l e , w i l l have been l o s t ,

probably i r r epe rab ly We conclude that

the m at te r s embraced in the d e c i s i o n

appealed from are not o f such an i n t e r

locutory nature as to a f f e c t , or to be

a f f e c t ed by, dec is ion o f the mer its of

th is case.

Id . a t 546. A c c o r d i n g l y , i t h e ld the o rde r

appealable on the grounds that i t :

appears to f a l l in th a t smal l c l a s s

w h ich f i n a l l y d e t e r m i n e c l a i m s o f

r i g h t separable from, and c o l l a t e r a l to ,

r i g h t s a s s e r t e d in the a c t i o n , t o o

important to be denied rev iew and too

independent o f the cause i t s e l f to

r e q u i r e tha t a p p e l l a t e c o n s i d e r a t i o n

be d e f e r r e d u n t i l the whole case is

adjudicated.

I d . at 546.

The Cohen ru le requ ires that an order must

have three basic ch a ra c te r i s t i c s be fore i t can

qu a l i fy as a c o l l a t e r a l order. F i r s t , the order

must adverse ly a f f e c t a r i gh t that is separate

and independent from whatever r igh ts are asserted

in the act ion . Second, the order must cons t i tu te

a f i n a l determinat ion o f those r i gh ts . Third, the

order must be one whose review cannot be postponed

u n t i l f i n a l judgment because delayed rev iew w i l l

cause i r r e p a r a b l e harm by caus ing the r i g h t s

conferred to be i r r e t r i e v a b l y l o s t .

In a p p ly in g th ese c r i t e r i a to de term ine

a p p ea la b i l i t y , a court must adopt a "p r a c t i c a l

rather than a techn ica l construct ion" o f §1291.

- 30 -

Cohen v. B en e f ic ia l Industr ia l Loan Corp. , supra,

337 U.S. at 546. Such an approach w i l l neces

s i t a t e an evaluat ion o f the competing considera

tions o f "the inconvenience and costs o f piecemeal

review on the one hand and the danger o f denying

j u s t i c e by de lay on the o th e r . "12.̂ E isen v .

C a r l i s l e & Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 156, 171 (1974),

c i t i n g D ick inson v. Petroleum Conversion Corp.,

338 U.S. 507, 511 (1950).

C. App l icat ion o f the Cohen C r i t e r ia

This Court has defined a c o l l a t e r a l issue as

an issue which i s "a s epa ra te and independent

matter, anter ior to the merits and not enmeshed in

the factual and l ega l issues comprising p la in

t i f f ' s cause o f ac t ion . " Mercanti le Nat ional Bank

at Dallas v. Langdeau, 371 U.S. 555, 558 (1963).

The r i g h t to reach a l a w fu l s e t t l e m e n t o f a

T i t l e V I I employment d iscr im inat ion case pursuant

to the g u id e l in e s se t f o r t h by t h i s Court in

Weber, supra , i s s epa ra te and a n t e r i o r to the

m er i ts o f the c la ims in the T i t l e V I I a c t i o n .

10/ In Norman v. McKee, 431 F.2d 769 (9th Cir.

1970) c e r t , d e n i e d , 401 U.S. 912, the Ninth

C ircu it allowed an appeal from a d i s t r i c t court 's

r e j e c t io n o f a settlement agreement. The court

said that the settlement o f a class action under

Fed.R.Civ. P. 23 is appealable as a f in a l decis ion

- 31

The issues in a T i t l e V I I a c t i o n concern

issues such as the fo l low ing : (1 ) the existence

o f d iscr im inatory employment pract ices by defen

dant; (2 ) v i c t im iza t i o n o f p l a i n t i f f by defen

d a n t ' s d i s c r im in a t o r y p r a c t i c e s ; and (3 ) the

f a s h io n in g o f remedies that are commensurate

in scope with the defendant's v i o l a t i o n o f law.

See, e . g . , Teamsters v. United S ta tes , 431 U.S.

324 (1977).

By c o n t r a s t , as t h i s Court i n d i c a t e d in

U n i t e d S t e e l w o r k e r s o f America, AFL-CIO-CLC

v. Weber, supra, where i t upheld the lawfulness

o f a ra c e - c o n sc iou s a f f i r m a t i v e a c t i o n plan

r e s e r v in g 50% o f the openings in an in -p la n t

c ra f t tra in ing program for black employees, the

re levant issues in determining the lawfulness o f a

p r iva te , v o lu n ta r i ly negotiated a f f i rm a t iv e act ion

plan are (1 ) the extent to which the plan operates

to reduce or l e s s en , p r e - e x i s t i n g p a t te rn s o f

r ac ia l segregation and hierarchy by opening em

ployment opportunities to blacks in occupational

areas which have been t r a d i t i o n a l l y c lo s ed to

10/ (contd . )

under 28 U.S.C. §1291, because the " inconvenience

of piecemeal rev iew o f an order disapproving a

settlement is outweighed by the danger o f denying

ju s t ic e by d e la y . " 431 F.2d at 774.

- 32 -

areas which have been t r a d i t i o n a l l y c l o s ed to

them; (2 ) the degree to which the plan unneces

s a r i l y trammels the in teres ts o f white and other

workers or creates a bar to the advancement o f

t h e i r l e g i t i m a t e i n t e r e s t s ; (3 ) the temporary

nature o f the plan; (4 ) the extent to which the

plan is intended to e l iminate a manifest r a c ia l

imbalance and not to maintain r a c ia l balance; and

(5 ) the extent to which the s ignator ies to the

a f f i r m a t i v e a c t i o n agreement adopted the p lan

vo lu n ta r i l y . See United Steelworkers o f America,

AFL-CIO-CLC v . Weber , supra , 443 U.S. at 208.

M oreover , the Court in Weber, supra , e x

p l i c i t l y noted that the lawfulness o f a p r iva te ,

voluntary a f f i rm a t iv e action plan is separate and

apart from the issue o f a v i o l a t i o n o f T i t l e V I I .

I t said

" ( S ) i n c e the Kaiser-USWA p lan was

adopted v o lu n ta r i l y , we are not con

cerned with what T i t l e V I I requires or

with what a court might order to remedy

a past proved v i o l a t i o n of the A c t . "

I d . 443 U.S. at 200. Thus, the issue o f whether

p l a i n t i f f s and defendants can vo lun ta r i ly agree

upon a bona f i d e a f f i r m a t i v e a c t i o n p lan that

grants r a c i a l p r e f e r e n c e s is a n t e r i o r to and

not enmeshed in the issues o f a T i t l e V I I su i t .

Weber, supra, 443 U.S. at 200.

33

The C o u r t ' s d e c i s i o n in Weber, supra, not

only established that the issue o f the v a l i d i t y

of p r iva te a f f i rm a t iv e action plans f o r blacks is

separate and independent of lega l issues ar is ing

in a T i t l e V I I a c t i o n , but a l s o a f f i rm e d that

p r iva te employers, and unions have a r ight under

T i t l e V I I to enter vo lun tar i ly into such plans.

Moreover, the Court, in Weber, supra, protected

the exerc ise o f th is r igh t against opposing claims

o f th ird par t ies , such as employees who pre fer to

see the plans abandoned. 443 U.S. at 200-209.

Of course, the r igh t to in s t i tu t e an a f f i rm a

t i v e action plan, such as the one in Weber, only

ex is ts when the plan complies with the c r i t e r i a

set for th in Weber, supra, 443 U.S. at 208. As

the Court noted in Weber, the adoption o f race

conscious, a f f i rm a t iv e action plans

f a l l s w i th in the area o f d i s c r e t i o n

l e f t by T i t l e V I I to the pr ivate sector

vo lu n ta r i l y to adopt a f f i rm at ive act ion

plans designed to el iminate conspicuous

ra c ia l imbalance in t r a d i t i o n a l l y se

gregated job categor ies .

443 U.S. 209.

I t is undisputed, in the present act ion, that

" r e g u l a r job c l a s s i f i c a t i o n s o f truck d r i v e r ,

watchman, maintenance, storage, and b o i l e r oper

ator . . . were reserved fo r whites only" pr ior to

- 34 -

September 1963. 446 F.Supp. at 782. S im i la r ly , i t

i s undisputed th a t , p r i o r to September 1963,

there ex is ted separate unions f o r black and white

workers . F i n a l l y , i t i s undisputed tha t the

j u r i s d i c t i o n o f the union r ep r e se n t ing b lack

employees was, p r io r to September 1963, r e s t r i c t ed

to seasonal employees and that the ju r i s d i c t i o n

o f the union representing white employees was, at

that time, r e s t r i c t e d to nonseasonal, regular job

c l a s s i f i c a t i o n s .

Since the terms o f the proposed consent

decree were in a l l other respects in compliance

with the c r i t e r i a set fo r th in Weber, supra, p e t i

t ioners had a r i gh t to s e t t l e the action as pro

vided by the decis ion in Weber, supra. E i ther

Rule 41(c ) or Rule 68 o f Fed.R.Civ .P, could have

been u t i l i z e d by the part ies to f a c i l i t a t e s e t t

l in g th e i r grievances without in tervent ion o f the

„ 11/courts. —

11/ Fed. R. C iv . P . , 4 1 (a ) p ro v id e s th a t an

action may be vo lu n ta r i ly dismissed by the p la in

t i f f with the consent of a l l par t ies . S im i lar ly ,

Rule 68 provides that

"At any time more than 10 days b e f o r e the

t r i a l b eg in s , a p a r t y d e fen d in g a g a in s t a

c la im may s e rve upon the adverse p a r ty an

o f f e r to al low judgment to be taken against

him . . . to the e f f e c t sp ec i f i ed in his o f f e r .

I f w ith in 10 days a f t e r the serv ice of the

- 35

This Court has s ta t ed that courts should

accord deference to the processes of voluntary

c o n c i l i a t i o n and settlement. See, e . g . , Alexander

v. Gardner-Denver Co. , 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974).

S i m i l a r l y , the lower courts have sanct ioned

settlement e f fo rt 's in c i v i l r ights act ions. As

the F i f t h C ircu i t said in United States v. A l l e g -

heny-Ludlum Industr ies , In c . , 517 F . 2d S26, 846

(5 th C i r . 1975) , c i t i n g Dent v . St. Lou is-San

Francisco Ry. Co. , 406 F.2d 399, 402 (5th Cir.

1969),

I t is quite apparent that the basic

philosopy o f these statutory provisions

is that voluntary compliance is p re fe r

able to court action and that e f f o r t s

should-be made to reso lve these employ

ment r igh ts by conc i la t ion both before

and a f t e r court action.

The exis tence of a r igh t to s e t t l e a T i t l e

V I I act ion in accordance with the standards set

for th in Weber, supra, d istinguishes th is case from

Coopers & Lybrand v. L iv esay , 437 U.S. 463, 467

(1978) and Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting

11/ (contd. )

o f f e r the adverse party serves wr i t ten notice

that the o f f e r is accepted, e i ther party may

then f i l e the o f f e r and notice of acceptance

together with proof o f serv ice thereof and

thereupon the c lerk shall enter judgment."

- 36 -

Co., 437 U.S. 478 (1978). In Coopers & Lybrand

and Gardner, th is Court held that an order re fus

ing c e r t i f i c a t i o n o f a class was not appealable as

a c o l l a t e r a l order or as an in ter locutory order

denying an injunction.

The p l a i n t i f f s there had no substantive r igh t

to have the action c e r t i f i e d as a class act ion

under Rule 23. Nor did denial o f th e i r claim for

class c e r t i f i c a t i o n a f f e c t any substantive r ights

o f th e i rs . By contrast , p e t i t i on e rs here have a

substantive r igh t which is based upon the Court 's

decis ion in Weber, supra, and which i s supported

by Congressional p o l ic y promoting settlements of

T i t l e VI I actions.

Although F ed e ra l Rule o f C i v i l P rocedure

23 (e ) , to be sure, prevents par t ies from having an

unencumbered r igh t to s e t t l e class actions, Rule

23(e) does not negate the p a r t i e s ' l e ga l r i gh t to

s e t t l e the case in accordance with standards set

forth in Weber, supra.

The p o l i c y behind Rule 2 3 (e ) stems from a

need to p r o t e c t the i n t e r e s t s o f those c la s s

members who are absent during settlement negot ia

t i o n s . The need to p r o t e c t the absent c la s s

members, however is minimal in a case, such as

here, where the only r i gh t o f p ro tec t ion advanced

in the ir behalf is one which th is court re jec ted

- 37

in United Steelworkers v. Weber, supra. A d i s

t r i c t court cannot, under the guise o f e f f e c tu a t

ing Rule 23 (e ) , c o l l a t e r a l l y attack the holding

and ra t iona le of the Court 's dec is ion in Weber.

Inso far as the r ights o f th ird part ies seek

ing p ro tec t ion under Rule 23(a) do not d i f f e r from

those asserted by p l a i n t i f f Weber in United S t e e l

workers o f America v. Weber, supra, Rule 23(a ) , as

a m atte r o f law, cannot be used to d e f e a t the

r igh ts of p r iva te part ies to in s t i tu t e an a f f i rm a

t i v e action plan which conforms to the requ ire

ments o f the Court se t f o r t h in Un ited S t e e l

workers o f America v. Weber, supra. Such a rule

of law is a necessary requirement i f the proposed

consent order is one which, l i k e here, does not r e

quire the discharge o f white workers, does not

unnecessari ly trammel upon the in teres t o f white

employees, is vo lun ta r i ly adopted, is designed to

el iminate t ra d i t i o n a l patterns of r a c ia l segrega

t ion and hierarchy, is temporary, is created to

el iminate a manifest r a c ia l balance and not to

maintain a r a c ia l balance, and does not require a

percentage o f black employees greater than that o f

blacks in the re levant labor force.

P e t i t i o n e r s ' r igh ts under Weber, supra, were

thus denied as a resu l t of the d i s t r i c t court 's

r e j e c t i o n o f the proposed decree on the basis of

38

the inclusion of an a f f i rm a t iv e action plan with in

the decree. By r e j e c t in g the decree, the d i s t r i c t

Court therefore made a f in a l determination o f the

p a r t i e s ' c o l l a t e r a l r igh t to s e t t l e the act ion in

accordance with the decis ion in Weber.

This aspect o f the case d i s t in g u i s h e s i t

from Seiga l v. Merr ick, 590 F.2d 35 (2d Cir. 1978),

which was r e l i e d upon by the Court o f Appeals

below. In S e ig a l , the Second C ircu i t held that

a d i s t r i c t cour t 's disapproval of a settlement

agreement in a stockholder 's d e r i va t i v e act ion

was not appealable as a c o l l a t e r a l order.

Objections were raised in Siegal v, Merr ick ,

supra , to the proposed s e t t l em en t because o f

disagreements concerning the date on which the

value of an option was measured and concerning the

c r i t e r i a by which the value of the option should

be measured. These objec t ions , however, were not,

as here, contrary to l e ga l pr inc ip les enunciated

by t h i s Court. Rather , they were based upon

concepts o f f a i r n e s s and e q u i t y which had not

p r e v i o u s l y been d e f i n i t i v e l y r e s o l v e d by th i s

Court. To th is extent, there fore , the facts of

Siegal v. Merr ick, supra, are d is t inguishable from

the facts of the present case.

The duty o f the d i s t r i c t court in S iega l v,

Merrick, supra, was to determine, pursuant to Rule

- 39

23 whether the proposed settlement o f the stock

ho lder 's d e r i v a t i v e act ion was, in l i g h t o f the

object ions made to i t , f a i r and equitable . A l

though the d i s t r i c t court below also had a duty

to determine i f the terms o f the proposed consent

decree were f a i r and e q u i t a b l e , i t a l s o had

imposed upon i t a duty to insure that i t s de ter

m inat ion o f what is f a i r and e q u i t a b l e was in

accordance with the purposes o f T i t l e V I I and with

appl icab le l e ga l pr inc ip les determined by this

Court. This Court 's dec is ion in Weber, supra,

demonstrates that the d i s t r i c t court below f a i l e d

to s a t i s f y th is ob l iga t ion .

These c o n s id e r a t i o n s show that the Second

C i r c u i t ' s dec is ion in S iega l v. Merr ick, supra, is

inapplicable to the facts o f th is case. The op

posing decis ion of the Ninth C ircu it in Norman v .

McKee, supra, in which the court held that orders

refusing proposed settlements are appealable as

c o l l a t e r a l orders, states the be t te r ru le , espe

c i a l l y in cases such as here where the basis for

the order refusing the consent decree is based

upon a v i o l a t i o n o f important, substantive in

terests which the Congress has sought to protect

and maintain.

The second prong of the Cohen tes t requires

that an order const i tutes a f in a l determination o f

- 40

the c o l l a t e r a l r igh ts involved before an appeal

under §1291 is al lowed. The Court, however, has

recognized that the determination o f when a r igh t

has been f i n a l l y decided and is thereby r ip e fo r

appeal under the c o l l a t e r a l order doctr ine , i s not

an exact science; In Dick inson v. Petroleum Con-

vers ion Corp. , supra, 338 U.S. at 511, Mr. Justice

Jackson emphasized that there was no set formula

for determining the f i n a l i t y o f a decree. The only

r e l i a b l e guide which the Court has found is the

avoidance o f any r i g i d ins is tence on te chn ica l i ty

which c o n f l i c t s with the purposes o f §1291 and the

c o l l a t e r a l order doctr ine. This approach requires

a " p r a c t i c a l " inquiry to determine i f the nature

and the e f f e c t o f the d i s t r i c t cour t 's denia l o f

the the settlement decree i s such that review o f

the order cannot be postponed u n t i l the rendit ion

o f a f in a l judgment in the action See Eisen v .

C a r l i s l e & Jacquelin , 417 U.S. 156, 170 (1974);

G i l l e sp ie v. U.S. S tee l Corp. , 379 U.S. 148, 152

(1964).

One fac tor which bears on the f i n a l i t y o f a

c o l l a t e r a l order is whether the issue requir ing

review w i l l become moot i f the review i s delayed.

Thus, for instance, the d i s t r i c t court 's order in

Gardner v. Westinghouse C o . , 437 U.S. 478, (1978)

- 41

denying class c e r t i f i c a t i o n , was held not appeal-

able p rec is e ly because e f f e c t i v e r e l i e f could be

provided even a f t e r f i n a l judgment on the merits

o f the act ion, i f the p r io r denial o f r e l i e f was

shown to be in error . Id. 437 U.S. at 480. On

the other hand, in Eisen v. C a r l i s l e & Jacquel in ,

supra, the Court permitted an appeal o f a d i s t r i c t

court 's order which imposed 90% o f the cost o f

g iv ing no t ice to class members in a secur i t ies

fraud case upon the defendant. Disallowance of

the appeal would have made moot the c o l l a t e r a l

claim since i t was the order which permitted the

p l a i n t i f f s ' su it to proceed as a class action.

Id. 417 U.S. at 172.

In the p resen t case , the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s

order d ep r iv ed the p a r t i e s o f t h e i r r i g h t to

remedy the e f f e c t s o f p r io r segregated job prac

t ices by invoking th e i r r igh ts under Weber, supra,

and T i t l e V I I to s e t t l e the action vo lun tar i ly .

The teno r o f the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s op in ion

below tended to ind icate that a f in a l determina

t ion had been made. The opinion stated that the

Court would enter a consent decree only when "the

part ies have s e t t l e d the i r d i f fe rences without a

v i o l a t io n o f the law and without v i o l a t in g the

- 42

r igh t o f any c lass member. 446 F. Supp. at 791.

At another port ion o f the opinion, the d i s t r i c t

court claimed that " P r e f e r e n t i a l treatment on the

basis o f race - any race - v i o la t e s the Constitu

t i o n , " 446 F. Supp. at 788. I t also said that

"the Court perce ives no such v e s t i g e s " o f d i s

cr im inat ion ." 446 F. Supp. at 790.

These f indings and conclusions would, i f l e f t

s tand ing , u t t e r l y doom any p o s s i b i l i t y o f a

settlement. The p a r t i e s ' w i l l ingness to s e t t l e

th e i r d i f fe rences is dependent, at any time, upon

the prospects fo r ul t imate v i c to r y then as w e l l as

the probable costs in money, resources, and time,

o f seeking such a v i c to r y .

The d i s t r i c t judge , by s t a t i n g tha t he

perceived no evidence o f d iscr im inat ion by the

defendants, created an incent ive f o r defendants to

go to t r i a l to win the case. Once t r i a l , however,

had begun, th e re would be no way in which the

p a r t i e s , d e s p i t e whatever might be done upon

review o f a f i n a l judgment, could r e t r i e v e the

advantages which a settlement would have brought.

- 43

Moreover, the advantages o f a par t icu lar s e t t l e

ment which was p robab le at one time would be

fo rever l o s t . See Norman v. McKee, supra. Thus,

the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s o rd e r f i n a l l y determined

p e t i t i o n e r s ' c o l l a t e r a l r igh ts .

The th ird prong of the Cohen test requires

that the in ter locutory order must have an " i r

reparable" e f f e c t . This r e f e rs to the nature and

the extent o f the in jury , such as whether i t is

destruct ive , substant ia l, continuing or irremedi-

a l . See, e . g . , Osborne v. Missouri P.R. Co . , 147

U.S. 248, 258 (1893); Brown v. Chote, 411 U.S.

452, 456 (1973). Also, however, as the Court has

noted, "inadequacy o f ava i lab le remedies goes . .

. to the exis tence o f ir reparab le in ju ry . " United

States v. American Friends Service Committee, 419

U.S. 7, 11 (1974). For the reasons previously

mentioned, however , w i th r esp e c t to why the

d i s t r i c t cour t 's order in th is case was a f in a l

determination o f p e t i t i o n e r s ' c o l l a t e r a l r igh ts ,

the order caused p e t i t i o n e r s ' ir reparab le in jury .

I t was there fore appealable, pursuant to §1291, as

a c o l l a t e r a l order.

- 44

I I I

THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER BELOW IS

APPEALABLE UNDER 28 U.S.C. §1292 (a ) ( l )

AS AN INTERLOCUTORY ORDER DENYING AN

INJUNCTION

The second issue ra ised in th is case concerns

the appea lab i l i t y , under 28 U.S.C. § 1292 ( a ) ( I ) , o f

a d i s t r i c t court 's order which denied, as a matter